Edwards Pierrepont on:

[Wikipedia]

[Google]

[Amazon]

Edwards Pierrepont (March 4, 1817 – March 6, 1892) was an American attorney, reformer, jurist, traveler, New York U.S. Attorney, U.S. Attorney General, U.S. Minister to England, and orator.''West's Encyclopedia of American Law'' (2005), "Pierrepont, Edwards" p. 445, vol. 2 Having graduated from Yale in 1837, Pierrepont studied law and was admitted to the bar in 1840. During the

Oil portrait, Pierpont Limner, ''1711'' Edwards Pierrepont was born in

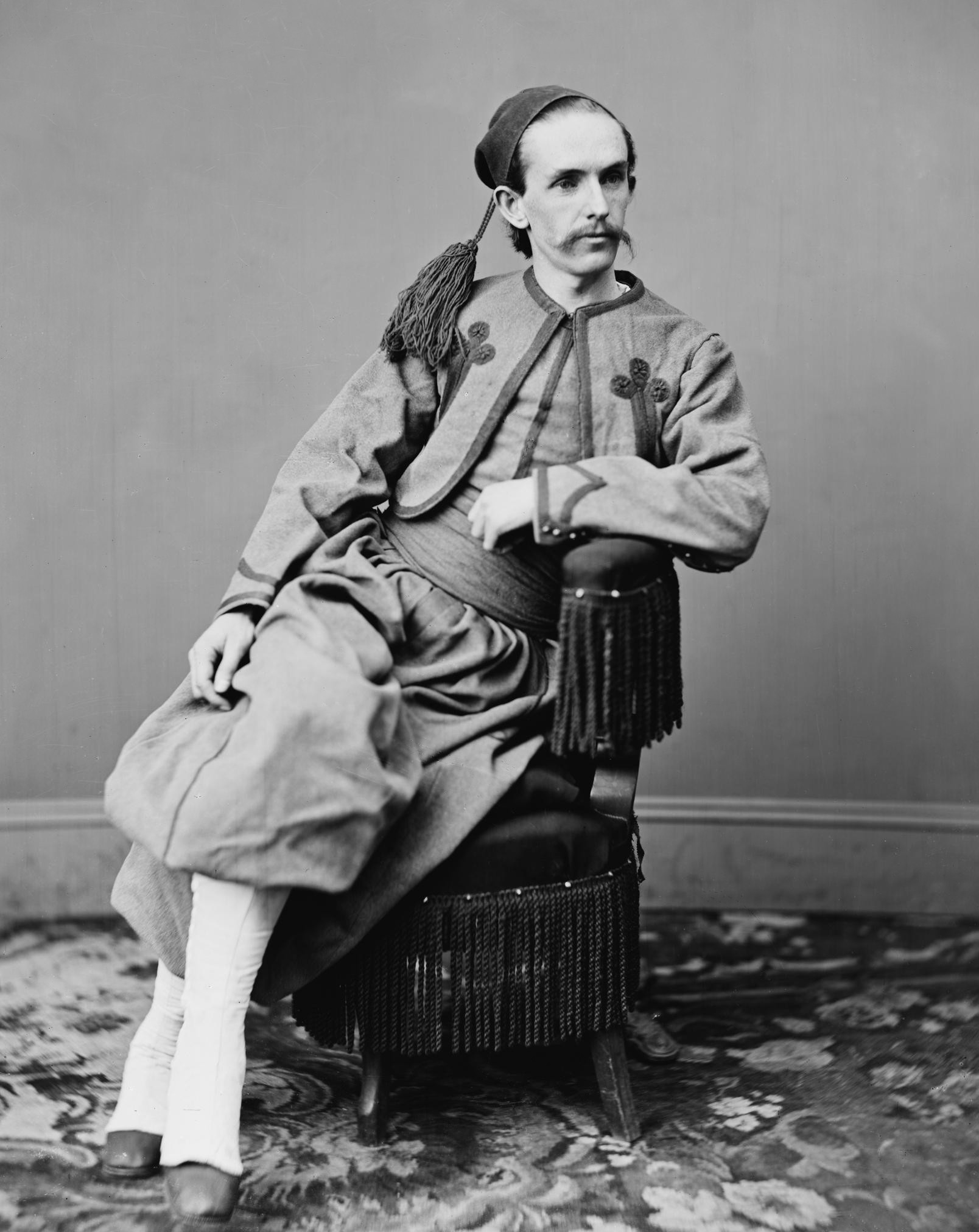

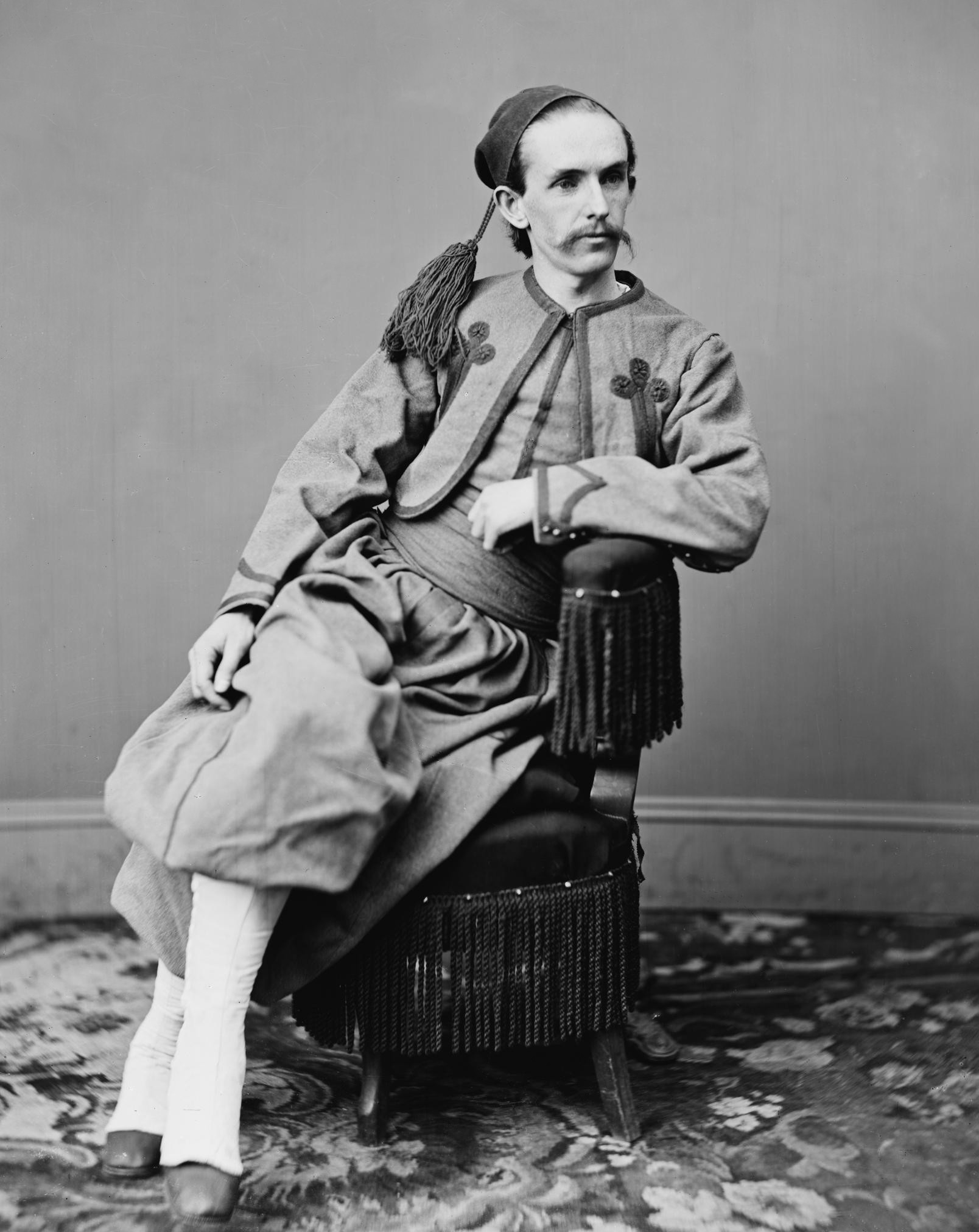

In 1867 Pierrepont conducted the case for the government against John H. Surratt, indicted as an accomplice in the murder of President Lincoln. Surratt, a former Confederate spy, was the last person to be tried by a U.S. Military commission in the case of Lincoln's assassination. After Lincoln's assassination, Surratt fled the United States to

In 1867 Pierrepont conducted the case for the government against John H. Surratt, indicted as an accomplice in the murder of President Lincoln. Surratt, a former Confederate spy, was the last person to be tried by a U.S. Military commission in the case of Lincoln's assassination. After Lincoln's assassination, Surratt fled the United States to

After the

After the

—Mathew Brady 1869 On September 25, 1872 reformer Pierrepont gave a speech at the

Hurst-Pierrepont Estate ''Aerial View''

from Bing Maps

Miniature Model of Hurst-Pierrepont Estate Mansion

from New York Botanical Gardens

Guide to the Edwards Pierrepont papers

from New York Public Library

Marble sculptures of Judge Edwards Pierrepont and Margaretta Willoughby Pierrepont

Marble sculptures of Judge Edwards Pierrepont and Margaretta Willoughby Pierrepont created by artist

{{DEFAULTSORT:Pierrepont, Edwards 1817 births 1892 deaths New York Supreme Court Justices United States Attorneys General People of New York (state) in the American Civil War Yale Law School alumni People from North Haven, Connecticut Politicians from New York City Ambassadors of the United States to the United Kingdom Grant administration cabinet members 19th-century American politicians 19th-century American diplomats New York (state) Democrats New York (state) Republicans Lawyers from New York City American anti-corruption activists

American Civil War

The American Civil War (April 12, 1861 – May 26, 1865; also known by other names) was a civil war in the United States. It was fought between the Union ("the North") and the Confederacy ("the South"), the latter formed by states ...

, Pierrepont was a Democrat, although he supported President Abraham Lincoln. Pierrepont initially supported President Andrew Johnson's conservative Reconstruction

Reconstruction may refer to:

Politics, history, and sociology

*Reconstruction (law), the transfer of a company's (or several companies') business to a new company

*'' Perestroika'' (Russian for "reconstruction"), a late 20th century Soviet Unio ...

efforts having opposed the Radical Republican

The Radical Republicans (later also known as "Stalwarts") were a faction within the Republican Party, originating from the party's founding in 1854, some 6 years before the Civil War, until the Compromise of 1877, which effectively ended Recon ...

s. In both 1868 and 1872, Pierrepont supported Ulysses S. Grant

