The medieval English saw their economy as comprising three groups – the

clergy

Clergy are formal leaders within established religions. Their roles and functions vary in different religious traditions, but usually involve presiding over specific rituals and teaching their religion's doctrines and practices. Some of the ter ...

, who prayed; the

knights

A knight is a person granted an honorary title of knighthood by a head of state (including the Pope) or representative for service to the monarch, the church or the country, especially in a military capacity. Knighthood finds origins in the ...

, who fought; and the

peasants

A peasant is a pre-industrial agricultural laborer or a farmer with limited land-ownership, especially one living in the Middle Ages under feudalism and paying rent, tax, fees, or services to a landlord. In Europe, three classes of peasants ...

, who worked the landtowns involved in international trade.

[Bartlett, p. 313; Dyer 2009, p. 14.] Over the five centuries of the

Middle Ages

In the history of Europe, the Middle Ages or medieval period lasted approximately from the late 5th to the late 15th centuries, similar to the post-classical period of global history. It began with the fall of the Western Roman Empire ...

, the English economy would at first grow and then suffer an acute crisis, resulting in significant political and economic change. Despite economic dislocation in urban and extraction economies, including shifts in the holders of wealth and the location of these economies, the economic output of towns and mines developed and intensified over the period. By the end of the period, England had a weak government, by later standards, overseeing an economy dominated by rented farms controlled by gentry, and a thriving community of indigenous English merchants and corporations.

[

The 12th and 13th centuries saw a small development of the English economy.][Cantor 1982a, p. 18.] This was partially driven by the growth in the population from around 1.5 million at the time of the creation of the Domesday Book

Domesday Book () – the Middle English spelling of "Doomsday Book" – is a manuscript record of the "Great Survey" of much of England and parts of Wales completed in 1086 by order of King William I, known as William the Conqueror. The manusc ...

in 1086 to between 4 and 5 million in 1300.[Bailey, p. 41; Bartlett, p. 321; Cantor 1982a, p. 19.] More land, much of it at the expense of the royal forests, was brought into production to feed the growing population or to produce wool for export to Europe.[ Many hundreds of new towns, some of them planned, sprung up across England, supporting the creation of ]guild

A guild ( ) is an association of artisans and merchants who oversee the practice of their craft/trade in a particular area. The earliest types of guild formed as organizations of tradesmen belonging to a professional association. They sometim ...

s, charter fair A charter fair in England is a street fair or market which was established by Royal Charter. Many charter fairs date back to the Middle Ages, with their heyday occurring during the 13th century. Originally, most charter fairs started as street marke ...

s and other important medieval institutions.[ The descendants of the Jewish financiers who had first come to England with ]William the Conqueror

William I; ang, WillelmI (Bates ''William the Conqueror'' p. 33– 9 September 1087), usually known as William the Conqueror and sometimes William the Bastard, was the first Norman king of England, reigning from 1066 until his death in 10 ...

played a significant role in the growing economy, along with the new Cistercian

The Cistercians, () officially the Order of Cistercians ( la, (Sacer) Ordo Cisterciensis, abbreviated as OCist or SOCist), are a Catholic religious order of monks and nuns that branched off from the Benedictines and follow the Rule of Saint B ...

and Augustinian religious orders that came to become major players in the wool trade

Wool is the textile fibre obtained from sheep and other mammals, especially goats, rabbits, and camelids. The term may also refer to inorganic materials, such as mineral wool and glass wool, that have properties similar to animal wool.

As a ...

of the north. Mining increased in England, with the silver boom of the 12th century helping to fuel a fast-expanding currency.[

Economic growth began to falter by the end of the 13th century, owing to a combination of over-population, land shortages and depleted soils.][ The loss of life in the Great Famine of 1315–17 shook the English economy severely and population growth ceased; the first outbreak of the ]Black Death

The Black Death (also known as the Pestilence, the Great Mortality or the Plague) was a bubonic plague pandemic occurring in Western Eurasia and North Africa from 1346 to 1353. It is the most fatal pandemic recorded in human history, causi ...

in 1348 then killed around half the English population, with major implications for the post-plague economy.[ The agricultural sector shrank, with higher wages, lower prices and shrinking profits leading to the final demise of the old ]demesne

A demesne ( ) or domain was all the land retained and managed by a lord of the manor under the feudal system for his own use, occupation, or support. This distinguished it from land sub-enfeoffed by him to others as sub-tenants. The concept or ...

system and the advent of the modern farming system of cash rents for lands.[ The Peasants Revolt of 1381 shook the older feudal order and limited the levels of royal taxation considerably for a century to come.][ The 15th century saw the growth of the English ]cloth

Textile is an umbrella term that includes various fiber-based materials, including fibers, yarns, filaments, threads, different fabric types, etc. At first, the word "textiles" only referred to woven fabrics. However, weaving is not the ...

industry and the establishment of a new class of international English merchant, increasingly based in London and the South-West, prospering at the expense of the older, shrinking economy of the eastern towns.[ These new trading systems brought about the end of many of the international fairs and the rise of the ]chartered company

A chartered company is an association with investors or shareholders that is incorporated and granted rights (often exclusive rights) by royal charter (or similar instrument of government) for the purpose of trade, exploration, and/or coloni ...

.[ Together with improvements in ]metalworking

Metalworking is the process of shaping and reshaping metals to create useful objects, parts, assemblies, and large scale structures. As a term it covers a wide and diverse range of processes, skills, and tools for producing objects on every scale ...

and shipbuilding

Shipbuilding is the construction of ships and other floating vessels. It normally takes place in a specialized facility known as a shipyard. Shipbuilders, also called shipwrights, follow a specialized occupation that traces its roots to bef ...

, this represents the end of the medieval economy, and the beginnings of the early modern period in English economics.[

]

Invasion and the early Norman period (1066–1100)

William the Conqueror

William I; ang, WillelmI (Bates ''William the Conqueror'' p. 33– 9 September 1087), usually known as William the Conqueror and sometimes William the Bastard, was the first Norman king of England, reigning from 1066 until his death in 10 ...

invaded England in 1066, defeating the Anglo-Saxon King Harold Godwinson

Harold Godwinson ( – 14 October 1066), also called Harold II, was the last crowned Anglo-Saxon English king. Harold reigned from 6 January 1066 until his death at the Battle of Hastings, fighting the Norman invaders led by William the ...

at the Battle of Hastings

The Battle of Hastings nrf, Batâle dé Hastings was fought on 14 October 1066 between the Norman-French army of William, the Duke of Normandy, and an English army under the Anglo-Saxon King Harold Godwinson, beginning the Norman Conque ...

and placing the country under Norman rule. This campaign was followed by fierce military operations known as the Harrying of the North

The Harrying of the North was a series of campaigns waged by William the Conqueror in the winter of 1069–1070 to subjugate northern England, where the presence of the last Wessex claimant, Edgar Ætheling, had encouraged Anglo- Danish re ...

in 1069–70, extending Norman authority across the north of England. William's system of government was broadly feudal

Feudalism, also known as the feudal system, was the combination of the legal, economic, military, cultural and political customs that flourished in medieval Europe between the 9th and 15th centuries. Broadly defined, it was a way of structur ...

in that the right to possess land was linked to service to the king, but in many other ways the invasion did little to alter the nature of the English economy. Most of the damage done in the invasion was in the north and the west of England, some of it still recorded as "wasteland" in 1086.

Agriculture and mining

English agriculture

Agriculture formed the bulk of the English economy at the time of the Norman invasion.

Agriculture formed the bulk of the English economy at the time of the Norman invasion.[ Twenty years after the invasion, 35% of England was covered in ]arable land

Arable land (from the la, arabilis, "able to be ploughed") is any land capable of being ploughed and used to grow crops.''Oxford English Dictionary'', "arable, ''adj''. and ''n.''" Oxford University Press (Oxford), 2013. Alternatively, for th ...

, 25% was put to pasture

Pasture (from the Latin ''pastus'', past participle of ''pascere'', "to feed") is land used for grazing. Pasture lands in the narrow sense are enclosed tracts of farmland, grazed by domesticated livestock, such as horses, cattle, sheep, or sw ...

