ElŇľbieta Sieniawska on:

[Wikipedia]

[Google]

[Amazon]

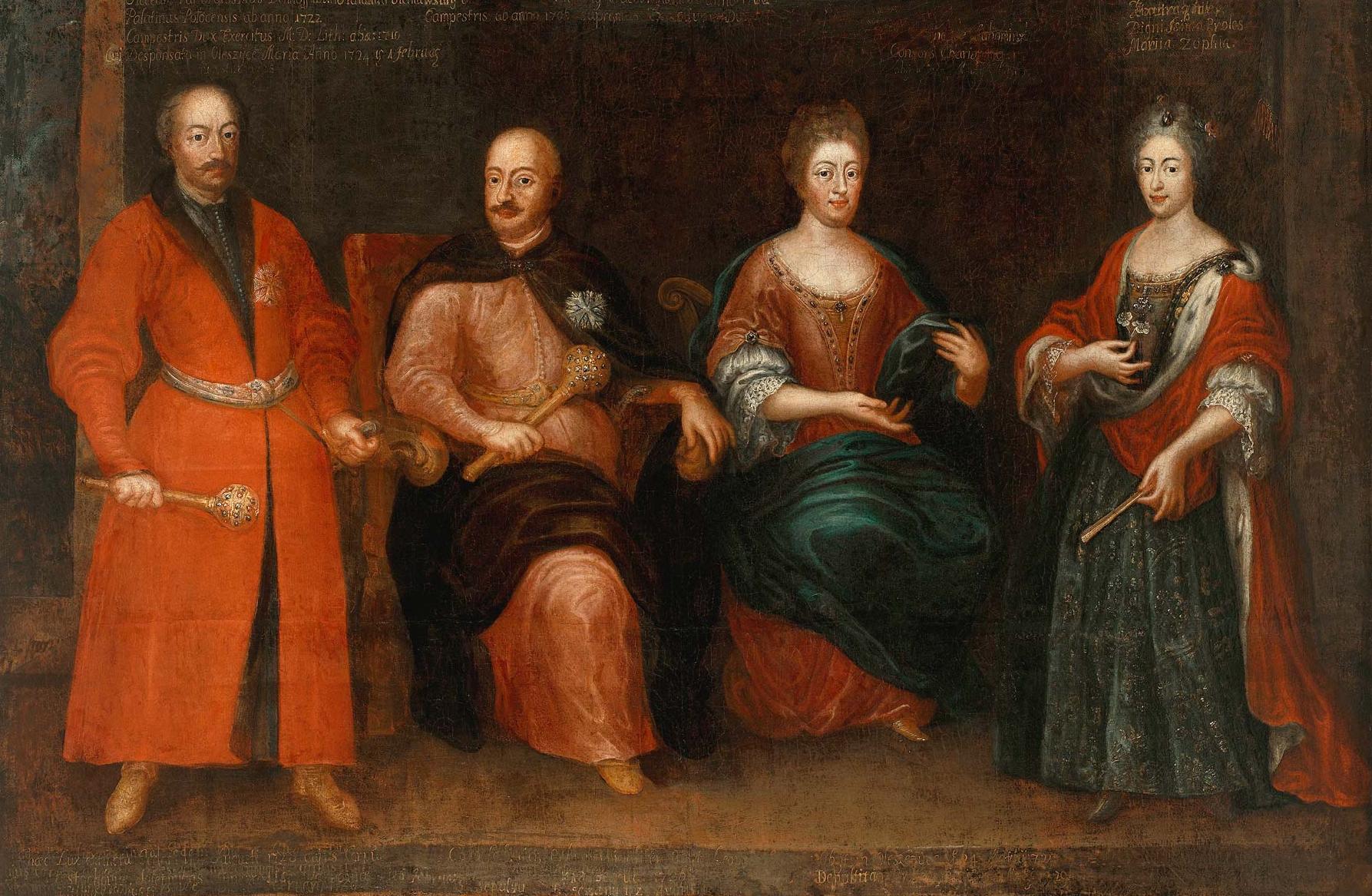

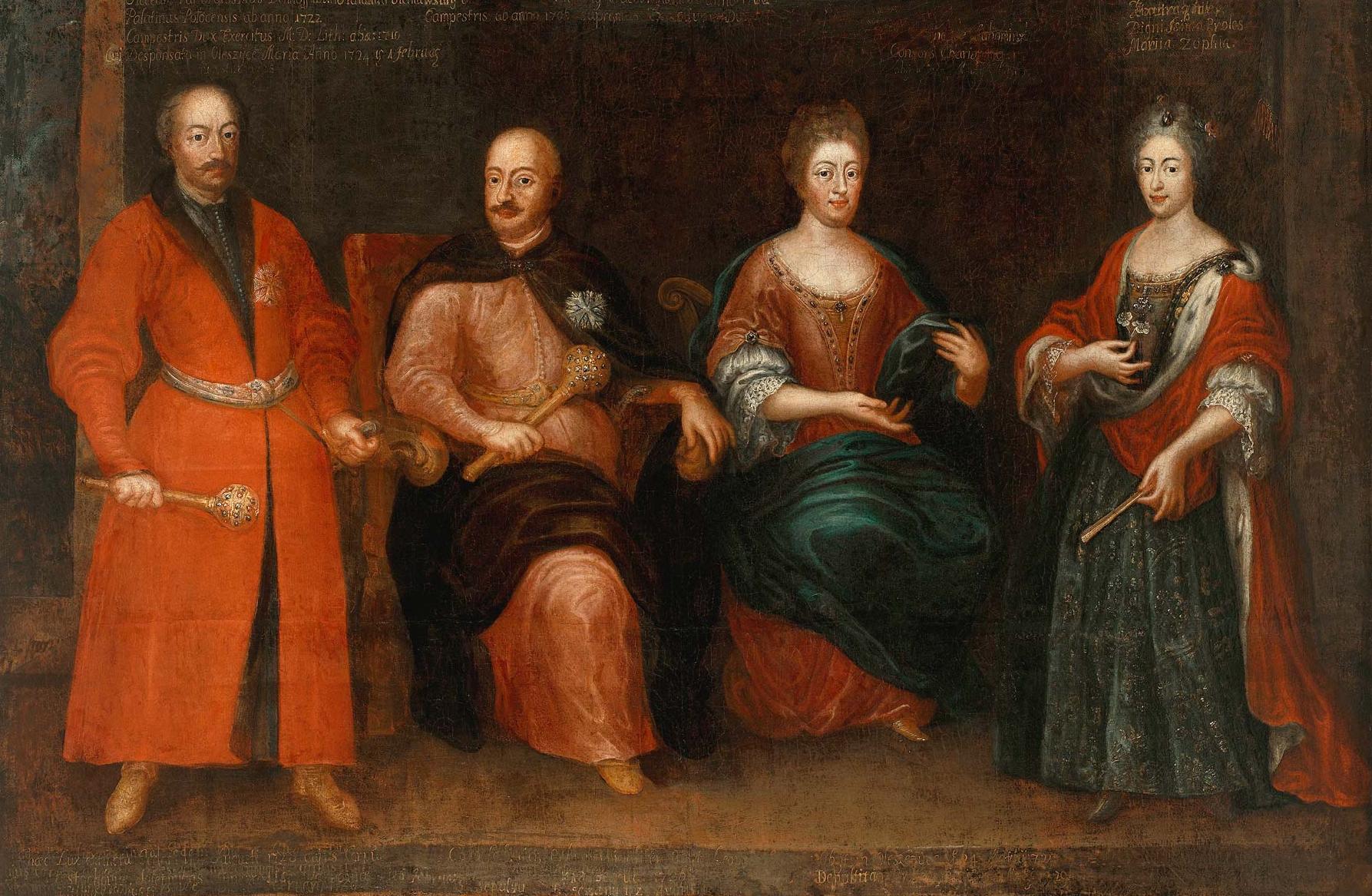

ElŇľbieta Helena Sieniawska, ''n√©e'' Lubomirska (

The hetmaness was "a lady of great wisdom, reason and shrewdness" and she was deployed by her husband on diplomatic missions, duties and obligations that he could not cope with. Otwinowski called her "a great owner of such shrewdness that she had meetings with the whole of Europe". Others called her "a great ruler and the First Lady of the Republic" and Augustus II had her portrait amid the effigies of distinguished women. After

The hetmaness was "a lady of great wisdom, reason and shrewdness" and she was deployed by her husband on diplomatic missions, duties and obligations that he could not cope with. Otwinowski called her "a great owner of such shrewdness that she had meetings with the whole of Europe". Others called her "a great ruler and the First Lady of the Republic" and Augustus II had her portrait amid the effigies of distinguished women. After  In 1706, after Augustus II's abdication, she engaged in the negotiations to reach an agreement between the tsar

In 1706, after Augustus II's abdication, she engaged in the negotiations to reach an agreement between the tsar

In the following years, the hetmaness retired from politics, and concentrated on administration of her vast estates and their economic development. In one of her letters of 17 July 1726 Sieniawska reprimanded an accountant in the

In the following years, the hetmaness retired from politics, and concentrated on administration of her vast estates and their economic development. In one of her letters of 17 July 1726 Sieniawska reprimanded an accountant in the  She also focused on constructional foundations. In 1720, she established the new

She also focused on constructional foundations. In 1720, she established the new

Through her extensive contacts from Neuburg court, through

Through her extensive contacts from Neuburg court, through  In 1713, the king Augustus II purchased the Morsztyn Palace and neighbouring allotments and started the construction of a new palace ‚Äď so called

In 1713, the king Augustus II purchased the Morsztyn Palace and neighbouring allotments and started the construction of a new palace ‚Äď so called

RzńÖdzicha oleszycka. Dw√≥r ElŇľbiety z Lubomirskich Sieniawskiej jako przykŇāad patronatu kobiecego w czasach saskich

Kraków 2014.

