Djuna Barnes on:

[Wikipedia]

[Google]

[Amazon]

Djuna Barnes (, June 12, 1892 – June 18, 1982) was an American artist, illustrator, journalist, and writer who is perhaps best known for her novel ''

Of these, the most important was probably her engagement to

Of these, the most important was probably her engagement to

''The Book of Repulsive Women''

toward the modernist experimentation of her later work. They differed, however, on the proper subject of literature; Joyce thought writers should focus on commonplace subjects and make them extraordinary, while Barnes was always drawn to the unusual, even the grotesque. Then, too, her own life was an extraordinary subject. Her autobiographical first novel ''Ryder'' would not only present readers with the difficulty of deciphering its shifting literary styles—a technique inspired by ''Ulysses''—but also with the challenge of piecing together the history of an unconventional polygamous household, far removed from most readers' expectations and experience. Despite the difficulties of the text, ''Ryder''s bawdiness drew attention, and it briefly became a ''New York Times'' bestseller. Its popularity caught the publisher unprepared; a first edition of 3,000 sold out quickly, but by the time more copies made it into bookstores, public interest in the book had died down. Still, the advance allowed Barnes to buy a new apartment on Rue Saint-Romain, where she lived with Thelma Wood starting in September 1927. The move made them neighbors of

(1915) collects eight "rhythms" and five drawings. The poems show the strong influence of late 19th century

''The Book of Repulsive Women: 8 Rhythms and 5 Drawings''

New York: Guido Bruno, 1915. *''A Book'' (1923) – revised versions published as: **''

Baroness Elsa: Gender, Dada and Everyday Modernity

'' Cambridge, MA: MIT Press. * Gammel, Irene (2012).

Lacing up the Gloves: Women, Boxing and Modernity

" ''Cultural and Social History'' 9.3: 369–390. * * * * * * * Larabee, Ann (1991). "The Early Attic Stage of Djuna Barnes". In Broe, ''Silence and Power'', 37–44. * Marcus, Jane. "Mousemeat: Contemporary Reviews of ''Nightwood''". Broe, 195–204. * Reprinted from *Messerli, Douglas. Djuna Barnes: A Bibliography. New York: David Lewis, 1975. *Page, Chester (2007) MEMOIRS OF A CHARMED LIFE IN NEW YORK. Memories of Djuna Barnes. iUNIVERSE. * *Parsons, Deborah. "Djuna Barnes: Melancholic Modernism." ''The Cambridge Companion to the Modernist Novel.'' Ed. Morag Shiach. New York: Cambridge University Press. 165–177

Google Books

* Ponsot, Marie (1991). "A Reader's Ryder". In Broe, ''Silence and Power'', 94–112. * Retallack, Joan (1991). "One Acts: Early Plays of Djuna Barnes". In Broe, ''Silence and Power'', 46–52. * * * * *University of London. "First International Djuna Barnes Conference." Institute of English Studies, 2012.

Irwin Cohen collection

which consists of artwork, clippings, manuscripts, proofs, photographs, and publications by and about Djuna Barnes and her era at the

Emily Holmes Coleman papers

a

Special Collections, University of Delaware Library

''James Joyce'' by Djuna Barnes: ''Vanity Fair'', March, 1922

— about the women of the

''The Book of Repulsive Women''

a

A Celebration of Women Writers

The Confessions of Helen Westley

— an interview *

What Do You See, Madam?

— one of Barnes's early newspaper short stories * {{DEFAULTSORT:Barnes, Djuna 1892 births 1982 deaths American women novelists American women poets American satirists Anti-natalists Bisexual artists Bisexual women Bisexual writers Modernist women writers American LGBT journalists 20th-century American novelists 20th-century American women writers 20th-century American women artists Modernist writers American expatriates in France American LGBT poets American LGBT novelists LGBT people from New York (state) 20th-century American poets People from Orange County, New York Women satirists Women erotica writers Journalists from New York (state) Novelists from New York (state) American women non-fiction writers 20th-century American non-fiction writers 20th-century American journalists American women journalists Lost Generation writers 20th-century LGBT people Members of the American Academy of Arts and Letters

Nightwood

''Nightwood'' is a 1936 novel by American author Djuna Barnes that was first published by publishing house Faber and Faber. It is one of the early prominent novels to portray explicit homosexuality between women, and as such can be considered ...

'' (1936), a cult classic of lesbian fiction and an important work of modernist literature

Literary modernism, or modernist literature, originated in the late 19th and early 20th centuries, and is characterized by a self-conscious break with traditional ways of writing, in both poetry and prose fiction writing. Modernism experimented ...

.Parsons, 165-6.