, 15% was covered by woodlands and the remaining 25% was predominantly moorland, fen

A fen is a type of peat-accumulating wetland fed by mineral-rich ground or surface water. It is one of the main types of wetlands along with marshes, swamps, and bogs. Bogs and fens, both peat-forming ecosystems, are also known as mires ...

s and heaths. Wheat formed the single most important arable crop, but rye, barley

Barley (''Hordeum vulgare''), a member of the grass family, is a major cereal grain grown in temperate climates globally. It was one of the first cultivated grains, particularly in Eurasia as early as 10,000 years ago. Globally 70% of barley p ...

and oats

The oat (''Avena sativa''), sometimes called the common oat, is a species of cereal grain grown for its seed, which is known by the same name (usually in the plural, unlike other cereals and pseudocereals). While oats are suitable for human co ...

were also cultivated extensively.[ In the more fertile parts of the country, such as the ]Thames valley

The Thames Valley is an informally-defined sub-region of South East England, centred on the River Thames west of London, with Oxford as a major centre. Its boundaries vary with context. The area is a major tourist destination and economic hub, ...

, the Midlands

The Midlands (also referred to as Central England) are a part of England that broadly correspond to the Kingdom of Mercia of the Early Middle Ages, bordered by Wales, Northern England and Southern England. The Midlands were important in the In ...

and the east of England, legumes

A legume () is a plant in the family Fabaceae (or Leguminosae), or the fruit or seed of such a plant. When used as a dry grain, the seed is also called a pulse. Legumes are grown agriculturally, primarily for human consumption, for livestock for ...

and beans

A bean is the seed of several plants in the family Fabaceae, which are used as vegetables for human or animal food. They can be cooked in many different ways, including boiling, frying, and baking, and are used in many traditional dishes thr ...

were also cultivated.[ Sheep, ]cattle

Cattle (''Bos taurus'') are large, domesticated, cloven-hooved, herbivores. They are a prominent modern member of the subfamily Bovinae and the most widespread species of the genus '' Bos''. Adult females are referred to as cows and adult ...

, oxen and pigs were kept on English holdings, although most of these breeds were much smaller than modern equivalents and most would have been slaughtered in winter.

Manorial system

In the century prior to the Norman invasion, England's great estates, owned by the king, bishops, monasteries and

In the century prior to the Norman invasion, England's great estates, owned by the king, bishops, monasteries and thegn

In Anglo-Saxon England, thegns were aristocratic landowners of the second rank, below the ealdormen who governed large areas of England. The term was also used in early medieval Scandinavia for a class of retainers. In medieval Scotland, there ...

s, had been slowly broken up as a consequence of inheritance, wills, marriage settlements or church purchases. Most of the smaller landowning nobility lived on their properties and managed their own estates. The pre-Norman landscape had seen a trend away from isolated hamlets and towards larger villages engaged in arable cultivation in a band running north–south across England. These new villages had adopted an open field system

The open-field system was the prevalent agricultural system in much of Europe during the Middle Ages and lasted into the 20th century in Russia, Iran, and Turkey. Each manor or village had two or three large fields, usually several hundred acr ...

in which fields were divided into small strips of land, individually owned, with crops rotated between the field each year and the local woodlands and other common land

Common land is land owned by a person or collectively by a number of persons, over which other persons have certain common rights, such as to allow their livestock to graze upon it, to collect wood, or to cut turf for fuel.

A person who has ...

s carefully managed. Agricultural land on a manor was divided between some fields that the landowner would manage and cultivate directly, called demesne

A demesne ( ) or domain was all the land retained and managed by a lord of the manor under the feudal system for his own use, occupation, or support. This distinguished it from land sub-enfeoffed by him to others as sub-tenants. The concept or ...

land, and the majority of the fields that would be cultivated by local peasants, who would pay rent to the landowner either through agricultural labour on the lord's demesne fields or through cash or produce.[Bartlett, p. 313.] Around 6,000 watermill

A watermill or water mill is a mill that uses hydropower. It is a structure that uses a water wheel or water turbine to drive a mechanical process such as milling (grinding), rolling, or hammering. Such processes are needed in the production ...

s of varying power and efficiency had been built in order to grind flour, freeing up peasant labour for other more productive agricultural tasks. The early English economy was not a subsistence economy and many crops were grown by peasant farmers for sale to the early English towns.[Dyer 2009, p. 14.]

The Normans initially did not significantly alter the operation of the manor or the village economy.[Douglas, p. 310.] William reassigned large tracts of land amongst the Norman elite, creating vast estates in some areas, particularly along the Welsh border and in Sussex

Sussex (), from the Old English (), is a historic county in South East England that was formerly an independent medieval Anglo-Saxon kingdom. It is bounded to the west by Hampshire, north by Surrey, northeast by Kent, south by the Englis ...

. The biggest change in the years after the invasion was the rapid reduction in the number of slaves being held in England. In the 10th century slaves had been very numerous, although their number had begun to diminish as a result of economic and religious pressure. Nonetheless, the new Norman aristocracy proved harsh landlords.[Douglas, p. 312.] The wealthier, formerly more independent Anglo-Saxon peasants found themselves rapidly sinking down the economic hierarchy, swelling the numbers of unfree workers, or serfs

Serfdom was the status of many peasants under feudalism, specifically relating to manorialism, and similar systems. It was a condition of debt bondage and indentured servitude with similarities to and differences from slavery, which developed ...

, forbidden to leave their manor and seek alternative employment.[ Those Anglo-Saxon nobles who had survived the invasion itself were rapidly assimilated into the Norman elite or economically crushed.

]

Creation of the forests

The Normans also established the

The Normans also established the royal forest

A royal forest, occasionally known as a kingswood (), is an area of land with different definitions in England, Wales, Scotland and Ireland. The term ''forest'' in the ordinary modern understanding refers to an area of wooded land; however, the ...

s. In Anglo-Saxon times there had been special woods for hunting called "hays", but the Norman forests were much larger and backed by legal mandate.[Dyer 2009, p. 18.] The new forests were not necessarily heavily wooded but were defined instead by their protection and exploitation by the crown. The Norman forests were subject to special royal jurisdiction; forest law was "harsh and arbitrary, a matter purely for the King's will".[Huscroft, p. 97.] Forests were expected to supply the king with hunting grounds, raw materials, goods and money.[ Revenue from forest rents and fines came to become extremely significant and forest wood was used for castles and royal ship building.][Cantor 1982b, p. 63.] Several forests played a key role in mining, such as the iron mining and working in the Forest of Dean

The Forest of Dean is a geographical, historical and cultural region in the western part of the county of Gloucestershire, England. It forms a roughly triangular plateau bounded by the River Wye to the west and northwest, Herefordshire to ...

and lead mining in the Forest of High Peak

The Forest of High Peak was, in medieval times, a moorland forest covering most of the north west of Derbyshire, England, extending as far south as Tideswell and Buxton. From the time of the Norman Conquest it was established as a royal huntin ...

.[ Several other groups bound up economically with forests; many monasteries had special rights in particular forests, for example for hunting or tree felling. The royal forests were accompanied by the rapid creation of locally owned ]parks

A park is an area of natural, semi-natural or planted space set aside for human enjoyment and recreation or for the protection of wildlife or natural habitats. Urban parks are green spaces set aside for recreation inside towns and cities. ...

and chases.

Trade, manufacturing and the towns

Although primarily rural, England had a number of old, economically important towns in 1066.

Although primarily rural, England had a number of old, economically important towns in 1066.[ A large amount of trade came through the Eastern towns, including London, ]York

York is a cathedral city with Roman origins, sited at the confluence of the rivers Ouse and Foss in North Yorkshire, England. It is the historic county town of Yorkshire. The city has many historic buildings and other structures, such as a ...

, Winchester

Winchester is a City status in the United Kingdom, cathedral city in Hampshire, England. The city lies at the heart of the wider City of Winchester, a local government Districts of England, district, at the western end of the South Downs Nation ...

, Lincoln, Norwich

Norwich () is a cathedral city and district of Norfolk, England, of which it is the county town. Norwich is by the River Wensum, about north-east of London, north of Ipswich and east of Peterborough. As the seat of the Episcopal see, See of ...

, Ipswich

Ipswich () is a port town and borough in Suffolk, England, of which it is the county town. The town is located in East Anglia about away from the mouth of the River Orwell and the North Sea. Ipswich is both on the Great Eastern Main Line ...

and Thetford

Thetford is a market town and civil parish in the Breckland District of Norfolk, England. It is on the A11 road between Norwich and London, just east of Thetford Forest. The civil parish, covering an area of , in 2015 had a population of 24, ...

.[Stenton, pp. 162, 166.] Much of this trade was with France, the Low Countries

The term Low Countries, also known as the Low Lands ( nl, de Lage Landen, french: les Pays-Bas, lb, déi Niddereg Lännereien) and historically called the Netherlands ( nl, de Nederlanden), Flanders, or Belgica, is a coastal lowland region in N ...

and Germany, but the North-East of England traded with partners as far away as Sweden. Cloth was already being imported to England before the invasion through the mercery

Mercery (from French , meaning "habderdashery" (goods) or "haberdashery" (a shop trading in textiles and notions) initially referred to silk, linen and fustian textiles among various other piece goods imported to England in the 12th century. ...

trade.

