Ex parte Crow Dog on:

[Wikipedia]

[Google]

[Amazon]

''Ex parte Crow Dog'', 109 U.S. 556 (1883), is a landmark decision of the Supreme Court of the United States that followed the death of one member of a Native American tribe at the hands of another on reservation land.

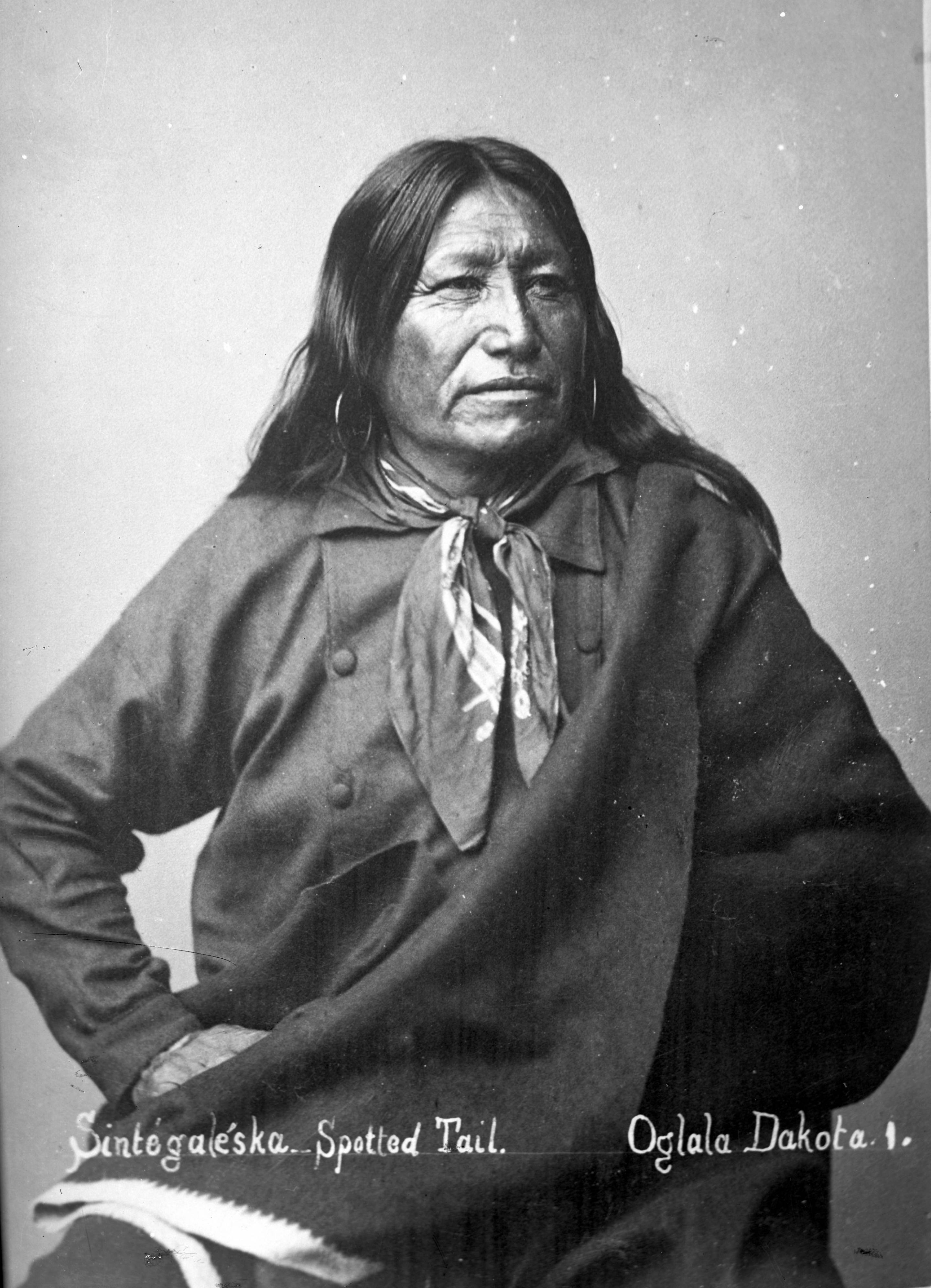

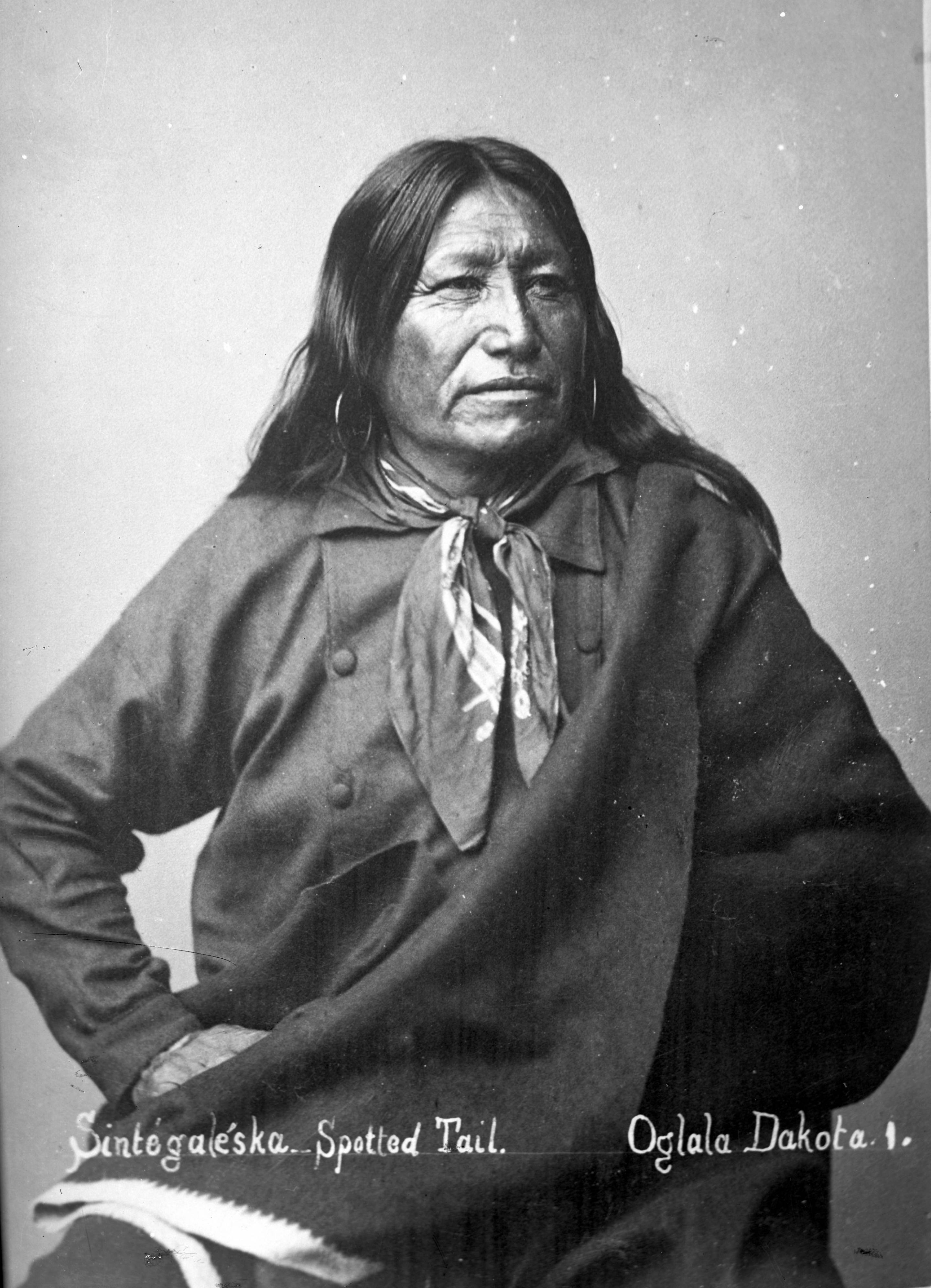

On August 5, 1881, Crow Dog shot and killed Spotted Tail, who was the uncle of Oglala Lakota war leader Crazy Horse. Spotted Tail had not been selected as a chief by the tribe, but instead had been appointed by General George Crook in 1876, which hurt him in the view of many of the tribe. He was viewed as an accommodationist and the Bureau of Indian Affairs (BIA) referred to him as the "great peace chief." He also supervised the tribal police of about 300 men. In contrast, Crow Dog was a traditionalist and although he had been a captain in the tribal police, he was fired by Spotted Tail sometime after a July 4, 1881, confrontation during which Crow Dog pointed a rifle at Spotted Tail.

