Evelyn Wood (British Army officer) on:

[Wikipedia]

[Google]

[Amazon]

Like his near contemporary John French, Wood began his career in the Royal Navy, serving under his uncle Captain Frederick Mitchell on HMS ''Queen'', but

Like his near contemporary John French, Wood began his career in the Royal Navy, serving under his uncle Captain Frederick Mitchell on HMS ''Queen'', but  Invalided home with a letter of recommendation from Lord Raglan, written five days before the latter's death, Wood left the

Invalided home with a letter of recommendation from Lord Raglan, written five days before the latter's death, Wood left the

Wood was on the staff of Lieutenant-General Thesiger (who later became Lord Chelmsford), who was then in command of a column in Natal in the

Wood was on the staff of Lieutenant-General Thesiger (who later became Lord Chelmsford), who was then in command of a column in Natal in the

In 1886 Wood returned to Britain to take charge of Eastern Command at Colchester, effective 1 April 1886. In November 1888 the

In 1886 Wood returned to Britain to take charge of Eastern Command at Colchester, effective 1 April 1886. In November 1888 the

Wood handed over his command at Aldershot to the Duke of Connaught and saw staff service at the

Wood handed over his command at Aldershot to the Duke of Connaught and saw staff service at the

After retiring from active service in December 1904, Wood lived at Upminster in

After retiring from active service in December 1904, Wood lived at Upminster in

The Crimea in 1854, and 1894

' (1895) *

Cavalry in the Waterloo Campaign

' (1895) *

Achievements of Cavalry

' (1897) *''From Midshipman to Field Marshal'' (1906)

Vol.1

Vol. 2

*

The Revolt in Hindustan 1857–59

' (1908) *

Our Fighting Services and How They Made the Empire

' (1916) (also known as ''British Battles on Land and Sea'') *

Winnowed Memories

' (1917)

''(Hampshire)''

British Pathé">Funeral of Field Marshal Sir Evelyn Wood VC Pathé, British Pathé

news 1919* *

Works by Evelyn Wood

at Project Gutenberg , - , - , - , - , - , - {{DEFAULTSORT:Wood, Evelyn 1838 births 1919 deaths 13th Hussars officers 17th Lancers officers 73rd Regiment of Foot officers British Army personnel of the Anglo-Zulu War British Army personnel of the Mahdist War British Army recipients of the Victoria Cross British field marshals British military personnel of the First Boer War British military personnel of the Third Anglo-Ashanti War British recipients of the Victoria Cross Burials at Aldershot Military Cemetery Cameronians officers Constables of the Tower of London Fellows of the Royal Geographical Society Governors of Natal Indian Rebellion of 1857 recipients of the Victoria Cross Knights Grand Cross of the Order of St Michael and St George Knights Grand Cross of the Order of the Bath Recipients of the Legion of Honour People educated at Marlborough College People from Braintree District Royal Horse Guards officers Royal Navy officers Royal Navy personnel of the Crimean War Younger sons of baronets Military personnel from Essex

Field Marshal

Field marshal (or field-marshal, abbreviated as FM) is the most senior military rank, ordinarily senior to the general officer ranks. Usually, it is the highest rank in an army and as such few persons are appointed to it. It is considered as ...

