Fernando Wood on:

[Wikipedia]

[Google]

[Amazon]

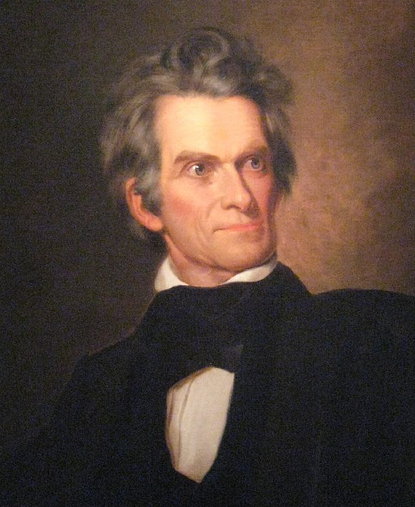

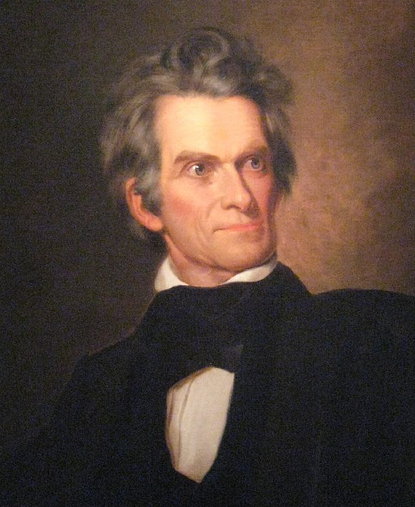

Fernando Wood (February 14, 1812 – February 13, 1881) was an American Democratic Party politician, merchant, and real estate investor who served as the 73rd and 75th

In need of funds and expecting his first child, Wood left politics after 1842 to reopen his ship chandler firm on the

In need of funds and expecting his first child, Wood left politics after 1842 to reopen his ship chandler firm on the

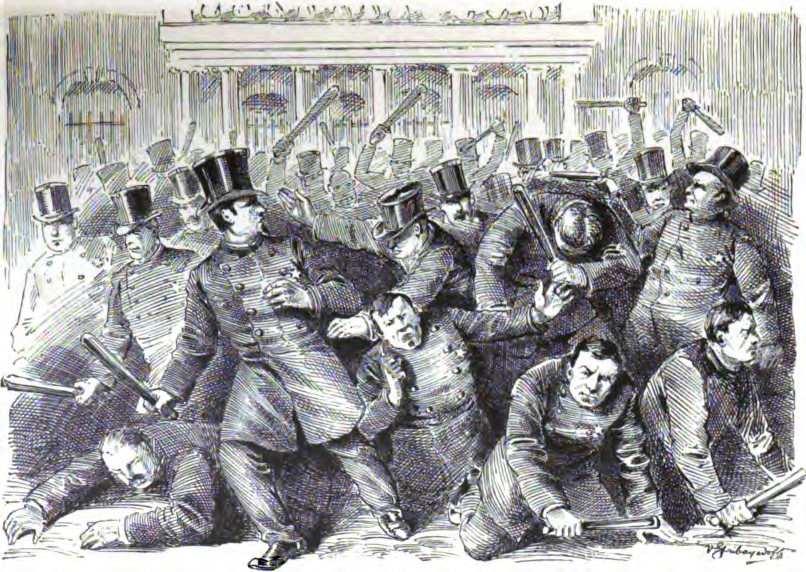

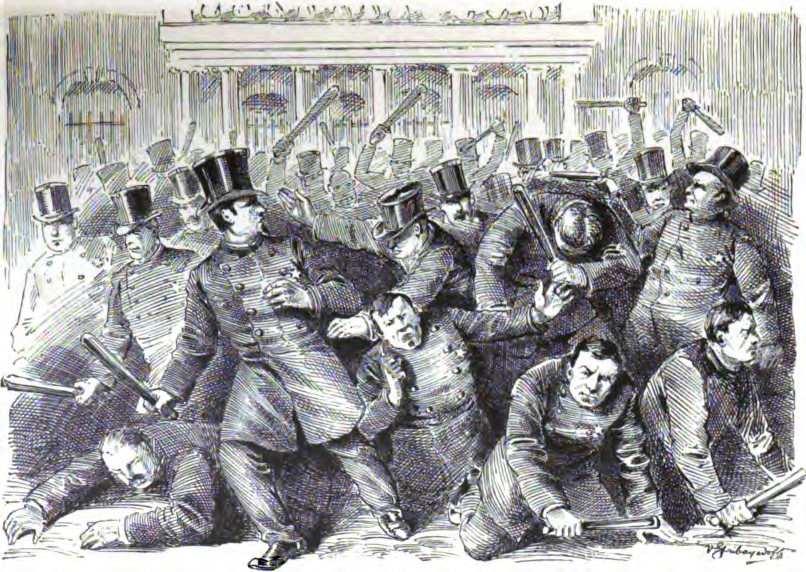

In Wood's second term, his control over Tammany Hall unraveled and his handling of the police force boiled over in the New York City Police riot and Dead Rabbits riot.

In April, the Republican legislature passed a new City Charter which truncated Wood's current term to one year, a Police Reform Act dissolving Wood's Municipal police in favor of a Metropolitan state unit, and an Excise Act implementing restrictive liquor licensing throughout the state. Wood committed himself to resisting the Police Reform Act and maintaining his own Municipal police, culminating in a police riot and Wood's orchestrated arrest on June 16.

