Double Seven Day scuffle on:

[Wikipedia]

[Google]

[Amazon]

The Double Seven Day Scuffle was a physical altercation on July 7, 1963, in Saigon, South Vietnam. The secret police of

The incident occurred during a period of popular unrest by the Buddhist majority against the

The incident occurred during a period of popular unrest by the Buddhist majority against the

Diem's address on Double Seven Day worsened the mood of Vietnamese society. He stated that the "problems raised by the General Association of Buddhists have just been settled." He reinforced perceptions that he was out of touch by attributing any lingering problems to the "underground intervention of international red agents and Communist fellow travelers who in collusion with fascist ideologues disguised as democrats were surreptitiously seeking to revive and rekindle disunity at home while arousing public opinions against us abroad". The remark about fascists was seen as a reference to the conspiratorial Dai Viet Quoc Dan Dang who had long been enemies of Diem, but his address attacked all those who had criticised him in the past. He no longer trusted anyone outside his family and considered himself to be a martyr.Hammer, pp. 157–158.

Diem's address on Double Seven Day worsened the mood of Vietnamese society. He stated that the "problems raised by the General Association of Buddhists have just been settled." He reinforced perceptions that he was out of touch by attributing any lingering problems to the "underground intervention of international red agents and Communist fellow travelers who in collusion with fascist ideologues disguised as democrats were surreptitiously seeking to revive and rekindle disunity at home while arousing public opinions against us abroad". The remark about fascists was seen as a reference to the conspiratorial Dai Viet Quoc Dan Dang who had long been enemies of Diem, but his address attacked all those who had criticised him in the past. He no longer trusted anyone outside his family and considered himself to be a martyr.Hammer, pp. 157–158.