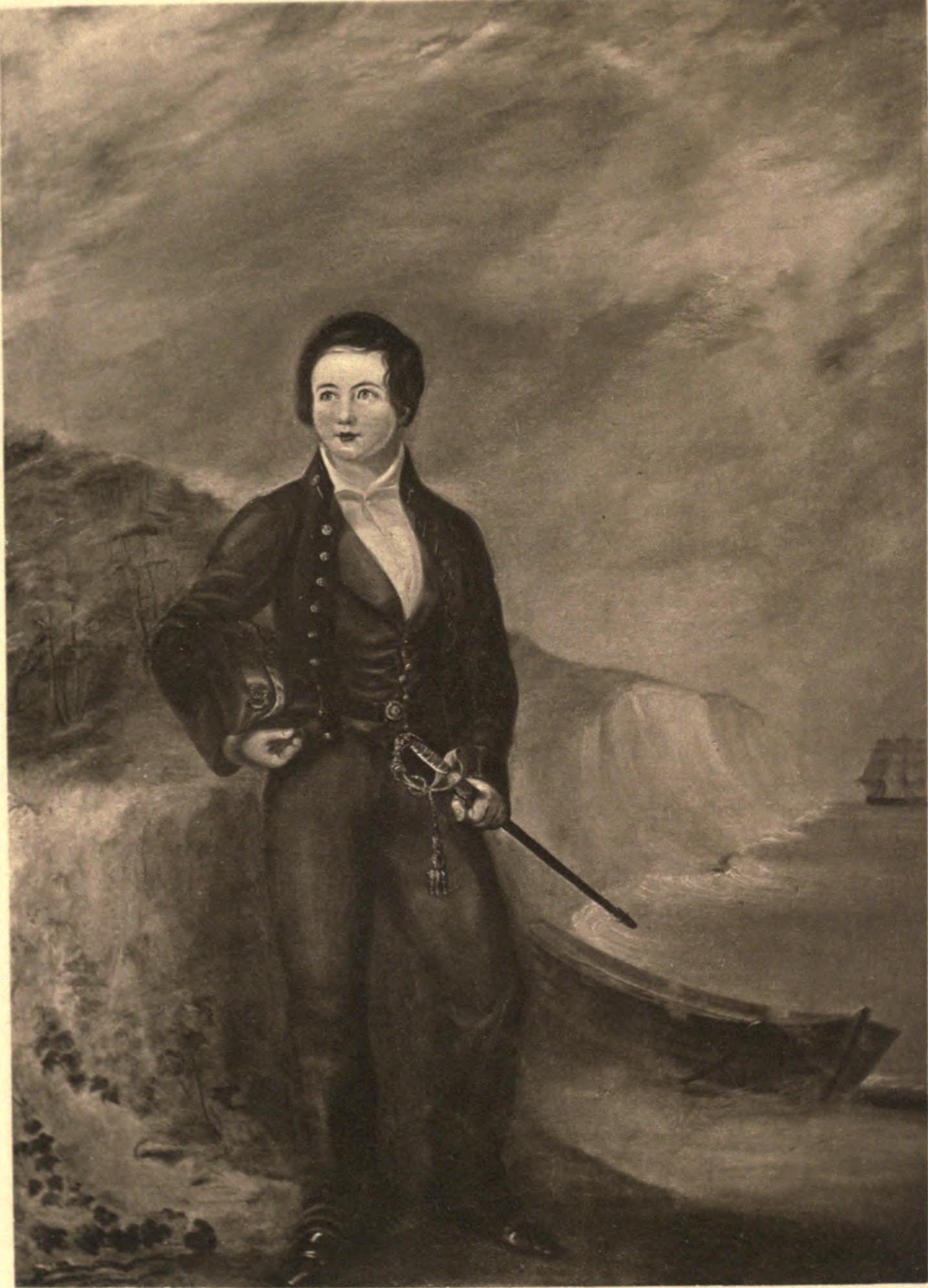

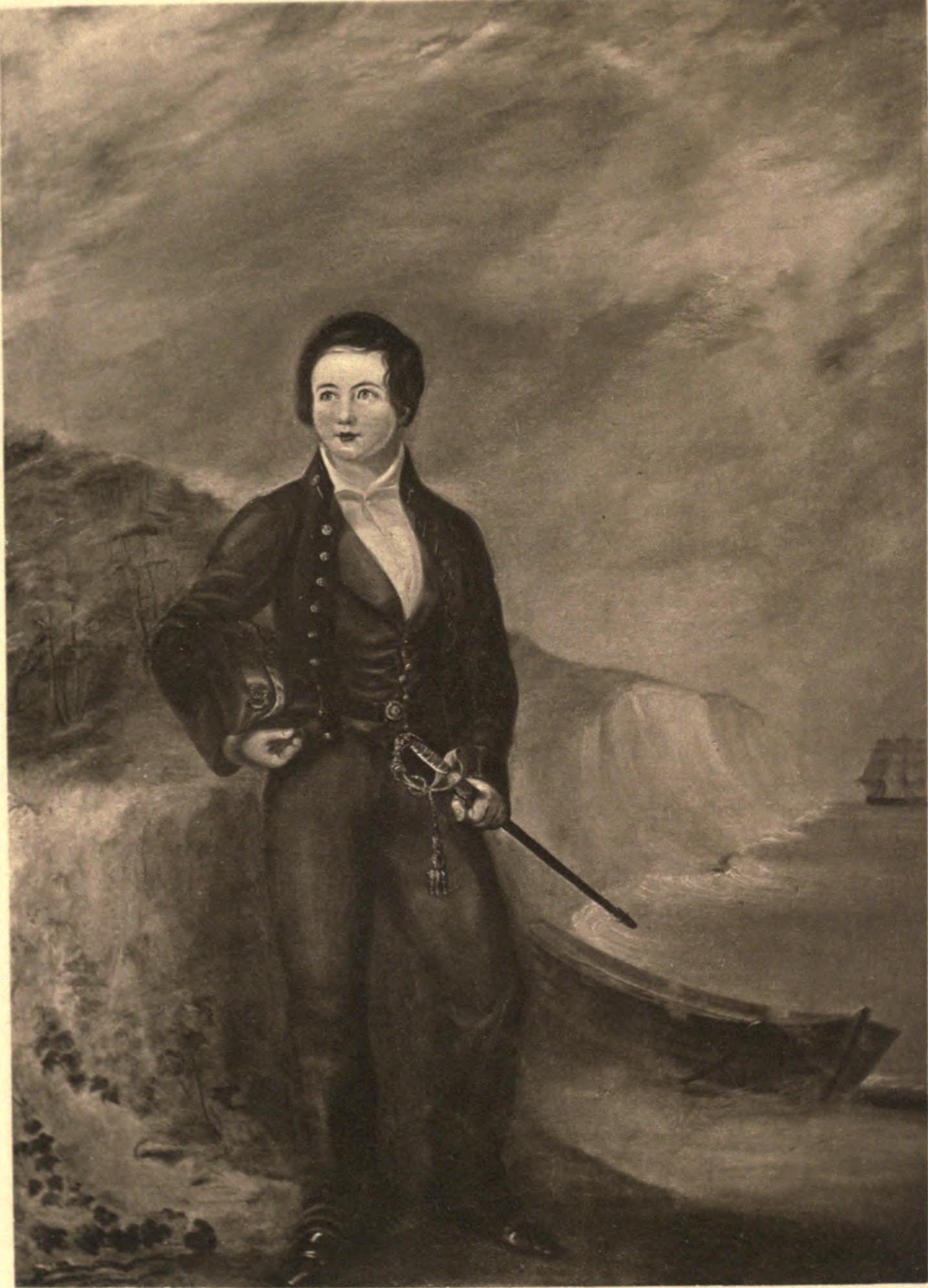

Sir Henry Evelyn Wood, (9 February 1838 – 2 December 1919) was a British Army

The British Army is the principal land warfare force of the United Kingdom, a part of the British Armed Forces along with the Royal Navy and the Royal Air Force. , the British Army comprises 79,380 regular full-time personnel, 4,090 Gurkha ...

officer. After an early career in the Royal Navy

The Royal Navy (RN) is the United Kingdom's naval warfare force. Although warships were used by English and Scottish kings from the early medieval period, the first major maritime engagements were fought in the Hundred Years' War against Fr ...

, Wood joined the British Army in 1855. He served in several major conflicts including the Indian Mutiny

The Indian Rebellion of 1857 was a major uprising in India in 1857–58 against the rule of the British East India Company, which functioned as a sovereign power on behalf of the British Crown. The rebellion began on 10 May 1857 in the for ...

where, as a lieutenant, he was awarded the Victoria Cross

The Victoria Cross (VC) is the highest and most prestigious award of the British honours system. It is awarded for valour "in the presence of the enemy" to members of the British Armed Forces and may be awarded posthumously. It was previousl ...

, the highest award for valour in the face of the enemy that is awarded to British and Imperial

Imperial is that which relates to an empire, emperor, or imperialism.

Imperial or The Imperial may also refer to:

Places

United States

* Imperial, California

* Imperial, Missouri

* Imperial, Nebraska

* Imperial, Pennsylvania

* Imperial, Texas

...

forces, for rescuing a local merchant from a band of robbers who had taken their captive into the jungle, where they intended to hang him. Wood further served as a commander in several other conflicts, notably the Third Anglo-Ashanti War, the Anglo-Zulu War

The Anglo-Zulu War was fought in 1879 between the British Empire and the Zulu Kingdom. Following the passing of the British North America Act of 1867 forming a federation in Canada, Lord Carnarvon thought that a similar political effort, cou ...

, the First Boer War and the Mahdist War

The Mahdist War ( ar, الثورة المهدية, ath-Thawra al-Mahdiyya; 1881–1899) was a war between the Mahdist Sudanese of the religious leader Muhammad Ahmad bin Abd Allah, who had proclaimed himself the "Mahdi" of Islam (the "Guided On ...

. His service in Egypt led to his appointment as Sirdar where he reorganised the Egyptian Army. He returned to Britain to serve as General Officer Commanding-in-Chief Aldershot Command from 1889, as Quartermaster-General to the Forces

The Quartermaster-General to the Forces (QMG) is a senior general in the British Army. The post has become symbolic: the Ministry of Defence organisation charts since 2011 have not used the term "Quartermaster-General to the Forces"; they simply ...

from 1893 and as Adjutant General

An adjutant general is a military chief administrative officer.

France

In Revolutionary France, the was a senior staff officer, effectively an assistant to a general officer. It was a special position for lieutenant-colonels and colonels in staf ...

from 1897. His last appointment was as commander of 2nd Army Corps (later renamed Southern Command) from 1901 to 1904.

Ancestry and early life

Wood was born at Cressing nearBraintree, Essex

Braintree is a town and former civil parish in Essex, England. The principal settlement of Braintree District, it is located northeast of Chelmsford and west of Colchester. According to the 2011 Census, the town had a population of 41,634, ...

as the fifth and youngest son of the Reverend Sir John Page Wood, 2nd Baronet (1796–1866),Heathcote 1999, p314 a clergyman,Reid 2006, p60-1 and Emma Caroline Michell, sister of Charles Collier Michell

Lieutenant-Colonel Charles Collier Michell, KH (29 March 1793 in Exeter – 28 March 1851 in Eltham, London), later known as Charles Cornwallis Michell, was a British soldier, first surveyor-general in the Cape, road engineer, architect, artist ...

and Admiral Frederick Thomas Michell, and daughter of Admiral Sampson Michell

Sampson Michell (1755–1809) was a British Royal Navy officer who left and became an Admiral and Commander of the Brazilian Navy.

Life

He was born in Truro in 1755 the son of Dr Thomas Michell MD (1726-1811) a "fox-hunting squire" in Cornw ...

. Wood was an elder brother of Katherine Parnell (Kitty O'Shea). Sir Matthew Wood, 1st Baronet

Sir Matthew Wood, 1st Baronet (2 June 1768 – 25 September 1843) was a British Whig politician and was Lord Mayor of London from 1815 to 1817.

Early life

Matthew Wood was the son of William Wood (died 1809), a serge maker from Exeter and Ti ...

, was his grandfather and Lord Chancellor

The lord chancellor, formally the lord high chancellor of Great Britain, is the highest-ranking traditional minister among the Great Officers of State in Scotland and England in the United Kingdom, nominally outranking the prime minister. Th ...

William Wood, 1st Baron Hatherley

William Page Wood, 1st Baron Hatherley, PC (29 November 1801 – 10 July 1881) was a British lawyer and statesman who served as a Liberal Lord High Chancellor of Great Britain between 1868 and 1872 in William Ewart Gladstone's first ministry ...

was an uncle. His maternal grandfather (Sampson Mitchell) had been an admiral in the Portuguese navy. One of his mother's brothers was a British admiral, another rose to be Surveyor-General of Cape Colony.Farwell 1985, p239-40 Wood was educated at Marlborough Grammar School (1847–9) and Marlborough College

( 1 Corinthians 3:6: God gives the increase)

, established =

, type = Public SchoolIndependent day and boarding

, religion = Church of England

, president = Nicholas Holtam

, head_label = Master

, head = Louis ...

(1849–52), but ran away after an unjust beating.