Ulysses S. Grant (born Hiram Ulysses Grant ; April 27, 1822July 23, 1885) was an American military officer and politician who served as the 18th president of the United States from 1869 to 1877. As Commanding General, he led the Union Ar ...

for president. For his support, President Grant appointed Pierrepont United States Attorney in 1869. In 1871, Pierrepont gained the reputation as a solid reformer, having joined New York's ''Committee of Seventy'' that shut down Boss Tweed's corrupt Tammany Hall. In 1872, Pierrepont modified his views on Reconstruction and stated that African American

African Americans (also referred to as Black Americans and Afro-Americans) are an ethnic group consisting of Americans with partial or total ancestry from sub-Saharan Africa. The term "African American" generally denotes descendants of ens ...

freedman's rights needed to be protected.Pierrepont (September 25, 1872), Speech of the Hon. Edwards Pierrepont, pg. 23

In April 1875, Pierrepont was appointed U.S. Attorney General by President Grant, who, having teamed up with Secretary of Treasury Benjamin Bristow

Benjamin Helm Bristow (June 20, 1832 – June 22, 1896) was an American lawyer and politician who served as the 30th U.S. Treasury Secretary and the first Solicitor General.

A Union military officer, Bristow was a Republican Party reformer and ...

, vigorously prosecuted the notorious Whiskey Ring

The Whiskey Ring took place from 1871 to 1876 centering in St. Louis during the Presidency of Ulysses S. Grant. The ring was an American scandal, broken in May 1875, involving the diversion of tax revenues in a conspiracy among government agents, ...

, a national tax evasion swindle that involved whiskey distillers, brokers, and government officials, including President Grant's private secretary, Orville E. Babcock

Orville Elias Babcock (December 25, 1835 – June 2, 1884) was an American engineer and general in the Union Army during the Civil War. An aide to General Ulysses S. Grant during and after the war, he was President Grant's military private secret ...

. Upon his appointment, Pierrepont quickly cleaned up corruption in Southern U.S. districts. Pierrepont had continued former Attorney General George H. Williams moratorium on prosecuting the Ku Klux Klan. The Klan had been previously prosecuted by President Grant's Attorneys General Amos T. Akerman and Williams from 1871 to 1873, prosecuting civil rights violations of whites against African Americans. Pierrepont ruled that a naturalized Prussian immigrant's son born in the U.S. was not obligated to serve in the Prussian military as an adult. In his ruling of the Chorpenning Claim, Pierrepont cited the Supreme Court case ''Gorden v United States'', having agreed that the Postmaster General, as well as the Secretary of War, served as ministers rather than legally binding arbitrators for a monetary claim by a private citizen. After serving as Attorney General, Pierrepont was appointed Minister to Great Britain by President Grant serving from 1876 to 1877. After many visits to France, Pierrepont became an advocate for bimetalism

Bimetallism, also known as the bimetallic standard, is a monetary standard in which the value of the monetary unit is defined as equivalent to certain quantities of two metals, typically gold and silver, creating a fixed rate of exchange betwee ...

. Having returned from England, Pierrepont resumed his law practice until his death in 1892.

