Dylan Thomas on:

[Wikipedia]

[Google]

[Amazon]

Dylan Thomas was born on 27 October 1914 in Swansea the son of Florence Hannah (''née'' Williams; 1882–1958), a

Dylan Thomas was born on 27 October 1914 in Swansea the son of Florence Hannah (''née'' Williams; 1882–1958), a

In October 1925, Thomas enrolled at Swansea Grammar School for boys, in Mount Pleasant, where his father taught English. He was an undistinguished pupil who shied away from school, preferring reading and drama activities. In his first year one of his poems was published in the school's magazine, and before he left he became its editor. Thomas' various contributions to the school magazine can be found here:

During his final school years he began writing poetry in notebooks; the first poem, dated 27 April (1930), is entitled "Osiris, come to Isis". In June 1928, Thomas won the school's mile race, held at St. Helen's Ground; he carried a newspaper photograph of his victory with him until his death.

In 1931, when he was 16, Thomas left school to become a reporter for the '' South Wales Daily Post'', where he remained for some 18 months. After leaving the newspaper, Thomas continued to work as a freelance journalist for several years, during which time he remained at Cwmdonkin Drive and continued to add to his notebooks, amassing 200 poems in four books between 1930 and 1934. Of the 90 poems he published, half were written during these years.

In October 1925, Thomas enrolled at Swansea Grammar School for boys, in Mount Pleasant, where his father taught English. He was an undistinguished pupil who shied away from school, preferring reading and drama activities. In his first year one of his poems was published in the school's magazine, and before he left he became its editor. Thomas' various contributions to the school magazine can be found here:

During his final school years he began writing poetry in notebooks; the first poem, dated 27 April (1930), is entitled "Osiris, come to Isis". In June 1928, Thomas won the school's mile race, held at St. Helen's Ground; he carried a newspaper photograph of his victory with him until his death.

In 1931, when he was 16, Thomas left school to become a reporter for the '' South Wales Daily Post'', where he remained for some 18 months. After leaving the newspaper, Thomas continued to work as a freelance journalist for several years, during which time he remained at Cwmdonkin Drive and continued to add to his notebooks, amassing 200 poems in four books between 1930 and 1934. Of the 90 poems he published, half were written during these years.

"Thomas, Caitlin (1913–1994)", ''Oxford Dictionary of National Biography'', Oxford University Press, 2004 (subscription only) Laying his head in her lap, a drunken Thomas proposed. Thomas liked to comment that he and Caitlin were in bed together ten minutes after they first met. Although Caitlin initially continued her relationship with John, she and Thomas began a correspondence, and in the second half of 1936 were courting. They married at the register office in Penzance, Cornwall, on 11 July 1937. In May 1938, they moved to Wales, renting a cottage in the village of

, which not only gave him additional earnings but also provided evidence that he was engaged in essential war work.

In February 1941, Swansea was bombed by the

Dylan Marlais Thomas (27 October 1914 – 9 November 1953) was a Welsh poet and writer whose works include the poems "

during the late 1940s brought him to the public's attention, and he was frequently used by the BBC as an accessible voice of the literary scene.

Thomas first travelled to the United States in the 1950s. His readings there brought him a degree of fame, while his erratic behaviour and drinking worsened. His time in the United States cemented his legend, and he went on to record to Do not go gentle into that good night

"Do not go gentle into that good night" is a poem in the form of a villanelle by Welsh poet Dylan Thomas (1914–1953), and is one of his best-known works. Though first published in the journal ''Botteghe Oscure'' in 1951, the poem was written in ...

" and " And death shall have no dominion", as well as the "play for voices" ''Under Milk Wood

''Under Milk Wood'' is a 1954 radio drama by Welsh poet Dylan Thomas, commissioned by the BBC and later adapted for the stage. A film version, ''Under Milk Wood'' directed by Andrew Sinclair, was released in 1972, and another adaptation of ...

''. He also wrote stories and radio broadcasts such as '' A Child's Christmas in Wales'' and '' Portrait of the Artist as a Young Dog''. He became widely popular in his lifetime and remained so after his death at the age of 39 in New York City. By then, he had acquired a reputation, which he had encouraged, as a "roistering, drunken and doomed poet".

Thomas was born in Swansea, Wales

Wales ( cy, Cymru ) is a country that is part of the United Kingdom. It is bordered by England to the east, the Irish Sea to the north and west, the Celtic Sea to the south west and the Bristol Channel to the south. It had a population in ...

, in 1914. In 1931, when he was 16, Thomas, an undistinguished pupil, left school to become a reporter for the '' South Wales Daily Post''. Many of his works appeared in print while he was still a teenager. In 1934, the publication of "Light breaks where no sun shines" caught the attention of the literary world. While living in London, Thomas met Caitlin Macnamara. They married in 1937 and had three children: Llewelyn, Aeronwy, and Colm.

He came to be appreciated as a popular poet during his lifetime, though he found earning a living as a writer difficult. He began augmenting his income with reading tours and radio broadcasts. His radio recordings for the BBC #REDIRECT BBC #REDIRECT BBC

Here i going to introduce about the best teacher of my life b BALAJI sir. He is the precious gift that I got befor 2yrs . How has helped and thought all the concept and made my success in the 10th board exam. ...

...vinyl

Vinyl may refer to:

Chemistry

* Polyvinyl chloride (PVC), a particular vinyl polymer

* Vinyl cation, a type of carbocation

* Vinyl group, a broad class of organic molecules in chemistry

* Vinyl polymer, a group of polymers derived from vinyl ...

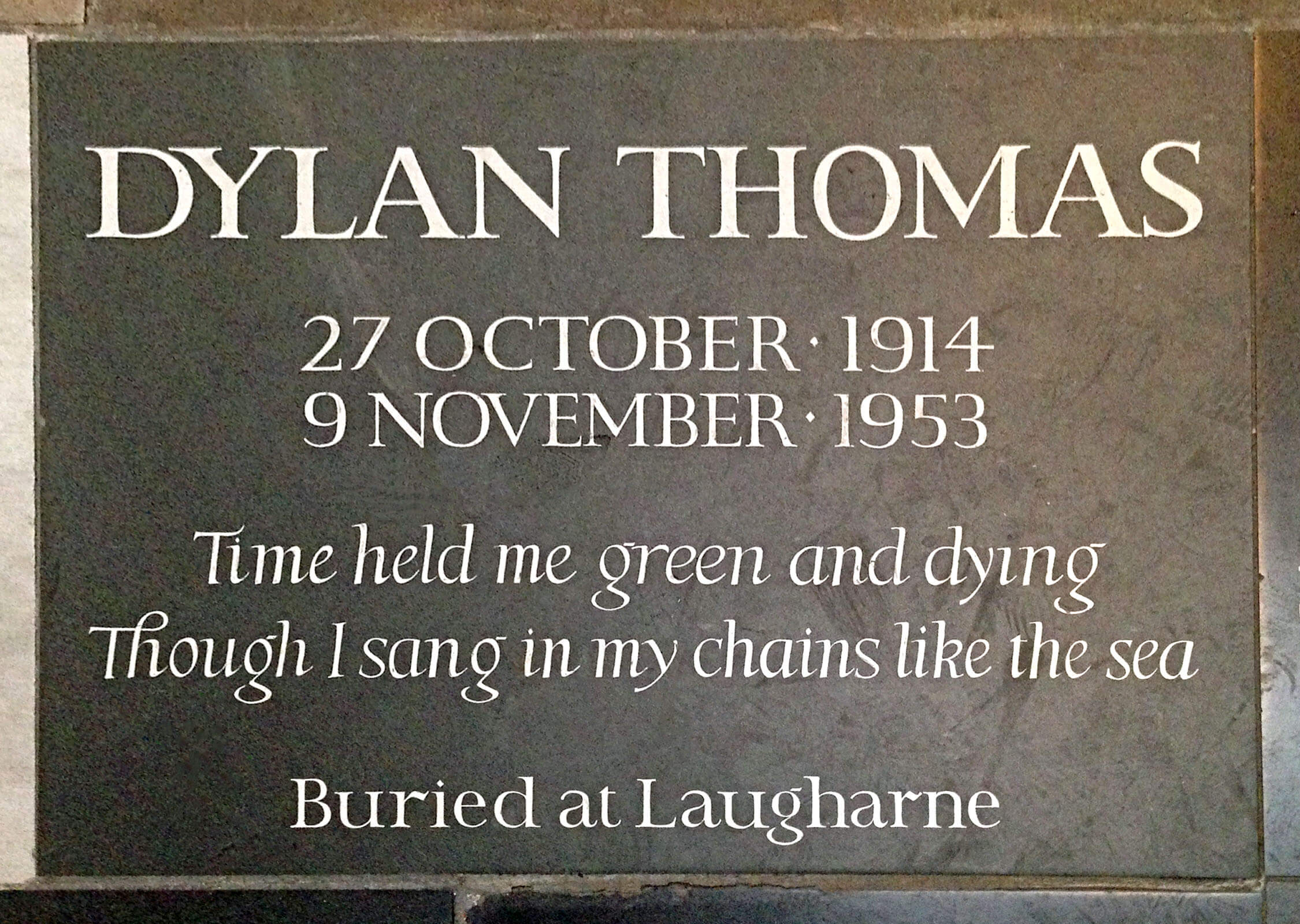

such works as ''A Child's Christmas in Wales''. During his fourth trip to New York in 1953, Thomas became gravely ill and fell into a coma. He died on 9 November 1953 and his body was returned to Wales. On 25 November 1953, he was interred at St Martin's churchyard in Laugharne

Laugharne ( cy, Talacharn) is a town on the south coast of Carmarthenshire, Wales, lying on the estuary of the River Tâf.

