Farthest South on:

[Wikipedia]

[Google]

[Amazon]

Farthest South refers to the most southerly

Farthest South refers to the most southerly

Although Portuguese by birth, Ferdinand Magellan transferred his allegiance to

Although Portuguese by birth, Ferdinand Magellan transferred his allegiance to

Sir Francis Drake sailed from Plymouth on 15 November 1577, in command of a fleet of five ships under his flagship ''Pelican'', later renamed the ''Golden Hinde''. His principal objective was plunder, not exploration; his initial targets were the unfortified Spanish towns on the Pacific coasts of Chile and Peru. Following Magellan's route, Drake reached Puerto San Julian on 20 June. After nearly two months in harbour, Drake left the port with a reduced fleet of three ships and a small

Sir Francis Drake sailed from Plymouth on 15 November 1577, in command of a fleet of five ships under his flagship ''Pelican'', later renamed the ''Golden Hinde''. His principal objective was plunder, not exploration; his initial targets were the unfortified Spanish towns on the Pacific coasts of Chile and Peru. Following Magellan's route, Drake reached Puerto San Julian on 20 June. After nearly two months in harbour, Drake left the port with a reduced fleet of three ships and a small

The second of

The second of

In 1822 Weddell, again in command of ''Jane'' and this time accompanied by a smaller ship, the cutter ''Beaufoy'', set sail for the south with instructions from his employers that, should the sealing prove barren, he was to "investigate beyond the track of former navigators". This suited Weddell's exploring instincts, and he equipped his vessel with chronometers, thermometers, compasses, barometers and charts. In January 1823 he probed the waters between the South Sandwich Islands and the South Orkney Islands, looking for new land. Finding none, he turned southward down the 40°W meridian, deep into the sea that now bears his name. The season was unusually calm, and Weddell reported that "not a particle of ice of any description was to be seen". On 20 February 1823, he reached a new Farthest South of 74°15'S, three degrees beyond Cook's former record. Unaware that he was close to land, Weddell decided to return northward from this point, convinced that the sea continued as far as the South Pole.

Another two days' sailing would likely have brought him within sight of

In 1822 Weddell, again in command of ''Jane'' and this time accompanied by a smaller ship, the cutter ''Beaufoy'', set sail for the south with instructions from his employers that, should the sealing prove barren, he was to "investigate beyond the track of former navigators". This suited Weddell's exploring instincts, and he equipped his vessel with chronometers, thermometers, compasses, barometers and charts. In January 1823 he probed the waters between the South Sandwich Islands and the South Orkney Islands, looking for new land. Finding none, he turned southward down the 40°W meridian, deep into the sea that now bears his name. The season was unusually calm, and Weddell reported that "not a particle of ice of any description was to be seen". On 20 February 1823, he reached a new Farthest South of 74°15'S, three degrees beyond Cook's former record. Unaware that he was close to land, Weddell decided to return northward from this point, convinced that the sea continued as far as the South Pole.

Another two days' sailing would likely have brought him within sight of

The expedition left England on 30 September 1839, and after a voyage that was slowed by the many stops required to carry out work on magnetism, it reached

The expedition left England on 30 September 1839, and after a voyage that was slowed by the many stops required to carry out work on magnetism, it reached

The Norwegian-born

The Norwegian-born

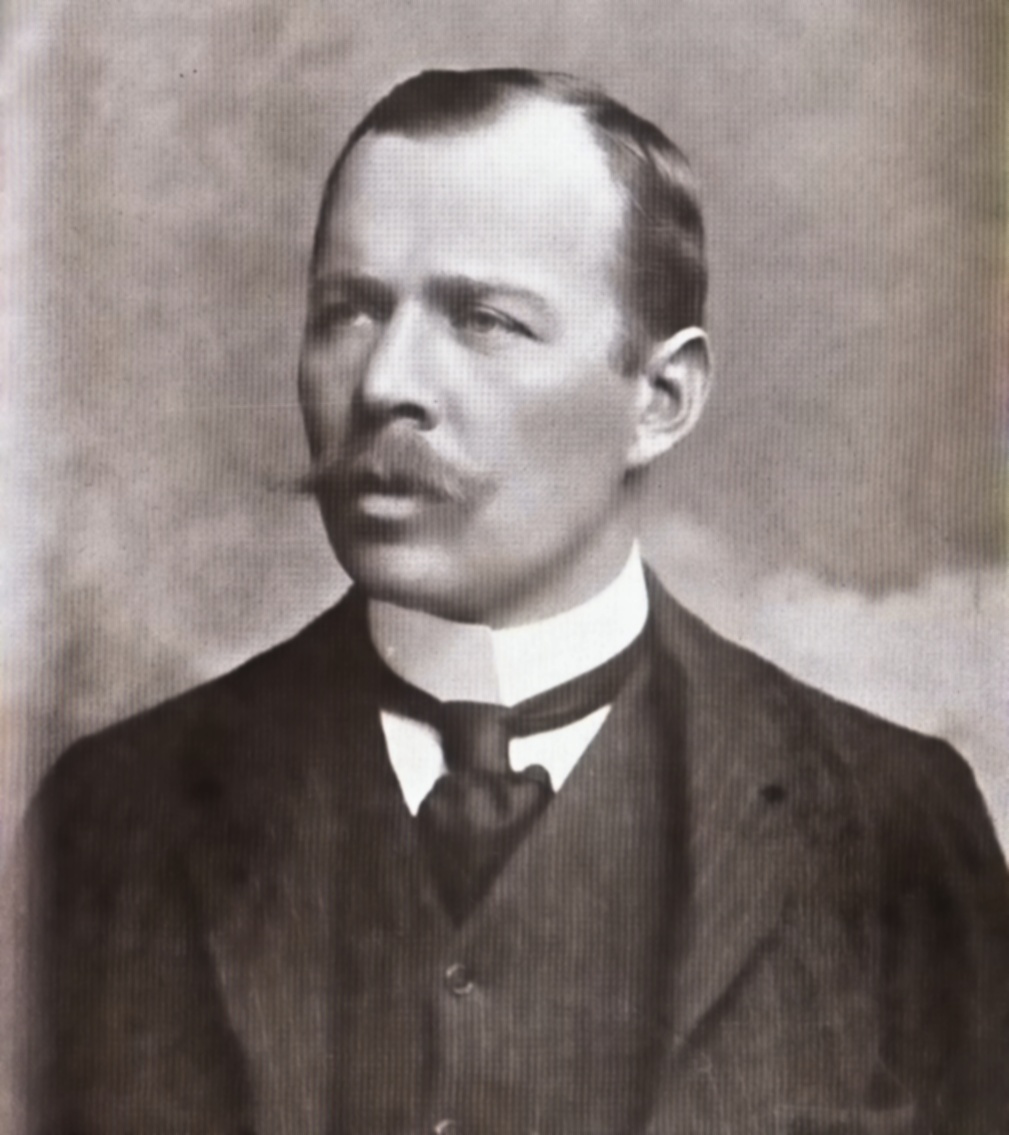

After his share in the Farthest South achievement of the Discovery Expedition,

After his share in the Farthest South achievement of the Discovery Expedition,

In the wake of Shackleton's near miss, Robert Scott organised the Terra Nova Expedition, 1910–1913, in which securing the South Pole for the

In the wake of Shackleton's near miss, Robert Scott organised the Terra Nova Expedition, 1910–1913, in which securing the South Pole for the

After Scott's retreat from the pole in January 1912, the location remained unvisited for nearly 18 years. On 28 November 1929, US Navy

After Scott's retreat from the pole in January 1912, the location remained unvisited for nearly 18 years. On 28 November 1929, US Navy

Farthest South refers to the most southerly

Farthest South refers to the most southerly latitude

In geography, latitude is a coordinate that specifies the north– south position of a point on the surface of the Earth or another celestial body. Latitude is given as an angle that ranges from –90° at the south pole to 90° at the north ...

reached by explorers before the first successful expedition to the South Pole

The South Pole, also known as the Geographic South Pole, Terrestrial South Pole or 90th Parallel South, is one of the two points where Earth's axis of rotation intersects its surface. It is the southernmost point on Earth and lies antipod ...

in 1911. Significant steps on the road to the pole were the discovery of lands south of Cape Horn

Cape Horn ( es, Cabo de Hornos, ) is the southernmost headland of the Tierra del Fuego archipelago of southern Chile, and is located on the small Hornos Island. Although not the most southerly point of South America (which are the Diego Ramí ...

in 1619, Captain James Cook

James Cook (7 November 1728 Old Style date: 27 October – 14 February 1779) was a British explorer, navigator, cartographer, and captain in the British Royal Navy, famous for his three voyages between 1768 and 1779 in the Pacific Ocean and ...

's crossing of the Antarctic Circle

The Antarctic Circle is the most southerly of the five major circles of latitude that mark maps of Earth. The region south of this circle is known as the Antarctic, and the zone immediately to the north is called the Southern Temperate Zone. So ...

in 1773, and the earliest confirmed sightings of the Antarctic

The Antarctic ( or , American English also or ; commonly ) is a polar region around Earth's South Pole, opposite the Arctic region around the North Pole. The Antarctic comprises the continent of Antarctica, the Kerguelen Plateau and othe ...

mainland in 1820. From the late 19th century onward, the quest for Farthest South latitudes became in effect a race to reach the pole, which culminated in Roald Amundsen

Roald Engelbregt Gravning Amundsen (, ; ; 16 July 1872 – ) was a Norwegian explorer of polar regions. He was a key figure of the period known as the Heroic Age of Antarctic Exploration.