Early life and ancestry

thumb , 180px , right , James PierepontOil portrait, Pierpont Limner, ''1711'' Edwards Pierrepont was born in

North Haven, Connecticut

North Haven is a town in New Haven County, Connecticut on the outskirts of New Haven, Connecticut. As of the 2020 census, it had a population of 24,253.

North Haven is home of the Quinnipiac University School of Health Sciences, the School of Nur ...

, on March 4, 1817. He was the son of Giles Pierepont and Eunice Munson Pierepont. Giles Pierepont was a New England descendant of James Pierepont, a cofounder of Yale University

Yale University is a Private university, private research university in New Haven, Connecticut. Established in 1701 as the Collegiate School, it is the List of Colonial Colleges, third-oldest institution of higher education in the United Sta ...

. Pierrepont's baptised name was Munson Edwards Pierepont, however, he changed his name to Edwards Pierrepont, dropping Munson and adding an extra "r" to his last name. Pierrepont was an earlier version of his family name.

Pierrepont attend several schools in the North Haven area, enrolled at Yale University

Yale University is a Private university, private research university in New Haven, Connecticut. Established in 1701 as the Collegiate School, it is the List of Colonial Colleges, third-oldest institution of higher education in the United Sta ...

, and graduated in 1837. After graduation, Edwards traveled and explored the West, then studied at New Haven Law School. He passed the bar in 1840, and tutored at Yale University from 1840 to 1841. He then moved to Columbus, Ohio where he practiced law with Phineas B. Wilcox from 1840 to 1845. In 1846, Pierrepont moved to New York where he established his own practice.

Marriages, family, and estates

On May 27, 1846, Pierrepont married Margaretta Willoughby, fromBrooklyn

Brooklyn () is a borough of New York City, coextensive with Kings County, in the U.S. state of New York. Kings County is the most populous county in the State of New York, and the second-most densely populated county in the United States, be ...

, the daughter of Samuel Willoughby. Their marriage produced two children, one son, Edwin, and one daughter, Margaretta. Edwin died in Rome in 1885 while serving as Chargé d'Affaires, having replaced Mr. William Astor, the U.S. Envoy, who had retired. Pierrepont's daughter married Leanord F. Beckwith who lived at 48 West Seventy-second Street in New York.

In 1852, Pierrepont completed the construction of his estate house at 103 Fifth Avenue in New York. This would be his permanent residence for the next 40 years. In 1867, Pierrepont built a country estate house in Garrison, designed by architect Alexander Jackson Davis

Alexander Jackson Davis, or A. J. Davis (July 24, 1803 – January 14, 1892), was an American architect, known particularly for his association with the Gothic Revival style.

Education

Davis was born in New York City and studied at ...

; it was listed on the National Register of Historic Places

The National Register of Historic Places (NRHP) is the United States federal government's official list of districts, sites, buildings, structures and objects deemed worthy of preservation for their historical significance or "great artistic ...

in 1982 as the Hurst-Pierrepont Estate

Hurst-Pierrepont Estate is a historic estate (land), estate located at Garrison, New York, Garrison in Putnam County, New York. It was designed by architect Alexander Jackson Davis (1803-1892) for Edwards Pierrepont (1817-1892) and built in 1867 ...

.

Political career

Upon moving to New York, Pierrepont became active in politics, having joined theDemocratic Party Democratic Party most often refers to:

*Democratic Party (United States)

Democratic Party and similar terms may also refer to:

Active parties Africa

*Botswana Democratic Party

*Democratic Party of Equatorial Guinea

*Gabonese Democratic Party

*Demo ...

in 1846. Pierrepont first served in office when he was elected Superior Court Judge on the New York Supreme Court; he served from 1857 to 1860.

Civil War

Pierrepont was believed to have a pulse on the nation and served as Abraham Lincoln's personal advisor before and after Lincoln was elected president.''West's Encyclopedia of American Law'' (2005), "Pierrepont, Edwards" p. 446, vol. 2 In 1862, during theCivil War

A civil war or intrastate war is a war between organized groups within the same state (or country).

The aim of one side may be to take control of the country or a region, to achieve independence for a region, or to change government policies ...

Pierrepont was appointed by President Lincoln a member of the military commission to try the cases of state prisoners in the custody of the federal military authorities. During the Presidential election of 1864, Pierrepont supported Lincoln in a political speech at Cooper Union, believing President Lincoln would secure the restoration of the Union. Pierrepont stated Lincoln stood for freedom, liberty

Liberty is the ability to do as one pleases, or a right or immunity enjoyed by prescription or by grant (i.e. privilege). It is a synonym for the word freedom.

In modern politics, liberty is understood as the state of being free within society fr ...

and national glory.

Prosecuted Surratt trial

In 1867 Pierrepont conducted the case for the government against John H. Surratt, indicted as an accomplice in the murder of President Lincoln. Surratt, a former Confederate spy, was the last person to be tried by a U.S. Military commission in the case of Lincoln's assassination. After Lincoln's assassination, Surratt fled the United States to

In 1867 Pierrepont conducted the case for the government against John H. Surratt, indicted as an accomplice in the murder of President Lincoln. Surratt, a former Confederate spy, was the last person to be tried by a U.S. Military commission in the case of Lincoln's assassination. After Lincoln's assassination, Surratt fled the United States to Montreal

Montreal ( ; officially Montréal, ) is the second-most populous city in Canada and most populous city in the Canadian province of Quebec. Founded in 1642 as '' Ville-Marie'', or "City of Mary", it is named after Mount Royal, the triple ...

, Liverpool

Liverpool is a city and metropolitan borough in Merseyside, England. With a population of in 2019, it is the 10th largest English district by population and its metropolitan area is the fifth largest in the United Kingdom, with a populat ...

, Rome, and was finally caught in Egypt

Egypt ( ar, مصر , ), officially the Arab Republic of Egypt, is a transcontinental country spanning the northeast corner of Africa and southwest corner of Asia via a land bridge formed by the Sinai Peninsula. It is bordered by the Medit ...

on December 2, 1866, where he was indicted and returned to the United States to face U.S. military trial. The trial opened on June 10, 1867 under Judge George P. Fisher

George Purnell Fisher (October 13, 1817 – February 10, 1899) was Attorney General of Delaware, Secretary of State of Delaware, a United States representative from Delaware and an United States federal judge, Associate Justice of the Supreme Co ...

and held immense public interest in the United States. Pierrepont argued that Surratt was involved in the conspiracy to overthrow the U.S. Government and involved with the assassination of Abraham Lincoln by John Wilkes Booth

John Wilkes Booth (May 10, 1838 – April 26, 1865) was an American stage actor who assassinated United States President Abraham Lincoln at Ford's Theatre in Washington, D.C., on April 14, 1865. A member of the prominent 19th-century Booth ...