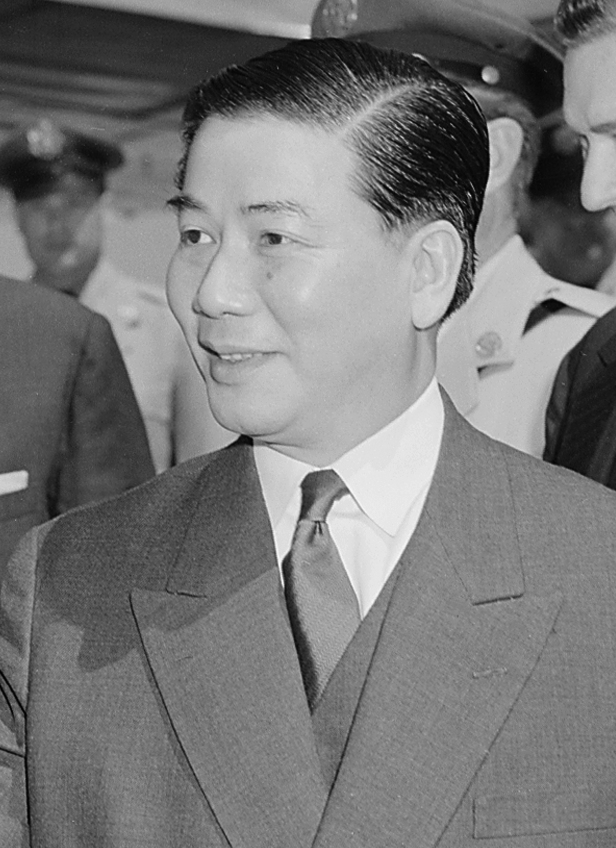

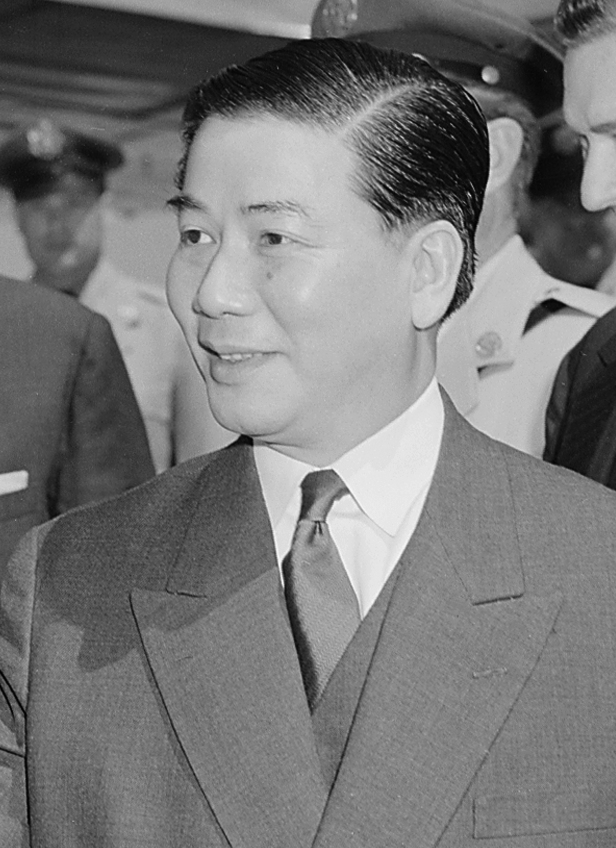

Ngô Đình Nhu

Ngô Đình Nhu (; 7 October 19102 November 1963; baptismal name Jacob) was a Vietnamese archivist and politician. He was the younger brother and chief political advisor of South Vietnam's first president, Ngô Đình Diệm. Although he held n ...

—the brother of President

President most commonly refers to:

*President (corporate title)

* President (education), a leader of a college or university

* President (government title)

President may also refer to:

Automobiles

* Nissan President, a 1966–2010 Japanese ...

Ngô Đình Diệm—attacked a group of US journalists who were covering protests held by Buddhists on the ninth anniversary of Diệm's rise to power. Peter Arnett

Peter Gregg Arnett (born 13 November 1934) is a New Zealand-born American journalist. He is known for his coverage of the Vietnam War and the Gulf War. He was awarded the 1966 Pulitzer Prize in International Reporting for his work in Vietn ...

of the Associated Press

The Associated Press (AP) is an American non-profit news agency headquartered in New York City. Founded in 1846, it operates as a cooperative, unincorporated association. It produces news reports that are distributed to its members, U.S. ne ...

(AP) was punched on the nose, and the quarrel quickly ended after David Halberstam

David Halberstam (April 10, 1934 April 23, 2007) was an American writer, journalist, and historian, known for his work on the Vietnam War, politics, history, the Civil Rights Movement, business, media, American culture, Korean War, and late ...

of ''The New York Times

''The New York Times'' (''the Times'', ''NYT'', or the Gray Lady) is a daily newspaper based in New York City with a worldwide readership reported in 2020 to comprise a declining 840,000 paid print subscribers, and a growing 6 million paid d ...

'', being much taller than Nhu's men, counterattacked and caused the secret police to retreat. Arnett and his colleague, the Pulitzer Prize-winning journalist and photographer Malcolm Browne

Malcolm Wilde Browne (April 17, 1931August 27, 2012) was an American journalist and photographer, best known for his award-winning photograph of the self-immolation of Buddhist monk Thích Quảng Đức in 1963.

Early life and education

Brown ...

, were later accosted by policemen at their office and taken away for questioning on suspicion of attacking policemen.

After their release, the journalists went to the US embassy in Saigon to complain about their treatment at the hands of Diệm's officials and asked for US government protection. Their appeals were dismissed, as was a direct appeal to the White House

The White House is the official residence and workplace of the president of the United States. It is located at 1600 Pennsylvania Avenue NW in Washington, D.C., and has been the residence of every U.S. president since John Adams in ...

. Through the efforts of US Ambassador

Ambassadors of the United States are persons nominated by the president to serve as the country's diplomatic representatives to foreign nations, international organizations, and as ambassadors-at-large. Under Article II, Section 2 of the U.S ...

Frederick Nolting, the assault charges laid against the journalists were subsequently dropped. Vietnamese Buddhists reacted to the incident by contending that Diệm's men were planning to assassinate monks, while Madame Nhu

Trần Lệ Xuân (22 August 1924 – 24 April 2011), more popularly known in English as Madame Nhu, was the ''de facto'' First Lady of South Vietnam from 1955 to 1963. She was the wife of Ngô Đình Nhu, who was the brother and chief advisor ...

repeated earlier claims that the US government had been trying to overthrow her brother-in-law. Browne took photographs of Arnett's bloodied face, which were published in newspapers worldwide. This drew further negative attention to the behaviour of the Diệm régime amidst the backdrop of the Buddhist crisis

The Buddhist crisis ( vi, Biến cố Phật giáo) was a period of political and religious tension in South Vietnam between May and November 1963, characterized by a series of repressive acts by the South Vietnamese government and a campaign o ...

