Eurypterida on:

[Wikipedia]

[Google]

[Amazon]

Eurypterids, often informally called sea scorpions, are a group of extinct

Like all other

Like all other

Eurypterids were highly variable in size, depending on factors such as lifestyle, living environment and taxonomic affinity. Sizes around are common in most eurypterid groups. The smallest eurypterid, '' Alkenopterus burglahrensis'', measured just in length.

The largest eurypterid, and the largest known arthropod ever to have lived, is ''

Eurypterids were highly variable in size, depending on factors such as lifestyle, living environment and taxonomic affinity. Sizes around are common in most eurypterid groups. The smallest eurypterid, '' Alkenopterus burglahrensis'', measured just in length.

The largest eurypterid, and the largest known arthropod ever to have lived, is ''

Some eurypterines, such as ''

Some eurypterines, such as ''

In eurypterids, the respiratory organs were located on the ventral body wall (the underside of the opisthosoma). , evolved from opisthosomal appendages, covered the underside and created a gill chamber where the "gill tracts" were located. Depending on the species, the eurypterid gill tract was either triangular or oval in shape and was possibly raised into a cushion-like state. The surface of this gill tract bore several spinules (small spines), which resulted in an enlarged surface area. It was composed of spongy tissue due to many

In eurypterids, the respiratory organs were located on the ventral body wall (the underside of the opisthosoma). , evolved from opisthosomal appendages, covered the underside and created a gill chamber where the "gill tracts" were located. Depending on the species, the eurypterid gill tract was either triangular or oval in shape and was possibly raised into a cushion-like state. The surface of this gill tract bore several spinules (small spines), which resulted in an enlarged surface area. It was composed of spongy tissue due to many

Like all arthropods, eurypterids matured and grew through static developmental stages referred to as

Like all arthropods, eurypterids matured and grew through static developmental stages referred to as

No fossil gut contents from eurypterids are known, so direct evidence of their diet is lacking. The eurypterid biology is particularly suggestive of a carnivorous lifestyle. Not only were many large (in general, most predators tend to be larger than their prey), but they had

No fossil gut contents from eurypterids are known, so direct evidence of their diet is lacking. The eurypterid biology is particularly suggestive of a carnivorous lifestyle. Not only were many large (in general, most predators tend to be larger than their prey), but they had

Until 1882 no eurypterids were known from before the Silurian. Contemporary discoveries since the 1880s have expanded the knowledge of early eurypterids from the

Until 1882 no eurypterids were known from before the Silurian. Contemporary discoveries since the 1880s have expanded the knowledge of early eurypterids from the

Eurypterids were most diverse and abundant between the Middle Silurian and the Early Devonian, with an absolute peak in diversity during the Pridoli epoch, 423 to 419.2 million years ago, of the very latest Silurian. This peak in diversity has been recognized since the early twentieth century; of the approximately 150 species of eurypterids known in 1916, more than half were from the Silurian and a third were from the Late Silurian alone.

Though stylonurine eurypterids generally remained rare and low in number, as had been the case during the preceding Ordovician, eurypterine eurypterids experienced a rapid rise in diversity and number. In most Silurian fossil beds, eurypterine eurypterids account for 90% of all eurypterids present. Though some were likely already present by the Late Ordovician (simply missing from the fossil record so far), a vast majority of eurypterid groups are first recorded in

Eurypterids were most diverse and abundant between the Middle Silurian and the Early Devonian, with an absolute peak in diversity during the Pridoli epoch, 423 to 419.2 million years ago, of the very latest Silurian. This peak in diversity has been recognized since the early twentieth century; of the approximately 150 species of eurypterids known in 1916, more than half were from the Silurian and a third were from the Late Silurian alone.

Though stylonurine eurypterids generally remained rare and low in number, as had been the case during the preceding Ordovician, eurypterine eurypterids experienced a rapid rise in diversity and number. In most Silurian fossil beds, eurypterine eurypterids account for 90% of all eurypterids present. Though some were likely already present by the Late Ordovician (simply missing from the fossil record so far), a vast majority of eurypterid groups are first recorded in

Though the eurypterids continued to be abundant and diversify during the Early Devonian (for instance leading to the evolution of the pterygotid ''Jaekelopterus'', the largest of all arthropods), the group was one of many heavily affected by the

Though the eurypterids continued to be abundant and diversify during the Early Devonian (for instance leading to the evolution of the pterygotid ''Jaekelopterus'', the largest of all arthropods), the group was one of many heavily affected by the

Only three eurypterid families—Adelophthalmidae, Hibbertopteridae and Mycteroptidae—survived the extinction event in its entirety. These were all freshwater animals, rendering the eurypterids extinct in marine environments. With marine eurypterid predators gone,

Only three eurypterid families—Adelophthalmidae, Hibbertopteridae and Mycteroptidae—survived the extinction event in its entirety. These were all freshwater animals, rendering the eurypterids extinct in marine environments. With marine eurypterid predators gone,

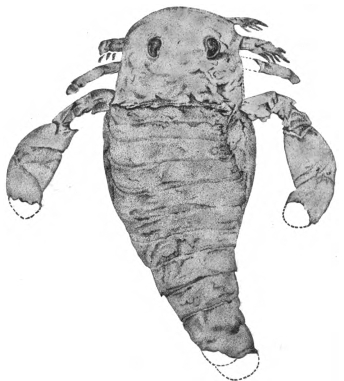

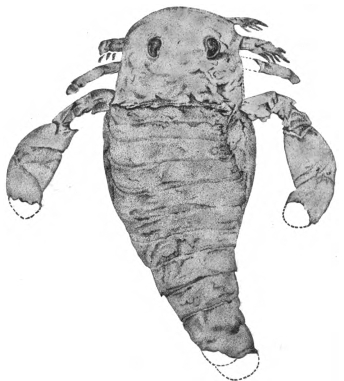

The first known eurypterid specimen was discovered in the Silurian-aged rocks of

The first known eurypterid specimen was discovered in the Silurian-aged rocks of  Jan Nieszkowski's ''De Euryptero Remipede'' (1858) featured an extensive description of ''Eurypterus fischeri'' (now seen as synonymous with another species of ''Eurypterus'', ''E. tetragonophthalmus''), which, along with the monograph ''On the Genus Pterygotus'' by

Jan Nieszkowski's ''De Euryptero Remipede'' (1858) featured an extensive description of ''Eurypterus fischeri'' (now seen as synonymous with another species of ''Eurypterus'', ''E. tetragonophthalmus''), which, along with the monograph ''On the Genus Pterygotus'' by

Eurypterids.co.uk

– An online resource of eurypterid data and research

{{Taxonbar, from=Q19436 Chelicerate orders Darriwilian first appearances Lopingian extinctions Fossil taxa described in 1843 Apex predators

arthropod

Arthropods (, (gen. ποδός)) are invertebrate animals with an exoskeleton, a segmented body, and paired jointed appendages. Arthropods form the phylum Arthropoda. They are distinguished by their jointed limbs and cuticle made of chiti ...

s that form the order

Order, ORDER or Orders may refer to:

* Categorization, the process in which ideas and objects are recognized, differentiated, and understood

* Heterarchy, a system of organization wherein the elements have the potential to be ranked a number of ...

Eurypterida. The earliest known eurypterids date to the Darriwilian

The Darriwilian is the upper stage of the Middle Ordovician. It is preceded by the Dapingian and succeeded by the Upper Ordovician Sandbian Stage. The lower boundary of the Darriwilian is defined as the first appearance of the graptolite specie ...

stage of the Ordovician

The Ordovician ( ) is a geologic period and system, the second of six periods of the Paleozoic Era. The Ordovician spans 41.6 million years from the end of the Cambrian Period million years ago (Mya) to the start of the Silurian Period Mya.

T ...

period 467.3 million years ago

The abbreviation Myr, "million years", is a unit of a quantity of (i.e. ) years, or 31.556926 teraseconds.

Usage

Myr (million years) is in common use in fields such as Earth science and cosmology. Myr is also used with Mya (million years ago ...

. The group is likely to have appeared first either during the Early Ordovician or Late Cambrian period. With approximately 250 species, the Eurypterida is the most diverse Paleozoic

The Paleozoic (or Palaeozoic) Era is the earliest of three geologic eras of the Phanerozoic Eon.

The name ''Paleozoic'' ( ;) was coined by the British geologist Adam Sedgwick in 1838

by combining the Greek words ''palaiós'' (, "old") and ...

chelicerate

The subphylum Chelicerata (from New Latin, , ) constitutes one of the major subdivisions of the phylum Arthropoda. It contains the sea spiders, horseshoe crabs, and arachnids (including harvestmen, scorpions, spiders, solifuges, ticks, and mite ...

order. Following their appearance during the Ordovician, eurypterids became major components of marine faunas during the Silurian

The Silurian ( ) is a geologic period and system spanning 24.6 million years from the end of the Ordovician Period, at million years ago ( Mya), to the beginning of the Devonian Period, Mya. The Silurian is the shortest period of the Paleoz ...

, from which the majority of eurypterid species have been described. The Silurian genus '' Eurypterus'' accounts for more than 90% of all known eurypterid specimens. Though the group continued to diversify during the subsequent Devonian

The Devonian ( ) is a geologic period and system of the Paleozoic era, spanning 60.3 million years from the end of the Silurian, million years ago (Mya), to the beginning of the Carboniferous, Mya. It is named after Devon, England, wh ...

period, the eurypterids were heavily affected by the Late Devonian extinction event. They declined in numbers and diversity until becoming extinct during the Permian–Triassic extinction event

The Permian–Triassic (P–T, P–Tr) extinction event, also known as the Latest Permian extinction event, the End-Permian Extinction and colloquially as the Great Dying, formed the boundary between the Permian and Triassic geologic periods, ...