Born in Borge, Østfold, Norway, Amundsen beg ...

's success in December 1911.

In the years before reaching the pole was a realistic objective, other motives drew adventurers southward. Initially, the driving force was the discovery of new trade routes between Europe and the Far East. After such routes had been established and the main geographical features of the Earth had been broadly mapped, the lure for mercantile adventurers was the great fertile continent of "Terra Australis

(Latin: '"Southern Land'") was a hypothetical continent first posited in antiquity and which appeared on maps between the 15th and 18th centuries. Its existence was not based on any survey or direct observation, but rather on the idea that ...

" which, according to myth, lay hidden in the south. Belief in the existence of this supposed land of plenty persisted well into the 18th century; explorers were reluctant to accept the truth that slowly emerged, of a cold, harsh environment in the lands of the Southern Ocean

The Southern Ocean, also known as the Antarctic Ocean, comprises the southernmost waters of the World Ocean, generally taken to be south of 60° S latitude and encircling Antarctica. With a size of , it is regarded as the second-smal ...

.

James Cook's voyages of 1772–1775 demonstrated conclusively the likely hostile nature of any hidden lands. This caused a shift of emphasis in the first half of the 19th century, away from trade and towards sealing and whaling, and then exploration and discovery. After the first overwintering on continental Antarctica

Antarctica () is Earth's southernmost and least-populated continent. Situated almost entirely south of the Antarctic Circle and surrounded by the Southern Ocean, it contains the geographic South Pole. Antarctica is the fifth-largest cont ...

in 1898–99 (Adrien de Gerlache

Baron Adrien Victor Joseph de Gerlache de Gomery (; 2 August 1866 – 4 December 1934) was a Belgian officer in the Belgian Royal Navy who led the Belgian Antarctic Expedition of 1897–99.

Early years

Born in Hasselt in eastern Belgium as th ...

), the prospect of reaching the South Pole appeared realistic, and the race for the pole began. The British were pre-eminent in this endeavour, which was characterised by the rivalry between Robert Falcon Scott

Captain Robert Falcon Scott, , (6 June 1868 – c. 29 March 1912) was a British Royal Navy officer and explorer who led two expeditions to the Antarctic regions: the ''Discovery'' expedition of 1901–1904 and the ill-fated ''Terra Nov ...

and Ernest Shackleton

Sir Ernest Henry Shackleton (15 February 1874 – 5 January 1922) was an Anglo-Irish Antarctic explorer who led three British expeditions to the Antarctic. He was one of the principal figures of the period known as the Heroic Age o ...

during the Heroic Age of Antarctic Exploration

The Heroic Age of Antarctic Exploration was an era in the exploration of the continent of Antarctica which began at the end of the 19th century, and ended after the First World War; the Shackleton–Rowett Expedition of 1921–1922 is often ci ...

. Shackleton's efforts fell short; Scott reached the pole in January 1912 only to find that he had been beaten by the Norwegian Amundsen.

Early voyagers

In 1494, the principal maritime powers, Portugal and Spain, signed a treaty which drew a line down the middle of theAtlantic Ocean

The Atlantic Ocean is the second-largest of the world's five oceans, with an area of about . It covers approximately 20% of Earth's surface and about 29% of its water surface area. It is known to separate the " Old World" of Africa, Europe ...

and allocated all trade routes to the east of the line to Portugal. That gave Portugal dominance of the only known route to the east–via the Cape of Good Hope

The Cape of Good Hope ( af, Kaap die Goeie Hoop ) ;''Kaap'' in isolation: pt, Cabo da Boa Esperança is a rocky headland on the Atlantic coast of the Cape Peninsula in South Africa.

A common misconception is that the Cape of Good Hope is ...

and Indian Ocean

The Indian Ocean is the third-largest of the world's five oceanic divisions, covering or ~19.8% of the water on Earth's surface. It is bounded by Asia to the north, Africa to the west and Australia to the east. To the south it is bounded by ...

, which left Spain, and later other countries, to seek a western route to the Pacific

The Pacific Ocean is the largest and deepest of Earth's five oceanic divisions. It extends from the Arctic Ocean in the north to the Southern Ocean (or, depending on definition, to Antarctica) in the south, and is bounded by the contine ...

. The exploration of the south began as part of the search for such a route.

Unlike the Arctic, there is no evidence of human visitation or habitation in 'Antarctica' or the islands around it prior to European exploration. However, the most southerly parts of South America were already inhabited by tribes such as the Selk'nam/Ona, the Yagán/Yámana, the Alacaluf and the Haush

The Haush or Manek'enk were an indigenous people who lived on the Mitre Peninsula of the Isla Grande de Tierra del Fuego. They were related culturally and linguistically to the Ona or Selk'nam people who also lived on the Isla Grande de Tierra ...

. The Haush in particular made regular trips to Isla de los Estados

Isla de los Estados (English: Staten Island, from the Dutch ''Stateneiland'') is an Argentine island that lies off the eastern extremity of Tierra del Fuego, from which it is separated by the Le Maire Strait. It was named after the Netherlands ...

, which was from the main island of Tierra del Fuego

Tierra del Fuego (, ; Spanish for "Land of the Fire", rarely also Fireland in English) is an archipelago off the southernmost tip of the South American mainland, across the Strait of Magellan. The archipelago consists of the main island, Isla ...

, suggesting that some of them may have been capable of reaching the islands near Cape Horn

Cape Horn ( es, Cabo de Hornos, ) is the southernmost headland of the Tierra del Fuego archipelago of southern Chile, and is located on the small Hornos Island. Although not the most southerly point of South America (which are the Diego Ramí ...

. Fuegian Indian artefacts and canoe remnants have also been discovered on the Falkland Islands

The Falkland Islands (; es, Islas Malvinas, link=no ) is an archipelago in the South Atlantic Ocean on the Patagonian Shelf. The principal islands are about east of South America's southern Patagonian coast and about from Cape Dubouze ...

, suggesting the capacity for even longer sea journeys. Chilean scientists have claimed that Amerinds visited the South Shetland Islands

The South Shetland Islands are a group of Antarctic islands with a total area of . They lie about north of the Antarctic Peninsula, and between southwest of the nearest point of the South Orkney Islands. By the Antarctic Treaty of 1 ...

, due to stone artifacts recovered from bottom-sampling operations in Admiralty Bay, King George Island, and Discovery Bay, Greenwich Island; however, the artifacts—two arrowheads—were later found to have been planted, possibly to reinforce Chilean claims to the area.

While the natives of Tierra del Fuego were not capable of true oceanic travel, there is some evidence of Polynesia

Polynesia () "many" and νῆσος () "island"), to, Polinisia; mi, Porinihia; haw, Polenekia; fj, Polinisia; sm, Polenisia; rar, Porinetia; ty, Pōrīnetia; tvl, Polenisia; tkl, Polenihia (, ) is a subregion of Oceania, made up of ...

n visits to some of the sub antarctic islands to the south of New Zealand, although these are further from Antarctica than South America. There are also remains of a Polynesian settlement dating back to the 13th century on Enderby Island

Enderby Island is part of New Zealand's uninhabited Auckland Islands archipelago, south of mainland New Zealand. It is situated just off the northern tip of Auckland Island, the largest island in the archipelago.

Geography and geology

Enderby ...

in the Auckland Islands

The Auckland Islands (Māori: ''Motu Maha'' "Many islands" or ''Maungahuka'' "Snowy mountains") are an archipelago of New Zealand, lying south of the South Island. The main Auckland Island, occupying , is surrounded by smaller Adams Islan ...

. According to ancient legends, around the year 650 the Polynesian traveller Ui-te-Rangiora

Ui-te-Rangiora or Hui Te Rangiora is a legendary Polynesian navigator from Rarotonga who is claimed to have sailed to the Southern Ocean and sometimes to have discovered Antarctica.

According to a 19th-century interpretation of Rarotongan legen ...

led a fleet of Waka Tīwai south until they reached "a place of bitter cold where rock-like structures rose from a solid sea". It is unclear from the legends how far south Ui-te-Rangiora penetrated, but it appears that he observed ice in large quantities. A shard of undated, unidentified pottery, reported as found in 1886 in the Antipodes Islands

The Antipodes Islands ( Maōri: Moutere Mahue; "Abandoned island") are inhospitable and uninhabited volcanic islands in subantarctic waters to the south of – and territorially part of – New Zealand. The 21 km2 archipelago lies 860 ...

, has been associated with this expedition.

Ferdinand Magellan

Although Portuguese by birth, Ferdinand Magellan transferred his allegiance to

Although Portuguese by birth, Ferdinand Magellan transferred his allegiance to King Charles I of Spain

Charles V, french: Charles Quint, it, Carlo V, nl, Karel V, ca, Carles V, la, Carolus V (24 February 1500 – 21 September 1558) was Holy Roman Emperor and Archduke of Austria from 1519 to 1556, King of Spain ( Castile and Aragon) fro ...

, on whose behalf he left Seville

Seville (; es, Sevilla, ) is the capital and largest city of the Spanish autonomous community of Andalusia and the province of Seville. It is situated on the lower reaches of the River Guadalquivir, in the southwest of the Iberian Penins ...

on 10 August 1519, with a squadron of five ships, in search of a western route to the Spice Islands

A spice is a seed, fruit, root, bark, or other plant substance primarily used for flavoring or coloring food. Spices are distinguished from herbs, which are the leaves, flowers, or stems of plants used for flavoring or as a garnish. Spices are ...

in the East Indies

The East Indies (or simply the Indies), is a term used in historical narratives of the Age of Discovery. The Indies refers to various lands in the East or the Eastern hemisphere, particularly the islands and mainlands found in and around ...

