Einstein–Szilard letter on:

[Wikipedia]

[Google]

[Amazon]

The Einstein–Szilard letter was a letter written by

The Einstein–Szilard letter was a letter written by

The Einstein–Szilard letter was signed by Einstein and posted back to Szilard, who received it on August 9. Szilard gave both the short and long letters, along with a letter of his own, to Sachs on August 15. Sachs asked the

The Einstein–Szilard letter was signed by Einstein and posted back to Szilard, who received it on August 9. Szilard gave both the short and long letters, along with a letter of his own, to Sachs on August 15. Sachs asked the

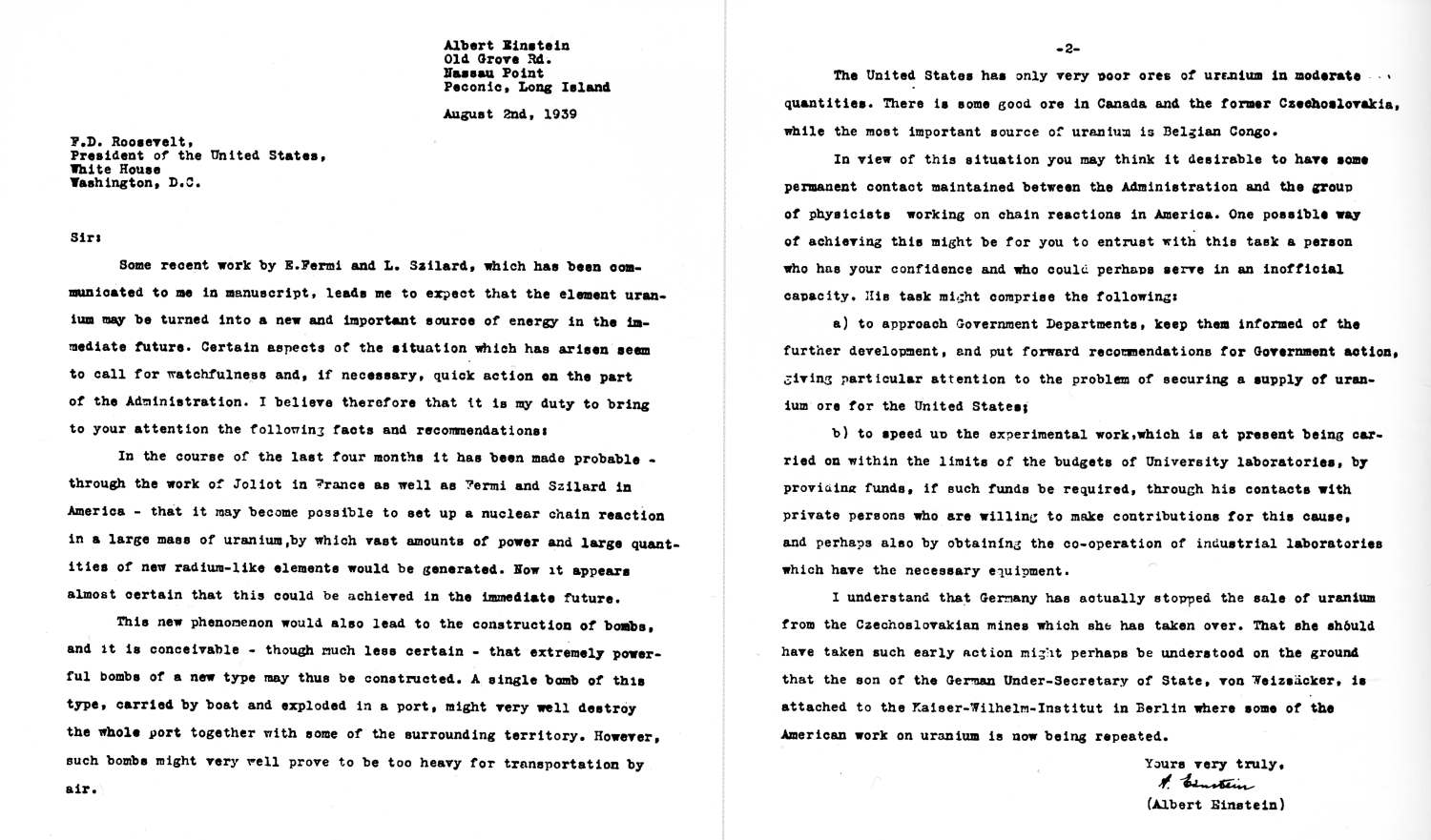

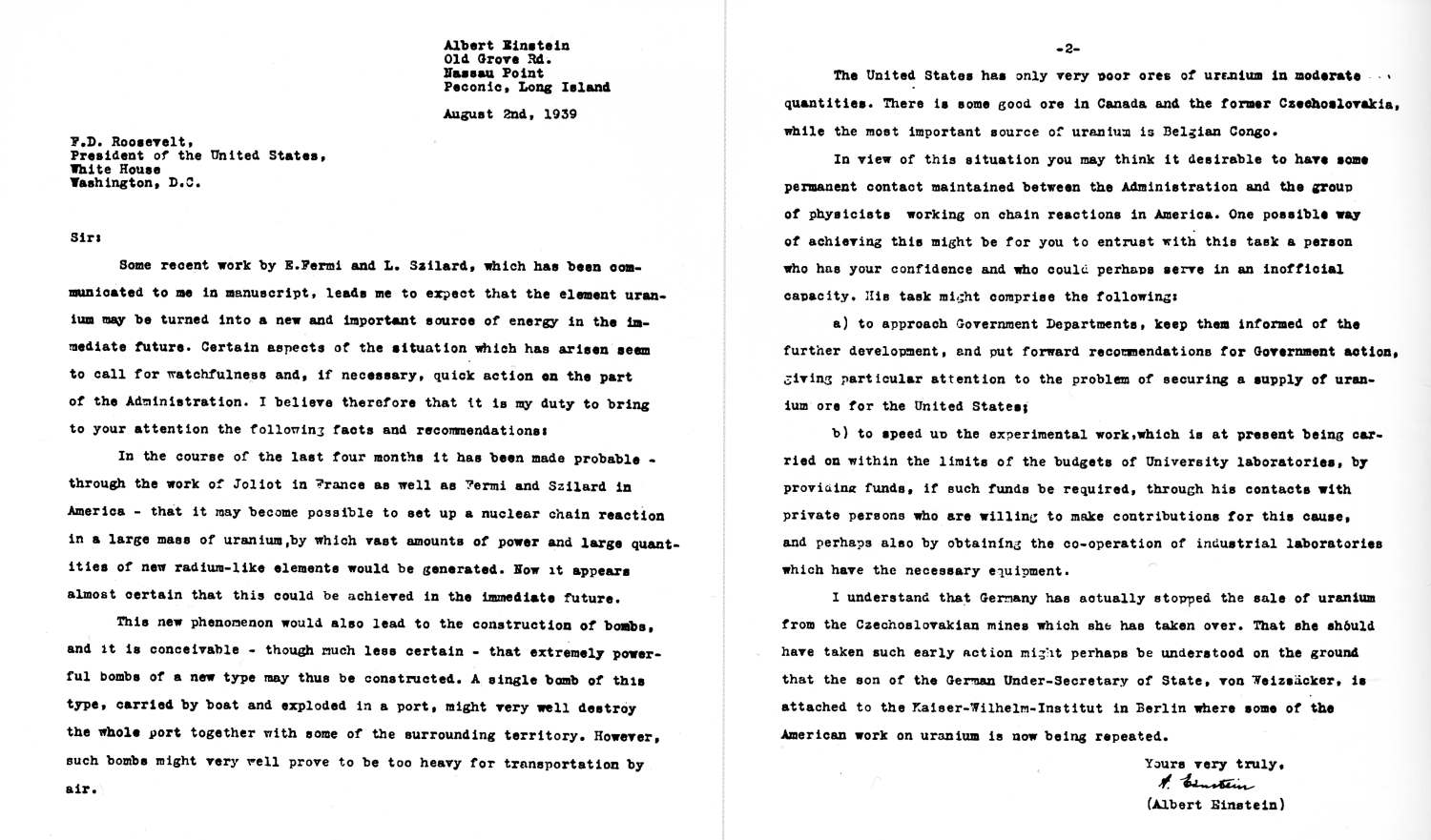

Reproduction of 1939 Einstein–Szilárd letter

FDR library, Marist University

Einstein and Szilard re-enact their meeting

for the film '' Atomic Power'' (1946) {{DEFAULTSORT:Einstein-Szilard letter Albert Einstein History of the Manhattan Project 1939 documents World War II documents Letters (message)

