Dominion of India on:

[Wikipedia]

[Google]

[Amazon]

The Dominion of India, officially the Union of India,* Quote: “The first collective use (of the word "dominion") occurred at the Colonial Conference (April to May 1907) when the title was conferred upon Canada and Australia. New Zealand and Newfoundland were afforded the designation in September of that same year, followed by South Africa in 1910. These were the only British possessions recognized as Dominions at the outbreak of war. In 1922, the Irish Free State was given Dominion status, followed by the short-lived inclusion of India and Pakistan in 1947 (although India was officially recognized as the Union of India). The Union of India became the Republic of India in 1950, while the became the Islamic Republic of Pakistan in 1956.” was an independent

In the 1945 general elections in Britain, Labour Party won. A government headed by

In the 1945 general elections in Britain, Labour Party won. A government headed by

As independence approached, the violence between Hindus and Muslims in the provinces of Punjab and Bengal continued. With the British Army unprepared for the potential for increased violence, the new viceroy,

As independence approached, the violence between Hindus and Muslims in the provinces of Punjab and Bengal continued. With the British Army unprepared for the potential for increased violence, the new viceroy,

The

The

The religious killings had abated by the Autumn of 1947, but the government was weighed down with the responsibility of settling the refugees. In the Punjab, there was land available recently vacated by the Muslims; in Delhi, there was a glut of incoming Hindu and Sikh refugees: many more were arriving there than were Muslims departing for Pakistan. The refugees were settled in several enclosed areas on the outskirts of Delhi. But they had soon overflowed into the streets and even occupied mosques. They attempted to take possession the Purana Qila, or ''Old Fort''—ruins from the

The religious killings had abated by the Autumn of 1947, but the government was weighed down with the responsibility of settling the refugees. In the Punjab, there was land available recently vacated by the Muslims; in Delhi, there was a glut of incoming Hindu and Sikh refugees: many more were arriving there than were Muslims departing for Pakistan. The refugees were settled in several enclosed areas on the outskirts of Delhi. But they had soon overflowed into the streets and even occupied mosques. They attempted to take possession the Purana Qila, or ''Old Fort''—ruins from the

The

The

Some Indians were incensed by Gandhi's last fast and accused him of being too accommodating to both Muslims and Pakistan. Among them was Nathuram Godse, a Hindu nationalist, a member of the political party

Some Indians were incensed by Gandhi's last fast and accused him of being too accommodating to both Muslims and Pakistan. Among them was Nathuram Godse, a Hindu nationalist, a member of the political party

Two matters had been left unsettled from the Raj years: the integration of the princely states and the drawing up of a constitution and were addressed in that order.

There were 362 princely states in India. The premier 21-gun salute state of Hyderabad had an area of . Its population was 17 million. At the other end of the spectrum, some two hundred states had an area of less than . The British had revoked their treaty rights and advised them to join in a political union with India or Pakistan. For a short time, the

Two matters had been left unsettled from the Raj years: the integration of the princely states and the drawing up of a constitution and were addressed in that order.

There were 362 princely states in India. The premier 21-gun salute state of Hyderabad had an area of . Its population was 17 million. At the other end of the spectrum, some two hundred states had an area of less than . The British had revoked their treaty rights and advised them to join in a political union with India or Pakistan. For a short time, the

The final achievement of the period of transition was the new constitution. It was drafted by the Constituent Assembly with uncommon speed and absence of irregularities between 1946 and 1949. The

The final achievement of the period of transition was the new constitution. It was drafted by the Constituent Assembly with uncommon speed and absence of irregularities between 1946 and 1949. The

"India After Gandhi"

Picador India, 2007. Nehru's cabinet of 15 included one woman.

File:Brit IndianEmpireReligions3.jpg, India: the prevailing religions, 1909,

The majority of the population movement associated with the Partition occurred in the period immediately before and after August 1947. Although many people did die in the religious violence, many also perished for reasons only indirectly related to violence. According to historical demographer

The two main concerns of the new Indian government in 1947 were the economic foundations of the country and the poverty of a large segment of its population. Although the British Raj had also been concerned about poverty, its basic justification and the scale of the problem meant that it expended resources on poverty alleviation only when the distress seemed to be threatening civic order. The new government apprehended clearly that a low level of income and therefore also of demand and prospective investment considerably slowed down development in all areas of the economy, including agriculture, industry, and the service sector.

A National Income Committee was set up in 1949 to measure Indian poverty; its report published in 1950/1951 computed the average annual income per person in India to be Rs. 260 or $55. Some Indians earned less, especially among those who worked as domestic help, tenant farmers, or agricultural labourers.

According to historian

The two main concerns of the new Indian government in 1947 were the economic foundations of the country and the poverty of a large segment of its population. Although the British Raj had also been concerned about poverty, its basic justification and the scale of the problem meant that it expended resources on poverty alleviation only when the distress seemed to be threatening civic order. The new government apprehended clearly that a low level of income and therefore also of demand and prospective investment considerably slowed down development in all areas of the economy, including agriculture, industry, and the service sector.

A National Income Committee was set up in 1949 to measure Indian poverty; its report published in 1950/1951 computed the average annual income per person in India to be Rs. 260 or $55. Some Indians earned less, especially among those who worked as domestic help, tenant farmers, or agricultural labourers.

According to historian  India did have a firmly founded

India did have a firmly founded  Similarly, despite Gandhi's anti-untouchability campaigns of the 1930s, the vast majority of Untouchables remained in a state of ritual pollution and self-abasing poverty—land ownership, education, or skilled work was out of reach. According to Judith M. Brown, "The new government recognised the burden of its inheritance in these areas of society and the 1950 constitution stated its commitment to fundamental change and a denial of Hindu conventions which an alien government had not dared to initiate." Although Untouchability was abolished in the new constitution, it was soon evident that the yoke of culture bore down so oppressively on Untouchables, that more legislation, administrative reform, and economic change were needed for them to assume their constitutional rights; the same was true of women. However, in urban areas, economic changes in the 1940s had demonstrated that belief and ritual status in Hinduism had hindered neither industrialisation, nor workers responding quickly to market forces, and changing occupations or locations of work.

Similarly, despite Gandhi's anti-untouchability campaigns of the 1930s, the vast majority of Untouchables remained in a state of ritual pollution and self-abasing poverty—land ownership, education, or skilled work was out of reach. According to Judith M. Brown, "The new government recognised the burden of its inheritance in these areas of society and the 1950 constitution stated its commitment to fundamental change and a denial of Hindu conventions which an alien government had not dared to initiate." Although Untouchability was abolished in the new constitution, it was soon evident that the yoke of culture bore down so oppressively on Untouchables, that more legislation, administrative reform, and economic change were needed for them to assume their constitutional rights; the same was true of women. However, in urban areas, economic changes in the 1940s had demonstrated that belief and ritual status in Hinduism had hindered neither industrialisation, nor workers responding quickly to market forces, and changing occupations or locations of work.

File:Emergency trains crowded with desperate refugees.jpg, Emergency trains crowded with desperate refugees

File:Dr. Babasaheb Ambedkar, chairman of the Drafting Committee, presenting the final draft of the Indian Constitution to Dr. Rajendra Prasad on 25 November, 1949.jpg, B. R. Ambedkar, presenting the final draft of the

dominion

The term ''Dominion'' is used to refer to one of several self-governing nations of the British Empire.

"Dominion status" was first accorded to Canada, Australia, New Zealand, Newfoundland, South Africa, and the Irish Free State at the 1926 ...

in the British Commonwealth of Nations

The Commonwealth of Nations, simply referred to as the Commonwealth, is a political association of 56 member states, the vast majority of which are former territories of the British Empire. The chief institutions of the organisation are the C ...

existing between 15 August 1947 and 26 January 1950. Until its independence, India had been ruled as an informal empire by the United Kingdom. The empire, also called the British Raj

The British Raj (; from Hindi ''rāj'': kingdom, realm, state, or empire) was the rule of the British Crown on the Indian subcontinent;

*

* it is also called Crown rule in India,

*

*

*

*

or Direct rule in India,

* Quote: "Mill, who was him ...

and sometimes the British Indian Empire

The British Raj (; from Hindi ''rāj'': kingdom, realm, state, or empire) was the rule of the British Crown on the Indian subcontinent;

*

* it is also called Crown rule in India,

*

*

*

*

or Direct rule in India,

* Quote: "Mill, who was himse ...

