Family Compact on:

[Wikipedia]

[Google]

[Amazon]

The Family Compact was a small closed group of men who exercised most of the political, economic and judicial power in

Toronto 1915. These men sought to solidify their personal positions into family dynasties and acquire all the marks of gentility. They used their government positions to extend their business and speculative interests. The origins of the Family Compact lay in overlapping appointments made to the Executive and Legislative Council of Upper Canada. The Councils were intended to operate independently. Section 38 of the Constitutional Act of 1791 referred to the independence of the offices indirectly. While

Grammar schools provided a classical education and were preparation for higher learning and entry into the law or the ministry. Entrance was limited by high tuition fees, even though they were government supported. Common schools for teaching basic education received little support or regulation in comparison at this time. Working class education was trades based through the Master-journeyman-apprentice relationship.

Grammar schools provided a classical education and were preparation for higher learning and entry into the law or the ministry. Entrance was limited by high tuition fees, even though they were government supported. Common schools for teaching basic education received little support or regulation in comparison at this time. Working class education was trades based through the Master-journeyman-apprentice relationship.

The school began teaching in the original Royal Grammar School and for several years the two organizations were essentially unified. On March 15, 1827, a

File:TorontoMossParkEstate.jpg, "Moss Park", 1889, the estate of William Allan

File:The Grange.JPG, The Grange, estate of D'Arcy Boulton Jr.

File:DundurnCastleSummer.JPG, Dundurn Castle, Hamilton, estate of Sir Allen McNab

Canada and the American Revolution: The Disruption of the First British Empire

' (1935) *

* ttps://web.archive.org/web/20110610012755/http://www.archives.gov.on.ca/english/archival-records/interloan/canco.aspx ''Archives of Ontario, Canada Company Fonds.''

''Historical Narratives of Early Canada'' by W.R. Wilson

{{Ontario provincial political parties Political parties in Upper Canada Political history of Ontario

Upper Canada

The Province of Upper Canada (french: link=no, province du Haut-Canada) was a Province, part of The Canadas, British Canada established in 1791 by the Kingdom of Great Britain, to govern the central third of the lands in British North Americ ...

(today’s Ontario

Ontario ( ; ) is one of the thirteen provinces and territories of Canada.Ontario is located in the geographic eastern half of Canada, but it has historically and politically been considered to be part of Central Canada. Located in Central Ca ...

) from the 1810s to the 1840s. It was the Upper Canadian equivalent of the Château Clique in Lower Canada

The Province of Lower Canada (french: province du Bas-Canada) was a British colony on the lower Saint Lawrence River and the shores of the Gulf of Saint Lawrence (1791–1841). It covered the southern portion of the current Province of Quebec ...

. It was noted for its conservatism and opposition to democracy.

The Family Compact emerged from the War of 1812

The War of 1812 (18 June 1812 – 17 February 1815) was fought by the United States of America and its indigenous allies against the United Kingdom and its allies in British North America, with limited participation by Spain in Florida. It be ...

and collapsed in the aftermath of the Rebellions of 1837–1838

The Rebellions of 1837–1838 (french: Les rébellions de 1837), were two armed uprisings that took place in Lower and Upper Canada in 1837 and 1838. Both rebellions were motivated by frustrations with lack of political reform. A key shared g ...

. Its resistance to the political principle of responsible government

Responsible government is a conception of a system of government that embodies the principle of parliamentary accountability, the foundation of the Westminster system of parliamentary democracy. Governments (the equivalent of the executive br ...

contributed to its short life. At the end of its lifespan, the compact would be condemned by Lord Durham

Earl of Durham is a title in the Peerage of the United Kingdom. It was created in 1833 for the Whig politician and colonial official John Lambton, 1st Baron Durham. Known as "Radical Jack", he played a leading role in the passing of the Gre ...

, a leading Whig, who summarised its grip on power: Fortified by family connexion, and the common interest felt by all who held, and all who desired, subordinate offices, that party was thus erected into a solid and permanent power, controlled by no responsibility, subject to no serious change, exercising over the whole government of the Province an authority utterly independent of the people and its representatives, and possessing the only means of influencing either the Government at home, or the colonial representative of the Crown.

Etymology

Thomas Dalton described theruling class

In sociology, the ruling class of a society is the social class who set and decide the political and economic agenda of society. In Marxist philosophy, the ruling class are the capitalist social class who own the means of production and by ex ...

in Kingston, Ontario, as "all one family compacted junto." The term ''Family Compact'' appeared in a letter written by Marshall Spring Bidwell to William Warren Baldwin in 1828. ''Family'' did not mean relations by marriage, but rather a close brotherhood. Lord Durham

Earl of Durham is a title in the Peerage of the United Kingdom. It was created in 1833 for the Whig politician and colonial official John Lambton, 1st Baron Durham. Known as "Radical Jack", he played a leading role in the passing of the Gre ...

noted in 1839 "There is, in truth, very little of family connection among the persons thus united". The phrase was popularised by William Lyon Mackenzie in 1833 in its use to describe the elite in York.