The Einstein–Szilard letter was a letter written by

The Einstein–Szilard letter was a letter written by Leo Szilard

Leo Szilard (; hu, Szilárd Leó, pronounced ; born Leó Spitz; February 11, 1898 – May 30, 1964) was a Hungarian-German-American physicist and inventor. He conceived the nuclear chain reaction in 1933, patented the idea of a nuclear ...

and signed by Albert Einstein

Albert Einstein ( ; ; 14 March 1879 – 18 April 1955) was a German-born theoretical physicist, widely acknowledged to be one of the greatest and most influential physicists of all time. Einstein is best known for developing the theor ...

on August 2, 1939, that was sent to President of the United States

The president of the United States (POTUS) is the head of state and head of government of the United States of America. The president directs the Federal government of the United States#Executive branch, executive branch of the Federal gove ...

Franklin D. Roosevelt

Franklin Delano Roosevelt (; ; January 30, 1882April 12, 1945), often referred to by his initials FDR, was an American politician and attorney who served as the 32nd president of the United States from 1933 until his death in 1945. As the ...

. Written by Szilard in consultation with fellow Hungarian physicists Edward Teller

Edward Teller ( hu, Teller Ede; January 15, 1908 – September 9, 2003) was a Hungarian-American theoretical physicist who is known colloquially as "the father of the hydrogen bomb" (see the Teller–Ulam design), although he did not care for ...

and Eugene Wigner

Eugene Paul "E. P." Wigner ( hu, Wigner Jenő Pál, ; November 17, 1902 – January 1, 1995) was a Hungarian-American theoretical physicist who also contributed to mathematical physics. He received the Nobel Prize in Physics in 1963 "for his co ...

, the letter warned that Germany might develop atomic bomb

A nuclear weapon is an explosive device that derives its destructive force from nuclear reactions, either fission (fission bomb) or a combination of fission and fusion reactions ( thermonuclear bomb), producing a nuclear explosion. Both bomb ...

s and suggested that the United States should start its own nuclear program. It prompted action by Roosevelt, which eventually resulted in the Manhattan Project

The Manhattan Project was a research and development undertaking during World War II that produced the first nuclear weapons. It was led by the United States with the support of the United Kingdom and Canada. From 1942 to 1946, the project w ...

, the development of the first atomic bombs, and the use of these bombs on the cities of Hiroshima and Nagasaki.

Origin

Otto Hahn

Otto Hahn (; 8 March 1879 – 28 July 1968) was a German chemist who was a pioneer in the fields of radioactivity and radiochemistry. He is referred to as the father of nuclear chemistry and father of nuclear fission. Hahn and Lise Meitner ...

and Fritz Strassmann

Friedrich Wilhelm Strassmann (; 22 February 1902 – 22 April 1980) was a German chemist who, with Otto Hahn in December 1938, identified the element barium as a product of the bombardment of uranium with neutrons. Their observation was the ke ...

reported the discovery of nuclear fission

Nuclear fission was discovered in December 1938 by chemists Otto Hahn and Fritz Strassmann and physicists Lise Meitner and Otto Robert Frisch. Fission is a nuclear reaction or radioactive decay process in which the nucleus of an atom splits ...

in uranium in the January 6, 1939, issue of ''Die Naturwissenschaften

''The Science of Nature'', formerly ''Naturwissenschaften'', is a monthly peer-reviewed scientific journal published by Springer Science+Business Media covering all aspects of the natural sciences relating to questions of biological significance. I ...

