Erich Fritz Emil Mielke (; 28 December 1907 – 21 May 2000) was a German communist official who served as head of the

East German

East Germany, officially the German Democratic Republic (GDR; german: Deutsche Demokratische Republik, , DDR, ), was a country that existed from its creation on 7 October 1949 until its dissolution on 3 October 1990. In these years the state ...

Ministry for State Security (''Ministerium für Staatsicherheit'' – MfS), better known as the

Stasi, from 1957 until shortly after the fall of the

Berlin Wall in 1989.

A native of

Berlin

Berlin ( , ) is the capital and largest city of Germany by both area and population. Its 3.7 million inhabitants make it the European Union's most populous city, according to population within city limits. One of Germany's sixteen constitu ...

and a second-generation member of the

Communist Party of Germany, Mielke was one of two triggermen in the 1931 murders of Berlin Police captains

Paul Anlauf and Franz Lenck. After learning that a witness had survived, Mielke escaped arrest by fleeing to the Soviet Union, where the

NKVD recruited him. He was one of the key figures in the decimation of Moscow's German Communists during the

Great Purge

The Great Purge or the Great Terror (russian: Большой террор), also known as the Year of '37 (russian: 37-й год, translit=Tridtsat sedmoi god, label=none) and the Yezhovshchina ('period of Yezhov'), was Soviet General Secreta ...

[John O. Koehler, ''The Stasi; The Untold Story of the East German Secret Police'', page 51.] as well as in the

Stalinist witch-hunt for ideological dissent within the

International Brigade during the

Spanish Civil War

The Spanish Civil War ( es, Guerra Civil Española)) or The Revolution ( es, La Revolución, link=no) among Nationalists, the Fourth Carlist War ( es, Cuarta Guerra Carlista, link=no) among Carlism, Carlists, and The Rebellion ( es, La Rebeli ...

.

Following the end of

World War II

World War II or the Second World War, often abbreviated as WWII or WW2, was a world war that lasted from 1939 to 1945. It involved the World War II by country, vast majority of the world's countries—including all of the great power ...

in 1945, Mielke returned to the

Soviet Zone of

Occupied Germany, which he helped organize into a Marxist-Leninist

satellite state under the

Socialist Unity Party (SED), later becoming head of the Stasi.

The Stasi under Mielke has been called by historian Edward Peterson the "most pervasive police state apparatus ever to exist on German soil". In a 1993 interview, Holocaust survivor and Nazi-hunter

Simon Wiesenthal

Simon Wiesenthal (31 December 190820 September 2005) was a Jewish Austrian Holocaust survivor, Nazi hunter, and writer. He studied architecture and was living in Lwów at the outbreak of World War II. He survived the Janowska concentration ...

said that, if one considers only the oppression of their own people, the Stasi under Mielke was "much, much worse than the

Gestapo".

[Koehler (1999), page 8.]

During the 1950s and 1960s Mielke led the process of forcibly forming

collectivised farms from East Germany's family-owned farms, which sent a flood of refugees to

West Germany

West Germany is the colloquial term used to indicate the Federal Republic of Germany (FRG; german: Bundesrepublik Deutschland , BRD) between its formation on 23 May 1949 and the German reunification through the accession of East Germany on 3 ...

. In response, Mielke oversaw the construction (1961) of the

Berlin Wall and co-signed

orders to shoot fatally all East Germans who

attempted to leave the country. He also oversaw the establishment of pro-Soviet police states and paramilitary insurgencies in Western Europe, Latin America, Africa, Southeast Asia, and the Middle East.

In addition to his role as head of the Stasi, Mielke was also an

Army General in the

National People's Army

The National People's Army (german: Nationale Volksarmee, ; NVA ) were the armed forces of the German Democratic Republic (GDR) from 1956 to 1990.

The NVA was organized into four branches: the (Ground Forces), the (Navy), the (Air Force) a ...

(''Nationale Volksarmee''), and a member of the SED's ruling

Politburo. Dubbed "The Master of Fear" (german: der Meister der Angst) by the West German press, Mielke was one of the most powerful and most hated men in East Germany.

After

German reunification in 1990, Mielke was arrested (1991), prosecuted (1992), convicted, and incarcerated (1993) for the

1931 murders of Paul Anlauf and Franz Lenck. Released from prison early due to ill health in 1995, he died in a Berlin nursing home in 2000.

Early life

Erich Mielke was born in a

tenement in

Berlin-Wedding,

Brandenburg

Brandenburg (; nds, Brannenborg; dsb, Bramborska ) is a state in the northeast of Germany bordering the states of Mecklenburg-Vorpommern, Lower Saxony, Saxony-Anhalt, and Saxony, as well as the country of Poland. With an area of 29,480 squ ...

, on 28 December 1907. During the

First World War

World War I (28 July 1914 11 November 1918), often abbreviated as WWI, was List of wars and anthropogenic disasters by death toll, one of the deadliest global conflicts in history. Belligerents included much of Europe, the Russian Empire, ...

, the neighborhood was known as "Red Wedding" due to many residents' Marxist militancy. In a handwritten biography written for the

Soviet secret police, Mielke described his father as "a poor, uneducated woodworker," and said that his mother died in 1911. Both were, he said, members of the

Social Democratic Party of Germany (SPD). After his remarriage to "a seamstress," the elder Mielke and his new wife joined the

Independent Social Democratic Party of Germany and remained members when it was renamed the

Communist Party of Germany (KPD). His son Erich claimed "My younger brother Kurt and two sisters were Communist sympathisers."

Despite his family's poverty, Mielke was sufficiently academically gifted to be awarded a free

scholarship in the prestigious

Köllnisches Gymnasium, but had to leave it a year later, for being "unable to meet the great demands of this school." While attending the Gymnasium, Mielke joined the

Communist Party of Germany in 1925, and worked as a reporter for the

communist newspaper ''

Rote Fahne

''Die Rote Fahne'' (, ''The Red Flag'') was a German newspaper originally founded in 1876 by Socialist Worker's party leader Wilhelm Hasselmann, and which has been since published on and off, at times underground, by German Socialists and Communi ...

'' from 1928 to 1931.

Under the

Weimar Republic

The Weimar Republic (german: link=no, Weimarer Republik ), officially named the German Reich, was the government of Germany from 1918 to 1933, during which it was a Constitutional republic, constitutional federal republic for the first time in ...

, the KPD was the largest communist party in

Europe

Europe is a large peninsula conventionally considered a continent in its own right because of its great physical size and the weight of its history and traditions. Europe is also considered a Continent#Subcontinents, subcontinent of Eurasia ...

and was seen as the "leading party" of the communist movement outside the

Soviet Union

The Soviet Union,. officially the Union of Soviet Socialist Republics. (USSR),. was a transcontinental country that spanned much of Eurasia from 1922 to 1991. A flagship communist state, it was nominally a federal union of fifteen nationa ...

. Under

Ernst Thälmann's leadership, the KPD was completely obedient to

Soviet General Secretary

The Soviet Union,. officially the Union of Soviet Socialist Republics. (USSR),. was a transcontinental country that spanned much of Eurasia from 1922 to 1991. A flagship communist state, it was nominally a federal union of fifteen national ...

Joseph Stalin, and from 1928 the Party was both funded and controlled by the

Comintern in

Moscow

Moscow ( , US chiefly ; rus, links=no, Москва, r=Moskva, p=mɐskˈva, a=Москва.ogg) is the capital and largest city of Russia. The city stands on the Moskva River in Central Russia, with a population estimated at 13.0 million ...

.

Until the end of the Republic, the KPD viewed the

Social Democratic Party of Germany (SPD), which dominated German politics between 1918 and 1931, as their mortal enemy.

In keeping with Stalin's policy towards

social democracy

Social democracy is a political, social, and economic philosophy within socialism that supports political and economic democracy. As a policy regime, it is described by academics as advocating economic and social interventions to promote s ...

, the KPD considered all SPD members to be "

social fascists". The KPD also believed that all other

political parties were "

fascist" and regarded itself as "the only

anti-fascist Party" in Germany.

Nevertheless, the KPD closely collaborated with the

Nazi Party

The Nazi Party, officially the National Socialist German Workers' Party (german: Nationalsozialistische Deutsche Arbeiterpartei or NSDAP), was a far-right political party in Germany active between 1920 and 1945 that created and supported t ...

during the early 1930s and both Parties intended to replace the democratically elected government of the

Weimar Republic

The Weimar Republic (german: link=no, Weimarer Republik ), officially named the German Reich, was the government of Germany from 1918 to 1933, during which it was a Constitutional republic, constitutional federal republic for the first time in ...

with a

totalitarian single party state

A one-party state, single-party state, one-party system, or single-party system is a type of sovereign state in which only one political party has the right to form the government, usually based on the existing constitution. All other parties ...

.

