Dr Crippen on:

[Wikipedia]

[Google]

[Amazon]

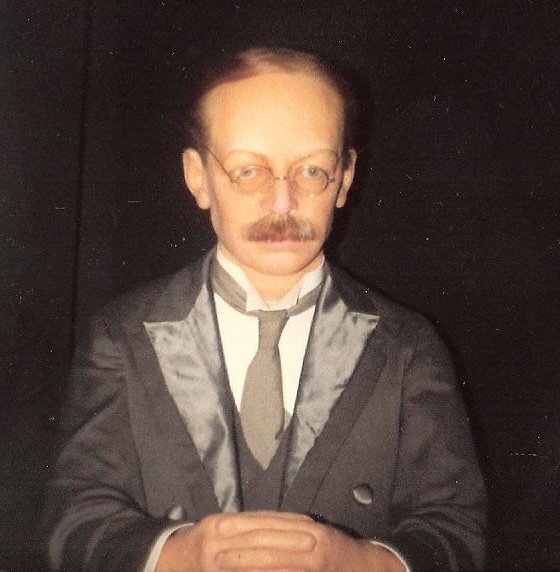

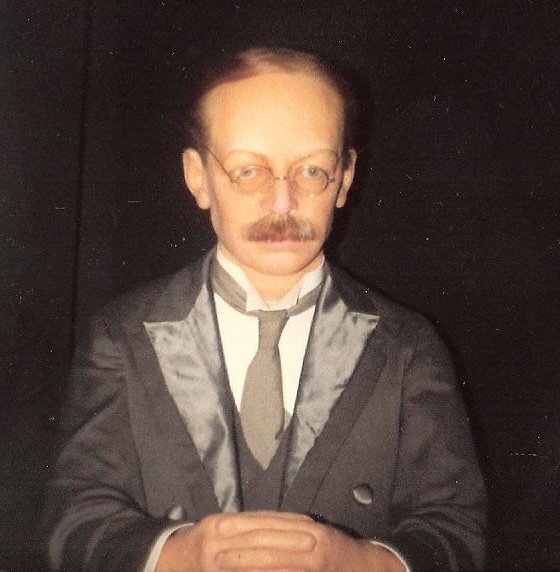

Hawley Harvey Crippen (September 11, 1862 – November 23, 1910), usually known as Dr. Crippen, was an American homeopath, ear and eye specialist and medicine dispenser. He was hanged in

''Oxford Dictionary of National Biography''

/ref> Crippen studied first at the University of Michigan Homeopathic Medical School and graduated from the Cleveland Homeopathic Medical College in 1884. Crippen's first wife, Charlotte, died of a

After a party at their home on 31 January 1910, Cora disappeared. Hawley Crippen claimed that she had returned to the United States and later added that she had died and had been cremated in California. Meanwhile, his lover, Ethel "Le Neve" Neave, moved into Hilldrop Crescent and began openly wearing Cora's clothes and jewelry.

Police first heard of Cora's disappearance from her friend, the strongwoman Kate Williams, better known as Vulcana, but began to take the matter more seriously when asked to investigate by a personal friend of

After a party at their home on 31 January 1910, Cora disappeared. Hawley Crippen claimed that she had returned to the United States and later added that she had died and had been cremated in California. Meanwhile, his lover, Ethel "Le Neve" Neave, moved into Hilldrop Crescent and began openly wearing Cora's clothes and jewelry.

Police first heard of Cora's disappearance from her friend, the strongwoman Kate Williams, better known as Vulcana, but began to take the matter more seriously when asked to investigate by a personal friend of

Meanwhile, Crippen and Le Neve were crossing the Atlantic on the ''Montrose'', with Le Neve disguised as a boy. Captain Henry George Kendall recognised the fugitives and, just before steaming beyond the range of his ship-board transmitter, had telegraphist Lawrence Ernest Hughes send a wireless

Meanwhile, Crippen and Le Neve were crossing the Atlantic on the ''Montrose'', with Le Neve disguised as a boy. Captain Henry George Kendall recognised the fugitives and, just before steaming beyond the range of his ship-board transmitter, had telegraphist Lawrence Ernest Hughes send a wireless

Crippen was tried at the

Crippen was tried at the

* The murder inspired

* The murder inspired

Pentonville Prison

HM Prison Pentonville (informally "The Ville") is an English Category B men's prison, operated by His Majesty's Prison Service. Pentonville Prison is not in Pentonville, but is located further north, on the Caledonian Road in the Barnsbury ar ...

in London for the murder of his wife Cora Henrietta Crippen. Crippen was one of the first criminals to be captured with the aid of wireless telegraphy

Wireless telegraphy or radiotelegraphy is transmission of text messages by radio waves, analogous to electrical telegraphy using cables. Before about 1910, the term ''wireless telegraphy'' was also used for other experimental technologies for ...

