Edred of England on:

[Wikipedia]

[Google]

[Amazon]

Eadred (c. 923 – 23 November 955) was

Like Edmund, Eadred inherited the whole English kingdom, but soon lost Northumbria and had to fight to get it back. The situation was complicated due to the number of rival factions in Northumbria. The Viking

Like Edmund, Eadred inherited the whole English kingdom, but soon lost Northumbria and had to fight to get it back. The situation was complicated due to the number of rival factions in Northumbria. The Viking

The major religious movement of the tenth century, the

The major religious movement of the tenth century, the

Eadred's will is one of only two wills of Anglo-Saxon kings to survive. It reads:

:''In nomine Domini''. This is King Eadred's will. In the first place, he presents to the foundation wherein he desires that his body shall rest, two gold crosses and two swords with hilts of gold, and four hundred pounds. Item, he gives to the Old Minster at Winchester three estates, namely Downton, Damerham and

Eadred's will is one of only two wills of Anglo-Saxon kings to survive. It reads:

:''In nomine Domini''. This is King Eadred's will. In the first place, he presents to the foundation wherein he desires that his body shall rest, two gold crosses and two swords with hilts of gold, and four hundred pounds. Item, he gives to the Old Minster at Winchester three estates, namely Downton, Damerham and

King of the English

This list of kings and reigning queens of the Kingdom of England begins with Alfred the Great, who initially ruled Wessex, one of the seven Anglo-Saxon kingdoms which later made up modern England. Alfred styled himself King of the Anglo-Sa ...

from 26 May 946 until his death. He was the younger son of Edward the Elder

Edward the Elder (17 July 924) was King of the Anglo-Saxons from 899 until his death in 924. He was the elder son of Alfred the Great and his wife Ealhswith. When Edward succeeded to the throne, he had to defeat a challenge from his cousin ...

and his third wife Eadgifu, and a grandson of Alfred the Great

Alfred the Great (alt. Ælfred 848/849 – 26 October 899) was King of the West Saxons from 871 to 886, and King of the Anglo-Saxons from 886 until his death in 899. He was the youngest son of King Æthelwulf and his first wife Osburh, who bo ...

. His elder brother, Edmund

Edmund is a masculine given name or surname in the English language. The name is derived from the Old English elements ''ēad'', meaning "prosperity" or "riches", and ''mund'', meaning "protector".

Persons named Edmund include:

People Kings an ...

, was killed trying to protect his seneschal

The word ''seneschal'' () can have several different meanings, all of which reflect certain types of supervising or administering in a historic context. Most commonly, a seneschal was a senior position filled by a court appointment within a royal, ...

from an attack by a violent thief. Edmund's two sons, Eadwig

Eadwig (also Edwy or Eadwig All-Fair, 1 October 959) was King of England from 23 November 955 until his death in 959. He was the elder son of Edmund I and his first wife Ælfgifu, who died in 944. Eadwig and his brother Edgar were young ...

and Edgar

Edgar is a commonly used English given name, from an Anglo-Saxon name ''Eadgar'' (composed of '' ead'' "rich, prosperous" and '' gar'' "spear").

Like most Anglo-Saxon names, it fell out of use by the later medieval period; it was, however, r ...

, were then young children, so Eadred became king. He suffered from ill health in the last years of his life and he died at the age of a little over thirty, having never married. He was succeeded successively by his nephews, Eadwig and Edgar.

Eadred's elder half-brother Æthelstan

Æthelstan or Athelstan (; ang, Æðelstān ; on, Aðalsteinn; ; – 27 October 939) was King of the Anglo-Saxons from 924 to 927 and King of the English from 927 to his death in 939. He was the son of King Edward the Elder and his fir ...

inherited the kingship of England south of the Humber

The Humber is a large tidal estuary on the east coast of Northern England. It is formed at Trent Falls, Faxfleet, by the confluence of the tidal rivers Ouse and Trent. From there to the North Sea, it forms part of the boundary between ...

in 924, and conquered the south Northumbrian Viking kingdom of York in 927. Edmund and Eadred both inherited kingship of the whole kingdom, lost it shortly afterwards when York accepted Viking kings, and recovered it by the end of their reigns. In 954 the York magnates expelled their last king, Erik Bloodaxe

Eric Haraldsson ( non, Eiríkr Haraldsson , no, Eirik Haraldsson; died 954), nicknamed Bloodaxe ( non, blóðøx , no, Blodøks) and Brother-Slayer ( la, fratrum interfector), was a 10th-century Norwegian king. He ruled as King of Norway from ...

, and Eadred appointed Osullf, the Anglo-Saxon ruler of the north Northumbrian territory of Bamburgh

Bamburgh ( ) is a village and civil parish on the coast of Northumberland, England. It had a population of 454 in 2001, decreasing to 414 at the 2011 census.

The village is notable for the nearby Bamburgh Castle, a castle which was the seat o ...

, as the first ealdorman

Ealdorman (, ) was a term in Anglo-Saxon England which originally applied to a man of high status, including some of royal birth, whose authority was independent of the king. It evolved in meaning and in the eighth century was sometimes applied ...

of the whole of Northumbria

la, Regnum Northanhymbrorum

, conventional_long_name = Kingdom of Northumbria

, common_name = Northumbria

, status = State

, status_text = Unified Anglian kingdom (before 876)North: Anglian kingdom (af ...

.

Eadred had been very close to Edmund and inherited many of his leading advisers, such as his mother Eadgifu, Oda, Archbishop of Canterbury

Oda (or Odo; died 958), called the Good or the Severe, was a 10th-century Archbishop of Canterbury in England. The son of a Danish invader, Oda became Bishop of Ramsbury before 928. A number of stories were told about his actions both prior to ...

, and Æthelstan

Æthelstan or Athelstan (; ang, Æðelstān ; on, Aðalsteinn; ; – 27 October 939) was King of the Anglo-Saxons from 924 to 927 and King of the English from 927 to his death in 939. He was the son of King Edward the Elder and his fir ...

, ealdorman of East Anglia

East Anglia is an area in the East of England, often defined as including the counties of Norfolk, Suffolk and Cambridgeshire. The name derives from the Anglo-Saxon kingdom of the East Angles, a people whose name originated in Anglia, in ...

, who was so powerful that he was known as the 'Half-King'. Dunstan

Saint Dunstan (c. 909 – 19 May 988) was an English bishop. He was successively Abbot of Glastonbury Abbey, Bishop of Worcester, Bishop of London and Archbishop of Canterbury, later canonised as a saint. His work restored monastic life in ...

, Abbot of Glastonbury

Glastonbury (, ) is a town and civil parish in Somerset, England, situated at a dry point on the low-lying Somerset Levels, south of Bristol. The town, which is in the Mendip district, had a population of 8,932 in the 2011 census. Glastonbur ...

and future Archbishop of Canterbury

The archbishop of Canterbury is the senior bishop and a principal leader of the Church of England, the ceremonial head of the worldwide Anglican Communion and the diocesan bishop of the Diocese of Canterbury. The current archbishop is Just ...

, was a close friend and adviser, and Eadred appears to have authorised Dunstan to draft charter

A charter is the grant of authority or rights, stating that the granter formally recognizes the prerogative of the recipient to exercise the rights specified. It is implicit that the granter retains superiority (or sovereignty), and that the re ...

s when he became too ill to attend meetings of the ''witan

The Witan () was the king's council in Anglo-Saxon England from before the seventh century until the 11th century. It was composed of the leading magnates, both ecclesiastic and secular, and meetings of the council were sometimes called the Wit ...

'' (King's Council) in his last years.

The English Benedictine Reform

The English Benedictine Reform or Monastic Reform of the English church in the late tenth century was a religious and intellectual movement in the later Anglo-Saxon period. In the mid-tenth century almost all monasteries were staffed by secular ...

did not reach fruition until the reign of Edgar, but Eadred was a strong supporter in its early stages. He was close to two of its leaders, Æthelwold, whom he appointed Abbot of Abingdon, and Dunstan. However, like earlier kings he did not share the view of the circle around Æthelwold that Benedictine monasticism was the only worthwhile religious life and he appointed Ælfsige

Ælfsige (or Aelfsige, Ælfsin or Aelfsin; died 959) was Bishop of Winchester before he became Archbishop of Canterbury in 959.

