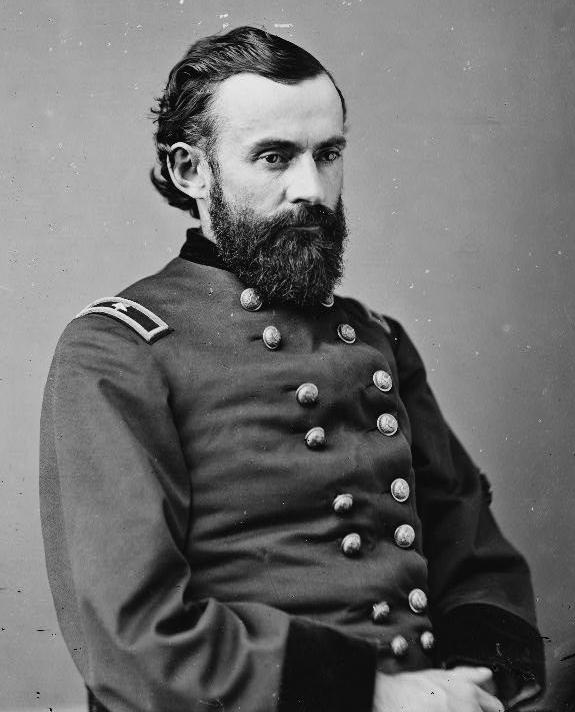

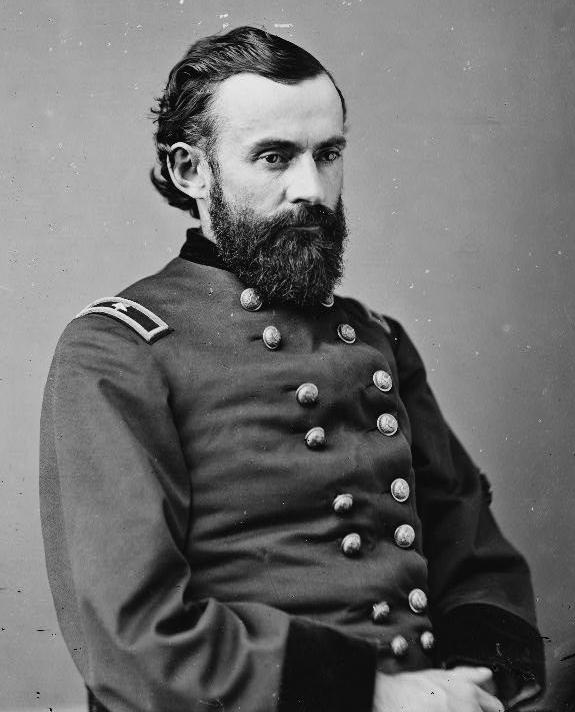

Edward Stuyvesant Bragg (February 20, 1827June 20, 1912) was an American politician, lawyer, soldier, and diplomat. He was an accomplished

Union Army

During the American Civil War, the Union Army, also known as the Federal Army and the Northern Army, referring to the United States Army, was the land force that fought to preserve the Union of the collective states. It proved essential to th ...

officer in the

American Civil War

The American Civil War (April 12, 1861 – May 26, 1865; also known by other names) was a civil war in the United States. It was fought between the Union ("the North") and the Confederacy ("the South"), the latter formed by states ...

and served four terms in the

United States House of Representatives

The United States House of Representatives, often referred to as the House of Representatives, the U.S. House, or simply the House, is the lower chamber of the United States Congress, with the Senate being the upper chamber. Together they ...

representing

Wisconsin

Wisconsin () is a state in the upper Midwestern United States. Wisconsin is the 25th-largest state by total area and the 20th-most populous. It is bordered by Minnesota to the west, Iowa to the southwest, Illinois to the south, Lake M ...

. Later, he was

United States Minister to Mexico during the presidency of

Grover Cleveland

Stephen Grover Cleveland (March 18, 1837June 24, 1908) was an American lawyer and politician who served as the 22nd and 24th president of the United States from 1885 to 1889 and from 1893 to 1897. Cleveland is the only president in American ...

, and

consul-general

A consul is an official representative of the government of one state in the territory of another, normally acting to assist and protect the citizens of the consul's own country, as well as to facilitate trade and friendship between the people ...

to the

Republic of Cuba

Cuba ( , ), officially the Republic of Cuba ( es, República de Cuba, links=no ), is an island country comprising the island of Cuba, as well as Isla de la Juventud and several minor archipelagos. Cuba is located where the northern Caribbean ...

and

British Hong Kong under President

Theodore Roosevelt

Theodore Roosevelt Jr. ( ; October 27, 1858 – January 6, 1919), often referred to as Teddy or by his initials, T. R., was an American politician, statesman, soldier, conservationist, naturalist, historian, and writer who served as the 26t ...

.

Early life and career

Bragg was born in

Unadilla, New York

Unadilla is a town in Otsego County, New York, United States. As of the 2010 census, the town had a population of 4,392. The name is derived from an Iroquois word for "meeting place". Unadilla is located in the southwestern corner of the county, ...

, the son of Margarette (Kohl) and Joel B. Bragg.

[ ] Bragg attended district schools as a child. He then attended the local academy and Geneva College (today

Hobart College) in

Geneva, New York

Geneva is a city in Ontario and Seneca counties in the U.S. state of New York. It is at the northern end of Seneca Lake; all land portions of the city are within Ontario County; the water portions are in Seneca County. The population was 13, ...

,

where he was one of the charter members of the

Kappa Alpha Society

The Kappa Alpha Society (), founded in 1825, was the progenitor of the modern fraternity system in North America. It is considered to be the oldest national, secret, Greek-letter social fraternity and was the first of the fraternities which would ...

. He left college before graduating, in 1847, and studied law in the offices of Judge Charles C. Noble. He was admitted to the

New York State Bar Association

The New York State Bar Association (NYSBA) is a voluntary bar association for the state of New York. The mission of the association is to cultivate the science of jurisprudence; promote reform in the law; facilitate the administration of justic ...

in 1848, and worked as a junior partner with Judge Noble until 1850.

In 1850, he traveled west on a prospecting tour in

Wisconsin

Wisconsin () is a state in the upper Midwestern United States. Wisconsin is the 25th-largest state by total area and the 20th-most populous. It is bordered by Minnesota to the west, Iowa to the southwest, Illinois to the south, Lake M ...

, intending to settle near

Green Bay. On the road between Chicago and Green Bay, he recognized the name of a former schoolmate on a sign at

Fond du Lac, Wisconsin, and decided to settle there.

Bragg quickly rose in prominence in Fond du Lac, associating himself with the

Democratic Party Democratic Party most often refers to:

*Democratic Party (United States)

Democratic Party and similar terms may also refer to:

Active parties Africa

*Botswana Democratic Party

*Democratic Party of Equatorial Guinea

*Gabonese Democratic Party

*Demo ...

. He was elected

district attorney of Fond du Lac in 1853 and was a delegate to the

1860 Democratic National Convention

The 1860 Democratic National Conventions were a series of presidential nominating conventions held to nominate the Democratic Party's candidates for president and vice president in the 1860 election. The first convention, held from April 23 t ...

in

Charleston, South Carolina, which nominated

Stephen A. Douglas

Stephen Arnold Douglas (April 23, 1813 – June 3, 1861) was an American politician and lawyer from Illinois. A senator, he was one of two nominees of the badly split Democratic Party for president in the 1860 presidential election, which wa ...

and

Herschel V. Johnson

Herschel Vespasian Johnson (September 18, 1812August 16, 1880) was an American politician. He was the 41st Governor of Georgia from 1853 to 1857 and the vice presidential nominee of the Douglas wing of the Democratic Party in the 1860 U.S. pre ...

for

President

President most commonly refers to:

*President (corporate title)

* President (education), a leader of a college or university

* President (government title)

President may also refer to:

Automobiles

* Nissan President, a 1966–2010 Japanese ...

and

Vice President

A vice president, also director in British English, is an officer in government or business who is below the president (chief executive officer) in rank. It can also refer to executive vice presidents, signifying that the vice president is on ...

of the United States.

Civil War service

When word arrived of the

attack on Fort Sumter, Bragg was engaged in a case at

Oshkosh, Wisconsin, where he was acting as

defense counsel

In a civil proceeding or criminal prosecution under the common law or under statute, a defendant may raise a defense (or defence) in an effort to avert civil liability or criminal conviction. A defense is put forward by a party to defeat ...

for a woman who had been accused of murder.