"Gentlemanly capitalism" and British colonialism

The historians P. J. Cain and A. G. Hopkins have emphasized that the British empire at "the mid-nineteenth century represented the extension abroad of the institutions and principles entrenched at home". Upper Canada, created in the very "image and transcript" of the British constitution is but one example. Like that of the United Kingdom, the constitution of Upper Canada was established on the mixed monarchy model. Mixed monarchy is a form of government that integrates elements ofdemocracy

Democracy (From grc, δημοκρατία, dēmokratía, ''dēmos'' 'people' and ''kratos'' 'rule') is a form of government in which the people have the authority to deliberate and decide legislation (" direct democracy"), or to choose g ...

, aristocracy

Aristocracy (, ) is a form of government that places strength in the hands of a small, privileged ruling class, the aristocrats. The term derives from the el, αριστοκρατία (), meaning 'rule of the best'.

At the time of the word' ...

, and monarchy

A monarchy is a form of government in which a person, the monarch, is head of state for life or until abdication. The political legitimacy and authority of the monarch may vary from restricted and largely symbolic ( constitutional monar ...

. Upper Canada, however, had no aristocracy. The methods pursued to create one were similar to that used in Britain itself. The result was the Family Compact.

Cain and Hopkins point out that "new money", the financiers rather than the industrial "barons", were gradually gentrified through the purchase of land, intermarriage and the acquisition of titles. In the United Kingdom, the control exercised by the aristocracy over the House of Commons remained undisturbed before 1832 and was only slowly eroded thereafter, while its dominance of the executive lasted well beyond 1850." Hopkins and Cain refer to this alliance of aristocracy and financiers as " gentlemanly capitalism": "a form of capitalism headed by improving aristocratic landlords in association with improving financiers who served as their junior partners." A similar pattern is seen in other colonial empires, such as the Dutch Empire.

This same process is seen in Upper Canada. The historian J. K. Johnson's analysis of the Upper Canadian elite between 1837 and 1840 measured influence according to overlapping leadership roles on the boards of the main social, political and economic institutions. For example, William Allan, one of the most powerful, "was an executive councillor, a legislative councillor, President of the Toronto and Lake Huron Railroad, Governor of the British American Fire and Life Assurance Company and President of the Board of Trade." Johnson's conclusion contests the common assertion that "none of the leading members of the Compact were business men, and ... the system of values typical of the Compact accorded scant respect to business wealth as such." The overlapping social, political and economic leadership roles of the Family Compact demonstrates, he argues, that they were not a political elite taking political decisions in a vacuum, but an overlapping elite whose political and economic activities cannot be entirely separated from each other. They might even be called 'entrepreneurs', most of whose political views may have been highly conservative but whose economic outlook was clearly 'developmental'.The Family Compact's role in the Welland Canal is one example. Elite Upper Canadians sought "gentility" including the acquisition of landed estates, roles as Justices of the Peace, military service, the pursuit of "improved farming", grammar school education, ties to the Church of England – all in combination with the acquisition of wealth through the Bank of Upper Canada amongst others. It is through the pursuit of gentility that the Family Compact was born.

Constitutional context

Upper Canada did not have a hereditary nobility. In its place, senior members of Upper Canada bureaucracy, theExecutive Council of Upper Canada

The Executive Council of Upper Canada had a similar function to the Cabinet in England but was not responsible to the Legislative Assembly. Members of the Executive Council were not necessarily members of the Legislative Assembly but were usually ...

and Legislative Council of Upper Canada

The Legislative Council of Upper Canada was the upper house governing the province of Upper Canada. Modelled after the British House of Lords, it was created by the Constitutional Act of 1791. It was specified that the council should consist ...

, made up the elite of the compact. W.S. Wallace, ''The Family Compact''Toronto 1915. These men sought to solidify their personal positions into family dynasties and acquire all the marks of gentility. They used their government positions to extend their business and speculative interests. The origins of the Family Compact lay in overlapping appointments made to the Executive and Legislative Council of Upper Canada. The Councils were intended to operate independently. Section 38 of the Constitutional Act of 1791 referred to the independence of the offices indirectly. While

Sir Guy Carleton

Guy Carleton, 1st Baron Dorchester (3 September 1724 – 10 November 1808), known between 1776 and 1786 as Sir Guy Carleton, was an Anglo-Irish soldier and administrator. He twice served as Governor of the Province of Quebec, from 1768 to 177 ...