Life

Ælfsige became Bishop of Winchester in 951.Fryde, et al. ''Handbook of British Chronology'' p. 223 In 958, wi ...

, a married man with a son, as Bishop of Winchester

The Bishop of Winchester is the diocesan bishop of the Diocese of Winchester in the Church of England. The bishop's seat (''cathedra'') is at Winchester Cathedral in Hampshire. The Bishop of Winchester has always held ''ex officio'' (except ...

.

Background

In the ninth century the four Anglo-Saxon kingdoms ofWessex

la, Regnum Occidentalium Saxonum

, conventional_long_name = Kingdom of the West Saxons

, common_name = Wessex

, image_map = Southern British Isles 9th century.svg

, map_caption = S ...

, Mercia

la, Merciorum regnum

, conventional_long_name=Kingdom of Mercia

, common_name=Mercia

, status=Kingdom

, status_text=Independent kingdom (527–879)Client state of Wessex ()

, life_span=527–918

, era=Heptarchy

, event_start=

, date_start=

, y ...

, Northumbria

la, Regnum Northanhymbrorum

, conventional_long_name = Kingdom of Northumbria

, common_name = Northumbria

, status = State

, status_text = Unified Anglian kingdom (before 876)North: Anglian kingdom (af ...

and East Anglia

East Anglia is an area in the East of England, often defined as including the counties of Norfolk, Suffolk and Cambridgeshire. The name derives from the Anglo-Saxon kingdom of the East Angles, a people whose name originated in Anglia, in ...

came under increasing attack from Viking

Vikings ; non, víkingr is the modern name given to seafaring people originally from Scandinavia (present-day Denmark, Norway and Sweden),

who from the late 8th to the late 11th centuries raided, pirated, traded and se ...

raids, culminating in invasion by the Danish Viking Great Heathen Army

The Great Heathen Army,; da, Store Hedenske Hær also known as the Viking Great Army,Hadley. "The Winter Camp of the Viking Great Army, AD 872–3, Torksey, Lincolnshire", ''Antiquaries Journal''. 96, pp. 23–67 was a coalition of Scandin ...

in 865. By 878, they had overrun East Anglia, Northumbria, and Mercia, and nearly conquered Wessex, but in that year the West Saxons fought back under Alfred the Great

Alfred the Great (alt. Ælfred 848/849 – 26 October 899) was King of the West Saxons from 871 to 886, and King of the Anglo-Saxons from 886 until his death in 899. He was the youngest son of King Æthelwulf and his first wife Osburh, who bo ...

and achieved a decisive victory at the Battle of Edington

At the Battle of Edington, an army of the kingdom of Wessex under Alfred the Great defeated the Great Heathen Army led by the Dane Guthrum on a date between 6 and 12 May 878, resulting in the Treaty of Wedmore later the same year. Primary ...

. In the 880s and 890s the Anglo-Saxons ruled Wessex and western Mercia, but the rest of England was under Viking rule. Alfred constructed a network of burh

A burh () or burg was an Old English fortification or fortified settlement. In the 9th century, raids and invasions by Vikings prompted Alfred the Great to develop a network of burhs and roads to use against such attackers. Some were new const ...

s (fortified sites), and these helped him to frustrate renewed Viking attacks in the 890s with the assistance of his son-in-law, Æthelred, Lord of the Mercians

Æthelred, Lord of the Mercians (or Ealdorman Æthelred of Mercia; died 911) became ruler of English Mercia shortly after the death or disappearance of its last king, Ceolwulf II in 879. Æthelred's rule was confined to the western half, as ea ...

, and his elder son Edward

Edward is an English given name. It is derived from the Anglo-Saxon name ''Ēadweard'', composed of the elements '' ēad'' "wealth, fortune; prosperous" and '' weard'' "guardian, protector”.

History

The name Edward was very popular in Anglo-Sax ...

, who became king when Alfred died in 899. In 909 Edward sent a force of West Saxons and Mercians to attack the Northumbrian Danes and the following year the Vikings retaliated with a raid on Mercia. While they were marching back to Northumbria, they were caught by an Anglo-Saxon army and decisively defeated at the Battle of Tettenhall, ending the threat from the Northumbrian Vikings for a generation. In the 910s Edward and Æthelflæd

Æthelflæd, Lady of the Mercians ( 870 – 12 June 918) ruled Mercia in the English Midlands from 911 until her death. She was the eldest daughter of Alfred the Great, king of the Anglo-Saxon kingdom of Wessex, and his wife Ealhswith.

Æthe ...

– his sister and Æthelred's widow – extended Alfred's network of fortresses and conquered Viking-ruled eastern Mercia and East Anglia. When Edward died in 924, he controlled all England south of the Humber

The Humber is a large tidal estuary on the east coast of Northern England. It is formed at Trent Falls, Faxfleet, by the confluence of the tidal rivers Ouse and Trent. From there to the North Sea, it forms part of the boundary between ...

.

Edward was succeeded by his eldest son Æthelstan

Æthelstan or Athelstan (; ang, Æðelstān ; on, Aðalsteinn; ; – 27 October 939) was King of the Anglo-Saxons from 924 to 927 and King of the English from 927 to his death in 939. He was the son of King Edward the Elder and his fir ...

, who seized control of Northumbria in 927, thus becoming the first king of all England. Soon afterwards Welsh kings and the kings of Scotland

Scotland (, ) is a country that is part of the United Kingdom. Covering the northern third of the island of Great Britain, mainland Scotland has a border with England to the southeast and is otherwise surrounded by the Atlantic Ocean to ...

and Strathclyde

Strathclyde ( in Gaelic, meaning "strath (valley) of the River Clyde") was one of nine former local government regions of Scotland created in 1975 by the Local Government (Scotland) Act 1973 and abolished in 1996 by the Local Government et ...

acknowledged his overlordship. After this, he styled himself in charters

A charter is the grant of authority or rights, stating that the granter formally recognizes the prerogative of the recipient to exercise the rights specified. It is implicit that the granter retains superiority (or sovereignty), and that the rec ...

by titles such as "king of the English", or grandiosely, "king of the whole of Britain". In 934 he invaded Scotland and in 937 an alliance of armies of Scotland, Strathclyde and the Vikings invaded England. Æthelstan secured a decisive victory at the Battle of Brunanburh

The Battle of Brunanburh was fought in 937 between Æthelstan, King of England, and an alliance of Olaf Guthfrithson, King of Dublin, Constantine II, King of Scotland, and Owain, King of Strathclyde. The battle is often cited as the poin ...

, cementing his dominant position in Britain. Æthelstan died in October 939 and he was succeeded by his half-brother and Eadred's full brother Edmund

Edmund is a masculine given name or surname in the English language. The name is derived from the Old English elements ''ēad'', meaning "prosperity" or "riches", and ''mund'', meaning "protector".

Persons named Edmund include:

People Kings an ...

. He was the first king to succeed to the throne of all England but he soon lost control of the north. By the end of the year Anlaf Guthfrithson

Olaf Guthfrithson or Anlaf Guthfrithson ( non, Óláfr Guðrøðsson ; oe, Ánláf; sga, Amlaíb mac Gofraid; died 941) was a Hiberno-Scandinavian (Irish-Viking) leader who ruled Dublin and Viking Northumbria in the 10th century. He was t ...

, the Viking king of Dublin, had crossed the sea to become king of York. He also invaded Mercia and Edmund was forced to surrender the Five Boroughs

5 is a number, numeral, and glyph.