On August 5, tensions further escalated at a tribal meeting where a number of tribal members criticized Spotted Tail for taking Light-in-the-Lodge, the wife of Medicine Bear, a crippled man, into his household as his second wife. It was believed that the killing occurred that day as the result of Crow Dog and Spotted Tail meeting, both armed, and mistaking the other man's intentions. In another version of the story, Crow Dog was appointed by the tribal council to head the tribal police, which undermined the authority of Spotted Tail. Crow Dog discovered that Spotted Tail was taking money from ranchers for "grazing rights" and he denounced him for it, while Spotted Tail defended the practice. A later conflict with the Indian agent forced the tribal police to disband, and Crow Dog lost his position. This version makes no mention of another man's wife being the reason for the killing, and states that Crow Dog ambushed Spotted Tail to gain power in the tribe. There is no consensus among historians as to which events happened as described.

In either case, the matter was settled within the tribe, following longstanding tribal custom, by Crow Dog making a

On August 5, 1881, Crow Dog shot and killed Spotted Tail, who was the uncle of Oglala Lakota war leader Crazy Horse. Spotted Tail had not been selected as a chief by the tribe, but instead had been appointed by General George Crook in 1876, which hurt him in the view of many of the tribe. He was viewed as an accommodationist and the Bureau of Indian Affairs (BIA) referred to him as the "great peace chief." He also supervised the tribal police of about 300 men. In contrast, Crow Dog was a traditionalist and although he had been a captain in the tribal police, he was fired by Spotted Tail sometime after a July 4, 1881, confrontation during which Crow Dog pointed a rifle at Spotted Tail.

On August 5, tensions further escalated at a tribal meeting where a number of tribal members criticized Spotted Tail for taking Light-in-the-Lodge, the wife of Medicine Bear, a crippled man, into his household as his second wife. It was believed that the killing occurred that day as the result of Crow Dog and Spotted Tail meeting, both armed, and mistaking the other man's intentions. In another version of the story, Crow Dog was appointed by the tribal council to head the tribal police, which undermined the authority of Spotted Tail. Crow Dog discovered that Spotted Tail was taking money from ranchers for "grazing rights" and he denounced him for it, while Spotted Tail defended the practice. A later conflict with the Indian agent forced the tribal police to disband, and Crow Dog lost his position. This version makes no mention of another man's wife being the reason for the killing, and states that Crow Dog ambushed Spotted Tail to gain power in the tribe. There is no consensus among historians as to which events happened as described.

In either case, the matter was settled within the tribe, following longstanding tribal custom, by Crow Dog making a

Following the killing and the settlement under tribal customs, the Indian agent had Crow Dog arrested and taken to Fort Niobrara, Nebraska. Within 20 days, the U.S. Attorney General and the Secretary of the Interior concluded that the Federal Enclave Act of 1854 as modified by the

Following the killing and the settlement under tribal customs, the Indian agent had Crow Dog arrested and taken to Fort Niobrara, Nebraska. Within 20 days, the U.S. Attorney General and the Secretary of the Interior concluded that the Federal Enclave Act of 1854 as modified by the

Justice

Justice rimes committed by one Indian against the person or property of another Indian, nor to/nowiki> any Indian committing any offense in the Indian country who has been punished by the local law of the tribe" (brackets in original). Matthews rejected the contention of the United States that the 1868 Treaty of Fort Laramie implicitly repealed the exceptions to prosecution. He stated that since the law had not been amended or changed, and since implied repeals are not favored unless the implication is necessary, to allow such a repeal would be to reverse the general policy of the United States. Matthews said that such a repeal required a "clear expression of the intention of Congress," which was not present in the case. In a clear evocation of the principle of tribal sovereignty, Matthews stated:

Crow Dog

Crow Dog (also Kȟaŋǧí Šúŋka, Jerome Crow Dog; 1833 – August 1912) was a Brulé Lakota subchief, born at Horse Stealing Creek, Montana Territory.

