English parliament on:

[Wikipedia]

[Google]

[Amazon]

The Parliament of England was the

Montfort's scheme was later formally adopted by

Montfort's scheme was later formally adopted by

One of the moments that marked the emergence of parliament as a true institution in England was the deposition of Edward II in January 1327. Even though it is debatable whether

One of the moments that marked the emergence of parliament as a true institution in England was the deposition of Edward II in January 1327. Even though it is debatable whether

During the reign of the Tudor monarchs, it is often argued that the modern structure of the English Parliament began to be created. The Tudor monarchy, according to historian

During the reign of the Tudor monarchs, it is often argued that the modern structure of the English Parliament began to be created. The Tudor monarchy, according to historian

Parliament had not always submitted to the wishes of the Tudor monarchs. But parliamentary criticism of the monarchy reached new levels in the 17th century. When the last Tudor monarch, Elizabeth I, died in 1603, King James VI of Scotland came to power as King James I, founding the Stuart monarchy.

In 1628, alarmed by the arbitrary exercise of royal power, the House of Commons submitted to

Parliament had not always submitted to the wishes of the Tudor monarchs. But parliamentary criticism of the monarchy reached new levels in the 17th century. When the last Tudor monarch, Elizabeth I, died in 1603, King James VI of Scotland came to power as King James I, founding the Stuart monarchy.

In 1628, alarmed by the arbitrary exercise of royal power, the House of Commons submitted to

Virtual Shropshire

*

Birth of the English Parliament.

UK Parliament

British Library

National Archives {{DEFAULTSORT:Parliament of England 1707 disestablishments in Great Britain

legislature

A legislature is an assembly with the authority to make laws for a political entity such as a country or city. They are often contrasted with the executive and judicial powers of government.

Laws enacted by legislatures are usually known ...

of the Kingdom of England

The Kingdom of England (, ) was a sovereign state on the island of Great Britain from 12 July 927, when it emerged from various Anglo-Saxon kingdoms, until 1 May 1707, when it united with Scotland to form the Kingdom of Great Britain.

On ...

from the 13th century until 1707 when it was replaced by the Parliament of Great Britain

The Parliament of Great Britain was formed in May 1707 following the ratification of the Acts of Union by both the Parliament of England and the Parliament of Scotland. The Acts ratified the treaty of Union which created a new unified Kingdo ...

. Parliament evolved from the great council of bishops

A bishop is an ordained clergy member who is entrusted with a position of authority and oversight in a religious institution.

In Christianity, bishops are normally responsible for the governance of dioceses. The role or office of bishop is ca ...

and peers that advised the English monarch. Great councils were first called Parliaments during the reign of Henry III (). By this time, the king required Parliament's consent to levy taxation.

Originally a unicameral

Unicameralism (from ''uni''- "one" + Latin ''camera'' "chamber") is a type of legislature, which consists of one house or assembly, that legislates and votes as one.

Unicameral legislatures exist when there is no widely perceived need for multi ...

body, a bicameral

Bicameralism is a type of legislature, one divided into two separate assemblies, chambers, or houses, known as a bicameral legislature. Bicameralism is distinguished from unicameralism, in which all members deliberate and vote as a single gr ...

Parliament emerged when its membership was divided into the House of Lords

The House of Lords, also known as the House of Peers, is the upper house of the Parliament of the United Kingdom. Membership is by appointment, heredity or official function. Like the House of Commons, it meets in the Palace of Westminst ...

and House of Commons

The House of Commons is the name for the elected lower house of the bicameral parliaments of the United Kingdom and Canada. In both of these countries, the Commons holds much more legislative power than the nominally upper house of parliament. T ...

, which included knights of the shire and burgesses. During Henry IV's time on the throne, the role of Parliament expanded beyond the determination of taxation policy to include the "redress of grievances," which essentially enabled English citizens to petition the body to address complaints in their local towns and counties. By this time, citizens were given the power to vote to elect their representatives—the burgesses—to the House of Commons.

Over the centuries, the English Parliament progressively limited the power of the English monarchy

The monarchy of the United Kingdom, commonly referred to as the British monarchy, is the constitutional form of government by which a hereditary sovereign reigns as the head of state of the United Kingdom, the Crown Dependencies (the Bailiw ...

, a process that arguably culminated in the English Civil War

The English Civil War (1642–1651) was a series of civil wars and political machinations between Parliamentarians (" Roundheads") and Royalists led by Charles I (" Cavaliers"), mainly over the manner of England's governance and issues of r ...

and the High Court of Justice for the trial of Charles I

The High Court of Justice was the court established by the Rump Parliament to try Charles I, King of England, Scotland and Ireland. Even though this was an ''ad hoc'' tribunal that was specifically created for the purpose of trying the king, it ...

.

Predecessors (pre-13th century)

Witan

The origins of Parliament can be traced to the 10th century when a unifiedKingdom of England

The Kingdom of England (, ) was a sovereign state on the island of Great Britain from 12 July 927, when it emerged from various Anglo-Saxon kingdoms, until 1 May 1707, when it united with Scotland to form the Kingdom of Great Britain.

On ...

was forged from several smaller kingdoms. In Anglo-Saxon England

Anglo-Saxon England or Early Medieval England, existing from the 5th to the 11th centuries from the end of Roman Britain until the Norman conquest in 1066, consisted of various Anglo-Saxon kingdoms until 927, when it was united as the Kingdom of ...

, the king would hold deliberative assemblies of nobles

Nobility is a social class found in many societies that have an aristocracy. It is normally ranked immediately below royalty. Nobility has often been an estate of the realm with many exclusive functions and characteristics. The character ...

and prelate

A prelate () is a high-ranking member of the Christian clergy who is an ordinary or who ranks in precedence with ordinaries. The word derives from the Latin , the past participle of , which means 'carry before', 'be set above or over' or 'pre ...

s called witans. These assemblies numbered anywhere from twenty-five to hundreds of participants, including bishop

A bishop is an ordained clergy member who is entrusted with a position of authority and oversight in a religious institution.

In Christianity, bishops are normally responsible for the governance of dioceses. The role or office of bishop is ...

s, abbot

Abbot is an ecclesiastical title given to the male head of a monastery in various Western religious traditions, including Christianity. The office may also be given as an honorary title to a clergyman who is not the head of a monastery. Th ...

s, ealdormen

Ealdorman (, ) was a term in Anglo-Saxon England which originally applied to a man of high status, including some of royal birth, whose authority was independent of the king. It evolved in meaning and in the eighth century was sometimes applied ...

, and thegns. Witans met regularly during the three feasts of Christmas

Christmas is an annual festival commemorating the birth of Jesus Christ, observed primarily on December 25 as a religious and cultural celebration among billions of people around the world. A feast central to the Christian liturgical year ...

, Easter

Easter,Traditional names for the feast in English are "Easter Day", as in the '' Book of Common Prayer''; "Easter Sunday", used by James Ussher''The Whole Works of the Most Rev. James Ussher, Volume 4'') and Samuel Pepys''The Diary of Samue ...

and Whitsun and at other times. In the past, kings interacted with their nobility through royal itineration, but the new kingdom's size made that impractical. Having nobles come to the king for witans was an important alternative to maintain control of the realm.

Witans served several functions. They appear to have had a role in electing kings, especially in times when the succession was disputed. They were theatrical displays of kingship in that they coincided with crown-wearings. They were also forums for receiving petitions and building consensus among the magnates. Kings dispensed patronage

Patronage is the support, encouragement, privilege, or financial aid that an organization or individual bestows on another. In the history of art, arts patronage refers to the support that kings, popes, and the wealthy have provided to artists su ...

, such as granting bookland, and these were recorded in charters witnessed and consented to by those in attendance. Appointments to offices, such as to bishoprics or ealdormanries, were also made during witans. In addition, important political decisions were made in consultation with witans, such as going to war and making treaties. Witans also helped the king to produce Anglo-Saxon law codes and acted as a court for important cases (such as those involving the king or important magnates).