(or sometime shortly before) 251.9million years ago.

Although popularly called "sea scorpions", only the earliest eurypterids were marine

Marine is an adjective meaning of or pertaining to the sea or ocean.

Marine or marines may refer to:

Ocean

* Maritime (disambiguation)

* Marine art

* Marine biology

* Marine debris

* Marine habitats

* Marine life

* Marine pollution

Military ...

; many later forms lived in brackish

Brackish water, sometimes termed brack water, is water occurring in a natural environment that has more salinity than freshwater, but not as much as seawater. It may result from mixing seawater (salt water) and fresh water together, as in estua ...

or fresh water

Fresh water or freshwater is any naturally occurring liquid or frozen water containing low concentrations of dissolved salts and other total dissolved solids. Although the term specifically excludes seawater and brackish water, it does incl ...

, and they were not true scorpion

Scorpions are predatory arachnids of the order Scorpiones. They have eight legs, and are easily recognized by a pair of grasping pincers and a narrow, segmented tail, often carried in a characteristic forward curve over the back and always en ...

s. Some studies suggest that a dual respiratory system

The respiratory system (also respiratory apparatus, ventilatory system) is a biological system consisting of specific organs and structures used for gas exchange in animals and plants. The anatomy and physiology that make this happen varies g ...

was present, which would have allowed for short periods of time in terrestrial environments. The name ''Eurypterida'' comes from the Ancient Greek

Ancient Greek includes the forms of the Greek language used in ancient Greece and the ancient world from around 1500 BC to 300 BC. It is often roughly divided into the following periods: Mycenaean Greek (), Dark Ages (), the Archaic pe ...

words ('), meaning 'broad' or 'wide', and ('), meaning 'wing', referring to the pair of wide swimming appendages present in many members of the group.

The eurypterids include the largest known arthropods ever to have lived. The largest, ''Jaekelopterus

''Jaekelopterus'' is a genus of predatory eurypterid, a group of extinct aquatic arthropods. Fossils of ''Jaekelopterus'' have been discovered in deposits of Early Devonian age, from the Pragian and Emsian stages. There are two known species: t ...

'', reached in length. Eurypterids were not uniformly large and most species were less than long; the smallest eurypterid, ''Alkenopterus

''Alkenopterus'' is a genus of prehistoric eurypterid classified as part of the family Onychopterellidae. The genus contains two species, ''A. brevitelson'' and ''A. burglahrensis'', both from the Devonian of Germany.

Description

Like the ot ...

'', was only long. Eurypterid fossils have been recovered from every continent. A majority of fossils are from fossil sites in North America

North America is a continent in the Northern Hemisphere and almost entirely within the Western Hemisphere. It is bordered to the north by the Arctic Ocean, to the east by the Atlantic Ocean, to the southeast by South America and th ...

and Europe

Europe is a large peninsula conventionally considered a continent in its own right because of its great physical size and the weight of its history and traditions. Europe is also considered a Continent#Subcontinents, subcontinent of Eurasia ...

because the group lived primarily in the waters around and within the ancient supercontinent of Euramerica

Laurasia () was the more northern of two large landmasses that formed part of the Pangaea supercontinent from around ( Mya), the other being Gondwana. It separated from Gondwana (beginning in the late Triassic period) during the breakup of Pa ...

. Only a handful of eurypterid groups spread beyond the confines of Euramerica and a few genera, such as '' Adelophthalmus'' and ''Pterygotus

''Pterygotus'' is a genus of giant predatory eurypterid, a group of extinct aquatic arthropods. Fossils of ''Pterygotus'' have been discovered in deposits ranging in age from Middle Silurian to Late Devonian, and have been referred to several ...

'', achieved a cosmopolitan distribution

In biogeography, cosmopolitan distribution is the term for the range of a taxon that extends across all or most of the world in appropriate habitats. Such a taxon, usually a species, is said to exhibit cosmopolitanism or cosmopolitism. The extr ...

with fossils being found worldwide.