Some towns, such as York, suffered from Norman sacking during William's northern campaigns.[Douglas, p. 313.] Other towns saw the widespread demolition of houses to make room for new motte and bailey

A motte-and-bailey castle is a European fortification with a wooden or stone keep situated on a raised area of ground called a motte, accompanied by a walled courtyard, or bailey, surrounded by a protective ditch and palisade. Relatively easy t ...

fortifications, as was the case in Lincoln.[ The Norman invasion also brought significant economic changes with the arrival of the first Jews to English cities. William I brought over wealthy Jews from the ]Rouen

Rouen (, ; or ) is a city on the River Seine in northern France. It is the prefecture of the region of Normandy and the department of Seine-Maritime. Formerly one of the largest and most prosperous cities of medieval Europe, the population ...

community in Normandy to settle in London, apparently to carry out financial services for the crown. In the years immediately after the invasion, a lot of wealth was drawn out of England in various ways by the Norman rulers and reinvested in Normandy, making William immensely wealthy as an individual ruler.

The minting of coins was decentralised in the Saxon period; every borough was mandated to have a mint and therefore a centre for trading in bullion.[Stenton, p. 162.] Nonetheless, there was strict royal control over these moneyer

A moneyer is a private individual who is officially permitted to mint money. Usually the rights to coin money are bestowed as a concession by a state or government. Moneyers have a long tradition, dating back at least to ancient Greece. They bec ...

s, and coin dies Dies may refer to:

* Dies (deity), the Roman counterpart of the Greek goddess Hemera, the personification of day, daughter of Nox (Night) and Erebus (Darkness).

* Albert Christoph Dies (1755–1822), German painter, composer, and biographer

* Jos ...

could only be made in London.[ William retained this process and generated a high standard of Norman coins, leading to the use of the term "sterling" as the name for the Norman silver coins.][

]

Governance and taxation

William I inherited the Anglo-Saxon system in which the king drew his revenues from: a mixture of customs; profits from re-minting coinage; fines; profits from his own demesne lands; and the system of English land-based taxation called the geld. William reaffirmed this system, enforcing collection of the geld through his new system of sheriffs and increasing the taxes on trade. William was also famous for commissioning the Domesday Book

Domesday Book () – the Middle English spelling of "Doomsday Book" – is a manuscript record of the "Great Survey" of much of England and parts of Wales completed in 1086 by order of King William I, known as William the Conqueror. The manusc ...

in 1086, a vast document which attempted to record the economic condition of his new kingdom.

Mid-medieval growth (1100–1290)

The 12th and 13th centuries were a period of huge economic growth in England. The population of England rose from around 1.5 million in 1086 to around 4 or 5 million in 1300, stimulating increased agricultural outputs and the export of raw materials to Europe. In contrast to the previous two centuries, England was relatively secure from invasion. Except for the years of the Anarchy

The Anarchy was a civil war in England and Normandy between 1138 and 1153, which resulted in a widespread breakdown in law and order. The conflict was a war of succession precipitated by the accidental death of William Adelin, the only legi ...

, most military conflicts either had only localised economic impact or proved only temporarily disruptive. English economic thinking remained conservative, seeing the economy as consisting of three groups: the ''ordines'', those who fought, or the nobility; ''laboratores'', those who worked, in particular the peasantry; and ''oratores'', those who prayed, or the clerics. Trade and merchants played little part in this model and were frequently vilified at the start of the period, although they were increasingly tolerated towards the end of the 13th century.

Agriculture, fishing and mining

English agriculture and the landscape

Agriculture remained by far the most important part of the English economy during the 12th and 13th centuries.

Agriculture remained by far the most important part of the English economy during the 12th and 13th centuries.[ There remained a wide variety in English agriculture, influenced by local geography; in areas where grain could not be grown, other resources were exploited instead. In the ]Weald

The Weald () is an area of South East England between the parallel chalk escarpments of the North and the South Downs. It crosses the counties of Hampshire, Surrey, Sussex and Kent. It has three separate parts: the sandstone "High Weald" in the ...

, for example, agriculture centred on grazing animals on the woodland pastures, whilst in the Fens

The Fens, also known as the , in eastern England are a naturally marshy region supporting a rich ecology and numerous species. Most of the fens were drained centuries ago, resulting in a flat, dry, low-lying agricultural region supported by a ...

fishing and bird-hunting was supplemented by basket-making and peat

Peat (), also known as turf (), is an accumulation of partially Decomposition, decayed vegetation or organic matter. It is unique to natural areas called peatlands, bogs, mires, Moorland, moors, or muskegs. The peatland ecosystem covers and ...

-cutting.[Bailey, p. 51.] In some locations, such as Lincolnshire

Lincolnshire (abbreviated Lincs.) is a Counties of England, county in the East Midlands of England, with a long coastline on the North Sea to the east. It borders Norfolk to the south-east, Cambridgeshire to the south, Rutland to the south-we ...

and Droitwich, salt manufacture was important, including production for the export market.[Bailey, p. 53.] Fishing became an important trade along the English coast, especially in Great Yarmouth

Great Yarmouth (), often called Yarmouth, is a seaside town and unparished area in, and the main administrative centre of, the Borough of Great Yarmouth in Norfolk, England; it straddles the River Yare and is located east of Norwich. A pop ...

and Scarborough, and the herring

Herring are forage fish, mostly belonging to the family of Clupeidae.

Herring often move in large schools around fishing banks and near the coast, found particularly in shallow, temperate waters of the North Pacific and North Atlantic Ocean ...

was a particularly popular catch; salted at the coast, it could then be shipped inland or exported to Europe. Piracy between competing English fishing fleets was not unknown during the period.[ Sheep were the most common farm animal in England during the period, their numbers doubling by the 14th century.][Bartlett, p. 368; Bailey, p. 44.] Sheep became increasingly widely used for wool

Wool is the textile fibre obtained from sheep and other mammals, especially goats, rabbits, and camelids. The term may also refer to inorganic materials, such as mineral wool and glass wool, that have properties similar to animal wool. ...

, particularly in the Welsh borders

The Welsh Marches ( cy, Y Mers) is an imprecisely defined area along the border between England and Wales in the United Kingdom. The precise meaning of the term has varied at different periods.

The English term Welsh March (in Medieval Latin ...

, Lincolnshire and the Pennines

The Pennines (), also known as the Pennine Chain or Pennine Hills, are a range of uplands running between three regions of Northern England: North West England on the west, North East England and Yorkshire and the Humber on the east. Common ...

.[ Pigs remained popular on holdings because of their ability to scavenge for food.][ Oxen remained the primary plough animal, with horses used more widely on farms in the south of England towards the end of the 12th century.][Bailey, p. 44.] Rabbits were introduced from France in the 13th century and farmed for their meat in special warrens.

The underlying productivity of English agriculture remained low, despite the increases in food production.[ Wheat prices fluctuated heavily year to year, depending on local harvests; up to a third of the grain produced in England was potentially for sale, and much of it ended up in the growing towns. Despite their involvement in the market, even the wealthiest peasants prioritised spending on housing and clothing, with little left for other personal consumption. Records of household belongings show most possessing only "old, worn-out and mended utensils" and tools.

The royal forests grew in size for much of the 12th century, before contracting in the late 13th and early 14th centuries. Henry I extended the size and scope of royal forests, especially in ]Yorkshire

Yorkshire ( ; abbreviated Yorks), formally known as the County of York, is a Historic counties of England, historic county in northern England and by far the largest in the United Kingdom. Because of its large area in comparison with other Eng ...

; after the Anarchy of 1135–53, Henry II continued to expand the forests until they comprised around 20% of England. In 1217 the Charter of the Forest

The Charter of the Forest of 1217 ( la, Carta Foresta) is a charter that re-established for free men rights of access to the royal forest that had been eroded by King William the Conqueror and his heirs. Many of its provisions were in force for c ...

was enacted, in part to mitigate the worst excesses of royal jurisdiction, and established a more structured range of fines and punishments for peasants who illegally hunted or felled trees in the forests. By the end of the century the king had come under increasing pressure to reduce the size of the royal forests, leading to the " Great Perambulation" around 1300; this significantly reduced the extent to the forests, and by 1334 they were only around two-thirds the size they had been in 1250. Royal revenue streams from the shrinking forests diminished considerably in the early 14th century.

