Doctor Zhivago (novel) on:

[Wikipedia]

[Google]

[Amazon]

''Doctor Zhivago'' ( ; rus, До́ктор Жива́го, p=ˈdoktər ʐɨˈvaɡə) is a

18:17 23/10/2013, Елена Меньшенина

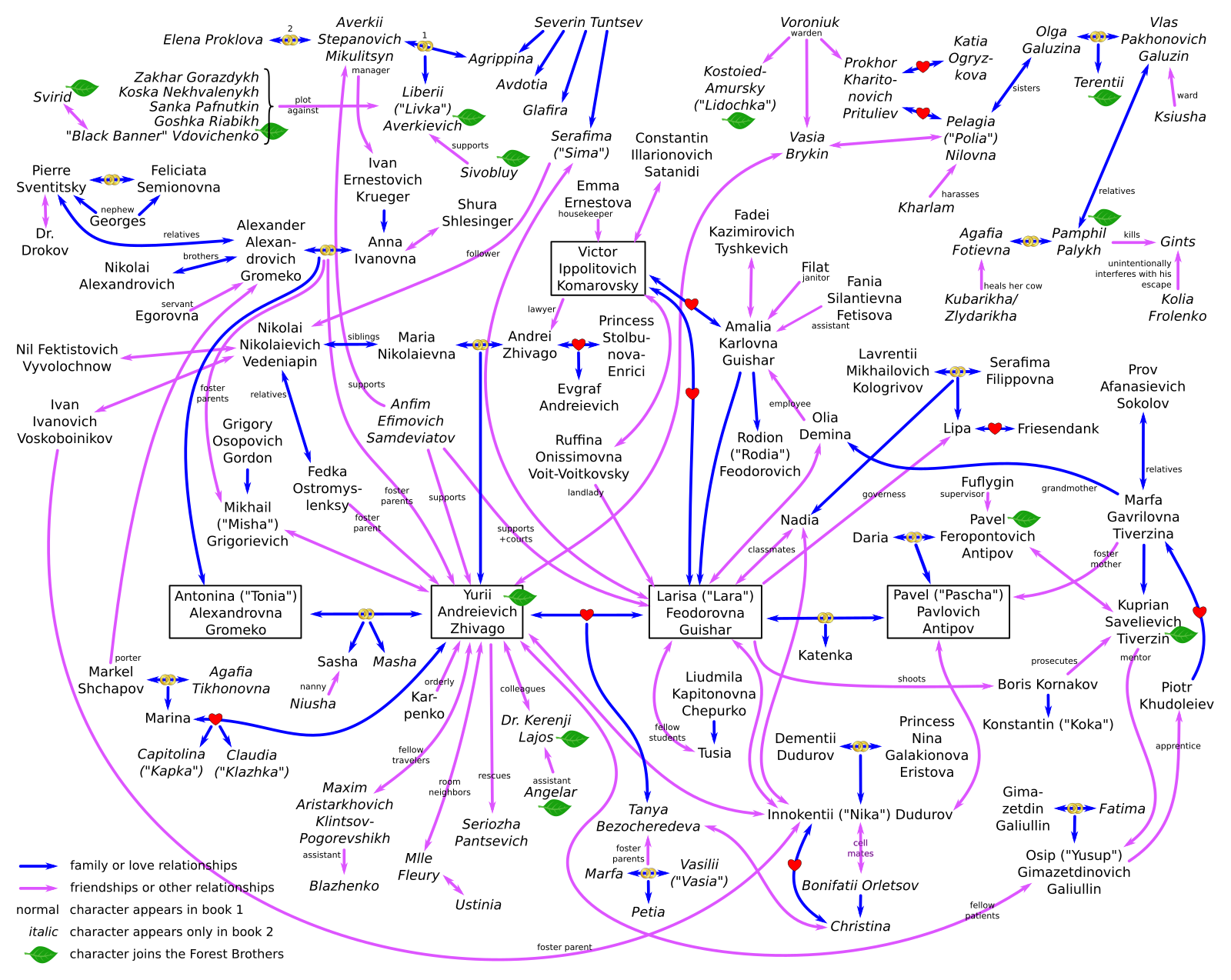

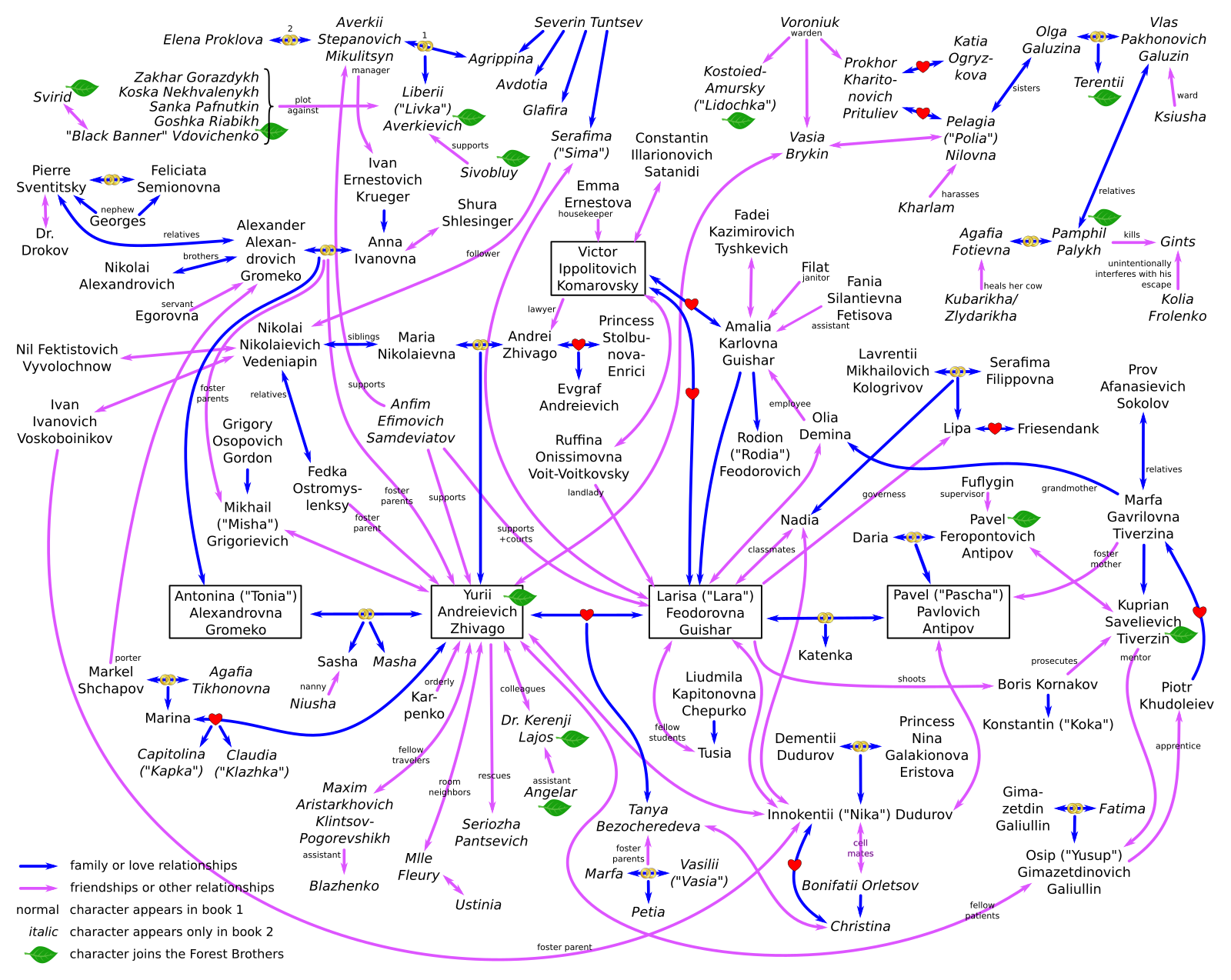

The plot of ''Doctor Zhivago'' is long and intricate. It can be difficult to follow for two reasons. Firstly, Pasternak employs many characters, who interact with each other throughout the book in unpredictable ways. Secondly, he frequently introduces a character by one of his/her three names, then subsequently refers to that character by another of the three names or a nickname, without expressly stating that he is referring to the same character.

The plot of ''Doctor Zhivago'' is long and intricate. It can be difficult to follow for two reasons. Firstly, Pasternak employs many characters, who interact with each other throughout the book in unpredictable ways. Secondly, he frequently introduces a character by one of his/her three names, then subsequently refers to that character by another of the three names or a nickname, without expressly stating that he is referring to the same character.

Author Ivan Tolstoi claims that the

* ''Zhivago'' (Живаго): the Russian root ''zhiv'' means "alive".

* ''Larissa'': a Greek name suggesting "bright, cheerful".

* ''Komarovsky'' (Комаровский): ''komar'' (комар) is the Russian for "mosquito".

* ''Pasha'' (Паша): the diminutive form of "Pavel" (Павел), the Russian rendering of the name

* ''Zhivago'' (Живаго): the Russian root ''zhiv'' means "alive".

* ''Larissa'': a Greek name suggesting "bright, cheerful".

* ''Komarovsky'' (Комаровский): ''komar'' (комар) is the Russian for "mosquito".

* ''Pasha'' (Паша): the diminutive form of "Pavel" (Павел), the Russian rendering of the name

Inside the Zhivago Storm

', by Paolo Mancosu, the story of the first publication of ''Doctor Zhivago'' and of the subsequent Russian editions in the West, *

Zhivago's Secret Journey: From Typescript to Book

' (), by Paolo Mancosu, the story of the typescripts of ''Doctor Zhivago'' that Pasternak sent to the West,

The CIA’s ‘Zhivago’ , by Michael Scammell , The New York Review of Books

Inside the ''Zhivago'' Storm

website accompanying Mancosu's book.

