Don Dunstan on:

[Wikipedia]

[Google]

[Amazon]

Donald Allan Dunstan (21 September 1926 – 6 February 1999) was an Australian politician who served as the 35th

Dunstan was to become the most vocal opponent of the LCL Government of Sir Thomas Playford, strongly criticising its practice of electoral malapportionment, known as the Playmander, a pun on the term gerrymander. This system gave a disproportionate electoral weight to the LCL's rural base, with votes worth as much as ten times others − at the 1968 election the rural seat of

Dunstan was to become the most vocal opponent of the LCL Government of Sir Thomas Playford, strongly criticising its practice of electoral malapportionment, known as the Playmander, a pun on the term gerrymander. This system gave a disproportionate electoral weight to the LCL's rural base, with votes worth as much as ten times others − at the 1968 election the rural seat of

Amid the continuing uproar, Playford decided to grant clemency.Cockburn, p. 305. The Royal Commission concluded that the guilty verdict was sound. Although a majority of those who spoke out against the handling of the matter (including Dunstan) thought Stuart was probably guilty, the events provoked heated and bitter debate in South Australian society and destabilised Playford's administration,Cockburn, p. 308. while bringing much publicity to Dunstan.

From 1959 onwards, the LCL government clung to power with the support of two independents, as Labor gained momentum. Always at the forefront, Dunstan lambasted the government for perceived underspending on social welfare, education, health and the arts. Dunstan heavily promoted himself as a reformer.

In 1960, Dunstan became president of the State Labor Party. The year also saw the death of Opposition Leader

Amid the continuing uproar, Playford decided to grant clemency.Cockburn, p. 305. The Royal Commission concluded that the guilty verdict was sound. Although a majority of those who spoke out against the handling of the matter (including Dunstan) thought Stuart was probably guilty, the events provoked heated and bitter debate in South Australian society and destabilised Playford's administration,Cockburn, p. 308. while bringing much publicity to Dunstan.

From 1959 onwards, the LCL government clung to power with the support of two independents, as Labor gained momentum. Always at the forefront, Dunstan lambasted the government for perceived underspending on social welfare, education, health and the arts. Dunstan heavily promoted himself as a reformer.

In 1960, Dunstan became president of the State Labor Party. The year also saw the death of Opposition Leader

The Walsh Government implemented significant reform in its term of office.Parkin, pp. 294–295. Liquor, gambling and entertainment laws were overhauled and liberalised,Blewett and Jaensch, p. 37. social welfare was gradually expanded and

The Walsh Government implemented significant reform in its term of office.Parkin, pp. 294–295. Liquor, gambling and entertainment laws were overhauled and liberalised,Blewett and Jaensch, p. 37. social welfare was gradually expanded and

There was a degree of speculation in the press that Dunstan would call for a new election because of the adverse outcome. However, Dunstan realised the futility of such a move and instead sought to humiliate the LCL into bringing an end to malapportionment. Although Stott's decision to support the LCL ended any realistic chance of Dunstan remaining premier, Dunstan did not immediately resign his commission, intending to force Hall and the LCL to demonstrate that they had support on the floor of the Assembly when it reconvened. He used the six weeks before the start of the new legislature to draw attention to malapportionment. Protests were held on 15 March in

There was a degree of speculation in the press that Dunstan would call for a new election because of the adverse outcome. However, Dunstan realised the futility of such a move and instead sought to humiliate the LCL into bringing an end to malapportionment. Although Stott's decision to support the LCL ended any realistic chance of Dunstan remaining premier, Dunstan did not immediately resign his commission, intending to force Hall and the LCL to demonstrate that they had support on the floor of the Assembly when it reconvened. He used the six weeks before the start of the new legislature to draw attention to malapportionment. Protests were held on 15 March in

Dunstan wasted no time in organising his new ministry. He served as his own

Dunstan wasted no time in organising his new ministry. He served as his own  In 1972, the first major developments in regard to the state's population growth occurred. Adelaide's population was set to increase to 1.3million and the MATS plan and water-storage schemes were in planning to accommodate this. These were summarily rejected by the Dunstan Government, which planned to build a new city 83kilometres from Adelaide, near Murray Bridge. The city, to be known as Monarto, was to be built on farmland to the west of the existing town. Dunstan was very much against allowing Adelaide's suburbs to further sprawl, and thus Monarto was a major focus of his government. He argued that the new South Eastern Freeway would allow a drive of only 45 minutes from Adelaide, that the city was not far from current industry, and that water could be readily supplied from the

In 1972, the first major developments in regard to the state's population growth occurred. Adelaide's population was set to increase to 1.3million and the MATS plan and water-storage schemes were in planning to accommodate this. These were summarily rejected by the Dunstan Government, which planned to build a new city 83kilometres from Adelaide, near Murray Bridge. The city, to be known as Monarto, was to be built on farmland to the west of the existing town. Dunstan was very much against allowing Adelaide's suburbs to further sprawl, and thus Monarto was a major focus of his government. He argued that the new South Eastern Freeway would allow a drive of only 45 minutes from Adelaide, that the city was not far from current industry, and that water could be readily supplied from the  Having played a part in Labor's abandonment of the White Australia Policy at national level, Dunstan was also prominent in promoting

Having played a part in Labor's abandonment of the White Australia Policy at national level, Dunstan was also prominent in promoting  Dunstan called an election for March 1973, hoping to gain a mandate to seek changes to the council. The LCL were badly disunited; the more liberal wing of the party under Hall joined Dunstan in wanting to introduce universal suffrage for the upper house, while the more conservative members of the LCL did not. The conservatives then decided to limit Hall's powers, resulting in his resignation and creation of the breakaway Liberal Movement (LM), which overtly branded itself as a semi-autonomous component within the LCL. Labor capitalised on the opposition divisions to secure an easy victory. They campaigned under the slogan "South Australia's Doing Well with Labor", while the LCL was hampered by infighting; many LCL candidates were claiming different leaders in their electoral material depending on their factional allegiance.Parkin, p. 9. The Labor Party won with 51.5% of the primary vote and secured a second consecutive majority government with 26 seats. It was only the second time a Labor government in South Australia had been re-elected for a second term, the first being the early Thomas Price Labor government. It would be the first five-year-incumbent Labor government however. They also gained two more seats in the Legislative Council to have six of the twenty members.Parkin, p. 10. Labor entered the new term with momentum when a fortnight after the election, the LCL purged LM members from its ranks, forcing them to either quit the LM or leave the LCL and join the LM as a distinct party.