Magnum Concilium

After theNorman Conquest

The Norman Conquest (or the Conquest) was the 11th-century invasion and occupation of England by an army made up of thousands of Norman, Breton, Flemish, and French troops, all led by the Duke of Normandy, later styled William the Conq ...

of 1066, William the Conqueror

William I; ang, WillelmI (Bates ''William the Conqueror'' p. 33– 9 September 1087), usually known as William the Conqueror and sometimes William the Bastard, was the first Norman king of England, reigning from 1066 until his death in 10 ...

() continued the tradition of summoning assemblies of magnates to consider national affairs, conduct state trials, and make laws; although legislation now took the form of writ

In common law, a writ (Anglo-Saxon ''gewrit'', Latin ''breve'') is a formal written order issued by a body with administrative or judicial jurisdiction; in modern usage, this body is generally a court. Warrants, prerogative writs, subpoenas, a ...

s rather than law codes. These assemblies were called (Latin

Latin (, or , ) is a classical language belonging to the Italic languages, Italic branch of the Indo-European languages. Latin was originally a dialect spoken in the lower Tiber area (then known as Latium) around present-day Rome, but through ...

for "great council"). While kings had access to familiar counsel, this private advice could not replace the need for consensus building, and overreliance on familiar counsel could lead to political instability. Great councils were valued because they "carried fewer political risks, allowed responsibility to be more broadly shared, and drew a larger body of prelates and magnates into the making of decisions".

The council's members were the king's tenants-in-chief. The greater tenants, such as archbishops, bishops, abbots, earls

Earl () is a rank of the nobility in the United Kingdom. The title originates in the Old English word ''eorl'', meaning "a man of noble birth or rank". The word is cognate with the Scandinavian form ''jarl'', and meant "chieftain", particular ...

, and barons were summoned by individual writ, but sometimes lesser tenants were also summoned by sheriffs

A sheriff is a government official, with varying duties, existing in some countries with historical ties to England where the office originated. There is an analogous, although independently developed, office in Iceland that is commonly trans ...

. Politics in the period following the Conquest (1066–1154) was dominated by about 200 wealthy laymen

In religious organizations, the laity () consists of all members who are not part of the clergy, usually including any non-ordained members of religious orders, e.g. a nun or a lay brother.

In both religious and wider secular usage, a laype ...

, in addition to the king and leading clergy. High-ranking churchmen (such as bishops and abbots) were important magnates in their own right. According to Domesday Book

Domesday Book () – the Middle English spelling of "Doomsday Book" – is a manuscript record of the "Great Survey" of much of England and parts of Wales completed in 1086 by order of King William I, known as William the Conqueror. The manusc ...

, the English church

The Church of England (C of E) is the established Christian church in England and the mother church of the international Anglican Communion. It traces its history to the Christian church recorded as existing in the Roman province of Britain ...

owned between 25% and 33% of all land in 1066.

Traditionally, the great council was not involved in levying taxes. Royal finances derived from land revenues, feudal aids and incidents, and the profits of royal justice. This changed near the end of Henry II's reign (1154–1189) due to the levying of national taxation to finance the Third Crusade

The Third Crusade (1189–1192) was an attempt by three European monarchs of Western Christianity ( Philip II of France, Richard I of England and Frederick I, Holy Roman Emperor) to reconquer the Holy Land following the capture of Jerusalem by ...

, ransom Richard I, and pay for the series of Anglo-French wars

The Anglo-French Wars were a series of conflicts between England (and after 1707, Britain) and France, including:

Middle Ages High Middle Ages

* Anglo-French War (1109–1113) – first conflict between the Capetian Dynasty and the House of Norma ...

fought between the Plantagenet and Capetian dynasties. In 1188, Henry II set a precedent when he applied to the great council for consent to levy the Saladin tithe.

The burden imposed by national taxation and the likelihood of resistance made consent politically necessary. It was convenient for kings to present the great council of magnates as a representative body capable of consenting on behalf of all within the kingdom. Increasingly, the kingdom was described as the (Latin for "community of the realm") and the barons as their natural representatives. But this development also created more conflict between kings and the baronage

{{English Feudalism

In England, the ''baronage'' was the collectively inclusive term denoting all members of the feudal nobility, as observed by the constitutional authority Edward Coke. It was replaced eventually by the term ''peerage''.

Origi ...

as the latter attempted to defend what they considered the rights belonging to the king's subjects.

King John () alienated the barons by his partiality in dispensing justice, heavy financial demands and abusing his right to feudal incidents, reliefs, and aids. In 1215, the barons forced John to abide by a charter of liberties similar to charters issued by earlier kings (see Charter of Liberties

The Charter of Liberties, also called the Coronation Charter, or Statutes of the Realm, was a written proclamation by Henry I of England, issued upon his accession to the throne in 1100. It sought to bind the King to certain laws regarding the ...

). Known as Magna Carta

(Medieval Latin for "Great Charter of Freedoms"), commonly called (also ''Magna Charta''; "Great Charter"), is a royal charter of rights agreed to by King John of England at Runnymede, near Windsor, on 15 June 1215. First drafted by t ...

(Latin for "Great Charter"), the charter was based on three assumptions important to the later development of Parliament:

# the king was subject to the law

# the king could only make law and raise taxation (except customary feudal dues) with the consent of the community of the realm

# that the obedience owed by subjects to the king was conditional and not absolute

While the clause stipulating no taxation "without the common counsel" was deleted from later reissues, it was nevertheless adhered to by later kings. Magna Carta transformed the feudal obligation to advise the king into a right to consent. While it was the barons who made the charter, the liberties guaranteed within it were granted to "all the free men of our realm". The charter was promptly repudiated by the king, which led to the First Barons' War, but Magna Carta would gain the status of fundamental law during the reign of John's successor.

Early development (1216–1307)

Henry III and the first parliaments

Henry III (r. 1216–1272) became king at nine years old after his father, King John, died during the First Barons' War. During the king's minority, England was ruled by a regency government that relied heavily on great councils to legitimise its actions. Great councils even consented to the appointment of royal ministers, an action that normally was considered aroyal prerogative

The royal prerogative is a body of customary authority, privilege and immunity, recognized in common law and, sometimes, in civil law jurisdictions possessing a monarchy, as belonging to the sovereign and which have become widely vested in th ...

. Historian John Maddicott writes that the "effect of the minority was thus to make the great council an indispensable part of the country's government ndto give it a degree of independent initiative and authority which central assemblies had never previously possessed".

The regency government officially ended when Henry turned sixteen in 1223, and the magnates demanded the adult king confirm previous grants of Magna Carta made in 1216 and 1217 to ensure their legality. At the same time, the king needed money to defend his possessions in Poitou and Gascony

Gascony (; french: Gascogne ; oc, Gasconha ; eu, Gaskoinia) was a province of the southwestern Kingdom of France that succeeded the Duchy of Gascony (602–1453). From the 17th century until the French Revolution (1789–1799), it was part ...

from a French invasion. At a great council in 1225, a deal was reached that saw Magna Carta and the Charter of the Forest reissued in return for a fifteenth tax on "movables" (personal property and rents). This set a precedent that taxation was granted in return for the redress of grievances.

In the mid-1230s, the word ''parliament'' came into common use for meetings of the great council. The word ''parliament'' comes from the French

French (french: français(e), link=no) may refer to:

* Something of, from, or related to France

** French language, which originated in France, and its various dialects and accents

** French people, a nation and ethnic group identified with Franc ...

first used in the late 11th century with the meaning of parley or conversation (compare to the of Ancien Régime

''Ancien'' may refer to

* the French word for " ancient, old"

** Société des anciens textes français

* the French for "former, senior"

** Virelai ancien

** Ancien Régime

** Ancien Régime in France

{{disambig ...

France). It was in Parliament, and with its assent, that the king declared law and where national affairs were deliberated. It granted or refused the king's request for extraordinary taxation (as opposed to ordinary feudal or customary taxes), and it served as England's highest court of justice.

After the 1230s, the normal meeting place for Parliament was fixed at Westminster

Westminster is an area of Central London, part of the wider City of Westminster.