5, five or number 5 may also refer to:

* AD 5, the fifth year of the AD era

* 5 BC, the fifth year before the AD era

Literature

* ''5'' (visual novel), a 2008 visual novel by Ram

* ''5'' (comics), an awa ...

of north-east Mercia to him. Guthfrithson died in 941 and in 942 Edmund was able to recover the Five Boroughs. In 944 he recovered full control of England by expelling the Viking kings of York. On 26 May 946 he was stabbed to death trying to protect his seneschal

The word ''seneschal'' () can have several different meanings, all of which reflect certain types of supervising or administering in a historic context. Most commonly, a seneschal was a senior position filled by a court appointment within a royal, ...

from attack by a convicted outlaw at Pucklechurch

Pucklechurch is a large village and civil parish in South Gloucestershire, England. It has a current population of about 3000. The village dates back over a thousand years and was once the site of a royal hunting lodge, as it adjoined a large fo ...

in Gloucestershire

Gloucestershire ( abbreviated Glos) is a county in South West England. The county comprises part of the Cotswold Hills, part of the flat fertile valley of the River Severn and the entire Forest of Dean.

The county town is the city of ...

, and as his sons were young children Eadred became king.

Family and early life

Eadred's father, Edward the Elder, had three wives, eight or nine daughters, several of whom married Continental royalty, and five sons. Æthelstan, the son of Edward's first wife,Ecgwynn

Ecgwynn or Ecgwynna (Old English ''Eċġwynn'', lit. "sword joy"; ''fl''. 890s), was the first consort of Edward the Elder, later King of the English (reigned 899–924), by whom she bore the future King Æthelstan (r. 924–939), and a daughter ...

, was born around 894, but she probably died around the time of Alfred's death, as by 901 Edward was married to Ælfflæd Ælfflæd is a name of Anglo-Saxon England meaning Ælf (Elf) and flæd (beauty). It may refer to:

* Saint Ælfflæd of Whitby (654–714)

* Ælfflæd of Mercia, daughter of Offa, wife of King Æthelred I of Northumbria

* Ælfflæd, wife of Edward ...

. In about 919 he married Eadgifu, who had two sons, Edmund and Eadred. According to the twelfth-century chronicler William of Malmesbury

William of Malmesbury ( la, Willelmus Malmesbiriensis; ) was the foremost English historian of the 12th century. He has been ranked among the most talented English historians since Bede. Modern historian C. Warren Hollister described him as " ...

, Edmund was about eighteen years old when he succeeded to the throne in 939, which dates his birth to 920–921, and their father Edward died in 924, so Eadred was born around 923. He had one or two full sisters. Eadburh

Eadburh ( ang, Ēadburh), also spelled Eadburg, ( fl. 787–802) was the daughter of King Offa of Mercia and Queen Cynethryth. She was the wife of King Beorhtric of Wessex, and according to Asser's ''Life of Alfred the Great'' she killed her ...

was a nun at Winchester who was later venerated as a saint. William of Malmesbury gives Eadred a second full sister called Eadgifu like her mother, who married Louis, prince of Aquitaine. William's account is accepted by the historians Ann Williams and Sean Miller, but Æthelstan's biographer Sarah Foot

Sarah Rosamund Irvine Foot (born 23 February 1961) is an English Anglican priest and early medieval historian, currently serving as Regius Professor of Ecclesiastical History at the University of Oxford.

Early life and education

Foot was born ...

argues that she did not exist, and that William confused her with Ælfgifu, a daughter of Ælfflæd.

Eadred grew up with his brother at Æthelstan's court, and probably also with two important Continental exiles, his nephew Louis, future King of the West Franks, and Alain, future Duke of Brittany

This is a list of rulers of the Duchy of Brittany. In different epochs the sovereigns of Brittany were kings, princes, and dukes. The Breton ruler was sometimes elected, sometimes attained the position by conquest or intrigue, or by hereditary r ...

. According to William of Malmesbury, Æthelstan showed great affection towards Edmund and Eadred: "mere infants at his father's death, he brought them up lovingly in childhood, and when they grew up gave them a share in his kingdom". At a royal assembly shortly before Æthelstan's death in 939, Edmund and Eadred attested charter S 446, which granted land to their full sister, Eadburh. They both attested as ''regis frater'' (king's brother). This is the only charter of Æthelstan attested by Eadred.

Eadgifu and Eadred attested many of Edmund's charters, showing a high degree of family cooperation; initially Eadgifu attested first, but from sometime in late 943 or early 944 Eadred took precedence, perhaps reflecting his growing authority. Eadgifu attested around one third of Edmund's charters, always as ''regis mater'' (king's mother), including all grants to religious institutions and individuals. Eadred attested over half, and Pauline Stafford

Pauline Stafford is Professor Emerita of Early Medieval History at Liverpool University, and visiting professor at Leeds University in England. Dr Stafford is a former vice-president of the Royal Historical Society.

Scholarship

Her work focuses ...

comments: "No other adult male of the West Saxon house was ever given such prominence before his accession."

Reign

Battle for control of Northumbria

Anlaf Sihtricson

Olaf or Olav (, , or British ; Old Norse: ''Áleifr'', ''Ólafr'', ''Óleifr'', ''Anleifr'') is a Scandinavian and German given name. It is presumably of Proto-Norse origin, reconstructed as ''*Anu-laibaz'', from ''anu'' "ancestor, grand-father" a ...

(also called Olaf Sihtricson and Amlaib Cuaran) ruled Dublin

Dublin (; , or ) is the capital and largest city of Ireland. On a bay at the mouth of the River Liffey, it is in the province of Leinster, bordered on the south by the Dublin Mountains, a part of the Wicklow Mountains range. At the 2016 ...

and the southern Northumbrian kingdom of York at different periods. When king of York in the early 940s he had accepted baptism with Edmund as his godfather, indicating submission to his rule, and his coins followed English designs, but Edmund had expelled him in 944. Both Anlaf and the Norse (Norwegian) prince Erik Bloodaxe

Eric Haraldsson ( non, Eiríkr Haraldsson , no, Eirik Haraldsson; died 954), nicknamed Bloodaxe ( non, blóðøx , no, Blodøks) and Brother-Slayer ( la, fratrum interfector), was a 10th-century Norwegian king. He ruled as King of Norway from ...

ruled York for periods during Eadred's reign. Erik issued coins with a Viking sword design and represented a more serious threat to West Saxon power than Anlaf. The York magnates were key players, led by the powerful Wulfstan, Archbishop of York

The archbishop of York is a senior bishop in the Church of England, second only to the archbishop of Canterbury. The archbishop is the diocesan bishop of the Diocese of York and the metropolitan bishop of the province of York, which covers ...

, who periodically made bids for independence by accepting Viking kings, but submitted to southern rule at other times. In the view of the historian Marios Costambeys, Wulfstan's influence in Northumbria appears to have been greater than Erik's. Osulf, the Anglo-Saxon ruler of the north Northumbrian territory of Bamburgh

Bamburgh ( ) is a village and civil parish on the coast of Northumberland, England. It had a population of 454 in 2001, decreasing to 414 at the 2011 census.

The village is notable for the nearby Bamburgh Castle, a castle which was the seat o ...

, supported Eadred when it was in his own interest. The sequence of events is very unclear because different manuscripts of the ''Anglo-Saxon Chronicle'' contradict each other, and they also conflict with the evidence of charters, which are the only contemporary sources. Charters of 946, 949–50 and 955 call Eadred ruler of the Northumbrians, and these provide evidence of periods when York submitted to southern rule.

Following Edmund's death, Charter S 521 states that "it happened that Eadred, his uterine brother, aschosen in his stead by the nobles". According to the ''Anglo-Saxon Chronicle'', he immediately "reduced all Northumbria under his rule" and obtained promises of obedience from the Scots. He may have invaded Northumbria in response to a rebellion supported by the Scots. He was crowned by Archbishop Oda of Canterbury

Oda (or Odo; died 958), called the Good or the Severe, was a 10th-century Archbishop of Canterbury in England. The son of a Danish invader, Oda became Bishop of Ramsbury before 928. A number of stories were told about his actions both prior to ...

on 16 August 946 at Kingston upon Thames

Kingston upon Thames (hyphenated until 1965, colloquially known as Kingston) is a town in the Royal Borough of Kingston upon Thames, southwest London, England. It is situated on the River Thames and southwest of Charing Cross. It is notable as ...