, Lieutenant Governor of Lower Canada, pointed out that the offices were intended to be separate, Lord Grenville set the wheels in motion with John Graves Simcoe

John Graves Simcoe (25 February 1752 – 26 October 1806) was a British Army general and the first lieutenant governor of Upper Canada from 1791 until 1796 in southern Ontario and the watersheds of Georgian Bay and Lake Superior. He founded Yor ...

Lieutenant Governor of Upper Canada by pointing out that there was no legal impediment to prevent cross-appointments. Simcoe used the vague statement in Section 38 to make the following appointments

The Family Compact exerted influence over the government through the Executive Council and Legislative Council, the advisers to the Lieutenant Governor

A lieutenant governor, lieutenant-governor, or vice governor is a high officer of state, whose precise role and rank vary by jurisdiction. Often a lieutenant governor is the deputy, or lieutenant, to or ranked under a governor — a "second-in-comm ...

, leaving the popularly elected Legislative Assembly with little real power. As became clear with Lieutenant Governor Sir Francis Bond Head, the influence of the Family Compact could be quite limited as well. Members ensured their conservative friends held the important administrative and judicial positions in the colony through political patronage.

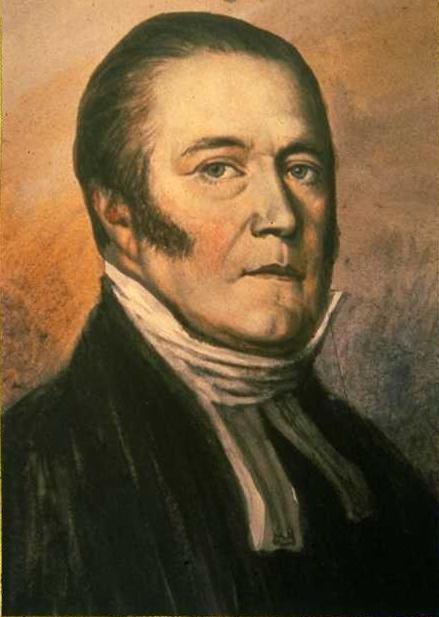

Membership

The centre of the compact wasYork

York is a cathedral city with Roman origins, sited at the confluence of the rivers Ouse and Foss in North Yorkshire, England. It is the historic county town of Yorkshire. The city has many historic buildings and other structures, such as a ...

(later renamed Toronto

Toronto ( ; or ) is the capital city of the Canadian province of Ontario. With a recorded population of 2,794,356 in 2021, it is the most populous city in Canada and the fourth most populous city in North America. The city is the anch ...

), the capital. Its most important member was Bishop John Strachan; many of the other members were his former students, or people who were related to him. The most prominent of Strachan's pupils was Sir John Beverley Robinson

Sir John Beverley Robinson, 1st Baronet, (26 July 1791 – 31 January 1863) was a lawyer, judge and political figure in Upper Canada. He was considered the leader of the Family Compact, a group of families which effectively controlled the e ...

who was from 1829 the Chief Justice of Upper Canada

The Province of Upper Canada (french: link=no, province du Haut-Canada) was a Province, part of The Canadas, British Canada established in 1791 by the Kingdom of Great Britain, to govern the central third of the lands in British North Americ ...

for 34 years. The rest of the members were mostly descendants of United Empire Loyalists

United Empire Loyalists (or simply Loyalists) is an honorific title which was first given by the 1st Lord Dorchester, the Governor of Quebec, and Governor General of The Canadas, to American Loyalists who resettled in British North America dur ...

or recent upper-class British settlers such as the Boulton family, builders of the Grange

Grange may refer to:

Buildings

* Grange House, Scotland, built in 1564, and demolished in 1906

* Grange Estate, Pennsylvania, built in 1682

* Monastic grange, a farming estate belonging to a monastery

Geography Australia

* Grange, South Austr ...

.

A triumvirate of lawyers, Levius Sherwood (speaker of the Legislative Council, judge in the Court of King's Bench), Judge Jonas Jones

Jonas Jones (May 19, 1791 – July 30, 1848) was a lawyer, judge, farmer, and political figure in Upper Canada.

Life

Jones was born in Augusta Township, Upper Canada in 1791, the son of Ephraim Jones. He was educated at John Strachan's sc ...

, and Attorney General Henry John Boulton

Henry John Boulton, (1790 – June 18, 1870) was a lawyer and political figure in Upper Canada and the Province of Canada, as well as Chief Justice of Newfoundland.

Boulton began his legal career under the tutelage of John Beverly Robi ...

were linked by professional and business ties, and by marriage; both Sherwood and Boulton being married to Jones’ sisters. Collectively, their extended family (if we include the Robinsons, and James B. Macaulay, Boulton’s former clerk) comprise three quarters of the "Family Compact" listed by Mackenzie in 1833.

