E. E. Smith on:

[Wikipedia]

[Google]

[Amazon]

Edward Elmer Smith (May 2, 1890 – August 31, 1965), publishing as E. E. Smith, Ph.D. and later as E. E. "Doc" Smith, was an American food engineer (specializing in

After college, Smith was a junior

After college, Smith was a junior

The effect of bleaching with oxides of nitrogen upon the baking quality and commercial value of wheat flour

', was published in 1919. (Warner and Fleischer give the title ''The Effect of the Oxides of Nitrogen upon the Carotin Molecule – C40H56'', which is difficult to explain.

Warner

but no other source, Smith began work on the sequel, ''Skylark Three'', before the first book was accepted.) Finally, upon seeing the April 1927 issue of ''

cover illustration

was extremely well received. Campbell's editorial in the December issue suggested that the October issue was the best issue of ''Astounding'' ever, and ''Gray Lensman'' was first place in the Analytical Laboratory statistics "by a lightyear", with three runners-up in a distant tie for second place. The cover was also praised by readers in ''Brass Tacks'', and Campbell noted, "We got a letter from E. E. Smith saying he and over artistHubert Rogers agreed on how Kinnison looked." Smith was the guest of honor at Chicon I, the second

Ballad of Boh Da Thone

in ''Gray Lensman'' (chapter 22, "Regeneration", in a conversation between Kinnison and MacDougall). Again in ''Gray Lensman'', Smith quotes from Merritt's ''Dwellers in the Mirage'', even name-checking the author:

doughnut

A doughnut or donut () is a type of food made from leavened fried dough. It is popular in many countries and is prepared in various forms as a sweet snack that can be homemade or purchased in bakeries, supermarkets, food stalls, and fra ...

and pastry mixes) and science-fiction author, best known for the ''Lensman

The ''Lensman'' series is a series of science fiction novels by American author E. E. "Doc" Smith. It was a runner-up for the 1966 Hugo award for Best All-Time Series, losing to the ''Foundation'' series by Isaac Asimov.

Plot

The series begins ...

'' and ''Skylark

''Alauda'' is a genus of larks found across much of Europe, Asia and in the mountains of north Africa, and one of the species (the Raso lark) endemic to the islet of Raso in the Cape Verde Islands. Further, at least two additional species are ...

'' series. He is sometimes called the father of space opera

Space opera is a subgenre of science fiction that emphasizes space warfare, with use of melodramatic, risk-taking space adventures, relationships, and chivalric romance. Set mainly or entirely in outer space, it features technological and soc ...

.

Biography

Family and education

Edward Elmer Smith was born inSheboygan, Wisconsin

Sheboygan () is a city in and the county seat of Sheboygan County, Wisconsin, United States. The population was 49,929 at the 2020 census. It is the principal city of the Sheboygan, Wisconsin Metropolitan Statistical Area, which has a populati ...

, on May 2, 1890, to Fred Jay Smith and Caroline Mills Smith, both staunch Presbyterians

Presbyterianism is a part of the Reformed tradition within Protestantism that broke from the Roman Catholic Church in Scotland by John Knox, who was a priest at St. Giles Cathedral (Church of Scotland). Presbyterian churches derive their n ...

of British ancestry. His mother was a teacher born in Michigan in February 1855; his father was a sailor, born in Maine

Maine () is a state in the New England and Northeastern regions of the United States. It borders New Hampshire to the west, the Gulf of Maine to the southeast, and the Canadian provinces of New Brunswick and Quebec to the northeast and nor ...

in January 1855 to an English father.1900 Census, House 1515, Residence 438, Family 371, 3rd Ward of Spokane County, Washington, recorded June 13, 1900, accessed via online census images at heritagequest.com They moved to Spokane, Washington

Spokane ( ) is the largest city and county seat of Spokane County, Washington, United States. It is in eastern Washington, along the Spokane River, adjacent to the Selkirk Mountains, and west of the Rocky Mountain foothills, south of the ...

, the winter after Edward Elmer was born, where Mr. Smith was working as a contractor in 1900. In 1902, the family moved to Seneaquoteen,Sanders p. 1. near the Pend Oreille River

The Pend Oreille River ( ) is a tributary of the Columbia River, approximately long, in northern Idaho and northeastern Washington in the United States, as well as southeastern British Columbia in Canada. In its passage through British Columbi ...

, in Kootenai County

Kootenai County ( ) is located in the U.S. state of Idaho. In 2020, the United States Census Bureau estimated the county's population at 171,362, making it the third-most populous county in Idaho and by far the largest in North Idaho, the coun ...

, Idaho. He had four siblings, Rachel M. born September 1882, Daniel M. born January 1884, Mary Elizabeth born February 1886 (all of whom were born in Michigan), and Walter E. born July 1891 in Washington

Washington commonly refers to:

* Washington (state), United States

* Washington, D.C., the capital of the United States

** A metonym for the federal government of the United States

** Washington metropolitan area, the metropolitan area centered o ...

. In 1910, Fred and Caroline Smith and their son Walter were living in the Markham Precinct of Bonner County, Idaho

Bonner County is a county in the northern part of the U.S. state of Idaho. As of the 2020 census, the population was 47,110. The county seat and largest city is Sandpoint. Partitioned from Kootenai County and established in 1907, it was name ...

; Fred is listed in census records as a farmer.

Smith worked mainly as a manual laborer until he injured his wrist while fleeing from a fire at the age of 19. He attended the University of Idaho

The University of Idaho (U of I, or UIdaho) is a public land-grant research university in Moscow, Idaho. It is the state's land-grant and primary research university,, and the lead university in the Idaho Space Grant Consortium. The Universit ...

. (Many years later he would be installed in the 1984 Class of the University of Idaho Alumni Hall of Fame.) He entered its prep school in 1907, and graduated with two degrees in chemical engineering

Chemical engineering is an engineering field which deals with the study of operation and design of chemical plants as well as methods of improving production. Chemical engineers develop economical commercial processes to convert raw materials in ...

in 1914. He was president of the Chemistry Club, the Chess Club, and the Mandolin and Guitar Club, and captain of the Drill and Rifle Team; he also sang the bass lead in Gilbert and Sullivan

Gilbert and Sullivan was a Victorian era, Victorian-era theatrical partnership of the dramatist W. S. Gilbert (1836–1911) and the composer Arthur Sullivan (1842–1900), who jointly created fourteen comic operas between 1871 and 1896, of which ...

operettas. His undergraduate thesis was ''Some Clays of Idaho'', co-written with classmate Chester Fowler Smith, who died in California of tuberculosis

Tuberculosis (TB) is an infectious disease usually caused by '' Mycobacterium tuberculosis'' (MTB) bacteria. Tuberculosis generally affects the lungs, but it can also affect other parts of the body. Most infections show no symptoms, ...

the following year, after taking a teaching fellowship at Berkeley. Whether the two were related is not known.

On October 5, 1915, in Boise, Idaho

Boise (, , ) is the capital and most populous city of the U.S. state of Idaho and is the county seat of Ada County. On the Boise River in southwestern Idaho, it is east of the Oregon border and north of the Nevada border. The downtown ar ...

he married Jeanne Craig MacDougall, the sister of his college roommate, Allen Scott (Scotty) MacDougall. (Her sister was named Clarissa MacLean MacDougall; the heroine of the ''Lensman'' novels would later be named Clarissa MacDougall.) Jeanne MacDougall was born in Glasgow

Glasgow ( ; sco, Glesca or ; gd, Glaschu ) is the most populous city in Scotland and the fourth-most populous city in the United Kingdom, as well as being the 27th largest city by population in Europe. In 2020, it had an estimated popu ...