Homegrown ''Doctor Zhivago'' to Debut on Russian Television

"The ''Doctor Zhivago'' caper"

(editorial), ''

"The Wisest Book I Ever Read"

by Robert Morgan from ''

'The ''Dr Zhivago'' Drawings'

artist's rendering

'The Poems of ''Doctor Zhivago

{{DEFAULTSORT:Doctor Zhivago (novel) 1957 in the Soviet Union 1957 novels Adultery in novels Book censorship in the Soviet Union Novels about physicians Novels set in Moscow Novels set in Russia Novels set in the Russian Revolution Novels set during the Russian Civil War Russian novels adapted into films Soviet novels Novels set during World War I Pantheon Books books Dialectical materialism Boris Pasternak Censored books Family saga novels 1905 Russian Revolution

novel

A novel is a relatively long work of narrative fiction, typically written in prose and published as a book. The present English word for a long work of prose fiction derives from the for "new", "news", or "short story of something new", itself ...

by Boris Pasternak

Boris Leonidovich Pasternak (; rus, Бори́с Леони́дович Пастерна́к, p=bɐˈrʲis lʲɪɐˈnʲidəvʲɪtɕ pəstɛrˈnak; 30 May 1960) was a Russian poet, novelist, composer and literary translator. Composed in 1917, Pa ...

, first published in 1957 in Italy

Italy ( it, Italia ), officially the Italian Republic, ) or the Republic of Italy, is a country in Southern Europe. It is located in the middle of the Mediterranean Sea, and its territory largely coincides with the homonymous geographical ...

. The novel is named after its protagonist

A protagonist () is the main character of a story. The protagonist makes key decisions that affect the plot, primarily influencing the story and propelling it forward, and is often the character who faces the most significant obstacles. If a st ...

, Yuri Zhivago, a physician and poet, and takes place between the Russian Revolution of 1905

The Russian Revolution of 1905,. also known as the First Russian Revolution,. occurred on 22 January 1905, and was a wave of mass political and social unrest that spread through vast areas of the Russian Empire. The mass unrest was directed again ...

and World War II

World War II or the Second World War, often abbreviated as WWII or WW2, was a world war that lasted from 1939 to 1945. It involved the World War II by country, vast majority of the world's countries—including all of the great power ...

.

Owing to the author's independent-minded stance on the October Revolution

The October Revolution,. officially known as the Great October Socialist Revolution. in the Soviet Union, also known as the Bolshevik Revolution, was a revolution in Russia led by the Bolshevik Party of Vladimir Lenin that was a key mom ...

, ''Doctor Zhivago'' was refused publication in the USSR

The Soviet Union,. officially the Union of Soviet Socialist Republics. (USSR),. was a transcontinental country that spanned much of Eurasia from 1922 to 1991. A flagship communist state, it was nominally a federal union of fifteen nati ...

. At the instigation of Giangiacomo Feltrinelli

Giangiacomo Feltrinelli (; 19 June 1926 – 14 March 1972) was an influential Italian publisher, businessman, and political activist who was active in the period between the Second World War and Italy's Years of Lead. He founded a vast library ...

, the manuscript was smuggled to Milan

Milan ( , , Lombard: ; it, Milano ) is a city in northern Italy, capital of Lombardy, and the second-most populous city proper in Italy after Rome. The city proper has a population of about 1.4 million, while its metropolitan city ...

and published in 1957. Pasternak was awarded the Nobel Prize for Literature the following year, an event that embarrassed and enraged the Communist Party of the Soviet Union

" Hymn of the Bolshevik Party"

, headquarters = 4 Staraya Square, Moscow

, general_secretary = Vladimir Lenin (first) Mikhail Gorbachev (last)

, founded =

, banned =

, founder = Vladimir Lenin

, newspape ...

.

The novel was made into a film by David Lean

Sir David Lean (25 March 190816 April 1991) was an English film director, producer, screenwriter and editor. Widely considered one of the most important figures in British cinema, Lean directed the large-scale epics ''The Bridge on the River ...

in 1965, and since then has twice been adapted for television, most recently as a miniseries for Russian TV in 2006. The novel ''Doctor Zhivago'' has been part of the Russian school curriculum since 2003, where it is read in 11th grade.«Не читал, но осуждаю!»: 5 фактов о романе «Доктор Живаго»18:17 23/10/2013, Елена Меньшенина

Plot summary

The plot of ''Doctor Zhivago'' is long and intricate. It can be difficult to follow for two reasons. Firstly, Pasternak employs many characters, who interact with each other throughout the book in unpredictable ways. Secondly, he frequently introduces a character by one of his/her three names, then subsequently refers to that character by another of the three names or a nickname, without expressly stating that he is referring to the same character.

The plot of ''Doctor Zhivago'' is long and intricate. It can be difficult to follow for two reasons. Firstly, Pasternak employs many characters, who interact with each other throughout the book in unpredictable ways. Secondly, he frequently introduces a character by one of his/her three names, then subsequently refers to that character by another of the three names or a nickname, without expressly stating that he is referring to the same character.

Part 1

Imperial Russia

The Russian Empire was an empire and the final period of the Russian monarchy from 1721 to 1917, ruling across large parts of Eurasia. It succeeded the Tsardom of Russia following the Treaty of Nystad, which ended the Great Northern War. The ...

, 1902. The novel opens during a Russian Orthodox

Russian Orthodoxy (russian: Русское православие) is the body of several churches within the larger communion of Eastern Orthodox Christianity, whose liturgy is or was traditionally conducted in Church Slavonic language. Most ...

funeral liturgy, or panikhida

A memorial service (Greek: μνημόσυνον, mnemósynon, "memorial"; Slavonic: панихида, panikhída, from Greek παννυχίς, ''pannychis'', "vigil"; Romanian: parastas and Serbian парастос, parastos, from Greek παρ� ...

, for Yuri's mother, Marya Nikolaevna Zhivago. Having long ago been abandoned by his father, Yuri is taken in by his maternal uncle, Nikolai Nikolaevich Vedenyapin, a philosopher and former Orthodox priest who now works for the publisher of a progressive newspaper in a provincial capital on the Volga River

The Volga (; russian: Во́лга, a=Ru-Волга.ogg, p=ˈvoɫɡə) is the longest river in Europe. Situated in Russia, it flows through Central Russia to Southern Russia and into the Caspian Sea. The Volga has a length of , and a catch ...

. Yuri's father, Andrei Zhivago, was once a wealthy member of Moscow's merchant gentry, but has squandered the family's fortune in Siberia through debauchery and carousing.

The next summer, Yuri (who is 11 years old) and Nikolai Nikolaevich travel to Duplyanka, the estate of Lavrenty Mikhailovich Kologrivov, a wealthy silk merchant. They are there not to visit Kologrivov, who is abroad with his wife, but to visit a mutual friend, Ivan Ivanovich Voskoboinikov, an intellectual who lives in the steward's cottage. Kologrivov's daughters, Nadya (who is 15 years old) and Lipa (who is younger), are also living at the estate with a governess and servants. Innokenty (Nika) Dudorov, a 13-year-old boy who is the son of a convicted terrorist has been placed with Ivan Ivanovich by his mother and lives with him in the cottage. As Nikolai Nikolaevich and Ivan Ivanovich are strolling in the garden and discussing philosophy, they notice that a train passing in the distance has come to a stop in an unexpected place, indicating that something is wrong. On the train, an 11-year-old boy named Misha Grigorievich Gordon is traveling with his father. They have been on the train for three days. During that time, a kind man had given Misha small gifts and had talked for hours with his father, Grigory Osipovich Gordon. However, encouraged by his attorney, who was traveling with him, the man had become drunk. Eventually, the man had rushed to the vestibule of the moving train car, pushed aside the boy's father, opened the door and thrown himself out, killing himself. Misha's father had then pulled the emergency brake, bringing the train to a halt. The passengers disembark and view the corpse while the police are called. The deceased's lawyer stands near the body and blames the suicide on alcoholism.

Part 2

During theRusso-Japanese War

The Russo-Japanese War ( ja, 日露戦争, Nichiro sensō, Japanese-Russian War; russian: Ру́сско-япóнская войнá, Rússko-yapónskaya voyná) was fought between the Empire of Japan and the Russian Empire during 1904 and 1 ...

(1904–1905), Amalia Karlovna Guichard arrives in Moscow

Moscow ( , US chiefly ; rus, links=no, Москва, r=Moskva, p=mɐskˈva, a=Москва.ogg) is the capital and largest city of Russia. The city stands on the Moskva River in Central Russia, with a population estimated at 13.0 million ...

from the Urals

The Ural Mountains ( ; rus, Ура́льские го́ры, r=Uralskiye gory, p=ʊˈralʲskʲɪjə ˈɡorɨ; ba, Урал тауҙары) or simply the Urals, are a mountain range that runs approximately from north to south through western ...

with her two children: Rodion (Rodya) and Larissa (Lara). Mme. Guichard's late husband was a Belgian who had been working as an engineer for the railroad and had been friends with Victor Ippolitovich Komarovsky, a lawyer and "cold-blooded businessman." Komarovsky sets them up in rooms at the seedy Montenegro hotel, enrolls Rodion in the Cadet Corps

A corps of cadets, also called cadet corps, was originally a kind of military school for boys. Initially such schools admitted only sons of the nobility or gentry, but in time many of the schools were opened also to members of other social classes ...

and enrolls Lara in a girls' high school. The girls' school is the same school that Nadya Kologrivov attends. On Komarovsky's advice, Amalia invests in a small dress shop. Amalia and her children live at the Montenegro for about a month before moving into the apartment over the dress shop. Despite an ongoing affair with Amalia, Komarovsky begins to groom Lara behind her mother's back.