Loyalist ideology

The uniting factors amongst the compact were its loyalist tradition, hierarchical class structure and adherence to the established Anglican church. Leaders such as Sir John Robinson and John Strachan proclaimed it an ideal government, especially as contrasted with the rowdy democracy in the nearby United States. Not all views of the elite were universally shared, but a critical element was the idea of "loyalty".David Mills, ''Idea of Loyalty in Upper Canada, 1784–1850'', 1988 . The original members of the Family Compact wereUnited Empire Loyalist

United Empire Loyalists (or simply Loyalists) is an honorific title which was first given by the 1st Lord Dorchester, the Governor of Quebec, and Governor General of The Canadas, to American Loyalists who resettled in British North America ...

s who had fled the United States immediately after the Revolutionary War. The War of 1812 led the British to suspect the loyalty of the so-called "Later Loyalists" – "Americans" who had emigrated after 1800 for land. The issue came to a head around 1828 in the " Alien Question". Following the war, the colonial government took active steps to prevent Americans from swearing allegiance, thereby making them ineligible to obtain land grants. Without land they could not vote or hold office.

The issue became a provincewide complaint in 1828 when Barnabas Bidwell

Barnabas Bidwell (August 23, 1763 – July 27, 1833) was an author, teacher and politician of the late 18th and early 19th centuries, active in Massachusetts and Upper Canada (now Ontario). Educated at Yale, he practised law in western Massach ...

was deprived of his seat in the Legislative Assembly. Educated at Yale

Yale University is a private research university in New Haven, Connecticut. Established in 1701 as the Collegiate School, it is the third-oldest institution of higher education in the United States and among the most prestigious in the wor ...

, he practiced law in western Massachusetts and served as treasurer of Berkshire County

Berkshire County (pronounced ) is a county on the western edge of the U.S. state of Massachusetts. As of the 2020 census, the population was 129,026. Its largest city and traditional county seat is Pittsfield. The county was founded ...

. He served in the state legislature

A state legislature is a legislative branch or body of a political subdivision in a federal system.

Two federations literally use the term "state legislature":

* The legislative branches of each of the fifty state governments of the United Sta ...

, and was the state attorney general from 1807 to 1810, when irregularities in the Berkshire County books prompted his flight to Upper Canada. There he won a seat in the provincial assembly, but was denied on account of his status as a fugitive from justice. A provincewide petitioning campaign by these numerically superior "aliens" led the British government to grant them citizenship retroactively. In the minds of the Family Compact, they remained politically suspect and barred from positions of power.

Levers of power

In the absence of a landed elite, these men believed that the law should be the basis of social preeminence. Bound by the ideals of public service and a spirit of loyalty to king, church and empire, solidified in the crucible of theWar of 1812

The War of 1812 (18 June 1812 – 17 February 1815) was fought by the United States of America and its indigenous allies against the United Kingdom and its allies in British North America, with limited participation by Spain in Florida. It be ...

, they used the Law Society of Upper Canada as a means of regulating entry to elite positions of power.

Government position

Executive and Legislative Councils

The Executive Council was composed of local advisers who provided the colonially appointed Lieutenant Governor with advice on the daily workings of government, and especially with appointments to the administration. Members of the Executive Council were not necessarily members of the Legislative Assembly but were usually members of the Legislative Council. The longest serving members were James Baby (1792–1833), John Strachan (1815–1836), George Markland (1822–1836), and Peter Robinson (1823–1836). The Legislative Council of Upper Canada was theupper house

An upper house is one of two chambers of a bicameral legislature, the other chamber being the lower house.''Bicameralism'' (1997) by George Tsebelis The house formally designated as the upper house is usually smaller and often has more restric ...

governing the province of Upper Canada

The Province of Upper Canada (french: link=no, province du Haut-Canada) was a Province, part of The Canadas, British Canada established in 1791 by the Kingdom of Great Britain, to govern the central third of the lands in British North Americ ...

. It was modelled after the British House of Lords

The House of Lords, also known as the House of Peers, is the upper house of the Parliament of the United Kingdom. Membership is by appointment, heredity or official function. Like the House of Commons, it meets in the Palace of Westminst ...

. Members were appointed, often for life. The longest serving members were James Baby (1792–1833), Jacob Mountain Anglican Bishop of Quebec (1794–1825), John Strachan (1820–1841), George Markland (1822–1836), Peter Robinson (1823–1836), Thomas Talbot (1809–1841), Thomas Clark (1815–1841), William Dickson (1815–1841), John Henry Dunn (1822–1841), William Allan (1825–1841).