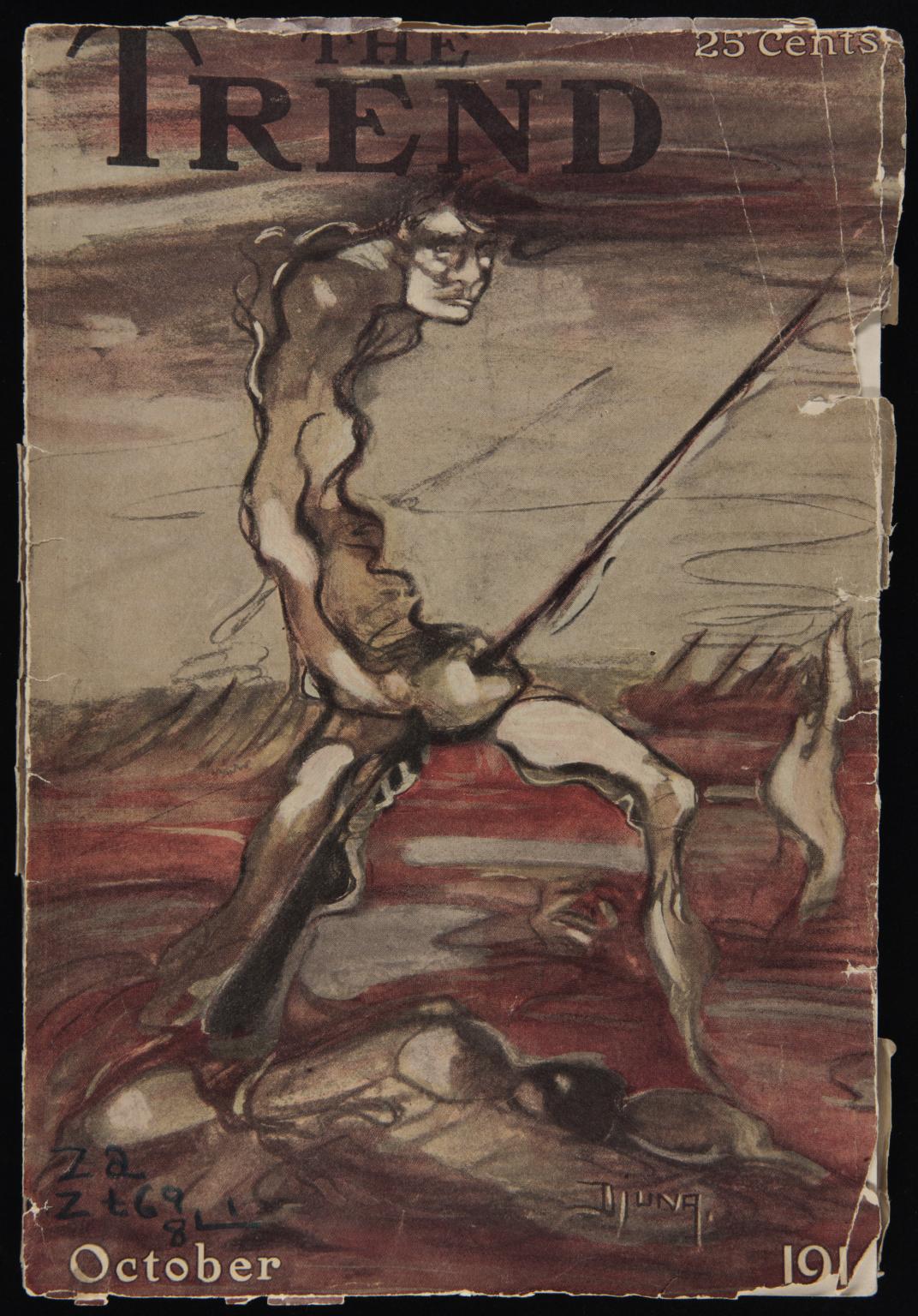

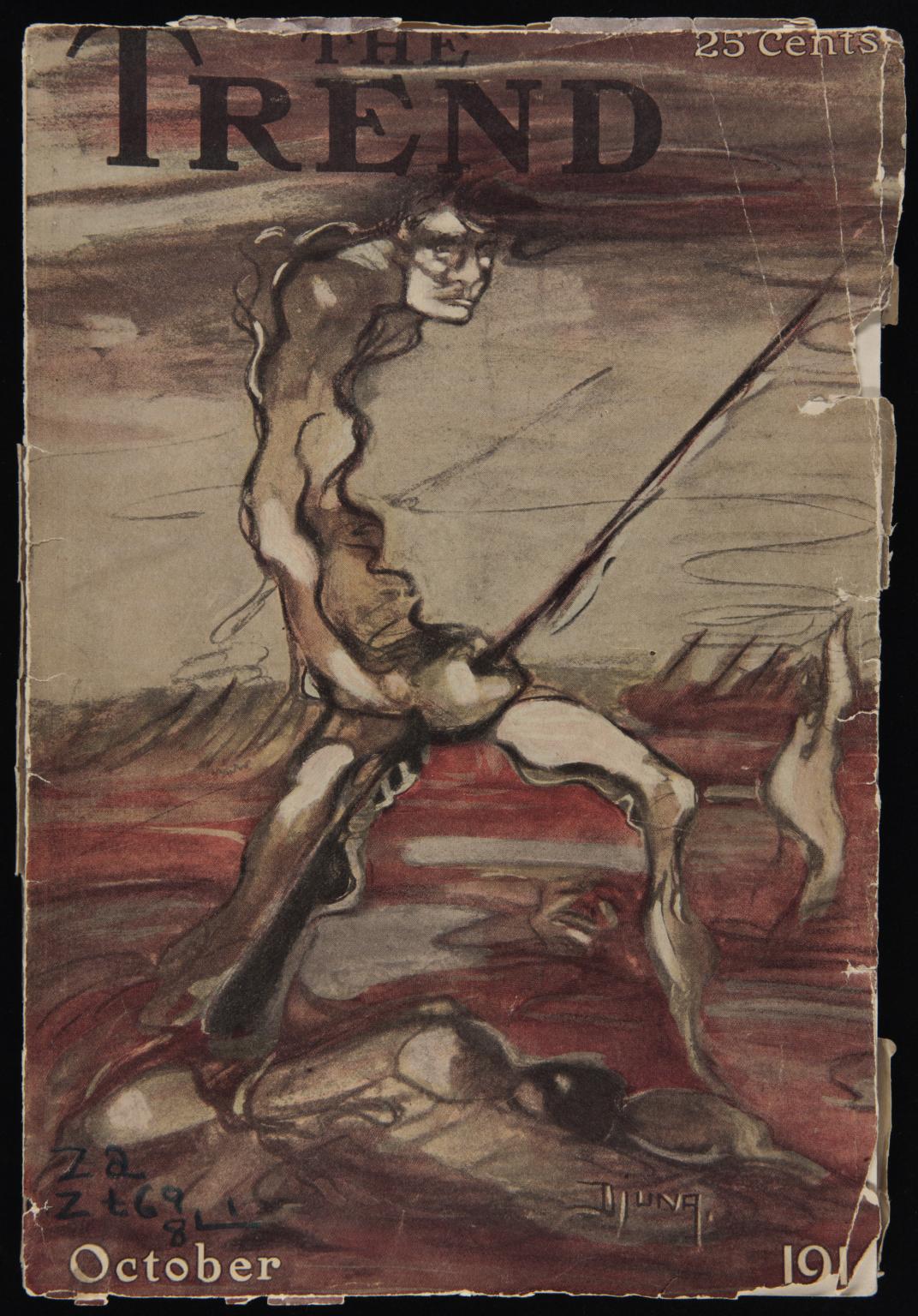

In 1913, Barnes began her career as a freelance journalist and illustrator for the ''Brooklyn Daily Eagle

:''This article covers both the historical newspaper (1841–1955, 1960–1963), as well as an unrelated new Brooklyn Daily Eagle starting 1996 published currently''

The ''Brooklyn Eagle'' (originally joint name ''The Brooklyn Eagle'' and ''King ...

''. By early 1914, Barnes was a highly sought feature reporter, interviewer, and illustrator whose work appeared in the city's leading newspapers and periodicals.Parsons, 166. Later, Barnes's talent and connections with prominent Greenwich Village

Greenwich Village ( , , ) is a neighborhood on the west side of Lower Manhattan in New York City, bounded by 14th Street to the north, Broadway to the east, Houston Street to the south, and the Hudson River to the west. Greenwich Village ...

bohemians afforded her the opportunity to publish her prose, poems, illustrations, and one-act plays in both avant-garde literary journals and popular magazines, and publish an illustrated volume of poetry, ''The Book of Repulsive Women'' (1915).

In 1921, a lucrative commission with ''McCall's

''McCall's'' was a monthly American women's magazine, published by the McCall Corporation, that enjoyed great popularity through much of the 20th century, peaking at a readership of 8.4 million in the early 1960s. It was established as a small-f ...

'' took Barnes to Paris, where she lived for the next 10 years. In this period she published ''A Book'' (1923), a collection of poetry, plays, and short stories, which was later reissued, with the addition of three stories, as ''A Night Among the Horses'' (1929), ''Ladies Almanack

''Ladies Almanack'', its complete title being ''Ladies Almanack: showing their Signs and their Tides; their Moons and their Changes; the Seasons as it is with them; their Eclipses and Equinoxes; as well as a full Record of diurnal and nocturnal Dis ...

'' (1928), and ''Ryder

Ryder System, Inc., commonly known as Ryder, is an American transportation and logistics company. It is especially known for its fleet of commercial rental trucks.

Ryder specializes in fleet management, supply chain management, and transp ...

'' (1928).

During the 1930s, Barnes spent time in England, Paris, New York, and North Africa. It was during this restless time that she wrote and published ''Nightwood''. In October 1939, after nearly two decades living mostly in Europe, Barnes returned to New York. She published her last major work, the verse play ''The Antiphon

''The Antiphon'' (1958) is a three-act verse tragedy by Djuna Barnes. Set in England in 1939 after the beginning of World War Two, the drama presents the Hobbs family reunion in the family's ancestral home, Burley Hall. The play features many of ...

'', in 1958, and she died in her apartment at Patchin Place, Greenwich Village in June 1982.

Life and writing

Early life (1892–1912)

Barnes was born in a log cabin on Storm King Mountain, nearCornwall-on-Hudson, New York

Cornwall-on-Hudson is a riverfront village in the town of Cornwall, Orange County, New York, United States. It lies on the west bank of the Hudson River, approximately north of New York City.

The population as of the 2010 census was 3,018. ...

. Her paternal grandmother Zadel Barnes was a writer, journalist, and Women's Suffrage

Women's suffrage is the right of women to vote in elections. Beginning in the start of the 18th century, some people sought to change voting laws to allow women to vote. Liberal political parties would go on to grant women the right to vot ...

activist who had once hosted an influential literary salon

A salon is a gathering of people held by an inspiring host. During the gathering they amuse one another and increase their knowledge through conversation. These gatherings often consciously followed Horace's definition of the aims of poetry, "ei ...

. Her father, Wald Barnes (born Henry Aaron Budington), was an unsuccessful composer, musician, and painter. An advocate of polygamy

Crimes

Polygamy (from Late Greek (') "state of marriage to many spouses") is the practice of marrying multiple spouses. When a man is married to more than one wife at the same time, sociologists call this polygyny. When a woman is marr ...

, he married Barnes's mother Elizabeth J. Barnes (née Chappell) in 1889; his mistress Frances "Fanny" Clark moved in with them in 1897, when Barnes was five. They had eight children (five from Elizabeth: sons Thurn, Zendon, Saxon and Shangar and daughter Djuna; four from Fanny: sons Duane and Brian and daughters Muriel and Sheila), whom Wald made little effort to support financially. One half-sibling died in childhood. Zadel, who believed her son was a misunderstood artistic genius, struggled to provide for the entire family, supplementing her diminishing income by writing begging letters to friends and acquaintances.

As the second oldest child, Barnes spent much of her childhood helping care for siblings and half-siblings. She received her early education at home, mostly from her father and grandmother, who taught her writing, art, and music but neglected subjects such as math and spelling. She claimed to have had no formal schooling at all; some evidence suggests that she was enrolled in public school for a time after age ten, though her attendance was inconsistent.

It is possible that at the age of 16 she was raped, either by a neighbor with the knowledge and consent of her father, or possibly by her father. However, these are rumors and unconfirmed by Barnes, who never managed to complete her autobiography. What is known is that Barnes and her father continued to write warm letters to one another until his death in 1934. Barnes does refer to a rape obliquely in her first novel ''Ryder'' and more directly in her furious final play ''The Antiphon''. Sexually explicit references in correspondence from her grandmother, with whom she shared a bed for years, suggest incest, or overly familiar teasing, but Zadel—dead for 40 years by the time ''The Antiphon'' was written—was left out of its indictments. Shortly before her 18th birthday she reluctantly "married" Fanny Clark's brother Percy Faulkner in a private ceremony without benefit of clergy. He was 52. The match had been strongly promoted by her father, grandmother, mother, and brother, but she stayed with him for no more than two months.

New York City (1912–1921)

In 1912 Barnes's family, facing financial ruin, split up. Elizabeth moved to New York City with Barnes and three of her brothers, then filed for divorce, freeing Wald to marry Fanny Clark. The move gave Barnes an opportunity to study art formally for the first time; she attended thePratt Institute

Pratt Institute is a private university with its main campus in Brooklyn, New York. It has a satellite campus in Manhattan and an extension campus in Utica, New York at the Munson-Williams-Proctor Arts Institute. The school was founded in 1887 ...

for about six months from 1912 to 1913 and at the Art Student's League of New York from 1915 to 1916, but the need to support herself and her family—a burden that fell largely on her—soon drove her to leave school and take a job as a reporter at the ''Brooklyn Daily Eagle

:''This article covers both the historical newspaper (1841–1955, 1960–1963), as well as an unrelated new Brooklyn Daily Eagle starting 1996 published currently''

The ''Brooklyn Eagle'' (originally joint name ''The Brooklyn Eagle'' and ''King ...

''. Upon arriving at the ''Daily Eagle'', Barnes declared, "I can draw and write, and you'd be a fool not to hire me", words that were inscribed inside the Brooklyn Museum

The Brooklyn Museum is an art museum located in the New York City borough of Brooklyn. At , the museum is New York City's second largest and contains an art collection with around 1.5 million objects. Located near the Prospect Heights, Cro ...