.Washington Government Printing Office (1867), ''Argument of Hon. Edwards Pierrepont to the jury: on the trial of John H. Surratt For the Murder of President Lincoln'', pp. 4–5 Pierrepont argued that the military trial was suited for Surratt's case and quoted Bible

The Bible (from Koine Greek , , 'the books') is a collection of religious texts or scriptures that are held to be sacred in Christianity, Judaism, Samaritanism, and many other religions. The Bible is an anthologya compilation of texts ...

verses that he viewed supported government was created by God for the express purpose of finding the guilty.Washington Government Printing Office (1867), ''Argument of Hon. Edwards Pierrepont to the jury: on the trial of John H. Surratt For the Murder of President Lincoln'', pp. 7–8 Pierrepont argued that because Surratt had assumed an alias name, John Harrison, in staying at a hotel, and had fled the country that this proved his guilt.Washington Government Printing Office (1867), ''Argument of Hon. Edwards Pierrepont to the jury: on the trial of John H. Surratt For the Murder of President Lincoln'', pp. 10–11 The trial lasted until August 10, 1867 and ended with the jury unable to make any decision after a seventy-hour deliberation. As a result of the hung jury, Judge Fisher set Surratt free.

New York constitutional convention member

In April 1867, Pierrepont was elected a member of the New York Constitutional Convention serving on the Judiciary Committee. A total of 19 committees were created to study each constitutional revision with Pierrepont's larger Judiciary Committee having a total of 15 members. The Constitutional Convention turned out to be a long drawn-out process of deliberation that lasted into June 1867 whose purpose was to root out any constitutional defects from the previous 1846 New York Constitution. One contentious issue was whether to allow women suffrage and to strike out the word "male" that defined New York voters.U.S. Attorney for the Southern District of New York

From April 25, 1869 to July 20, 1870 Pierrepont served asU.S. Attorney for the Southern District of New York

The United States Attorney for the Southern District of New York is the chief federal law enforcement officer in eight New York counties: New York (Manhattan), Bronx, Westchester, Putnam, Rockland, Orange, Dutchess and Sullivan. Establish ...

appointed by President Ulysses S. Grant. As U.S. Attorney, he prosecuted Cuban revolutionaries for violation of the Neutrality Act. On Tuesday June 15, 1869, U.S. Attorney Pierrepont arrested and indicted members of the ''Cuban Junta'', an organization to aid the Cuban Rebellion. Included in the arrests were the ''Cuban Junta'' President and other members; Jose Moralez Lemus, Wm. O.C. Ryan, Francisco Fesser, and Jose Mora. The ''Cuban Junta'' on May 1, 1869 had organized a military expedition to fight in the Cuban Rebellion against Spain. Other members of the ''Cuban Junta'' escaped arrest by the Deputy Marshall Allan. Pierrepont retired as U.S. Attorney and resumed his private law practice.

Committee of Seventy member

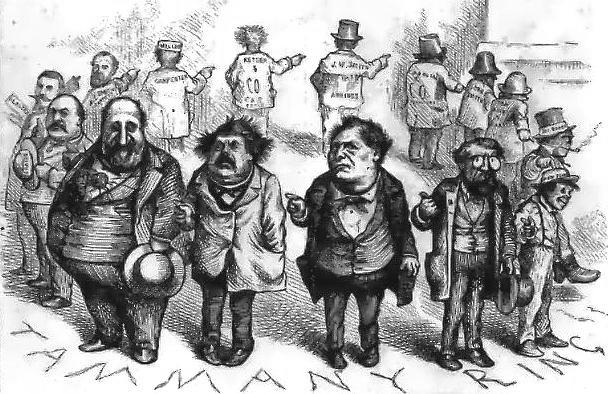

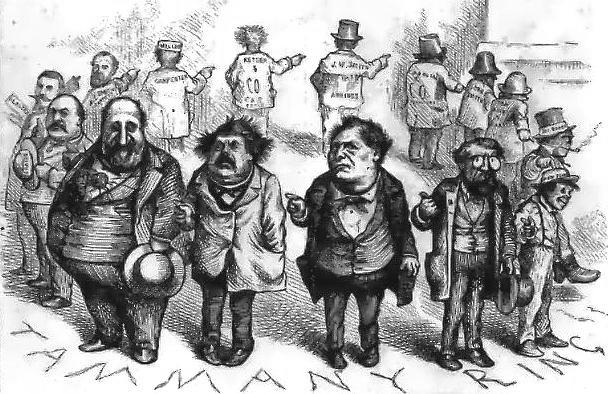

After the

After the American Civil War

The American Civil War (April 12, 1861 – May 26, 1865; also known by other names) was a civil war in the United States. It was fought between the Union ("the North") and the Confederacy ("the South"), the latter formed by states ...

the Democratic Party under Boss William Tweed's Tammany Hall

Tammany Hall, also known as the Society of St. Tammany, the Sons of St. Tammany, or the Columbian Order, was a New York City political organization founded in 1786 and incorporated on May 12, 1789 as the Tammany Society. It became the main loc ...

gained a monopoly in both New York City Hall and the New York Legislature. Allegations of corruption rapidly grew as rumors spread that Boss Tweed and associates of Tammany Hall were laundering tax payers money in real estate and bribing New York State legislatures for favorable legislation. New York City workers under the Tammany Hall system were paid excessive rates on the burden of tax payers. By 1871, New York City residents and the press demanded that the corruption be investigated and cleaned up. On September 4, at Cooper Union, a large organization of reputed citizens was formed known as the ''Committee of Seventy

The Committee of Seventy is an independent, non-partisan advocate for better government in Philadelphia that works to achieve clean and effective government, better elections, and informed and engaged citizens. Founded in 1904, it is a nonprofit ...

'', that investigated the corruption of Boss Tweed's Tammany Hall Ring. Pierrepont was appointed to and actively served on the legislation commission of the ''Committee of Seventy''. The ''Committee of Seventy'' promised to thoroughly investigate Tammany Hall corruption and strongly encouraged honest voters to stop taking bribes from Tammany Hall at the polls during election. By the end of October 1871 the ''Committee of Seventy'' had successfully stopped funding Boss Tweed's Tammany Hall by court injunction effectively shutting down the corrupt institution. Tweed was arrested and thrown into jail.

