Detribalization on:

[Wikipedia]

[Google]

[Amazon]

Detribalization is the process by which persons who belong to a particular Indigenous

Detribalization is the process by which persons who belong to a particular Indigenous

From 1884 to 1885, European powers, along with the United States, convened at the Berlin Conference in order to settle colonial disputes throughout the

From 1884 to 1885, European powers, along with the United States, convened at the Berlin Conference in order to settle colonial disputes throughout the

In the seventeenth century, the

In the seventeenth century, the

Portuguese colonizers arrived on the eastern seaboard of South America in 1500 and had established permanent settlements in the interior regions of

Portuguese colonizers arrived on the eastern seaboard of South America in 1500 and had established permanent settlements in the interior regions of

Mexican anthropologist Guillermo Bonfil Batalla and other scholars have used the term "de-Indianization" to describe a "historical process through which populations that originally possessed a particular and distinctive identity, based upon their own culture, are forced to renounce that identity, with all the consequent changes in their social organization and culture.Bonfil Batalla 1996, p. 17-18. The process of de-Indianization in Mexico was a colonial project which largely succeeded, according to Bonfil Batalla, "in convincing large parts of the Mesoamerican population to renounce their identification as members of a specific Indian collectivity."Bonfil Batalla 1996, p. 24. He acknowledges how many Indigenous peoples throughout Mexico were historically expelled or displaced from their traditional territories, while others may have been exterminated, "as was the case with the Great Chichimeca of the arid north." These genocidal conditions had the effect of detribalizing many Indigenous people by subjecting them to "conditions that made continuity as a culturally different people impossible." Although this process has been referred to as "mixture" or ''

Mexican anthropologist Guillermo Bonfil Batalla and other scholars have used the term "de-Indianization" to describe a "historical process through which populations that originally possessed a particular and distinctive identity, based upon their own culture, are forced to renounce that identity, with all the consequent changes in their social organization and culture.Bonfil Batalla 1996, p. 17-18. The process of de-Indianization in Mexico was a colonial project which largely succeeded, according to Bonfil Batalla, "in convincing large parts of the Mesoamerican population to renounce their identification as members of a specific Indian collectivity."Bonfil Batalla 1996, p. 24. He acknowledges how many Indigenous peoples throughout Mexico were historically expelled or displaced from their traditional territories, while others may have been exterminated, "as was the case with the Great Chichimeca of the arid north." These genocidal conditions had the effect of detribalizing many Indigenous people by subjecting them to "conditions that made continuity as a culturally different people impossible." Although this process has been referred to as "mixture" or ''

The Spanish colonial period began under Jose de Oñate in 1598, who inflicted atrocities on Acoma Pueblo, killing "hundreds of Acomas, and burned houses and kivas." Ongoing resistance by Pueblo religious leaders propelled the Spanish to use missionaries in order to "convert the Indians to Catholicism" and thus encourage them to disidentify from their Pueblo community and cultural practices. Historians Deborah Lawrence and Jon Lawrence note that a new "form of slavery developed whereby Indians who were obtained by Hispanics through war or trade were taken into Spanish households as servants." These "detribalized Indian captives" were referred to as ''genízaros'' and eventually "managed to merge into the larger society over generations."

In the eighteenth century, the population of detribalized people in

The Spanish colonial period began under Jose de Oñate in 1598, who inflicted atrocities on Acoma Pueblo, killing "hundreds of Acomas, and burned houses and kivas." Ongoing resistance by Pueblo religious leaders propelled the Spanish to use missionaries in order to "convert the Indians to Catholicism" and thus encourage them to disidentify from their Pueblo community and cultural practices. Historians Deborah Lawrence and Jon Lawrence note that a new "form of slavery developed whereby Indians who were obtained by Hispanics through war or trade were taken into Spanish households as servants." These "detribalized Indian captives" were referred to as ''genízaros'' and eventually "managed to merge into the larger society over generations."

In the eighteenth century, the population of detribalized people in

In the latter half of the nineteenth century, the Russian Empire began colonizing the Central Asian steppe and the nomadic Indigenous

In the latter half of the nineteenth century, the Russian Empire began colonizing the Central Asian steppe and the nomadic Indigenous

In 1788, there was estimated to be approximately 251,000

In 1788, there was estimated to be approximately 251,000

American Indian boarding schools, which were operational throughout the United States from the late nineteenth century until 1973, attempted to compel detribalization by forcibly instructing Indigenous children to abandon their "tribal languages and traditions," which resulted in cross-generational trauma and detachment from community;Leforestier 2016, p. 59-61. "detribalization was achieved in many ways like cutting the children's hair, giving them clothes typically worn by white people, forbidding them to speak their native language, giving them a new American name, and, most of all, requiring them to speak

American Indian boarding schools, which were operational throughout the United States from the late nineteenth century until 1973, attempted to compel detribalization by forcibly instructing Indigenous children to abandon their "tribal languages and traditions," which resulted in cross-generational trauma and detachment from community;Leforestier 2016, p. 59-61. "detribalization was achieved in many ways like cutting the children's hair, giving them clothes typically worn by white people, forbidding them to speak their native language, giving them a new American name, and, most of all, requiring them to speak

Detribalization is the process by which persons who belong to a particular Indigenous

Detribalization is the process by which persons who belong to a particular Indigenous ethnic

An ethnic group or an ethnicity is a grouping of people

A person ( : people) is a being that has certain capacities or attributes such as reason, morality, consciousness or self-consciousness, and being a part of a culturally established fo ...

identity

Identity may refer to:

* Identity document

* Identity (philosophy)

* Identity (social science)

* Identity (mathematics)

Arts and entertainment Film and television

* ''Identity'' (1987 film), an Iranian film

* ''Identity'' (2003 film), an ...

or community are detached from that identity or community through the deliberate efforts of colonizers and/or the larger effects of colonialism

Colonialism is a practice or policy of control by one people or power over other people or areas, often by establishing colonies and generally with the aim of economic dominance. In the process of colonisation, colonisers may impose their reli ...

.