Lubomirski family

The Learned Ladies

{{DEFAULTSORT:Sieniawska, Elzbieta 1669 births 1729 deaths Elzbieta Lubomirski family Polish women in politics Mistresses of Polish royalty Mistresses of Hungarian royalty Polish people of the Great Northern War Polish landscape and garden designers 17th-century Polish women 18th-century Polish women Polish ladies-in-waiting 18th-century philanthropists Polish philanthropists

KoŇĄskowola

KoŇĄskowola is a village in southeastern Poland (historic Lesser Poland region), located between PuŇāawy and Lublin, near Kur√≥w on the Kur√≥wka River. It is the seat of a separate commune (''gmina'') within PuŇāawy County in Lublin Voivodeship, ...

, 1669 ‚Äď 21 March 1729, Oleszyce

Oleszyce ( uk, –ě–Ľ–Ķ—ą–ł—á—Ė, ''Oleshychi'') is a small town in Subcarpathian Voivodeship, Poland, with 3,089 inhabitants (02.06.2009).

History

The history of Oleszyce dates back to the early 15th century, when the village belonged to Poland's ...

), was a Polish noblewoman

Nobility is a social class found in many societies that have an aristocracy (class), aristocracy. It is normally ranked immediately below Royal family, royalty. Nobility has often been an Estates of the realm, estate of the realm with many e ...

, Grand Hetmaness of the Crown (''hetmanowa wielka koronna''), and a renowned patron of the arts

Patronage is the support, encouragement, privilege, or financial aid that an organization or individual bestows on another. In the history of art, arts patronage refers to the support that kings, popes, and the wealthy have provided to artists su ...

.

An influential woman politician

A politician is a person active in party politics, or a person holding or seeking an elected office in government. Politicians propose, support, reject and create laws that govern the land and by an extension of its people. Broadly speaking, a ...

in the Polish‚ÄďLithuanian Commonwealth

The Polish‚ÄďLithuanian Commonwealth, formally known as the Kingdom of Poland and the Grand Duchy of Lithuania, and, after 1791, as the Commonwealth of Poland, was a bi-confederal state, sometimes called a federation, of Crown of the Kingdom of ...

during the reign of Augustus II the Strong

Augustus II; german: August der Starke; lt, Augustas II; in Saxony also known as Frederick Augustus I ‚Äď Friedrich August I (12 May 16701 February 1733), most commonly known as Augustus the Strong, was Elector of Saxony from 1694 as well as Ki ...