Family

He was the nephew of former principal chief Conquering Bear, who was killed in 1854 in ...

was a member of the Brulé

The Brulé are one of the seven branches or bands (sometimes called "sub-tribes") of the Teton (Titonwan) Lakota American Indian people. They are known as Sičhą́ǧu Oyáte (in Lakȟóta) —Sicangu Oyate—, ''Sicangu Lakota, o''r "Burnt ...

band of the Lakota

Lakota may refer to:

* Lakota people, a confederation of seven related Native American tribes

*Lakota language, the language of the Lakota peoples

Place names

In the United States:

* Lakota, Iowa

* Lakota, North Dakota, seat of Nelson County

* La ...

Sioux. On August 5, 1881 he shot and killed Spotted Tail, a Lakota chief; there are different accounts of the background to the killing. The tribal council dealt with the incident according to Sioux tradition, and Crow Dog paid restitution to the dead man's family. However, the U.S. authorities then prosecuted Crow Dog for murder in a federal court. He was found guilty and sentenced to hang.

The defendant then petitioned the Supreme Court for a writ of habeas corpus

''Habeas corpus'' (; from Medieval Latin, ) is a recourse in law through which a person can report an unlawful detention or imprisonment to a court and request that the court order the custodian of the person, usually a prison official, t ...

, arguing that the federal court had no jurisdiction to try cases where the offense had already been tried by the tribal council. The court found unanimously for the plaintiff and Crow Dog was therefore released. This case was the first time in history that an Indian was held on trial for the murder of another Indian. The case led to the Major Crimes Act

The Major Crimes Act (U.S. Statutes at Large, 23:385)plenary power

A plenary power or plenary authority is a complete and absolute power to take action on a particular issue, with no limitations. It is derived from the Latin term ''plenus'' ("full").

United States

In United States constitutional law, plenary p ...

legal doctrine that has been used in Indian case law to limit tribal sovereignty.

Background

Treaties and statutes

Crow Dog was aBrulé

The Brulé are one of the seven branches or bands (sometimes called "sub-tribes") of the Teton (Titonwan) Lakota American Indian people. They are known as Sičhą́ǧu Oyáte (in Lakȟóta) —Sicangu Oyate—, ''Sicangu Lakota, o''r "Burnt ...

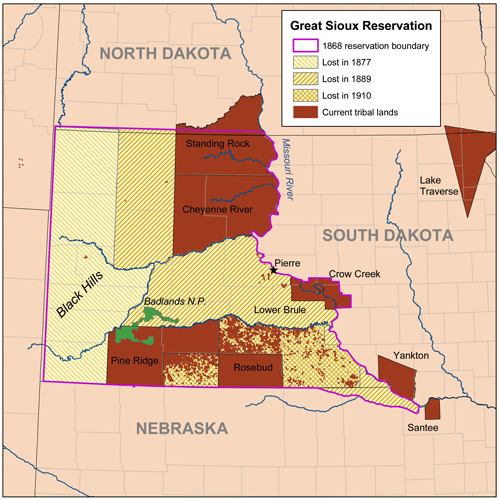

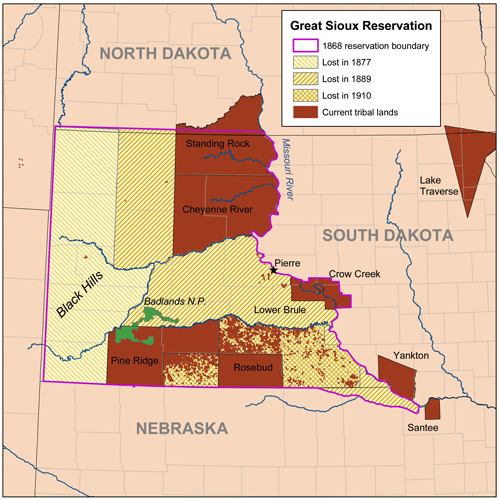

subchief who lived on the Great Sioux Reservation

The Great Sioux Reservation initially set aside land west of the Missouri River in South Dakota and Nebraska for the use of the Lakota Sioux, who had dominated this territory. The reservation was established in the Fort Laramie Treaty of 1868 ...

, in the part that is now the Rosebud Indian Reservation in south-central South Dakota

South Dakota (; Sioux: , ) is a U.S. state in the North Central region of the United States. It is also part of the Great Plains. South Dakota is named after the Lakota and Dakota Sioux Native American tribes, who comprise a large porti ...

on its border with Nebraska

Nebraska () is a state in the Midwestern region of the United States. It is bordered by South Dakota to the north; Iowa to the east and Missouri to the southeast, both across the Missouri River; Kansas to the south; Colorado to the sout ...