, consisted of regions, collectively called British India

The provinces of India, earlier presidencies of British India and still earlier, presidency towns, were the administrative divisions of British governance on the Indian subcontinent. Collectively, they have been called British India. In one ...

, that were directly administered by the British government, and regions, called the princely state

A princely state (also called native state or Indian state) was a nominally sovereign entity of the British Indian Empire that was not directly governed by the British, but rather by an Indian ruler under a form of indirect rule, subject to ...

s, that were ruled by Indian rulers under a system of paramountcy. The Dominion of India was formalised by the passage of the Indian Independence Act 1947

The Indian Independence Act 1947 947 CHAPTER 30 10 and 11 Geo 6is an Act of the Parliament of the United Kingdom that partitioned British India into the two new independent dominions of India and Pakistan. The Act received Royal Assent on 18 Ju ...

, which also formalised an independent Dominion of Pakistan

Between 14 August 1947 and 23 March 1956, Pakistan was an independent federal dominion in the Commonwealth of Nations, created by the passing of the Indian Independence Act 1947 by the British parliament, which also created the Dominion of ...

—comprising the regions of British India that are today Pakistan

Pakistan ( ur, ), officially the Islamic Republic of Pakistan ( ur, , label=none), is a country in South Asia. It is the world's List of countries and dependencies by population, fifth-most populous country, with a population of almost 24 ...

and Bangladesh

Bangladesh (}, ), officially the People's Republic of Bangladesh, is a country in South Asia. It is the eighth-most populous country in the world, with a population exceeding 165 million people in an area of . Bangladesh is among the mo ...

. The Dominion of India remained "India" in common parlance but was geographically reduced. Under the Act, the British government relinquished all responsibility for administering its former territories. The government also revoked its treaty rights with the rulers of the princely states and advised them to join in a political union with India or Pakistan. Accordingly, the British monarch's regnal title, "Emperor of India

Emperor or Empress of India was a title used by British monarchs from 1 May 1876 (with the Royal Titles Act 1876) to 22 June 1948, that was used to signify their rule over British India, as its imperial head of state. Royal Proclamation of 2 ...

," was abandoned.

The Dominion of India came into existence on the partition of India

The Partition of British India in 1947 was the change of political borders and the division of other assets that accompanied the dissolution of the British Raj in South Asia and the creation of two independent dominions: India and Pakistan. T ...

and was beset by religious violence. Its creation had been preceded by a pioneering and influential anti-colonial nationalist movement which became a major factor in ending the British Raj. A new government was formed led by Jawaharlal Nehru

Pandit Jawaharlal Nehru (; ; ; 14 November 1889 – 27 May 1964) was an Indian Anti-colonial nationalism, anti-colonial nationalist, secular humanist, social democrat—

*

*

*

* and author who was a central figure in India du ...

as prime minister, and Vallabhbhai Patel

Vallabhbhai Jhaverbhai Patel (; ; 31 October 1875 – 15 December 1950), commonly known as Sardar, was an Indian lawyer, influential political leader, barrister and statesman who served as the first Deputy Prime Minister and Home Minister of I ...

as deputy prime minister, both members of the Indian National Congress

The Indian National Congress (INC), colloquially the Congress Party but often simply the Congress, is a political party in India with widespread roots. Founded in 1885, it was the first modern nationalist movement to emerge in the British E ...

. Lord Mountbatten

Louis Francis Albert Victor Nicholas Mountbatten, 1st Earl Mountbatten of Burma (25 June 1900 – 27 August 1979) was a British naval officer, colonial administrator and close relative of the British royal family. Mountbatten, who was of German ...

, the last Viceroy, stayed on until June 1948 as independent India's first governor-general.

The religious violence was soon stemmed in good part by the efforts of Mahatma Gandhi

Mohandas Karamchand Gandhi (; ; 2 October 1869 – 30 January 1948), popularly known as Mahatma Gandhi, was an Indian lawyer, anti-colonial nationalist Quote: "... marks Gandhi as a hybrid cosmopolitan figure who transformed ... anti- ...

, but not before resentment of him grew among some Hindus, eventually costing him his life. To Patel fell the responsibility for integrating the princely states

A princely state (also called native state or Indian state) was a nominally sovereign entity of the British Indian Empire that was not directly governed by the British, but rather by an Indian ruler under a form of indirect rule, subject to ...

of the British Indian Empire into the new India. Lasting through the remainder of 1947 and the better part of 1948, integration was accomplished by the means of inducements, and on occasion threats. It went smoothly except in the instances of Junagadh State

Junagarh or Junagadh ( ur, ) was a princely state in Gujarat ruled by the Muslim Babi dynasty in British India, until its integration into the Union of India in 1948.

History

Muhammad Sher Khan Babai was the founder of the Babi Pashtun d ...

, Hyderabad State

Hyderabad State () was a princely state located in the south-central Deccan region of India with its capital at the city of Hyderabad. It is now divided into the present-day state of Telangana, the Kalyana-Karnataka region of Karnataka, and ...

, and, especially, Kashmir and Jammu, the last leading to a war between India and Pakistan and to a dispute that has lasted until today. During this time, the new constitution of the Republic of India was drafted. It was based in large part on the Government of India Act, 1935

The Government of India Act, 1935 was an Act adapted from the Parliament of the United Kingdom. It originally received royal assent in August 1935. It was the longest Act of (British) Parliament ever enacted until the Greater London Authorit ...

, the last constitution of British India

The provinces of India, earlier presidencies of British India and still earlier, presidency towns, were the administrative divisions of British governance on the Indian subcontinent. Collectively, they have been called British India. In one ...

, but also reflected some elements in the Constitution of the United States

The Constitution of the United States is the supreme law of the United States of America. It superseded the Articles of Confederation, the nation's first constitution, in 1789. Originally comprising seven articles, it delineates the nati ...

and the Constitution of Ireland

The Constitution of Ireland ( ga, Bunreacht na hÉireann, ) is the fundamental law of Ireland. It asserts the national sovereignty of the Irish people. The constitution, based on a system of representative democracy, is broadly within the traditi ...

. The new constitution disavowed some aspects of India's ages-old past by abolishing untouchability

Untouchability is a form of social institution that legitimises and enforces practices that are discriminatory, humiliating, exclusionary and exploitative against people belonging to certain social groups. Although comparable forms of discrimin ...

and derecognising caste

Caste is a form of social stratification characterised by endogamy, hereditary transmission of a style of life which often includes an occupation, ritual status in a hierarchy, and customary social interaction and exclusion based on cultur ...

distinctions.

A major effort was made during this period to document the demographic changes accompanying the partition of British India. According to most demographers, between 14 and 18 million people moved between India and Pakistan as refugees of the partition, and upwards of one million people were killed. A major effort was also made to document the poverty prevalent in India. A committee appointed by the government in 1949, estimated the average annual income of an Indian to be Rs. 260 (or $55), with many earning well below that amount. The government faced low levels of literacy among its population, soon to be estimated at 23.54% for men and 7.62% for women in the 1951 Census of India

The 1951 Census of India was the ninth in a series of censuses held in India every decade since 1872. It is also the first census after independence and Partition of India. 1951 census was also the first census to be conducted under 1948 Census ...

. The government also began plans to improve the status of women. It bore fruit eventually in the passage of the Hindu code bills

The Hindu code bills were several laws passed in the 1950s that aimed to codify and reform Hindu personal law in India, abolishing religious law in favor of a common law code. Following India's independence in 1947, the Indian National Congress g ...

of the mid-1950s, which outlawed patrilineality

Patrilineality, also known as the male line, the spear side or agnatic kinship, is a common kinship system in which an individual's family membership derives from and is recorded through their father's lineage. It generally involves the inheritan ...

, marital desertion and child marriages

Child marriage is a marriage or similar union, formal or informal, between a child under a certain age – typically 18 years – and an adult or another child.

*

*

*

* The vast majority of child marriages are between a female child and a ma ...

, though evasion of the law continued for years thereafter. The Dominion of India lasted until 1950, whereupon India became a republic within the Commonwealth

A republic () is a "state in which power rests with the people or their representatives; specifically a state without a monarchy" and also a "government, or system of government, of such a state." Previously, especially in the 17th and 18th c ...

with a president

President most commonly refers to:

*President (corporate title)

* President (education), a leader of a college or university

* President (government title)

President may also refer to:

Automobiles

* Nissan President, a 1966–2010 Japanese ...

as head of state

A head of state (or chief of state) is the public persona who officially embodies a state Foakes, pp. 110–11 " he head of statebeing an embodiment of the State itself or representatitve of its international persona." in its unity and ...

