Eleftherios Kyriakou Venizelos ( el, Ελευθέριος Κυριάκου Βενιζέλος, translit=Elefthérios Kyriákou Venizélos, ; – 18 March 1936) was a

Greek

Greek may refer to:

Greece

Anything of, from, or related to Greece, a country in Southern Europe:

*Greeks, an ethnic group.

*Greek language, a branch of the Indo-European language family.

**Proto-Greek language, the assumed last common ancestor ...

statesman and a prominent leader of the Greek national liberation movement. He is noted for his contribution to the expansion of

Greece

Greece,, or , romanized: ', officially the Hellenic Republic, is a country in Southeast Europe. It is situated on the southern tip of the Balkans, and is located at the crossroads of Europe, Asia, and Africa. Greece shares land borders ...

and promotion of

liberal-democratic policies.

[Kitromilides, 2006, p. 178]["Liberty Still Rules"](_blank)

''Time

Time is the continued sequence of existence and events that occurs in an apparently irreversible succession from the past, through the present, into the future. It is a component quantity of various measurements used to sequence events, ...

'', 18 February 1924. As leader of the

Liberal Party

The Liberal Party is any of many political parties around the world. The meaning of ''liberal'' varies around the world, ranging from liberal conservatism on the right to social liberalism on the left.

__TOC__ Active liberal parties

This is a li ...

, he held office as

prime minister of Greece for over 12 years, spanning eight terms between 1910 and 1933. Venizelos had such profound influence on the internal and external affairs of Greece that he is credited with being "The Maker of Modern Greece", and is still widely known as the "

Ethnarch

Ethnarch (pronounced , also ethnarches, el, ) is a term that refers generally to political leadership over a common ethnic group or homogeneous kingdom. The word is derived from the Greek words ('' ethnos'', "tribe/nation") and (''archon'', " ...

".

His first entry into the international scene was with his significant role in the autonomy of the

Cretan State

The Cretan State ( el, Κρητική Πολιτεία, Kritiki Politeia; ota, كريد دولتى, Girid Devleti) was established in 1898, following the intervention by the Great Powers (United Kingdom, France, Italy, Austria-Hungary, Germany ...

and later in

the union of

Crete

Crete ( el, Κρήτη, translit=, Modern: , Ancient: ) is the largest and most populous of the Greek islands, the 88th largest island in the world and the fifth largest island in the Mediterranean Sea, after Sicily, Sardinia, Cyprus, ...

with

Greece

Greece,, or , romanized: ', officially the Hellenic Republic, is a country in Southeast Europe. It is situated on the southern tip of the Balkans, and is located at the crossroads of Europe, Asia, and Africa. Greece shares land borders ...

. In 1909, he was invited to Athens to resolve the political deadlock and became the country's Prime Minister. Not only did he initiate constitutional and economic reforms that set the basis for the modernization of Greek society, but also reorganized both army and navy in preparation of future conflicts. Before the

Balkan Wars of 1912–1913, Venizelos' catalytic role helped gain Greece entrance to the

Balkan League

The League of the Balkans was a quadruple alliance formed by a series of bilateral treaties concluded in 1912 between the Eastern Orthodox kingdoms of Greece, Bulgaria, Serbia and Montenegro, and directed against the Ottoman Empire, which at the ...

, an alliance of the Balkan states against the

Ottoman Empire

The Ottoman Empire, * ; is an archaic version. The definite article forms and were synonymous * and el, Оθωμανική Αυτοκρατορία, Othōmanikē Avtokratoria, label=none * info page on book at Martin Luther University) ...

. Through his diplomatic acumen, Greece doubled its area and population with the liberation of

Macedonia,

Epirus

sq, Epiri rup, Epiru

, native_name_lang =

, settlement_type = Historical region

, image_map = Epirus antiquus tabula.jpg

, map_alt =

, map_caption = Map of ancient Epirus by Heinri ...

, and most of the

Aegean islands.

In

World War I

World War I (28 July 1914 11 November 1918), often abbreviated as WWI, was one of the deadliest global conflicts in history. Belligerents included much of Europe, the Russian Empire, the United States, and the Ottoman Empire, with fightin ...

(1914–1918), he brought Greece on the side of the

Allies, further expanding the Greek borders. However, his pro-Allied foreign policy brought him into direct conflict with

Constantine I of Greece, causing the

National Schism

The National Schism ( el, Εθνικός Διχασμός, Ethnikós Dichasmós), also sometimes called The Great Division, was a series of disagreements between King Constantine I and Prime Minister Eleftherios Venizelos regarding the foreig ...

. The Schism polarized the population between the

royalists

A royalist supports a particular monarch as head of state for a particular kingdom, or of a particular dynastic claim. In the abstract, this position is royalism. It is distinct from monarchism, which advocates a monarchical system of governm ...

and

Venizelists and the struggle for power between the two groups affected the political and social life of Greece for decades. Following the Allied victory, Venizelos secured new territorial gains, especially in

Anatolia

Anatolia, tr, Anadolu Yarımadası), and the Anatolian plateau, also known as Asia Minor, is a large peninsula in Western Asia and the westernmost protrusion of the Asian continent. It constitutes the major part of modern-day Turkey. The ...

, coming close to realizing the

Megali Idea

The Megali Idea ( el, Μεγάλη Ιδέα, Megáli Idéa, Great Idea) is a nationalist and irredentist concept that expresses the goal of reviving the Byzantine Empire, by establishing a Greek state, which would include the large Greek popu ...

. Despite his achievements, he was defeated in the

1920 General Election, which contributed to the eventual Greek defeat in the

Greco-Turkish War (1919–22) There have been several Greco-Turkish Wars:

* Greek War of Independence (1821–1830), against the Ottoman Empire

*Undeclared war in 1854 during the Crimean War, with Greek irregulars invading Ottoman Epirus (Epirus Revolt of 1854) and Thessaly

* Fi ...

. Venizelos, in self-imposed exile, represented Greece in the negotiations that led to the signing of the

Treaty of Lausanne and the agreement of a mutual

population exchange between Greece and Turkey

The 1923 population exchange between Greece and Turkey ( el, Ἡ Ἀνταλλαγή, I Antallagí, ota, مبادله, Mübâdele, tr, Mübadele) stemmed from the "Convention Concerning the Exchange of Greek and Turkish Populations" signed at ...

.

In his subsequent periods in office, Venizelos restored normal relations with Greece's neighbors and expanded his constitutional and economic reforms. In 1935, he resurfaced from retirement to support a

military coup

A military, also known collectively as armed forces, is a heavily armed, highly organized force primarily intended for warfare. It is typically authorized and maintained by a sovereign state, with its members identifiable by their distinct ...

. The coup's failure severely weakened the

Second Hellenic Republic

The Second Hellenic Republic is a modern historiographical term used to refer to the Greek state during a period of republican governance between 1924 and 1935. To its contemporaries it was known officially as the Hellenic Republic ( el, Ἑλ� ...

.

Origins and early years

Ancestry

A theory supported that in the 18th century, the ancestors of Venizelos, named Crevvatas, lived in

Mystras

Mystras or Mistras ( el, Μυστρᾶς/Μιστρᾶς), also known in the '' Chronicle of the Morea'' as Myzithras (Μυζηθρᾶς), is a fortified town and a former municipality in Laconia, Peloponnese, Greece. Situated on Mt. Taygetus, ne ...

, in southern

Peloponnese. During the

Ottoman raids in the peninsula in 1770, a member of the Crevvatas family (Venizelos Crevvatas), the youngest of several brothers, managed to escape to

Crete

Crete ( el, Κρήτη, translit=, Modern: , Ancient: ) is the largest and most populous of the Greek islands, the 88th largest island in the world and the fifth largest island in the Mediterranean Sea, after Sicily, Sardinia, Cyprus, ...

where he established himself. His sons discarded their patronymic and called themselves Venizelos. The family was of

Laconic

A laconic phrase or laconism is a concise or terse statement, especially a blunt and elliptical rejoinder. It is named after Laconia, the region of Greece including the city of Sparta, whose ancient inhabitants had a reputation for verbal auster ...

,

Maniot

The Maniots or Maniates ( el, Μανιάτες) are the inhabitants of Mani Peninsula, located in western Laconia and eastern Messenia, in the southern Peloponnese, Greece. They were also formerly known as Mainotes and the peninsula as ''Maina''. ...

, and

Cretan

Crete ( el, Κρήτη, translit=, Modern: , Ancient: ) is the largest and most populous of the Greek islands, the 88th largest island in the world and the fifth largest island in the Mediterranean Sea, after Sicily, Sardinia, Cyprus, an ...

origin.