, Scotland; her parents were Donald Scott MacDougall, a violinist, and Jessica Craig MacLean. Her father had moved to Boise when the children were young, and later sent for his family; he died while they were en route in 1905. Jeanne's mother, who remarried businessman and retired politician John F. Kessler in 1914 worked at, and later owned, a boarding house on Ridenbaugh Street.

The Smiths had three children:

* Roderick N., born June 3, 1918, in the District of Columbia

)

, image_skyline =

, image_caption = Clockwise from top left: the Washington Monument and Lincoln Memorial on the National Mall, United States Capitol, Logan Circle (Washington, D.C.), Logan Circle, Jefferson Memoria ...

, was employed as a design engineer at Lockheed Aircraft.

* Verna Jean (later Verna Smith Trestrail), born August 25, 1920, in Michigan, was his literary executor until her death in 1994. (Her son Kim Trestrail is now the executor.) Robert A. Heinlein

Robert Anson Heinlein (; July 7, 1907 – May 8, 1988) was an American science fiction author, aeronautical engineer, and naval officer. Sometimes called the "dean of science fiction writers", he was among the first to emphasize scientific accu ...

in part dedicated his 1982 novel ''Friday

Friday is the day of the week between Thursday and Saturday. In countries that adopt the traditional "Sunday-first" convention, it is the sixth day of the week. In countries adopting the ISO-defined "Monday-first" convention, it is the fifth d ...

'' to Verna.

* Clarissa M. (later Clarissa Wilcox), was born December 13, 1921, in Michigan.

Early chemical career and the beginning of ''Skylark''

After college, Smith was a junior

After college, Smith was a junior chemist

A chemist (from Greek ''chēm(ía)'' alchemy; replacing ''chymist'' from Medieval Latin ''alchemist'') is a scientist trained in the study of chemistry. Chemists study the composition of matter and its properties. Chemists carefully describe th ...

for the National Bureau of Standards

The National Institute of Standards and Technology (NIST) is an agency of the United States Department of Commerce whose mission is to promote American innovation and industrial competitiveness. NIST's activities are organized into physical sci ...

in Washington, D.C., developing standards for butter and for oysters, while studying food chemistry at George Washington University. During World War I, he "wanted to fly a Jenny, but chemists were too scarce. (Or were Jennies too valuable?)" He ended up being sent to the Commission for Relief in Belgium

The Commission for Relief in Belgium or C.R.B. − known also as just Belgian Relief − was an international (predominantly American) organization that arranged for the supply of food to German-occupied Belgium and northern France during the Wor ...

headed by Herbert Hoover. His draft card, partly illegible, seems to show that Smith requested exemption from military service, based on his wife's dependence and on his contribution to the war effort as a civilian chemist.

One evening in 1915, the Smiths were visiting a former classmate from the University of Idaho

The University of Idaho (U of I, or UIdaho) is a public land-grant research university in Moscow, Idaho. It is the state's land-grant and primary research university,, and the lead university in the Idaho Space Grant Consortium. The Universit ...

, Dr. Carl Garby (1890-1928) who had also moved to Washington, D.C. He lived nearby in the Seaton Place Apartments with his wife, Lee Hawkins Garby. A long discussion about journeys into outer space ensued, and it was suggested that Smith should write down his ideas and speculations as a story about interstellar travel. Although he was interested, Smith believed after some thought that some romantic elements would be required and he was uncomfortable with that.

Mrs. Garby offered to take care of the love interest and the romantic dialogue, and Smith decided to give it a try. The sources of inspirations for the main characters in the novel were themselves; the "Seatons" and "Cranes" were based on the Smiths and Garbys, respectively. About one third of ''The Skylark of Space

''The Skylark of Space'' is a science fiction novel by American writer Edward E. "Doc" Smith, written between 1915 and 1921 while Smith was working on his doctorate. Though the original idea for the novel was Smith's, he co-wrote the first part o ...

'' was completed by the end of 1916, when Smith and Garby gradually abandoned work on it.

Smith earned his master's degree in chemistry from the George Washington University

, mottoeng = "God is Our Trust"

, established =

, type = Private federally chartered research university

, academic_affiliations =

, endowment = $2.8 billion (2022)

, presi ...

in 1917, studying under Dr. Charles E. Munroe., who Smith called "probably the greatest high-explosives man yet to live." Smith completed his PhD in chemical engineering in 1918, with a food engineering focus; his dissertation, The effect of bleaching with oxides of nitrogen upon the baking quality and commercial value of wheat flour

', was published in 1919. (Warner and Fleischer give the title ''The Effect of the Oxides of Nitrogen upon the Carotin Molecule – C40H56'', which is difficult to explain.

Sam Moskowitz

Sam Moskowitz (June 30, 1920 – April 15, 1997) was an American writer, critic, and historian of science fiction.

Biography

As a child, Moskowitz greatly enjoyed reading science fiction pulp magazines. As a teenager, he organized a branch of ...

gives the degree date 1919,Moskowitz, p. 13. perhaps reflecting different dates for thesis submission, thesis defense, and degree certification.)

Writing ''Skylark''

In 1919, Smith was hired as chief chemist for F. W. Stock & Sons ofHillsdale, Michigan

Hillsdale is the largest city and county seat of Hillsdale County in the U.S. state of Michigan. The population was 8,036 at the 2020 census.

The city is the home of Hillsdale College, a private liberal arts college noted for its academics ...

, at one time the largest family-owned mill east of the Mississippi, working on doughnut mixes.

One evening late in 1919, after moving to Michigan, Smith was baby-sitting (presumably for Roderick) while his wife attended a movie; he resumed work on ''The Skylark of Space'', finishing it in the spring of 1920. He submitted it to many book publishers and magazines, spending more in postage than he would eventually receive for its publication. Bob Davis, editor of '' Argosy'', sent an encouraging rejection letter in 1922, saying that he liked the novel personally, but that it was too far out for his readers. (According tWarner

but no other source, Smith began work on the sequel, ''Skylark Three'', before the first book was accepted.) Finally, upon seeing the April 1927 issue of ''

Amazing Stories

''Amazing Stories'' is an American science fiction magazine launched in April 1926 by Hugo Gernsback's Experimenter Publishing. It was the first magazine devoted solely to science fiction. Science fiction stories had made regular appearances ...

'', he submitted it to that magazine; it was accepted, initially for $75, later raised to $125. It was published as a three-part serial in the August to October 1928 issues and it was such a success that associate editor Sloane requested a sequel before the second installment had been published.

Mrs. Garby, whose husband died in 1928, was not interested in further collaboration, so Smith began work on ''Skylark Three'' alone. It was published as another three-part serial, in the August to October 1930 issues of ''Amazing'', introduced as the cover story for August. (In 1930, the Smiths were living in Michigan, at 33 Rippon Avenue in Hillsdale.) This was as far as he had planned to take the ''Skylark'' series; it was praised in ''Amazing''s letter column, and he was paid ¾¢ per word, surpassing ''Amazing''s previous record of half a cent.Moskowitz p. 16

The early 1930s: between ''Skylark'' and ''Lensman''

Smith then began work on what he intended as a new series, starting with '' Spacehounds of IPC,'' which he finished in the autumn of 1930. In this novel, he took pains to avoid the scientific impossibilities which had bothered some readers of the ''Skylark'' novels. Even in 1938, after he had written ''Galactic Patrol'', Smith considered it his finest work; he later said of it, "This was really scientific fiction; not, like the Skylarks, pseudo-science"; and even at the end of his career, he considered it his only work of true science fiction. It was published in the July through September 1931 issues of ''Amazing,'' with Sloane making unauthorized changes. Fan letters in the magazine complained about the novel's containment within the solar system, and Sloane sided with the readers. So when Harry Bates, editor of ''Astounding Stories

''Analog Science Fiction and Fact'' is an American science fiction magazine published under various titles since 1930. Originally titled ''Astounding Stories of Super-Science'', the first issue was dated January 1930, published by William C ...