Magistracy and Courts of Quarter Sessions

Justices of the Peace were appointed by the Lieutenant Governor. Any two justices meeting together could form the lowest level of the justice system, the Courts of Request. ACourt of Quarter Sessions

The courts of quarter sessions or quarter sessions were local courts traditionally held at four set times each year in the Kingdom of England from 1388 (extending also to Wales following the Laws in Wales Act 1535). They were also established in ...

was held four times a year in each district composed of all the resident justices. The Quarter Sessions met to oversee the administration of the district and deal with legal cases. They formed, in effect, the municipal government ''and'' judiciary until an area was incorporated as either a Police Board or a City after 1834. The men appointed to the magistracy tended to be United Empire Loyalists or "Half-pay Half-pay (h.p.) was a term used in the British Army and Royal Navy of the 18th, 19th and early 20th centuries to refer to the pay or allowance an officer received when in retirement or not in actual service.

Past usage United Kingdom

In the En ...

" military officers who were placed in semi-retirement after the Napoleonic Wars.

Law Society and Juvenile Advocate's Society

The Law Society was created in 1797 to regulate the legal profession in the province. The society is headed by a Treasurer. Every Treasurer of the society before 1841 was a member of the Family Compact with the exception of William Warren Baldwin. The control that the Family Compact exerted over the legal profession and the corruption that resulted was most clearly demonstrated in the "Types Riot" in 1826, in which the printing press of William Lyon Mackenzie was destroyed by the young lawyers of the Juvenile Advocate's Society with the complicity of the Attorney General, the Solicitor General and the magistrates ofToronto

Toronto ( ; or ) is the capital city of the Canadian province of Ontario. With a recorded population of 2,794,356 in 2021, it is the most populous city in Canada and the fourth most populous city in North America. The city is the anch ...

.

Mackenzie had published a series of satires under the pseudonym of "Patrick Swift, nephew of Jonathan Swift

Jonathan Swift (30 November 1667 – 19 October 1745) was an Anglo-Irish satirist, author, essayist, political pamphleteer (first for the Whigs, then for the Tories), poet, and Anglican cleric who became Dean of St Patrick's Cathedral, Du ...

" in an attempt to humiliate the members of the Family Compact running for the board of the Bank of Upper Canada, and Henry John Boulton the Solicitor General, in particular. Mackenzie's articles worked, and they lost control. In revenge they sacked Mackenzie's press, throwing the type into the lake. The "juvenile advocates" were the students of the Attorney General and the Solicitor General, and the act was performed in broad daylight in front of William Allan, bank president and magistrate. They were never charged, and it was left to Mackenzie to launch a civil lawsuit instead.

There are three implications of the Types riot according to historian Paul Romney. First, he argues the riot illustrates how the elite's self-justifications regularly skirted the rule of law they held out as their Loyalist mission. Second, he demonstrated that the significant damages Mackenzie received in his civil lawsuit against the vandals did not reflect the soundness of the criminal administration of justice in Upper Canada. And lastly, he sees in the Types riot "the seed of the Rebellion" in a deeper sense than those earlier writers who viewed it simply as the start of a highly personal feud between Mackenzie and the Family Compact. Romney emphasizes that Mackenzie's personal harassment, the "outrage", served as a lightning rod of discontent because so many Upper Canadians had faced similar endemic abuses and hence identified their political fortunes with his.

Church of England

Established church

In 1836, as he was preparing to leave office, Lt Governor John Colborne endowed 44 Church of England rectories with about of land each ( in all) in an effort to make the church more self-sufficient and less dependent on government aid.Clergy reserves

The Clergy Corporation was incorporated in 1819 to manage the Clergy Reserves. After John Strachan was appointed to the Executive Council, the advisory body to the Lieutenant Governor, in 1815, he began to push for the Church of England's autonomous control of the clergy reserves on the model of the Clergy Corporation created in Lower Canada in 1817. Although all clergymen in the Church of England were members of the body corporate, the act prepared in 1819 by Strachan's former student, Attorney General John Beverly Robinson, also appointed the Inspector General and the Surveyor General to the board, and made a quorum of three for meetings; these two public officers also sat on the Legislative Council with Strachan. These three were usually members of the Family Compact.Upper Canada College and Kings College

Grammar schools provided a classical education and were preparation for higher learning and entry into the law or the ministry. Entrance was limited by high tuition fees, even though they were government supported. Common schools for teaching basic education received little support or regulation in comparison at this time. Working class education was trades based through the Master-journeyman-apprentice relationship.

Grammar schools provided a classical education and were preparation for higher learning and entry into the law or the ministry. Entrance was limited by high tuition fees, even though they were government supported. Common schools for teaching basic education received little support or regulation in comparison at this time. Working class education was trades based through the Master-journeyman-apprentice relationship.