[Chester, 1921, p. 4]

However, during the

National Schism

The National Schism ( el, Εθνικός Διχασμός, Ethnikós Dichasmós), also sometimes called The Great Division, was a series of disagreements between King Constantine I and Prime Minister Eleftherios Venizelos regarding the foreig ...

, politician Konstantinos Krevattas denied that his family had any relation to Venizelos. In a letter to a Cretan partner, Venizelos wrote that his father Kyriakos had taken part in the siege of Monemvasia in 1821 with his brother Hatzinikolos Venizelos and 3 more brothers. His grandfather probably was Hatzipetros Benizelos, a merchant from

Kythira

Kythira (, ; el, Κύθηρα, , also transliterated as Cythera, Kythera and Kithira) is an island in Greece lying opposite the south-eastern tip of the Peloponnese peninsula. It is traditionally listed as one of the seven main Ionian Islands ...

.

Family and education

Eleftherios was born in

Mournies

Mournies ( el, Μουρνιές) is a village in Crete, in the regional unit of Chania. Between 1997 and 2010, it was the seat of the former municipality of Eleftherios Venizelos. Mournies is famous for being the place of birth of the statesman Ele ...

, near

Chania

Chania ( el, Χανιά ; vec, La Canea), also spelled Hania, is a city in Greece and the capital of the Chania regional unit. It lies along the north west coast of the island Crete, about west of Rethymno and west of Heraklion.

The muni ...

(formerly known as Canea) in then-

Ottoman Crete

Crete ( el, Κρήτη, translit=, Modern: , Ancient: ) is the largest and most populous of the Greek islands, the 88th largest island in the world and the fifth largest island in the Mediterranean Sea, after Sicily, Sardinia, Cyprus, ...

to , a Cretan merchant and revolutionary, and

Styliani Ploumidaki.

When the

Cretan revolution of 1866 broke out, Venizelos' family fled to the island of

Syros

Syros ( el, Σύρος ), also known as Siros or Syra, is a Greek island in the Cyclades, in the Aegean Sea. It is south-east of Athens. The area of the island is and it has 21,507 inhabitants (2011 census).

The largest towns are Ermoupoli, An ...

, due to the participation of his father in the revolution.

They were not allowed to return to Crete, and stayed in Syros until 1872, when

Abdülaziz granted an amnesty.

He spent his final year of secondary education at a school in

Ermoupolis

Ermoupoli ( el, Ερμούπολη), also known by the formal older name Ermoupolis or Hermoupolis ( el, < "Town of "), is a to ...

in Syros from which he received his certificate in 1880. In 1881, he enrolled at the

University of Athens

The National and Kapodistrian University of Athens (NKUA; el, Εθνικό και Καποδιστριακό Πανεπιστήμιο Αθηνών, ''Ethnikó ke Kapodistriakó Panepistímio Athinón''), usually referred to simply as the Univers ...

Law School and got his degree in Law with excellent grades. He returned to Crete in 1886 and worked as a lawyer in Chania. Throughout his life he maintained a passion for reading and was constantly improving his skills in English, Italian, German, and French.

Entry into politics

The situation in Crete during Venizelos' early years was fluid. The

Ottoman Empire

The Ottoman Empire, * ; is an archaic version. The definite article forms and were synonymous * and el, Оθωμανική Αυτοκρατορία, Othōmanikē Avtokratoria, label=none * info page on book at Martin Luther University) ...

was undermining the reforms, which were made under international pressure, while the Cretans desired to see the Sultan,

Abdul Hamid II, abandon "the ungrateful infidels".

[Ion, 1910, p. 277] Under these unstable conditions Venizelos entered into politics in the elections of 2 April 1889 as a member of the island's liberal party.

As a deputy he was distinguished for his eloquence and his radical opinions.

Political career in Crete

Cretan uprising

Background

The numerous revolutions in Crete, during and after the

Greek War of Independence (1821, 1833, 1841, 1858, 1866, 1878, 1889, 1895, 1897) were the result of the Cretans' desire for ''

enosis'' — union with Greece. In the

Cretan revolution of 1866, the two sides, under the pressure of the

Great Powers, came to an agreement, which was finalized in the

Pact of Chalepa. Later the Pact was included in the provisions of the

Treaty of Berlin, which was supplementing previous concessions granted to the Cretans — e.g. the Organic Law Constitution (1868) designed by

William James Stillman

William James Stillman (June 1, 1828July 6, 1901) was an American journalist, diplomat, author, historian, and photographer. Educated as an artist, Stillman subsequently converted to the profession of journalism, working primarily as a war corre ...

. In summary the Pact was granting a large degree of self-government to Greeks in Crete as a means of limiting their desire to rise up against their

Ottoman overlords.

However the

Muslims of Crete, who identified with Ottoman Empire, were not satisfied with these reforms, as in their view the administration of the island was delivered to the hands of the Christian Greek population. In practice, the Ottoman Empire failed to enforce the provisions of the Pact, thus fueling the existing tensions between the two communities; instead, the Ottoman authorities attempted to maintain order by the dispatching of substantial military reinforcements during 1880–1896. Throughout that period, the ''Cretan Question'' was a major issue of friction in the relations of

independent Greece with the Ottoman Empire.

In January 1897 violence and disorder were escalating on the island, thus polarizing the population. Massacres against the Christian population took place in

Chania

Chania ( el, Χανιά ; vec, La Canea), also spelled Hania, is a city in Greece and the capital of the Chania regional unit. It lies along the north west coast of the island Crete, about west of Rethymno and west of Heraklion.

The muni ...

[Kitromilides, 2006, p. 58][Lowell Sun (newspaper), 6 February 1897, p. 1][Holland, 2006, p. 87] and

Rethimno.

The Greek government, pressured by public opinion, intransigent political elements, extreme nationalist groups such as

Ethniki Etaireia, and the reluctance of the Great Powers to intervene, decided to send warships and army personnel to defend the Cretan Greeks. The Great Powers had no option then but to proceed with the occupation of the island, but they were late. A Greek force of about 2,000 men had landed at

Kolymbari on 3 February 1897, and its commanding officer, Colonel

Timoleon Vassos

Timoleon Vassos or Vasos ( el, Τιμολέων Βάσσος or Βάσος; 1836–1929) was a Hellenic Army officer and general.

He was born in Athens in 1836, the younger son of the hero of the Greek Revolution Vasos Mavrovouniotis. He studied ...

declared that he was taking over the island "in the name of the

King of the Hellenes

The Kingdom of Greece was ruled by the House of Wittelsbach between 1832 and 1862 and by the House of Glücksburg from 1863 to 1924, temporarily abolished during the Second Hellenic Republic, and from 1935 to 1973, when it was once more abolish ...

" and that he was announcing the union of Crete with Greece. This led to an uprising that spread immediately throughout the island. The Great Powers decided to blockade Crete with their fleets and land their troops, thus stopping the Greek army from approaching Chania.

[Dunning, Jun. 1987, p. 367]

Events at Akrotiri

Venizelos, at that time, was in an electoral tour of the island. Once he "saw Canea in flames", he hurried to

Malaxa, near Chania, where a group of about 2,000 rebels had assembled, and established himself as their header. He proposed an attack, along with other rebels, on the Turkish forces at

Akrotiri in order to displace them from the plains (Malaxa is in a higher altitude). Venizelos' subsequent actions at Akrotiri form a central set-piece in his myth. People composed poems on Akrotiri and his role there; editorials and articles spoke about his bravery, his visions and his diplomatic genius as inevitable accompaniment of later greatness.

Venizelos spent the night in Akrotiri and a

Greek flag

The national flag of Greece, popularly referred to as the "blue and white one" ( el, Γαλανόλευκη, ) or the "sky blue and white" (, ), is officially recognised by Greece as one of its national symbols and has nine equal horizontal strip ...

was raised. The

Ottoman forces requested help from the foreign admirals and attacked the rebels, with the ships of the Great Powers bombarding the rebel positions at Akrotiri. A shell threw down the flag, which was raised up again immediately. The mythologizing became more pronounced when we come to his actions in that February, as the following quotes display:

In the same evening of the bombardment, Venizelos wrote a protest to the foreign admirals, which was signed by all the chieftains present at Akrotiri. He wrote that the rebels would keep their positions until everyone is killed from the shells of European warships, in order not to let the Turks remain in Crete. The letter was deliberately leaked to international newspapers, evoking emotional reactions in Greece and in Europe, where the idea of Christians, who wanted their freedom, being bombarded by Christian vessels, caused popular indignation. Throughout western Europe much popular sympathy for the cause of the Christians in Crete was manifested, and much popular applause was bestowed on the Greeks.