Development of estate management

The Normans retained and reinforced the manorial system with its division between

The Normans retained and reinforced the manorial system with its division between demesne

A demesne ( ) or domain was all the land retained and managed by a lord of the manor under the feudal system for his own use, occupation, or support. This distinguished it from land sub-enfeoffed by him to others as sub-tenants. The concept or ...

and peasant lands paid for in agricultural labour.John

John is a common English name and surname:

* John (given name)

* John (surname)

John may also refer to:

New Testament

Works

* Gospel of John, a title often shortened to John

* First Epistle of John, often shortened to 1 John

* Secon ...

's reign, agricultural prices almost doubled, at once increasing the potential profits on the demesne estates and also increasing the cost of living for the landowners themselves. Landowners now attempted wherever possible to bring their demesne lands back into direct management, creating a system of administrators and officials to run their new system of estates.

New land was brought into cultivation to meet demand for food, including drained marshes and fens, such as Romney Marsh

Romney Marsh is a sparsely populated wetland area in the counties of Kent and East Sussex in the south-east of England. It covers about . The Marsh has been in use for centuries, though its inhabitants commonly suffered from malaria until ...

, the Somerset Levels

The Somerset Levels are a coastal plain and wetland area of Somerset, England, running south from the Mendips to the Blackdown Hills.

The Somerset Levels have an area of about and are bisected by the Polden Hills; the areas to the south a ...

and the Fens; royal forests from the late 12th century onwards; and poorer lands in the north, south-west and in the Welsh Marches

The Welsh Marches ( cy, Y Mers) is an imprecisely defined area along the border between England and Wales in the United Kingdom. The precise meaning of the term has varied at different periods.

The English term Welsh March (in Medieval Latin ...

. The first windmill

A windmill is a structure that converts wind power into rotational energy using vanes called sails or blades, specifically to mill grain (gristmills), but the term is also extended to windpumps, wind turbines, and other applications, in some ...

s in England began to appear along the south and east coasts in the 12th century, expanding in number in the 13th, adding to the mechanised power available to the manors. By 1300 it has been estimated that there were more than 10,000 watermills in England, used both for grinding corn and for fulling

Fulling, also known as felting, tucking or walking ( Scots: ''waukin'', hence often spelled waulking in Scottish English), is a step in woollen clothmaking which involves the cleansing of woven or knitted cloth (particularly wool) to eli ...

cloth. Fish ponds were created on most estates to provide freshwater fish for the consumption of the nobility and church; these ponds were extremely expensive to create and maintain. Improved ways of running estates began to be circulated and were popularised in Walter de Henley's famous book ''Le Dite de Hosebondrie'', written around 1280. In some regions and under some landowners, investment and innovation increased yields significantly through improved ploughing and fertilisers – particularly in Norfolk

Norfolk () is a ceremonial and non-metropolitan county in East Anglia in England. It borders Lincolnshire to the north-west, Cambridgeshire to the west and south-west, and Suffolk to the south. Its northern and eastern boundaries are the Nor ...

, where yields eventually equalled later 18th-century levels.

Role of the Church in agriculture

The Church in England was a major landowner throughout the medieval period and played an important part in the development of agriculture and rural trade in the first two centuries of Norman rule. The

The Church in England was a major landowner throughout the medieval period and played an important part in the development of agriculture and rural trade in the first two centuries of Norman rule. The Cistercian order

The Cistercians, () officially the Order of Cistercians ( la, (Sacer) Ordo Cisterciensis, abbreviated as OCist or SOCist), are a Catholic religious order of monks and nuns that branched off from the Benedictines and follow the Rule of Sain ...

first arrived in England in 1128, establishing around 80 new monastic houses over the next few years; the wealthy Augustinians

Augustinians are members of Christian religious orders that follow the Rule of Saint Augustine, written in about 400 AD by Augustine of Hippo. There are two distinct types of Augustinians in Catholic religious orders dating back to the 12th–1 ...

also established themselves and expanded to occupy around 150 houses, all supported by agricultural estates, many of them in the north of England. By the 13th century these and other orders were acquiring new lands and had become major economic players both as landowners and as middlemen in the expanding wool trade

Wool is the textile fibre obtained from sheep and other mammals, especially goats, rabbits, and camelids. The term may also refer to inorganic materials, such as mineral wool and glass wool, that have properties similar to animal wool.

As a ...

. In particular, the Cistercians led the development of the grange

Grange may refer to:

Buildings

* Grange House, Scotland, built in 1564, and demolished in 1906

* Grange Estate, Pennsylvania, built in 1682

* Monastic grange, a farming estate belonging to a monastery

Geography Australia

* Grange, South Austr ...

system. Granges were separate manors in which the fields were all cultivated by the monastic officials, rather than being divided up between demesne and rented fields, and became known for trialling new agricultural techniques during the period. Elsewhere, many monasteries had significant economic impact on the landscape, such as the monks of Glastonbury

Glastonbury (, ) is a town and civil parish in Somerset, England, situated at a dry point on the low-lying Somerset Levels, south of Bristol. The town, which is in the Mendip district, had a population of 8,932 in the 2011 census. Glastonbur ...

, responsible for the draining of the Somerset Levels

The Somerset Levels are a coastal plain and wetland area of Somerset, England, running south from the Mendips to the Blackdown Hills.

The Somerset Levels have an area of about and are bisected by the Polden Hills; the areas to the south a ...

to create new pasture land.

The military crusading order of the Knights Templar

, colors = White mantle with a red cross

, colors_label = Attire

, march =

, mascot = Two knights riding a single horse

, equipment ...

also held extensive property in England, bringing in around £2,200 per annum by the time of their fall.[Forey, pp. 111, 230; Postan 1972, p. 102.] It comprised primarily rural holdings rented out for cash, but also included some urban properties in London.[ Following the dissolution of the Templar order in France by ]Philip IV of France

Philip IV (April–June 1268 – 29 November 1314), called Philip the Fair (french: Philippe le Bel), was King of France from 1285 to 1314. By virtue of his marriage with Joan I of Navarre, he was also King of Navarre as Philip I from ...

, Edward II

Edward II (25 April 1284 – 21 September 1327), also called Edward of Caernarfon, was King of England and Lord of Ireland from 1307 until he was deposed in January 1327. The fourth son of Edward I, Edward became the heir apparent to ...

ordered their properties to be seized and passed to the Hospitaller order in 1313, but in practice many properties were taken by local landowners and the hospital was still attempting to reclaim them twenty-five years later.

The Church was responsible for the system of tithe

A tithe (; from Old English: ''teogoþa'' "tenth") is a one-tenth part of something, paid as a contribution to a religious organization or compulsory tax to government. Today, tithes are normally voluntary and paid in cash or cheques or more ...

s, a levy of 10% on "all agrarian produce... other natural products gained via labour... wages received by servants and labourers, and to the profits of rural merchants". Tithes gathered in the form of produce could be either consumed by the recipient, or sold on and bartered for other resources. The tithe was relatively onerous for the typical peasant, although in many instances the actual levy fell below the desired 10%. Many clergy moved to the towns as part of the urban growth of the period, and by 1300 around one in twenty city dwellers was a clergyman.[Dyer 2009, p. 195.] One effect of the tithe was to transfer a considerable amount of agriculture wealth into the cities, where it was then spent by these urban clergy.[ The need to sell tithe produce that could not be consumed by the local clergy also spurred the growth of trade.