Soon after joining the Party, Mielke joined the KPD's

paramilitary wing, or ''Parteiselbstschutz'' ("Party Self Defense Unit"). At the time, the ''Parteiselbstschutz'' in Berlin was commanded by KPD

Reichstag Representatives

Hans Kippenberger

Hans Kippenberger (15 January 1898 – 3 October 1937) was a German politician (KPD). Between 1928 and 1933 he sat as a member of the National Parliament (''Reichstag'').

Like many Communist Party members at the time, he also operated under " ...

and

Heinz Neumann

Heinz Neumann (6 July 1902 – 26 November 1937) was a German politician from the Communist Party (KPD) and a journalist. He was a member of the Communist International, editor in chief of the party newspaper '' Die Rote Fahne'' and a member of th ...

.

According to John Koehler, "Mielke was a special protege of Kippenberger's having taken to his

paramilitary training with the enthusiasm of a

Prussian Junker.

World War I

World War I (28 July 1914 11 November 1918), often abbreviated as WWI, was List of wars and anthropogenic disasters by death toll, one of the deadliest global conflicts in history. Belligerents included much of Europe, the Russian Empire, ...

veterans taught the novices how to handle pistols, rifles,

machine guns, and

hand grenades. This clandestine training was conducted in the sparsely populated, pastoral countryside surrounding Berlin. Mielke also pleased Kippenberger by being an exceptional student in classes on the arts of conspiratorial behavior and

espionage

Espionage, spying, or intelligence gathering is the act of obtaining secret or confidential information ( intelligence) from non-disclosed sources or divulging of the same without the permission of the holder of the information for a tang ...

, taught by comrades who had studied at the secret M-school of the

GRU in

Moscow

Moscow ( , US chiefly ; rus, links=no, Москва, r=Moskva, p=mɐskˈva, a=Москва.ogg) is the capital and largest city of Russia. The city stands on the Moskva River in Central Russia, with a population estimated at 13.0 million ...

."

[Koehler (1999), page 38.]

According to John Koehler, members of the ''Parteiselbstschutz'' "served as

bouncers at Party meetings and specialized in cracking heads during street battles with political enemies."

Besides the ruling SPD and its paramilitary

Reichsbanner forces, the arch-enemies of the ''Parteiselbstschutz'' were the

Stahlhelm, which was the armed wing of the

Monarchist

Monarchism is the advocacy of the system of monarchy or monarchical rule. A monarchist is an individual who supports this form of government independently of any specific monarch, whereas one who supports a particular monarch is a royalis ...

German National People's Party (DVNP),

Trotskyites, and "radical nationalist parties."

According to Koehler, the KPD's Selbstschutz men "always carried a ''Stahlrute'', two steel springs that telescoped into a tube seventeen centimeters long, which when extended became a deadly, 35-centimeter weapon. Not to be outdone by the Nazis, these street-fighters were often armed with

pistols as well."

In a 1931 biography written for the Cadre Division of the

Comintern, Mielke recalled, "We took care of all kinds of work; terror acts, protecting illegal demonstrations and meetings, arms-trafficking, etc. The last work, which was accomplished by a Comrade and myself, was the Bülowplatz Affair" (german: "Wir erledigten hier alle möglichen Arbeiten, Terrorakte, Schutz illegaler Demonstrationen und Versammlungen, Waffentransport und reinigung usw. Als letzte Arbeit erledigten ein Genosse und ich die Bülowplatzsache.").

Bülowplatz murders

Planning

During the last days of the

Weimar Republic

The Weimar Republic (german: link=no, Weimarer Republik ), officially named the German Reich, was the government of Germany from 1918 to 1933, during which it was a Constitutional republic, constitutional federal republic for the first time in ...

, the KPD had a policy of assassinating two Berlin police officers in retaliation for every KPD member killed by the police.

On 2 August 1931, KPD Members of the

Reichstag Heinz Neumann

Heinz Neumann (6 July 1902 – 26 November 1937) was a German politician from the Communist Party (KPD) and a journalist. He was a member of the Communist International, editor in chief of the party newspaper '' Die Rote Fahne'' and a member of th ...

and

Hans Kippenberger

Hans Kippenberger (15 January 1898 – 3 October 1937) was a German politician (KPD). Between 1928 and 1933 he sat as a member of the National Parliament (''Reichstag'').

Like many Communist Party members at the time, he also operated under " ...

received a dressing down from

Walter Ulbricht, the Party's leader in the Berlin-Brandenburg region. Enraged by police interference and by Neumann and Kippenberger's failure to follow the policy, Ulbricht stated, "At home in

Saxony

Saxony (german: Sachsen ; Upper Saxon German, Upper Saxon: ''Saggsn''; hsb, Sakska), officially the Free State of Saxony (german: Freistaat Sachsen, links=no ; Upper Saxon: ''Freischdaad Saggsn''; hsb, Swobodny stat Sakska, links=no), is a ...

we would have done something about the police a long time ago. Here in Berlin we will not fool around much longer. Soon we will hit the police in the head."

Enraged by Ulbricht's words, Kippenberger and Neumann decided to assassinate

Paul Anlauf

Paul may refer to:

* Paul (given name), a given name (includes a list of people with that name)

*Paul (surname), a list of people

People

Christianity

*Paul the Apostle (AD c.5–c.64/65), also known as Saul of Tarsus or Saint Paul, early Chri ...

, the 42-year-old Captain of the Berlin Police's Seventh Precinct. Captain Anlauf, a widower with three daughters, had been nicknamed "Schweinebacke", or "Pig Face" by the KPD.

According to historian John Koehler, "Of all the policemen in strife-torn Berlin, the reds hated Anlauf the most. His precinct included the area around

KPD headquarters, which made it the most dangerous in the city. The captain almost always led the riot squads that broke up illegal rallies of the Communist Party."

On the morning of Sunday 9 August 1931, Kippenberger and Neumann gave a last briefing to the hit-team in a room at the Lassant beer hall. Mielke and

Erich Ziemer were selected as the shooters. During the meeting,

Max Matern gave a

Luger pistol to fellow lookout Max Thunert and said, "Now we're getting serious. We're going to give Schweinebacke something to remember us by."

Kippenberger then asked Mielke and Ziemer, "Are you sure that you are ready to shoot Schweinebacke?" Mielke responded that he had seen Anlauf many times during police searches of Party Headquarters. Kippenberger then instructed them to wait at a nearby beer hall which would permit them to overlook the entire

Bülow-Platz. He further reminded them that Anlauf was accompanied everywhere by Senior Sergeant Max Willig, whom the KPD had nicknamed, "

Hussar".

Kippenberger concluded, "When you spot Schweinebacke and Hussar, you take care of them." Mielke and Ziemer were informed that, after the assassinations were completed, a diversion would assist in their escape. They were then to return to their homes and await further instructions.

That evening, Anlauf was lured to

Bülow-Platz by a violent rally demanding the dissolution of the

Prussian Parliament

The Landtag of Prussia (german: Preußischer Landtag) was the representative assembly of the Kingdom of Prussia implemented in 1849, a bicameral legislature consisting of the upper House of Lords (''Herrenhaus'') and the lower House of Representa ...

.

According to Koehler, "As was often the case when it came to battling the dominant SPD, the KPD and the Nazis had combined forces during the pre-plebiscite campaign. At one point in this particular campaign,

Nazi

Nazism ( ; german: Nazismus), the common name in English for National Socialism (german: Nationalsozialismus, ), is the far-right totalitarian political ideology and practices associated with Adolf Hitler and the Nazi Party (NSDAP) in ...

propaganda chief

Joseph Goebbels even shared a speaker's platform with KPD agitator

Walter Ulbricht. Both parties wanted the parliament dissolved because they were hoping that new elections would oust the SPD, the sworn enemy of all

radicals

Radical may refer to:

Politics and ideology Politics

*Radical politics, the political intent of fundamental societal change

*Radicalism (historical), the Radical Movement that began in late 18th century Britain and spread to continental Europe and ...

. That fact explained why the atmosphere was particularly volatile this Sunday."

Murder at the Babylon Cinema

At eight o'clock that evening, Mielke and Ziemer waited in a doorway as Anlauf, Willig, and Captain

Franz Lenck Franz may refer to:

People

* Franz (given name)

* Franz (surname)

Places

* Franz (crater), a lunar crater

* Franz, Ontario, a railway junction and unorganized town in Canada

* Franz Lake, in the state of Washington, United States – see Fran ...

walked toward the Babylon Cinema, which was located at the corner of Bülowplatz and Kaiser-Wilhelm-Straße. As they reached the door of the movie house, the policemen heard someone scream, "Schweinebacke!"

[''The Stasi'', p. 41.]

As Anlauf turned toward the sound, Mielke and Ziemer opened fire at point blank range. Willig was wounded in the left arm and the stomach. However, he managed to draw his

Luger pistol and fired a full magazine at the assailants. Lenck was shot in the chest and fell dead in front of the entrance. Willig crawled over and cradled the head of Anlauf, who had taken two bullets in the neck. Before he died, Sergeant Willig heard the Captain gasp, "''Wiedersehen... Gruss...''" ("So Long... Goodbye...").