, she was deeply embroiled in the Great Northern War

The Great Northern War (1700‚Äď1721) was a conflict in which a coalition led by the Tsardom of Russia successfully contested the supremacy of the Swedish Empire in Northern, Central and Eastern Europe. The initial leaders of the anti-Swedi ...

and in Rákóczi's War for ungarianIndependence.

She was considered the most powerful woman in the Commonwealth and was called "the uncrowned Queen of Poland".

Biography

Early life

ElŇľbieta was the only child of Prince StanisŇāaw Herakliusz Lubomirski by his first wife Countess Zofia OpaliŇĄska. Her father, a neostoic known as the ''PolishSolomon

Solomon (; , ),, ; ar, ō≥ŔŹŔĄŔéŔäŔíŔÖŔéōßŔÜ, ', , ; el, ő£őŅőĽőŅőľŌéőĹ, ; la, Salomon also called Jedidiah (Hebrew language, Hebrew: , Modern Hebrew, Modern: , Tiberian Hebrew, Tiberian: ''YńÉŠłŹńꊳŹńÉyńĀh'', "beloved of Yahweh, Yah"), ...

'', had a great influence on her education and politics. After her father's death she inherited many of his estates, including PuŇāawy

PuŇāawy (, also written Pulawy) is a city in eastern Poland, in Lesser Poland's Lublin Voivodeship, at the confluence of the Vistula and Kur√≥wka Rivers. PuŇāawy is the capital of PuŇāawy County. The city's 2019 population was estimated at 47,417 ...

, ŇĀubnice, Siekierki

Siekierki is a neighborhood in the Mokotów district of Warsaw, Poland. It's a sparsely inhabited and poorly developed area located beside the Vistula

The Vistula (; pl, WisŇāa, ) is the longest river in Poland and the ninth-longest river i ...

, Czerniaków

Czerniaków is a neighbourhood of the city of Warsaw, located within the borough of Mokotów, between the escarpment of the Vistula river and the river itself.

Called ''Czerniakowo'' since the Middle Ages, it was then merely a small village loca ...

and many other properties in Warsaw. She was educated in the Visitationist Sisters boarding-school in Warsaw

Warsaw ( pl, Warszawa, ), officially the Capital City of Warsaw,, abbreviation: ''m.st. Warszawa'' is the capital and largest city of Poland. The metropolis stands on the River Vistula in east-central Poland, and its population is officia ...

and in 1680 she was admitted at the court as a lady-in-waiting

A lady-in-waiting or court lady is a female personal assistant at a court, attending on a royal woman or a high-ranking noblewoman. Historically, in Europe, a lady-in-waiting was often a noblewoman but of lower rank than the woman to whom sh ...

of Queen Marie Casimire

Marie Casimire Louise de La Grange d'Arquien ( pl, Maria Kazimiera Ludwika d‚ÄôArquien; 28 June 1641 ‚Äď 30 January 1716), known also by the diminutive form "MarysieŇĄka", was a French noblewoman who became the queen consort of Poland and grand ...

. In 1687, she married Adam MikoŇāaj Sieniawski

Adam MikoŇāaj Sieniawski (1666–1726) was a Polish nobleman, aristocrat and military leader.

He was the son of Hetman MikoŇāaj Hieronim Sieniawski and Cecylia Maria RadziwiŇāŇā, daughter of Court and Grand Marshal Prince Aleksander Ludwik R ...

, Grand Hetman of the Crown

( uk, –≥–Ķ—ā—Ć–ľ–į–Ĺ, translit=het'man) is a political title from Central and Eastern Europe, historically assigned to military commanders.

Used by the Czechs in Bohemia since the 15th century. It was the title of the second-highest military co ...

, and despite her husband's demands she stayed in Warsaw, where she got involved in a famed romance with Jan StanisŇāaw JabŇāonowski

Jan StanisŇāaw JabŇāonowski of the Prus III coat of arms (1669 - 28 April 1731 in Lviv) was a Polish political writer who was a maternal uncle of King StanisŇāaw I LeszczyŇĄski, under whom he served as Crown Chancellor in 1706‚Äď09. He also hel ...

. She was reconciled with her husband, but soon after, her affair with Aleksander Benedykt Sobieski

Aleksander Benedykt StanisŇāaw Sobieski (; 9 September 1677 ‚Äď 16 November 1714) was a Polish prince, nobleman, diplomat, writer, scholar and the son of John III Sobieski, King of Poland, and his wife, Marie Casimire Louise de la Grange d'Arquien ...

became well known. Her financial independence caused conflict with her husband and she was forced to defend her property and income from his interference. Eventually, the hetmaness achieved equilibrium within their marriage, and sometimes even underlined her leadership role in their intimate relations addressing Sieniawski as ''My dear Maiden'' in her letters. Monsieur de Mongrillon, secretary of the French Embassy in the period 1694‚Äď1698, recalled in his memoirs: ''she is a true Amazon

Amazon most often refers to:

* Amazons, a tribe of female warriors in Greek mythology

* Amazon rainforest, a rainforest covering most of the Amazon basin

* Amazon River, in South America

* Amazon (company), an American multinational technology c ...

..She smokes like a man. It is said that the Tatar ambassador who came to Poland with peace overtures came to smoke by her bed and she smoked with him''.

Stateswoman

John III Sobieski

John III Sobieski ( pl, Jan III Sobieski; lt, Jonas III Sobieskis; la, Ioannes III Sobiscius; 17 August 1629 ‚Äď 17 June 1696) was King of Poland and Grand Duke of Lithuania from 1674 until his death in 1696.

Born into Polish nobility, Sobie ...

's death she supported the French candidature of François Louis, Prince of Conti

Fran√ßois Louis de Bourbon, ''le Grand Conti'' (30 April 1664 ‚Äď 22 February 1709),

for the Polish throne and became a leader of his party. When she became disillusioned with his candidature, she affiliated with Augustus II. After Queen Marie Casimire's departure to Rome

, established_title = Founded

, established_date = 753 BC

, founder = King Romulus (legendary)

, image_map = Map of comune of Rome (metropolitan city of Capital Rome, region Lazio, Italy).svg

, map_caption ...