.

History

Background: 1946

By the early 1920s, theIndian National Congress

The Indian National Congress (INC), colloquially the Congress Party but often simply the Congress, is a political party in India with widespread roots. Founded in 1885, it was the first modern nationalist movement to emerge in the British E ...

had become the principal leader of Indian nationalism

Indian nationalism is an instance of territorial nationalism, which is inclusive of all of the people of India, despite their diverse ethnic, linguistic and religious backgrounds. Indian nationalism can trace roots to pre-colonial India, ...

. Led by Mahatma Gandhi

Mohandas Karamchand Gandhi (; ; 2 October 1869 – 30 January 1948), popularly known as Mahatma Gandhi, was an Indian lawyer, anti-colonial nationalist Quote: "... marks Gandhi as a hybrid cosmopolitan figure who transformed ... anti- ...

, the Congress was to lead India to independence from the United Kingdom

The United Kingdom of Great Britain and Northern Ireland, commonly known as the United Kingdom (UK) or Britain, is a country in Europe, off the north-western coast of the continental mainland. It comprises England, Scotland, Wales and ...

, and powerfully influence other anti-colonial nationalist movements in the British Empire

The British Empire was composed of the dominions, colonies, protectorates, mandates, and other territories ruled or administered by the United Kingdom and its predecessor states. It began with the overseas possessions and trading posts e ...

. The Congress's vision of an independent India based on religious pluralism

Religious pluralism is an attitude or policy regarding the diversity of religious belief systems co-existing in society. It can indicate one or more of the following:

* Recognizing and tolerating the religious diversity of a society or coun ...

was challenged in the early 1940s by a new Muslim nationalism, led by the All-India Muslim League

The All-India Muslim League (AIML) was a political party established in Dhaka in 1906 when a group of prominent Muslim politicians met the Viceroy of British India, Lord Minto, with the goal of securing Muslim interests on the Indian subcont ...

and Muhammad Ali Jinnah

Muhammad Ali Jinnah (, ; born Mahomedali Jinnahbhai; 25 December 1876 – 11 September 1948) was a barrister, politician, and the founder of Pakistan. Jinnah served as the leader of the All-India Muslim League from 1913 until the ...

, which demanded a separate homeland for the Muslims of British India. Quote: "the Muslim League had only caught on among South Asian Muslims during the Second World War. ... By the late 1940s, the League and the Congress had impressed in the British their own visions of a free future for Indian people. ... one, articulated by the Congress, rested on the idea of a united, plural India as a home for all Indians and the other, spelt out by the League, rested on the foundation of Muslim nationalism and the carving out of a separate Muslim homeland." (p. 18)

In the 1945 general elections in Britain, Labour Party won. A government headed by

In the 1945 general elections in Britain, Labour Party won. A government headed by Clement Attlee

Clement Richard Attlee, 1st Earl Attlee, (3 January 18838 October 1967) was a British politician who served as Prime Minister of the United Kingdom from 1945 to 1951 and Leader of the Labour Party from 1935 to 1955. He was Deputy Prime Mini ...

, with Stafford Cripps

Sir Richard Stafford Cripps (24 April 1889 – 21 April 1952) was a British Labour Party politician, barrister, and diplomat.

A wealthy lawyer by background, he first entered Parliament at a by-election in 1931, and was one of a handful of La ...

and Lord Pethick-Lawrence in the Cabinet, was sworn in. Many in the new government, including Attlee, had a long history of supporting the decolonization of India. Late in 1946, the Labour government, its exchequer, and population, moreover, exhausted by the Second World War, decided to end British rule in India, and in early 1947 Britain announced its intention of transferring power no later than June 1948.

Earlier in 1946, elections had been called in India. The Congress had won electoral victories in eight of the eleven provinces. The negotiations between the Congress and the Muslim League, however, stalled over the issue of a division of India. Jinnah proclaimed 16 August 1946 "Direct Action Day

Direct Action Day (16 August 1946), also known as the 1946 Calcutta Killings, was a day of nationwide communal riots. It led to large-scale violence between Muslims and Hindus in the city of Calcutta (now known as Kolkata) in the Bengal pro ...

" with the stated goal of peacefully highlighting the demand for a Muslim homeland in British India. The following day Hindu-Muslim riots broke out in Calcutta and quickly spread throughout India. Although the Government of India and the Congress were both shaken by the course of events, a Congress-led interim government was installed in September, with Jawaharlal Nehru as united India's prime minister.

Independence: 1947

As independence approached, the violence between Hindus and Muslims in the provinces of Punjab and Bengal continued. With the British Army unprepared for the potential for increased violence, the new viceroy,

As independence approached, the violence between Hindus and Muslims in the provinces of Punjab and Bengal continued. With the British Army unprepared for the potential for increased violence, the new viceroy, Louis Mountbatten

Louis Francis Albert Victor Nicholas Mountbatten, 1st Earl Mountbatten of Burma (25 June 1900 – 27 August 1979) was a British naval officer, colonial administrator and close relative of the British royal family. Mountbatten, who was of German ...

, advanced the date for the transfer of power, allowing less than six months for a mutually agreed plan for independence. In June 1947 the nationalist leaders, including Nehru and Abul Kalam Azad

Abul Kalam Ghulam Muhiyuddin Ahmed bin Khairuddin Al-Hussaini Azad (; 11 November 1888 – 22 February 1958) was an Indian independence activist, Islamic theologian, writer and a senior leader of the Indian National Congress. Following In ...

on behalf of the Congress, Jinnah representing the Muslim League, B. R. Ambedkar representing the Untouchable

Untouchable or The Untouchable may refer to:

People

* Untouchability, the practice of socially ostracizing a minority group of very low social status

** A word for the Dalits or Scheduled Caste of India, a group that experiences untouchability

* ...

community, and Master Tara Singh representing the Sikhs

Sikhs ( or ; pa, ਸਿੱਖ, ' ) are people who adhere to Sikhism (Sikhi), a monotheistic religion that originated in the late 15th century in the Punjab region of the Indian subcontinent, based on the revelation of Guru Nanak. The ter ...

, agreed to a partition of the country along religious lines in opposition to Gandhi's views. The predominantly Hindu and Sikh areas were assigned to the new India and predominantly Muslim areas to the new nation of Pakistan

Pakistan ( ur, ), officially the Islamic Republic of Pakistan ( ur, , label=none), is a country in South Asia. It is the world's List of countries and dependencies by population, fifth-most populous country, with a population of almost 24 ...

; the plan included a partition of the Muslim-majority provinces of Punjab and Bengal.

On 14 August 1947, the new Dominion of Pakistan

Between 14 August 1947 and 23 March 1956, Pakistan was an independent federal dominion in the Commonwealth of Nations, created by the passing of the Indian Independence Act 1947 by the British parliament, which also created the Dominion of ...

came into being, with Muhammad Ali Jinnah sworn in as its first Governor-General in Karachi

Karachi (; ur, ; ; ) is the most populous city in Pakistan and 12th most populous city in the world, with a population of over 20 million. It is situated at the southern tip of the country along the Arabian Sea coast. It is the former c ...

. The following day, 15 August 1947, the Dominion of India (officially the ''Union of India''), became an independent country with official ceremonies taking place in New Delhi

New Delhi (, , ''Naī Dillī'') is the capital of India and a part of the National Capital Territory of Delhi (NCT). New Delhi is the seat of all three branches of the government of India, hosting the Rashtrapati Bhavan, Parliament Hous ...

, and with Jawaharlal Nehru assuming the office of the prime minister

A prime minister, premier or chief of cabinet is the head of the cabinet and the leader of the ministers in the executive branch of government, often in a parliamentary or semi-presidential system. Under those systems, a prime minister is ...

, and the viceroy, Louis Mountbatten, staying on as its first Governor General

Governor-general (plural ''governors-general''), or governor general (plural ''governors general''), is the title of an office-holder. In the context of governors-general and former British colonies, governors-general are appointed as viceroy ...

.

Mountbatten's decision to hasten the transfer of power has received both praise and criticism over the years. Supporters feel that an early transfer had the effect of forcing Indian politicians into abandoning petty quarrels and accepting their obligations in stopping an outrage that Great Britain was no longer able to control. Critics feel that if the British had stayed on for another year, had institutions in place for a transition, had the army readied in troublesome areas, a less violent transfer might have resulted.