War in Thessaly

The Great Powers sent a verbal note on 2 March to the governments of Greece and the Ottoman Empire, presenting a possible solution to the "Cretan Question", under which Crete to become an autonomous state under the suzerainty of the Sultan.

The

Porte replied on 5 March, accepting the proposals in principle, but on 8 March the Greek government rejected the proposal as a non-satisfactory solution and instead insisted on the union of Crete with Greece as the only solution.

Venizelos, as a representative of the Cretan rebels, met the admirals of the

Great Powers on a Russian warship on 7 March 1897. Even though no progress was made at the meeting, he persuaded the admirals to send him on a tour of the island, under their protection, in order to explore the people's opinions on the question of autonomy versus union. At the time, the majority of the Cretan population initially supported the union, but the subsequent events in Thessaly turned the public opinion towards autonomy as an intermediate step.

In reaction to the rebellion of Crete and the assistance sent by Greece, the Ottomans had relocated a significant part of their army in the Balkans to the north of

Thessaly

Thessaly ( el, Θεσσαλία, translit=Thessalía, ; ancient Thessalian: , ) is a traditional geographic and modern administrative region of Greece, comprising most of the ancient region of the same name. Before the Greek Dark Ages, The ...

, close to the borders with Greece. Greece in reply reinforced its borders in Thessaly. However, irregular Greek forces, who were members of the ''

Ethniki Etairia'' (followers of the

Megali Idea

The Megali Idea ( el, Μεγάλη Ιδέα, Megáli Idéa, Great Idea) is a nationalist and irredentist concept that expresses the goal of reviving the Byzantine Empire, by establishing a Greek state, which would include the large Greek popu ...

) acted without orders and raided Turkish outposts, leading the Ottoman Empire to declare war on Greece on 17 April. The war was a disaster for Greece. The Turkish army was better prepared, in large part due to the recent reforms carried out by a German mission under

Baron von der Goltz, and the

Greek army

The Hellenic Army ( el, Ελληνικός Στρατός, Ellinikós Stratós, sometimes abbreviated as ΕΣ), formed in 1828, is the land force of Greece. The term ''Hellenic'' is the endogenous synonym for ''Greek''. The Hellenic Army is the ...

was in retreat within weeks. The Great Powers again intervened and an armistice was signed in May 1897.

[Dunning Dec. 1897, p. 744]

Conclusion

The defeat of Greece in the

Greco-Turkish war, costing small territorial losses at the border line in northern Thessaly and an indemnity of £4,000,000,

turned into a diplomatic victory. The

Great Powers (Britain,

France

France (), officially the French Republic ( ), is a country primarily located in Western Europe. It also comprises of overseas regions and territories in the Americas and the Atlantic, Pacific and Indian Oceans. Its metropolitan area ...

,

Russia

Russia (, , ), or the Russian Federation, is a transcontinental country spanning Eastern Europe and Northern Asia. It is the largest country in the world, with its internationally recognised territory covering , and encompassing one-eig ...

, and

Italy

Italy ( it, Italia ), officially the Italian Republic, ) or the Republic of Italy, is a country in Southern Europe. It is located in the middle of the Mediterranean Sea, and its territory largely coincides with the homonymous geographical ...

), following the massacre in

Heraklion

Heraklion or Iraklion ( ; el, Ηράκλειο, , ) is the largest city and the administrative capital of the island of Crete and capital of Heraklion regional unit. It is the fourth largest city in Greece with a population of 211,370 (Urban Ar ...

on 25 August,

[Kitromilides, 2006, p. 68] imposed a final solution on the "Cretan Question"; Crete was proclaimed an

autonomous

In developmental psychology and moral, political, and bioethical philosophy, autonomy, from , ''autonomos'', from αὐτο- ''auto-'' "self" and νόμος ''nomos'', "law", hence when combined understood to mean "one who gives oneself one's ow ...

state under Ottoman

suzerainty.

Venizelos played an important role towards this solution, not only as the leader of the Cretan rebels but also as a skilled diplomat with his frequent communication with the admirals of the Great Powers.

The four Great Powers assumed the administration of Crete; and

Prince George of Greece

Prince George of Greece and Denmark ( el, Γεώργιος; 24 June 1869 – 25 November 1957) was the second son and child of George I of Greece and Olga Konstantinovna of Russia, and is remembered chiefly for having once saved the life of h ...

, the second son of

King George I of Greece, became High Commissioner, with Venizelos serving as his minister of Justice from 1899 to 1901.

Autonomous Cretan State

Prince George of Greece

Prince George of Greece and Denmark ( el, Γεώργιος; 24 June 1869 – 25 November 1957) was the second son and child of George I of Greece and Olga Konstantinovna of Russia, and is remembered chiefly for having once saved the life of h ...

was appointed

High Commissioner of the Cretan State for a three-year term.

On 13 December 1898, he arrived at Chania, where he received an unprecedented reception. On 27 April 1899, the High Commissioner created an Executive Committee composed of the Cretan leaders. Venizelos became minister of Justice and with the rest of the Committee, they began to organize the State and create a "Cretan constitution". Venizelos insisted to not be made reference on religion, so all the residents of Crete to feel represented. For his stance was later accused as pro-Turk (pro-Muslim) by his political opponents on the island.

After Venizelos submitted the complete juridical legislation on 18 May 1900, disagreements between him and Prince George began to emerge. Prince George decided to travel to Europe and announced to the Cretan population that "When I am traveling in Europe I shall ask the Powers for annexation, and I hope to succeed on account of my family connections".

[Kerofilias, 1915, pp. 30–31] The statement reached the public without the knowledge or approval of the Committee. Venizelos said to the Prince that it would not be proper to give hope to the population for something that wasn't feasible at the given moment. As Venizelos had expected, during the Prince's journey, the Great Powers rejected his request.

The disagreements continued on other topics; the Prince wanted to build a palace, but Venizelos strongly opposed it as that would mean perpetuation of the current arrangement of Governorship; Cretans accepted it only as temporary, until a final solution was found.

Relations between the two men became increasingly soured, and Venizelos repeatedly submitted his resignation.

In a meeting of the Executive Committee, Venizelos expressed his opinion that the island was not in essence autonomous, since militarily forces of the Great Powers were still present, and that the Great Powers were governing through their representative, the Prince. Venizelos suggested that once the Prince's service expired, then the Great Powers should be invited to the Committee, which, according to article 39 of the constitution (which was suppressed in the conference of Rome) would elect a new sovereign, thereby removing the need for the presence of the Great Powers. Once the Great Powers' troops left the island along with their representatives, then the union with Greece would be easier to achieve. This proposal was exploited by Venizelos' opponents, who accused him that he wanted Crete as an autonomous hegemony. Venizelos replied to the accusations by submitting once again his resignation, with the reasoning that for him it would be impossible henceforth to collaborate with the Committee's members; he assured the Commissioner however that he did not intend to join the opposition.

On 6 March 1901, in a report, he exposed the reasons that compelled him to resign to the High Commissioner, which was however leaked to the press. On 20 March, Venizelos was dismissed, because "he, without any authorization, publicly supported opinions opposite of those of the Commissioner".

Henceforth, Venizelos assumed the leadership of the opposition to the Prince. For the next three years, he carried out a hard political conflict, until the administration was virtually paralyzed and tensions dominated the island. Inevitably, these events led in March 1905 to the

Theriso Revolution, whose leader he was.

Revolution of Theriso

On 10 March 1905, the rebels gathered in Theriso and declared "the political union of Crete with Greece as a single free constitutional state"; the resolution was given to the Great Powers, where it was argued that the illegitimate provisional arrangement was preventing the island's economic growth and that the only logical solution to the "Cretan Question" was the unification with Greece. The High Commissioner, with the approval of the Great Powers, replied to the rebels that military force would be used against them.

However, more deputies joined with Venizelos in Theriso. The Great Powers' consuls met with Venizelos in Mournies in an attempt to achieve an agreement, but without any results.

The revolutionary government asked that Crete be granted a regime similar to that of

Eastern Rumelia

Eastern Rumelia ( bg, Източна Румелия, Iztochna Rumeliya; ota, , Rumeli-i Şarkî; el, Ανατολική Ρωμυλία, Anatoliki Romylia) was an autonomous province (''oblast'' in Bulgarian, '' vilayet'' in Turkish) in the Ott ...

. On 18 July, the

Great Powers declared martial law, but that did not discourage the rebels. On 15 August, the regular assembly in Chania voted in favor of most of the reforms that Venizelos proposed. The Great Powers' consuls met Venizelos again and accepted the reforms he had proposed. This led to the end of the Theriso revolt and to the resignation of Prince George as the High Commissioner. The Great Powers assigned the authority for selecting the island's new High Commissioner to

King George I of Greece, thereby ''de facto'' nullifying the Ottoman suzerainty. An ex-Prime Minister of Greece,

Alexandros Zaimis

Alexandros Zaimis ( el, Αλέξανδρος Ζαΐμης; 9 November 1855 – 15 September 1936) was a Greek politician who served as Greece's Prime Minister, Minister of the Interior, Minister of Justice, and High Commissioner of Crete. He serv ...