Supported President Grant

180px , left , President Ulysses S. Grant—Mathew Brady 1869 On September 25, 1872 reformer Pierrepont gave a speech at the

Cooper Union Institute

The Cooper Union for the Advancement of Science and Art (Cooper Union) is a private college at Cooper Square in New York City. Peter Cooper founded the institution in 1859 after learning about the government-supported École Polytechnique in ...

in New York that supported President Grant's reelection.Pierrepont (September 25, 1872), ''Speech of the Hon. Edwards Pierrepont'', p. 1 Pierrepont stated that Grant's opponent Horace Greeley had pointed out that Grant had made a better President than expected and that his second term would be better than his first.Pierrepont (September 25, 1872), ''Speech of the Hon. Edwards Pierrepont'', p. 22 Pierrepont stated that President Grant had been unjustly slandered by the press, and that he believed "security, confidence, development and unexampled prosperity" would take place during President Grant's second term in office. Pierrepont, who had toured the South in February, spoke on President Grant's Reconstruction policy.Pierrepont (September 25, 1872), ''Speech of the Hon. Edwards Pierrepont'', p. 23 Pierrepont had observed that southern whites in poverty supported Greeley, while African Americans were loyal to President Grant. Although acknowledging Reconstruction state governments needed reform, Pierrepont blamed southern poverty on the Southern peoples "swollen pride and obstinate will". Pierrepont believed that Grant's southern policy was good for the Southern people; that African American

African Americans (also referred to as Black Americans and Afro-Americans) are an ethnic group consisting of Americans with partial or total ancestry from sub-Saharan Africa. The term "African American" generally denotes descendants of ens ...

s needed to be protected in their rights; and that government needed to govern justly and generously. Pierrepont believed that electing Greeley would turn over the state governments to a rebellious people and reminded his audience of Union prisoner deaths that had taken place at Andersonville and harsh conditions at Libby Prison

Libby Prison was a Confederate prison at Richmond, Virginia, during the American Civil War. In 1862 it was designated to hold officer prisoners from the Union Army. It gained an infamous reputation for the overcrowded and harsh conditions. Priso ...

. As a reformer, Pierrepont stated he would do his best to ensure that honest men were placed around President Grant.Pierrepont (September 25, 1872), ''Speech of the Hon. Edwards Pierrepont'', pp. 21–22

On October 11, 1872 Edwards Pierrepont spoke in Ithaca, New York

Ithaca is a city in the Finger Lakes region of New York, United States. Situated on the southern shore of Cayuga Lake, Ithaca is the seat of Tompkins County and the largest community in the Ithaca metropolitan statistical area. It is named ...

supporting President Grant and the Republican ticket. Pierrepont related a story of President Grant unworried he would not win North Carolina

North Carolina () is a state in the Southeastern region of the United States. The state is the 28th largest and 9th-most populous of the United States. It is bordered by Virginia to the north, the Atlantic Ocean to the east, Georgia and ...

. Although there was concern that Grant would not win North Carolina, Pierrepont stated that Grant had said to a friend when wolves howl at night the sound is greater than the actual number of wolves. According to President Grant, this was the case in North Carolina. Pierrepont predicted Grant would win New York for seven reasons including that Grant had already won the state in 1868 when the Democratic coalition was at its height, the Republicans had carried the state government, and that Grant would receive 17,000 votes from African Americans. Pierrepont stated the Tammany Ring would no longer be instrumental in securing the Democratic vote through fraud. Pierrepont had earlier been instrumental in prosecuting the Tammany Ring that was completely shut down. With the prosecution of the Ku Klux Klan by President Grant and Pierrepont's shutting down the Tammany Ring, the general election of 1872 was one of the most fair in United States history.

Saint-Gaudens bust

In 1874, Pierrepont hired a young and upcoming Irish born sculptorAugustus Saint-Gaudens

Augustus Saint-Gaudens (; March 1, 1848 – August 3, 1907) was an American sculptor of the Beaux-Arts generation who embodied the ideals of the American Renaissance. From a French-Irish family, Saint-Gaudens was raised in New York City, he trav ...

to create a marble bust of himself. Pierrepont, who practiced phrenology, believed that having a wide head was a sign of intelligence. Pierrepont was an admirer of Plato

Plato ( ; grc-gre, Πλάτων ; 428/427 or 424/423 – 348/347 BC) was a Greek philosopher born in Athens during the Classical period in Ancient Greece. He founded the Platonist school of thought and the Academy, the first institution ...

, Socrates

Socrates (; ; –399 BC) was a Greek philosopher from Athens who is credited as the founder of Western philosophy and among the first moral philosophers of the ethical tradition of thought. An enigmatic figure, Socrates authored no te ...

, and Aristotle

Aristotle (; grc-gre, Ἀριστοτέλης ''Aristotélēs'', ; 384–322 BC) was a Greek philosopher and polymath during the Classical period in Ancient Greece. Taught by Plato, he was the founder of the Peripatetic school of ph ...

and he wanted his head to be wide as theirs were. Pierrepont turned out to be a demanding patron as he insisted Saint-Gaudens make his head larger on the bust. Although Saint-Gaudens complied, he was upset at Pierrepont for having to make his head larger. Saint-Gaudens said that Pierrepont's bust "seemed to be affected with some dreadful swelling disease". Saint-Gaudens was so upset over the Pierrepont portrait sculpture that he later stated to a friend, David Armstrong, he would "give anything to get hold of that bust and smash it to atoms".

U.S. Attorney General

President

President most commonly refers to:

*President (corporate title)

* President (education), a leader of a college or university

* President (government title)

President may also refer to:

Automobiles

* Nissan President, a 1966–2010 Japanese ...

Ulysses S. Grant

Ulysses S. Grant (born Hiram Ulysses Grant ; April 27, 1822July 23, 1885) was an American military officer and politician who served as the 18th president of the United States from 1869 to 1877. As Commanding General, he led the Union Ar ...

appointed Pierrepont Attorney General of the United States on April 26, 1875. A former Democrat

Democrat, Democrats, or Democratic may refer to:

Politics

*A proponent of democracy, or democratic government; a form of government involving rule by the people.

*A member of a Democratic Party:

**Democratic Party (United States) (D)

**Democratic ...

, Pierrepont had difficulty fitting into the Grant Administration, as stress was created during his tenure because of the prosecution of the Whiskey Ring and the indictment of Grant's private secretary, American Civil War

The American Civil War (April 12, 1861 – May 26, 1865; also known by other names) was a civil war in the United States. It was fought between the Union ("the North") and the Confederacy ("the South"), the latter formed by states ...

general, Orville E. Babcock

Orville Elias Babcock (December 25, 1835 – June 2, 1884) was an American engineer and general in the Union Army during the Civil War. An aide to General Ulysses S. Grant during and after the war, he was President Grant's military private secret ...

. Pierrepont, a reformer, was teamed up by President Grant with Secretary of Treasury, Benjamin Bristow

Benjamin Helm Bristow (June 20, 1832 – June 22, 1896) was an American lawyer and politician who served as the 30th U.S. Treasury Secretary and the first Solicitor General.

A Union military officer, Bristow was a Republican Party reformer and ...

to rid the government of corruption. Sec. Bristow had discovered whiskey distillers had created a government ring that profiteered by evading payment of taxes on the manufacturing of whiskey. Pierrepont was also involved with Reconstruction

Reconstruction may refer to:

Politics, history, and sociology

*Reconstruction (law), the transfer of a company's (or several companies') business to a new company

*'' Perestroika'' (Russian for "reconstruction"), a late 20th century Soviet Unio ...