Partition: 1947

The

The Radcliffe Commission

Radcliffe or Radcliff may refer to:

Places

* Radcliffe Line, a border between India and Pakistan

United Kingdom

* Radcliffe, Greater Manchester

** Radcliffe Tower, the remains of a medieval manor house in the town

** Radcliffe tram stop

* R ...

, tasked with assigning each district to either Pakistan or India, announced its award on 17 August 1947, two days after the transfer of power. It divided the Sikh-dominated regions of the Punjab

Punjab (; Punjabi Language, Punjabi: پنجاب ; ਪੰਜਾਬ ; ; also Romanization, romanised as ''Panjāb'' or ''Panj-Āb'') is a geopolitical, cultural, and historical region in South Asia, specifically in the northern part of the I ...

in equal proportion between the two dominions. Sikh groups, which had feared the worst, had been preparing to mount a vigorous opposition to the award. To counter the expected violence, the British Raj government had formed a 50,000-strong ''Indian Boundary Force''. When the violence began, the Force proved ineffectual. Most units, which had been recruited locally, had stronger ties to one or other of Punjab's three religious' groups, rendering them unable to maintain neutrality under stress. In a matter of days, Sikhs and Hindus of the East Punjab were suddenly and unexpectedly attacking the Muslims there, and in the West Punjab, Muslims were returning the violence and the ferocity on the Sikhs. Trains taking the refugees to their new lands were stopped, their occupants slaughtered regardless of age and gender. Long lines of humans and oxcarts travelling East and West to their new dominions were intercepted and overwhelmed.

The Hindu refugees from the west Punjab arriving in Delhi ended up tearing away the Muslim community there from their established cultural patterns and values, and temporarily destabilized the new government. The death toll in the partition violence may never be known, but Judge G. D. Khosla, in ''Stern Reckoning'' thought it to be about 500,000. In addition, there was what historian Percival Spear

Thomas George Percival Spear (1901–1982) was a British historian of modern South Asia, in particular of its colonial period. He taught at both Cambridge University and St. Stephen's College, Delhi.

Personal life and education

Born in B ...

has called "an involuntary exchange of population," which might be of the order of five and a half million travelling each way across the new border. From Sind, some 400,000 Hindus migrated to India, as did a million Hindus from East Pakistan (now Bangladesh) to West Bengal province in India. Migrations coming in the wake of the massacres severely taxed the strength of the new government.

Settling the refugees

The religious killings had abated by the Autumn of 1947, but the government was weighed down with the responsibility of settling the refugees. In the Punjab, there was land available recently vacated by the Muslims; in Delhi, there was a glut of incoming Hindu and Sikh refugees: many more were arriving there than were Muslims departing for Pakistan. The refugees were settled in several enclosed areas on the outskirts of Delhi. But they had soon overflowed into the streets and even occupied mosques. They attempted to take possession the Purana Qila, or ''Old Fort''—ruins from the

The religious killings had abated by the Autumn of 1947, but the government was weighed down with the responsibility of settling the refugees. In the Punjab, there was land available recently vacated by the Muslims; in Delhi, there was a glut of incoming Hindu and Sikh refugees: many more were arriving there than were Muslims departing for Pakistan. The refugees were settled in several enclosed areas on the outskirts of Delhi. But they had soon overflowed into the streets and even occupied mosques. They attempted to take possession the Purana Qila, or ''Old Fort''—ruins from the Delhi Sultanate

The Delhi Sultanate was an Islamic empire based in Delhi that stretched over large parts of the Indian subcontinent for 320 years (1206–1526).

—which were milling with Muslims waiting to be expatriated to Pakistan. Religious passions were running high; a pogrom

A pogrom () is a violent riot incited with the aim of massacring or expelling an ethnic or religious group, particularly Jews. The term entered the English language from Russian to describe 19th- and 20th-century attacks on Jews in the Russian ...

of the remaining Muslims in Delhi was feared.

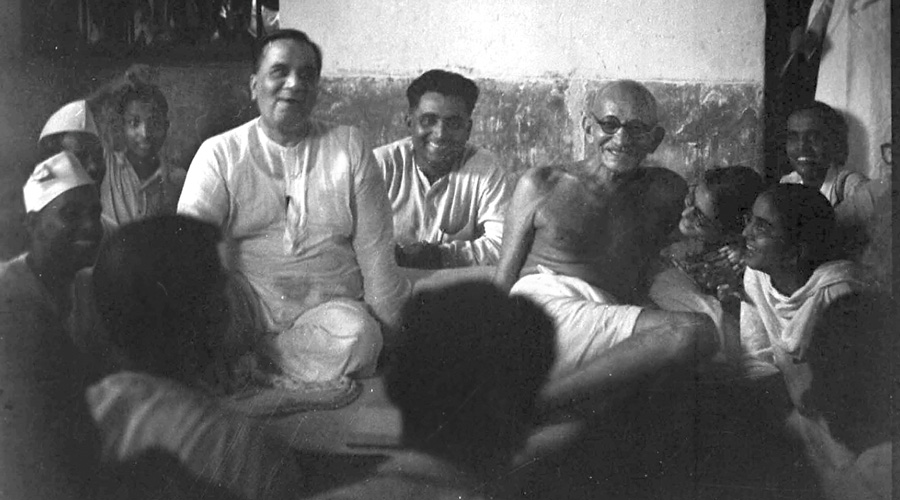

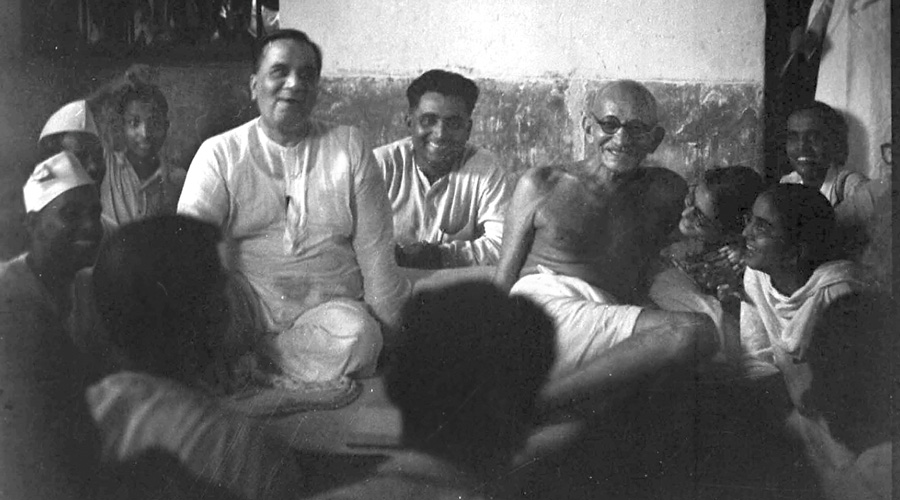

His mission of quelling the violence in Bengal accomplished, Mahatma Gandhi arrived in Delhi in October 1947. His new mission was to bring back the peace in the city, and this entailed standing up for the embattled Muslims. He chose to direct his activities from the scheduled caste

The Scheduled Castes (SCs) and Scheduled Tribes (STs) are officially designated groups of people and among the most disadvantaged socio-economic groups in India. The terms are recognized in the Constitution of India and the groups are designa ...

(or "untouchables') "Balmiki Temple" in the Gole Market

Gole Market is a neighborhood in the heart of New Delhi, India built within a traffic roundabout by Edwin Lutyens in 1921. It is one of New Delhi's oldest surviving colonial markets and is considered an architecturally significant structure. T ...

area of the city. (Eventually, as the temple was requisitioned for sheltering the incoming refugees, Gandhi moved to two rooms in Birla House Birla may refer to:

* Birla family

* Members of the Birla family:

** Aditya Vikram Birla

** Ananya Birla

** Basant Kumar Birla

** G. D. Birla

** K. K. Birla

** C. K. Birla

** Kumar Mangalam Birla

See also

* Burla (disambiguation)

Burla may refer ...

, a large mansion in central Delhi.) Some groups within the Indian government opposed Gandhi's activities.

Soon another issue sprouted up. The partition of India

The Partition of British India in 1947 was the change of political borders and the division of other assets that accompanied the dissolution of the British Raj in South Asia and the creation of two independent dominions: India and Pakistan. T ...

had not just been a division of the land of British India

The provinces of India, earlier presidencies of British India and still earlier, presidency towns, were the administrative divisions of British governance on the Indian subcontinent. Collectively, they have been called British India. In one ...