, attended by Hywel Dda

Hywel Dda, sometimes anglicised as Howel the Good, or Hywel ap Cadell (died 949/950) was a king of Deheubarth who eventually came to rule most of Wales. He became the sole king of Seisyllwg in 920 and shortly thereafter established Deheubart ...

, king of Deheubarth

Deheubarth (; lit. "Right-hand Part", thus "the South") was a regional name for the realms of south Wales, particularly as opposed to Gwynedd (Latin: ''Venedotia''). It is now used as a shorthand for the various realms united under the House o ...

in south Wales, Wulfstan and Osulf. The following year at Tanshelf, near the border between Northumbria and Mercia, Wulfstan and the other York magnates pledged allegiance to him.

The York magnates soon reneged on their promises and accepted Erik as king. Eadred responded by leading an army to Ripon

Ripon () is a cathedral city in the Borough of Harrogate, North Yorkshire, England. The city is located at the confluence of two tributaries of the River Ure, the Laver and Skell. Historically part of the West Riding of Yorkshire, the ...

, where he burnt down the Minster, no doubt to punish Wulfstan, as it was at the centre of his richest estate. The Northumbrians sought revenge: according to version D of the ''Anglo-Saxon Chronicle'', "when the king was on his way home, the army (which) was in York overtook the king's army at Castleford

Castleford is a town within the City of Wakefield, West Yorkshire, England. It had a population of 45,106 at a 2021 population estimate. Historically in the West Riding of Yorkshire, to the north of the town centre the River Calder joins th ...

, and they made a great slaughter there. Then the king became so angry that he wished to march back into the land and destroy it utterly. When the councillors of the Northumbrians understood that, they deserted Erik and paid to King Eadred compensation for their act." Within a year or two they again changed sides and installed Anlaf Sihtricson as king. In 952 Eadred arrested Wulfstan and in the same year Erik displaced Anlaf, but in 954 the York magnates again threw out Erik and returned to English rule, this time not due to an invasion but by the choice of the northerners, and the change proved to be permanent. Erik was assassinated shortly afterwards, possibly at the instigation of Osulf, and the historian Frank Stenton

Sir Frank Merry Stenton, FBA (17 May 1880 – 15 September 1967) was an English historian of Anglo-Saxon England, and president of the Royal Historical Society (1937–1945).

The son of Henry Stenton of Southwell, Nottinghamshire, he was edu ...

comments that the time was past when an individual adventurer could establish a dynasty in England. Wulfstan was later released, probably in early 955, but he was apparently not allowed to resume his archbishopric and instead given the bishopric of Dorchester-on-Thames. Eadred then appointed Osulf as the first ealdorman of the whole of Northumbria. Osulf's position was probably so strong that the king had no choice but to appoint him, and it was not until the next century that southern kings were able to make their own choice of ealdormen in Bamburgh itself. In his will, Eadred left 1600 pounds to be used for protection of his people from famine or to buy peace from a heathen army, showing that he did not regard England as safe from attack.

Administration

Charters issued in the 930s and the 940s suggest continuity of royal government and smooth transitions between the reigns of Æthelstan, Edmund and Eadred. Eadred's principal councillors were mainly people he had inherited from his brother Edmund, and in a few cases went back to his half-brother Æthelstan. Oda, Archbishop of Canterbury, and Ealdorman Æthelstan of East Anglia, had been advisers of King Æthelstan who had become dominant under Edmund. Ealdorman Æthelstan's power under Edmund and Eadred was so great that he became known as Æthelstan Half-King. His prestige was further increased when his wifeÆlfwynn

__NOTOC__

Ælfwynn () was the ruler of Mercia as the 'Second Lady of the Mercians' for a few months in 918, following her mother's death on 12 June 918. She was the daughter of Æthelred and Æthelflæd, the rulers of Mercia. Her accession was ...

became foster-mother to Edmund's younger son Edgar following his mother's early death. The Half-King's brother Eadric was ealdorman of central Wessex, and Eadred granted him land in Sussex which Eadric gave to Abingdon Abbey

Abingdon Abbey ( '' " St Mary's Abbey " '' ) was a Benedictine monastery located in the centre of Abingdon-on-Thames beside the River Thames.

The abbey was founded c.675 AD in honour of The Virgin Mary.

The Domesday Book of 1086 informs ...

. Dunstan

Saint Dunstan (c. 909 – 19 May 988) was an English bishop. He was successively Abbot of Glastonbury Abbey, Bishop of Worcester, Bishop of London and Archbishop of Canterbury, later canonised as a saint. His work restored monastic life in ...

, the Abbot of Glastonbury __NOTOC__

The Abbot of Glastonbury was the head (or abbot) of Anglo-Saxon and eventually Benedictine house of Glastonbury Abbey at Glastonbury in Somerset, England.

The following is a list of abbots of Glastonbury:

Abbots

See also

* Abbot's K ...

and a future Archbishop of Canterbury

The archbishop of Canterbury is the senior bishop and a principal leader of the Church of England, the ceremonial head of the worldwide Anglican Communion and the diocesan bishop of the Diocese of Canterbury. The current archbishop is Just ...

, was one of Eadred's most trusted friends and advisers, and he attested many of Eadred's charters. Eadgifu had been sidelined under the rule of her stepson Æthelstan, but she became powerful under the rule of her own sons Edmund and Eadred. Ælfgar, the father of Edmund's second wife Æthelflæd

Æthelflæd, Lady of the Mercians ( 870 – 12 June 918) ruled Mercia in the English Midlands from 911 until her death. She was the eldest daughter of Alfred the Great, king of the Anglo-Saxon kingdom of Wessex, and his wife Ealhswith.

Æthe ...

, was ealdorman of Essex from 946 to 951. Edmund presented Ælfgar with a sword decorated with gold on its hilt and silver on its sheath, which Ælfgar subsequently gave to Eadred. Ælfgar consistently attested last among the ealdormen, and he may have been subordinate to Æthelstan Half-King. Two thegns, Wulfric Cufing and another Wulfric who was Dunstan's brother, received massive grants of land from Edmund and Eadred, showing that royal patronage could transform minor local figures into great nobles.

Eadred is one of the few later Anglo-Saxon kings for whom no law code is known to survive, although he may have issued the '' Hundred Ordinance''. Ealdormen issued legal judgments on behalf of the king at a local level. One example during Eadred's reign concerned the theft of a woman, probably a slave. A man called Æthelstan of Sunbury was later found to have her in his possession and could not prove he had acquired her legally. He surrendered possession and paid compensation to the owner, but Ealdorman Byrhtferth ordered him to pay his ''wer'' (the value of his life) to the king, and when Æthelstan could not pay Byrhtferth required him to forfeit his Sunbury estate. In 952 Eadred ordered "a great slaughter" of the people of Thetford

Thetford is a market town and civil parish in the Breckland District of Norfolk, England. It is on the A11 road between Norwich and London, just east of Thetford Forest. The civil parish, covering an area of , in 2015 had a population of 24, ...

in revenge for their murder of Abbot Eadhelm, perhaps of St Augustine's, Canterbury

St Augustine's Abbey was a Benedictine monastery in Canterbury, Kent, England. The abbey was founded in 598 and functioned as a monastery until its dissolution in 1538 during the English Reformation. After the abbey's dissolution, it underwent ...

. This was the usual punishment for crimes committed by communities. The historian Cyril Hart suggests that Eadhelm may have been trying to establish a new monastery there, against the opposition of the local inhabitants. Force was fundamental to West Saxon kings' domination of England, and the historian George Molyneaux sees the Thetford slaughter as an example of their "intermittently unleashed crude but terrifying displays of coercive power".

The Anglo-Saxon court was peripatetic, travelling round the country, and there was no fixed capital. Like other later Anglo-Saxon kings, Eadred's royal estates were mainly in Wessex and he and his court travelled between them. All known locations in Eadred's itinerary were in Wessex, apart from Tanshelf. There was also no central treasury, but Eadred did travel with his sacred relics, which were in the custody of his mass priests. According to Dunstan's first biographer, Eadred "handed over to Dunstan his most valuable possessions: many land charters, the old treasure of earlier kings, and various riches of his own acquiring, all to be guarded faithfully behind the walls of his monastery". However, Dunstan was only one of the people entrusted with Eadred's treasures; there were others such as Wulfhelm, Bishop of Wells

The Bishop of Bath and Wells heads the Church of England Diocese of Bath and Wells in the Province of Canterbury in England.

