Donald Mackenzie Wallace on:

[Wikipedia]

[Google]

[Amazon]

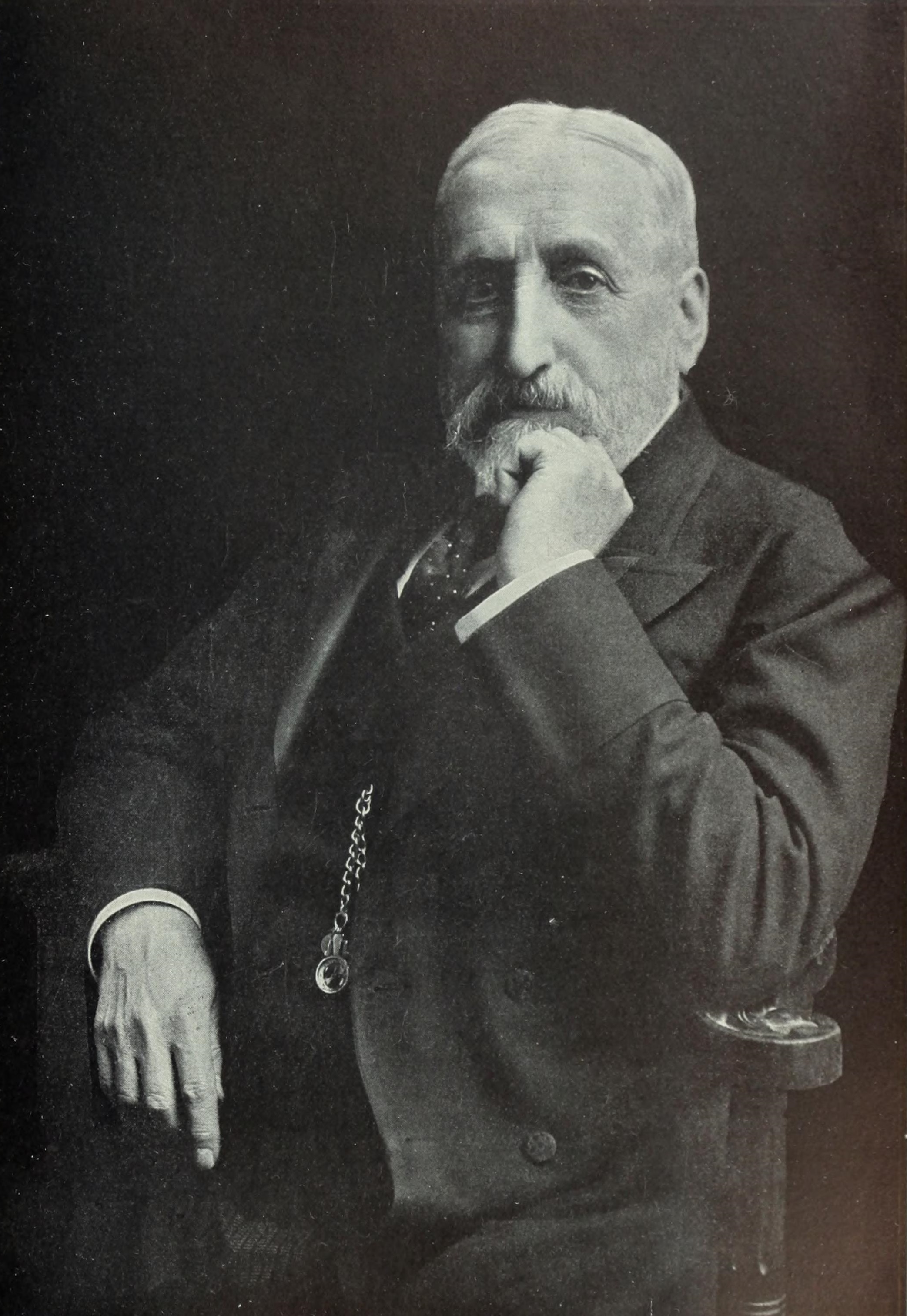

Sir Donald Mackenzie Wallace (11 November 1841 – 10 January 1919) was a Scottish public servant, writer, editor and foreign correspondent of ''

Sir Donald Mackenzie Wallace (11 November 1841 – 10 January 1919) was a Scottish public servant, writer, editor and foreign correspondent of ''

accessed 28 Oct 2007

"Our Russian Ally" by Wallace.