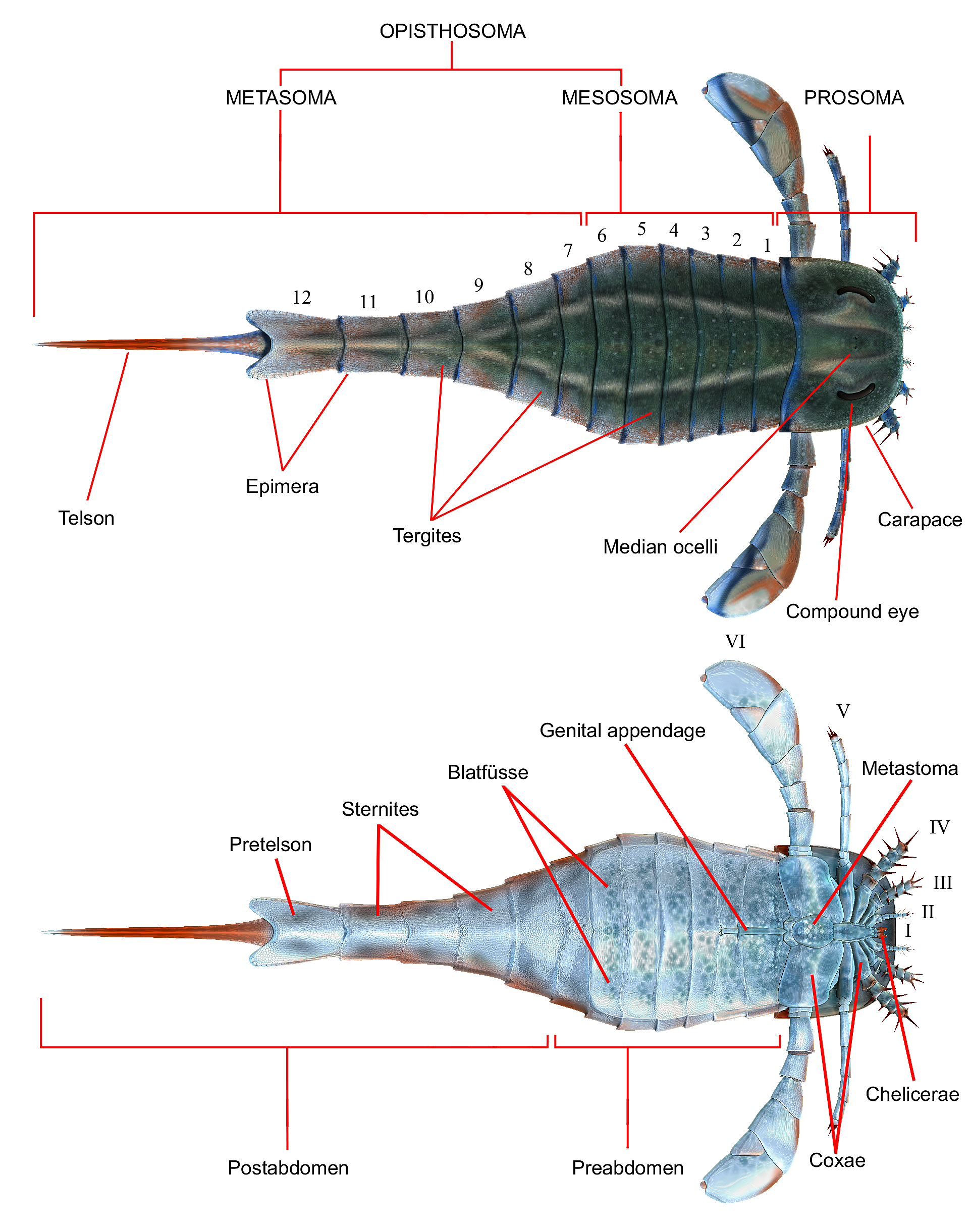

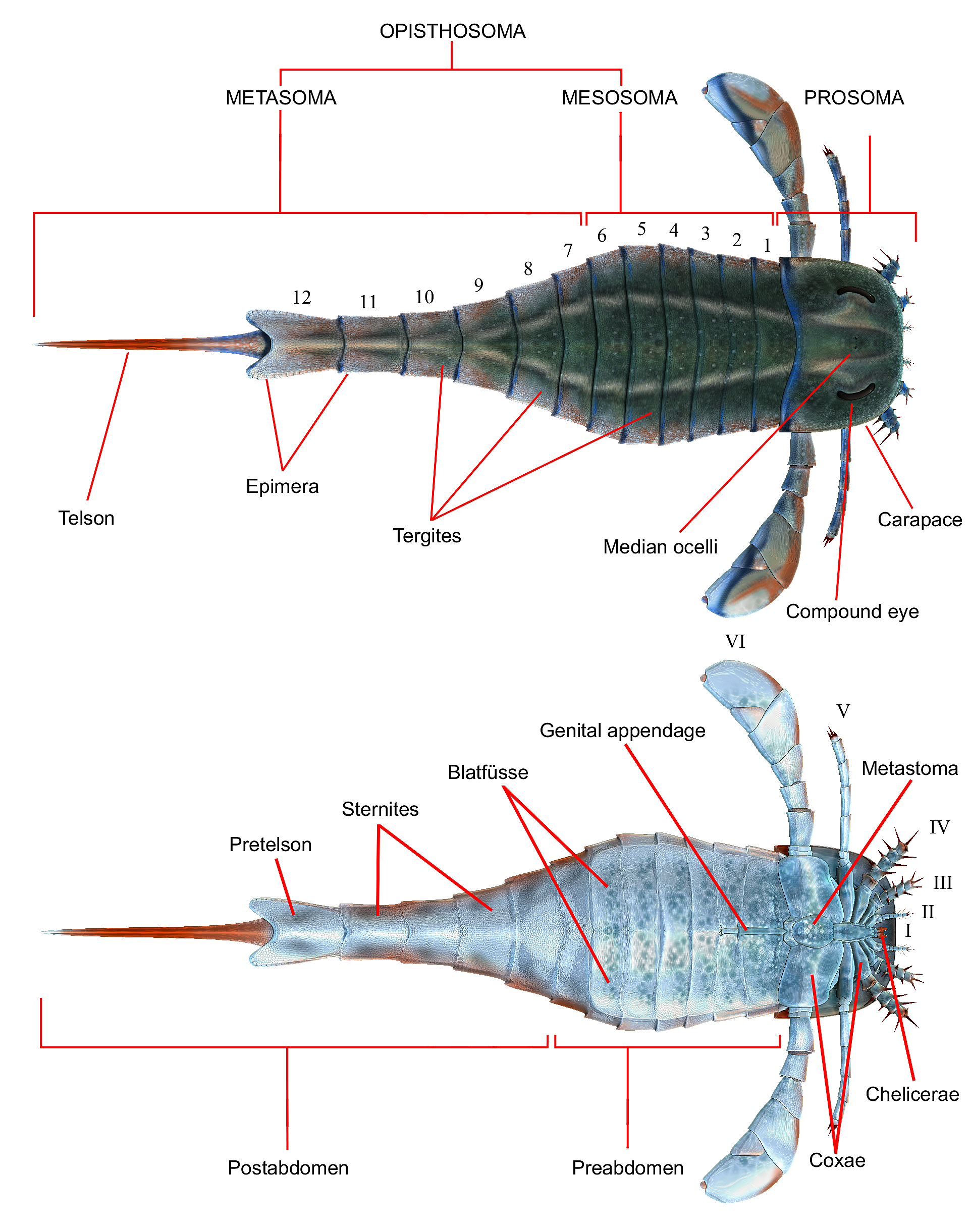

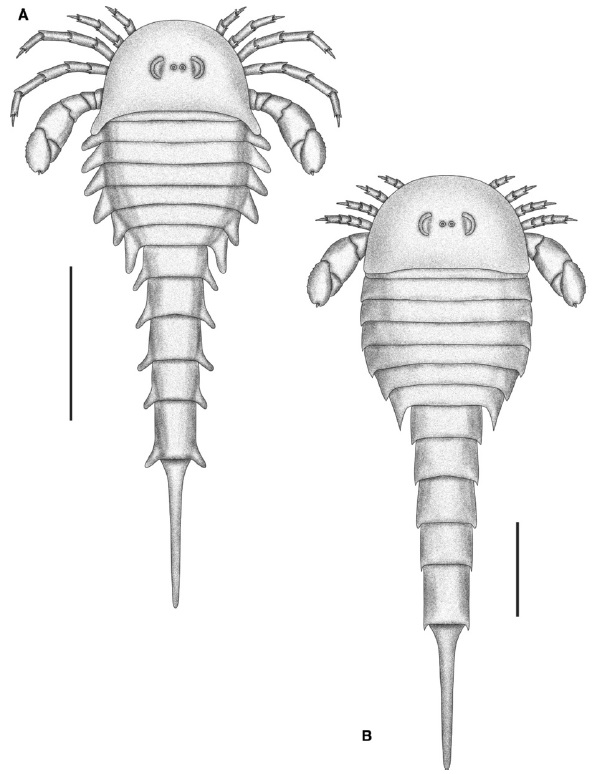

Morphology

Like all other

Like all other arthropod

Arthropods (, (gen. ποδός)) are invertebrate animals with an exoskeleton, a segmented body, and paired jointed appendages. Arthropods form the phylum Arthropoda. They are distinguished by their jointed limbs and cuticle made of chiti ...

s, eurypterids possessed segmented bodies and jointed appendages (limbs) covered in a cuticle

A cuticle (), or cuticula, is any of a variety of tough but flexible, non-mineral outer coverings of an organism, or parts of an organism, that provide protection. Various types of "cuticle" are non- homologous, differing in their origin, structu ...

composed of protein

Proteins are large biomolecules and macromolecules that comprise one or more long chains of amino acid residues. Proteins perform a vast array of functions within organisms, including catalysing metabolic reactions, DNA replication, res ...

s and chitin

Chitin ( C8 H13 O5 N)n ( ) is a long-chain polymer of ''N''-acetylglucosamine, an amide derivative of glucose. Chitin is probably the second most abundant polysaccharide in nature (behind only cellulose); an estimated 1 billion tons of chit ...

. As in other chelicerates, the body was divided into two tagmata (sections); the frontal prosoma

The cephalothorax, also called prosoma in some groups, is a tagma of various arthropods, comprising the head and the thorax fused together, as distinct from the abdomen behind. (The terms ''prosoma'' and ''opisthosoma'' are equivalent to ''cepha ...

(head) and posterior opisthosoma

The opisthosoma is the posterior part of the body in some arthropods, behind the prosoma (cephalothorax). It is a distinctive feature of the subphylum Chelicerata (arachnids, horseshoe crabs and others). Although it is similar in most respects to ...

(abdomen). The prosoma was covered by a carapace

A carapace is a dorsal (upper) section of the exoskeleton or shell in a number of animal groups, including arthropods, such as crustaceans and arachnids, as well as vertebrates, such as turtles and tortoises. In turtles and tortoises, the unde ...

(sometimes called the "prosomal shield") on which both compound eyes and the ocelli

A simple eye (sometimes called a pigment pit) refers to a form of eye or an optical arrangement composed of a single lens and without an elaborate retina such as occurs in most vertebrates. In this sense "simple eye" is distinct from a multi-l ...

(simple eye-like sensory organs) were located.

The prosoma also bore six pairs of appendages which are usually referred to as appendage pairs I to VI. The first pair of appendages, the only pair placed before the mouth, is called the chelicerae

The chelicerae () are the mouthparts of the subphylum Chelicerata, an arthropod group that includes arachnids, horseshoe crabs, and sea spiders. Commonly referred to as " jaws", chelicerae may be shaped as either articulated fangs, or similarl ...

( homologous to the fangs of spiders). They were equipped with small pincers used to manipulate food fragments and push them into the mouth. In one lineage, the Pterygotidae, the chelicerae were large and long, with strong, well-developed teeth on specialised chelae

A chela ()also called a claw, nipper, or pinceris a pincer-like organ at the end of certain limbs of some arthropods. The name comes from Ancient Greek , through New Latin '. The plural form is chelae. Legs bearing a chela are called chelipeds. ...

(claws). The subsequent pairs of appendages, numbers II to VI, possessed gnathobases (or "tooth-plates") on the coxae (limb segments) used for feeding. These appendages were generally walking legs that were cylindrical in shape and were covered in spines in some species. In most lineages, the limbs tended to get larger the farther back they were. In the Eurypterina suborder

Order ( la, ordo) is one of the eight major hierarchical taxonomic ranks in Linnaean taxonomy. It is classified between family and class. In biological classification, the order is a taxonomic rank used in the classification of organisms and ...

, the larger of the two eurypterid suborders, the sixth pair of appendages was also modified into a swimming paddle to aid in traversing aquatic environments.

The opisthosoma comprised 12 segments and the telson

The telson () is the posterior-most division of the body of an arthropod. Depending on the definition, the telson is either considered to be the final segment of the arthropod body, or an additional division that is not a true segment on acco ...

, the posteriormost division of the body, which in most species took the form of a blade-like shape. In some lineages, notably the Pterygotioidea, the Hibbertopteridae

Hibbertopteridae (the name deriving from the type genus ''Hibbertopterus'', meaning "Hibbert's wing") is a family of eurypterids, an extinct group of aquatic arthropods. They were members of the superfamily Mycteropoidea. Hibbertopterids were lar ...

and the Mycteroptidae

Mycteroptidae are a family of eurypterids, a group of extinct chelicerate arthropods commonly known as "sea scorpions". The family is one of three families contained in the superfamily Mycteropoidea (along with Hibbertopteridae and Drepanopterid ...

, the telson was flattened and may have been used as a rudder while swimming. Some genera within the superfamily Carcinosomatoidea, notably '' Eusarcana'', had a telson similar to that of modern scorpion

Scorpions are predatory arachnids of the order Scorpiones. They have eight legs, and are easily recognized by a pair of grasping pincers and a narrow, segmented tail, often carried in a characteristic forward curve over the back and always en ...

s and may have been capable of using it to inject venom

Venom or zootoxin is a type of toxin produced by an animal that is actively delivered through a wound by means of a bite, sting, or similar action. The toxin is delivered through a specially evolved ''venom apparatus'', such as fangs or a st ...

. The coxae of the sixth pair of appendages were overlaid by a plate that is referred to as the metastoma, originally derived from a complete exoskeleton segment. The opisthosoma itself can be divided either into a "mesosoma

The mesosoma is the middle part of the body, or tagma, of arthropods whose body is composed of three parts, the other two being the prosoma and the metasoma. It bears the legs, and, in the case of winged insects, the wings.

In hymenopterans of t ...

" (comprising segments 1 to 6) and "metasoma

The metasoma is the posterior part of the body, or tagma, of arthropods whose body is composed of three parts, the other two being the prosoma and the mesosoma. In insects, it contains most of the digestive tract, respiratory system, and cir ...

" (comprising segments 7 to 12) or into a "preabdomen" (generally comprising segments 1 to 7) and "postabdomen" (generally comprising segments 8 to 12).