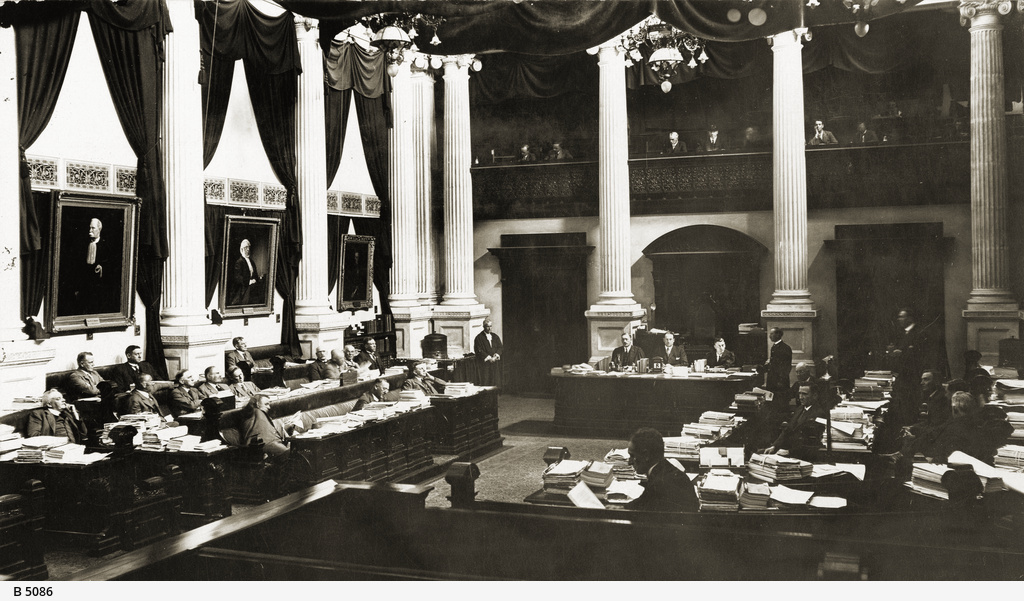

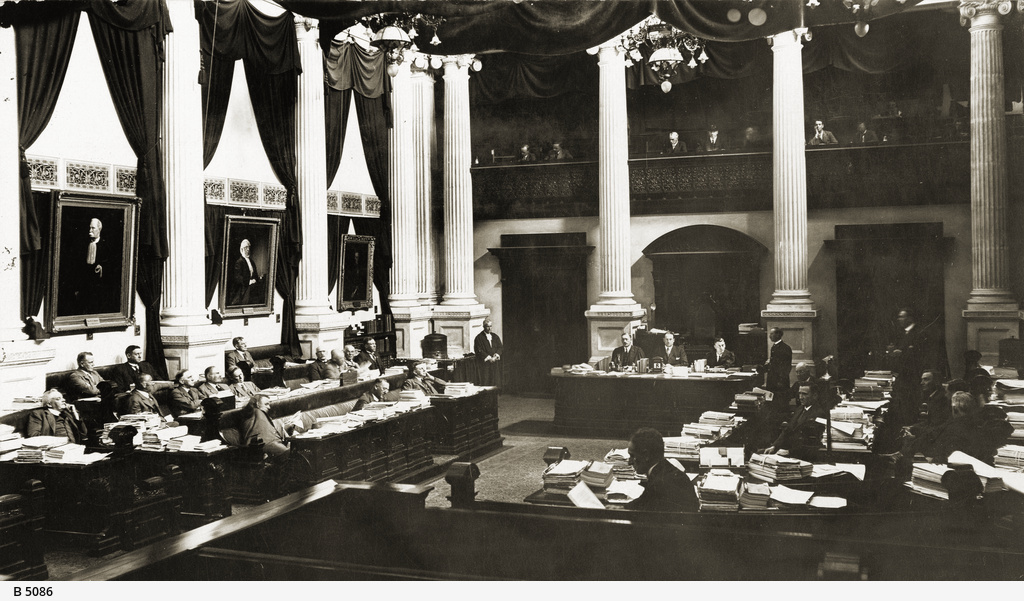

Dunstan saw reform of the Legislative Council as an important goal, and later a prime achievement, of his Government. Labor, as a matter of party policy, wanted to see the Legislative Council abolished. Dunstan, seeing this as unfeasible in his term, set about to reform it instead. Two bills were prepared for Legislative Council reform; one to lower the voting age to 18 and introduce

Dunstan called an election for March 1973, hoping to gain a mandate to seek changes to the council. The LCL were badly disunited; the more liberal wing of the party under Hall joined Dunstan in wanting to introduce universal suffrage for the upper house, while the more conservative members of the LCL did not. The conservatives then decided to limit Hall's powers, resulting in his resignation and creation of the breakaway Liberal Movement (LM), which overtly branded itself as a semi-autonomous component within the LCL. Labor capitalised on the opposition divisions to secure an easy victory. They campaigned under the slogan "South Australia's Doing Well with Labor", while the LCL was hampered by infighting; many LCL candidates were claiming different leaders in their electoral material depending on their factional allegiance.Parkin, p. 9. The Labor Party won with 51.5% of the primary vote and secured a second consecutive majority government with 26 seats. It was only the second time a Labor government in South Australia had been re-elected for a second term, the first being the early Thomas Price Labor government. It would be the first five-year-incumbent Labor government however. They also gained two more seats in the Legislative Council to have six of the twenty members.Parkin, p. 10. Labor entered the new term with momentum when a fortnight after the election, the LCL purged LM members from its ranks, forcing them to either quit the LM or leave the LCL and join the LM as a distinct party.

Dunstan saw reform of the Legislative Council as an important goal, and later a prime achievement, of his Government. Labor, as a matter of party policy, wanted to see the Legislative Council abolished. Dunstan, seeing this as unfeasible in his term, set about to reform it instead. Two bills were prepared for Legislative Council reform; one to lower the voting age to 18 and introduce

Whilst living in Norwood and studying at university, Dunstan met his first wife, Gretel Elsasser, whose Jewish family had fled

Whilst living in Norwood and studying at university, Dunstan met his first wife, Gretel Elsasser, whose Jewish family had fled

Don Dunstan FoundationDunstan Collection, Flinders University Library

, - , - , - , - , - , - , - , - {{DEFAULTSORT:Dunstan, Don 1926 births 1999 deaths Australian Labor Party members of the Parliament of South Australia Australian people of Cornish descent Australian King's Counsel Bisexual men Bisexual politicians Deaths from cancer in South Australia Companions of the Order of Australia Lawyers from Adelaide Leaders of the Opposition in South Australia LGBT legislators in Australia People educated at St Peter's College, Adelaide Politicians from Suva Premiers of South Australia Treasurers of South Australia Adelaide Law School alumni 20th-century Australian lawyers 20th-century Australian politicians Attorneys-General of South Australia 20th-century LGBT people

premier of South Australia

The premier of South Australia is the head of government in the state of South Australia, Australia. The Government of South Australia follows the Westminster system, with a Parliament of South Australia acting as the legislature. The premier is ...

from 1967 to 1968, and again from 1970 to 1979. He was a member of the House of Assembly

House of Assembly is a name given to the legislature or lower house of a bicameral parliament. In some countries this may be at a subnational level.

Historically, in British Crown colonies

A Crown colony or royal colony was a colony adm ...

(MHA) for the division of Norwood from 1953 to 1979, and leader of the South Australian Branch of the Australian Labor Party from 1967 to 1979. Before becoming premier, Dunstan served as the 38th attorney-general of South Australia

The attorney-general of South Australia is the Cabinet minister in the Government of South Australia who is responsible for that state's system of law and justice. The attorney-general must be a qualified legal practitioner, although this wa ...

and the treasurer of South Australia. He is the fourth longest serving premier in South Australian history.

In the late 1950s, Dunstan became well known for his campaign against the death penalty

Capital punishment, also known as the death penalty, is the state-sanctioned practice of deliberately killing a person as a punishment for an actual or supposed crime, usually following an authorized, rule-governed process to conclude that ...

being imposed on Max Stuart, who was convicted of rape and murder of a small girl, opposing then-Premier Thomas Playford IV over the matter. During Labor's time in opposition, Dunstan was prominent in securing some reforms in Aboriginal rights and in Labor abandoning the White Australia policy. Dunstan became Attorney-General

In most common law jurisdictions, the attorney general or attorney-general (sometimes abbreviated AG or Atty.-Gen) is the main legal advisor to the government. The plural is attorneys general.

In some jurisdictions, attorneys general also have exec ...

after the 1965 election, and replaced the older Frank Walsh as premier in 1967. Despite maintaining a much larger vote over the Liberal and Country League

Liberal or liberalism may refer to:

Politics

* a supporter of liberalism

** Liberalism by country

* an adherent of a Liberal Party

* Liberalism (international relations)

* Sexually liberal feminism

* Social liberalism

Arts, entertainment an ...

(LCL), Labor lost two seats at the 1968 election, with the LCL forming government with support of an independent. Dunstan responded by increasing his attacks on the Playmander, convincing the LCL into watering down the malapportionment. With little change in Labor's vote but with the Playmander removed, Labor won 27 of 47 seats at the 1970 election, and again in 1973, 1975

It was also declared the ''International Women's Year'' by the United Nations and the European Architectural Heritage Year by the Council of Europe.

Events

January

* January 1 - Watergate scandal (United States): John N. Mitchell, H. R. ...

, and 1977.

Dunstan's socially progressive administration saw Aboriginal land rights

Indigenous land rights are the rights of Indigenous peoples to land and natural resources therein, either individually or collectively, mostly in colonised countries. Land and resource-related rights are of fundamental importance to Indigenou ...

recognised, homosexuality decriminalised, the first female judge (Dame Roma Mitchell

Dame Roma Flinders Mitchell, (2 October 1913 – 5 March 2000) was an Australian lawyer, judge and state governor. She was the first woman to hold a number of positions in Australia – the country's first woman judge, the first woman to be a ...

) appointed, the first non-British governor

A governor is an administrative leader and head of a polity or political region, ranking under the head of state and in some cases, such as governors-general, as the head of state's official representative. Depending on the type of political ...

, Sir Mark Oliphant, and later the first Indigenous governor, Sir Douglas Nicholls. He enacted consumer protection

Consumer protection is the practice of safeguarding buyers of goods and services, and the public, against unfair practices in the marketplace. Consumer protection measures are often established by law. Such laws are intended to prevent business ...

laws, reformed and expanded the public education

State schools (in England, Wales, Australia and New Zealand) or public schools (Scottish English and North American English) are generally primary or secondary educational institution, schools that educate all students without charge. They are ...

and health systems, abolished the death penalty, relaxed censorship

Censorship is the suppression of speech, public communication, or other information. This may be done on the basis that such material is considered objectionable, harmful, sensitive, or "inconvenient". Censorship can be conducted by governments ...

and drinking laws, created a ministry for the environment, enacted anti-discrimination law

Anti-discrimination law or non-discrimination law refers to legislation designed to prevent discrimination against particular groups of people; these groups are often referred to as protected groups or protected classes. Anti-discrimination laws ...

, and implemented electoral reform

Electoral reform is a change in electoral systems which alters how public desires are expressed in election results. That can include reforms of:

* Voting systems, such as proportional representation, a two-round system (runoff voting), instant ...

s such as the overhaul of the Legislative Council, the upper house

An upper house is one of two chambers of a bicameral legislature, the other chamber being the lower house.''Bicameralism'' (1997) by George Tsebelis The house formally designated as the upper house is usually smaller and often has more restric ...

of Parliament

In modern politics, and history, a parliament is a legislative body of government. Generally, a modern parliament has three functions: representing the electorate, making laws, and overseeing the government via hearings and inquiries. Th ...