Upper Canada College

Upper Canada College (UCC) is an elite, all-boys, private school in Toronto, Ontario, operating under the International Baccalaureate program. The college is widely described as the country's most prestigious preparatory school, and has produce ...

was the successor to the Home District Grammar School taught by John Strachan, which became the Royal Grammar School in 1825. Upper Canada College was founded in 1829 by Lieutenant Governor Sir John Colborne (later Lord Seaton), to serve as a feeder school to the newly established King's College. It was modelled on the great public schools of Britain, most notably Eton.''Upper Canada College, 1829–1979: Colborne's Legacy''; Howard, Richard; Macmillan Company of Canada, 1979Upper Canada College: HistoryThe school began teaching in the original Royal Grammar School and for several years the two organizations were essentially unified. On March 15, 1827, a

royal charter

A royal charter is a formal grant issued by a monarch under royal prerogative as letters patent. Historically, they have been used to promulgate public laws, the most famous example being the English Magna Carta (great charter) of 1215, b ...

was formally issued for King's College (now the University of Toronto

The University of Toronto (UToronto or U of T) is a public research university in Toronto, Ontario, Canada, located on the grounds that surround Queen's Park. It was founded by royal charter in 1827 as King's College, the first institution ...

). The granting of the charter was largely the result of intense lobbying by John Strachan, who took office as the first president of the college. The original three-storey Greek Revival

The Greek Revival was an architectural movement which began in the middle of the 18th century but which particularly flourished in the late 18th and early 19th centuries, predominantly in northern Europe and the United States and Canada, but a ...

school building was constructed on the present site of Queen's Park. Upper Canada College merged with King's College for a period after 1831. Under Strachan's guidance, King's College was a religious institution that closely aligned with the Church of England

The Church of England (C of E) is the established Christian church in England and the mother church of the international Anglican Communion. It traces its history to the Christian church recorded as existing in the Roman province of Brit ...

and the Family Compact.

Bank of Upper Canada

TheBank of Upper Canada

The Bank of Upper Canada was established in 1821 under a charter granted by the legislature of Upper Canada in 1819 to a group of Kingston merchants. The charter was appropriated by the more influential Executive Councillors to the Lt. Governor, t ...

's principal promoters were John Strachan and William Allan. Allan, who became president, was also an Executive and Legislative Councillor. He, like Strachan, played a key role in solidifying the Family Compact, and ensuring its influence within the colonial state. Henry John Boulton

Henry John Boulton, (1790 – June 18, 1870) was a lawyer and political figure in Upper Canada and the Province of Canada, as well as Chief Justice of Newfoundland.

Boulton began his legal career under the tutelage of John Beverly Robi ...

, the solicitor general, author of the bank incorporation bill, and the bank's lawyer, admitted the bank was a "terrible engine in the hands of the provincial administration". The government, its officers, and legislative councillors owned 5,381 of its 8,000 shares. The Lieutenant Governor appointed four of the bank's fifteen directors making for a tight bond between the nominally private company and the state. Forty-four men served as bank directors during the 1830s; eleven of them were executive councillors, fifteen of them were legislative councillors, and thirteen were magistrates in Toronto. More importantly, all 11 men who had ever sat on the Executive Council also sat on the board of the bank at one time or another. Ten of these men also sat on the Legislative Council. The overlapping membership on the boards of the Bank of Upper Canada and on the Executive and Legislative Councils served to integrate the economic and political activities of church, state, and the "financial sector". These overlapping memberships reinforced the oligarchic nature of power in the colony and allowed the administration to operate without any effective elective check. Despite these tight bonds, the Receiver General

A receiver general (or receiver-general) is an officer responsible for accepting payments on behalf of a government, and for making payments to a government on behalf of other parties.

See also

* Treasurer

* Receiver General for Canada

* Rece ...

, the reform leaning John Henry Dunn

John Henry Dunn (1792 – April 21, 1854) was a public official and businessman in Upper Canada, who later entered politics in the Province of Canada. Born on Saint Helena of English parents, he came to Upper Canada as a young man to take u ...

, refused to use the bank for government business. The Bank of Upper Canada held a near monopoly, and as a result, controlled much of the trade in the province.

Land and agriculture

The role of speculation in the vacant lands of Upper Canada ensured the development of group solidarity and cohesion of interest among the members of the Family Compact. Of the 26 largest landowners in Peel County between 1820 and 1840, 23 were absentee proprietors, of whom 17 were involved in the administration of the province; of these 17, 12 were part of the Family Compact. Society and politics in Upper Canada were dominated by interest and connection based on landed property, and only secondarily affected by ideologies and personalities. Members of the Family Compact were interested in building up estates in which they imitated the "improved farming" methods of the English aristocracy. "Improved farming" refers to a capital-intensive form of farming introduced by the "improving landlords" of Great Britain on large estates that were beginning to be farmed as capitalist enterprises. These improved farming methods were introduced to Upper Canada by the half-pay military officers from aristocratic background who tended to become magistrates in Upper Canada and build large estates. "Mixed or improved farming was one part of a total life-style ... As well as permitting them to practice improved farming and to develop a reasonably elegant life-style, their financial independence allowed them the leisure time necessary for them to act as 'leaders' of their community." The city of Toronto was surrounded by the estates of the Family Compact. One of these estates, the Grange, was owned by Boulton and was one of the chief centres of the Family Compact. Although many meetings took place at the Grange, John Ross Robertson noted the small dining room, which could not hold more than 14 people, probably meant that many of the stories about the Family Compact gatherings were probably exaggerated.Opposition