.

Over the next few years her work appeared in almost every newspaper in New York, including the ''New York Press

''New York Press'' was a free alternative weekly in New York City, which was published from 1988 to 2011.

The ''Press'' strove to create a rivalry with the '' Village Voice''. ''Press'' editors claimed to have tried to hire away writer Nat Hen ...

'', ''The World'' and ''McCall's''; she wrote interviews, features, theatre reviews, and a variety of news stories, often illustrating them with her own drawings. She also published short fiction in the ''New York Morning Telegraph''s Sunday supplement and in the pulp magazine

Pulp magazines (also referred to as "the pulps") were inexpensive fiction magazines that were published from 1896 to the late 1950s. The term "pulp" derives from the cheap wood pulp paper on which the magazines were printed. In contrast, magazine ...

''All-Story Cavalier Weekly''.

Much of Barnes's journalism was subjective and experiential. Writing about a conversation with James Joyce

James Augustine Aloysius Joyce (2 February 1882 – 13 January 1941) was an Irish novelist, poet, and literary critic. He contributed to the Modernism, modernist avant-garde movement and is regarded as one of the most influential and important ...

, she admitted to missing part of what he said because her attention had wandered, though she revered Joyce's writing. Interviewing the successful playwright Donald Ogden Stewart, she shouted at him for "roll ngover and find ngyourself famous" while other writers continued to struggle, then said she wouldn't mind dying; as her biographer Phillip Herring points out, this is "a depressing and perhaps unprecedented note on which to end an interview." For "The Girl and the Gorilla", published by ''New York World Magazine'' in October 1914 she has a conversation with Dinah, a female gorilla at the Bronx Zoo

The Bronx Zoo (also historically the Bronx Zoological Park and the Bronx Zoological Gardens) is a zoo within Bronx Park in the Bronx, New York. It is one of the largest zoos in the United States by area and is the largest metropolitan zoo in ...

.

For another article in ''New York World'' in 1914, she submitted to force-feeding

Force-feeding is the practice of feeding a human or animal against their will. The term ''gavage'' (, , ) refers to supplying a substance by means of a small plastic feeding tube passed through the nose ( nasogastric) or mouth (orogastric) into ...

, a technique then being used on hunger-striking suffragists

Suffrage, political franchise, or simply franchise, is the right to vote in public, political elections and referendums (although the term is sometimes used for any right to vote). In some languages, and occasionally in English, the right to v ...

. Barnes wrote "If I, play acting, felt my being burning with revolt at this brutal usurpation of my own functions, how they who actually suffered the ordeal in its acutest horror must have flamed at the violation of the sanctuaries of their spirits." She concluded "I had shared the greatest experience of the bravest of my sex."Mills, 163–166.

While she mocked conservative suffrage activist Carrie Chapman Catt

Carrie Chapman Catt (; January 9, 1859 Fowler, p. 3 – March 9, 1947) was an American women's suffrage leader who campaigned for the Nineteenth Amendment to the United States Constitution, which gave U.S. women the right to vote in 1920. Catt ...

when Catt admonished would-be suffrage orators never to "hold a militant pose", or wear "a dress that shows your feet in front", Barnes was supportive of progressive suffragists. Barnes suggested that Catt's conservatism was an obstacle to the suffrage movement when Catt tried to ostracize fellow suffragists Alice Paul

Alice Stokes Paul (January 11, 1885 – July 9, 1977) was an American Quaker, suffragist, feminist, and women's rights activist, and one of the main leaders and strategists of the campaign for the Nineteenth Amendment to the U.S. Constitution, w ...

and Lucy Burns

Lucy Burns (July 28, 1879 – December 22, 1966) was an American suffragist and women's rights advocate.Bland, 1981 (p. 8) She was a passionate activist in the United States and the United Kingdom, who joined the militant suffragettes. Burns ...

, who sought the vote for women through media attention directed at their strikes and non-violent protesting. It was their mistreatment that motivated Barnes to experience for herself the torture of being force-fed.

Barnes immersed herself in risky situations in order to access experiences that a previous generation of homebound women had been denied. Writing about the traditionally masculine domain of boxing

Boxing (also known as "Western boxing" or "pugilism") is a combat sport in which two people, usually wearing protective gloves and other protective equipment such as hand wraps and mouthguards, throw punches at each other for a predetermined ...

from the ringside, Barnes explored boxing as a window into women's modern identities. In 1914, she first posed the question "What do women want at a fight?" in an article titled "My Sisters and I at a New York Prizefight" published in ''New York World'' magazine. According to Irene Gammel

Irene Gammel is a Canadian literary historian, biographer, and curator. She has published numerous books including ''Baroness Elsa'', a groundbreaking cultural biography of New York Dada artist and poet Baroness Elsa von Freytag-Loringhoven, and ...

, "Barnes' essay effectively begins to unravel an entire cultural history of repression for women". Barnes's interest in boxing continued into 1915 when she interviewed heavyweight champion Jess Willard

Jess Myron Willard (December 29, 1881 – December 15, 1968) was an American world heavyweight boxing champion billed as the Pottawatomie Giant who knocked out Jack Johnson in April 1915 for the heavyweight title. Willard was known for size rat ...

.

In 1915 Barnes moved out of her family's flat to an apartment in Greenwich Village, where she entered a thriving Bohemian

Bohemian or Bohemians may refer to:

*Anything of or relating to Bohemia

Beer

* National Bohemian, a brand brewed by Pabst

* Bohemian, a brand of beer brewed by Molson Coors

Culture and arts

* Bohemianism, an unconventional lifestyle, origin ...

community of artists and writers. Among her social circle were Edmund Wilson

Edmund Wilson Jr. (May 8, 1895 – June 12, 1972) was an American writer and literary critic who explored Freudian and Marxist themes. He influenced many American authors, including F. Scott Fitzgerald, whose unfinished work he edited for publi ...

, Berenice Abbott

Berenice Alice Abbott (July 17, 1898 – December 9, 1991) was an American photographer best known for her portraits of between-the-wars 20th century cultural figures, New York City photographs of architecture and urban design of the 1930s, and ...

, and the Dadaist

Dada () or Dadaism was an art movement of the European avant-garde in the early 20th century, with early centres in Zürich, Switzerland, at the Cabaret Voltaire (in 1916). New York Dada began c. 1915, and after 1920 Dada flourished in Paris ...

artist and poet Elsa von Freytag-Loringhoven

Elsa Baroness von Freytag-Loringhoven (née Else Hildegard Plötz; (12 July 1874 – 14 December 1927) was a German-born avant-garde visual artist and poet, who was active in Greenwich Village, New York, from 1913 to 1923, where her radical self ...

, whose biography Barnes tried to write but never finished. She came into contact with Guido Bruno

Guido Bruno (1884–1942) was a well-known Greenwich Village character, and small press publisher and editor, sometimes called "the Barnum of Bohemia."

He was based at his "Garret on Washington Square" where for an admission fee tourists cou ...

, an entrepreneur and promoter who published magazines and chapbook

A chapbook is a small publication of up to about 40 pages, sometimes bound with a saddle stitch.

In early modern Europe a chapbook was a type of printed street literature. Produced cheaply, chapbooks were commonly small, paper-covered bookle ...

s from his garret on Washington Square. Bruno had a reputation for unscrupulousness, and was often accused of exploiting Greenwich Village residents for profit—he used to charge tourists admission to watch Bohemians paint—but he was a strong opponent of censorship and was willing to risk prosecution by publishing Barnes's 1915 collection of "rhythms and drawings"

Despite a description of sex between women in the first poem, the book was never legally challenged; the passage seems explicit now, but at a time when lesbianism was virtually invisible in American culture, the New York Society for the Suppression of Vice

The New York Society for the Suppression of Vice (NYSSV or SSV) was an institution dedicated to supervising the morality of the public, founded in 1873. Its specific mission was to monitor compliance with state laws and work with the courts and di ...

may not have understood its imagery. Others were not as naïve, and Bruno was able to cash in on the book's reputation by raising the price from fifteen to fifty cents and pocketing the difference. Twenty years later Barnes used Bruno as one of the models for Felix Volkbein in ''Nightwood'', caricaturing his pretensions to nobility and his habit of bowing down before anyone titled or important.

Barnes was a member of the Provincetown Players

The Provincetown Players was a collective of artists, writers, intellectuals, and amateur theater enthusiasts. Under the leadership of the husband and wife team of George Cram “Jig” Cook and Susan Glaspell from Iowa, the Players produced two ...

, an amateur theatrical collective whose emphasis on artistic rather than commercial success meshed well with her own values. The Players' Greenwich Village theater was a converted stable with bench seating and a tiny stage; according to Barnes it was "always just about to be given back to the horses." Yet it played a significant role in the development of American drama, featuring works by Susan Glaspell

Susan Keating Glaspell (July 1, 1876 – July 28, 1948) was an American playwright, novelist, journalist and actress. With her husband George Cram Cook, she founded the Provincetown Players, the first modern American theatre company.

First know ...

, Edna St. Vincent Millay, Wallace Stevens

Wallace Stevens (October 2, 1879 – August 2, 1955) was an American modernist poet. He was born in Reading, Pennsylvania, educated at Harvard and then New York Law School, and spent most of his life working as an executive for an insurance compa ...

, and Theodore Dreiser

Theodore Herman Albert Dreiser (; August 27, 1871 – December 28, 1945) was an American novelist and journalist of the naturalist school. His novels often featured main characters who succeeded at their objectives despite a lack of a firm mora ...