, lowered the voting age to 18, enacted universal suffrage

Universal suffrage (also called universal franchise, general suffrage, and common suffrage of the common man) gives the right to vote to all adult citizens, regardless of wealth, income, gender, social status, race, ethnicity, or political sta ...

, and completely abolished malapportionment. He also established Rundle Mall, enacted measures to protect buildings of historical heritage, and encouraging arts

The arts are a very wide range of human practices of creative expression, storytelling and cultural participation. They encompass multiple diverse and plural modes of thinking, doing and being, in an extremely broad range of media. Both ...

, with support for the Adelaide Festival Centre

Adelaide Festival Centre, Australia's first multi-purpose arts centre and the home of South Australia's performing arts, was built in the 1970s, designed by Hassell Architects. The Festival Theatre opened in June 1973 with the rest of the centr ...

, the State Theatre Company, and the establishment of the South Australian Film Corporation

South Australian Film Corporation (SAFC) is a South Australian Government statutory corporation established in 1972 to engage in film production and promote the film industry, located in Adelaide, South Australia. The Adelaide Studios are manage ...

.

At the same time, there were also problems; the economy began to stagnate, and the large increases to burgeoning public service

A public service is any service intended to address specific needs pertaining to the aggregate members of a community. Public services are available to people within a government jurisdiction as provided directly through public sector agencies ...

generated claims of waste. One of Dunstan's pet projects, a plan to build a new city at Monarto to alleviate urban pressures in Adelaide, was abandoned when economic and population growth stalled, with much money and planning already invested. After four consecutive election wins, Dunstan's administration began to falter in 1978 following his dismissal of Police Commissioner Harold Salisbury, as controversy broke out over whether he had improperly interfered with a judicial investigation. In addition, policy problems and unemployment began to mount, as well as unsubstantiated rumours of corruption and personal impropriety. The strain on Dunstan was increased by the death of his wife. His resignation from the premiership and politics in 1979 was abrupt after collapsing due to ill health, but he lived for another 20 years, remaining a vocal and outspoken campaigner for progressive social policy.

Early life

Dunstan was born on 21 September 1926 inSuva

Suva () is the capital and largest city of Fiji. It is the home of the country's largest metropolitan area and serves as its major port. The city is located on the southeast coast of the island of Viti Levu, in Rewa Province, Central Div ...

, Colony of Fiji

The Colony of Fiji was a Crown colony that existed from 1874 to 1970 in the territory of the present-day nation of Fiji. London declined its first opportunity to annex the Kingdom of Fiji in 1852. Ratu Seru Epenisa Cakobau had offered to c ...

, the son of Francis Vivian Dunstan and Ida May Dunstan (' Hill), Australians of Cornish descent. His parents had moved to Fiji in 1916 after his father took up a position as manager of the Adelaide Steamship Company

The Adelaide Steamship Company was an Australian shipping company and later a diversified industrial and logistics conglomerate. It was formed by a group of South Australian businessmen in 1875. Their aim was to control the transport of goods b ...

. He spent the first seven years of his life in Fiji, starting his schooling there. Dunstan was beset by illness, and his parents sent him to South Australia hoping the drier climate would assist his recovery. He lived in Murray Bridge for three years with his mother's parents before returning to Suva for a short period during his secondary education. During his time in Fiji, Dunstan mixed easily with the Indian settlers and indigenous people

Indigenous peoples are culturally distinct ethnic groups whose members are directly descended from the earliest known inhabitants of a particular geographic region and, to some extent, maintain the language and culture of those original people ...

, something that was frowned upon by many of the white people on the islands.

He won a scholarship

A scholarship is a form of financial aid awarded to students for further education. Generally, scholarships are awarded based on a set of criteria such as academic merit, diversity and inclusion, athletic skill, and financial need.

Scholars ...

in classical studies

Classics or classical studies is the study of classical antiquity. In the Western world, classics traditionally refers to the study of Classical Greek and Roman literature and their related original languages, Ancient Greek and Latin. Classics ...

and attended St Peter's College, a traditional private school for the sons of the Adelaide establishment

The Adelaide Establishment is the name given to the group of wealthy landowners and industrialists who have played a considerable role in the history of South Australia since its foundation in 1836. Based primarily in South Australia's capital Ad ...

. He developed public speaking and acting skills, winning the college's public speaking prize for two consecutive years. In 1943, he portrayed the title role in a production of John Drinkwater's play ''Abraham Lincoln

Abraham Lincoln ( ; February 12, 1809 – April 15, 1865) was an American lawyer, politician, and statesman who served as the 16th president of the United States from 1861 until his assassination in 1865. Lincoln led the nation throu ...

'', and according to the school magazine, he "was the chief contributor to the success of the occasion". His academic strengths were in classical history and languages, and he disliked mathematics.Yeeles, p. 15. He gained a reputation as a maverick. During this time, Dunstan did not board and lived in the seaside suburb of Glenelg with relatives. Dunstan completed his secondary schooling in 1943, ranking in the top 30 overall in the statewide matriculation examinations.Cockburn, p. 312.

In his youth, influenced by his uncle, former Liberal Lord Mayor of Adelaide Sir Jonathan Cain

Jonathan Leonard Friga (born February 26, 1950), known professionally as Jonathan Cain, is an American musician and songwriter best known as the keyboardist for Journey. He has also worked with the Babys and Bad English. Cain was inducted into ...

, Dunstan was a supporter of the conservative

Conservatism is a cultural, social, and political philosophy that seeks to promote and to preserve traditional institutions, practices, and values. The central tenets of conservatism may vary in relation to the culture and civilization in ...

Liberal and Country League

Liberal or liberalism may refer to:

Politics

* a supporter of liberalism

** Liberalism by country

* an adherent of a Liberal Party

* Liberalism (international relations)

* Sexually liberal feminism

* Social liberalism

Arts, entertainment an ...

(LCL) and handed out how-to-vote cards for the party at state elections. Dunstan later said of his involvement with the Liberals: "I do not call it snobbery to deride the Establishment in South Australia, I admit that I was brought up into it, and I admit that it gave me a pain." When asked of his roots, he said, "I'm a refugee from it and thank God for somewhere honest to flee to!"

His political awakening happened during his university years. Studying law and arts at the University of Adelaide

The University of Adelaide (informally Adelaide University) is a public research university located in Adelaide, South Australia. Established in 1874, it is the third-oldest university in Australia. The university's main campus is located on N ...

, he became very active, joining the University Socialist Club, the Fabian Society

The Fabian Society is a British socialist organisation whose purpose is to advance the principles of social democracy and democratic socialism via gradualist and reformist effort in democracies, rather than by revolutionary overthrow. T ...

, the Student Representative Council, as well as the Theatre Group. A two-week stint in the Communist Party

A communist party is a political party that seeks to realize the socio-economic goals of communism. The term ''communist party'' was popularized by the title of '' The Manifesto of the Communist Party'' (1848) by Karl Marx and Friedrich Engel ...

was followed by membership in the Australian Labor Party

The Australian Labor Party (ALP), also simply known as Labor, is the major centre-left political party in Australia, one of two major parties in Australian politics, along with the centre-right Liberal Party of Australia. The party forms t ...

.

Dunstan was markedly different from the general membership of the Labor Party of the time; upon applying for membership at Trades Hall, a Labor veteran supposedly muttered "how could that long-haired prick be a Labor man?"Yeeles, p. 17. His peculiarities, such as his upper-class accent, were a target of derision by the working-class Labor old guard throughout his early political involvement. Dunstan funded his education by working in theatre and radio during his university years. He eventually graduated with a double degree, with arts majors in Latin

Latin (, or , ) is a classical language belonging to the Italic languages, Italic branch of the Indo-European languages. Latin was originally a dialect spoken in the lower Tiber area (then known as Latium) around present-day Rome, but through ...

, comparative philology

Comparative linguistics, or comparative-historical linguistics (formerly comparative philology) is a branch of historical linguistics that is concerned with comparing languages to establish their historical relatedness.

Genetic relatedness ...

, history and politics, and he came first in political science.

After Dunstan graduated, he moved with his wife to Fiji where he was admitted to the bar and began his career as a lawyer. They returned to Adelaide in 1951 and settled in George Street, Norwood, taking in boarders as a source of extra income.Dunstan, pp. 25–32.

Political beginnings

Dunstan was nominated as the Labor candidate for the electoral district of Norwood at the 1953 election. His campaign was noted for his colourful methods to sway voters: posters of his face were placed on every pole in the district, and Labor supporters walked the streets advocating Dunstan. He targeted in particular the large Italian migrant population of the district, distributing translated copies of a statement the sitting LCL member Roy Moir had made about immigrants. Moir had commented that "these immigrants are of no use to usa few of them are tradesmen but most of them have no skills at all. And when they intermarry we'll have all the colours of the rainbow." Dunstan won the seat and was elected to theSouth Australian House of Assembly

The House of Assembly, or lower house, is one of the two chambers of the Parliament of South Australia. The other is the Legislative Council. It sits in Parliament House in the state capital, Adelaide.

Overview

The House of Assembly was crea ...

. His son Andrew was born nine months after the win.Dunstan, pp. 35–36.Crocker, p. 115.