. The tribe had made several treaties with the United States

The United States of America (U.S.A. or USA), commonly known as the United States (U.S. or US) or America, is a country primarily located in North America. It consists of 50 states, a federal district, five major unincorporated territori ...

, the most significant being the 1868 Treaty of Fort Laramie. This treaty provided that Indians agreed to turn over those accused of crimes to the Indian agent

In United States history, an Indian agent was an individual authorized to interact with American Indian tribes on behalf of the government.

Background

The federal regulation of Indian affairs in the United States first included development of t ...

, a representative of the U.S. government in Indian affairs. The treaty also stipulated that tribal members would stay on the reservation provided (which included the Black Hills

The Black Hills ( lkt, Ȟe Sápa; chy, Moʼȯhta-voʼhonáaeva; hid, awaxaawi shiibisha) is an isolated mountain range rising from the Great Plains of North America in western South Dakota and extending into Wyoming, United States. Black ...

) unless three-fourths of the adult male tribal members agreed otherwise. In 1874, Colonel George Armstrong Custer

George Armstrong Custer (December 5, 1839 – June 25, 1876) was a United States Army officer and cavalry commander in the American Civil War and the American Indian Wars.

Custer graduated from West Point in 1861 at the bottom of his class, b ...

led a party into the Black Hills to investigate rumors of gold. Once he announced the discovery of gold on French Creek, the Black Hills Gold Rush

The Black Hills Gold Rush took place in Dakota Territory in the United States. It began in 1874 following the Custer Expedition and reached a peak in 1876–77.

Rumors and poorly documented reports of gold in the Black Hills go back to the early ...

brought prospectors into that area in violation of the Fort Laramie treaty. The Lakota protested in 1875 to no avail, as the United States demanded that the Lakota sell the Black Hills. The United States then declared the Lakota as hostile, which started the Black Hills War

The Great Sioux War of 1876, also known as the Black Hills War, was a series of battles and negotiations that occurred in 1876 and 1877 in an alliance of Lakota Sioux and Northern Cheyenne against the United States. The cause of the war was the ...

. The war included the Battle of the Rosebud, the Battle of the Little Bighorn

The Battle of the Little Bighorn, known to the Lakota and other Plains Indians as the Battle of the Greasy Grass, and also commonly referred to as Custer's Last Stand, was an armed engagement between combined forces of the Lakota Sioux, Nor ...

and the Battle of Slim Buttes, among others. The war ended in 1877. Crow Dog fought in this war, while the man he later killed, Spotted Tail, did not. Congress passed a law later in 1877 () that took the Black Hills away from the tribe, contrary to the language of the treaty.

Murder of Spotted Tail

On August 5, 1881, Crow Dog shot and killed Spotted Tail, who was the uncle of Oglala Lakota war leader Crazy Horse. Spotted Tail had not been selected as a chief by the tribe, but instead had been appointed by General George Crook in 1876, which hurt him in the view of many of the tribe. He was viewed as an accommodationist and the Bureau of Indian Affairs (BIA) referred to him as the "great peace chief." He also supervised the tribal police of about 300 men. In contrast, Crow Dog was a traditionalist and although he had been a captain in the tribal police, he was fired by Spotted Tail sometime after a July 4, 1881, confrontation during which Crow Dog pointed a rifle at Spotted Tail.

On August 5, tensions further escalated at a tribal meeting where a number of tribal members criticized Spotted Tail for taking Light-in-the-Lodge, the wife of Medicine Bear, a crippled man, into his household as his second wife. It was believed that the killing occurred that day as the result of Crow Dog and Spotted Tail meeting, both armed, and mistaking the other man's intentions. In another version of the story, Crow Dog was appointed by the tribal council to head the tribal police, which undermined the authority of Spotted Tail. Crow Dog discovered that Spotted Tail was taking money from ranchers for "grazing rights" and he denounced him for it, while Spotted Tail defended the practice. A later conflict with the Indian agent forced the tribal police to disband, and Crow Dog lost his position. This version makes no mention of another man's wife being the reason for the killing, and states that Crow Dog ambushed Spotted Tail to gain power in the tribe. There is no consensus among historians as to which events happened as described.