The underside of the opisthosoma was covered in structures evolved from modified opisthosomal appendages. Throughout the opisthosoma, these structures formed plate-like structures termed ( in German). These created a branchial chamber (gill tract) between preceding and the ventral

Standard anatomical terms of location are used to unambiguously describe the anatomy of animals, including humans. The terms, typically derived from Latin or Greek roots, describe something in its standard anatomical position. This position prov ...

surface of the opisthosoma itself, which contained the respiratory organs. The second to sixth opisthosomal segments also contained oval or triangular organs that have been interpreted as organs that aid in respiration. These organs, termed or "gill tracts", would potentially have aided eurypterids to breathe air above water, while , similar to organs in modern horseshoe crab

Horseshoe crabs are marine and brackish water arthropods of the family Limulidae and the only living members of the order Xiphosura. Despite their name, they are not true crabs or crustaceans: they are chelicerates, most closely related to ar ...

s, would cover the parts that serve for underwater respiration.

The appendages of opisthosomal segments 1 and 2 (the seventh and eighth segments overall) were fused into a structure termed the genital operculum, occupying most of the underside of the opisthosomal segment 2. Near the anterior

Standard anatomical terms of location are used to unambiguously describe the anatomy of animals, including humans. The terms, typically derived from Latin or Greek language, Greek roots, describe something in its standard anatomical position. Th ...

margin of this structure, the genital appendage (also called the or the median abdominal appendage) protruded. This appendage, often preserved very prominently, has consistently been interpreted as part of the reproductive system and occurs in two recognized types, assumed to correspond to male and female.

Biology

Size

Jaekelopterus rhenaniae

''Jaekelopterus'' is a genus of predatory eurypterid, a group of extinct aquatic arthropods. Fossils of ''Jaekelopterus'' have been discovered in deposits of Early Devonian age, from the Pragian and Emsian stages. There are two known species: t ...

''. A chelicera from the Emsian

The Emsian is one of three faunal stages in the Early Devonian Epoch. It lasted from 407.6 ± 2.6 million years ago to 393.3 ± 1.2 million years ago. It was preceded by the Pragian Stage and followed by the Eifelian Stage. It is named after the ...

Klerf Formation of Willwerath, Germany

Germany,, officially the Federal Republic of Germany, is a country in Central Europe. It is the second most populous country in Europe after Russia, and the most populous member state of the European Union. Germany is situated betwee ...

measured in length, but is missing a quarter of its length, suggesting that the full chelicera would have been long. If the proportions between body length and chelicerae match those of its closest relatives, where the ratio between claw size and body length is relatively consistent, the specimen of ''Jaekelopterus'' that possessed the chelicera in question would have measured between , an average , in length. With the chelicerae extended, another meter (3.28 ft) would be added to this length. This estimate exceeds the maximum body size of all other known giant arthropods by almost half a meter (1.64 ft) even if the extended chelicerae are not included. Two other eurypterids have also been estimated to have reached lengths of 2.5 metres; '' Erettopterus grandis'' (closely related to ''Jaekelopterus'') and '' Hibbertopterus wittebergensis'', but ''E. grandis'' is very fragmentary and the ''H. wittenbergensis'' size estimate is based on trackway evidence, not fossil remains.

The family of ''Jaekelopterus'', the Pterygotidae, is noted for several unusually large species. Both '' Acutiramus'', whose largest member ''A. bohemicus'' measured , and ''Pterygotus

''Pterygotus'' is a genus of giant predatory eurypterid, a group of extinct aquatic arthropods. Fossils of ''Pterygotus'' have been discovered in deposits ranging in age from Middle Silurian to Late Devonian, and have been referred to several ...

,'' whose largest species ''P. grandidentatus'' measured , were gigantic. Several different contributing factors to the large size of the pterygotids have been suggested, including courtship behaviour, predation and competition over environmental resources.

Giant eurypterids were not limited to the family Pterygotidae. An isolated long fossil metastoma of the carcinosomatoid eurypterid '' Carcinosoma punctatum'' indicates the animal would have reached a length of in life, rivalling the pterygotids in size. Another giant was ''Pentecopterus decorahensis

''Pentecopterus'' is a genus of eurypterid, an extinct group of aquatic arthropods. Fossils have been registered from the Darriwilian age of the Middle Ordovician period, as early as 467.3 million years ago. The genus contains only one species, ...

'', a primitive carcinosomatoid, which is estimated to have reached lengths of .

Typical of large eurypterids is a lightweight build. Factors such as locomotion, energy costs in molting

In biology, moulting (British English), or molting (American English), also known as sloughing, shedding, or in many invertebrates, ecdysis, is the manner in which an animal routinely casts off a part of its body (often, but not always, an outer ...

and respiration, as well as the actual physical properties of the exoskeleton

An exoskeleton (from Greek ''éxō'' "outer" and ''skeletós'' "skeleton") is an external skeleton that supports and protects an animal's body, in contrast to an internal skeleton ( endoskeleton) in for example, a human. In usage, some of the ...

, limits the size that arthropods can reach. A lightweight construction significantly decreases the influence of these factors. Pterygotids were particularly lightweight, with most fossilized large body segments preserving as thin and unmineralized. Lightweight adaptations are present in other giant paleozoic arthropods as well, such as the giant millipede ''Arthropleura

''Arthropleura'' () is a genus of extinct millipede arthropods that lived in what is now North America and Europe around 345 to 290 million years ago, from the Viséan stage of the lower Carboniferous Period to the Sakmarian stage of the lower ...

'', and are possibly vital for the evolution of giant size in arthropods.

In addition to the lightweight giant eurypterids, some deep-bodied forms in the family Hibbertopteridae were also very large. A carapace from the Carboniferous of Scotland referred to the species ''Hibbertoperus scouleri'' measures wide. As ''Hibbertopterus'' was very wide compared to its length, the animal in question could possibly have measured just short of in length. More robust than the pterygotids, this giant ''Hibbertopterus'' would possibly have rivalled the largest pterygotids in weight, if not surpassed them, and as such be among the heaviest arthropods.

Locomotion

The two eurypterid suborders, Eurypterina and Stylonurina, are distinguished primarily by the morphology of their final pair of appendages. In the Stylonurina, this appendage takes the form of a long and slender walking leg, while in the Eurypterina, the leg is modified and broadened into a swimming paddle. Other than the swimming paddle, the legs of many eurypterines were far too small to do much more than allow them to crawl across thesea floor

The seabed (also known as the seafloor, sea floor, ocean floor, and ocean bottom) is the bottom of the ocean. All floors of the ocean are known as 'seabeds'.

The structure of the seabed of the global ocean is governed by plate tectonics. Most of ...

. In contrast, a number of stylonurines had elongated and powerful legs that might have allowed them to walk on land (similar to modern crab

Crabs are decapod crustaceans of the infraorder Brachyura, which typically have a very short projecting "tail" (abdomen) ( el, βραχύς , translit=brachys = short, / = tail), usually hidden entirely under the thorax. They live in all th ...

s).

A fossil trackway

A fossil track or ichnite (Greek "''ιχνιον''" (''ichnion'') – a track, trace or footstep) is a fossilized footprint. This is a type of trace fossil. A fossil trackway is a sequence of fossil tracks left by a single organism. Over the yea ...

was discovered in Carboniferous-aged fossil deposits of Scotland in 2005. It was attributed to the stylonurine eurypterid ''Hibbertopterus'' due to a matching size (the trackmaker was estimated to have been about long) and inferred leg anatomy. It is the largest terrestrial trackway—measuring long and averaging in width—made by an arthropod found thus far. It is the first record of land locomotion by a eurypterid. The trackway provides evidence that some eurypterids could survive in terrestrial environments, at least for short periods of time, and reveals information about the stylonurine gait. In ''Hibbertopterus'', as in most eurypterids, the pairs of appendages are different in size (referred to as a heteropodous limb condition). These differently sized pairs would have moved in phase, and the short stride length indicates that ''Hibbertopterus'' crawled with an exceptionally slow speed, at least on land. The large telson was dragged along the ground and left a large central groove behind the animal. Slopes in the tracks at random intervals suggest that the motion was jerky. The gait of smaller stylonurines, such as '' Parastylonurus'', was probably faster and more precise.

The functionality of the eurypterine swimming paddles varied from group to group. In the Eurypteroidea, the paddles were similar in shape to oars. The condition of the joints in their appendages ensured their paddles could only be moved in near-horizontal planes, not upwards or downwards. Some other groups, such as the Pterygotioidea, would not have possessed this condition and were probably able to swim faster. Most eurypterines are generally agreed to have utilized a rowing type of propulsion similar to that of crabs and water beetle

A water beetle is a generalized name for any beetle that is adapted to living in water at any point in its life cycle. Most water beetles can only live in fresh water, with a few marine species that live in the intertidal zone or littoral zone. Th ...

s. Larger individuals may have been capable of underwater flying (or subaqueous flight

Aquatic locomotion or swimming is biologically propelled motion through a liquid medium. The simplest propulsive systems are composed of cilia and flagella. Swimming has evolved a number of times in a range of organisms including arthropods, ...

) in which the motion and shape of the paddles are enough to generate lift

Lift or LIFT may refer to:

Physical devices

* Elevator, or lift, a device used for raising and lowering people or goods

** Paternoster lift, a type of lift using a continuous chain of cars which do not stop

** Patient lift, or Hoyer lift, mobil ...

, similar to the swimming of sea turtle

Sea turtles (superfamily Chelonioidea), sometimes called marine turtles, are reptiles of the order Testudines and of the suborder Cryptodira. The seven existing species of sea turtles are the flatback, green, hawksbill, leatherback, loggerhe ...

s and sea lion

Sea lions are pinnipeds characterized by external ear flaps, long foreflippers, the ability to walk on all fours, short and thick hair, and a big chest and belly. Together with the fur seals, they make up the family Otariidae, eared seals. ...

s. This type of movement has a relatively slower acceleration rate than the rowing type, especially since adults have proportionally smaller paddles than juveniles. However, since the larger sizes of adults mean a higher drag coefficient

In fluid dynamics, the drag coefficient (commonly denoted as: c_\mathrm, c_x or c_) is a dimensionless quantity that is used to quantify the drag or resistance of an object in a fluid environment, such as air or water. It is used in the drag e ...