He requested a recess and immediately returned to Fond du Lac. That night he addressed an assembly in the city and an entire company of

"three-month" volunteers was raised. As Bragg went about arranging his personal affairs, the call came for another round of

volunteers

Volunteering is a voluntary act of an individual or group freely giving time and labor for community service. Many volunteers are specifically trained in the areas they work, such as medicine, education, or emergency rescue. Others serve ...

to enlist for three years service. Bragg recruited another company and was chosen as their captain. The company was referred to as "Bragg's Rifles" and would become Company E of the

6th Wisconsin Volunteer Infantry Regiment

The 6th Wisconsin Infantry Regiment was an infantry regiment that served in the Union Army during the American Civil War. It spent most of the war as a part of the famous Iron Brigade in the Army of the Potomac.

Service

The 6th Wisconsin was rai ...

.

The 6th Wisconsin was organized at

Camp Randall

Camp Randall was a United States Army base in Madison, Wisconsin, the largest staging point for Wisconsin troops entering the American Civil War. At this camp fresh volunteers received quick training before heading off to join the Union Army. Also ...

in

Madison, Wisconsin

Madison is the county seat of Dane County and the capital city of the U.S. state of Wisconsin. As of the 2020 census the population was 269,840, making it the second-largest city in Wisconsin by population, after Milwaukee, and the 80th-lar ...

, and mustered into service July 16, 1861, under Colonel

Lysander Cutler

Lysander Cutler (February 16, 1807July 30, 1866) was an American businessman, educator, politician, and Union Army General during the American Civil War.

Early years

Cutler was born in Royalston, Massachusetts, the son of a farmer. Despite object ...

.

They were ordered to proceed to

Washington, D.C.

)

, image_skyline =

, image_caption = Clockwise from top left: the Washington Monument and Lincoln Memorial on the National Mall, United States Capitol, Logan Circle, Jefferson Memorial, White House, Adams Morgan, ...

, for service in the

eastern theater of the war. Once at Washington, they were organized into the Brigade of General

Rufus King. They were soon joined by the

2nd Wisconsin,

7th Wisconsin, and

19th Indiana regiments in what would become known as the

Iron Brigade

The Iron Brigade, also known as The Black Hats, Black Hat Brigade, Iron Brigade of the West, and originally King's Wisconsin Brigade was an infantry brigade in the Union Army of the Potomac during the American Civil War. Although it fought ent ...

of the

Army of the Potomac

The Army of the Potomac was the principal Union Army in the Eastern Theater of the American Civil War. It was created in July 1861 shortly after the First Battle of Bull Run and was disbanded in June 1865 following the surrender of the Confede ...

.

From this point to the end of the war, Bragg participated in nearly every battle of the Iron Brigade.

Washington (Fall 1861Spring 1862)

The 6th Wisconsin spent the Fall of 1861 and Spring of 1862 on picket duty near Washington, building fortifications and drilling in preparation for combat.

During this time, Bragg was promoted to

major, on September 17, 1861, and then to

lieutenant colonel, on June 21, 1862, after Lt. Colonel

Benjamin Sweet

Benjamin Jeffery Sweet (April 24, 1832 – January 1, 1874) was an American lawyer, politician, public administrator, and Union Army officer. He was a member of the Wisconsin State Senate and a Deputy Commissioner of Internal Revenue.

Sweet ...

was commissioned colonel of the new

21st Wisconsin Volunteer Infantry Regiment

The 21st Wisconsin Infantry Regiment was a volunteer infantry regiment that served in the Union Army during the American Civil War. They were assigned for their entire war service to XIV Corps, operating in the western theater of the war.

Serv ...

.

Northern Virginia (Summer 1862)

In April 1862, the Iron Brigade marched south and camped at

Falmouth, Virginia

Falmouth is a census-designated place (CDP) in Stafford County, Virginia, United States. Situated on the north bank of the Rappahannock River at the falls, the community is north of and opposite the city of Fredericksburg. Recognized by the U. ...

, on the

Rappahannock River

The Rappahannock River is a river in eastern Virginia, in the United States, approximately in length.U.S. Geological Survey. National Hydrography Dataset high-resolution flowline dataThe National Map accessed April 1, 2011 It traverses the entir ...

, across from

Fredericksburg, Virginia, where they remained through most of the

Peninsula campaign.

In June, they were briefly put on alert to prepare to reinforce General

George B. McClellan

George Brinton McClellan (December 3, 1826 – October 29, 1885) was an American soldier, Civil War Union general, civil engineer, railroad executive, and politician who served as the 24th governor of New Jersey. A graduate of West Point, McCl ...

, but ultimately did not participate.

In July, after General

John Pope replaced McClellan in overall command of the Union Army, the Iron Brigade was assigned to participate in raids against Confederate infrastructure and logistics south of the Rappahannock.

The most notable is the raid on Frederick's Hall, in the first week of August, intended to cut the

Virginia Central Railroad

The Virginia Central Railroad was an early railroad in the U.S. state of Virginia that operated between 1850 and 1868 from Richmond westward for to Covington. Chartered in 1836 as the Louisa Railroad by the Virginia General Assembly, the railr ...

. Part of the 6th Wisconsin, including Lt. Colonel Bragg, was detached from the brigade and sent on a rapid march to the

North Anna River

The North Anna River is a principal tributary of the Pamunkey River, about long,U.S. Geological Survey. National Hydrography Dataset high-resolution flowline dataThe National Map accessed April 1, 2011 in central Virginia in the United States. ...

, where they discovered a large Confederate force was present on their flank. A council of the officers was called to discuss whether they should abandon their raid due to the danger of being cut off and captured. Bragg, along with Major

Rufus Dawes

Rufus R. Dawes (July 4, 1838August 1, 1899) was a military officer in the Union Army during the American Civil War. He used the middle initial "R" but had no middle name. He was noted for his service in the famed Iron Brigade, particularly duri ...

and Lt. Colonel

Hugh Judson Kilpatrick

Hugh Judson Kilpatrick (January 14, 1836 – December 4, 1881) was an officer in the Union Army during the American Civil War, achieving the rank of brevet major general. He was later the United States Minister to Chile and an unsuccessful cand ...

, were adamant that the raid should proceed.

The mission was ultimately successful as two miles of Virginia Central Railroad track were destroyed and the Union raiders returned safely to Falmouth.

Second Bull Run (August 1862)

The Iron Brigade arrived at

Cedar Mountain, Virginia, two days after the

battle

A battle is an occurrence of combat in warfare between opposing military units of any number or size. A war usually consists of multiple battles. In general, a battle is a military engagement that is well defined in duration, area, and force ...

there.

They participated in burying the dead and engaged in skirmishing, directed by Colonel Bragg, associated with the

First Battle of Rappahannock Station

The First Battle of Rappahannock Station, (also known as Waterloo Bridge, White Sulphur Springs, Lee Springs, and Freeman’s Ford) as took place on August 23, 1862, at present-day Remington, Virginia, as part of the Northern Virginia Campaign ...

along the new defensive line at the Rappahannock River.

After

Stonewall Jackson successfully maneuvered around the flank of the Union army, the order was given to fall back to

Centreville, Virginia

Centreville is a census-designated place (CDP) in Fairfax County, Virginia, United States and a suburb of Washington, D.C. The population was 73,518 as of the 2020 census. Centreville is approximately west of Washington, D.C.

History

Colonia ...

, in an attempt to surround Jackson's Corps. On the evening of August 28, while marching northeast with three other brigades on the

Warrenton Turnpike, the Iron Brigade encountered Jackson's Corps near

Gainesville, Virginia

Gainesville is a census-designated place (CDP) in western Prince William County, Virginia, United States. The population was 17,287 in the 2020 census.

History

Gainesville was once a changing point for stagecoach horses on the Fauquier & Alexa ...

.

General

Irvin McDowell

Irvin McDowell (October 15, 1818 – May 4, 1885) was a career American army officer. He is best known for his defeat in the First Battle of Bull Run, the first large-scale battle of the American Civil War. In 1862, he was given command ...

, who commanded their Division, was convinced that the Confederates represented an inconsequential force, and ordered the brigades to proceed on their march toward Centreville. However, when the Confederates opened up cannon fire, General

John Gibbon

John Gibbon (April 20, 1827 – February 6, 1896) was a career United States Army officer who fought in the American Civil War and the Indian Wars.

Early life

Gibbon was born in the Holmesburg section of Philadelphia, Pennsylvania, the four ...

ordered the Iron Brigade to engage the enemy and attempt to capture the artillery. A severe battle ensued as the Iron Brigade faced a combined assault from five brigades of Stonewall Jackson's Corps. During the battle, Colonel Cutler was severely wounded.

Lt. Colonel Bragg took command of the 6th Wisconsin and would remain in command of the regiment for most of the next two years.

Bragg and the 6th Wisconsin held the right end of the line against the brigades of

Isaac R. Trimble and

Alexander Lawton

Alexander Robert Lawton (November 4, 1818 – July 2, 1896) was a lawyer, politician, diplomat, and brigadier general in the Confederate States Army during the American Civil War.