]

Expansion of mining

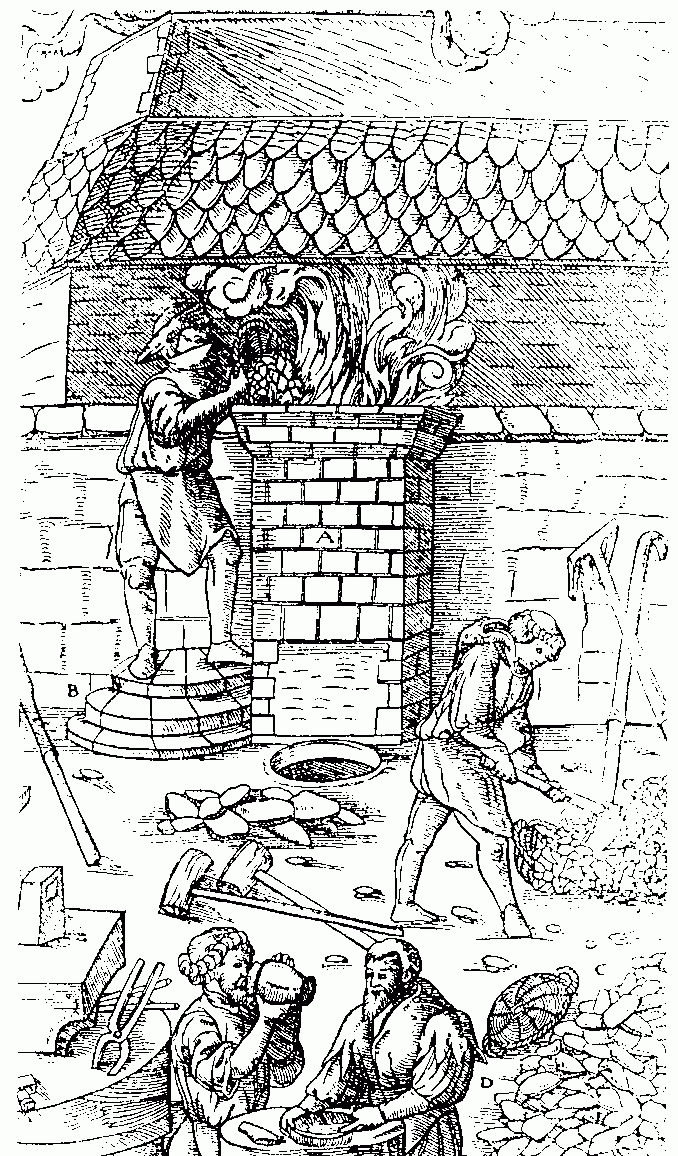

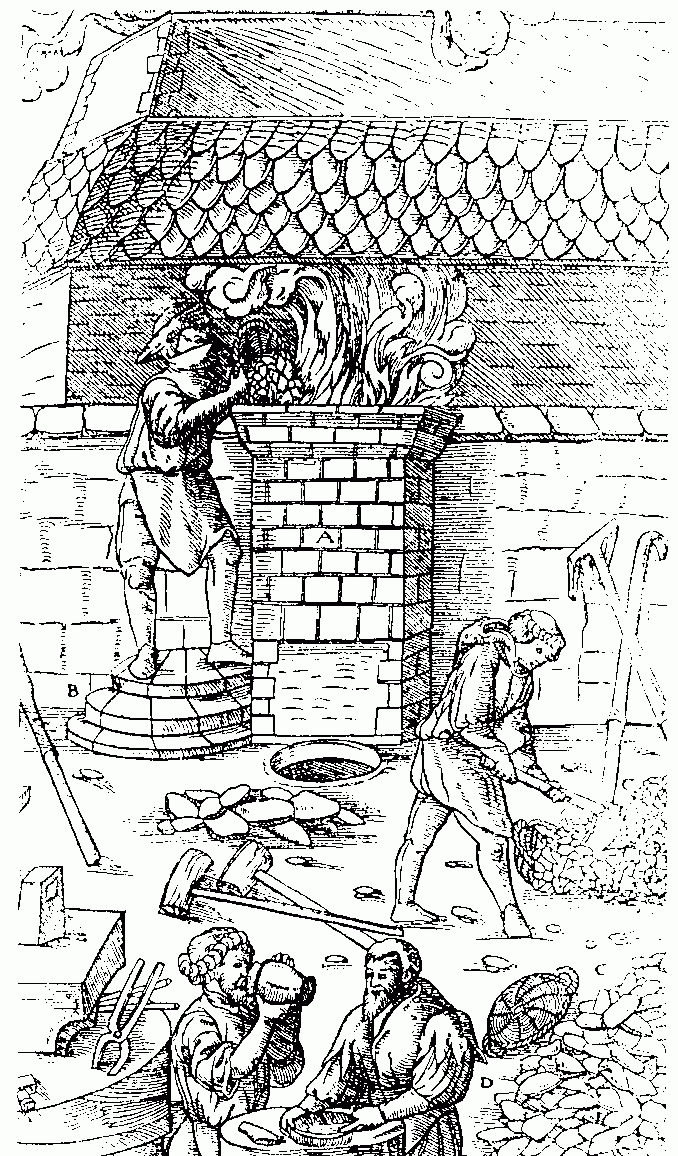

Mining did not make up a large part of the English medieval economy, but the 12th and 13th centuries saw an increased demand for metals in the country, thanks to the considerable population growth and building construction, including the great cathedrals and churches. Four metals were mined commercially in England during the period, namely

Mining did not make up a large part of the English medieval economy, but the 12th and 13th centuries saw an increased demand for metals in the country, thanks to the considerable population growth and building construction, including the great cathedrals and churches. Four metals were mined commercially in England during the period, namely iron

Iron () is a chemical element with symbol Fe (from la, ferrum) and atomic number 26. It is a metal that belongs to the first transition series and group 8 of the periodic table. It is, by mass, the most common element on Earth, right in ...

, tin, lead

Lead is a chemical element with the symbol Pb (from the Latin ) and atomic number 82. It is a heavy metal that is denser than most common materials. Lead is soft and malleable, and also has a relatively low melting point. When freshly cut, ...

and silver

Silver is a chemical element with the symbol Ag (from the Latin ', derived from the Proto-Indo-European ''h₂erǵ'': "shiny" or "white") and atomic number 47. A soft, white, lustrous transition metal, it exhibits the highest electrical ...

; coal

Coal is a combustible black or brownish-black sedimentary rock, formed as rock strata called coal seams. Coal is mostly carbon with variable amounts of other elements, chiefly hydrogen, sulfur, oxygen, and nitrogen.

Coal is formed when ...

was also mined from the 13th century onwards, using a variety of refining techniques.

Iron mining occurred in several locations, including the main English centre in the Forest of Dean

The Forest of Dean is a geographical, historical and cultural region in the western part of the county of Gloucestershire, England. It forms a roughly triangular plateau bounded by the River Wye to the west and northwest, Herefordshire to ...

, as well as in Durham Durham most commonly refers to:

*Durham, England, a cathedral city and the county town of County Durham

*County Durham, an English county

* Durham County, North Carolina, a county in North Carolina, United States

*Durham, North Carolina, a city in N ...

and the Weald

The Weald () is an area of South East England between the parallel chalk escarpments of the North and the South Downs. It crosses the counties of Hampshire, Surrey, Sussex and Kent. It has three separate parts: the sandstone "High Weald" in the ...

. Some iron to meet English demand was also imported from the continent, especially by the late 13th century.[Geddes, p. 169.] By the end of the 12th century, the older method of acquiring iron ore through strip mining

Surface mining, including strip mining, open-pit mining and mountaintop removal mining, is a broad category of mining in which soil and rock overlying the mineral deposit (the overburden) are removed, in contrast to underground mining, in which ...

was being supplemented by more advanced techniques, including tunnels, trenches and bell-pits.[ Iron ore was usually locally processed at a ]bloomery

A bloomery is a type of metallurgical furnace once used widely for smelting iron from its oxides. The bloomery was the earliest form of smelter capable of smelting iron. Bloomeries produce a porous mass of iron and slag called a ''bloom' ...

, and by the 14th century the first water-powered iron forge in England was built at Chingley. As a result of the diminishing woodlands and consequent increases in the cost of both wood and charcoal

Charcoal is a lightweight black carbon residue produced by strongly heating wood (or other animal and plant materials) in minimal oxygen to remove all water and volatile constituents. In the traditional version of this pyrolysis process, ...

, demand for coal increased in the 12th century and it began to be commercially produced from bell-pits and strip mining.[

A silver boom occurred in England after the discovery of silver near ]Carlisle

Carlisle ( , ; from xcb, Caer Luel) is a city that lies within the Northern English county of Cumbria, south of the Scottish border at the confluence of the rivers Eden, Caldew and Petteril. It is the administrative centre of the City ...

in 1133. Huge quantities of silver were produced from a semicircle of mines reaching across Cumberland

Cumberland ( ) is a historic counties of England, historic county in the far North West England. It covers part of the Lake District as well as the north Pennines and Solway Firth coast. Cumberland had an administrative function from the 12th c ...

, Durham and Northumberland

Northumberland () is a county in Northern England, one of two counties in England which border with Scotland. Notable landmarks in the county include Alnwick Castle, Bamburgh Castle, Hadrian's Wall and Hexham Abbey.

It is bordered by land ...

– up to three to four tonnes of silver were mined each year, more than ten times the previous annual production across the whole of Europe.[Blanchard, p. 29.] The result was a local economic boom and a major uplift to 12th-century royal finances. Tin mining was centred in Cornwall

Cornwall (; kw, Kernow ) is a Historic counties of England, historic county and Ceremonial counties of England, ceremonial county in South West England. It is recognised as one of the Celtic nations, and is the homeland of the Cornish people ...

and Devon

Devon ( , historically known as Devonshire , ) is a ceremonial and non-metropolitan county in South West England. The most populous settlement in Devon is the city of Plymouth, followed by Devon's county town, the city of Exeter. Devo ...