The ancient borough of Laugharne Township ( cy, Treflan Lacharn) with its Corporation and Charter is a unique survival ...

, Carmarthenshire.

Although Thomas wrote exclusively in the English language, he has been acknowledged as one of the most important Welsh poets of the 20th century. He is noted for his original, rhythmic, and ingenious use of words and imagery. His position as one of the great modern poets has been much discussed, and he remains popular with the public.

Life and career

Early time

Dylan Thomas was born on 27 October 1914 in Swansea the son of Florence Hannah (''née'' Williams; 1882–1958), a

Dylan Thomas was born on 27 October 1914 in Swansea the son of Florence Hannah (''née'' Williams; 1882–1958), a seamstress

A dressmaker, also known as a seamstress, is a person who makes custom clothing for women, such as dresses, blouses, and evening gowns. Dressmakers were historically known as mantua-makers, and are also known as a modiste or fabrician.

Not ...

, and David John Thomas (1876–1952), a teacher. His father had a first-class honours degree in English from University College, Aberystwyth, and ambitions to rise above his position teaching English literature at the local grammar school

A grammar school is one of several different types of school in the history of education in the United Kingdom and other English-speaking countries, originally a school teaching Latin, but more recently an academically oriented secondary school ...

. Thomas had one sibling, Nancy Marles (1906–1953), who was eight years his senior. The children spoke only English, though their parents were bilingual in English and Welsh, and David Thomas gave Welsh lessons at home. Thomas's father chose the name Dylan, which could be translated as "son of the sea" after Dylan ail Don Dylan ail Don () (in Middle Welsh) is a character in the Welsh mythic Mabinogion tales, particularly in the fourth tale, "'' Math fab Mathonwy''". The story of Dylan reflects ancient Celtic myths that were handed down orally for some generations b ...

, a character in ''The Mabinogion

The ''Mabinogion'' () are the earliest Welsh prose stories, and belong to the Matter of Britain. The stories were compiled in Middle Welsh in the 12th–13th centuries from earlier oral traditions. There are two main source manuscripts, create ...

''. His middle name, Marlais, was given in honour of his great-uncle, William Thomas, a Unitarian minister and poet whose bardic name was Gwilym Marles. Dylan, pronounced ˈ �dəlan(Dull-an) in Welsh, caused his mother to worry that he might be teased as the "dull one". When he broadcast on Welsh BBC early in his career, he was introduced using this pronunciation. Thomas favoured the Anglicised pronunciation and gave instructions that it should be Dillan .

The red-brick semi-detached house at 5 Cwmdonkin Drive (in the respectable area of the Uplands), in which Thomas was born and lived until he was 23, had been bought by his parents a few months before his birth.

Childhood

Thomas has written a number of accounts of his childhood growing up in Swansea, and there are also accounts available by those who knew him as a young child. Thomas wrote several poems about his childhood and early teenage years, including "Once it was the colour of saying" and "The hunchback in the park", as well as short stories such as ''The Fight'' and ''A Child’s Christmas in Wales''. Thomas' childhood also featured regular summer trips to theLlansteffan

Llansteffan, is a village and a community situated on the south coast of Carmarthenshire, Wales, lying on the estuary of the River Tywi, south of Carmarthen.

Description

The community includes Llanybri and is bordered by the communities of: ...

peninsula, a Welsh-speaking part of Carmarthenshire, In the land between Llangain

Llangain is a village and community in Carmarthenshire, in the south-west of Wales. Located to the west of the River Towy, and south of the town of Carmarthen, the community contains three standing stones, and two chambered tombs as well as the ...

and Llansteffan, his mother's family, the Williamses and their close relatives, worked a dozen farms with over a thousand acres between them. The memory of Fernhill, a dilapidated 15-acre farm rented by his maternal aunt, Ann Jones, and her husband, Jim Jones, is evoked in the 1945 lyrical poem " Fern Hill", but is portrayed more accurately in his short story, ''The Peaches''. Thomas also spent part of his summer holidays with Jim's sister, Rachel Jones, at neighbouring Pentrewyman farm.

A few fields south of Fernhill lay Blaencwm, a pair of stone cottages to which his mother’s Swansea siblings had retired, and with whom the young Thomas and his sister, Nancy, would sometimes stay. A couple of miles down the road from Blaencwm is the village of Llansteffan

Llansteffan, is a village and a community situated on the south coast of Carmarthenshire, Wales, lying on the estuary of the River Tywi, south of Carmarthen.

Description

The community includes Llanybri and is bordered by the communities of: ...

, where Thomas used to holiday at Rose Cottage with his aunt, Anne Williams, his mother’s half-sister who had married into local gentry.

Thomas' paternal grandparents, Anne and Evan Thomas, lived at The Poplars in Johnstown, just outside Carmarthen

Carmarthen (, RP: ; cy, Caerfyrddin , "Merlin's fort" or "Sea-town fort") is the county town of Carmarthenshire and a community in Wales, lying on the River Towy. north of its estuary in Carmarthen Bay. The population was 14,185 in 2011, ...

. Anne was the daughter of William Lewis, a gardener in the town. She had been born and brought up in Llangadog

Llangadog () is a village and community located in Carmarthenshire, Wales, which also includes the villages of Bethlehem and Capel Gwynfe. A notable local landscape feature is Y Garn Goch with two Iron Age hill forts.The Welsh Academy Encycloped ...

, as had her father, who is thought to be “Grandpa” in Thomas's short story ''A Visit to Grandpa's'', in which Grandpa expresses his determination to be buried not in Llansteffan but in Llangadog.

Evan worked on the railways and was known as Thomas the Guard. His family had originated in another part of Welsh-speaking Carmarthenshire, in the farms that lay around the villages of Brechfa, Abergorlech, Gwernogle and Llanybydder, and which the young Thomas occasionally visited with his father. His father's side of the family also provided the young Thomas with another kind of experience; most lived in the towns of the South Wales industrial belt, including Port Talbot

Port Talbot (, ) is a town and community in the county borough of Neath Port Talbot, Wales, situated on the east side of Swansea Bay, approximately from Swansea. The Port Talbot Steelworks covers a large area of land which dominates the south ...

, Pontarddulais

Pontarddulais (), also known as Pontardulais (), is both a community and a town in Swansea, Wales. It is northwest of the city centre. The Pontarddulais ward is part of the City and County of Swansea. Pontarddulais adjoins the village of Hendy ...

and Cross Hands

Cross Hands is a town in Carmarthenshire, Wales, approximately from Carmarthen.

Cross Hands Public Hall is one of only three of its kind in Wales. The Public Hall was erected in 1920 and designed by an unknown Italian designer in the classic A ...

.

Thomas had bronchitis

Bronchitis is inflammation of the bronchi (large and medium-sized airways) in the lungs that causes coughing. Bronchitis usually begins as an infection in the nose, ears, throat, or sinuses. The infection then makes its way down to the bronchi. ...

and asthma

Asthma is a long-term inflammatory disease of the airways of the lungs. It is characterized by variable and recurring symptoms, reversible airflow obstruction, and easily triggered bronchospasms. Symptoms include episodes of wheezing, co ...

in childhood and struggled with these throughout his life. He was indulged by his mother, Florence, and enjoyed being mollycoddled, a trait he carried into adulthood, becoming skilful in gaining attention and sympathy.Ferris (1989), p. 25. But Florence would have known that child deaths had been a recurring event in the family's history, and it's said that she herself had lost a child soon after her marriage. But if Thomas was protected and spoilt at home, the real spoilers were his many aunts and older cousins, those in both Swansea and the Llansteffan countryside. Some of them played an important part in both his upbringing and his later life, as Thomas’s wife, Caitlin, has observed: “He couldn't stand their company for more than five minutes... Yet Dylan couldn't break away from them, either. They were the background from which he had sprung, and he needed that background all his life, like a tree needs roots.”.

Education

Thomas's formal education began at Mrs Hole'sdame school

Dame schools were small, privately run schools for young children that emerged in the British Isles and its colonies during the early modern period. These schools were taught by a “school dame,” a local woman who would educate children f ...