Early military career

Crimean War: from sailor to soldier

Like his near contemporary John French, Wood began his career in the Royal Navy, serving under his uncle Captain Frederick Mitchell on HMS ''Queen'', but

Like his near contemporary John French, Wood began his career in the Royal Navy, serving under his uncle Captain Frederick Mitchell on HMS ''Queen'', but vertigo

Vertigo is a condition where a person has the sensation of movement or of surrounding objects moving when they are not. Often it feels like a spinning or swaying movement. This may be associated with nausea, vomiting, sweating, or difficulties w ...

stopped him going aloft. He became a midshipman

A midshipman is an officer of the lowest rank, in the Royal Navy, United States Navy, and many Commonwealth navies. Commonwealth countries which use the rank include Canada (Naval Cadet), Australia, Bangladesh, Namibia, New Zealand, South Af ...

on 15 April 1852.

Wood served in the Crimean War

The Crimean War, , was fought from October 1853 to February 1856 between Russia and an ultimately victorious alliance of the Ottoman Empire, France, the United Kingdom and Piedmont-Sardinia.

Geopolitical causes of the war included the ...

during the siege of Sebastopol

A siege is a military blockade of a city, or fortress, with the intent of conquering by attrition, or a well-prepared assault. This derives from la, sedere, lit=to sit. Siege warfare is a form of constant, low-intensity conflict characteri ...

, in Captain

Captain is a title, an appellative for the commanding officer of a military unit; the supreme leader of a navy ship, merchant ship, aeroplane, spacecraft, or other vessel; or the commander of a port, fire or police department, election precinct, e ...

William Peel's 1,400 strong naval brigade, whose job was to man some guns on a ridge opposite Sebastopol.Farwell 1985, p241-2 He was at Inkerman and aged 16, was Peel's aide de camp in the assault on the Redan

Redan (a French word for "projection", "salient") is a feature of fortifications. It is a work in a V-shaped salient angle towards an expected attack. It can be made from earthworks or other material.

The redan developed from the lunette, o ...

on 18 June 1855, having risen from his sickbed to join the attack. He was seriously wounded and almost lost his left arm, which doctors wanted to amputate. Wood was mentioned in despatches

To be mentioned in dispatches (or despatches, MiD) describes a member of the armed forces whose name appears in an official report written by a superior officer and sent to the high command, in which their gallant or meritorious action in the face ...

and received his first, but unsuccessful, recommendation for a VC.

Invalided home with a letter of recommendation from Lord Raglan, written five days before the latter's death, Wood left the

Invalided home with a letter of recommendation from Lord Raglan, written five days before the latter's death, Wood left the Royal Navy

The Royal Navy (RN) is the United Kingdom's naval warfare force. Although warships were used by English and Scottish kings from the early medieval period, the first major maritime engagements were fought in the Hundred Years' War against Fr ...

to join the British Army

The British Army is the principal land warfare force of the United Kingdom, a part of the British Armed Forces along with the Royal Navy and the Royal Air Force. , the British Army comprises 79,380 regular full-time personnel, 4,090 Gurkha ...

, becoming a cornet

The cornet (, ) is a brass instrument similar to the trumpet but distinguished from it by its conical bore, more compact shape, and mellower tone quality. The most common cornet is a transposing instrument in B, though there is also a so ...

( without purchase) in the 13th Light Dragoons on 7 September 1855 and reporting to their depot with his arm still in a sling. He had only £250 () a year in private income, rather than the £400 () needed, and was soon in debt.

Wood returned to the Crimean Theatre (January 1856). His promotion to lieutenant

A lieutenant ( , ; abbreviated Lt., Lt, LT, Lieut and similar) is a commissioned officer rank in the armed forces of many nations.

The meaning of lieutenant differs in different militaries (see comparative military ranks), but it is often ...

, which his uncle had paid for, took effect on 1 February 1856.Farwell 1985, p243 However, within a month he was in hospital at Scutari with pneumonia and typhoid. His parents were told he was dying, so his mother arrived on 20 March 1856 only to find one of Florence Nightingale

Florence Nightingale (; 12 May 1820 – 13 August 1910) was an English social reformer, statistician and the founder of modern nursing. Nightingale came to prominence while serving as a manager and trainer of nurses during the Crimean War ...

's nurses striking him. He was so emaciated that his hip bones were poking through his skin. Against medical advice he was brought home to England to recover.

Indian Mutiny

Wood served in Ireland then transferred as a lieutenant to the 17th Lancers on 9 October 1857. His transfer was to gain passage to India; he had considered joining theFrench Foreign Legion

The French Foreign Legion (french: Légion étrangère) is a corps of the French Army which comprises several specialties: infantry, cavalry, engineers, airborne troops. It was created in 1831 to allow foreign nationals into the French Army ...

. He reached Bombay on 21 December 1858. While out hunting he was attacked by a wounded tiger – it was shot in the nick of time by a hunting companion; – he also rode a giraffe belonging to a friendly Indian prince to win a bet with a brother officer – he stayed on long enough to win the bet, but was trampled badly, the animal's rear hoof breaking through both cheeks, crushing his nose.Farwell 1985, p245-6

In India

India, officially the Republic of India (Hindi: ), is a country in South Asia. It is the List of countries and dependencies by area, seventh-largest country by area, the List of countries and dependencies by population, second-most populous ...

, Wood saw action at Rajghur, Sindwaho, Kharee, and Barode during the Indian Mutiny

The Indian Rebellion of 1857 was a major uprising in India in 1857–58 against the rule of the British East India Company, which functioned as a sovereign power on behalf of the British Crown. The rebellion began on 10 May 1857 in the for ...

. From May 1858 to October 1859 he was brigade major to a flying column in Central India. On 19 October 1858 during an action at Sindwaho while in command of a troop of light cavalry

Light cavalry comprised lightly armed and armored cavalry troops mounted on fast horses, as opposed to heavy cavalry, where the mounted riders (and sometimes the warhorses) were heavily armored. The purpose of light cavalry was primarily ...

, twenty-year-old Lieutenant Wood attacked a body of rebels, whom he routed almost single-handedly. Wood also saw action at Kurai (25 October 1859). At Sindhora, on 29 December 1858, Wood's force of 10 men routed 80 men. With the help of a ''daffadar

Daffadar ( Hindustani: दफ़ादार ( Devanagari) ; ( Nastaliq)) is the equivalent rank to sergeant in the Indian and Pakistani cavalry, as it was formerly in the British Indian Army. The rank below is lance daffadar. The equivalent in ...

'' and a '' sowar'', he rescued a local Potail (headman of a village) from a band of robbers who had taken their captive into the jungle, where they had intended to hang him. For these two acts of selfless bravery, Wood was awarded the Victoria Cross.

His citation read:

He became temporarily deaf for a week whilst studying Hindustani at Poona, which he attributed at the time to overwork. In December 1859 he joined the 2nd Central India Horse, whose main function was the suppression of banditry

Banditry is a type of organized crime committed by outlaws typically involving the threat or use of violence. A person who engages in banditry is known as a bandit and primarily commits crimes such as extortion, robbery, and murder, either as an ...

. In this role he had to deal with an incipient mutiny and sort out the regimental accounts. He was invalided back to Britain in November 1860 with fever, sunstroke and ear problems.Heathcote 1999, p315

Staff College

On 16 April 1861, Wood was promoted tocaptain

Captain is a title, an appellative for the commanding officer of a military unit; the supreme leader of a navy ship, merchant ship, aeroplane, spacecraft, or other vessel; or the commander of a port, fire or police department, election precinct, e ...

. His captaincy cost him £1,000 official payment to the government and £1,500 "over regulation" to buy out his predecessor.Farwell 1985, p246 He was promoted again this time to brevet major (for services in India) on 19 August 1862.

Wood passed the exam to enter the new Staff College, Camberley

Staff College, Camberley, Surrey, was a staff college for the British Army and the presidency armies of British India (later merged to form the Indian Army). It had its origins in the Royal Military College, High Wycombe, founded in 1799, whic ...

, but another officer from 17th Lancers had higher marks and as at that time only one officer was permitted from each regiment each year, Wood had to transfer as a captain to the 73rd (Perthshire) Regiment of Foot on 21 October 1862. He took up his place in January 1863, and graduated in 1864. Whilst at Staff College he took part in boxing lessons.

In Dublin, from January 1865 to March 1866 he was aide-de-camp to General William Napier, whom he knew from India; the damp climate brought on a recurrence of fever and ear trouble. In the autumn of 1865 the 73rd were ordered to Hong Kong, but Wood disliked the new commanding officer so much that he paid £500 to transfer into the 17th (Leicestershire) Regiment of Foot.