Meanwhile, Mielke and Ziemer made their escape by running into the theater and out an emergency exit. They tossed their pistols over a fence, where they were later found by Homicide Detectives from the elite Mordkommission. Mielke and Ziemer then returned to their homes.

According to Koehler, "Back at Bülowplatz, the killings had triggered a major police action. At least a thousand officers poured into the square, and a bloody street battle ensued. Rocks and bricks were hurled from the rooftops. Communist

gunmen fired indiscriminately from the roofs of surrounding apartment houses. As darkness fell, police searchlights illuminated the buildings. Using megaphones, officers shouted, "Clear the streets! Move away from the windows! We are returning fire!" By now the rabble had fled the square, but shooting continued as riot squads combed the tenements, arresting hundreds of residents suspected of having fired weapons. The battle lasted until one o'clock the next morning. In addition to the two police officers, the casualties included one Communist who died of a gunshot wound and seventeen others who were seriously wounded."

Anlauf's wife had died three weeks earlier of kidney failure.

[Koehler (1999), page 41.] The murder of Anlauf thus left their three daughters as orphans. Their oldest daughter was forced to rush her planned wedding in order to keep her sisters from being put in an

orphanage. Lenck was survived by his wife.

Willig was hospitalized for 14 weeks, but made a full recovery and returned to active duty. In recognition for Willig's courage, the Berlin Police promoted him to Lieutenant.

After the murders, the act was celebrated at the Lichtenberger Hof, a favorite

beer hall

A beer hall () is a large pub that specializes in beer.

Germany

Beer halls are a traditional part of Bavarian culture, and feature prominently in Oktoberfest. Bosch notes that the beer halls of Oktoberfest, known in German as ''Festzelte'', ...

of the

Rotfrontkämpferbund, where Mielke boasted: "Today we celebrate a job that I pulled!" (german: "Heute wird ein Ding gefeiert, das ich gedreht habe!")

Fugitive

According to Koehler, "Kippenberger was alarmed when word reached him that Sergeant Willig had survived the shooting. Not knowing whether the sergeant could talk and identify the attackers, Kippenberger was taking no chances. He directed a runner to summon Mielke and Ziemer to his apartment at 74 Bellermannstrasse, only a few minutes walk from where the two lived. When the assassins arrived, Kippenberger told them the news and ordered them to leave Berlin at once. The parliamentarian's wife Thea, an unemployed schoolteacher and as staunch a Communist Party member as her husband, shepherded the young murderers to the

Belgian border. Agents of the Communist International (

Comintern) in the port city of

Antwerp supplied them with money and forged

passports. Aboard a merchant ship, they sailed for

Leningrad

Saint Petersburg ( rus, links=no, Санкт-Петербург, a=Ru-Sankt Peterburg Leningrad Petrograd Piter.ogg, r=Sankt-Peterburg, p=ˈsankt pʲɪtʲɪrˈburk), formerly known as Petrograd (1914–1924) and later Leningrad (1924–1991), i ...

. When their ship docked, they were met by another Comintern representative, who escorted them to

Moscow

Moscow ( , US chiefly ; rus, links=no, Москва, r=Moskva, p=mɐskˈva, a=Москва.ogg) is the capital and largest city of Russia. The city stands on the Moskva River in Central Russia, with a population estimated at 13.0 million ...

."

Beginning in 1932, Mielke attended the Comintern's Military Political school under the alias Paul Bach. He later graduated from the

Lenin School shortly before being recruited into the

OGPU.

Trial

According to Koehler, "In mid-March 1933, while attending the Lenin School, Mielke received word from his OGPU sponsors that

Berlin police had arrested Max Thunert, one of the conspirators in the Anlauf and Lenck murders. Within days, fifteen other members of the assassination team were in custody. Mielke had to wait six more months before the details of the police action against his Berlin comrades reached Moscow. On 14 September 1933, Berlin newspapers reported that all fifteen had confessed to their roles in the murders. Arrest warrants were issued for ten others who had fled, including Mielke, Ziemer, Ulbricht, Kippenberger, and Neumann."

Koehler also stated, "Defenders of Mielke later claimed that confessions had been obtained under torture by the Nazi

Gestapo. However, all suspects were in the custody of the regular Berlin city criminal investigation bureau, most of whose detectives were SPD members. Some of the suspects had been nabbed by Nazi

SA men and probably beaten before they were turned over to police. In the 1993 trial of Mielke, the court gave the defense the benefit of the doubt and threw out a number of suspect confessions."

On 19 June 1934, the 15 conspirators were convicted of

first degree murder. The three deemed most culpable, Michael Klause,

Max Matern, and Friedrich Bröde were sentenced to

death. Their co-defendants received sentences ranging from nine months to fifteen years incarceration at hard labor. Klause's sentence was commuted to life in prison based upon his cooperation. Bröde hanged himself in his cell. As a result, only Matern was left to be executed by

beheading

Decapitation or beheading is the total separation of the head from the body. Such an injury is invariably fatal to humans and most other animals, since it deprives the brain of oxygenated blood, while all other organs are deprived of the i ...

on 22 May 1935.

Matern was subsequently glorified as a

martyr by KPD and East German

propaganda. Ziemer was officially

killed in action while fighting on the

Republican-side during the

Spanish Civil War

The Spanish Civil War ( es, Guerra Civil Española)) or The Revolution ( es, La Revolución, link=no) among Nationalists, the Fourth Carlist War ( es, Cuarta Guerra Carlista, link=no) among Carlism, Carlists, and The Rebellion ( es, La Rebeli ...

. Mielke, however, would not face trial for the murders until 1993.

Career in Soviet intelligence

The Great Terror

Although Moscow's German Communist community was decimated during

Joseph Stalin's

Great Purge

The Great Purge or the Great Terror (russian: Большой террор), also known as the Year of '37 (russian: 37-й год, translit=Tridtsat sedmoi god, label=none) and the Yezhovshchina ('period of Yezhov'), was Soviet General Secreta ...

, Mielke survived and was promoted.

In a handwritten autobiography prepared after

World War II

World War II or the Second World War, often abbreviated as WWII or WW2, was a world war that lasted from 1939 to 1945. It involved the World War II by country, vast majority of the world's countries—including all of the great power ...

, Mielke recalled, "During my stay in the S.U. (

Soviet Union

The Soviet Union,. officially the Union of Soviet Socialist Republics. (USSR),. was a transcontinental country that spanned much of Eurasia from 1922 to 1991. A flagship communist state, it was nominally a federal union of fifteen nationa ...

), I participated in all Party discussions of the K.P.D. and also in the problems concerning the establishment of

socialism

Socialism is a left-wing economic philosophy and movement encompassing a range of economic systems characterized by the dominance of social ownership of the means of production as opposed to private ownership. As a term, it describes th ...

and in the

trials against the traitors and

enemies

Enemies or foes are a group that is seen as forcefully adverse or threatening.

Enemies may also refer to:

Literature

* ''Enemies'' (play), a 1906 play by Maxim Gorky

* '' Enemies, A Love Story'', a 1966 novel by Isaac Bashevis Singer

* '' Enem ...

of the S.U."

Among the German communists executed as a result of these "discussions" were Mielke's former mentors

Heinz Neumann

Heinz Neumann (6 July 1902 – 26 November 1937) was a German politician from the Communist Party (KPD) and a journalist. He was a member of the Communist International, editor in chief of the party newspaper '' Die Rote Fahne'' and a member of th ...

and

Hans Kippenberger

Hans Kippenberger (15 January 1898 – 3 October 1937) was a German politician (KPD). Between 1928 and 1933 he sat as a member of the National Parliament (''Reichstag'').

Like many Communist Party members at the time, he also operated under " ...

.

Mielke further recalled, "I was a guest on the honor

grandstand of

Red Square during the

May Day and

October Revolution

The October Revolution,. officially known as the Great October Socialist Revolution. in the Soviet Union, also known as the Bolshevik Revolution, was a revolution in Russia led by the Bolshevik Party of Vladimir Lenin that was a key mom ...

parades. I became acquainted with many comrades of the Federation of World Communist Parties and the War Council of the Special Commission of the

Comintern. I will never forget my meeting with

Comrade Dimitrov, the Chairman of the Comintern, whom I served as an aide together with another comrade. I saw

Comrade Stalin during all demonstrations at Red Square, especially when I stood on the grandstand. I mention these meetings because all these comrades are our models and teachers for our work."

[Koehler (1999), page 52.]

During his time in the USSR, Mielke also developed a lifelong reverence for

Felix Dzerzhinsky, the

Polish aristocrat who founded the

Soviet secret police. Mielke also began an equally permanent habit of calling himself a

Chekist.