, was chosen for the place of High Commissioner, and Greek officers and non-commissioned officers were allowed to undertake the organization of the

Cretan Gendarmerie

The Cretan Gendarmerie ( el, Κρητική Χωροφυλακή) was a gendarmerie force created under the Cretan State, after the island of Crete gained autonomy from Ottoman rule in the late 19th century. It later played a major role in the c ...

. As soon as the Gendarmerie was organized, the foreign troops began to withdraw from the island. This was also a personal victory for Venizelos, who as a result achieved fame not only in Greece but also in Europe.

Following the

Young Turk Revolution

The Young Turk Revolution (July 1908) was a constitutionalist revolution in the Ottoman Empire. The Committee of Union and Progress (CUP), an organization of the Young Turks movement, forced Sultan Abdul Hamid II to restore the Ottoman Consti ...

, which Venizelos welcomed, Bulgaria declared its independence from the Ottoman Empire on 5 October 1908, and one day later

Franz Joseph

Franz Joseph I or Francis Joseph I (german: Franz Joseph Karl, hu, Ferenc József Károly, 18 August 1830 – 21 November 1916) was Emperor of Austria, King of Hungary, and the other states of the Habsburg monarchy from 2 December 1848 until his ...

,

Emperor of Austria

The Emperor of Austria (german: Kaiser von Österreich) was the ruler of the Austrian Empire and later the Austro-Hungarian Empire. A hereditary imperial title and office proclaimed in 1804 by Holy Roman Emperor Francis II, a member of the Hou ...

announced the

annexation of Bosnia-Herzegovina. Encouraged by these events, on the same day, the Cretans in turn rose up. Thousands of citizens in Chania and the surrounding regions on that day formed a rally, in which Venizelos declared the union of Crete with Greece. Having communicated with the government of

Athens

Athens ( ; el, Αθήνα, Athína ; grc, Ἀθῆναι, Athênai (pl.) ) is both the capital and largest city of Greece. With a population close to four million, it is also the seventh largest city in the European Union. Athens dominates ...

, Zaimis left for Athens before the rally.

An assembly was convened and declared the independence of Crete. The civil servants were sworn in the name of

King George I of Greece, while a five-member Executive Committee was established, with the authority to control the island on behalf of the King and according to the laws of the Greek state. Chairman of the committee was

Antonios Michelidakis and Venizelos became Minister of Justice and Foreign Affairs. In April 1910 a new assembly was convened and Venizelos was elected chairman and then Prime Minister. All foreign troops departed from Crete and power was transferred entirely to Venizelos' government.

Political career in Greece

Goudi military revolution of 1909

In May 1909, a number of officers in the Greek army emulating the

Young Turk Committee of Union and Progress

The Committee of Union and Progress (CUP) ( ota, اتحاد و ترقى جمعيتی, translit=İttihad ve Terakki Cemiyeti, script=Arab), later the Union and Progress Party ( ota, اتحاد و ترقى فرقهسی, translit=İttihad ve Tera ...

, sought to reform their country's national government and reorganize the army, thus creating the

Military League

The Goudi coup ( el, κίνημα στο Γουδί) was a military coup d'état that took place in Greece on the night of , starting at the barracks in Goudi, a neighborhood on the eastern outskirts of Athens. The coup was a pivotal event in mod ...

. The League, in August 1909, camped in the Athenian suburb of

Goudi

Goudi (, since 2006; formerly Γουδί ) is a residential neighbourhood of Athens, Greece, on the eastern part of town and on the foothills of Mount Hymettus.

History

The name of the area derives from the 19th century Goudi (Γουδή) famil ...

with their supporters forcing the government of

Dimitrios Rallis

Dimitrios Rallis (Greek: Δημήτριος Ράλλης; 1844–1921) was a Greek politician.

He was born in Athens in 1844. He was descended from an old Greek political family. Before Greek independence, his grandfather, Alexander Rallis, ...

to resign and a new one was formed with

Kiriakoulis Mavromichalis. An inaugurating period of direct military pressure upon the Chamber followed, but initial public support to the League quickly evaporated when it became apparent that the officers did not know how to implement their demands.

The political dead-end remained until the League invited Venizelos from Crete to undertake the leadership.

Venizelos went to Athens and after consulting with the

Military League

The Goudi coup ( el, κίνημα στο Γουδί) was a military coup d'état that took place in Greece on the night of , starting at the barracks in Goudi, a neighborhood on the eastern outskirts of Athens. The coup was a pivotal event in mod ...

and with representatives of the political world, he proposed a new government and

Parliament's reformation. His proposals were considered by the King and the Greek politicians dangerous for the political establishment. However, King George I, fearing an escalation of the crisis, convened a council with political leaders, and recommended them to accept Venizelos' proposals. After many postponements the King agreed to assign

Stephanos Dragoumis

Stefanos Dragoumis ( el, Στέφανος Δραγούμης; 1842September 17, 1923) was a judge, writer and the Prime Minister of Greece from January to October 1910. He was the father of Ion Dragoumis.

Early years

Dragoumis was born in Athen ...

(Venizelos' indication) to form a new government that would lead the country to elections once the League was disbanded. In the elections of 8 August 1910, almost half the seats in the parliament were won by Independents, who were newcomers to the Greek political scene. Venizelos, despite doubts as to the validity of his Greek citizenship and without having campaigned in person, finished at the top at the electoral list in

Attica

Attica ( el, Αττική, Ancient Greek ''Attikḗ'' or , or ), or the Attic Peninsula, is a historical region that encompasses the city of Athens, the capital of Greece and its countryside. It is a peninsula projecting into the Aegean S ...

. He was immediately recognized as the leader of the independents and thus he founded the political party, ''

Komma Fileleftheron'' (Liberal Party). Soon after his election he decided to call for new elections in hope of winning an

absolute majority

A supermajority, supra-majority, qualified majority, or special majority is a requirement for a proposal to gain a specified level of support which is greater than the threshold of more than one-half used for a simple majority. Supermajority r ...

. The old parties boycotted the new election in protest

[Mazower, 1992, p. 886] and on 11 December 1910, Venizelos' party

won 307 seats out of 362, with most of the elected citizens being new in the political scene. Venizelos formed a government and started to reorganize the economic, political, and national affairs of the country.

Reforms in 1910–1914

Venizelos tried to advance his reform program in the realms of political and social ideologies, of education, and literature, by adopting practically viable compromises between often conflicting tendencies. In education, for example, the dynamic current in favor of the use of the popular spoken language,

dimotiki, provoked conservative reactions, which led to the constitutionally embedded decision (Article 107) in favor of a formal "purified" language,

katharevousa

Katharevousa ( el, Καθαρεύουσα, , literally "purifying anguage) is a conservative form of the Modern Greek language conceived in the late 18th century as both a literary language and a compromise between Ancient Greek and the contempor ...

, which looked back to classical precedents.

On 20 May 1911, a revision of the Constitution was completed, which focused on strengthening individual freedoms, introducing measures to facilitate the legislative work of the Parliament, establishing of obligatory

elementary education

Primary education or elementary education is typically the first stage of formal education, coming after preschool/kindergarten and before secondary school. Primary education takes place in ''primary schools'', ''elementary schools'', or fir ...

, the legal right for compulsory

expropriation

Nationalization (nationalisation in British English) is the process of transforming privately-owned assets into public assets by bringing them under the public ownership of a national government or state. Nationalization usually refers to pri ...

, ensuring permanent appointment for civil servants, the right to invite foreign personnel to undertake the reorganization of the administration and the armed forces, the re-establishment of the State Council and the simplification of the procedures for the reform of the Constitution. The aim of the reform program was to consolidate public security and rule of law as well as to develop and increase the wealth-producing potential of the country. In this context, the long planned "eighth" Ministry, the

Ministry of National Economy, assumed a leading role. This Ministry, from the time of its creation at the beginning of 1911, was headed by

Emmanuel Benakis, a wealthy Greek merchant from

Egypt

Egypt ( ar, مصر , ), officially the Arab Republic of Egypt, is a transcontinental country spanning the northeast corner of Africa and southwest corner of Asia via a land bridge formed by the Sinai Peninsula. It is bordered by the Medit ...

and friend of Venizelos.