, exploiting alluvial

Alluvium (from Latin ''alluvius'', from ''alluere'' 'to wash against') is loose clay, silt, sand, or gravel that has been deposited by running water in a stream bed, on a floodplain, in an alluvial fan or beach, or in similar settings. ...

deposits and governed by the special Stannary Courts and Parliaments

Stannary law (derived from the la, stannum for tin) is the body of English law that governs tin mining in Devon and Cornwall; although no longer of much practical relevance, the stannary law remains part of the law of the United Kingdom and i ...

. Tin formed a valuable export good, initially to Germany and then later in the 14th century to the Low Countries

The term Low Countries, also known as the Low Lands ( nl, de Lage Landen, french: les Pays-Bas, lb, déi Niddereg Lännereien) and historically called the Netherlands ( nl, de Nederlanden), Flanders, or Belgica, is a coastal lowland region in N ...

. Lead was usually mined as a by-product of mining for silver, with mines in Yorkshire

Yorkshire ( ; abbreviated Yorks), formally known as the County of York, is a Historic counties of England, historic county in northern England and by far the largest in the United Kingdom. Because of its large area in comparison with other Eng ...

, Durham and the north, as well as in Devon. Economically fragile, the lead mines usually survived as a result of being subsidised by silver production.

Trade, manufacturing and the towns

Growth of English towns

After the end of the Anarchy, the number of small towns in England began to increase sharply. By 1297, 120 new towns had been established, and in 1350 – by when the expansion had effectively ceased – there were around 500 towns in England.[Hodgett, p. 57; Bailey, p. 47; Pounds, p. 15.] Many of these new towns were centrally planned: Richard I

Richard I (8 September 1157 – 6 April 1199) was King of England from 1189 until his death in 1199. He also ruled as Duke of Normandy, Aquitaine and Gascony, Lord of Cyprus, and Count of Poitiers, Anjou, Maine, and Nantes, and was ...

created Portsmouth

Portsmouth ( ) is a port and city in the ceremonial county of Hampshire in southern England. The city of Portsmouth has been a unitary authority since 1 April 1997 and is administered by Portsmouth City Council.

Portsmouth is the most d ...

, John

John is a common English name and surname:

* John (given name)

* John (surname)

John may also refer to:

New Testament

Works

* Gospel of John, a title often shortened to John

* First Epistle of John, often shortened to 1 John

* Secon ...

founded Liverpool

Liverpool is a City status in the United Kingdom, city and metropolitan borough in Merseyside, England. With a population of in 2019, it is the List of English districts by population, 10th largest English district by population and its E ...

, and successive monarchs followed with Harwich

Harwich is a town in Essex, England, and one of the Haven ports on the North Sea coast. It is in the Tendring District, Tendring district. Nearby places include Felixstowe to the north-east, Ipswich to the north-west, Colchester to the south-w ...

, Stony Stratford

Stony Stratford is a constituent town of Milton Keynes, Buckinghamshire, England. Historically it was a market town on the important route from London to Chester ( Watling Street, now the A5). It is also the name of a civil parish with a town ...

, Dunstable

Dunstable ( ) is a market town and civil parish in Bedfordshire, England, east of the Chiltern Hills, north of London. There are several steep chalk escarpments, most noticeable when approaching Dunstable from the north. Dunstable is t ...

, Royston

Royston may refer to:

Places

Australia

*Royston, Queensland, a rural locality

Canada

* Royston, British Columbia, a small hamlet

England

*Royston, Hertfordshire, a town and civil parish, formerly partly in Cambridgeshire

* Royston, South Yorks ...

, Baldock, Wokingham

Wokingham is a market town in Berkshire, England, west of London, southeast of Reading, north of Camberley and west of Bracknell.

History

Wokingham means 'Wocca's people's home'. Wocca was apparently a Saxon chieftain who may ...

, Maidenhead

Maidenhead is a market town in the Royal Borough of Windsor and Maidenhead in the county of Berkshire, England, on the southwestern bank of the River Thames. It had an estimated population of 70,374 and forms part of the border with southern Bu ...

and Reigate

Reigate ( ) is a town in Surrey, England, around south of central London. The settlement is recorded in Domesday Book in 1086 as ''Cherchefelle'' and first appears with its modern name in the 1190s. The earliest archaeological evidence for huma ...

. The new towns were usually located with access to trade routes in mind, rather than defence,[Astill, pp. 48–9.] and the streets were laid out to make access to the town's market convenient.[ A growing percentage of England's population lived in urban areas; estimates suggest that this rose from around 5.5% in 1086 to up to 10% in 1377.][Pounds, p. 80.]

London held a special status within the English economy. The nobility purchased and consumed many luxury goods and services in the capital, and as early as the 1170s the London markets were providing exotic products such as spices, incense

Incense is aromatic biotic material that releases fragrant smoke when burnt. The term is used for either the material or the aroma. Incense is used for aesthetic reasons, religious worship, aromatherapy, meditation, and ceremony. It may also b ...

, palm oil

Palm oil is an edible vegetable oil derived from the mesocarp (reddish pulp) of the fruit of the oil palms. The oil is used in food manufacturing, in beauty products, and as biofuel. Palm oil accounted for about 33% of global oils produced fr ...

, gems, silks, furs and foreign weapons. London was also an important hub for industrial activity; it had many blacksmiths making a wide range of goods, including decorative ironwork and early clocks. Pewter-working, using English tin and lead, was also widespread in London during the period. The provincial towns also had a substantial number of trades by the end of the 13th century – a large town like Coventry

Coventry ( or ) is a city in the West Midlands, England. It is on the River Sherbourne. Coventry has been a large settlement for centuries, although it was not founded and given its city status until the Middle Ages. The city is governed b ...

, for example, contained over three hundred different specialist occupations, and a smaller town such as Durham Durham most commonly refers to:

*Durham, England, a cathedral city and the county town of County Durham

*County Durham, an English county

* Durham County, North Carolina, a county in North Carolina, United States

*Durham, North Carolina, a city in N ...

could support some sixty different professions.[ The increasing wealth of the nobility and the church was reflected in the widespread building of ]cathedral

A cathedral is a church that contains the ''cathedra'' () of a bishop, thus serving as the central church of a diocese, conference, or episcopate. Churches with the function of "cathedral" are usually specific to those Christian denominations ...

s and other prestigious buildings in the larger towns, in turn making use of lead from English mines for roofing.

Land transport remained much more expensive than river or sea transport during the period. Many towns in this period, including York

York is a cathedral city with Roman origins, sited at the confluence of the rivers Ouse and Foss in North Yorkshire, England. It is the historic county town of Yorkshire. The city has many historic buildings and other structures, such as a ...

, Exeter

Exeter () is a city in Devon, South West England. It is situated on the River Exe, approximately northeast of Plymouth and southwest of Bristol.

In Roman Britain, Exeter was established as the base of Legio II Augusta under the personal comm ...

and Lincoln, were linked to the oceans by navigable rivers and could act as seaports, with Bristol

Bristol () is a City status in the United Kingdom, city, Ceremonial counties of England, ceremonial county and unitary authority in England. Situated on the River Avon, Bristol, River Avon, it is bordered by the ceremonial counties of Glouces ...

's port coming to dominate the lucrative trade in wine with Gascony

Gascony (; french: Gascogne ; oc, Gasconha ; eu, Gaskoinia) was a province of the southwestern Kingdom of France that succeeded the Duchy of Gascony (602–1453). From the 17th century until the French Revolution (1789–1799), it was part ...

by the 13th century, but shipbuilding generally remained on a modest scale and economically unimportant to England at this time. Transport remained very costly in comparison to the overall price of products.[Hodgett, p. 109.] By the 13th century, groups of common carriers ran carting businesses, and carting brokers existed in London to link traders and carters.[Bartlett, p. 363; Hodgett p. 109.] These used the four major land routes crossing England: Ermine Street

Ermine Street is a major Roman road in England that ran from London ('' Londinium'') to Lincoln ('' Lindum Colonia'') and York ('' Eboracum''). The Old English name was ''Earninga Strǣt'' (1012), named after a tribe called the ''Earn ...

, the Fosse Way

The Fosse Way was a Roman road built in Britain during the first and second centuries AD that linked Isca Dumnoniorum (Exeter) in the southwest and Lindum Colonia ( Lincoln) to the northeast, via Lindinis ( Ilchester), Aquae Sulis (Bath), ...