, using this type of propulsion is more energy-efficient.

Some eurypterines, such as ''

Some eurypterines, such as ''Mixopterus

''Mixopterus'' is a genus of eurypterid, an extinct group of aquatic arthropods. Fossils of ''Mixopterus'' have been discovered in deposits from Late Silurian age, and have been referred to several different species. Fossils have been recovere ...

'' (as inferred from attributed fossil trackways), were not necessarily good swimmers. It likely kept mostly to the bottom, using its swimming paddles for occasional bursts of movements vertically, with the fourth and fifth pairs of appendages positioned backwards to produce minor movement forwards. While walking, it probably used a gait like that of most modern insects. The weight of its long abdomen would have been balanced by two heavy and specialized frontal appendages, and the center of gravity

In physics, the center of mass of a distribution of mass in space (sometimes referred to as the balance point) is the unique point where the weighted relative position of the distributed mass sums to zero. This is the point to which a force ma ...

might have been adjustable by raising and positioning the tail.

Preserved fossilized eurypterid trackways tend to be large and heteropodous and often have an associated telson drag mark along the mid-line (as with the Scottish ''Hibbertopterus'' track). Such trackways have been discovered on every continent except for South America. In some places where eurypterid fossil remains are otherwise rare, such as in South Africa

South Africa, officially the Republic of South Africa (RSA), is the southernmost country in Africa. It is bounded to the south by of coastline that stretch along the South Atlantic and Indian Oceans; to the north by the neighbouring coun ...

and the rest of the former supercontinent Gondwana

Gondwana () was a large landmass, often referred to as a supercontinent, that formed during the late Neoproterozoic (about 550 million years ago) and began to break up during the Jurassic period (about 180 million years ago). The final sta ...

, the discoveries of trackways both predate and outnumber eurypterid body fossils. Eurypterid trackways have been referred to several ichnogenera, most notably ''Palmichnium

''Palmichnium'' ("palm trace") is an ichnofossil genus, interpreted as a eurypterid trackway. It has been found by many places around the world, such as Australia, Canada, United States or Wales.

Its trackways consist of three or four subcircular ...

'' (defined as a series of four tracks often with an associated drag mark in the mid-line), wherein the holotype of the ichnospecies ''P. kosinkiorum'' preserves the largest eurypterid footprints known to date with the found tracks each being about in diameter. Other eurypterid ichnogenera include '' Merostomichnites'' (though it is likely that many specimens actually represent trackways of crustaceans) and '' Arcuites'' (which preserves grooves made by the swimming appendages).

Respiration

In eurypterids, the respiratory organs were located on the ventral body wall (the underside of the opisthosoma). , evolved from opisthosomal appendages, covered the underside and created a gill chamber where the "gill tracts" were located. Depending on the species, the eurypterid gill tract was either triangular or oval in shape and was possibly raised into a cushion-like state. The surface of this gill tract bore several spinules (small spines), which resulted in an enlarged surface area. It was composed of spongy tissue due to many

In eurypterids, the respiratory organs were located on the ventral body wall (the underside of the opisthosoma). , evolved from opisthosomal appendages, covered the underside and created a gill chamber where the "gill tracts" were located. Depending on the species, the eurypterid gill tract was either triangular or oval in shape and was possibly raised into a cushion-like state. The surface of this gill tract bore several spinules (small spines), which resulted in an enlarged surface area. It was composed of spongy tissue due to many invagination

Invagination is the process of a surface folding in on itself to form a cavity, pouch or tube. In developmental biology, invagination is a mechanism that takes place during gastrulation. This mechanism or cell movement happens mostly in the vegeta ...

s in the structure.

Though the is referred to as a "gill tract", it may not necessarily have functioned as actual gills. In other animals, gills are used for oxygen uptake from water and are outgrowths of the body wall. Despite eurypterids clearly being primarily aquatic animals that almost certainly evolved underwater (some eurypterids, such as the pterygotids, would even have been physically unable to walk on land), it is unlikely the "gill tract" contained functional gills when comparing the organ to gills in other invertebrates and even fish. Previous interpretations often identified the eurypterid "gills" as homologous with those of other groups (hence the terminology), with gas exchange occurring within the spongy tract and a pattern of branchio-cardiac and dendritic veins (as in related groups) carrying oxygenated blood into the body. The primary analogy used in previous studies has been horseshoe crabs, though their gill structure and that of eurypterids are remarkably different. In horseshoe crabs, the gills are more complex and composed of many lamellae (plates) which give a larger surface area used for gas exchange. In addition, the gill tract of eurypterids is proportionally much too small to support them if it is analogous to the gills of other groups. To be functional gills, they would have to have been highly efficient and would have required a highly efficient circulatory system. It is considered unlikely, however, that these factors would be enough to explain the large discrepancy between gill tract size and body size.

It has been suggested instead that the "gill tract" was an organ for breathing air, perhaps actually being a lung

The lungs are the primary organs of the respiratory system in humans and most other animals, including some snails and a small number of fish. In mammals and most other vertebrates, two lungs are located near the backbone on either side of ...

, plastron or a pseudotrachea. Plastrons are organs that some arthropods evolved secondarily to breathe air underwater. This is considered an unlikely explanation since eurypterids had evolved in water from the start and they would not have organs evolved from air-breathing organs present. In addition, plastrons are generally exposed on outer parts of the body while the eurypterid gill tract is located behind the . Instead, among arthropod respiratory organs, the eurypterid gill tracts most closely resemble the pseudotracheae found in modern isopods

Isopoda is an order of crustaceans that includes woodlice and their relatives. Isopods live in the sea, in fresh water, or on land. All have rigid, segmented exoskeletons, two pairs of antennae, seven pairs of jointed limbs on the thorax, and ...

. These organs, called pseudotracheae, because of some resemblance to the tracheae

The trachea, also known as the windpipe, is a cartilaginous tube that connects the larynx to the bronchi of the lungs, allowing the passage of air, and so is present in almost all air-breathing animals with lungs. The trachea extends from the la ...

(windpipes) of air-breathing organisms, are lung-like and present within the pleopods (back legs) of isopods. The structure of the pseudotracheae has been compared to the spongy structure of the eurypterid gill tracts. It is possible the two organs functioned in the same way.

Some researchers have suggested that eurypterids may have been adapted to an amphibious lifestyle, using the full gill tract structure as gills and the invaginations within it as pseudotrachea. This mode of life may not have been physiologically possible, however, since water pressure would have forced water into the invaginations leading to asphyxiation

Asphyxia or asphyxiation is a condition of deficient supply of oxygen to the body which arises from abnormal breathing. Asphyxia causes generalized hypoxia, which affects primarily the tissues and organs. There are many circumstances that can ...

. Furthermore, most eurypterids would have been aquatic their entire lives. No matter how much time was spent on land, organs for respiration in underwater environments must have been present. True gills, expected to have been located within the branchial chamber within the , remain unknown in eurypterids.

Ontogeny

Like all arthropods, eurypterids matured and grew through static developmental stages referred to as

Like all arthropods, eurypterids matured and grew through static developmental stages referred to as instar

An instar (, from the Latin '' īnstar'', "form", "likeness") is a developmental stage of arthropods, such as insects, between each moult (''ecdysis''), until sexual maturity is reached. Arthropods must shed the exoskeleton in order to grow or ...

s. These instars were punctuated by periods during which eurypterids went through ecdysis

Ecdysis is the moulting of the cuticle in many invertebrates of the clade Ecdysozoa. Since the cuticle of these animals typically forms a largely inelastic exoskeleton, it is shed during growth and a new, larger covering is formed. The remnan ...

(molting of the cuticle) after which they underwent rapid and immediate growth. Some arthropods, such as insects and many crustaceans, undergo extreme changes over the course of maturing. Chelicerates, including eurypterids, are in general considered to be direct developers, undergoing no extreme changes after hatching (though extra body segments and extra limbs may be gained over the course of ontogeny

Ontogeny (also ontogenesis) is the origination and development of an organism (both physical and psychological, e.g., moral development), usually from the time of fertilization of the egg to adult. The term can also be used to refer to the s ...

in some lineages, such as xiphosurans and sea spider

Sea spiders are marine arthropods of the order Pantopoda ( ‘all feet’), belonging to the class Pycnogonida, hence they are also called pycnogonids (; named after ''Pycnogonum'', the type genus; with the suffix '). They are cosmopolitan, fou ...

s). Whether eurypterids were true direct developers (with hatchlings more or less being identical to adults) or hemianamorphic direct developers (with extra segments and limbs potentially being added during ontogeny) has been controversial in the past.

Hemianamorphic direct development has been observed in many arthropod groups, such as trilobite

Trilobites (; meaning "three lobes") are extinct marine arthropods that form the class Trilobita. Trilobites form one of the earliest-known groups of arthropods. The first appearance of trilobites in the fossil record defines the base of the ...

s, megacheira

Megacheira ("great hands") is an extinct class of predatory arthropods that possessed a pair of great appendages, hence the class name as well as the common name "great appendage arthropods". Their taxonomic position is controversial, with stud ...

ns, basal crustacean

Crustaceans (Crustacea, ) form a large, diverse arthropod taxon which includes such animals as decapoda, decapods, ostracoda, seed shrimp, branchiopoda, branchiopods, argulidae, fish lice, krill, remipedes, isopoda, isopods, barnacles, copepods, ...

s and basal myriapods

Myriapods () are the members of subphylum Myriapoda, containing arthropods such as millipedes and centipedes. The group contains about 13,000 species, all of them terrestrial.