Detribalization was systematically executed by detaching members from communities outside the colony so that they could be " modernized", Westernized, and, in most circumstances, Christianized, for the prosperity of the colonial state. Historical accounts illustrate several trends in detribalization, with the most prevalent being the role that Western colonial capitalists

Capitalism is an economic system based on the private ownership of the means of production and their operation for profit. Central characteristics of capitalism include capital accumulation, competitive markets, price system, private pr ...

played in exploiting Indigenous people's labor, resources, and knowledge, the role that Christian

Christians () are people who follow or adhere to Christianity, a monotheistic Abrahamic religion based on the life and teachings of Jesus Christ. The words ''Christ'' and ''Christian'' derive from the Koine Greek title ''Christós'' (Χρι� ...

missionaries and the colonial Christian mission

A Christian mission is an organized effort for the propagation of the Christian faith. Missions involve sending individuals and groups across boundaries, most commonly geographical boundaries, to carry on evangelism or other activities, such as ...

system played in compelling Christian membership in place of Indigenous cultural and religious practices, instances of which were recorded in North America

North America is a continent in the Northern Hemisphere and almost entirely within the Western Hemisphere. It is bordered to the north by the Arctic Ocean, to the east by the Atlantic Ocean, to the southeast by South America and th ...

, South America

South America is a continent entirely in the Western Hemisphere and mostly in the Southern Hemisphere, with a relatively small portion in the Northern Hemisphere at the northern tip of the continent. It can also be described as the sou ...

, Africa

Africa is the world's second-largest and second-most populous continent, after Asia in both cases. At about 30.3 million km2 (11.7 million square miles) including adjacent islands, it covers 6% of Earth's total surface area ...

, Asia

Asia (, ) is one of the world's most notable geographical regions, which is either considered a continent in its own right or a subcontinent of Eurasia, which shares the continental landmass of Afro-Eurasia with Africa. Asia covers an are ...

, and Oceania

Oceania (, , ) is a geographical region that includes Australasia, Melanesia, Micronesia, and Polynesia. Spanning the Eastern and Western hemispheres, Oceania is estimated to have a land area of and a population of around 44.5 million ...

, and the systemic conditioning of Indigenous peoples to internalize their own purported inferiority through direct and indirect methods.Gonzalez 2012, p. 69.Schmink and Wood 1992, p. 37-39.Rodriguez 2014, p. 18.Stanner 2011, p. 158.

In the colonial worldview, "civilization" was exhibited through the development of permanent settlements, infrastructure

Infrastructure is the set of facilities and systems that serve a country, city, or other area, and encompasses the services and facilities necessary for its economy, households and firms to function. Infrastructure is composed of public and priv ...

, lines of communication, churches, and a built environment

The term built environment refers to human-made conditions and is often used in architecture, landscape architecture, urban planning, public health, sociology, and anthropology, among others. These curated spaces provide the setting for human ...

based on extraction of natural resources

Natural resources are resources that are drawn from nature and used with few modifications. This includes the sources of valued characteristics such as commercial and industrial use, aesthetic value, scientific interest and cultural value. ...

. Detribalization was usually explained as an effort to raise people up from what colonizers perceived as inferior and " uncivilized" ways of living and enacted by detaching Indigenous persons from their traditional territories, cultural practices, and communal identities. This often resulted in a marginal position within colonial society and exploitation within capitalist industry.Millet 2018, p. 68.

De-Indianization has been used in scholarship as a variant of detribalization, particularly on work in the United States

The United States of America (U.S.A. or USA), commonly known as the United States (U.S. or US) or America, is a country Continental United States, primarily located in North America. It consists of 50 U.S. state, states, a Washington, D.C., ...

and Latin America

Latin America or

* french: Amérique Latine, link=no

* ht, Amerik Latin, link=no

* pt, América Latina, link=no, name=a, sometimes referred to as LatAm is a large cultural region in the Americas where Romance languages — languages derived ...

n contexts. The term detribalization is similarly used to refer to this process of colonial transformation on subsets of the historical and contemporary Indigenous population of the Americas. De-Indianization has been defined by anthropologist Guillermo Bonfil Batalla as a process which occurs "in the realm of ideology" or identity

Identity may refer to:

* Identity document

* Identity (philosophy)

* Identity (social science)

* Identity (mathematics)

Arts and entertainment Film and television

* ''Identity'' (1987 film), an Iranian film

* ''Identity'' (2003 film), an ...

, and is fulfilled when "the pressures of the dominant society succeed in breaking the ethnic identity of the Indian community," even if "the lifeway may continue much as before." De-Indigenization or deindigenization have also been used as variants of detribalization in academic scholarship. For example, academic Patrisia Gonzales has argued how ''mestizaje'' operated as the "master narrative" constructed by colonizers "to ''de-Indigenize'' peoples" throughout Latin America.

While, according to James F. Eder, initial colonial detribalization most often occurred as a result of "land expropriation, habitat destruction, epidemic disease, or even genocide," contemporary cases may not involve such apparent or "readily identified external factors." In a postcolonial framework, "less visible forces associated with political economies of modern nation-states – market incentives, cultural pressures, new religious ideologies – permeate the fabric and ethos of tribal societies and motivate their members to think and behave in new ways."

Usage of term

''Detribalize'' has been defined byMerriam-Webster

Merriam-Webster, Inc. is an American company that publishes reference books and is especially known for its dictionaries. It is the oldest dictionary publisher in the United States.

In 1831, George and Charles Merriam founded the company as ...

as "to cause to lose tribal identity," by Dictionary.com as "to cause to lose tribal allegiances and customs, chiefly through contact with another culture," and by the Cambridge Dictionary

The ''Cambridge Advanced Learner's Dictionary'' (abbreviated ''CALD'') was first published in 1995 under the name ''Cambridge International Dictionary of English'', by the Cambridge University Press. The dictionary has over 140,000 words, ...

as "to make members of a tribe (a social group of people with the same language, customs, and history, and often a recognized leader) stop following their traditional customs or social structure." Detribalization incorporates the word ''tribal'', which has been recognized as an offensive and pejorative term when used in certain contexts. For this reason, ''detribalization'' is sometimes used in quotations when referring to the process being described as a signal to the reader of the term's potentially offensive subtext.

From its early uses to modern scholarship, ''detribalization'' has almost exclusively been applied in particular geographic, and therefore racialized, contexts. As the proceeding section on regional detribalized histories demonstrates, while historical discussion and academic research on "detribalization" and "detribalized" peoples can be found in the African, Asian, Oceanic, North American, and South American contexts, especially when referring to Indigenous histories of each of these regions, to locate instances in which the term has been applied to Europeans or in the European context is exceptionally rare. One of the few instances was by contemporary scholar Ronen Zeidel in a study on Iraqi Gypsies in 2014, who stated "whereas the Gypsies entered a ''detribalized'' Europe with a social organization that was different, contributing to their estrangement, that was not the case in Iraq

Iraq,; ku, عێراق, translit=Êraq officially the Republic of Iraq, '; ku, کۆماری عێراق, translit=Komarî Êraq is a country in Western Asia. It is bordered by Turkey to Iraq–Turkey border, the north, Iran to Iran–Iraq ...