In Wood's second term, his control over Tammany Hall unraveled and his handling of the police force boiled over in the New York City Police riot and Dead Rabbits riot.

In April, the Republican legislature passed a new City Charter which truncated Wood's current term to one year, a Police Reform Act dissolving Wood's Municipal police in favor of a Metropolitan state unit, and an Excise Act implementing restrictive liquor licensing throughout the state. Wood committed himself to resisting the Police Reform Act and maintaining his own Municipal police, culminating in a police riot and Wood's orchestrated arrest on June 16.

pp. 193-196

* Oakes, James. ''Freedom National: The Destruction of Slavery in the United States (1861–1865)''. W.W. Norton & Company, 2013.

Mr. Lincoln and New York: Fernando Wood

* ttp://www.spartacus-educational.com/USACWwood.htm Fernando Woodbr>Gregory Christiano surveys Fernando Wood, the rival police forces, gang wars and the Panic of 1857: 'Introduction to a turbulent period in New York City history."Fernando Wood's recommendation to the city council, January 6, 1861.Fernando Wood's Biographical Entry

at the Biographical Directory of The United States Congress , - , - , - , - , - , - , - , - , - {{DEFAULTSORT:Wood, Fernando 1812 births 1881 deaths 19th-century American politicians American people of Welsh descent American proslavery activists American white supremacists Censured or reprimanded members of the United States House of Representatives Copperheads (politics) Democratic Party members of the United States House of Representatives from New York (state) Leaders of Tammany Hall Mayors of New York City People of New York (state) in the American Civil War Politicians from Philadelphia

Mayor

In many countries, a mayor is the highest-ranking official in a municipal government such as that of a city or a town. Worldwide, there is a wide variance in local laws and customs regarding the powers and responsibilities of a mayor as well ...

of New York City

New York, often called New York City or NYC, is the List of United States cities by population, most populous city in the United States. With a 2020 population of 8,804,190 distributed over , New York City is also the L ...

. He also represented the city for several terms in the United States House of Representatives

The United States House of Representatives, often referred to as the House of Representatives, the U.S. House, or simply the House, is the lower chamber of the United States Congress, with the Senate being the upper chamber. Together they ...

.

After rapidly rising through Tammany Hall

Tammany Hall, also known as the Society of St. Tammany, the Sons of St. Tammany, or the Columbian Order, was a New York City political organization founded in 1786 and incorporated on May 12, 1789 as the Tammany Society. It became the main loc ...

, Wood served a single term in the U.S. House before returning to private life and building a fortune in real estate speculation and maritime shipping.

He was elected mayor for the first time in 1854 and served three non-consecutive terms. His mayoralty was marked by an almost dictatorial vision of the office and political corruption in the city's appointed offices, including the New York City police force. His political appointments and his advocacy for unilateral reform of the city charter to strengthen his power and grant the city home rule brought him into direct conflict with the Republican state legislature, leading to a charter revision that prematurely ended his second term in office and resulted in his arrest. He returned to the mayor's office for a final term in 1860.

After leaving the mayor's office, Wood was elected to several more terms in the House of Representatives, where he served for sixteen years. In his final two terms in that office, he served as Chairman of the powerful House Committee on Ways and Means.

Throughout his career, Wood expressed political sympathies for the American South, including during the American Civil War

The American Civil War (April 12, 1861 – May 26, 1865; also known by Names of the American Civil War, other names) was a civil war in the United States. It was fought between the Union (American Civil War), Union ("the North") and t ...

. He once suggested to the New York City Council

The New York City Council is the lawmaking body of New York City. It has 51 members from 51 council districts throughout the five boroughs.

The council serves as a check against the mayor in a mayor-council government model, the performance of ...

that the city should declare itself an independent city-state

A city-state is an independent sovereign city which serves as the center of political, economic, and cultural life over its contiguous territory. They have existed in many parts of the world since the dawn of history, including cities such as ...

in order to continue its profitable cotton trade with the Confederate States. In the House, he was a vocal opponent of President Abraham Lincoln

Abraham Lincoln ( ; February 12, 1809 – April 15, 1865) was an American lawyer, politician, and statesman who served as the 16th president of the United States from 1861 until his assassination in 1865. Lincoln led the nation throu ...

and one of the main opponents of the Thirteenth Amendment, abolishing slavery.

Early life

Fernando Wood was born inPhiladelphia

Philadelphia, often called Philly, is the largest city in the Commonwealth of Pennsylvania, the sixth-largest city in the U.S., the second-largest city in both the Northeast megalopolis and Mid-Atlantic regions after New York City. Since ...

on February 14, 1812. His Spanish forename was chosen by his mother, who found it in ''The Three Spaniards'', an English gothic novel

Gothic fiction, sometimes called Gothic horror in the 20th century, is a loose literary aesthetic of fear and haunting. The name is a reference to Gothic architecture of the European Middle Ages, which was characteristic of the settings of ea ...

written by George Walker George Walker may refer to:

Arts and letters

* George Walker (chess player) (1803–1879), English chess player and writer

*George Walker (composer) (1922–2018), American composer

* George Walker (illustrator) (1781–1856), author of ''The Co ...

.

His father, Benjamin Wood, was a speculator in dry goods who was bankrupted by the Panic of 1819

The Panic of 1819 was the first widespread and durable financial crisis in the United States that slowed westward expansion in the Cotton Belt and was followed by a general collapse of the American economy that persisted through 1821. The Panic ...