Frome

Frome ( ) is a town and civil parish in eastern Somerset, England. The town is built on uneven high ground at the eastern end of the Mendip Hills, and centres on the River Frome. The town, about south of Bath, is the largest in the Mendip d ...

had 4,500 formal votes, while the metropolitan seat of Enfield had 42,000 formal votes. He added colour and flair to debate in South Australian politics, changing the existing "gentlemanly" method of conducting parliamentary proceedings. He did not fear direct confrontation with the incumbent government and attacked it with vigour. Up to this point most of his Labor colleagues had become dispirited by the Playmander and were resigned to the ongoing dominance of Playford and LCL, so they sought to influence policy through collaborative legislating.Cockburn, p. 314.

In 1954, the LCL introduced the Government Electoral Bill, which was designed to further accentuate the undue weight favouring rural voters. During the debate, Dunstan decried this "immoral Bill... I cannot separate it from the motives of those who put it forward. Since it is immoral, so are they." Such language, unusually aggressive by the prevailing standards, resulted in Dunstan's removal from the parliamentary chambers after he refused a request from the Speaker to retract his remark. The first parliamentarian to be expelled in years, Dunstan found himself on the front pages of newspapers for the first time. Nevertheless, he was not able to build up much of a profile in his first few years as '' The Advertiser'', the dominant newspaper in the city, had a policy of ignoring the young politician's activities—its editor Lloyd Dumas was the father of one of Dunstan's first girlfriends.

Max Stuart trial

In December 1958 there occurred an event that initially had nothing to do with Playford, but eventually intensified into a debacle regarded as a turning point in his premiership and marked the end of his rule. Dunstan was prominent in pressuring Playford during this time.Cockburn, p. 292. A young girl was found raped and murdered, and Max Stuart, an Aboriginal man, was convicted and sentenced to be executed. Stuart's lawyer claimed that the confession was forced, and appeals to the Supreme andHigh Courts

High may refer to:

Science and technology

* Height

* High (atmospheric), a high-pressure area

* High (computability), a quality of a Turing degree, in computability theory

* High (tectonics), in geology an area where relative tectonic uplift ...

were dismissed. Amid objections against the fairness of the trial among an increasing number of legal academics and judges, ''The News'' brought much attention to Stuart's plight with an aggressive, tabloid-style campaign.Cockburn, p. 297.

When Playford and the Executive Council decided not to reprieve Stuart, an appeal to the Privy Council

A privy council is a body that advises the head of state of a state, typically, but not always, in the context of a monarchic government. The word "privy" means "private" or "secret"; thus, a privy council was originally a committee of the mo ...

was made to stall the execution. Spearheaded by Dunstan, Labor then tried to introduce legislation to stall the hanging.Cockburn, p. 299. Amid hue and cry, Playford started a Royal Commission to review the case. However, two of the commissioners had already been involved in the trial and one of the appeals. This provoked worldwide controversy with claims of bias from Dunstan and Labor, who also attacked Playford for what they regarded as a too-restrictive scope of inquiry.Cockburn, p. 303.

The Royal Commission began its work and the proceedings were followed closely and eagerly debated by the public. As Playford did not commute Stuart's sentence, Dunstan introduced a bill to abolish capital punishment

Capital punishment, also known as the death penalty, is the state-sanctioned practice of deliberately killing a person as a punishment for an actual or supposed crime, usually following an authorized, rule-governed process to conclude that ...

. The vote was split along party lines and was thus defeated, but Dunstan used the opportunity to attack the Playmander with much effect in the media, portraying the failed legislation as an unjust triumph of a malapportioned minority who had a vengeance mentality over an electorally repressed majority who wanted a humane outcome.

Amid the continuing uproar, Playford decided to grant clemency.Cockburn, p. 305. The Royal Commission concluded that the guilty verdict was sound. Although a majority of those who spoke out against the handling of the matter (including Dunstan) thought Stuart was probably guilty, the events provoked heated and bitter debate in South Australian society and destabilised Playford's administration,Cockburn, p. 308. while bringing much publicity to Dunstan.

From 1959 onwards, the LCL government clung to power with the support of two independents, as Labor gained momentum. Always at the forefront, Dunstan lambasted the government for perceived underspending on social welfare, education, health and the arts. Dunstan heavily promoted himself as a reformer.

In 1960, Dunstan became president of the State Labor Party. The year also saw the death of Opposition Leader

Amid the continuing uproar, Playford decided to grant clemency.Cockburn, p. 305. The Royal Commission concluded that the guilty verdict was sound. Although a majority of those who spoke out against the handling of the matter (including Dunstan) thought Stuart was probably guilty, the events provoked heated and bitter debate in South Australian society and destabilised Playford's administration,Cockburn, p. 308. while bringing much publicity to Dunstan.

From 1959 onwards, the LCL government clung to power with the support of two independents, as Labor gained momentum. Always at the forefront, Dunstan lambasted the government for perceived underspending on social welfare, education, health and the arts. Dunstan heavily promoted himself as a reformer.

In 1960, Dunstan became president of the State Labor Party. The year also saw the death of Opposition Leader Mick O'Halloran

Michael Raphael O'Halloran (12 April 1893 – 22 September 1960) was an Australian politician, representing the South Australian Branch of the Australian Labor Party. He served as Leader of the Opposition in the Parliament of South Australia ...

and his replacement by Frank Walsh. Dunstan attempted to win the position of Opposition Leader and, failing that, Deputy Leader. However, the Labor caucus

A caucus is a meeting of supporters or members of a specific political party or movement. The exact definition varies between different countries and political cultures.

The term originated in the United States, where it can refer to a meeting ...

was sceptical of his age and inexperience, and he failed to gain either position, albeit narrowly.