.

Background

The incident occurred during a period of popular unrest by the Buddhist majority against the

The incident occurred during a period of popular unrest by the Buddhist majority against the Catholic

The Catholic Church, also known as the Roman Catholic Church, is the largest Christian church, with 1.3 billion baptized Catholics worldwide . It is among the world's oldest and largest international institutions, and has played a ...

rule of Diệm. Buddhist discontent had grown since the Huế Phật Đản shootings on May 8, 1963.Jones, p. 247. The government decided to selectively invoke a law, prohibiting the display of religious flags, by banning the use of the Buddhist flag

The Buddhist flag is a flag designed in the late 19th century as a universal symbol of Buddhism. It is used by Buddhists throughout the world.

History

The flag was originally designed in 1885 by the Colombo Committee, in Colombo, Ceylon (''no ...

on Vesak

Vesak (Pali: ''Vesākha''; sa, Vaiśākha), also known as Buddha Jayanti, Buddha Purnima and Buddha Day, is a holiday traditionally observed by Buddhists in South Asia and Southeast Asia as well as Tibet and Mongolia. The festival commemora ...

, the birthday of Gautama Buddha

Siddhartha Gautama, most commonly referred to as the Buddha, was a wandering ascetic and religious teacher who lived in South Asia during the 6th or 5th century BCE and founded Buddhism.

According to Buddhist tradition, he was born in Lu ...

. One week earlier, the Vatican

Vatican may refer to:

Vatican City, the city-state ruled by the pope in Rome, including St. Peter's Basilica, Sistine Chapel, Vatican Museum

The Holy See

* The Holy See, the governing body of the Catholic Church and sovereign entity recognized ...

flag had been flown at a celebration for Archbishop Ngô Đình Thục

Pierre Martin Ngô Đình Thục () (6 October 1897 – 13 December 1984) was the Roman Catholic Archbishop of Huế, Vietnam, and later a sedevacantist bishop who was excommunicated by the Vatican and allegedly reconciled with the Vatican b ...

, Diệm's brother. The Buddhists defied the ban, flying their flags on Vesak and holding a demonstration, which was ended with government gunfire and eight or nine deaths. The killings sparked nationwide protests by South Vietnam's Buddhist majority against the policies of Diệm's regime. The Buddhists demanded that Diệm give them religious equality, but with their demands unfulfilled, the protests increased in magnitude. The most notable of these was the self-immolation of Thích Quảng Đức

Thích Quảng Đức (; vi-hantu, , 1897 – 11 June 1963; born Lâm Văn Túc) was a Vietnamese Mahayana Buddhist monk who burned himself to death at a busy Saigon road intersection on 11 June 1963. Quảng Đức was protesting the pers ...

on June 11, which was iconically photographed by the media and became a negative symbol of the Diệm régime.

Known as Double Seven Day, July 7 was the ninth anniversary of Diệm's 1954 ascension to Prime Minister of the State of Vietnam. In October 1955, following a fraudulent referendum, Diệm established the Republic of Vietnam, generally known as South Vietnam, and declared himself President

President most commonly refers to:

*President (corporate title)

* President (education), a leader of a college or university

* President (government title)

President may also refer to:

Automobiles

* Nissan President, a 1966–2010 Japanese ...

. The night of July 6, 1963, had started in a festive mood as Diệm awarded decorations to military officers at a ceremony. Among those in the audience were Generals Trần Văn Đôn

Trần Văn Đôn (August 17, 1917 – 1997) was a general in the Army of the Republic of Vietnam, and one of the principal figures in the 1963 South Vietnamese coup d'état which overthrew President Ngô Đình Diệm.

Personal life

Đôn w ...

and Dương Văn Minh

Dương Văn Minh (; 16 February 19166 August 2001), popularly known as Big Minh, was a South Vietnamese politician and a senior general in the Army of the Republic of Vietnam (ARVN) and a politician during the presidency of Ngô Đình Diệm ...