; it had also involved a division of its assets. Assets whose amounts had been negotiated earlier needed to be transferred from India (where the treasury was) to Pakistan. The Indian government had withheld this payment in order to pressure Pakistan over the burgeoning crisis in Kashmir

Kashmir () is the northernmost geographical region of the Indian subcontinent. Until the mid-19th century, the term "Kashmir" denoted only the Kashmir Valley between the Great Himalayas and the Pir Panjal Range. Today, the term encompas ...

; India feared an onslaught from Pakistan during the dreaded winter months.

On 12 January 1948, Gandhi, who had turned 78 the previous October went on a hunger strike. The preconditions of its ending were the full payment of the cash assets, the signing of a peace accord in Delhi, and the evacuation of the mosques. Brown (1991), p. 380: "Despite and indeed because of his sense of helplessness Delhi was to be the scene of what he called his greatest fast. ... His decision was made suddenly, though after considerable thought – he gave no hint of it even to Nehru and Patel who were with him shortly before he announced his intention at a prayer-meeting on 12 January 1948. He said he would fast until communal peace was restored, real peace rather than the calm of a dead city imposed by police and troops. Patel and the government took the fast partly as condemnation of their decision to withhold a considerable cash sum still outstanding to Pakistan as a result of the allocation of undivided India's assets because the hostilities that had broken out in Kashmir; ... But even when the government agreed to pay out the cash, Gandhi would not break his fast: that he would only do after a large number of important politicians and leaders of communal bodies agreed to a joint plan for restoration of normal life in the city." When the Government of India relented and agreed to transfer the assets on 18 January 1948, and the peace accord stood signed, Gandhi ended his fast.

War over Kashmir

The

The princely state

A princely state (also called native state or Indian state) was a nominally sovereign entity of the British Indian Empire that was not directly governed by the British, but rather by an Indian ruler under a form of indirect rule, subject to ...

of Kashmir

Kashmir () is the northernmost geographical region of the Indian subcontinent. Until the mid-19th century, the term "Kashmir" denoted only the Kashmir Valley between the Great Himalayas and the Pir Panjal Range. Today, the term encompas ...

was created in 1846, after the defeat of the Sikh empire

The Sikh Empire was a state originating in the Indian subcontinent, formed under the leadership of Maharaja Ranjit Singh, who established an empire based in the Punjab. The empire existed from 1799, when Maharaja Ranjit Singh captured Lahor ...

by the British in the First Anglo-Sikh War

The First Anglo-Sikh War was fought between the Sikh Empire and the British East India Company in 1845 and 1846 in and around the Ferozepur district of Punjab. It resulted in defeat and partial subjugation of the Sikh empire and cession o ...

. Upon the purchase of the region from the British under the Treaty of Amritsar, the Raja of Jammu, Gulab Singh

Gulab Singh Jamwal (1792–1857) was the founder of Dogra dynasty and the first Maharaja of the princely state of Jammu and Kashmir, the largest princely state under the British Raj, which was created after the defeat of the Sikh Empire in t ...

, became the new ruler of Kashmir. The rule of his descendants, under the ''paramountcy'' (or tutelage) of the British Crown

The Crown is the state in all its aspects within the jurisprudence of the Commonwealth realms and their subdivisions (such as the Crown Dependencies, overseas territories, provinces, or states). Legally ill-defined, the term has different ...

, lasted until the Partition of India

The Partition of British India in 1947 was the change of political borders and the division of other assets that accompanied the dissolution of the British Raj in South Asia and the creation of two independent dominions: India and Pakistan. T ...

in 1947. Kashmir was connected to India through the Gurdaspur district in the Punjab region. However, its population was 77% Muslim, and it shared a border with what would later become Pakistan. A significant portion of its economic activity had taken place down the Jhelum River with the Punjab region of Pakistan. Gulab Singh's descendant, Hari Singh

Maharaja Sir Hari Singh (September 1895 – 26 April 1961) was the last ruling Maharaja of the princely state of Jammu and Kashmir.

Hari Singh was the son of Amar Singh and Bhotiali Chib. In 1923, following his uncle's death, Singh became ...

, who was the reigning Maharaja of Kashmir in August 1947, had signed a "standstill agreement" with Pakistan to facilitate trade and communication. According to historian Burton Stein

Burton Stein (1926 – April 26, 1996) was an American historian, whose area of specialization was India.

Life and career

Stein was born and grew up in Chicago, Illinois and served in the Second World War, before commencing tertiary study at the ...

, It was anticipated that he would accede to Pakistan when the British paramountcy ended. When he hesitated to do this, Pakistan launched a guerrilla onslaught meant to frighten its ruler into submission. Instead, the Maharaja appealed to MountbattenViscount Louis Mountbatten, the last Viceroy of British India, stayed on in independent India from 1947 to 1948, serving as the first Governor-General of the Union of India. for assistance, and theIn the last days of 1948, a ceasefire was agreed under UN auspices. However, since thegovernor-general Governor-general (plural ''governors-general''), or governor general (plural ''governors general''), is the title of an office-holder. In the context of governors-general and former British colonies, governors-general are appointed as viceroy t ...agreed on the condition that the ruler accede to India. Indian soldiers entered Kashmir and drove the Pakistani-sponsored irregulars from all but a small section of the state. The United Nations was then invited to mediate the quarrel. The UN mission insisted that the opinion of Kashmiris must be ascertained, while India insisted that no referendum could occur until all of the state had been cleared of irregulars.Stein, Burton. 2010. ''A History of India''. Oxford University Press. 432 pages. . Page 358.

plebiscite

A referendum (plural: referendums or less commonly referenda) is a direct vote by the electorate on a proposal, law, or political issue. This is in contrast to an issue being voted on by a representative. This may result in the adoption of ...

demanded by the UN was never conducted, relations between India and Pakistan soured, and eventually led to two more wars over Kashmir in 1965

Events January–February

* January 14 – The Prime Minister of Northern Ireland and the Taoiseach of the Republic of Ireland meet for the first time in 43 years.

* January 20

** Lyndon B. Johnson is sworn in for a full term ...

and 1999

File:1999 Events Collage.png, From left, clockwise: The funeral procession of King Hussein of Jordan in Amman; the 1999 İzmit earthquake kills over 17,000 people in Turkey; the Columbine High School massacre, one of the first major school shoot ...

.

Death of Gandhi

Some Indians were incensed by Gandhi's last fast and accused him of being too accommodating to both Muslims and Pakistan. Among them was Nathuram Godse, a Hindu nationalist, a member of the political party

Some Indians were incensed by Gandhi's last fast and accused him of being too accommodating to both Muslims and Pakistan. Among them was Nathuram Godse, a Hindu nationalist, a member of the political party Hindu Mahasabha

The Hindu Mahasabha (officially Akhil Bhārat Hindū Mahāsabhā, ) is a Hindu nationalist political party in India.

Founded in 1915, the Mahasabha functioned mainly as a pressure group advocating the interests of orthodox Hindus before the ...

as well as a former member of the Rashtriya Swayamsevak Sangh

The Rashtriya Swayamsevak Sangh ( ; , , ) is an Indian right-wing, Hindu nationalist, paramilitary volunteer organisation. The RSS is the progenitor and leader of a large body of organisations called the Sangh Parivar (Hindi for "Sangh family ...

(RSS), a right-wing Hindu paramilitary volunteer organization. Quote: "The apotheosis of this contrast is the assassination of Gandhi in 1948 by a militant Nathuram Godse, on the basis of his 'weak' accommodationist approach towards the new state of Pakistan." (p. 544) On 30 January 1948, Godse assassinated Gandhi in Birla House as Gandhi was on his way to his evening prayer meeting there, shooting Gandhi in the chest three times.