'', offered Smith 2¢/word—payable on publication—for his next story, he agreed; this meant that it could not be a sequel to ''Spacehounds.''

This book would be ''Triplanetary

''Triplanetary'' is a science fiction board wargame originally published by Game Designers' Workshop in 1973. The game is a simulation of space ship travel and combat within the Solar System in the early 21st Century.

History First edition

''T ...

'', "in which scientific detail would not be bothered about, and in which his imagination would run riot."Warner. Indeed, characters within the story point out its psychological and scientific implausibilities, and sometimes even seem to suggest self-parody. At other times, they are conspicuously silent about obvious implausibilities. The January 1933 issue of ''Astounding'' announced that ''Triplanetary'' would appear in the March issue, and that issue's cover illustrated a scene from the story, but ''Astounding''s financial difficulties prevented the story from appearing. Smith then submitted the manuscript to ''Wonder Stories

''Wonder Stories'' was an early American science fiction magazine which was published under several titles from 1929 to 1955. It was founded by Hugo Gernsback in 1929 after he had lost control of his first science fiction magazine, ''Amazing Stor ...

'', whose new editor, 17-year-old Charles D. Hornig, rejected it, later boasting about the rejection in a fanzine

A fanzine (blend of '' fan'' and ''magazine'' or ''-zine'') is a non-professional and non-official publication produced by enthusiasts of a particular cultural phenomenon (such as a literary or musical genre) for the pleasure of others who share ...

. He finally submitted it to ''Amazing'', which published it beginning in January 1934, but for only half a cent a word. Shortly after it was accepted, F. Orlin Tremaine

Frederick Orlin Tremaine (January 7, 1899 – October 22, 1956) was an American science fiction magazine editor, most notably of the influential ''Astounding Stories''. He edited a number of other magazines, headed several publishing companies ...

, the new editor of the revived ''Astounding'', offered one cent a word for ''Triplanetary''; when he learned that he was too late, he suggested a third ''Skylark'' novel instead.

In the winter of 1933–34, Smith worked on ''The Skylark of Valeron'', but he felt that the story was getting out of control; he sent his first draft to Tremaine, with a distraught note asking for suggestions. Tremaine accepted the rough draft for $850, and announced it in the June 1934 issue, with a full-page editorial and a three-quarter-page advertisement. The novel was published in the August 1934 through February 1935 issues. ''Astounding'''s circulation rose by 10,000 for the first issue, and its two main competitors, '' Amazing'' and ''Wonder Stories

''Wonder Stories'' was an early American science fiction magazine which was published under several titles from 1929 to 1955. It was founded by Hugo Gernsback in 1929 after he had lost control of his first science fiction magazine, ''Amazing Stor ...

'', fell into financial difficulties, both skipping issues within a year.

The ''Lensman'' series

In January 1936, a time period where he was already an established science-fiction writer, he took a job for salary plus profit-sharing, as production manager at Dawn Donut Co. ofJackson, Michigan

Jackson is the only city and county seat of Jackson County in the U.S. state of Michigan. As of the 2010 census, the city population was 33,534, down from 36,316 at the 2000 census. Located along Interstate 94 and U.S. Route 127, it is approx ...

. This initially entailed almost a year's worth of 18-hour days and seven-day workweeks. Individuals who knew Smith confirmed that he had a role in developing mixes for doughnuts and other pastries, but the contention that he developed the first process for making powdered sugar adhere to doughnuts cannot be substantiated. Smith was reportedly dislocated from his job at Dawn Donuts by prewar rationing in early 1940.The Dictionary of Literary Biography, quoted at http://www.bookrags.com/Edward_Elgar accessed May 8, 2007.

Smith had been contemplating writing a "space-police novel" since early 1927; once he had "the Lensmen's universe fairly well set up", he reviewed his science-fiction collection for "cops-and-robbers" stories. He cites Clinton Constantinescue's "War of the Universe" as a negative example, and Starzl and Williamson as positive ones. Tremaine responded extremely positively to a brief description of the idea.

Once Dawn Donuts became profitable in late 1936, Smith wrote an 85-page outline for what became the four core ''Lensman

The ''Lensman'' series is a series of science fiction novels by American author E. E. "Doc" Smith. It was a runner-up for the 1966 Hugo award for Best All-Time Series, losing to the ''Foundation'' series by Isaac Asimov.

Plot

The series begins ...

'' novels; in early 1937, Tremaine committed to buying them. Segmenting the story into four novels required considerable effort to avoid dangling loose ends; Smith cites Edgar Rice Burroughs

Edgar Rice Burroughs (September 1, 1875 – March 19, 1950) was an American author, best known for his prolific output in the adventure, science fiction, and fantasy genres. Best-known for creating the characters Tarzan and John Carter, ...

as a negative example."The Epic of Space" p. 85. After the outline was complete, he wrote a more detailed outline of ''Galactic Patrol

The Galactic Patrol was an intergalactic organization in the ''Lensman'' science fiction series written by E. E. Smith. It was also the title of the third book in the series.

Overview

In the Lensman novels, the Galactic Patrol was a combination ...

'', plus a detailed graph of its structure, with "peaks of emotional intensity and the valleys of characterization and background material." He notes, however, that he was never able to follow any of his outlines at all closely, as the "characters get away from me and do exactly as they damn please." After completing the rough draft of ''Galactic Patrol'', he wrote the concluding chapter of the last book in the series, '' Children of the Lens.'' ''Galactic Patrol'' was published in the September 1937 through February 1938 issues of ''Astounding''; unlike the revised book edition, it was not set in the same universe as ''Triplanetary''.

''Gray Lensman

''Gray Lensman'' is a science fiction novel by American writer E. E. Smith. It was first published in book form in 1951 by Fantasy Press in an edition of 5,096 copies. The novel was originally serialized in the magazine ''Astounding'' in 1939.

G ...

'', the fourth book in the series, appeared in ''Astounding''s October 1939 through January 1940 issues. (Note that the frequent British spelling "grey" is simply a recurrent mistake, starting with the cover of the first installment; Moskowitz's usage, ''"The Grey Lensman",'' is even harder to justify.) ''Gray Lensman'' (and itcover illustration

was extremely well received. Campbell's editorial in the December issue suggested that the October issue was the best issue of ''Astounding'' ever, and ''Gray Lensman'' was first place in the Analytical Laboratory statistics "by a lightyear", with three runners-up in a distant tie for second place. The cover was also praised by readers in ''Brass Tacks'', and Campbell noted, "We got a letter from E. E. Smith saying he and over artistHubert Rogers agreed on how Kinnison looked." Smith was the guest of honor at Chicon I, the second

World Science Fiction Convention

Worldcon, or more formally the World Science Fiction Convention, the annual convention of the World Science Fiction Society (WSFS), is a science fiction convention. It has been held each year since 1939 (except for the years 1942 to 1945, durin ...

, held in Chicago over Labor Day weekend 1940, giving a speech on the importance of science fiction fandom

Science fiction fandom or SF fandom is a community or fandom of people interested in science fiction in contact with one another based upon that interest. SF fandom has a life of its own, but not much in the way of formal organization (although ...

entitled "What Does This Convention Mean?" He attended the convention's masquerade as C. L. Moore

Catherine Lucille Moore (January 24, 1911 – April 4, 1987) was an American science fiction and fantasy writer, who first came to prominence in the 1930s writing as C. L. Moore. She was among the first women to write in the science fiction and ...

's Northwest Smith

Northwest Smith is a fictional character, and the hero of a series of stories by science fiction writer C. L. Moore.

Story setting

Smith is a spaceship pilot and smuggler who lives in an undisclosed future time when humanity has colonized the ...

, and met fans living near him in Michigan, who would later form the Galactic Roamers, which previewed and advised him on his future work.