. Success depended on finding a strait or passage through the South America

South America is a continent entirely in the Western Hemisphere and mostly in the Southern Hemisphere, with a relatively small portion in the Northern Hemisphere at the northern tip of the continent. It can also be described as the sou ...

n land masses, or finding the southern tip of the continent and sailing around it. The South American coast was sighted on 6 December 1519, and Magellan moved cautiously southward, following the coast to reach latitude 49°S on 31 March 1520. Little if anything was known of the coast south of this point, so Magellan decided to wait out the southern winter here, and established the settlement of Puerto San Julian

Puerto, a Spanish word meaning ''seaport'', may refer to:

Places

*El Puerto de Santa María, Andalusia, Spain

*Puerto, a seaport town in Cagayan de Oro City, Philippines

*Puerto Colombia, Colombia

*Puerto Cumarebo, Venezuela

*Puerto Galera, Orient ...

.

In September 1520, the voyage continued down the uncharted coast, and on 21 October reached 52°S. Here Magellan found a deep inlet which proved to be the strait he was seeking, later to be known by his name. Early in November 1520, as the squadron navigated through the strait, they reached its most southerly point at approximate latitude 54°S. This was a record Farthest South for a European navigator, though not the farthest southern penetration by man; the position was north of the Tierra del Fuego

Tierra del Fuego (, ; Spanish for "Land of the Fire", rarely also Fireland in English) is an archipelago off the southernmost tip of the South American mainland, across the Strait of Magellan. The archipelago consists of the main island, Isla ...

archipelago, where there is evidence of human settlement dating back thousands of years.

Francisco de Hoces

The first sighting of an ocean passage to the Pacific south of Tierra del Fuego is sometimes attributed to Francisco de Hoces of the Loaisa Expedition. In January 1526 his ship ''San Lesmes'' was blown south from the Atlantic entrance of the Magellan Strait to a point where the crew thought they saw a headland, and water beyond it, which indicated the southern extremity of the continent. There is speculation as to which headland they saw; conceivably it wasCape Horn

Cape Horn ( es, Cabo de Hornos, ) is the southernmost headland of the Tierra del Fuego archipelago of southern Chile, and is located on the small Hornos Island. Although not the most southerly point of South America (which are the Diego Ramí ...

. In parts of the Spanish-speaking world it is believed that de Hoces may have discovered the strait later known as the Drake Passage

The Drake Passage (referred to as Mar de Hoces Hoces Sea"in Spanish-speaking countries) is the body of water between South America's Cape Horn, Chile and the South Shetland Islands of Antarctica. It connects the southwestern part of the Atla ...

more than 50 years before Sir Francis Drake, the British privateer

A privateer is a private person or ship that engages in maritime warfare under a commission of war. Since robbery under arms was a common aspect of seaborne trade, until the early 19th century all merchant ships carried arms. A sovereign or deleg ...

. (in Spanish)

Sir Francis Drake

Sir Francis Drake sailed from Plymouth on 15 November 1577, in command of a fleet of five ships under his flagship ''Pelican'', later renamed the ''Golden Hinde''. His principal objective was plunder, not exploration; his initial targets were the unfortified Spanish towns on the Pacific coasts of Chile and Peru. Following Magellan's route, Drake reached Puerto San Julian on 20 June. After nearly two months in harbour, Drake left the port with a reduced fleet of three ships and a small

Sir Francis Drake sailed from Plymouth on 15 November 1577, in command of a fleet of five ships under his flagship ''Pelican'', later renamed the ''Golden Hinde''. His principal objective was plunder, not exploration; his initial targets were the unfortified Spanish towns on the Pacific coasts of Chile and Peru. Following Magellan's route, Drake reached Puerto San Julian on 20 June. After nearly two months in harbour, Drake left the port with a reduced fleet of three ships and a small pinnace

Pinnace may refer to:

* Pinnace (ship's boat), a small vessel used as a tender to larger vessels among other things

* Full-rigged pinnace

The full-rigged pinnace was the larger of two types of vessel called a pinnace in use from the sixteenth ...

. His ships entered the Magellan Strait on 23 August and emerged in the Pacific Ocean on 6 September.Knox-Johnston, pp. 40–45

Drake set a course to the north-west, but on the following day a gale scattered the ships. The ''Marigold'' was sunk by a giant wave; the ''Elizabeth'' managed to return into the Magellan Strait, later sailing eastwards back to England; the pinnace was lost later. The gales persisted for more than seven weeks. The ''Golden Hinde'' was driven far to the west and south, before clawing its way back towards land. On 22 October, the ship anchored off an island which Drake named "Elizabeth Island Elizabeth Island may refer to:

* Elizabeth Island (Alaska)

* Elizabeth Island, Bahamas

* Elizabeth Island, Bermuda

* Elizabeth Island (Georgian Bay)

* Elizabeth Island, Michigan

* Elizabeth Island, New Zealand

* Elizabeth Island (Victoria)

* ...

", where wood for the galley fires was collected and seals and penguins captured for food.

According to Drake's Portuguese pilot, Nuno da Silva, their position at the anchorage was 57°S. However, there is no island at that latitude. The as yet undiscovered Diego Ramírez Islands

The Diego Ramírez Islands ( es, Islas Diego Ramírez) are a small group of subantarctic islands located in the southernmost extreme of Chile.

History

The islands were first sighted on 12 February 1619 by the Spanish Garcia de Nodal expedition, ...

, at 56°30'S, are treeless and cannot have been the islands where Drake's crew collected wood. This indicates that the navigational calculation was faulty, and that Drake landed at or near the then unnamed Cape Horn

Cape Horn ( es, Cabo de Hornos, ) is the southernmost headland of the Tierra del Fuego archipelago of southern Chile, and is located on the small Hornos Island. Although not the most southerly point of South America (which are the Diego Ramí ...

, possibly on Horn Island itself. His final southern latitude can only be speculated as that of Cape Horn, at 55°59'S. In his report, Drake wrote: "The Uttermost Cape or headland of all these islands stands near 56 degrees, without which there is no main island to be seen to the southwards but that the Atlantic Ocean and the South Sea meet." This open sea south of Cape Horn became known as the Drake Passage even though Drake himself did not traverse it.

Willem Schouten

On 14 June 1615, Willem Schouten, with two ships ''Eendracht'' and ''Hoorn'', set sail fromTexel

Texel (; Texels dialect: ) is a municipality and an island with a population of 13,643 in North Holland, Netherlands. It is the largest and most populated island of the West Frisian Islands in the Wadden Sea. The island is situated north of Den ...

in the Netherlands

)

, anthem = ( en, "William of Nassau")

, image_map =

, map_caption =

, subdivision_type = Sovereign state

, subdivision_name = Kingdom of the Netherlands

, established_title = Before independence

, established_date = Spanish Netherl ...

in search of a western route to the Pacific. ''Hoorn'' was lost in a fire, but ''Eendracht'' continued southward. On 29 January 1616, Schouten reached what he discerned to be the southernmost cape of the South American continent; he named this point ''Kaap Hoorn'' (Cape Horn) after his hometown and his lost ship. Schouten's navigational readings are inaccurate—he placed Cape Horn at 57°48' south, when its actual position is 55°58'. His claim to have reached 58° south is unverified, although he sailed on westward to become the first European navigator to reach the Pacific via the Drake Passage.Knox-Johnston, pp. 57–59

Garcia de Nodal expedition

The next recorded navigation of the Drake Passage was achieved in February 1619, by the brothers Bartolome and Gonzalo Garcia de Nodal. The Garcia de Nodal expedition discovered a small group of islands about south-west of Cape Horn, at latitude 56°30'S. They named these the Diego Ramirez Islands after the expedition's pilot. The islands remained the most southerly known land on earth until Captain James Cook's discovery of theSouth Sandwich Islands

)

, anthem = "God Save the King"

, song_type =

, song =

, image_map = South Georgia and the South Sandwich Islands in United Kingdom.svg

, map_caption = Location of South Georgia and the South Sandwich Islands in the southern Atlantic Oce ...

in 1775.Knox-Johnston, pp. 60–61

Other discoveries

Other voyages brought further discoveries in the southern oceans; in August 1592, the English seaman John Davis had taken shelter "among certain Isles never before discovered"—presumed to be theFalkland Islands

The Falkland Islands (; es, Islas Malvinas, link=no ) is an archipelago in the South Atlantic Ocean on the Patagonian Shelf. The principal islands are about east of South America's southern Patagonian coast and about from Cape Dubouze ...

.Knox-Johnston, p. 52 In 1675, the English merchant voyager Anthony de la Roché

Anthony de la Roché (spelled also ''Antoine de la Roché'', ''Antonio de la Roché'' or ''Antonio de la Roca'' in some sources) was a 17th-century English merchant born in London to a French Huguenot father and an English mother. During a c ...

visited South Georgia

South Georgia ( es, Isla San Pedro) is an island in the South Atlantic Ocean that is part of the British Overseas Territory of South Georgia and the South Sandwich Islands. It lies around east of the Falkland Islands. Stretching in the east� ...