Ascent to power

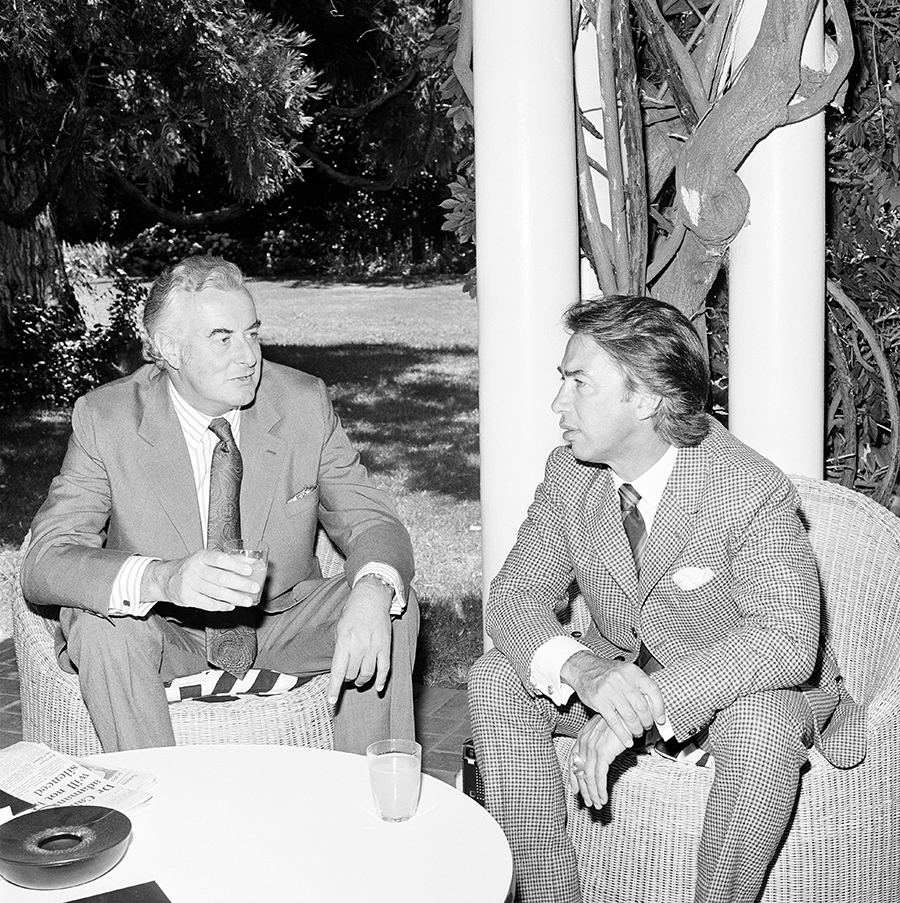

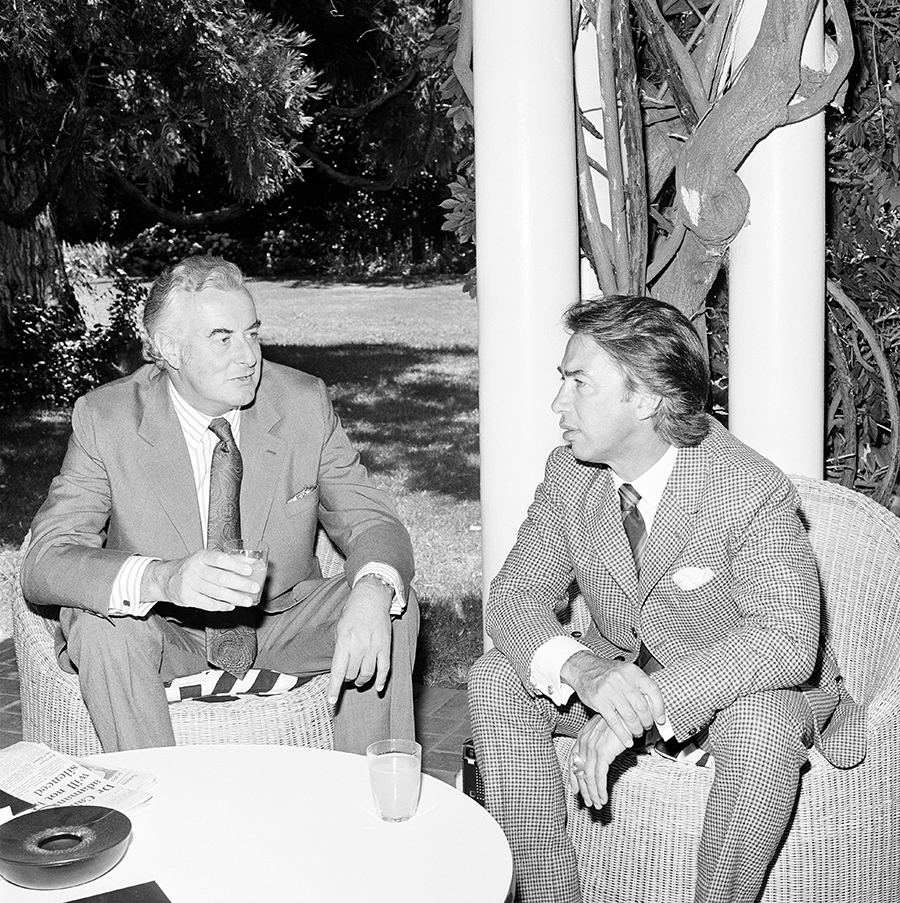

Federally, Dunstan, together with fellow Australian Fabian Society memberGough Whitlam

Edward Gough Whitlam (11 July 191621 October 2014) was the 21st prime minister of Australia, serving from 1972 to 1975. The longest-serving federal leader of the Australian Labor Party (ALP) from 1967 to 1977, he was notable for being the h ...

, set about removing the White Australia policy from the Labor platform. The older trade-unionist-based members of the Labor Party vehemently opposed changing the status quo. However, the "New Guard" of the party, of which Dunstan was a part, were determined to bring about its end. Attempts in 1959 and 1961 failed, with Labor leader Arthur Calwell

Arthur Augustus Calwell (28 August 1896 – 8 July 1973) was an Australian politician who served as the leader of the Labor Party from 1960 to 1967. He led the party to three federal elections.

Calwell grew up in Melbourne and attended St J ...

stating, "It would ruin the Party if we altered the immigration policy... it was only cranks, long hairs, academics and do-gooders who wanted the change." However, Dunstan persisted in his efforts, and in 1965 it was removed from the Labor platform at their national conference; Dunstan personally took credit for the change. Whitlam later brought about the comprehensive end of the White Australia policy in 1973 as Prime Minister of Australia

The prime minister of Australia is the head of government of the Commonwealth of Australia. The prime minister heads the executive branch of the federal government of Australia and is also accountable to federal parliament under the princip ...

.

Dunstan pursued similar reforms with respect to Indigenous Australians

Indigenous Australians or Australian First Nations are people with familial heritage from, and membership in, the ethnic groups that lived in Australia before British colonisation. They consist of two distinct groups: the Aboriginal peoples ...

. In 1962, the Aboriginal Affairs Bill was introduced to liberalise constraints that had been placed on Indigenous Australians in the past and had effectively resulted in segregation. The initial proposal still retained some restrictions, placing more controls over full-blooded Aboriginal people. Dunstan was prominent in Labor's opposition to the double standards,Summers, p. 495. and called for abolition of race-based restrictions, saying that social objectives could be achieved without explicit colour-based schemes. He was successful in forcing amendments to liberalise controls on property and the confinement of Indigenous Australians to Aboriginal reserve

An Aboriginal reserve, also called simply reserve, was a government-sanctioned settlement for Aboriginal Australians, created under various state and federal legislation. Along with missions and other institutions, they were used from the 19th c ...

s. However, his attempt to remove the different standards required of part and full-blooded Aboriginal people failed, as did his proposal to ensure that at least half of the members of the Aboriginal Affairs Board be Indigenous Australians.Summers, p. 496. Despite the passage of the bill, restrictions remained in place and Dunstan questioned the policy of assimilation

Assimilation may refer to:

Culture

* Cultural assimilation, the process whereby a minority group gradually adapts to the customs and attitudes of the prevailing culture and customs

** Language shift, also known as language assimilation, the prog ...

of Aboriginal people, which he saw as the diluting of their distinctive cultures.Summers, p. 497.

Labor won the seats of Glenelg and Barossa at the 1965 election, after winning the seats of Chaffey and Unley

Unley is an inner-southern suburb of Adelaide, South Australia, within the City of Unley. The suburb is the home of the Sturt Football Club in the South Australian National Football League (SANFL). Unley neighbours Adelaide Park Lands, Fullarton ...

at the 1962 election. Labor thus finally overcame the Playmander and formed government for the first time in 32 years, with Frank Walsh as Premier of South Australia

The premier of South Australia is the head of government in the state of South Australia, Australia. The Government of South Australia follows the Westminster system, with a Parliament of South Australia acting as the legislature. The premier is ...

. Despite winning 55 percent of the primary vote, the Playmander was still strong enough that Labor won only 21 of 39 seats, a two-seat majority. Dunstan became Attorney-General

In most common law jurisdictions, the attorney general or attorney-general (sometimes abbreviated AG or Atty.-Gen) is the main legal advisor to the government. The plural is attorneys general.

In some jurisdictions, attorneys general also have exec ...

and Minister of Community Welfare and Aboriginal Affairs. He was far and away the youngest member of the cabinet; he was the only minister under 50,Parkin, p. 3. and one of only three under 60.Parkin, p. 293. Dunstan had a major impact on Government policy as Attorney-General. Having only narrowly lost out on the leadership in 1960, Dunstan became the obvious successor to the 67-year-old Walsh, who was due to retire in 1967 under Labor rules of the time.

Aboriginal reserve

An Aboriginal reserve, also called simply reserve, was a government-sanctioned settlement for Aboriginal Australians, created under various state and federal legislation. Along with missions and other institutions, they were used from the 19th c ...

s were created. Strong restrictions on Aboriginal access to liquor were lifted. Women's working rights were granted under the mantra of "equal pay for work of equal value", and racial discrimination legislation was enacted. Town planning was codified in law,Blewett and Jaensch, p. 39. and the State Planning Authority was created to oversee development. Workers were given more rights and the bureaucracy of the education department was liberalised. Much of the reform was not necessarily radical and was primarily to "fill the gaps" that the previous LCL government had left. Despite a consistently higher statewide vote, Labor were consistently outnumbered 16–4 in the Legislative Council, so some desired legislation did not make it through. In 1965, the legislature convened for 65 days, the most for 34 years, but many bills were still yet to be debated.

Many bills were watered down,Parkin, p. 295. but due to lack of public interest, outcry was minimal. In particular, the council blocked electoral reform legislation, paving the way for a probable LCL win at the next election. Such was Dunstan's pre-eminence during his term as Attorney-General that the cabinet was often called the "Dunstan Ministry".Parkin, p. 294.Blewett and Jaensch, p. 36.

An economic depression had begun in South Australia after the Labor government gained office in 1965; unemployment went from the lowest in the country to the second highest, while immigration levels dropped. Labor was not responsible for the depression, although it initially did little to alleviate it. The Liberals seized on this opportunity, blaming it on "twelve months of Socialist administration in South Australia" and branding it the "Dunstan Depression".Blewett and Jaensch, p. 46.

In the 1966 Australian federal election, Labor suffered a swing against it of 11.8% in South Australia, double the national average. If this was replicated at a state election, it was projected that Labor would hold only ten of the 39 seats. The Liberals dropped Playford as the state leader, and the younger and more progressive Steele Hall

Raymond Steele Hall (born 30 November 1928) is a former Australian politician who served as the 36th Premier of South Australia from 1968 to 1970. He also served in the federal Parliament as a senator for South Australia from 1974 to 1977 and ...

took his place. In a dire situation with the next state election looming,Blewett and Jaensch, pp. 50–51. Labor changed leaders with Walsh, a "neanderthal figure in the television age", standing down in May 1967. Much of the Labor Right faction, as well as Walsh, was opposed to Dunstan taking the leadership, but no other MPs had the same charisma or eloquence. Eventually, Dunstan won the leadership over Des Corcoran

James Desmond Corcoran AO (8 November 1928 – 3 January 2004) was an Australian politician, representing the South Australian Branch of the Australian Labor Party. He was the 37th Premier of South Australia, serving between 15 February 1979 ...

, winning fourteen votes to eleven on the strength of rural and marginal Laborites, having trailed by one vote on the first count before less popular candidates were eliminated.