After Pearl Harbor

Pearl Harbor is an American lagoon harbor on the island of Oahu, Hawaii, west of Honolulu. It was often visited by the Naval fleet of the United States, before it was acquired from the Hawaiian Kingdom by the U.S. with the signing of the ...

, Smith discovered he "was one year over age for reinstatement" into the US Army. Instead he worked on high explosives at the Kingsbury Ordnance Plant in La Port, Indiana, at first as a chemical engineer, but gradually worked his way up to chief. In late 1943 he became head of the Inspection Division, and was fired in early 1944. An extended segment in the novel version of ''Triplanetary'', set during World War II, suggests intimate familiarity with explosives and munitions manufacturing. Some biographers cite as fact that, just as Smith's protagonist in this segment lost his job over failure to approve substandard munitions, Smith did as well.

Smith spent the next few years working on "light farm machinery and heavy tanks for Allis-Chalmers," after which he was hired as manager of the Cereal Mix Division of J. W. Allen & Co., where he worked until his professional retirement in 1957.

Retirement and late writing

After Smith retired, his wife and he lived inClearwater, Florida

Clearwater is a city located in Pinellas County, Florida, United States, northwest of Tampa and St. Petersburg. To the west of Clearwater lies the Gulf of Mexico and to the southeast lies Tampa Bay. As of the 2020 census, the city had a popu ...

, in the fall and winter, driving the smaller of their two trailers to Seaside, Oregon

Seaside is a city in Clatsop County, Oregon, United States, on the coast of the Pacific Ocean. The name Seaside is derived from ''Seaside House'', a historic summer resort built in the 1870s by railroad magnate Ben Holladay. The city's population ...

, each April, often stopping at science fiction convention

Science fiction conventions are gatherings of fans of the speculative fiction genre, science fiction. Historically, science fiction conventions had focused primarily on literature, but the purview of many extends to such other avenues of expre ...

s on the way. (Smith did not like to fly.) In 1963, he was presented the inaugural First Fandom Hall of Fame award

First Fandom Hall of Fame is an annual award for contributions to the field of science fiction dating back more than 30 years. Contributions can be as a fan, writer, editor, artist, agent, or any combination of the five. It is awarded by First Fa ...

at the 21st World Science Fiction Convention in Washington, D.C. Some of his biography is captured in an essay by Robert A. Heinlein

Robert Anson Heinlein (; July 7, 1907 – May 8, 1988) was an American science fiction author, aeronautical engineer, and naval officer. Sometimes called the "dean of science fiction writers", he was among the first to emphasize scientific accu ...

, which was reprinted in the collection ''Expanded Universe'' in 1980. A more detailed, although allegedly error-ridden biography is in Sam Moskowitz's ''Seekers of Tomorrow.''

Robert Heinlein and Smith were friends. (Heinlein dedicated his 1958 novel ''Methuselah's Children

''Methuselah's Children'' is a science fiction novel by American writer Robert A. Heinlein. Originally serialized in ''Astounding Science Fiction'' in the July, August, and September 1941 issues, it was expanded into a full-length novel in 1958. ...

'' "To Edward E. Smith, PhD".) Heinlein reported that E. E. Smith perhaps took his "unrealistic" heroes from life, citing as an example the extreme competence of the hero of '' Spacehounds of IPC''. He reported that E. E. Smith was a large, blond, athletic, very intelligent, very gallant man, married to a remarkably beautiful, intelligent, red-haired woman named MacDougal (thus perhaps the prototypes of 'Kimball Kinnison' and 'Clarissa MacDougal'). In Heinlein's essay, he reports that he began to suspect Smith might be a sort of "superman" when he asked Smith for help in purchasing a car. Smith tested the car by driving it on a back road at illegally high speeds with their heads pressed tightly against the roof columns to listen for chassis squeaks by bone conduction

Bone conduction is the conduction of sound to the inner ear primarily through the bones of the skull, allowing the hearer to perceive audio content without blocking the ear canal. Bone conduction transmission occurs constantly as sound waves vibra ...

—a process apparently improvised on the spot.

In his nonseries novels written after his professional retirement, ''Galaxy Primes'', ''Subspace Explorers'', and ''Subspace Encounter'', E. E. Smith explores themes of telepathy and other mental abilities collectively called "psionics", and of the conflict between libertarian

Libertarianism (from french: libertaire, "libertarian"; from la, libertas, "freedom") is a political philosophy that upholds liberty as a core value. Libertarians seek to maximize autonomy and political freedom, and minimize the state's en ...

and socialistic/communistic influences in the colonization of other planets. ''Galaxy Primes'' was written after critics such as Groff Conklin

Edward Groff Conklin (September 6, 1904 – July 19, 1968) was an American science fiction anthologist. He edited 40 anthologies of science fiction, one of mystery stories (co-edited with physician Noah Fabricant), wrote books on home improvemen ...

and P. Schuyler Miller in the early '50s accused his fiction of being passé, and he made an attempt to do something more in line with the concepts about which ''Astounding'' editor John W. Campbell encouraged his writers to make stories. Despite this, it was rejected by Campbell, and it was eventually published by ''Amazing Stories'' in 1959. His late story "The Imperial Stars" (1964), featuring a troupe of circus performers involved in sabotage in a galactic empire, recaptured some of the atmosphere from his earlier works and was intended as the first in a new series, with outlines of later parts rumored to still exist. In fact, the Imperial Stars characters and concepts were continued by author Stephen Goldin

Stephen Charles Goldin (born February 28, 1947) is an American science fiction and fantasy author.

Biography

Goldin was born in Philadelphia, Pennsylvania.

A graduate of UCLA with a bachelor's degree in Astronomy, he worked for the U.S. Nav ...

as the "Family D'Alembert

The Family D'Alembert series is a set of science fiction novels by Stephen Goldin

Stephen Charles Goldin (born February 28, 1947) is an American science fiction and fantasy author.

Biography

Goldin was born in Philadelphia, Pennsylvania.

A ...

series". While the book covers indicate the series was written by Smith and Goldin together, Goldin only ever had Smith's original novella to expand upon.

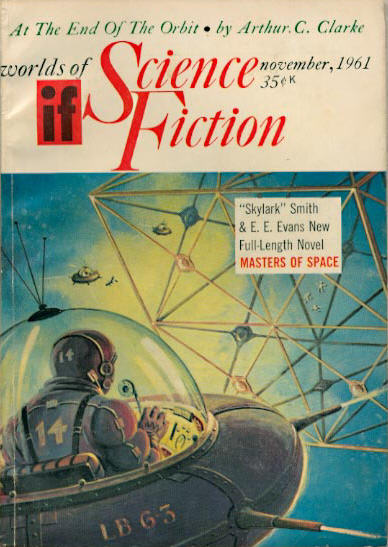

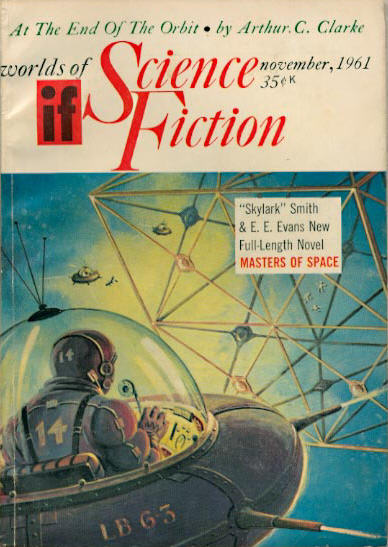

The fourth ''Skylark'' novel, ''Skylark DuQuesne

''Skylark DuQuesne'' is a science fiction novel by American writer E. E. Smith, the final novel in his ''Skylark'' series. Written as Smith's last novel in 1965 and published shortly before his death, it expands on the characterizations of the e ...