. Iraqi society has never been detribalized."

Misapplication

In the twentieth century, criticisms regarding the usage of ''detribalization'' emerged among scholars, particularly in the African context, who recognized its misapplication as a consequence ofracism

Racism is the belief that groups of humans possess different behavioral traits corresponding to inherited attributes and can be divided based on the superiority of one race over another. It may also mean prejudice, discrimination, or antagoni ...

. South African anthropologist Meyer Fortes noted how the term was commonly used in the European sociological context as a "synonym for such words as 'pathological', 'disintegrated', 'demoralized', in a pejorative or deprecatory sense." Isaac Schapera recognized that the term was being misapplied by Europeans who assumed that urbanization in colonial society implied detribalization: "it is not correct to assume that all people who go to the Union f South Africafrom Bechuanaland tend to become 'detribalized'."Bovenkerk 1975, p. 27. H. M. Robertson states that "the urban native is classed as 'detribalized,' but this is not necessarily the case."Robertson 2015, p. 143. Ellen Hellmann similarly described in her sociological work "that 'the process of detribalization has been exaggerated' among the urban African population, although 'the average European would unhesitatingly classify these Natives as detribalized'." In his sociological study, William Watson concludes that while "under urban conditions, Africans rapidly assimilate European dress, material culture, and outward forms of behaviour, this assimilation does not necessarily imply detribalization. On the contrary, many attempts to organize African industrial workers on a common basis of economic interest have encountered great difficulties because of African tribal solidarities and inter-tribal hostilities."Watson 1958, p. 4-6.

In ''Africa's International Relations: The Diplomacy of Dependency and Change'' (1978), Kenyan academic Ali A Mazrui provides a nuanced discussion of the misapplication of ''detribalization'', recognizing how "there was often an assumption among analysts of the African colonial scene that nationalism made its recruits from the ranks of the detribalized." Since the leaders of anti-colonial movements were, in the majority of instances, "Westernized or semi-Westernized," they were classed as "detribalized" by European colonial authorities. However, Mazrui notes that this employment of ''detribalization'' failed to differentiate between "tribalism as a way of life and tribalism as loyalty to an ethnic group," noting that colonial analysts had only recognized instances of a "weakening of cultural affiliation, though not necessarily of ethnic loyalty." In other words, "a person could adopt an entirely Western way of life but still retain great love and loyalty to the ethnic group from which he sprang." As a result, Mazrui proposes the term ''detraditionalized'', recognizing that "the erosion of tradition oesnot necessarily mean the diminution of ethnicity."