The area, which extends from the River Thames to Oxford Street, has many visitor attractions and historic landmarks, including the Palace of Westminster, B ...

. Parliament tended to meet according to the legal year so that the courts were also in session. It often met in January or February for the Hilary term, in April or May for the Easter term, in July, and in October for the Michaelmas term. In the 13th century, most parliaments had between forty to eighty attendees. Meetings of Parliament always included:

* the king

* chief ministers and other ministers ( great officers of state, justices of the King's Bench and Common Bench

The Court of Common Pleas, or Common Bench, was a common law court in the English legal system that covered "common pleas"; actions between subject and subject, which did not concern the king. Created in the late 12th to early 13th century af ...

, and barons of the exchequer

The Barons of the Exchequer, or ''barones scaccarii'', were the judges of the English court known as the Exchequer of Pleas. The Barons consisted of a Chief Baron of the Exchequer and several puisne (''inferior'') barons. When Robert Shute was a ...

)

* members of the king's council

* ecclesiastical magnates (archbishops, bishops, abbots, priors)

* lay magnates (earls and barons)

Other groups were occasionally summoned. The lesser tenants-in-chief (or knights) were regularly summoned to consent to taxation; though, they were summoned on the basis of their status as tenants of the Crown rather than as representatives of a wider class. The lower clergy ( deans, cathedral priors, archdeacon

An archdeacon is a senior clergy position in the Church of the East, Chaldean Catholic Church, Syriac Orthodox Church, Anglican Communion, St Thomas Christians, Eastern Orthodox churches and some other Christian denominations, above that of mo ...

s, parish priest

A parish is a territorial entity in many Christian denominations, constituting a division within a diocese. A parish is under the pastoral care and clerical jurisdiction of a priest, often termed a parish priest, who might be assisted by one or ...

s) were occasionally summoned when papal taxation was on the agenda. Beginning around the 1220s, the concept of representation, summarised in the Roman law

Roman law is the legal system of ancient Rome, including the legal developments spanning over a thousand years of jurisprudence, from the Twelve Tables (c. 449 BC), to the '' Corpus Juris Civilis'' (AD 529) ordered by Eastern Roman emperor J ...

maxim (Latin for "what touches all should be approved by all"), gained new importance among the clergy, and they began choosing proctor

Proctor (a variant of '' procurator'') is a person who takes charge of, or acts for, another.

The title is used in England and some other English-speaking countries in three principal contexts:

* In law, a proctor is a historical class of lawy ...

s to represent them at church assemblies and, when summoned, at Parliament.

Tension over ministers and finances

In 1232, Peter des Roches became the king's chief minister. His nephew,Peter de Rivaux

Peter de Rivaux or Peter de Rivallis (died 1262) was an influential Poitevin courtier at the court of Henry III of England. He was related to Peter des Roches, being a nephew (or possibly a son).

From early in his life he was connected to the c ...

, accumulated a large number of offices, including keeper of the privy seal and keeper of the wardrobe; yet, these appointments were not approved by the magnates as had become customary during the regency government. Under Roches, the government revived practices used during King John's reign and that had been condemned in Magna Carta, such as arbitrary disseisins, revoking perpetual rights granted in royal charters, depriving heirs of their inheritances, and marrying heiresses to foreigners.

Both Roches and Rivaux were foreigners from Poitou. The rise of a royal administration controlled by foreigners and dependent solely on the king stirred resentment among the magnates, who felt excluded from power. Several barons rose in rebellion, and the bishops intervened to persuade the king to change ministers. At a great council in April 1234, the king agreed to remove Rivaux and other ministers. This was the first occasion in which a king was forced to change his ministers by a great council or parliament. The struggle between king and Parliament over ministers became a permanent feature of English politics.

Thereafter, the king ruled in concert with an active Parliament, which considered matters related to foreign policy, taxation, justice, administration, and legislation. January 1236 saw the passage of the Statute of Merton

The Statute of Merton or Provisions of Merton (Latin: ''Provisiones de Merton'', or ''Stat. Merton''), sometimes also known as the Ancient Statute of Merton, was a statute passed by the Parliament of England in 1235 during the reign of Henry II ...

, the first English statute

A statute is a formal written enactment of a legislative authority that governs the legal entities of a city, state, or country by way of consent. Typically, statutes command or prohibit something, or declare policy. Statutes are rules made by ...

. Among other things, the law continued barring bastards from inheritance. Significantly, the language of the preamble describes the legislation as "provided" by the magnates and "conceded" by the king, which implies that this was not simply a royal measure consented to by the barons. In 1237, Henry asked Parliament for a tax to fund his sister Isabella's dowry. The barons were unenthusiastic, but they granted the funds in return for the king's promise to reconfirm Magna Carta, add three magnates to his personal council, limit the royal prerogative of purveyance, and protect land tenure rights.

But Henry was adamant that three concerns were exclusively within his royal prerogative: family and inheritance matters, patronage, and appointments. Important decisions were made without consulting Parliament, such as in 1254 when the king accepted the throne of the Kingdom of Sicily

The Kingdom of Sicily ( la, Regnum Siciliae; it, Regno di Sicilia; scn, Regnu di Sicilia) was a state that existed in the south of the Italian Peninsula and for a time the region of Ifriqiya from its founding by Roger II of Sicily in 1130 un ...

for his younger son, Edmund Crouchback. He also clashed with Parliament over appointments to the three great offices of chancellor

Chancellor ( la, cancellarius) is a title of various official positions in the governments of many nations. The original chancellors were the of Roman courts of justice—ushers, who sat at the or lattice work screens of a basilica or law cou ...

, justiciar

Justiciar is the English form of the medieval Latin term ''justiciarius'' or ''justitiarius'' ("man of justice", i.e. judge). During the Middle Ages in England, the Chief Justiciar (later known simply as the Justiciar) was roughly equivalent ...

, and treasurer

A treasurer is the person responsible for running the treasury of an organization. The significant core functions of a corporate treasurer include cash and liquidity management, risk management, and corporate finance.

Government

The treasury ...

. The barons believed these three offices should be restraints on royal misgovernment, but the king promoted minor officials within the royal household who owed their loyalty exclusively to him.

Parliament's main tool against the king was to deny consent to national taxation, which they consistently withheld after 1237. Nevertheless, this proved ineffective at restraining the king as he was still able to raise lesser amounts of revenue from sources that did not require parliamentary consent:

* county farms (the fixed sum paid annually by sheriffs for the privilege of administering and profiting from royal lands in their counties)

* profits from the eyre

* tallage on the royal demesne

A demesne ( ) or domain was all the land retained and managed by a lord of the manor under the feudal system for his own use, occupation, or support. This distinguished it from land sub-enfeoffed by him to others as sub-tenants. The concept or ...

, the towns, foreign merchants, and most importantly English Jews

The history of the Jews in England goes back to the reign of William the Conqueror. Although it is likely that there had been some Jewish presence in the Roman period, there is no definitive evidence, and no reason to suppose that there was an ...

* scutage

* feudal dues and fines

* profits from wardship

In law, a ward is a minor or incapacitated adult placed under the protection of a legal guardian or government entity, such as a court. Such a person may be referenced as a "ward of the court".

Overview

The wardship jurisdiction is an ancient ...

, escheat, and vacant episcopal sees

In 1253, while fighting in Gascony, Henry requested men and money to resist an anticipated attack from Alfonso X of Castile

Alfonso X (also known as the Wise, es, el Sabio; 23 November 1221 – 4 April 1284) was King of Castile, León and Galicia from 30 May 1252 until his death in 1284. During the election of 1257, a dissident faction chose him to be king of Ger ...

. In a January 1254 Parliament, the bishops themselves promised an aid but would not commit the rest of the clergy. Likewise, the barons promised to assist the king if he was attacked but would not commit the rest of the laity to pay money. For this reason, the lower clergy of each diocese

In church governance, a diocese or bishopric is the ecclesiastical district under the jurisdiction of a bishop.