, a private school on Mirador Crescent, a few streets away from his home. He described his experience there in ''Reminiscences of Childhood'':

Never was there such a dame school as ours, so firm and kind and smelling of galoshes, with the sweet and fumbled music of the piano lessons drifting down from upstairs to the lonely schoolroom, where only the sometimes tearful wicked sat over undone sums, or to repent a little crime – the pulling of a girl's hair during geography, the sly shin kick under the table during English literature.Alongside dame school, Thomas also took private lessons from Gwen James, an elocution teacher who had studied at drama school in London, winning several major prizes. She also taught “Dramatic Art” and “Voice Production”, and would often help cast members of the Swansea Little Theatre (see below) with the parts they were playing. Thomas's parents’ storytelling and dramatic talents, as well as their theatre-going interests, could also have contributed to the young Thomas’s interest in performance.

In October 1925, Thomas enrolled at Swansea Grammar School for boys, in Mount Pleasant, where his father taught English. He was an undistinguished pupil who shied away from school, preferring reading and drama activities. In his first year one of his poems was published in the school's magazine, and before he left he became its editor. Thomas' various contributions to the school magazine can be found here:

During his final school years he began writing poetry in notebooks; the first poem, dated 27 April (1930), is entitled "Osiris, come to Isis". In June 1928, Thomas won the school's mile race, held at St. Helen's Ground; he carried a newspaper photograph of his victory with him until his death.

In 1931, when he was 16, Thomas left school to become a reporter for the '' South Wales Daily Post'', where he remained for some 18 months. After leaving the newspaper, Thomas continued to work as a freelance journalist for several years, during which time he remained at Cwmdonkin Drive and continued to add to his notebooks, amassing 200 poems in four books between 1930 and 1934. Of the 90 poems he published, half were written during these years.

In October 1925, Thomas enrolled at Swansea Grammar School for boys, in Mount Pleasant, where his father taught English. He was an undistinguished pupil who shied away from school, preferring reading and drama activities. In his first year one of his poems was published in the school's magazine, and before he left he became its editor. Thomas' various contributions to the school magazine can be found here:

During his final school years he began writing poetry in notebooks; the first poem, dated 27 April (1930), is entitled "Osiris, come to Isis". In June 1928, Thomas won the school's mile race, held at St. Helen's Ground; he carried a newspaper photograph of his victory with him until his death.

In 1931, when he was 16, Thomas left school to become a reporter for the '' South Wales Daily Post'', where he remained for some 18 months. After leaving the newspaper, Thomas continued to work as a freelance journalist for several years, during which time he remained at Cwmdonkin Drive and continued to add to his notebooks, amassing 200 poems in four books between 1930 and 1934. Of the 90 poems he published, half were written during these years.

On the Stage

The stage was also an important part of Thomas’s life from 1929 to 1934, as an actor, writer, producer and set painter. He took part in productions at Swansea Grammar School, and with the YMCA Junior Players and the Little Theatre, which was based in theMumbles

Mumbles ( cy, Mwmbwls) is a headland sited on the western edge of Swansea Bay on the southern coast of Wales.

Toponym

Mumbles has been noted for its unusual place name. The headland is thought by some to have been named by French sailors, ...

. It was also a touring company that took part in drama competitions and festivals around South Wales. Between October 1933 and March 1934, for example, Thomas and his fellow actors took part in five productions at the Mumbles theatre, as well as nine touring performances. Thomas continued with acting and production throughout his life, including his time in Laugharne, South Leigh and London (in the theatre and on radio), as well as taking part in nine stage readings of ''Under Milk Wood''. The Shakespearian actor, John Laurie

John Paton Laurie (25 March 1897 – 23 June 1980) was a Scottish actor. In the course of his career, Laurie performed on the stage and in films as well as television. He is perhaps best remembered for his role in the sitcom '' Dad's Army'' (19 ...

, who had worked with Thomas on both the stage and radio thought that Thomas would “have loved to have been an actor” and, had he chosen to do so, would have been “Our first real poet-dramatist since Shakespeare.”

Painting the sets at the Little Theatre was just one aspect of the young Thomas’s interest in art. His own drawings and paintings hung in his bedroom in Cwmdonkin Drive, and his early letters reveal a broader interest in art and art theory. Thomas saw writing a poem as an act of construction “as a sculptor works at stone,” later advising a student “to treat words as a craftsman does his wood or stone...hew, carve, mould, coil, polish and plane them...” Throughout his life, his friends included artists, both in Swansea and in London, as well as in America.

In his free time, Thomas visited the cinema in Uplands, took walks along Swansea Bay

Swansea Bay ( cy, Bae Abertawe) is a bay on the southern coast of Wales. The River Neath, River Tawe, River Afan, River Kenfig and Clyne River flow into the bay. Swansea Bay and the upper reaches of the Bristol Channel experience a large tid ...

, and frequented Swansea's pub

A pub (short for public house) is a kind of drinking establishment which is licensed to serve alcoholic drinks for consumption on the premises. The term ''public house'' first appeared in the United Kingdom in late 17th century, and was ...

s, especially the Antelope and the Mermaid Hotels in Mumbles. In the Kardomah Café, close to the newspaper office in Castle Street, he met his creative contemporaries, including his friend the poet Vernon Watkins

Vernon Phillips Watkins (27 June 1906 – 8 October 1967) was a Welsh poet and translator. His headmaster at Repton was Geoffrey Fisher, who became Archbishop of Canterbury. Despite his parents being Nonconformists, Watkins' school experienc ...

and the musician and composer, Daniel Jones with whom, as teenagers, Thomas had helped to set up the "Warmley Broadcasting Corporation". This group of writers, musicians and artists became known as " The Kardomah Gang". This was also the period of his friendship with Bert Trick, a local shopkeeper, left-wing political activist and would-be poet, and with the Rev. Leon Atkin, a Swansea minister, human rights activist and local politician.

In 1933, Thomas visited London for probably the first time.

London and marriage, 1933–1939

Thomas was a teenager when many of the poems for which he became famous were published: " And death shall have no dominion", "Before I Knocked" and "The Force That Through the Green Fuse Drives the Flower". "And death shall have no dominion" appeared in the ''New English Weekly

''The New English Weekly'' was a leading British review of "Public Affairs, Literature and the Arts."

It was founded in April 1932 by Alfred Richard Orage shortly after his return from Paris. One of Britain's most prestigious editors, Orage had ed ...

'' in May 1933. When "Light breaks where no sun shines" appeared in '' The Listener'' in 1934, it caught the attention of three senior figures in literary London, T. S. Eliot, Geoffrey Grigson

Geoffrey Edward Harvey Grigson (2 March 1905 – 25 November 1985) was a British poet, writer, editor, critic, exhibition curator, anthologist and naturalist. In the 1930s he was editor of the influential magazine ''New Verse'', and went on to p ...

and Stephen Spender

Sir Stephen Harold Spender (28 February 1909 – 16 July 1995) was an English poet, novelist and essayist whose work concentrated on themes of social injustice and the class struggle. He was appointed Poet Laureate Consultant in Poetry by th ...

. They contacted Thomas and his first poetry volume, ''18 Poems'', was published in December 1934. ''18 Poems'' was noted for its visionary qualities which led to critic Desmond Hawkins

Desmond Hawkins, OBE (20 October 1908 – 6 May 1999), born in East Sheen, Surrey, was an author, editor and radio personality.

Career

The political and artistic upheavals of the 1930s meant a proliferation of serious magazines. Desmond w ...

writing that the work was "the sort of bomb that bursts no more than once in three years". The volume was critically acclaimed and won a contest run by the '' Sunday Referee'', netting him new admirers from the London poetry world, including Edith Sitwell

Dame Edith Louisa Sitwell (7 September 1887 – 9 December 1964) was a British poet and critic and the eldest of the three literary Sitwells. She reacted badly to her eccentric, unloving parents and lived much of her life with her governess ...

and Edwin Muir

Edwin Muir CBE (15 May 1887 – 3 January 1959) was a Scottish poet, novelist and translator. Born on a farm in Deerness, a parish of Orkney, Scotland, he is remembered for his deeply felt and vivid poetry written in plain language and w ...

. The anthology was published by Fortune Press, in part a vanity publisher that did not pay its writers and expected them to buy a certain number of copies themselves. A similar arrangement was used by other new authors including Philip Larkin

Philip Arthur Larkin (9 August 1922 – 2 December 1985) was an English poet, novelist, and librarian. His first book of poetry, ''The North Ship'', was published in 1945, followed by two novels, ''Jill'' (1946) and ''A Girl in Winter'' (1947 ...

.

In September 1935, Thomas met Vernon Watkins, thus beginning a lifelong friendship. Thomas introduced Watkins, working at Lloyds Bank at the time, to his friends, now known as The Kardomah Gang. In those days, Thomas used to frequent the cinema on Mondays with Tom Warner who, like Watkins, had recently suffered a nervous breakdown

A mental disorder, also referred to as a mental illness or psychiatric disorder, is a behavioral or mental pattern that causes significant distress or impairment of personal functioning. Such features may be persistent, relapsing and remitt ...

. After these trips, Warner would bring Thomas back for supper with his aunt. On one occasion, when she served him a boiled egg, she had to cut its top off for him, as Thomas did not know how to do this. This was because his mother had done it for him all his life, an example of her coddling him. Years later, his wife Caitlin would still have to prepare his eggs for him.