In early October, the workers of the Moscow-Brest railroad line go on strike. The foreman of the station is Pavel Ferapontovich Antipov. His friend Kiprian Savelyevich Tiverzin is called into one of the railroad workshops and stops a workman from beating his apprentice (whose name is Osip (Yusupka) Gimazetdinovich Galiullin). The police arrest Pavel Ferapontovich for his role in the strike. Pavel Ferapontovich's boy, Patulya (or Pasha or Pashka) Pavlovich Antipov, comes to live with Tiverzin and his mother. Tiverzin's mother and Patulya attend a demonstration which is attacked by dragoons, but they survive and return home. As the protestors flee the dragoons, Nikolai Nikolaevich (Yuri's uncle) is standing inside a Moscow apartment, at the window, watching the people flee. Some time ago, he moved from the Volga region to Petersburg, and at the same time moved Yuri to Moscow to live at the Gromeko household. Nikolai Nikolaevich had then come to Moscow from Petersburg earlier in the Fall, and is staying with the Sventitskys, who were distant relations. The Gromeko household consists of Alexander Alexandrovich Gromeko, his wife Anna Ivanovna, and his bachelor brother Nikolai Alexandrovich. Anna is the daughter of a wealthy steel magnate, now deceased, from the Yuriatin region in the Urals. They have a daughter Tonya.

In January 1906, the Gromekos host a chamber music recital at their home one night. One of the performers is a cellist who is a friend of Amalia's, and her next-door neighbor at the Montenegro. Midway through the performance, the cellist is recalled to the Montenegro because, he is told, someone there is dying. Alexander Alexandrovich, Yuri and Misha come along with the cellist. At the Montenegro, the boys stand in a public corridor outside one of the rooms, embarrassed, while Amalia, who has taken poison, is treated with an emetic

Vomiting (also known as emesis and throwing up) is the involuntary, forceful expulsion of the contents of one's stomach through the mouth and sometimes the nose.

Vomiting can be the result of ailments like food poisoning, gastroenteritis ...

. Eventually, they are shooed into the room by the boarding house employees who are using the corridor. The boys are assured that Amalia is out of danger and, once inside the room, see her, half-naked and sweaty, talking with the cellist; she tells him that she had "suspicions" but "fortunately it all turned out to be foolishness." The boys then notice, in a dark part of the room, a girl (it is Lara) asleep on a chair. Unexpectedly, Komarovsky emerges from behind a curtain and brings a lamp to the table next to Lara's chair. The light wakes her up and she, unaware that Yuri and Misha are watching, shares a private moment with Komarovsky, "as if he were a puppeteer and she a puppet, obedient to the movements of his hand." They exchange conspiratorial glances, pleased that their secret was not discovered and that Amalia did not die. This is the first time Yuri sees Lara, and he is fascinated by the scene. Misha then whispers to Yuri that the man he is watching is the same one who got his father drunk on the train shortly before his father's suicide.

Part 3

In November 1911, Anna Ivanovna Gromeko becomes seriously ill with pneumonia. At this time, Yuri, Misha, and Tonya are studying to be a doctor, philologist, and lawyer respectively. Yuri learns that his father had a child, a boy named Evgraf, by Princess Stolbunova-Enrizzi. The narrative returns to the Spring of 1906. Lara is increasingly tormented by Komarovsky's control over her, which has now been going on for six months. In order to get away from him, she asks her classmate and friend Nadya Laurentovna Kologrivov to help her find work as a tutor. Nadya says she can work for Nadya's own family because her parents happen to be looking for a tutor for her sister Lipa. Lara spends more than three years working as agoverness

A governess is a largely obsolete term for a woman employed as a private tutor, who teaches and trains a child or children in their home. A governess often lives in the same residence as the children she is teaching. In contrast to a nanny, ...

for the Kologrivovs. Lara admires the Kologrivovs, and they love her as if she were their own child. In her fourth year with the Kologrivovs, Lara is visited by her brother Rodya. He needs 700 rubles to cover a debt. Lara says she will try to get the money, and in exchange demands Rodya's cadet revolver along with some cartridges. She obtains the money from Kologrivov. She does not pay the money back, because she uses her wages to help support her boyfriend Pasha Antipov (see above) and his father (who lives in exile), without Pasha's knowledge.

We move forward to 1911. Lara visits the Kologrivovs' country estate with them for the last time. She is becoming discontented with her situation, but she enjoys the pastimes of the estate anyway, and she becomes an excellent shot with Rodya's revolver. When she and the family return to Moscow, her discontent grows. Around Christmastime, she resolves to part from the Kologrivovs, and to ask Komarovsky for the money necessary to do that. She plans to kill him with Rodya's revolver should he refuse her. On 27 December, the date of the Sventitsky's Christmas party, she goes to Komarovsky's home but is informed that he is at a Christmas party. She gets the address of the party and starts toward it, but relents and pays Pasha a visit instead. She tells him that they should get married right away, and he agrees. At the same moment that Lara and Pasha are having this discussion, Yuri and Tonya are passing by Pasha's apartment in the street, on their way to the Sventitskys. They arrive at the party and enjoy the festivities. Later, Lara arrives at the party. She knows no one there other than Komarovsky, and is not dressed for a ball. She tries to get Komarovsky to notice her, but he is playing cards and either does not notice her or pretends not to. Through some quick inferences, she realizes that one of the men playing cards with Komarovsky is Kornakov, a prosecutor of the Moscow court. He prosecuted a group of railway workers that included Kiprian Tiverzin, Pasha's foster father.

Later, while Yuri and Tonya are dancing, a shot rings out. There is a great commotion and it is discovered that Lara has shot Kornakov (not Komarovsky) and Kornakov has received only a minor wound. Lara has fainted and is being dragged by some guests to a chair; Yuri recognizes her with amazement. Yuri goes to render medical attention to Lara but then changes course to Kornakov because he is the nominal victim. He pronounces Kornakov's wound to be "a trifle", and is about to tend to Lara when Mrs. Sventitsky and Tonya urgently tell him that he must return home because something was not right with Anna Ivanovna. When Yuri and Tonya return home, they find that Anna Ivanovna has died.

Part 4

Komarovsky uses his political connections to shield Lara from prosecution. Lara and Pasha marry, graduate from university, and depart by train for Yuriatin. The narrative moves to the second autumn of theFirst World War

World War I (28 July 1914 11 November 1918), often abbreviated as WWI, was List of wars and anthropogenic disasters by death toll, one of the deadliest global conflicts in history. Belligerents included much of Europe, the Russian Empire, ...

. Yuri has married Tonya and is working as a doctor at a hospital in Moscow. Tonya gives birth to their first child, a son. Back in Yuriatin, the Antipovs also have their first child, a girl named Katenka. Although he loves Lara deeply, Pasha feels increasingly stifled by her love for him. In order to escape, he volunteers for the Imperial Russian Army

The Imperial Russian Army (russian: Ру́сская импера́торская а́рмия, tr. ) was the armed land force of the Russian Empire, active from around 1721 to the Russian Revolution of 1917. In the early 1850s, the Russian Ar ...

. Lara starts to work as a teacher in Yuriatin. Sometime later, she leaves Yuriatin and goes to a town in Galicia

Galicia may refer to:

Geographic regions

* Galicia (Spain), a region and autonomous community of northwestern Spain

** Gallaecia, a Roman province

** The post-Roman Kingdom of the Suebi, also called the Kingdom of Gallaecia

** The medieval King ...

, to look for Pasha. The town happens to be where Yuri is now working as a military doctor. Elsewhere, Lt. Antipov is taken prisoner by the Austro-Hungarian Army

The Austro-Hungarian Army (, literally "Ground Forces of the Austro-Hungarians"; , literally "Imperial and Royal Army") was the ground force of the Austro-Hungarian Dual Monarchy from 1867 to 1918. It was composed of three parts: the joint arm ...

, but is erroneously declared missing in action

Missing in action (MIA) is a casualty classification assigned to combatants, military chaplains, combat medics, and prisoners of war who are reported missing during wartime or ceasefire. They may have been killed, wounded, captured, ex ...

. Wounded by artillery fire, Yuri is sent to a battlefield hospital in the town of Meliuzeevo, where Lara is his nurse. Galiullin (the apprentice who was beaten in Part 2) is also in Lara's ward, recovering from injuries. He is now a lieutenant in Pasha's unit; he informs Lara that Pasha is alive, but she doubts him. Lara gets to know Yuri better but is not impressed with him. At the very end of this Part, it is announced in the hospital that there has been a revolution.

Part 5

After his recovery, Zhivago stays on at the hospital as a physician. This puts him at close quarters with Lara. They are both (along with Galiullin) trying to get permission to leave and return to their homes. In Meliuzeevo, a newly arrivedcommissar

Commissar (or sometimes ''Kommissar'') is an English transliteration of the Russian (''komissar''), which means ' commissary'. In English, the transliteration ''commissar'' often refers specifically to the political commissars of Soviet and E ...

for the Provisional Government

A provisional government, also called an interim government, an emergency government, or a transitional government, is an emergency governmental authority set up to manage a political transition generally in the cases of a newly formed state or ...

, whose name is Gintz, is informed that a local military unit has deserted and is camped in a nearby cleared forest. Gintz decides to accompany a troop of Cossacks who have been summoned to surround and disarm the deserters. He believes he can appeal to the deserters' pride as "soldiers in the world's first revolutionary army." A train of mounted Cossacks arrives and the Cossacks quickly surround the deserters. Gintz enters the circle of horsemen and makes a speech to the deserters. His speech backfires so badly that the Cossacks who are there to support him gradually sheath their sabres, dismount and start to fraternize with the deserters. The Cossack officers advise Gintz to flee; he does, but he is pursued by the deserters and brutally murdered by them at the railroad station.