, as well as launching the career of Eugene O'Neill

Eugene Gladstone O'Neill (October 16, 1888 – November 27, 1953) was an American playwright and Nobel laureate in literature. His poetically titled plays were among the first to introduce into the U.S. the drama techniques of realism, earli ...

. Three one-act plays by Barnes were produced there in 1919 and 1920; a fourth, ''The Dove'', premiered at Smith College in 1925, and a series of short closet drama

A closet drama is a play that is not intended to be performed onstage, but read by a solitary reader or sometimes out loud in a large group. The contrast between closet drama and classic "stage" dramas dates back to the late eighteenth century. Al ...

s were published in magazines, some under Barnes's pseudonym Lydia Steptoe.

These plays show the strong influence of the Irish playwright J. M. Synge

Edmund John Millington Synge (; 16 April 1871 – 24 March 1909) was an Irish playwright, poet, writer, collector of folklore, and a key figure in the Irish Literary Revival. His best known play ''The Playboy of the Western World'' was poorly r ...

; she was drawn to both the poetic quality of Synge's language and the pessimism of his vision. Critics have found them derivative, particularly those in which she tried to imitate Synge's Irish dialect, and Barnes may have agreed, since in later years she dismissed them as mere juvenilia

Juvenilia are literary, musical or artistic works produced by authors during their youth. Written juvenilia, if published at all, usually appears as a retrospective publication, some time after the author has become well known for later works.

...

. Yet in their content, these stylized and enigmatic early plays are more experimental than those of her fellow playwrights at Provincetown. A ''New York Times'' review by Alexander Woollcott

Alexander Humphreys Woollcott (January 19, 1887 – January 23, 1943) was an American drama critic and commentator for ''The New Yorker'' magazine, a member of the Algonquin Round Table, an occasional actor and playwright, and a prominent radio p ...

of her play ''Three From the Earth'' called it a demonstration of "how absorbing and essentially dramatic a play can be without the audience ever knowing what, if anything, the author is driving at ... The spectators sit with bated breath listening to each word of a playlet of which the darkly suggested clues leave the mystery unsolved."

Greenwich Village in the 1910s was known for its atmosphere of sexual as well as intellectual freedom. Barnes was unusual among Villagers in having been raised with a philosophy of free love

Free love is a social movement that accepts all forms of love. The movement's initial goal was to separate the state from sexual and romantic matters such as marriage, birth control, and adultery. It stated that such issues were the concern ...

, espoused both by her grandmother and her father. Her father's idiosyncratic vision had included a commitment to unlimited procreation, which she strongly rejected; criticism of childbearing would become a major theme in her work. She did, however, retain sexual freedom as a value. In the 1930s she told Antonia White that "she had no feeling of guilt whatever about sex, about going to bed with any man or woman she wanted"; correspondence indicates that by the time she was 21 her family was well aware of her bisexuality, and she had a number of affairs with both men and women during her Greenwich Village years.

Of these, the most important was probably her engagement to

Of these, the most important was probably her engagement to Ernst Hanfstaengl

Ernst Franz Sedgwick Hanfstaengl (; 2 February 1887 – 6 November 1975) was a German-American businessman and close friend of Adolf Hitler. He eventually fell out of favour with Hitler and defected from Nazi Germany to the United States. He lat ...

, a Harvard graduate who ran the American branch of his family's art publishing house. Hanfstaengl had once given a piano concert at the White House and was a friend of then-New York State Senator Franklin Delano Roosevelt

Franklin Delano Roosevelt (; ; January 30, 1882April 12, 1945), often referred to by his initials FDR, was an American politician and attorney who served as the 32nd president of the United States from 1933 until his death in 1945. As the ...

, but he became increasingly angered by anti-German sentiment in the United States during World War I. In 1916, he told Barnes he wanted a German wife; the painful breakup became the basis of a deleted scene in ''Nightwood''. He later returned to Germany and became a close associate of Adolf Hitler

Adolf Hitler (; 20 April 188930 April 1945) was an Austrian-born German politician who was dictator of Germany from 1933 until his death in 1945. He rose to power as the leader of the Nazi Party, becoming the chancellor in 1933 and the ...

. Starting in 1916 or 1917, she lived with a socialist

Socialism is a left-wing economic philosophy and movement encompassing a range of economic systems characterized by the dominance of social ownership of the means of production as opposed to private ownership. As a term, it describes the ...

philosopher and critic named Courtenay Lemon, whom she referred to as her common-law husband, but this too ended, for reasons that are unclear. She also had a passionate romantic relationship with Mary Pyne, a reporter for the ''New York Press'' and fellow member of the Provincetown Players. Pyne died of tuberculosis in 1919, attended by Barnes until the end.

Paris (1921–1930)

In the 1920s, Paris was the center ofmodernism

Modernism is both a philosophical and arts movement that arose from broad transformations in Western society during the late 19th and early 20th centuries. The movement reflected a desire for the creation of new forms of art, philosophy, an ...

in art and literature. Barnes first traveled there in 1921 on an assignment for ''McCall's''. She interviewed her fellow expatriate

An expatriate (often shortened to expat) is a person who resides outside their native country. In common usage, the term often refers to educated professionals, skilled workers, or artists taking positions outside their home country, either ...

writers and artists for U.S. periodicals and soon became a well-known figure on the local scene; her black cloak and her acerbic wit are remembered in many memoirs of the time. Even before her first novel was published, her literary reputation was already high, largely on the strength of her story "A Night Among the Horses," which was published in ''The Little Review'' and reprinted in her 1923 collection ''A Book''. She was part of the inner circle of the influential salon hostess Natalie Barney

Natalie Clifford Barney (October 31, 1876 – February 2, 1972) was an American writer who hosted a literary salon at her home in Paris that brought together French and international writers. She influenced other authors through her salon and a ...

, who became a lifelong friend and patron, as well as the central figure in Barnes's satiric chronicle of Paris lesbian life, ''Ladies Almanack.'' The most important relationship of Barnes's Paris years was with the artist Thelma Wood

Thelma Ellen Wood (July 3, 1901 – December 10, 1970) was an American artist, specialising in the traditional fine line drawing technique known as Silverpoint. She was noted for her hectic private life, and her lesbian relationship with Djuna B ...

. Wood was a Kansas native who had come to Paris to become a sculptor, but at Barnes's suggestion took up silverpoint instead, producing drawings of animals and plants that one critic compared to Henri Rousseau

Henri Julien Félix Rousseau (; 21 May 1844 – 2 September 1910)

at the Boulevard Saint-Germain Boulevard Saint-Germain () is a major street in Paris on the Rive Gauche of the Seine. It curves in a 3.5-kilometre (2.1 miles) arc from the Pont de Sully in the east (the bridge at the edge of Île Saint-Louis) to the Pont de la Concorde ( ...

. Another close friendship that developed during this time was with the Dada artist Baroness Elsa von Freytag-Loringhoven, with whom Barnes began an intensive correspondence in 1923. "Where Wood gave Barnes a doll as a gift to represent their symbolic love child, the Baroness proposed an erotic marriage whose love-child would be their book." From Paris, Barnes supported the Baroness in Berlin with money, clothing, and magazines. She also collected the Baroness's poems and letters.

Barnes arrived in Paris with a letter of introduction to at the Boulevard Saint-Germain Boulevard Saint-Germain () is a major street in Paris on the Rive Gauche of the Seine. It curves in a 3.5-kilometre (2.1 miles) arc from the Pont de Sully in the east (the bridge at the edge of Île Saint-Louis) to the Pont de la Concorde ( ...

James Joyce

James Augustine Aloysius Joyce (2 February 1882 – 13 January 1941) was an Irish novelist, poet, and literary critic. He contributed to the Modernism, modernist avant-garde movement and is regarded as one of the most influential and important ...

, whom she interviewed for ''Vanity Fair'' and who became a friend. The headline of her ''Vanity Fair'' interview billed him as "the man who is, at present, one of the more significant figures in literature," but her personal reaction to ''Ulysses'' was less guarded: "I shall never write another line ... Who has the nerve to after that?" It may have been reading Joyce that led Barnes to turn away from the late 19th century Decadent

The word decadence, which at first meant simply "decline" in an abstract sense, is now most often used to refer to a perceived decay in standards, morals, dignity, religious faith, honor, discipline, or skill at governing among the members of ...

and Aesthetic

Aesthetics, or esthetics, is a branch of philosophy that deals with the nature of beauty and taste, as well as the philosophy of art (its own area of philosophy that comes out of aesthetics). It examines aesthetic values, often expressed t ...

influences o''The Book of Repulsive Women''

toward the modernist experimentation of her later work. They differed, however, on the proper subject of literature; Joyce thought writers should focus on commonplace subjects and make them extraordinary, while Barnes was always drawn to the unusual, even the grotesque. Then, too, her own life was an extraordinary subject. Her autobiographical first novel ''Ryder'' would not only present readers with the difficulty of deciphering its shifting literary styles—a technique inspired by ''Ulysses''—but also with the challenge of piecing together the history of an unconventional polygamous household, far removed from most readers' expectations and experience. Despite the difficulties of the text, ''Ryder''s bawdiness drew attention, and it briefly became a ''New York Times'' bestseller. Its popularity caught the publisher unprepared; a first edition of 3,000 sold out quickly, but by the time more copies made it into bookstores, public interest in the book had died down. Still, the advance allowed Barnes to buy a new apartment on Rue Saint-Romain, where she lived with Thelma Wood starting in September 1927. The move made them neighbors of

Mina Loy

Mina Loy (born Mina Gertrude Löwy; 27 December 1882 – 25 September 1966) was a British-born artist, writer, poet, playwright, novelist, painter, designer of lamps, and bohemian. She was one of the last of the first-generation modernists to ...