In December 1935, Thomas contributed the poem "The Hand That Signed the Paper" to Issue 18 of the bi-monthly ''New Verse''. In 1936, his next collection ''Twenty-five Poems'', published by J. M. Dent, also received much critical praise. Two years later, in 1938, Thomas won the Oscar Blumenthal Prize for Poetry; it was also the year in which New Directions offered to be his publisher in the United States. In all, he wrote half his poems while living at Cwmdonkin Drive before moving to London. It was the time that Thomas's reputation for heavy drinking developed.

By the late 1930s, Thomas was embraced as the "poetic herald" for a group of English poets, the New Apocalyptics

The New Apocalyptics were a poetry grouping in the United Kingdom in the 1940s, taking their name from the anthology ''The New Apocalypse'' ( 1939), which was edited by J. F. Hendry (1912–1986) and Henry Treece. There followed the further anth ...

. Thomas refused to align himself with them and declined to sign their manifesto. He later stated that he believed they were "intellectual muckpots leaning on a theory". Despite this, many of the group, including Henry Treece, modelled their work on Thomas's.

During the politically charged atmosphere of the 1930s, Thomas's sympathies were very much with the radical left, to the point of holding close links with the communists

Communism (from Latin la, communis, lit=common, universal, label=none) is a far-left sociopolitical, philosophical, and economic ideology and current within the socialist movement whose goal is the establishment of a communist society, a s ...

, as well as decidedly pacifist and anti-fascist. He was a supporter of the left-wing No More War Movement and boasted about participating in demonstrations against the British Union of Fascists. Bert Trick has provided an extensive account of an Oswald Mosley

Sir Oswald Ernald Mosley, 6th Baronet (16 November 1896 – 3 December 1980) was a British politician during the 1920s and 1930s who rose to fame when, having become disillusioned with mainstream politics, he turned to fascism. He was a member ...

rally in the Plaza cinema in Swansea in July 1933 that he and Thomas attended.

Marriage

In early 1936, Thomas met Caitlin Macnamara (1913–1994), a 22-year-old dancer of Irish and French Quaker descent. She had run away from home, intent on making a career in dance, and aged 18 joined the chorus line at theLondon Palladium

The London Palladium () is a Grade II* West End theatre located on Argyll Street, London, in the famous area of Soho. The theatre holds 2,286 seats. Of the roster of stars who have played there, many have televised performances. Between 1955 a ...

.Ferris (1989), p. 151 Introduced by Augustus John

Augustus Edwin John (4 January 1878 – 31 October 1961) was a Welsh painter, draughtsman, and etcher. For a time he was considered the most important artist at work in Britain: Virginia Woolf remarked that by 1908 the era of John Singer Sarge ...

, Caitlin's lover, they met in The Wheatsheaf pub on Rathbone Place in London's West End.Paul Ferris"Thomas, Caitlin (1913–1994)", ''Oxford Dictionary of National Biography'', Oxford University Press, 2004 (subscription only) Laying his head in her lap, a drunken Thomas proposed. Thomas liked to comment that he and Caitlin were in bed together ten minutes after they first met. Although Caitlin initially continued her relationship with John, she and Thomas began a correspondence, and in the second half of 1936 were courting. They married at the register office in Penzance, Cornwall, on 11 July 1937. In May 1938, they moved to Wales, renting a cottage in the village of

Laugharne

Laugharne ( cy, Talacharn) is a town on the south coast of Carmarthenshire, Wales, lying on the estuary of the River Tâf.

The ancient borough of Laugharne Township ( cy, Treflan Lacharn) with its Corporation and Charter is a unique survival ...

, Carmarthenshire. They lived there intermittently for just under two years until July 1941, and did not return to live in Laugharne until 1949. Their first child, Llewelyn Edouard, was born on 30 January 1939.

Wartime, 1939–1945

In 1939, a collection of 16 poems and seven of the 20 short stories published by Thomas in magazines since 1934, appeared as ''The Map of Love''. Ten stories in his next book, ''Portrait of the Artist as a Young Dog'' (1940), were based less on lavish fantasy than those in ''The Map of Love'' and more on real-life romances featuring himself in Wales. Sales of both books were poor, resulting in Thomas living on meagre fees from writing and reviewing. At this time he borrowed heavily from friends and acquaintances. Hounded by creditors, Thomas and his family left Laugharne in July 1940 and moved to the home of critic John Davenport in Marshfield near Chippenham inGloucestershire

Gloucestershire ( abbreviated Glos) is a county in South West England. The county comprises part of the Cotswold Hills, part of the flat fertile valley of the River Severn and the entire Forest of Dean.

The county town is the city of Gl ...

. There Thomas collaborated with Davenport on the satire ''The Death of the King's Canary'', though due to fears of libel the work was not published until 1976.

At the outset of the Second World War

World War II or the Second World War, often abbreviated as WWII or WW2, was a world war that lasted from 1939 to 1945. It involved the vast majority of the world's countries—including all of the great powers—forming two opposi ...

, Thomas was worried about conscription, and referred to his ailment as "an unreliable lung". Coughing sometimes confined him to bed, and he had a history of bringing up blood and mucus. After initially seeking employment in a reserved occupation

A reserved occupation (also known as essential services) is an occupation considered important enough to a country that those serving in such occupations are exempt or forbidden from military service.

In a total war, such as the Second World War, w ...

, he managed to be classified Grade III, which meant that he would be among the last to be called up for service. Saddened to see his friends going on active service, he continued drinking and struggled to support his family. He wrote begging letters to random literary figures asking for support, a plan he hoped would provide a long-term regular income. Thomas supplemented his income by writing scripts for the BBC #REDIRECT BBC #REDIRECT BBC

Here i going to introduce about the best teacher of my life b BALAJI sir. He is the precious gift that I got befor 2yrs . How has helped and thought all the concept and made my success in the 10th board exam. ...

...Luftwaffe

The ''Luftwaffe'' () was the aerial-warfare branch of the German ''Wehrmacht'' before and during World War II. Germany's military air arms during World War I, the ''Luftstreitkräfte'' of the Imperial Army and the '' Marine-Fliegerabtei ...

in a "three nights' blitz". Castle Street was one of many streets that suffered badly; rows of shops, including the Kardomah Café, were destroyed. Thomas walked through the bombed-out shell of the town centre with his friend Bert Trick. Upset at the sight, he concluded: "Our Swansea is dead". Thomas later wrote a feature programme for the radio, ''Return Journey'', which described the café as being "razed to the snow". The programme, produced by Philip Burton, was first broadcast on 15 June 1947. The Kardomah Café reopened on Portland Street after the war.

Making films

In five film projects, between 1942 and 1945, the Ministry of Information (MOI) commissioned Thomas to script a series of documentaries about bothurban planning

Urban planning, also known as town planning, city planning, regional planning, or rural planning, is a technical and political process that is focused on the development and design of land use and the built environment, including air, water, ...

and wartime patriotism, all in partnership with director John Eldridge: ''Wales: Green Mountain, Black Mountain'', '' New Towns for Old'', ''Fuel for Battle'', ''Our Country'' and ''A City Reborn.''

In May 1941, Thomas and Caitlin left their son with his grandmother at Blashford and moved to London. Thomas hoped to find employment in the film industry and wrote to the director of the films division of the Ministry of Information. After being rebuffed, he found work with Strand Films, providing him with his first regular income since the ''South Wales Daily Post''. Strand produced films for the MOI; Thomas scripted at least five films in 1942, ''This Is Colour'' (a history of the British dyeing industry) and ''New Towns For Old'' (on post-war reconstruction). ''These Are The Men'' (1943) was a more ambitious piece in which Thomas's verse accompanies Leni Riefenstahl

Helene Bertha Amalie "Leni" Riefenstahl (; 22 August 1902 – 8 September 2003) was a German film director, photographer and actress known for her role in producing Nazi propaganda.

A talented swimmer and an artist, Riefenstahl also became in ...

's footage of an early Nuremberg Rally

The Nuremberg Rallies (officially ', meaning ''Reich Party Congress'') refer to a series of celebratory events coordinated by the Nazi Party in Germany. The first rally held took place in 1923. This rally was not particularly large or impactful; ...

. ''Conquest of a Germ'' (1944) explored the use of early antibiotics in the fight against pneumonia

Pneumonia is an inflammatory condition of the lung primarily affecting the small air sacs known as alveoli. Symptoms typically include some combination of productive or dry cough, chest pain, fever, and difficulty breathing. The severi ...

and tuberculosis

Tuberculosis (TB) is an infectious disease usually caused by '' Mycobacterium tuberculosis'' (MTB) bacteria. Tuberculosis generally affects the lungs, but it can also affect other parts of the body. Most infections show no symptoms, i ...

. ''Our Country'' (1945) was a romantic tour of Britain set to Thomas's poetry.t

In early 1943, Thomas began a relationship with Pamela Glendower; one of several affairs he had during his marriage. The affairs either ran out of steam or were halted after Caitlin discovered his infidelity. In March 1943, Caitlin gave birth to a daughter, Aeronwy, in London. They lived in a run-down studio in Chelsea, made up of a single large room with a curtain to separate the kitchen.