In a citation written decades later, Mielke described his philosophy of life, "The Chekist is the political combatant. He is the loyal son of... the

workers' class. He stands at the head of the battle to strengthen the power of our workers' and peasants' state."

Spanish Civil War

From 1936 to 1939, Mielke served in Spain as an operative of the

Servicio de Investigación Militar, the

political police of the

Second Spanish Republic

The Spanish Republic (), commonly known as the Second Spanish Republic (), was the form of government in Spain from 1931 to 1939. The Republic was proclaimed on 14 April 1931, after the deposition of King Alfonso XIII, and was dissolved on 1 ...

.

[John Koehler, "The Stasi," p. 48.] While attached to the staff of, "veteran

GRU agent,"

[ Koehler (1999), page 55.] and future Stasi minister

Wilhelm Zaisser, Mielke used the alias Fritz Leissner.

Bernd Kaufmann, the director of the Stasi's espionage school later said, "The Soviets trusted Mielke implicitly. He earned his spurs in Spain."

At the time, the S.I.M. was heavily staffed by agents of the Soviet NKVD, whose Spanish

rezident was General

Aleksandr Mikhailovich Orlov. According to author

Donald Rayfield, "Stalin,

Yezhov, and

Beria distrusted Soviet participants in the Spanish war. Military advisors like

Vladimir Antonov-Ovseenko, journalists like

Koltsov Koltsov (russian: Кольцов; masculine) or Koltsova (; feminine) is a common Russian surname. It derives from the Russian nickname "Koltso" ().Никонов В. А. "Словарь русских фамилий".Кольцов Сост. Е. Л ...

were open to infection by the heresies, especially

Trotsky's, prevalent among the Republic's supporters. NKVD agents sent to Spain were therefore keener on

abducting and murdering anti-Stalinists among Republican leaders and

International Brigade commanders than on fighting

Franco. The defeat of the Republic, in Stalin's eyes, was caused not by the NKVD's diversionary efforts, but by the treachery of the heretics."

In a 1991 interview,

Walter Janka, a fellow German communist exile and company commander in the

International Brigade, recalled his encounters with Mielke. During the winter of 1936, Janka was summoned by the SIM and interrogated by Mielke. Mielke demanded to know why Janka had voluntarily traveled to Spain rather than being assigned there by the Party. When he told Mielke to get lost, the SIM demoted Janka to the ranks and then expelled him from the International Brigade. Years later, Janka recalled, "While I was fighting at the front, shooting at the

Fascists, Mielke served in the rear, shooting

Trotskyites and

Anarchists."

Upon the defeat of the Spanish Republic, Mielke fled across the Pyrenees Mountains to the

Third French Republic

The French Third Republic (french: Troisième République, sometimes written as ) was the system of government adopted in France from 4 September 1870, when the Second French Empire collapsed during the Franco-Prussian War, until 10 July 194 ...

, which

interned him at

Camp de Rivesaltes,

Pyrénées-Orientales. Mielke, however, managed to send a message to exiled KPD members and, in May 1939, he escaped to

Belgium

Belgium, ; french: Belgique ; german: Belgien officially the Kingdom of Belgium, is a country in Northwestern Europe. The country is bordered by the Netherlands to the north, Germany to the east, Luxembourg to the southeast, France to ...

. Although the

Public Prosecutor of Berlin learned of Mielke's presence and filed for his

extradition, the Belgian Government refused to comply, regarding the assassinations of Captains Anlauf and Lenck as "a political crime."

Both the

Spanish Red Terror and the NKVD and the SIM's

witch hunt for both real and imagined anti-Stalinists, however, had deadly serious political consequences. They horrified numerous formerly pro-Soviet Westerners who had been witnesses, including

John Dos Passos,

Arthur Koestler

Arthur Koestler, (, ; ; hu, Kösztler Artúr; 5 September 1905 – 1 March 1983) was a Hungarian-born author and journalist. Koestler was born in Budapest and, apart from his early school years, was educated in Austria. In 1931, Koestler join ...

and

George Orwell, and caused them to permanently turn against the U.S.S.R.

Mielke's belief in Stalin's official explanation for the defeat, that anti-Stalinists had stabbed the Spanish Republic in the back, continued to shape his attitudes for the rest of his life. In a 1982 speech before a group of senior Stasi officers, Mielke said, "We are not immune from villains among us. If I knew of any already, they wouldn't live past tomorrow. Short shrift. It's because I'm a

Humanist, that I'm of this view."

[Funder (2003), page 57.]

In the same speech, Mielke also said, "All this blithering over to execute or not to execute, for the

death penalty or against—all rot, Comrades. Execute! And, when necessary,

without a court judgment."

World War II

During

World War II

World War II or the Second World War, often abbreviated as WWII or WW2, was a world war that lasted from 1939 to 1945. It involved the World War II by country, vast majority of the world's countries—including all of the great power ...

, Mielke's movements remain mysterious. In a biography written after the war, he claimed to have infiltrated

Organisation Todt under the alias Richard Hebel, but historian John O. Koehler considers this unlikely.

Koehler admits, however, "Mielke's exploits must have been substantial. By war's end, he had been decorated with the

Order of the Red Banner

The Order of the Red Banner (russian: Орден Красного Знамени, Orden Krasnogo Znameni) was the first Soviet military decoration. The Order was established on 16 September 1918, during the Russian Civil War by decree of th ...

, the

Order of the Great Patriotic War First Class, and twice with the

Order of Lenin

The Order of Lenin (russian: Орден Ленина, Orden Lenina, ), named after the leader of the Russian October Revolution, was established by the Central Executive Committee on April 6, 1930. The order was the highest civilian decoration ...

. It is likely that he served as an NKVD agent, at least part of the time with

guerrilla units behind German lines, for he knew all the

partisan songs by heart and sang them in faultless Russian."

Occupied Germany

''Komissariat-5''

On April 25, 1945, Mielke returned to the

Soviet Zone of

Occupied Germany aboard a

special Soviet aircraft that also carried fellow German Communists

Walter Ulbricht,

Wilhelm Zaisser,

Ernst Wollweber, and many of the future leaders of the

East Germany

East Germany, officially the German Democratic Republic (GDR; german: Deutsche Demokratische Republik, , DDR, ), was a country that existed from its creation on 7 October 1949 until German reunification, its dissolution on 3 October 1990. In t ...

.

That same month, Mielke's future handler,

NKGB General

Ivan Serov, travelled to Germany from Warsaw and, from his headquarters in the

Berlin

Berlin ( , ) is the capital and largest city of Germany by both area and population. Its 3.7 million inhabitants make it the European Union's most populous city, according to population within city limits. One of Germany's sixteen constitu ...

suburb

A suburb (more broadly suburban area) is an area within a metropolitan area, which may include commercial and mixed-use, that is primarily a residential area. A suburb can exist either as part of a larger city/urban area or as a separ ...

of

Karlshorst

Karlshorst (, ; ; literally meaning ''Karl's nest'') is a locality in the borough of Lichtenberg in Berlin. Located there are a harness racing track and the Hochschule für Technik und Wirtschaft Berlin (''HTW''), the largest University of Ap ...

, divided the Soviet Zone into "Operative Sectors."

On 10 July 1945, Marshal

Georgy Zhukov

Georgy Konstantinovich Zhukov ( rus, Георгий Константинович Жуков, p=ɡʲɪˈorɡʲɪj kənstɐnʲˈtʲinəvʲɪtɕ ˈʐukəf, a=Ru-Георгий_Константинович_Жуков.ogg; 1 December 1896 – ...

signed SMA Order No. 2, which legalized the re-establishment of "

anti-fascist" political parties like the

Communist Party of Germany (KPD).

[Koehler (1999), page 51.] On 15 July 1945, Mielke walked into the KPD's headquarters and volunteered his services.

In an autobiography written for the KPD, Mielke disclosed—truthfully—his involvement in the 1931 murders of

Berlin Police Captains Anlauf and Lenck, and—mistakenly or misleadingly—that for this he had been tried ''

in absentia'', found guilty, and

sentenced to death. In actuality, Mielke's "name was mentioned in the 1934 trials but he was never tried".

He admitted—truthfully—fighting on the Republican side during the

Spanish Civil War

The Spanish Civil War ( es, Guerra Civil Española)) or The Revolution ( es, La Revolución, link=no) among Nationalists, the Fourth Carlist War ( es, Cuarta Guerra Carlista, link=no) among Carlism, Carlists, and The Rebellion ( es, La Rebeli ...

, but claimed—falsely—that he had been released from the French internment camps and had worked in

Belgium

Belgium, ; french: Belgique ; german: Belgien officially the Kingdom of Belgium, is a country in Northwestern Europe. The country is bordered by the Netherlands to the north, Germany to the east, Luxembourg to the southeast, France to ...

for an underground Communist newspaper under the code name "Gaston". Furthermore, Mielke concealed his past and contemporaneous involvement with the

NKVD,

NKGB, and the Nazi

Organisation Todt (which he asserted he'd infiltrated).