, a friend of Barnes's since Greenwich Village days, who appeared in ''Ladies Almanack'' as Patience Scalpel, the sole heterosexual character, who "could not understand Women and their Ways."

Due to its subject matter, ''Ladies Almanack'' was published in a small, privately printed edition under the pseudonym "A Lady of Fashion." Copies were sold on the streets of Paris by Barnes and her friends, and Barnes managed to smuggle a few into the United States to sell. A bookseller, Edward Titus, offered to carry ''Ladies Almanack'' in his store in exchange for being mentioned on the title page, but when he demanded a share of the royalties on the entire print run, Barnes was furious. She later gave the name Titus to the abusive father in ''The Antiphon''.

Barnes dedicated ''Ryder'' and ''Ladies Almanack'' to Thelma Wood, but the year both books were published—1928—was also the year that she and Wood separated. Barnes had wanted their relationship to be monogamous, but had discovered that Wood wanted her "along with the rest of the world." Wood had a worsening dependency on alcohol, and she spent her nights drinking and seeking out casual sex partners; Barnes would search the cafés for her, often winding up equally drunk. Barnes broke up with Wood over her involvement with heiress Henriette McCrea Metcalf (1888–1981), who would be scathingly portrayed in ''Nightwood'' as Jenny Petherbridge.

1930s

Much of ''Nightwood'' was written during the summers of 1932 and 1933, while Barnes was staying at Hayford Hall, a country manor inDevon

Devon ( , historically known as Devonshire , ) is a ceremonial and non-metropolitan county in South West England. The most populous settlement in Devon is the city of Plymouth, followed by Devon's county town, the city of Exeter. Devo ...

rented by the art patron Peggy Guggenheim

Marguerite "Peggy" Guggenheim ( ; August 26, 1898 – December 23, 1979) was an American art collector, bohemian and socialite. Born to the wealthy New York City Guggenheim family, she was the daughter of Benjamin Guggenheim, who went down with ...

. Fellow guests included Antonia White

Antonia White (born Eirene Adeline Botting; 31 March 1899 – 10 April 1980) was a British writer and translator, known primarily for ''Frost in May'', a semi-autobiographical novel set in a convent school. It was the first book reissued by Virag ...

, John Ferrar Holms

John Ferrar Holms (1897–1934) was a British literary critic.

Early life

He was born in India to a British civil servant and an Irish mother. Holms was educated at Rugby School and Sandhurst. He was commissioned in 1915 as a second lieutenant ...

, and the novelist and poet Emily Coleman

Emily Holmes Coleman (1899–1974) was an American born writer, and a lifelong compulsive diary keeper. She also wrote a single novel, '' The Shutter of Snow'' (1930). This novel, about a woman who spends time in a mental hospital after the birth ...

. Evenings at the manor—nicknamed "Hangover Hall" by its residents—often featured a party game called Truth that encouraged brutal frankness, creating a tense emotional atmosphere. Barnes was afraid to leave her work in progress unattended because the volatile Coleman, having told Barnes one of her secrets, had threatened to burn the manuscript if Barnes revealed it. But once she had read the book, Coleman became its champion. Her critiques of successive drafts led Barnes to make major structural changes, and when publisher after publisher rejected the manuscript, it was Coleman who pressed T. S. Eliot, then an editor at Faber and Faber

Faber and Faber Limited, usually abbreviated to Faber, is an independent publishing house in London. Published authors and poets include T. S. Eliot (an early Faber editor and director), W. H. Auden, Margaret Storey, William Golding, Samuel ...

, to read it.

Faber published the book in 1936. Though reviews treated it as a major work of art, the book did not sell well. Barnes received no advance from Faber and the first royalty statement was for only £43; the U.S. edition published by Harcourt, Brace

Harcourt () was an American publishing firm with a long history of publishing fiction and nonfiction for adults and children. The company was last based in San Diego, California, with editorial/sales/marketing/rights offices in New York City a ...

the following year fared no better. Barnes had published little journalism in the 1930s and was largely dependent on Peggy Guggenheim's financial support. She was constantly ill and drank more and more heavily—according to Guggenheim, she accounted for a bottle of whiskey per day. In February 1939 she checked into a hotel in London and attempted suicide. Guggenheim funded hospital visits and doctors, but finally lost patience and sent her back to New York. There she shared a single room with her mother, who coughed all night and who kept reading her passages from Mary Baker Eddy

Mary Baker Eddy (July 16, 1821 – December 3, 1910) was an American religious leader and author who founded The Church of Christ, Scientist, in New England in 1879. She also founded ''The Christian Science Monitor'', a Pulitzer Prize-winning se ...

, having converted to Christian Science

Christian Science is a set of beliefs and practices associated with members of the Church of Christ, Scientist. Adherents are commonly known as Christian Scientists or students of Christian Science, and the church is sometimes informally known ...

. In March 1940, her family sent her to a sanatorium in upstate New York to dry out. Furious, Barnes began to plan a biography of her family, writing to Emily Coleman that "there is no reason any longer why I should feel for them in any way but hate." This idea would eventually come to fruition in her play ''The Antiphon''. After she returned to New York City, she quarreled bitterly with her mother and was thrown out on the street.

Return to Greenwich Village (1940–1982)

Left with nowhere else to go, Barnes stayed at Thelma Wood's apartment while Wood was out of town, then spent two months on a working ranch in Arizona withEmily Coleman

Emily Holmes Coleman (1899–1974) was an American born writer, and a lifelong compulsive diary keeper. She also wrote a single novel, '' The Shutter of Snow'' (1930). This novel, about a woman who spends time in a mental hospital after the birth ...

and Coleman's lover Jake Scarborough. She returned to New York and, in September, moved into the small apartment at 5 Patchin Place

Patchin Place is a gated cul-de-sac located off of 10th Street between Greenwich Avenue and the Avenue of the Americas (Sixth Avenue) in the Greenwich Village neighborhood of Manhattan, New York City. Its ten 3-storyNew York City Landmarks P ...

in Greenwich Village where she would spend the last 41 years of her life. Throughout the 1940s, she continued to drink and wrote virtually nothing. Guggenheim, despite misgivings, provided her with a small stipend, and Coleman, who could ill afford it, sent US$20 per month (about $310 in 2011). In 1943, Barnes was included in Peggy Guggenheim

Marguerite "Peggy" Guggenheim ( ; August 26, 1898 – December 23, 1979) was an American art collector, bohemian and socialite. Born to the wealthy New York City Guggenheim family, she was the daughter of Benjamin Guggenheim, who went down with ...

's show '' Exhibition by 31 Women'' at the Art of This Century gallery in New York.

In 1946, she worked for Henry Holt as a manuscript reader, but her reports were invariably caustic, and she was fired.

In 1950, realizing that alcoholism had made it impossible for her to function as an artist, Barnes stopped drinking in order to begin work on her verse play ''The Antiphon''. The play drew heavily on her own family history, and the writing was fueled by anger; she said "I wrote ''The Antiphon'' with clenched teeth, and I noted that my handwriting was as savage as a dagger." When he read the play, her brother Thurn accused her of wanting "revenge for something long dead and to be forgotten". Barnes, in the margin of his letter, described her motive as "justice", and next to "dead" she inscribed, "not dead".

After ''The Antiphon'', Barnes returned to writing poetry, which she worked and reworked, producing as many as 500 drafts. She wrote eight hours per day despite a growing list of health problems, including arthritis so severe that she had difficulty even sitting at her typewriter or turning on her desk lamp. Many of these poems never were finalized, and only a few were published in her lifetime.

During her Patchin Place years, Barnes became a notorious recluse, intensely suspicious of anyone she did not know well. E.E. Cummings

Edward Estlin Cummings, who was also known as E. E. Cummings, e. e. cummings and e e cummings (October 14, 1894 - September 3, 1962), was an American poet, painter, essayist, author and playwright. He wrote approximately 2,900 poems, two autobi ...

, who lived across the street, checked on her periodically by shouting out his window "Are you still alive, Djuna?" Bertha Harris

Bertha Harris (December 17, 1937 – May 22, 2005) was an American lesbian novelist. She is highly regarded by critics and admirers, but her novels are less familiar to the broader public.

Personal life

Bertha Anne Harris was born in Fay ...

put roses in her mailbox, but never succeeded in meeting her; Carson McCullers

Carson McCullers (February 19, 1917 – September 29, 1967) was an American novelist, short-story writer, playwright, essayist, and poet. Her first novel, '' The Heart Is a Lonely Hunter'' (1940), explores the spiritual isolation of misfits ...

camped on her doorstep, but Barnes only called down "Whoever is ringing this bell, please go the hell away." Anaïs Nin

Angela Anaïs Juana Antolina Rosa Edelmira Nin y Culmell (February 11, 1903 – January 14, 1977; , ) was a French-born American diarist, essayist, novelist, and writer of short stories and erotica. Born to Cuban parents in France, Nin was the d ...

was an ardent fan of her work, especially ''Nightwood''. She wrote to Barnes several times, inviting her to participate in a journal on women's writing, but received no reply. Barnes remained contemptuous of Nin and would cross the street to avoid her. Barnes was angry that Nin had named a character Djuna, and when the feminist bookstore Djuna Books opened in Greenwich Village, Barnes called to demand that the name be changed. Barnes had a lifelong affection for poet Marianne Moore

Marianne Craig Moore (November 15, 1887 – February 5, 1972) was an American modernist poet, critic, translator, and editor. Her poetry is noted for formal innovation, precise diction, irony, and wit.