Dunstan's first Premiership was eventful, with a steady stream of reform and attempts to end the depression. The latter half of 1967 saw the beginnings of a slight recovery, with unemployment dipping and industrial capacity steadying. The 1967–68 budget ran into deficit, allocating funds to energise the economic engine whilst Dunstan lambasted the Federal Government for neglecting the South Australian economy, demanding it take a degree of responsibility for its ills.

Elections 1968–1970

In preparation for the 1968 election, Labor campaigned heavily around its leader, and this resonated with voters; in surveys conducted in parts of the metropolitan area, 84% of respondents declared their approval of Dunstan.Blewett and Jaensch, pp. 65–66. In a presidential-style election campaign, Hall and Dunstan journeyed across the state advocating their platforms, and the major issues were the leaders, the Playmander and the economy. Television saw its first major use in the election, and Dunstan, an astute public speaker, successfully mastered it.Blewett and Jaensch, pp. 60–61, 90–100. With his upbeat style, Dunstan also made an impact in the print media, which had long been a bastion of the LCL. Despite winning a 52% majority of the primary vote, and 54% of the two-party preferred count, Labor lost two seats, resulting in a hung parliament: the LCL and Labor each had 19 seats. Had 21 votes in the rural seat ofMurray

Murray may refer to:

Businesses

* Murray (bicycle company), an American manufacturer of low-cost bicycles

* Murrays, an Australian bus company

* Murray International Trust, a Scottish investment trust

* D. & W. Murray Limited, an Australian who ...

gone the other way, Labor would have retained power. The balance of power rested with the chamber's lone independent, Tom Stott

Tom Cleave Stott CBE (6 June 1899 – 21 October 1976) spent 37 years as an independent member of the South Australian House of Assembly, from 1933 to 1970. He served as Speaker of the House from 1962 to 1965 for the Tom Playford LCL governm ...

, who was offered the speakership by the LCL in return for his support on the Assembly floor. Stott, a conservative, agreed to support the LCL.Parkin, p. 4.

There was a degree of speculation in the press that Dunstan would call for a new election because of the adverse outcome. However, Dunstan realised the futility of such a move and instead sought to humiliate the LCL into bringing an end to malapportionment. Although Stott's decision to support the LCL ended any realistic chance of Dunstan remaining premier, Dunstan did not immediately resign his commission, intending to force Hall and the LCL to demonstrate that they had support on the floor of the Assembly when it reconvened. He used the six weeks before the start of the new legislature to draw attention to malapportionment. Protests were held on 15 March in

There was a degree of speculation in the press that Dunstan would call for a new election because of the adverse outcome. However, Dunstan realised the futility of such a move and instead sought to humiliate the LCL into bringing an end to malapportionment. Although Stott's decision to support the LCL ended any realistic chance of Dunstan remaining premier, Dunstan did not immediately resign his commission, intending to force Hall and the LCL to demonstrate that they had support on the floor of the Assembly when it reconvened. He used the six weeks before the start of the new legislature to draw attention to malapportionment. Protests were held on 15 March in Light Square

Light Square, also known as Wauwi (formerly Wauwe), is one of five public squares in the Adelaide city centre. Located in the centre of the north-western quarter of the Adelaide city centre, its southern boundary is Waymouth Street, while Curri ...

. There, Dunstan spoke to a crowd of more than ten thousand: "We need to show that the people of SA feel that at last the watershed has been reached in this, and that they will not continue to put up with a system which is as undemocratic as the present one in SA." On 16 April, the first day of the new House's sitting, Dunstan lost a confidence vote. With it now clear that the LCL had control of the House, Dunstan tendered his resignation to Governor

A governor is an administrative leader and head of a polity or political region, ranking under the head of state and in some cases, such as governors-general, as the head of state's official representative. Depending on the type of political ...

Edric Bastyan

Lieutenant General Sir Edric Montague Bastyan, (5 April 1903 – 6 October 1980) was a senior British Army officer, who became Governor of South Australia from 4 April 1961 until 1 June 1968 then Governor of Tasmania from 2 December 1968 until 30 ...

.Parkin, p. 5.Blewett and Jaensch, pp. 173–177. Hall was then sworn in as premier. However, the six weeks of protesting had brought nationwide criticism of the unfairness of the electoral system and put more pressure on the LCL to relent to reforms; it has been seen as one of the most important political events of its time.

With the end of Playford's tenure, the LCL had brought younger, more progressive members into its ranks. The Hall Government continued many of the social reforms the Walsh/Dunstan governments had initiated; most of these at the instigation of Hall or his Attorney-General, Robin Millhouse. Abortion

Abortion is the termination of a pregnancy by removal or expulsion of an embryo or fetus. An abortion that occurs without intervention is known as a miscarriage or "spontaneous abortion"; these occur in approximately 30% to 40% of pre ...

was partially legalised, and planning for the Festival Centre began. The conservative and rural factions of the League, notably in the Legislative Council dominated by the landed gentry, were bitterly opposed to some reforms, and more than once Hall was forced to rely on Labor support to see bills passed. The LCL began to break apart; what had once been a united party was now factionalised into four distinct groups across the political spectrum. The economy of South Australia began to pick up under Hall, returning to full employment. During the term in opposition, Des Corcoran

James Desmond Corcoran AO (8 November 1928 – 3 January 2004) was an Australian politician, representing the South Australian Branch of the Australian Labor Party. He was the 37th Premier of South Australia, serving between 15 February 1979 ...

became Dunstan's deputy, and the pair worked together well despite any rift that may have been caused by the struggle to succeed Walsh.

Hall was embarrassed that the LCL was in a position to win government despite having clearly lost the first-preference vote, and was committed to a fairer electoral system. Soon after taking office, he enacted a complete overhaul of the electoral system. While they fell short of "one vote one value

In Australia, one vote, one value is a democratic principle, applied in electoral laws governing redistributions of electoral divisions of the House of Representatives. The principle calls for all electoral divisions to have the same number of e ...

" as Labor and Dunstan had demanded, they were still significant. Under the Playmander the lower house had 39 seats, 13 in Adelaide and 26 in the country. Hall's reforms expanded the lower house to 47 seats–28 in Adelaide and 19 in the country. While there was still a slight rural weighting (since Adelaide accounted for two-thirds of the state's population), with Adelaide now electing a majority of the legislature, historical results made a Labor win at the next election likely. The capital had been SA Labor's power base for three decades. Even at the height of Playford's power in the 1950s, the LCL won almost no seats in the capital outside of the wealthy eastern crescent and around Holdfast Bay

The Holdfast Bay is a small bay in Gulf St Vincent, next to Adelaide, South Australia. Along its shores lie the local government area of the City of Holdfast Bay and the suburbs of Glenelg and Glenelg North

European settlement on Holdfast Bay ...

. This was a major reason why Playford's LCL never held more than 23 seats–two more than needed to govern. Under the circumstances, conventional wisdom was that Hall undertook electoral reform knowing he was effectively handing the premiership to Dunstan at the next election.

Stott withdrew support in 1970 over the Chowilla Dam

Chowilla Dam was a proposed water storage reservoir on the Murray River in the 1960s. The dam wall would have been in South Australia, but the reservoir behind it would have stretched upstream into Victoria and New South Wales. The site was sele ...

, a dispute over the location of a dam on the Murray River

The Murray River (in South Australia: River Murray) (Ngarrindjeri: ''Millewa'', Yorta Yorta: ''Tongala'') is a river in Southeastern Australia. It is Australia's longest river at extent. Its tributaries include five of the next six longest ...

,Parkin, p. 6. and South Australia went to the polls. The dam controversy was not much of an election issue, and attempts by the Democratic Labor Party to portray Dunstan as a communist over his opposition to ongoing Australian support for South Vietnam

South Vietnam, officially the Republic of Vietnam ( vi, Việt Nam Cộng hòa), was a state in Southeast Asia that existed from 1955 to 1975, the period when the southern portion of Vietnam was a member of the Western Bloc during part of th ...

had little effect. The LCL campaigned heavily on Hall, while Dunstan promised sweeping social reform, artistic transformation and more community services. He said "We'll set a new standard of social advancement that the whole of Australia will envy. We believe South Australia can set the pace. It can happen here. We can do it." Dunstan won the 1970 South Australian state election easily, taking 27 seats compared with the LCL's 20. Although the share of the votes had been similar to 1968, the dilution of the Playmander had changed the share of the seats. As Labor had attained a majority of the popular vote for a long period, and because malapportionment had been largely ended, the political scientists Neal Blewett and Dean Jaensch

Dean Harold Jaensch (27 October 1936 – 17 January 2022) was an Australian political scientist and a Professor of Political and International Studies at The Flinders University of South Australia. Jaensch was awarded a Bachelor of Arts (Hon ...

said: "A Dunstan decade seems assured."

Dunstan decade

Dunstan wasted no time in organising his new ministry. He served as his own

Dunstan wasted no time in organising his new ministry. He served as his own Treasurer

A treasurer is the person responsible for running the treasury of an organization. The significant core functions of a corporate treasurer include cash and liquidity management, risk management, and corporate finance.