Early life

Lawton was born in the Beaufort District of South ...

.

The fighting at Gainesville is often referred to in historical documents as the "Battle of Gainesville" and represented the first day of fighting in the

Second Battle of Bull Run.

Despite being outnumbered by more than 3-to-1, the brigade held their ground and the fighting ended indecisively around midnight. This is where the nickname "Iron Brigade" was first applied to their unit.

Bragg and the Iron Brigade were resting and remained in reserve during the second day of battle, but rejoined the fighting on the third day, August 30, 1862, in support of

Fitz John Porter

Fitz John Porter (August 31, 1822 – May 21, 1901) (sometimes written FitzJohn Porter or Fitz-John Porter) was a career United States Army officer and a Union general during the American Civil War. He is most known for his performance at the Se ...

's

V Corps 5th Corps, Fifth Corps, or V Corps may refer to:

France

* 5th Army Corps (France)

* V Cavalry Corps (Grande Armée), a cavalry unit of the Imperial French Army during the Napoleonic Wars

* V Corps (Grande Armée), a unit of the Imperial French Ar ...

and their ill-fated frontal assault on Jackson's position. As the attack faltered and the massive Confederate flanking attack began to materialize, Bragg held his regiment in line and deployed skirmishers to slow down the enemy attack.

As the Union army fell back, Bragg was ordered to organize the 6th Wisconsin to act as

rearguard

A rearguard is a part of a military force that protects it from attack from the rear, either during an advance or withdrawal. The term can also be used to describe forces protecting lines, such as communication lines, behind an army. Even more ...

.

The 6th Wisconsin was the last to withdraw, marching on an orderly retreat for nearly a mile in full view of both opposing armies.

As the Union army retreated from the field on the night of August 30, General

Philip Kearny

Philip Kearny Jr. (; June 1, 1815 – September 1, 1862) was a United States Army officer, notable for his leadership in the Mexican–American War and American Civil War. He was killed in action in the 1862 Battle of Chantilly.

Early life and c ...

ordered the Iron Brigade to act as rearguard for the Army.

Bragg and Lt. Colonel

Lucius Fairchild

Lucius Fairchild (December 27, 1831May 23, 1896) was an American politician, soldier, and diplomat. He served as the tenth Governor of Wisconsin and represented the United States as Minister to Spain under presidents Rutherford B. Hayes and Ja ...

—who commanded the consolidated 2nd and 7th Wisconsin—would manage the action, setting pickets and false campfires to deceive the enemy.

Maryland and Antietam (September 1862)

After the failure of Pope's campaign, General McClellan was put back in command of the Union army.

General

Robert E. Lee seized the initiative and

invaded Maryland

Maryland ( ) is a state in the Mid-Atlantic region of the United States. It shares borders with Virginia, West Virginia, and the District of Columbia to its south and west; Pennsylvania to its north; and Delaware and the Atlantic Ocean to ...

.

The Iron Brigade, now designated the 4th Brigade, 1st Division, in

Joseph Hooker

Joseph Hooker (November 13, 1814 – October 31, 1879) was an American Civil War general for the Union, chiefly remembered for his decisive defeat by Confederate General Robert E. Lee at the Battle of Chancellorsville in 1863.

Hooker had serv ...

's

I Corps I Corps, 1st Corps, or First Corps may refer to:

France

* 1st Army Corps (France)

* I Cavalry Corps (Grande Armée), a cavalry unit of the Imperial French Army during the Napoleonic Wars

* I Corps (Grande Armée), a unit of the Imperial French A ...

,

joined the Union pursuit of Lee into Maryland and encountered his army at

South Mountain, south of

Hagerstown, Maryland.

At the

Battle of South Mountain

The Battle of South Mountain—known in several early Southern accounts as the Battle of Boonsboro Gap—was fought on September 14, 1862, as part of the Maryland campaign of the American Civil War. Three pitched battles were fought for posses ...

, on September 14, 1862, the Iron Brigade received special instructions to proceed up the

National Road

The National Road (also known as the Cumberland Road) was the first major improved highway in the United States built by the federal government. Built between 1811 and 1837, the road connected the Potomac and Ohio Rivers and was a main tran ...

and engage

Alfred H. Colquitt's brigade at Turner's Gap.

Colonel Bragg commanded the 6th Wisconsin protecting the right flank of the attack,

maneuvering his regiment in good order over difficult terrain, then up the incline of the field to obtain a favorable field of fire over the enemy position.

From his vantage, General McClellan could see the fighting and later wrote to Wisconsin Governor

Edward Salomon

Edward Salomon (August 11, 1828April 21, 1909) was a Jewish American politician and the 8th Governor of Wisconsin, having ascended to office from the Lieutenant Governorship after the accidental drowning of his predecessor, Louis P. Harvey. ...

, "I beg to add my great admiration of the conduct of the three Wisconsin regiments in General Gibbon's brigade. I have seen them under fire acting in a manner that reflects the greatest possible credit and honor upon themselves and their state. They are equal to the best troops in any army in the world."

Lee evacuated South Mountain that evening, but McClellan caught up to him again at

Antietam Creek

Antietam Creek () is a U.S. Geological Survey. National Hydrography Dataset high-resolution flowline dataThe National Map, accessed August 15, 2011 tributary of the Potomac River located in south central Pennsylvania and western Maryland in the ...

, near

Sharpsburg, Maryland

Sharpsburg is a town in Washington County, Maryland. The town is approximately south of Hagerstown. Its population was 705 at the 2010 census.

During the American Civil War, the Battle of Antietam, sometimes referred to as the Battle of Sharpsb ...

, on September 16, 1862.

That night, the Iron Brigade, along with the rest of I Corps, crossed the Antietam Creek and took position on the far right of the Union line.

At dawn, the

Battle of Antietam began with I Corps advancing under artillery fire.

Bragg led the 6th Wisconsin at the far right end of the Union advance, where they came under attack from the woods on their right flank.

Bragg, despite having been shot in the initial barrage, ordered the men to reshape and return fire into the woods.

Bragg collapsed and was carried to the rear. He was able to return to the regiment around noon, but was not yet fit to return to duty.

In the aftermath of the battle, one of the sergeants mistakenly wrote to Bragg's wife informing her that he had been killed.

The story spread in Wisconsin and resulted in his obituary appearing in several papers.

Before Antietam, Bragg received solicitations from Wisconsin to run for Congress as a

War Democrat

War Democrats in American politics of the 1860s were members of the Democratic Party who supported the Union and rejected the policies of the Copperheads (or Peace Democrats). The War Democrats demanded a more aggressive policy toward the Con ...

on the

National Union Party ticket. Bragg had replied, "I shall not decline a nomination on the platform, the Government must be sustained, but my services can not be taken from the field. I command the regiment, and can not leave in times like these."

Nevertheless, after the battle, he received word that he had been nominated by the National Union Party district convention.

He ultimately lost the election to

anti-war Democrat Charles A. Eldredge.

Fredericksburg and Chancellorsville (Winter 1862Spring 1863)

In the Winter of 1862–63, there were two more Union offensives attempted against

Fredericksburg, Virginia. Bragg led the regiment through the

Battle of Fredericksburg and the aborted

Mud March, but they were not engaged in serious fighting in either campaign.

The Iron Brigade spent most of the rest of the winter camped at

Belle Plains, Virginia, where they were reorganized and resupplied. During this time, Bragg received his official promotion to

colonel

Colonel (abbreviated as Col., Col or COL) is a senior military officer rank used in many countries. It is also used in some police forces and paramilitary organizations.

In the 17th, 18th and 19th centuries, a colonel was typically in charge o ...

, effective March 10, 1863,

and was one of several officers invited to meet with President

Abraham Lincoln

Abraham Lincoln ( ; February 12, 1809 – April 15, 1865) was an American lawyer, politician, and statesman who served as the 16th president of the United States from 1861 until his assassination in 1865. Lincoln led the nation thro ...

.

The campaigning resumed in April 1863 under General

Joseph Hooker

Joseph Hooker (November 13, 1814 – October 31, 1879) was an American Civil War general for the Union, chiefly remembered for his decisive defeat by Confederate General Robert E. Lee at the Battle of Chancellorsville in 1863.

Hooker had serv ...

, now in overall command of the Army of the Potomac.

In the

Battle of Chancellorsville

The Battle of Chancellorsville, April 30 – May 6, 1863, was a major battle of the American Civil War (1861–1865), and the principal engagement of the Chancellorsville campaign.

Chancellorsville is known as Lee's "perfect battle" because h ...

, the Iron Brigade was charged with securing the creation of a pontoon bridge at Fitz Hughes Crossing on the Rappahannock, southeast of Fredericksburg.