Regional detribalized histories

In Africa

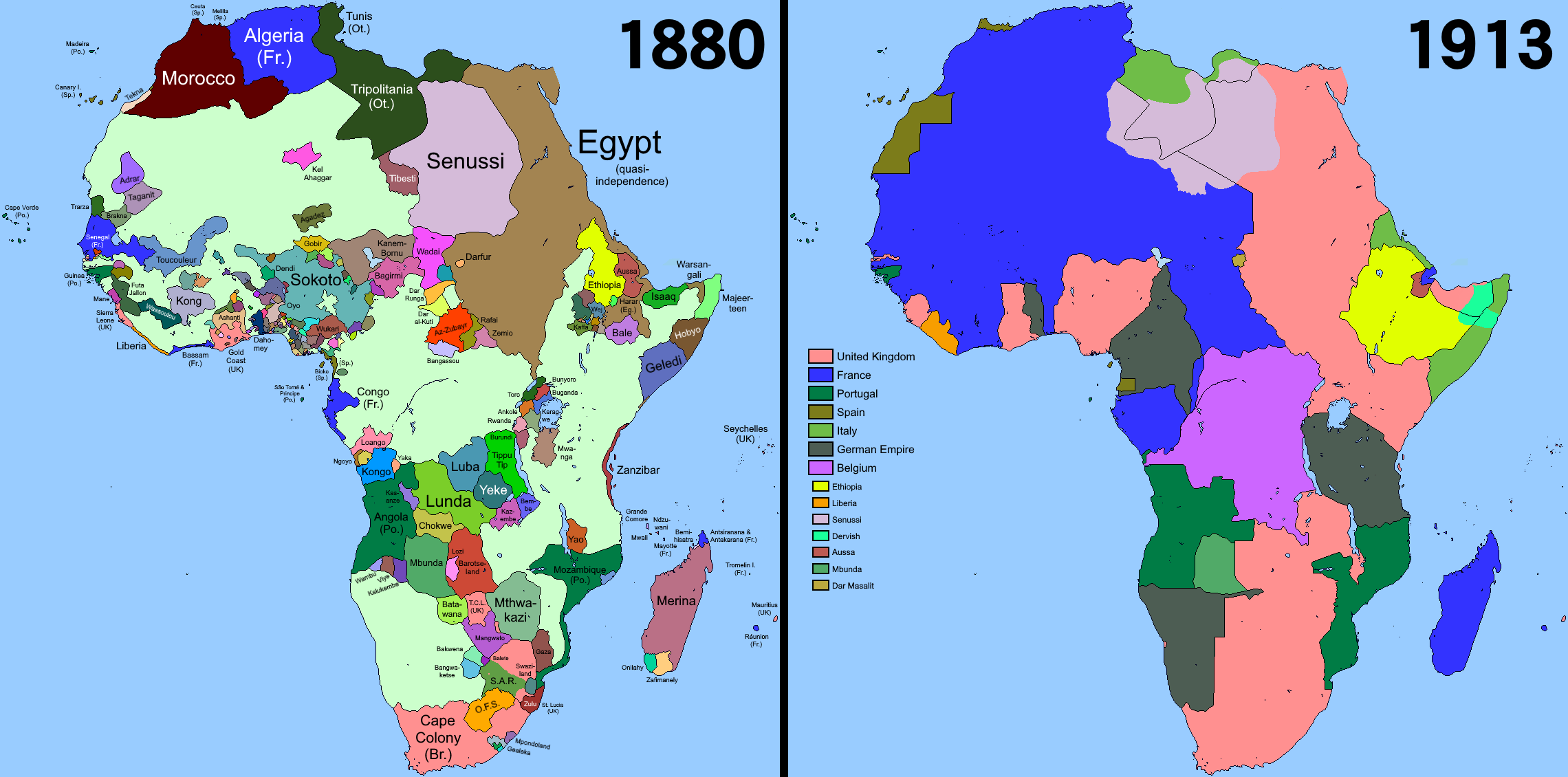

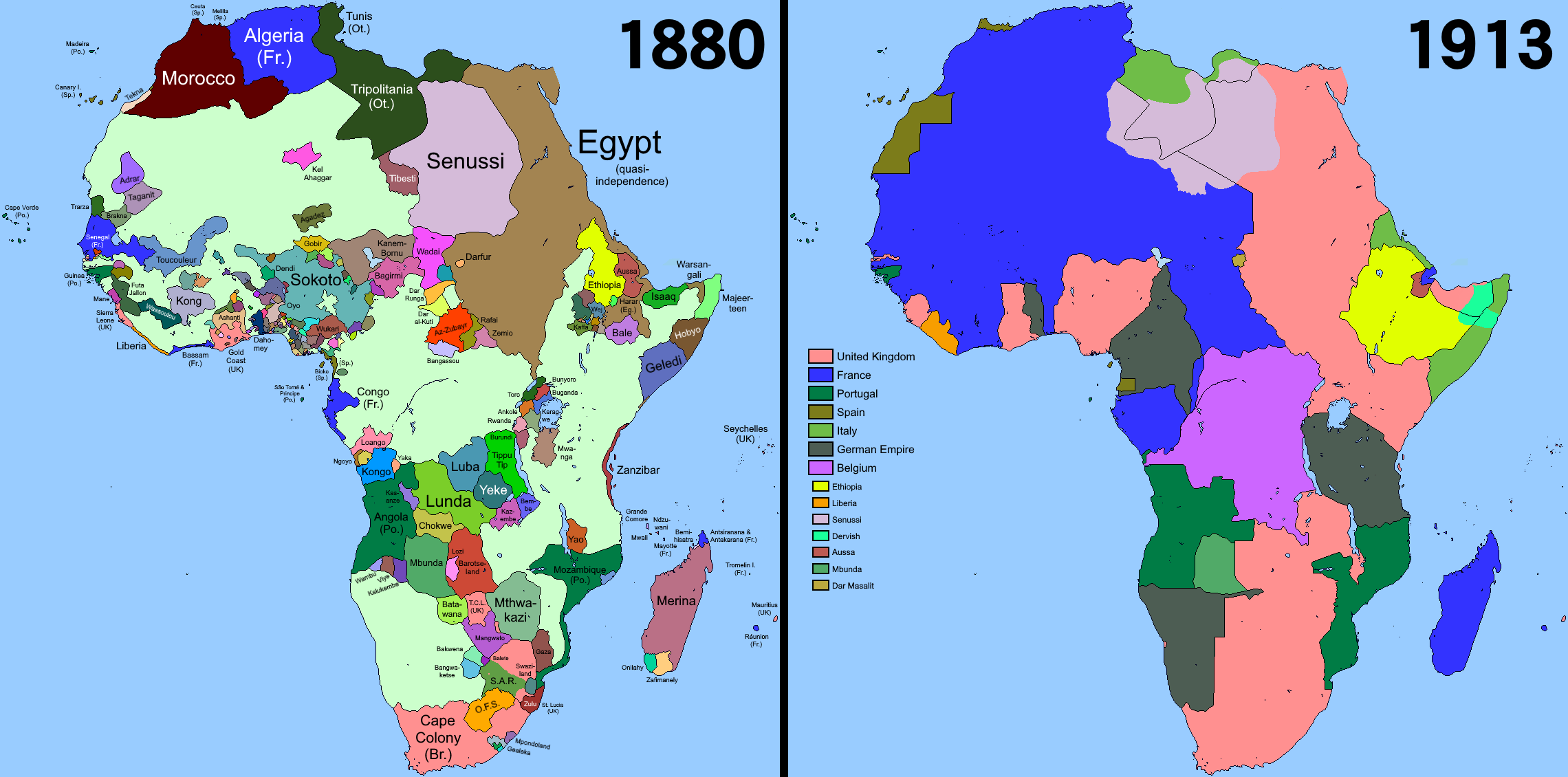

From 1884 to 1885, European powers, along with the United States, convened at the Berlin Conference in order to settle colonial disputes throughout the

From 1884 to 1885, European powers, along with the United States, convened at the Berlin Conference in order to settle colonial disputes throughout the African continent

Africa is the world's second-largest and second-most populous continent, after Asia in both cases. At about 30.3 million km2 (11.7 million square miles) including adjacent islands, it covers 6% of Earth's total surface area ...

and protect the economic interests of their colonial empires. The conference was the primary occasion for partitioning, what Europeans commonly referred to as, "the dark continent", and came about as a result of conflicting territorial claims. The various European colonial powers wish to avoid conflict in their "Scramble for Africa

The Scramble for Africa, also called the Partition of Africa, or Conquest of Africa, was the invasion, annexation, division, and colonization of most of Africa by seven Western European powers during a short period known as New Imperialism ...

", and as such drew clear lines over the continent. In 1898, Polish-British author Joseph Conrad

Joseph Conrad (born Józef Teodor Konrad Korzeniowski, ; 3 December 1857 – 3 August 1924) was a Polish-British novelist and short story writer. He is regarded as one of the greatest writers in the English language; though he did not spe ...

remarked in ''Heart of Darkness

''Heart of Darkness'' (1899) is a novella by Polish-English novelist Joseph Conrad in which the sailor Charles Marlow tells his listeners the story of his assignment as steamer captain for a Belgian company in the African interior. The no ...