.

Early life and career

Crippen was born inColdwater, Michigan

Coldwater is a city in Branch County, Michigan, United States. As of the 2010 census, the city population was 10,945. It is the county seat of Branch County, located in the center of the southern border of Michigan. The city is surrounded by Co ...

, to Andresse Skinner (1835-1909) and Myron Augustus Crippen (1835-1910), a merchant."Hawley Harvey Crippen"''Oxford Dictionary of National Biography''

/ref> Crippen studied first at the University of Michigan Homeopathic Medical School and graduated from the Cleveland Homeopathic Medical College in 1884. Crippen's first wife, Charlotte, died of a

stroke

A stroke is a disease, medical condition in which poor cerebral circulation, blood flow to the brain causes cell death. There are two main types of stroke: brain ischemia, ischemic, due to lack of blood flow, and intracranial hemorrhage, hemorr ...

in 1892, and Crippen entrusted his parents, living in California

California is a state in the Western United States, located along the Pacific Coast. With nearly 39.2million residents across a total area of approximately , it is the most populous U.S. state and the 3rd largest by area. It is also the m ...

, with the care of his son, Hawley Otto (1889-1974).

Having qualified as a homeopath, Crippen started to practice in New York

New York most commonly refers to:

* New York City, the most populous city in the United States, located in the state of New York

* New York (state), a state in the northeastern United States

New York may also refer to:

Film and television

* '' ...

, where in 1894 he married his second wife, Corrine "Cora" Turner, who performed under the stage name Belle Elmore, and was born Kunigunde Mackamotski to a German mother and a Polish-Russian father. She was a would-be music hall singer who openly had affairs. In 1894, Crippen started working for Dr Munyon's, a homeopathic pharmaceutical company.

In 1897, Crippen moved to England

England is a country that is part of the United Kingdom. It shares land borders with Wales to its west and Scotland to its north. The Irish Sea lies northwest and the Celtic Sea to the southwest. It is separated from continental Europe ...

with his wife, although his US medical qualifications were not sufficient to allow him to practise as a doctor in the UK. As Crippen continued working as a distributor of patent medicines, Cora socialised with a number of variety players of the time, including Lil Hawthorne of The Hawthorne Sisters and Lil's husband/manager, John Nash.

Crippen was sacked by Munyon's in 1899 for spending too much time managing his wife's stage career. He became manager of Drouet's Institution for the Deaf, where he hired Ethel Le Neve, a young typist, in 1900. By 1905, the two were having an affair. After living at various addresses in London

London is the capital and List of urban areas in the United Kingdom, largest city of England and the United Kingdom, with a population of just under 9 million. It stands on the River Thames in south-east England at the head of a estuary dow ...

, the Crippens finally moved in 1905 to 39 Hilldrop Crescent, Camden Road, Holloway, London, where they took in lodgers to augment Crippen's meagre income. Cora had an affair with one of these lodgers, and in turn, Crippen took Le Neve as his mistress in 1908.

Murder and disappearance

After a party at their home on 31 January 1910, Cora disappeared. Hawley Crippen claimed that she had returned to the United States and later added that she had died and had been cremated in California. Meanwhile, his lover, Ethel "Le Neve" Neave, moved into Hilldrop Crescent and began openly wearing Cora's clothes and jewelry.

Police first heard of Cora's disappearance from her friend, the strongwoman Kate Williams, better known as Vulcana, but began to take the matter more seriously when asked to investigate by a personal friend of

After a party at their home on 31 January 1910, Cora disappeared. Hawley Crippen claimed that she had returned to the United States and later added that she had died and had been cremated in California. Meanwhile, his lover, Ethel "Le Neve" Neave, moved into Hilldrop Crescent and began openly wearing Cora's clothes and jewelry.

Police first heard of Cora's disappearance from her friend, the strongwoman Kate Williams, better known as Vulcana, but began to take the matter more seriously when asked to investigate by a personal friend of Scotland Yard

Scotland Yard (officially New Scotland Yard) is the headquarters of the Metropolitan Police, the territorial police force responsible for policing Greater London's 32 boroughs, but not the City of London, the square mile that forms London's ...

Superintendent Frank Froest, John Nash and his entertainer wife, Lil Hawthorne. The house was searched, but nothing was found, and Crippen was interviewed by Chief Inspector Walter Dew. Crippen admitted that he had fabricated the story about his wife having died and explained that he had made it up in order to avoid any personal embarrassment because she had in fact left him and fled to America with one of her lovers, a music hall actor named Bruce Miller. After the interview (and a quick search of the house), Dew was satisfied with Crippen's story. However, Crippen and Le Neve did not know this and fled in panic to Brussels

Brussels (french: Bruxelles or ; nl, Brussel ), officially the Brussels-Capital Region (All text and all but one graphic show the English name as Brussels-Capital Region.) (french: link=no, Région de Bruxelles-Capitale; nl, link=no, Bruss ...