Escaping to Wales

The Thomas family also made several escapes back to Wales. Between 1941 and 1943, they lived intermittently in Plas Gelli,Talsarn

Talsarn is a hamlet in the community of Nantcwnlle, Ceredigion, Wales. It lies some 16 miles (26 km) south of Aberystwyth, 64 miles (103 km) north-west of Cardiff, and 178 miles (286 km) from London. It is situated almost half-way ...

, in Cardiganshire. Plas Gelli sits close by the River Aeron

The River Aeron ( cy, Afon Aeron) is a small river in Ceredigion, Wales, that flows into Cardigan Bay at Aberaeron. It is also referred to on some older maps as the River Ayron.

Etymology

The name of the river means "battle" or "slaughter" and ...

, after whom Aeronwy is thought to have been named. Some of Thomas’s letters from Gelli can be found in his ''Collected Letters''. The Thomases shared the mansion with his childhood friends from Swansea, Vera and Evelyn Phillips. Vera's friendship with the Thomases in nearby New Quay

New Quay ( cy, Cei Newydd) is a seaside town (and electoral ward) in Ceredigion, Wales, with a resident population of around 1,200 people, reducing to 1,082 at the 2011 census. Located south-west of Aberystwyth on Cardigan Bay with a harbour a ...

is portrayed in the 2008 film, ''The Edge of Love''.

In July 1944, with the threat in London of German flying bombs, Thomas moved to the family cottage at Blaencwm near Llangain

Llangain is a village and community in Carmarthenshire, in the south-west of Wales. Located to the west of the River Towy, and south of the town of Carmarthen, the community contains three standing stones, and two chambered tombs as well as the ...

, Carmarthenshire, where he resumed writing poetry, completing "Holy Spring" and "Vision and Prayer".

In September that year, the Thomas family moved to New Quay

New Quay ( cy, Cei Newydd) is a seaside town (and electoral ward) in Ceredigion, Wales, with a resident population of around 1,200 people, reducing to 1,082 at the 2011 census. Located south-west of Aberystwyth on Cardigan Bay with a harbour a ...

in Cardiganshire (Ceredigion), where they rented Majoda, a wood and asbestos bungalow on the cliffs overlooking Cardigan Bay. It was there that Thomas wrote the radio piece ''Quite Early One Morning'', a sketch for his later work, ''Under Milk Wood''.Ferris (1989), p. 213 Of the poetry written at this time, of note is "Fern Hill", believed to have been started while living in New Quay, but completed at Blaencwm in mid-1945.Ferris (1989), p. 214John Brinnin in his 1956 book, ''Dylan Thomas in America'' (p. 104) states that on a visit to Laugharne in 1951 he was shown "more than two hundred separate and distinct versions of the poem (''Fern Hill'')" by Thomas. Thomas' nine months in New Quay, said first biographer, Constantine FitzGibbon, were "a second flowering, a period of fertility that recalls the earliest days…ith a

The Ith () is a ridge in Germany's Central Uplands which is up to 439 m high. It lies about 40 km southwest of Hanover and, at 22 kilometres, is the longest line of crags in North Germany.

Geography

Location

The Ith is immediatel ...

great outpouring of poems", as well as a good deal of other material. His second biographer, Paul Ferris, agreed: "On the grounds of output, the bungalow deserves a plaque of its own." Thomas’ third biographer, George Tremlett, concurred, describing the time in New Quay as “one of the most creative periods of Thomas’s life.” Professor Walford Davies, who co-edited the 1995 definitive edition of the play, has noted that New Quay "was crucial in supplementing the gallery of characters Thomas had to hand for writing ''Under Milk Wood''."

Broadcasting years, 1945–1949

Although Thomas had previously written for the BBC, it was a minor and intermittent source of income. In 1943, he wrote and recorded a 15-minute talk titled "Reminiscences of Childhood" for the Welsh BBC. In December 1944, he recorded ''Quite Early One Morning'' (produced by

Although Thomas had previously written for the BBC, it was a minor and intermittent source of income. In 1943, he wrote and recorded a 15-minute talk titled "Reminiscences of Childhood" for the Welsh BBC. In December 1944, he recorded ''Quite Early One Morning'' (produced by Aneirin Talfan Davies

Aneirin Talfan Davies (11 May 1909 – 14 July 1980) was a Welsh poet, broadcaster and literary critic.

Talfan Davies was brought up in Gorseinon. During the 1930s Davies worked in London as a pharmacist before returning to Wales and settling in S ...

, again for the Welsh BBC) but when Davies offered it for national broadcast BBC London turned it down. On 31 August 1945, the BBC Home Service broadcast ''Quite Early One Morning'' and, in the three years beginning in October 1945, Thomas made over a hundred broadcasts for the corporation. Thomas was employed not only for his poetry readings, but for discussions and critiques.

In the second half of 1945, Thomas began reading for the BBC Radio programme, ''Book of Verse'', broadcast weekly to the Far East. This provided Thomas with a regular income and brought him into contact with Louis MacNeice, a congenial drinking companion whose advice Thomas cherished.Read (1964), p. 116 On 29 September 1946, the BBC began transmitting the Third Programme

The BBC Third Programme was a national radio station produced and broadcast from 1946 until 1967, when it was replaced by Radio 3. It first went on the air on 29 September 1946 and quickly became one of the leading cultural and intellectual f ...

, a high-culture network which provided opportunities for Thomas. He appeared in the play ''Comus'' for the Third Programme, the day after the network launched, and his rich, sonorous voice led to character parts, including the lead in Aeschylus's ''Agamemnon

In Greek mythology, Agamemnon (; grc-gre, Ἀγαμέμνων ''Agamémnōn'') was a king of Mycenae who commanded the Greeks during the Trojan War. He was the son, or grandson, of King Atreus and Queen Aerope, the brother of Menelaus, the ...

'' and Satan in an adaptation of '' Paradise Lost''. Thomas remained a popular guest on radio talk shows for the BBC, who regarded him as "useful should a younger generation poet be needed". He had an uneasy relationship with BBC management and a staff job was never an option, with drinking cited as the problem. Despite this, Thomas became a familiar radio voice and within Britain was "in every sense a celebrity".

By late September 1945, the Thomases had left Wales and were living with various friends in London. In December, they moved to Oxford to live in a summerhouse on the banks of the Cherwell. It belonged to the historian, A.J.P. Taylor

Alan John Percivale Taylor (25 March 1906 – 7 September 1990) was a British historian who specialised in 19th- and 20th-century European diplomacy. Both a journalist and a broadcaster, he became well known to millions through his televi ...

. His wife, Margaret, would prove to be Thomas’s most committed patron.

The publication of '' Deaths and Entrances'' in February 1946 was a major turning point for Thomas. Poet and critic Walter J. Turner commented in ''The Spectator

''The Spectator'' is a weekly British magazine on politics, culture, and current affairs. It was first published in July 1828, making it the oldest surviving weekly magazine in the world.

It is owned by Frederick Barclay, who also owns ''The ...

'', "This book alone, in my opinion, ranks him as a major poet".

Italy, South Leigh and Prague...

The following year, in April 1947, the Thomases travelled to Italy, after Thomas had been awarded aSociety of Authors

The Society of Authors (SoA) is a United Kingdom trade union for professional writers, illustrators and literary translators, founded in 1884 to protect the rights and further the interests of authors. , it represents over 12,000 members and ass ...

scholarship. They stayed first in villas near Rapallo

Rapallo ( , , ) is a municipality in the Metropolitan City of Genoa, located in the Liguria region of northern Italy.

As of 2017 it had 29,778 inhabitants. It lies on the Ligurian Sea coast, on the Tigullio Gulf, between Portofino and Chiav ...

and then Florence

Florence ( ; it, Firenze ) is a city in Central Italy and the capital city of the Tuscany Regions of Italy, region. It is the most populated city in Tuscany, with 383,083 inhabitants in 2016, and over 1,520,000 in its metropolitan area.Bilan ...

, before moving to a hotel in Rio Marina

Rio Marina is a ''frazione'' of the ''comune'' of Rio, in the Province of Livorno in the Italian region Tuscany, located on the island of Elba

Elba ( it, isola d'Elba, ; la, Ilva) is a Mediterranean island in Tuscany, Italy, from the coastal ...

on the island of Elba

Elba ( it, isola d'Elba, ; la, Ilva) is a Mediterranean island in Tuscany, Italy, from the coastal town of Piombino on the Italian mainland, and the largest island of the Tuscan Archipelago. It is also part of the Arcipelago Toscano Nationa ...

. On their return, Thomas and family moved, in September 1947, into the Manor House in South Leigh, just west of Oxford, found for him by Margaret Taylor. He continued with his work for the BBC, completed a number of film scripts and worked further on his ideas for ''Under Milk Wood'', including a discussion in late 1947 of ''The Village of the Mad'' (as the play was then called) with the BBC producer Philip Burton. He later recalled that, during the meeting, Thomas had discussed his ideas for having a blind narrator, an organist who played for a dog and two lovers who wrote to each other every day but never met.