'', and Lise Meitner

Elise Meitner ( , ; 7 November 1878 – 27 October 1968) was an Austrian-Swedish physicist who was one of those responsible for the discovery of the element protactinium and nuclear fission. While working at the Kaiser Wilhelm Institute on r ...

identified it as nuclear fission

Nuclear fission is a reaction in which the nucleus of an atom splits into two or more smaller nuclei. The fission process often produces gamma photons, and releases a very large amount of energy even by the energetic standards of radio ...

in the February 11, 1939, issue of ''Nature

Nature, in the broadest sense, is the physical world or universe. "Nature" can refer to the phenomena of the physical world, and also to life in general. The study of nature is a large, if not the only, part of science. Although humans are ...

''. This generated intense interest among physicists. Danish physicist Niels Bohr

Niels Henrik David Bohr (; 7 October 1885 – 18 November 1962) was a Danish physicist who made foundational contributions to understanding atomic structure and quantum theory, for which he received the Nobel Prize in Physics in 1922 ...

brought the news to the United States, and the U.S. opened the Fifth Washington Conference on Theoretical Physics with Enrico Fermi

Enrico Fermi (; 29 September 1901 – 28 November 1954) was an Italian (later naturalized American) physicist and the creator of the world's first nuclear reactor, the Chicago Pile-1. He has been called the "architect of the nuclear age" an ...

on January 26, 1939. The results were quickly corroborated by experimental physicists, most notably Fermi and John R. Dunning

John Ray Dunning (September 24, 1907 – August 25, 1975) was an American physicist who played key roles in the Manhattan Project that developed the first atomic bombs. He specialized in neutron physics, and did pioneering work in gaseous diffusio ...

at Columbia University

Columbia University (also known as Columbia, and officially as Columbia University in the City of New York) is a private research university in New York City. Established in 1754 as King's College on the grounds of Trinity Church in Manhatt ...

.

Hungarian physicist Leo Szilard

Leo Szilard (; hu, Szilárd Leó, pronounced ; born Leó Spitz; February 11, 1898 – May 30, 1964) was a Hungarian-German-American physicist and inventor. He conceived the nuclear chain reaction in 1933, patented the idea of a nuclear ...

realized that the neutron

The neutron is a subatomic particle, symbol or , which has a neutral (not positive or negative) charge, and a mass slightly greater than that of a proton. Protons and neutrons constitute the atomic nucleus, nuclei of atoms. Since protons and ...

-driven fission of heavy atoms could be used to create a nuclear chain reaction

In nuclear physics, a nuclear chain reaction occurs when one single nuclear reaction causes an average of one or more subsequent nuclear reactions, thus leading to the possibility of a self-propagating series of these reactions. The specific nu ...

which could yield vast amounts of energy for electric power generation or atomic bombs. He had first formulated and patented such an idea while he lived in London in 1933 after reading Ernest Rutherford

Ernest Rutherford, 1st Baron Rutherford of Nelson, (30 August 1871 – 19 October 1937) was a New Zealand physicist who came to be known as the father of nuclear physics.

''Encyclopædia Britannica'' considers him to be the greatest ...

's disparaging remarks about generating power from his team's 1932 experiment using proton

A proton is a stable subatomic particle, symbol , H+, or 1H+ with a positive electric charge of +1 ''e'' elementary charge. Its mass is slightly less than that of a neutron and 1,836 times the mass of an electron (the proton–electron mass ...

s to split lithium

Lithium (from el, λίθος, lithos, lit=stone) is a chemical element with the symbol Li and atomic number 3. It is a soft, silvery-white alkali metal. Under standard conditions, it is the least dense metal and the least dense soli ...

. However, Szilard had not been able to achieve a neutron-driven chain reaction with neutron-rich light atoms. In theory, if the number of secondary neutrons produced in a neutron-driven chain reaction was greater than one, then each such reaction could trigger multiple additional reactions, producing an exponentially increasing number of reactions.