From July 1866 to November 1871 he was at North Camp at Aldershot, first as brigade major then as Deputy Assistant Quartermaster-General. Having just written to propose to his future wife, he read in 1867 that "General Napier" was to lead an expedition to Abyssinia; he packed his bags and went to London to volunteer, but then learnt that this was not to be William Napier, but General Robert Napier, whom he did not know and who was unlikely to grant him a staff position.Farwell 1985, p247 With a young family to support but not hopeful of getting a staff position, Wood also studied law, enrolling at the Middle Temple

The Honourable Society of the Middle Temple, commonly known simply as Middle Temple, is one of the four Inns of Court exclusively entitled to call their members to the English Bar as barristers, the others being the Inner Temple, Gray's I ...

on 30 April 1870.

On 22 June 1870 Wood was given an unattached majority. In the summer of 1871 he paid £2,000 () to purchase a permanent majority in the 90th Light Infantry, effective 28 October 1871 and one of the last such transactions before the purchase of commissions system was abolished.

Nursing his children through diphtheria (he had sent his pregnant wife away), he was prescribed morphine for insomnia and nearly died of an overdose.Farwell 1985, p248 Wood was promoted to brevet lieutenant colonel

Lieutenant colonel ( , ) is a rank of commissioned officers in the armies, most marine forces and some air forces of the world, above a major and below a colonel. Several police forces in the United States use the rank of lieutenant colon ...

on 19 June 1873 on the basis of seniority from the purchase of his majority.

Imperial wars

Third Ashanti War

In May 1873, with the Third Anglo-Ashanti War brewing, he met Wolseley by chance in the War Office and joked that his naval experience might come in handy for West African waterways. On 12 September 1873 he was appointed to Wolseley's staff for special services. He commanded a flank at the Battle of Amoaful (31 January 1874) where he was wounded. and at the Battle of Esaman. He helped recruit a regiment from among the coastal African tribes, although he wrote of the Fantis that "it would be difficult to imagine a more cowardly, useless lot of men". He did, however, discourage British officers from using physical abuse on them.Farwell 1985, p249 He was wounded just above the heart, confining him to a stretcher for a day. Relying onchlorodyne

Chlorodyne was one of the best known patent medicines sold in the British Isles. It was invented in the 19th century by a Dr. John Collis Browne, a doctor in the British Indian Army; its original purpose was in the treatment of cholera. Browne ...

and laudanum

Laudanum is a tincture of opium containing approximately 10% powdered opium by weight (the equivalent of 1% morphine). Laudanum is prepared by dissolving extracts from the opium poppy (''Papaver somniferum Linnaeus'') in alcohol (ethanol).

R ...

to keep going, he was ordered to lead the sick and wounded back to the coast. It was erroneously reported in the London press that he had been captured and probably flayed alive. He was appointed a Companion of the Order of the Bath

Companion may refer to:

Relationships Currently

* Any of several interpersonal relationships such as friend or acquaintance

* A domestic partner, akin to a spouse

* Sober companion, an addiction treatment coach

* Companion (caregiving), a caregiv ...

(CB) on 31 March 1874.

Wood presented two African chieftains with a walking stick, a hat and an umbrella. Twenty-two years later, later his eldest son was also in Ashanti. While there, he saw a native carrying a stick which the man would not sell, saying it belonged to his chief. On closer inspection, Wood Junior read an inscription; 'Presented to Chief Andoo by Colonel Evelyn Wood, 1874.' He was promoted in permanent rank from major and brevet lieutenant-colonel to brevet colonel

Colonel (abbreviated as Col., Col or COL) is a senior military officer rank used in many countries. It is also used in some police forces and paramilitary organizations.

In the 17th, 18th and 19th centuries, a colonel was typically in charge ...

on 1 April 1874. A man of relatively modest means for much of his life, Wood took his profession very seriously – like many who had served under Garnet Wolseley in the Ashanti War he was a member of the reforming "Wolseley ring The Wolseley ring was a group of 19th century British army officers loyal to Garnet Wolseley and considered by him to be clever, brave, experienced and hard-working.

After the Crimean War Wolseley started to keep a note of the best officers he met ...

", although the two men were never on particularly good terms.

Wood completed his legal studies and was called to the Bar

The call to the bar is a legal term of art in most common law jurisdictions where persons must be qualified to be allowed to argue in court on behalf of another party and are then said to have been "called to the bar" or to have received "call to ...

at the Middle Temple

The Honourable Society of the Middle Temple, commonly known simply as Middle Temple, is one of the four Inns of Court exclusively entitled to call their members to the English Bar as barristers, the others being the Inner Temple, Gray's I ...

on 30 April 1874. In June 1874 he lectured about the Ashanti War at the Royal United Services Institute

The Royal United Services Institute (RUSI, Rusi), registered as Royal United Service Institute for Defence and Security Studies and formerly the Royal United Services Institute for Defence Studies, is a British defence and security think tank ...

. From September 1874 to February 1878 he was at Aldershot, first as Superintendent of Garrison Instruction, then as Assistant Quartermaster-General. In 1877 he declined command of Staff College, recommending George Colley

George Colley (18 October 1925 – 17 September 1983) was an Irish Fianna Fáil politician who served as Tánaiste from 1977 to 1981, Minister for Energy from 1980 to 1981, Minister for Tourism and Transport from 1979 to 1980, Minister for ...

, who also declined.

Zulu War

Wood was on the staff of Lieutenant-General Thesiger (who later became Lord Chelmsford), who was then in command of a column in Natal in the

Wood was on the staff of Lieutenant-General Thesiger (who later became Lord Chelmsford), who was then in command of a column in Natal in the Xhosa Wars

The Xhosa Wars (also known as the Cape Frontier Wars or the Kaffir Wars) were a series of nine wars (from 1779 to 1879) between the Xhosa Kingdom and the British Empire as well as Trekboers in what is now the Eastern Cape in South Africa. T ...

(also known as the Cape Frontier Wars). He was employed as a field officer of the 90th Light Infantry, which had arrived in South Africa in January 1878, in the last battle of the wars at Tutu Bush (May 1878).Farwell 1985, p250-1 On 13 November he was promoted to the substantive rank of lieutenant-colonel, and on the same day he was appointed commanding officer of the 90th Light.

In January 1879, Wood took part in the Anglo-Zulu War

The Anglo-Zulu War was fought in 1879 between the British Empire and the Zulu Kingdom. Following the passing of the British North America Act of 1867 forming a federation in Canada, Lord Carnarvon thought that a similar political effort, cou ...

and was given command of the 3,000-strong 4th column on the left flank of the army when they crossed the Zulu frontier. Defeat of other British forces at Isandlwana (22 January) would force Wood to retreat to fortified positions at Kambula.Manning 2007, p111 The right-wing column was besieged by the Zulus at Eshowe, leaving Wood's the only free column. Wood and Redvers Buller harassed the Zulus of the local Qulusi Clan, so the main Zulu army was diverted to fight them. Wood was defeated at Hlobane on 28 March 1879, where he had his horse shot from under him and his close friend and chief staff officer Ronald Campbell was killed. He recovered and the following day decisively beat the Zulus at Kambula (29 March 1879). He was promoted to the local rank of brigadier-general on 3 April. Wood's victory was the turning point of the war, and in May 1879, during the second invasion of Zululand, his force linked with the 2nd Division for a push on Ulundi.

At the end of the war, Wood headed the negotiations which took place on Conference Hill. The Zulus squatted round the negotiating tent in a large crescent. According to one witness, they were 'apathetic'. The tension rose when Wood emerged from the tent and ordered his band to play ' God Save the Queen'. The accompanying soldiers gave good cheer; the bandmaster was then told to play something lively. Being Irish, the master 'treated them to 'Patrick's Day in the Morning'. The effect was magical; one after another, the Zulus rose and, swaying and dancing, swarmed around the British soldiers on their horses. Of particular interest to the Zulus was the bass drummer whom they seemed to greatly admire. Their negotiations were successful. Wood and Buller both chose to return to England rather than join Wolseley in the final pursuit of the Zulu King Cetewayo. Reverting to his permanent rank of brevet colonel, Wood was also advanced to Knight Commander of the Order of the Bath

The Most Honourable Order of the Bath is a British order of chivalry founded by George I of Great Britain, George I on 18 May 1725. The name derives from the elaborate medieval ceremony for appointing a knight, which involved Bathing#Medieval ...