, the Chief of Staff of the Army of the Republic of Vietnam and the Presidential Military Advisor, respectively. They had returned from observing SEATO

The Southeast Asia Treaty Organization (SEATO) was an international organization for collective defense in Southeast Asia created by the Southeast Asia Collective Defense Treaty, or Manila Pact, signed in September 1954 in Manila, the Philipp ...

military exercises in Thailand

Thailand ( ), historically known as Siam () and officially the Kingdom of Thailand, is a country in Southeast Asia, located at the centre of the Indochinese Peninsula, spanning , with a population of almost 70 million. The country is b ...

,Jones, p. 286. where they had been informed about the regional disquiet over Diem's policies towards the Buddhists.

Incident

American pressmen had been alerted to an upcoming Buddhist demonstration to coincide with Double Seven Day at Chanatareansey Pagoda in the north of Saigon. The nine-man group, which included Arnett, Browne, AP photographerHorst Faas

Horst Faas (28 April 1933 – 10 May 2012) was a German photo-journalist and two-time Pulitzer Prize winner. He is best known for his images of the Vietnam War.

Life

Horst Faas as born on 28 April 1933 in Berlin, which was then part of Naz ...

, David Halberstam

David Halberstam (April 10, 1934 April 23, 2007) was an American writer, journalist, and historian, known for his work on the Vietnam War, politics, history, the Civil Rights Movement, business, media, American culture, Korean War, and late ...

, Neil Sheehan

Cornelius Mahoney Sheehan (October 27, 1936 – January 7, 2021) was an American journalist. As a reporter for ''The New York Times'' in 1971, Sheehan obtained the classified '' Pentagon Papers'' from Daniel Ellsberg. His series of articles rev ...

of ''United Press International

United Press International (UPI) is an American international news agency whose newswires, photo, news film, and audio services provided news material to thousands of newspapers, magazines, radio and television stations for most of the 20t ...

'', and CBS

CBS Broadcasting Inc., commonly shortened to CBS, the abbreviation of its former legal name Columbia Broadcasting System, is an American commercial broadcast television and radio network serving as the flagship property of the CBS Entertainm ...

's Peter Kalischer and photographer Joseph Masraf waited outside the building with their equipment. After an hour-long religious ceremony, the Buddhist monks, numbering around 300, filed out of the pagoda

A pagoda is an Asian tiered tower with multiple eaves common to Nepal, India, China, Japan, Korea, Myanmar, Vietnam, and other parts of Asia. Most pagodas were built to have a religious function, most often Buddhist but sometimes Taoist, ...

into a narrow alley along a side street, where they were blocked and ordered to stop by plain-clothed policemen. The Buddhists did not resist, but Arnett and Browne began taking photos of the confrontation. The police, who were loyal to Ngo Dinh Nhu

A non-governmental organization (NGO) or non-governmental organisation (see spelling differences) is an organization that generally is formed independent from government. They are typically nonprofit entities, and many of them are active in h ...

,Langguth, p. 219. thereupon punched Arnett in the nose, knocked him to the ground, kicked him with their pointed-toe shoes, and broke his camera.Prochnau, p. 328. Halberstam, who won a Pulitzer Prize for his coverage of the Buddhist crisis, was a tall man, standing around taller than the average Vietnamese policeman. He waded into the fracas swinging his arms, reportedly saying "Get back, get back, you sons of bitches, or I'll beat the shit out of you!" Nhu's men ran away without waiting for a Vietnamese

Vietnamese may refer to:

* Something of, from, or related to Vietnam, a country in Southeast Asia

** A citizen of Vietnam. See Demographics of Vietnam.

* Vietnamese people, or Kinh people, a Southeast Asian ethnic group native to Vietnam

** Overse ...

translation, but not before Browne had clambered up a power pole and taken photos of Arnett's bloodied face. The police smashed Browne's camera, but his photographic film survived the impact. The other journalists were jostled and rocks were thrown at them. Photos of Arnett's bloodied face were circulated in US newspapers and caused further ill-feeling towards Diem's regime, with the images of the burning Thich Quang Duc on the front pages still fresh in the minds of the public.Hammer, p. 157.Jones, p. 285. Halberstam's report estimated that the altercation lasted for around ten minutes and also admitted that the pressmen had tried to apprehend the policeman who had smashed Browne's camera but were shielded by the rock-wielding policeman's colleagues. He also claimed that the secret policemen had also tried to seize equipment from Masraf and Faas.