'', ran in the June to October 1965 issues of ''If'', beginning once again as the cover story. Editor Frederik Pohl

Frederik George Pohl Jr. (; November 26, 1919 – September 2, 2013) was an American science-fiction writer, editor, and fan, with a career spanning nearly 75 years—from his first published work, the 1937 poem "Elegy to a Dead Satellit ...

introduced it with a one-page summary of the previous stories, which were all at least 30 years old.

Lord Tedric

Smith published two novelettes entitled "Tedric" in ''Other Worlds Science Fiction Stories'' (1953) and "Lord Tedric" in ''Universe Science Fiction'' (1954). These were almost completely forgotten until after Smith's death. In 1975, a compendium of Smith's works was published, entitled ''The Best of E. E. "Doc" Smith'', containing these two short stories, excerpts from several of his major works, and another short story first published in ''Worlds of If'' in 1964 entitled "The Imperial Stars". In Smith's original short stories, Tedric was a smith (both blacksmith and whitesmith) residing in a small town near a castle in a situation roughly equivalent to England of the 1200s. He received instruction in advanced metallurgy from atime-travel

Time travel is the concept of movement between certain points in time, analogous to movement between different points in space by an object or a person, typically with the use of a hypothetical device known as a time machine. Time travel is a ...

er who wanted to change the situation in his own time by modifying certain events of the past. From this instruction, he was able to build better suits of armor and help defeat the villains of the piece. Unlike Eklund's later novels based on these short stories, the original Tedric never left his own time or planet, and fought purely local enemies of his own time period.

A few years later and 13 years after Smith's death, Verna Smith arranged with Gordon Eklund

Gordon Eklund (born July 24, 1945 in Seattle, Washington) is an American science fiction author whose works include the "Lord Tedric" series and two of the earliest original novels based on the 1960s ''Star Trek'' TV series. He has written under th ...

to publish another novel of the same name about the same fictional character, introducing it as "a new series conceived by E. E. 'Doc' Smith". Eklund later went on to publish the other novels in the series, one or two under the pseudonym "E. E. 'Doc' Smith" or "E. E. Smith". The protagonist possesses heroic qualities similar to those of the heroes in Smith's original novels and can communicate with an extra-dimensional race of beings known as the Scientists, whose archenemy is Fra Villion, a mysterious character described as a dark knight, skilled in whip-sword combat, and evil genius behind the creation of a planetoid-sized "iron sphere" armed with a weapon capable of destroying planets. As a result, Smith is believed by many to be the unacknowledged progenitor of themes that would appear in ''Star Wars

''Star Wars'' is an American epic space opera multimedia franchise created by George Lucas, which began with the eponymous 1977 film and quickly became a worldwide pop-culture phenomenon. The franchise has been expanded into various film ...

''. In fact, however, these appear in the sequels written by others after Smith's death.

Critical opinion

Smith's novels are generally considered to be classicspace opera

Space opera is a subgenre of science fiction that emphasizes space warfare, with use of melodramatic, risk-taking space adventures, relationships, and chivalric romance. Set mainly or entirely in outer space, it features technological and soc ...

s, and he is sometimes called the first of the three "nova

A nova (plural novae or novas) is a transient astronomical event that causes the sudden appearance of a bright, apparently "new" star (hence the name "nova", which is Latin for "new") that slowly fades over weeks or months. Causes of the dramat ...

s" of 20th-century science fiction (with Stanley G. Weinbaum

Stanley Grauman Weinbaum (April 4, 1902 – December 14, 1935) was an American science fiction writer. His first story, "A Martian Odyssey", was published to great acclaim in July 1934; the alien Tweel was arguably the first character to satisf ...

and Robert A. Heinlein

Robert Anson Heinlein (; July 7, 1907 – May 8, 1988) was an American science fiction author, aeronautical engineer, and naval officer. Sometimes called the "dean of science fiction writers", he was among the first to emphasize scientific accu ...

as the second and third novas).

Heinlein credited him for being his main influence:

I have learned from many writers—from Verne and Wells and Campbell andSmith expressed a preference for inventing fictional technologies that were not strictly impossible (so far as the science of the day was aware) but highly unlikely: "the more highly improbable a concept is—short of being contrary to mathematics whose fundamental operations involve no neglect of infinitesimals—the better I like it" was his phrase. ''Lensman'' was one of five finalists when the 1966Sinclair Lewis Harry Sinclair Lewis (February 7, 1885 – January 10, 1951) was an American writer and playwright. In 1930, he became the first writer from the United States (and the first from the Americas) to receive the Nobel Prize in Literature, which was ..., et al.—but I have learned more from you than from any of the others and perhaps more than for all the others put together...

World Science Fiction Convention

Worldcon, or more formally the World Science Fiction Convention, the annual convention of the World Science Fiction Society (WSFS), is a science fiction convention. It has been held each year since 1939 (except for the years 1942 to 1945, durin ...

judged Isaac Asimov's ''Foundation'' the Best All-Time Series.

The Science Fiction and Fantasy Hall of Fame

The Museum of Pop Culture or MoPOP is a nonprofit museum in Seattle, Washington, dedicated to contemporary popular culture. It was founded by Microsoft co-founder Paul Allen in 2000 as the Experience Music Project. Since then MoPOP has organ ...

inducted Smith in 2004.

This was the official website of the hall of fame to 2004.

Extending the ''Lensman'' universe

''Vortex Blasters'' (also known as ''Masters of the Vortex'') is set in the same universe as the ''Lensman'' novels. It is an extension to the main storyline which takes place between ''Galactic Patrol'' and ''Children of the Lens'', and introduces a different type of psionics from that used by the Lensmen. ''Spacehounds of IPC'' is not a part of the series, despite occasional erroneous statements to the contrary. (It is listed as a novel in the series in some paperback editions of the 1970s.)Influence on science and the military

Smith was widely read by scientists and engineers from the 1930s into the 1970s. Literary precursors of ideas which arguably entered the military-scientific complex include SDI (''Triplanetary''),stealth

Stealth may refer to:

Military

* Stealth technology, technology used to conceal ships, aircraft, and missiles

** Stealth aircraft, aircraft which use stealth technology

**Stealth ground vehicle, ground vehicles which use stealth technology

** St ...

(''Gray Lensman''), the OODA loop

The OODA loop is the cycle ''observe–orient–decide–act'', developed by military strategist and United States Air Force Colonel John Boyd. Boyd applied the concept to the combat operations process, often at the operational level during m ...

, C3-based warfare, and the AWACS (''Gray Lensman'').

An inarguable influence was described in a June 11, 1947, letter to Smith from John W. Campbell (the editor of ''Astounding'', where much of the ''Lensman'' series was originally published). In it, Campbell relayed Captain Cal Laning

Rear Admiral Caleb Barrett Laning (born 27 March 1906, Kansas City, Missouri; died 31 May 1991, Falls Church, Virginia) was a highly decorated naval officer, writer, and technical adviser. Laning is buried in Arlington National Cemetery.

He was t ...

's acknowledgment that he had used Smith's ideas for displaying the battlespace situation (called the "tank" in the stories) in the design of the United States Navy

The United States Navy (USN) is the maritime service branch of the United States Armed Forces and one of the eight uniformed services of the United States. It is the largest and most powerful navy in the world, with the estimated tonnage ...

's ships' Combat Information Centers. "The entire set-up was taken specifically, directly, and consciously from the ''Directrix''. In your story, you reached the situation the Navy was in—more communication channels than integration techniques to handle it. You proposed such an integrating technique and proved how advantageous it could be. You, sir, were 100% right. As the Japanese Navy—not the hypothetical Boskonian fleet—learned at an appalling cost."