Szilard teamed up with Fermi to build a nuclear reactor from natural uranium at Columbia University, where George B. Pegram

George Braxton Pegram (October 24, 1876 – August 12, 1958) was an American physicist who played a key role in the technical administration of the Manhattan Project. He graduated from Trinity College (now Duke University) in 1895, and taught hig ...

headed the physics department. There was disagreement about whether fission was produced by uranium-235

Uranium-235 (235U or U-235) is an isotope of uranium making up about 0.72% of natural uranium. Unlike the predominant isotope uranium-238, it is fissile, i.e., it can sustain a nuclear chain reaction. It is the only fissile isotope that exi ...

, which made up less than one percent of natural uranium, or the more abundant uranium-238

Uranium-238 (238U or U-238) is the most common isotope of uranium found in nature, with a relative abundance of 99%. Unlike uranium-235, it is non-fissile, which means it cannot sustain a chain reaction in a thermal-neutron reactor. However ...

isotope

Isotopes are two or more types of atoms that have the same atomic number (number of protons in their nuclei) and position in the periodic table (and hence belong to the same chemical element), and that differ in nucleon numbers ( mass num ...

, as Fermi maintained. Fermi and Szilard conducted a series of experiments and concluded that a chain reaction in natural uranium could be possible if they could find a suitable neutron moderator

In nuclear engineering, a neutron moderator is a medium that reduces the speed of fast neutrons, ideally without capturing any, leaving them as thermal neutrons with only minimal (thermal) kinetic energy. These thermal neutrons are immensely m ...

. They found that the hydrogen atoms in water slowed neutrons but tended to capture

Capture may refer to:

*Asteroid capture, a phenomenon in which an asteroid enters a stable orbit around another body

*Capture, a software for lighting design, documentation and visualisation

*"Capture" a song by Simon Townshend

*Capture (band), an ...

them. Szilard then suggested using carbon as a moderator. They then needed large quantities of carbon and uranium to create a reactor. Szilard was convinced that they would succeed if they could get the materials.

Szilard was concerned that German scientists might also attempt this experiment. German nuclear physicist Siegfried Flügge

Siegfried Flügge (16 March 1912, in Dresden – 15 December 1997, in Hinterzarten) was a German theoretical physicist who made contributions to nuclear physics and the theoretical basis for nuclear weapons. He worked on the German nuclear en ...

published two influential articles on the exploitation of nuclear energy in 1939. After discussing this prospect with fellow Hungarian physicist Eugene Wigner

Eugene Paul "E. P." Wigner ( hu, Wigner Jenő Pál, ; November 17, 1902 – January 1, 1995) was a Hungarian-American theoretical physicist who also contributed to mathematical physics. He received the Nobel Prize in Physics in 1963 "for his co ...

, they decided that they should warn the Belgians, as the Belgian Congo

The Belgian Congo (french: Congo belge, ; nl, Belgisch-Congo) was a Belgian colony in Central Africa from 1908 until independence in 1960. The former colony adopted its present name, the Democratic Republic of the Congo (DRC), in 1964.

Colo ...

was the best source of uranium ore. Wigner suggested that Albert Einstein

Albert Einstein ( ; ; 14 March 1879 – 18 April 1955) was a German-born theoretical physicist, widely acknowledged to be one of the greatest and most influential physicists of all time. Einstein is best known for developing the theor ...

might be a suitable person to do this, as he knew the Belgian Royal Family

Belgium is a constitutional, hereditary, and popular monarchy. The monarch is titled king or queen of the Belgians ( nl, Koning(in) der Belgen, french: Roi / Reine des Belges}, german: König(in) der Belgier) and serves as the country's he ...

. Szilard knew Einstein well; between 1926 and 1930, he had worked with Einstein to develop the Einstein refrigerator

The Einstein–Szilard or Einstein refrigerator is an absorption refrigerator which has no moving parts, operates at constant pressure, and requires only a heat source to operate. It was jointly invented in 1926 by Albert Einstein and his form ...

.

The letter

On July 12, 1939, Szilard and Wigner drove in Wigner's car to Cutchogue on New York'sLong Island

Long Island is a densely populated island in the southeastern region of the U.S. state of New York, part of the New York metropolitan area. With over 8 million people, Long Island is the most populous island in the United States and the 18 ...