Between 1911 and 1912 a number of laws aiming to initiate

labor legislation

Labour laws (also known as labor laws or employment laws) are those that mediate the relationship between workers, employing entities, trade unions, and the government. Collective labour law relates to the tripartite relationship between employee, ...

in Greece were promulgated. Specific measures were enacted that prohibited child labor and night-shift work for women, that regulated the hours of the working week and the Sunday holiday, and allowed for labor organizations. Venizelos also took measures for the improvement of management, justice and security and for the settlement of the landless peasants of Thessaly.

Balkan Wars

Background

At the time there were diplomatic contacts with the

Ottoman Empire

The Ottoman Empire, * ; is an archaic version. The definite article forms and were synonymous * and el, Оθωμανική Αυτοκρατορία, Othōmanikē Avtokratoria, label=none * info page on book at Martin Luther University) ...

to initiate reforms in Macedonia and in

Thrace

Thrace (; el, Θράκη, Thráki; bg, Тракия, Trakiya; tr, Trakya) or Thrake is a geographical and historical region in Southeast Europe, now split among Bulgaria, Greece, and Turkey, which is bounded by the Balkan Mountains to ...

, which at the time were under the control of the Ottoman Empire, for improving the living conditions of the Christian populations. Failure of such reforms would leave as a single option to remove Ottoman Empire from the

Balkans

The Balkans ( ), also known as the Balkan Peninsula, is a geographical area in southeastern Europe with various geographical and historical definitions. The region takes its name from the Balkan Mountains that stretch throughout the who ...

, an idea that most Balkan countries shared. This scenario appeared realistic to Venizelos, because Ottoman Empire was under a

constitutional transition and its administrative mechanism was disorganized and weakened. There was also no fleet capable of transporting forces from

Asia Minor

Anatolia, tr, Anadolu Yarımadası), and the Anatolian plateau, also known as Asia Minor, is a large peninsula in Western Asia and the westernmost protrusion of the Asian continent. It constitutes the major part of modern-day Turkey. The re ...

to Europe, while in contrast the Greek fleet was dominating the

Aegean Sea

The Aegean Sea ; tr, Ege Denizi (Greek: Αιγαίο Πέλαγος: "Egéo Pélagos", Turkish: "Ege Denizi" or "Adalar Denizi") is an elongated embayment of the Mediterranean Sea between Europe and Asia. It is located between the Balkans ...

. Venizelos did not want to initiate any immediate major movements in the Balkans, until the Greek army and navy were reorganized (an effort that had begun from the last government of

Georgios Theotokis

Georgios Theotokis ( el, Γεώργιος Θεοτόκης, 1844 in Corfu – 12 January 1916 in Athens) was a Greek politician and Prime Minister of Greece, serving the post four times. He represented the Modernist Party or ''Neoteristikon Ko ...

) and the Greek economy was revitalized. In light of this, Venizelos proposed to Ottoman Empire to recognize the Cretans the right to send deputies to the Greek Parliament, as a solution for closing the ''Cretan Question''. However, the

Young Turks (feeling confident after the

Greco-Turkish war in 1897) threatened that they would make a military walk to Athens, if the Greeks insisted on such claims.

Balkan League

Venizelos, seeing no improvements after his approach with the Turks on the ''

Cretan Question'' and at the same time not wanting to see Greece remain inactive as in the

Russo-Turkish War in 1877 (where Greece's neutrality left the country out of the peace talks), he decided that the only way to settle the disputes with Ottoman Empire, was to join the other Balkan countries,

Serbia

Serbia (, ; Serbian: , , ), officially the Republic of Serbia (Serbian: , , ), is a landlocked country in Southeastern and Central Europe, situated at the crossroads of the Pannonian Basin and the Balkans. It shares land borders with Hungar ...

,

Bulgaria

Bulgaria (; bg, България, Bǎlgariya), officially the Republic of Bulgaria,, ) is a country in Southeast Europe. It is situated on the eastern flank of the Balkans, and is bordered by Romania to the north, Serbia and North Macedo ...

and

Montenegro

)

, image_map = Europe-Montenegro.svg

, map_caption =

, image_map2 =

, capital = Podgorica

, coordinates =

, largest_city = capital

, official_languages = M ...

, in an alliance known as the

Balkan League

The League of the Balkans was a quadruple alliance formed by a series of bilateral treaties concluded in 1912 between the Eastern Orthodox kingdoms of Greece, Bulgaria, Serbia and Montenegro, and directed against the Ottoman Empire, which at the ...

.

Crown Prince Constantine was sent to represent Greece to a royal feast in

Sofia

Sofia ( ; bg, София, Sofiya, ) is the capital and largest city of Bulgaria. It is situated in the Sofia Valley at the foot of the Vitosha mountain in the western parts of the country. The city is built west of the Iskar river, and h ...

, and in 1911 Bulgarian students were invited to Athens. These events had a positive impact and on 30 May 1912 Greece and the

Kingdom of Bulgaria

The Tsardom of Bulgaria ( bg, Царство България, translit=Tsarstvo Balgariya), also referred to as the Third Bulgarian Tsardom ( bg, Трето Българско Царство, translit=Treto Balgarsko Tsarstvo, links=no), someti ...

signed a treaty that ensured mutual support in case of a Turkish attack on either country. Negotiations with Serbia, which Venizelos had initiated to achieve a similar agreement, were concluded in early 1913,

[Kitromilides, 2006, p. 145] before that there were only oral agreements.

Montenegro opened hostilities by declaring war on the Ottoman Empire on 8 October 1912. On 17 October 1912, Greece along with her Balkan allies declared war on the Ottoman Empire, thus joining the

First Balkan War

The First Balkan War ( sr, Први балкански рат, ''Prvi balkanski rat''; bg, Балканска война; el, Αʹ Βαλκανικός πόλεμος; tr, Birinci Balkan Savaşı) lasted from October 1912 to May 1913 and invo ...

.

On 1 October, in a regular session of the Parliament Venizelos announced the declaration of war to the Ottomans and accepting the Cretan deputies, thus closing the ''Cretan Question'', with the declaration of the union of Crete with Greece. The Greek population received these developments very enthusiastically.

First Balkan War – The first conflict with Prince Constantine

The outbreak of the First Balkan war caused Venizelos a great deal of trouble in his relations with Crown Prince Constantine. Part of the problems can be attributed to the complexity of the official relations between the two men. Although Constantine was a Prince and the future King, he also held the title of army commander, thus remaining under the direct order of the Ministry of Military Affairs, and subsequently under Venizelos. But his father, King George, in accordance to the constitutional conditions of the time had been the undisputed leader of the country. Thus in practical terms Venizelos' authority over his commander of the army was diminished due to the obvious relation between the Crown Prince and the King.

In these conditions the army started a victorious march to Macedonia under the command of Constantine. Soon the first disagreement between Venizelos and Constantine emerged, and it concerned the aims of the army's operations. The Crown Prince insisted on the clear military aims of the war: to defeat the opposed Ottoman army as a necessary condition for any occupation, wherever the opponent army was or was going; and the main part of the Ottoman army soon started retreating to the north towards

Monastir. Venizelos was more realistic and insisted on the political aims of the war: to liberate as many geographical areas and cities as fast as possible, particularly Macedonia and Thessaloniki; thus heading east. The debate became evident after the victory of the Greek army at

Sarantaporo, when the future direction of the armys' march was to be decided. Venizelos intervened and insisted that

Thessaloniki

Thessaloniki (; el, Θεσσαλονίκη, , also known as Thessalonica (), Saloniki, or Salonica (), is the second-largest city in Greece, with over one million inhabitants in its metropolitan area, and the capital of the geographic region of ...

, as a major city and

strategic port in the surrounding area, should be taken at all costs and thus a turn to the east was necessary. In accordance to his views, Venizelos sent the following telegraph to the General Staff:

and tried to keep frequent communication with the key figure, the King, in order to prevent the Crown Prince from marching north.

Subsequently, although the Greek army won the

Battle of Giannitsa

The Battle of Yenidje, also transliterated as Yenice ( el, Μάχη των Γιαννιτσών, Battle of Giannitsa), was a major battle between Greek forces under Crown Prince Constantine and Ottoman forces under General Hasan Tahsin Pasha ...

situated 40 km west of Salonika, Constantine's hesitation in capturing the city after a week had passed, led into an open confrontation with Venizelos. Venizelos, having accurate information from the Greek embassy in Sofia about the movement of the Bulgarian army towards the city, sent a telegram to Constantine in a strict tone, holding him responsible for the possible loss of Thessaloniki. The tone in Venizelos' telegram and that in the answer from Constantine that followed to announce the final agreement with the Turks, is widely considered as the start of the conflict between the two men that would lead Greece into the National Schism during World War I. Finally on 26 October 1912, the Greek army entered Thessaloniki, shortly ahead of the

Bulgarians

Bulgarians ( bg, българи, Bǎlgari, ) are a nation and South Slavic ethnic group native to Bulgaria and the rest of Southeast Europe.