In March 1949 Thomas travelled to Prague

Prague ( ; cs, Praha ; german: Prag, ; la, Praga) is the capital and List of cities in the Czech Republic, largest city in the Czech Republic, and the historical capital of Bohemia. On the Vltava river, Prague is home to about 1.3 milli ...

. He had been invited by the Czech government to attend the inauguration of the Czechoslovak Writers' Union. Jiřina Hauková, who had previously published translations of some of Thomas's poems, was his guide and interpreter. In her memoir, Hauková recalls that at a party in Prague, Thomas "narrated the first version of his radio play ''Under Milk Wood''." She describes how he outlined the plot about a town that was declared insane, mentioning the organist who played for sheep and goats and the baker with two wives.

...and back to Laugharne

A month later, in May 1949, Thomas and his family moved to his final home, the Boat House at Laugharne, purchased for him at a cost of £2,500 in April 1949 by Margaret Taylor. Thomas acquired a garage a hundred yards from the house on a cliff ledge which he turned into his writing shed, and where he wrote several of his most acclaimed poems. He also rented "Pelican House" opposite his regular drinking den,Brown's Hotel

Brown's Hotel is a luxury hotel in Mayfair, London, established in 1837 and owned by Rocco Forte Hotels since 3 July 2003. It is considered one of London's oldest existing hotels.

History

Brown's Hotel was founded in 1837, by James and Sarah Br ...

, for his parents who lived there from 1949 until 1953.

Caitlin gave birth to their third child, a boy named Colm Garan Hart, on 25 July 1949.

In October, the New Zealand poet, Allen Curnow, came to visit Thomas at the Boat House, who took him to his writing shed and "fished out a draft to show me of the unfinished ''Under Milk Wood''" that was, says Curnow, titled ''The Town That Was Mad''. This is the first known sighting of the script of the play that was to become ''Under Milk Wood''.

America, Iran...and ''Under Milk Wood'', 1950–1953

American poet John Brinnin invited Thomas to New York, where in February 1950 they embarked on a lucrative three-month tour of arts centres and campuses. The tour, which began in front of an audience of a thousand at the Kaufmann Auditorium of the Poetry Centre in New York, took in about 40 venues.FitzGibbon, in his 1965 biography, lists 39 venues visited in the first U.S. trip, compiled with the help of John Brinnin, but accepts that some locations may have been missed. During the tour, Thomas was invited to many parties and functions and on several occasions became drunk – going out of his way to shock people – and was a difficult guest. Thomas drank before some of his readings, though it is argued he may have pretended to be more affected by it than he actually was. The writer Elizabeth Hardwick recalled how intoxicating a performer he was and how the tension would build before a performance: "Would he arrive only to break down on the stage? Would some dismaying scene take place at the faculty party? Would he be offensive, violent, obscene?" Caitlin said in her memoir, "Nobody ever needed encouragement less, and he was drowned in it." On returning to Britain, Thomas began work on two further poems, "In the white giant's thigh", which he read on the ''Third Programme'' in September 1950, and the incomplete "In country heaven". In October, Thomas sent a draft of the first 39 pages of 'The Town That Was Mad' to the BBC. The task of seeing this work through to production as ''Under Milk Wood'' was assigned to the BBC'sDouglas Cleverdon

Thomas Douglas James Cleverdon (17 January 1903 – 1 October 1987) was an English radio producer and bookseller. In both fields he was associated with numerous leading cultural figures.

Personal life

He was educated at Bristol Grammar School and ...

, who had been responsible for casting Thomas in 'Paradise Lost'.

Despite Cleverdon's urgings, the script slipped from Thomas's priorities and in January 1951 he went to Iran

Iran, officially the Islamic Republic of Iran, and also called Persia, is a country located in Western Asia. It is bordered by Iraq and Turkey to the west, by Azerbaijan and Armenia to the northwest, by the Caspian Sea and Turkmeni ...

to work on a film for the Anglo-Iranian Oil Company, an assignment which Callard has speculated was undertaken on behalf of British intelligence agencies. Thomas toured the country with the film crew, and his letters home vividly express his shock and anger with the poverty he saw around him. He also gave a reading at the British Council and talked with a number of Iranian intellectuals, including Ebrahim Golestan whose account of his meeting with Thomas has been translated and published. The film was never made, with Thomas returning to Wales in February, though his time in Iran allowed him to provide a few minutes of material for a BBC documentary, 'Persian Oil'.

Later that year, Thomas published two poems, which have been described as "unusually blunt." They were an ode, in the form of a villanelle

A villanelle, also known as villanesque,Kastner 1903 p. 279 is a nineteen-line poetic form consisting of five tercets followed by a quatrain. There are two refrains and two repeating rhymes, with the first and third line of the first tercet rep ...

, to his dying father, ''Do not go gentle into that good night

"Do not go gentle into that good night" is a poem in the form of a villanelle by Welsh poet Dylan Thomas (1914–1953), and is one of his best-known works. Though first published in the journal ''Botteghe Oscure'' in 1951, the poem was written in ...

'', and the ribald ''Lament''.

Although he had a range of wealthy patrons, including Margaret Taylor, Princess Marguerite Caetani

The House of Caetani, or Gaetani, is the name of an Italian noble family, originally from the city of Gaeta, connected by some to the lineage of the lords of the Duchy of Gaeta, as well as to the patrician Gaetani of the Republic of Pisa. It play ...

and Marged Howard-Stepney, Thomas was still in financial difficulty, and he wrote several begging letters to notable literary figures, including T. S. Eliot. Taylor was not keen on Thomas taking another trip to the United States, and thought that if he had a permanent address in London he would be able to gain steady work there. She bought a property, 54 Delancey Street, in Camden Town, and in late 1951 Thomas and Caitlin lived in the basement flat. Thomas would describe the flat as his "London house of horror" and did not return there after his 1952 tour of America.

Second tour January 20 to May 16, 1952

Thomas undertook a second tour of the United States in 1952, this time with Caitlin – after she had discovered he had been unfaithful on his earlier trip. They drank heavily, and Thomas began to suffer withgout

Gout ( ) is a form of inflammatory arthritis characterized by recurrent attacks of a red, tender, hot and swollen joint, caused by deposition of monosodium urate monohydrate crystals. Pain typically comes on rapidly, reaching maximal intens ...

and lung problems. The second tour was the most intensive of the four, taking in 46 engagements. The trip also resulted in Thomas recording his first poetry to vinyl, which Caedmon Records

Caedmon Audio and HarperCollins Audio are record label imprints of HarperCollins Publishers that specialize in audiobooks and other literary content. Formerly Caedmon Records, its marketing tag-line was Caedmon: a Third Dimension for the Printe ...

released in America later that year. One of his works recorded during this time, '' A Child's Christmas in Wales'', became his most popular prose work in America. The original 1952 recording of ''A Child's Christmas in Wales'' was a 2008 selection for the United States National Recording Registry, stating that it is "credited with launching the audiobook

An audiobook (or a talking book) is a recording of a book or other work being read out loud. A reading of the complete text is described as "unabridged", while readings of shorter versions are abridgements.

Spoken audio has been available in sc ...

industry in the United States".

A shortened version of the first half of ''The Town That Was Mad'' was published in ''Botteghe Oscure

''Botteghe Oscure'' was a literary journal that was published and edited in Rome by Marguerite Caetani (Princess di Bassiano) from 1948 to 1960.

History and profile

''Botteghe Oscure'' was established in 1948. The magazine was named after via d ...

'' in May 1952, with the title ''Llareggub. A Piece for Radio Perhaps''. Thomas had been in Laugharne for almost three years, but his half-play had made little progress since his time living in South Leigh. By the summer of 1952, the half-play’s title had been changed to ''Under Milk Wood'' because John Brinnin thought the title ''Llareggub'' would not attract American audiences. On November 6, 1952, Thomas wrote to the editor of ''Botteghe Oscure'' to explain why he hadn't been able to "finish the second half of my piece for you." He had failed shamefully, he said, to add to "my lonely half of a looney maybe-play".

On 10 November 1952 Thomas's last collection ''Collected Poems, 1934–1952'', was published by Dent; he was 38. It won the Foyle poetry prize. Reviewing the volume, critic Philip Toynbee

Theodore Philip Toynbee (25 June 1916 – 15 June 1981) was a British writer and communist. He wrote experimental novels, and distinctive verse novels, one of which was an epic called ''Pantaloon'', a work in several volumes, only some of whi ...

declared that "Thomas is the greatest living poet in the English language".Bold (1976), p. 61 Thomas's father died from pneumonia just before Christmas 1952. In the first few months of 1953, his sister died from liver cancer, one of his patrons took an overdose of sleeping pills, three friends died at an early age and Caitlin had an abortion.

Third tour April 21 to June 3, 1953

In April 1953, Thomas returned alone for a third tour of America. He performed a "work in progress" version of ''Under Milk Wood'', solo, for the first time atHarvard University

Harvard University is a private Ivy League research university in Cambridge, Massachusetts. Founded in 1636 as Harvard College and named for its first benefactor, the Puritan clergyman John Harvard, it is the oldest institution of high ...

on 3 May. A week later, the work was performed with a full cast at the Poetry Centre in New York. He met the deadline only after being locked in a room by Brinnin's assistant, Liz Reitell, and he was still editing the script on the afternoon of the performance; its last lines were handed to the actors as they were putting on their makeup.