, where they spent the night at a hotel. The following day, they went to Antwerp

Antwerp (; nl, Antwerpen ; french: Anvers ; es, Amberes) is the largest city in Belgium by area at and the capital of Antwerp Province in the Flemish Region. With a population of 520,504,

and boarded the Canadian Pacific

The Canadian Pacific Railway (french: Chemin de fer Canadien Pacifique) , also known simply as CPR or Canadian Pacific and formerly as CP Rail (1968–1996), is a Canadian Class I railway incorporated in 1881. The railway is owned by Canadi ...

liner for Canada

Canada is a country in North America. Its ten provinces and three territories extend from the Atlantic Ocean to the Pacific Ocean and northward into the Arctic Ocean, covering over , making it the world's second-largest country by to ...

.

Their disappearance led the police at Scotland Yard

Scotland Yard (officially New Scotland Yard) is the headquarters of the Metropolitan Police, the territorial police force responsible for policing Greater London's 32 boroughs, but not the City of London, the square mile that forms London's ...

to perform another three searches of the house. During the fourth and final search, they found the torso of a human body buried under the brick floor of the basement. William Willcox (later Sir William Willcox, senior scientific analyst to the Home Office) found traces of the calming drug scopolamine

Scopolamine, also known as hyoscine, or Devil's Breath, is a natural or synthetically produced tropane alkaloid and anticholinergic drug that is formally used as a medication for treating motion sickness and postoperative nausea and vomi ...

in the torso. The remains were identified as being Cora by a piece of skin from the abdomen; the head, limbs, and skeleton were never recovered. Her remains were later interred at the St Pancras and Islington Cemetery, East Finchley

East Finchley is an area in North London, immediately north of Hampstead Heath. Like neighbouring Muswell Hill it straddles the London Boroughs of Barnet and Haringey, with most of East Finchley falling into the London Borough of Barnet. It ...

.

Transatlantic arrest

Meanwhile, Crippen and Le Neve were crossing the Atlantic on the ''Montrose'', with Le Neve disguised as a boy. Captain Henry George Kendall recognised the fugitives and, just before steaming beyond the range of his ship-board transmitter, had telegraphist Lawrence Ernest Hughes send a wireless

Meanwhile, Crippen and Le Neve were crossing the Atlantic on the ''Montrose'', with Le Neve disguised as a boy. Captain Henry George Kendall recognised the fugitives and, just before steaming beyond the range of his ship-board transmitter, had telegraphist Lawrence Ernest Hughes send a wireless telegram

Telegraphy is the long-distance transmission of messages where the sender uses symbolic codes, known to the recipient, rather than a physical exchange of an object bearing the message. Thus flag semaphore is a method of telegraphy, whereas ...

to the British authorities: "Have strong suspicions that Crippen London cellar murderer and accomplice are among saloon passengers. Mustache taken off growing beard. Accomplice dressed as boy. Manner and build undoubtedly a girl." Had Crippen travelled third class, he probably would have escaped Kendall's notice. Dew boarded a faster White Star liner, , from Liverpool

Liverpool is a City status in the United Kingdom, city and metropolitan borough in Merseyside, England. With a population of in 2019, it is the List of English districts by population, 10th largest English district by population and its E ...

, arrived in Quebec

Quebec ( ; )According to the Canadian government, ''Québec'' (with the acute accent) is the official name in Canadian French and ''Quebec'' (without the accent) is the province's official name in Canadian English is one of the thirte ...

, Canada, ahead of Crippen, and contacted the Canadian authorities.

As the ''Montrose'' entered the St. Lawrence River, Dew came aboard disguised as a pilot. Canada was then still a dominion

The term ''Dominion'' is used to refer to one of several self-governing nations of the British Empire.

"Dominion status" was first accorded to Canada, Australia, New Zealand, Newfoundland, South Africa, and the Irish Free State at the 1926 ...

within the British Empire. If Crippen, an American citizen, had sailed to the United States instead, even if he had been recognised, it would have taken extradition

Extradition is an action wherein one jurisdiction delivers a person accused or convicted of committing a crime in another jurisdiction, over to the other's law enforcement. It is a cooperative law enforcement procedure between the two jurisdi ...

proceedings to bring him to trial. Kendall invited Crippen to meet the pilots as they came aboard. Dew removed his pilot's cap and said, "Good morning, Dr. Crippen. Do you know me? I'm Chief Inspector Dew from Scotland Yard." After a pause, Crippen replied, "Thank God it's over. The suspense has been too great. I couldn't stand it any longer." He then held out his wrists for the handcuffs. Crippen and Le Neve were arrested on board the ''Montrose'' on 31 July 1910. Crippen was returned to the United Kingdom on board the .