Reform movement

The Family Compact was one of many, distinguished primarily by its access to the offices of state. Other compact groups, such as the Baldwin-Russell-Sullivan family, in fact, shared many of the same values. The primary opposition to the Family Compact and these loyalist ideals came from the reform movement led by William Lyon Mackenzie. His ability to agitate through his newspaper ''TheColonial Advocate

The ''Colonial Advocate'' was a weekly political journal published in Upper Canada during the 1820s and 1830s. First published by William Lyon Mackenzie on May 18, 1824, the journal frequently attacked the Upper Canada aristocracy known as the ...

'' and petitioning was effective. Speeches and petitions led directly to the redress of grievances in Upper Canada that otherwise had no means of redress.

Mackenzie's frustration with Compact control of the government was a catalyst for the failed Upper Canada Rebellion

The Upper Canada Rebellion was an insurrection against the oligarchic government of the British colony of Upper Canada (present-day Ontario) in December 1837. While public grievances had existed for years, it was the rebellion in Lower Canada (p ...

of 1837. Their hold on the government was reduced with the creation of the united Province of Canada

The Province of Canada (or the United Province of Canada or the United Canadas) was a British colony in North America from 1841 to 1867. Its formation reflected recommendations made by John Lambton, 1st Earl of Durham, in the Report on the ...

and later the installation of the system of Responsible Government

Responsible government is a conception of a system of government that embodies the principle of parliamentary accountability, the foundation of the Westminster system of parliamentary democracy. Governments (the equivalent of the executive br ...

in Canada.

Colborne Clique

The Colborne Clique, named for John Colborne, 1st Baron Seaton, was a federation united by geography inGoderich, Ontario

Goderich ( or ) is a town in the Canadian province of Ontario and is the county seat of Huron County. The town was founded by John Galt and William "Tiger" Dunlop of the Canada Company in 1827. First laid out in 1828, the town is named af ...

, Scottish heritage, time of immigration to Upper Canada, and an association with the Dunlop brothers William "Tiger" Dunlop and Robert Graham Dunlop

Robert Graham Dunlop (October 1, 1790 – February 28, 1841) was a British naval officer and political figure in Upper Canada.

He was born in Keppoch, Scotland in 1790 and joined the Royal Navy at the age of 13. He became a lieutenant while ...

. Although their prime animosity was towards the Canada Company

The Canada Company was a private British land development company that was established to aid in the colonization of a large part of Upper Canada. It was incorporated by royal charter on August 19, 1826, under an act of the British parliament,, ...

, the Canada Company and the Family Compact were seen as one and the same thing causing the Colbornites to align themselves firmly against the Family Compact.

Members:

* John Galt

* William Tiger Dunlop

William is a male given name of Germanic origin.Hanks, Hardcastle and Hodges, ''Oxford Dictionary of First Names'', Oxford University Press, 2nd edition, , p. 276. It became very popular in the English language after the Norman conquest of Eng ...

* Robert Graham Dunlop

Robert Graham Dunlop (October 1, 1790 – February 28, 1841) was a British naval officer and political figure in Upper Canada.

He was born in Keppoch, Scotland in 1790 and joined the Royal Navy at the age of 13. He became a lieutenant while ...

* Henry Hyndman

Henry Mayers Hyndman (; 7 March 1842 – 20 November 1921) was an English writer, politician and socialist.

Originally a conservative, he was converted to socialism by Karl Marx's ''Communist Manifesto'' and launched Britain's first left-wi ...

* Anthony Van Egmond

Anthony Van Egmond (born Antonij Jacobi Willem Gijben, 10 March 17785 January 1838) was purportedly a Dutch Napoleonic War veteran. He became one of the first settlers and business people in the Huron Tract in present-day southwestern Ontario Ca ...

* William Dickson

* John Longworth

* David Clark

Post-Rebellion decline

After the Rebellions of 1837,Lord Durham

Earl of Durham is a title in the Peerage of the United Kingdom. It was created in 1833 for the Whig politician and colonial official John Lambton, 1st Baron Durham. Known as "Radical Jack", he played a leading role in the passing of the Gre ...

was sent to Canada to make recommendations on reform. Durham's Report on the Affairs of British North America states that it is impossible "To understand how any English statesman could have ever imagined that representative and irresponsible government could be successfully combined."

However, rather than pursue the Reformers' dream of responsible government

Responsible government is a conception of a system of government that embodies the principle of parliamentary accountability, the foundation of the Westminster system of parliamentary democracy. Governments (the equivalent of the executive br ...