Early life

Moore was born in Kirkwood ...

since she and Moore were young in the 1920s.

Although Barnes had other female lovers, in her later years she was known to claim "I am not a lesbian; I just loved Thelma."

Barnes was elected to the National Institute of Arts and Letters

The American Academy of Arts and Letters is a 300-member honor society whose goal is to "foster, assist, and sustain excellence" in American literature, music, and art. Its fixed number membership is elected for lifetime appointments. Its headqu ...

in 1961 and was awarded a senior fellowship by the National Endowment for the Arts

The National Endowment for the Arts (NEA) is an independent agency of the United States federal government that offers support and funding for projects exhibiting artistic excellence. It was created in 1965 as an independent agency of the federal ...

in 1981.

Barnes was the last surviving member of the first generation of English-language modernists when she died in her home in New York on June 18, 1982, six days after her 90th birthday.

Works

''The Book of Repulsive Women''

Barnes'schapbook

A chapbook is a small publication of up to about 40 pages, sometimes bound with a saddle stitch.

In early modern Europe a chapbook was a type of printed street literature. Produced cheaply, chapbooks were commonly small, paper-covered bookle ...

br>''The Book of Repulsive Women''(1915) collects eight "rhythms" and five drawings. The poems show the strong influence of late 19th century

Decadence

The word decadence, which at first meant simply "decline" in an abstract sense, is now most often used to refer to a perceived decay in standards, morals, dignity, religious faith, honor, discipline, or skill at governing among the members ...

, and the style of the illustrations resembles Aubrey Beardsley

Aubrey Vincent Beardsley (21 August 187216 March 1898) was an English illustrator and author. His black ink drawings were influenced by Japanese woodcuts, and depicted the grotesque, the decadent, and the erotic. He was a leading figure in the ...

's. The setting is New York City, and the subjects are all women: a cabaret singer, a woman seen through an open window from the elevated train

An elevated railway or elevated train (also known as an el train for short) is a rapid transit railway with the tracks above street level on a viaduct or other elevated structure (usually constructed from steel, cast iron, concrete, or bricks ...

, and, in the last poem, the corpses of two suicides in the morgue. The book describes women's bodies and sexuality in terms that have indeed struck many readers as repulsive, but, as with much of Barnes's work, the author's stance is ambiguous. Some critics read the poems as exposing and satirizing cultural attitudes toward women.

Barnes came to regard ''The Book of Repulsive Women'' as an embarrassment; she called the title "idiotic," left it out of her curriculum vitae, and even burned copies. But because the copyright had never been registered, she was unable to prevent it from being republished, and it became one of her most reprinted works.

''

Ryder

Ryder System, Inc., commonly known as Ryder, is an American transportation and logistics company. It is especially known for its fleet of commercial rental trucks.

Ryder specializes in fleet management, supply chain management, and transp ...

''

Barnes's novel ''Ryder

Ryder System, Inc., commonly known as Ryder, is an American transportation and logistics company. It is especially known for its fleet of commercial rental trucks.

Ryder specializes in fleet management, supply chain management, and transp ...

'' (1928) draws heavily on her childhood experiences in Cornwall-on-Hudson. It covers 50 years of history of the Ryder family: Sophia Grieve Ryder, like Zadel a former salon

Salon may refer to:

Common meanings

* Beauty salon, a venue for cosmetic treatments

* French term for a drawing room, an architectural space in a home

* Salon (gathering), a meeting for learning or enjoyment

Arts and entertainment

* Salon ( ...

hostess fallen into poverty; her idle son Wendell; his wife Amelia; his resident mistress Kate-Careless; and their children. Barnes appears as Wendell and Amelia's daughter Julie. The story has a large cast and is told from a variety of points of view; some characters appear as the protagonist of a single chapter only to disappear from the text entirely. Fragments of the Ryder family chronicle are interspersed with children's stories, songs, letters, poems, parables, and dreams. The book changes style from chapter to chapter, parodying writers from Chaucer

Geoffrey Chaucer (; – 25 October 1400) was an English poet, author, and civil servant best known for '' The Canterbury Tales''. He has been called the "father of English literature", or, alternatively, the "father of English poetry". He w ...

to Dante Gabriel Rossetti

Gabriel Charles Dante Rossetti (12 May 1828 – 9 April 1882), generally known as Dante Gabriel Rossetti (), was an English poet, illustrator, painter, translator and member of the Rossetti family. He founded the Pre-Raphaelite Brotherhoo ...

.

Both ''Ryder'' and ''Ladies Almanack'' abandon the Beardsleyesque style of her drawings for ''The Book of Repulsive Women'' in favor of a visual vocabulary borrowed from French folk art. Several illustrations are closely based on the engravings and woodcuts collected by Pierre Louis Duchartre and René Saulnier in the 1926 book ''L'Imagerie Populaire''—images that had been copied with variations since medieval times. The bawdiness of ''Ryders illustrations led the U.S. Postal Service to refuse to ship it, and several had to be left out of the first edition, including an image in which Sophia is seen urinating into a chamberpot

A chamber pot is a portable toilet, meant for nocturnal use in the bedroom. It was common in many cultures before the advent of indoor plumbing and flushing toilets.

Names and etymology

"Chamber" is an older term for bedroom. The chamber pot ...

and one in which Amelia and Kate-Careless sit by the fire knitting codpiece

A codpiece () is a triangular piece that attached to the front of men's hose, covering the fly. It may be held in place by ties or buttons. It was an important fashion item of European clothing during the 15th–16th centuries. In the modern er ...

s. Parts of the text were also expurgated. In an acerbic introduction, Barnes explained that the missing words and passages had been replaced with asterisks so that readers could see the "havoc" wreaked by censorship. A 1990 Dalkey Archive edition restored the missing drawings, but the original text was lost with the destruction of the manuscript in World War II.

''

Ladies Almanack

''Ladies Almanack'', its complete title being ''Ladies Almanack: showing their Signs and their Tides; their Moons and their Changes; the Seasons as it is with them; their Eclipses and Equinoxes; as well as a full Record of diurnal and nocturnal Dis ...

''

''Ladies Almanack

''Ladies Almanack'', its complete title being ''Ladies Almanack: showing their Signs and their Tides; their Moons and their Changes; the Seasons as it is with them; their Eclipses and Equinoxes; as well as a full Record of diurnal and nocturnal Dis ...

'' (1928) is a roman à clef

''Roman à clef'' (, anglicised as ), French for ''novel with a key'', is a novel about real-life events that is overlaid with a façade of fiction. The fictitious names in the novel represent real people, and the "key" is the relationship be ...

about a predominantly lesbian social circle centering on Natalie Clifford Barney

Natalie Clifford Barney (October 31, 1876 – February 2, 1972) was an American writer who hosted a literary salon at her home in Paris that brought together French and international writers. She influenced other authors through her salon and al ...

's salon in Paris. It is written in an archaic, Rabelaisian style, with Barnes's own illustrations in the style of Elizabethan

The Elizabethan era is the epoch in the Tudor period of the history of England during the reign of Queen Elizabeth I (1558–1603). Historians often depict it as the golden age in English history. The symbol of Britannia (a female personific ...

woodcuts.

Clifford Barney appears as Dame Evangeline Musset, "who was in her Heart one Grand Red Cross for the Pursuance, the Relief and the Distraction, of such Girls as in their Hinder Parts, and their Fore Parts, and in whatsoever Parts did suffer them most, lament Cruelly." " Pioneer and a Menace" in her youth, Dame Musset has reached "a witty and learned Fifty"; she rescues women in distress, dispenses wisdom, and upon her death is elevated to sainthood. Also appearing pseudonymously are Élisabeth de Gramont

Antoinette Corisande Élisabeth, Duchess of Clermont-Tonnerre (née de Gramont; 23 April 1875 – 6 December 1954) was a French writer of the early 20th century, best known for her long-term lesbian relationship with Natalie Clifford Barney, ...

, Romaine Brooks

Romaine Brooks (born Beatrice Romaine Goddard; May 1, 1874 – December 7, 1970) was an American painter who worked mostly in Paris and Capri. She specialized in portrait painting, portraiture and used a subdued tonal Palette (painting), palette ...

, Dolly Wilde

Dorothy Ierne Wilde, known as Dolly Wilde (11 July 1895 – 10 April 1941), was an English socialite, made famous by her family connections and her reputation as a witty conversationalist. Her charm and humour made her a popular guest at sa ...

, Radclyffe Hall

Marguerite Antonia Radclyffe Hall (12 August 1880 – 7 October 1943) was an English poet and author, best known for the novel ''The Well of Loneliness'', a groundbreaking work in lesbian literature. In adulthood, Hall often went by the name Jo ...

and her partner Una Troubridge

Una Vincenzo, Lady Troubridge (born Margot Elena Gertrude Taylor; 8 March 1887 – 24 September 1963) was a British sculptor and translator. She is best known as the long-time lesbian partner of Marguerite Radclyffe Hall, author of ''The W ...

, Janet Flanner

Janet Flanner (March 13, 1892 – November 7, 1978) was an American writer and pioneering narrative journalist who served as the Paris correspondent of ''The New Yorker'' magazine from 1925 until she retired in 1975.Yagoda, Ben ''About T ...

and Solita Solano

Solita Solano (October 30, 1888 – November 22, 1975), born Sarah Wilkinson, was an American writer, poet and journalist.

Biography

Early life

Sarah Wilkinson came from a middle-class family and attended the Emma Willard School in Troy, Ne ...