(the first Antarctic

The Antarctic ( or , American English also or ; commonly ) is a polar region around Earth's South Pole, opposite the Arctic region around the North Pole. The Antarctic comprises the continent of Antarctica, the Kerguelen Plateau and othe ...

land discovered); in 1739 the Frenchman Jean-Baptiste Bouvet de Lozier discovered the remote Bouvet Island

Bouvet Island ( ; or ''Bouvetøyen'') is an island claimed by Norway, and declared an uninhabited protected nature reserve. It is a subantarctic volcanic island, situated in the South Atlantic Ocean at the southern end of the Mid-Atlantic R ...

, and in 1772 his compatriot, Yves-Joseph de Kerguelen de Trémarec, found the Kerguelen Islands

The Kerguelen Islands ( or ; in French commonly ' but officially ', ), also known as the Desolation Islands (' in French), are a group of islands in the sub-Antarctic constituting one of the two exposed parts of the Kerguelen Plateau, a lar ...

.

Early Antarctic explorers

Captain James Cook

The second of

The second of James Cook

James Cook (7 November 1728 Old Style date: 27 October – 14 February 1779) was a British explorer, navigator, cartographer, and captain in the British Royal Navy, famous for his three voyages between 1768 and 1779 in the Pacific Ocean and ...

's historic voyages, 1772–1775, was primarily a search for the elusive Terra Australis Incognita that was still believed to lie somewhere in the unexplored latitudes below 40°S. Cook left England in September 1772 with two ships, HMS ''Resolution'' and HMS ''Adventure''. After pausing at Cape Town, on 22 November the two ships sailed due south, but were driven to the east by heavy gales.Coleman, pp. 56–57 They managed to edge further south, encountering their first pack ice

Drift ice, also called brash ice, is sea ice that is not attached to the shoreline or any other fixed object (shoals, grounded icebergs, etc.).Leppäranta, M. 2011. The Drift of Sea Ice. Berlin: Springer-Verlag. Unlike fast ice, which is "faste ...

on 10 December. This soon became a solid barrier, which tested Cook's seamanship as he manoeuvered for a passage through. Eventually, he found open water, and was able to continue south; on 17 January 1773, the expedition reached the Antarctic Circle at 66°20'S,Coleman, p. 59 the first ships to do so. Further progress was barred by ice, and the ships turned north-eastwards and headed for New Zealand, which they reached on 26 March.

During the ensuing months, the expedition explored the southern Pacific Ocean before Cook took ''Resolution'' south again—''Adventure'' had retired back to South Africa after a confrontation with the New Zealand native population. This time Cook was able to penetrate deep beyond the Antarctic Circle, and on 30 January 1774 reached 71°10'S, his Farthest South,Preston, p. 11 but the state of the ice made further southward travel impossible. This southern record would hold for 49 years.

In the course of his voyages in Antarctic waters, Cook had encircled the world at latitudes generally above 60°S, and saw nothing but bleak inhospitable islands, without a hint of the fertile continent which some still hoped lay in the south. Cook wrote that if any such continent existed it would be "a country doomed by nature", and that "no man will venture further than I have done, and the land to the South will never be explored". He concluded: "Should the impossible be achieved and the land attained, it would be wholly useless and of no benefit to the discoverer or his nation".

Searching for land

Despite Cook's prediction, the early 19th century saw numerous attempts to penetrate southward, and to discover new lands. In 1819, William Smith, in command of thebrigantine

A brigantine is a two-masted sailing vessel with a fully square-rigged foremast and at least two sails on the main mast: a square topsail and a gaff sail mainsail (behind the mast). The main mast is the second and taller of the two masts.

Ol ...

''Williams'', discovered the South Shetland Islands

The South Shetland Islands are a group of Antarctic islands with a total area of . They lie about north of the Antarctic Peninsula, and between southwest of the nearest point of the South Orkney Islands. By the Antarctic Treaty of 1 ...

,Knox-Johnston, pp. 85–86 and in the following year Edward Bransfield

Edward Bransfield (c. 1785 – 31 October 1852) was an Irish sailor who became an officer in the British Royal Navy, serving as a master on several ships, after being impressed into service in Ireland at the age of 18. He is noted for his par ...

, in the same ship, sighted the Trinity Peninsula at the northern extremity of Graham Land

Graham Land is the portion of the Antarctic Peninsula that lies north of a line joining Cape Jeremy and Cape Agassiz. This description of Graham Land is consistent with the 1964 agreement between the British Antarctic Place-names Committee an ...

. A few days before Bransfield's discovery, on 27 January 1820, the Russian captain Fabian von Bellingshausen

Fabian Gottlieb Thaddeus von Bellingshausen (russian: Фадде́й Фадде́евич Беллинсга́узен, translit=Faddéy Faddéevich Bellinsgáuzen; – ) was a Russian naval officer, cartographer and explorer, who ultimately ...

, in another Antarctic sector, had come within sight of the coast of what is now known as Queen Maud Land

Queen Maud Land ( no, Dronning Maud Land) is a roughly region of Antarctica claimed by Norway as a dependent territory. It borders the claimed British Antarctic Territory 20° west and the Australian Antarctic Territory 45° east. In addi ...

. He is thus credited as the first person to see the continent's mainland, although he did not make this claim himself. Bellingshausen made two circumnavigations mainly in latitudes between 60 and 67°S, and in January 1821 reached his most southerly point at 70°S, in a longitude close to that in which Cook had made his record 47 years earlier. In 1821 the American sealing captain John Davis led a party which landed on an uncharted stretch of land beyond the South Shetlands. "I think this Southern Land to be a Continent", he wrote in his ship's log. If his landing was not on an island, his party were the first to set foot on the Antarctic continent.Barczewski, p. 19

James Weddell

James Weddell was anAnglo-Scottish

Anglo is a prefix indicating a relation to, or descent from, the Angles, England, English culture, the English people or the English language, such as in the term ''Anglosphere''. It is often used alone, somewhat loosely, to refer to people ...

seaman who saw service in both the Royal Navy

The Royal Navy (RN) is the United Kingdom's naval warfare force. Although warships were used by English and Scottish kings from the early medieval period, the first major maritime engagements were fought in the Hundred Years' War against Fr ...

and the merchant marine before undertaking his first voyages to Antarctic waters. In 1819, in command of the 160-ton brigantine

A brigantine is a two-masted sailing vessel with a fully square-rigged foremast and at least two sails on the main mast: a square topsail and a gaff sail mainsail (behind the mast). The main mast is the second and taller of the two masts.

Ol ...

which had been adapted for whaling, he set sail for the newly discovered whaling grounds of the South Sandwich Islands. His chief interest on this voyage was in finding the "Aurora Islands

The Aurora Islands was a group of three phantom islands first reported in 1762 by the Spanish merchant ship ''Aurora'' while sailing from Lima to Cadiz. The Aurora's officers reported sighting them again in 1774. The Spanish ship ''San Miguel'' ...

", which had been reported at 53°S, 48°W by the Spanish ship ''Aurora'' in 1762. He failed to discover this non-existent land, but his sealing activities showed a handsome profit.

In 1822 Weddell, again in command of ''Jane'' and this time accompanied by a smaller ship, the cutter ''Beaufoy'', set sail for the south with instructions from his employers that, should the sealing prove barren, he was to "investigate beyond the track of former navigators". This suited Weddell's exploring instincts, and he equipped his vessel with chronometers, thermometers, compasses, barometers and charts. In January 1823 he probed the waters between the South Sandwich Islands and the South Orkney Islands, looking for new land. Finding none, he turned southward down the 40°W meridian, deep into the sea that now bears his name. The season was unusually calm, and Weddell reported that "not a particle of ice of any description was to be seen". On 20 February 1823, he reached a new Farthest South of 74°15'S, three degrees beyond Cook's former record. Unaware that he was close to land, Weddell decided to return northward from this point, convinced that the sea continued as far as the South Pole.

Another two days' sailing would likely have brought him within sight of

In 1822 Weddell, again in command of ''Jane'' and this time accompanied by a smaller ship, the cutter ''Beaufoy'', set sail for the south with instructions from his employers that, should the sealing prove barren, he was to "investigate beyond the track of former navigators". This suited Weddell's exploring instincts, and he equipped his vessel with chronometers, thermometers, compasses, barometers and charts. In January 1823 he probed the waters between the South Sandwich Islands and the South Orkney Islands, looking for new land. Finding none, he turned southward down the 40°W meridian, deep into the sea that now bears his name. The season was unusually calm, and Weddell reported that "not a particle of ice of any description was to be seen". On 20 February 1823, he reached a new Farthest South of 74°15'S, three degrees beyond Cook's former record. Unaware that he was close to land, Weddell decided to return northward from this point, convinced that the sea continued as far as the South Pole.

Another two days' sailing would likely have brought him within sight of Coats Land

Coats Land is a region in Antarctica which lies westward of Queen Maud Land and forms the eastern shore of the Weddell Sea, extending in a general northeast–southwest direction between 20°00′W and 36°00′W. The northeast part was discov ...

, which was not discovered until 1904, by William Speirs Bruce

William Speirs Bruce (1 August 1867 – 28 October 1921) was a British naturalist, polar scientist and oceanographer who organized and led the Scottish National Antarctic Expedition (SNAE, 1902–04) to the South Orkney Islands and the Wedd ...

during the Scottish National Antarctic Expedition

The Scottish National Antarctic Expedition (SNAE), 1902–1904, was organised and led by William Speirs Bruce, a natural scientist and former medical student from the University of Edinburgh. Although overshadowed in terms of prestige by R ...