Later that evening, Nehru addressed the nation by radio:

Friends and comrades, the light has gone out of our lives, and there is darkness everywhere, and I do not quite know what to tell you or how to say it. Our beloved leader, Bapu as we called him, the father of the nation, is no more. Perhaps I am wrong to say that; nevertheless, we will not see him again, as we have seen him for these many years, we will not run to him for advice or seek solace from him, and that is a terrible blow, not only for me, but for millions and millions in this country.Gandhi was mourned around the world. The British prime minister

Clement Attlee

Clement Richard Attlee, 1st Earl Attlee, (3 January 18838 October 1967) was a British politician who served as Prime Minister of the United Kingdom from 1945 to 1951 and Leader of the Labour Party from 1935 to 1955. He was Deputy Prime Mini ...

said in a radio address to the United Kingdom on the night of 30 January 1948:Everyone will have learnt with profound horror of the brutal murder of Mr. Gandhi, and I know that I am expressing the views of the British people in offering to his fellow-countrymen our deep sympathy in the loss of their greatest citizen. Mahatma Gandhi, as he was known in India, was one of the outstanding figures in the world today, ... For a quarter of a century this one man has been the major factor in every consideration of the Indian problem.After the mourning period was over, the finger of blame was firmly pointed at the Hindu extremists who had plotted the assassination, bringing not only them into disrepute, but Hindu nationalism in general, which did not recover its political reputation until many decades later. The Deputy Prime Minister, Sardar Patel, who was also the Home Minister, was reproached for inadequate security arrangements. Gandhi's loss had the effect of giving Nehru more power. According to historian Percival Spear, "The government was really a duumvirate between him (Nehru), who represented the idealism and left-wing tendencies of the party, and Sardar Vallabhbhai Patel, the realist and party boss from Gujarat who leaned to authoritarianism, orthodoxy, and big business." At Gandhi's pressing, Patel had twice put off claiming the prime minister ship. It was thought he might assert his claim now, but Gandhi's loss had affected him equally deeply, and although there was still some discord between him and Nehru, he buried himself resolutely in his work on the integration of the princely states. By the year's end, this was complete. Patel died in 1950, and thereafter, Nehru ruled without any opposition.

Political integration of princely states

Two matters had been left unsettled from the Raj years: the integration of the princely states and the drawing up of a constitution and were addressed in that order.

There were 362 princely states in India. The premier 21-gun salute state of Hyderabad had an area of . Its population was 17 million. At the other end of the spectrum, some two hundred states had an area of less than . The British had revoked their treaty rights and advised them to join in a political union with India or Pakistan. For a short time, the

Two matters had been left unsettled from the Raj years: the integration of the princely states and the drawing up of a constitution and were addressed in that order.

There were 362 princely states in India. The premier 21-gun salute state of Hyderabad had an area of . Its population was 17 million. At the other end of the spectrum, some two hundred states had an area of less than . The British had revoked their treaty rights and advised them to join in a political union with India or Pakistan. For a short time, the Nawab of Bhopal

The Nawabs of Bhopal were the Muslim rulers of Bhopal, now part of Madhya Pradesh, India. The nawabs first ruled under the Mughal Empire from 1707 to 1737, under the Maratha Empire from 1737 to 1818, then under British rule from 1818 to 1947, a ...

and some British political agents attempted to form a third "political force," but the princes were unable to trust each other. By 15 August, all but three had acceded.

Even after accession, there remained the question of deciding the place of the princes in the new political union. Sardar Patel and his assistant V. P. Menon

Rao Bahadur Vappala Pangunni Menon, CSI, CIE (30 September 1893 – 31 December 1965) was an Indian civil servant who served as Secretary to the Government of India in the Ministry of the States, under Sardar Patel.

By appointment fr ...

employed a combination of threats and inducements, the latter including special privileges and tax-free pensions. Within a few months, all the states that had acceded in August 1947 had been blended in some fashion into a new federal union. Baroda State

Baroda State was a state in present-day Gujarat, ruled by the Gaekwad dynasty of the Maratha Confederacy from its formation in 1721 until its accession to the newly formed Dominion of India in 1949. With the city of Baroda (Vadodara) as its ...

and Kathiawar

Kathiawar () is a peninsula, near the far north of India's west coast, of about bordering the Arabian Sea. It is bounded by the Gulf of Kutch in the northwest and by the Gulf of Khambhat (Gulf of Cambay) in the east. In the northeast, i ...

were combined to form the new federal unit of Saurashtra; and the states of Rajputana

Rājputana, meaning "Land of the Rajputs", was a region in the Indian subcontinent that included mainly the present-day Indian state of Rajasthan, as well as parts of Madhya Pradesh and Gujarat, and some adjoining areas of Sindh in modern-day ...

were united to form Rajasthan

Rajasthan (; lit. 'Land of Kings') is a state in northern India. It covers or 10.4 per cent of India's total geographical area. It is the largest Indian state by area and the seventh largest by population. It is on India's northwestern ...

. The princely states of Travancore

The Kingdom of Travancore ( /ˈtrævənkɔːr/), also known as the Kingdom of Thiruvithamkoor, was an Indian kingdom from c. 1729 until 1949. It was ruled by the Travancore Royal Family from Padmanabhapuram, and later Thiruvananthapuram. A ...

and Cochin

Kochi (), also known as Cochin ( ) ( the official name until 1996) is a major port city on the Malabar Coast of India bordering the Laccadive Sea, which is a part of the Arabian Sea. It is part of the district of Ernakulam in the state of ...

became Kerala

Kerala ( ; ) is a state on the Malabar Coast of India. It was formed on 1 November 1956, following the passage of the States Reorganisation Act, by combining Malayalam-speaking regions of the erstwhile regions of Cochin, Malabar, South Ca ...

. Mysore being large in extent and population became a federal unit by itself. Hundreds of small states were absorbed and soon became lost within larger federal units.

Some former princes such as those of Mysore and Travancore were given titular leadership roles, called " Raj Pramukh" (lit. "state leader"), in the new federal units, but their former power was absent, and the political structure was invariantly democratic. Other former princes went into public service or private business. After 1950, they survived as historical vestiges but were no longer political determinants in the new India.

Except for Kashmir, where a major military conflict had begun in October 1947, two states, Hyderabad, and Junagadh had remained independent. Junagadh was a small state on the coast of the Kathiawar peninsula

Kathiawar () is a peninsula, near the far north of India's west coast, of about bordering the Arabian Sea. It is bounded by the Gulf of Kutch in the northwest and by the Gulf of Khambhat (Gulf of Cambay) in the east. In the northeast, it is ...

, but its land border was with India. It had a majority Hindu population but with a Muslim Nawab. The Nawab acceded to Pakistan after independence. Within a few weeks, Indian troops marched into Junagadh. A plebiscite

A referendum (plural: referendums or less commonly referenda) is a direct vote by the electorate on a proposal, law, or political issue. This is in contrast to an issue being voted on by a representative. This may result in the adoption of ...

took place and was declared for India. Although Pakistan protested, it took no further action.

Hyderabad was in a different class. Although it had an 85%-Hindu population, its Muslim rule had begun during the Mughal period

The Mughal Empire was an early-modern empire that controlled much of South Asia between the 16th and 19th centuries. Quote: "Although the first two Timurid emperors and many of their noblemen were recent migrants to the subcontinent, the d ...

. The ruling Nizams had proclaimed themselves to be equal allies of the British rather than subordinates. But the state was landlocked, surrounded on all sides by India. "No Indian government," according to Percival Spear, "could afford to have a block of land so placed independent and perhaps hostile." The Nizam had rejected generous terms for accession brokered by the British. Eventually, when he allowed the power of an extremist organization, the Razakars Razakar (رضا کار) is etymologically an Arabic word which literally means volunteer. The word is also common in Urdu language as a loanword. On the other hand, in Bangladesh, razakar is a pejorative word meaning a traitor or Judas.

In Pakis ...

, to grow within his state, India militarily invaded the state in what was called a "police action," incorporating Hyderabad into its federal structure.

Framing the new constitution

The final achievement of the period of transition was the new constitution. It was drafted by the Constituent Assembly with uncommon speed and absence of irregularities between 1946 and 1949. The

The final achievement of the period of transition was the new constitution. It was drafted by the Constituent Assembly with uncommon speed and absence of irregularities between 1946 and 1949. The Government of India Act, 1935

The Government of India Act, 1935 was an Act adapted from the Parliament of the United Kingdom. It originally received royal assent in August 1935. It was the longest Act of (British) Parliament ever enacted until the Greater London Authorit ...

was used as a model and framework. Long passages from the Act were included. The constitution describes a federal state with a parliamentary system of democracy. The federal structure is conspicuous for the strength of the central government, which has exclusively exercised control of defence, foreign affairs, railways, ports, and currency. The President, the constitutional head of government, has reserve powers for taking over the administration of a state. The central legislature has two houses, the ''Lok Sabha

The Lok Sabha, constitutionally the House of the People, is the lower house of India's bicameral Parliament, with the upper house being the Rajya Sabha. Members of the Lok Sabha are elected by an adult universal suffrage and a first-p ...