Trial

Crippen was tried at the

Crippen was tried at the Old Bailey

The Central Criminal Court of England and Wales, commonly referred to as the Old Bailey after the street on which it stands, is a criminal court building in central London, one of several that house the Crown Court of England and Wales. The s ...

before the Lord Chief Justice, Lord Alverstone

Richard Everard Webster, 1st Viscount Alverstone, (22 December 1842 – 15 December 1915) was a British barrister, politician and judge who served in many high political and judicial offices.

Background and education

Webster was the second son ...

, on 18 October 1910. The proceedings lasted four days.

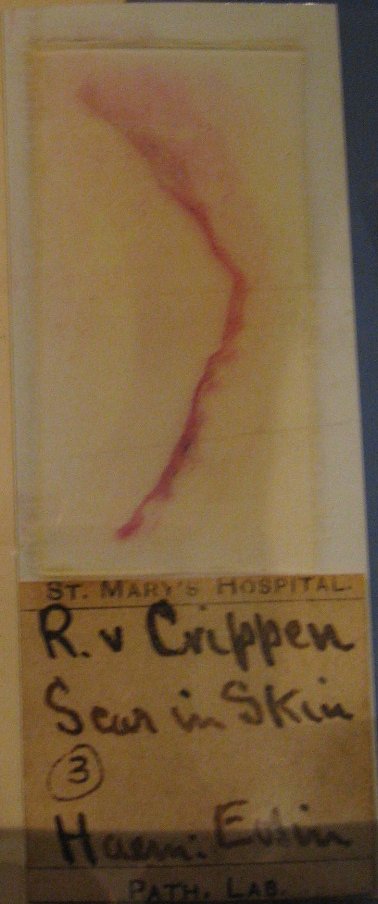

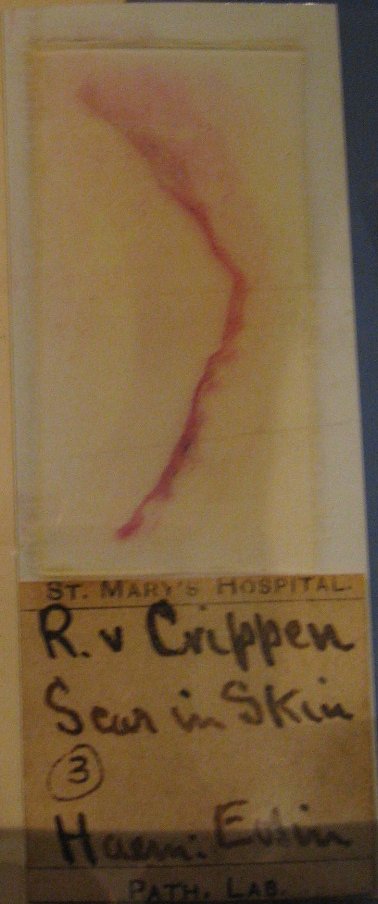

The first prosecution witnesses were pathologists. One of them, Bernard Spilsbury, testified they could not identify the torso remains or even discern whether they were male or female. However, Bernard Spilsbury found a piece of skin with what he claimed to be an abdominal scar consistent with Cora's medical history. Large quantities of the toxic compound scopalamine were found in the remains, and Crippen had purchased the drug before the murder from a local chemist.

Crippen's defence, led by Alfred Tobin

Sir Alfred Aspinall Tobin (26 December 1855 – 30 November 1939) was a British lawyer and judge who served as the Conservative Member of Parliament for Preston between 1910 and 1915.

Tobin's grandfather, Thomas Tobin, had been a prominent Liver ...

, maintained that Cora had fled to America with another man named Bruce Miller and that Cora and Hawley had been living at the house only since 1905, suggesting a previous owner of the house was responsible for the placement of the remains. The defence asserted that the abdominal scar identified by pathologist Spilsbury was really just folded tissue, for, among other things, it had hair follicles growing from it, something scar tissue could not have; Spilsbury observed that the sebaceous gland

A sebaceous gland is a microscopic exocrine gland in the skin that opens into a hair follicle to secrete an oily or waxy matter, called sebum, which lubricates the hair and skin of mammals. In humans, sebaceous glands occur in the greatest n ...

s appeared at the ends but not in the middle of the scar.

Other evidence presented by the prosecution included a piece of a man's pyjama top supposedly from a pair Cora had given Crippen a year earlier. The pyjama bottoms were found in Crippen's bedroom, but not the top. The fragment included the manufacturer's label, Jones Bros. Curlers, and bleached hair consistent with Cora's, were found with the remains.Elmsley, p. 42 Testimony from a Jones Bros. representative, the store that the pyjama top fragment came from, stated that the product was not sold prior to 1908, thus placing the date of manufacture well within the time period of when the Crippens occupied the house and when Cora gave the garment to Hawley the year before in 1909.