According to Koehler, "As might be expected, Mielke's account of his past was approved by the Soviets. Had Serov not been part of the conspiracy, Mielke would have been instantly arrested or at least subjected to an intense internal investigation because of his membership in the Nazi

Organisation Todt, which used thousands of slave laborers. But he was cleared in record time and by the end of June the Soviets had installed him as a station commander of the newly formed ''

Volkspolizei'' (Vopo), the People's Police."

On 16 August 1947, Serov ordered the creation of ''Kommissariat 5'', the first German

political police since the defeat of

Nazi Germany

Nazi Germany (lit. "National Socialist State"), ' (lit. "Nazi State") for short; also ' (lit. "National Socialist Germany") (officially known as the German Reich from 1933 until 1943, and the Greater German Reich from 1943 to 1945) was ...

.

According to

Anne Applebaum, however, not everyone approved of the plan. In Moscow, Soviet Interior Minister

Viktor Abakumov argued that a new secret police force would be demonized by Western governments and the media, which would paint the K-5 as a "new

Gestapo." Furthermore, Abakumov, like Stalin, intensely distrusted German Communists and alleged that there "were not enough German cadres who have been thoroughly checked." Notwithstanding Abakumov's objections, however, recruitment into the K-5 began almost immediately. It is possible, as

Norman Naimark suspects, that the NKGB had realized that their officers' lack of fluency in the

German language

German ( ) is a West Germanic language mainly spoken in Central Europe. It is the most widely spoken and official or co-official language in Germany, Austria, Switzerland, Liechtenstein, and the Italian province of South Tyrol. It is also a ...

was engendering massive popular resentment.

Wilhelm Zaisser, who had been Mielke's

commanding officer in Republican Spain, was appointed the K-5's head. Mielke was installed as his deputy.

According to John Koehler, "The K-5 was essentially an arm of the Soviet secret police. Its agents were carefully selected veteran German communists who had survived the Nazi-era in Soviet exile or in concentration camps and prisons. Their task was to track down Nazis and anti-communists, including hundreds of members of the Social Democratic Party. Mielke and his fellow bloodhounds performed this task with ruthless precision. The number of arrests became so great that the regular prisons could not hold them. Thus, Serov ordered the establishment or re-opening of eleven

concentration camps, including the former Nazi

death camps

Nazi Germany used six extermination camps (german: Vernichtungslager), also called death camps (), or killing centers (), in Central Europe during World War II to systematically murder over 2.7 million peoplemostly Jewsin the Holocaust. T ...

of

Buchenwald and

Sachsenhausen

Sachsenhausen () or Sachsenhausen-Oranienburg was a German Nazi concentration camp in Oranienburg, Germany, used from 1936 until April 1945, shortly before the defeat of Nazi Germany in May later that year. It mainly held political prisoners ...

."

According to Anne Applebaum, "One of the few documents from that era to survive (most were removed by the KGB or perhaps destroyed, in 1989 or before) mentions a departmental training meeting and included a list of attendees. Topping the list is a group of Soviet advisers. In this sense, K-5 did resemble the political police in the rest of Eastern Europe: as in Hungary, Poland, and the USSR itself, this new political police force was initially extra-governmental, operating outside the ordinary rule of law."

According to Edward N. Peterson, "Not surprisingly, K-5 acquired a reputation as bad as that of Stalin's secret police and worse than that of the Gestapo. At least with the Nazis, albeit fanatically

racist, their victims did not suddenly disappear into the

GULAG

The Gulag, an acronym for , , "chief administration of the camps". The original name given to the system of camps controlled by the State Political Directorate, GPU was the Main Administration of Corrective Labor Camps (, )., name=, group= ...

."

The Amalgamation

Despite the K-5's mass arrests of members of the

Social Democratic Party of Germany (SPD) in the

Soviet Zone, the number of SPD members continued to grow. By March 1946, SPD members outnumbered KPD members by more than 100,000. Fearing that they would lose the elections scheduled for the autumn, the leadership of the KPD asked for and received Stalin's permission to merge the two parties. When the SPD's leadership agreed only to schedule a vote for the rank and file to decide, permission was denied by the Soviet occupation authorities. The K-5 then began mass arrests of SPD members who refused to support the merger.

On 22 April 1946, the remaining leaders of the SPD in the Soviet Zone announced that

they had united with the KPD to form the

Socialist Unity Party of Germany (SED). The SPD in the western zones of

Occupied Germany responded by forming the SPD East Bureau in order to support and finance those Social Democrats who refused to accept the merger. Those who joined or worked with the East Bureau were, however, in serious danger of arrest by the K-5 and trial by Soviet

military tribunals. By 1950, more than 5,000 SPD members and sympathisers had been imprisoned in the Soviet Zone or transferred to the

GULAG

The Gulag, an acronym for , , "chief administration of the camps". The original name given to the system of camps controlled by the State Political Directorate, GPU was the Main Administration of Corrective Labor Camps (, )., name=, group= ...

. More than 400 were either executed or died during their imprisonments.

John Koehler has written that, prior to the spring of 1946, many Germans in the Soviet Zone, "merely shrugged at the wave of arrests, believing that the victims were former Nazi officials and war criminals." But then came the mass arrests of Social Democrats who opposed the merger, who, "were joined by people who had been denounced for making

anti-communist or

anti-Soviet remarks, among their number hundreds who were as young as fourteen years. Although these arrests were made by Germans purporting to be officials of the criminal police, the existence of the K-5

political police eventually was exposed. Mielke, meanwhile, had risen to the post of vice-president of the German Administration for Interior Affairs – the equivalent of the

NKVD – and continued his manipulations from behind the scenes."

Investigation

In January 1947, two retired

Berlin policemen recognized Mielke at an official function. Informing the head of the

criminal police in

West Berlin, the policemen demanded that Mielke be arrested and prosecuted for the murders of Captains Anlauf and Lenck.

[Koehler, ''The Stasi'', page 53.] Wilhelm Kühnast, the

Public Prosecutor of Berlin, was immediately informed and ordered a search of the

Kammergericht archives. To his astonishment, the files of the 1931 murders had survived the wartime bombing of Germany. Finding ample evidence of Mielke's involvement, Kühnast ordered the arrest of the communist policeman.

According to John Koehler, "At that time, the city administration, including the police, was under the control of the

Allied Control Commission

Following the termination of hostilities in World War II, the Allies were in control of the defeated Axis countries. Anticipating the defeat of Germany and Japan, they had already set up the European Advisory Commission and a proposed Far East ...

, which consisted of U.S., British, French, and Soviet military officers. All actions by city officials, including the judiciary, were to be reported to the Commission. The Soviet representative alerted the

MGB. Action was swift.

Marshal Vasily Sokolovsky, who had replaced

Zhukov, protested, and his representatives at the Commission launched a vicious campaign to discredit Kühnast."

The Soviet representatives falsely claimed that Kühnast, a jurist with an impeccable

anti-Nazi record, had been an official of

Roland Freisler's

People's Court. Taking the Soviets at their word, the

Western Allies removed Kühnast from his position and placed him under

house arrest. During the

Berlin airlift

The Berlin Blockade (24 June 1948 – 12 May 1949) was one of the first major international crises of the Cold War. During the multinational occupation of post–World War II Germany, the Soviet Union blocked the Western Allies' railway, ro ...

, Kühnast fled from his home in

East Berlin and was granted

political asylum

The right of asylum (sometimes called right of political asylum; ) is an ancient juridical concept, under which people persecuted by their own rulers might be protected by another sovereign authority, like a second country or another entit ...

in the

American Zone.

Meanwhile, the Soviet authorities confiscated all documents relating to the murders of Captains Anlauf and Lenck. According to Koehler, "The Soviets handed the court records to Mielke. Instead of destroying the incriminating papers, he locked them in his private safe, where they were found when his home was searched in 1990. They were used against him in his trial for murder."

[Koehler (1999), page 417.]

''Deutsche Wirtschaftskommission''

In 1948, Mielke was appointed as security chief of the

German Economic Commission

The German Economic Commission (german: Deutsche Wirtschaftskommission; DWK) was the top administrative body in the Soviet Occupation Zone of Germany prior to the creation of the German Democratic Republic (german: Deutsche Demokratische Republik) ...

(german: Deutsche Wirtschaftskommission), the precursor to the future East German government.

Mielke's task was to investigate the theft and sale of state property on the

black market. He was also charged with intercepting the growing number of refugees fleeing to the

French

French (french: français(e), link=no) may refer to:

* Something of, from, or related to France

** French language, which originated in France, and its various dialects and accents

** French people, a nation and ethnic group identified with Franc ...

,

British, and

American Zones.

Those his security forces caught while attempting to defect were used as slave labor in the

uranium

Uranium is a chemical element with the symbol U and atomic number 92. It is a silvery-grey metal in the actinide series of the periodic table. A uranium atom has 92 protons and 92 electrons, of which 6 are valence electrons. Uranium is weak ...

mines that were providing raw material for the

Soviet atomic bomb project.