The fossil record of myriapods reaches back into the late Silurian, ...

. True direct development has on occasion been referred to as a trait unique to arachnid

Arachnida () is a class of joint-legged invertebrate animals (arthropods), in the subphylum Chelicerata. Arachnida includes, among others, spiders, scorpions, ticks, mites, pseudoscorpions, harvestmen, camel spiders, whip spiders and vinegar ...

s. There have been few studies on eurypterid ontogeny as there is a general lack of specimens in the fossil record that can confidently be stated to represent juveniles. It is possible that many eurypterid species thought to be distinct actually represent juvenile specimens of other species, with paleontologists rarely considering the influence of ontogeny when describing new species.

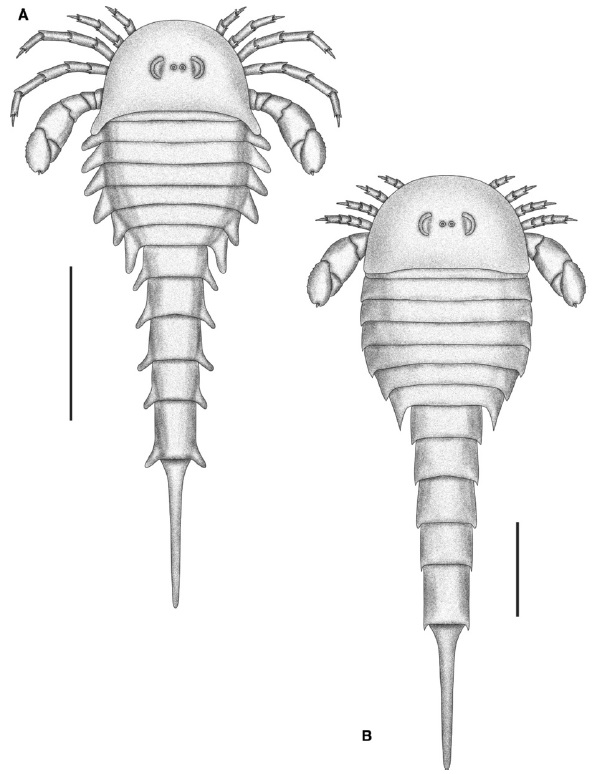

Studies on a well-preserved fossil assemblage of eurypterids from the Pragian

The Pragian is one of three faunal stages in the Early Devonian Epoch. It lasted from 410.8 ± 2.8 million years ago to 407.6 ± 2.8 million years ago. It was preceded by the Lochkovian Stage and followed by the Emsian Stage. The most importan ...

-aged Beartooth Butte Formation in Cottonwood Canyon, Wyoming

Wyoming () is a state in the Mountain West subregion of the Western United States. It is bordered by Montana to the north and northwest, South Dakota and Nebraska to the east, Idaho to the west, Utah to the southwest, and Colorado to t ...

, composed of multiple specimens of various developmental stages of eurypterids ''Jaekelopterus'' and '' Strobilopterus'', revealed that eurypterid ontogeny was more or less parallel and similar to that of extinct and extant xiphosurans, with the largest exception being that eurypterids hatched with a full set of appendages and opisthosomal segments. Eurypterids were thus not hemianamorphic direct developers, but true direct developers like modern arachnids.

The most frequently observed change occurring through ontogeny (except for some genera, such as ''Eurypterus'', which appear to have been static) is the metastoma becoming proportionally less wide. This ontogenetic change has been observed in members of several superfamilies, such as the Eurypteroidea, the Pterygotioidea and the Moselopteroidea.

Feeding

No fossil gut contents from eurypterids are known, so direct evidence of their diet is lacking. The eurypterid biology is particularly suggestive of a carnivorous lifestyle. Not only were many large (in general, most predators tend to be larger than their prey), but they had

No fossil gut contents from eurypterids are known, so direct evidence of their diet is lacking. The eurypterid biology is particularly suggestive of a carnivorous lifestyle. Not only were many large (in general, most predators tend to be larger than their prey), but they had stereoscopic vision

Stereopsis () is the component of depth perception retrieved through binocular vision.

Stereopsis is not the only contributor to depth perception, but it is a major one. Binocular vision happens because each eye receives a different image becaus ...

(the ability to perceive depth). The legs of many eurypterids were covered in thin spines, used both for locomotion and the gathering of food. In some groups, these spiny appendages became heavily specialized. In some eurypterids in the Carcinosomatoidea, forward-facing appendages were large and possessed enormously elongated spines (as in ''Mixopterus'' and '' Megalograptus''). In derived

Derive may refer to:

*Derive (computer algebra system), a commercial system made by Texas Instruments

* ''Dérive'' (magazine), an Austrian science magazine on urbanism

*Dérive, a psychogeographical concept

See also

*

*Derivation (disambiguation ...

members of the Pterygotioidea, the appendages were completely without spines, but had specialized claws instead. Other eurypterids, lacking these specialized appendages, likely fed in a manner similar to modern horseshoe crabs, by grabbing and shredding food with their appendages before pushing it into their mouth using their chelicerae.

Fossils preserving digestive tracts have been reported from fossils of various eurypterids, among them ''Carcinosoma'', ''Acutiramus'' and '' Eurypterus''. Though a potential anal opening has been reported from the telson of a specimen of '' Buffalopterus'', it is more likely that the anus

The anus (Latin, 'ring' or 'circle') is an opening at the opposite end of an animal's digestive tract from the mouth. Its function is to control the expulsion of feces, the residual semi-solid waste that remains after food digestion, which, ...

was opened through the thin cuticle between the last segment before the telson and the telson itself, as in modern horseshoe crabs.

Eurypterid coprolites discovered in deposits of Ordovician age in Ohio containing fragments of a trilobite and eurypterid ''Megalograptus ohioensis'' in association with full specimens of the same eurypterid species have been suggested to represent evidence of cannibalism

Cannibalism is the act of consuming another individual of the same species as food. Cannibalism is a common ecological interaction in the animal kingdom and has been recorded in more than 1,500 species. Human cannibalism is well documented, b ...

. Similar coprolites referred to the species '' Lanarkopterus dolichoschelus'' from the Ordovician of Ohio contain fragments of jawless fish

Agnatha (, Ancient Greek 'without jaws') is an infraphylum of jawless fish in the phylum Chordata, subphylum Vertebrata, consisting of both present ( cyclostomes) and extinct (conodonts and ostracoderms) species. Among recent animals, cyclosto ...

and fragments of smaller specimens of ''Lanarkopterus'' itself.

Though apex predatory roles would have been limited to the very largest eurypterids, smaller eurypterids were likely formidable predators in their own right just like their larger relatives.

Reproductive biology

As in many other entirely extinct groups, understanding and researching the reproduction and sexual dimorphism of eurypterids is difficult, as they are only known from fossilized shells and carapaces. In some cases, there might not be enough apparent differences to separate the sexes based on morphology alone. Sometimes two sexes of the same species have been interpreted as two different species, as was the case with two species of ''Drepanopterus

''Drepanopterus'' is an extinct genus of eurypterid and the only member of the family Drepanopteridae within the Mycteropoidea superfamily. There are currently three species assigned to the genus. The genus has historically included more species ...

'' (''D. bembycoides'' and ''D. lobatus'').

The eurypterid prosoma is made up of the first six exoskeleton segments fused together into a larger structure. The seventh segment (thus the first opisthosomal segment) is referred to as the ''metastoma'' and the eighth segment (distinctly plate-like) is called the ''operculum'' and contains the genital aperature. The underside of this segment is occupied by the genital operculum, a structure originally evolved from ancestral seventh and eighth pair of appendages. In its center, as in modern horseshoe crabs, is a genital appendage. This appendage, an elongated rod with an internal duct, is found in two distinct morphs, generally referred to as "type A" and "type B". These genital appendages are often preserved prominently in fossils and have been the subject of various interpretations of eurypterid reproduction and sexual dimorphism.

Type A appendages are generally longer than those of type B. In some genera they are divided into different numbers of sections, such as in ''Eurypterus'' where the type A appendage is divided into three but the type B appendage into only two. Such division of the genital appendage is common in eurypterids, but the number is not universal; for instance, the appendages of both types in the family Pterygotidae are undivided. The type A appendage is also armed with two curved spines called (lit. 'fork' in Latin). The presence of in the type B appendage is also possible and the structure may represent the unfused tips of the appendages. Located between the dorsal

Dorsal (from Latin ''dorsum'' ‘back’) may refer to:

* Dorsal (anatomy), an anatomical term of location referring to the back or upper side of an organism or parts of an organism

* Dorsal, positioned on top of an aircraft's fuselage

* Dorsal c ...

and ventral surfaces of the associated with the type A appendages is a set of organs traditionally described as either "tubular organs" or "horn organs". These organs are most often interpreted as spermathecae (organs for storing sperm

Sperm is the male reproductive cell, or gamete, in anisogamous forms of sexual reproduction (forms in which there is a larger, female reproductive cell and a smaller, male one). Animals produce motile sperm with a tail known as a flagellum, ...