The present diocese covers the overwhelmingly greater part of the (ceremonial) county of Somerset and a small area of ...

. When Eadred was dying, he sent for the property so that he could distribute it, but he died before Dunstan arrived with his share. Ceremonial was important. A charter issued at Easter 949 describes Eadred as "exalted with royal crowns", displaying the king as an exceptional and charismatic character set apart from other men.

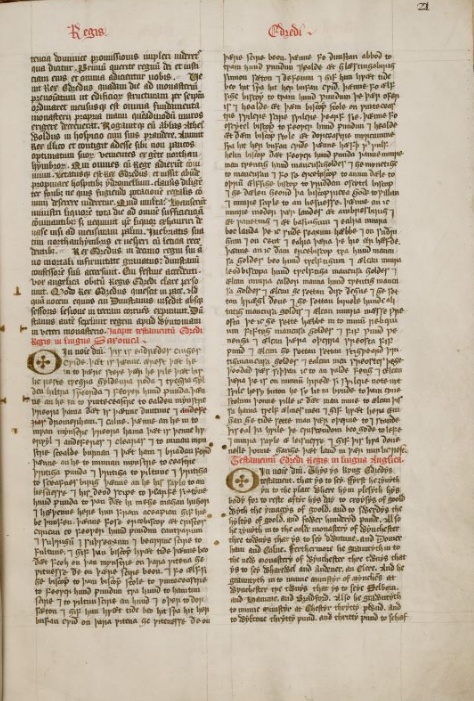

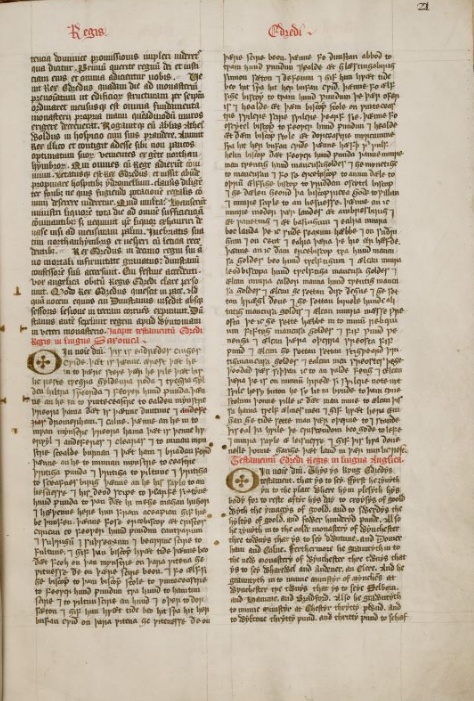

Charters

The period between 925 and 975 was the golden age of Anglo-Saxon royal diplomas, when they were at their peak as instruments of royal government, and kings used them to project images of royal power and as the most reliable means of communication between the court and the country. Most charters between late in Æthelstan's reign and midway through Eadred's were written in the king's writing office in a style called the "diplomatic mainstream", for example, the charter which is displayed below, written by the scribe called "Edmund C". He wrote two charters dating to Edmund's reign and three in Eadred's. The style almost disappears between around 950 and the end of Eadred's reign. The number of surviving charters declines, with none dating to the years 952 and 954. Charters from this period belong to two other traditions. The reason for the dramatic change in around 950 is not known, but may be due to Eadred transferring responsibility for charter production from the royal writing office to other centres when his health declined in his last years. One alternative tradition is found in the "alliterative charters", produced between 940 and 956, which display frequent use ofalliteration

Alliteration is the conspicuous repetition of initial consonant sounds of nearby words in a phrase, often used as a literary device. A familiar example is "Peter Piper picked a peck of pickled peppers". Alliteration is used poetically in various ...

and unusual vocabulary, in a style influenced by Aldhelm

Aldhelm ( ang, Ealdhelm, la, Aldhelmus Malmesberiensis) (c. 63925 May 709), Abbot of Malmesbury Abbey, Bishop of Sherborne, and a writer and scholar of Latin poetry, was born before the middle of the 7th century. He is said to have been the ...

, the seventh-century bishop of Sherborne

The Bishop of Sherborne is an episcopal title which takes its name from the market town of Sherborne in Dorset, England. The see of Sherborne was established in around 705 by St Aldhelm, the Abbot of Malmesbury. This see was the mother diocese of ...

. They are the work of a scribe who was very learned, almost certainly someone in the circle of Cenwald

Koenwald or Cenwald or Coenwald ( floruit 928–958) was an Anglo-Saxon Bishop of Worcester, probably of Mercian origin.

Life

Koenwald succeeded Bishop Wilfrith at some time between 16 April 928, when Wilfrith is last known to have witnessed a c ...

, bishop of Worcester

A bishop is an ordained clergy member who is entrusted with a position of authority and oversight in a religious institution.

In Christianity, bishops are normally responsible for the governance of dioceses. The role or office of bishop is ca ...

or perhaps the bishop himself. They have Mercian antecedents and most relate to estates north of the Thames. Seven charters of this type survive from 949 to 951, half the total for those years, and another two are dated 955. The historian Simon Keynes

Simon Douglas Keynes, ( ; born 23 September 1952) is a British author who is Elrington and Bosworth Professor of Anglo-Saxon emeritus in the Department of Anglo-Saxon, Norse, and Celtic at Cambridge University, and a Fellow of Trinity College ...

comments:

:The "alliterative" charters represent an extraordinary body of material, intimately related to each other, and deeply interesting in their own right as works of learning and literature. Judged as diplomas, they are inventive, spirited, and delightfully chaotic. They stand apart from the diplomatic mainstream, yet they seem nonetheless to emerge from the very heart of the ceremonies of conveyance conducted at royal assemblies.

The other alternative tradition is found in the "Dunstan B" charters, which are very different from the "alliterative" charters, with a style which is plain and unpretentious, and which dispenses with the usual initial invocation

An invocation (from the Latin verb ''invocare'' "to call on, invoke, to give") may take the form of:

*Supplication, prayer or spell.

*A form of possession.

*Command or conjuration.

* Self-identification with certain spirits.

These forms ...

and proem

__NOTOC__

A preface () or proem () is an introduction to a book or other literary work written by the work's author. An introductory essay written by a different person is a ''foreword'' and precedes an author's preface. The preface often closes ...

. They are associated with Dunstan and Glastonbury Abbey, and all the ones issued in Eadred's reign are for estates in the south and west. They were produced between 951 and 986, but they appear to be foreshadowed by a charter of 949 granting Reculver minster and its lands to Christ Church, Canterbury, which claims to be written by Dunstan "with his own fingers". The document is not original and is thought to be a production of the later tenth century, but there are no anachronisms and it has many stylistic features of the "Dunstan B" charters, so it is probably an "improved" version of an original charter. Further evidence associating Dunstan with the charters is provided by commentaries on a manuscript of Caesarius of Arles

Caesarius of Arles ( la, Caesarius Arelatensis; 468/470 27 August 542 AD), sometimes called "of Chalon" (''Cabillonensis'' or ''Cabellinensis'') from his birthplace Chalon-sur-Saône, was the foremost ecclesiastic of his generation in Merovingia ...

's ''Expositio in Apocalypsin'', written on Dunstan's order, which has a script so similar to that of the only "Dunstan B" charter to survive as an original manuscript that it is likely that both documents were written by Glastonbury scribes. The charter is described by Keynes as "well disciplined and thoroughly professional". Eight charters of all types survive dating to 953 and 955, out of which six belong to this tradition and two are "alliterative". The six "Dunstan B" charters are not witnessed by the king, and Dunstan was probably authorised to produce charters in the king's name when he was too ill to carry out his duties.