In either case, the matter was settled within the tribe, following longstanding tribal custom, by Crow Dog making a

On August 5, 1881, Crow Dog shot and killed Spotted Tail, who was the uncle of Oglala Lakota war leader Crazy Horse. Spotted Tail had not been selected as a chief by the tribe, but instead had been appointed by General George Crook in 1876, which hurt him in the view of many of the tribe. He was viewed as an accommodationist and the Bureau of Indian Affairs (BIA) referred to him as the "great peace chief." He also supervised the tribal police of about 300 men. In contrast, Crow Dog was a traditionalist and although he had been a captain in the tribal police, he was fired by Spotted Tail sometime after a July 4, 1881, confrontation during which Crow Dog pointed a rifle at Spotted Tail.

On August 5, tensions further escalated at a tribal meeting where a number of tribal members criticized Spotted Tail for taking Light-in-the-Lodge, the wife of Medicine Bear, a crippled man, into his household as his second wife. It was believed that the killing occurred that day as the result of Crow Dog and Spotted Tail meeting, both armed, and mistaking the other man's intentions. In another version of the story, Crow Dog was appointed by the tribal council to head the tribal police, which undermined the authority of Spotted Tail. Crow Dog discovered that Spotted Tail was taking money from ranchers for "grazing rights" and he denounced him for it, while Spotted Tail defended the practice. A later conflict with the Indian agent forced the tribal police to disband, and Crow Dog lost his position. This version makes no mention of another man's wife being the reason for the killing, and states that Crow Dog ambushed Spotted Tail to gain power in the tribe. There is no consensus among historians as to which events happened as described.

In either case, the matter was settled within the tribe, following longstanding tribal custom, by Crow Dog making a restitution

The law of restitution is the law of gains-based recovery, in which a court orders the defendant to ''give up'' their gains to the claimant. It should be contrasted with the law of compensation, the law of loss-based recovery, in which a court ...

payment of $600, eight horses, and one blanket to Spotted Tail's family.

Trial

Following the killing and the settlement under tribal customs, the Indian agent had Crow Dog arrested and taken to Fort Niobrara, Nebraska. Within 20 days, the U.S. Attorney General and the Secretary of the Interior concluded that the Federal Enclave Act of 1854 as modified by the

Following the killing and the settlement under tribal customs, the Indian agent had Crow Dog arrested and taken to Fort Niobrara, Nebraska. Within 20 days, the U.S. Attorney General and the Secretary of the Interior concluded that the Federal Enclave Act of 1854 as modified by the Assimilative Crimes Act The Assimilative Crimes Act, , makes state law applicable to conduct occurring on lands reserved or acquired by the Federal government as provided in , when the act or omission is not made punishable by an enactment of Congress.

History

The first A ...

allowed the territorial death penalty to be applied to Crow Dog. In September 1881, Crow Dog was indicted by a federal grand jury for murder and manslaughter under the laws of the Dakota Territory

The Territory of Dakota was an organized incorporated territory of the United States that existed from March 2, 1861, until November 2, 1889, when the final extent of the reduced territory was split and admitted to the Union as the states of N ...

. In March 1882 the case was heard by Judge Gideon C. Moody

Gideon Curtis Moody (October 16, 1832March 17, 1904) was an attorney and politician, elected in 1889 as a Republican United States Senator from South Dakota. He served two years. He also had served five years as an associate justice of the Dakota ...

at the First Judicial District Court of Dakota, located in Deadwood, South Dakota. The court appointed A. J. Plowman to represent Crow Dog, who claimed that he had been punished and made reparations according to the customs of the Brulé Sioux tribe. According to a contemporary news report of the Deadwood Times it was the first time "in the history of the country, hat

A hat is a head covering which is worn for various reasons, including protection against weather conditions, ceremonial reasons such as university graduation, religious reasons, safety, or as a fashion accessory. Hats which incorporate mecha ...