During this penultimate tour, Thomas met the composer Igor Stravinsky who had become an admirer after having been introduced to his poetry by W. H. Auden

Wystan Hugh Auden (; 21 February 1907 – 29 September 1973) was a British-American poet. Auden's poetry was noted for its stylistic and technical achievement, its engagement with politics, morals, love, and religion, and its variety in ...

. They had discussions about collaborating on a "musical theatrical work" for which Thomas would provide the libretto on the theme of "the rediscovery of love and language in what might be left after the world after the bomb." The shock of Thomas's death later in the year moved Stravinsky to compose his ''In Memoriam Dylan Thomas'' for tenor, string quartet and four trombones. The first performance in Los Angeles

Los Angeles ( ; es, Los Ángeles, link=no , ), often referred to by its initials L.A., is the List of municipalities in California, largest city in the U.S. state, state of California and the List of United States cities by population, sec ...

in 1954 was introduced with a tribute to Thomas from Aldous Huxley

Aldous Leonard Huxley (26 July 1894 – 22 November 1963) was an English writer and philosopher. He wrote nearly 50 books, both novels and non-fiction works, as well as wide-ranging essays, narratives, and poems.

Born into the prominent Huxle ...

.

Thomas spent the last nine or ten days of his third tour in New York mostly in the company of Reitell, with whom he had an affair.Ferris (1989), p. 321 During this time, Thomas fractured his arm falling down a flight of stairs when drunk. Reitell's doctor, Milton Feltenstein, put his arm in plaster and treated him for gout and gastritis.

After returning home, Thomas worked on ''Under Milk Wood'' in Laugharne. Aeronwy, his daughter, noticed that his health had “visibly deteriorated...I could hear his racking cough. Every morning he had a prolonged coughing attack...The coughing was nothing new but it seemed worse than before.”

Thomas sent the original manuscript to Douglas Cleverdon on 15 October 1953. It was copied and returned to Thomas, who lost it in a pub in London and required a duplicate to take to America.Ferris (1989), p. 328 Thomas flew to the States on 19 October 1953 for what would be his final tour. He died in New York before the BBC could record ''Under Milk Wood''. Richard Burton

Richard Burton (; born Richard Walter Jenkins Jr.; 10 November 1925 – 5 August 1984) was a Welsh actor. Noted for his baritone voice, Burton established himself as a formidable Shakespearean actor in the 1950s, and he gave a memorable pe ...

starred in the first broadcast in 1954, and was joined by Elizabeth Taylor in a subsequent film. In 1954, the play won the Prix Italia

The Prix Italia is an international Television, Radio-broadcasting and Web award. It was established in 1948 by RAI – Radiotelevisione Italiana (in 1948, RAI had the denomination RAI – Radio Audizioni Italiane) in Capri and is honoured with the ...

for literary or dramatic programmes.

The Final Tour: Death in New York

Thomas left Laugharne on 9 October 1953 on the first leg of his fourth trip to America. He called on his mother, Florence, to say goodbye: "He always felt that he had to get out from this country because of his chest being so bad."Thomas, D. N. (2008) p46 Thomas had suffered from chest problems for most of his life, though they began in earnest soon after he moved in May 1949 to the Boat House at Laugharne – the "bronchial heronry", as he called it. Within weeks of moving in, he visited a local doctor, who prescribed medicine for both his chest and throat.

Whilst waiting in London before his flight, Thomas stayed with the comedian

Thomas left Laugharne on 9 October 1953 on the first leg of his fourth trip to America. He called on his mother, Florence, to say goodbye: "He always felt that he had to get out from this country because of his chest being so bad."Thomas, D. N. (2008) p46 Thomas had suffered from chest problems for most of his life, though they began in earnest soon after he moved in May 1949 to the Boat House at Laugharne – the "bronchial heronry", as he called it. Within weeks of moving in, he visited a local doctor, who prescribed medicine for both his chest and throat.

Whilst waiting in London before his flight, Thomas stayed with the comedian Harry Locke

Harry Locke (10 December 1913 – 7 September 1987) was an English character actor.

He was born and died in London. He married Joan Cowderoy in 1943 and Cordelia Sewell in 1952. He was a good friend of the poet Dylan Thomas. Their friendship in ...

and worked on ''Under Milk Wood''. Locke noted that Thomas was having trouble with his chest, "terrible" coughing fits that made him go purple in the face. He was also using an inhaler to help his breathing. There were reports, too, that Thomas was also having blackouts. His visit to the BBC producer Philip Burton, a few days before he left for New York, was interrupted by a blackout. On his last night in London, he had another in the company of his fellow poet Louis MacNeice.

Thomas arrived in New York on 20 October 1953 to undertake further performances of ''Under Milk Wood'', organised by John Brinnin, his American agent and Director of the Poetry Centre. Brinnin did not travel to New York but remained in Boston

Boston (), officially the City of Boston, is the state capital and most populous city of the Commonwealth of Massachusetts, as well as the cultural and financial center of the New England region of the United States. It is the 24th- mo ...

to write. He handed responsibility to his assistant, Liz Reitell. She met Thomas at Idlewild Airport and was shocked at his appearance. He looked pale, delicate and shaky, not his usual robust self: "He was very ill when he got here."Thomas, D. N. (2008) p57 After being taken by Reitell to check in at the Chelsea Hotel, Thomas took the first rehearsal of ''Under Milk Wood''. They then went to the White Horse Tavern in Greenwich Village, before returning to the Chelsea Hotel.

The next day, Reitell invited him to her apartment, but he declined. They went sightseeing, but Thomas felt unwell and retired to his bed for the rest of the afternoon. Reitell gave him half a grain (32.4 milligrams) of phenobarbitone

Phenobarbital, also known as phenobarbitone or phenobarb, sold under the brand name Luminal among others, is a medication of the barbiturate type. It is recommended by the World Health Organization (WHO) for the treatment of certain types of ep ...

to help him sleep and spent the night at the hotel with him. Two days later, on 23 October, at the third rehearsal, Thomas said he was too ill to take part, but he struggled on, shivering and burning with fever, before collapsing on the stage.

The following day, 24 October, Reitell took Thomas to see her doctor, Milton Feltenstein, who administered cortisone injections and Thomas made it through the first performance that evening, but collapsed immediately afterwards. "This circus out there," he told a friend who had come back-stage, "has taken the life out of me for now." Reitell later said that Feltenstein was "rather a wild doctor who thought injections would cure anything."

At the next performance on 25 October, his fellow actors realised that Thomas was very ill: "He was desperately ill…we didn't think that he would be able to do the last performance because he was so ill…Dylan literally couldn't speak he was so ill…still my greatest memory of it is that he had no voice."

On the evening of 27 October, Thomas attended his 39th birthday party but felt unwell and returned to his hotel after an hour.Ferris (1989), p. 332 The next day, he took part in ''Poetry and the Film'', a recorded symposium at

At the next performance on 25 October, his fellow actors realised that Thomas was very ill: "He was desperately ill…we didn't think that he would be able to do the last performance because he was so ill…Dylan literally couldn't speak he was so ill…still my greatest memory of it is that he had no voice."

On the evening of 27 October, Thomas attended his 39th birthday party but felt unwell and returned to his hotel after an hour.Ferris (1989), p. 332 The next day, he took part in ''Poetry and the Film'', a recorded symposium at Cinema 16

Cinema 16 was a New York City–based film society founded by Amos Vogel. From 1947-63, he and his wife, Marcia, ran the most successful and influential membership film society in North American history, at its height boasting 7000 members.

Histo ...

.

A turning point came on 2 November. Air pollution

Air pollution is the contamination of air due to the presence of substances in the atmosphere that are harmful to the health of humans and other living beings, or cause damage to the climate or to materials. There are many different typ ...

in New York had risen significantly and exacerbated chest illnesses such as Thomas had. By the end of the month, over 200 New Yorkers had died from the smog.

On 3 November, Thomas spent most of the day in his room, entertaining various friends. He went out in the evening to keep two drink appointments. After returning to the hotel, he went out again for a drink at 2 am. After drinking at the White Horse, Thomas returned to the Hotel Chelsea, declaring, "I've had eighteen straight whiskies. I think that's the record!" The barman and the owner of the pub who served him later commented that Thomas could not have drunk more than half that amount.

Thomas had an appointment at a clam

Clam is a common name for several kinds of bivalve molluscs. The word is often applied only to those that are edible and live as infauna, spending most of their lives halfway buried in the sand of the seafloor or riverbeds. Clams have two shel ...

house in New Jersey

New Jersey is a state in the Mid-Atlantic and Northeastern regions of the United States. It is bordered on the north and east by the state of New York; on the east, southeast, and south by the Atlantic Ocean; on the west by the Delaware ...

with Ruthven Todd on 4 November. When Todd telephoned the Chelsea that morning, Thomas said he was feeling ill and postponed the engagement. Todd thought he sounded "terrible". The poet, Harvey Breit, was another to phone that morning. He thought that Thomas sounded "bad". Thomas's voice, recalled Breit, was "low and hoarse". He had wanted to say: "You sound as though from the tomb", but instead he told Thomas that he sounded like Louis Armstrong.