, Icknield Street and Watling Street

Watling Street is a historic route in England that crosses the River Thames at London and which was used in Classical Antiquity, Late Antiquity, and throughout the Middle Ages. It was used by the ancient Britons and paved as one of the main ...

.[ A large number of bridges were built during the 12th century to improve the trade network.

In the 13th century, England was still primarily supplying raw materials for export to Europe, rather than finished or processed goods.][Hodgett, p. 147.] There were some exceptions, such as very high-quality cloths from Stamford and Lincoln, including the famous "Lincoln Scarlet" dyed cloth.[ Despite royal efforts to encourage it, however, barely any English cloth was being exported by 1347.]

Expansion of the money supply

There was a gradual reduction in the number of locations allowed to mint coins in England; under Henry II, only 30 boroughs were still able to use their own moneyers, and the tightening of controls continued throughout the 13th century. By the reign of Edward I there were only nine mints outside London and the king created a new official called the

There was a gradual reduction in the number of locations allowed to mint coins in England; under Henry II, only 30 boroughs were still able to use their own moneyers, and the tightening of controls continued throughout the 13th century. By the reign of Edward I there were only nine mints outside London and the king created a new official called the Master of the Mint

Master of the Mint is a title within the Royal Mint given to the most senior person responsible for its operation. It was an important office in the governments of Scotland and England, and later Great Britain and then the United Kingdom, between ...

to oversee these and the thirty furnaces operating in London to meet the demand for new coins. The amount of money in circulation hugely increased in this period; before the Norman invasion there had been around £50,000 in circulation as coin, but by 1311 this had risen to more than £1 million. At any particular point in time, though, much of this currency might be being stored prior to being used to support military campaigns or to be sent overseas to meet payments, resulting in bursts of temporary deflation

In economics, deflation is a decrease in the general price level of goods and services. Deflation occurs when the inflation rate falls below 0% (a negative inflation rate). Inflation reduces the value of currency over time, but sudden deflatio ...

as coins ceased to circulate within the English economy.[Bolton pp. 32–3.] One physical consequence of the growth in the coinage was that coins had to be manufactured in large numbers, being moved in barrels and sacks to be stored in local treasuries for royal use as the king travelled.

Rise of the guilds

The first English guild

A guild ( ) is an association of artisans and merchants who oversee the practice of their craft/trade in a particular area. The earliest types of guild formed as organizations of tradesmen belonging to a professional association. They sometim ...

s emerged during the early 12th century.[Ramsay, p. xx.] These guilds were fraternities of craftsmen that set out to manage their local affairs including "prices, workmanship, the welfare of its workers, and the suppression of interlopers and sharp practices". Amongst these early guilds were the "guilds merchants", who ran the local markets in towns and represented the merchant community in discussions with the crown.Winchester

Winchester is a City status in the United Kingdom, cathedral city in Hampshire, England. The city lies at the heart of the wider City of Winchester, a local government Districts of England, district, at the western end of the South Downs Nation ...

. Over the following decades more guilds were created, often becoming increasingly involved in both local and national politics, although the guilds merchants were largely replaced by official groups established by new royal charters.

The craft guilds required relatively stable markets and a relative equality of income and opportunity amongst their members to function effectively.[ By the 14th century these conditions were increasingly uncommon.][Myers, p. 69.] The first strains were seen in London, where the old guild system began to collapse – more trade was being conducted at a national level, making it hard for craftsmen to both manufacture goods and trade in them, and there were growing disparities in incomes between the richer and poorer craftsmen.[ As a result, under ]Edward III

Edward III (13 November 1312 – 21 June 1377), also known as Edward of Windsor before his accession, was King of England and Lord of Ireland from January 1327 until his death in 1377. He is noted for his military success and for restoring ro ...

many guilds became companies or livery companies, chartered companies focusing on trade and finance, leaving the guild structures to represent the interests of the smaller, poorer manufacturers.

Merchants and the development of the charter fairs

The period also saw the development of

The period also saw the development of charter fair A charter fair in England is a street fair or market which was established by Royal Charter. Many charter fairs date back to the Middle Ages, with their heyday occurring during the 13th century. Originally, most charter fairs started as street marke ...

s in England, which reached their heyday in the 13th century. From the 12th century onwards, many English towns acquired a charter from the Crown allowing them to hold an annual fair, usually serving a regional or local customer base and lasting for two or three days.[Danziger and Gillingham, p. 65; Reyerson, p. 67.] The practice increased in the next century and over 2,200 charters were issued to markets and fairs by English kings between 1200 and 1270.[ Fairs grew in popularity as the international wool trade increased: the fairs allowed English wool producers and ports on the east coast to engage with visiting foreign merchants, circumnavigating those English merchants in London keen to make a profit as middlemen.][Danziger and Gillingham, p. 65.] At the same time, wealthy magnate

The magnate term, from the late Latin ''magnas'', a great man, itself from Latin ''magnus'', "great", means a man from the higher nobility, a man who belongs to the high office-holders, or a man in a high social position, by birth, wealth or ot ...

consumers in England began to use the new fairs as a way to buy goods like spices, wax, preserved fish and foreign cloth in bulk from the international merchants at the fairs, again bypassing the usual London merchants.

Some fairs grew into major international events, falling into a set sequence during the economic year, with the Stamford fair in Lent, St Ives' in Easter, Boston

Boston (), officially the City of Boston, is the state capital and most populous city of the Commonwealth of Massachusetts, as well as the cultural and financial center of the New England region of the United States. It is the 24th- mo ...

's in July, Winchester's in September and Northampton

Northampton () is a market town and civil parish in the East Midlands of England, on the River Nene, north-west of London and south-east of Birmingham. The county town of Northamptonshire, Northampton is one of the largest towns in England ...

's in November, with the many smaller fairs falling in-between. Although not as large as the famous Champagne fairs

The Champagne fairs were an annual cycle of trade fairs which flourished in different towns of the County of Champagne in Northeastern France in the 12th and 13th centuries, originating in local agricultural and stock fairs. Each fair lasted about ...

in France, these English "great fairs" were still huge events; St Ives' Great Fair, for example, drew merchants from Flanders

Flanders (, ; Dutch: ''Vlaanderen'' ) is the Flemish-speaking northern portion of Belgium and one of the communities, regions and language areas of Belgium. However, there are several overlapping definitions, including ones related to cultu ...

, Brabant Brabant is a traditional geographical region (or regions) in the Low Countries of Europe. It may refer to:

Place names in Europe

* London-Brabant Massif, a geological structure stretching from England to northern Germany

Belgium

* Province of Bra ...

, Norway, Germany and France for a four-week event each year, turning the normally small town into "a major commercial emporium".[Hodgett, p. 148.] Between 1280 and 1320 the trade was primarily dominated by Italian merchants, but by the early 14th century German merchants had begun to present serious competition to the Italians.[ The Germans formed a self-governing alliance of merchants in London called the " Hanse of the Steelyard" – the eventual ]Hanseatic League

The Hanseatic League (; gml, Hanse, , ; german: label= Modern German, Deutsche Hanse) was a medieval commercial and defensive confederation of merchant guilds and market towns in Central and Northern Europe. Growing from a few North German to ...

– and their role was confirmed under the Great Charter of 1303, which exempted them from paying the customary tolls for foreign merchants.[''Hanse'' is the old English word for "group".] One response to this was the creation of the Company of the Staple, a group of merchants established in English-held Calais

Calais ( , , traditionally , ) is a port city in the Pas-de-Calais department, of which it is a subprefecture. Although Calais is by far the largest city in Pas-de-Calais, the department's prefecture is its third-largest city of Arras. Th ...

in 1314 with royal approval, who were granted a monopoly on wool sales to Europe.

Jewish contribution to the English economy

The Jewish community in England continued to provide essential money-lending and banking services that were otherwise banned by the

The Jewish community in England continued to provide essential money-lending and banking services that were otherwise banned by the usury

Usury () is the practice of making unethical or immoral monetary loans that unfairly enrich the lender. The term may be used in a moral sense—condemning taking advantage of others' misfortunes—or in a legal sense, where an interest rate is c ...

laws, and grew in the 12th century by Jewish immigrants fleeing the fighting around Rouen

Rouen (, ; or ) is a city on the River Seine in northern France. It is the prefecture of the region of Normandy and the department of Seine-Maritime. Formerly one of the largest and most prosperous cities of medieval Europe, the population ...