(KCB) on 23 June 1879.

He visited Balmoral Castle

Balmoral Castle () is a large estate house in Aberdeenshire, Scotland, and a residence of the British royal family. It is near the village of Crathie, west of Ballater and west of Aberdeen.

The estate and its original castle were bought f ...

in September 1879, and in subsequent years wrote the Queen letters described by Ian Beckett as "extraordinarily sycophantic". He was already very deaf and hardly stopped talking; the Queen herself recorded that she "hollered at him", whilst in the field an officer had to accompany him at night as he might not hear a sentry's challenge; his deafness came partly from his various fevers. He was also a hypochondriac, and very vain – he is said to have had his medal ribbons bordered in black so that they would be more visible.

Wood was paid £100 for a series of London newspaper articles, his first published work. He was disappointed not to be made a major-general, despite lobbying by the Queen and Wolseley. This may well have been deliberate blocking of Wolseley's proteges from promotion by the Duke of Cambridge

Duke of Cambridge, one of several current royal dukedoms in the United Kingdom , is a hereditary title of specific rank of nobility in the British royal family. The title (named after the city of Cambridge in England) is heritable by male de ...

. Wood recommended Redvers Buller for his VC after the Zulu War. On 15 December 1879 Wood took up a brigade command at Belfast, and in that role was again given the local rank of brigadier-general

Brigadier general or Brigade general is a military rank used in many countries. It is the lowest ranking general officer in some countries. The rank is usually above a colonel, and below a major general or divisional general. When appointed t ...

, this time on the staff in Ireland

Ireland ( ; ga, Éire ; Ulster-Scots: ) is an island in the North Atlantic Ocean, in north-western Europe. It is separated from Great Britain to its east by the North Channel, the Irish Sea, and St George's Channel. Ireland is the s ...

in December 1879.

First Boer War

On 12 January 1880 Wood was posted to command the Chatham Garrison, roughly equivalent to a brigade, holding that post until early 1881. He was again ranked from January 1880 as a local brigadier-general. Wood's brother stood for Parliament as an "advanced" Liberal in April 1880, but he himself declined approaches to do so at least twice. Between March and July 1880 Wood and his wife were obliged by the Queen to escort the formerEmpress Eugenie

An emperor (from la, imperator, via fro, empereor) is a monarch, and usually the sovereign ruler of an empire or another type of imperial realm. Empress, the female equivalent, may indicate an emperor's wife ( empress consort), mother (empr ...

to see the spot where her son, the Prince Imperial, had been killed whilst fighting with the British Army in the Zulu War, calling at St Helena

Saint Helena () is a British overseas territory located in the South Atlantic Ocean. It is a remote volcanic tropical island west of the coast of south-western Africa, and east of Rio de Janeiro in South America. It is one of three constitu ...

(where Napoleon I

Napoleon Bonaparte ; it, Napoleone Bonaparte, ; co, Napulione Buonaparte. (born Napoleone Buonaparte; 15 August 1769 – 5 May 1821), later known by his regnal name Napoleon I, was a French military commander and political leader wh ...

had died) on the way back. To his annoyance he received no pay whatsoever for this mission, despite it being official business at the Queen's request. In October 1880 Wolseley complained of the noise, poor food and filth of Wood's home.

With the First Boer War reaching a crescendo, he was once again sent back to South Africa in January 1881, initially as a "staff colonel" to Sir George Colley

Major General Sir George Pomeroy Colley, (1 November 1835 – 27 February 1881) was a British Army officer who became Governor and Commander-in-Chief of Natal and High Commissioner for South Eastern Africa. Colley was killed in action, at the ...

, Governor and Commander-in-Chief in Natal, who was his junior on the Army list. He was then, again with the local rank of brigadier-general, appointed second-in-command, pushing reinforcements up to Colley. He succeeded Colley after his defeat and death at Majuba Hill

The Battle of Majuba Hill on 27 February 1881 was the final and decisive battle of the First Boer War that was a resounding victory for the Boers. The British Major General Sir George Pomeroy Colley occupied the summit of the hill on the night ...

(27 February 1881),Heathcote 1999, p316 earning promotion to the local rank of major-general

Major general (abbreviated MG, maj. gen. and similar) is a military rank used in many countries. It is derived from the older rank of sergeant major general. The disappearance of the "sergeant" in the title explains the apparent confusion of a ...

.

In mid-March Wood reopened the offensive. He intended to relieve the towns under siege, but was ordered by William Gladstone

William Ewart Gladstone ( ; 29 December 1809 – 19 May 1898) was a British statesman and Liberal politician. In a career lasting over 60 years, he served for 12 years as Prime Minister of the United Kingdom, spread over four non-conse ...

's Cabinet to make peace.Farwell 1985, p251-2 Wood wrote to his wife that the treaty would make him "the best abused man in England for a time" but thought it his duty to obey the government's orders. Wolseley (who thought the treaty "infamous" and "ignominious") and other officers thought he should have resigned his commission rather than sign it. Wolseley never forgave him for not avenging Colley, and he was criticised by Colley's biographer William Butler. He had to travel to Pretoria, and was injured on the way when the horses of his carriage bolted. He negotiated peace on 21 March 1881. He was offered but declined, the Governorship of Natal. In April 1881 he was appointed to a commission of inquiry into all matters relating to the future settlement of the Transvaal Territory, and put in a dissenting opinion about the boundaries.

Although the peace negotiations were an embarrassing reverse for Britain, they brought Wood further political and royal favour. The Queen thought highly of him (and Buller).Farwell 1985, p257 Wood's third daughter, born in 1881, was named "Victoria Eugenie" at the Queen's wish. Wood had already impressed Lord Beaconsfield

Benjamin Disraeli, 1st Earl of Beaconsfield, (21 December 1804 – 19 April 1881) was a British statesman and Conservative Party (UK), Conservative politician who twice served as Prime Minister of the United Kingdom. He played a centr ...

(Prime Minister at the time), who had met him at the Queen's suggestion after the Zulu War, and now impressed Gladstone, the current Prime Minister.Farwell 1985, p257 He was promoted in permanent rank from lieutenant-colonel (unemployed) and brevet colonel to major-general (30 November 1881) and was awarded a Knight Grand Cross of the Order of St Michael and St George

The Most Distinguished Order of Saint Michael and Saint George is a British order of chivalry founded on 28 April 1818 by George IV, Prince of Wales, while he was acting as prince regent for his father, King George III.

It is named in honour ...

(GCMG) on 17 February 1882. He returned to England and to the Chatham command in February 1882.

Egypt and Sudan

In August 1882 Wood commanded the 4th Brigade on the Egyptian expedition to suppress the Urabi Revolt. Wolseley kept him on occupation duties in Alexandria, so he missed theBattle of Tel el-Kebir

The Battle of Tel El Kebir (often spelled Tel-El-Kebir) was fought on 13 September 1882 at Tell El Kebir in Egypt

Egypt ( ar, مصر , ), officially the Arab Republic of Egypt, is a List of transcontinental countries, transcontinental cou ...

.Farwell 1985, p253-4 He returned to Chatham for a while again in November 1882 then returned to be Sirdar (commander) of the Egyptian Army from 21 December 1882 until 1885, during which period he thoroughly reorganised it, with Francis Grenfell and Kitchener working under him. He had 25 British officers (who were given extra pay and Egyptian ranks a grade or two higher than their British ones) and a few NCOs, although to Wood's annoyance Lt-Gen Stephenson, commander of the British occupation forces, was confirmed as his senior in June 1884. During the cholera epidemic of 1883, British officers earned the respect of Egyptian soldiers by nursing them. Wood gave Sundays off from drill as well as Fridays (the Muslim holy day), so that Egyptian soldiers would see that their British officers took their own religion seriously.

Wood hoped to command the Gordon Relief Expedition

The Nile Expedition, sometimes called the Gordon Relief Expedition (1884–85), was a British mission to relieve Major-General Charles George Gordon at Khartoum, Sudan. Gordon had been sent to the Sudan to help Egyptians evacuate from Sudan ...

(see Mahdist War

The Mahdist War ( ar, الثورة المهدية, ath-Thawra al-Mahdiyya; 1881–1899) was a war between the Mahdist Sudanese of the religious leader Muhammad Ahmad bin Abd Allah, who had proclaimed himself the "Mahdi" of Islam (the "Guided On ...