, as President Grant administered Southern policy through the Attorney General's Justice Department and the War Department. In terms of southern Reconstruction

Reconstruction may refer to:

Politics, history, and sociology

*Reconstruction (law), the transfer of a company's (or several companies') business to a new company

*'' Perestroika'' (Russian for "reconstruction"), a late 20th century Soviet Unio ...

, Pierrepont continued his predecessors Att. Gen. George H. Williams's Spring, 1873 moratorium of prosecuting civil rights cases and in general was unresponsive to white violent attacks or outrages against African American

African Americans (also referred to as Black Americans and Afro-Americans) are an ethnic group consisting of Americans with partial or total ancestry from sub-Saharan Africa. The term "African American" generally denotes descendants of ens ...

citizens in the South. Pierrepont was more concerned for the restoration of the United States "international influence and political clout" after the American Civil War

The American Civil War (April 12, 1861 – May 26, 1865; also known by other names) was a civil war in the United States. It was fought between the Union ("the North") and the Confederacy ("the South"), the latter formed by states ...

and was primarily known for his rulings on international law, naturalization, and extradition. To change his Cabinet coalition, President Grant removed Pierrepont as Attorney General and appointed him minister to Great Britain.

Reforms (1875)

When Pierrepont assumed the office of U.S. Attorney General, he immediately implemented overdue reform in the South'sU.S. Marshal

The United States Marshals Service (USMS) is a federal law enforcement agency in the United States. The USMS is a bureau within the U.S. Department of Justice, operating under the direction of the Attorney General, but serves as the enforce ...

and U.S. Attorney

United States attorneys are officials of the U.S. Department of Justice who serve as the chief federal law enforcement officers in each of the 94 U.S. federal judicial districts. Each U.S. attorney serves as the United States' chief federal ...

departments. The culmination of these reforms took place in June 1875. Attorney General Pierrepont had given specific reform orders to U.S. Attorneys and U.S. Marshals in the South that were vigorously enforced. Pierrepont ran extensive investigations into the conduct of the U.S. Attorneys and U.S. Marshals, exposing fraud and corruption. Pierrepont was fully sustained by President Grant's endorsement of the investigations, reforms, and persons to be removed and replaced from office.

Naturalization (1875)

In July 1875 Attorney General Pierrepont ruled on the naturalization case of the son of a Prussian immigrant, Steinkoanler, who had immigrated to the United States in 1848. Steinkoanler was naturalized as a United States citizen in 1854. Steinkoanler returned to Prussia with his son, born in the United States, who was four years old. The naturalization case concerned whether Steinkoanler's son, who was then 20 years old, had to serve in the Prussian military, an obligation for all Prussian male children. Pierrepont ruled that Steinkoanler's son, had bothUnited States

The United States of America (U.S.A. or USA), commonly known as the United States (U.S. or US) or America, is a country primarily located in North America. It consists of 50 states, a federal district, five major unincorporated territori ...

and Prussian

Prussia, , Old Prussian: ''Prūsa'' or ''Prūsija'' was a German state on the southeast coast of the Baltic Sea. It formed the German Empire under Prussian rule when it united the German states in 1871. It was ''de facto'' dissolved by an e ...

citizenship, and was only obligated to serve in the Prussian military while under his father's care. However, after Steinkoanler had come of age on his own, he was free to return to the United States and as a U.S. citizen could even run for the President of the United States

The president of the United States (POTUS) is the head of state and head of government of the United States of America. The president directs the executive branch of the federal government and is the commander-in-chief of the United States ...

.

Chorpenning claim (1875)

On July 25, 1875, Attorney General Pierrepont ruled on what was denounced as a fraud known as the Chorpenning claim. Chorpenning had petitioned the post office in 1857 for payment of mail delivery in San Pedro and Carson's Valley. Chorpenning was paid $109,072.95 by Postmaster General Aaron V. Brown in 1857 for his postal services, however Chorpening, under protest, believed he deserved more compensation. On July 15, 1870, Congress authorized the Postmaster General to adjust the Chorpenning claim. On December 23, 1870, Grant's Postmaster GeneralJohn A. J. Creswell

John Andrew Jackson Creswell (November 18, 1828December 23, 1891) was an American politician and abolitionist from Maryland, who served as United States Representative, United States Senator, and as Postmaster General of the United States appo ...

ruled that Chorpenning was owed a $443,010.60 adjustment. On January 12, 1871 a House committee suspended payment to Chorpenning. On February 9, 1871 Congress repealed the July 15, 1870 law that allowed the Postmaster General to adjust the Chorpenning claim. On March 3, 1871 Congress forbid that any appropriations go to pay the Chorpenning claim. On May 8, 1872 Congress again forbid any appropriations to pay for the Chorpening claim. Pierrepont ruled that Postmaster General Creswell was not an arbitrator between Chorpenning and Congress. Chorpenning's legal counsel argued that Congress was bound to pay any contracts between Congress and a private citizen. Pierrepont argued citing ''Gordon v United States'' that the Postmaster served as in a ministerial position rather than judicial, and therefore Creswell's adjustment was not binding. Pierrepont referred the Chorpening claim to the Court of Collections and allowed the next Congress to decide the fate of the Chorpening claim, unless the statute of limitations stopped the claim.

Mississippi (1875)

President Grant's Reconstruction policy worked through the U.S. Attorney General and the Justice Department, in addition to the Secretary of War and the War Department.Smith (2001), ''Grant'', p. 542 During later Reconstruction white supremacists known as ''white liners'' in both the North and the South put pressure on the Grant Administration to limit the use of deployed troops in the South that protected African American citizens under the Reconstruction Act of 1867.McFeely (1981), ''Grant A Biography'', pp 418–419 Previously President Grant had destroyed the Ku Klux Klan under the Enforcement Acts in 1871. Resistance continued and resurged as white liners violently attacked Mississippi blacks in 1875.McFeely (1981), ''Grant A Biography'', p. 420 Republican GovernorAdelbert Ames

Adelbert Ames (October 31, 1835 – April 13, 1933) was an American sailor, soldier, and politician who served with distinction as a Union Army general during the American Civil War. A Radical Republican, he was military governor, U.S. Senat ...

requested troops to protect black voters. In order to avoid violence, Attorney General Pierrepont sent George K. Chase to Mississippi who met with white liner leaders to hold them to their previous pledge not to use violence during the election. President Grant and Att. Gen. Pierrepont told Governor Ames to use federal troops only if the white liners used violence on election day. No violence took place on election day, however, the intimidation tactics of the white liners prior to the election kept blacks and Republican voters from the polls.McFeely (1981), ''Grant A Biography'', pp. 423–424

Whiskey Ring (1875–1876)

180px , thumb , A cartoon that lampooned the Whiskey Ring. After theAmerican Civil War

The American Civil War (April 12, 1861 – May 26, 1865; also known by other names) was a civil war in the United States. It was fought between the Union ("the North") and the Confederacy ("the South"), the latter formed by states ...