, she administered her widow dowry

A dowry is a payment, such as property or money, paid by the bride's family to the groom or his family at the time of marriage. Dowry contrasts with the related concepts of bride price and dower. While bride price or bride service is a payment b ...

in Warsaw. Between 1701 and 1703, due to incitement of the French diplomacy, she was involved in the anti-Habsburg

The House of Habsburg (), alternatively spelled Hapsburg in Englishgerman: Haus Habsburg, ; es, Casa de Habsburgo; hu, Habsburg család, it, Casa di Asburgo, nl, Huis van Habsburg, pl, dom Habsburgów, pt, Casa de Habsburgo, la, Domus Hab ...

insurrection

Rebellion, uprising, or insurrection is a refusal of obedience or order. It refers to the open resistance against the orders of an established authority.

A rebellion originates from a sentiment of indignation and disapproval of a situation and ...

in Hungary

Hungary ( hu, Magyarorsz√°g ) is a landlocked country in Central Europe. Spanning of the Carpathian Basin, it is bordered by Slovakia to the north, Ukraine to the northeast, Romania to the east and southeast, Serbia to the south, Croatia a ...

, which she financially and politically supported. The rebellion's leader Francis II Rákóczi

Francis II R√°k√≥czi ( hu, II. R√°k√≥czi Ferenc, ; 27 March 1676 ‚Äď 8 April 1735) was a Hungarian nobleman and leader of R√°k√≥czi's War of Independence against the Habsburgs in 1703‚Äď11 as the prince ( hu, fejedelem) of the Estates Confedera ...

, Prince of Transylvania

The Prince of Transylvania ( hu, erd√©lyi fejedelem, german: F√ľrst von Siebenb√ľrgen, la, princeps Transsylvaniae, ro, principele TransilvanieiFallenb√ľchl 1988, p. 77.) was the head of state of the Principality of Transylvania from the last d ...

, became her lover. In the Sieniawskis' estate in Berezhany

Berezhany ( uk, –Ď–Ķ—Ä–Ķ–∂–į–Ĺ–ł, ; pl, BrzeŇľany; yi, ◊Ď◊®◊Ę◊Ė◊©◊ź÷∑◊ü, Brezhan; he, ◊Ď÷ľ◊Ė'◊ô◊Ė'◊ź◊†◊ô/◊Ď÷ľ◊Ė'◊Ė'◊†◊ô ''Bzhezhani''/''Bzhizhani'') is a city in Ternopil Raion, Ternopil Oblast (province) of western Ukraine. It lies about fr ...

, Rákóczi issued a proclamation

A proclamation (Lat. ''proclamare'', to make public by announcement) is an official declaration issued by a person of authority to make certain announcements known. Proclamations are currently used within the governing framework of some nations ...

''To all Hungarians'' considered as the beginning of the uprising. Their discreet romance flourished in the turbulent years of war. He wrote a madrigal

A madrigal is a form of secular vocal music most typical of the Renaissance (15th‚Äď16th c.) and early Baroque (1600‚Äď1750) periods, although revisited by some later European composers. The polyphonic madrigal is unaccompanied, and the number o ...

in French dedicated to the hetmaness and his love letters are interesting examples of epistolography

Epistolography, or the art of writing letters, is a genre of Byzantine literature similar to rhetoric that was popular with the intellectual elite of the Byzantine age."Epistolography" in ''The Oxford Dictionary of Byzantium'', Oxford University P ...

. When in 1704, Jakub and Konstanty Sobieskis were kidnapped and imprisoned in Saxony

Saxony (german: Sachsen ; Upper Saxon: ''Saggsn''; hsb, Sakska), officially the Free State of Saxony (german: Freistaat Sachsen, links=no ; Upper Saxon: ''Freischdaad Saggsn''; hsb, Swobodny stat Sakska, links=no), is a landlocked state of ...

, Aleksander resigned from the rivalry for the crown, afraid of revenge from his former lover (at that time Wettin partisan).

In 1706, after Augustus II's abdication, she engaged in the negotiations to reach an agreement between the tsar

In 1706, after Augustus II's abdication, she engaged in the negotiations to reach an agreement between the tsar Peter I of Russia

Peter I ( ‚Äď ), most commonly known as Peter the Great,) or Pyotr Aleks√©yevich ( rus, –ü—Ď—ā—Ä –ź–Ľ–Ķ–ļ—Ā–ĶŐĀ–Ķ–≤–ł—á, p=ňąp ≤…Ķtr …źl ≤…™ňąks ≤ej…™v ≤…™t…ē, , group=pron was a Russian monarch who ruled the Tsardom of Russia from t ...

and king Charles XII of Sweden

Charles XII, sometimes Carl XII ( sv, Karl XII) or Carolus Rex (17 June 1682 ‚Äď 30 November 1718 O.S.), was King of Sweden (including current Finland) from 1697 to 1718. He belonged to the House of Palatinate-Zweibr√ľcken, a branch line of t ...

. During the negotiations she met with her former lover JabŇāonowski, King LeszczyŇĄski

The House of LeszczyŇĄski ( , ; plural: LeszczyŇĄscy, feminine form: LeszczyŇĄska) was a prominent Polish noble family. They were magnates in the Polish‚ÄďLithuanian Commonwealth and later became royal family of Poland.

History

The LeszczyŇĄski ...

's envoy. Sieniawska was abducted in November 1707 by the Swedish Army and met with the king himself. She was released after a month due to French mediation. After Augustus' abdication

Abdication is the act of formally relinquishing monarchical authority. Abdications have played various roles in the succession procedures of monarchies. While some cultures have viewed abdication as an extreme abandonment of duty, in other societ ...

Sieniawska's husband become one of the most significant players in the struggle for Polish crown. He was considered as one of the leaders of the Sandomierz Confederation

The Sandomierz Confederation was an anti-Swedish confederation, formed on 20 May 1704 in defense of the King of Poland, August II the Strong. It was formed in reaction to the Warsaw Confederation, and its marshal was StanisŇāaw Ernest Denhoff. The ...