), but Wolseley was given the job instead in September 1884 and sidelined him to command of the lines of communication. Wood also fell out with Earle, the commander of the river column. He commanded the British at the Battle of Ginnis

The Battle of Ginnis (also known as the Battle of Gennis) was a minor battle of the Mahdist War that was fought on December 30, 1885, between soldiers of the Anglo-Egyptian Army and Mahdist Sudanese warriors of the Dervish State. The battle was c ...

in December 1885. He was the only officer to be given an important command despite advising against Wolseley's choice of the Nile route. Wood briefly took Redvers Buller's place as chief of staff as Buller had to take charge of the desert column after Stewart was mortally wounded at Abu Klea. In this job Wood became unpopular for employing female nurses (against the advice of army doctors at that time) and quarrelled with his friend Buller when Wood recommended a more cautious advance which would give time to build up supply depots. He was disorganised, stuffing telegrams into his pocket, to Wolseley's annoyance. In March 1885 Buller became chief of staff again.

By this stage Wood was so deaf that Wolseley complained he had become hoarse from shouting at him. Wolseley wrote of Wood that "he has done worse than I expected" and in his journal described him as "the vainest but by no means the ablest of men. He is as cunning as a first class female diplomatist … (but has not) real sound judgement…… intrigues with newspaper correspondents … he has not the brains nor the disposition nor the coolness nor the firmness of purpose to enable him to take command in any war … a very second rate general … whose two most remarkable traits (a)re extreme vanity & unbounded self-seeking" although a letter to his wife (complaining that Wood was "a very puzzle-headed fellow", wanting in method and vain) suggests that Wolseley still bore Wood a grudge about the peace after Majuba Hill. Ill once again, Wood handed over the job of Sirdar to Francis Grenfell. To his annoyance, he received no (British) honours from the Nile expedition. Wood returned to the UK in June 1885.

Home commands

Aldershot

In 1886 Wood returned to Britain to take charge of Eastern Command at Colchester, effective 1 April 1886. In November 1888 the

In 1886 Wood returned to Britain to take charge of Eastern Command at Colchester, effective 1 April 1886. In November 1888 the Duke of Cambridge

Duke of Cambridge, one of several current royal dukedoms in the United Kingdom , is a hereditary title of specific rank of nobility in the British royal family. The title (named after the city of Cambridge in England) is heritable by male de ...

( Commander-in-Chief of the Forces) opposed his mooted appointment as General Officer Commanding of Aldershot Command

Aldershot () is a town in Hampshire, England. It lies on heathland in the extreme northeast corner of the county, southwest of London. The area is administered by Rushmoor Borough Council. The town has a population of 37,131, while the Alders ...

, one of the most important posts in the army at home, as the Woods were "a very rough couple". Despite the Duke's opposition, he was appointed GOC Aldershot on 1 January 1889. He was promoted to local lieutenant-general

Lieutenant general (Lt Gen, LTG and similar) is a three-star military rank (NATO code OF-8) used in many countries. The rank traces its origins to the Middle Ages, where the title of lieutenant general was held by the second-in-command on the ...

, as he was only tenth on the list of major-generals. He was promoted to permanent lieutenant-general (1 April 1890) and advanced to Knight Grand Cross of the Order of the Bath

The Most Honourable Order of the Bath is a British order of chivalry founded by George I on 18 May 1725. The name derives from the elaborate medieval ceremony for appointing a knight, which involved bathing (as a symbol of purification) as one ...

(GCB) on 30 May 1891. He would remain at Aldershot until 8 October 1893.

At Aldershot

Aldershot () is a town in Hampshire, England. It lies on heathland in the extreme northeast corner of the county, southwest of London. The area is administered by Rushmoor Borough Council. The town has a population of 37,131, while the Alder ...

Wood supported the implementation of the Wantage Commission reforms to soldiers' conditions. He was concerned with the well-being of both troops and animals, recommending the rebuilding of barracks and training of army cooks. He arranged for sick men's food to be prepared in hospitals rather than brought in tins from their own units. He experimented with training soldiers on bicycles, night marches (in the teeth of opposition, particularly from the Duke of Cambridge

Duke of Cambridge, one of several current royal dukedoms in the United Kingdom , is a hereditary title of specific rank of nobility in the British royal family. The title (named after the city of Cambridge in England) is heritable by male de ...

, who thought it might interfere with horses' rest) and negotiated with the railway companies for cheap rail tickets for soldiers going on leave. He also carried out extensive training manoeuvres for the regulars under his command and for Militia

A militia () is generally an army or some other fighting organization of non-professional soldiers, citizens of a country, or subjects of a state, who may perform military service during a time of need, as opposed to a professional force of r ...

and Volunteer forces. He made contributions to a Baptist chapel for a time, and ensured that Baptist services were as well publicised as those of other denominations. With the help of some high-ranking Roman Catholic friends, he agreed on an ecumenical service for Irish regiments which was acceptable both to Roman Catholic soldiers and their Anglican officers and chaplains. He promoted the concept of mounted infantry and conducted training in cavalry marksmanship. In early 1892 an early cinema film was made to illustrate the life of a soldier.

While Wood was at Aldershot his aides-de-camp included Captain Edward Roderic 'Roddy' Owen ( Lancashire Fusiliers), a famous amateur jockey, which his biographer has identified as due to Wood's keen interest as rider and foxhunter, and Major Hew Dalrymple Fanshawe

Lieutenant-General Sir Hew Dalrymple Fanshawe, (30 October 1860 – 24 March 1957) was a British Army general of the First World War, who commanded V Corps on the Western Front and the 18th Indian Division in the Mesopotamian campaign. He ...

, 19th Hussars

The 19th Royal Hussars (Queen Alexandra's Own) was a cavalry regiment of the British Army, created in 1858. After serving in the First World War, it was amalgamated with the 15th The King's Hussars to form the 15th/19th The King's Royal Hussars i ...

. Fanshawe (who commanded V Corps 5th Corps, Fifth Corps, or V Corps may refer to:

France

* 5th Army Corps (France)

* V Cavalry Corps (Grande Armée), a cavalry unit of the Imperial French Army during the Napoleonic Wars

* V Corps (Grande Armée), a unit of the Imperial French Army ...

during World War I), later became Wood's son-in-law, marrying his elder daughter Anna Pauline Mary on 25 July 1894.

In 1892 Wood was considered for the position of Commander-in-Chief, India

During the period of the Company rule in India and the British Raj, the Commander-in-Chief, India (often "Commander-in-Chief ''in'' or ''of'' India") was the supreme commander of the British Indian Army. The Commander-in-Chief and most of his ...

, a move which the Queen favoured, while the Duke of Cambridge wanted him to become commander-in-chief at Madras

Chennai (, ), formerly known as Madras ( the official name until 1996), is the capital city of Tamil Nadu, the southernmost Indian state. The largest city of the state in area and population, Chennai is located on the Coromandel Coast of th ...

so that the Queen's son the Duke of Connaught

Duke of Connaught and Strathearn was a title in the Peerage of the United Kingdom that was granted on 24 May 1874 by Queen Victoria of the United Kingdom of Great Britain and Ireland to her third son, Prince Arthur. At the same time, he was also ...

(himself a former commander-in-chief at Bombay

Mumbai (, ; also known as Bombay — List of renamed Indian cities and states#Maharashtra, the official name until 1995) is the capital city of the Indian States and union territories of India, state of Maharashtra and the ''de facto'' fin ...

, a few years earlier) could replace him at Aldershot. Henry Brackenbury

General Sir Henry Brackenbury, (1 September 1837 – 20 April 1914) was a British Army officer who was assistant to Garnet Wolseley in the 1870s and became part of his ' Ring' of loyal officers. He also wrote several books of military history ...

, a senior military adviser to the Viceroy of India, thought Wood better suited to remain at Aldershot. Wood became Prime Warden of the Fishmongers' Company

The Worshipful Company of Fishmongers (or Fishmongers' Company) is one of the 110 Livery Companies of the City of London, being an incorporated guild of sellers of fish and seafood in the City. The Company ranks fourth in the order of precede ...

in 1893.