Etymology

Bulgarians derive their ethnonym from the Bulgars. Their name is not completely unders ...

. But soon a new reason of friction emerged due to Venizelos' concern about Constantine's acceptance of the Bulgarian request to enter the city. A small Bulgarian unit, which soon became a full division moved into the city and immediately started an attempt to establish a condominium in spite of initial assurances to the contrary, showing no intentions to leave. After Venizelos' protest Constantine asked him to take the responsibility (as a prime minister) by ordering him to force them out, but that was hardly an option since that would certainly lead to confrontation with the Bulgarians. To Venizelos' view, since Constantine allowed the Bulgarians to enter the city, he now passed the responsibility of a possible conflict with them to him, in an attempt to deny his initial fault. To Constantine, it was an attempt by Venizelos to get involved in clearly military issues. Most historians agree that Constantine failed to see the political dimensions of his decisions. As a consequence both incidents increased mutual misunderstanding, shortly before Constantine's accession to the throne.

Once the campaign in Macedonia was completed, a large part of the Greek army under the Crown Prince was redeployed to

Epirus

sq, Epiri rup, Epiru

, native_name_lang =

, settlement_type = Historical region

, image_map = Epirus antiquus tabula.jpg

, map_alt =

, map_caption = Map of ancient Epirus by Heinri ...

, and in the

Battle of Bizani the Ottoman positions were overcome and

Ioannina taken on 22 February 1913. Meanwhile, the Greek navy rapidly occupied the Aegean islands still under Ottoman rule. After two victories, the Greek fleet established naval supremacy over the

Aegean preventing the Turks from bringing reinforcements to the Balkans.

On 20 November, Serbia, Montenegro and Bulgaria signed a truce treaty with Turkey. It followed a conference in London, in which Greece took part, although the Greek army still continued its operations in the Epirus front. The conference led to the

Treaty of London between the Balkan countries and Turkey. These two conferences gave the first indications of Venizelos' diplomatic efficiency and realism. During the negotiations and facing the dangers of Bulgarian maximalism, Venizelos succeeded in establishing close relations with the Serbs. A Serbian-Greek military protocol was signed on 1 June 1913 ensuring mutual protection in case of a Bulgarian attack.

Second Balkan War

Despite all this, the Bulgarians still wanted to become a hegemonic power in the Balkans and made excessive claims to this end, while Serbia asked for more territory than what was initially agreed with the Bulgarians. Serbia was asking for a revision of the original treaty, since it had already lost north Albania due to the Great Powers' decision to establish the state of Albania, in an area that had been recognized as a Serbian territory of expansion under the prewar Serbo-Bulgarian treaty. Bulgarians also laid claims on Thessaloniki and most of Macedonia. In the conference of London, Venizelos rebuffed these claims, citing the fact that it had been occupied by the Greek army, and that Bulgaria had denied any definite settlement of territorial claims during the pre-war discussions, as it had done with Serbia.

The rupture between the allies, due to the Bulgarian claims, was inevitable, and Bulgaria found herself standing against Greece and Serbia. On 19 May 1913,

a pact of alliance was signed in Thessaloniki between Greece and Serbia. On 19 June, the Second Balkan War began with a surprise Bulgarian assault against Serbian and Greek positions. Constantine, now King after

his father's assassination in March, neutralized the Bulgarian forces in Thessaloniki and pushed the Bulgarian army further back with a series of hard-fought victories. Bulgaria was overwhelmed by the Greek and Serbian armies, while in the north

Romania

Romania ( ; ro, România ) is a country located at the crossroads of Central, Eastern, and Southeastern Europe. It borders Bulgaria to the south, Ukraine to the north, Hungary to the west, Serbia to the southwest, Moldova to the east, and ...

interfered against Bulgaria and the

Romanian army

The Romanian Land Forces ( ro, Forțele Terestre Române) is the army of Romania, and the main component of the Romanian Armed Forces. In recent years, full professionalisation and a major equipment overhaul have transformed the nature of the Lan ...

was marching towards Sofia; Ottomans also took advantage of the situation and retook most of the territory taken by Bulgaria. The Bulgarians asked for truce. Venizelos went to

Hadji-Beylik, where the Greek headquarters were, to confer with Constantine on the Greek territorial claims in the peace conference. Then he went to

Bucharest

Bucharest ( , ; ro, București ) is the capital and largest city of Romania, as well as its cultural, industrial, and financial centre. It is located in the southeast of the country, on the banks of the Dâmbovița River, less than north of ...

, where a peace conference was assembled. On 28 June 1913 a

peace treaty

A peace treaty is an agreement between two or more hostile parties, usually countries or governments, which formally ends a state of war between the parties. It is different from an armistice

An armistice is a formal agreement of warring ...

was signed with Greece, Montenegro, Serbia and Romania on one side and Bulgaria on the other. Thus, after two successful wars, Greece had doubled its territory by gaining most of

Macedonia,

Epirus

sq, Epiri rup, Epiru

, native_name_lang =

, settlement_type = Historical region

, image_map = Epirus antiquus tabula.jpg

, map_alt =

, map_caption = Map of ancient Epirus by Heinri ...

, Crete and the rest of the

Aegean Islands, although the status of the latter remained as yet undetermined and a cause of tension with the Ottomans.

World War I and Greece

Dispute over Greece's role in World War I

With the outbreak of World War I and the Austro-Hungarian invasion in Serbia, a major issue started regarding the participation or not of Greece and Bulgaria in the war. Greece had an active treaty with Serbia which was the treaty activated in the 1913 Bulgarian attack that caused the Second Balkan War. That treaty was envisaged in a purely Balkan context, and was thus invalid against

Austria-Hungary

Austria-Hungary, often referred to as the Austro-Hungarian Empire,, the Dual Monarchy, or Austria, was a constitutional monarchy and great power in Central Europe between 1867 and 1918. It was formed with the Austro-Hungarian Compromise of ...

, as was supported by Constantine and his advisors.

The situation changed when the Allies, in an attempt to help Serbia, offered Bulgaria the

Monastir–

Ochrid area of Serbia and the Greek Eastern Macedonia (the

Kavala

Kavala ( el, Καβάλα, ''Kavála'' ) is a city in northern Greece, the principal seaport of eastern Macedonia (Greece), Macedonia and the capital of Kavala (regional unit), Kavala regional unit.

It is situated on the Bay of Kavala, across ...

and

Drama

Drama is the specific mode of fiction represented in performance: a play, opera, mime, ballet, etc., performed in a theatre, or on radio or television.Elam (1980, 98). Considered as a genre of poetry in general, the dramatic mode has b ...

areas) if she joined the Entente. Venizelos, having received assurances over Asia Minor if the Greeks participated in the alliance, agreed to cede the area to Bulgaria.

But Constantine's anti-Bulgarism made such a transaction impossible. Constantine refused to go to war under such conditions and the men parted. As a consequence Bulgaria joined the

Central Powers

The Central Powers, also known as the Central Empires,german: Mittelmächte; hu, Központi hatalmak; tr, İttifak Devletleri / ; bg, Централни сили, translit=Tsentralni sili was one of the two main coalitions that fought in ...

and invaded Serbia, an event leading to Serbia's final collapse. Greece remained neutral. Venizelos supported an alliance with the

Entente, not only believing that Britain and France would win, but also that it was the only choice for Greece, because the combination of the strong Anglo-French naval control over the Mediterranean and the geographical distribution of the Greek population, could have ill effects in the case of a naval blockade, as he characteristically remarked:

On the other hand, Constantine favored the

Central Powers

The Central Powers, also known as the Central Empires,german: Mittelmächte; hu, Központi hatalmak; tr, İttifak Devletleri / ; bg, Централни сили, translit=Tsentralni sili was one of the two main coalitions that fought in ...

and wanted Greece to remain neutral.

He was influenced both by his belief in the military superiority of

Germany

Germany,, officially the Federal Republic of Germany, is a country in Central Europe. It is the second most populous country in Europe after Russia, and the most populous member state of the European Union. Germany is situated betwe ...

and also by his German wife,

Queen Sophia, and his pro-German court. He therefore strove to secure a neutrality, which would be favorable to Germany and

Austria

Austria, , bar, Östareich officially the Republic of Austria, is a country in the southern part of Central Europe, lying in the Eastern Alps. It is a federation of nine states, one of which is the capital, Vienna, the most populous ...

.

In 1915,

Winston Churchill

Sir Winston Leonard Spencer Churchill (30 November 187424 January 1965) was a British statesman, soldier, and writer who served as Prime Minister of the United Kingdom twice, from 1940 to 1945 during the Second World War, and again from ...