Shortly before he leaves, Yuri says goodbye to Lara. He starts by expressing his excitement over the fact that "the roof over the whole of Russia has been torn off, and we and all the people find ourselves under the open sky" with true freedom for the first time. Despite himself, he then starts to clumsily tell Lara that he has feelings for her. Lara stops him and they part. A week later, they leave by different trains, she to Yuriatin and he to Moscow. On the train to Moscow, Yuri reflects on how different the world has become, and on his "honest trying with all his might not to love ara

ARA may refer to:

Media and the arts

* American-Romanian Academy of Arts and Sciences

* '' Artistička Radna Akcija'', compilation album released in former Yugoslavia

* Associate of the Royal Academy, denoting membership in the British Royal Acad ...

"

Parts 6 to 9

Following theOctober Revolution

The October Revolution,. officially known as the Great October Socialist Revolution. in the Soviet Union, also known as the Bolshevik Revolution, was a revolution in Russia led by the Bolshevik Party of Vladimir Lenin that was a key mom ...

and the subsequent Russian Civil War

{{Infobox military conflict

, conflict = Russian Civil War

, partof = the Russian Revolution and the aftermath of World War I

, image =

, caption = Clockwise from top left:

{{flatlist,

*Soldiers ...

, Yuri and his family decide to flee by train to Tonya's family's former estate (called Varykino), located near the town of Yuriatin in the Ural Mountains

The Ural Mountains ( ; rus, Ура́льские го́ры, r=Uralskiye gory, p=ʊˈralʲskʲɪjə ˈɡorɨ; ba, Урал тауҙары) or simply the Urals, are a mountain range that runs approximately from north to south through western ...

. During the journey, he has an encounter with Army Commissar Strelnikov ("The Executioner"), a fearsome commander who summarily executes both captured Whites

White is a racialized classification of people and a skin color specifier, generally used for people of European origin, although the definition can vary depending on context, nationality, and point of view.

Description of populations as ...

and many civilians. Yuri and his family settle in an abandoned house on the estate. Over the winter, they read books to each other and Yuri writes poetry and journal entries. Spring comes and the family prepares for farm work. Yuri visits Yuriatin to use the public library, and during one of these visits sees Lara at the library. He decides to talk with her, but finishes up some work first, and when he looks up she is gone. He gets her home address from a request slip she had given the librarian. On another visit to town, he visits her at her apartment (which she shares with her daughter). She informs him that Strelnikov is indeed Pasha, her husband. During one of Yuri's subsequent visits to Yuriatin they consummate their relationship. They meet at her apartment regularly for more than two months, but then Yuri, while returning from one of their trysts to his house on the estate, is abducted by men loyal to Liberius, commander of the "Forest Brotherhood," the Bolshevik guerrilla band.

Parts 10 to 13

Liberius is a dedicatedOld Bolshevik

Old Bolshevik (russian: ста́рый большеви́к, ''stary bolshevik''), also called Old Bolshevik Guard or Old Party Guard, was an unofficial designation for a member of the Bolshevik faction of the Russian Social Democratic Labour Par ...

and highly effective leader of his men. However, Liberius is also a cocaine

Cocaine (from , from , ultimately from Quechua: ''kúka'') is a central nervous system (CNS) stimulant mainly used recreationally for its euphoric effects. It is primarily obtained from the leaves of two Coca species native to South Am ...

addict, loud-mouthed and narcissist

Narcissism is a self-centered personality style characterized as having an excessive interest in one's physical appearance or image and an excessive preoccupation with one's own needs, often at the expense of others.

Narcissism exists on a co ...

ic. He repeatedly bores Yuri with his long-winded lectures about the glories of socialism and the inevitability of its victory. Yuri spends more than two years with Liberius and his partisans, then finally manages to escape. After a grueling journey back to Yuriatin, made largely on foot, Yuri goes into town to see Lara first, rather than to Varykino to see his family. In town, he learns that his wife, children, and father-in-law fled the estate and returned to Moscow. From Lara, he learns that Tonya delivered a daughter after he left. Lara assisted at the birth and she and Tonya became close friends. Yuri gets a job and stays with Lara and her daughter for a few months. Eventually, a townsperson delivers a letter to Yuri from Tonya, which Tonya wrote five months before and which has passed through innumerable hands to reach Yuri. In the letter, Tonya informs him that she, the children, and her father are being deported, probably to Paris. She says "The whole trouble is that I love you and you do not love me," and "We will never, ever see each other again." When Yuri finishes reading the letter, he has chest pains and faints.

Part 14

Komarovsky reappears. Having used his influence within theCPSU

"Hymn of the Bolshevik Party"

, headquarters = 4 Staraya Square, Moscow

, general_secretary = Vladimir Lenin (first)Mikhail Gorbachev (last)

, founded =

, banned =

, founder = Vladimir Lenin

, newspaper ...

, Komarovsky has been appointed Minister of Justice of the Far Eastern Republic

The Far Eastern Republic ( rus, Дальневосто́чная Респу́блика, ДВР, r=Dalnevostochnaya Respublika, DVR, p=dəlʲnʲɪvɐˈstotɕnəjə rʲɪsˈpublʲɪkə), sometimes called the Chita Republic, was a nominally indep ...

, a Soviet puppet state

A puppet state, puppet régime, puppet government or dummy government, is a state that is ''de jure'' independent but ''de facto'' completely dependent upon an outside power and subject to its orders.Compare: Puppet states have nominal sove ...

in Siberia

Siberia ( ; rus, Сибирь, r=Sibir', p=sʲɪˈbʲirʲ, a=Ru-Сибирь.ogg) is an extensive geographical region, constituting all of North Asia, from the Ural Mountains in the west to the Pacific Ocean in the east. It has been a part ...

. He offers to smuggle Yuri and Lara outside Soviet soil. They initially refuse, but Komarovsky states, falsely, that Pasha Antipov is dead, having fallen from favor with the Party. Stating that this will place Lara in the Cheka

The All-Russian Extraordinary Commission ( rus, Всероссийская чрезвычайная комиссия, r=Vserossiyskaya chrezvychaynaya komissiya, p=fsʲɪrɐˈsʲijskəjə tɕrʲɪzvɨˈtɕæjnəjə kɐˈmʲisʲɪjə), abbreviated ...

's crosshairs, he persuades Yuri that it is in her best interests to leave for the East. Yuri convinces Lara to go with Komarovsky, telling her that he will follow her shortly. Meanwhile, the hunted General Strelnikov (Pasha) returns for Lara. Lara, however, has already left with Komarovsky. After expressing regret over the pain he has caused his country and loved ones, Pasha commits suicide

Suicide is the act of intentionally causing one's own death. Mental disorders (including depression, bipolar disorder, schizophrenia, personality disorders, anxiety disorders), physical disorders (such as chronic fatigue syndrome), and ...

. Yuri finds his body the following morning.

Part 15

After returning to Moscow, Zhivago's health declines; he marries another woman, Marina, and fathers two children with her. He also plans numerous writing projects which he never finishes. Yuri leaves his new family and his friends to live alone in Moscow and work on his writing. However, after living on his own for a short time, he dies of a heart attack while riding the tram. Meanwhile, Lara returns to Russia to learn of her dead husband and ends up attending Yuri Zhivago's funeral. She persuades Yuri's half-brother, who is nowNKVD

The People's Commissariat for Internal Affairs (russian: Наро́дный комиссариа́т вну́тренних дел, Naródnyy komissariát vnútrennikh del, ), abbreviated NKVD ( ), was the interior ministry of the Soviet Union.

...

General Yevgraf Zhivago, to assist her in her search for a daughter that she had conceived with Yuri, but had abandoned in the Urals. Ultimately, however, Lara disappears, believed arrested during Joseph Stalin

Joseph Vissarionovich Stalin (born Ioseb Besarionis dze Jughashvili; – 5 March 1953) was a Georgian revolutionary and Soviet Union, Soviet political leader who led the Soviet Union from 1924 until his death in 1953. He held power as Ge ...

's Great Purge

The Great Purge or the Great Terror (russian: Большой террор), also known as the Year of '37 (russian: 37-й год, translit=Tridtsat sedmoi god, label=none) and the Yezhovshchina ('period of Yezhov'), was Soviet General Secreta ...

and dying in the Gulag

The Gulag, an acronym for , , "chief administration of the camps". The original name given to the system of camps controlled by the State Political Directorate, GPU was the Main Administration of Corrective Labor Camps (, )., name=, group= ...

, "a nameless number on a list that was later misplaced."

Epilogue

DuringWorld War II

World War II or the Second World War, often abbreviated as WWII or WW2, was a world war that lasted from 1939 to 1945. It involved the World War II by country, vast majority of the world's countries—including all of the great power ...

, Zhivago's old friends Nika Dudorov and Misha Gordon meet up. One of their discussions revolves around a local laundress named Tanya, a ''bezprizornaya'', or war orphan, and her resemblance to both Yuri and Lara. Tanya tells both men of the difficult childhood she has had due to her mother abandoning her in order to marry Komarovsky. Much later, the two men meet over the first edition of Yuri Zhivago's poems.

Background

Soviet censorship's refusal

Although it contains passages written in the 1910s and 1920s, ''Doctor Zhivago'' was not completed until 1955. The novel was submitted to the literary journal ''Novy Mir

''Novy Mir'' (russian: links=no, Новый мир, , ''New World'') is a Russian-language monthly literary magazine.

History

''Novy Mir'' has been published in Moscow since January 1925. It was supposed to be modelled on the popular pre-Soviet ...

'' ("Новый Мир") in 1956. However, the editors rejected Pasternak's novel because of its implicit rejection of socialist realism

Socialist realism is a style of idealized realistic art that was developed in the Soviet Union and was the official style in that country between 1932 and 1988, as well as in other socialist countries after World War II. Socialist realism is ch ...