'' on how Europeans used color swatches to denote their territorial claims over Africa, a common practice in the period:There was a vast amount of red ritain– good to see at any time, because one knows that some real work is done there, a deuce of a lot of blue rance a little green ortugal smears of orange, and, on the East Coast, a purple patch ermany to show where the jolly pioneers drink the jollyAn empire had to demonstrate effective occupation of the land they were claiming in order to justify their claims to it. Under these guidelines, scholar Kitty Millet has noted, that ''effective'' "'connoted farms, gardens, roads, railways, ndeven postal service." The only entities which could claim ownership "over these diverse African spaces... had to be one of the powers at the conference. Local or Indigenous groups were neither imaginable as political powers nor visible as peers or subjects of European sovereigns." Not only were Indigenous peoples not physically represented at the Berlin Conference, they were also absent "to the European powers' conceptualization of territory. They were not 'on the map'." Rather, Indigenous peoples were perceived by Europeans as property of the land living in an inferiorlager beer Lager () is beer which has been brewed and conditioned at low temperature. Lagers can be pale, amber, or dark. Pale lager is the most widely consumed and commercially available style of beer. The term "lager" comes from the German for "storag .... However, I wasn't going into any of these. I was going into the yellow elgium Dead in the center.

state of nature

The state of nature, in moral and political philosophy, religion, social contract theories and international law, is the hypothetical life of people before societies came into existence. Philosophers of the state of nature theory deduce that the ...

. Prior to their consciousness of their own " whiteness," Millet notes that Europeans were first "conscious of the superiority of their developmental 'progress' ... 'Savages' had temporary huts; they roamed the countryside. They were incapable of using nature appropriately. The colour of their skins condemned them."

Because Indigenous nations were deemed to be "uncivilized," European powers declared the territorial sovereignty of Africa as openly available, which initiated the Scramble for Africa

The Scramble for Africa, also called the Partition of Africa, or Conquest of Africa, was the invasion, annexation, division, and colonization of most of Africa by seven Western European powers during a short period known as New Imperialism ...

in the late nineteenth century. With the continent of Africa conceptualized as effectively "ownerless" territory, Europeans positioned themselves as its redeemers and rightful colonial rulers. In the European colonial mindset, Africans were inferior and incapable of being "civilized" because they had failed to properly manage or exploit the natural resources available to them. As a result, they were deemed to be obstacles to capitalist investment, extraction, and production of natural resources in the construction of a new colonial empire and built environment. The immense diversity of the indigenous peoples of Africa was flattened by this colonial perception, which labeled them instead as an "unrepresentable nomad

A nomad is a member of a community without fixed habitation who regularly moves to and from the same areas. Such groups include hunter-gatherers, pastoral nomads (owning livestock), tinkers and trader nomads. In the twentieth century, the po ...

ic horde of apprehensions that ran across European territories."Millet 2018, p. 82-84.

European colonial authorities, who policed and controlled the majority of territory in Africa by the early twentieth century (with the exception of Ethiopia

Ethiopia, , om, Itiyoophiyaa, so, Itoobiya, ti, ኢትዮጵያ, Ítiyop'iya, aa, Itiyoppiya officially the Federal Democratic Republic of Ethiopia, is a landlocked country in the Horn of Africa. It shares borders with Eritrea to the ...

and Liberia

Liberia (), officially the Republic of Liberia, is a country on the West African coast. It is bordered by Sierra Leone to Liberia–Sierra Leone border, its northwest, Guinea to Guinea–Liberia border, its north, Ivory Coast to Ivory Coast� ...

), were notably ambivalent towards "modernizing" African people. Donald Cameron Donald Cameron may refer to:

Scottish Clan Cameron

* Donald Cameron of Lochiel (c. 1695 or 1700–1748), 19th Chief, and his descendants:

** Donald Cameron, 22nd Lochiel (1769–1832), 22nd Chief

** Donald Cameron of Lochiel (1835–1905), Scot ...

, the governor of the colony of Tanganyika as well as, later, of Nigeria

Nigeria ( ), , ig, Naìjíríyà, yo, Nàìjíríà, pcm, Naijá , ff, Naajeeriya, kcg, Naijeriya officially the Federal Republic of Nigeria, is a country in West Africa. It is situated between the Sahel to the north and the Gulf o ...

, said in 1925: "It is our duty to do everything in our power to develop the native on lines which will not Westernize him and turn him into a bad imitation of a European." Instead, Cameron argued that "the task of 'native administration' was to make him into a 'good African.'" While the French openly professed that their involvement in Africa was a "civilizing mission," scholar Peter A. Blitstein notes that in practice they rejected African "assimilation into French culture," excluded them "from French citizenship," and emphasized "how different Africans were from French, and how important it was to keep the two races separate." Mahmood Mamdani

Mahmood Mamdani, FBA (born 23 April 1946) is an Indian-born Ugandan academic, author, and political commentator. He currently serves as the Chancellor of Kampala International University, Uganda. He was the director of the Makerere Institute o ...

has contended that rather than a "civilizing mission," as was often claimed by European powers to be the rationale for colonization, colonial policy instead sought to "'stabilize racial domination by 'ground ngit in a politically enforced system of ethnic pluralism.'"

In the twentieth century, colonial authorities in Africa intentionally and actively worked to prevent the emergence of nationalist and working-class

The working class (or labouring class) comprises those engaged in manual-labour occupations or industrial work, who are remunerated via waged or salaried contracts. Working-class occupations (see also " Designation of workers by collar colou ...

movements which could ultimately threaten their authority and colonial rule. They sought to prevent "detribalization," which Europeans interpreted as occurring through the urbanization, liberal education

A liberal education is a system or course of education suitable for the cultivation of a free (Latin: ''liber'') human being. It is based on the medieval concept of the liberal arts or, more commonly now, the liberalism of the Age of Enlightenment ...

, and proletarianization of African people, regardless if whether they were detached from their ethnic identity or community or not. European powers adopted a policy of indirect rule, which (1) relied on the use of "traditional" African leadership to maintain order, which was also understood by Europeans, according to historian Leroy Vail, to be "markedly less expensive than the employment of expensive European officials," and (2) was rooted in the belief that "Africans were naturally 'tribal' people." As a result, "detribalization was the ghost which haunted the system" of indirect rule by threatening to undermine colonial capitalist hegemony in Africa. European perspectives of Africans were thoroughly infused with racism, which, according to John E. Flint, "served to justify European power over the 'native' and to keep western-educated Africans from contaminating the rest". Additionally, Alice Conklin has found that, in the post-World War I

World War I (28 July 1914 11 November 1918), often abbreviated as WWI, was List of wars and anthropogenic disasters by death toll, one of the deadliest global conflicts in history. Belligerents included much of Europe, the Russian Empire, ...

period, some officials in French West Africa

French West Africa (french: Afrique-Occidentale française, ) was a federation of eight French colonial territories in West Africa: Mauritania, Senegal, French Sudan (now Mali), French Guinea (now Guinea), Ivory Coast, Upper Volta (now B ...

may have "discovered in 'primitive' Africa an idealized premodern and patriarchal world reminiscent of the one they had lost at Verdun

Verdun (, , , ; official name before 1970 ''Verdun-sur-Meuse'') is a large city in the Meuse department in Grand Est, northeastern France. It is an arrondissement of the department.