, 1902–1904. On his return to England, Weddell's claim to have exceeded Cook's record by such a margin "caused some raised eyebrows", but was soon accepted.

Benjamin Morrell

In November 1823, the American sealing captain Benjamin Morrell reached the South Sandwich Islands in the schooner ''Wasp''. According to his own later account he then sailed south, unconsciously following the track taken by James Weddell a month previously. Morrell claimed to have reached 70°14'S, at which point he turned north because the ship's stoves were running short of fuel—otherwise, he says, he could have "reached 85° without the least doubt". After turning, he claimed to have encountered land which he described in some detail, and which he named New South Greenland. This land proved not to exist. Morrell's reputation as a liar and a fraud means that most of his geographical claims have been dismissed by scholars, although attempts have been made to rationalise his assertions.James Clark Ross

James Clark Ross's 1839–1843 Antarctic expedition in HMS ''Erebus'' and HMS ''Terror'' was a full-scale Royal Naval enterprise, the principal function of which was to test current theories onmagnetism

Magnetism is the class of physical attributes that are mediated by a magnetic field, which refers to the capacity to induce attractive and repulsive phenomena in other entities. Electric currents and the magnetic moments of elementary particles ...

, and to try to locate the South Magnetic Pole. The expedition had first been proposed by leading astronomer Sir John Herschel

Sir John Frederick William Herschel, 1st Baronet (; 7 March 1792 – 11 May 1871) was an English polymath active as a mathematician, astronomer, chemist, inventor, experimental photographer who invented the blueprint and did botanical wor ...

, and was supported by the Royal Society

The Royal Society, formally The Royal Society of London for Improving Natural Knowledge, is a learned society and the United Kingdom's national academy of sciences. The society fulfils a number of roles: promoting science and its benefits, re ...

and the British Association for the Advancement of Science

The British Science Association (BSA) is a charity and learned society founded in 1831 to aid in the promotion and development of science. Until 2009 it was known as the British Association for the Advancement of Science (BA). The current Chi ...

.Coleman, pp. 326–328 Ross had considerable past experience in magnetic observation and Arctic exploration; in May 1831 he had been a member of a party that had reached the location of the North Magnetic Pole

The north magnetic pole, also known as the magnetic north pole, is a point on the surface of Earth's Northern Hemisphere at which the planet's magnetic field points vertically downward (in other words, if a magnetic compass needle is allowed t ...

, and he was an obvious choice as commander.

The expedition left England on 30 September 1839, and after a voyage that was slowed by the many stops required to carry out work on magnetism, it reached

The expedition left England on 30 September 1839, and after a voyage that was slowed by the many stops required to carry out work on magnetism, it reached Tasmania

)

, nickname =

, image_map = Tasmania in Australia.svg

, map_caption = Location of Tasmania in AustraliaCoordinates:

, subdivision_type = Country

, subdi ...

in August 1840. Following a three-month break imposed by the southern winter, they sailed south-east on 12 November 1840, and crossed the Antarctic Circle

The Antarctic Circle is the most southerly of the five major circles of latitude that mark maps of Earth. The region south of this circle is known as the Antarctic, and the zone immediately to the north is called the Southern Temperate Zone. So ...

on 1 January 1841. On 11 January a long mountainous coastline that stretched to the south was sighted. Ross named the land Victoria Land

Victoria Land is a region in eastern Antarctica which fronts the western side of the Ross Sea and the Ross Ice Shelf, extending southward from about 70°30'S to 78°00'S, and westward from the Ross Sea to the edge of the Antarctic Plateau. I ...

, and the mountains the Admiralty Range. He followed the coast southwards and passed Weddell's Farthest South point of 74°15'S on 23 January. A few days later, as they moved further eastward to avoid shore ice, they were met by the sight of twin volcanoes (one of them active), which were named Mount Erebus

Mount Erebus () is the second-highest volcano in Antarctica (after Mount Sidley), the highest active volcano in Antarctica, and the southernmost active volcano on Earth. It is the sixth-highest ultra mountain on the continent.

With a sum ...

and Mount Terror, in honour of the expedition's ships.Coleman, pp. 329–332

The Great Ice Barrier

The Ross Ice Shelf is the largest ice shelf of Antarctica (, an area of roughly and about across: about the size of France). It is several hundred metres thick. The nearly vertical ice front to the open sea is more than long, and between hi ...

(later to be called the "Ross Ice Shelf") stretched away east of these mountains, forming an impassable obstacle to further southward progress. In his search for a strait or inlet, Ross explored along the edge of the barrier, and reached an approximate latitude of 78°S on or about 8 February 1841. He failed to find a suitable anchorage that would have allowed the ships to over-winter, so he returned to Tasmania, arriving there in April 1841.

The following season Ross returned and located an inlet in the Barrier face that enabled him, on 23 February 1842, to extend his Farthest South to 78°09'30"S,Coleman, p. 335 a record which would remain unchallenged for 58 years. Although Ross had not been able to land on the Antarctic continent, nor approach the location of the South Magnetic Pole, on his return to England in 1843 he was knighted

A knight is a person granted an honorary title of knighthood by a head of state (including the Pope) or representative for service to the monarch, the church or the country, especially in a military capacity. Knighthood finds origins in the G ...

for his achievements in geographical and scientific exploration.

Explorers of the Heroic Age

The oceanographic research voyage known as theChallenger Expedition

The ''Challenger'' expedition of 1872–1876 was a scientific program that made many discoveries to lay the foundation of oceanography. The expedition was named after the naval vessel that undertook the trip, .

The expedition, initiated by Wi ...

, 1872–1876, explored Antarctic waters for several weeks, but did not approach the land itself; its research, however, proved the existence of an Antarctic continent beyond a reasonable doubt.

The impetus for what would become known as the Heroic Age of Antarctic Exploration

The Heroic Age of Antarctic Exploration was an era in the exploration of the continent of Antarctica which began at the end of the 19th century, and ended after the First World War; the Shackleton–Rowett Expedition of 1921–1922 is often ci ...

came in 1895, when in an address to the Sixth International Geographical Congress in London, Professor Sir John Murray called for a resumption of Antarctic exploration: "a steady, continuous, laborious and systematic exploration of the whole southern region". He followed this call with an appeal to British patriotism: "Is the last great piece of maritime exploration on the surface of our Earth to be undertaken by Britons, or is it to be left to those who may be destined to succeed or supplant us on the Ocean?" During the following quarter-century, fifteen expeditions from eight different nations rose to this challenge. In the patriotic spirit engendered by Murray's call, and under the influence of RGS president Sir Clements Markham, British endeavours in the following years gave particular weight to the achievement of new Farthest South records, and began to develop the character of a race for the South Pole.