, and starting from 1707 he negotiated with the Tsar Peter I his own candidature to the throne. But his wife strongly opposed his candidacy and threatened him with divorce

Divorce (also known as dissolution of marriage) is the process of terminating a marriage or marital union. Divorce usually entails the canceling or reorganizing of the legal duties and responsibilities of marriage, thus dissolving the ...

. She did however support the candidature of her lover Francis Rákóczi as the most appropriate in a very difficult political situation of the ''Serenissima

aSerenissima ( heMost Serene) may refer to:

Certain countries

* , a name for the Republic of Venice

* , the official Latin name of the Polish‚ÄďLithuanian Commonwealth

Art, entertainment, and media

* La Serenissima (musical ensemble), a British ...

''. With a support of a French diplomat Jean Victor de Besenval she was involved in peace mediations. After the declaration of interregnum

An interregnum (plural interregna or interregnums) is a period of discontinuity or "gap" in a government, organization, or social order. Archetypally, it was the period of time between the reign of one monarch and the next (coming from Latin '' ...

in the Commonwealth in July 1707 an agreement was reached and on 8 August 1707 the Lublin

Lublin is the ninth-largest city in Poland and the second-largest city of historical Lesser Poland. It is the capital and the center of Lublin Voivodeship with a population of 336,339 (December 2021). Lublin is the largest Polish city east of t ...

Council was appointed. Because of robberies and other abuses by Russian troops, Sejm

The Sejm (English: , Polish: ), officially known as the Sejm of the Republic of Poland (Polish: ''Sejm Rzeczypospolitej Polskiej''), is the lower house of the bicameral parliament of Poland.

The Sejm has been the highest governing body of t ...

began to enforce the Sieniawska's protegee. When those plans failed, she endeavoured to legalise LeszczyŇĄski's election and to remove all foreign troops from the country. In her politics, she also aimed to reduce the Russian influences in the Commonwealth. She was an unscrupulous politician participating in political affairs on a large scale, establishing secret contacts with different camps and conducting various personal intrigues ‚Äď Charles XII of Sweden referred to her as "that most accursed woman".

Since 1709, she fostered Konstanty's candidature to the throne (he visited her together with StanisŇāaw LeszczyŇĄksi in Lviv

Lviv ( uk, –õ—Ć–≤—Ė–≤) is the largest city in western Ukraine, and the seventh-largest in Ukraine, with a population of . It serves as the administrative centre of Lviv Oblast and Lviv Raion, and is one of the main cultural centres of Ukraine ...

in Spring 1709), and though she was against the Wettin restoration, she could accommodate to Augustus II being already in possession of the Polish crown. To the baptism of her only daughter in 1711 in JarosŇāaw

JarosŇāaw (; uk, –Į—Ä–ĺ—Ā–Ľ–į–≤, Yaroslav, ; yi, ◊ô◊ź÷∑◊®◊Ę◊°◊ú◊ź÷ł◊ē◊ē, Yareslov; german: Jaroslau) is a town in south-eastern Poland, with 38,970 inhabitants, as of 30 June 2014. Situated in the Subcarpathian Voivodeship (since 1999), previ ...

she invited the powerful of the age. Among the godparents were Tsar Peter I, King Augustus II and prince Rákóczi, accompanied by about 15000 soldiers. The tsar Peter I was attracted by her unusual intelligence and it is believed that she became his mistress. During his stay in Jaworów in May 1711, according to the French ambassador ''Sieur'' Baluze, they talked endlessly and built a boat together.

Later life

In the following years, the hetmaness retired from politics, and concentrated on administration of her vast estates and their economic development. In one of her letters of 17 July 1726 Sieniawska reprimanded an accountant in the

In the following years, the hetmaness retired from politics, and concentrated on administration of her vast estates and their economic development. In one of her letters of 17 July 1726 Sieniawska reprimanded an accountant in the Tenczyn Castle

Tenczyn Castle, also known as ''Tńôczyn Castle'', is a medieval castle in the village of Rudno in the Polish Jura, Poland. It was built as a seat of the powerful TńôczyŇĄski family. The castle fell into disrepair during the Deluge in mid-17th cen ...

, ''Monsieur'' ZabagŇāowicz: Among her close collaborators were KoŇĄskowola canon

Canon or Canons may refer to:

Arts and entertainment

* Canon (fiction), the conceptual material accepted as official in a fictional universe by its fan base

* Literary canon, an accepted body of works considered as high culture

** Western can ...

Andrzej StanisŇāaw Tucci and a Jewish woman Feyga Leybowiczowa, to whom she entrusted the management of mills and inns in KoŇĄskowola. She also supported Jewish settlement on her lands (on 2 May 1718 she issued a privilege for the Jews to settle in Stasz√≥w and build a synagogue

A synagogue, ', 'house of assembly', or ', "house of prayer"; Yiddish: ''shul'', Ladino: or ' (from synagogue); or ', "community". sometimes referred to as shul, and interchangeably used with the word temple, is a Jewish house of worshi ...

).

She also focused on constructional foundations. In 1720, she established the new

She also focused on constructional foundations. In 1720, she established the new orangery

An orangery or orangerie was a room or a dedicated building on the grounds of fashionable residences of Northern Europe from the 17th to the 19th centuries where orange and other fruit trees were protected during the winter, as a very large ...

of the Wilan√≥w Palace, in 1722 she started the reconstruction of the PuŇāawy Palace and in 1730 she enlarged the ŇĀubnice Palace, at that time artistic center of Sieniawska's properties. From Konstanty she purchased Olesko

Olesko ( uk, –ě–Ľ–Ķ—Ā—Ć–ļ–ĺ; ; pl, Olesko; yi, ◊ź÷∑◊ú◊Ę◊°◊ß, Alesk; ) is an urban-type settlement in Zolochiv Raion, Lviv Oblast (region) of western Ukraine. It belongs to Busk urban hromada, one of the hromadas of Ukraine. Population: .