Government

The treasury ...

, and took several other portfolios for himself. Deputy Premier Des Corcoran

James Desmond Corcoran AO (8 November 1928 – 3 January 2004) was an Australian politician, representing the South Australian Branch of the Australian Labor Party. He was the 37th Premier of South Australia, serving between 15 February 1979 ...

took on most infrastructure portfolios: Marine and Harbours, and Public Works. Corcoran became the face of the Dunstan ministry in its relationship with the Labor caucus, with his ability to use his strong manner to settle disputes. Bert Shard became Health Minister, overseeing the construction and planning of new, major public hospitals: the Flinders Medical Centre and Modbury Hospital. Hugh Hudson took on the Education portfolio, an important role in a government that was determined to bring about profound change to the South Australian education system. Geoff Virgo

Geoffrey Thomas Virgo (9 November 1918 – 5 January 2001) was an Australian politician.

Political career

From 2 March 1968 to 29 May 1970 he represented the electoral district of Edwardstown in the South Australian House of Assembly as a ...

, the new Transport Minister, was to deal with the Metropolitan Adelaide Transport Study (MATS) plans. Len King

Leonard James King (1 May 1925 – 23 June 2011) was an Australian politician, lawyer and judge.

Early life

King matriculated from St Joseph's Memorial School at age 14, then worked at Shell Company as a clerk. He served in the Royal Aus ...

was made Attorney-General and Aboriginal Affairs Minister despite being a new member of parliament. Dunstan formed a strong circle of loyal ministers around him, in a style radically different from his predecessors.Dunstan, pp. 172–173.

Soon after the election, Dunstan travelled to Canberra

Canberra ( )

is the capital city of Australia. Founded following the federation of the colonies of Australia as the seat of government for the new nation, it is Australia's largest inland city and the eighth-largest city overall. The ci ...

for the annual Premiers' Conference as the sole Labor premier. His Government, on a mandate to dramatically increase funding in key areas, sought to appropriate further finances from the Federal Government. This brought Dunstan into conflict with Prime Minister John Gorton

Sir John Grey Gorton (9 September 1911 – 19 May 2002) was an Australian politician who served as the nineteenth Prime Minister of Australia, in office from 1968 to 1971. He led the Liberal Party during that time, having previously been a l ...

, and federal funding to SA was not increased. An appeal was made to the Federal Grants Commission, and Dunstan was awarded more than he had hoped for. In addition to the money received from the Grants Commission, funds were diverted from water-storage schemes in the Adelaide Hills over the advice of engineers, and cash reserves were withdrawn from the two government-owned banks. The monies were subsequently used to finance health, education and arts schemes.

On the death in office of Governor

A governor is an administrative leader and head of a polity or political region, ranking under the head of state and in some cases, such as governors-general, as the head of state's official representative. Depending on the type of political ...

Sir James Harrison in 1971, Dunstan finally had the opportunity to put forward a nominee for governor of his own choosing to HM Queen Elizabeth II (and by extension the British Foreign Office which still technically oversaw the appointment process of Australian state governors until the '' Australia Act 1986''): Sir Mark Oliphant, a physicist who had worked on the Manhattan Project

The Manhattan Project was a research and development undertaking during World War II that produced the first nuclear weapons. It was led by the United States with the support of the United Kingdom and Canada. From 1942 to 1946, the project w ...

. Dunstan had never been happy that governors were usually British ex-servicemen and it was a personal goal of his to see an active and notable South Australian take on the role; Sir Mark Oliphant was uneventfully sworn in. Although the post is mostly ceremonial (with the exception of constitutional responsibilities), Oliphant brought energy to the role and he used his stature to decry damage to the environment caused by deforestation, excessive open-cut mining and pollution. Oliphant's tenure was successful and held in high regard, although he did come into conflict with the premier at times as both men were outspoken and strong-willed.

In 1972, the first major developments in regard to the state's population growth occurred. Adelaide's population was set to increase to 1.3million and the MATS plan and water-storage schemes were in planning to accommodate this. These were summarily rejected by the Dunstan Government, which planned to build a new city 83kilometres from Adelaide, near Murray Bridge. The city, to be known as Monarto, was to be built on farmland to the west of the existing town. Dunstan was very much against allowing Adelaide's suburbs to further sprawl, and thus Monarto was a major focus of his government. He argued that the new South Eastern Freeway would allow a drive of only 45 minutes from Adelaide, that the city was not far from current industry, and that water could be readily supplied from the

In 1972, the first major developments in regard to the state's population growth occurred. Adelaide's population was set to increase to 1.3million and the MATS plan and water-storage schemes were in planning to accommodate this. These were summarily rejected by the Dunstan Government, which planned to build a new city 83kilometres from Adelaide, near Murray Bridge. The city, to be known as Monarto, was to be built on farmland to the west of the existing town. Dunstan was very much against allowing Adelaide's suburbs to further sprawl, and thus Monarto was a major focus of his government. He argued that the new South Eastern Freeway would allow a drive of only 45 minutes from Adelaide, that the city was not far from current industry, and that water could be readily supplied from the River Murray

The Murray River (in South Australia: River Murray) (Ngarrindjeri: ''Millewa'', Yorta Yorta: ''Tongala'') is a river in Southeastern Australia. It is Australia's longest river at extent. Its tributaries include five of the next six longest ...

. The government hoped Adelaide would not sprawl into the Mount Lofty Ranges to the east and that the bureaucracy would be dispersed from the capital. In contrast, public servants feared being forced into the rural settlement. Critics (of whom there were many) derided the project as "Dunstan's Versailles in the bush".Whitelock, p. 149. Environmental activists aired fears of the effects of Monarto on the River Murray, which was already suffering from pollution and salinity problems. Later on, it was noticed that there was hard bedrock underneath the ground, raising drainage problems.

From 1970 to 1973, much legislation passed through the South Australian Parliament. Workers saw increases in welfare,Parkin, p. 7. drinking laws were further liberalised, an Ombudsman

An ombudsman (, also ,), ombud, ombuds, ombudswoman, ombudsperson or public advocate is an official who is usually appointed by the government or by parliament (usually with a significant degree of independence) to investigate complaints and at ...

was created, censorship was liberalised,Whitelock, p. 145. seat belts were made mandatory, the education system was overhauled, and the public service was gradually increased (doubling in size during the Dunstan era). Adelaide's water supply was fluoridated in 1971 and the age of majority was lowered from 21 to 18. A Commissioner of Consumer Affairs was created, a demerit point system was introduced to penalise poor driving practices in an attempt to cut the road toll, and compensation for workers was improved. Police autonomy and powers were restricted following a rally in opposition to the Vietnam War, which was broken up by police, although Dunstan had wanted the demonstrators to be able to close off the street. A royal commission was called into the police commissioner's disregard for Dunstan's orders, and resulted in legislation giving the government more control over the police; the commissioner then retired. The dress code for the Parliament

In modern politics, and history, a parliament is a legislative body of government. Generally, a modern parliament has three functions: representing the electorate, making laws, and overseeing the government via hearings and inquiries. Th ...

was relaxed during this period, the suit and tie was no longer seen as obligatory, and Dunstan himself caused media frenzy when he arrived at Parliament House in 1972 wearing pink shorts that ended above his knees. After his departure from public life he admitted that his sartorial statement may have gone beyond the limits. Nevertheless, his fashion sense resulted in his being voted "the sexiest political leader in Australia" by ''Woman's Day'' in 1975, and the image of Dunstan in the shorts remains iconic.

Having played a part in Labor's abandonment of the White Australia Policy at national level, Dunstan was also prominent in promoting

Having played a part in Labor's abandonment of the White Australia Policy at national level, Dunstan was also prominent in promoting multiculturalism

The term multiculturalism has a range of meanings within the contexts of sociology, political philosophy, and colloquial use. In sociology and in everyday usage, it is a synonym for " ethnic pluralism", with the two terms often used interchang ...

. He was well known for his attendance at and patronage of Cornish, Italian and Greek Australian

Greek Australians ( el, Ελληνοαυστραλοί, ) are Australians of Greek ancestry. Greek Australians are one of the largest groups within the global Greek diaspora. As per the 2021 census, 424,750 people stated that they had Greek an ...

cultural festivals and his appreciation of Asian art, and sought to build on cultural respect to create trade links with Asia. Dunstan's involvement in such cultural exchanges was also credited with generating strong support for Labor from ethnic and non-Anglo-Saxon immigrant communities,Whitelock, p. 150. although it was viewed with suspicion by some in the Anglo-Saxon establishment.Whitelock, p. 151. Dunstan himself later recalled: "When I proposed the establishment of a Cornish Festival, in Australia's 'Little Cornwall', people of Cornish descent came flocking."