Diem's address on Double Seven Day worsened the mood of Vietnamese society. He stated that the "problems raised by the General Association of Buddhists have just been settled." He reinforced perceptions that he was out of touch by attributing any lingering problems to the "underground intervention of international red agents and Communist fellow travelers who in collusion with fascist ideologues disguised as democrats were surreptitiously seeking to revive and rekindle disunity at home while arousing public opinions against us abroad". The remark about fascists was seen as a reference to the conspiratorial Dai Viet Quoc Dan Dang who had long been enemies of Diem, but his address attacked all those who had criticised him in the past. He no longer trusted anyone outside his family and considered himself to be a martyr.Hammer, pp. 157–158.

Diem's address on Double Seven Day worsened the mood of Vietnamese society. He stated that the "problems raised by the General Association of Buddhists have just been settled." He reinforced perceptions that he was out of touch by attributing any lingering problems to the "underground intervention of international red agents and Communist fellow travelers who in collusion with fascist ideologues disguised as democrats were surreptitiously seeking to revive and rekindle disunity at home while arousing public opinions against us abroad". The remark about fascists was seen as a reference to the conspiratorial Dai Viet Quoc Dan Dang who had long been enemies of Diem, but his address attacked all those who had criticised him in the past. He no longer trusted anyone outside his family and considered himself to be a martyr.Hammer, pp. 157–158.

Reaction

The indignant reporters stridently accused the Diem regime of causing the altercation, whereas the police claimed that the journalists threw the first punch. Embassy official John Mecklin noted that even Diem's media officials were privately skeptical about the veracity of the testimony of Nhu's men. In a heated meeting at the embassy, the press corps demanded that William Trueheart, the acting US Ambassador to South Vietnam in the absence of the vacationing Frederick Nolting, deliver a formal protest to Diem on behalf of the American government. Trueheart angered them by refusing to do so and blaming both sides for the confrontation. He said that he did not believe a formal protest was possible given that it could not be proven that the violence was pre-meditated but claimed to believe the journalists' version of events. He also noted that Vietnamese officials had claimed that incident was simply a matter of "a few people lost their heads". In his report toWashington

Washington commonly refers to:

* Washington (state), United States

* Washington, D.C., the capital of the United States

** A metonym for the federal government of the United States

** Washington metropolitan area, the metropolitan area centered o ...

, Trueheart asserted that the uniformed policemen had tacitly helped their plainclothed counterparts, but he also had "no doubt that hereporters, at least once hefracas had started, acted in belligerent manner towards hepolice". Trueheart contended that since the journalists had a long history of bad blood with the Diem regime, their word could not be taken over that of the Vietnamese police.

Later on the same day, the US State Department

The United States Department of State (DOS), or State Department, is an executive department of the U.S. federal government responsible for the country's foreign policy and relations. Equivalent to the ministry of foreign affairs of other nati ...

released a statement in Washington DC, announcing that the Saigon Embassy had informally complained to and asked Diem's regime for an explanation regarding the incident, and said that officials were studying various accounts of the incident and that it was American policy to look out for the interests of their citizens regardless of their background or occupation.

Since the embassy was unwilling to provide government protection against police aggression, the journalists appealed directly to the White House. Browne, Halberstam, Sheehan and Kalischer wrote a letter to US President John F. Kennedy

John Fitzgerald Kennedy (May 29, 1917 – November 22, 1963), often referred to by his initials JFK and the nickname Jack, was an American politician who served as the 35th president of the United States from 1961 until his assassination ...

, asserting that the regime had begun a full-scale campaign of "open physical intimidation to prevent the covering of news which we feel Americans have a right to know", which was noted by the press secretary Pierre Salinger

Pierre Emil George Salinger (June 14, 1925 – October 16, 2004) was an American journalist, author and politician. He served as the ninth press secretary for United States Presidents John F. Kennedy and Lyndon B. Johnson. Salinger served ...