. His mother, Rebecca (née Lehman) Wood, was the daughter of a recent immigrant from Hamburg

Hamburg (, ; nds, label=Hamburg German, Low Saxon, Hamborg ), officially the Free and Hanseatic City of Hamburg (german: Freie und Hansestadt Hamburg; nds, label=Low Saxon, Friee un Hansestadt Hamborg),. is the List of cities in Germany by popul ...

who had been wounded at the Battle of Yorktown

The Siege of Yorktown, also known as the Battle of Yorktown, the surrender at Yorktown, or the German battle (from the presence of Germans in all three armies), beginning on September 28, 1781, and ending on October 19, 1781, at Yorktown, Virgi ...

.

Fernando had six siblings: four brothers and two sisters. His brother, named Benjamin Wood after their father, also served in the U.S. Congress. Throughout Fernando Wood's career, Benjamin was his sole trusted ally.

During Fernando's childhood, his father moved the family frequently: from Philadelphia to Shelbyville, Kentucky

Shelbyville is a home rule-class city in and the county seat of Shelby County, Kentucky, United States. The population was 14,045 at the 2010 census.

History

Early history

The town of Shelbyville was established in October 1792 at the first m ...

; ; Havana, Cuba

Havana (; Spanish: ''La Habana'' ) is the capital and largest city of Cuba. The heart of the La Habana Province, Havana is the country's main port and commercial center.

; Charleston, South Carolina

Charleston is the largest city in the U.S. state of South Carolina, the county seat of Charleston County, and the principal city in the Charleston–North Charleston metropolitan area. The city lies just south of the geographical midpoint o ...

; and finally New York City

New York, often called New York City or NYC, is the List of United States cities by population, most populous city in the United States. With a 2020 population of 8,804,190 distributed over , New York City is also the L ...

, where he opened a tobacconist store in 1821. The business failed by 1829 and Benjamin Wood left his family to die, impoverished and alone in Charleston.

Early business

In New York, Fernando enrolled in a private academy run by James Shea of Columbia College. He was educated in grammar, rhetoric, and mathematics. He left school in 1825 at age 13, as his father's business declined, in order to provide for his family. For six years, he worked throughout the Eastern United States in a variety of low-paying jobs, including as a stage actor. In 1831, he married his first wife, Anna W. Taylor, the 16-year old daughter of a Philadelphia merchant. In 1832, Wood returned to New York City to head his mother's household at 140 Greene Street. He struggled in business, often working nights at his wife's wine and tobacconist store on Pearl Street. In 1835, Wood started a ship chandler firm with Francis Secor and Joseph Scoville, but the business failed during thePanic of 1837

The Panic of 1837 was a financial crisis in the United States that touched off a major depression, which lasted until the mid-1840s. Profits, prices, and wages went down, westward expansion was stalled, unemployment went up, and pessimism abound ...

. He soon opened a bar using his wife's dowry, which he was forced to close because business was so poor. In later years, after parting ways politically, Scoville accused Wood of overcharging drunken bar patrons.

Rise through Tammany Hall

Despite his business failures, Wood was successful in politics. He joined the nascent Jacksonian Democratic Party, possibly influenced by his hatred of theSecond Bank of the United States

The Second Bank of the United States was the second federally authorized Hamiltonian national bank in the United States. Located in Philadelphia, Pennsylvania, the bank was chartered from February 1816 to January 1836.. The Bank's formal name, ...

, which he blamed for his father's ruin. In 1836, party leaders elevated him to membership in the fraternal-political Tammany Society

Tammany Hall, also known as the Society of St. Tammany, the Sons of St. Tammany, or the Columbian Order, was a New York City political organization founded in 1786 and incorporated on May 12, 1789 as the Tammany Society. It became the main loc ...

, the first rung on the New York Democratic ladder.

Tammany Hall

Tammany Hall, also known as the Society of St. Tammany, the Sons of St. Tammany, or the Columbian Order, was a New York City political organization founded in 1786 and incorporated on May 12, 1789 as the Tammany Society. It became the main loc ...

was split between moderates, including Wood, and a breakaway faction of radicals known as Locofocos

The Locofocos (also Loco Focos or Loco-focos) were a faction of the Democratic Party in American politics that existed from 1835 until the mid-1840s.

History

The faction, originally named the Equal Rights Party, was created in New York City as a p ...

. When the Locofocos formed an independent Equal Rights Party, Wood remained in the Tammany organization, gaining promotion into the organization's Young Men's Committee and becoming its organizing force. However, following the Panic of 1837

The Panic of 1837 was a financial crisis in the United States that touched off a major depression, which lasted until the mid-1840s. Profits, prices, and wages went down, westward expansion was stalled, unemployment went up, and pessimism abound ...

and a Locofoco food riot, Wood worked to advance radical anti-bank politics within the Young Men's Committee. Wood's move was politically prescient; in September 1837, President Martin Van Buren

Martin Van Buren ( ; nl, Maarten van Buren; ; December 5, 1782 – July 24, 1862) was an American lawyer and statesman who served as the eighth president of the United States from 1837 to 1841. A primary founder of the Democratic Party, he ...

, a Tammany Hall ally, signaled approval of Locofocoism. At a meeting later that month, the general Tammany organization voted in favor of Wood's motion to oust the Bank Democrats from the organization. Wood received a host of organization promotions.