After the bridge engineers came under attack from the far side of the river, Colonel Bragg was tasked with forcing a crossing and securing the far bank of the river.

Within an hour, Bragg had secured the beachhead and taken nearly 200 of Confederate prisoners.

Bragg and the 6th Wisconsin received special compliments from their division commander, General

James S. Wadsworth

James Samuel Wadsworth (October 30, 1807 – May 8, 1864) was a philanthropist, politician, and a Union general in the American Civil War. He was mortally wounded in battle during the Battle of the Wilderness of 1864.

Early years

Wadswor ...

, for the daring raid.

After crossing, they were joined by

VI Corps 6 Corps, 6th Corps, Sixth Corps, or VI Corps may refer to:

France

* VI Cavalry Corps (Grande Armée), a cavalry formation of the Imperial French army during the Napoleonic Wars

* VI Corps (Grande Armée), a formation of the Imperial French army du ...

and the rest of I Corps, forming the left wing of Hooker's attack. However, after remaining in position for two days under enemy shelling, on May 2, I Corps and the Iron Brigade were recalled to cross back to the north side of the river and move west to reinforce Hooker at Chancellorsville.

Ultimately, Hooker was forced to withdraw and the Iron Brigade and its Division again acted as rearguard for the Union retreat.

Colonel Bragg became seriously ill after Chancellorsville, possibly due to the poor weather conditions during the battle, combined with a wound he received from being kicked by Major John Hauser's horse.

He remained in his tent attempting to recuperate, but, in early June, was sent to a hospital in Washington, D.C.

While sick, Bragg missed the entire

Gettysburg campaign, leaving the regiment under the command of Lt. Colonel

Rufus Dawes

Rufus R. Dawes (July 4, 1838August 1, 1899) was a military officer in the Union Army during the American Civil War. He used the middle initial "R" but had no middle name. He was noted for his service in the famed Iron Brigade, particularly duri ...

, who performed heroic duty leading the regiment on the

first day of the Battle of Gettysburg.

Colonel Bragg briefly attempted to return to the regiment in the days after the

Battle of Gettysburg

The Battle of Gettysburg () was fought July 1–3, 1863, in and around the town of Gettysburg, Pennsylvania, by Union and Confederate forces during the American Civil War. In the battle, Union Major General George Meade's Army of the Po ...

but was still too ill to participate, and had to return again to medical care.

Bristoe, Mine Run, and Reorganization (Fall 1863Spring 1864)

Colonel Bragg returned to the 6th Wisconsin about August 28, 1863, finding them camped near Rappahannock Station.

In the

Bristoe campaign and the

Battle of Mine Run

The Battle of Mine Run, also known as Payne's Farm, or New Hope Church, or the Mine Run campaign (November 27 – December 2, 1863), was conducted in Orange County, Virginia, in the American Civil War.

An unsuccessful attempt of the Union ...

, the Iron Brigade engaged in a series of rapid maneuvers, but did not engage in serious fighting.

In January 1864, the 6th Wisconsin officially achieved Veteran status and those who re-enlisted were given a furlough to return to Wisconsin.

Bragg and the re-enlisted veterans traveled by train and were celebrated at a ceremony in

Milwaukee

Milwaukee ( ), officially the City of Milwaukee, is both the most populous and most densely populated city in the U.S. state of Wisconsin and the county seat of Milwaukee County. With a population of 577,222 at the 2020 census, Milwaukee ...

, hosted by former Governor Edward Salomon, Milwaukee Mayor

Edward O'Neill, and Bragg's former 2nd Wisconsin Regiment counterpart, General Lucius Fairchild—who had just been elected Wisconsin's Secretary of State.

Overland Campaign (Summer 1864)

In March 1864, General

Ulysses S. Grant

Ulysses S. Grant (born Hiram Ulysses Grant ; April 27, 1822July 23, 1885) was an American military officer and politician who served as the 18th president of the United States from 1869 to 1877. As Commanding General, he led the Union Ar ...

was appointed the commander of the Union Army in the Virginia theatre, replacing General

George Meade

George Gordon Meade (December 31, 1815 – November 6, 1872) was a United States Army officer and civil engineer best known for decisively defeating Confederate General Robert E. Lee at the Battle of Gettysburg in the American Civil War. H ...

, who had been in command since the Gettysburg Campaign. That same month, the Iron Brigade veterans returned to camp and engaged in drilling and reorganization under the new commander. For the next phase of the war, they would be the 1st Brigade, 4th Division, in

Gouverneur K. Warren

Gouverneur Kemble Warren (January 8, 1830 – August 8, 1882) was an American civil engineer and Union Army general during the American Civil War. He is best remembered for arranging the last-minute defense of Little Round Top during the Battle ...

's

V Corps 5th Corps, Fifth Corps, or V Corps may refer to:

France

* 5th Army Corps (France)

* V Cavalry Corps (Grande Armée), a cavalry unit of the Imperial French Army during the Napoleonic Wars

* V Corps (Grande Armée), a unit of the Imperial French Ar ...

.

On May 3, 1864, they returned to campaign, marching from their camp at Culpeper Court House. They arrived at the Wilderness Tavern south of the

Rapidan River

The Rapidan River, flowing U.S. Geological Survey. National Hydrography Dataset high-resolution flowline dataThe National Map accessed April 1, 2011 through north-central Virginia in the United States, is the largest tributary of the Rappahannock ...

at dusk on May 4.

On the morning of May 5, the Iron Brigade, along with their division, marched southwest and encountered the enemy in the woods at the start of what became the

Battle of the Wilderness.

The fighting in the woods was confusing and, after engaging with the enemy, Colonel Bragg ran out on his own to attempt to identify the location of other nearby Union regiments, nearly falling into the hands of the enemy.

That afternoon, their division received new orders to detach and proceed to the south to reinforce

Winfield Scott Hancock

Winfield Scott Hancock (February 14, 1824 – February 9, 1886) was a United States Army officer and the Democratic nominee for President of the United States in 1880. He served with distinction in the Army for four decades, including service ...

's II Corps and

John Sedgwick

John Sedgwick (September 13, 1813 – May 9, 1864) was a military officer and Union Army general during the American Civil War.

He was wounded three times at the Battle of Antietam while leading his division in an unsuccessful assault against Co ...

's VI Corps.

Near dawn on May 6, the fighting resumed as Sedgwick launched his attack. The Iron Brigade attacked the left flank of the Confederate

Third Corps under

A. P. Hill.

Though initially successful, the offensive stalled when elements of the Confederate

First Corps under

James Longstreet arrived and counterattacked.

The Union forces fell back under the Confederate counterattack but stabilized along the Brock Road, between Wilderness Tavern and

Todds Tavern, Virginia

Todds Tavern is an unincorporated community in Spotsylvania County, Virginia, USA, and was the site of the Battle of Todd's Tavern.

History

Todds Tavern was the focal point of a cavalry battle on 7-8 May 1864, between the battles of the Wilderne ...

.

After the fighting on May 6, Colonel Bragg was placed in command of the all-Pennsylvanian 3rd Brigade of their Division—sometimes referred to as the "Pennsylvania Bucktail Brigade"—by General Lysander Cutler.

Cutler, who had been Bragg's original commanding officer in the 6th Wisconsin, had become Division commander with the death of General

James S. Wadsworth

James Samuel Wadsworth (October 30, 1807 – May 8, 1864) was a philanthropist, politician, and a Union general in the American Civil War. He was mortally wounded in battle during the Battle of the Wilderness of 1864.

Early years

Wadswor ...

in the fighting earlier that day.

Bragg replaced Colonel

Roy Stone

Roy Stone (October 16, 1836 – August 5, 1905) was an American soldier, civil engineer, and inventor. He served in the American Civil War, distinguishing himself during the Battle of Gettysburg, and took part in the Spanish–American War. He ...

, who was reportedly drunk during the battle on both May 5 and May 6. On both days, his brigade had performed poorly, marching and firing in a disorganized manner, scattering in the face of Confederate skirmishers, and accidentally

shooting

Shooting is the act or process of discharging a projectile from a ranged weapon (such as a gun, bow, crossbow, slingshot, or blowpipe). Even the acts of launching flame, artillery, darts, harpoons, grenades, rockets, and guided missiles ...

at members of their own unit.

Stone was finally relieved of command after his horse fell on top of him as his lines broke again during the May 6 attack.

Colonel Bragg led the brigade for most of the remainder of the

Overland Campaign

The Overland Campaign, also known as Grant's Overland Campaign and the Wilderness Campaign, was a series of battles fought in Virginia during May and June 1864, in the American Civil War. Lt. Gen. Ulysses S. Grant, general-in-chief of all Union ...