Carsten Borchgrevink

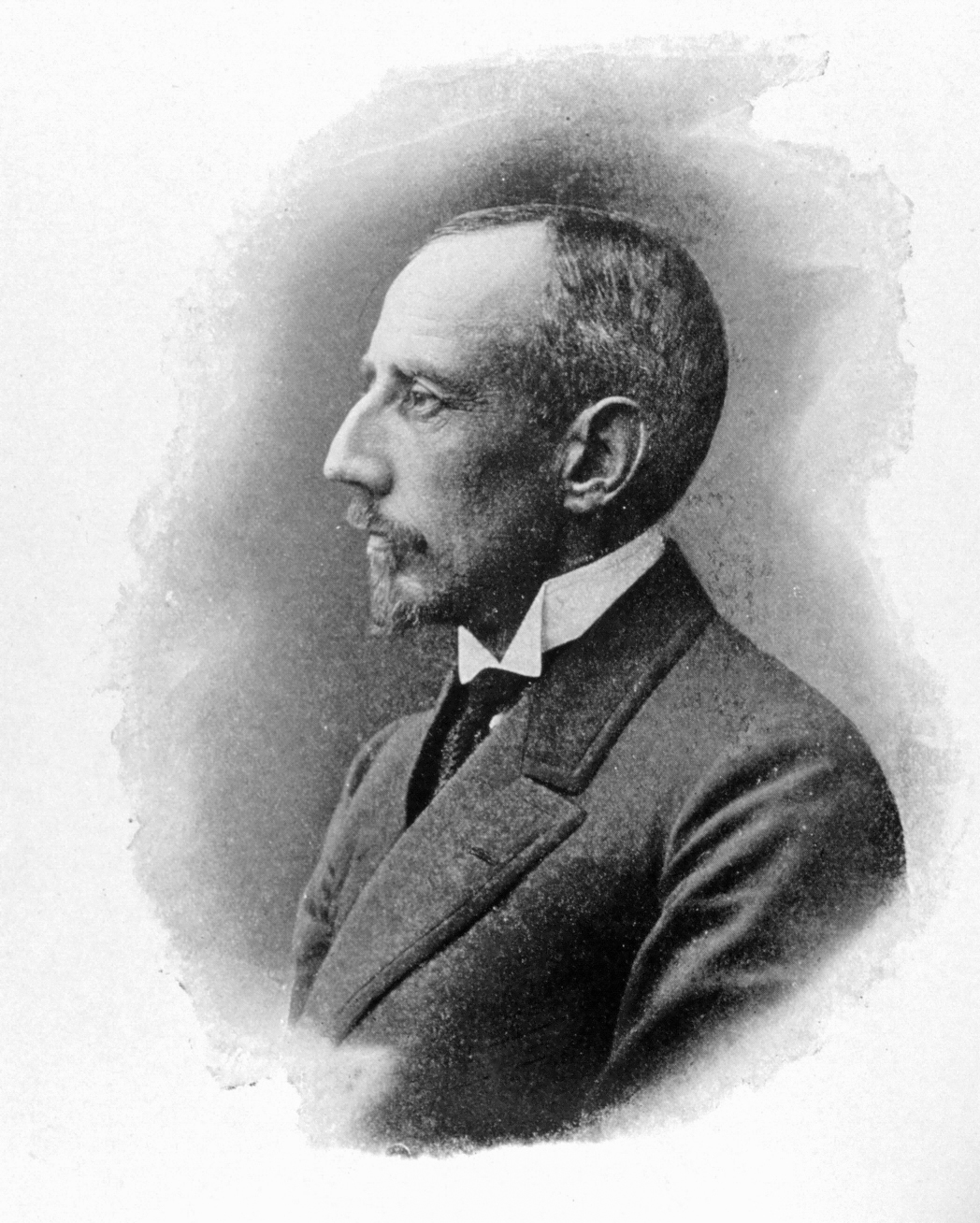

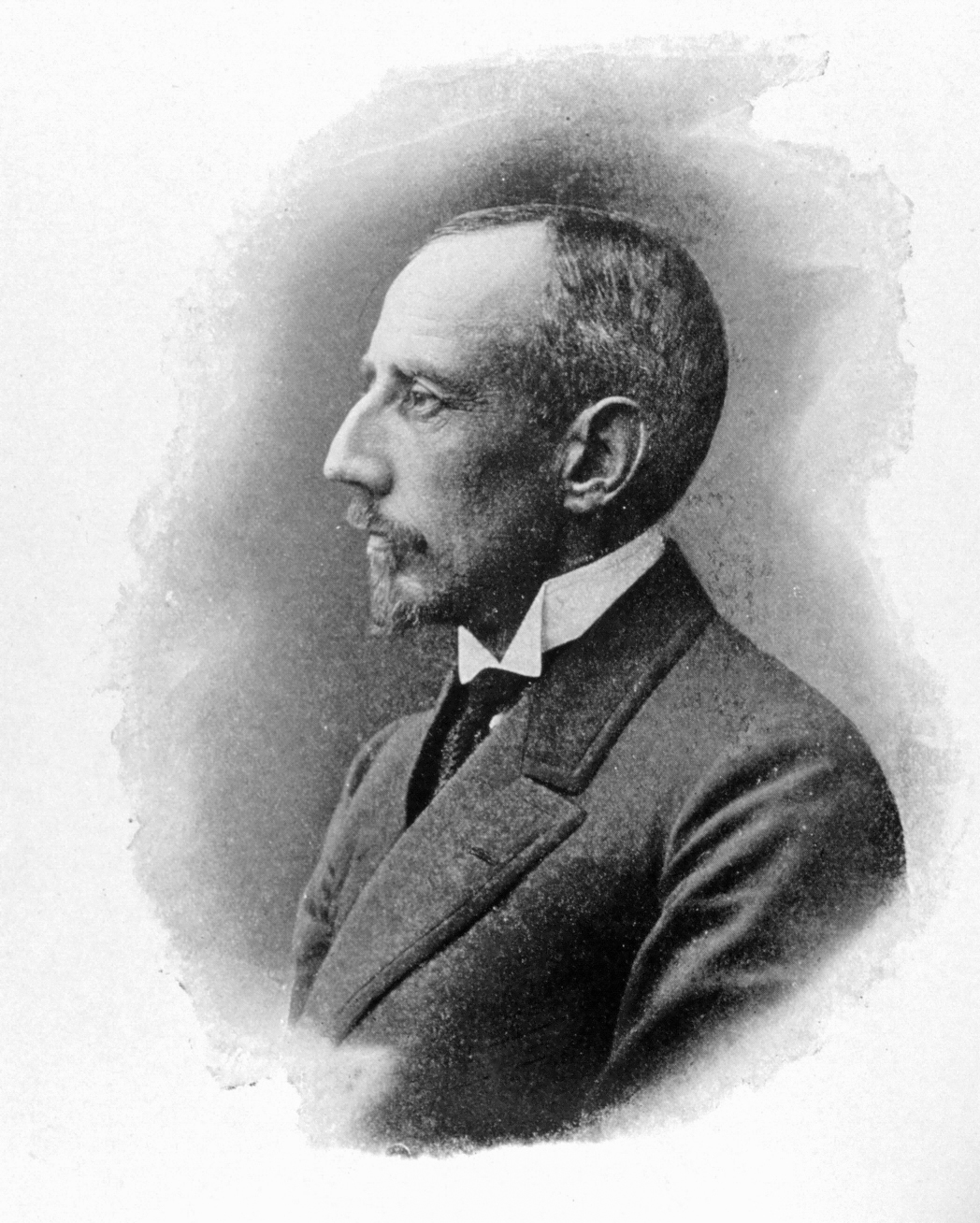

The Norwegian-born

The Norwegian-born Carsten Egeberg Borchgrevink

Carsten Egeberg Borchgrevink (1 December 186421 April 1934) was an Anglo-Norwegian polar explorer and a pioneer of Antarctic travel. He inspired Sir Robert Falcon Scott, Sir Ernest Shackleton, Roald Amundsen, and others associated with the Her ...

had emigrated to Australia in 1888, where he worked on survey teams in Queensland and New South Wales before accepting a school teaching post. In 1894 he joined a sealing and whaling expedition to the Antarctic, led by Henryk Bull

Henrik Johan Bull (13 October 18441 June 1930) was a Norwegian businessman and whaler. Henry Bull was one of the pioneers in the exploration of Antarctica.

Biography

Henrik Johan Bull was born at Stokke in Vestfold County, Norway. He attended sc ...

. In January 1895 Borchgrevink was one of a group from that expedition that claimed the first confirmed landing on the Antarctic continent, at Cape Adare

Cape Adare is a prominent cape of black basalt forming the northern tip of the Adare Peninsula and the north-easternmost extremity of Victoria Land, East Antarctica.

Description

Marking the north end of Borchgrevink Coast and the west ...

. Borchgrevink determined to return with his own expedition, which would overwinter and explore inland, with the location of the South Magnetic Pole as an objective.

Borchgrevink went to England, where he was able to persuade the publishing magnate Sir George Newnes to finance him to the extent of £40,000, equivalent to £ in , with the sole stipulation that, despite the shortage of British participants, the venture be styled the "British Antarctic Expedition".Preston, p. 4 This was by no means the grand British expedition envisaged by Markham and the geographical establishment, who were hostile and dismissive of Borchgrevink. On 23 August 1898 the expedition ship ''Southern Cross'' left London for the Ross Sea

The Ross Sea is a deep bay of the Southern Ocean in Antarctica, between Victoria Land and Marie Byrd Land and within the Ross Embayment, and is the southernmost sea on Earth. It derives its name from the British explorer James Clark Ross who ...

, reaching Cape Adare on 17 February 1899. Here a shore party was landed and was the first to over-winter on the Antarctic mainland, in a prefabricated hut.

In January 1900, ''Southern Cross'' returned, picked up the shore party and, following the route which Ross had taken 60 years previously, sailed southward to the Great Ice Barrier, which they discovered had retreated some south since the days of Ross. A party consisting of Borchgrevink, William Colbeck and a Sami

Acronyms

* SAMI, ''Synchronized Accessible Media Interchange'', a closed-captioning format developed by Microsoft

* Saudi Arabian Military Industries, a government-owned defence company

* South African Malaria Initiative, a virtual expertise ...

named Per Savio landed with sledges and dogs. This party ascended the Barrier and made the first sledge journey on the barrier surface; on 16 February 1900 they extended the Farthest South record to 78°50'S.Preston, pp. 13–15 On its return to England later in 1900, Borchgrevink's expedition was received without enthusiasm, despite its new southern record. Historian David Crane commented that if Borchgrevink had been a British naval officer, his contribution to Antarctic knowledge might have been better received, but "a Norwegian seaman/schoolmaster was never going to be taken seriously".Crane, p. 74

Robert Falcon Scott

The Discovery Expedition of 1901–1904 wasRobert Falcon Scott

Captain Robert Falcon Scott, , (6 June 1868 – c. 29 March 1912) was a British Royal Navy officer and explorer who led two expeditions to the Antarctic regions: the ''Discovery'' expedition of 1901–1904 and the ill-fated ''Terra Nov ...

's first Antarctic command. Although according to Edward Wilson Edward Wilson may refer to:

*Ed Wilson (artist) (1925–1996), African American sculptor

* Ed Wilson (baseball) (1875–?), American baseball player

* Ed Wilson (singer) (1945–2010), Brazilian singer-songwriter

* Ed Wilson, American television ex ...

the intention was to "reach the Pole if possible, or find some new land", there is nothing in Scott's writings, nor in the official objectives of the expedition, to indicate that the pole was a definite goal. However, a southern journey towards the pole was within Scott's formal remit to "explore the ice barrier of Sir James Ross ... and to endeavour to solve the very important physical and geographical questions connected with this remarkable ice formation".

The southern journey was undertaken by Scott, Wilson and Ernest Shackleton

Sir Ernest Henry Shackleton (15 February 1874 – 5 January 1922) was an Anglo-Irish Antarctic explorer who led three British expeditions to the Antarctic. He was one of the principal figures of the period known as the Heroic Age o ...

. The party set out on 1 November 1902 with various teams in support, and one of these, led by Michael Barne

Michael Barne (15 October 1877 – 31 May 1961) was an officer of the 1901-04 Discovery Expedition and was the last survivor of the expedition.