In the 940s the draftsmen of "mainstream" charters used the title "king of the English" and in the early 950s "Dunstan B" charters described Eadred as "king of Albion", whereas "alliterative" charters adopted complex political analysis in the wording of Eadred's title, and only after final conquest of York described him as "king of the whole of Britain". Several "alliterative" charters, including one issued on the occasion of Eadred's coronation, use expressions such as "the government of kingdoms of the Anglo-Saxons and Northumbrians, of the pagans and the Britons". Keynes observes: "It would be dangerous, of course, to press such evidence too far; but it is interesting nonetheless to be reminded that in the eyes of at least one observer the whole was no greater than the sum of its component parts.

Coinage

The only coin in common use in late Anglo-Saxon England was the silverpenny

A penny is a coin ( pennies) or a unit of currency (pl. pence) in various countries. Borrowed from the Carolingian denarius (hence its former abbreviation d.), it is usually the smallest denomination within a currency system. Presently, it is t ...

. Halfpennies were very rare but a few have been found dating to Eadred's reign, one of which has been cut in half to make a farthing. The average weight of a penny of around 24 grains

A grain is a small, hard, dry fruit (caryopsis) – with or without an attached hull layer – harvested for human or animal consumption. A grain crop is a grain-producing plant. The two main types of commercial grain crops are cereals and legumes ...

in Edward the Elder's reign gradually declined until Edgar's pre-reform coinage, and by Eadred's time the reduction was about 3 grains. With a few exceptions, the high silver content of 85 to 90% in previous reigns was maintained under Eadred.

One common coin type in Eadred's reign is designated BC (bust crowned), with the king's head on the obverse

Obverse and its opposite, reverse, refer to the two flat faces of coins and some other two-sided objects, including paper money, flags, seals, medals, drawings, old master prints and other works of art, and printed fabrics. In this usage, ...

. Many BC coins are based on an original style of Æthelstan's reign but are of crude workmanship. Some were produced by moneyers who had worked in the previous reign, but there were over thirty new moneyers producing BC coins, out of which nearly twenty are represented by a single coin, so it is likely that there were other moneyers producing BC coins whose coins have not yet been found.

The H (Horizontal) type, with no king's bust on the obverse and the moneyer's name horizontally on the reverse, was even more common, with more than eighty moneyers known for Eadred's reign, many only from single specimens. The dominant styles in Eadred's reign were HT1 in the south and east, with trefoil

A trefoil () is a graphic form composed of the outline of three overlapping rings, used in architecture and Christian symbolism, among other areas. The term is also applied to other symbols with a threefold shape. A similar shape with four ring ...

s top and bottom on the reverse (see right), and HR1 in the north midlands, with rosettes instead of trefoils, produced by around sixty moneyers and the most plentiful style in Eadred's reign.

In Northumbria and the north-east in Eadred's reign there were a few moneyers with a large output, whereas coins in the rest of the country were produced by many different moneyers. The mint town is shown on some BC coins, but rarely on H types. A few HRs show Derby and Chester, and one HT1 coin survives with an Oxford inscription and one with Canterbury. The leading York moneyer for almost the whole of Eadred's reign was Ingelgar (see right). He produced high standard coins for Eadred, Anlaf and Erik and worked until the last months of Eadred's reign, when he was replaced by Heriger. Another large scale moneyer was Hunred, who may have operated at Derby when York was in Viking hands.

Religion

The major religious movement of the tenth century, the

The major religious movement of the tenth century, the English Benedictine Reform

The English Benedictine Reform or Monastic Reform of the English church in the late tenth century was a religious and intellectual movement in the later Anglo-Saxon period. In the mid-tenth century almost all monasteries were staffed by secular ...

, reached its peak under Edgar, but Eadred was a strong supporter in its early stages. Another proponent was Archbishop Oda, who was a monk with a strong connection with the leading Continental centre, Fleury Abbey

Fleury Abbey (Floriacum) in Saint-Benoît-sur-Loire, Loiret, France, founded in about 640, is one of the most celebrated Benedictine monasteries of Western Europe, and possesses the relics of St. Benedict of Nursia. Its site on the banks of the ...

. When Eadred came to the throne, two of the future leaders of the movement were at Glastonbury Abbey

Glastonbury Abbey was a monastery in Glastonbury, Somerset, England. Its ruins, a grade I listed building and scheduled ancient monument, are open as a visitor attraction.

The abbey was founded in the 8th century and enlarged in the 10th. It w ...

: Dunstan had been appointed abbot by Edmund, and he had been joined by Æthelwold, the future Bishop of Winchester

The Bishop of Winchester is the diocesan bishop of the Diocese of Winchester in the Church of England. The bishop's seat (''cathedra'') is at Winchester Cathedral in Hampshire. The Bishop of Winchester has always held ''ex officio'' (except ...

. The reformers also had lay supporters such as Æthelstan Half-King and Eadgifu, who were especially close to Dunstan. The historian Nicholas Brooks comments: "The evidence is indirect and inadequate but may suggest that Dunstan drew much of his support from the regiment of powerful women in early tenth-century Wessex and from Eadgifu in particular." According to Dunstan's first biographer, Eadred urged Dunstan to accept the vacant see of Crediton, and when he refused Eadred got Eadgifu to invite Dunstan to a meal where she could use her "woman's gift of words" to persuade him, but her attempt was unsuccessful.

During Eadred's reign Æthelwold asked for permission to go abroad to gain a deeper understanding of the scriptures and a monk's religious life, no doubt at a reformed monastery such as Fleury. He may have thought that the discipline at Glastonbury was too lax. Eadred refused on his mother's advice that he should not allow such a wise man to leave his kingdom, instead appointing him as abbot of Abingdon, which was then served by secular priests and which Æthelwold transformed into a leading Benedictine abbey. Eadred supported the community, including granting it a 100 hide royal estate at Abingdon, and Eadgifu was an even more generous donor. Eadred travelled to Abingdon to plan the monastery there and personally measured the foundations where he proposed to raise the walls. Æthelwold then invited him to dine and he accepted. The king ordered that the mead should flow plentifully and the doors were locked so that none would be seen leaving the royal dinner. Some Northumbrian thegns accompanying the king got drunk, as was their custom, and were very merry when they left. However, Eadred died before the work could be carried out, and the building was not constructed until Edgar came to the throne.

Supporters of monastic reform were devoted to cults of saints and their relics. When Eadred burnt down Ripon Minster during his invasion of Northumbria, Oda had the relics of Saint Wilfrid

Wilfrid ( – 709 or 710) was an English bishop and saint. Born a Northumbrian noble, he entered religious life as a teenager and studied at Lindisfarne, at Canterbury, in Francia, and at Rome; he returned to Northumbria in about 660, and ...

, and Ripon's copy of the ''Vita Sancti Wilfrithi

The ''Vita Sancti Wilfrithi'' or ''Life of St Wilfrid'' (spelled "Wilfrid" in the modern era) is an early 8th-century hagiographic text recounting the life of the Northumbrian bishop, Wilfrid. Although a hagiography, it has few miracles, while ...

'' by Eddius

Stephen of Ripon was the author of the eighth-century hagiographic text '' Vita Sancti Wilfrithi'' ("Life of Saint Wilfrid"). Other names once traditionally attributed to him are Eddius Stephanus or Æddi Stephanus, but these names are no longer ...

(Stephen of Ripon), seized and brought to Canterbury. The ''Vita'' provided the basis for a new metrical life of Wilfrid (''Breuiloquium Vitae Wilfridi'') by Frithegod

Frithegod, (flourished ''circa'' (''c.'') 950 to ''c.'' 958) was a poet and clergyman in the mid 10th-century who served Oda of Canterbury, an Archbishop of Canterbury. As a non-native of England, he came to Canterbury and entered Oda's service a ...

, a Frankish scholar in Oda's household, and a preface in Oda's name (although probably drafted by Frithegod) justified the theft by accusing Ripon of scandalous neglect of Wilfrid's relics. Michael Lapidge Michael Lapidge, FBA (born 8 February 1942) is a scholar in the field of Medieval Latin literature, particularly that composed in Anglo-Saxon England during the period 600–1100 AD; he is an emeritus Fellow of Clare College, Cambridge, a Fellow ...

sees the destruction of the minster as providing the pretext for "a notorious ''furtum sacrum''" (sacred theft). Wilfrid had been an assertively independent northern bishop and in the historian David Rollason

David W. Rollason is an English historian and medievalist. He is a Professor in history at Durham University. He specialises in the cult of saints in Anglo-Saxon England, the history of Northumbria and in the historical writings of Durham, most n ...