German Democratic Republic

Independence

In 1949, the Soviet Military Administration ceded its legal functions to the newly created

German Democratic Republic

German(s) may refer to:

* Germany (of or related to)

** Germania (historical use)

* Germans, citizens of Germany, people of German ancestry, or native speakers of the German language

** For citizens of Germany, see also German nationality law

**G ...

.

On 14 January 1950, Marshal

Vasili Chuikov

Vasily Ivanovich Chuikov (russian: link=no, Васи́лий Ива́нович Чуйко́в; ; – 18 March 1982) was a Soviet military commander and Marshal of the Soviet Union. He is best known for commanding the 62nd Army which saw he ...

announced that all Soviet "internment camps" on German soil had been closed. Soon after, the DWK was absorbed into the newly created Ministry for State Security. In keeping with earlier

syllabic abbreviations along the same lines (see

OrPo,

KriPo

''Kriminalpolizei'' (, "criminal police") is the standard term for the criminal investigation agency within the police forces of Germany, Austria, and the German-speaking cantons of Switzerland. In Nazi Germany, the Kripo was the criminal poli ...

, and

GeStaPo) East Germans immediately dubbed it the "

Stasi" (from Staatssicherheit). With the approval of the Soviets, Mielke's commanding officer from Spain and in the K5,

Wilhelm Zaisser, was appointed as the Stasi's head. Mielke was appointed to his staff with the rank of State Secretary. Mielke was also granted a seat in the SED's ruling

Politburo.

According to John Koehler, "In the five years since the end of World War II, the Soviets and their vassals had arrested between 170,000 and 180,000 Germans. Some 160,000 had passed through the concentration camps, and of these about 65,000 had died, 36,000 had been shipped to the Soviet Gulag, and another 46,000 had been freed."

In 1949, as a response to the remilitarization of East Germany and the Soviet blockade of

West Berlin, the

United States

The United States of America (U.S.A. or USA), commonly known as the United States (U.S. or US) or America, is a country Continental United States, primarily located in North America. It consists of 50 U.S. state, states, a Washington, D.C., ...

,

Great Britain

Great Britain is an island in the North Atlantic Ocean off the northwest coast of continental Europe. With an area of , it is the largest of the British Isles, the largest European island and the ninth-largest island in the world. It ...

,

France

France (), officially the French Republic ( ), is a country primarily located in Western Europe. It also comprises of Overseas France, overseas regions and territories in the Americas and the Atlantic Ocean, Atlantic, Pacific Ocean, Pac ...

,

Belgium

Belgium, ; french: Belgique ; german: Belgien officially the Kingdom of Belgium, is a country in Northwestern Europe. The country is bordered by the Netherlands to the north, Germany to the east, Luxembourg to the southeast, France to ...

, the Netherlands,

Luxembourg

Luxembourg ( ; lb, Lëtzebuerg ; french: link=no, Luxembourg; german: link=no, Luxemburg), officially the Grand Duchy of Luxembourg, ; french: link=no, Grand-Duché de Luxembourg ; german: link=no, Großherzogtum Luxemburg is a small lan ...

, and

Portugal

Portugal, officially the Portuguese Republic ( pt, República Portuguesa, links=yes ), is a country whose mainland is located on the Iberian Peninsula of Southwestern Europe, and whose territory also includes the Atlantic archipelagos of th ...

formed the

North Atlantic Treaty Organization, or NATO. In 1950, as a response to the outbreak of the

Korean War

{{Infobox military conflict

, conflict = Korean War

, partof = the Cold War and the Korean conflict

, image = Korean War Montage 2.png

, image_size = 300px

, caption = Clockwise from top:{ ...

,

West Germany

West Germany is the colloquial term used to indicate the Federal Republic of Germany (FRG; german: Bundesrepublik Deutschland , BRD) between its formation on 23 May 1949 and the German reunification through the accession of East Germany on 3 ...

was also permitted to join NATO, which was then upgraded into a military alliance.

According to Koehler, however, "As the

Cold War

The Cold War is a term commonly used to refer to a period of geopolitical tension between the United States and the Soviet Union and their respective allies, the Western Bloc and the Eastern Bloc. The term '' cold war'' is used because t ...

intensified, living conditions in Soviet-occupied East Germany showed little improvement beyond the postwar level of bare subsistence. The new government of the DDR – a mere puppet of the

Kremlin – relied more and more on the Stasi to quell discontent among factory workers and farmers. Ulbricht, claiming that the social unrest was fomented by capitalist agents, once ordered Mielke to personally visit one large plant and 'arrest four or five such agents' as an example to the others. The Stasi deputy 'discovered' the agents in record time."

[Koehler (1999), page 58.]

Field show trials

Also in 1949,

Noel Field, an

American

American(s) may refer to:

* American, something of, from, or related to the United States of America, commonly known as the "United States" or "America"

** Americans, citizens and nationals of the United States of America

** American ancestry, pe ...

citizen who had spied for the

NKVD from inside the

U.S. State Department

The United States Department of State (DOS), or State Department, is an executive department of the U.S. federal government responsible for the country's foreign policy and relations. Equivalent to the ministry of foreign affairs of other n ...

, the

Office of Strategic Services, and the

CIA

The Central Intelligence Agency (CIA ), known informally as the Agency and historically as the Company, is a civilian foreign intelligence service of the federal government of the United States, officially tasked with gathering, processing, ...

, fled from his posting in

Switzerland

). Swiss law does not designate a ''capital'' as such, but the federal parliament and government are installed in Bern, while other federal institutions, such as the federal courts, are in other cities (Bellinzona, Lausanne, Luzern, Neuchâtel ...

to

Communist Czechoslovakia after his cover was blown by fellow

mole Whittaker Chambers. On 11 May 1949, the Czechoslovakian

secret police

Secret police (or political police) are intelligence, security or police agencies that engage in covert operations against a government's political, religious, or social opponents and dissidents. Secret police organizations are characteristic ...

, or

StB, in obedience to a direct order from

KGB chief

Lavrenti Beria

Lavrentiy Pavlovich Beria (; rus, Лавре́нтий Па́влович Бе́рия, Lavréntiy Pávlovich Bériya, p=ˈbʲerʲiə; ka, ლავრენტი ბერია, tr, ; – 23 December 1953) was a Georgian Bolshevik ...

, arrested Field in

Prague

Prague ( ; cs, Praha ; german: Prag, ; la, Praga) is the capital and largest city in the Czech Republic, and the historical capital of Bohemia. On the Vltava river, Prague is home to about 1.3 million people. The city has a temperate ...

. Field was then handed over to the

Hungarian ÁVO

The State Protection Authority ( hu, Államvédelmi Hatóság, ÁVH) was the secret police of the People's Republic of Hungary from 1945 to 1956. The ÁVH was conceived as an external appendage of the Soviet Union's KGB in Hungary responsible ...

. After his interrogation in

Budapest

Budapest (, ; ) is the capital and most populous city of Hungary. It is the ninth-largest city in the European Union by population within city limits and the second-largest city on the Danube river; the city has an estimated population o ...

, Fields was used as a witness at

show trials of senior

Soviet Bloc Communists who, like

László Rajk and

Rudolf Slánský, stood accused of having spied for the

United States

The United States of America (U.S.A. or USA), commonly known as the United States (U.S. or US) or America, is a country Continental United States, primarily located in North America. It consists of 50 U.S. state, states, a Washington, D.C., ...

. The real reason for the trials was to replace homegrown Communists in Eastern Europe with those who would be blindly loyal to

Joseph Stalin and to blame the division of Germany on the intrigues of U.S. intelligence.

At the Rajk show trial, the prosecutor declared, "Noel Field, one of the leaders of American espionage, specialized in recruiting spies from among left-wing elements."

In August 1950, six senior

SED members, including

Willi Kreikemeyer, the director of

Deutsche Reichsbahn and head of

Berliner Rundfunk, were accused of "special connections with Noel Field, the American spy." All were either imprisoned or shot.

John Koehler writes, "Similar purges were conducted in

Czechoslovakia

, rue, Чеськословеньско, , yi, טשעכאסלאוואקיי,

, common_name = Czechoslovakia

, life_span = 1918–19391945–1992

, p1 = Austria-Hungary

, image_p1 ...

,

Hungary

Hungary ( hu, Magyarország ) is a landlocked country in Central Europe. Spanning of the Carpathian Basin, it is bordered by Slovakia to the north, Ukraine to the northeast, Romania to the east and southeast, Serbia to the south, Cr ...

, and

Bulgaria

Bulgaria (; bg, България, Bǎlgariya), officially the Republic of Bulgaria,, ) is a country in Southeast Europe. It is situated on the eastern flank of the Balkans, and is bordered by Romania to the north, Serbia and North Macedo ...