, where Einstein was staying. When they explained about the possibility of atomic bombs, Einstein replied: ''"Daran habe ich gar nicht gedacht"'' ("I did not even think about that"). Szilard dictated a letter in German to the Belgian Ambassador to the United States. Wigner wrote it down, and Einstein signed it. At Wigner's suggestion, they also prepared a letter for the State Department

The United States Department of State (DOS), or State Department, is an executive department of the U.S. federal government responsible for the country's foreign policy and relations. Equivalent to the ministry of foreign affairs of other na ...

explaining what they were doing and why, giving it two weeks to respond if it had any objections.

This still left the problem of getting government support for uranium research. Another friend of Szilard's, the Austrian economist Gustav Stolper, suggested approaching Alexander Sachs

Alexander Sachs (August 1, 1893 – June 23, 1973) was an American economist and banker. In October 1939 he delivered the Einstein–Szilárd letter to President Franklin D. Roosevelt, suggesting that nuclear-fission research ought to be pursue ...

, who had access to President

President most commonly refers to:

*President (corporate title)

* President (education), a leader of a college or university

* President (government title)

President may also refer to:

Automobiles

* Nissan President, a 1966–2010 Japanese ...

Franklin D. Roosevelt

Franklin Delano Roosevelt (; ; January 30, 1882April 12, 1945), often referred to by his initials FDR, was an American politician and attorney who served as the 32nd president of the United States from 1933 until his death in 1945. As the ...

. Sachs told Szilard that he had already spoken to the President about uranium, but that Fermi and Pegram had reported that the prospects for building an atomic bomb were remote. He told Szilard that he would deliver the letter, but suggested that it come from someone more prestigious. For Szilard, Einstein was again the obvious choice. Sachs and Szilard drafted a letter riddled with spelling errors and mailed it to Einstein.

Szilard also set out himself for Long Island again on August 2. Wigner was unavailable, so this time Szilard co-opted another Hungarian physicist, Edward Teller

Edward Teller ( hu, Teller Ede; January 15, 1908 – September 9, 2003) was a Hungarian-American theoretical physicist who is known colloquially as "the father of the hydrogen bomb" (see the Teller–Ulam design), although he did not care for ...

, to do the driving. After receiving the draft, Einstein dictated the letter first in German. On returning to Columbia University, Szilard dictated the letter in English to a young departmental stenographer, Janet Coatesworth. She later recalled that when Szilard mentioned extremely powerful bombs, she "was sure she was working for a nut". Ending the letter with "Yours truly, Albert Einstein" did nothing to alter this impression. Both the English letter and a longer explanatory letter were then posted to Einstein for him to sign.

The letter dated August 2 and addressed to President Roosevelt warned that:

It also specifically warned about Germany:

At the time of the letter, the estimated material necessary for a fission chain reaction was several tons. Seven months later a breakthrough in Britain would estimate the necessary critical mass

In nuclear engineering, a critical mass is the smallest amount of fissile material needed for a sustained nuclear chain reaction. The critical mass of a fissionable material depends upon its nuclear properties (specifically, its nuclear fi ...

to be less than 10 kilograms, making delivery of a bomb by air a possibility.

Delivery

The Einstein–Szilard letter was signed by Einstein and posted back to Szilard, who received it on August 9. Szilard gave both the short and long letters, along with a letter of his own, to Sachs on August 15. Sachs asked the

The Einstein–Szilard letter was signed by Einstein and posted back to Szilard, who received it on August 9. Szilard gave both the short and long letters, along with a letter of his own, to Sachs on August 15. Sachs asked the White House

The White House is the official residence and workplace of the president of the United States. It is located at 1600 Pennsylvania Avenue NW in Washington, D.C., and has been the residence of every U.S. president since John Adams in ...

staff for an appointment to see President Roosevelt, but before one could be set up, the administration became embroiled in a crisis due to Germany

Germany,, officially the Federal Republic of Germany, is a country in Central Europe. It is the second most populous country in Europe after Russia, and the most populous member state of the European Union. Germany is situated betwee ...