(then First Lord of the Admiralty) suggested to Greece to take action in

Dardanelles

The Dardanelles (; tr, Çanakkale Boğazı, lit=Strait of Çanakkale, el, Δαρδανέλλια, translit=Dardanéllia), also known as the Strait of Gallipoli from the Gallipoli peninsula or from Classical Antiquity as the Hellespont (; ...

on behalf of the allies.

[Firstworldwar.com](_blank)

''The Minor Powers During World War One – Greece'' Venizelos saw this as an opportunity to bring the country on the side of the Entente in the conflict. However the King and the

Hellenic Army General Staff

The Hellenic Army General Staff ( el, Γενικό Επιτελείο Στρατού, abbrev. ΓΕΣ) is the general staff of the Hellenic Army, the terrestrial component of the Greek Armed Forces. It was established in 1904. Since 1950, the HAGS ...

disagreed and Venizelos submitted his resignation on 21 February 1915.

Venizelos' party won the elections and formed a new government.

National Schism

Even though Venizelos promised to remain neutral, after the elections of 1915, he said that Bulgaria's attack on Serbia, with which Greece had a treaty of alliance, obliged him to abandon that policy. A small scale mobilisation of the Greek army took place.

The dispute between Venizelos and the King reached its height shortly after that and the King invoked a

Greek constitutional provision that gave the monarch the right to dismiss a government unilaterally. Meanwhile, using the excuse of saving Serbia, in October 1915, the Entente disembarked an army in Thessaloniki,

after invitation by Venizelos. This action of Prime Minister Venizelos enraged Constantine.

The dispute continued between the two men, and in December 1915, King Constantine forced Venizelos to resign for a second time and dissolved the Liberal-dominated parliament, calling for

new elections. Venizelos left Athens and moved back to Crete. Venizelos did not take part in the elections, as he considered the dissolution of Parliament unconstitutional.

On 26 May 1916 the

Fort Rupel (a significant military fort in Macedonia) was unconditionally surrendered by the royalist government to Germano-Bulgarian forces. This produced a deplorable impression. The Allies feared a possible secret alliance between the royalist government and Central Powers placing in grave danger of their armies in Macedonia. On the other hand, the surrender of Fort Rupel for Venizelos and his supporters meant the beginning of the destruction of Greek Macedonia. Despite German assurances that the integrity of the Kingdom of Greece would be respected they were unable to restrain the Bulgarian forces, which had started dislocating the Greek population, and by 4 September

Kavala

Kavala ( el, Καβάλα, ''Kavála'' ) is a city in northern Greece, the principal seaport of eastern Macedonia (Greece), Macedonia and the capital of Kavala (regional unit), Kavala regional unit.

It is situated on the Bay of Kavala, across ...

was occupied.

On 16 August 1916, during a rally in Athens, and with the support of the allied army that had landed in Thessaloniki under the command of General

Maurice Sarrail

Maurice Paul Emmanuel Sarrail (6 April 1856 – 23 March 1929) was a French general of the First World War. Sarrail's openly socialist political connections made him a rarity amongst the Catholics, conservatives and monarchists who dominated th ...

, Venizelos announced publicly his total disagreement with the Crown's policies. The effect of this was to further polarize the population between the

royalists

A royalist supports a particular monarch as head of state for a particular kingdom, or of a particular dynastic claim. In the abstract, this position is royalism. It is distinct from monarchism, which advocates a monarchical system of governm ...

(also known as ''anti-Venezelists''), who supported the crown, and

Venizelist

Venizelism ( el, Βενιζελισμός) was one of the major political movements in Greece from the 1900s until the mid-1970s.

Main ideas

Named after Eleftherios Venizelos, the key characteristics of Venizelism were:

*Greek irredentism: ...

s, who supported Venizelos. On 30 August 1916, Venizelist army officers organized a military coup in Thessaloniki, and proclaimed the "

Provisional Government of National Defence". Venizelos along with Admiral

Pavlos Kountouriotis

Pavlos Kountouriotis ( el, Παύλος Κουντουριώτης; 9 April 1855 – 22 August 1935) was a Greek rear admiral during the Balkan Wars, regent, and the first President of the Second Hellenic Republic. In total he served four times ...

and General

Panagiotis Danglis

Panagiotis Danglis ( el, Παναγιώτης Δαγκλής; – 9 March 1924) was a Greek Army general and politician. He is particularly notable for his invention of the Schneider-Danglis mountain gun, his service as chief of staff in the Bal ...

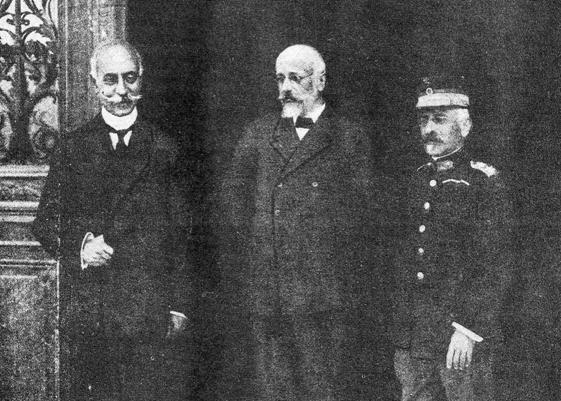

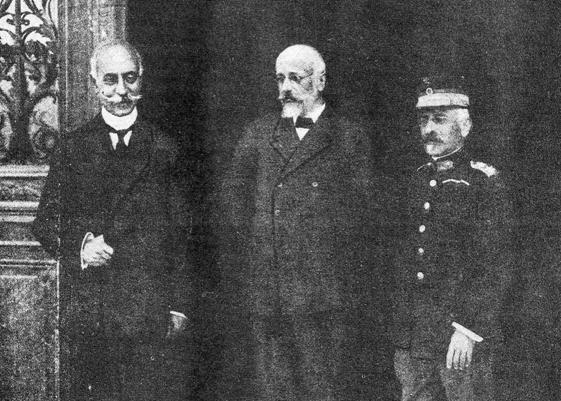

agreed to form a provisional government and on 9 October they moved to Thessaloniki and assumed command of the National Defence to oversee the Greek participation in the allied war effort. The triumvirate, as the three men became known, had formed this government in direct conflict with the Athens political establishment.

[Kitromilides, 2008, p. 124] There they founded a separate "provisional state" including Northern Greece, Crete and the Aegean Islands, with the support of the Entente. Primarily, these areas comprised the "New Lands" won during the Balkan Wars, in which Venizelos enjoyed a broad support, while "Old Greece" was mostly pro-royalist. However, Venizelos declared "we are not against the King, but against the Bulgarians". He didn't want to abolish the monarchy and continued his efforts to persuade the King to join the Allies, blaming his "bad advisors" for his stance.

The National Defence government started assembling an army for the Macedonian front and soon participated in operations against the

Central Powers

The Central Powers, also known as the Central Empires,german: Mittelmächte; hu, Központi hatalmak; tr, İttifak Devletleri / ; bg, Централни сили, translit=Tsentralni sili was one of the two main coalitions that fought in ...

forces.

"Noemvriana" – Greece enters World War I

In the following months after the creation of provisional government in Thessaloniki in late August, negotiations between the Allies and king intensified. The Allies wanted further demobilisation of the Greek army as a counterbalance of the unconditional surrender of Fort Rupel by the royalist government and military evacuation of Thessaly to insure the safety of their troops in Macedonia. On the other hand, the king wanted assurances that the Allies would not officially recognise Venizelos' provisional government or further support it, guarantees that Greece's integrity and neutrality would be respected, and a promise that any war material surrendered to the Allies would be returned after the war.

[Leon, 1974, p. 422]

The Franco-British use of Greece's territory in co-operation with the Venizelos government throughout 1916 was opposed in royalist circles and therefore increased Constantine's popularity, and caused much excitement and several anti-Allied demonstrations took place in Athens.

Moreover, a growing movement had been developed in the army among lower officers, led by military officers

Ioannis Metaxas

Ioannis Metaxas (; el, Ιωάννης Μεταξάς; 12th April 187129th January 1941) was a Greek military officer and politician who served as the Prime Minister of Greece from 1936 until his death in 1941. He governed constitutionally for t ...

and

Sofoklis Dousmanis

Sofoklis Dousmanis ( el, Σοφοκλής Δούσμανης, 25 December 1868 – 6 January 1952) was a Greek naval officer. Distinguished in the Balkan Wars, he became twice the chief of the Greek Navy General Staff, and occupied the post of Mi ...

, determined to oppose disarmament and the surrender of any war materials to the Allies.