. His leadership stabilized the brigade and they performed admirably at the battles of

Spotsylvania Court House

The Battle of Spotsylvania Court House, sometimes more simply referred to as the Battle of Spotsylvania (or the 19th-century spelling Spottsylvania), was the second major battle in Lt. Gen. Ulysses S. Grant and Maj. Gen. George G. Meade's 186 ...

,

North Anna,

Totopotomoy Creek, and

Cold Harbor

The Battle of Cold Harbor was fought during the American Civil War near Mechanicsville, Virginia, from May 31 to June 12, 1864, with the most significant fighting occurring on June 3. It was one of the final battles of Union Lt. Gen. Ulysses S ...

, where he turned over command of the brigade to Gettysburg hero

Joshua Chamberlain

Joshua Lawrence Chamberlain (born Lawrence Joshua Chamberlain, September 8, 1828February 24, 1914) was an American college professor from Maine who volunteered during the American Civil War to join the Union Army. He became a highly respected and ...

.

On the night of May 7, V Corps was ordered to proceed southeast toward

Spotsylvania Court House

The Battle of Spotsylvania Court House, sometimes more simply referred to as the Battle of Spotsylvania (or the 19th-century spelling Spottsylvania), was the second major battle in Lt. Gen. Ulysses S. Grant and Maj. Gen. George G. Meade's 186 ...

, as Grant attempted to maneuver his army in between Lee and the Confederate capitol, Richmond. Arriving at Laurel Hill, northwest of Spotsylvania Court House, on the morning of May 8, they found a Confederate force had already reached the site and occupied strong defensive positions.

Bragg's brigade participated in four Union assaults against the Confederate fortifications between May 8 and May 12.

On the afternoon of May 12, they marched to their left and engaged in fighting at the "Bloody Angle".

Colonel Bragg was, once again, incorrectly reported

killed in action after the fighting at Spotsylvania Court House. A letter from Colonel

Thomas Allen announced his death—along with the deaths of Lt. Colonel

Rufus Dawes

Rufus R. Dawes (July 4, 1838August 1, 1899) was a military officer in the Union Army during the American Civil War. He used the middle initial "R" but had no middle name. He was noted for his service in the famed Iron Brigade, particularly duri ...

and Captain

John Azor Kellogg—and was widely reprinted in several Wisconsin newspapers.

All three officers were actually alive and relatively unharmed—although Kellogg had been taken prisoner.

After days of skirmishing and shelling at the fortifications around Spotsylvania Court House, V Corps was again ordered to move to the south, continuing the maneuver toward Richmond. After stopping at Guinea's Station and the

Po River, they crossed the

North Anna River

The North Anna River is a principal tributary of the Pamunkey River, about long,U.S. Geological Survey. National Hydrography Dataset high-resolution flowline dataThe National Map accessed April 1, 2011 in central Virginia in the United States. ...

near dusk on May 23, 1864.

That evening, before they were able to fully establish their battle lines, they were attacked by Confederates of A. P. Hill's Third Corps in the first action of the

Battle of North Anna

The Battle of North Anna was fought May 23–26, 1864, as part of Union Lt. Gen. Ulysses S. Grant's Overland Campaign against Confederate Gen. Robert E. Lee's Army of Northern Virginia. It consisted of a series of small actions near the Nor ...

. After initially giving ground, the division rallied and drove the Confederates from the field.

After more days of entrenched stalemate, on the evening of May 26, Grant again ordered the Union divisions to stealthily evacuate their lines and proceed south around the Confederate right flank.

They crossed the

Pamunkey River on May 28 and set defensive lines behind the cavalry

Battle of Haw's Shop

The Battle of Haw's Shop or Enon Church was fought on May 28, 1864, in Hanover County, Virginia, as part of Union Lt. Gen. Ulysses S. Grant's Overland Campaign against Confederate Gen. Robert E. Lee's Army of Northern Virginia during the Amer ...

. They moved again on May 29 and May 30, encountering divisions of the Confederate 1st Corps at the

Battle of Totopotomoy Creek

The Battle of Totopotomoy Creek , also called the Battle of Bethesda Church, Crumps Creek, Shady Grove Road, and Hanovertown, was a battle fought in Hanover County, Virginia on May 28–30, 1864, as part of Union Lt. Gen. Ulysses Grant's O ...

and repelled them.

Over the next two weeks, they were engaged in the trench warfare of the

Battle of Cold Harbor

The Battle of Cold Harbor was fought during the American Civil War near Mechanicsville, Virginia, from May 31 to June 12, 1864, with the most significant fighting occurring on June 3. It was one of the final battles of Union Lt. Gen. Ulysses ...

.

On June 6, in the midst of this battle, Bragg's Pennsylvanian brigade was detached from the division and Bragg was placed in command of the Iron Brigade.

Colonel Bragg's account of the actions of the Pennsylvanian brigade during the Overland campaign can be found in the Official War Records, Series 1, Volume 36, Part 1, Item 141.

Siege of Petersburg (Summer 1864Spring 1865)

On June 12, they made another sudden evacuation of their position and crossed the

James River, engaging the

Siege of Petersburg

The Richmond–Petersburg campaign was a series of battles around Petersburg, Virginia, fought from June 9, 1864, to March 25, 1865, during the American Civil War. Although it is more popularly known as the Siege of Petersburg, it was not a cla ...

, and entrenching southeast of the city.

On June 18, they participated in the futile charge against the Petersburg defenses in the

Second Battle of Petersburg

The Second Battle of Petersburg, also known as the Assault on Petersburg, was fought June 15–18, 1864, at the beginning of the Richmond–Petersburg Campaign (popularly known as the Siege of Petersburg). Union forces under Lieutenant General U ...

. In the battle, the Iron Brigade was part of a general assault on the Confederate line, charging half a mile over open field toward the enemy.

They were ordered to halt under enemy fire and waited there for Union regiments on their left, which had become panicked and disorganized.

Ultimately, after nearly two hours under fire, they retreated to their trenches.

In his report of the battle, their division commander, General Lysander Cutler, said, "In this affair I lost in killed and wounded about one third of the men I had with me, and among them many valuable officers." He continued to say that they never reached within seventy five yards of the enemy lines.

For the next several weeks, they remained in position besieging Petersburg. They remained on the trench line—where they could be subject to sniper fire and artillery—until June 26, when they were relieved temporarily.

During this time, Colonel Bragg received word of his official promotion to

brigadier general

Brigadier general or Brigade general is a military rank used in many countries. It is the lowest ranking general officer in some countries. The rank is usually above a colonel, and below a major general or divisional general. When appointed ...

, effective June 25, 1864.

They rotated back to the trenches a few weeks later.

They remained engaged in the siege for the rest of the year and into early 1865. On July 30, a Union

sapper mine detonated explosives underneath the Confederate trench, resulting in a day of fighting in what's called the

Battle of the Crater.

On August 18, 1864, they were part of the successful Union raid, known as the

Battle of Globe Tavern

The Battle of Globe Tavern, also known as the Second Battle of the Weldon Railroad, fought August 18–21, 1864, south of Petersburg, Virginia, was the second attempt of the Union Army to sever the Weldon Railroad during the siege of Petersburg ...

, to cut the

Weldon Railroad and reduce the supply lines for the Petersburg defenders.

In October, there was another attempt, known as the

Battle of Boydton Plank Road

The Battle of the Boydton Plank Road (also known as Burgess Mill or First Hatcher's Run), fought on October 27–28, 1864, followed the successful Battle of Peebles's Farm in the siege of Petersburg during the American Civil War. It was a ...

, to sever another Confederate supply line, but the attack was withdrawn.

General Bragg's final battle of the war was the

Battle of Hatcher's Run, occurring February 6, 1865, near the site of the Battle of Boydton Plank Road.

The Iron Brigade took heavy casualties, and, following the battle, had to be significantly reorganized. General Bragg was summoned to Washington with four regiments and then sent to Baltimore to supervise transportation of

conscripts

Conscription (also called the draft in the United States) is the state-mandated enlistment of people in a national service, mainly a military service. Conscription dates back to antiquity and it continues in some countries to the present day und ...

. He remained in Baltimore until the end of the war.

He mustered out October 9, 1865.

Postbellum career

Following the war, Bragg returned to his legal practice in Fond du Lac.

Johnson appointments controversy

In 1866, General Bragg was appointed

postmaster of Fond du Lac by

President

President most commonly refers to:

*President (corporate title)

* President (education), a leader of a college or university

* President (government title)

President may also refer to:

Automobiles

* Nissan President, a 1966–2010 Japanese ...

Andrew Johnson. This occurred as tensions were beginning to rise between President Johnson and the

Radical Republican

The Radical Republicans (later also known as "Stalwarts") were a faction within the Republican Party, originating from the party's founding in 1854, some 6 years before the Civil War, until the Compromise of 1877, which effectively ended Recon ...