Having been vocal in criticising Playford for sacrificing heritage to the march of development, Dunstan was prominent in protecting historic buildings from being bulldozed for high-rise office blocks. In 1972, the government intervened to purchase and thereby save Edmund Wright House on King William Street from being replaced with a skyscraper. In 1975, the Customs House at Semaphore

Semaphore (; ) is the use of an apparatus to create a visual signal transmitted over distance. A semaphore can be performed with devices including: fire, lights, flags, sunlight, and moving arms. Semaphores can be used for telegraphy when arr ...

was purchased to save it from demolition. His support of heritage preservation overlapped with his promotion of gourmet dining when his personal efforts helped to save the historic Ayers House on North Terrace, having it converted into a restaurant to avoid demolition.Whitelock, p. 144. In contrast, there were also some controversial developments. Part of the rocky Hallett Cove on Gulf St Vincent in Adelaide's southern suburbs was developed for housing, as were vineyards in Morphettville

Morphettville is a suburb of Adelaide, South Australia in the City of Marion.

The northern part of the suburb is bounded by the Glenelg tram line, and fully occupied by the Morphettville Racecourse (horseracing track). The tram barn storage an ...

, Tea Tree Gully, Modbury, and Reynella.Whitelock, p. 152. This attracted criticism, as Dunstan was prominent in promoting South Australian viticulture and enotourism.Whitelock, p. 153.

In pursuit of economic links with the nations of South-East Asia

Southeast Asia, also spelled South East Asia and South-East Asia, and also known as Southeastern Asia, South-eastern Asia or SEA, is the geographical south-eastern region of Asia, consisting of the regions that are situated south of mainland ...

, Dunstan came into contact with the leaders of the Malaysia

Malaysia ( ; ) is a country in Southeast Asia. The federal constitutional monarchy consists of thirteen states and three federal territories, separated by the South China Sea into two regions: Peninsular Malaysia and Borneo's East Mal ...

n state of Penang

Penang ( ms, Pulau Pinang, is a Malaysian state located on the northwest coast of Peninsular Malaysia, by the Malacca Strait. It has two parts: Penang Island, where the capital city, George Town, is located, and Seberang Perai on the M ...

in 1973. Striking a note with Chong Eu Lim, the Chief Minister, Dunstan set about organising cultural and economic engagement between the two states. "Penang Week" was held in Adelaide in July, and in return, "South Australia Week" was held in Penang's capital, George Town. In the same year, the Adelaide Festival Centre

Adelaide Festival Centre, Australia's first multi-purpose arts centre and the home of South Australia's performing arts, was built in the 1970s, designed by Hassell Architects. The Festival Theatre opened in June 1973 with the rest of the centr ...

was openedAustralia's first multifunction performing arts complex.

Over a six-year period, government funding for the arts was increased by a factor of seven and in 1978, the South Australian Film Corporation

South Australian Film Corporation (SAFC) is a South Australian Government statutory corporation established in 1972 to engage in film production and promote the film industry, located in Adelaide, South Australia. The Adelaide Studios are manage ...

commenced work. During Dunstan's time in charge, acclaimed films such as '' Breaker Morant'', '' Picnic at Hanging Rock'' and '' Storm Boy'' were made in the state. Dunstan's support of the arts and fine dining was credited by commentators with attracting artists, craftspeople and writers into the state,Whitelock, p. 146. helping to change its atmosphere.

The Legislative Council, the upper house of Parliament, was, due to its limited electoral roll

An electoral roll (variously called an electoral register, voters roll, poll book or other description) is a compilation that lists persons who are entitled to vote for particular elections in a particular jurisdiction. The list is usually broke ...

, overwhelmingly non-Labor.Jaensch (1986), p. 498. Unlike the Lower House, its members were elected only by voters who met certain property and wealth requirements.Jaensch (1997), p. 38. Combined with the remains of the " Playmander" malapportionment,Jaensch (1997), p. 39. it was difficult for the Labor Party to achieve the representation it wished. The Legislative Council either watered down or outright rejected a considerable amount of Labor legislation; bills to legalise homosexuality, abolish corporal

Corporal is a military rank in use in some form by many militaries and by some police forces or other uniformed organizations. The word is derived from the medieval Italian phrase ("head of a body"). The rank is usually the lowest ranking non- ...

and capital punishment

Capital punishment, also known as the death penalty, is the state-sanctioned practice of deliberately killing a person as a punishment for an actual or supposed crime, usually following an authorized, rule-governed process to conclude that ...

and allow gambling and casinos were rejected.Parkin, p. 307. A referendum had indicated support for Friday night shopping, but Labor legislation was blocked in the upper house by the LCL.Parkin, p. 8.

Dunstan called an election for March 1973, hoping to gain a mandate to seek changes to the council. The LCL were badly disunited; the more liberal wing of the party under Hall joined Dunstan in wanting to introduce universal suffrage for the upper house, while the more conservative members of the LCL did not. The conservatives then decided to limit Hall's powers, resulting in his resignation and creation of the breakaway Liberal Movement (LM), which overtly branded itself as a semi-autonomous component within the LCL. Labor capitalised on the opposition divisions to secure an easy victory. They campaigned under the slogan "South Australia's Doing Well with Labor", while the LCL was hampered by infighting; many LCL candidates were claiming different leaders in their electoral material depending on their factional allegiance.Parkin, p. 9. The Labor Party won with 51.5% of the primary vote and secured a second consecutive majority government with 26 seats. It was only the second time a Labor government in South Australia had been re-elected for a second term, the first being the early Thomas Price Labor government. It would be the first five-year-incumbent Labor government however. They also gained two more seats in the Legislative Council to have six of the twenty members.Parkin, p. 10. Labor entered the new term with momentum when a fortnight after the election, the LCL purged LM members from its ranks, forcing them to either quit the LM or leave the LCL and join the LM as a distinct party.

Dunstan saw reform of the Legislative Council as an important goal, and later a prime achievement, of his Government. Labor, as a matter of party policy, wanted to see the Legislative Council abolished. Dunstan, seeing this as unfeasible in his term, set about to reform it instead. Two bills were prepared for Legislative Council reform; one to lower the voting age to 18 and introduce

Dunstan called an election for March 1973, hoping to gain a mandate to seek changes to the council. The LCL were badly disunited; the more liberal wing of the party under Hall joined Dunstan in wanting to introduce universal suffrage for the upper house, while the more conservative members of the LCL did not. The conservatives then decided to limit Hall's powers, resulting in his resignation and creation of the breakaway Liberal Movement (LM), which overtly branded itself as a semi-autonomous component within the LCL. Labor capitalised on the opposition divisions to secure an easy victory. They campaigned under the slogan "South Australia's Doing Well with Labor", while the LCL was hampered by infighting; many LCL candidates were claiming different leaders in their electoral material depending on their factional allegiance.Parkin, p. 9. The Labor Party won with 51.5% of the primary vote and secured a second consecutive majority government with 26 seats. It was only the second time a Labor government in South Australia had been re-elected for a second term, the first being the early Thomas Price Labor government. It would be the first five-year-incumbent Labor government however. They also gained two more seats in the Legislative Council to have six of the twenty members.Parkin, p. 10. Labor entered the new term with momentum when a fortnight after the election, the LCL purged LM members from its ranks, forcing them to either quit the LM or leave the LCL and join the LM as a distinct party.

Dunstan saw reform of the Legislative Council as an important goal, and later a prime achievement, of his Government. Labor, as a matter of party policy, wanted to see the Legislative Council abolished. Dunstan, seeing this as unfeasible in his term, set about to reform it instead. Two bills were prepared for Legislative Council reform; one to lower the voting age to 18 and introduce universal suffrage

Universal suffrage (also called universal franchise, general suffrage, and common suffrage of the common man) gives the right to vote to all adult citizens, regardless of wealth, income, gender, social status, race, ethnicity, or political sta ...

, and another to make councillors elected from a single statewide electorate under a system of proportional representation

Proportional representation (PR) refers to a type of electoral system under which subgroups of an electorate are reflected proportionately in the elected body. The concept applies mainly to geographical (e.g. states, regions) and political divis ...

. The LCL initially blocked both bills, stating that it would accept them only if modifications were made to the second one. Changes were conceded; unlike the House of Assembly, voting would not be compulsory and the preference system was to be slightly altered. Once the amendments were made, the legislation was passed.

During his second term, Dunstan started efforts to build a petrochemical complex at Redcliff, near Port Augusta

Port Augusta is a small city in South Australia. Formerly a seaport, it is now a road traffic and railway junction city mainly located on the east coast of the Spencer Gulf immediately south of the gulf's head and about north of the state c ...

. Negotiations were held with several multinational companies, but nothing eventuated. Legislation was passed to create a Land Commission and introduce urban land price controls. However, a bill to create "a right to privacy" was defeated in the upper house after protests from journalists, as was legislation to mandate refunds to consumers for returning beverage containers and therefore promote recycling. In 1975, Dunstan declared Australia's first legal nude bathing reserve.

Prior to the 1975 federal and state

State may refer to:

Arts, entertainment, and media Literature

* ''State Magazine'', a monthly magazine published by the U.S. Department of State

* ''The State'' (newspaper), a daily newspaper in Columbia, South Carolina, United States

* ''Our S ...

elections, Australia, and South Australia in particular, had been hit by a series of economic problems. The 1973 oil crisis

The 1973 oil crisis or first oil crisis began in October 1973 when the members of the Organization of Arab Petroleum Exporting Countries (OAPEC), led by Saudi Arabia, proclaimed an oil embargo. The embargo was targeted at nations that had su ...