{{DEFAULTSORT:Wallace, Donald Mackenzie 1841 births 1919 deaths Encyclopædia Britannica Writers about Russia Knights Commander of the Royal Victorian Order Knights Commander of the Order of the Indian Empire British encyclopedists Scottish writers Alumni of the University of Edinburgh

Sir Donald Mackenzie Wallace (11 November 1841 – 10 January 1919) was a Scottish public servant, writer, editor and foreign correspondent of ''

Sir Donald Mackenzie Wallace (11 November 1841 – 10 January 1919) was a Scottish public servant, writer, editor and foreign correspondent of ''The Times

''The Times'' is a British daily national newspaper based in London. It began in 1785 under the title ''The Daily Universal Register'', adopting its current name on 1 January 1788. ''The Times'' and its sister paper '' The Sunday Times'' ( ...

'' (London).

Early life

Donald Mackenzie Wallace was born to Robert Wallace ofBoghead

Boghead is a small village in South Lanarkshire, west central Scotland. It is about southeast of Glasgow and sits nearby to the River Nethan and Avon Water. Boghead is a residential area, with working residents commuting to nearby villages and ...

, Dunbartonshire

Dunbartonshire ( gd, Siorrachd Dhùn Breatann) or the County of Dumbarton is a historic county, lieutenancy area and registration county in the west central Lowlands of Scotland lying to the north of the River Clyde. Dunbartonshire borders Pe ...

, and Sarah Mackenzie. Both his parents died before Donald turned ten. By the age of fifteen, Wallace immersed himself in his studies. He spent all his time before the age of twenty-eight in continuous study at various universities such as Edinburgh

Edinburgh ( ; gd, Dùn Èideann ) is the capital city of Scotland and one of its 32 Council areas of Scotland, council areas. Historically part of the county of Midlothian (interchangeably Edinburghshire before 1921), it is located in Lothian ...

and Glasgow

Glasgow ( ; sco, Glesca or ; gd, Glaschu ) is the most populous city in Scotland and the fourth-most populous city in the United Kingdom, as well as being the 27th largest city by population in Europe. In 2020, it had an estimated popu ...

, focusing his study on metaphysics and ethics. He spent the remaining years at the École de Droit, Paris, and applied himself to Roman law at the universities of Berlin

Berlin ( , ) is the capital and largest city of Germany by both area and population. Its 3.7 million inhabitants make it the European Union's most populous city, according to population within city limits. One of Germany's sixteen constitu ...

and Heidelberg

Heidelberg (; Palatine German: ') is a city in the German state of Baden-Württemberg, situated on the river Neckar in south-west Germany. As of the 2016 census, its population was 159,914, of which roughly a quarter consisted of students ...

, graduating with a doctorate in law from Heidelberg in 1867.

Travels to Russia

Wallace accepted a private invitation to visitRussia

Russia (, , ), or the Russian Federation, is a transcontinental country spanning Eastern Europe and Northern Asia. It is the largest country in the world, with its internationally recognised territory covering , and encompassing one-ei ...

, having a strong desire to study the Ossetes, a tribe of Iranian

Iranian may refer to:

* Iran, a sovereign state

* Iranian peoples, the speakers of the Iranian languages. The term Iranic peoples is also used for this term to distinguish the pan ethnic term from Iranian, used for the people of Iran

* Iranian lan ...

descent in the Caucasus

The Caucasus () or Caucasia (), is a region between the Black Sea and the Caspian Sea, mainly comprising Armenia, Azerbaijan, Georgia, and parts of Southern Russia. The Caucasus Mountains, including the Greater Caucasus range, have historica ...