Congress. In February 1867, the Senate voted to rescind Bragg's appointment, along with several other Johnson appointments. Johnson subsequently nominated Bragg to be Assessor of

Internal Revenue

The Internal Revenue Service (IRS) is the revenue service for the United States federal government, which is responsible for collecting U.S. federal taxes and administering the Internal Revenue Code, the main body of the federal statutory tax ...

for the 4th district of Wisconsin, which the

United States Senate

The United States Senate is the upper chamber of the United States Congress, with the House of Representatives being the lower chamber. Together they compose the national bicameral legislature of the United States.

The composition and pow ...

also defeated.

Democratic minority

Later in 1867, General Bragg won election to the

Wisconsin State Senate

The Wisconsin Senate is the upper house of the Wisconsin State Legislature. Together with the larger Wisconsin State Assembly they constitute the legislative branch of the state of Wisconsin. The powers of the Wisconsin Senate are modeled after t ...

from the

20th senatorial district, serving in the

21st and

22nd Wisconsin Legislatures (1868 & 1869). He did not run for re-election in 1869, but remained extremely active in Democratic politics, campaigning for the Democratic tickets and running for office several times. He was mostly unsuccessful for the next several years, as Republican politics remained dominant in Wisconsin.

In 1868, Bragg was a member of the executive committee for the National Convention of "Conservative Soldiers and Sailors"—part of the

1868 Democratic National Convention in

New York City

New York, often called New York City or NYC, is the most populous city in the United States. With a 2020 population of 8,804,190 distributed over , New York City is also the most densely populated major city in the Un ...

. The Soldiers and Sailors convention favored the nomination of Major General

Winfield Scott Hancock

Winfield Scott Hancock (February 14, 1824 – February 9, 1886) was a United States Army officer and the Democratic nominee for President of the United States in 1880. He served with distinction in the Army for four decades, including service ...

for president, but were ultimately unsuccessful, as the convention nominated former New York Governor

Horatio Seymour

Horatio Seymour (May 31, 1810February 12, 1886) was an American politician. He served as Governor of New York from 1853 to 1854 and from 1863 to 1864. He was the Democratic Party nominee for president in the 1868 United States presidential elec ...

. Bragg campaigned vigorously for the Democratic ticket in the fall, though papers commented that he didn't seem to share the candidate's views on

African American suffrage. He was also a delegate to the

1872 Democratic National Convention, which nominated

Horace Greeley.

He was the Democratic nominee for

Attorney General of Wisconsin

The Attorney General of Wisconsin is a constitutional officer in the executive branch of the government of the U.S. state of Wisconsin. Forty-five individuals have held the office of Attorney General since statehood. The incumbent is Josh Kaul, ...

in 1871, but was defeated along with the entire Democratic ticket.

In the hotly contested

1875 United States senate election in the

Wisconsin Legislature

The Wisconsin Legislature is the state legislature of the U.S. state of Wisconsin. The Legislature is a bicameral body composed of the upper house, Wisconsin State Senate, and the lower Wisconsin State Assembly, both of which have had Republica ...

, Bragg was the choice of the Democratic caucus, believed to be a potential compromise candidate for the fourteen Republicans who had pledged to prevent the re-election of

Matthew H. Carpenter. However, after no candidate was able to obtain a majority through several ballots, a new compromise candidate emerged in

Angus Cameron. Cameron was ultimately elected on the 12th ballot.

In more local affairs, Bragg engaged in a years-long feud with Congressman

Charles A. Eldredge, who had defeated him running on an anti-war platform in the 1862 congressional election. In 1874, Bragg was successful in defeating Eldredge in local primaries and taking a slate of delegates to the district convention, preventing Eldredge's renomination. But the nomination ultimately went to

Samuel D. Burchard. Bragg came back two years later, however, and this time defeated Burchard in his attempt for renomination.

Congress

In November 1876, Bragg was elected to represent

Wisconsin's 5th congressional district

Wisconsin's 5th congressional district is a congressional district of the United States House of Representatives in Wisconsin, covering most of Milwaukee's northern and western suburbs. It presently covers all of Washington and Jefferson count ...

in the

45th United States Congress

The 45th United States Congress was a meeting of the legislative branch of the United States federal government, consisting of the United States Senate and the United States House of Representatives. It met in Washington, D.C. from March 4, 1877, ...

. Bragg would go on to win re-election in 1878 and 1880, but, after

redistricting in 1881, he was unable to win renomination in 1882.

During these six years in Congress, Bragg was chairman of the

Committee on Expenditures in the Department of Justice from 1877 to 1879 and of the

Committee on War Claims from 1879 to 1881. He was, again, a delegate to the

Democratic National Convention in 1880, which nominated General Winfield Scott Hancock.

After the 1880 census,

redistricting was carried out and Bragg's county, Fond du Lac, was moved from the 5th congressional district to the

2nd district. Bragg now found himself in an intense contest for renomination against

Arthur Delaney

Arthur McEvoy Delaney born 9 December 1927, Chorlton upon Medlock, Manchester, Lancashire - died 17 April 1987 (Manchester Royal Infirmary, Manchester) was an English painter whose scenes of Manchester life were influenced by those of L. S. L ...

of Dodge County. In the days before he would attend the convention in September, however, Bragg was arrested and accused of a financial fraud deriving from a transaction with the Tremont House institution in Chicago. Though the charges were eventually dropped, the controversy likely harmed his chances of renomination. At the convention, the vote deadlocked for hundreds of ballots with delegates for the two candidates unwilling to compromise. The matter was resolved when Bragg had to leave the convention to attend his daughter's wedding—a former ally,

Daniel H. Sumner, convinced a group of delegates to pick him as a compromise candidate on the 1,601st ballot. Bragg initially considered an independent bid, but decided against it, stating that he was retiring from politics.

While in Congress, Bragg had been one only 3 Democrats to vote against the

Chinese Exclusion Act of 1882

The Chinese Exclusion Act was a United States federal law signed by President Chester A. Arthur on May 6, 1882, prohibiting all immigration of Chinese laborers for 10 years. The law excluded merchants, teachers, students, travelers, and diplom ...

.