. The Jewish community spread beyond London to eleven major English cities, primarily the major trading hubs in the east of England with functioning mints, all with suitable castles for protection of the often persecuted Jewish minority. By the time of the Anarchy and the reign of Stephen

Stephen or Steven is a common English first name. It is particularly significant to Christians, as it belonged to Saint Stephen ( grc-gre, Στέφανος ), an early disciple and deacon who, according to the Book of Acts, was stoned to death; ...

, the communities were flourishing and providing financial loans to the king.

Under Henry II, the Jewish financial community continued to grow richer still.[Stenton, pp. 193–4.] All major towns had Jewish centres, and even smaller towns, such as Windsor, saw visits by travelling Jewish merchants. Henry II used the Jewish community as "instruments for the collection of money for the Crown", and placed them under royal protection. The Jewish community at York

York is a cathedral city with Roman origins, sited at the confluence of the rivers Ouse and Foss in North Yorkshire, England. It is the historic county town of Yorkshire. The city has many historic buildings and other structures, such as a ...

lent extensively to fund the Cistercian order's acquisition of land and prospered considerably. Some Jewish merchants grew extremely wealthy, Aaron of Lincoln

Aaron of Lincoln (born at Lincoln, England, about 1125, died 1186) was an English Jewish financier. He is believed to have been the wealthiest man in Norman England; it is estimated that his wealth exceeded that of the King. He is first mention ...

so much that upon his death a special royal department had to be established to unpick his financial holdings and affairs.[Stenton, p. 200.]

By the end of Henry's reign the king ceased to borrow from the Jewish community and instead turned to an aggressive campaign of tallage Tallage or talliage (from the French ''tailler, i.e. '' a part cut out of the whole) may have signified at first any tax, but became in England and France a land use or land tenure tax. Later in England it was further limited to assessments by the ...

taxation and fines. Financial and anti-Semite violence grew under Richard I. After the massacre of the York community, in which numerous financial records were destroyed, seven towns were nominated to separately store Jewish bonds and money records and this arrangement ultimately evolved into the Exchequer of the Jews. After an initially peaceful start to John's reign, the king again began to extort money from the Jewish community, imprisoning the wealthier members, including Isaac of Norwich, until a huge, new taillage was paid. During the Baron's War of 1215–17, the Jews were subjected to fresh anti-Semitic attacks.[ Henry III restored some order and Jewish money-lending became sufficiently successful again to allow fresh taxation. The Jewish community became poorer towards the end of the century and was finally expelled from England in 1290 by Edward I, being largely replaced by foreign merchants.]

Governance and taxation

During the 12th century the Norman kings attempted to formalise the feudal governance system initially created after the invasion. After the invasion the king had enjoyed a combination of income from his own demesne lands, the Anglo-Saxon geld tax and fines. Successive kings found that they needed additional revenues, especially in order to pay for

During the 12th century the Norman kings attempted to formalise the feudal governance system initially created after the invasion. After the invasion the king had enjoyed a combination of income from his own demesne lands, the Anglo-Saxon geld tax and fines. Successive kings found that they needed additional revenues, especially in order to pay for mercenary

A mercenary, sometimes also known as a soldier of fortune or hired gun, is a private individual, particularly a soldier, that joins a military conflict for personal profit, is otherwise an outsider to the conflict, and is not a member of any ...

forces.[Lawler and Lawler, p. 6.] One way of doing this was to exploit the feudal system, and kings adopted the French feudal aid model, a levy of money imposed on feudal subordinates when necessary; another method was to exploit the scutage

Scutage is a medieval English tax levied on holders of a knight's fee under the feudal land tenure of knight-service. Under feudalism the king, through his vassals, provided land to knights for their support. The knights owed the king military s ...

system, in which feudal military service could be transmuted to a cash payment to the king.[ Taxation was also an option, although the old geld tax was increasingly ineffective due to a growing number of exemptions. Instead, a succession of kings created alternative land taxes, such as the ]tallage Tallage or talliage (from the French ''tailler, i.e. '' a part cut out of the whole) may have signified at first any tax, but became in England and France a land use or land tenure tax. Later in England it was further limited to assessments by the ...

and carucage

Carucage, from ''carrūca'', "wheeled plough"Mantella and Rigg ''Medieval Latin'' p. 220 was a medieval English land tax enacted by King Richard I in 1194, based on the size—variously calculated—of the taxpayer's estate. It was a replacement ...

taxes. These were increasingly unpopular and, along with the feudal charges, were condemned and constrained in the Magna Carta

(Medieval Latin for "Great Charter of Freedoms"), commonly called (also ''Magna Charta''; "Great Charter"), is a royal charter of rights agreed to by King John of England at Runnymede, near Windsor, on 15 June 1215. First drafted by t ...

of 1215. As part of the formalisation of the royal finances, Henry I created the Chancellor of the Exchequer

The chancellor of the Exchequer, often abbreviated to chancellor, is a senior minister of the Crown within the Government of the United Kingdom, and head of HM Treasury, His Majesty's Treasury. As one of the four Great Offices of State, the Ch ...

, a post which would lead to the maintenance of the Pipe rolls, a set of royal financial records of lasting significance to historians in tracking both royal finances and medieval prices.

Royal revenue streams still proved insufficient and from the middle of the 13th century there was a shift away from the earlier land-based tax system towards one based on a mixture of indirect and direct taxation.[Hodgett, p. 203.] At the same time, Henry III had introduced the practice of consulting with leading nobles on tax issues, leading to the system whereby the Parliament of England

The Parliament of England was the legislature of the Kingdom of England from the 13th century until 1707 when it was replaced by the Parliament of Great Britain. Parliament evolved from the great council of bishops and peers that advise ...

agreed on new taxes when required. In 1275, the "Great and Ancient Custom" began to tax woollen products and hides, with the Great Charter of 1303 imposing additional levies on foreign merchants in England, with the poundage tax introduced in 1347.[ In 1340, the discredited tallage tax system was finally abolished by ]Edward III

Edward III (13 November 1312 – 21 June 1377), also known as Edward of Windsor before his accession, was King of England and Lord of Ireland from January 1327 until his death in 1377. He is noted for his military success and for restoring ro ...

. Assessing the total impact of changes to royal revenues between 1086 and 1290 is difficult.[Carpenter, p. 51.] At best, Edward I was struggling in 1300 to match in real terms the revenues that Henry II had enjoyed in 1100, and considering the growth in the size of the English economy, the king's share of the national income had dropped considerably.[

In the English towns the burgage tenure for urban properties was established early on in the medieval period, and was based primarily on tenants paying cash rents rather than providing labour services. Further development of a set of taxes that could be raised by the towns included murage for walls, ]pavage

Pavage was a medieval toll for the maintenance or improvement of a road or street in medieval England, Wales and Ireland. The king by letters patent granted the right to collect it to an individual, or the corporation of a town, or to the "bailif ...

for streets, and pontage

Pontage was a term for a toll levied for the building or repair of bridges dating to the medieval era in England, Wales and Ireland.

Pontage was similar in nature to murage (a toll for the building of town walls) and pavage (a toll for pavi ...

, a temporary tax for the repair of bridges. Combined with the ''lex mercatoria

''Lex mercatoria'' (from the Latin for "merchant law"), often referred to as "the Law Merchant" in English, is the body of commercial law used by merchants throughout Europe during the medieval period. It evolved similar to English common law as ...

'', which was a set of codes and customary practices governing trading, these provided a reasonable basis for the economic governance of the towns.

The 12th century also saw a concerted attempt to curtail the remaining rights of unfree peasant workers and to set out their labour rents more explicitly in the form of the English Common Law. This process resulted in the Magna Carta explicitly authorising feudal landowners to settle law cases concerning feudal labour and fines through their own manorial courts rather than through the royal courts. These class relationships between lords and unfree peasants had complex economic implications. Peasant workers resented being unfree, but having continuing access to agricultural land was also important.[Bartlett, p. 316.] Under those rare circumstances where peasants were offered a choice between freedom but no land, and continued servitude, not all chose freedom and a minority chose to remain in servitude on the land.[ Lords benefited economically from their control of the manorial courts and dominating the courts made it easier to manipulate land ownership and rights in their own favour when land became in particularly short supply at the end of this period. Many of the labour duties lords could compel from the local peasant communities became less useful over the period.][Dyer 2009, p. 134.] Duties were fixed by custom, inflexible and understandably resented by the workers involved.[ As a result, by the end of the 13th century the productivity of such forced labour was significantly lower than that of free labour employed to do the same task.][ A number of lords responded by seeking to commute the duties of unfree peasants to cash alternatives, with the aim of hiring labour instead.][

]

Mid-medieval economic crisis – the Great Famine and the Black Death (1290–1350)

Great Famine