's invasion of Poland

The invasion of Poland (1 September – 6 October 1939) was a joint attack on the Republic of Poland by Nazi Germany and the Soviet Union which marked the beginning of World War II. The German invasion began on 1 September 1939, one week af ...

, which started World War II

World War II or the Second World War, often abbreviated as WWII or WW2, was a world war that lasted from 1939 to 1945. It involved the World War II by country, vast majority of the world's countries—including all of the great power ...

. Sachs delayed his appointment until October so that the President would give the letter due attention, securing an appointment on October 11. On that date he met with the President, the President's secretary, Brigadier General

Brigadier general or Brigade general is a military rank used in many countries. It is the lowest ranking general officer in some countries. The rank is usually above a colonel, and below a major general or divisional general. When appointe ...

Edwin "Pa" Watson, and two ordnance experts, Army Lieutenant Colonel

Lieutenant colonel ( , ) is a rank of commissioned officers in the armies, most marine forces and some air forces of the world, above a major and below a colonel. Several police forces in the United States use the rank of lieutenant colon ...

Keith F. Adamson and Navy Commander

Commander (commonly abbreviated as Cmdr.) is a common naval officer rank. Commander is also used as a rank or title in other formal organizations, including several police forces. In several countries this naval rank is termed frigate captain. ...

Gilbert C. Hoover. Roosevelt summed up the conversation as: "Alex, what you are after is to see that the Nazis don't blow us up."

Roosevelt sent a reply thanking Einstein, and informing him that:

Einstein sent two more letters to Roosevelt, on March 7, 1940, and April 25, 1940, calling for action on nuclear research

Nuclear physics is the field of physics that studies atomic nuclei and their constituents and interactions, in addition to the study of other forms of nuclear matter.

Nuclear physics should not be confused with atomic physics, which studies the ...

. Szilard drafted a fourth letter for Einstein's signature that urged the President to meet with Szilard to discuss policy on nuclear energy. Dated March 25, 1945, it did not reach Roosevelt before his death on April 12, 1945.

Results

Roosevelt decided that the letter required action, and authorized the creation of theAdvisory Committee on Uranium

The S-1 Executive Committee laid the groundwork for the Manhattan Project by initiating and coordinating the early research efforts in the United States, and liaising with the Tube Alloys Project in Britain.

In the wake of the discovery of nucle ...

. The committee was chaired by Lyman James Briggs, the Director of the Bureau of Standards (currently the National Institute of Standards and Technology

The National Institute of Standards and Technology (NIST) is an agency of the United States Department of Commerce whose mission is to promote American innovation and industrial competitiveness. NIST's activities are organized into physical s ...

), with Adamson and Hoover as its other members. It convened for the first time on October 21. The meeting was also attended by Fred L. Mohler from the Bureau of Standards, Richard B. Roberts of the Carnegie Institution of Washington

The Carnegie Institution of Washington (the organization's legal name), known also for public purposes as the Carnegie Institution for Science (CIS), is an organization in the United States established to fund and perform scientific research. Th ...

, and Szilard, Teller and Wigner. Adamson was skeptical about the prospect of building an atomic bomb, but was willing to authorize $6,000 ($100,000 in current USD) for the purchase of uranium

Uranium is a chemical element with the symbol U and atomic number 92. It is a silvery-grey metal in the actinide series of the periodic table. A uranium atom has 92 protons and 92 electrons, of which 6 are valence electrons. Uranium is weak ...

and graphite

Graphite () is a crystalline form of the element carbon. It consists of stacked layers of graphene. Graphite occurs naturally and is the most stable form of carbon under standard conditions. Synthetic and natural graphite are consumed on la ...

for Szilard and Fermi's experiment.