/nowiki> an Indian is held for trial for the murder of another Indian." The trial was viewed at the time as a sham, and despite testimonies from Indian witnesses stating that Spotted Tail had killed a rival once before, that Spotted Tail drew a pistol on Crow Dog, and that Spotted Tail's intention was to kill Crow Dog, Crow Dog was convicted and sentenced to be hanged on May 11, 1882. The prosecution had presented five Indian witnesses who stated that Spotted Tail was ambushed, and some witnesses stated he was unarmed. In an unusual move for a death penalty case, Moody released Crow Dog, allowing him to go home pending his appeal to the territorial Supreme Court. Surprising many of the white citizens of the area, Crow Dog returned to court as required. In May 1882, the territorial Supreme Court affirmed the conviction, and the execution was rescheduled for May 11, 1883. Crow Dog then petitioned the United States Supreme Court

The Supreme Court of the United States (SCOTUS) is the highest court in the federal judiciary of the United States. It has ultimate appellate jurisdiction over all U.S. federal court cases, and over state court cases that involve a point o ...

for a writ of ''habeas corpus

''Habeas corpus'' (; from Medieval Latin, ) is a recourse in law through which a person can report an unlawful detention or imprisonment to a court and request that the court order the custodian of the person, usually a prison official, t ...

'' and the Supreme Court accepted the case.

Opinion of the Court

Justice

Justice Stanley Matthews

Sir Stanley Matthews, CBE (1 February 1915 – 23 February 2000) was an English footballer who played as an outside right. Often regarded as one of the greatest players of the British game, he is the only player to have been knighted while sti ...

delivered the opinion of the unanimous court. Matthews noted that Crow Dog was indicted for murder under a statute prohibiting murder on federal land. Matthews then looked at the federal laws dealing with Indians, including a statute that applied the prohibition on murder to Indian reservations and another covering exceptions to prosecution. The first statute prohibited murder on federal land, the second statute applied the first statute to reservations, and the last had specific exceptions to prosecution. Matthews felt that this last section was the most critical one in the case, with the section stating unequivocally that federal law: "shall not be construed to extend to It tries them, not by their peers, nor by the customs of their people, nor the law of their land, but by superiors of a different race, according to the law of a social state of which they have an imperfect conception, and which is opposed to the traditions of their history, to the habits of their lives, to the strongest prejudices of their savage nature; one which measures the red man's revenge by the maxims of the white man's morality.As a result, the Court concluded, the First Judicial District Court of Dakota was without jurisdiction to hear the case. The writ of ''habeas corpus'' was issued, discharging Crow Dog from federal custody.

Subsequent developments

Major Crimes Act of 1885

Shocked by the Supreme Court's decision and under strong pressure from the BIA, Congress passed theMajor Crimes Act

The Major Crimes Act (U.S. Statutes at Large, 23:385)assimilate Indians into mainstream white society wanted to do away with the "heathen" tribal laws and apply white laws to the tribes. The BIA had also been attempting since 1874 to extend federal jurisdiction over major crimes to reservations, without any success. Beginning in 1882, the Indian Rights Association (IRA) also tried to extend federal jurisdiction, but in a different manner. The IRA believed that the tribes would be better served by a completely separate court system, modeled after U.S. courts and called agency courts. The only appeal would be to the Commissioner of Indian Affairs. The BIA opposed that approach, preferring to try only major crimes in the nearest federal court. ''

Ex parte

In law, ''ex parte'' () is a Latin term meaning literally "from/out of the party/faction of" (name of party/faction, often omitted), thus signifying "on behalf of (name)". An ''ex parte'' decision is one decided by a judge without requiring all ...

Crow Dog'' provided the BIA a perfect example of why this was needed, along with an incident involving Spotted Tail's son, Spotted Tail, Jr., in which the younger Spotted Tail participated in a fight during which three Brulé were killed. The younger Spotted Tail was also confined pending murder charges, and it took a direct order of the Secretary of the Interior for the local BIA agents to comply with the Supreme Court decision before he was released. The BIA also implemented regulations in 1883 criminalizing traditional tribal practices such as war dances and polygamy. Between the BIA's efforts and the IRA efforts, the law was passed in 1885, making seven offenses federal crimes. Many members of the Indian tribes were bitter with this outcome for decades afterwards. Wayne Ducheneaux, president of the National Congress of American Indians

The National Congress of American Indians (NCAI) is an American Indian and Alaska Native rights organization. It was founded in 1944 to represent the tribes and resist federal government pressure for termination of tribal rights and assimilati ...