), though this function is yet to be proven conclusively. In arthropods, spermathecae are used to store the spermatophore

A spermatophore or sperm ampulla is a capsule or mass containing spermatozoa created by males of various animal species, especially salamanders and arthropods, and transferred in entirety to the female's ovipore during reproduction. Spermatophore ...

received from males. This would imply that the type A appendage is the female morph and the type B appendage is the male. Further evidence for the type A appendages representing the female morph of genital appendages comes in their more complex construction (a general trend for female arthropod genitalia). It is possible that the greater length of the type A appendage means that it was used as an ovipositor

The ovipositor is a tube-like organ used by some animals, especially insects, for the laying of eggs. In insects, an ovipositor consists of a maximum of three pairs of appendages. The details and morphology of the ovipositor vary, but typical ...

(used to deposit eggs). The different types of genital appendages are not necessarily the only feature that distinguishes between the sexes of eurypterids. Depending on the genus and species in question, other features such as size, the amount of ornamentation and the proportional width of the body can be the result of sexual dimorphism. In general, eurypterids with type B appendages (males) appear to have been proportionally wider than eurypterids with type A appendages (females) of the same genera.

The primary function of the long, assumed female, type A appendages was likely to take up spermatophore from the substrate into the reproductive tract rather than to serve as an ovipositor, as arthropod ovipositors are generally longer than eurypterid type A appendages. By rotating the sides of the operculum, it would have been possible to lower the appendage from the body. Due to the way different plates overlay at its location, the appendage would have been impossible to move without muscular contractions moving around the operculum. It would have been kept in place when not it use. The on the type A appendages may have aided in breaking open the spermatophore to release the free sperm inside for uptake. The "horn organs," possibly spermathecae, are thought to have been connected directly to the appendage via tracts, but these supposed tracts remain unpreserved in available fossil material.

Type B appendages, assumed male, would have produced, stored and perhaps shaped spermatophore in a heart-shaped structure on the dorsal surface of the appendage. A broad genital opening would have allowed large amounts of spermatophore to be released at once. The long associated with type B appendages, perhaps capable of being lowered like the type A appendage, could have been used to detect whether a substrate was suitable for spermatophore deposition.

Evolutionary history

Origins

Until 1882 no eurypterids were known from before the Silurian. Contemporary discoveries since the 1880s have expanded the knowledge of early eurypterids from the

Until 1882 no eurypterids were known from before the Silurian. Contemporary discoveries since the 1880s have expanded the knowledge of early eurypterids from the Ordovician

The Ordovician ( ) is a geologic period and system, the second of six periods of the Paleozoic Era. The Ordovician spans 41.6 million years from the end of the Cambrian Period million years ago (Mya) to the start of the Silurian Period Mya.

T ...

period. The earliest eurypterids known today, the megalograptid ''Pentecopterus'', date from the Darriwilian

The Darriwilian is the upper stage of the Middle Ordovician. It is preceded by the Dapingian and succeeded by the Upper Ordovician Sandbian Stage. The lower boundary of the Darriwilian is defined as the first appearance of the graptolite specie ...

stage of the Middle Ordovician, 467.3 million years ago

The abbreviation Myr, "million years", is a unit of a quantity of (i.e. ) years, or 31.556926 teraseconds.

Usage

Myr (million years) is in common use in fields such as Earth science and cosmology. Myr is also used with Mya (million years ago ...

. There are also reports of even earlier fossil eurypterids in deposits of Late Tremadocian (Early Ordovician) age in Morocco

Morocco (),, ) officially the Kingdom of Morocco, is the westernmost country in the Maghreb region of North Africa. It overlooks the Mediterranean Sea to the north and the Atlantic Ocean to the west, and has land borders with Algeria to A ...

, but these have yet to be thoroughly studied.

''Pentecopterus'' was a relatively derived eurypterid, part of the megalograptid family within the carcinosomatoid superfamily. Its derived position suggests that most eurypterid clades, at least within the eurypterine suborder, had already been established at this point during the Middle Ordovician. The earliest known stylonurine eurypterid, ''Brachyopterus

''Brachyopterus'' is a genus of prehistoric eurypterid of the family Rhenopteridae. It is one of the earliest known eurypterids, having been recovered from Middle Ordovician deposits in Montgomeryshire, Wales.Dunlop, J. A., Penney, D. & Jekel, ...

'', is also Middle Ordovician in age. The presence of members of both suborders indicates that primitive stem-eurypterids would have preceded them, though these are so far unknown in the fossil record. The presence of several eurypterid clades during the Middle Ordovician suggests that eurypterids either originated during the Early Ordovician and experienced a rapid and explosive radiation and diversification soon after the first forms evolved, or that the group originated much earlier, perhaps during the Cambrian

The Cambrian Period ( ; sometimes symbolized Ꞓ) was the first geological period of the Paleozoic Era, and of the Phanerozoic Eon. The Cambrian lasted 53.4 million years from the end of the preceding Ediacaran Period 538.8 million years ago ...

period.

As such, the exact eurypterid time of origin remains unknown. Though fossils referred to as "primitive eurypterids" have occasionally been described from deposits of Cambrian or even Precambrian

The Precambrian (or Pre-Cambrian, sometimes abbreviated pꞒ, or Cryptozoic) is the earliest part of Earth's history, set before the current Phanerozoic Eon. The Precambrian is so named because it preceded the Cambrian, the first period of th ...

age, they are not recognized as eurypterids, and sometimes not even as related forms, today. Some animals previously seen as primitive eurypterids, such as the genus '' Strabops'' from the Cambrian of Missouri

Missouri is a state in the Midwestern region of the United States. Ranking 21st in land area, it is bordered by eight states (tied for the most with Tennessee): Iowa to the north, Illinois, Kentucky and Tennessee to the east, Arkansas t ...

, are now classified as aglaspidids or strabopids. The aglaspidids, once seen as primitive chelicerates, are now seen as a group more closely related to trilobites.

The fossil record of Ordovician eurypterids is quite poor. The majority of eurypterids once reportedly known from the Ordovician have since proven to be misidentifications or pseudofossils. Today only 11 species can be confidently identified as representing Ordovician eurypterids. These taxa fall into two distinct ecological categories; large and active predators from the ancient continent of Laurentia

Laurentia or the North American Craton is a large continental craton that forms the ancient geological core of North America. Many times in its past, Laurentia has been a separate continent, as it is now in the form of North America, althoug ...

, and demersal

The demersal zone is the part of the sea or ocean (or deep lake) consisting of the part of the water column near to (and significantly affected by) the seabed and the benthos. The demersal zone is just above the benthic zone and forms a layer ...

(living on the seafloor

The seabed (also known as the seafloor, sea floor, ocean floor, and ocean bottom) is the bottom of the ocean

The ocean (also the sea or the world ocean) is the body of salt water that covers approximately 70.8% of the surface of Earth an ...

) and basal animals from the continents Avalonia

Avalonia was a microcontinent in the Paleozoic era. Crustal fragments of this former microcontinent underlie south-west Great Britain, southern Ireland, and the eastern coast of North America. It is the source of many of the older rocks of West ...

and Gondwana. The Laurentian predators, classified in the family Megalograptidae (comprising the genera ''Echinognathus

''Echinognathus'' is a genus of eurypterid, an extinct group of aquatic Arthropod, arthropods. The type and only species of ''Echinognathus'', ''E. clevelandi'', is known from deposits of Late Ordovician age in the United States. The generic name ...

'', ''Megalograptus'' and ''Pentecopterus''), are likely to represent the first truly successful eurypterid group, experiencing a small radiation during the Late Ordovician.

Silurian

Eurypterids were most diverse and abundant between the Middle Silurian and the Early Devonian, with an absolute peak in diversity during the Pridoli epoch, 423 to 419.2 million years ago, of the very latest Silurian. This peak in diversity has been recognized since the early twentieth century; of the approximately 150 species of eurypterids known in 1916, more than half were from the Silurian and a third were from the Late Silurian alone.

Though stylonurine eurypterids generally remained rare and low in number, as had been the case during the preceding Ordovician, eurypterine eurypterids experienced a rapid rise in diversity and number. In most Silurian fossil beds, eurypterine eurypterids account for 90% of all eurypterids present. Though some were likely already present by the Late Ordovician (simply missing from the fossil record so far), a vast majority of eurypterid groups are first recorded in

Eurypterids were most diverse and abundant between the Middle Silurian and the Early Devonian, with an absolute peak in diversity during the Pridoli epoch, 423 to 419.2 million years ago, of the very latest Silurian. This peak in diversity has been recognized since the early twentieth century; of the approximately 150 species of eurypterids known in 1916, more than half were from the Silurian and a third were from the Late Silurian alone.

Though stylonurine eurypterids generally remained rare and low in number, as had been the case during the preceding Ordovician, eurypterine eurypterids experienced a rapid rise in diversity and number. In most Silurian fossil beds, eurypterine eurypterids account for 90% of all eurypterids present. Though some were likely already present by the Late Ordovician (simply missing from the fossil record so far), a vast majority of eurypterid groups are first recorded in strata

In geology and related fields, a stratum ( : strata) is a layer of rock or sediment characterized by certain lithologic properties or attributes that distinguish it from adjacent layers from which it is separated by visible surfaces known as e ...

of Silurian age. These include both stylonurine groups such as the Stylonuroidea

Stylonuroidea is an extinct superfamily of eurypterids, an extinct group of chelicerate arthropods commonly known as "sea scorpions". It is one of four superfamilies classified as part of the suborder Stylonurina.

Stylonuroidea, which lived fro ...

, Kokomopteroidea

Kokomopteroidea is an extinct superfamily of eurypterids, an extinct group of chelicerate arthropods commonly known as "sea scorpions". It is one of four superfamilies classified as part of the suborder Stylonurina. Kokomopteroids have been reco ...

and Mycteropoidea

Mycteropoidea is an extinct superfamily of eurypterids, an extinct group of chelicerate arthropods commonly known as "sea scorpions". It is one of four superfamilies classified as part of the suborder Stylonurina. Mycteropoids have been recovered ...

as well as eurypterine groups such as the Pterygotioidea, Eurypteroidea and Waeringopteroidea.