History

In the later organization of the Roman Empire, the increasingly subdivided provinces were administratively associ ...

elected proctors at church synods

A synod () is a council of a Christian denomination, usually convened to decide an issue of doctrine, administration or application. The word '' synod'' comes from the meaning "assembly" or "meeting" and is analogous with the Latin word mean ...

, and each county elected two knights of the shire. These representatives were summoned to Parliament in April 1254 to consent to taxation. The men elected as shire knights were prominent landholders with experience in local government and as soldiers. They were elected by barons, other knights, and probably freeholders of sufficient standing, illustrating the increasing importance of the gentry

Gentry (from Old French ''genterie'', from ''gentil'', "high-born, noble") are "well-born, genteel and well-bred people" of high social class, especially in the past.

Word similar to gentle imple and decentfamilies

''Gentry'', in its widest c ...

as a class. Summoning elected knights to Parliament would not become a regular occurrence until the reign of Edward I. However, the events of 1254 reveal that the barons were no longer viewed as the sole representatives of the realm.

Baronial reform movement

By 1258, the relationship between the king and the baronage had reached a breaking point over the "Sicilian Business", in which Henry had promised to pay papal debts in return for the pope's help securing the Sicilian crown for his son, Edmund. At the Oxford Parliament of 1258, reform-minded barons forced a reluctant king to accept a constitutional framework known as the Provisions of Oxford: * The king was to govern according to the advice of an elected council of fifteen barons. * The baronial council appointed royal ministers (justiciar, treasurer, chancellor) to serve for one-year terms. * Parliament met three times a year on theoctave

In music, an octave ( la, octavus: eighth) or perfect octave (sometimes called the diapason) is the interval between one musical pitch and another with double its frequency. The octave relationship is a natural phenomenon that has been refer ...

of Michaelmas

Michaelmas ( ; also known as the Feast of Saints Michael, Gabriel, and Raphael, the Feast of the Archangels, or the Feast of Saint Michael and All Angels) is a Christian festival observed in some Western liturgical calendars on 29 September, a ...

(October 6), Candlemas

Candlemas (also spelled Candlemass), also known as the Feast of the Presentation of Jesus Christ, the Feast of the Purification of the Blessed Virgin Mary, or the Feast of the Holy Encounter, is a Christian holiday commemorating the presenta ...

(February 3), and June 1.

* The barons elected twelve representatives (two bishops, one earl and nine barons) who together with the baronial council could act on legislation and other matters even when Parliament was not in session as "a kind of standing parliamentary committee".

Parliament now met regularly according to a schedule rather than at the pleasure of the king. The reformers hoped that the provisions would ensure parliamentary approval for all major government acts. Under the provisions, Parliament was "established formally (and no longer merely by custom) as the voice of the community".

The theme of reform dominated later parliaments. During the Michaelmas Parliament of 1258, the Ordinance of Sheriffs

Ordinance may refer to:

Law

* Ordinance (Belgium), a law adopted by the Brussels Parliament or the Common Community Commission

* Ordinance (India), a temporary law promulgated by the President of India on recommendation of the Union Cabinet

* ...

was issued as letters patent

Letters patent ( la, litterae patentes) ( always in the plural) are a type of legal instrument in the form of a published written order issued by a monarch, president or other head of state, generally granting an office, right, monopoly, tit ...

that forbade sheriffs from taking bribes. At the Candlemas Parliament of 1259, the baronial council and the twelve representatives enacted the Ordinance of the Magnates

Ordinance may refer to:

Law

* Ordinance (Belgium), a law adopted by the Brussels Parliament or the Common Community Commission

* Ordinance (India), a temporary law promulgated by the President of India on recommendation of the Union Cabinet

* ...

. In this ordinance, the barons promised to observe Magna Carta and other reforming legislation. They also required their own bailiffs to observe similar rules as those of royal sheriffs, and the justiciar was given power to correct abuses of their officials. The Michaelmas Parliament of 1259 enacted the Provisions of Westminster

The Provisions of Westminster of 1259 were part of a series of legislative constitutional reforms that arose out of power struggles between Henry III of England and his barons. The King's failed campaigns in France in 1230 and 1242, and his choic ...

, a set of legal and administrative reforms designed to address grievances of freeholders and even villeins

A villein, otherwise known as ''cottar'' or '' crofter'', is a serf tied to the land in the feudal system. Villeins had more rights and social status than those in slavery, but were under a number of legal restrictions which differentiated them ...

, such as abuses related to the murdrum fine.

Henry III made his first move against the baronial reformers while in France negotiating peace with Louis IX

Louis IX (25 April 1214 – 25 August 1270), commonly known as Saint Louis or Louis the Saint, was King of France from 1226 to 1270, and the most illustrious of the House of Capet, Direct Capetians. He was Coronation of the French monarch, c ...

. Using the excuse of his absence from the realm and Welsh attacks in the marches, Henry ordered the justiciar, Hugh Bigod, to postpone the parliament scheduled for Candlemas 1260. This was an apparent violation of the Provisions of Oxford; however, the provisions were silent on what should happen if the king were outside the kingdom. The king's motive was to prevent the promulgation of further reforms through Parliament. Simon de Montfort, a leader of the baronial reformers, ignored these orders and made plans to hold a parliament in London but was prevented by Bigod. When the king arrived back in England he summoned a parliament which met in July, where Montfort was brought to trial though ultimately cleared of wrongdoing.

In April 1261, the pope released the king from his oath to adhere to the Provisions of Oxford, and Henry publicly renounced the Provisions in May. Most of the barons were willing to let the king reassume power provided he ruled well. By 1262, Henry had regained all of his authority, and Montfort left England. The barons were now divided mainly by age. The elder barons remained loyal to the king, but younger barons coalesced around Montfort, who returned to England in the spring of 1263.

Montfortian parliaments

The royalist barons and rebel barons fought each other in theSecond Barons' War

The Second Barons' War (1264–1267) was a civil war in England between the forces of a number of barons led by Simon de Montfort against the royalist forces of King Henry III, led initially by the king himself and later by his son, the fu ...

. Montfort defeated the king at the Battle of Lewes in 1264 and became the real ruler of England for the next twelve months. Montfort held a parliament in June 1264 to sanction a new form of government and rally support. This parliament was notable for including knights of the shire who were expected to deliberate fully on political matters, not just assent to taxation.

The June Parliament approved a new constitution in which the king's powers were given to a council of nine. The new council was chosen and led by three electors (Montfort, Stephen Bersted, Bishop of Chichester, and Gilbert de Clare, 7th Earl of Gloucester). The electors could replace any of the nine as they saw fit, but the electors themselves could only be removed by Parliament.

Montfort held two other Parliaments during his time in power. The most famous—Simon de Montfort's Parliament

Simon de Montfort's Parliament was an English parliament held from 20 January 1265 until mid-March of the same year, called by Simon de Montfort, a baronial rebel leader.

Montfort had seized power in England following his victory over Henry I ...

—was held in January 1265 amidst threat of a French invasion and unrest throughout the realm. For the first time, burgesses (elected by those residents of boroughs

A borough is an administrative division in various English-speaking countries. In principle, the term ''borough'' designates a self-governing walled town, although in practice, official use of the term varies widely.

History

In the Middle A ...

or towns who held burgage tenure

Burgage is a medieval land term used in Great Britain and Ireland, well established by the 13th century.

A burgage was a town (" borough" or " burgh") rental property (to use modern terms), owned by a king or lord. The property ("burgage teneme ...

, such as wealthy merchants or craftsmen) were summoned along with knights of the shire.

Montfort was killed at the Battle of Evesham

The Battle of Evesham (4 August 1265) was one of the two main battles of 13th century England's Second Barons' War. It marked the defeat of Simon de Montfort, Earl of Leicester, and the rebellious barons by the future King Edward I, who led t ...

in 1265, and Henry was restored to power. In August 1266, Parliament authorised the Dictum of Kenilworth, which nullified everything Montfort had done and removed all restraints on the king. In 1267, some of the reforms contained in the 1259 Provisions of Westminster were revised in the form of the Statute of Marlborough passed in 1267. This was the start of a process of statutory reform that continued into the reign of Henry's successor.