Early life

Barne was born at Sotterley Park, Suffolk, the son of Frederick Barne and his wife, La ...

, passed Borchgrevink's Farthest South mark on 11 November, an event recorded with great high spirits in Wilson's diary. The march continued, initially in favourable weather conditions, but encountered increasing difficulties caused by the party's lack of ice travelling experience and the loss of all its dogs through a combination of poor diet and overwork. The 80°S mark was passed on 2 December, and four weeks later, on 30 December 1902, Wilson and Scott took a short ski trip from their southern camp to set a new Farthest South at (according to their measurements) 82°17'S. Modern maps, correlated with Shackleton's photograph and Wilson's drawing, put their final camp at 82°6'S, and the point reached by Scott and Wilson at 82°11'S, beyond Borchgrevink's mark.Crane, pp. 214–215

Ernest Shackleton

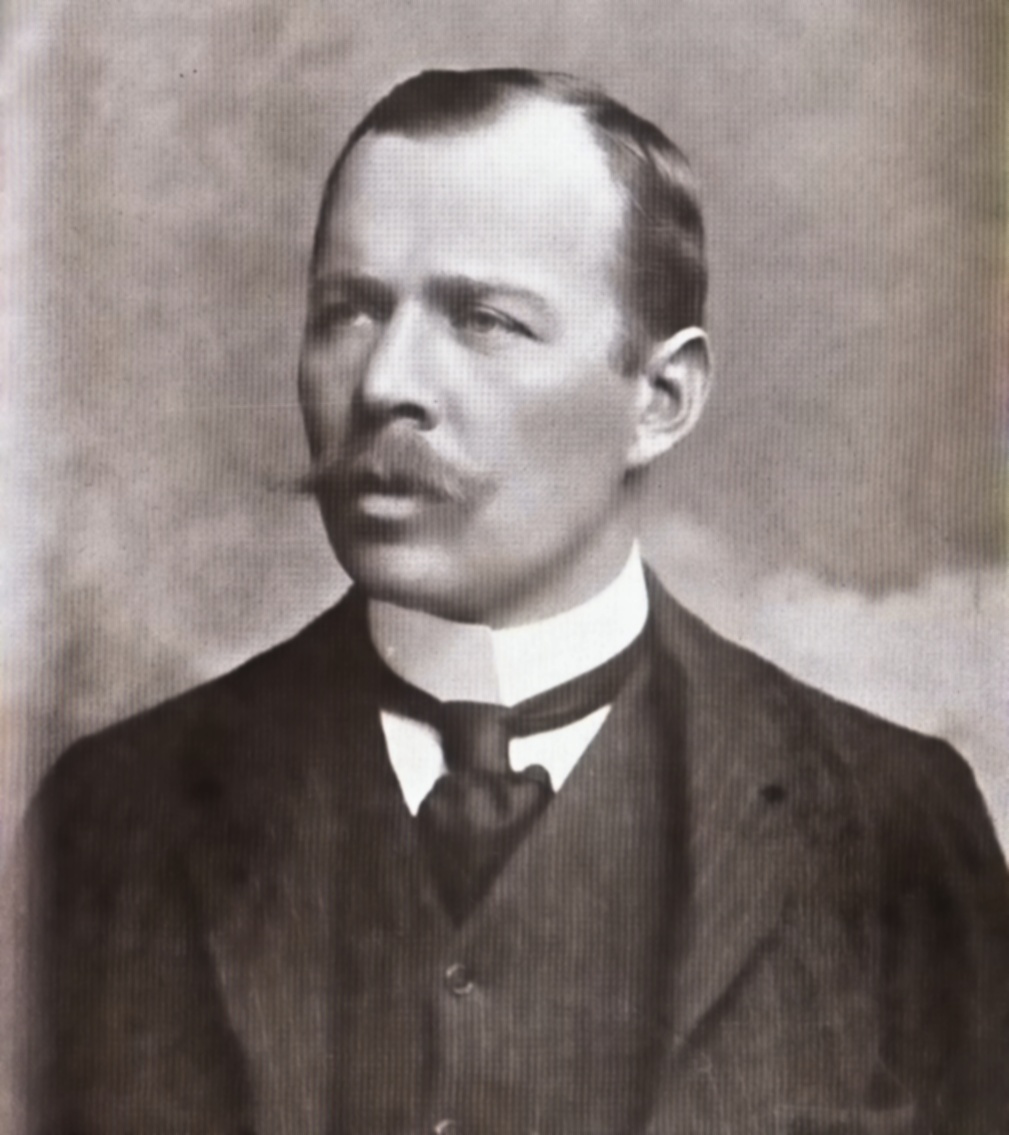

After his share in the Farthest South achievement of the Discovery Expedition,

After his share in the Farthest South achievement of the Discovery Expedition, Ernest Shackleton

Sir Ernest Henry Shackleton (15 February 1874 – 5 January 1922) was an Anglo-Irish Antarctic explorer who led three British expeditions to the Antarctic. He was one of the principal figures of the period known as the Heroic Age o ...

suffered a physical collapse on the return journey, and was sent home with the expedition's relief vessel on orders from Scott; he bitterly resented it, and the two became rivals. Four years later, Shackleton organised his own polar venture, the Nimrod Expedition, 1907–1909. This was the first expedition to set the definite objective of reaching the South Pole, and to have a specific strategy for doing so.Riffenburgh, p. 108

To assist his endeavour, Shackleton adopted a mixed transport strategy, involving the use of Manchurian ponies as pack animals, as well as the more traditional dog-sledges. A specially adapted motor car was also taken. Although the dogs and the car were used during the expedition for a number of purposes, the task of assisting the group that would undertake the march to the pole fell to the ponies. The size of Shackleton's four-man polar party was dictated by the number of surviving ponies; of the ten that were embarked in New Zealand, only four had survived the 1908 winter.

Ernest Shackleton

Sir Ernest Henry Shackleton (15 February 1874 – 5 January 1922) was an Anglo-Irish Antarctic explorer who led three British expeditions to the Antarctic. He was one of the principal figures of the period known as the Heroic Age o ...

and three companions (Frank Wild

John Robert Francis Wild (18 April 1873 – 19 August 1939), known as Frank Wild, was an English sailor and explorer. He participated in five expeditions to Antarctica during the Heroic Age of Antarctic Exploration, for which he was awar ...

, Eric Marshall

Lieutenant Colonel Eric Marshall (29 May 1879 – 26 February 1963) was a British Army doctor and Antarctic explorer with the Nimrod Expedition led by Ernest Shackleton in 1907–09, and was one of the party of four men (Marshall, Shackleton, ...

and Jameson Adams) began their march on 29 October 1908. On 26 November they surpassed the farthest point reached by Scott's 1902 party. "A day to remember", wrote Shackleton in his journal, noting that they had reached this point in far less time than on the previous march with Scott. Shackleton's group continued southward, discovering and ascending the Beardmore Glacier

The Beardmore Glacier in Antarctica is one of the largest valley glaciers in the world, being long and having a width of . It descends about from the Antarctic Plateau to the Ross Ice Shelf and is bordered by the Commonwealth Range of the Que ...

to the polar plateau,Riffenburgh, pp. 227–233 and then marching on to reach their Farthest South point at 88°23'S, a mere from the pole, on 9 January 1909. Here they planted the Union Jack presented to them by Queen Alexandra

Alexandra of Denmark (Alexandra Caroline Marie Charlotte Louise Julia; 1 December 1844 – 20 November 1925) was Queen of the United Kingdom and the British Dominions, and Empress of India, from 22 January 1901 to 6 May 1910 as the wife of ...

, and took possession of the plateau in the name of King Edward VII

Edward VII (Albert Edward; 9 November 1841 – 6 May 1910) was King of the United Kingdom of Great Britain and Ireland and Emperor of India, from 22 January 1901 until his death in 1910.

The second child and eldest son of Queen Victoria an ...

, before shortages of food and supplies forced them to turn back north. This was, at the time, the closest convergence on either pole. The increase of more than six degrees south from Scott's previous record was the greatest extension of Farthest South since Captain Cook's 1773 mark. Shackleton was treated as a hero on his return to England. His record was to stand for less than three years, being passed by Amundsen on 7 December 1911.

Polar conquest

In the wake of Shackleton's near miss, Robert Scott organised the Terra Nova Expedition, 1910–1913, in which securing the South Pole for the

In the wake of Shackleton's near miss, Robert Scott organised the Terra Nova Expedition, 1910–1913, in which securing the South Pole for the British Empire

The British Empire was composed of the dominions, colonies, protectorates, mandates, and other territories ruled or administered by the United Kingdom and its predecessor states. It began with the overseas possessions and trading posts e ...

was an explicitly stated prime objective. As he planned his expedition, Scott saw no reason to believe that his effort would be contested. However, the Norwegian explorer Roald Amundsen

Roald Engelbregt Gravning Amundsen (, ; ; 16 July 1872 – ) was a Norwegian explorer of polar regions. He was a key figure of the period known as the Heroic Age of Antarctic Exploration.

Born in Borge, Østfold, Norway, Amundsen beg ...

, who had been developing plans for a North Pole expedition, changed his mind when, in September 1909, the North Pole was claimed in quick succession by the Americans Frederick Cook

Frederick Albert Cook (June 10, 1865 – August 5, 1940) was an American explorer, physician, and ethnographer who claimed to have reached the North Pole on April 21, 1908. That was nearly a year before Robert Peary, who similarly clai ...

and Robert Peary

Robert Edwin Peary Sr. (; May 6, 1856 – February 20, 1920) was an American explorer and officer in the United States Navy who made several expeditions to the Arctic in the late 19th and early 20th centuries. He is best known for, in Apri ...