Later, Thomas went drinking with Reitell at the White Horse and, feeling sick again, returned to the hotel. Feltenstein came to see him three times that day, administering the cortisone secretant ACTH

Adrenocorticotropic hormone (ACTH; also adrenocorticotropin, corticotropin) is a polypeptide tropic hormone produced by and secreted by the anterior pituitary gland. It is also used as a medication and diagnostic agent. ACTH is an important c ...

by injection and, on his third visit, half a grain (32.4 milligrams) of morphine sulphate, which affected Thomas's breathing. Reitell became increasingly concerned and telephoned Feltenstein for advice. He suggested she get male assistance, so she called upon the painter Jack Heliker, who arrived before 11 pm. At midnight on 5 November, Thomas's breathing became more difficult and his face turned blue. Reitell phoned Feltenstein who arrived at the hotel at about 1 am, and called for an ambulance.Ruthven Todd states in his letter dated 23 November that the police were called, who then called the ambulance, while Ferris in his 1989 biography writes that Feltenstein was summoned again and called the ambulance. D. N. Thomas concurs that Feltenstein eventually returned at 1 am and summoned the ambulance. It then took another hour for the ambulance to arrive at St. Vincent's, even though it was only a few blocks from the Chelsea.

Thomas was admitted to the emergency ward at St Vincent's Hospital at 1:58 am. He was comatose, and his medical notes state that "the impression upon admission was acute alcoholic encephalopathy damage to the brain by alcohol, for which the patient was treated without response". Feltenstein then took control of Thomas's care, even though he did not have admitting rights at St. Vincent's. The hospital's senior brain specialist, Dr. C.G. Gutierrez-Mahoney, was not called to examine Thomas until the afternoon of 6 November, some thirty-six hours after Thomas's admission.

Caitlin flew to America the following day and was taken to the hospital, by which time a tracheotomy

Tracheotomy (, ), or tracheostomy, is a surgical airway management procedure which consists of making an incision (cut) on the anterior aspect (front) of the neck and opening a direct airway through an incision in the trachea (windpipe). The r ...

had been performed. Her reported first words were, "Is the bloody man dead yet?" She was allowed to see Thomas only for 40 minutes in the morning but returned in the afternoon and, in a drunken rage, threatened to kill John Brinnin. When she became uncontrollable, she was put in a straitjacket and committed, by Feltenstein, to the River Crest private psychiatric detox clinic on Long Island.

It is now believed that Thomas had been suffering from bronchitis

Bronchitis is inflammation of the bronchi (large and medium-sized airways) in the lungs that causes coughing. Bronchitis usually begins as an infection in the nose, ears, throat, or sinuses. The infection then makes its way down to the bronchi. ...

, pneumonia

Pneumonia is an inflammatory condition of the lung primarily affecting the small air sacs known as alveoli. Symptoms typically include some combination of productive or dry cough, chest pain, fever, and difficulty breathing. The severi ...

, emphysema and asthma

Asthma is a long-term inflammatory disease of the airways of the lungs. It is characterized by variable and recurring symptoms, reversible airflow obstruction, and easily triggered bronchospasms. Symptoms include episodes of wheezing, co ...

before his admission to St Vincent's. In their 2004 paper, ''Death by Neglect'', D. N. Thomas and Dr Simon Barton disclose that Thomas was found to have pneumonia when he was admitted to hospital in a coma. Doctors took three hours to restore his breathing, using artificial respiration and oxygen. Summarising their findings, they conclude: "The medical notes indicate that, on admission, Dylan's bronchial disease was found to be very extensive, affecting upper, mid and lower lung fields, both left and right." The forensic pathologist, Professor Bernard Knight

Bernard Henry Knight (born 3 May 1931) is a British forensic pathologist and writer. He became a Home Office pathologist in 1965 and was appointed Professor of Forensic Pathology, University of Wales College of Medicine, in 1980.

Early life

...

, concurs: "death was clearly due to a severe lung infection with extensive advanced bronchopneumonia...the severity of the chest infection, with greyish consolidated areas of well-established pneumonia, suggests that it had started before admission to hospital."

Thomas died at noon on 9 November, having never recovered from his coma. A nurse, and the poet John Berryman

John Allyn McAlpin Berryman (born John Allyn Smith, Jr.; October 25, 1914 – January 7, 1972) was an American poet and scholar. He was a major figure in American poetry in the second half of the 20th century and is considered a key figure in th ...

, were present with him at the time of death.

Aftermath

Rumours circulated of abrain haemorrhage

Intracerebral hemorrhage (ICH), also known as cerebral bleed, intraparenchymal bleed, and hemorrhagic stroke, or haemorrhagic stroke, is a sudden bleeding into the tissues of the brain, into its ventricles, or into both. It is one kind of bleed ...

, followed by competing reports of a mugging or even that Thomas had drunk himself to death. Later, speculation arose about drugs and diabetes

Diabetes, also known as diabetes mellitus, is a group of metabolic disorders characterized by a high blood sugar level ( hyperglycemia) over a prolonged period of time. Symptoms often include frequent urination, increased thirst and increased ...

. At the post-mortem

An autopsy (post-mortem examination, obduction, necropsy, or autopsia cadaverum) is a surgical procedure that consists of a thorough examination of a corpse by dissection to determine the cause, mode, and manner of death or to evaluate any di ...

, the pathologist found three causes of death – pneumonia

Pneumonia is an inflammatory condition of the lung primarily affecting the small air sacs known as alveoli. Symptoms typically include some combination of productive or dry cough, chest pain, fever, and difficulty breathing. The severi ...

, brain swelling and a fatty liver

Fatty liver disease (FLD), also known as hepatic steatosis, is a condition where excess fat builds up in the liver. Often there are no or few symptoms. Occasionally there may be tiredness or pain in the upper right side of the abdomen. Complicat ...

. Despite the poet's heavy drinking, his liver showed no sign of cirrhosis

Cirrhosis, also known as liver cirrhosis or hepatic cirrhosis, and end-stage liver disease, is the impaired liver function caused by the formation of scar tissue known as fibrosis due to damage caused by liver disease. Damage causes tissue rep ...

.

The publication of John Brinnin's 1955 biography ''Dylan Thomas in America'' cemented Thomas's legacy as the "doomed poet"; Brinnin focuses on Thomas's last few years and paints a picture of him as a drunk and a philanderer. Later biographies have criticised Brinnin's view, especially his coverage of Thomas's death. David Thomas in ''Fatal Neglect: Who Killed Dylan Thomas?'' claims that Brinnin, along with Reitell and Feltenstein, were culpable. FitzGibbon's 1965 biography ignores Thomas's heavy drinking and skims over his death, giving just two pages in his detailed book to Thomas's demise. Ferris in his 1989 biography includes Thomas's heavy drinking, but is more critical of those around him in his final days and does not draw the conclusion that he drank himself to death. Many sources have criticised Feltenstein's role and actions, especially his incorrect diagnosis of delirium tremens and the high dose of morphine he administered. Dr C. G. de Gutierrez-Mahoney, the doctor who treated Thomas while at St. Vincents, concluded that Feltenstein's failure to see that Thomas was gravely ill and have him admitted to hospital sooner "was even more culpable than his use of morphine".

Caitlin Thomas's autobiographies, ''Caitlin Thomas – Leftover Life to Kill'' (1957) and ''My Life with Dylan Thomas: Double Drink Story'' (1997), describe the effects of alcohol on the poet and on their relationship. "Ours was not only a love story, it was a drink story, because without alcohol it would never had got on its rocking feet", she wrote, and "The bar was our altar." Biographer Andrew Lycett

Andrew Michael Duncan Lycett (born 1948) FRSL is an English biographer and journalist.

Early life

Born at Stamford, Lincolnshire to Peter Norman Lycett Lycett and Joan Mary Duncan (née Day), Lycett spent some of his childhood in Tanganyika, wher ...

ascribed the decline in Thomas's health to an alcoholic co-dependent relationship with his wife, who deeply resented his extramarital affairs. In contrast, Dylan biographers Andrew Sinclair

Andrew Annandale Sinclair FRSL FRSA (21 January 1935 – 30 May 2019) was a British novelist, historian, biographer, critic, filmmaker, and a publisher of classic and modern film scripts. He has been described as a "writer of extraordinary flu ...

and George Tremlett express the view that Thomas was not an alcoholic. Tremlett argues that many of Thomas's health issues stemmed from undiagnosed diabetes

Diabetes, also known as diabetes mellitus, is a group of metabolic disorders characterized by a high blood sugar level ( hyperglycemia) over a prolonged period of time. Symptoms often include frequent urination, increased thirst and increased ...

.

Thomas died intestate

Intestacy is the condition of the estate of a person who dies without having in force a valid will or other binding declaration. Alternatively this may also apply where a will or declaration has been made, but only applies to part of the estat ...