. The author, like Zhivago, showed more concern for the welfare of individuals than for the welfare of society. Soviet censors construed some passages as anti-Soviet

Anti-Sovietism, anti-Soviet sentiment, called by Soviet authorities ''antisovetchina'' (russian: антисоветчина), refers to persons and activities actually or allegedly aimed against the Soviet Union or government power within the ...

. They also objected to Pasternak's subtle criticisms of Stalinism

Stalinism is the means of governing and Marxist-Leninist policies implemented in the Soviet Union from 1927 to 1953 by Joseph Stalin. It included the creation of a one-party totalitarian police state, rapid industrialization, the the ...

, Collectivization

Collective farming and communal farming are various types of, "agricultural production in which multiple farmers run their holdings as a joint enterprise". There are two broad types of communal farms: agricultural cooperatives, in which member- ...

, the Great Purge

The Great Purge or the Great Terror (russian: Большой террор), also known as the Year of '37 (russian: 37-й год, translit=Tridtsat sedmoi god, label=none) and the Yezhovshchina ('period of Yezhov'), was Soviet General Secreta ...

, and the Gulag

The Gulag, an acronym for , , "chief administration of the camps". The original name given to the system of camps controlled by the State Political Directorate, GPU was the Main Administration of Corrective Labor Camps (, )., name=, group= ...

.

Translations

Pasternak sent several copies of the manuscript in Russian to friends in the West. In 1957, Italian publisherGiangiacomo Feltrinelli

Giangiacomo Feltrinelli (; 19 June 1926 – 14 March 1972) was an influential Italian publisher, businessman, and political activist who was active in the period between the Second World War and Italy's Years of Lead. He founded a vast library ...

arranged for the novel to be smuggled out of the Soviet Union by Sergio D'Angelo. Upon handing his manuscript over, Pasternak quipped, "You are hereby invited to watch me face the firing squad

Execution by firing squad, in the past sometimes called fusillading (from the French ''fusil'', rifle), is a method of capital punishment, particularly common in the military and in times of war. Some reasons for its use are that firearms are ...

." Despite desperate efforts by the Union of Soviet Writers

The Union of Soviet Writers, USSR Union of Writers, or Soviet Union of Writers (russian: Союз писателей СССР, translit=Soyuz Sovetstikh Pisatelei) was a creative union of professional writers in the Soviet Union. It was founded ...

to prevent its publication, Feltrinelli published an Italian translation of the book in November 1957. So great was the demand for ''Doctor Zhivago'' that Feltrinelli was able to license translation rights into eighteen different languages well in advance of the novel's publication. The Communist Party of Italy

The Italian Communist Party ( it, Partito Comunista Italiano, PCI) was a communist political party in Italy.

The PCI was founded as ''Communist Party of Italy'' on 21 January 1921 in Livorno by seceding from the Italian Socialist Party (PSI). ...

expelled Feltrinelli from their membership in retaliation for his role in the publication of a novel they felt was critical of communism.

A French translation was published by Éditions Gallimard

Éditions Gallimard (), formerly Éditions de la Nouvelle Revue Française (1911–1919) and Librairie Gallimard (1919–1961), is one of the leading French book publishers. In 2003 it and its subsidiaries published 1,418 titles.

Founded by Ga ...

in June 1958, with an English translation being published in September 1958.

Russian text published by CIA

The U.S.Central Intelligence Agency

The Central Intelligence Agency (CIA ), known informally as the Agency and historically as the Company, is a civilian foreign intelligence service of the federal government of the United States, officially tasked with gathering, processing, ...

realized that the novel presented an opportunity to embarrass the Soviet government. An internal memo lauded the book's "great propaganda value": not only did the text have a central humanist message, but the Soviet government's having suppressed a great work of literature could make ordinary citizens "wonder what is wrong with their government".

The CIA set out to publish 1,000 copies of a Russian-language hardcover edition at Mouton Publishers of the Hague in early September 1958, and arranged for 365 of them, in Mouton's trademark blue linen cover, to be distributed at the Vatican pavilion at the 1958 Brussels world's fair

Expo 58, also known as the 1958 Brussels World's Fair (french: Exposition Universelle et Internationale de Bruxelles de 1958, nl, Brusselse Wereldtentoonstelling van 1958), was a world's fair held on the Heysel/Heizel Plateau in Brussels, Bel ...

.

The printing by Mouton Publishers of the 1,000 copies of an adulterated Russian-language version, organized by the CIA, had typos and truncated storylines, and it was illegal, because the owner of the manuscript was Giangiacomo Feltrinelli, who later put his name on the Mouton edition.Social sciences – A Quarterly Journal of the Russian Academy of Sciences: INTERNATIONAL PROVOCATION: ON BORIS PASTERNAK’S NOBEL PRIZEAuthor Ivan Tolstoi claims that the

CIA

The Central Intelligence Agency (CIA ), known informally as the Agency and historically as the Company, is a civilian foreign intelligence service of the federal government of the United States, officially tasked with gathering, processing, ...

lent a hand to ensure that ''Doctor Zhivago'' was submitted to the Nobel Committee

A Nobel Committee is a working body responsible for most of the work involved in selecting Nobel Prize laureates. There are five Nobel Committees, one for each Nobel Prize.

Four of these committees (for prizes in physics, chemistry, physio ...

in its original language, in order for Pasternak to win the Nobel prize and further harm the international credibility of the Soviet Union

The Soviet Union,. officially the Union of Soviet Socialist Republics. (USSR),. was a transcontinental country that spanned much of Eurasia from 1922 to 1991. A flagship communist state, it was nominally a federal union of fifteen nationa ...

. He repeats and adds additional details to Fetrinelli's claims that CIA operatives intercepted and photographed a manuscript of the novel and secretly printed a small number of books in the Russian language

Russian (russian: русский язык, russkij jazyk, link=no, ) is an East Slavic language mainly spoken in Russia. It is the native language of the Russians, and belongs to the Indo-European language family. It is one of four living E ...

. Recently released CIA documents do not show that the agency's efforts in publishing a Russian-language edition were intended to help Pasternak win the Nobel, however.

, a Russian philologist, also contributed her research about the history of publications, following the publication of Lazar Fleishman's book ''Russian Emigration Discovers "Doctor Zhivago"'', where she thought that the only possible conclusion was that the pirated edition of ''Doctor Zhivago'' was initiated by one of the biggest émigré organizations in Europe: the Central Association of Postwar Émigrées. While CAPE was known to engage in anti-Soviet activities, the printing of this edition was not an imposition of its own political will but rather a response to the spiritual demands of the Russian emigration that was greatly stirred by the release of Pasternak's novel in Italian without an original Russian edition.

Award

In 1958 Pasternak wrote to Renate Schweitzer,Some people believe the Nobel Prize may be awarded to me this year. I am firmly convinced that I shall be passed over and that it will go toOn 23 October 1958, Boris Pasternak was announced as the winner of the 1958 Nobel Prize for Literature. The citation credited Pasternak's contribution to Russian lyric poetry and for his role in, "continuing the great Russian epic tradition". On 25 October, Pasternak sent aAlberto Moravia Alberto Moravia ( , ; born Alberto Pincherle ; 28 November 1907 – 26 September 1990) was an Italian novelist and journalist. His novels explored matters of modern sexuality, social alienation and existentialism. Moravia is best known for his de .... You cannot imagine all the difficulties, torments, and anxieties which arise to confront me at the mere prospect, however unlikely, of such a possibility... One step out of place—and the people closest to you will be condemned to suffer from all the jealousy, resentment, wounded pride and disappointment of others, and old scars on the heart will be reopened...

telegram

Telegraphy is the long-distance transmission of messages where the sender uses symbolic codes, known to the recipient, rather than a physical exchange of an object bearing the message. Thus flag semaphore is a method of telegraphy, whereas ...

to the Swedish Academy

The Swedish Academy ( sv, Svenska Akademien), founded in 1786 by King Gustav III, is one of the Royal Academies of Sweden. Its 18 members, who are elected for life, comprise the highest Swedish language authority. Outside Scandinavia, it is bes ...

:

Infinitely grateful, touched, proud, surprised, overwhelmed.On 26 October, the ''Literary Gazette'' ran an article by David Zaslavski entitled, "

Reactionary

In political science, a reactionary or a reactionist is a person who holds political views that favor a return to the '' status quo ante'', the previous political state of society, which that person believes possessed positive characteristics abs ...

Propaganda

Propaganda is communication that is primarily used to influence or persuade an audience to further an agenda, which may not be objective and may be selectively presenting facts to encourage a particular synthesis or perception, or using loaded ...

Uproar over a Literary Weed".

Acting on direct orders from the Politburo

A politburo () or political bureau is the executive committee for communist parties. It is present in most former and existing communist states.

Names

The term "politburo" in English comes from the Russian ''Politbyuro'' (), itself a contracti ...

, the KGB surrounded Pasternak's dacha in Peredelkino

Peredelkino ( rus, Переде́лкино, p=pʲɪrʲɪˈdʲelkʲɪnə) is a dacha complex situated just to the southwest of Moscow, Russia.

History

The settlement originated as the estate of Peredeltsy, owned by the Leontievs (maternal rela ...

. Pasternak was not only threatened with arrest, but the KGB also vowed to send his mistress Olga Ivinskaya back to the gulag

The Gulag, an acronym for , , "chief administration of the camps". The original name given to the system of camps controlled by the State Political Directorate, GPU was the Main Administration of Corrective Labor Camps (, )., name=, group= ...

, where she had been imprisoned under Stalin. It was further hinted that, if Pasternak traveled to Stockholm

Stockholm () is the capital and largest city of Sweden as well as the largest urban area in Scandinavia. Approximately 980,000 people live in the municipality, with 1.6 million in the urban area, and 2.4 million in the metropo ...

to collect his Nobel Medal, he would be refused re-entry to the Soviet Union.