Edward I

Edward I

Edward I (17/18 June 1239 – 7 July 1307), also known as Edward Longshanks and the Hammer of the Scots, was King of England and Lord of Ireland from 1272 to 1307. Concurrently, he ruled the duchies of Aquitaine and Gascony as a vas ...

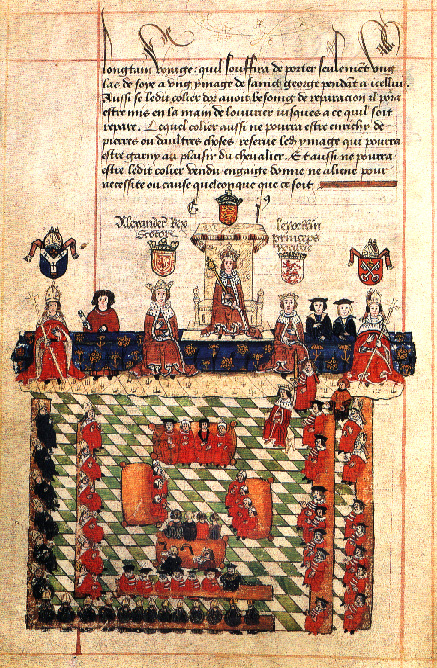

in the so-called " Model Parliament" of 1295. The attendance at parliament of knights and burgesses historically became known as the summoning of "the Commons", a term derived from the Norman French word "commune", literally translated as the "community of the realm".

The role of Parliament in the government of the English kingdom increased due to Edward's determination to unite England, Wales and Scotland under his rule by force. He was also keen to unite his subjects in order to restore his authority and not face rebellion as was his father's fate. Edward therefore encouraged all sectors of society to submit petitions to parliament detailing their grievances in order for them to be resolved. This seemingly gave all of Edward's subjects a potential role in government and this helped Edward assert his authority. Both the Statute of Westminster 1275 and Statute of Westminster 1285

The Statute of Westminster of 1285, also known as the Statute of Westminster II or the Statute of Westminster the Second, like the Statute of Westminster 1275, is a code in itself, and contains the famous clause '' De donis conditionalibus'', one ...

, with the assistance of Robert Burnell

Robert Burnell (sometimes spelled Robert Burnel;Harding ''England in the Thirteenth Century'' p. 159 c. 1239 – 25 October 1292) was an English bishop who served as Lord Chancellor of England from 1274 to 1292. A native of Shropshire, h ...

, codified the existing law in England.

As the number of petitions being submitted to parliament increased, they came to be dealt with, and often ignored, more and more by ministers of the Crown so as not to block the passage of government business through parliament. However, the emergence of petitioning is significant because it is some of the earliest evidence of parliament being used as a forum to address the general grievances of ordinary people. Submitting a petition to parliament is a tradition that continues to this day in the Parliament of the United Kingdom and in most Commonwealth

A commonwealth is a traditional English term for a political community founded for the common good. Historically, it has been synonymous with "republic". The noun "commonwealth", meaning "public welfare, general good or advantage", dates from the ...

realms.

These developments symbolise the fact that parliament and government were by no means the same thing by this point. If monarchs were going to impose their will on their kingdom, they would have to control parliament rather than be subservient to it.

From Edward's reign onwards, the authority of the English Parliament would depend on the strength or weakness of the incumbent monarch. A strong king or queen would wield enough influence to pass their legislation through parliament without much trouble. Some strong monarchs even bypassed it completely, although this was not often possible in the case of financial legislation due to the post-Magna Carta convention of parliament granting taxes. When weak monarchs governed, parliament often became the centre of opposition against them.

The composition of parliaments in this period varied depending on the decisions that needed to be taken in them. The nobility and senior clergy were always summoned. From 1265 onwards, when the monarch needed to raise money through taxes, it was usual for knights and burgesses to be summoned too. However, when the king was merely seeking advice, he often only summoned the nobility and the clergy, sometimes with and sometimes without the knights of the shires. On some occasions the Commons were summoned and sent home again once the monarch was finished with them, allowing parliament to continue without them. It was not until the mid-14th century that summoning representatives of the shires and the boroughs became the norm for all parliaments.

Formal separation of Lords and Commons

One of the moments that marked the emergence of parliament as a true institution in England was the deposition of Edward II in January 1327. Even though it is debatable whether

One of the moments that marked the emergence of parliament as a true institution in England was the deposition of Edward II in January 1327. Even though it is debatable whether Edward II

Edward II (25 April 1284 – 21 September 1327), also called Edward of Caernarfon, was King of England and Lord of Ireland from 1307 until he was deposed in January 1327. The fourth son of Edward I, Edward became the heir apparent to ...

was deposed ''in'' parliament or ''by'' parliament, this remarkable sequence of events consolidated the importance of parliament in the English unwritten constitution. Parliament

In modern politics, and history, a parliament is a legislative body of government. Generally, a modern parliament has three functions: representing the electorate, making laws, and overseeing the government via hearings and inquiries. Th ...

was also crucial in establishing the legitimacy of the king who replaced Edward II: his son Edward III

Edward III (13 November 1312 – 21 June 1377), also known as Edward of Windsor before his accession, was King of England and Lord of Ireland from January 1327 until his death in 1377. He is noted for his military success and for restoring r ...

.

In 1341 the Commons met separately from the nobility and clergy for the first time, creating what was effectively an Upper Chamber and a Lower Chamber, with the knights and burgesses sitting in the latter. This Upper Chamber became known as the House of Lords

The House of Lords, also known as the House of Peers, is the upper house of the Parliament of the United Kingdom. Membership is by appointment, heredity or official function. Like the House of Commons, it meets in the Palace of Westminst ...

from 1544 onward, and the Lower Chamber became known as the House of Commons

The House of Commons is the name for the elected lower house of the bicameral parliaments of the United Kingdom and Canada. In both of these countries, the Commons holds much more legislative power than the nominally upper house of parliament. T ...

, collectively known as the Houses of Parliament

The Palace of Westminster serves as the meeting place for both the House of Commons and the House of Lords, the two houses of the Parliament of the United Kingdom. Informally known as the Houses of Parliament, the Palace lies on the north ban ...

.

The authority of parliament grew under Edward III; it was established that no law could be made, nor any tax levied, without the consent of both Houses and the Sovereign. This development occurred during the reign of Edward III because he was involved in the Hundred Years' War

The Hundred Years' War (; 1337–1453) was a series of armed conflicts between the kingdoms of England and France during the Late Middle Ages. It originated from disputed claims to the French throne between the English House of Plantagen ...

and needed finances. During his conduct of the war, Edward tried to circumvent parliament as much as possible, which caused this edict to be passed.

The Commons came to act with increasing boldness during this period. During the Good Parliament (1376), the Presiding Officer of the lower chamber, Peter de la Mare, complained of heavy taxes, demanded an accounting of the royal expenditures, and criticised the king's management of the military. The Commons even proceeded to impeach some of the king's ministers. The bold Speaker was imprisoned, but was soon released after the death of Edward III.

During the reign of the next monarch, Richard II

Richard II (6 January 1367 – ), also known as Richard of Bordeaux, was King of England from 1377 until he was deposed in 1399. He was the son of Edward the Black Prince, Prince of Wales, and Joan, Countess of Kent. Richard's father ...

, the Commons once again began to impeach errant ministers of the Crown. They insisted that they could not only control taxation, but also public expenditure. Despite such gains in authority, however, the Commons still remained much less powerful than the House of Lords and the Crown.

This period also saw the introduction of a franchise which limited the number of people who could vote in elections for the House of Commons. From 1430 onwards, the franchise was limited to Forty Shilling Freeholders, that is men who owned freehold property worth forty shillings or more. The Parliament of England legislated the new uniform county franchise, in the statute 8 Hen. 6, c. 7. The ''Chronological Table of the Statutes'' does not mention such a 1430 law, as it was included in the Consolidated Statutes as a recital in the Electors of Knights of the Shire Act 1432 (10 Hen. 6, c. 2), which amended and re-enacted the 1430 law to make clear that the resident of a county had to have a forty shilling freehold in that county to be a voter there.