Administering the Army

Wood handed over his command at Aldershot to the Duke of Connaught and saw staff service at the

Wood handed over his command at Aldershot to the Duke of Connaught and saw staff service at the War Office

The War Office was a department of the British Government responsible for the administration of the British Army between 1857 and 1964, when its functions were transferred to the new Ministry of Defence (MoD). This article contains text from ...

as Quartermaster-General to the Forces

The Quartermaster-General to the Forces (QMG) is a senior general in the British Army. The post has become symbolic: the Ministry of Defence organisation charts since 2011 have not used the term "Quartermaster-General to the Forces"; they simply ...

at the War Office from 9 October 1893. There he negotiated new contracts with shipping and railway companies. He was promoted to full general on 26 March 1895. He remained Quartermaster-General until 1897. His duties in the 1890s were similar to those of a Chief of the General Staff, had such a job then existed.

On 1 October 1897 Wood succeeded Buller as Adjutant-General to the Forces at the War Office. Wolseley had succeeded Cambridge as Commander-in-Chief of the Forces in 1895, but his powers were being steadily reduced as his health was failing and he did not get on with Lord Lansdowne (Secretary of State for War

The Secretary of State for War, commonly called War Secretary, was a secretary of state in the Government of the United Kingdom, which existed from 1794 to 1801 and from 1854 to 1964. The Secretary of State for War headed the War Office and ...

), putting the Adjutant-General in a more powerful position. Wolseley accepted the appointment, despite his dislike of Wood, but the two men had very little interaction.

Wood also served as Deputy Lieutenant of Essex from 10 August 1897 and was granted the freedom

Freedom is understood as either having the ability to act or change without constraint or to possess the power and resources to fulfill one's purposes unhindered. Freedom is often associated with liberty and autonomy in the sense of "giving one ...

of the Borough of Chelmsford

Chelmsford () is a city in the City of Chelmsford district in the county of Essex, England. It is the county town of Essex and one of three cities in the county, along with Southend-on-Sea and Colchester. It is located north-east of Londo ...

in 1903. He was also the responsible colonel of the 5th Battalion, the Essex Regiment. Wood wrote several books at this time by writing each day for an hour before daybreak – in 1895 he published a book on the Crimean War, in 1896 a book on Cavalry at Waterloo, and in 1897 ''Achievements of Cavalry''.

He was a patron of Captain Douglas Haig, who had attracted his attention by reporting on French cavalry manoeuvres in the early 1890s, although they did not actually meet face-to-face until an 1895 staff ride where Haig was serving as an aide to Colonel John French. Haig wrote that Wood was "a capital fellow to have upon one’s side as he always gets his own way". He arranged Haig's posting to the 1898 Sudan War – with orders to write privately to him reporting on Kitchener, the general officer commanding, and on his expedition's progress. Wood, who had experience of commanding both infantry and cavalry, supported the concept of mounted infantry

Mounted infantry were infantry who rode horses instead of marching. The original dragoons were essentially mounted infantry. According to the 1911 ''Encyclopædia Britannica'', "Mounted rifles are half cavalry, mounted infantry merely speciall ...

and proposed that each infantry battalion should have one mounted company. The concept of mounted infantry fell back into disfavour in the Edwardian period as French and Haig, pure cavalrymen, rose to the top of the Army. In 1898 Wood also acknowledged the abilities of Sir Charles Dilke

Sir Charles Wentworth Dilke, 2nd Baronet, PC (4 September 1843 – 26 January 1911) was an English Liberal and Radical politician. A republican in the early 1870s, he later became a leader in the radical challenge to Whig control of the Libe ...

, who had returned to Parliament after his divorce scandal of the 1880s and who hoped (in vain, as it turned out) one day to be Secretary of State for War

The Secretary of State for War, commonly called War Secretary, was a secretary of state in the Government of the United Kingdom, which existed from 1794 to 1801 and from 1854 to 1964. The Secretary of State for War headed the War Office and ...

: "You cannot think", remarked Wood, "how grateful I am to anyone who takes an intelligent interest in the Army."

Wolseley informed him that his role in the 1881 Peace made it impossible for him to be given a field command in the Second Boer War

The Second Boer War ( af, Tweede Vryheidsoorlog, , 11 October 189931 May 1902), also known as the Boer War, the Anglo–Boer War, or the South African War, was a conflict fought between the British Empire and the two Boer Republics (the So ...

, despite his offer to serve under Buller, his junior. Nonetheless, he was disappointed when Roberts was appointed commander-in-chief rather than himself. His three sons also served in the war. During the campaign, Evelyn Wood became ill from War Office work. Wood had little say over appointments during the Boer War. In November 1900 Wood was acting Commander-in-Chief of the Forces whilst Lord Roberts returned from South Africa to replace Wolseley. Wood testified to the Royal Commission and gave information, much of it critical of Wolseley, to Leopold Amery for his ''Times History of the War in South Africa''.

Wood continued as Adjutant-General until 1901 and was then appointed to command the II Army Corps and Southern Command 1 October 1901, holding the positions until 1904. On 8 April 1903, he was promoted field marshal

Field marshal (or field-marshal, abbreviated as FM) is the most senior military rank, ordinarily senior to the general officer ranks. Usually, it is the highest rank in an army and as such few persons are appointed to it. It is considered as ...

. He retired on 31 December 1904.

Personal life

Family

Wood's mother was left short of money after 1866 when her husband died and, already 66 years old, she went on to write fourteen novels, translatingVictor Hugo

Victor-Marie Hugo (; 26 February 1802 – 22 May 1885) was a French Romantic writer and politician. During a literary career that spanned more than sixty years, he wrote in a variety of genres and forms. He is considered to be one of the great ...

's ''L’Homme qui Rit'' into English. His sister Anna was also a novelist under her married name Steele – one of her novels featured a henpecked VC who was probably based on her brother. Anna left her husband Colonel Steele on her wedding night – apparently still a virgin – when she discovered that he expected to have sex with her. Evelyn was once sued for assault after striking Colonel Steele in one of the latter's many attempts to "reclaim" his wife. Anna Steele was very close to her brother and allegedly helped to write his speeches.

During the Indian Mutiny another sister, Maria Chambers, conveyed her children to safety through mutineer-controlled country carrying a phial of poison for each child.

Marriage and children

In 1867 Wood married the Hon. Mary Paulina Anne Southwell, a sister ofThomas Southwell, 4th Viscount Southwell

Thomas Arthur Joseph Southwell, 4th Viscount Southwell KP (6 April 1836 – 26 April 1878) was an Irish peer. He was the son of Lieutenant-Colonel Arthur Francis Southwell and Mary Anne Agnes Dillon. He joined the Army, but resigned after only th ...

, a friend from India. Southwell opposed the marriage as the Southwell family were Roman Catholic and Wood, although not a man of particularly strong religious views, refused to leave the Church of England. Having barely seen Paulina for four years, he proposed by letter in 1867 on the understanding that she would never "by a word or even by a look" try to prevent him from volunteering for war service. His marriage hurt his career, as neither Wolseley nor the Duke of Cambridge were impressed by his home life. They had three sons and three daughters but she died on 11 May 1891, while Wood was commanding at Aldershot. After his wife's death Wood was deeply touched to receive 46 letters of condolence from NCOs and private soldiers who had served under him.

Hunting

Wood hunted an average 46 days out of his 60 days leave each year, almost up until his death. He was convinced that hunting was of great value in training officers by encouraging horsemanship and developing an eye for terrain and for rapid decision-making in dangerous situations. He was often injured, on one occasion whilst at Staff College falling on the crown of his head so badly that his neck swelled as if he were suffering from a large double goitre. During the Second Boer War he was injured in the chest when he fell against a crucifix, worn under his shirt, which had belonged to his late wife.Parnell divorce scandal

The Wood family were financially dependent on their wealthy, eccentric spinster Aunt Ben. She gave each sibling £5,000 but Evelyn received nothing since he had married a Catholic. She later paid him an allowance for a time. His brother-in-law later paid him enough of a salary to keep horses, grooms, hounds and servants, supposedly for supervising estates in Ireland, although it is unclear that he ever devoted much time to this task. Wood had to appeal to Aunt Ben for cash after the First Boer War. Wood and his siblings, Charles and Anna, demanded equal shares of Aunt Ben's inheritance, but in March 1888 she made a new will, leaving everything (£150,000 plus lands, ) in a trust for the sole benefit of her favourite niece, Wood's sister Katherine, better known asKitty O'Shea

Katharine Parnell (née Wood; 30 January 1846 – 5 February 1921), known before her second marriage as Katharine O'Shea, and usually called Katie O'Shea by friends and Kitty O'Shea by enemies, was an English woman of aristocratic background ...