, whiskey distillers in St. Louis developed a tax evasion ring that depleted the U.S. Treasury. By 1875, the Whiskey Ring had grown into a nationwide criminal syndicate that included whiskey distillers, brokers, and government officials; making enormous profits from the sale of untaxed whiskey. Also rumored, was that in 1872 the Ring had secretly funded the Republican Presidential campaign. In an effort of reform and to clean up corruption, President Ulysses S. Grant appointed Benjamin Bristow

Benjamin Helm Bristow (June 20, 1832 – June 22, 1896) was an American lawyer and politician who served as the 30th U.S. Treasury Secretary and the first Solicitor General.

A Union military officer, Bristow was a Republican Party reformer and ...

, as U.S. Secretary of Treasury in 1874, who immediately discovered millions of dollars were being depleted from the U.S. Treasury.Smith (1981), ''Grant'', p. 584 Under orders from President Grant, in May 1875, Sec. Bristow struck hard at the Ring, nationally shutting down distilleries, arresting hundreds involved in the ring having obtained over 350 indictments. The Ring through Bristow's vigorous raids had been effectively shut down. In April 1875, President Grant appointed Pierrepont Attorney General and teamed him up with Bristow to prosecute the Ring and clean up corruption.Smith (2001), ''Grant'', p. 585 Pierrepont and the Justice Department created by Grant prosecuted the Whiskey Ring. Under orders from Grant Pierrepont controversially sent circular letters to district attorneys in Milwaukee, Chicago, and St. Louis denying immunity to offenders who would testify against the ring. Pierrepont's prosecution of the ring however was viewed satisfactory by the public.

During the Summer of 1875, both Bristow and Pierrepont obtained President Grant's order to "let know guilty man escape". During the Fall of 1875, evidence was discovered that Grant's private secretary, Orville Babcock

Orville Elias Babcock (December 25, 1835 – June 2, 1884) was an American engineer and general in the Union Army during the Civil War. An aide to General Ulysses S. Grant during and after the war, he was President Grant's military private secret ...

had been involved in the Ring. Bristow and Pierrepont, stayed behind after a cabinet meeting with President Grant and showed him correspondence between Babcock and William Joyce in St. Louis, indicted in the Ring, cryptic telegram messages as evidence of Babcock's involvement in the Ring. Babcock was summoned to the Oval Office for an explanation and was told to send a telegram to bring Wilson to Washington, D.C. After Babcock did not return to the Oval Office, Pierrepont discovered Babcock was in the process of writing a letter warning Wilson to be on his guard. This angered Attorney General Pierrepont, who spilled ink over Babcock's letter and shouted, "You don't want to send your argument; send the fact, and go there and make your explanation. I do not understand it."McFeely (1981), ''Grant A Biography'', p. 411 Babcock was indicted and later acquitted in a trial in St. Louis, after an oral deposition from President Grant defending Babcock was given to the jury. The Justice Department obtained 110 convictions of persons involved in the Whiskey Ring.

In March 1876, a rumor spread throughout Washington, D.C., that Attorney General Pierrepont had given information to aid the defense counsel of Orville Babcock

Orville Elias Babcock (December 25, 1835 – June 2, 1884) was an American engineer and general in the Union Army during the Civil War. An aide to General Ulysses S. Grant during and after the war, he was President Grant's military private secret ...

in St. Louis. Pierrepont publicly denied the allegation in a letter to Scott Lord and stated the rumor was "an infamous falsehood". Pierrepont suspected that Gen. Babcock himself was the source of the rumor. Babcock was dismissed as Grant's personal secretary after Babcock's acquittal in St. Louis. Pierrepont also denied the rumor that himself and Secretary Bristow were at odds with each other. Pierrepont produced a letter from October 1875 to Bluford Wilson

Bluford Wilson (November 30, 1841 – July 15, 1924) was a Union Army officer in the Civil War and a government official who served as Solicitor of the United States Treasury.

Early life

Bluford Wilson was born near Shawneetown, Illinois on No ...

, Bristow's assistant during the Whiskey Ring raids, that proved Bristow and Pierrepont were working together in harmony during the Whiskey Ring prosecutions.

U.S. Minister to Britain

left, 150px, On May 22, 1876 President Grant appointed PierrepontMinister Plenipotentiary

An envoy extraordinary and minister plenipotentiary, usually known as a minister, was a diplomatic head of mission who was ranked below ambassador. A diplomatic mission headed by an envoy was known as a legation rather than an embassy. Under the ...

of the United States to Britain, having replaced Robert Schenck, serving until December 1, 1877.McFeely, p. 439 While serving as minister to Britain, Pierrepont became interested in bimetalism

Bimetallism, also known as the bimetallic standard, is a monetary standard in which the value of the monetary unit is defined as equivalent to certain quantities of two metals, typically gold and silver, creating a fixed rate of exchange betwee ...

, frequently traveling to France, a bimetalist country.''The Atlanta Constitution'' (April 29, 1886), "Edwards Pierreont The Distinguished Ex-Minister Visits the Gate City", p. 8

On June 5, 1877 Pierrepont gave a reception for former President Ulysses S. Grant at his elaborate house on Cavendish Square

Cavendish Square is a public garden square in Marylebone in the West End of London. It has a double-helix underground commercial car park. Its northern road forms ends of four streets: of Wigmore Street that runs to Portman Square in the much la ...

. The Prince of Wales Edward Albert

Edward Laurence Albert (February 20, 1951 – September 22, 2006) was an American actor. The son of actor Eddie Albert and Mexican actress Margo, he starred opposite Goldie Hawn in ''Butterflies Are Free'' (1972), a role for which he won a ...

, Foreign Secretary Lord Derby Edward Stanley, William Gladstone and his wife Catherine

Katherine, also spelled Catherine, and other variations are feminine names. They are popular in Christian countries because of their derivation from the name of one of the first Christian saints, Catherine of Alexandria.

In the early Christ ...

, and American journalist Kate Field

Mary Katherine Keemle "Kate" Field ( pen name, Straws, Jr.; October 1, 1838 – May 19, 1896) was an American journalist, correspondent, editor, lecturer, and actress, of eccentric talent. She never married. She seemed ready to give an opinio ...

attended the formal affair.McFeely, p. 455 Although Grant was well received by the British public, a diplomatic controversy was caused when British officials including Prime Minister Benjamin Disraeli told Pierrepont that as a former head of state, Grant was nothing more than a "commoner", and could not be recognized by the government. Lord Derby, minister of foreign affairs, told Pierrepont that since Grant had no formal rank in the United States, he had none in Britain. Pierrepont countered Derby saying that first Napoleon

Napoleon Bonaparte ; it, Napoleone Bonaparte, ; co, Napulione Buonaparte. (born Napoleone Buonaparte; 15 August 1769 – 5 May 1821), later known by his regnal name Napoleon I, was a French military commander and political leader who ...

had been elected ruler, not by hereditary lineage, and yet the succeeding Bonaparte emperors were recognized by England: "Once an Emperor always an Emperor." Therefore, the same precedent applied to an elected head of state: "Once a President always a President." Grant's diplomatic recognition, although informal, came when Queen Victoria

Victoria (Alexandrina Victoria; 24 May 1819 – 22 January 1901) was Queen of the United Kingdom of Great Britain and Ireland from 20 June 1837 until her death in 1901. Her reign of 63 years and 216 days was longer than that of any previo ...

invited him to Windsor Castle. The Grants accepted, and on June 26, 1877 Pierrepont introduced the former president to the Queen.McFeely, p. 458 She received them in an appropriate setting, the castle's magnificent 520 feet quadrangle.