Throughout the proceedings and at his sentencing, Crippen showed no remorse for his wife, only concern for his lover's reputation. The jury found Crippen guilty of murder after just 27 minutes of deliberations. Le Neve was charged only with being an accessory after the fact and acquitted.

Although Crippen never gave any reason for killing his wife, several theories have been propounded. One was by the late Victorian and Edwardian barrister Edward Marshall Hall

Sir Edward Marshall Hall, (16 September 1858 – 24 February 1927) was an English barrister who had a formidable reputation as an orator. He successfully defended many people accused of notorious murders and became known as "The Great Defender ...

who believed that Crippen was using hyoscine

Scopolamine, also known as hyoscine, or Devil's Breath, is a natural or synthetically produced tropane alkaloid and anticholinergic drug that is formally used as a medication for treating motion sickness and postoperative nausea and vomi ...

on his wife as a depressant or anaphrodisiac but accidentally gave her an overdose and then panicked when she died. It is said that Hall declined to lead Crippen's defence because another theory was to be propounded.

In 1981, several British newspapers reported that Sir Hugh Rhys Rankin claimed to have met Ethel Le Neve in 1930 in Australia where she told him that Crippen murdered his wife because she had syphilis

Syphilis () is a sexually transmitted infection caused by the bacterium '' Treponema pallidum'' subspecies ''pallidum''. The signs and symptoms of syphilis vary depending in which of the four stages it presents (primary, secondary, latent, a ...

.

Execution

Crippen was hanged by John Ellis atPentonville Prison

HM Prison Pentonville (informally "The Ville") is an English Category B men's prison, operated by His Majesty's Prison Service. Pentonville Prison is not in Pentonville, but is located further north, on the Caledonian Road in the Barnsbury ar ...

, London at 9 am on Wednesday 23 November 1910.

Le Neve sailed to the United States before settling in Canada finding work as a typist. She returned to Britain in 1915 and died in 1967. At Crippen's request, a photograph of Le Neve was placed in his coffin and buried with him.

Although Crippen's grave in Pentonville's grounds is not marked by a stone, tradition has it that soon after his burial, a rose bush was planted over it. Some of his relatives in Michigan have begun lobbying for his remains to be repatriated to the United States.

Crippen's guilt

Questions have arisen about the investigation, trial and evidence that convicted Crippen in 1910. Dornford Yates, a junior barrister at the original trial, wrote in his memoirs '' As Berry and I Were Saying'', that Lord Alverstone took the very unusual step, at the request of the prosecution, of refusing to give a copy of the sworn affidavit used to issue the arrest warrant to Crippen's defence counsel. The judge without challenge accepted the prosecution's argument that the withholding of the document would not prejudice the accused's case. Yates said he knew why the prosecution did this but – despite the passage of years – refused to disclose why. Yates noted that although Crippen placed the torso in dryquicklime

Calcium oxide (CaO), commonly known as quicklime or burnt lime, is a widely used chemical compound. It is a white, caustic, alkaline, crystalline solid at room temperature. The broadly used term "'' lime''" connotes calcium-containing inorganic m ...

to be destroyed, he did not realise that when it became wet it turned into slaked lime

Calcium hydroxide (traditionally called slaked lime) is an inorganic compound with the chemical formula Ca( OH)2. It is a colorless crystal or white powder and is produced when quicklime (calcium oxide) is mixed or slaked with water. It has m ...

, which is a preservative: a fact that Yates used in the plot of his novel ''The House That Berry Built

''The House That Berry Built'' is a 1945 humorous semi-autobiographical novel by the English author Dornford Yates (Cecil William Mercer), featuring his recurring 'Berry' characters. It is a lightly fictionalised recounting of the construction ...

''.

The American-British crime novelist Raymond Chandler

Raymond Thornton Chandler (July 23, 1888 – March 26, 1959) was an American-British novelist and screenwriter. In 1932, at the age of forty-four, Chandler became a detective fiction writer after losing his job as an oil company executive durin ...

thought it unbelievable that Crippen could be so stupid as to bury his wife's torso under the cellar floor of his home while successfully disposing of her head and limbs.

Another theory is that Crippen was carrying out illegal abortion

Abortion is the termination of a pregnancy by removal or expulsion of an embryo or fetus. An abortion that occurs without intervention is known as a miscarriage or "spontaneous abortion"; these occur in approximately 30% to 40% of pre ...

s and the torso was that of one of his patients who died and not his wife.