The Advisory Committee on Uranium was the beginning of the US government's effort to develop an atomic bomb, but it did not vigorously pursue the development of a weapon. It was superseded by the National Defense Research Committee

The National Defense Research Committee (NDRC) was an organization created "to coordinate, supervise, and conduct scientific research on the problems underlying the development, production, and use of mechanisms and devices of warfare" in the Un ...

in 1940, and then the Office of Scientific Research and Development

The Office of Scientific Research and Development (OSRD) was an agency of the United States federal government created to coordinate scientific research for military purposes during World War II. Arrangements were made for its creation during May 1 ...

in 1941. The Frisch–Peierls memorandum

The Frisch–Peierls memorandum was the first technical exposition of a practical nuclear weapon. It was written by expatriate German-Jewish physicists Otto Frisch and Rudolf Peierls in March 1940 while they were both working for Mark Oliphant a ...

and the British Maud Reports eventually prompted Roosevelt to authorize a full-scale development effort in January 1942. The work of fission research was taken over by the United States Army Corps of Engineers

, colors =

, anniversaries = 16 June (Organization Day)

, battles =

, battles_label = Wars

, website =

, commander1 = ...

's Manhattan District in June 1942, which directed an all-out bomb development program known as the Manhattan Project

The Manhattan Project was a research and development undertaking during World War II that produced the first nuclear weapons. It was led by the United States with the support of the United Kingdom and Canada. From 1942 to 1946, the project w ...

.

Einstein did not work on the Manhattan Project. The Army and Vannevar Bush

Vannevar Bush ( ; March 11, 1890 – June 28, 1974) was an American engineer, inventor and science administrator, who during World War II headed the U.S. Office of Scientific Research and Development (OSRD), through which almost all warti ...

denied him the work clearance needed in July 1940, saying his pacifist

Pacifism is the opposition or resistance to war, militarism (including conscription and mandatory military service) or violence. Pacifists generally reject theories of Just War. The word ''pacifism'' was coined by the French peace campai ...

leanings and celebrity status made him a security risk. At least one source states that Einstein did clandestinely contribute some equations to the Manhattan Project. Einstein was allowed to work as a consultant to the United States Navy

The United States Navy (USN) is the maritime service branch of the United States Armed Forces and one of the eight uniformed services of the United States. It is the largest and most powerful navy in the world, with the estimated tonnage ...

's Bureau of Ordnance The Bureau of Ordnance (BuOrd) was a United States Navy organization, which was responsible for the procurement, storage, and deployment of all naval weapons, between the years 1862 and 1959.

History

Congress established the Bureau in the Departme ...

. He had no knowledge of the atomic bomb's development, and no influence on the decision of any being used. According to Linus Pauling

Linus Carl Pauling (; February 28, 1901August 19, 1994) was an American chemist, biochemist, chemical engineer, peace activist, author, and educator. He published more than 1,200 papers and books, of which about 850 dealt with scientific topi ...

, Einstein later regretted signing the letter because it led to the development and use of the atomic bomb in combat, adding that Einstein had justified his decision because of the greater danger that Nazi Germany would develop the bomb first. In 1947 Einstein told ''Newsweek

''Newsweek'' is an American weekly online news magazine co-owned 50 percent each by Dev Pragad, its president and CEO, and Johnathan Davis (businessman), Johnathan Davis, who has no operational role at ''Newsweek''. Founded as a weekly print m ...

'' magazine that "had I known that the Germans would not succeed in developing an atomic bomb, I would have done nothing."

See also

* Alexander Sachs' role in bringing President Roosevelt's attention to the possibility of an atomic bomb *Frisch–Peierls memorandum

The Frisch–Peierls memorandum was the first technical exposition of a practical nuclear weapon. It was written by expatriate German-Jewish physicists Otto Frisch and Rudolf Peierls in March 1940 while they were both working for Mark Oliphant a ...

* List of most expensive books and manuscripts

* Nuclear weapons and the United States

The United States was the first country to manufacture nuclear weapons and is the only country to have used them in combat, with the bombings of Hiroshima and Nagasaki in World War II. Before and during the Cold War, it conducted 1,054 nucle ...

* Szilard petition

Notes

References

* * *Further reading

*External links

Reproduction of 1939 Einstein–Szilárd letter

FDR library, Marist University

Einstein and Szilard re-enact their meeting

for the film '' Atomic Power'' (1946) {{DEFAULTSORT:Einstein-Szilard letter Albert Einstein History of the Manhattan Project 1939 documents World War II documents Letters (message)