, where Field appeared as a witness in show trials that resulted in some death sentences. The Soviets simply distrusted all Communists who had sought exile in the West. All the while, Mielke remained untouched and continued to serve as the deputy secret police chief. His survival reinforced the belief that he had spent the war years in the

Soviet Union

The Soviet Union,. officially the Union of Soviet Socialist Republics. (USSR),. was a transcontinental country that spanned much of Eurasia from 1922 to 1991. A flagship communist state, it was nominally a federal union of fifteen nationa ...

instead of

France

France (), officially the French Republic ( ), is a country primarily located in Western Europe. It also comprises of Overseas France, overseas regions and territories in the Americas and the Atlantic Ocean, Atlantic, Pacific Ocean, Pac ...

and

Belgium

Belgium, ; french: Belgique ; german: Belgien officially the Kingdom of Belgium, is a country in Northwestern Europe. The country is bordered by the Netherlands to the north, Germany to the east, Luxembourg to the southeast, France to ...

as he had claimed in the 1945 questionnaire."

In June 1950, Erica Wallach, Noel Field's adopted daughter, decided to search for him. From

Paris

Paris () is the capital and most populous city of France, with an estimated population of 2,165,423 residents in 2019 in an area of more than 105 km² (41 sq mi), making it the 30th most densely populated city in the world in 2020. Si ...

, she telephoned

Leo Bauer, the

editor-in-chief

An editor-in-chief (EIC), also known as lead editor or chief editor, is a publication's editorial leader who has final responsibility for its operations and policies.

The highest-ranking editor of a publication may also be titled editor, managing ...

of

Berliner Rundfunk. The call was monitored by agents of the Soviet

Ministry for Internal Affairs, and Bauer's handler instructed him to invite Mrs. Wallach to

East Berlin, where she was immediately arrested. Mielke personally interrogated her and, at one point, offered Mrs. Wallach immediate release if she named the members of her fictitious spy network.

She was condemned to death by a Soviet

military tribunal in

East Berlin and shipped to the

Lubianka prison

The Lubyanka ( rus, Лубянка, p=lʊˈbʲankə) is the popular name for the building which contains the headquarters of the FSB, and its affiliated prison, on Lubyanka Square in the Meshchansky District of Moscow, Russia. It is a large Ne ...

in

Moscow

Moscow ( , US chiefly ; rus, links=no, Москва, r=Moskva, p=mɐskˈva, a=Москва.ogg) is the capital and largest city of Russia. The city stands on the Moskva River in Central Russia, with a population estimated at 13.0 million ...

for her execution. After

Joseph Stalin's death in on 5 March 1953, Erica Wallach's sentence was reduced to hard labor in

Vorkuta

Vorkuta (russian: Воркута́; kv, Вӧркута, ''Vörkuta''; Nenets for "the abundance of bears", "bear corner") is a coal-mining town in the Komi Republic, Russia, situated just north of the Arctic Circle in the Pechora coal basin ...

, a region of the

Gulag

The Gulag, an acronym for , , "chief administration of the camps". The original name given to the system of camps controlled by the State Political Directorate, GPU was the Main Administration of Corrective Labor Camps (, )., name=, group= ...

located above the

Arctic Circle. She was released during the

Khrushchev thaw in October 1955. At first, she was unable to join her husband and daughters in the U.S. because of the

U.S. State Department

The United States Department of State (DOS), or State Department, is an executive department of the U.S. federal government responsible for the country's foreign policy and relations. Equivalent to the ministry of foreign affairs of other n ...

's concern over her former membership in the

Communist Party of Germany. It took the personal intervention of

CIA

The Central Intelligence Agency (CIA ), known informally as the Agency and historically as the Company, is a civilian foreign intelligence service of the federal government of the United States, officially tasked with gathering, processing, ...

Director Allen Dulles to reunite Erica Wallach with her family in 1957.

Wallach's memoir of her experiences, ''Light at Midnight'', was published in 1967.

Death of Stalin

After Soviet Premier

Joseph Stalin died

Death is the irreversible cessation of all biological functions that sustain an organism. For organisms with a brain, death can also be defined as the irreversible cessation of functioning of the whole brain, including brainstem, and brain ...

inside his

Kuntsevo Dacha on 5 March 1953, the Central Committee of the

East German Socialist Unity Party met in a special session and eulogized the

dictator

A dictator is a political leader who possesses absolute power. A dictatorship is a state ruled by one dictator or by a small clique. The word originated as the title of a Roman dictator elected by the Roman Senate to rule the republic in time ...

as the "great friend of Germany who was always an advisor of and help to our people."

Two months later, on 5 May 1953, the SED's General Secretary,

Walter Ulbricht, and the rest of the leadership increased work quotas by 10%. They also decided to rename

Chemnitz Karl-Marx-Stadt

Chemnitz (; from 1953 to 1990: Karl-Marx-Stadt , ) is the third-largest city in the German state of Saxony after Leipzig and Dresden. It is the 28th largest city of Germany as well as the fourth largest city in the area of former East Germ ...

and to institute the

Order of Karl Marx as the GDR's highest award.

[Koehler (1999), pages 58–59.]

Two weeks later, Mielke accused "a group of Party officials" of "plotting against the leadership", which "resulted in more expulsions from the Politburo and the Central Committee."

East German uprising of 1953

Discontent among factory workers about a 10% increase of work quotas without a corresponding wage hike boiled over. On 16 June 1953, nearly one hundred construction workers gathered before work for a protest meeting at

Stalinallee

Karl-Marx-Allee ( en, Karl Marx Alley) is a monumental socialist boulevard built by the GDR between 1952 and 1960 in Berlin Friedrichshain and Mitte. Today the boulevard is named after Karl Marx. It should not be confused with the ''Karl-Marx- ...

, in

East Berlin. Words spread rapidly to other construction sites and hundreds of men and women joined the rally, which marched to the

House of Ministries. The protesters chanted slogans for five hours, demanding to speak to

Walter Ulbricht and

Otto Grotewohl. Only Heavy Industry Minister

Fritz Selbmann

Friedrich Wilhelm "Fritz" Selbmann (29 September 1899 – 26 January 1975) was a German Communist politician and writer who served as a member of the national parliament (Reichstag) during 1932/33.

He spent the twelve Nazi years first in pris ...

and Professor

Robert Havemann, president of the GDR Peace Council, emerged. Their speech, however, was answered with jeers and the Ministers retreated into the heavily armed building. The regular and the

Kasernierte Volkspolizei were summoned from their barracks, but made no move to attack the protesters, who returned to Stalinallee, where a

general strike was called.

[Koehler (1999), page 59.]

Following

West Germany

West Germany is the colloquial term used to indicate the Federal Republic of Germany (FRG; german: Bundesrepublik Deutschland , BRD) between its formation on 23 May 1949 and the German reunification through the accession of East Germany on 3 ...

's Federal Minister for All-German Questions

Jakob Kaiser's admonition in a late night broadcast to East Germans to shy away from provocations,

RIAS, starting with its 11 pm news broadcast, and from then on in hourly intermissions, repeated the workers' demand to continue the strike the next day, calling specifically for all East Berliners to participate in a demo at 7am on the 17th at

Strausberger Platz

The Strausberger Platz is a large urban square in the Berlin district of Friedrichshain-Kreuzberg and marks the border to the district of Mitte. It is connected via Karl-Marx-Allee with Alexanderplatz and via ''Lichtenberger Straße'' with the '' ...

.

The following day, 17 June 1953, more that 100,000 protesters took to the streets of

East Berlin. More than 400,000 protesters also took to the streets in other cities and towns throughout the

German Democratic Republic

German(s) may refer to:

* Germany (of or related to)

** Germania (historical use)

* Germans, citizens of Germany, people of German ancestry, or native speakers of the German language

** For citizens of Germany, see also German nationality law

**G ...

. Everywhere, the demands were the same:

free elections

An election is a formal group decision-making process by which a population chooses an individual or multiple individuals to hold public office.

Elections have been the usual mechanism by which modern representative democracy has operated ...

by

secret ballot.

Outside of Berlin, the main centres of the protests included the industrial region around

Halle Halle may refer to:

Places Germany

* Halle (Saale), also called Halle an der Saale, a city in Saxony-Anhalt

** Halle (region), a former administrative region in Saxony-Anhalt

** Bezirk Halle, a former administrative division of East Germany

** Hal ...

,

Merseburg, and

Bitterfeld, as well as middle-size towns like

Jena

Jena () is a German city and the second largest city in Thuringia. Together with the nearby cities of Erfurt and Weimar, it forms the central metropolitan area of Thuringia with approximately 500,000 inhabitants, while the city itself has a po ...

,

Görlitz, and

Brandenburg

Brandenburg (; nds, Brannenborg; dsb, Bramborska ) is a state in the northeast of Germany bordering the states of Mecklenburg-Vorpommern, Lower Saxony, Saxony-Anhalt, and Saxony, as well as the country of Poland. With an area of 29,480 squ ...