It w ...

and Ternopil

Tern√≥pil ( uk, –Ę–Ķ—Ä–Ĺ–ĺ–Ņ—Ė–Ľ—Ć, Ternopil' ; pl, Tarnopol; yi, ◊ė◊ź÷∑◊®◊†◊ź÷ł◊§÷ľ◊ú, Tarnopl, or ; he, ◊ė◊ź◊®◊†◊ē◊§◊ē◊ú (◊ė÷∑◊®÷į◊†◊ē÷Ļ◊§÷ľ◊ē÷Ļ◊ú), Tarnopol; german: Tarnopol) is a city in the west of Ukraine. Administratively, Ternopi ...

and in 1720 the Sobieskis ''colifichet de gentillesse'' (the most pleasant trinket) ‚Äď Wilan√≥w Palace

Wilan√≥w Palace ( pl, PaŇāac w Wilanowie, ) is a former royal palace located in the Wilan√≥w district of Warsaw, Poland. Wilan√≥w Palace survived Poland's partitions and both World Wars, and so serves as a reminder of the culture of the Polish ...

. Among her most notable foundations are the church and monastery for the Capuchin friars

The Order of Friars Minor Capuchin (; postnominal abbr. O.F.M. Cap.) is a religious order of Franciscan friars within the Catholic Church, one of Three " First Orders" that reformed from the Franciscan Friars Minor Observant (OFM Obs., now OFM) ...

in Lviv founded in 1708 and accomplished in 1718, the wooden mansion in Oleszyce

Oleszyce ( uk, –ě–Ľ–Ķ—ą–ł—á—Ė, ''Oleshychi'') is a small town in Subcarpathian Voivodeship, Poland, with 3,089 inhabitants (02.06.2009).

History

The history of Oleszyce dates back to the early 15th century, when the village belonged to Poland's ...

(1713), a palace-orangery in Sieniawa

Sieniawa (; uk, –°–Ķ–Ĺ—ŹŐĀ–≤–į, Seni√°va), is a town in southeastern Poland. It had a population of 2,127 inhabitants (02.06.2009). Since 1999, Sieniawa has been part of Subcarpathian Voivodeship.

History

Sieniawa's history dates back to the 17 ...

(1718), the Discalced Carmelite Sisters Church in Lublin (before 1721), the palace in Wysocko (1720s), the two storied palace in PrzybysŇāawice (1720s), reconstruction of the Founding of Holy Cross Parish Church in KoŇĄskowola (1724), the St. Elisabeth's Church in Powsin (1725), reconstruction of the Lubomirski Palace in Lublin

Lublin is the ninth-largest city in Poland and the second-largest city of historical Lesser Poland. It is the capital and the center of Lublin Voivodeship with a population of 336,339 (December 2021). Lublin is the largest Polish city east of t ...

(1725‚Äď1728) ‚Äď some of them she erected together with her husband. When Sieniawska's daughter widowed in 1728 her new marriage become a significant matter, not only in the Commonwealth but also in Europe. After her father's death in 1726 Maria Zofia inherited his Ruthenian estates including 35 towns, 235 villages and Berezhany fortress, she was also the only inheritor of her husband's estates and of her mother's fortune. Among the candidates to the hand of one of the wealthiest women in Europe were Charles de Bourbon-Cond√©, Count of Charolais supported by France

France (), officially the French Republic ( ), is a country primarily located in Western Europe. It also comprises of Overseas France, overseas regions and territories in the Americas and the Atlantic Ocean, Atlantic, Pacific Ocean, Pac ...

(Louis XV

Louis XV (15 February 1710 ‚Äď 10 May 1774), known as Louis the Beloved (french: le Bien-Aim√©), was King of France from 1 September 1715 until his death in 1774. He succeeded his great-grandfather Louis XIV at the age of five. Until he reache ...

even invited Maria Zofia to Versailles

The Palace of Versailles ( ; french: Ch√Ęteau de Versailles ) is a former royal residence built by King Louis XIV located in Versailles, about west of Paris, France. The palace is owned by the French Republic and since 1995 has been managed, u ...

), Portuguese infante

''Infante'' (, ; f. ''infanta''), also anglicised as Infant or translated as Prince, is the title and rank given in the Iberian kingdoms of Spain (including the predecessor kingdoms of Aragon, Castile, Navarre, and León) and Portugal to t ...

Dom Manuel de Bragança supported by the Habsburgs (proposed as the next King of Poland, due to the tenets of the Löwenwolde's Treaty

The Treaty of the Three Black Eagles, or Treaty of Berlin, was a secret treaty signed in September and December 1732 between the Austrian Empire, the Russian Empire and Prussia.

It concerned the joint policy of the three powers regarding to the ...

), Jan Klemens Branicki

Count Jan Klemens Branicki (also known as Jan Kazimierz Branicki; 21 September 1689 ‚Äď 9 October 1771) was a Polish nobleman, magnate and Hetman, Field Crown Hetman of the Polish‚ÄďLithuanian Commonwealth between 1735 and 1752, and Great Crown ...

, Franciszek Salezy Potocki

Franciszek Salezy Potocki (1700–1772) was a Polish nobleman, diplomat, politician and knight of the Order of the White Eagle, awarded on August 3, 1750 in Warsaw. Potocki was the wealthiest magnate of his time and the owner of large propert ...

, Jan TarŇāo Jan TarŇāo may refer to the following Polish noblemen:

* Jan TarŇāo (d. 1550), standard-bearer of Lw√≥w

* Jan TarŇāo (d. 1572), cup-bearer of the Crown, starost of Pilzno

* Jan TarŇāo (1527‚Äď1587), voivode of Lublin, starost of ŇĀomŇľa and Pilzno

* ...

and August Aleksander Czartoryski

Prince August Aleksander Czartoryski (9 November 1697, Warsaw4 April 1782, Warsaw) was a member of the Polish nobility (), magnate. He is the founder of the Czartoryski family fortune.

Life

August became major-general of the Polish Army in 1729 ...

, who eventually won the competition full of duels and speech encounters due to support of Augustus II, as the latter was afraid of increase of power of his opponents.

Patronage

Through her extensive contacts from Neuburg court, through

Through her extensive contacts from Neuburg court, through Prague

Prague ( ; cs, Praha ; german: Prag, ; la, Praga) is the capital and largest city in the Czech Republic, and the historical capital of Bohemia. On the Vltava river, Prague is home to about 1.3 million people. The city has a temperate ...