U.S. Representative (1841–43)

1840 election

In October 1840, Wood's rise culminated with a nomination for the United States House of Representatives at just 28 years old. At this time,New York City

New York, often called New York City or NYC, is the List of United States cities by population, most populous city in the United States. With a 2020 population of 8,804,190 distributed over , New York City is also the L ...

elected its four members of the House on a single ticket. Wood campaigned on Anglophobic themes to appeal to Irish voters in the city, suggesting that "British stockjobbers" funded the Whig campaign in gold. He engaged in a war of words with ''New York American'' editor Charles King, who revealed that Wood had been found liable for $2,143.90 in overdraft fees after he fraudulently withdrew from his bank on the basis of a bookkeeping error.

In response, Wood published the statements of two of the referees in his case, a letter from the bank's Whig attorney, and a letter from his own attorney, which Wood combined to argue the bank had maligned him to help the Whig Party.

Wood and his Democratic running mates unseated the incumbent Whig ticket, though Wood received the fewest votes and only won his seat by 886 votes. The bank scandal remained a sore spot for Wood for years.

27th Congress

In Congress, Wood served on the Public Buildings and Grounds Committee. He sought out the mentorship ofHenry Clay

Henry Clay Sr. (April 12, 1777June 29, 1852) was an American attorney and statesman who represented Kentucky in both the United States Senate, U.S. Senate and United States House of Representatives, House of Representatives. He was the seven ...

, who had become estranged from the Whigs over his break with President John Tyler, and Southern Democrats like John C. Calhoun

John Caldwell Calhoun (; March 18, 1782March 31, 1850) was an American statesman and political theorist from South Carolina who held many important positions including being the seventh vice president of the United States from 1825 to 1832. He ...

, Henry A. Wise, and James K. Polk. Wood's voting record was markedly pro-Southern and pro-slavery, more so than any other New York congressman.

On economic issues, Wood was an orthodox Democrat, favoring hard money, deflation, and free trade. However, he supported federal funding in New York, including appropriations for harbor improvements, fortifications, and the Brooklyn Navy Yard. Wood was also a staunch backer of federal subsidies for Samuel F.B. Morse's experimental telegraph. He was a vocal opponent of protectionist tariffs proposed by House Ways and Means chairman Millard Fillmore

Millard Fillmore (January 7, 1800March 8, 1874) was the 13th president of the United States, serving from 1850 to 1853; he was the last to be a member of the Whig Party while in the White House. A former member of the U.S. House of Represen ...

.

Wood also lobbied the U.S. State Department for protections for Irish political prisoners, some of whom were naturalized Americans, whom the British forcibly resettled on Tasmania

)

, nickname =

, image_map = Tasmania in Australia.svg

, map_caption = Location of Tasmania in AustraliaCoordinates:

, subdivision_type = Country

, subdi ...

.

1842 election

Wood expected to run for re-election in 1842, but the New York City district was split into four separate districts by a congressional mandate. Wood lived in the new fifth district, also home to popular incumbentJohn McKeon

John McKeon (March 29, 1808, Albany, New York – November 22, 1883, New York City) was an American lawyer and politician from New York. From 1835 to 1837, and 1841 to 1843, he served two non-consecutive terms in the U.S. House of Representativ ...

. To avoid facing McKeon in a primary, Wood relocated to a strong Whig district, the sixth, where instead he faced incumbent James I. Roosevelt

James John Roosevelt, known as James I. (December 14, 1795 – April 5, 1875) was an American politician, jurist, businessman, and member of the Roosevelt family. From 1841 to 1843, he served one term in the U.S. House of Representatives.

Early l ...

and former Congressman Ely Moore

Ely Moore (July 4, 1798 – January 27, 1860) was an American newspaperman and labor leader who served two terms as a Jacksonian U.S. Representative from New York from 1835 to 1839.

Moore was the first labor leader of a national scope in Americ ...

for the Democratic nomination. After Roosevelt withdrew, Wood won a one-vote plurality in the primary, but fell short of the required majority. Moore withdrew in favor of McKeon, who had lost the nomination in his original district. McKeon won, and Wood covertly undermined him in the general election, invoking McKeon's Irish heritage and suggesting McKeon was a secret abolitionist. McKeon lost to Whig Hamilton Fish

Hamilton Fish (August 3, 1808September 7, 1893) was an American politician who served as the 16th Governor of New York from 1849 to 1850, a United States Senator from New York from 1851 to 1857 and the 26th United States Secretary of State fro ...

.

Return to business

In need of funds and expecting his first child, Wood left politics after 1842 to reopen his ship chandler firm on the

In need of funds and expecting his first child, Wood left politics after 1842 to reopen his ship chandler firm on the East River

The East River is a saltwater tidal estuary in New York City. The waterway, which is actually not a river despite its name, connects Upper New York Bay on its south end to Long Island Sound on its north end. It separates the borough of Quee ...

, announcing to his friends that he was "entirely out of politics."

To accrue necessary capital, Wood begged Henry A. Wise for a patronage appointment as the State Department's local despatch agent, despite previously having tried to abolish the role when he was a congressman. Though Secretary of State Abel Upshur

Abel Parker Upshur (June 17, 1790 – February 28, 1844) was a lawyer, planter, slaveowner, judge and politician from the Eastern Shore of Virginia. Active in Virginia state politics for decades, with a brother and a nephew who became distinguis ...

refused, he was soon killed in an accident aboard the USS ''Princeton'' and succeeded by John C. Calhoun, who granted Wood the appointment on May 8, 1844.

With his government job as a subsidy and political power base, Wood expanded his business and rented a new home in upper Manhattan with three servants. Except for his efforts on behalf of presidential nominee James K. Polk and in defense of his own patronage position, he remained largely outside politics.