Verdun is the biggest city in Meuse, although the capital ...

", a paternalistic

Paternalism is action that limits a person's or group's liberty or autonomy and is intended to promote their own good. Paternalism can also imply that the behavior is against or regardless of the will of a person, or also that the behavior expres ...

position which nonetheless may have served as a rationale for fears over detribalization and the "consequences of modernity."

Under indirect rule, universal primary

Primary or primaries may refer to:

Arts, entertainment, and media Music Groups and labels

* Primary (band), from Australia

* Primary (musician), hip hop musician and record producer from South Korea

* Primary Music, Israeli record label

Works

...

and secondary education

Secondary education or post-primary education covers two phases on the International Standard Classification of Education scale. Level 2 or lower secondary education (less commonly junior secondary education) is considered the second and final ph ...

were not adopted in European colonies in Africa in order to avoid creating a class of "unemployable and politically dangerous, 'pseudo-Europeanized' natives." A curriculum that instead directed Africans towards fulfilling subservient roles which Europeans perceived them as "destined" to play, commonly as members of the colonial peasant

A peasant is a pre-industrial agricultural laborer or a farmer with limited land-ownership, especially one living in the Middle Ages under feudalism and paying rent, tax, fees, or services to a landlord. In Europe, three classes of peasa ...

ry and exploited laborers, was alternatively adopted. European fears over detribalization were also demonstrated via their attitudes toward the notion of African wage labor

Wage labour (also wage labor in American English), usually referred to as paid work, paid employment, or paid labour, refers to the socioeconomic relationship between a worker and an employer in which the worker sells their labour power unde ...

and proletarianization. For this reason, African wage labor was only determined necessary when it aided the advancement or progress of the colonial capitalist state, such as via the African colonial mining industry

Mining is the extraction of valuable minerals or other geological materials from the Earth, usually from an ore body, lode, vein, seam, reef, or placer deposit. The exploitation of these deposits for raw material is based on the economic via ...

. According to Peter A. Blitstein, not a single European colonial power were "able to see wage workers as anything but 'detribalized' and, therefore, dangerous." As a result, the ideal model for African colonial society was one in which small-scale producers could be provided with temporary migrant labor as needed, since "to recognize Africans as workers would ultimately equate them to Europeans, and, perhaps, require the kinds of welfare-state provisions that European workers were beginning to enjoy – trade union membership, insurance, a family wage."

During World War II

World War II or the Second World War, often abbreviated as WWII or WW2, was a world war that lasted from 1939 to 1945. It involved the World War II by country, vast majority of the world's countries—including all of the great power ...

, a study authored by four colonial functionaries and commissioned by the Vichy French

Vichy France (french: Régime de Vichy; 10 July 1940 – 9 August 1944), officially the French State ('), was the fascist French state headed by Marshal Philippe Pétain during World War II. Officially independent, but with half of its ter ...

government's ministry of the colonies in 1944 entitled "Condition of the detribalized natives" called for "the systematic and immediate expulsion of any native illegally entering metropolitan France." Historian Eric T. Jennings has commented how this policy was "certainly not new" and had been informed by "a host of reductionist

Reductionism is any of several related philosophical ideas regarding the associations between phenomena which can be described in terms of other simpler or more fundamental phenomena. It is also described as an intellectual and philosophical p ...

thinkers from Gustave Le Bon to Edouard Drumont or Alexis Carrel", while also eerily foreshadowing arguments to be used by the modern French far right. Jean Paillard, an influential colonial theorist in Vichy France, feared "native domination" in which "the colonizers would eventually come under the domination of the colonized." Similarly, the authors of the study maintained that "the detribalized native becomes an immoral creature as soon as he reaches the city," reiterating European colonial viewpoints in the twentieth century by emphasizing that "detribalization" must be avoided above all measures. However, when detribalization becomes "unavoidable", it must "be accompanied by a strict regimen" of control. According to the study, when "left to their own devices," the "detribalized" persons become drunken failures in European society due to their innate inferiority. Jennings argues that this study attempted to invent a "retribalization" effort for the "detribalized" person and was hinged upon the larger "apocalyptic fears of a world dominated by unruly and debauched 'natives,' uprooted from their 'natural environments.'" This study reflected much of the European theoretical perception of detribalized peoples of the period, as further exemplified in Maurice Barrès

Auguste-Maurice Barrès (; 19 August 1862 – 4 December 1923) was a French novelist, journalist and politician. Spending some time in Italy, he became a figure in French literature with the release of his work '' The Cult of the Self'' in 188 ...

's ''Uprooted'' (1941).

Following the end of the Second World War

World War II or the Second World War, often abbreviated as WWII or WW2, was a world war that lasted from 1939 to 1945. It involved the vast majority of the world's countries—including all of the great powers—forming two opposi ...

, colonial policy began to shift from preventing "detribalization" to more widely promoting devices for economic and cultural development in African colonial societies. In the case of European colonial governments, they began to promote self-government as a means of obtaining independence. European colonial empires in Africa increasingly opted for nationalization

Nationalization (nationalisation in British English) is the process of transforming privately-owned assets into public assets by bringing them under the public ownership of a national government or state. Nationalization usually refers to p ...

rather than previous policies of indirect rule and forced contracted or temporary labor. However, according to historian Peter A. Blitstein, the ultimate objectives of the European colonial powers for Westernizing colonized and "detribalized" Africans remained unclear by the mid-twentieth century, as colonizers struggled to articulate how Africans could be brought into congruence with their visions of "modernity."

Throughout post-independence Africa, two different types of African states emerged, according to scholar Mahmood Mamdani, which he terms as "the conservative and the radical" African states. While the conservative African state adopted a decentralized form of despotic authority that "tended to bridge the urban-rural divide through a clientelism

Clientelism or client politics is the exchange of goods and services for political support, often involving an implicit or explicit quid-pro-quo. It is closely related to patronage politics and vote buying. Clientelism involves an asymmetric rel ...

whose effect was to exacerbate ethnic divisions," the radical African state adopted a centralized form of despotic authority that contributed to detribalization by tightening control over local authorities. Mamdani theorizes that "if the two-pronged division that the colonial state enforced on the colonized – between town and country, and between ethnicities – was its dual legacy at independence, each of the two versions of the postcolonial state tended to soften one part of the legacy while exacerbating the other."