One underlying theme of the later ''Lensman'' novels was the difficulty in maintaining military secrecy—as advanced capabilities are revealed, the opposing side can often duplicate them. This point was also discussed extensively by John Campbell in his letter to Smith. Also in the later ''Lensman'' novels, and particular after the "Battle of Klovia" broke the Boskonian's power base at the end of ''Second Stage Lensmen'', the Boskonian forces and particularly Kandron of Onlo reverted to terroristic tactics to attempt to demoralize Civilization, thus providing an early literary glimpse into this modern problem of both law enforcement and military response. The use of "Vee-two" gas by the pirates attacking the ''Hyperion'' in ''Triplanetary'' (in both magazine and book appearances) also suggests anticipation of the terrorist uses of poison gases. (But note that Smith lived through WW I, when the use of poison gas on troops was well known to the populace; extending the assumption that pirates might use it if they could obtain it was no great extension of the present-day knowledge.)

The beginning of the story ''Skylark of Space'' describes in relative detail the protagonist's research into separation of platinum group residues, subsequent experiments involving electrolysis, and the discovery of a process evocative of cold fusion

Cold fusion is a hypothesized type of nuclear reaction that would occur at, or near, room temperature. It would contrast starkly with the "hot" fusion that is known to take place naturally within stars and artificially in hydrogen bombs and p ...

(over 50 years before Stanley Pons and Martin Fleischmann

Martin Fleischmann FRS (29 March 1927 – 3 August 2012) was a British chemist who worked in electrochemistry.

By Associated Press.

Premature announcement of his cold fusion research with Stanley Pons, regarding excess heat in heavy ...

). He describes a nuclear process yielding large amounts of energy and producing only negligible radioactive waste—which then goes on to form the basis of the adventures in the Skylark books. Smith's general description of the process of discovery is highly evocative of Röntgen's descriptions of his discovery of the X-ray

An X-ray, or, much less commonly, X-radiation, is a penetrating form of high-energy electromagnetic radiation. Most X-rays have a wavelength ranging from 10 picometers to 10 nanometers, corresponding to frequencies in the range 30&nb ...

.

Another theme of the ''Skylark'' novels involves precursors of modern information technology. The humanoid aliens encountered in the first novel have developed a primitive technology called the "mechanical educator", which allows direct conversion of brain waves into intelligible thought for transmission to others or for electrical storage. By the third novel in the series, ''Skylark of Valeron'', this technology has grown into an "Electronic Brain" which is capable of computation on all "bands" of energy—electromagnetism, gravity, and "tachyonic" energy and radiation bands included. This is itself derived from a discussion of reductionist atomic theory in the second novel, ''Skylark Three'', which brings to mind modern quark and sub-quark theories of elementary particle physics.

Literary influences

In his 1947 essay "The Epic of Space", Smith listed (by last name only) authors he enjoyed reading: John W. Campbell, L. Sprague de Camp, Robert A. Heinlein,Murray Leinster

Murray Leinster (June 16, 1896 – June 8, 1975) was a pen name of William Fitzgerald Jenkins, an American writer of genre fiction, particularly of science fiction. He wrote and published more than 1,500 short stories and articles, 14 movie ...

, H. P. Lovecraft, and A. Merritt (specifically ''The Ship of Ishtar

''The Ship of Ishtar'' is a fantasy novel by American writer A. Merritt. Originally published as a magazine serial in 1924, it has appeared in book form innumerable times. The novel depicts a modern archaeologist who has to intervene in an etern ...

'', '' The Moon Pool'', '' The Snake Mother'', and '' Dwellers in the Mirage'', as well as the character John Kenton), C. L. Moore

Catherine Lucille Moore (January 24, 1911 – April 4, 1987) was an American science fiction and fantasy writer, who first came to prominence in the 1930s writing as C. L. Moore. She was among the first women to write in the science fiction and ...

(specifically "Jirel of Joiry

Jirel of Joiry is a fictional character created by American writer C. L. Moore, who appeared in a series of sword and sorcery stories published first in the pulp horror/fantasy magazine ''Weird Tales''. Jirel is the proud, tough, arrogant and b ...

"), Roman Frederick Starzl, John Taine

Eric Temple Bell (7 February 1883 – 21 December 1960) was a Scottish-born mathematician and science fiction writer who lived in the United States for most of his life. He published non-fiction using his given name and fiction as John Tain ...

, A. E. van Vogt, Stanley G. Weinbaum

Stanley Grauman Weinbaum (April 4, 1902 – December 14, 1935) was an American science fiction writer. His first story, "A Martian Odyssey", was published to great acclaim in July 1934; the alien Tweel was arguably the first character to satisf ...

(specifically "Tweerl"), and Jack Williamson

John Stewart Williamson (April 29, 1908 – November 10, 2006), who wrote as Jack Williamson, was an American science fiction writer, often called the "Dean of Science Fiction". He is also credited with one of the first uses of the term ''genet ...

. In a passage on his preparation for writing the ''Lensman'' novels, he notes that Clinton Constantinescu's "War of the Universe" was not a masterpiece, but says that Starzl and Williamson were masters; this suggests that Starzl's Interplanetary Flying Patrol may have been an influence on Smith's Triplanetary Patrol, later the ''Galactic Patrol''. The feeding of the Overlords of Delgon upon the life-force of their victims at the end of chapter five of ''Galactic Patrol'' seems a clear allusion to chapter 29 of ''The Moon Pool'', Merritt's account of the Taithu and the power of love in chapters 29 and 34 also bear some resemblance to the end of ''Children of the Lens.'' Smith also mentions Edgar Rice Burroughs

Edgar Rice Burroughs (September 1, 1875 – March 19, 1950) was an American author, best known for his prolific output in the adventure, science fiction, and fantasy genres. Best-known for creating the characters Tarzan and John Carter, ...

, complaining about loose ends at the end of one of his novels.

Smith acknowledges the help of the Galactic Roamers writers' workshop, plus E. Everett Evans

Edward Everett Evans (November 30, 1893 – December 2, 1958) was an American science fiction writer and fan.

He married science-fiction author Thelma D. Hamm in 1953.

His works include the novels '' Man of Many Minds'' (1953), ''The Planet Ma ...

, Ed Counts, an unnamed aeronautical engineer, Dr. James Enright, and Dr. Richard W. Dodson. Smith's daughter, Verna, lists the following authors as visitors to the Smith household in her youth: Lloyd Arthur Eshbach

Lloyd Arthur Eshbach (June 20, 1910 – October 29, 2003) was an American science fiction fan, publisher and writer, secular and religious publisher, and minister.

Biography

Born in Palm, Pennsylvania, Eshbach grew up in Reading in the sa ...

, Heinlein, Dave Kyle

David A. Kyle (February 14, 1919 – September 18, 2016) was an American science fiction writer and member of science fiction fandom.

Professional career

Kyle served as a reporter in the Air Force Reserves with the rank of lieutenant colonel, wr ...

, Bob Tucker, Williamson, Pohl, Merritt, and the Galactic Roamers. Smith cites Bigelow's ''Theoretical Chemistry–Fundamentals'' as a justification for the possibility of the inertialess drive

The inertialess drive is a fictional means of accelerating to close to the speed of light or faster-than-light travel, originally used in ''Triplanetary (novel), Triplanetary'' and the ''Lensman'' series by E. E. Smith, E.E. "Doc" Smith, and later ...

. Also, an extended reference is made to Rudyard Kipling

Joseph Rudyard Kipling ( ; 30 December 1865 – 18 January 1936)'' The Times'', (London) 18 January 1936, p. 12. was an English novelist, short-story writer, poet, and journalist. He was born in British India, which inspired much of his work.

...