. Living in Russia from early 1870 until late 1875, Wallace found the Russian civilization far more interesting than his original Ossetes. Wallace returned to the United Kingdom in 1876 and published three volumes in his work Russia by 1877, right before the outbreak of the Russo-Turkish War

The Russo-Turkish wars (or Ottoman–Russian wars) were a series of twelve wars fought between the Russian Empire and the Ottoman Empire between the 16th and 20th centuries. It was one of the longest series of military conflicts in European histo ...

. His book had great success, going through several editions and being translated into many languages.

Foreign correspondent

Due to the success of his work in Russia, Wallace was appointed as foreign correspondent of ''The Times''. His first post was St. Petersburg in 1877-78; he was then sent to theCongress of Berlin

The Congress of Berlin (13 June – 13 July 1878) was a diplomatic conference to reorganise the states in the Balkan Peninsula after the Russo-Turkish War of 1877–78, which had been won by Russia against the Ottoman Empire. Represented at th ...

in June and July 1878. There he assisted Henri de Blowitz, the famous Paris correspondent of ''The Times'', and carried the text of the treaty from Berlin to Brussels sewn into the lining of his greatcoat. From 1878-1883 he was in Constantinople; while there, he investigated the Balkan

The Balkans ( ), also known as the Balkan Peninsula, is a geographical area in southeastern Europe with various geographical and historical definitions. The region takes its name from the Balkan Mountains that stretch throughout the who ...

peoples and their problems and ended up going on a special mission to Egypt

Egypt ( ar, مصر , ), officially the Arab Republic of Egypt, is a List of transcontinental countries, transcontinental country spanning the North Africa, northeast corner of Africa and Western Asia, southwest corner of Asia via a land bridg ...

. The outcome of Wallace's mission to Egypt became another successful book, ''Egypt and the Egyptian Question'' (1884). After traveling through the Middle East, Wallace was selected as the political officer of the future Tsar Nicholas II

Nicholas II or Nikolai II Alexandrovich Romanov; spelled in pre-revolutionary script. ( 186817 July 1918), known in the Russian Orthodox Church as Saint Nicholas the Passion-Bearer,. was the last Emperor of Russia, King of Congress Pol ...

in his Indian tour of 1890-91, for which he later received 1st class Russian Order of St. Stanislas. He served as Private Secretary to Lords Dufferin and Lansdowne, in India.

Later life

In his last years Wallace reverted to his youthful self and devoted himself to study again. He didn't publish anything after his last book, ''The Web of Empire'', in 1902. He contributed briefly to the editing of the 10th edition of theEncyclopædia Britannica

The (Latin for "British Encyclopædia") is a general knowledge English-language encyclopaedia. It is published by Encyclopædia Britannica, Inc.; the company has existed since the 18th century, although it has changed ownership various t ...

, but in March 1901 he was taken from his ''Britannica'' duties by the Duke of Cornwall and York, (the future King George V

George V (George Frederick Ernest Albert; 3 June 1865 – 20 January 1936) was King of the United Kingdom and the British Dominions, and Emperor of India, from 6 May 1910 until his death in 1936.

Born during the reign of his grandmother Qu ...

), who asked Wallace to act as his Private secretary during an extensive world tour. During seven months from March to October 1901 the royal party visited Gibraltar

)

, anthem = " God Save the King"

, song = "Gibraltar Anthem"

, image_map = Gibraltar location in Europe.svg

, map_alt = Location of Gibraltar in Europe

, map_caption = United Kingdom shown in pale green

, mapsize =

, image_map2 = Gibr ...

, Malta

Malta ( , , ), officially the Republic of Malta ( mt, Repubblika ta' Malta ), is an island country in the Mediterranean Sea. It consists of an archipelago, between Italy and Libya, and is often considered a part of Southern Europe. It lies ...