Southern Africa

In the seventeenth century, the

In the seventeenth century, the Dutch East India Company

The United East India Company ( nl, Verenigde Oostindische Compagnie, the VOC) was a chartered company established on the 20th March 1602 by the States General of the Netherlands amalgamating existing companies into the first joint-stock ...

was importing shiploads of slaves to South Africa, transferring the former colonial station for passing ships into a slaveholding colony. In 1685, the Cape Colony

The Cape Colony ( nl, Kaapkolonie), also known as the Cape of Good Hope, was a British colony in present-day South Africa named after the Cape of Good Hope, which existed from 1795 to 1802, and again from 1806 to 1910, when it united with ...

's last company commander and first governor Simon van der Stel formed an exploration party to locate a copper reserve that the Indigenous Nama people

Nama (in older sources also called Namaqua) are an African ethnic group of South Africa, Namibia and Botswana. They traditionally speak the Nama language of the Khoe-Kwadi language family, although many Nama also speak Afrikaans. The Nama Pe ...

had shown him. The Nama were reportedly described by the colonists as "'very friendly'" and, scholar Kitty Millet notes that, "relations were so amenable between the Nama and the Dutch settlers that the Nama treated the colony to a musical 'exhibition' for the governor's birthday." However, shortly after Dutch settlers introduced slave labor to the region and arrived in increasingly greater numbers, conflicts from 1659 to 1660 and 1673 to 1677, followed by a smallpox outbreak, caused the majority of the Nama to flee from their traditional territory. Those who remained soon "existed as 'detribalized indigenous peoples'."

Early maps created by European colonizers portrayed an image of southern Africa as a '' terra nullius'' of "uncivilized" Indigenous villages and "wild beasts." As early as the 1760s, Europeans sought to organize Nama settlements in the region into "'natural' preserves" that would enable segregation of colonists from Indigenous peoples. When the British first took over the colony in 1798, John Barrow, a British statesman, perceived himself as "a reformer in comparison with the Boer

Boers ( ; af, Boere ()) are the descendants of the Dutch-speaking Free Burghers of the eastern Cape frontier in Southern Africa during the 17th, 18th, and 19th centuries. From 1652 to 1795, the Dutch East India Company controlled this are ...

utch'burghers' and government officials whose embrace of slavery, and land grabs, had destroyed not only Nama tribes living near them, but also the land itself on which they staked their farms." The Nama tribes on the Namaaqua plain had been absorbed into the South African colony as "individual units of labour" and reportedly lived "in a state of 'detribalization.'" As the Nama were increasingly exploited and brought into subservience to Europeans, many completely abandoned the territory of the expanding Cape Colony, choosing instead to settle along the Orange River

The Orange River (from Afrikaans/Dutch: ''Oranjerivier'') is a river in Southern Africa. It is the longest river in South Africa. With a total length of , the Orange River Basin extends from Lesotho into South Africa and Namibia to the north ...

. Many were also absorbed into Orlam communities, where "they existed as herders and 'outlaws,' conducting raids on Boer farms."

From 1800 to 1925, approximately 60 missionary societies from Europe established more than 1,030 mission stations throughout southern Africa. A study on the location and role of these mission stations by Franco Frescura noted how throughout the nineteenth century, there was a "spreading geographical presence of missionaries over southern Africa", which paralleled the restructuring of the social, economic, and political landscape of the region by colonial forces. Despite their stated purpose, missionaries were reportedly unsuccessful in converting many Indigenous people to Christianity. One study reported that only about "12% of people on mission settlements were there for ''spiritual'' reasons" and that the majority of people often remained either for a "material advantage or psychological security." Throughout southern Africa, while "some groups such as the Basotho and the Tswana openly welcomed missionaries, others like the Pedi, the Zulu, and the Pondo vehemently rejected their presence as a matter of national policy." In some cases, entire populations relocated away from the mission settlements and ostracized members of their community who had been converted or resided at the settlements, effectively expelling them from their communities.

In 1806, German

German(s) may refer to:

* Germany (of or related to)

**Germania (historical use)

* Germans, citizens of Germany, people of German ancestry, or native speakers of the German language

** For citizens of Germany, see also German nationality law

**Ge ...

missionaries working under the London Missionary Society were reportedly the "first white persons" to arrive in what is now modern-day Namibia

Namibia (, ), officially the Republic of Namibia, is a country in Southern Africa. Its western border is the Atlantic Ocean. It shares land borders with Zambia and Angola to the north, Botswana to the east and South Africa to the south and ea ...

. They soon founded mission stations with surrounding fields and territories in an effort to Christianize and sedenteraize the Indigenous peoples. However, because of the harsh climate and severe drought, their attempts at maintaining the stations failed. They converted one Orlam ''kaptein'', Jager Afrikaner

Jager Afrikaner ( Nama name: ǀHomǀaramab, baptised Christian Afrikaner (?) at ''Roode Zand'' near Tulbagh, South Africa – 18 August 1823 at Blydeverwacht, South-West Africa) was the third Captain of the Orlam in South West Africa, succeed ...

, the father of Jonker Afrikaner

Jonker Afrikaner ( 1785, ''Roode Zand'' near Tulbagh, South Africa – 18 August 1861, Okahandja) was the fourth Captain of the Orlam in South West Africa, succeeding his father, Jager Afrikaner, in 1823. Soon after becoming ''Kaptein'', ...

, who would become an important Namibian politician. Missionaries struggled to indoctrinate the Indigenous peoples in the region with their ideologies due to outright opposition from the Herero

Herero may refer to:

* Herero people

The Herero ( hz, Ovaherero) are a Bantu ethnic group inhabiting parts of Southern Africa. There were an estimated 250,000 Herero people in Namibia in 2013. They speak Otjiherero, a Bantu language. Though t ...

, who were the most powerful Indigenous group and were unconvinced of the professed "holy mission" of the missionaries. European settlers considered the Herero, like other Indigenous people in the region, as "uncivilized" because they did not practice sedentary farming nor openly accept Western ideologies. A German missionary illuminated this wider perspective regarding his encounters with the Nama people: "The Nama does not want to work but to live a life of ease. But the Gospel says he must work in the sweat of his brows. He is therefore opposed to the Gospel." This was a common perception among missionaries in southern Africa, who "sought to impose an alien morality and work ethos upon the local people without realizing that these undermined their most basic social and cultural tenets and were therefore largely resisted."