'sBallad of Boh Da Thone

in ''Gray Lensman'' (chapter 22, "Regeneration", in a conversation between Kinnison and MacDougall). Again in ''Gray Lensman'', Smith quotes from Merritt's ''Dwellers in the Mirage'', even name-checking the author:

Sam Moskowitz

Sam Moskowitz (June 30, 1920 – April 15, 1997) was an American writer, critic, and historian of science fiction.

Biography

As a child, Moskowitz greatly enjoyed reading science fiction pulp magazines. As a teenager, he organized a branch of ...

's biographical essay on Smith in ''Seekers of Tomorrow'' states that he regularly read '' Argosy'' magazine, and everything by H. G. Wells, Jules Verne

Jules Gabriel Verne (;''Longman Pronunciation Dictionary''. ; 8 February 1828 – 24 March 1905) was a French novelist, poet, and playwright. His collaboration with the publisher Pierre-Jules Hetzel led to the creation of the '' Voyages extra ...

, H. Rider Haggard

Sir Henry Rider Haggard (; 22 June 1856 – 14 May 1925) was an English writer of adventure fiction romances set in exotic locations, predominantly Africa, and a pioneer of the lost world literary genre. He was also involved in land reform t ...

, Edgar Allan Poe

Edgar Allan Poe (; Edgar Poe; January 19, 1809 – October 7, 1849) was an American writer, poet, editor, and literary critic. Poe is best known for his poetry and short stories, particularly his tales of mystery and the macabre. He is wid ...

, and Edgar Rice Burroughs. Moskowitz also notes that Smith's "reading enthusiasms included poetry, philosophy, ancient and medieval history, and all of English literature". (Smith's grandson notes that he spoke, and sang, German.) The influence of these is not readily apparent, except in the Roman section of ''Triplanetary'', and in the impeccable but convoluted grammar of Smith's narration. Some influence of 19th-century philosophy of language

In analytic philosophy, philosophy of language investigates the nature of language and the relations between language, language users, and the world. Investigations may include inquiry into the nature of Meaning (philosophy of language), meanin ...

may be detectable in the account in ''Galactic Patrol'' of the Lens of Arisia as a universal translator

A universal translator is a device common to many science fiction works, especially on television. First described in Murray Leinster's 1945 novella " First Contact", the translator's purpose is to offer an instant translation of any language.

...

, which is reminiscent of Frege

Friedrich Ludwig Gottlob Frege (; ; 8 November 1848 – 26 July 1925) was a German philosopher, logician, and mathematician. He was a mathematics professor at the University of Jena, and is understood by many to be the father of analytic p ...

's strong realism

Realism, Realistic, or Realists may refer to:

In the arts

*Realism (arts), the general attempt to depict subjects truthfully in different forms of the arts

Arts movements related to realism include:

* Classical Realism

*Literary realism, a mov ...

about ''Sinn'', that is, thought or sense.

Both Moskowitz and Smith's daughter Verna Smith Trestrail report that Smith had a troubled relationship with John Campbell, the editor of ''Astounding''. Smith's most successful works were published under Campbell, but the degree of influence is uncertain. The original outline for the ''Lensman'' series had been accepted by F. Orlin Tremaine

Frederick Orlin Tremaine (January 7, 1899 – October 22, 1956) was an American science fiction magazine editor, most notably of the influential ''Astounding Stories''. He edited a number of other magazines, headed several publishing companies ...

,Moskowitz p. 19 and Smith angered Campbell by showing loyalty to Tremaine at his new magazine, ''Comet'', when he sold him "The Vortex Blaster" in 1941. Campbell's announcement of ''Children of the Lens'', in 1947, was less than enthusiastic. Campbell later said that he published it only reluctantly, though he praised it privately, and bought little from Smith thereafter.

Derivative works and influence on popular culture

*Randall Garrett

Gordon Randall Phillip David GarrettGarrett, Randall

in ''

in ''

Backstage Lensman'' which Smith reportedly enjoyed. Harry Harrison also parodied Smith's work in the novel, ''

''Skylark Three''

(original magazine version)

''Spacehounds of IPC''

(original magazine version)

''Some Clays of Idaho''

Smith's bachelor's thesis, from the

Star Smashers of the Galaxy Rangers

''Star Smashers of the Galaxy Rangers'' is a 1973 comic science fiction novel by American writer Harry Harrison. It is a parody of the space opera genre and in particular, the Lensman and Skylark series of E. E. "Doc" Smith. The main characters ...

''.

* Sir Arthur C. Clarke

Sir Arthur Charles Clarke (16 December 191719 March 2008) was an English science-fiction writer, science writer, futurist, inventor, undersea explorer, and television series host.

He co-wrote the screenplay for the 1968 film '' 2001: A Spac ...

's space battle in ''Earthlight

''Earthlight'' is a science fiction novel by British writer Arthur C. Clarke, published in 1955. It is an expansion to novel length of a novella of the same name that he had published four years earlier.

Overview

''Earthlight'' is a scie ...

'' was based on the attack on the Mardonalian fortress in chapter seven of ''Skylark Three

''Skylark Three'' is a science fiction novel by American writer E. E. Smith, the second in his ''Skylark'' series. Originally serialized through the ''Amazing Stories'' magazine in 1930, it was first collected in book form in 1948 by Fantasy P ...

''.

* Steve 'Slug' Russell wrote one of the first computer games, ''Spacewar!

''Spacewar!'' is a Space combat game, space combat video game developed in 1962 by Steve Russell (computer scientist), Steve Russell in collaboration with Martin Graetz, Wayne Wiitanen, Robert Alan Saunders, Bob Saunders, Steve Piner, and others. ...

'', with inspiration from the space battles from the Lensman series.

* The Japanese ''Lensman'' anime

is Traditional animation, hand-drawn and computer animation, computer-generated animation originating from Japan. Outside of Japan and in English, ''anime'' refers specifically to animation produced in Japan. However, in Japan and in Japane ...

is more an imitation of ''Star Wars

''Star Wars'' is an American epic space opera multimedia franchise created by George Lucas, which began with the eponymous 1977 film and quickly became a worldwide pop-culture phenomenon. The franchise has been expanded into various film ...

'' than a translation of the ''Lensman'' novels. Efforts to print translations of the associated manga

Manga ( Japanese: 漫画 ) are comics or graphic novels originating from Japan. Most manga conform to a style developed in Japan in the late 19th century, and the form has a long prehistory in earlier Japanese art. The term ''manga'' is ...

in the United States in the early 1990s without payment of royalties to the Smith family were successfully blocked in court by Verna Smith Trestrail with the help of several California science-fiction authors and fans.

* In his biography, George Lucas

George Walton Lucas Jr. (born May 14, 1944) is an American filmmaker. Lucas is best known for creating the '' Star Wars'' and '' Indiana Jones'' franchises and founding Lucasfilm, LucasArts, Industrial Light & Magic and THX. He served as c ...

reveals that the ''Lensman'' novels were a major influence on his youth. J. Michael Straczynski

Joseph Michael Straczynski (; born July 17, 1954) is an American filmmaker and comic book writer. He is the founder of Synthetic Worlds Ltd. and Studio JMS and is best known as the creator of the science fiction television series ''Babylon 5'' ...

, creator of the science-fiction television series ''Babylon 5

''Babylon 5'' is an American space opera television series created by writer and producer J. Michael Straczynski, under the Babylonian Productions label, in association with Straczynski's Synthetic Worlds Ltd. and Warner Bros. Domestic Tele ...

'', also has acknowledged the influence of the ''Lensman'' books.

* Superman

Superman is a superhero who appears in American comic books published by DC Comics. The character was created by writer Jerry Siegel and artist Joe Shuster, and debuted in the comic book '' Action Comics'' #1 ( cover-dated June 1938 and pu ...

creator Jerry Siegel

Jerome Siegel ( ; October 17, 1914 – January 28, 1996) Roger Stern. ''Superman: Sunday Classics: 1939–1943'' DC Comics/ Kitchen Sink Press, Inc./Sterling Publishing; 2006 was an American comic book writer. He is the co-creator of Superman, i ...

was impressed, at an early age, with the optimistic vision of the future presented in ''Skylark of Space''.