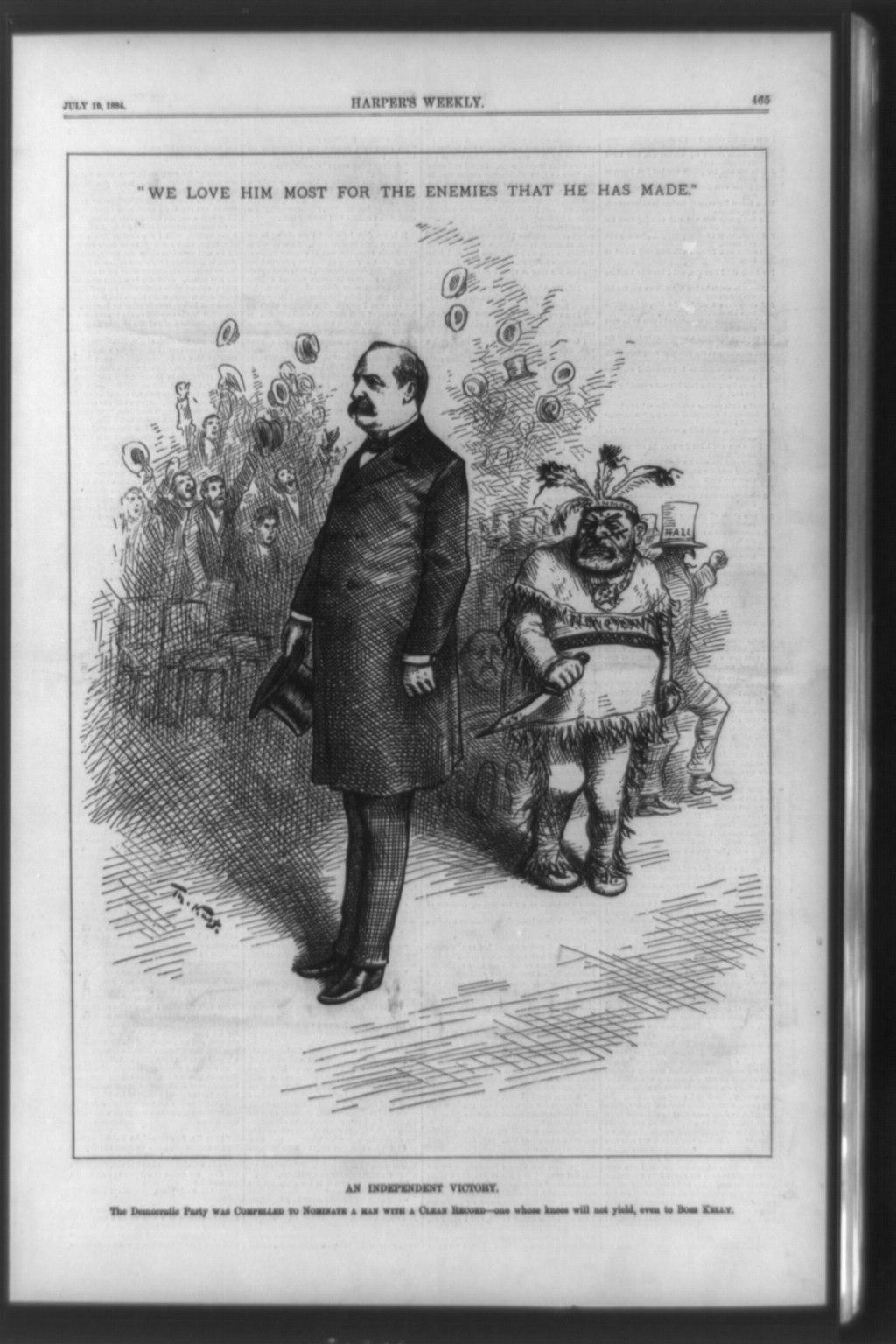

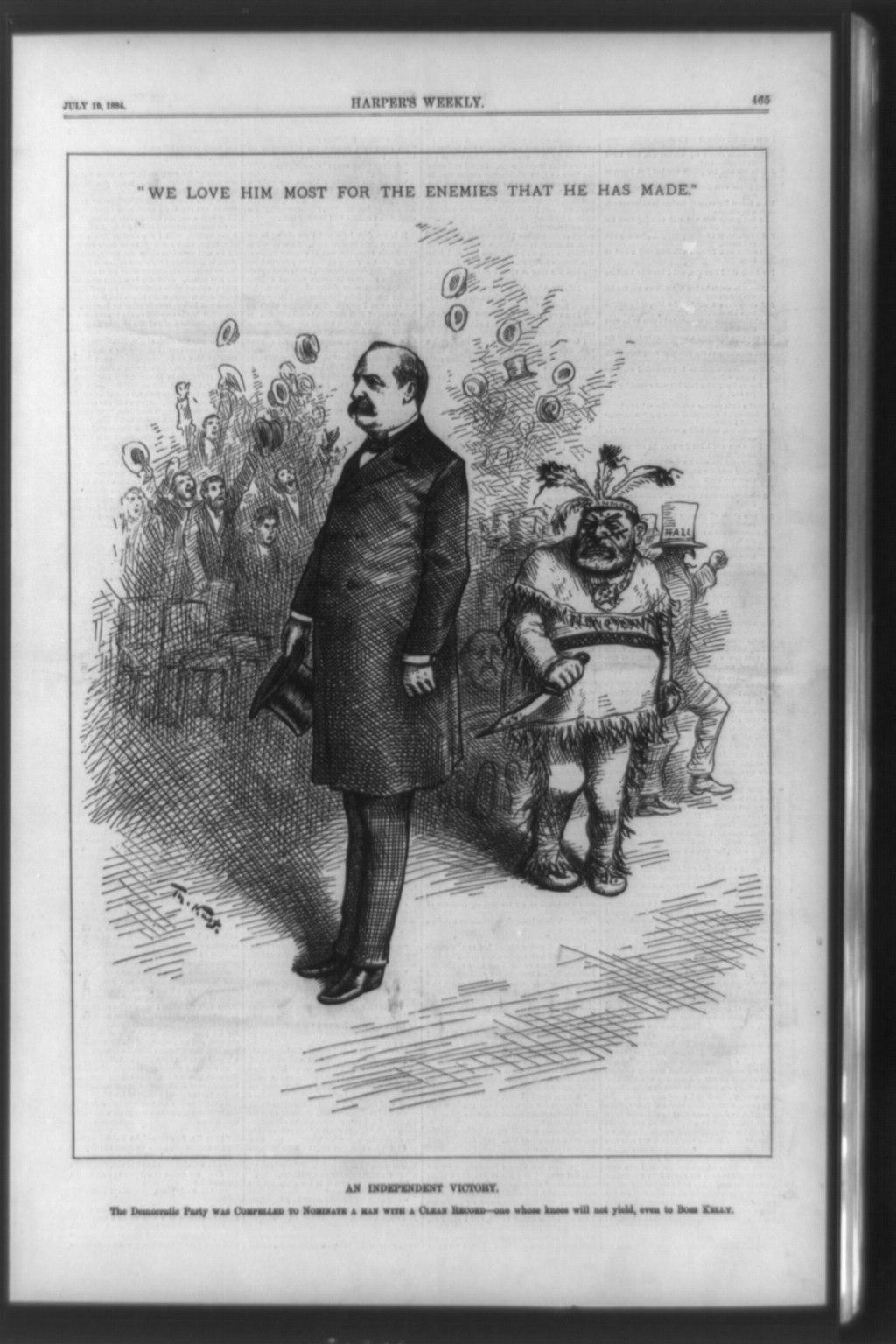

Nevertheless, General Bragg remained involved in state politics. In 1884, he was, again, a delegate to the

Democratic National Convention. At that convention, he seconded the nomination of

Grover Cleveland

Stephen Grover Cleveland (March 18, 1837June 24, 1908) was an American lawyer and politician who served as the 22nd and 24th president of the United States from 1885 to 1889 and from 1893 to 1897. Cleveland is the only president in American ...

for the presidency saying "We love him for the enemies he made."—referring to Cleveland's conflicts with the corrupt Tammany Hall organization. The phrase became a slogan for the Cleveland campaign and Cleveland was elected the 22nd

President of the United States

The president of the United States (POTUS) is the head of state and head of government of the United States of America. The president directs the executive branch of the federal government and is the commander-in-chief of the United States ...

that November.

That same fall, Bragg again pursued the Democratic nomination for Congress at the district convention, held at

Beaver Dam, Wisconsin

Beaver Dam is a city in Dodge County, Wisconsin, United States, along Beaver Dam Lake and the Beaver Dam River. The population was 16,708 at the 2020 census, making it the largest city primarily located in Dodge County. It is the principal city ...

, in September. Daniel Sumner was seeking renomination, Arthur Delaney was again a chief rival, with Judge Hiram W. Sawyer of Washington County also in the race. The balloting again deadlocked with no candidate able to secure the majority. Finally, before the 150th ballot, Sawyer and Sumner withdrew from the contest, allowing Bragg to win the nomination in a 15–13 vote over Delaney.

Bragg won the November general election with 55% over Republican Samuel S. Barney.

During the 49th United States Congress (1885–1887) Bragg was chairman of the United States House Committee on Armed Services, Committee on Military Affairs.

In 1886, Bragg again faced a contested convention when seeking renomination. Delaney was his chief rival, again, and, once again, a bitter and lengthy convention fight ensued. On the 216th ballot, Delaney was finally able to secure the nomination from Bragg. Delaney, however, went on to defeat in the general election.

Split with Democrats

Bragg resumed his law practice in Fond du Lac, Wisconsin, but returned to public office in January 1888, when he was appointed List of ambassadors of the United States to Mexico, United States Minister (Ambassador) to Mexico by President Grover Cleveland. He served in the role until his successor was appointed and confirmed, in May 1889, under the administration of President Benjamin Harrison.

As a diplomat, Bragg was said to have formed a good rapport with Mexican President Porfirio Díaz, and was fond of the country and his time there. In 1893, when President Cleveland returned to office, Bragg solicited a re-appointment to the post. Despite strong backing from the Wisconsin congressional delegation in 1893—and when the seat became open again in 1895—Cleveland did not reappoint General Bragg, in what was taken as a snub.

After returning from Mexico in 1889, Bragg again returned to his legal career and state politics. In 1890 he was organizing for another attempt at election to the United States Senate, but ultimately made a deal with William Freeman Vilas, whereby Bragg would support Vilas in 1891 and would, in turn, have the support of Vilas in the 1892 and 1893 United States Senate elections, 1893 senate election, assuming Democrats still held a majority in the Wisconsin Legislature at that time. This consideration also likely influenced his decision to become involved in the famous Redistricting in Wisconsin#Cunningham cases (1892), Cunningham gerrymandering cases of 1892, in which he advocated against a challenge to the Democrats' 1891

redistricting law

1891 Wis. Act 482 before the Wisconsin Supreme Court. The Court, however, in a bipartisan opinion, sided with the challengers and the district map was struck down as an unconstitutional partisan gerrymandering, gerrymander.