King, Lords and Commons

During the reign of the Tudor monarchs, it is often argued that the modern structure of the English Parliament began to be created. The Tudor monarchy, according to historian

During the reign of the Tudor monarchs, it is often argued that the modern structure of the English Parliament began to be created. The Tudor monarchy, according to historian J. E. Neale

Sir John Ernest Neale (7 December 1890 in Liverpool – 2 September 1975) was an English historian who specialised in Elizabethan and Parliamentary history. From 1927 to 1956, he was the Astor Professor of English History at University Coll ...

, was powerful, and there were often periods of several years when parliament did not sit at all. However, the Tudor monarchs realised that they needed parliament to legitimise many of their decisions, mostly out of a need to raise money through taxation legitimately without causing discontent. Thus they consolidated the state of affairs whereby monarchs would call and close parliament as and when they needed it. However, if monarchs did not call Parliament for several years, it is clear the Monarch did not require Parliament except to perhaps strengthen and provide a mandate for their reforms to Religion which had always been a matter within the Crown's prerogative but would require the consent of the Bishopric and Commons.

By the time of the Tudor monarch Henry VII's 1485 coronation, the monarch was not a member of either the Upper Chamber or the Lower Chamber. Consequently, the monarch would have to make his or her feelings known to Parliament through his or her supporters in both houses. Proceedings were regulated by the presiding officer in either chamber.

From the 1540s the presiding officer in the House of Commons became formally known as the "Speaker

Speaker may refer to:

Society and politics

* Speaker (politics), the presiding officer in a legislative assembly

* Public speaker, one who gives a speech or lecture

* A person producing speech: the producer of a given utterance, especially:

** In ...

", having previously been referred to as the "prolocutor" or "parlour" (a semi-official position, often nominated by the monarch, that had existed ever since Peter de Montfort

Peter de Montfort (or Piers de Montfort) (c. 1205 – 4 August 1265) of Beaudesert Castle was an English magnate, soldier and diplomat. He is the first person recorded as having presided over Parliament as a ''parlour'' or ''prolocutor'', an offi ...

had acted as the presiding officer of the Oxford Parliament of 1258). This was not an enviable job. When the House of Commons was unhappy it was the Speaker who had to deliver this news to the monarch. This began the tradition whereby the Speaker of the House of Commons is dragged to the Speaker's Chair by other members once elected.

A member of either chamber could present a "bill

Bill(s) may refer to:

Common meanings

* Banknote, paper cash (especially in the United States)

* Bill (law), a proposed law put before a legislature

* Invoice, commercial document issued by a seller to a buyer

* Bill, a bird or animal's beak

Pla ...

" to parliament. Bills supported by the monarch were often proposed by members of the Privy Council

A privy council is a body that advises the head of state of a state, typically, but not always, in the context of a monarchic government. The word "privy" means "private" or "secret"; thus, a privy council was originally a committee of the mo ...

who sat in parliament. For a bill to become law it would have to be approved by a majority of both Houses of Parliament before it passed to the monarch for royal assent

Royal assent is the method by which a monarch formally approves an act of the legislature, either directly or through an official acting on the monarch's behalf. In some jurisdictions, royal assent is equivalent to promulgation, while in oth ...

or veto

A veto is a legal power to unilaterally stop an official action. In the most typical case, a president or monarch vetoes a bill to stop it from becoming law. In many countries, veto powers are established in the country's constitution. Veto ...

. The royal veto was applied several times during the 16th and 17th centuries and it is still the right of the monarch of the United Kingdom and Commonwealth realms to veto legislation today, although it has not been exercised since 1707 (today such an exercise might precipitate some form of constitutional crisis

In political science, a constitutional crisis is a problem or conflict in the function of a government that the political constitution or other fundamental governing law is perceived to be unable to resolve. There are several variations to this ...

).

When a bill was enacted into law, this process gave it the approval of each estate of the realm: the King, Lords and Commons. The Parliament of England was far from being a democratically representative institution in this period. It was possible to assemble the entire peerage and senior clergy of the realm in one place to form the estate of the Upper Chamber.

The voting franchise for the House of Commons was small; some historians estimate that it was as little as three per cent of the adult male population; and there was no secret ballot. Elections could therefore be controlled by local grandee

Grandee (; es, Grande de España, ) is an official aristocratic title conferred on some Spanish nobility. Holders of this dignity enjoyed similar privileges to those of the peerage of France during the , though in neither country did they ...

s, because in many boroughs a majority of voters were in some way dependent on a powerful individual, or else could be bought by money or concessions. If these grandees were supporters of the incumbent monarch, this gave the Crown and its ministers considerable influence over the business of parliament.

Many of the men elected to parliament did not relish the prospect of having to act in the interests of others. So a law was enacted, still on the statute book today, whereby it became unlawful for members of the House of Commons to resign their seat unless they were granted a position directly within the patronage of the monarchy (today this latter restriction leads to a legal fiction

A legal fiction is a fact assumed or created by courts, which is then used in order to help reach a decision or to apply a legal rule. The concept is used almost exclusively in common law jurisdictions, particularly in England and Wales.

Deve ...

allowing ''de facto'' resignation despite the prohibition, but nevertheless it is a resignation which needs the permission of the Crown). However, while several elections to parliament in this period would be considered corrupt by modern standards, many elections involved genuine contests between rival candidates, even though the ballot was not secret.

Establishment of permanent seat

It was in this period that thePalace of Westminster

The Palace of Westminster serves as the meeting place for both the House of Commons and the House of Lords, the two houses of the Parliament of the United Kingdom. Informally known as the Houses of Parliament, the Palace lies on the north b ...

was established as the seat of the English Parliament. In 1548, the House of Commons was granted a regular meeting place by the Crown, St Stephen's Chapel. This had been a royal chapel. It was made into a debating chamber after Henry VIII

Henry VIII (28 June 149128 January 1547) was King of England from 22 April 1509 until his death in 1547. Henry is best known for his six marriages, and for his efforts to have his first marriage (to Catherine of Aragon) annulled. His disa ...

became the last monarch to use the Palace of Westminster as a place of residence and after the suppression of the college there.

This room was the home of the House of Commons until it was destroyed by fire in 1834, although the interior was altered several times up until then. The structure of this room was pivotal in the development of the Parliament of England. While most modern legislatures sit in a circular chamber, the benches of the British Houses of Parliament are laid out in the form of choir stalls in a chapel, simply because this is the part of the original room that the members of the House of Commons used when they were granted use of St Stephen's Chapel.

This structure took on a new significance with the emergence of political parties in the late 17th and early 18th centuries, as the tradition began whereby the members of the governing party would sit on the benches to the right of the Speaker and the opposition members on the benches to the left. It is said that the Speaker's chair was placed in front of the chapel's altar. As Members came and went they observed the custom of bowing to the altar and continued to do so, even when it had been taken away, thus then bowing to the Chair, as is still the custom today.

The numbers of the Lords Spiritual

The Lords Spiritual are the bishops of the Church of England who serve in the House of Lords of the United Kingdom. 26 out of the 42 diocesan bishops and archbishops of the Church of England serve as Lords Spiritual (not counting retired archbi ...

diminished under Henry VIII, who commanded the Dissolution of the Monasteries, thereby depriving the abbots and priors of their seats in the Upper House. For the first time, the Lords Temporal

The Lords Temporal are secular members of the House of Lords, the upper house of the British Parliament. These can be either life peers or hereditary peers, although the hereditary right to sit in the House of Lords was abolished for all but ...

were more numerous than the Lords Spiritual. Currently, the Lords Spiritual consist of the Archbishops of Canterbury and York, the Bishops of London, Durham and Winchester, and twenty-one other English diocesan bishops in seniority of appointment to a diocese.