1844 presidential election

In advance of the1844 Democratic National Convention

The 1844 Democratic National Convention was a presidential nominating convention held in Baltimore, Maryland from May 27 through 30. The convention nominated former Governor James K. Polk of Tennessee for president and former Senator George M. ...

, which was expected to be a showdown between Calhoun and Martin Van Buren, Wood acted as a double agent on behalf of Van Buren. Calhoun supporters, seeking to peel Tammany away from Van Buren, invited Wood to strategy meetings and sought his advice on courting New York delegates. However, Wood covertly passed this information to Van Buren. Though Calhoun never found Wood out, the affair left Van Buren suspicious of Wood's character and the former President's son, John Van Buren, became Wood's political rival for the next two decades.

After the nomination went to dark horse James K. Polk, Wood renewed their friendship and launched into a campaign for Polk in New York City, New Jersey, and the Southern Tier

The Southern Tier is a geographic subregion of the broader Upstate New York region of New York State, consisting of counties west of the Catskill Mountains in Delaware County and geographically situated along or very near the northern border ...

. Wood used his political connections to Polk to save his patronage job under new Secretary of State James Buchanan

James Buchanan Jr. ( ; April 23, 1791June 1, 1868) was an American lawyer, diplomat and politician who served as the 15th president of the United States from 1857 to 1861. He previously served as secretary of state from 1845 to 1849 and repr ...

.

Real estate

Wood massively expanded his wealth by entering the real estate market, at first by accident. In 1848, using his second wife's modest fortune, he took out a $4,000 mortgage on a 150 acre plot on Bloomingdale Road. As New York's population boomed and development hastened, real estate values skyrocketed. Along with subsequent purchases from the same estate, Wood accumulated a property worth over $650,000. Using this property as security, he engaged in a series of successful purchases in nearly every ward of Manhattan.William Tweed

William Magear Tweed (April 3, 1823 – April 12, 1878), often erroneously referred to as William "Marcy" Tweed (see below), and widely known as "Boss" Tweed, was an American politician most notable for being the political boss of Tammany ...

later said of Wood, "I never yet went to get a corner lot that I didn't find Wood had got in ahead of me."

In 1852, Wood expanded his holdings to San Francisco

San Francisco (; Spanish for " Saint Francis"), officially the City and County of San Francisco, is the commercial, financial, and cultural center of Northern California. The city proper is the fourth most populous in California and 17t ...

. By 1855, his growing fortune was estimated at $200,000; in 1861, $500,000. Wood himself reported personal holdings of $1,200,000 at the 1860 census ($ in dollars).

Gold Rush and ''Cater'' affair

In October 1848, in the early stages of theCalifornia Gold Rush

The California Gold Rush (1848–1855) was a gold rush that began on January 24, 1848, when gold was found by James W. Marshall at Sutter's Mill in Coloma, California. The news of gold brought approximately 300,000 people to California f ...

, Wood and four other partners chartered a barque

A barque, barc, or bark is a type of sailing vessel with three or more masts having the fore- and mainmasts rigged square and only the mizzen (the aftmost mast) rigged fore and aft. Sometimes, the mizzen is only partly fore-and-aft rigged, b ...

, the ''John C. Cater'', to sell goods and equipment in San Francisco. The goods were sold at inflated prices, and the ''Cater'' maintained a profitable trade transporting passengers and lumber between Oregon

Oregon () is a U.S. state, state in the Pacific Northwest region of the Western United States. The Columbia River delineates much of Oregon's northern boundary with Washington (state), Washington, while the Snake River delineates much of it ...

and San Francisco.

It was later discovered that Wood defrauded his brother-in-law, Edward E. Marvine, in order to obtain the necessary start-up capital for the ''Cater''. Wood presented his brother-in-law with a fraudulent letter, purportedly from a "Thomas O'Larkin" in Monterey, California

Monterey (; es, Monterrey; Ohlone: ) is a city located in Monterey County on the southern edge of Monterey Bay on the U.S. state of California's Central Coast. Founded on June 3, 1770, it functioned as the capital of Alta California under b ...

, suggesting the venture. Marvine was convinced by this letter and convinced three more investors to join. Marvine later sued Wood for $20,000 in fraud. In 1851, Wood was indicted by a grand jury, but the judges quashed the charges because the statute of limitations expired a day before the court was to rule on the matter. Wood was accused, without substantiation, of bribing the Whig district attorney with $700 to delay the charges until the statute of limitations expired. In 1855, the New York Supreme Court

The Supreme Court of the State of New York is the trial-level court of general jurisdiction in the New York State Unified Court System. (Its Appellate Division is also the highest intermediate appellate court.) It is vested with unlimited civ ...

ordered Wood to pay Marvine $8,000 and the other partners $5,635.40. Wood filed an appeal that dragged on for another six years.

During the case, Wood maintained his innocence and brought a libel suit against the ''New York Sun

''The New York Sun'' is an American online newspaper published in Manhattan; from 2002 to 2008 it was a daily newspaper distributed in New York City. It debuted on April 16, 2002, adopting the name, motto, and masthead of the earlier New York ...

'' for prematurely printing details of Marvine's deposition.

Mayor of New York City

In the words of biographer Jerome Mushkat, Mayor Wood was "a unique figure, New York's first modern mayor, a city builder, and the prototype for later municipal leaders, a man who anticipated much of what became the urban Progressive Movement." His mayoralty was marked by his push for home rule and charter reform, as well as accusations of corruption in city government by his opponents. Wood was the first New York City mayor linked toTammany Hall

Tammany Hall, also known as the Society of St. Tammany, the Sons of St. Tammany, or the Columbian Order, was a New York City political organization founded in 1786 and incorporated on May 12, 1789 as the Tammany Society. It became the main loc ...