Despite the court loss, Democrats won massive majorities in the Wisconsin Legislature in the 1892 elections, but Bragg did not ultimately benefit from it in the senatorial election. The Democratic caucus deadlocked in a three-way race between Bragg, John H. Knight (politician), John H. Knight of Ashland, and John L. Mitchell of Milwaukee. On the 31st ballot, the Knight delegation broke in favor of Mitchell. Bragg's supporters saw it as a betrayal by Vilas, who was seen as a supporter of Mitchell. Subsequently, at the 1894 Democratic state convention, Bragg was favored for the nomination for Governor, but refused nomination.

In 1896, Bragg was once again one of the leaders of the Wisconsin delegation to that year's 1896 Democratic National Convention, Democratic National Convention in Chicago. Bragg, however, was deeply bothered by the nomination of William Jennings Bryan and the ascendance of the "populist fanatics."

Bragg threatened to vote for the Republican, William McKinley. He became one of the leaders of a Democratic schism, called the National Democratic Party (United States), National Democratic Party, and was a candidate for president at its convention in Indianapolis in September. McKinley went on to win the election, 1896 United States presidential election in Wisconsin, carrying Wisconsin by roughly the exact margin Bragg had predicted—100,000 votes.

The schism would prove permanent for Bragg, who supported McKinley for re-election in 1900 United States presidential election, 1900, as well as state Republicans, such as gubernatorial candidates Edward Scofield in 1898 and Robert M. La Follette in 1900. In May 1902, President

Theodore Roosevelt

Theodore Roosevelt Jr. ( ; October 27, 1858 – January 6, 1919), often referred to as Teddy or by his initials, T. R., was an American politician, statesman, soldier, conservationist, naturalist, historian, and writer who served as the 26t ...

appointed him consul general in Havana, Havana, Cuba, which had recently ratified their U.S.-backed constitution. But he was unhappy with the assignment, so, in September 1902, he was reassigned to British Hong Kong, Hong Kong, then a British crown colony, serving until 1906.

Family

Bragg married Cornelia Colman on January 2, 1854. Cornelia was a granddaughter of Colonel Nathaniel Rochester, who was the namesake and one of the founders of Rochester, New York. They had three sons and three daughters, though two of their sons died in childhood. Their youngest daughter, Bertha, married George P. Scriven, George Percival Scriven, who would go on to become the first chairman of the National Advisory Committee for Aeronautics, the forerunner of NASA.

Bragg was a cousin of Frederick Benteen, Frederick William Benteen, a senior captain (brevet brigadier-general) of the U.S. 7th Cavalry under George Armstrong Custer. Benteen was a major figure in the ill-fated Battle of the Little Bighorn and was singled out by Major Marcus Reno for his leadership during the two days of fighting endured by the survivors. Benteen mentioned his relationship to Bragg in a letter to Theodore Goldin dated February 10, 1896 (Benteen-Goldin Letters, Carroll, 1974).

He was also a cousin of Confederate Army General Braxton Bragg.

Though the two Braggs were both major participants in the prosecution of the Civil War, they never met in battle.

General Bragg suffered a paralytic stroke on June 19, 1912, and died the next day at his home in Fond du Lac, Wisconsin.

He was interred at Fond du Lac's Rienzi Cemetery.

Electoral history

U.S. House of Representatives (1862)

, colspan="6" style="text-align:center;background-color: #e9e9e9;", General Election, November 4, 1862

U.S. Senate (1867)

, colspan="6" style="text-align:center;background-color: #e9e9e9;", Vote of the 20th Wisconsin Legislature, January 23, 1867

Wisconsin State Senate (1867)

Wisconsin Attorney General (1871)

, colspan="6" style="text-align:center;background-color: #e9e9e9;", General Election, November 7, 1871

U.S. House of Representatives (1876, 1878, 1880)

, colspan="6" style="text-align:center;background-color: #e9e9e9;", General Election, November 7, 1876

, colspan="6" style="text-align:center;background-color: #e9e9e9;", General Election, November 5, 1878

, colspan="6" style="text-align:center;background-color: #e9e9e9;", General Election, November 5, 1878

U.S. House of Representatives (1884)

, colspan="6" style="text-align:center;background-color: #e9e9e9;", General Election, November 4, 1884

See also

*List of American Civil War generals (Union)

References

Notes

Further reading

*

*

*

*

*

*

*

External links

* Retrieved on 2008-01-06

*

Bragg, Gen. Edward Stuyvesant (1827-1912)at Wisconsin Historical Society

{{DEFAULTSORT:Bragg, Edward S.

1827 births

1912 deaths

Democratic Party Wisconsin state senators

Ambassadors of the United States to Mexico

Wisconsin postmasters

District attorneys in Wisconsin

New York (state) lawyers

Union Army generals

Hobart and William Smith Colleges alumni

Politicians from Fond du Lac, Wisconsin

People from Unadilla, New York

People of Wisconsin in the American Civil War

Military personnel from Wisconsin

Iron Brigade

19th-century American diplomats

Democratic Party members of the United States House of Representatives from Wisconsin

19th-century American politicians

Consul General of the United States in Hong Kong and Macau

19th-century American lawyers

The fighting at Gainesville is often referred to in historical documents as the "Battle of Gainesville" and represented the first day of fighting in the Second Battle of Bull Run. Despite being outnumbered by more than 3-to-1, the brigade held their ground and the fighting ended indecisively around midnight. This is where the nickname "Iron Brigade" was first applied to their unit.

Bragg and the Iron Brigade were resting and remained in reserve during the second day of battle, but rejoined the fighting on the third day, August 30, 1862, in support of

The fighting at Gainesville is often referred to in historical documents as the "Battle of Gainesville" and represented the first day of fighting in the Second Battle of Bull Run. Despite being outnumbered by more than 3-to-1, the brigade held their ground and the fighting ended indecisively around midnight. This is where the nickname "Iron Brigade" was first applied to their unit.

Bragg and the Iron Brigade were resting and remained in reserve during the second day of battle, but rejoined the fighting on the third day, August 30, 1862, in support of  At the

At the  On June 12, they made another sudden evacuation of their position and crossed the James River, engaging the

On June 12, they made another sudden evacuation of their position and crossed the James River, engaging the  Nevertheless, General Bragg remained involved in state politics. In 1884, he was, again, a delegate to the Democratic National Convention. At that convention, he seconded the nomination of

Nevertheless, General Bragg remained involved in state politics. In 1884, he was, again, a delegate to the Democratic National Convention. At that convention, he seconded the nomination of  Bragg married Cornelia Colman on January 2, 1854. Cornelia was a granddaughter of Colonel Nathaniel Rochester, who was the namesake and one of the founders of Rochester, New York. They had three sons and three daughters, though two of their sons died in childhood. Their youngest daughter, Bertha, married George P. Scriven, George Percival Scriven, who would go on to become the first chairman of the National Advisory Committee for Aeronautics, the forerunner of NASA.

Bragg was a cousin of Frederick Benteen, Frederick William Benteen, a senior captain (brevet brigadier-general) of the U.S. 7th Cavalry under George Armstrong Custer. Benteen was a major figure in the ill-fated Battle of the Little Bighorn and was singled out by Major Marcus Reno for his leadership during the two days of fighting endured by the survivors. Benteen mentioned his relationship to Bragg in a letter to Theodore Goldin dated February 10, 1896 (Benteen-Goldin Letters, Carroll, 1974).

He was also a cousin of Confederate Army General Braxton Bragg. Though the two Braggs were both major participants in the prosecution of the Civil War, they never met in battle.

General Bragg suffered a paralytic stroke on June 19, 1912, and died the next day at his home in Fond du Lac, Wisconsin. He was interred at Fond du Lac's Rienzi Cemetery.

Bragg married Cornelia Colman on January 2, 1854. Cornelia was a granddaughter of Colonel Nathaniel Rochester, who was the namesake and one of the founders of Rochester, New York. They had three sons and three daughters, though two of their sons died in childhood. Their youngest daughter, Bertha, married George P. Scriven, George Percival Scriven, who would go on to become the first chairman of the National Advisory Committee for Aeronautics, the forerunner of NASA.

Bragg was a cousin of Frederick Benteen, Frederick William Benteen, a senior captain (brevet brigadier-general) of the U.S. 7th Cavalry under George Armstrong Custer. Benteen was a major figure in the ill-fated Battle of the Little Bighorn and was singled out by Major Marcus Reno for his leadership during the two days of fighting endured by the survivors. Benteen mentioned his relationship to Bragg in a letter to Theodore Goldin dated February 10, 1896 (Benteen-Goldin Letters, Carroll, 1974).

He was also a cousin of Confederate Army General Braxton Bragg. Though the two Braggs were both major participants in the prosecution of the Civil War, they never met in battle.

General Bragg suffered a paralytic stroke on June 19, 1912, and died the next day at his home in Fond du Lac, Wisconsin. He was interred at Fond du Lac's Rienzi Cemetery.