The Laws in Wales Acts

The Laws in Wales Acts 1535 and 1542 ( cy, Y Deddfau Cyfreithiau yng Nghymru 1535 a 1542) were Acts of the Parliament of England, and were the parliamentary measures by which Wales was annexed to the Kingdom of England. Moreover, the legal ...

of 1535–42 annexed Wales

Wales ( cy, Cymru ) is a country that is part of the United Kingdom. It is bordered by England to the east, the Irish Sea to the north and west, the Celtic Sea to the south west and the Bristol Channel to the south. It had a population in ...

as part of England and this brought Welsh representatives into the Parliament of England, first elected in 1542.

Rebellion and revolution

Parliament had not always submitted to the wishes of the Tudor monarchs. But parliamentary criticism of the monarchy reached new levels in the 17th century. When the last Tudor monarch, Elizabeth I, died in 1603, King James VI of Scotland came to power as King James I, founding the Stuart monarchy.

In 1628, alarmed by the arbitrary exercise of royal power, the House of Commons submitted to

Parliament had not always submitted to the wishes of the Tudor monarchs. But parliamentary criticism of the monarchy reached new levels in the 17th century. When the last Tudor monarch, Elizabeth I, died in 1603, King James VI of Scotland came to power as King James I, founding the Stuart monarchy.

In 1628, alarmed by the arbitrary exercise of royal power, the House of Commons submitted to Charles I Charles I may refer to:

Kings and emperors

* Charlemagne (742–814), numbered Charles I in the lists of Holy Roman Emperors and French kings

* Charles I of Anjou (1226–1285), also king of Albania, Jerusalem, Naples and Sicily

* Charles I of ...

the Petition of Right, demanding the restoration of their liberties. Though he accepted the petition, Charles later dissolved parliament and ruled without them for eleven years. It was only after the financial disaster of the Scottish Bishops' Wars

The 1639 and 1640 Bishops' Wars () were the first of the conflicts known collectively as the 1639 to 1653 Wars of the Three Kingdoms, which took place in Scotland, England and Ireland. Others include the Irish Confederate Wars, the First ...

(1639–1640) that he was forced to recall Parliament so that they could authorise new taxes. This resulted in the calling of the assemblies known historically as the Short Parliament

The Short Parliament was a Parliament of England that was summoned by King Charles I of England on the 20th of February 1640 and sat from 13th of April to the 5th of May 1640. It was so called because of its short life of only three weeks.

Af ...

of 1640 and the Long Parliament

The Long Parliament was an English Parliament which lasted from 1640 until 1660. It followed the fiasco of the Short Parliament, which had convened for only three weeks during the spring of 1640 after an 11-year parliamentary absence. In Septe ...

, which sat with several breaks and in various forms between 1640 and 1660.

The Long Parliament was characterised by the growing number of critics of the king who sat in it. The most prominent of these critics in the House of Commons was John Pym. Tensions between the king and his parliament reached a boiling point in January 1642 when Charles entered the House of Commons and tried, unsuccessfully, to arrest Pym and four other members for their alleged treason. The Five Members

The Five Members were Members of Parliament whom King Charles I attempted to arrest on 4 January 1642. King Charles I entered the English House of Commons, accompanied by armed soldiers, during a sitting of the Long Parliament, although the ...

had been tipped off about this, and by the time Charles came into the chamber with a group of soldiers they had disappeared. Charles was further humiliated when he asked the Speaker, William Lenthall

William Lenthall (1591–1662) was an English politician of the Civil War period. He served as Speaker of the House of Commons for a period of almost twenty years, both before and after the execution of King Charles I.

He is best remembered f ...

, to give their whereabouts, which Lenthall famously refused to do.

From then on relations between the king and his parliament deteriorated further. When trouble started to brew in Ireland, both Charles and his parliament raised armies to quell the uprisings by native Catholics there. It was not long before it was clear that these forces would end up fighting each other, leading to the English Civil War

The English Civil War (1642–1651) was a series of civil wars and political machinations between Parliamentarians (" Roundheads") and Royalists led by Charles I (" Cavaliers"), mainly over the manner of England's governance and issues of r ...

which began with the Battle of Edgehill

The Battle of Edgehill (or Edge Hill) was a pitched battle of the First English Civil War. It was fought near Edge Hill and Kineton in southern Warwickshire on Sunday, 23 October 1642.

All attempts at constitutional compromise between ...

in October 1642: those supporting the cause of parliament were called Parliamentarians (or Roundheads), and those in support of the Crown were called Royalists (or Cavalier

The term Cavalier () was first used by Roundheads as a term of abuse for the wealthier royalist supporters of King Charles I and his son Charles II of England during the English Civil War, the Interregnum, and the Restoration (1642 – ). ...

s).

Battles between Crown and Parliament continued throughout the 17th and 18th centuries, but parliament was no longer subservient to the English monarchy. This change was symbolised in the execution of Charles I Charles I may refer to:

Kings and emperors

* Charlemagne (742–814), numbered Charles I in the lists of Holy Roman Emperors and French kings

* Charles I of Anjou (1226–1285), also king of Albania, Jerusalem, Naples and Sicily

* Charles I of ...

in January 1649.

In Pride's Purge

Pride's Purge is the name commonly given to an event that took place on 6 December 1648, when soldiers prevented members of Parliament considered hostile to the New Model Army from entering the House of Commons of England.

Despite defeat in the ...

of December 1648, the New Model Army

The New Model Army was a standing army formed in 1645 by the Parliamentarians during the First English Civil War, then disbanded after the Stuart Restoration in 1660. It differed from other armies employed in the 1639 to 1653 Wars of the Th ...

(which by then had emerged as the leading force in the parliamentary alliance) purged Parliament of members that did not support them. The remaining "Rump Parliament

The Rump Parliament was the English Parliament after Colonel Thomas Pride commanded soldiers to purge the Long Parliament, on 6 December 1648, of those members hostile to the Grandees' intention to try King Charles I for high treason.

"R ...

", as it was later referred to by critics, enacted legislation to put the king on trial for treason. This trial, the outcome of which was a foregone conclusion, led to the execution of the king and the start of an 11-year republic.

The House of Lords was abolished and the purged House of Commons governed England until April 1653, when army chief Oliver Cromwell

Oliver Cromwell (25 April 15993 September 1658) was an English politician and military officer who is widely regarded as one of the most important statesmen in English history. He came to prominence during the 1639 to 1651 Wars of the Three ...

dissolved it after disagreements over religious policy and how to carry out elections to parliament. Cromwell later convened a parliament of religious radicals in 1653, commonly known as Barebone's Parliament, followed by the unicameral First Protectorate Parliament that sat from September 1654 to January 1655 and the Second Protectorate Parliament that sat in two sessions between 1656 and 1658, the first session was unicameral and the second session was bicameral.

Although it is easy to dismiss the English Republic of 1649–60 as nothing more than a Cromwellian military dictatorship, the events that took place in this decade were hugely important in determining the future of parliament. First, it was during the sitting of the first Rump Parliament that members of the House of Commons became known as "MPs" (Members of Parliament). Second, Cromwell gave a huge degree of freedom to his parliaments, although royalists were barred from sitting in all but a handful of cases.

Cromwell's vision of parliament appears to have been largely based on the example of the Elizabethan parliaments. However, he underestimated the extent to which Elizabeth I and her ministers had directly and indirectly influenced the decision-making process of her parliaments. He was thus always surprised when they became troublesome. He ended up dissolving each parliament that he convened. Yet it is worth noting that the structure of the second session of the Second Protectorate Parliament of 1658 was almost identical to the parliamentary structure consolidated in the Glorious Revolution

The Glorious Revolution; gd, Rèabhlaid Ghlòrmhor; cy, Chwyldro Gogoneddus , also known as the ''Glorieuze Overtocht'' or ''Glorious Crossing'' in the Netherlands, is the sequence of events leading to the deposition of King James II and ...

Settlement of 1689.