New scientific evidence

In October 2007,Michigan State University

Michigan State University (Michigan State, MSU) is a public land-grant research university in East Lansing, Michigan. It was founded in 1855 as the Agricultural College of the State of Michigan, the first of its kind in the United States. It ...

forensic scientist

Forensic science, also known as criminalistics, is the application of science to criminal and civil laws, mainly—on the criminal side—during criminal investigation, as governed by the legal standards of admissible evidence and criminal ...

David Foran claimed that mitochondrial DNA

Mitochondrial DNA (mtDNA or mDNA) is the DNA located in mitochondria, cellular organelles within eukaryotic cells that convert chemical energy from food into a form that cells can use, such as adenosine triphosphate (ATP). Mitochondrial D ...

evidence showed the remains found beneath Crippen's cellar floor were not those of his wife, Cora Crippen. Researchers used genealogy

Genealogy () is the study of families, family history, and the tracing of their lineages. Genealogists use oral interviews, historical records, genetic analysis, and other records to obtain information about a family and to demonstrate kin ...

to identify three living relatives of Cora Crippen (great-nieces). By providing mitochondrial DNA

Mitochondrial DNA (mtDNA or mDNA) is the DNA located in mitochondria, cellular organelles within eukaryotic cells that convert chemical energy from food into a form that cells can use, such as adenosine triphosphate (ATP). Mitochondrial D ...

haplotype

A haplotype ( haploid genotype) is a group of alleles in an organism that are inherited together from a single parent.

Many organisms contain genetic material ( DNA) which is inherited from two parents. Normally these organisms have their DNA o ...

, researchers were able to compare their DNA with DNA extracted from a microscope slide containing flesh taken from the torso in Crippen's cellar. The original remains were also tested using a highly sensitive assay of the Y chromosome

The Y chromosome is one of two sex chromosomes (allosomes) in therian mammals, including humans, and many other animals. The other is the X chromosome. Y is normally the sex-determining chromosome in many species, since it is the presence or abs ...

that found the flesh sample on the slide was male.

The same research team also argued that a scar found on the torso's abdomen, which the original trial's prosecution argued was the same one Mrs. Crippen was known to have, was incorrectly identified. But the scientists found hair follicles in the tissue which should not be present in scars (a medical fact which Crippen's defence used at his trial). Their research was published in the August 2010 issue of the '' Journal of Forensic Sciences''.

However, the new scientific evidence for Crippen's innocence has been disputed.

In ''The Times

''The Times'' is a British daily national newspaper based in London. It began in 1785 under the title ''The Daily Universal Register'', adopting its current name on 1 January 1788. ''The Times'' and its sister paper '' The Sunday Times'' ( ...

'', journalist David Aaronovitch wrote: "As to the body being male, well the American team was using a 'special technique' that is 'very new' and 'done only by this team' and working on a single, century-old slide, described by the team leader as a 'less than optimal sample'". Foran responded by saying "tests showed unequivocally that the remains were male".

Traces of the blonde hair found in curlers at the scene are now preserved in the Metropolitan Police's Crime Museum

The Crime Museum is a collection of criminal memorabilia kept at New Scotland Yard, headquarters of the Metropolitan Police Service in London, England. Known as the Black Museum until the early 21st century, the museum came into existence at S ...

. Another researcher said they asked to be provided with samples from them for DNA testing, but the request has been denied several times. However, New Scotland Yard was willing to test a hair from the crime scene for a fee, which in turn was rejected by the investigators as "over the top." Researchers hypothesized that the police planted the body parts and particularly the fragment of the pyjama top at the scene to incriminate Crippen. He suggests that Scotland Yard was under tremendous public pressure to find and bring to trial a suspect for this heinous crime. An independent observer points out that the case did not become public until after the remains were found.

In December 2009, the UK's Criminal Cases Review Commission

The Criminal Cases Review Commission (CCRC) is the statutory body responsible for investigating alleged miscarriages of justice in England, Wales, and Northern Ireland. It was established by Section 8 of the Criminal Appeal Act 1995 and ...

, having reviewed the case, declared that the Court of Appeal will not hear the case to pardon Crippen posthumously.

Media portrayals

* The murder inspired

* The murder inspired Arthur Machen

Arthur Machen (; 3 March 1863 – 15 December 1947) was the pen-name of Arthur Llewellyn Jones, a Welsh author and mystic of the 1890s and early 20th century. He is best known for his influential supernatural, fantasy, and horror fiction. His ...

's 1927 short story "The Islington Mystery", which in turn was adapted as the 1960 Mexican film '' El Esqueleto de la señora Morales''.

* The gang defeated by Elsa Lanchester

Elsa Sullivan Lanchester (28 October 1902 – 26 December 1986) was a British-American actress with a long career in theatre, film and television.Obituary '' Variety'', 31 December 1986.

Lanchester studied dance as a child and after the F ...

in the H.G. Wells-scripted crime comedy ''Blue Bottles'' (1928) is revealed to be related to the Crippen case.