.

1850 campaign

Wood was nominated for Mayor of New York City for the first time in 1850 with the support of "Soft Shell Democrats" who supported the 1849 state Democratic platform, which called for protection of slavery where it existed but recognized Congress's right to prevent its extension to new American territories. He was defeated by Ambrose C. Kingsland in a landslide for the Whig Party.1854 campaign

Wood began organizing his political return in November 1853, courting both the Soft and Hard factions in opposition to Free Soil Democrats, who opposed any extension of slavery whatsoever. He also sought influence in the secretive newKnow-Nothing

The Know Nothing party was a nativist political party and movement in the United States in the mid-1850s. The party was officially known as the "Native American Party" prior to 1855 and thereafter, it was simply known as the "American Party". ...

nativist movement, despite his base of support in the city's immigrant communities.

Wood was easily nominated for a second time, though a faction of Hard Democrats nominated Wilson J. Hunt. Wood's campaign was nearly upended by his Know-Nothing involvement, but he survived the accusations to win with just 33.6% of the vote.

First term (1855–56)

In his first two-year term, Wood sought to strengthen the office of mayor and establish "one-man rule" in advance of proposals to unilaterally modernize the city's economy, improve its public works, and reduce wealth inequality. He was very popular in New York and throughout the country, and gained the nickname "the Model Mayor." However, his attempts at reform were quickly overshadowed by failure to answer accusations of corruption in his handling of the police force. His political base was eroded entirely in the 1855 elections, leaving Wood on the defensive for the remainder of his term. Nonetheless, his vision for the mayoralty as a powerful central executive and his campaign for greater home rule for New York City came to define the city's politics for generations. He embarked on several large spending programs, including modernizing the city's wharfs by replacing wooden structures with stone, new safety features for the city's railways, construction of the already-plannedCentral Park

Central Park is an urban park in New York City located between the Upper West and Upper East Sides of Manhattan. It is the fifth-largest park in the city, covering . It is the most visited urban park in the United States, with an estimated ...

, and expansion of the city's grid plan

In urban planning, the grid plan, grid street plan, or gridiron plan is a type of city plan in which streets run at right angles to each other, forming a grid.

Two inherent characteristics of the grid plan, frequent intersections and orthogon ...

. Attempts to crack down on vice were largely abandoned for political and practical reasons.

1856 gubernatorial campaign and re-election

Wood was an early supporter ofJames Buchanan

James Buchanan Jr. ( ; April 23, 1791June 1, 1868) was an American lawyer, diplomat and politician who served as the 15th president of the United States from 1857 to 1861. He previously served as secretary of state from 1845 to 1849 and repr ...

for the 1856 Democratic nomination and attempted to parlay this support into a nomination on Buchanan's ticket for Governor of New York

The governor of New York is the head of government of the U.S. state of New York. The governor is the head of the executive branch of New York's state government and the commander-in-chief of the state's military forces. The governor h ...

. However, an expected endorsement by Buchanan never materialized and Wood was seen as too extreme by state leaders. Both the Hard and Soft factions unified on the candidacy of Amasa J. Parker

Amasa Junius Parker (June 2, 1807May 13, 1890) was an attorney, politician and judge from New York. He is most notable for his service as a member of the New York State Assembly (1834), a U.S. Representative (1837-1839), and a justice of the New ...

, who ultimately lost the election.

Instead, Wood stood for re-election as mayor on a platform of charter reform, in defiance of a one-term tradition. The general election campaign was marked by personal attacks and street violence committed by the various political gangs in the city. On election day, Wood furloughed or relieved many police officers of duty, allowing his own gang, the Dead Rabbits

The Dead Rabbits was the name of an Irish American criminal street gang active in Lower Manhattan in the 1830s to 1850s. The Dead Rabbits were so named after a dead rabbit was thrown into the center of the room during a gang meeting, prompting s ...

, to menace voters and steal ballot boxes. He won the race with 44.6% of the vote, though he trailed Buchanan by a wide margin due to fractures in the city party. Despite his evident abuse of police powers and encouragement of violence, a grand jury declined to indict Wood on the grounds that such practices were common in the city's history and at the time.

Second term (1857)

In Wood's second term, his control over Tammany Hall unraveled and his handling of the police force boiled over in the New York City Police riot and Dead Rabbits riot.

In April, the Republican legislature passed a new City Charter which truncated Wood's current term to one year, a Police Reform Act dissolving Wood's Municipal police in favor of a Metropolitan state unit, and an Excise Act implementing restrictive liquor licensing throughout the state. Wood committed himself to resisting the Police Reform Act and maintaining his own Municipal police, culminating in a police riot and Wood's orchestrated arrest on June 16.

In Wood's second term, his control over Tammany Hall unraveled and his handling of the police force boiled over in the New York City Police riot and Dead Rabbits riot.

In April, the Republican legislature passed a new City Charter which truncated Wood's current term to one year, a Police Reform Act dissolving Wood's Municipal police in favor of a Metropolitan state unit, and an Excise Act implementing restrictive liquor licensing throughout the state. Wood committed himself to resisting the Police Reform Act and maintaining his own Municipal police, culminating in a police riot and Wood's orchestrated arrest on June 16.