As a result, on 29 October Pasternak sent a second telegram to the Nobel Committee:

In view of the meaning given the award by the society in which I live, I must renounce this undeserved distinction which has been conferred on me. Please do not take my voluntary renunciation amiss.The Swedish Academy announced:

This refusal, of course, in no way alters the validity of the award. There remains only for the Academy, however, to announce with regret that the presentation of the Prize cannot take place. (Via )

Soviet revenge

Despite his decision to decline the award, the Soviet Union of Writers continued to denounce Pasternak in the Soviet press. Furthermore, he was threatened at the very least with formal exile to the West. In response, Pasternak wrote directly to Soviet PremierNikita Khrushchev

Nikita Sergeyevich Khrushchev (– 11 September 1971) was the First Secretary of the Communist Party of the Soviet Union from 1953 to 1964 and chairman of the country's Council of Ministers from 1958 to 1964. During his rule, Khrushchev s ...

, "Leaving the motherland will mean equal death for me. I am tied to Russia by birth, by life and work."

After being ousted from power in 1964, Khrushchev read the novel and felt great regret for having banned the book at all.

As a result of this and the intercession of Indian Prime Minister Jawaharlal Nehru

Pandit Jawaharlal Nehru (; ; ; 14 November 1889 – 27 May 1964) was an Indian Anti-colonial nationalism, anti-colonial nationalist, secular humanist, social democrat—

*

*

*

* and author who was a central figure in India du ...

, Pasternak was not expelled from his homeland.

Ultimately, Bill Mauldin

William Henry Mauldin (; October 29, 1921 – January 22, 2003) was an American editorial cartoonist who won two Pulitzer Prizes for his work. He was most famous for his World War II cartoons depicting American soldiers, as represented by th ...

produced a political cartoon

A political cartoon, a form of editorial cartoon, is a cartoon graphic with caricatures of public figures, expressing the artist's opinion. An artist who writes and draws such images is known as an editorial cartoonist. They typically combin ...

lampooning the Soviet State's campaign against Boris Pasternak. The cartoon depicts Pasternak and another convict splitting trees in the snow. In the caption, Pasternak says, "I won the Nobel Prize for literature. What was your crime?" The cartoon won the Pulitzer Prize for Editorial Cartooning

The Pulitzer Prize for Illustrated Reporting and Commentary is one of the fourteen Pulitzer Prizes that is annually awarded for journalism in the United States. It is the successor to the Pulitzer Prize for Editorial Cartooning awarded from 1922 t ...

in 1959.

Doctor Zhivago after author's death

Pasternak died oflung cancer

Lung cancer, also known as lung carcinoma (since about 98–99% of all lung cancers are carcinomas), is a malignant lung tumor characterized by uncontrolled cell growth in tissues of the lung. Lung carcinomas derive from transformed, mali ...

in his dacha in Peredelkino on the evening of 30 May 1960. He first summoned his sons, and in their presence said, "Who will suffer most because of my death? Who will suffer most? Only Oliusha will, and I haven't had time to do anything for her. The worst thing is that she will suffer."Ivinskaya (1978), pp. 323–326 Pasternak's last words were, "I can't hear very well. And there's a mist in front of my eyes. But it will go away, won't it? Don't forget to open the window tomorrow."

Shortly before his death, a priest of the Russian Orthodox Church

, native_name_lang = ru

, image = Moscow July 2011-7a.jpg

, imagewidth =

, alt =

, caption = Cathedral of Christ the Saviour in Moscow, Russia

, abbreviation = ROC

, type ...

had given Pasternak the last rites

The last rites, also known as the Commendation of the Dying, are the last prayers and ministrations given to an individual of Christian faith, when possible, shortly before death. They may be administered to those awaiting execution, mortall ...

. Later, in the strictest secrecy, an Orthodox funeral liturgy, or Panikhida

A memorial service (Greek: μνημόσυνον, mnemósynon, "memorial"; Slavonic: панихида, panikhída, from Greek παννυχίς, ''pannychis'', "vigil"; Romanian: parastas and Serbian парастос, parastos, from Greek παρ� ...

, was offered in the family's dacha.

Despite only a small notice appearing in the ''Literary Gazette'', handwritten notices carrying the date and time of the funeral were posted throughout the Moscow subway system. As a result, thousands of admirers traveled from Moscow to Pasternak's civil funeral in Peredelkino. According to Jon Stallworthy

Jon Howie Stallworthy, (18 January 1935 – 19 November 2014) was a British literary critic and poet. He was Professor of English at the University of Oxford from 1992 to 2000, and Professor Emeritus in retirement. He was also a Fellow of Wolfso ...

, "Volunteers carried his open coffin to his burial place and those who were present (including the poet Andrey Voznesensky

Andrei Andreyevich Voznesensky (russian: link=no, Андре́й Андре́евич Вознесе́нский, 12 May 1933 – 1 June 2010) was a Soviet and Russian poet and writer who had been referred to by Robert Lowell as "one of th ...

) recited from memory the banned poem 'Hamlet'."

One of the dissident speakers at the graveside service said, "God

In monotheistic thought, God is usually viewed as the supreme being, creator, and principal object of faith. Swinburne, R.G. "God" in Honderich, Ted. (ed)''The Oxford Companion to Philosophy'', Oxford University Press, 1995. God is typically ...

marks the path of the elect with thorns, and Pasternak was picked out and marked by God. He believed in eternity and he will belong to it... We excommunicated Tolstoy

Count Lev Nikolayevich TolstoyTolstoy pronounced his first name as , which corresponds to the romanization ''Lyov''. () (; russian: link=no, Лев Николаевич Толстой,In Tolstoy's day, his name was written as in pre-refor ...

, we disowned Dostoyevsky

Fyodor Mikhailovich Dostoevsky (, ; rus, Фёдор Михайлович Достоевский, Fyódor Mikháylovich Dostoyévskiy, p=ˈfʲɵdər mʲɪˈxajləvʲɪdʑ dəstɐˈjefskʲɪj, a=ru-Dostoevsky.ogg, links=yes; 11 November 18219 ...

, and now we disown Pasternak. Everything that brings us glory we try to banish to the West

West is a cardinal direction or compass point.

West or The West may also refer to:

Geography and locations

Global context

* The Western world

* Western culture and Western civilization in general

* The Western Bloc, countries allied with NATO ...

... But we cannot allow this. We love Pasternak and we revere him as a poet... Glory to Pasternak!"

Until the 1980s, Pasternak's poetry was only published in heavily censored form. Furthermore, his reputation continued to be pilloried in State propaganda until Mikhail Gorbachev

Mikhail Sergeyevich Gorbachev (2 March 1931 – 30 August 2022) was a Soviet politician who served as the 8th and final leader of the Soviet Union from 1985 to the country's dissolution in 1991. He served as General Secretary of the Com ...

proclaimed perestroika

''Perestroika'' (; russian: links=no, перестройка, p=pʲɪrʲɪˈstrojkə, a=ru-perestroika.ogg) was a political movement for reform within the Communist Party of the Soviet Union (CPSU) during the late 1980s widely associated wit ...

.

In 1988, after decades of circulating in samizdat

Samizdat (russian: самиздат, lit=self-publishing, links=no) was a form of dissident activity across the Eastern Bloc in which individuals reproduced censored and underground makeshift publications, often by hand, and passed the document ...

, ''Doctor Zhivago'' was finally serialized in the pages of ''Novy Mir'', which had changed to a more anti-communist

Anti-communism is political and ideological opposition to communism. Organized anti-communism developed after the 1917 October Revolution in the Russian Empire, and it reached global dimensions during the Cold War, when the United States and the ...

position than in Pasternak's lifetime. The following year, Yevgeny Borisovich Pasternak was at last permitted to travel to Stockholm to collect his father's Nobel Medal. At the ceremony, cellist Mstislav Rostropovich

Mstislav Leopoldovich Rostropovich, (27 March 192727 April 2007) was a Russian cellist and conductor. He is considered by many to be the greatest cellist of the 20th century. In addition to his interpretations and technique, he was well ...

performed a Bach

Johann Sebastian Bach (28 July 1750) was a German composer and musician of the late Baroque period. He is known for his orchestral music such as the ''Brandenburg Concertos''; instrumental compositions such as the Cello Suites; keyboard wor ...

composition in honor of his fellow Soviet dissident

Soviet dissidents were people who disagreed with certain features of Soviet ideology or with its entirety and who were willing to speak out against them. The term ''dissident'' was used in the Soviet Union in the period from the mid-1960s until ...

.

The novel has been part of the Russian school curriculum since 2003, where it is taught in 11th grade.

Themes

Loneliness

In the shadow of all this grand political change, we see that everything is governed by the basic human longing for companionship. Zhivago and Pasha, in love with the same woman, both traverse Russia in these volatile times in search of such stability. They are both involved in nearly every level of the tumultuous times that Russia faced in the first half of the 20th century, yet the common theme and the motivating force behind all their movement is a want of a steady home life. When we first meet Zhivago he is being torn away from everything he knows. He is sobbing and standing on the grave of his mother. We bear witness to the moment all stability is destroyed in his life and the rest of the novel is his attempts to recreate the security stolen from him at such a young age. After the loss of his mother, Zhivago develops a longing for whatFreud

Sigmund Freud ( , ; born Sigismund Schlomo Freud; 6 May 1856 – 23 September 1939) was an Austrian neurologist and the founder of psychoanalysis, a clinical method for evaluating and treating pathologies explained as originating in conflicts i ...

called the "maternal object" (feminine love and affection), in his later romantic relationships with women. His first marriage, to Tonya, is not one born of passion but from friendship. In a way, Tonya takes on the role of the mother-figure that Zhivago always sought but lacked. This, however, was not a romantic tie; while he feels loyal to her throughout his life, he never could find true happiness with her, for their relationship lacks the fervor that was integral to his relationship to Lara.