.

The protests did not garner any Presidential sympathy for the journalists, but instead resulted in trouble from their media employers. UPI's Tokyo office criticised Sheehan for trying to "make Unipress policy" on his own when "Unipress must be neutral, neither pro-Diem, pro-Communist or pro-anybody else". Emanuel Freedman, the foreign editor of ''The New York Times

''The New York Times'' (''the Times'', ''NYT'', or the Gray Lady) is a daily newspaper based in New York City with a worldwide readership reported in 2020 to comprise a declining 840,000 paid print subscribers, and a growing 6 million paid d ...

'' reprimanded Halberstam, writing "We still feel that our correspondents should not be firing off cables to the President of the United States without authorization."

The incident provoked reactions from both the Buddhists and the Diem regime. A monk called on the US embassy to send a military unit from the American advisors already present in Vietnam to Xá Lợi Pagoda, the main Buddhist temple in Saigon and the organisational hub of the Buddhist movement. The monk claimed that the attack on Arnett indicated that Xá Lợi's monks were targets of assassination by Nhu's men, something that Trueheart rejected, turning down the protection request. Xá Lợi and other Buddhist centers across the country were raided a month later by Special Forces under the direct control of the Ngo family. On the part of the South Vietnamese government, the ''de facto'' first lady Madame Nhu

Trần Lệ Xuân (22 August 1924 – 24 April 2011), more popularly known in English as Madame Nhu, was the ''de facto'' First Lady of South Vietnam from 1955 to 1963. She was the wife of Ngô Đình Nhu, who was the brother and chief advisor ...

used her English-language mouthpiece newspaper, the ''Times of Vietnam

The ''Times of Vietnam'' is a defunct English language newspaper that existed in South Vietnam under the rule of President Ngô Đình Diệm.

Regarded as the official mouthpiece of the Diệm regime, the ''Times'' was disbanded following the 1 ...

'', to accuse the United States of supporting the failed coup attempt against Diem in 1960.

Arrest and interrogation

Later on during the day of the altercation, the police collected Browne and Arnett from the APbureau

Bureau ( ) may refer to:

Agencies and organizations

* Government agency

*Public administration

* News bureau, an office for gathering or distributing news, generally for a given geographical location

* Bureau (European Parliament), the administra ...

in Saigon and took the pair to what they described as a "safe house

A safe house (also spelled safehouse) is, in a generic sense, a secret place for sanctuary or suitable to hide people from the law, hostile actors or actions, or from retribution, threats or perceived danger. It may also be a metaphor.

Histori ...

". The police interrogators said that they would be arrested but were unspecific about the charges. One charge was that of assaulting two police officers, but the interrogators hinted that more serious offences such as organising illegal demonstrations were being considered. The officers conversed among themselves in French, a language which the reporters did not speak, but Arnett thought that they mentioned the word ''espionage

Espionage, spying, or intelligence gathering is the act of obtaining secret or confidential information (intelligence) from non-disclosed sources or divulging of the same without the permission of the holder of the information for a tangib ...

''. After four hours of questioning, the pair were charged with assault. Browne and Arnett in turn filed charges against the police over the altercation, and demanded compensation for the damage to their photographic equipment. Arnett and Browne were temporarily released in the evening, after which the whole Saigon press corps stormed the US embassy.Prochnau, p. 329.

Browne and Arnett were called in for five hours of questioning on the following day. Arnett was accompanied by a British embassy official who, reflecting Arnett's New Zealand citizenship, provided consular assistance on behalf of Wellington

Wellington ( mi, Te Whanganui-a-Tara or ) is the capital city of New Zealand. It is located at the south-western tip of the North Island, between Cook Strait and the Remutaka Range. Wellington is the second-largest city in New Zealand by metr ...

.Prochnau, p. 330. In the end, Diem agreed to have the charges against Browne and Arnett dropped after hours of heated argument with US Ambassador Frederick Nolting, who had returned from his vacation.

Notes

References

* * * * * {{DEFAULTSORT:Double Seven Day Scuffle Conflicts in 1963 Buddhist crisis History of South Vietnam 1963 in Vietnam Persecution of Buddhists