1857 election

In the December 1857 election, Tammany joined with Republicans and Know-Nothings in endorsing Daniel F. Tiemann over Wood. The economic devastation of thePanic of 1857

The Panic of 1857 was a financial panic in the United States caused by the declining international economy and over-expansion of the domestic economy. Because of the invention of the telegraph by Samuel F. Morse in 1844, the Panic of 1857 was ...

dominated the campaign, and Wood pursued public works programs to provide jobs and food for the city's poor citizens.

Wood was denied a third successive term by a narrow margin of 3,000 votes.

Return to mayoralty and support for Confederacy

Wood served a third mayoral term in 1860 and 1861. Wood was one of many New York Democrats sympathetic to the Confederacy, called ' Copperheads' by the staunch Unionists. In 1860, at a meeting to choose New York's delegates to the Democratic convention in Charleston, S.C., Wood outlined his case against the abolitionist cause and the "Black Republicans" who supported it. He was of the opinion that "until we have provided and cared for the oppressed laboring man in our own midst, we should not extend our sympathy to the laboring men of other States." In January 1861, Wood suggested to theNew York City Council

The New York City Council is the lawmaking body of New York City. It has 51 members from 51 council districts throughout the five boroughs.

The council serves as a check against the mayor in a mayor-council government model, the performance of ...

that New York secede and declare itself a free city in order to continue its profitable cotton trade with the Confederacy.

Wood's Democratic machine was concerned with maintaining the revenues that maintained the patronage, which depended on Southern cotton. Wood's suggestion was greeted with derision by the Common Council. Tammany Hall

Tammany Hall, also known as the Society of St. Tammany, the Sons of St. Tammany, or the Columbian Order, was a New York City political organization founded in 1786 and incorporated on May 12, 1789 as the Tammany Society. It became the main loc ...

was highly factionalized until after the Civil War. Wood and his faction cocreated and he headed his own organization named Mozart Hall. New York City commercial interests wanted to retain their relations with the South, but within the framework of the Constitution.

Return to U.S. House

Subsequent to serving his third mayoral term, Wood served again in the House of Representatives from 1863 to 1865, then again from 1867 until his death inHot Springs, Arkansas

Hot Springs is a resort city in the state of Arkansas and the county seat of Garland County. The city is located in the Ouachita Mountains among the U.S. Interior Highlands, and is set among several natural hot springs for which the city is n ...

on February 13, 1881.

Civil War and Reconstruction

Wood was one of the main opponents of theThirteenth Amendment to the United States Constitution

The Thirteenth Amendment (Amendment XIII) to the United States Constitution abolished slavery and involuntary servitude, except as punishment for a crime. The amendment was passed by the Senate on April 8, 1864, by the House of Representative ...

which abolished slavery and was critical in blocking the measure in the House when it first came up for a vote in June 1864. Wood attacked anti-slavery War Democrats as having "a white man's face on the body of a negro," and supported state-level Democratic Party platforms that advocated constitutional amendments protecting slavery. He argued that the amendment "strikes at property," and took the power of regulating slavery away from the states, where it rightfully belonged.

On January 15, 1868, Wood was censured for the use of unparliamentary language. During debate on the floor the House of Representatives, Wood called a piece of legislation "A monstrosity, a measure the most infamous of the many infamous acts of this infamous Congress." An uproar immediately followed this utterance, and Wood was not permitted to continue. This was followed by a motion by Henry L. Dawes

Henry Laurens Dawes (October 30, 1816February 5, 1903) was an attorney and politician, a Republican United States Senator and United States Representative from Massachusetts. He is notable for the Dawes Act (1887), which was intended to stimul ...

to censure Wood, which passed by a vote of 114-39.

Notwithstanding his censure, Wood still managed to defeat Dr. Francis Thomas, the Republican candidate, by a narrow margin in the election of that year.

Wood served as chairman for the Committee on Ways and Means

The Committee on Ways and Means is the chief tax-writing committee of the United States House of Representatives. The committee has jurisdiction over all taxation, tariffs, and other revenue-raising measures, as well as a number of other program ...

in both the 45th and 46th Congress (1877–1881).

Personal life

Personality and appearance

Wood was slightly over six feet, making him tall for his time. Contemporaries described him as "strikingly handsome," but he dressed plainly and showed little emotion. Wood's biographer Jerome Mushkat describes him as a totally self-reliant man of "soaring ambition" and "an almost dictatorial obsession to control men and events."Marriages and family

Wood's brother Benjamin Wood purchased the ''New York Daily News

The New York ''Daily News'', officially titled the ''Daily News'', is an American newspaper based in Jersey City, NJ. It was founded in 1919 by Joseph Medill Patterson as the ''Illustrated Daily News''. It was the first U.S. daily printed in ...

'' (not to be confused with the current ''New York Daily News

The New York ''Daily News'', officially titled the ''Daily News'', is an American newspaper based in Jersey City, NJ. It was founded in 1919 by Joseph Medill Patterson as the ''Illustrated Daily News''. It was the first U.S. daily printed in ...

'', which was founded in 1919), supported Stephen A. Douglas, and was elected to Congress

A congress is a formal meeting of the representatives of different countries, constituent states, organizations, trade unions, political parties, or other groups. The term originated in Late Middle English to denote an encounter (meeting of ...

, where he made a name as an opponent of pursuing the American Civil War

The American Civil War (April 12, 1861 – May 26, 1865; also known by Names of the American Civil War, other names) was a civil war in the United States. It was fought between the Union (American Civil War), Union ("the North") and t ...

.