, and Mina Loy

Mina Loy (born Mina Gertrude Löwy; 27 December 1882 – 25 September 1966) was a British-born artist, writer, poet, playwright, novelist, painter, designer of lamps, and bohemian. She was one of the last of the first-generation modernists to ...

.

The obscure language, inside jokes, and ambiguity of ''Ladies Almanack'' have kept critics arguing about whether it is an affectionate satire or a bitter attack, but Barnes loved the book and reread it throughout her life.

''

Nightwood

''Nightwood'' is a 1936 novel by American author Djuna Barnes that was first published by publishing house Faber and Faber. It is one of the early prominent novels to portray explicit homosexuality between women, and as such can be considered ...

''

Barnes's reputation as a writer was made when ''Nightwood

''Nightwood'' is a 1936 novel by American author Djuna Barnes that was first published by publishing house Faber and Faber. It is one of the early prominent novels to portray explicit homosexuality between women, and as such can be considered ...

'' was published in England in 1936 in an expensive edition by Faber and Faber

Faber and Faber Limited, usually abbreviated to Faber, is an independent publishing house in London. Published authors and poets include T. S. Eliot (an early Faber editor and director), W. H. Auden, Margaret Storey, William Golding, Samuel ...

, and in America in 1937 by Harcourt, Brace and Company, with an added introduction by T.S. Eliot, Barnes's editor. The avant-garde novel, written under the patronage of Peggy Guggenheim, made Barnes famous in feminist circles.

The novel, set in Paris in the 1920s, revolves around the lives of five characters, two of whom are based on Barnes and Wood, and it reflects the circumstances surrounding the ending of their relationship. In his introduction, Eliot praises Barnes's style, which, while having "prose rhythm ... and the musical pattern which is not that of verse, is so good a novel that only sensibilities trained on poetry can wholly appreciate it."

Due to concerns about censorship, Eliot edited ''Nightwood'' to soften some language relating to sexuality and religion. An edition restoring these changes, edited by Cheryl J. Plumb, was published by Dalkey Archive Press in 1995.

Dylan Thomas

Dylan Marlais Thomas (27 October 1914 – 9 November 1953) was a Welsh poet and writer whose works include the poems " Do not go gentle into that good night" and " And death shall have no dominion", as well as the "play for voices" ''Und ...

described ''Nightwood'' as "one of the three great prose books ever written by a woman," and William Burroughs

William Seward Burroughs II (; February 5, 1914 – August 2, 1997) was an American writer and visual artist, widely considered a primary figure of the Beat Generation and a major postmodern author who influenced popular cultur ...

called it "one of the great books of the twentieth century." It was number 12 on a list of the top 100 gay books compiled by The Publishing Triangle in 1999.

''

The Antiphon

''The Antiphon'' (1958) is a three-act verse tragedy by Djuna Barnes. Set in England in 1939 after the beginning of World War Two, the drama presents the Hobbs family reunion in the family's ancestral home, Burley Hall. The play features many of ...

''

Barnes's verse play ''The Antiphon

''The Antiphon'' (1958) is a three-act verse tragedy by Djuna Barnes. Set in England in 1939 after the beginning of World War Two, the drama presents the Hobbs family reunion in the family's ancestral home, Burley Hall. The play features many of ...

'' (1958) is set in England in 1939. Jeremy Hobbs, in disguise as Jack Blow, has brought his family together at their ruined ancestral home, Burley Hall. His motive is never explicitly stated, but he seems to want to provoke a confrontation among the members of his family and force them to confront the truth about their past. His sister Miranda is a stage actress, now "out of patron and of money"; her materialistic brothers, Elisha and Dudley, see her as a threat to their financial well-being. Elisha and Dudley accuse their mother Augusta of complicity with their abusive father Titus Hobbs. They take advantage of Jeremy's absence to don animal masks and assault both women, making cruel and sexually suggestive remarks; Augusta treats this attack as a game. Jeremy returns with a doll house, a miniature version of the house in America where the children grew up. As she examines it, he charges her with making herself "a madam by submission" because she failed to prevent Titus from orchestrating Miranda's rape by "a travelling Cockney thrice erage." The last act finds Miranda and Augusta alone together. Augusta, at once disapproving and envious of her daughter's more liberated life, exchanges clothes with her daughter and wants to pretend she is young again, but Miranda refuses to enter into this play. When Augusta hears Elisha and Dudley driving away, she blames Miranda for their abandonment and beats her to death with a curfew

A curfew is a government order specifying a time during which certain regulations apply. Typically, curfews order all people affected by them to ''not'' be in public places or on roads within a certain time frame, typically in the evening and ...

bell, falling dead at her side from the exertion.

The play premiered in 1961 in Stockholm in a Swedish translation by Karl Ragnar Gierow

Karl Ragnar Knut Gierow (2 April 190430 October 1982) was a Swedish theater director, author and translator. Biography

Gierow was born and grew up in Helsingborg. He enrolled at Lund University in 1922, and received a licentiate degree in 1934.

...

and U.N. Secretary-General Dag Hammarskjöld

Dag Hjalmar Agne Carl Hammarskjöld ( , ; 29 July 1905 – 18 September 1961) was a Swedish economist and diplomat who served as the second Secretary-General of the United Nations from April 1953 until his death in a plane crash in September 196 ...

.

The play was translated in French and set at the Odeon Theater in Paris by the “Comedie Française” in March 1990.

''Creatures in an Alphabet''

Barnes's last book, ''Creatures in an Alphabet'' (1982), is a collection of short rhyming poems. The format suggests a children's book, but it contains enough allusiveness and advanced vocabulary to make it an unlikely read for a child: the entry for T quotes Blake's "The Tyger

"The Tyger" is a poem by the English poet William Blake, published in 1794 as part of his '' Songs of Experience'' collection and rising to prominence in the romantic period. The poem is one of the most anthologised in the English literary can ...

," a seal is compared to Jacques-Louis David

Jacques-Louis David (; 30 August 1748 – 29 December 1825) was a French painter in the Neoclassical style, considered to be the preeminent painter of the era. In the 1780s, his cerebral brand of history painting marked a change in taste away f ...

's portrait of Madame Récamier, and a braying donkey is described as "practicing '' solfeggio''." ''Creatures'' continues the themes of nature and culture found in Barnes's earlier work, and their arrangement as a bestiary reflects her longstanding interest in systems for organizing knowledge, such as encyclopedias and almanacs.

Unpublished non-fiction

During the 1920s and 1930s, Barnes made an effort to write a biography of Elsa von Freytag-Loringhoven and edited her poems for publication. Unsuccessful in finding a publisher for the Baroness's poetry, Barnes abandoned the project. After writing a number of chapter drafts of the biography, she abandoned that project, too, after submitting the first chapter toEmily Coleman

Emily Holmes Coleman (1899–1974) was an American born writer, and a lifelong compulsive diary keeper. She also wrote a single novel, '' The Shutter of Snow'' (1930). This novel, about a woman who spends time in a mental hospital after the birth ...

in 1939, whose response was not encouraging. Barnes's efforts at writing the biography are detailed in Irene Gammel

Irene Gammel is a Canadian literary historian, biographer, and curator. She has published numerous books including ''Baroness Elsa'', a groundbreaking cultural biography of New York Dada artist and poet Baroness Elsa von Freytag-Loringhoven, and ...

's ''Baroness Elsa'' biography.

Legacy

Barnes has been cited as an influence by writers as diverse asTruman Capote

Truman Garcia Capote ( ; born Truman Streckfus Persons; September 30, 1924 – August 25, 1984) was an American novelist, screenwriter, playwright and actor. Several of his short stories, novels, and plays have been praised as literary classics, ...

, William Goyen

Charles William Goyen (April 24, 1915 – August 30, 1983) was an American novelist, short story writer, playwright, poet, editor, and teacher. Born in a small town in East Texas, these roots would influence his work for his entire life.

In Worl ...

, Karen Blixen

Baroness Karen Christenze von Blixen-Finecke (born Dinesen; 17 April 1885 – 7 September 1962) was a Danish author who wrote works in Danish and English. She is also known under her pen names Isak Dinesen, used in English-speaking countrie ...

, John Hawkes, Bertha Harris

Bertha Harris (December 17, 1937 – May 22, 2005) was an American lesbian novelist. She is highly regarded by critics and admirers, but her novels are less familiar to the broader public.

Personal life

Bertha Anne Harris was born in Fay ...

, Dylan Thomas

Dylan Marlais Thomas (27 October 1914 – 9 November 1953) was a Welsh poet and writer whose works include the poems " Do not go gentle into that good night" and " And death shall have no dominion", as well as the "play for voices" ''Und ...

, David Foster Wallace

David Foster Wallace (February 21, 1962 – September 12, 2008) was an American novelist, short story writer, essayist, and university professor of English and creative writing. Wallace is widely known for his 1996 novel '' Infinite Jest'', whi ...

, and Anaïs Nin

Angela Anaïs Juana Antolina Rosa Edelmira Nin y Culmell (February 11, 1903 – January 14, 1977; , ) was a French-born American diarist, essayist, novelist, and writer of short stories and erotica. Born to Cuban parents in France, Nin was the d ...

. Writer Bertha Harris

Bertha Harris (December 17, 1937 – May 22, 2005) was an American lesbian novelist. She is highly regarded by critics and admirers, but her novels are less familiar to the broader public.

Personal life

Bertha Anne Harris was born in Fay ...

described her work as "practically the only available expression of lesbian culture we have in the modern western world" since Sappho.