Disillusionment with revolutionary ideology

In the beginning of the novel, between the1905 Russian Revolution

The Russian Revolution of 1905,. also known as the First Russian Revolution,. occurred on 22 January 1905, and was a wave of mass political and social unrest that spread through vast areas of the Russian Empire. The mass unrest was directed again ...

and World War I

World War I (28 July 1914 11 November 1918), often abbreviated as WWI, was List of wars and anthropogenic disasters by death toll, one of the deadliest global conflicts in history. Belligerents included much of Europe, the Russian Empire, ...

, characters freely debate different philosophical and political ideas including Marxism, but after the revolution and the state-enforced terror of war communism

War communism or military communism (russian: Военный коммунизм, ''Voyennyy kommunizm'') was the economic and political system that existed in Soviet Russia during the Russian Civil War from 1918 to 1921.

According to Soviet histo ...

, Zhivago and others cease to talk politics. Zhivago, a stubborn non-conformist, rants within himself at the "blindness" of revolutionary propaganda and grows exasperated with "the conformity and transparency of the hypocrisy" of his friends who adhere to the prevailing dogma. Zhivago's mental and even physical health crumble under the strain of "a constant, systematic dissembling" by which citizens, rather than thinking for themselves, are expected to "show hemselvesday by day contrary to what hey

Hey or Hey! may refer to:

Music

* Hey (band), a Polish rock band

Albums

* ''Hey'' (Andreas Bourani album) or the title song (see below), 2014

* ''Hey!'' (Julio Iglesias album) or the title song, 1980

* ''Hey!'' (Jullie album) or the title ...

feel." In the epilogue, in which Russia is enveloped in World War II

World War II or the Second World War, often abbreviated as WWII or WW2, was a world war that lasted from 1939 to 1945. It involved the World War II by country, vast majority of the world's countries—including all of the great power ...

, the characters Dudorov and Gordon discuss how the war united Russia against a real enemy, which was better than the preceding days of the Great Purge

The Great Purge or the Great Terror (russian: Большой террор), also known as the Year of '37 (russian: 37-й год, translit=Tridtsat sedmoi god, label=none) and the Yezhovshchina ('period of Yezhov'), was Soviet General Secreta ...

when Russians were turned against one another by the deadly, artificial ideology of totalitarianism

Totalitarianism is a form of government and a political system that prohibits all opposition parties, outlaws individual and group opposition to the state and its claims, and exercises an extremely high if not complete degree of control and regu ...

. This reflects Pasternak's hope that the trials of the Great Patriotic War

The Eastern Front of World War II was a theatre of conflict between the European Axis powers against the Soviet Union (USSR), Poland and other Allies, which encompassed Central Europe, Eastern Europe, Northeast Europe (Baltics), an ...

would, to quote translator Richard Pevear, "lead to the final liberation that had been the promise of the ussianRevolution from the beginning."

Coincidence and the unpredictability of reality

In contrast to thesocialist realism

Socialist realism is a style of idealized realistic art that was developed in the Soviet Union and was the official style in that country between 1932 and 1988, as well as in other socialist countries after World War II. Socialist realism is ch ...

that was imposed as the official artistic style of the Soviet Union

The Soviet Union,. officially the Union of Soviet Socialist Republics. (USSR),. was a transcontinental country that spanned much of Eurasia from 1922 to 1991. A flagship communist state, it was nominally a federal union of fifteen nationa ...

, Pasternak's novel relies heavily on unbelievable coincidences (a reliance for which the plot was criticized). Pasternak uses the frequently-intersecting paths of his cast of characters not only to tell several different people's stories over the decades-long course of the novel, but also to emphasize the chaotic, unpredictable nature of the time period in which it is set, and of reality more generally. In the end, immediately before his death, Zhivago has a revelation of "several existences developing side by side, moving next to each other at different speeds, and about one person's fate getting ahead of another's in life, and who outlives whom." This reflects the crisscrossing journeys of characters over decades, and represents the capricious chance governing their lives.

Literary criticism

Edmund Wilson

Edmund Wilson Jr. (May 8, 1895 – June 12, 1972) was an American writer and literary critic who explored Freudian and Marxist themes. He influenced many American authors, including F. Scott Fitzgerald, whose unfinished work he edited for publi ...

wrote of the novel: "Doctor Zhivago will, I believe, come to stand as one of the great events in man's literary and moral history". V. S. Pritchett

Sir Victor Sawdon Pritchett (also known as VSP; 16 December 1900 – 20 March 1997) was a British writer and literary critic.

Pritchett was known particularly for his short stories, collated in a number of volumes. His non-fiction works incl ...

wrote in the ''New Statesman

The ''New Statesman'' is a British political and cultural magazine published in London. Founded as a weekly review of politics and literature on 12 April 1913, it was at first connected with Sidney and Beatrice Webb and other leading members ...

'' that the novel is " e first work of genius to come out of Russia since the revolution." When the novel came out in Italian, Anders Österling

Anders Österling (13 April 1884 – 13 December 1981) was a Swedish poet, critic and translator. In 1919 he was elected as a member of the Swedish Academy when he was 35 years old and served the Academy for 62 years, longer than any other me ...

, the then permanent secretary of the Swedish Academy

The Swedish Academy ( sv, Svenska Akademien), founded in 1786 by King Gustav III, is one of the Royal Academies of Sweden. Its 18 members, who are elected for life, comprise the highest Swedish language authority. Outside Scandinavia, it is bes ...

which awards the Nobel Prize in Literature

)

, image = Nobel Prize.png

, caption =

, awarded_for = Outstanding contributions in literature

, presenter = Swedish Academy

, holder = Annie Ernaux (2022)

, location = Stockholm, Sweden

, year = 1901

, ...

, wrote in January 1958: “A strong patriotic accent comes through, but with no trace of empty propaganda... With its abundant documentation, its intense local color and its psychological frankness, this work bears convincing witness to the fact that the creative faculty in literature is in no sense extinct in Russia. It is hard to believe that the Soviet authorities might seriously envisage forbidding its publication in the land of its birth.” Some literary critics "found that there was no real plot to the novel, that its chronology was confused, that the main characters were oddly effaced, that the author relied far too much on contrived coincidences."Richard Pevear, Introduction, Pevear & Volokhonsky trans. Vladimir Nabokov

Vladimir Vladimirovich Nabokov (russian: link=no, Владимир Владимирович Набоков ; 2 July 1977), also known by the pen name Vladimir Sirin (), was a Russian-American novelist, poet, translator, and entomologist. Bor ...

, who had celebrated Pasternak's books of poetry as works of "pure, unbridled genius", however, considered the novel to be "a sorry thing, clumsy, trite and melodramatic, with stock situations, voluptuous lawyers, unbelievable girls, romantic robbers and trite coincidences." On the other hand, some critics praised it for being things that, in the opinion of translator Richard Pevear, it was never meant to be: a moving love story, or a lyrical biography of a poet in which the individual is set against the grim realities of Soviet life. Pasternak defended the numerous coincidences in the plot, saying that they are "traits to characterize that somewhat willful, free, fanciful flow of reality." In response to criticism in the West of his novel's characters and coincidences, Pasternak wrote to Stephen Spender

Sir Stephen Harold Spender (28 February 1909 – 16 July 1995) was an English poet, novelist and essayist whose work concentrated on themes of social injustice and the class struggle. He was appointed Poet Laureate Consultant in Poetry by th ...

:

Names and places

* ''Zhivago'' (Живаго): the Russian root ''zhiv'' means "alive".

* ''Larissa'': a Greek name suggesting "bright, cheerful".

* ''Komarovsky'' (Комаровский): ''komar'' (комар) is the Russian for "mosquito".

* ''Pasha'' (Паша): the diminutive form of "Pavel" (Павел), the Russian rendering of the name

* ''Zhivago'' (Живаго): the Russian root ''zhiv'' means "alive".

* ''Larissa'': a Greek name suggesting "bright, cheerful".

* ''Komarovsky'' (Комаровский): ''komar'' (комар) is the Russian for "mosquito".

* ''Pasha'' (Паша): the diminutive form of "Pavel" (Павел), the Russian rendering of the name Paul

Paul may refer to:

*Paul (given name), a given name (includes a list of people with that name)

* Paul (surname), a list of people

People

Christianity

*Paul the Apostle (AD c.5–c.64/65), also known as Saul of Tarsus or Saint Paul, early Chri ...

.

* ''Strelnikov'' (Стрельников): Pasha/Pavel Antipov's pseudonym, ''strelok'' means "the shooter"; he is also called ''Rasstrelnikov'' (Расстрельников), which means "executioner".

* ''Yuriatin'' (Юрятин): the fictional town was based upon Perm

Perm or PERM may refer to:

Places

*Perm, Russia, a city in Russia

** Permsky District, the district

**Perm Krai, a federal subject of Russia since 2005

**Perm Oblast, a former federal subject of Russia 1938–2005

**Perm Governorate, an administra ...

, near by which Pasternak had lived for several months in 1916. This can be understood in Russian as "Yuri's town".

* The public reading room at Yuriatin was based on the Pushkin Library, Perm.

Adaptations

Television

* A 1959 Brazilian television series (currently unavailable) was the first screen adaptation. * A 2002 British television serial, ''Doctor Zhivago

''Doctor Zhivago'' is the title of a novel by Boris Pasternak and its various adaptations.

Description

The story, in all of its forms, describes the life of the fictional Russian physician and poet Yuri Zhivago and deals with love and loss during ...