After his tenure as Minister Plenipotentiary ended, Pierrepont returned to the United States and resumed his private legal practice in New York.

Retirement

Transcontinental trip to Alaska

220px , right , Wrangell Harbor, Alaska 1897 In 1883, at the age of 66, Pierrepont and his son Edwin Willoughby Pierrepont took a transcontinental trip to the far reaches ofAlaska

Alaska ( ; russian: Аляска, Alyaska; ale, Alax̂sxax̂; ; ems, Alas'kaaq; Yup'ik: ''Alaskaq''; tli, Anáaski) is a state located in the Western United States on the northwest extremity of North America. A semi-exclave of the U.S. ...

starting from New York.''West's Encyclopedia of American Law'' (2005), "Pierrepont, Edwards" p. 447, vol. 2 On July 25 Pierrepont and Edwin visited Fort Wrangell, having sailed by ship into Wrangell Harbor.Edward Pierrepont (1884), ''Fifth Avenue to Alaska'', pp. 179–180 Edwin was impressed by the mirror reflection of the snow-capped mountains in the harbor waters. Upon their return, Pierrepont and Edwin published a widespread paper titled, "Fifth Avenue to Alaska" in 1884. Edwin was awarded a fellowship to the Royal Geographical Society of England. The long trip took a health toll on him and he died in 1885.

Visited Atlanta

thumb , 190px , left , Kimball House 1890 On August 28, 1886, Pierrepont and his wife visitedAtlanta, Georgia

Atlanta ( ) is the capital and most populous city of the U.S. state of Georgia. It is the seat of Fulton County, the most populous county in Georgia, but its territory falls in both Fulton and DeKalb counties. With a population of 498,7 ...

, staying at the Kimball House. The year before Pierrepont had submitted a letter published by ''The Atlanta Constitution'' on bimetalism

Bimetallism, also known as the bimetallic standard, is a monetary standard in which the value of the monetary unit is defined as equivalent to certain quantities of two metals, typically gold and silver, creating a fixed rate of exchange betwee ...

, a topic of popular discussion during the 1880s. Pierrepont favored a bimetalist economy believing that having two metal currencies would alleviate poverty and would keep a few wealthy businessmen from monopolizing a single gold standard currency. While in Atlanta, Pierrepont stated that the relations between the North and the South had improved and that the Southerners bore no ill will to the North. Pierrepont believed Atlanta was a model city for Southern industrialization. The Pierreponts toured the South in search of a place to improve Margaretta's health condition. Mrs. Pierrepont had suffered from grief after the death of their son Edwin, who had died of a fever in Rome in 1885.

Illness, death, and funeral

180px , right , thumb , Pierrepont's funeral service was held at the gothic cathedral, Calvary Church, on March 9, 1892. According to ''The New York Times

''The New York Times'' (''the Times'', ''NYT'', or the Gray Lady) is a daily newspaper based in New York City with a worldwide readership reported in 2020 to comprise a declining 840,000 paid print subscribers, and a growing 6 million paid d ...

'', in late 1889, Pierrepont suffered a nervous disease that "deprived him of the use of his limbs". Although Pierrepont was an invalid

Invalid may refer to:

* Patient, a sick person

* one who is confined to home or bed because of illness, disability or injury (sometimes considered a politically incorrect term)

* .invalid, a top-level Internet domain not intended for real use

As t ...

, for the next two and one-half years he was able to carry on most of his law practice and travel back and forth from his New York residence to his mansion in Garrison. On Wednesday, March 2, 1892, Pierrepont suffered a massive stroke that paralyzed the right side of his body and he lost the ability to speak. Four days later on March 6, Pierrepont died in the house in New York he had built 40 years earlier.

The funeral services were done by Rev. Dr. Henry Y. Satterlee at Calvary Church on Wednesday March 9, at 10 am. Pierrepont's body was transferred to Garrison where he was buried at St. Philip's Cemetery, accompanied by 10 prominent pallbearers.

Legacy

Pierrepont is primarily known for his success as an attorney appearing for well-known clients in important cases, and for fighting political corruption in federal, state, and city offices. This includes his successful prosecution and shutting down the Whiskey Ring, a national tax evasion syndicate, from 1875 to 1876. Politically, Pierrepont's success relied mainly on his appointments to office by President Ulysses S. Grant to U.S. Attorney for New York, U.S. Attorney General, and U.S. Minister to Great Britain. Pierrepont is also known for his publications of pamphlets on financial questions, mainly supporting bimetallic standard of U.S. currency. Although Pierrepont's tenure as Attorney General took place duringReconstruction

Reconstruction may refer to:

Politics, history, and sociology

*Reconstruction (law), the transfer of a company's (or several companies') business to a new company

*'' Perestroika'' (Russian for "reconstruction"), a late 20th century Soviet Unio ...

, his primary interest at the Justice Department was ruling on cases that determined the rights of U.S. citizens abroad. Certain Supreme Court rulings against the Enforcement Acts signed into law by President Grant, hampered Pierrepont's enforcement of civil rights in the United States.

References

Sources

Books

* * * * * *Internet

*External links

Hurst-Pierrepont Estate ''Aerial View''

from Bing Maps

Miniature Model of Hurst-Pierrepont Estate Mansion

from New York Botanical Gardens

Guide to the Edwards Pierrepont papers

from New York Public Library

Marble sculptures of Judge Edwards Pierrepont and Margaretta Willoughby Pierrepont

Marble sculptures of Judge Edwards Pierrepont and Margaretta Willoughby Pierrepont created by artist

Augustus Saint-Gaudens

Augustus Saint-Gaudens (; March 1, 1848 – August 3, 1907) was an American sculptor of the Beaux-Arts generation who embodied the ideals of the American Renaissance. From a French-Irish family, Saint-Gaudens was raised in New York City, he trav ...

in 1874. Smithsonian. ''Dynamic views.''

*Edwards Pierrepont papers (MS 400). Manuscripts and Archives, Yale University Library{{DEFAULTSORT:Pierrepont, Edwards 1817 births 1892 deaths New York Supreme Court Justices United States Attorneys General People of New York (state) in the American Civil War Yale Law School alumni People from North Haven, Connecticut Politicians from New York City Ambassadors of the United States to the United Kingdom Grant administration cabinet members 19th-century American politicians 19th-century American diplomats New York (state) Democrats New York (state) Republicans Lawyers from New York City American anti-corruption activists