In 1653 Cromwell had been made head of state with the title Lord Protector of the Realm. The Second Protectorate Parliament offered him the crown. Cromwell rejected this offer, but the governmental structure embodied in the final version of the Humble Petition and Advice

The Humble Petition and Advice was the second and last codified constitution of England after the Instrument of Government.

On 23 February 1657, during a sitting of the Second Protectorate Parliament, Sir Christopher Packe, a Member of Parliam ...

was a basis for all future parliaments. It proposed an elected House of Commons as the Lower Chamber, a House of Lords containing peers of the realm as the Upper Chamber. A constitutional monarchy, subservient to parliament and the laws of the nation, would act as the executive arm of the state at the top of the tree, assisted in carrying out their duties by a Privy Council. Oliver Cromwell had thus inadvertently presided over the creation of a basis for the future parliamentary government of England. In 1657 he had the Parliament of Scotland

The Parliament of Scotland ( sco, Pairlament o Scotland; gd, Pàrlamaid na h-Alba) was the legislature of the Kingdom of Scotland from the 13th century until 1707. The parliament evolved during the early 13th century from the king's council o ...

(temporarily) unified with the English Parliament.

In terms of the evolution of parliament as an institution, by far the most important development during the republic was the sitting of the Rump Parliament between 1649 and 1653. This proved that parliament could survive without a monarchy and a House of Lords if it wanted to. Future English monarchs would never forget this. Charles I was the last English monarch ever to enter the House of Commons.

Even to this day, a Member of the Parliament of the United Kingdom is sent to Buckingham Palace

Buckingham Palace () is a London royal residence and the administrative headquarters of the monarch of the United Kingdom. Located in the City of Westminster, the palace is often at the centre of state occasions and royal hospitality. It ...

as a ceremonial hostage during the State Opening of Parliament

The State Opening of Parliament is a ceremonial event which formally marks the beginning of a session of the Parliament of the United Kingdom. It includes a speech from the throne known as the King's (or Queen's) Speech. The event takes plac ...

, in order to ensure the safe return of the sovereign from a potentially hostile parliament. During the ceremony the monarch sits on the throne in the House of Lords and signals for the Lord Great Chamberlain

The Lord Great Chamberlain of England is the sixth of the Great Officers of State, ranking beneath the Lord Keeper of the Privy Seal and above the Lord High Constable. The Lord Great Chamberlain has charge over the Palace of Westminster (tho ...

to summon the House of Commons to the Lords Chamber. The Lord Great Chamberlain then raises his wand of office to signal to the Gentleman Usher of the Black Rod

Black Rod (officially known as the Lady Usher of the Black Rod or, if male, the Gentleman Usher of the Black Rod) is an official in the parliaments of several Commonwealth countries. The position originates in the House of Lords of the Parliam ...

, who has been waiting in the central lobby. Black Rod turns and, escorted by the doorkeeper of the House of Lords and an inspector of police, approaches the doors to the chamber of the Commons. The doors are slammed in his face—symbolising the right of the Commons to debate without the presence of the monarch's representative. He then strikes three times with his staff (the Black Rod), and he is admitted.

Parliament from the Restoration to the Act of Settlement

The revolutionary events that occurred between 1620 and 1689 all took place in the name of parliament. The new status of parliament as the central governmental organ of the English state was consolidated during the events surrounding the Restoration of the monarchy in 1660. After the death of Oliver Cromwell in September 1658, his sonRichard Cromwell

Richard Cromwell (4 October 162612 July 1712) was an English statesman who was the second and last Lord Protector of the Commonwealth of England, Scotland and Ireland and son of the first Lord Protector, Oliver Cromwell.

On his father's deat ...

succeeded him as Lord Protector, summoning the Third Protectorate Parliament

The Third Protectorate Parliament sat for one session, from 27 January 1659 until 22 April 1659, with Chaloner Chute and Thomas Bampfylde as the Speakers of the House of Commons. It was a bicameral Parliament, with an Upper House having a pow ...

in the process. When this parliament was dissolved under pressure from the army in April 1659, the Rump Parliament was recalled at the insistence of the surviving army grandees. This in turn was dissolved in a coup led by army general John Lambert John Lambert may refer to:

* John Lambert (martyr) (died 1538), English Protestant martyred during the reign of Henry VIII

*John Lambert (general) (1619–1684), Parliamentary general in the English Civil War

* John Lambert of Creg Clare (''fl.'' c ...

, leading to the formation of the Committee of Safety, dominated by Lambert and his supporters.

When the breakaway forces of George Monck invaded England from Scotland, where they had been stationed without Lambert's supporters putting up a fight, Monck temporarily recalled the Rump Parliament and reversed Pride's Purge

Pride's Purge is the name commonly given to an event that took place on 6 December 1648, when soldiers prevented members of Parliament considered hostile to the New Model Army from entering the House of Commons of England.

Despite defeat in the ...

by recalling the entirety of the Long Parliament. They then voted to dissolve themselves and call new elections, which were arguably the most democratic for 20 years although the franchise was still very small. This led to the calling of the Convention Parliament which was dominated by royalists. This parliament voted to reinstate the monarchy and the House of Lords. Charles II returned to England as king in May 1660. The Anglo-Scottish parliamentary union that Cromwell had established was dissolved in 1661 when the Scottish Parliament resumed its separate meeting place in Edinburgh.

The Restoration began the tradition whereby all governments looked to parliament for legitimacy. In 1681 Charles II dissolved parliament and ruled without them for the last four years of his reign. This followed bitter disagreements between the king and parliament that had occurred between 1679 and 1681. Charles took a big gamble by doing this. He risked the possibility of a military showdown akin to that of 1642. However, he rightly predicted that the nation did not want another civil war. Parliament disbanded without a fight. Events that followed ensured that this would be nothing but a temporary blip.

Charles II died in 1685 and he was succeeded by his brother James II. During his lifetime Charles had always pledged loyalty to the Protestant Church of England, despite his private Catholic sympathies. James was openly Catholic. He attempted to lift restrictions on Catholics taking up public offices. This was bitterly opposed by Protestants in his kingdom. They invited William of Orange, a Protestant who had married Mary, daughter of James II and Anne Hyde

Anne Hyde (12 March 163731 March 1671) was Duchess of York and Albany as the first wife of James, Duke of York, who later became King James II and VII.

Anne was the daughter of a member of the English gentry – Edward Hyde (later created ...

to invade England and claim the throne.

William assembled an army estimated at 15,000 soldiers (11,000 foot and 4000 horse) and landed at Brixham

Brixham is a coastal town and civil parish, the smallest and southernmost of the three main population centres (the others being Paignton and Torquay) on the coast of Torbay in the county of Devon, in the south-west of England. Commercial fis ...

in southwest England in November, 1688. When many Protestant officers, including James's close adviser, John Churchill, 1st Duke of Marlborough, defected from the English army to William's invasion force, James fled the country. Parliament then offered the Crown to his Protestant daughter Mary, instead of his infant son (James Francis Edward Stuart

James Francis Edward Stuart (10 June 16881 January 1766), nicknamed the Old Pretender by Whigs, was the son of King James II and VII of England, Scotland and Ireland, and his second wife, Mary of Modena. He was Prince of Wales fro ...

), who was baptised Catholic. Mary refused the offer, and instead William and Mary ruled jointly, with both having the right to rule alone on the other's death.

As part of the compromise in allowing William to be King—called the Glorious Revolution

The Glorious Revolution; gd, Rèabhlaid Ghlòrmhor; cy, Chwyldro Gogoneddus , also known as the ''Glorieuze Overtocht'' or ''Glorious Crossing'' in the Netherlands, is the sequence of events leading to the deposition of King James II and ...

—Parliament was able to have the 1689 Bill of Rights enacted. Later the 1701 Act of Settlement was approved. These were statutes that lawfully upheld the prominence of parliament for the first time in English history. These events marked the beginning of the English constitutional monarchy

The monarchy of the United Kingdom, commonly referred to as the British monarchy, is the constitutional form of government by which a hereditary sovereign reigns as the head of state of the United Kingdom, the Crown Dependencies (the Bailiwi ...

and its role as one of the three elements of parliament.