's view the theft may have been intended to prevent the relics from becoming a focus for opposition to the West Saxon dynasty. Kings were also avid collectors of relics, which demonstrated their piety and increased their prestige, and Eadred left bequests in his will to priests he had appointed to look after his own relics.

Under Edgar, the view of Æthelwold and his circle that Benedictine monasticism was the only worthwhile form of religious life became dominant, but this was not the view of earlier kings such as Eadred. In 951 he appointed Ælfsige

Ælfsige (or Aelfsige, Ælfsin or Aelfsin; died 959) was Bishop of Winchester before he became Archbishop of Canterbury in 959.

Life

Ælfsige became Bishop of Winchester in 951.Fryde, et al. ''Handbook of British Chronology'' p. 223 In 958, wi ...

, a married man with a son, as bishop of Winchester. Ælfsige was not a reformer and was later remembered as hostile to the cause. Eadred's reign saw a continuation of a trend away from ecclesiastical beneficiaries of charters. More than two-thirds of beneficiaries in Æthelstan's reign were ecclesiastics and two-thirds were laymen in Edmund's. Under Eadred and Eadwig, three-quarters were laymen.

In the mid-tenth century, some religious noblewomen received grants of land without being members of communities of nuns. Æthelstan granted two estates, Edmund seven and Eadred four. After this the practice ceased abruptly, apart from one further donation. The significance of the donations is uncertain, but the most likely explanation is that some aristocratic women were granted the estates so that they could pursue a religious vocation in their own way, whether by establishing a nunnery or living a religious life in their own homes. In 953 Eadred granted land in Sussex to his mother, and she is described in the charter as ''famula Dei'', which probably means that she adopted a religious life while retaining her own estates, and did not enter a monastery.

Learning

Glastonbury and Abingdon were leading centres of learning, and Dunstan and Æthelwold were both excellent Latinists, but little is known of the studies at their monasteries. Oda was also a competent Latin scholar and his household at Canterbury was the other main centre of learning in the mid-tenth century. The most brilliant scholar there was Frithegod. His poem ''Breuiloquium Vitae Wilfridi'' is described by Lapidge, an expert onmedieval Latin

Medieval Latin was the form of Literary Latin used in Roman Catholic Western Europe during the Middle Ages. In this region it served as the primary written language, though local languages were also written to varying degrees. Latin functioned ...

literature, as "perhaps the most remarkable monument of tenth-century Anglo-Latin literature". It is "one of the most brilliantly ingenious – but also damnably difficult – Latin products of Anglo-Saxon England", which "may be dubiously described as the 'masterpiece' of Anglo-Latin hermeneutic style

The hermeneutic style is a style of Latin in the later Roman and early Medieval periods characterised by the extensive use of unusual and arcane words, especially derived from Greek. The style is first found in the work of Apuleius in the secon ...

". Frithegod was a tutor to Oda's nephew Oswald Oswald may refer to:

People

*Oswald (given name), including a list of people with the name

*Oswald (surname), including a list of people with the name

Fictional characters

*Oswald the Reeve, who tells a tale in Geoffrey Chaucer's ''The Canterbur ...

, a future Archbishop of York and the third leader of the monastic reform movement. Frithegod returned to Francia when his patron Oda died in 958.

Eadred's will

Eadred's will is one of only two wills of Anglo-Saxon kings to survive. It reads:

:''In nomine Domini''. This is King Eadred's will. In the first place, he presents to the foundation wherein he desires that his body shall rest, two gold crosses and two swords with hilts of gold, and four hundred pounds. Item, he gives to the Old Minster at Winchester three estates, namely Downton, Damerham and

Eadred's will is one of only two wills of Anglo-Saxon kings to survive. It reads:

:''In nomine Domini''. This is King Eadred's will. In the first place, he presents to the foundation wherein he desires that his body shall rest, two gold crosses and two swords with hilts of gold, and four hundred pounds. Item, he gives to the Old Minster at Winchester three estates, namely Downton, Damerham and Calne

Calne () is a town and civil parish in Wiltshire, southwestern England,OS Explorer Map 156, Chippenham and Bradford-on-Avon Scale: 1:25 000.Publisher: Ordnance Survey A2 edition (2007). at the northwestern extremity of the North Wessex Downs ...

. Item, he gives to the New Minster

The New Minster in Winchester was a royal Benedictine abbey founded in 901 in Winchester in the English county of Hampshire.

Alfred the Great had intended to build the monastery, but only got around to buying the land. His son, Edward the El ...

three estates, namely Wherwell

Wherwell is a village on the River Test in Hampshire, England. The name may derive from its bubbling springs resulting in the Middle Ages place name “Hwerwyl” noted in AD 955, possibly meaning “kettle springs” or “cauldron springs.� ...

, Andover

Andover may refer to:

Places Australia

*Andover, Tasmania

Canada

* Andover Parish, New Brunswick

* Perth-Andover, New Brunswick

United Kingdom

* Andover, Hampshire, England

** RAF Andover, a former Royal Air Force station

United States

* Andov ...

and Clere; and to the Nunnaminster

St. Mary's Abbey, also known as the ''Nunnaminster'', was a Benedictine nunnery in Winchester, Hampshire, England. It was founded between 899 and 902 by Alfred the Great's widow Ealhswith, who was described as the 'builder' of the Nunnaminster in ...

, Shalbourne, Thatcham

Thatcham is an historic market town and civil parish in the English county of Berkshire, centred 3 miles (5 km) east of Newbury, 14 miles (24 km) west of Reading and 54 miles (87 km) west of London.

Geography

Thatcham straddles t ...

and Bradford

Bradford is a city and the administrative centre of the City of Bradford district in West Yorkshire, England. The city is in the Pennines' eastern foothills on the banks of the Bradford Beck. Bradford had a population of 349,561 at the 2011 ...

. Item, he gives to the Nunnaminster at Winchester thirty pounds. and thirty to Wilton, and thirty to Shaftesbury

Shaftesbury () is a town and civil parish in Dorset, England. It is situated on the A30 road, west of Salisbury, near the border with Wiltshire. It is the only significant hilltop settlement in Dorset, being built about above sea level on a ...

.

:Item, he gives sixteen hundred pounds for the redemption of his soul, and the good of his people, that they may be able to purchase for themselves relief from want and from the heathen army, if they need o do so

O, or o, is the fifteenth letter and the fourth vowel letter in the Latin alphabet, used in the modern English alphabet, the alphabets of other western European languages and others worldwide. Its name in English is ''o'' (pronounced ), plu ...

Of this the Archbishop at Christchurch is to receive four hundred pounds, for the relief of the people of Kent and Surrey and Sussex and Berkshire; and if anything happen to the bishop, the money shall remain in the monastery, in the charge of the members of the council who are in that county. And Ælfsige, bishop of the see of Winchester, is to receive four hundred pounds, two hundred for Hampshire and one hundred each for Wiltshire and Dorsetshire; and if anything happen to him, it shall remain-as in a similar case mentioned above-in the charge of the members of the council who are in that county. Item, Abbot Dunstan is to receive two hundred pounds and to keep it at Glastonbury for the people of Somerset and Devon; and if anything happen to him, arrangements similar to those above shall be made. Item, Bishop Ælfsige is to receive the two hundred pounds left over, and keep he moneyat the episcopal see at Winchester, for whichever shire may need it. And Bishop Oscetel is to receive four hundred pounds, and keep it at the episcopal see at Dorchester for the Mercians, in accordance with the arrangement described above. Now Bishop Wulfhelm has that sum of four hundred pounds (?). Item, gold to the amount of two thousand mancus

Mancus (sometimes spelt ''mancosus'' or similar, from Arabic ''manqūsh'' منقوش) was a term used in early medieval Europe to denote either a gold coin, a weight of gold of 4.25g (equivalent to the Islamic gold dinar, and thus lighter than th ...

es is to be taken and minted into mancuses; and the archbishop is to receive one portion, and Bishop Ælfsige a second, and Bishop Oscetel a third, and they are to distribute them throughout the bishoprics for the sake of God and for the redemption of my soul.