, testified before Congress on the matter in 1968:

Before all this came about we had our own method of dealing with law-breakers and in settling disputes between members. That all changed when Crow Dog killed Spotted Tail. Of course, our method of dealing with that was Crow Dog should go take care of Spotted Tail's family, and if he didn't do that we'd banish him from the tribe. But that was considered too barbaric, and thought perhaps we should hang him like civilized people do, so they passed the Major Crimes Act that said we don't know how to handle murderers and they were going to show us.In 2000, Larry Echo Hawk, a

Pawnee Pawnee initially refers to a Native American people and its language:

* Pawnee people

* Pawnee language

Pawnee is also the name of several places in the United States:

* Pawnee, Illinois

* Pawnee, Kansas

* Pawnee, Missouri

* Pawnee City, Nebraska ...

who had been the Attorney General of Idaho

Idaho ( ) is a state in the Pacific Northwest region of the Western United States. To the north, it shares a small portion of the Canada–United States border with the province of British Columbia. It borders the states of Montana and Wyomi ...

and was later the Assistant Secretary of the Interior for Indian Affairs, noted that: "The Major Crimes Act was designed to give the federal government authority to criminally prosecute seven specific major crimes committed by Indians in Indian Country. It was a direct assault on the sovereign authority of tribal government over tribal members."

Tribal sovereignty

''Crow Dog'' had a tremendous impact on tribal sovereignty. The decision recognized two distinct concepts in addition to those related to criminal law. First, Justice Matthews had noted that under ''Cherokee Nation v. Georgia

''Cherokee Nation v. Georgia'', 30 U.S. (5 Pet.) 1 (1831), was a United States Supreme Court case. The Cherokee Nation sought a federal injunction against laws passed by the U.S. state of Georgia depriving them of rights within its boundaries, but ...

'', (1831) the Brulé tribe had a right to its own law in Indian country. Part of this ruling was based on American constitutional tradition – at that time, not all Indians were U.S. citizens and according to Matthews did not have a "voice in the selection of representatives and the framing of the laws." The case held that Indian tribes retain sovereignty, and is still valid law. For example, '' United States v. Lara'', (2004) cited ''Crow Dog'' when holding that both a tribe and the federal government could prosecute Lara, as they were separate sovereigns. Subsequent cases have supported the concept "that tribal Indians living in Indian country are citizens of the United States first (under the plenary power

A plenary power or plenary authority is a complete and absolute power to take action on a particular issue, with no limitations. It is derived from the Latin term ''plenus'' ("full").

United States

In United States constitutional law, plenary p ...

doctrine), the tribes second, and the states third, and then only to the extent that Congress chooses."

Currently the tribes are authorized to operate their own courts, not as a right of tribal sovereignty, but under a federal law. As of 2007, about half of the federally recognized tribes have tribal courts. The power of these courts was limited to minor crimes with a maximum punishment of a $5,000 fine and imprisonment of no more than one year until the passage of the Tribal Law and Order Act of 2010. Under this new act, tribes may sentence offenders for up to three years per offense and a $15,000 fine. As a result of Crow Dog and ensuing legislation, jurisdiction in Indian country is complex, as shown by the following table:

Plenary power doctrine

The court also created the plenary power doctrine, holding that the federal court did not have jurisdiction because Congress had not passed a law giving jurisdiction to the federal courts or taking away the rights of the tribe. ''Crow Dog'' was the last in a line of sovereignty cases that began with ''Cherokee Nation''; the next major case, '' United States v. Kagama'' (1886), upheld the plenary power of Congress to enact the Major Crimes Act. The plenary power doctrine allowed Congress to enact any law that it wanted to pass, over the opposition of the tribe or tribes affected. Congress subsequently used this power to breach the Medicine Lodge Treaty with theKiowa

Kiowa () people are a Native American tribe and an indigenous people of the Great Plains of the United States. They migrated southward from western Montana into the Rocky Mountains in Colorado in the 17th and 18th centuries,Pritzker 326 and e ...

by reducing the size of the Kiowa reservation without their consent. The use of this power led to complaints of being subject to a lawmaking body without representation, especially prior to being granted U.S. citizenship in 1924.Jack Blair, ''Demanding a Voice in Our Own Best Interest: A Call for a Delegate of the Cherokee Nation to the United States House of Representatives'', (1996).

See also

* Criminal law in the Waite CourtNotes

References

External links

* * {{Native American rights 1883 in United States case law Criminal cases in the Waite Court Lakota leaders Native American history of South Dakota United States Native American case law United States Supreme Court cases United States Supreme Court cases of the Waite Court