'' whose delegates are directly elected by the people in general elections every five years, and the ''Rajya Sabha

The Rajya Sabha, constitutionally the Council of States, is the upper house of the bicameral Parliament of India. , it has a maximum membership of 245, of which 233 are elected by the legislatures of the states and union territories using si ...

'', whose members are nominated by the elected representatives in the states.

There are also features not to be found in the Act of 1935. The definition of fundamental rights is based on the Constitution of the United States

The Constitution of the United States is the supreme law of the United States of America. It superseded the Articles of Confederation, the nation's first constitution, in 1789. Originally comprising seven articles, it delineates the nati ...

, and the constitutional directives, or goals of endeavor, are based on the Constitution of Ireland

The Constitution of Ireland ( ga, Bunreacht na hÉireann, ) is the fundamental law of Ireland. It asserts the national sovereignty of the Irish people. The constitution, based on a system of representative democracy, is broadly within the traditi ...

. An Indian institution recommended by the constitution is the ''panchayat

The Panchayat raj is a political system, originating from the Indian subcontinent, found mainly in India, Pakistan, Bangladesh, Sri Lanka, and Nepal. It is the oldest system of local government in the Indian subcontinent, and historical men ...

'' or village committees. Untouchability

Untouchability is a form of social institution that legitimises and enforces practices that are discriminatory, humiliating, exclusionary and exploitative against people belonging to certain social groups. Although comparable forms of discrimin ...

is illegal (Article 17) and caste distinctions are derecognized (Articles 15(2) and 16(2)). The promulgation of the Indian constitution transformed India into a republic within the Commonwealth.

Dominion Constitution and Government

India as a free and independent dominion within the British Commonwealth of Nations (its title changed in 1949 to "Commonwealth of Nations") came into existence on 15 August 1947 under the provisions of theIndian Independence Act 1947

The Indian Independence Act 1947 947 CHAPTER 30 10 and 11 Geo 6is an Act of the Parliament of the United Kingdom that partitioned British India into the two new independent dominions of India and Pakistan. The Act received Royal Assent on 18 Ju ...

which had received royal assent on 18 July 1947. This act, along with the Government of India Act, 1935

The Government of India Act, 1935 was an Act adapted from the Parliament of the United Kingdom. It originally received royal assent in August 1935. It was the longest Act of (British) Parliament ever enacted until the Greater London Authorit ...

( text here) the latter to be suitably amended to the changed context, served as the constitution of the dominion. Under the Indian Independence Act, the British government relinquished all responsibility of governing the territories that formerly constituted British India

The provinces of India, earlier presidencies of British India and still earlier, presidency towns, were the administrative divisions of British governance on the Indian subcontinent. Collectively, they have been called British India. In one ...

; the legislatures of the new dominions could "repeal or amend" any existing act of the British parliament; no future act of the British parliament would extend to the dominions unless extended so and enacted by the dominion legislature. Reflecting the changed status, the royal style and titles "Indiae Imperator" and "Emperor of India" was abandoned.

In January 1949, India consisted of nine Governors' Provinces, Madras, Bombay, West Bengal, the United Provinces, East Punjab, Bihar, the Central Provinces and Berar, Assam and Orissa; five Chief Commissioners' Provinces, Delhi, Ajmer-Merwara, Coorg, Andaman and Nicobar Islands, and Panth Piploda

Panth-Piploda was a province of British India. It is located in present-day Ratlam district of Madhya Pradesh state of central India.

Panth-Piploda was British India's smallest province, with an area of , and a population of 5267 (male 2666, ...

; and around 500 princely states

A princely state (also called native state or Indian state) was a nominally sovereign entity of the British Indian Empire that was not directly governed by the British, but rather by an Indian ruler under a form of indirect rule, subject to ...

. '' The Statesman's Yearbook'' (1949) stated, "The Governors' Provinces and the Chief Commissioners' Provinces are under the sovereignty of His Majesty the King of the United Kingdom." The princely states were governed by rulers who had ceded power in the areas of defence, external affairs, and communications to the dominion; such states were called "Acceding States." The provinces comprised approximately three-fourths of the dominion's population and three-fifths of the area.

Constitutionally, the Dominion was a federation with authority and responsibility devolving in the following manner. In the case of the Governors' Provinces: in the areas of defence, external affairs, currency and coinage, and communications, authority and responsibility lay with the Dominion legislature; in the administration of justice, public health, religious endowments, land and education, among others, authority lay with the provincial legislature; in the criminal law and procedure, marriage and divorce, succession, factories, labor welfare, workmen's compensation, health, insurance and old-age pensions, responsibility lay concurrently with both, with overriding powers to the Dominion. In the case of the Chief Commissioners' Provinces: the administration was directly by the central government, with the plenary power

A plenary power or plenary authority is a complete and absolute power to take action on a particular issue, with no limitations. It is derived from the Latin term ''plenus'' ("full").

United States

In United States constitutional law, plenary p ...

of legislation belonging to the Dominion legislature. In the case of the Princely States, the areas of legislation which they chose to hand over to the Dominion were expected to be specified in the Instruments of Accession" that were executed by the rulers and accepted the Governor-General; these areas were limited largely to defence, external affairs and communications.

The executive authority

The Executive, also referred as the Executive branch or Executive power, is the term commonly used to describe that part of government which enforces the law, and has overall responsibility for the governance of a state.

In political systems ba ...

of the Dominion was exercised on behalf of King George VI by the Governor-General, who acted on the advice of his Council of Ministers. The cabinet system of responsible government

Responsible government is a conception of a system of government that embodies the principle of parliamentary accountability, the foundation of the Westminster system of parliamentary democracy. Governments (the equivalent of the executive br ...

prevailed at the centre. By convention, the cabinet includes members of minority and backward communities. The Chief Commissioners' Provinces were administered by the Governor-General through a Chief Commissioner appointed by him.

The power to legislate in the Dominion legislature lay with the Constituent Assembly. The allotment of seats to Provinces and Princely States in this assembly were approximately in the ratio of one seat to a million individuals in the population. In the instance of Governors' Provinces, seats were distributed between the main religious communities (General (which included Hindus), Muslims, and in the East Punjab, Sikh) in each provinces in proportion to their population. The representatives from each Governors' Province were elected by the Lower House of the provincial legislature, the voting being by the method of proportional representation with single transferable vote, with the members of the main communities voting in separate constituencies. Of the assembly representatives allotted to the Princely States, half were elected by the State legislatures (or other representative bodies); the remainder was nominated by the ruler.

The plan of the Constituent Assembly of India

The Constituent Assembly of India was elected to frame the Constitution of India. It was elected by the 'Provincial Assembly'. Following India's independence from the British rule in 1947, its members served as the nation's first Parliament as ...

was drawn up during the British Raj

The British Raj (; from Hindi ''rāj'': kingdom, realm, state, or empire) was the rule of the British Crown on the Indian subcontinent;

*

* it is also called Crown rule in India,

*

*

*

*

or Direct rule in India,

* Quote: "Mill, who was him ...

, following negotiations between nationalist leaders and the 1946 Cabinet Mission to India. Its members were elected by the new provincial assemblies formed after the 1946 Indian provincial elections

Provincial elections were held in British India in January 1946 to elect members of the legislative councils of British Indian provinces. The consummation of British rule in India were the 1945/1946 elections. As minor political parties were el ...

held in January. The Constituent Assembly had 299 representatives consisting of 15 women and 284 men. The female members were: Purnima Banerjee, Kamla Chaudhry

Kamla Chaudhry (1908–1970) was an Indian short story writer in Hindi language and Jagadeesh Kumar a Member of Parliament from Hapur in the 3rd Lok Sabha.

Early life

Kamla Chaudhry was born on 22 February 1908 in Lucknow. Her father Rai Man ...

, Malati Choudhury

Malati Devi Choudhury (née Sen) (26 July 1904– 15 March 1998) was an Indian civil rights and freedom activist and Gandhian. She was born in 1904 in an upper middle class Brahmo family. She was the daughter of Barrister Kumud Nath Sen, whom ...

, Durgabai Deshmukh, Rajkumari Amrit Kaur, Sucheta Kriplani

Sucheta Kripalani (''née'' Majumdar; 25 June 1908 – 1 December 1974) was an Indian freedom fighter and politician. She was India's first female Chief Minister, serving as the head of the Uttar Pradesh government from 1963 to 1967.