* It is thought to have inspired the 1935 novel '' We, the Accused'' by Ernest Raymond

Ernest Raymond (31 December 1888 – 14 May 1974) was a British novelist, best known for his first novel, '' Tell England'' (1922), set in World War I. His next biggest success was '' We, the Accused'' (1935), generally thought to be a rewor ...

.

* The German 1942 feature film '' Doctor Crippen'' stars Rudolf Fernau in the title role.

* The story of Dr. Crippen is retold in the act 1 finale of the 1943 Broadway musical ''One Touch of Venus

''One Touch of Venus'' is a 1943 musical with music written by Kurt Weill, lyrics by Ogden Nash, and book by S. J. Perelman and Nash, based on the 1885 novella ''The Tinted Venus'' by Thomas Anstey Guthrie, and very loosely spoofing the Pygmal ...

''.

* A German sequel of ''Dr. Crippen an Bord'' was named ''Dr. Crippen lebt'' (1957).

* The 1961 Wolf Mankowitz

Cyril Wolf Mankowitz (7 November 1924 – 20 May 1998) was an English writer, playwright and screenwriter. He is particularly known for three novels— ''Make Me an Offer'' (1952), '' A Kid for Two Farthings'' (1953) and ''My Old Man's a Dustma ...

musical '' Belle'' at the Strand Theatre in London was based on the case.

* In the 1961 Alfred Hitchcock Presents

''Alfred Hitchcock Presents'' is an American television anthology series created, hosted and produced by Alfred Hitchcock, aired on CBS and NBC between 1955 and 1965. It features dramas, thrillers and mysteries. Between 1962 and 1965 it was r ...

episode '' The Hatbox'', accused wife murderer Professor Jarvis mentions Crippen and Landrau to the detective questioning his wife's disappearance.

* The British 1962 feature film '' Dr. Crippen'' stars Donald Pleasence in the title role and Samantha Eggar as Le Neve.

* In the 20 December 1965 episode of the BBC sitcom ''Meet the Wife'' titled "The Merry Widow", Thora Hird says "Look, If I believed you... Crippen would be innocent."

* The British 1968 film '' Negatives'' features Peter McEnery

Peter Robert McEnery (born 21 February 1940) is a retired English stage and film actor.

Early life

McEnery was born in Walsall, Staffordshire, to Charles and Ada Mary (née Brinson) McEnery. He was educated at Ellesmere College, Shropshire.

Hi ...

and Glenda Jackson as a couple whose erotic fantasies involve dressing up as Crippen and Ethel le Neve.

* The American TV series '' Ironside'' presented an episode (season 2, episode 16, January 23, 1969: "Why the Tuesday Afternoon Bridge Club Met on Thursday") in which a neurotic man assumed Dr. Crippen's identity and committed a similar murder.

* In '' Carry On Loving'', which was made and set in 1970, there is a jokily anachronistic reference to the Crippen case: Peter Butterworth

Peter William Shorrocks Butterworth (4 February 1915''Prisoner of War Co ...

appears in Edwardian costume as 'Dr Crippen', visiting a marriage bureau to seek a third wife, having dispatched both his first two.

* In the 1972 season of Australian TV soap opera

A soap opera, or ''soap'' for short, is a typically long-running radio or television Serial (radio and television), serial, frequently characterized by melodrama, ensemble casts, and sentimentality. The term "soap opera" originated from radio drama ...

, Number 96, a plot line involving the death of Sylvia Vansard (in which her estranged chemist husband and his mistress are the main suspects), deliberately homages the Crippen story. It was referenced in the official synopses provided to the screenwriters.

* In “The Green Door” (1977), s04e02 of the BBC series ''The Good Life (1975 TV series)

''The Good Life'' is a British sitcom, produced by BBC television. It ran from 4 April 1975 to 10 June 1978 on BBC 1 and was written by Bob Larbey and John Esmonde. Opening with the midlife crisis of Tom Good, a 40-year-old plastics design ...

'', the character Tom jokingly references Crippen.

* Kate Bush mentioned Crippen in her 1978 song " Coffee Homeground" about a poisoner – "...pictures of Crippen, lipstick smeared..."

* The 1981 TV series ''Lady Killers'' episode "Miss Elmore" covers the case.

* The Crippen saga is the basis for 1982's ''The False Inspector Dew

''The False Inspector Dew'' is a humorous crime novel by Peter Lovesey. It won the Gold Dagger award by the Crime Writers' Association in 1982 and has featured on many "Best of" lists since.

Plot introduction

It is 1921, and Alma Webster, a read ...

'', a detective novel by Peter Lovesey

Peter (Harmer) Lovesey (born 1936), also known by his pen name Peter Lear, is a British writer of historical and contemporary detective novels and short stories. His best-known series characters are Sergeant Cribb, a Victorian-era police detec ...