. No more than 25,000 people participated in strikes and demonstrations in

Leipzig

Leipzig ( , ; Upper Saxon: ) is the most populous city in the German state of Saxony. Leipzig's population of 605,407 inhabitants (1.1 million in the larger urban zone) as of 2021 places the city as Germany's eighth most populous, as ...

, but there were 32,000 in

Magdeburg, 43,000 in

Dresden

Dresden (, ; Upper Saxon: ''Dräsdn''; wen, label= Upper Sorbian, Drježdźany) is the capital city of the German state of Saxony and its second most populous city, after Leipzig. It is the 12th most populous city of Germany, the fourth ...

, 53,000 in

Potsdam – and in

Halle Halle may refer to:

Places Germany

* Halle (Saale), also called Halle an der Saale, a city in Saxony-Anhalt

** Halle (region), a former administrative region in Saxony-Anhalt

** Bezirk Halle, a former administrative division of East Germany

** Hal ...

, a figure close to 100,000.

In

West Berlin, the American

radio station

Radio broadcasting is transmission of audio (sound), sometimes with related metadata, by radio waves to radio receivers belonging to a public audience. In terrestrial radio broadcasting the radio waves are broadcast by a land-based radio ...

RIAS and several other West German stations reported on the protests and on plans for a general strike. As East Germans listened to the broadcasts, 267,000 workers at State-owned plants in 304 cities and towns joined the general strike. In 24 towns, outraged East Germans stormed the Stasi's prisons and freed between 2,000 and 3,000 political prisoners.

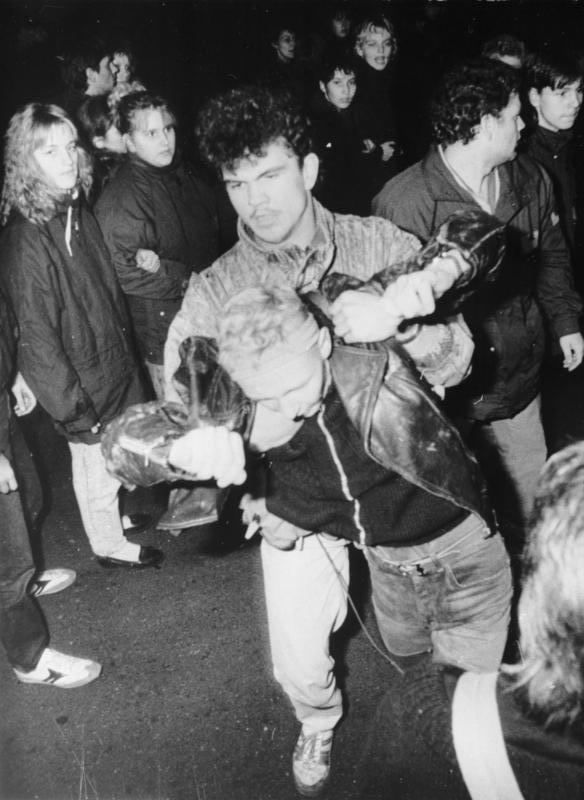

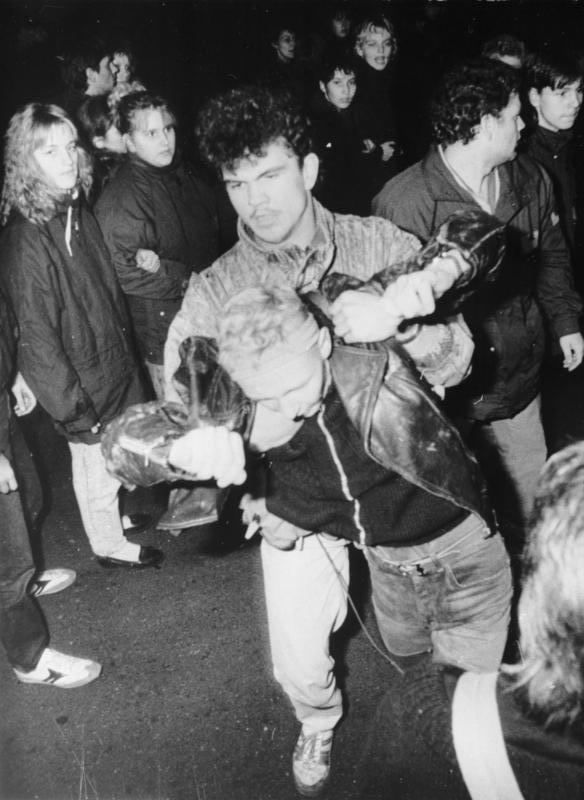

In response to orders, the

Soviet Occupation Forces, the

Stasi and the

Kasernierte Volkspolizei went on the attack. Bloody street battles ensued and hundreds of policemen defected to the side of the protesters. Both police and Stasi stations were overrun and some government offices were sacked. The Party leadership retreated into a fortified compound in the

Pankow district of East Berlin.

At noon, the Soviet authorities terminated all tram and metro traffic into the Eastern sector and all but closed the sector borders to

West Berlin to prevent more demonstrators from reaching the city centre. An hour later, they declared

martial law

Martial law is the imposition of direct military control of normal civil functions or suspension of civil law by a government, especially in response to an emergency where civil forces are overwhelmed, or in an occupied territory.

Use

Martia ...

in

East Berlin.

The repression took place outside East Berlin police HQ – where Soviet tanks opened fire on "the insurgents".

According to John Koehler, "... by late afternoon, Soviet tanks accompanied by Infantry and

MVD troops had rolled into East Berlin and other cities in the

Soviet Zone. This made the people even angrier. At Berlin's

Potsdamer Platz, which bordered on the

American Sector, irate protesters ignored machine gun fire and the menacing barrels of tank guns. They ripped

cobblestones from the streets and hurled them at the tanks."

Fighting between the

Red Army

The Workers' and Peasants' Red Army (Russian language, Russian: Рабо́че-крестья́нская Кра́сная армия),) often shortened to the Red Army, was the army and air force of the Russian Soviet Federative Socialist R ...

(and later GDR police) and the demonstrators persisted into the afternoon and night. In some cases, the tanks and the soldiers fired directly into the crowds.

Overnight, the Soviets (and the Stasi) started to arrest hundreds of people. Ultimately, up to 10,000 people were detained and at least 20, probably as many as 40, people were executed, including Red Army soldiers who refused to obey orders. With the SED leadership effectively paralysed at the Soviet headquarters in

Karlshorst

Karlshorst (, ; ; literally meaning ''Karl's nest'') is a locality in the borough of Lichtenberg in Berlin. Located there are a harness racing track and the Hochschule für Technik und Wirtschaft Berlin (''HTW''), the largest University of Ap ...

, control of the city passed to the Soviets.

In honor of the uprising,

West Germany

West Germany is the colloquial term used to indicate the Federal Republic of Germany (FRG; german: Bundesrepublik Deutschland , BRD) between its formation on 23 May 1949 and the German reunification through the accession of East Germany on 3 ...

established 17 June as a

national holiday, called

Day of German Unity. The extension of the ''

Unter den Linden'' boulevard to the west of the

Brandenburg Gate, formerly called ''Charlottenburger Chaussee'', was also renamed ''

Straße des 17. Juni'' ("17 June Street") in honor of the uprising.

According to John Koehler, "Provisional prison camps were set up to hold the thousands of Stasi victims. Nearly 1,500 persons were sentenced in secret trials to long prison terms. On 24 June, Mielke issued a terse announcement that one Stasi officer, nineteen demonstrators, and two bystanders had been killed during the uprising. He did not say how many were victims of official

lynching. The numbers of the wounded were given as 191 policemen, 126 demonstrators, and 61 bystanders."

[Koehler (1999), page 60.]

Also according to Koehler, "Calm returned to the streets of the Soviet Zone, yet escapes to the West continued at a high rate. Of the 331,390 who fled in 1953, 8,000 were members of the Kasernierte Volkspolizei, the barracked people's police units, which were actually the secret cadre of the future East German Army. Also among the escapees were 2,718 members and candidates of the SED, the ruling Party."

The Khrushchev thaw

Purges

Alarmed by the uprising,

Lavrenty Beria

Lavrentiy Pavlovich Beria (; rus, Лавре́нтий Па́влович Бе́рия, Lavréntiy Pávlovich Bériya, p=ˈbʲerʲiə; ka, ლავრენტი ბერია, tr, ; – 23 December 1953) was a Georgian Bolshevik ...

, the

First Deputy Premier of the Soviet Union and head of the

Ministry of Internal Affairs, personally travelled from

Moscow

Moscow ( , US chiefly ; rus, links=no, Москва, r=Moskva, p=mɐskˈva, a=Москва.ogg) is the capital and largest city of Russia. The city stands on the Moskva River in Central Russia, with a population estimated at 13.0 million ...

to East Berlin. He conferred with Stasi Minister