. The other siblings tried to have Aunt Ben declared insane, a petition dismissed after she was examined by the eminent physician Sir Andrew Clark. When Aunt Ben died in May 1889, the siblings alleged undue influence by Kitty. Her husband, Captain William O'Shea (18th Hussars

The 18th Royal Hussars (Queen Mary's Own) was a cavalry regiment of the British Army, first formed in 1759. It saw service for two centuries, including the First World War before being amalgamated with the 13th Hussars to form the 13th/18th Royal H ...

), an Irish MP, at this point also contested the will, claiming it contravened his marriage contract and also sued for divorce. Kitty was the lover of the Irish nationalist politician Charles Stewart Parnell

Charles Stewart Parnell (27 June 1846 – 6 October 1891) was an Irish nationalist politician who served as a Member of Parliament (MP) from 1875 to 1891, also acting as Leader of the Home Rule League from 1880 to 1882 and then Leader of t ...

, the ensuing public scandal helped to destroy his career and any chance of Irish Home Rule

The Irish Home Rule movement was a movement that campaigned for self-government (or "home rule") for Ireland within the United Kingdom of Great Britain and Ireland. It was the dominant political movement of Irish nationalism from 1870 to the ...

. It is unclear whether the siblings had encouraged O’Shea in his divorce to blacken Kitty's name. It was suggested that Wood's sister Anna Steele was herself a former lover of William O’Shea – when the will was overturned Anna used her share to live as a recluse, keeping a pet monkey to which she fed anchovy sandwiches. Sir Evelyn probably received about £20,000 () in the eventual settlement.

Final years

After retiring from active service in December 1904, Wood lived at Upminster in

After retiring from active service in December 1904, Wood lived at Upminster in Essex

Essex () is a Ceremonial counties of England, county in the East of England. One of the home counties, it borders Suffolk and Cambridgeshire to the north, the North Sea to the east, Hertfordshire to the west, Kent across the estuary of the Riv ...

His autobiography appeared in 1906.Farwell 1985, p262-3, 266

Wood became colonel of the Royal Horse Guards

The Royal Regiment of Horse Guards (The Blues) (RHG) was a cavalry regiment of the British Army, part of the Household Cavalry.

Raised in August 1650 at Newcastle upon Tyne and County Durham by Sir Arthur Haselrigge on the orders of Oliver Cr ...

in November 1907, making him one of the most senior officers at Horse Guards during a period of fundamental restructuring and reorganization, and a Gold Stick. He became chairman of the Territorial Force Association for the City of London at the start of 1908. As a qualified barrister since 1874, he had become Honorary Colonel of the 14th Middlesex (Inns of Court) Rifle Volunteer Corps in November 1899 and supported its incorporation as an officer training unit in the new Territorial Force

The Territorial Force was a part-time volunteer component of the British Army, created in 1908 to augment British land forces without resorting to conscription. The new organisation consolidated the 19th-century Volunteer Force and yeomanry ...

in 1908. On 11 March 1911 he was appointed Constable of the Tower of London

The Constable of the Tower is the most senior appointment at the Tower of London. In the Middle Ages a constable was the person in charge of a castle when the owner—the king or a nobleman—was not in residence. The Constable of the Tower had a ...

. He was a governor of Gresham's School

Gresham's School is a public school (English independent day and boarding school) in Holt, Norfolk, England, one of the top thirty International Baccalaureate schools in England.

The school was founded in 1555 by Sir John Gresham as a free g ...

from 1899 to 1919.

On 17 June 1913 a year before the outbreak of war, King George V reviewed the Household Cavalry in Windsor Great Park. "With a bevy of princes and famous soldiers" accompanying the King, he inspected "a blue body he Blues in the centrewith red wings flecked with gold ife Guards on either flankand lit up by the twinkling of the sun on many breastplates... ir Evelyn Wood, leading the Blues, hadpaid unusual attention to his personal appearance."Beginning as a courageous young officer and later a successful commander in colonial wars, Evelyn Wood understood the importance of progress and modern technology and lived long enough to see cavalry become almost obsolete. Unlike the brigade commander he was proud to see his regiment operating new weapons: "You can picture my pleasant thoughts when I contrast the spirit of the BLUES turning up to the duties of Machine Gunners, and the false swagger of the men... in a Light Dragoon Regiment" he wrote. In January 1914 he resigned as Chairman of the County Territorial Association in order to express his support for Field Marshal Roberts' campaign for conscription. In his final years he wrote ''Our Fighting Services'' (1916) and ''Winnowed Memories'' (1917) which one historian described as "stuffed with adulatory letters he had received, extracts of speeches he had given and anecdotes in which his wisdom or cleverness figured". Wood died of heart failure in 1919 at the age of 81. His body was buried with full military honours at the Aldershot Military Cemetery in the county of

Hampshire

Hampshire (, ; abbreviated to Hants) is a ceremonial and non-metropolitan county in western South East England on the coast of the English Channel. Home to two major English cities on its south coast, Southampton and Portsmouth, Hampshire ...

. His Victoria Cross is displayed at the National Army Museum

The National Army Museum is the British Army's central museum. It is located in the Chelsea district of central London, adjacent to the Royal Hospital Chelsea, the home of the " Chelsea Pensioners". The museum is a non-departmental public bo ...

in Chelsea, London

Chelsea is an affluent area in west London, England, due south-west of Charing Cross by approximately 2.5 miles. It lies on the north bank of the River Thames and for postal purposes is part of the south-western postal area.

Chelsea histori ...

. A public house

A pub (short for public house) is a kind of drinking establishment which is licensed to serve alcoholic drinks for consumption on the premises. The term ''public house'' first appeared in the United Kingdom in late 17th century, and wa ...

known as the "Sir Evelyn Wood" is located in Widford Road in Chelmsford

Chelmsford () is a city in the City of Chelmsford district in the county of Essex, England. It is the county town of Essex and one of three cities in the county, along with Southend-on-Sea and Colchester. It is located north-east of Londo ...

.

His will was valued for probate at £11,196 4s 10d. ().

Foreign decorations

Wood's foreign decorations included: * Order of the Medjidie (1st Class) (Ottoman Empire) – 8 July 1885 (5th Class – 3 April 1858) *Legion of Honour

The National Order of the Legion of Honour (french: Ordre national de la Légion d'honneur), formerly the Royal Order of the Legion of Honour ('), is the highest French order of merit, both military and civil. Established in 1802 by Napoleo ...

(5th Class) (France) – 2 August 1856

Works

*The Crimea in 1854, and 1894

' (1895) *

Cavalry in the Waterloo Campaign

' (1895) *

Achievements of Cavalry

' (1897) *''From Midshipman to Field Marshal'' (1906)

Vol.1

Vol. 2

*

The Revolt in Hindustan 1857–59

' (1908) *

Our Fighting Services and How They Made the Empire

' (1916) (also known as ''British Battles on Land and Sea'') *

Winnowed Memories

' (1917)

References

Notes

Citations

Sources

* * * * * * * * * * *Further reading

* * * * * *External links

''(Hampshire)''

British Pathé">Funeral of Field Marshal Sir Evelyn Wood VC Pathé, British Pathé

news 1919* *

Works by Evelyn Wood

at Project Gutenberg , - , - , - , - , - , - {{DEFAULTSORT:Wood, Evelyn 1838 births 1919 deaths 13th Hussars officers 17th Lancers officers 73rd Regiment of Foot officers British Army personnel of the Anglo-Zulu War British Army personnel of the Mahdist War British Army recipients of the Victoria Cross British field marshals British military personnel of the First Boer War British military personnel of the Third Anglo-Ashanti War British recipients of the Victoria Cross Burials at Aldershot Military Cemetery Cameronians officers Constables of the Tower of London Fellows of the Royal Geographical Society Governors of Natal Indian Rebellion of 1857 recipients of the Victoria Cross Knights Grand Cross of the Order of St Michael and St George Knights Grand Cross of the Order of the Bath Recipients of the Legion of Honour People educated at Marlborough College People from Braintree District Royal Horse Guards officers Royal Navy officers Royal Navy personnel of the Crimean War Younger sons of baronets Military personnel from Essex