, the British imposed the Union of the Canadas. The aim of the new Governor General, Charles Poulett Thomson

Charles Poulett Thomson, 1st Baron Sydenham, (13 September 1799 – 19 September 1841) was a British businessman, politician, diplomat and the first Governor General of the united Province of Canada.

was to strengthen the power of the Governor General, to minimize the impact of the numerically superior French vote, and to build a "middle party" that answered to him, rather than the Family Compact or the Reformers. Thomson was a Whig who believed in rational government, not "responsible government". But he was also intent on marginalizing the influence of the Family Compact.

The Family Compact began to reconfigure itself after 1841 as it was squeezed out of public life in the new Province of Canada

The Province of Canada (or the United Province of Canada or the United Canadas) was a British colony in North America from 1841 to 1867. Its formation reflected recommendations made by John Lambton, 1st Earl of Durham, in the Report on the ...

. The conservative values of the Family Compact was succeeded by the Upper Canada Tories

The Tory movement in Upper Canada was formed from the elements of the Family Compact following the War of 1812. It was an early political party, merely a group of like minded conservative elite in the early days of Canada. The Tories would later ...

after 1841. The current Canadian establishment grew out of the Family Compact.Peter C. Newman

Peter Charles Newman (born May 10, 1929) is a Canadian journalist and writer.

Life and career

Born in Vienna, Austria, Newman emigrated from Nazi-occupied Czechoslovakia to Canada in 1940 as a Jewish refugee. His parents were Wanda Maria and ...

, ''The Canadian Establishment Vol. One'', McClelland and Stewart, 1975. Although the families and names changed, the basic template for power and control remained the same through to the end of World War II

World War II or the Second World War, often abbreviated as WWII or WW2, was a world war that lasted from 1939 to 1945. It involved the World War II by country, vast majority of the world's countries—including all of the great power ...

. With greater immigration from a variety of nations and cultures came the meritocracy so desired during the early years of Upper Canada.

However, as John Porter noted, a form of Family Compact in Canadian business and politics is to be expected.

Canada is probably not unlike other western industrial nations in relying heavily on its elite groups to make major decisions and to determine the shape and direction of its development. The nineteenth-century notion of a liberal citizen-participating democracy is obviously not a satisfactory model by which to examine the processes of decision-making in either the economic or the political contexts. ... If power and decision-making must always rest with elite groups, there can at least be open recruitment from all classes into the elite.John Porter, ''The Vertical Mosaic: an analysis of social class and power in Canada'', Toronto, University of Toronto Press, 1965. p. 558.

References

Bibliography

* John G. Bourinot. ''Canada under British Rule 1790—1900''. Toronto, Copp, Clark Company, 1901. * Patrick Brode. ''Sir John Beverley Robinson: Bone and Sinew of the Compact'', 1984. * G. M. Craig. ''Upper Canada: The Formative Years, 1784–1841'' (1963). * Donald Creighton. ''John A. Macdonald The Young Politician''. Toronto: Macmillan & Co. 1952. * David W. L. Earl, ed. ''The Family Compact: Aristocracy or Oligarchy?'', 1967. * David Gagan. "Property and 'Interest'; Some Preliminary Evidence of Land Speculation by the 'Family Compact' in Upper Canada 1820–1840," ''Ontario History,'' March 1978, Vol. 70 Issue 1, pp. 63–70 * A. Ewart and J. Jarvis, ''Canadian Historical Review'', The Personnel of the Family Compact 1926. * Robert C. Lee. ''The Canada Company and the Huron Tract, 1826—1853 Personalities, Profits and Politics'' Toronto: Natural Heritage Books, 2004. * Kathleen Macfarlane Lizars. ''In the Days of the Canada Company: The Story of the Settlement of the Huron Tract and a view of the Social Life of the Period, 1825—1850''. Nabu Public Domain Reprints. * David Mills. ''Idea of Loyalty in Upper Canada, 1784–1850''. 1988. . * Graeme Patterson. ''An Enduring Canadian Myth: Responsible Government and the Family Compact'' / 1989 * Gilbert Parker and Claude G. Bryan. ''Old Quebec''. London: Macmillan & Co. 1903. * W. Stewart Wallace. ''The Family Compact'' (Toronto, 1915). * W. Stewart Wallace, ed., ''The Encyclopedia of Canada'', Vol. II, Toronto, University Associates of Canada, 1948, 411 p., p. 318.Further reading

* * * * * Wrong, George M.,Canada and the American Revolution: The Disruption of the First British Empire

' (1935) *

External links

* ttps://web.archive.org/web/20110610012755/http://www.archives.gov.on.ca/english/archival-records/interloan/canco.aspx ''Archives of Ontario, Canada Company Fonds.''

''Historical Narratives of Early Canada'' by W.R. Wilson

{{Ontario provincial political parties Political parties in Upper Canada Political history of Ontario