:Item, I give to my mother the estates at Amesbury

Amesbury () is a town and civil parish in Wiltshire, England. It is known for the prehistoric monument of Stonehenge which is within the parish. The town is claimed to be the oldest occupied settlement in Great Britain, having been first settl ...

and Wantage

Wantage () is a historic market town and civil parish in Oxfordshire, England. Although within the boundaries of the historic county of Berkshire, it has been administered as part of the Vale of White Horse district of Oxfordshire since 1974. T ...

and Basing, and all the booklands which I have in Sussex, Surrey and Kent, and all those which she has previously had. Item I give to the archbishop two hundred mancuses of gold, reckoning the hundred at a hundred and twenty. And to each of my bishops one hundred and twenty mancuses of gold. And to each of my earls one hundred and twenty mancuses of gold. And to each ulyappointed seneschal

The word ''seneschal'' () can have several different meanings, all of which reflect certain types of supervising or administering in a historic context. Most commonly, a seneschal was a senior position filled by a court appointment within a royal, ...

, and each appointed chamberlain

Chamberlain may refer to:

Profession

*Chamberlain (office), the officer in charge of managing the household of a sovereign or other noble figure

People

*Chamberlain (surname)

**Houston Stewart Chamberlain (1855–1927), German-British philosop ...

and butler, eighty mancuses of gold. And to each of my chaplains whom I have put in charge of my relics, fifty mancuses of gold and five pounds in silver. And five pounds to each of the other priests. And thirty muncuses of gold to each ulyappointed steward, and to every ecclesiastic who has been appointed (?) since I succeeded to the throne, and to every member of my household, in whatever capacity he be employed, unless he be.......to the royal palaces.

:Item, I desire that twelve almsmen be chosen on each of the estates mentioned above, and if anything happen to any of them, another is to be put appointed his place; and this is to hold good so long as Christianity endures, to the glory of God and the redemption of my soul; and if anyone refuses to carry it out, his estate is to revert to the place where my body shall rest.

The will is described by Stenton as "the chief authority for the pre-Conquest royal household". It shows that ''discthegns'' (seneschals) served at his table and that the other principal officers were butlers and ''hræglthegns'' (keepers of the wardrobe). All the estates named in the will are in Wessex, reflecting the concentration of royal property there, although he also mentions booklands in the south-east without specifying the locations. Eadwig cannot have been happy at his exclusion from the will, and it appears to have been set aside following his accession.

Illness and death

Eadred suffered from ill-health at the end of his life which gradually got worse and led to his early death. Dunstan's first biographer, who probably attended court as a member of his household, wrote: :Unfortunately Dunstan's beloved King Eadred was very sickly all through his reign. At mealtimes he would suck the juice out of his food, chew what was left of it for a little and then spit it out: a practice that often turned the stomachs of the thegns dining with him. He dragged on an invalid existence as best he could, despite the protests of his body (?), for quite a long time. Finally his worsening illness came over him more and more often with a thousandfold weight, and brought him unhappily to his deathbed. The eleventh-century hagiographerHerman the Archdeacon

Herman the Archdeacon (also Hermann the Archdeacon and Hermann of Bury, born before 1040, died late 1090s) was a member of the household of Herfast, Bishop of East Anglia, in the 1070s and 1080s. Thereafter, he was a monk of Bury St Edmunds ...

described Eadred as "''debilis pedibus''" (crippled in both feet), and in his later years he probably delegated authority to leading magnates such as Dunstan. Meetings of the ''witan'' were rarer when he was ill and business was limited, with no appointments of ealdormen. He did not marry, perhaps due to his poor health, and he died in his early thirties on 23 November 955, at Frome

Frome ( ) is a town and civil parish in eastern Somerset, England. The town is built on uneven high ground at the eastern end of the Mendip Hills, and centres on the River Frome. The town, about south of Bath, is the largest in the Mendip d ...

in Somerset

( en, All The People of Somerset)

, locator_map =

, coordinates =

, region = South West England

, established_date = Ancient

, established_by =

, preceded_by =

, origin =

, lord_lieutenant_office =Lord Lieutenant of Somerset

, lor ...

.

He was buried in the Old Minster, Winchester

The Old Minster was the Anglo-Saxon cathedral for the diocese of Wessex and then Winchester from 660 to 1093. It stood on a site immediately north of and partially beneath its successor, Winchester Cathedral.

Some sources say that the minster w ...

, although that was probably not his choice as in his will he made bequests to an unspecified location where "he wishes his body to rest", and then property to the Old Minster, implying that they were different places. Eadwig and Ælfsige, bishop of Winchester, may have decided on the burial place. The historian Nicole Marafioti suggests that Eadred may have wished to be buried at Glastonbury and Eadwig insisted on Winchester in order to prevent Eadred's supporters from using the grave as "ideological leverage" against the new regime.

Assessment

Domestic politics and recovering control over the whole of England were central to Eadred's rule and, unlike Æthelstan and Edmund, he is not known to have played any part inWest Frankish

In medieval history, West Francia (Medieval Latin: ) or the Kingdom of the West Franks () refers to the western part of the Frankish Empire established by Charlemagne. It represents the earliest stage of the Kingdom of France, lasting from about ...

politics, although in 949 ambassadors from Eadred attended the court of Otto I

Otto I (23 November 912 – 7 May 973), traditionally known as Otto the Great (german: Otto der Große, it, Ottone il Grande), was East Frankish king from 936 and Holy Roman Emperor from 962 until his death in 973. He was the oldest son of He ...

, King of East Francia

East Francia (Medieval Latin: ) or the Kingdom of the East Franks () was a successor state of Charlemagne's empire ruled by the Carolingian dynasty until 911. It was created through the Treaty of Verdun (843) which divided the former empire int ...

at Aachen

Aachen ( ; ; Aachen dialect: ''Oche'' ; French and traditional English: Aix-la-Chapelle; or ''Aquisgranum''; nl, Aken ; Polish: Akwizgran) is, with around 249,000 inhabitants, the 13th-largest city in North Rhine-Westphalia, and the 28th ...

. Securing a general recognition of his authority was Eadred's primary duty, and his main preoccupation was dealing with northern rebellions. Northumbria fought for its independence against successive West Saxon kings, but the acceptance of Erik proved to be its last throw and it was finally conquered during Eadred's reign. Historians disagree on how great his role was. In the view of the historian Ben Snook, Eadred "relied on a kitchen cabinet to run the country on his behalf and seems never to have exercised much direct authority."

Hart suggests that in Edmund's reign Eadgifu and Æthelstan Half-King decided much of national policy, and the position did not change much under Eadred. By contrast, in Williams's view, Eadred was "clearly an able and even energetic king, hampered by debility and (at the last) by a serious illness which brought about his early death".

Eadred's attitude towards his nephews is uncertain. Some charters are attested by both Eadwig and Edgar as ''cliton'' (medieval Latin for prince), but others by Eadwig as ''cliton'' or ''ætheling'' (Old English

Old English (, ), or Anglo-Saxon, is the earliest recorded form of the English language, spoken in England and southern and eastern Scotland in the early Middle Ages. It was brought to Great Britain by Anglo-Saxon settlers in the mid-5th ...

for prince) and Edgar as his brother. When he acceded, Eadwig dispossessed Eadgifu and exiled Dunstan, apparently as part of an attempt to free himself from the powerful advisers of his father and uncle. The attempt failed, as within two years he was forced to share the kingdom with Edgar, who became King of the Mercians, while Eadwig retained Wessex. Eadwig died in 959 after a rule of only four years.

Notes

References

Bibliography

* *} * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * *External links

* {{DEFAULTSORT:Eadred 10th-century English monarchs House of Wessex Monarchs of England before 1066 Burials at Winchester Cathedral 920s births 955 deaths