Early ...

, Annie Mascarene

Annie Mascarene (6 June 1902 – 19 July 1963) was an Indian independence activist, politician and lawyer from Thiruvananthapuram, Kerala who served as a Member of the Parliament of India and was the first woman to do so.

Family and educat ...

, Hansa Jivraj Mehta

Hansa Jivraj Mehta (3 July 1897 – 4 April 1995) was a reformist, social activist, educator, independence activist, feminist and writer from India.

Early life

Hansa Mehta was born in a Nagar Brahmin family on 3 July 1897. She was a daughter ...

, Sarojini Naidu, Vijaya Lakshmi Pandit

Vijaya Lakshmi Pandit (''née'' Swarup Nehru; 18 August 1900 – 1 December 1990) was an Indian diplomat and politician who was the 6th Governor of Maharashtra from 1962 to 1964 and 8th President of the United Nations General Assembly from 19 ...

, Begum Aizaz Rasul

Begum Qudsia Aijaz Rasul (2 April 1909 – 1 August 2001) was the only Muslim woman in the Constituent Assembly of India that drafted the Constitution of India.

Family

Begum Rasool was born on 2 April 1909 as Qudsia Begum, daughter of Sir ...

, Renuka Ray

Renuka Ray (1904–1997) was a noted freedom-fighter, social activist and politician of India.

She was a descendant of Brahmo reformer, Nibaran Chandra Mukherjee, and daughter of Satish Chandra Mukherjee, an ICS officer, and Charulata Mukher ...

, Leela Roy

Leela Roy (2 October 1900 – 11 June 1970), was a radical leftist Indian woman politician and reformer, and a close associate of Netaji Subhash Chandra Bose. She was born in Goalpara, Assam to Girish Chandra Naag, who was a deputy magistrate ...

, Ammu Swaminathan and Dakshayani Velayudhan

Dakshayani Velayudhan (4 July 1912 – 20 July 1978) was an Indian parliamentarian and leader of the Oppressed classes. Belonging to the Pulayar community, she was among the first generation of people to be educated from the community. She ...

. Most were associated with the Indian nationalist movement.

The Interim Government of India

The Interim Government of India, also known as the Provisional Government of India, formed on 2 September 1946 from the newly elected Constituent Assembly of India, had the task of assisting the transition of British India to independence. It ...

was formed on 2 September 1946 from the newly elected members of the Constituent Assembly. The Indian National Congress secured 69 percent of all of the seats, whereas the Muslim League had a smaller number, but significantly all of the seats that were reserved for Muslims. There were also fewer numbers from other parties, such as the Scheduled Caste Federation

The Republican Party of India (RPI, often called the Republican Party or simply Republican) is a political party in India. It has its roots in the Scheduled Castes Federation led by B. R. Ambedkar. The 'Training School for Entrance to Polit ...

, the Communist Party of India

Communist Party of India (CPI) is the oldest Marxist–Leninist communist party in India and one of the nine national parties in the country. The CPI was founded in modern-day Kanpur (formerly known as Cawnpore) on 26 December 1925.

H ...

, and the Unionist Party. In June 1947, members from the provinces of Sindh

Sindh (; ; ur, , ; historically romanized as Sind) is one of the four provinces of Pakistan. Located in the southeastern region of the country, Sindh is the third-largest province of Pakistan by land area and the second-largest province ...

, East Bengal

ur,

, common_name = East Bengal

, status = Province of the Dominion of Pakistan

, p1 = Bengal Presidency

, flag_p1 = Flag of British Bengal.svg

, s1 = Ea ...

, Baluchistan

Balochistan ( ; bal, بلۏچستان; also romanised as Baluchistan and Baluchestan) is a historical region in Western Asia, Western and South Asia, located in the Iranian plateau's far southeast and bordering the Indian Plate and the Arabian S ...

, West Punjab

West Punjab ( pnb, ; ur, ) was a province in the Dominion of Pakistan from 1947 to 1955. The province covered an area of 159,344 km2 (61523 sq mi), including much of the current Punjab province and the Islamabad Capital Territory, but exclu ...

, and the North West Frontier Province withdrew to form the Constituent Assembly of Pakistan

The Constituent Assembly of Pakistan ( bn, পাকিস্তান গণপরিষদ, Pākistān Goṇoporishod; ur, , Aāin Sāz Asimblī) was established in August 1947 to frame a constitution for Pakistan. It also served as its first ...

, which met in Karachi

Karachi (; ur, ; ; ) is the most populous city in Pakistan and 12th most populous city in the world, with a population of over 20 million. It is situated at the southern tip of the country along the Arabian Sea coast. It is the former c ...

.

On 15 August 1947, all the members of the Constituent Assembly who had not withdrawn to Karachi came to constitute the Dominion of India's legislature. Only 28 members of the Muslim League finally joined. Later, 93 members were nominated from the princely states

A princely state (also called native state or Indian state) was a nominally sovereign entity of the British Indian Empire that was not directly governed by the British, but rather by an Indian ruler under a form of indirect rule, subject to ...

. The Congress secured a majority of 82%.

Jawaharlal Nehru took charge as Prime Minister of India

The prime minister of India (IAST: ) is the head of government of the Republic of India. Executive authority is vested in the prime minister and their chosen Council of Ministers, despite the president of India being the nominal head of the ...

on 15 August 1947. Vallabhbhai Patel served as the Deputy Prime Minister

A deputy prime minister or vice prime minister is, in some countries, a government minister who can take the position of acting prime minister when the prime minister is temporarily absent. The position is often likened to that of a vice president, ...

. Lord Mountbatten

Louis Francis Albert Victor Nicholas Mountbatten, 1st Earl Mountbatten of Burma (25 June 1900 – 27 August 1979) was a British naval officer, colonial administrator and close relative of the British royal family. Mountbatten, who was of German ...

, and later C. Rajagopalachari, served as Governor-General

Governor-general (plural ''governors-general''), or governor general (plural ''governors general''), is the title of an office-holder. In the context of governors-general and former British colonies, governors-general are appointed as viceroy t ...

until 26 January 1950, when Rajendra Prasad

Rajendra Prasad (3 December 1884 – 28 February 1963) was an Indian politician, lawyer, Indian independence activist, journalist & scholar who served as the first president of Republic of India from 1950 to 1962. He joined the Indian Nationa ...

was elected as the first President of India

The president of India ( IAST: ) is the head of state of the Republic of India. The president is the nominal head of the executive, the first citizen of the country, as well as the commander-in-chief of the Indian Armed Forces. Droupadi Murm ...

.

Ramachandra Guha"India After Gandhi"

Picador India, 2007. Nehru's cabinet of 15 included one woman.

Demographics

The major demographic effort in the period was directed at measuring the effects of the Partition of India. The creation of Pakistan decisively depended on the proportionally high percentages of Muslims in certain geographical areas of the subcontinent. In the 1941 census, 24.3% of pre-independent India was recorded to be Muslim. In addition, 76 of the 435 districts in India had Muslim majority populations. These districts were home to 60% of the 94.4 million Muslims. The Muslim population was clustered in two regions: the northwest, which included the Punjab, and the east, which included a large part of Bengal. These Muslim-majority districts were to constitute the western and eastern half of Pakistan that came into being in 1947. But there was also a fairly large and spatially spread out minority population of Muslims in India, and a minority of Hindus in Pakistan. It was therefore inevitable that there would be an exchange of the populations involving migration of Muslims into West and East Pakistan and migrations of non-Muslims (mainly Hindus, but also Sikhs in the northwest) from Pakistan into India.Imperial Gazetteer of India

''The Imperial Gazetteer of India'' was a gazetteer of the British Indian Empire, and is now a historical reference work. It was first published in 1881. Sir William Wilson Hunter made the original plans of the book, starting in 1869.< ...

.

File:Hindu percent 1909.jpg, 1909 Percentage of Hindus.

File:Muslim percent 1909.jpg, 1909 Percentage of Muslims.

File:Sikhs buddhists jains percent1909.jpg, 1909 Percentage of Sikhs and others.

Tim Dyson

Tim Dyson (born 1949) is a British demographer with a focus on Indian population history. He is currently Professor Emeritus of Population Studies at the London School of Economics. He was elected as a Fellow of the British Academy in 2001.

Bibli ...