Wood was married three times and had 16 children, seven from his second marriage to Anna Richardson and nine from his third marriage to Alice Mills. Among his children with Mills were Henry Alexander Wise Wood

Henry Alexander Wise Wood (March 1, 1866 - April 9, 1939) was an American inventor of a high speed newspaper press and member of the Naval Consulting Board. His father Fernando Wood was mayor of New York City and a Democratic Party member of Cong ...

.

His first marriage (1831–39) to Anna Taylor of Philadelphia ended in divorce upon Wood's discovery of her frequent adultery. Their marriage was childless and a court decreed that Anna could not marry again during Wood's lifetime. He never spoke of her again, but a political enemy later claimed she had become an alcoholic prostitute.

In 1841 he married Anna Dole Richardson, who died in 1859. Anna was a direct descendant of William Penn

William Penn ( – ) was an English writer and religious thinker belonging to the Religious Society of Friends (Quakers), and founder of the Province of Pennsylvania, a North American colony of England. He was an early advocate of democracy a ...

through her mother, and her father, Judge Joseph L. Richardson, was well-connected with upstate politicians including President Van Buren, Silas Wright

Silas Wright Jr. (May 24, 1795 – August 27, 1847) was an American attorney and Democratic politician. A member of the Albany Regency, he served as a member of the United States House of Representatives, New York State Comptroller, United Stat ...

, and William C. Bouck

William Christian Bouck (January 7, 1786 – April 19, 1859) was an American politician from New York. He was the 13th Governor of New York from 1843 to 1844.

A native of Fultonham, New York, Bouck was educated in the local schools while w ...

. During his second marriage, having built a second fortune, Wood and his wife joined the Protestant Episcopal Church

The Episcopal Church, based in the United States with additional dioceses elsewhere, is a member church of the worldwide Anglican Communion. It is a mainline Protestant denomination and is divided into nine provinces. The presiding bishop of ...

.

In 1860 he married Alice Fenner Mills, the 16-year-old daughter of retired Republican financier and railroad executive C. Drake Mills.

Ancestry

The Wood family traces its lineage in America to around 1670, when Henry Wood, a carpenter and Quaker, migrated fromWales

Wales ( cy, Cymru ) is a country that is part of the United Kingdom. It is bordered by England to the east, the Irish Sea to the north and west, the Celtic Sea to the south west and the Bristol Channel to the south. It had a population in ...

to Newport, Rhode Island

Newport is an American seaside city on Aquidneck Island in Newport County, Rhode Island. It is located in Narragansett Bay, approximately southeast of Providence, south of Fall River, Massachusetts, south of Boston, and northeast of New Yor ...

. He later moved his family to West Jersey

West Jersey and East Jersey were two distinct parts of the Province of New Jersey. The political division existed for 28 years, between 1674 and 1702. Determination of an exact location for a border between West Jersey and East Jersey was ofte ...

, where he established a homestead along the Delaware River.

Fernando Wood's grandfather Henry Wood was born in 1758 and served in the American Revolution as a captain. He was wounded at the battles of Germantown Germantown or German Town may refer to:

Places

Australia

* Germantown, Queensland, a locality in the Cassowary Coast Region

United States

* Germantown, California, the former name of Artois, a census-designated place in Glenn County

* G ...

and Yorktown.

Little is known about Wood's maternal line.

Death and legacy

Wood died in Hot Springs, Arkansas on February 13, 1881. He was buried in Trinity Church Cemetery, in New York, N.Y. InSteven Spielberg

Steven Allan Spielberg (; born December 18, 1946) is an American director, writer, and producer. A major figure of the New Hollywood era and pioneer of the modern blockbuster, he is the most commercially successful director of all time. Sp ...

's ''Lincoln'', Wood is portrayed by Lee Pace

Lee Grinner Pace (born March 25, 1979) is an American actor. He is known for starring as Thranduil the Elvenking in ''The Hobbit'' trilogy and as Joe MacMillan in the AMC period drama television series '' Halt and Catch Fire''. He has also a ...

as a leading opponent of the president and of the Thirteenth Amendment.

See also

*List of United States Congress members who died in office (1790–1899)

The following is a list of United States senators and representatives who died of natural or accidental causes, or who killed themselves, while serving their terms between 1790 and 1899. For a list of members of Congress who were killed while in ...

*List of United States representatives expelled, censured, or reprimanded

The United States Constitution (Article 1, Section 5) gives the House of Representatives the power to expel any member by a two-thirds vote. Expulsion of a Representative is rare: only five members of the House have been expelled in its history. ...

Notes

References

Bibliography

* * *Further reading

* Herbert Asbury, ''The Gangs of New York,'' 1927 * Journal of the House of Representatives of the United States, 1867–1868pp. 193-196

* Oakes, James. ''Freedom National: The Destruction of Slavery in the United States (1861–1865)''. W.W. Norton & Company, 2013.

External links

Mr. Lincoln and New York: Fernando Wood

* ttp://www.spartacus-educational.com/USACWwood.htm Fernando Woodbr>Gregory Christiano surveys Fernando Wood, the rival police forces, gang wars and the Panic of 1857: 'Introduction to a turbulent period in New York City history."

at the Biographical Directory of The United States Congress , - , - , - , - , - , - , - , - , - {{DEFAULTSORT:Wood, Fernando 1812 births 1881 deaths 19th-century American politicians American people of Welsh descent American proslavery activists American white supremacists Censured or reprimanded members of the United States House of Representatives Copperheads (politics) Democratic Party members of the United States House of Representatives from New York (state) Leaders of Tammany Hall Mayors of New York City People of New York (state) in the American Civil War Politicians from Philadelphia