, Vienna

en, Viennese

, iso_code = AT-9

, registration_plate = W

, postal_code_type = Postal code

, postal_code =

, timezone = CET

, utc_offset = +1

, timezone_DST ...

and WrocŇāaw

WrocŇāaw (; german: Breslau, or . ; Silesian German: ''Brassel'') is a city in southwestern Poland and the largest city in the historical region of Silesia. It lies on the banks of the River Oder in the Silesian Lowlands of Central Europe, rou ...

, the hetmaness brought to Poland many renowned artists. √Ād√°m M√°nyoki

√Ād√°m M√°nyoki (1673, Szokolya ‚Äď 6 August 1757, Dresden) was a Hungarian Baroque portrait painter.

Biography

He was the son of a Reformed pastor. The family was very poor, so he was apparently given into the care of a German staff officer ...

, Rákóczi's court painter

A court painter was an artist who painted for the members of a royal or princely family, sometimes on a fixed salary and on an exclusive basis where the artist was not supposed to undertake other work. Painters were the most common, but the cour ...

, before he was appointed official court painter of Augustus II was at Sieniawska's service in Warsaw since 1713. She employed the most prominent artists active in the Commonwealth. Among them there were architects Giovanni Spazzio, J√≥zef Fontana, Karol Bay, Efraim Szreger and FrantiŇ°ek Mayer of Moravia

Moravia ( , also , ; cs, Morava ; german: link=yes, Mähren ; pl, Morawy ; szl, Morawa; la, Moravia) is a historical region in the east of the Czech Republic and one of three historical Czech lands, with Bohemia and Czech Silesia.

The me ...

, painters Jan Jerzy Plersch

Jan Jerzy Plersch also Johann Georg Plersch (1704 or 1705 – 1 January 1774) was a Polish sculptor of German origin.

The design of Plersch's sculptures refers to some extent to the so-called "School of Lviv" in sculpture. A symbolic tombston ...

and Giuseppe Rossi, eminent sculptors of Bohemian Baroque Jan Elij√°Ň° and Hynek Hoffmanns, stucco decorators Francesco Fumo and Pietro Innocente Comparetti, gardener

A gardener is someone who practices gardening, either professionally or as a hobby.

Description

A gardener is any person involved in gardening, arguably the oldest occupation, from the hobbyist in a residential garden, the home-owner suppleme ...

Georg Zeidler of Saxony. She also employed Dresden

Dresden (, ; Upper Saxon: ''Dr√§sdn''; wen, label=Upper Sorbian, DrjeŇĺdŇļany) is the capital city of the German state of Saxony and its second most populous city, after Leipzig. It is the 12th most populous city of Germany, the fourth larg ...

court artists such as Johann Sigmund Deybel, Louis de Silvestre

Louis de Silvestre (23 June 1675 – 11 April 1760) was a French portrait and history painter. He was court painter to King Augustus II of Poland, and director of the Royal Academy of Arts in Dresden.

Life and work

Sylvestre was born in Sc ...

and sculptor Jean-Joseph Vinache

Jean-Joseph Vinache (1696 ‚Äď 1 December 1754) was a French sculptor who served as the court sculptor to Augustus II, King of Poland and Elector of Saxony. Vinache's equestrian monument of Augustus, known as the "Gilded Horseman" (''Goldener Rei ...

and was a patron of young talented artists, like Julius Perty son of her architect Jacob, who was trained in Charles de Prevot's atelier in Sandomierz

Sandomierz (pronounced: ; la, Sandomiria) is a historic town in south-eastern Poland with 23,863 inhabitants (as of 2017), situated on the Vistula River in the Sandomierz Basin. It has been part of Ňöwińôtokrzyskie Voivodeship (Holy Cross Provi ...

between 1726 and 1730. Among her protegees was also a poet ElŇľbieta DruŇľbacka

ElŇľbieta DruŇľbacka (n√©e Kowalska, 1695 or 1698 ‚Äď March 14, 1765 in Tarn√≥w) was a Polish poet of the late Baroque

The Baroque (, ; ) is a style of architecture, music, dance, painting, sculpture, poetry, and other arts that flourished ...

known as the ''Sarmatian Muse''.

In 1713, the king Augustus II purchased the Morsztyn Palace and neighbouring allotments and started the construction of a new palace ‚Äď so called

In 1713, the king Augustus II purchased the Morsztyn Palace and neighbouring allotments and started the construction of a new palace ‚Äď so called Saxon Palace

The Saxons ( la, Saxones, german: Sachsen, ang, Seaxan, osx, Sahson, nds, Sassen, nl, Saksen) were a group of Germanic

*

*

*

*

peoples whose name was given in the early Middle Ages to a large country (Old Saxony, la, Saxonia) near the Nor ...

. Modelled after Versailles, it was the largest building in Warsaw, apart from the Sobieski's Marywil

Marywil (from French ''Ville de Marie'') was a large commercial centre and a palace in Warsaw, occupying roughly the place where the Grand Theatre stands today.

History

Marywil was built some time between 1692 and 1697 by Maria Kazimiera, the ...

. It was a time of late baroque and rococo, when ''theatrum mundi'', with its theatrical decorations played an essential role, not only in founder's glorification

Glorification may have several meanings in Christianity. From the Catholic canonization to the similar sainthood of the Eastern Orthodox Church to salvation in Christianity in Protestant beliefs, the glorification of the human condition can be a ...

but also in politics to confirm the status. That is why the facade of the new palace was considered as rather poor (all the major funds were intended to embellished the prince-elector

The prince-electors (german: Kurf√ľrst pl. , cz, KurfiŇôt, la, Princeps Elector), or electors for short, were the members of the electoral college that elected the emperor of the Holy Roman Empire.

From the 13th century onwards, the prince ...