* An attempt to create a feature film based on the ''Lensman'' series by Ron Howard

Ronald William Howard (born March 1, 1954) is an American director, producer, screenwriter, and actor. He first came to prominence as a child actor, guest-starring in several television series, including an episode of '' The Twilight Zone''. ...

's Imagine Entertainment

Imagine Entertainment (formerly Imagine Films Entertainment), also known simply as Imagine, is an American film and television production company founded in November 1985 by producer Brian Grazer and director Ron Howard.

Background

Brian Graz ...

and Universal Studios

Universal Pictures (legally Universal City Studios LLC, also known as Universal Studios, or simply Universal; common metonym: Uni, and formerly named Universal Film Manufacturing Company and Universal-International Pictures Inc.) is an Americ ...

began in 2008 with J. Michael Straczynski

Joseph Michael Straczynski (; born July 17, 1954) is an American filmmaker and comic book writer. He is the founder of Synthetic Worlds Ltd. and Studio JMS and is best known as the creator of the science fiction television series ''Babylon 5'' ...

, the creator of ''Babylon 5

''Babylon 5'' is an American space opera television series created by writer and producer J. Michael Straczynski, under the Babylonian Productions label, in association with Straczynski's Synthetic Worlds Ltd. and Warner Bros. Domestic Tele ...

'', as writer, but in 2014 the project was scrapped because of budget limitations.

* In her short "Pliocene Companion" book, author Julian May explained that a major character in her Exile

Exile is primarily penal expulsion from one's native country, and secondarily expatriation or prolonged absence from one's homeland under either the compulsion of circumstance or the rigors of some high purpose. Usually persons and peoples suf ...

series written in the early 1980s, Marc Remillard, was strongly influenced by Smith's villain character from Skylark DuQuesne

''Skylark DuQuesne'' is a science fiction novel by American writer E. E. Smith, the final novel in his ''Skylark'' series. Written as Smith's last novel in 1965 and published shortly before his death, it expands on the characterizations of the e ...

, Marc DuQuesne. This was somewhat of a tribute to Smith. May had written an early SF work called Dune Roller in 1950, and had attended several Science Fiction Conventions in the early '50's, where she met and came to know Smith personally.

Fictional appearances

Smith himself appears as a character in the 2006 novel '' The Chinatown Death Cloud Peril'' by Paul Malmont. The novel describes friendship and rivalry among pulp writers of the 1930s. He also appears as "Lensman Ted Smith" in the 1980 novel '' The Number of the Beast'' and as "Commander Ted Smith" in the 1985 novel '' The Cat Who Walks Through Walls'', both by Robert A. Heinlein. It is also suggested that he was one of the inspirations for Heinlein's characterLazarus Long

Lazarus Long is a fictional character featured in a number of science fiction novels by Robert A. Heinlein. Born in 1912 in the third generation of a selective breeding experiment run by the Ira Howard Foundation, Lazarus (birth name Woodrow Wi ...

. Christopher Nuttall incorporates a fictional quote from “Edward E. Smith, Professor of Sociology” in his military science fiction book, “No Worse Enemy”.

Bibliography

Because he died in 1965, the works of E. E. Smith are nowpublic domain

The public domain (PD) consists of all the creative work to which no exclusive intellectual property rights apply. Those rights may have expired, been forfeited, expressly waived, or may be inapplicable. Because those rights have expired ...

in countries where the term of copyright lasts 50 years after the death of the author, or less; generally this does not include works first published posthumously. Works first published before 1927 are also public domain in the United States. Additionally, a number of the author's works have become public domain in the United States owing to non-renewal of copyright.

Lensman

The ''Lensman'' series is a series of science fiction novels by American author E. E. "Doc" Smith. It was a runner-up for the 1966 Hugo award for Best All-Time Series, losing to the ''Foundation'' series by Isaac Asimov.

Plot

The series begins ...

# ''Triplanetary

''Triplanetary'' is a science fiction board wargame originally published by Game Designers' Workshop in 1973. The game is a simulation of space ship travel and combat within the Solar System in the early 21st Century.

History First edition

''T ...

'' (1948)

# ''First Lensman

''First Lensman'' is a science fiction novel and space opera by American author E. E. Smith. It was first published in 1950 by Fantasy Press in an edition of 5,995 copies. Although it is the second novel in the ''Lensman'' series, it was the s ...

'' (1950)

# ''Galactic Patrol

The Galactic Patrol was an intergalactic organization in the ''Lensman'' science fiction series written by E. E. Smith. It was also the title of the third book in the series.

Overview

In the Lensman novels, the Galactic Patrol was a combination ...

'' (1950)

# ''Gray Lensman

''Gray Lensman'' is a science fiction novel by American writer E. E. Smith. It was first published in book form in 1951 by Fantasy Press in an edition of 5,096 copies. The novel was originally serialized in the magazine ''Astounding'' in 1939.

G ...

'' (1951)

# '' Second Stage Lensmen'' (1953)

# ''The Vortex Blaster

''The Vortex Blaster'' is a collection of three science fiction short stories by American writer Edward E. Smith. It was simultaneously published in 1960 by Gnome Press in an edition of 3,000 copies and by Fantasy Press in an edition of 341 copie ...

'' (1960)

# '' Children of the Lens'' (1954)

Skylark

''Alauda'' is a genus of larks found across much of Europe, Asia and in the mountains of north Africa, and one of the species (the Raso lark) endemic to the islet of Raso in the Cape Verde Islands. Further, at least two additional species are ...

# ''The Skylark of Space

''The Skylark of Space'' is a science fiction novel by American writer Edward E. "Doc" Smith, written between 1915 and 1921 while Smith was working on his doctorate. Though the original idea for the novel was Smith's, he co-wrote the first part o ...

'' (1946)

# ''Skylark Three

''Skylark Three'' is a science fiction novel by American writer E. E. Smith, the second in his ''Skylark'' series. Originally serialized through the ''Amazing Stories'' magazine in 1930, it was first collected in book form in 1948 by Fantasy P ...

'' (1948)

# ''Skylark of Valeron

''Skylark of Valeron'' is a science fiction novel by the American writer E. E. Smith, the third in his Skylark series. Originally serialized in the magazine ''Astounding'' in 1934, it was first collected in book form in 1949 by Fantasy Press.

Plo ...

'' (1949)

# ''Skylark DuQuesne

''Skylark DuQuesne'' is a science fiction novel by American writer E. E. Smith, the final novel in his ''Skylark'' series. Written as Smith's last novel in 1965 and published shortly before his death, it expands on the characterizations of the e ...

'' (1966)

Subspace

# '' Subspace Explorers'' (1965) # '' Subspace Encounter'' (1983)References

External links

* * * * * * * * *''Skylark Three''

(original magazine version)

''Spacehounds of IPC''

(original magazine version)

''Some Clays of Idaho''

Smith's bachelor's thesis, from the

University of Idaho

The University of Idaho (U of I, or UIdaho) is a public land-grant research university in Moscow, Idaho. It is the state's land-grant and primary research university,, and the lead university in the Idaho Space Grant Consortium. The Universit ...

{{DEFAULTSORT:Smith, E. E.

1890 births

1965 deaths

American science fiction writers

Science Fiction Hall of Fame inductees

Writers from Boise, Idaho

People from Sheboygan, Wisconsin

People from Seaside, Oregon

Novelists from Wisconsin

University of Idaho alumni

Columbian College of Arts and Sciences alumni

American Presbyterians

20th-century American novelists

Pulp fiction writers

American male novelists

Novelists from Idaho

20th-century American male writers