, Aden

Aden ( ar, عدن ' Yemeni: ) is a city, and since 2015, the temporary capital of Yemen, near the eastern approach to the Red Sea (the Gulf of Aden), some east of the strait Bab-el-Mandeb. Its population is approximately 800,000 peopl ...

, Ceylon

Sri Lanka (, ; si, ශ්රී ලංකා, Śrī Laṅkā, translit-std=ISO (); ta, இலங்கை, Ilaṅkai, translit-std=ISO ()), formerly known as Ceylon and officially the Democratic Socialist Republic of Sri Lanka, is an ...

, Australia

Australia, officially the Commonwealth of Australia, is a sovereign country comprising the mainland of the Australian continent, the island of Tasmania, and numerous smaller islands. With an area of , Australia is the largest country by ...

, New Zealand

New Zealand ( mi, Aotearoa ) is an island country in the southwestern Pacific Ocean. It consists of two main landmasses—the North Island () and the South Island ()—and over 700 smaller islands. It is the sixth-largest island coun ...

, Straits Settlements

The Straits Settlements were a group of British territories located in Southeast Asia. Headquartered in Singapore for more than a century, it was originally established in 1826 as part of the territories controlled by the British East India Com ...

, Natal and Cape Colony

The Cape Colony ( nl, Kaapkolonie), also known as the Cape of Good Hope, was a British colony in present-day South Africa named after the Cape of Good Hope, which existed from 1795 to 1802, and again from 1806 to 1910, when it united with ...

, and Canada

Canada is a country in North America. Its ten provinces and three territories extend from the Atlantic Ocean to the Pacific Ocean and northward into the Arctic Ocean, covering over , making it the world's second-largest country by to ...

.

Wallace was later attached to Emperor of Russia during his visit to England, 1909, then was Extra Groom-in-Waiting to Emperor Edward VII, 1909–10, and to Emperor George V from 1910.

He was knighted as a Knight Commander of the Order of the Indian Empire

The Most Eminent Order of the Indian Empire is an order of chivalry founded by Queen Victoria on 1 January 1878. The Order includes members of three classes:

#Knight Grand Commander (GCIE)

#Knight Commander ( KCIE)

#Companion ( CIE)

No appoi ...

(KCIE) for his services to India in 1888, and subsequently appointed a Knight Commander of the Royal Victorian Order

The Royal Victorian Order (french: Ordre royal de Victoria) is a dynastic order of knighthood established in 1896 by Queen Victoria. It recognises distinguished personal service to the British monarch, Canadian monarch, Australian monarch, o ...

(KCVO) for his services during the Commonwealth tour in 1901.

He never married and died at Lymington

Lymington is a port town on the west bank of the Lymington River on the Solent, in the New Forest district of Hampshire, England. It faces Yarmouth, Isle of Wight, to which there is a car ferry service operated by Wightlink. It is within the ...

, Hampshire

Hampshire (, ; abbreviated to Hants) is a ceremonial and non-metropolitan county in western South East England on the coast of the English Channel. Home to two major English cities on its south coast, Southampton and Portsmouth, Hampshire ...

, on 10 January 1919.

Books

* ''Russia'', 2 vols. (London: Cassell, 1877) * ''Egypt and the Egyptian Question'' (1883) * ''The Web of Empire'' (1902)References

Sources

*G. E. Buckle, ‘Wallace, Sir Donald Mackenzie (1841–1919)’, rev. H. C. G. Matthew, ''Oxford Dictionary of National Biography'', Oxford University Press, 200accessed 28 Oct 2007

External links

* *"Our Russian Ally" by Wallace.

{{DEFAULTSORT:Wallace, Donald Mackenzie 1841 births 1919 deaths Encyclopædia Britannica Writers about Russia Knights Commander of the Royal Victorian Order Knights Commander of the Order of the Indian Empire British encyclopedists Scottish writers Alumni of the University of Edinburgh