Barnes's biographical notes and collection of manuscripts have been a major source for scholars who have brought the Baroness Elsa von Freytag-Loringhoven forth from the margins of Dada history. They were key in producing '' Body Sweats: The Uncensored Writings of Elsa von Freytag-Loringhoven'' (2011), the first major English collection of the baroness's poems, and a biography titled ''Baroness Elsa: Gender, Dada and Everyday Modernity'' (2002).

Fictional portrayals

Cynthia Grant andSvetlana Zylin

Svetlana Zylin (1948-2002) was a Belgian-born Canadian theatre director and playwright. She was also the founder of the Women's Theatre Collective in Vancouver, British Columbia.

Biography

Zylin was born in Belgium in 1948. Her family immigrat ...

co-wrote the play ''Djuna: What of the Night'' based on Barnes's life and works. The play premiered in 1991.

Emmanuelle Uzan played Barnes in a brief cameo role with no dialogue in Woody Allen

Heywood "Woody" Allen (born Allan Stewart Konigsberg; November 30, 1935) is an American film director, writer, actor, and comedian whose career spans more than six decades and multiple Academy Award-winning films. He began his career writing ...

's 2011 film ''Midnight in Paris

''Midnight in Paris'' is a 2011 fantasy comedy film written and directed by Woody Allen. Set in Paris, the film follows Gil Pender ( Owen Wilson), a screenwriter, who is forced to confront the shortcomings of his relationship with his materi ...

''.

Bibliography

''The Book of Repulsive Women: 8 Rhythms and 5 Drawings''

New York: Guido Bruno, 1915. *''A Book'' (1923) – revised versions published as: **''

A Night Among the Horses

A, or a, is the first letter and the first vowel of the Latin alphabet, used in the modern English alphabet, the alphabets of other western European languages and others worldwide. Its name in English is ''a'' (pronounced ), plural ''aes ...

'' (1929)

**''Spillway

A spillway is a structure used to provide the controlled release of water downstream from a dam or levee, typically into the riverbed of the dammed river itself. In the United Kingdom, they may be known as overflow channels. Spillways ensure th ...

'' (1962)

*''Ryder

Ryder System, Inc., commonly known as Ryder, is an American transportation and logistics company. It is especially known for its fleet of commercial rental trucks.

Ryder specializes in fleet management, supply chain management, and transp ...

'' (1928)

*''Ladies Almanack

''Ladies Almanack'', its complete title being ''Ladies Almanack: showing their Signs and their Tides; their Moons and their Changes; the Seasons as it is with them; their Eclipses and Equinoxes; as well as a full Record of diurnal and nocturnal Dis ...

'' (1928)

*''Nightwood

''Nightwood'' is a 1936 novel by American author Djuna Barnes that was first published by publishing house Faber and Faber. It is one of the early prominent novels to portray explicit homosexuality between women, and as such can be considered ...

'' (1936)

*''The Antiphon

''The Antiphon'' (1958) is a three-act verse tragedy by Djuna Barnes. Set in England in 1939 after the beginning of World War Two, the drama presents the Hobbs family reunion in the family's ancestral home, Burley Hall. The play features many of ...

'' (1958)

*''Selected Works'' (1962) – ''Spillway'', ''Nightwood'', and a revised version of ''The Antiphon''

*''Vagaries Malicieux: Two Stories'' (1974) – unauthorized publication

*''Creatures in an Alphabet'' (1982)

*''Smoke and Other Early Stories'' (1982)

*''I Could Never Be Lonely without a Husband: Interviews by Djuna Barnes'' (1987) – ed. A. Barry

*''New York'' (1989) – journalism

*''At the Roots of the Stars: The Short Plays'' (1995)

*''Collected Stories of Djuna Barnes'' (1996)

*''Poe's Mother: Selected Drawings'' (1996) – ed. and with an introduction by Douglas Messerli

Douglas Messerli (born May 30, 1947) is an American writer, professor, and publisher based in Los Angeles, California. In 1976, he started ''Sun & Moon'', a magazine of art and literature, which became Sun & Moon press, and later Green Intege ...

*''Discanto, poesie 1911–1982'', Roma, Edizione del Giano, 2004 a cura di Maura Del Serra

*''Collected Poems: With Notes Toward the Memoirs'' (2005) – ed. Phillip Herring and Osias Stutman

*''Vivid and Repulsive as the Truth: The Early Works of Djuna Barnes'' (2016) - ed. Katharine Maller

*''The Lydia Steptoe Stories'' (2019)

*''Biography of Julie von Bartmann'' (2020) - with an introduction by Douglas Messerli

Douglas Messerli (born May 30, 1947) is an American writer, professor, and publisher based in Los Angeles, California. In 1976, he started ''Sun & Moon'', a magazine of art and literature, which became Sun & Moon press, and later Green Intege ...

Notes

References

* * Altman, Meryl (1991). "''The Antiphon'': 'No Audience at All'?" Broe, ''Silence and Power'', 271–284. * * * * * Burke, Carolyn (1991). "'Accidental Aloofness': Barnes, Loy, and Modernism". In Broe, ''Silence and Power'', 67–79. * * * * * * * Gammel, Irene (2002).Baroness Elsa: Gender, Dada and Everyday Modernity

'' Cambridge, MA: MIT Press. * Gammel, Irene (2012).

Lacing up the Gloves: Women, Boxing and Modernity

" ''Cultural and Social History'' 9.3: 369–390. * * * * * * * Larabee, Ann (1991). "The Early Attic Stage of Djuna Barnes". In Broe, ''Silence and Power'', 37–44. * Marcus, Jane. "Mousemeat: Contemporary Reviews of ''Nightwood''". Broe, 195–204. * Reprinted from *Messerli, Douglas. Djuna Barnes: A Bibliography. New York: David Lewis, 1975. *Page, Chester (2007) MEMOIRS OF A CHARMED LIFE IN NEW YORK. Memories of Djuna Barnes. iUNIVERSE. * *Parsons, Deborah. "Djuna Barnes: Melancholic Modernism." ''The Cambridge Companion to the Modernist Novel.'' Ed. Morag Shiach. New York: Cambridge University Press. 165–177

Google Books

* Ponsot, Marie (1991). "A Reader's Ryder". In Broe, ''Silence and Power'', 94–112. * Retallack, Joan (1991). "One Acts: Early Plays of Djuna Barnes". In Broe, ''Silence and Power'', 46–52. * * * * *University of London. "First International Djuna Barnes Conference." Institute of English Studies, 2012.

External links

Archives

* hdl:1903.1/1512, Djuna Barnes papers (102 linear ft.) are housed at theHornbake Library

The University of Maryland Libraries is the largest university library in the Washington, D.C. - Baltimore area. The university's library system includes eight libraries: six are located on the College Park campus, while the Severn Library, an o ...

at the University of Maryland

The University of Maryland, College Park (University of Maryland, UMD, or simply Maryland) is a public land-grant research university in College Park, Maryland. Founded in 1856, UMD is the flagship institution of the University System of ...

* Barnes family papers (13 linear ft.) are housed at the Hornbake Library

The University of Maryland Libraries is the largest university library in the Washington, D.C. - Baltimore area. The university's library system includes eight libraries: six are located on the College Park campus, while the Severn Library, an o ...

at the University of Maryland

The University of Maryland, College Park (University of Maryland, UMD, or simply Maryland) is a public land-grant research university in College Park, Maryland. Founded in 1856, UMD is the flagship institution of the University System of ...

* Saxon Barnes papers (1.75 linear ft.) are housed at the Hornbake Library

The University of Maryland Libraries is the largest university library in the Washington, D.C. - Baltimore area. The university's library system includes eight libraries: six are located on the College Park campus, while the Severn Library, an o ...

at the University of Maryland

The University of Maryland, College Park (University of Maryland, UMD, or simply Maryland) is a public land-grant research university in College Park, Maryland. Founded in 1856, UMD is the flagship institution of the University System of ...

. Saxon Barnes was the brother of Djuna Barnes. His papers includes correspondence, photographs, and other materials of and by Djuna Barnes

Irwin Cohen collection

which consists of artwork, clippings, manuscripts, proofs, photographs, and publications by and about Djuna Barnes and her era at the

University of Maryland libraries

The University of Maryland Libraries is the largest university library in the Washington, D.C. - Baltimore area. The university's library system includes eight libraries: six are located on the College Park campus, while the Severn Library, an o ...

Emily Holmes Coleman papers

a

Special Collections, University of Delaware Library

Other links

*''James Joyce'' by Djuna Barnes: ''Vanity Fair'', March, 1922

— about the women of the

Left Bank

In geography, a bank is the land alongside a body of water. Different structures are referred to as ''banks'' in different fields of geography, as follows.

In limnology (the study of inland waters), a stream bank or river bank is the terra ...

Online works

''The Book of Repulsive Women''

a

A Celebration of Women Writers

The Confessions of Helen Westley

— an interview *

What Do You See, Madam?

— one of Barnes's early newspaper short stories * {{DEFAULTSORT:Barnes, Djuna 1892 births 1982 deaths American women novelists American women poets American satirists Anti-natalists Bisexual artists Bisexual women Bisexual writers Modernist women writers American LGBT journalists 20th-century American novelists 20th-century American women writers 20th-century American women artists Modernist writers American expatriates in France American LGBT poets American LGBT novelists LGBT people from New York (state) 20th-century American poets People from Orange County, New York Women satirists Women erotica writers Journalists from New York (state) Novelists from New York (state) American women non-fiction writers 20th-century American non-fiction writers 20th-century American journalists American women journalists Lost Generation writers 20th-century LGBT people Members of the American Academy of Arts and Letters