's capital in Dresden, Germany). Sieniawska, who competed with the king in architectural foundations, choose an old Royal edifice ‚Äď the Visitationist Church

Church of St. Joseph of the Visitationists ( pl, KoŇõci√≥Ňā Opieki Ňõw. J√≥zefa w Warszawie) commonly known as the Visitationist Church ( pl, KoŇõci√≥Ňā Wizytek) is a Roman Catholic church in Warsaw, Poland, situated at '' Krakowskie PrzedmieŇõcie ...

established by Queen Marie Louise Gonzaga

Marie Louise Gonzaga ( pl, Ludwika Maria; 18 August 1611 ‚Äď 10 May 1667) was Queen of Poland and Grand Duchess of Lithuania by marriage to two kings of Poland and grand dukes of Lithuania, brothers WŇāadysŇāaw IV and John II Casimir. Together wi ...

, as her major propaganda

Propaganda is communication that is primarily used to influence or persuade an audience to further an agenda, which may not be objective and may be selectively presenting facts to encourage a particular synthesis or perception, or using loaded ...

investment in the capital. Probably the most important was its location at the Cracow Suburb Street, in front of the main entrance to the new royal residence, so everyone who visited the king must pass before the ornate Sieniawska's ''magnum opus''. She appointed her court architect Karol Bay to design a new rococo

Rococo (, also ), less commonly Roccoco or Late Baroque, is an exceptionally ornamental and theatrical style of architecture, art and decoration which combines asymmetry, scrolling curves, gilding, white and pastel colours, sculpted moulding, ...

facade profusely embellished with columns and sculptures.

The conservation and enlargement of the former residence of ''Victorious King'', John III Sobieski, is considered as her most significant achievement in the field of architecture. She embellished the palace facades and garden parterre

A ''parterre'' is a part of a formal garden constructed on a level substrate, consisting of symmetrical patterns, made up by plant beds, low hedges or coloured gravels, which are separated and connected by paths. Typically it was the part of ...

s with her coat of arms '' Szreniawa'' and monogram

A monogram is a motif made by overlapping or combining two or more letters or other graphemes to form one symbol. Monograms are often made by combining the initials of an individual or a company, used as recognizable symbols or logos. A series o ...

s. For the decoration of the palace's interiors she nominated an Italian fresco

Fresco (plural ''frescos'' or ''frescoes'') is a technique of mural painting executed upon freshly laid ("wet") lime plaster. Water is used as the vehicle for the dry-powder pigment to merge with the plaster, and with the setting of the plaste ...

painter Giuseppe Rossi, who adorned the chambers with ''trompe-l'Ňďil

''Trompe-l'Ňďil'' ( , ; ) is an artistic term for the highly realistic optical illusion of three-dimensional space and objects on a two-dimensional surface. ''Trompe l'oeil'', which is most often associated with painting, tricks the viewer into ...

'' paintings and mythological

Myth is a folklore genre consisting of narratives that play a fundamental role in a society, such as foundational tales or origin myths. Since "myth" is widely used to imply that a story is not objectively true, the identification of a narrat ...

plafond

A plafond (French for "ceiling"), in a broad sense, is a (flat, vaulted or dome) ceiling.

A plafond can be a product of monumental painting or sculpture. Picturesque plafonds can be painted directly on plaster (as a fresco, oil, glutinous, s ...

s. By taking the example of Queen Marie Casimire, that ordered to paint her as a goddess in palace plafonds, the hetmaness decorated the Lower Vestibule with a fresco depicting her as a Roman goddess

Roman mythology is the body of myths of ancient Rome as represented in the literature and visual arts of the Romans. One of a wide variety of genres of Roman folklore, ''Roman mythology'' may also refer to the modern study of these representat ...

of fertility

Fertility is the capability to produce offspring through reproduction following the onset of sexual maturity. The fertility rate is the average number of children born by a female during her lifetime and is quantified demographically. Fertili ...

‚Äď Flora

Flora is all the plant life present in a particular region or time, generally the naturally occurring (indigenous) native plants. Sometimes bacteria and fungi are also referred to as flora, as in the terms '' gut flora'' or '' skin flora''.

E ...

(she was almost 60 at that time).

In 1729, she erected the mausoleum

A mausoleum is an external free-standing building constructed as a monument enclosing the interment space or burial chamber of a deceased person or people. A mausoleum without the person's remains is called a cenotaph. A mausoleum may be consid ...

in Berezhany to commemorate her husband, the last male line descendant of the Sieniawski family, but she did not complete the interior. ElŇľbieta Sieniawska died the same year in Oleszyce.

Ancestors

See also

*Marina Mniszech

Marina Mniszech, ( pl, Maryna Mniszech; russian: –ú–į—Ä–ł–Ĺ–į –ú–Ĺ–ł—ą–Ķ–ļ, Marina Mnishek, ) also known in Russian lore as Marinka the Witch ( 1588 ‚Äď 24 December 1614) was a Polish noblewoman

Nobility is a social class found in many so ...

*Urszula Mayerin

Urszula Meyerin (also, ''Meierin''; 1570‚Äď1635) was a politically influential Polish courtier and mistress to King Sigismund III of Poland. Her real surname may have been ''Gienger'' (or ''Gienger von Gr√ľnb√ľchl''), but that remains in dispute; ...

*Izabela Czartoryska

ElŇľbieta "Izabela" Dorota Czartoryska (''n√©e'' Flemming; 3 March 1746 – 15 July 1835) was a Polish princess, writer, art collector, and prominent figure in the Polish Enlightenment. She was the wife of Adam Kazimierz Czartoryski and a m ...

References

Notes

Bibliography

# . # . # . # . # . # . # . # . # . # . # . # . # . # . # . # . # . # . # . # . # . # . # . # . # . # . # .External links

* Agnieszka SŇāabyRzńÖdzicha oleszycka. Dw√≥r ElŇľbiety z Lubomirskich Sieniawskiej jako przykŇāad patronatu kobiecego w czasach saskich

Kraków 2014.

Lubomirski family

The Learned Ladies

{{DEFAULTSORT:Sieniawska, Elzbieta 1669 births 1729 deaths Elzbieta Lubomirski family Polish women in politics Mistresses of Polish royalty Mistresses of Hungarian royalty Polish people of the Great Northern War Polish landscape and garden designers 17th-century Polish women 18th-century Polish women Polish ladies-in-waiting 18th-century philanthropists Polish philanthropists