The Allies' pressure on the government of Athens continued. On the next day, 24 November, du Fournet presented a new ultimatum ending on 1 December to the government of Athens demanding the immediate surrender of at least ten mountain batteries.

[Leon, 1974, p. 434] The admiral made a last effort to persuade the king to accept France's demands. He advised the king that according to his orders he would land an Allied contingent, with aim to occupy certain positions in Athens until his demands were satisfied.

[ In reply, the King claimed that he was pressed by the army and the people not to submit to disarmament, and refused to make any commitment. However, he promised that the Greek forces would receive orders not to fire against the Allied contingent.][Leon, 1974, p. 435] Despite the gravity of the situation both the royalist government and the Allies let the events take their own course. The royalist government decided to reject the admiral's demands on 29 November and armed resistance was organised. By 30 November military units and royalist militia (the ''epistratoi'', "reservists") from surrounding areas have been recalled and gathered in and around Athens (in total over 20,000 men) and occupied strategic positions, with orders not to fire unless fired upon. The Allies landed a small contingent in Athens on . However, it met organized resistance and an armed confrontation took place for a day till a compromise was reached. After the evacuation of the Allied contingent from Athens the following day, a royalist mob raged though the city for three days targeting supporters of Venizelos. The incident became known as the Noemvriana in Greece, which was using the

The Allies landed a small contingent in Athens on . However, it met organized resistance and an armed confrontation took place for a day till a compromise was reached. After the evacuation of the Allied contingent from Athens the following day, a royalist mob raged though the city for three days targeting supporters of Venizelos. The incident became known as the Noemvriana in Greece, which was using the Old Style calendar

Old Style (O.S.) and New Style (N.S.) indicate dating systems before and after a calendar change, respectively. Usually, this is the change from the Julian calendar to the Gregorian calendar as enacted in various European countries between 158 ...

at the time, and drove a deep wedge between the Venizelists and their political opponents, deepening what would become known as the National Schism

The National Schism ( el, Εθνικός Διχασμός, Ethnikós Dichasmós), also sometimes called The Great Division, was a series of disagreements between King Constantine I and Prime Minister Eleftherios Venizelos regarding the foreig ...

.

After the armed confrontation in Athens, on , Britain and France officially recognised the government under Venizelos as the lawful government, effectively splitting Greece into two separate entities. On , Venizelos' provisional government officially declared war on the Central Powers. In reply, a royal warrant for the arrest of Venizelos was issued and the Archbishop of Athens

The Archbishopric of Athens ( el, Ιερά Αρχιεπισκοπή Αθηνών) is a Greek Orthodox archiepiscopal see based in the city of Athens, Greece. It is the senior see of Greece, and the seat of the autocephalous Church of Greece. It ...

, under pressure by the royal house, anathema

Anathema, in common usage, is something or someone detested or shunned. In its other main usage, it is a formal excommunication. The latter meaning, its ecclesiastical sense, is based on New Testament usage. In the Old Testament, anathema was a cr ...

tised him. The Allies unwilling to risk a new fiasco, but determined to solve the problem, established a naval blockade around southern Greece, which was still loyal to the king, and that caused extreme hardship to people in those areas.[Clogg, 2002, p. 89] In June France and Great Britain decided to invoke their obligation as ''"protecting powers"'', who had promised to guarantee a constitutional form for Greece at the time the Kingdom was created, to demand the king's resignation. Constantine accepted and on 15 June 1917 went to exile, leaving his son Alexander on the throne as demanded (whom the Allies considered as pro-Entente), instead of his elder son and crown prince, George

George may refer to:

People

* George (given name)

* George (surname)

* George (singer), American-Canadian singer George Nozuka, known by the mononym George

* George Washington, First President of the United States

* George W. Bush, 43rd Presid ...

.["Land of Invasion"](_blank)

''Time'', 4 November 1940. His departure was followed by the deportation of many prominent royalists, especially army officers such as Ioannis Metaxas

Ioannis Metaxas (; el, Ιωάννης Μεταξάς; 12th April 187129th January 1941) was a Greek military officer and politician who served as the Prime Minister of Greece from 1936 until his death in 1941. He governed constitutionally for t ...

, to exile in France and Italy.

The course of events paved the way for Venizelos to return in Athens on 29 May 1917 and Greece, now unified, officially entered the war on the side of the Allies. Subsequently, the entire Greek army was mobilized (though tensions remained inside the army between supporters of the monarchy

A monarchy is a government#Forms, form of government in which a person, the monarch, is head of state for life or until abdication. The legitimacy (political)#monarchy, political legitimacy and authority of the monarch may vary from restric ...

and supporters of Venizelos) and began to participate in military operations against the Central Powers

The Central Powers, also known as the Central Empires,german: Mittelmächte; hu, Központi hatalmak; tr, İttifak Devletleri / ; bg, Централни сили, translit=Tsentralni sili was one of the two main coalitions that fought in ...

army on the Macedonian front.

Conclusion of World War I

By the fall of 1918, the Greek army numbering 300,000 soldiers, was the largest single national component of the Allied army in the Macedonian front. The presence of the entire Greek army gave the critical mass that altered the balance between the opponents in the Macedonian front. Under the command of French General Franchet d'Espèrey, a combined Greek, Serbian, French and British force launched a major offensive against the Bulgarian and German army, starting on 14 September 1918. After the first heavy fighting (see Battle of Skra) the Bulgarians gave up their defensive positions and began retreating back towards their country. On 24 September the Bulgarian government asked for an

By the fall of 1918, the Greek army numbering 300,000 soldiers, was the largest single national component of the Allied army in the Macedonian front. The presence of the entire Greek army gave the critical mass that altered the balance between the opponents in the Macedonian front. Under the command of French General Franchet d'Espèrey, a combined Greek, Serbian, French and British force launched a major offensive against the Bulgarian and German army, starting on 14 September 1918. After the first heavy fighting (see Battle of Skra) the Bulgarians gave up their defensive positions and began retreating back towards their country. On 24 September the Bulgarian government asked for an armistice

An armistice is a formal agreement of warring parties to stop fighting. It is not necessarily the end of a war, as it may constitute only a cessation of hostilities while an attempt is made to negotiate a lasting peace. It is derived from the ...

, which was signed five days later. The Allied army then pushed north and defeated the remaining German and Austrian forces that tried to halt the Allied offensive. By October 1918 the Allied armies had recaptured all of Serbia and were preparing to invade Hungary. The offensive was halted because the Hungarian leadership offered to surrender in November 1918 marking the dissolution of the Austro-Hungarian empire. The breaking of the Macedonian front was one of the important breakthroughs of the military stalemate and helped to bring an end to the War. Greece was granted a seat at the Paris Peace Conference under Venizelos.

Treaty of Sèvres and assassination attempt

Following the conclusion of World War I, Venizelos took part in the Paris Peace Conference of 1919 as Greece's chief representative. During his absence from Greece for almost two years, he acquired a reputation as an international statesman of considerable stature.

Following the conclusion of World War I, Venizelos took part in the Paris Peace Conference of 1919 as Greece's chief representative. During his absence from Greece for almost two years, he acquired a reputation as an international statesman of considerable stature.Woodrow Wilson

Thomas Woodrow Wilson (December 28, 1856February 3, 1924) was an American politician and academic who served as the 28th president of the United States from 1913 to 1921. A member of the Democratic Party, Wilson served as the president of ...

was said to have placed Venizelos first in point of personal ability among all delegates gathered in Paris to settle the terms of Peace.

In July 1919, Venizelos reached an agreement with the Italians on the cession of the Dodecanese, and secured an extension of the Greek area in the periphery of Smyrna

Smyrna ( ; grc, Σμύρνη, Smýrnē, or , ) was a Greek city located at a strategic point on the Aegean coast of Anatolia. Due to its advantageous port conditions, its ease of defence, and its good inland connections, Smyrna rose to promi ...

. The Treaty of Neuilly

The Treaty of Neuilly-sur-Seine (french: Traité de Neuilly-sur-Seine) required Bulgaria to cede various territories, after Bulgaria had been one of the Central Powers defeated in World War I. The treaty was signed on 27 November 1919 at Neuilly ...

with Bulgaria on 27 November 1919, and the Treaty of Sèvres

The Treaty of Sèvres (french: Traité de Sèvres) was a 1920 treaty signed between the Allies of World War I and the Ottoman Empire. The treaty ceded large parts of Ottoman territory to France, the United Kingdom, Greece and Italy, as well ...

with the Ottoman Empire on 10 August 1920, were triumphs both for Venizelos and for Greece.[Kitromilides, 2006, p. 165][Chester, 1921, p. 320] As the result of these treaties, Greece acquired Western Thrace