.

* The 1989 BBC series ''Shadow of the Noose

''Shadow of the Noose'' is a BBC television legal drama series about the life and career of barrister Sir Edward Marshall Hall. It starred Jonathan Hyde as Marshall Hall; Michael Feast as his clerk, Edgar Bowker; Leslee Udwin as Henriette Mar ...

'', about the life of barrister Edward Marshall Hall

Sir Edward Marshall Hall, (16 September 1858 – 24 February 1927) was an English barrister who had a formidable reputation as an orator. He successfully defended many people accused of notorious murders and became known as "The Great Defender ...

, includes an abortive attempt on Hall's part to defend Crippen (played by David Hatton).

* Crippen is mentioned several times in the BBC series ''Coupling

A coupling is a device used to connect two shafts together at their ends for the purpose of transmitting power. The primary purpose of couplings is to join two pieces of rotating equipment while permitting some degree of misalignment or end mov ...

'', series 1, episode 1, titled “Flushed”, as a running gag and an ongoing argument between Jane and Steve about continuing their relationship.

* John Boyne

John Boyne (born 30 April 1971) is an Irish novelist. He is the author of eleven novels for adults and six novels for younger readers. His novels are published in over 50 languages. His 2006 novel '' The Boy in the Striped Pyjamas'' was adap ...

wrote the 2004 novel ''Crippen – A Novel of Murder''.

* Erik Larson's 2006 book ''Thunderstruck'' interwove the story of the murder with the history of Guglielmo Marconi

Guglielmo Giovanni Maria Marconi, 1st Marquis of Marconi (; 25 April 187420 July 1937) was an Italian inventor and electrical engineer, known for his creation of a practical radio wave-based wireless telegraph system. This led to Marconi ...

's invention of radio.

* In the BBC Radio 4 series Old Harry's Game ''Old Harry's Game

''Old Harry's Game'' is a UK radio comedy written and directed by Andy Hamilton, who also plays the cynical, world-weary Satan. "Old Harry" is one of many names for the devil. The show's title is a humorous play on the title of the 1982 TV ser ...

'', series 6, episode 3 (2008), Satan mentions Dr Crippen in hell.

* Martin Edwards

Charles Martin Edwards (born 24 July 1945) is the former chairman of Manchester United, a position he held from 1980 until 2002. He now holds the position of honorary life president at the club and Director of Inview Technology Ltd.

Biography

...

wrote the 2008 novel ''Dancing for the Hangman'', which re-interprets the case while seeking to adhere to the established evidence.

* The PBS series '' Secrets of the Dead'' episode "Executed in Error" (2008) explored new findings in the Crippen case.

* In series 1, episode 5 of the British comedy series '' Psychoville'' (2009), Reece Shearsmith plays a waxwork figure that comes to life in a dream. Jack the Ripper

Jack the Ripper was an unidentified serial killer active in and around the impoverished Whitechapel district of London, England, in the autumn of 1888. In both criminal case files and the contemporaneous journalistic accounts, the killer w ...

mistakes him for Crippen, but he is portraying John Reginald Christie.

* The third installment in the TV series '' Murder Maps'' is "Finding Dr. Crippen" (2015).

* Dan Weatherer's stage play ''Crippen'' (2016) explores the life and crimes of Dr. Hawley Crippen while taking into account new evidence and presenting an alternative theory as to who lay buried beneath the cellar floor.

* The cat attached to the Peculiar Crimes Unit in Christopher Fowler’s novels is named “Crippen”.

See also

* John Reginald Christie, English serial killer *John George Haigh

John George Haigh (; 24 July 1909 – 10 August 1949), commonly known as the Acid Bath Murderer, was an English serial killer convicted for the murder of six people, although he claimed to have killed nine. Haigh battered to death or shot his ...

, English serial killer known as the "Acid Bath Murderer"

*Michael Swango

Michael Joseph Swango (born October 21, 1954) is an American serial killer and licensed physician who is estimated to have been involved in as many as 60 fatal poisonings of patients and colleagues, although he admitted to only causing four dea ...

, American serial killer

* John Tawell, British murderer and the first criminal to be captured with the use of telecommunications technology

* Dorothea Waddingham, English nursing home matron and murderer

References

Further reading

* * * * * * * * * * * *Finn, Pat (2016) ''Unsolved 1910''.External links

* * * * * * * {{DEFAULTSORT:Crippen, Hawley Harvey 1862 births 1910 deaths 20th-century executions by England and Wales 20th-century executions of American people American expatriates in the United Kingdom American homeopaths American people convicted of murder American people executed abroad Executed people from Michigan Male murderers People convicted of murder by England and Wales People from Coldwater, Michigan 1910 murders in the United Kingdom University of Michigan alumni 1910s murders in London Uxoricides 1910 in London