The most successful eurypterid by far was the Middle to Late Silurian ''Eurypterus'', a generalist, equally likely to have engaged in predation

Predation is a biological interaction where one organism, the predator, kills and eats another organism, its prey. It is one of a family of common feeding behaviours that includes parasitism and micropredation (which usually do not kill ...

or scavenging

Scavengers are animals that consume dead organisms that have died from causes other than predation or have been killed by other predators. While scavenging generally refers to carnivores feeding on carrion, it is also a herbivorous feeding ...

. Thought to have hunted mainly small and soft-bodied invertebrates, such as worm

Worms are many different distantly related bilateral animals that typically have a long cylindrical tube-like body, no limbs, and no eyes (though not always).

Worms vary in size from microscopic to over in length for marine polychaete wor ...

s, species of the genus (of which the most common is the type species, ''E. remipes'') account for more than 90% (perhaps as many as 95%) of all known fossil eurypterid specimens. Despite their vast number, ''Eurypterus'' are only known from a relatively short temporal range, first appearing during the Late Llandovery epoch (around 432 million years ago) and being extinct by the end of the Pridoli epoch. ''Eurypterus'' was also restricted to the continent Euramerica

Laurasia () was the more northern of two large landmasses that formed part of the Pangaea supercontinent from around ( Mya), the other being Gondwana. It separated from Gondwana (beginning in the late Triassic period) during the breakup of Pa ...

(composed of the equator

The equator is a circle of latitude, about in circumference, that divides Earth into the Northern and Southern hemispheres. It is an imaginary line located at 0 degrees latitude, halfway between the North and South poles. The term can also ...

ial continents Avalonia, Baltica

Baltica is a paleocontinent that formed in the Paleoproterozoic and now constitutes northwestern Eurasia, or Europe north of the Trans-European Suture Zone and west of the Ural Mountains.

The thick core of Baltica, the East European Craton, ...

and Laurentia), which had been completely colonized by the genus during its merging and was unable to cross the vast expanses of ocean separating this continent from other parts of the world, such as the southern supercontinent Gondwana. As such, ''Eurypterus'' was limited geographically to the coastlines and shallow inland seas of Euramerica.

During the Late Silurian the pterygotid eurypterids, large and specialized forms with several new adaptations, such as large and flattened telsons capable of being used as rudders, and large and specialized chelicerae with enlarged pincers for handling (and potentially in some cases killing) prey appeared. Though the largest members of the family appeared in the Devonian, large two meter (6.5+ ft) pterygotids such as ''Acutiramus'' were already present during the Late Silurian. Their ecology ranged from generalized predatory behavior to ambush predation

Ambush predators or sit-and-wait predators are carnivorous animals that capture or trap prey via stealth, luring or by (typically instinctive) strategies utilizing an element of surprise. Unlike pursuit predators, who chase to capture prey ...

and some, such as ''Pterygotus'' itself, were active apex predators in Late Silurian marine ecosystems. The pterygotids were also evidently capable of crossing oceans, becoming one of only two eurypterid groups to achieve a cosmopolitan distribution

In biogeography, cosmopolitan distribution is the term for the range of a taxon that extends across all or most of the world in appropriate habitats. Such a taxon, usually a species, is said to exhibit cosmopolitanism or cosmopolitism. The extr ...

.

Devonian

Though the eurypterids continued to be abundant and diversify during the Early Devonian (for instance leading to the evolution of the pterygotid ''Jaekelopterus'', the largest of all arthropods), the group was one of many heavily affected by the

Though the eurypterids continued to be abundant and diversify during the Early Devonian (for instance leading to the evolution of the pterygotid ''Jaekelopterus'', the largest of all arthropods), the group was one of many heavily affected by the Late Devonian extinction

The Late Devonian extinction consisted of several extinction events in the Late Devonian Epoch, which collectively represent one of the five largest mass extinction events in the history of life on Earth. The term primarily refers to a major ex ...

. The extinction event, only known to affect marine life (particularly trilobites, brachiopod

Brachiopods (), phylum Brachiopoda, are a phylum of trochozoan animals that have hard "valves" (shells) on the upper and lower surfaces, unlike the left and right arrangement in bivalve molluscs. Brachiopod valves are hinged at the rear end, w ...

s and reef

A reef is a ridge or shoal of rock, coral or similar relatively stable material, lying beneath the surface of a natural body of water. Many reefs result from natural, abiotic processes—deposition of sand, wave erosion planing down rock ...

-building organisms) effectively crippled the abundance and diversity previously seen within the eurypterids.

A major decline in diversity had already begun during the Early Devonian and eurypterids were rare in marine environments by the Late Devonian. During the Frasnian

The Frasnian is one of two faunal stages in the Late Devonian Period. It lasted from million years ago to million years ago. It was preceded by the Givetian Stage and followed by the Famennian Stage.

Major reef-building was under way during th ...

stage four families went extinct, and the later Famennian

The Famennian is the latter of two faunal stages in the Late Devonian Epoch. The most recent estimate for its duration estimates that it lasted from around 371.1 million years ago to 359.3 million years ago. An earlier 2012 estimate, still used ...

saw an additional five families going extinct. As marine groups were the most affected, the eurypterids were primarily impacted within the eurypterine suborder. Only one group of stylonurines (the family Parastylonuridae) went extinct in the Early Devonian. Only two families of eurypterines survived into the Late Devonian at all (Adelophthalmidae

Adelophthalmidae (the name deriving from the type genus ''Adelophthalmus'', meaning "no obvious eyes") is a family of eurypterids, an extinct group of aquatic arthropods. Adelophthalmidae is the only family classified as part of the superfamily ...

and Waeringopteridae). The eurypterines experienced their most major declines in the Early Devonian, during which over 50% of their diversity was lost in just 10 million years. Stylonurines, on the other hand, persisted through the period with more or less consistent diversity and abundance but were affected during the Late Devonian, when many of the older groups were replaced by new forms in the families Mycteroptidae and Hibbertopteridae.

It is possible that the catastrophic extinction patterns seen in the eurypterine suborder were related to the emergence of more derived fish. Eurypterine decline began at the point when jawless fish first became more developed and coincides with the emergence of placoderms (armored fish) in both North America and Europe.

Stylonurines of the surviving hibbertopterid and mycteroptid families completely avoided competition with fish by evolving towards a new and distinct ecological niche. These families experienced a radiation and diversification through the Late Devonian and Early Carboniferous, the last ever radiation within the eurypterids, which gave rise to several new forms capable of "sweep-feeding" (raking through the substrate in search of prey).

Carboniferous and Permian

Only three eurypterid families—Adelophthalmidae, Hibbertopteridae and Mycteroptidae—survived the extinction event in its entirety. These were all freshwater animals, rendering the eurypterids extinct in marine environments. With marine eurypterid predators gone,

Only three eurypterid families—Adelophthalmidae, Hibbertopteridae and Mycteroptidae—survived the extinction event in its entirety. These were all freshwater animals, rendering the eurypterids extinct in marine environments. With marine eurypterid predators gone, sarcopterygian

Sarcopterygii (; ) — sometimes considered synonymous with Crossopterygii () — is a taxon (traditionally a class or subclass) of the bony fishes known as the lobe-finned fishes. The group Tetrapoda, a mostly terrestrial superclass includ ...

fish, such as the rhizodonts

Rhizodontida is an extinct group of predatory tetrapodomorphs known from many areas of the world from the Givetian through to the Pennsylvanian - the earliest known species is about 377 million years ago (Mya), the latest around 310 Mya. Rhizodo ...

, were the new apex predators in marine environments. The sole surviving eurypterine family, Adelophthalmidae, was represented by only a single genus, '' Adelophthalmus''. The hibbertopterids, mycteroptids and ''Adelophthalmus'' survived into the Permian.

''Adelophthalmus'' became the most common of all late Paleozoic eurypterids, existing in greater number and diversity than surviving stylonurines, and diversified in the absence of other eurypterines. Out of the 33 species referred to ''Adelophthalmus'', 23 (69%) are from the Carboniferous alone. The genus reached its peak diversity in the Late Carboniferous. Though ''Adelophthalmus'' had already been relatively widespread and represented around all major landmasses in the Late Devonian, the amalgamation of Pangaea

Pangaea or Pangea () was a supercontinent that existed during the late Paleozoic and early Mesozoic eras. It assembled from the earlier continental units of Gondwana, Euramerica and Siberia during the Carboniferous approximately 335 million y ...

into a global supercontinent over the course of the last two periods of the Paleozoic allowed ''Adelophthalmus'' to gain an almost worldwide distribution.

During the Late Carboniferous and Early Permian 01 or '01 may refer to:

* The year 2001, or any year ending with 01

* The month of January

* 1 (number)

Music

* 01'' (Richard Müller album), 2001

* ''01'' (Son of Dave album), 2000

* ''01'' (Urban Zakapa album), 2011

* ''O1'' (Hiroyuki Sawan ...

''Adelophthalmus'' was widespread, living primarily in brackish and freshwater environments adjacent to coastal plains. These environments were maintained by favorable climate conditions. They did not persist as climate changes owing to Pangaea's formation altered depositional and vegetational patterns across the world. With their habitat gone, ''Adelophthalmus'' dwindled in number and had already gone extinct by the Leonardian stage of the Early Permian.

Mycteroptids and hibbertopterids continued to survive for some time, with one genus of each group known from Permian strata: '' Hastimima'' and ''Campylocephalus