'' stars Hans Matheson, Keira Knightley

Keira Christina Righton (; née Knightley, born 26 March 1985) is an English actress. Known for her work in both independent films and blockbusters, particularly period dramas, she has received several accolades, including nominations for ...

, Alexandra Maria Lara

Alexandra Maria Lara (''née'' Plătăreanu; 12 November 1978) is a Romanian-German actress who has appeared in '' Downfall'' (2004), ''Control'' (2007), '' Youth Without Youth'' (2007), ''The Reader'' (2008), '' Rush'' (2013), and ''Geostorm' ...

, and Sam Neill

Sir Nigel John Dermot "Sam" Neill (born 14 September 1947) is a New Zealand actor. Neill's near-50 year career has included leading roles in both dramas and blockbusters. Considered an "international leading man", he has been regarded as one o ...

. It was broadcast by ITV in the UK in November 2002 and on ''Masterpiece Theatre

''Masterpiece'' (formerly known as ''Masterpiece Theatre'') is a drama anthology television series produced by WGBH Boston. It premiered on Public Broadcasting Service (PBS) on January 10, 1971. The series has presented numerous acclaimed Briti ...

'' in the US in November 2003.

* A 2006 Russian mini-series produced by Mosfilm

Mosfilm (russian: Мосфильм, ''Mosfil’m'' ) is a film studio which is among the largest and oldest in the Russian Federation and in Europe. Founded in 1924 in the USSR as a production unit of that nation's film monopoly, its output inclu ...

. Its total running time is over 500 minutes (8 hours and 26 minutes).

Film

* The most famous adaptation of ''Doctor Zhivago'' is the 1965 film adaptation byDavid Lean

Sir David Lean (25 March 190816 April 1991) was an English film director, producer, screenwriter and editor. Widely considered one of the most important figures in British cinema, Lean directed the large-scale epics ''The Bridge on the River ...

, featuring the Egyptian actor Omar Sharif

Omar Sharif ( ar, عمر الشريف ; born Michel Yusef Dimitri Chalhoub , 10 April 193210 July 2015) was an Egyptian actor, generally regarded as one of his country's greatest male film stars. He began his career in his native country in the ...

as Zhivago and English actress Julie Christie

Julie Frances Christie (born 14 April 1940) is a British actress. An icon of the Swinging Sixties, Christie is the recipient of numerous accolades including an Academy Award, a BAFTA Award, a Golden Globe, and a Screen Actors Guild Award. She ...

as Lara, with Geraldine Chaplin

Geraldine Leigh Chaplin (born July 31, 1944) is an American actress. She is the daughter of Charlie Chaplin, the first of eight children with his fourth wife, Oona O'Neill. After beginnings in dance and modeling, she turned her attention to act ...

as Tonya and Alec Guinness

Sir Alec Guinness (born Alec Guinness de Cuffe; 2 April 1914 – 5 August 2000) was an English actor. After an early career on the stage, Guinness was featured in several of the Ealing comedies, including '' Kind Hearts and Coronets'' (1 ...

as Yevgraf. The film was commercially successful and won five Oscars

The Academy Awards, better known as the Oscars, are awards for artistic and technical merit for the American and international film industry. The awards are regarded by many as the most prestigious, significant awards in the entertainment ind ...

. It is still considered a classic film, remembered also for Maurice Jarre

Maurice-Alexis Jarre (; 13 September 1924 – 28 March 2009) allmusic Biography/ref> was a French composer and conductor. Although he composed several concert works, Jarre is best known for his film scores, particularly for his collaborations wit ...

's score, which features the romantic "Lara's Theme

"Lara's Theme" is the name given to a leitmotif written for the film ''Doctor Zhivago'' (1965) by composer Maurice Jarre. Soon afterward, the leitmotif became the basis of the song "Somewhere, My Love". Numerous versions, both orchestral and voca ...

". Though faithful to the novel's plot, depictions of several characters and events are noticeably different, and many side stories are dropped.

Theatre

* A musical called ''Doktor Zhivago'' premiered inPerm, Russia

Perm (russian: Пермь, p=pʲermʲ), previously known as Yagoshikha (Ягошиха) (1723–1781), and Molotov (Молотов) (1940–1957), is the largest city and the administrative centre of Perm Krai, Russia. The city is located on ...

in the Urals

The Ural Mountains ( ; rus, Ура́льские го́ры, r=Uralskiye gory, p=ʊˈralʲskʲɪjə ˈɡorɨ; ba, Урал тауҙары) or simply the Urals, are a mountain range that runs approximately from north to south through western ...

on 22 March 2007, and remained in the repertoire of Perm Drama Theatre throughout its 50th Anniversary year.

* ''Doctor Zhivago

''Doctor Zhivago'' is the title of a novel by Boris Pasternak and its various adaptations.

Description

The story, in all of its forms, describes the life of the fictional Russian physician and poet Yuri Zhivago and deals with love and loss during ...

'' is a musical adaptation of the novel. It originally premiered as ''Zhivago'' at the La Jolla Playhouse

La Jolla Playhouse is a not-for-profit, professional theatre on the campus of the University of California, San Diego.

History

La Jolla Playhouse was founded in 1947 by Gregory Peck, Dorothy McGuire, and Mel Ferrer. In 1983, it was revived under ...

in 2006. Ivan Hernandez played the title role. It was revised and premiered as ''Doctor Zhivago'' at the Lyric Theatre, Sydney

Lyric may refer to:

* Lyrics, the words, often in verse form, which are sung, usually to a melody, and constitute the semantic content of a song

* Lyric poetry is a form of poetry that expresses a subjective, personal point of view

* Lyric, from t ...

in February 2011, starring Anthony Warlow

Anthony Warlow (born 18 November 1961) is an Australian musical theatre performer, noted for his character acting and considerable vocal range. He is a classically trained lyric baritone and made his debut with the Australian Opera in 1980.

...

and Lucy Maunder

Lucy Maunder, is an Australian cabaret and theatre performer. She originated the role of Lara in the Australian premiere of ''Doctor Zhivago'' opposite Anthony Warlow, and has toured with her own cabaret ''Songs in the Key of Black'', releasing ...

and produced by John Frost. The musical features a score by Lucy Simon

Lucy Elizabeth Simon (May 5, 1940 – October 20, 2022) was an American composer for the theatre and of popular songs. She recorded and performed as a singer and songwriter, and was known for the musicals ''The Secret Garden'' (1991) and '' Doc ...

, a book by Michael Weller

Michael Weller (born September 26, 1942) is a Brooklyn-based playwright and screen writer. His plays include '' Moonchildren'', ''Loose Ends'', ''Spoils of War'' and ''Fifty Words''. His screenplays include ''Ragtime'', for which he was nominat ...

, and lyrics by Michael Korie and Amy Powers (''Lizzie Borden'' and songs for ''Sunset Boulevard

Sunset Boulevard is a boulevard in the central and western part of Los Angeles, California, that stretches from the Pacific Coast Highway in Pacific Palisades east to Figueroa Street in Downtown Los Angeles. It is a major thoroughfare in ...

''). Both the 2006 and the 2011 productions were directed by Des McAnuff

Desmond Steven McAnuff (born June 19, 1952) is the American-Canadian former artistic director of Canada's Stratford Festival and director of such Broadway musical theatre productions as '' Big River'', '' The Who's Tommy'' and '' Jersey Boys''.

...

.

* The Swedish-language musical ''Zjivago' premiered at Malmö Opera in Sweden on 29 August 2014.

* A musical was produced in Japan by the Takarazuka Revue in February 2018.

Translations into English

* Max Hayward andManya Harari

Manya Harari (née Manya Benenson) (8 April 1905 – 24 September 1969)P. J. V. Rolo"Harari , Manya (1905–1969)" ''Oxford Dictionary of National Biography'', Oxford University Press, 2004; online edn, January 2011. was a British translator of ...

(1958)

* Richard Pevear and Larissa Volokhonsky

Richard Pevear and Larissa Volokhonsky are literary translators best known for their collaborative English translations of classic Russian literature. Individually, Pevear has also translated into English works from French, Italian, and Greek. The ...

(2010)

* Nicolas Pasternak Slater, illustrated with 68 pictures by Leonid Pasternak

Leonid Osipovich Pasternak (born ''Yitzhok-Leib'', or ''Isaak Iosifovich, Pasternak''; russian: Леони́д О́сипович Пастерна́к, 3 April 1862 ( N.S.) – 31 May 1945) was a Russian post-impressionist painter. He was the f ...

(2019)

References

Further reading

*Inside the Zhivago Storm

', by Paolo Mancosu, the story of the first publication of ''Doctor Zhivago'' and of the subsequent Russian editions in the West, *

Zhivago's Secret Journey: From Typescript to Book

' (), by Paolo Mancosu, the story of the typescripts of ''Doctor Zhivago'' that Pasternak sent to the West,

External links

The CIA’s ‘Zhivago’ , by Michael Scammell , The New York Review of Books

Inside the ''Zhivago'' Storm

website accompanying Mancosu's book.

Homegrown ''Doctor Zhivago'' to Debut on Russian Television

"The ''Doctor Zhivago'' caper"

(editorial), ''

The Boston Globe

''The Boston Globe'' is an American daily newspaper founded and based in Boston, Massachusetts. The newspaper has won a total of 27 Pulitzer Prizes, and has a total circulation of close to 300,000 print and digital subscribers. ''The Boston Glob ...

'', 20 February 2007."The Wisest Book I Ever Read"

by Robert Morgan from ''

The Raleigh News & Observer

''The News & Observer'' is an American regional daily newspaper that serves the greater Triangle area based in Raleigh, North Carolina. The paper is the largest in circulation in the state (second is the ''Charlotte Observer''). The paper has bee ...

''.'The ''Dr Zhivago'' Drawings'

artist's rendering