. Amundsen resolved to go south instead.

Amundsen concealed his revised intentions until his ship, ''Fram'', was in the Atlantic and beyond communication. Scott was notified by telegram that a rival was in the field, but had little choice other than to continue with his own plans. Meanwhile, ''Fram'' arrived at the Ross Ice Shelf on 11 January 1911, and by 14 January had found the inlet, or "Bay of Whales

The Bay of Whales was a natural ice harbour, or iceport, indenting the front of the Ross Ice Shelf just north of Roosevelt Island, Antarctica. It is the southernmost point of open ocean not only of the Ross Sea, but worldwide. The Ross Sea ex ...

", where Borchgrevink had made his landing eleven years earlier. This became the location of Amundsen's base camp, '' Framheim''.

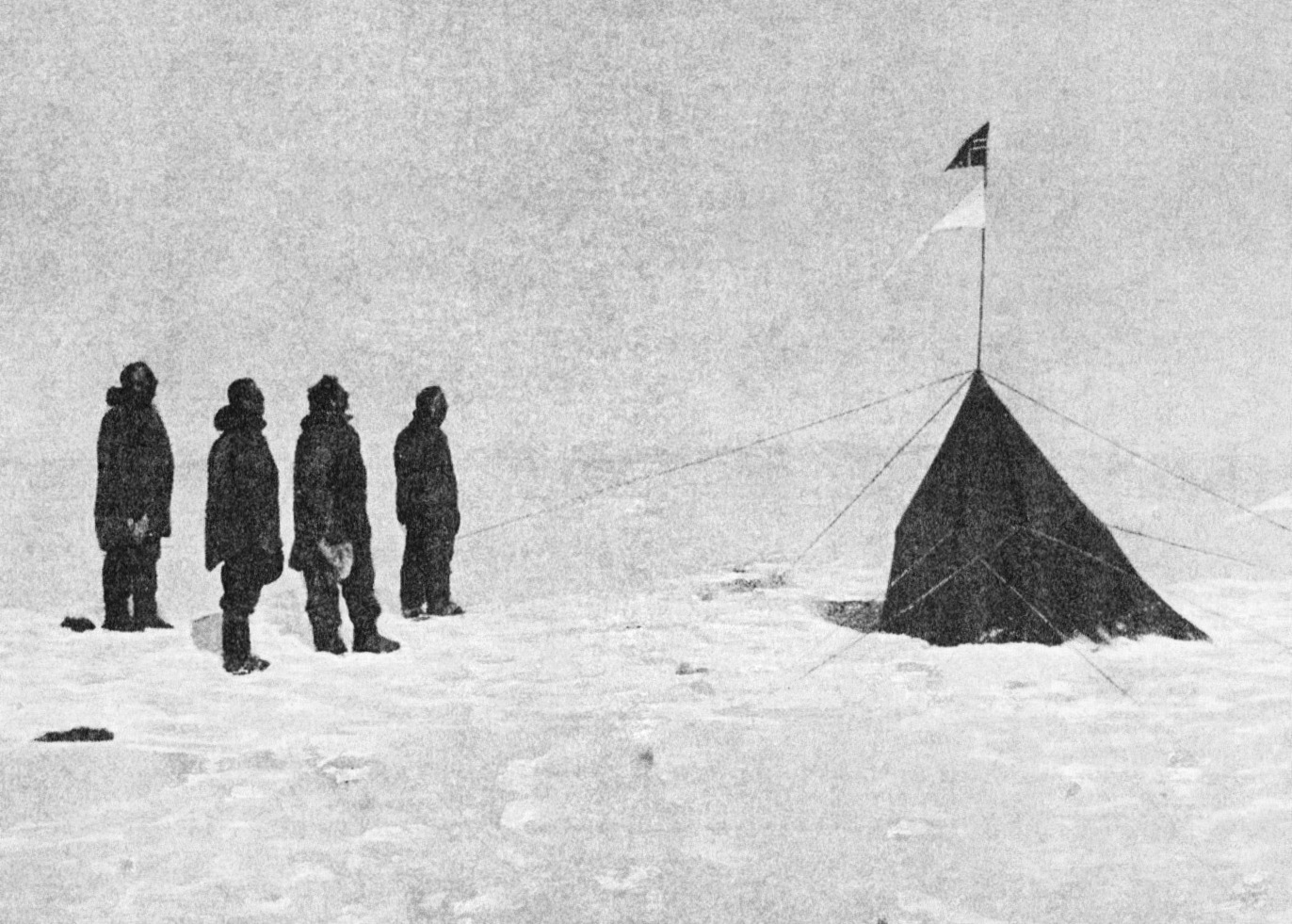

After nine months' preparation, Amundsen's polar journey began on 20 October 1911. Avoiding the known route to the polar plateau via the Beardmore Glacier, Amundsen led his party of five due south, reaching the Transantarctic Mountains

The Transantarctic Mountains (abbreviated TAM) comprise a mountain range of uplifted (primarily sedimentary) rock in Antarctica which extend, with some interruptions, across the continent from Cape Adare in northern Victoria Land to Coats Land. ...

on 16 November. They discovered the Axel Heiberg Glacier

The Axel Heiberg Glacier in Antarctica is a valley glacier, long, descending from the high elevations of the Antarctic Plateau into the Ross Ice Shelf (nearly at sea level) between the Herbert Range and Mount Don Pedro Christophersen in the Q ...

, which provided them with a direct route to the polar plateau and on to the pole. Shackleton's Farthest South mark was passed on 7 December, and the South Pole was reached on 14 December 1911.Amundsen, pp. 120–130 The Norwegian party's greater skills with the techniques of ice travel, using ski and dogs, had proved decisive in their success. Scott's five-man team reached the same point 33 days later, and perished during their return journey. Since Cook's journeys, every expedition that had held the Farthest South record before Amundsen's conquest had been British; however, the final triumph indisputably belonged to the Norwegians.

Later history

After Scott's retreat from the pole in January 1912, the location remained unvisited for nearly 18 years. On 28 November 1929, US Navy

After Scott's retreat from the pole in January 1912, the location remained unvisited for nearly 18 years. On 28 November 1929, US Navy Commander

Commander (commonly abbreviated as Cmdr.) is a common naval officer rank. Commander is also used as a rank or title in other formal organizations, including several police forces. In several countries this naval rank is termed frigate captain. ...

(later Rear-Admiral

Rear admiral is a senior naval flag officer rank, equivalent to a major general and air vice marshal and above that of a commodore and captain, but below that of a vice admiral. It is regarded as a two star "admiral" rank. It is often regarde ...

) Richard E. Byrd and three others completed the first aircraft flight over the South Pole. Twenty-seven years later, Rear-Admiral George J. Dufek became the first person to set foot on the pole since Scott, when on 31 October 1956 he and the crew of R4D-5 Skytrain "Que Sera Sera" landed at the pole. Between November 1956 and February 1957, the first permanent South Pole research station was erected and christened the Amundsen–Scott South Pole Station

The Amundsen–Scott South Pole Station is the United States scientific research station at the South Pole of the Earth. It is the southernmost point under the jurisdiction (not sovereignty) of the United States. The station is located on the ...

in honour of the pioneer explorers. Since then the station had been substantially extended, and in 2008 was housing up to 150 scientific staff and support personnel. Dufek gave considerable assistance to the Commonwealth Trans-Antarctic Expedition

The Commonwealth Trans-Antarctic Expedition (CTAE) of 1955–1958 was a Commonwealth-sponsored expedition that successfully completed the first overland crossing of Antarctica, via the South Pole. It was the first expedition to reach the South ...

, 1955–1958, led by Vivian Fuchs

Sir Vivian Ernest Fuchs ( ; 11 February 1908 – 11 November 1999) was an English scientist-explorer and expedition organizer. He led the Commonwealth Trans-Antarctic Expedition which reached the South Pole overland in 1958.

Biography

Fuc ...

, which on 19 January 1958 became the first party to reach the pole overland since Scott.Fuchs and Hillary, pp. 76, 85–86

Farthest South records

:::::Table of Farthest South records, 1521 to 1911 (letters in "Map key" column relate to adjoining map)See also

*History of Antarctica

The history of Antarctica emerges from early Western theories of a vast continent, known as Terra Australis, believed to exist in the far south of the globe. The term ''Antarctic'', referring to the opposite of the Arctic Circle, was coined by Mar ...

* List of Antarctic expeditions

This list of Antarctic expeditions is a chronological list of expeditions involving Antarctica. Although the existence of a southern continent had been hypothesized as early as the writings of Ptolemy in the 1st century AD, the South Pole was ...

* Heroic Age of Antarctic Exploration

The Heroic Age of Antarctic Exploration was an era in the exploration of the continent of Antarctica which began at the end of the 19th century, and ended after the First World War; the Shackleton–Rowett Expedition of 1921–1922 is often ci ...

* Timeline of women in Antarctica

This is a Timeline of women in Antarctica. This article describes many of the firsts and accomplishments that women from various countries have accomplished in different fields of endeavor on the continent of Antarctica.

650s

650

* Māori exp ...

Notes and references

Notes

Citations

Sources

* * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * *Further reading

* *External links

* * * {{Featured article Heroic Age of Antarctic Exploration Record progressions