The status of detribalization was perceived by Dutch colonizers as a potential method of redemption, as noted by scholar Kitty Millet, so that "the 'detribalized' African" could learn "his proper place" as a member of an exploited class of laborers fueling colonial industry. The Orlam people were understood as "detribalized Namas" who had now lived for several generations on the outskirts of colonial society as both indentured bonded servants and as enslaved people subjugated to a position of servitude to the Dutch settlers (also referred to as Boers

Boers ( ; af, Boere ()) are the descendants of the Dutch-speaking Free Burghers of the eastern Cape frontier in Southern Africa during the 17th, 18th, and 19th centuries. From 1652 to 1795, the Dutch East India Company controlled this a ...

). In the nineteenth century, as Millet reports, there was a "concerted effort" by the Dutch Cape Colony

The Cape Colony ( nl, Kaapkolonie), also known as the Cape of Good Hope, was a British colony in present-day South Africa named after the Cape of Good Hope, which existed from 1795 to 1802, and again from 1806 to 1910, when it united with ...

government to "detach individuals from the tribal group" of the Orlam, "to 'detribalize' them through labor, either through indenture or enslavement." In order to maintain the colonial capitalist order, the Dutch "not only wanted to destroy the physical polities of indigenous tribes among or in proximity to them, substituting them with a docile class of labourers, but also wanted them to forget, completely, their prior existence as 'independent' peoples. The colony's 'health' depended on the removal of independent tribes and, in their stead, the visibility of the 'detribalized' servant."

In order to psychologically condition Orlam people to accept a subordinate role, the Dutch deliberately infantilized enslaved peoples to reinforce their status as inferior. In this regard, even if a slave escaped captivity and joined "free" Orlam communities as a fugitive, "the slave brought with him the memory of this infantilization." This dehumanizing treatment collectively triggered widespread resistance to Dutch colonialism in Orlam communities, who formed an aware and active community in Cape Town

Cape Town ( af, Kaapstad; , xh, iKapa) is one of South Africa's three capital cities, serving as the seat of the Parliament of South Africa. It is the legislative capital of the country, the oldest city in the country, and the second largest ...

by maintaining relationships with enslaved peoples who remained under Dutch control. This pushed Orlam communities further to the margins, especially as Dutch Boer farmers "annexed more land, and moved closer to the 'fringes'" as a response to the transference of colonial political power. This ongoing resistance within Orlam communities led to the formation of politically centralized leaders in the early nineteenth century, known as ''kapteins'', who functioned as authorities in the community unlike in any traditional Nama society.Millet 2018, p. 75-76.

As the European colonists targeted Orlam ''kapteins'', scholar Kitty Millet notes, "even more 'detribalized' individuals oinedthe 'fugitives' already established at the margins" of colonial society. However, either oblivious to or refusing to acknowledge their own role in generating this deeply entrenched resistance, European colonists credited Orlam resistance with what they perceived to be an "ontological predisposition" within the detribalized Orlam people, which allegedly reflected a "primitive 'state of being'." They presumed that the Orlam's reestablishment as communities at the fringes of colonial society was an expression of their inherent nomadic disposition. As resistance continued to the colonial order, more and more groups with "diverse origins" also joined Orlam collectives, despite being notably "unrelated to their ''kapteins''." Despite the heterogeneity of the Orlam collectives, they were able to fight their own subjugation and reestablish themselves as an Indigenous polity

A polity is an identifiable political entity – a group of people with a collective identity, who are organized by some form of institutionalized social relations, and have a capacity to mobilize resources. A polity can be any other group of ...

.Millet 2018, p. 76-77.

Over time, the burgeoning numbers of resistance groups could not be sustained by the surrounding region of the Cape Colony because of low rainfall and drought. As resources depleted, detribalized Orlam resistance groups moved northward and eventually crossed the Orange River to reunite with the Nama. Each of the Orlam resistance groups requested permission from the Nama confederation

A confederation (also known as a confederacy or league) is a union of sovereign groups or states united for purposes of common action. Usually created by a treaty, confederations of states tend to be established for dealing with critical iss ...

and reentered Nama land between 1815 and 1851. As they reintegrated into the Nama community, the Orlam groups quickly transformed how the Nama perceived themselves and their relationships with the neighboring Herero, as well as with the colonial traders and missionaries who had accompanied the Orlam resistance groups in their reintegration. As a result of this reintegration, Kitty Millet notes that a new Nama leadership emerged under Kido Witbooi

Cupido Witbooi, variations: Kido and Kiwitti Witbooi, Nama name: ǂA-ǁêib ǃGâmemab, ( – 31 December 1875) was the first Kaptein of the ǀKhowesin (Witbooi Nama), a subtribe of the Orlam of South-West Africa, present-day Namibia.

Witbooi wa ...

's grandson, Hendrik Witbooi. Witbooi was a Christian who understood his leadership as a divine mandate

In European Christianity, the divine right of kings, divine right, or God's mandation is a political and religious doctrine of political legitimacy of a monarchy. It stems from a specific metaphysical framework in which a monarch is, befor ...

. While traditional Nama tribes had preferred pacifism

Pacifism is the opposition or resistance to war, militarism (including conscription and mandatory military service) or violence. Pacifists generally reject theories of Just War. The word ''pacifism'' was coined by the French peace camp ...

to armed conflict prior to the integration of the detribalized Orlam groups, Witbooi altered this understanding and believed it was his mission to continue the resistance effort among the Nama. Hendrik Witbooi was killed in battle with German colonial military forces in 1905 and is now understood to be a national hero in Namibia.

German South West Africa was established in 1884 following decades of German settlers and missionaries occupying the region and conducting work through missionary societies such as the Rhenish Missionary Society

The Rhenish Missionary Society (''Rhenish'' of the river Rhine) was one of the largest Protestant missionary societies in Germany. Formed from smaller missions founded as far back as 1799, the Society was amalgamated on 23 September 1828, and i ...

. The German Empire

The German Empire (),Herbert Tuttle wrote in September 1881 that the term "Reich" does not literally connote an empire as has been commonly assumed by English-speaking people. The term literally denotes an empire – particularly a hereditary ...

officially claimed dominion and sovereignty over present-day Namibia, which included the traditional territories of the Herero and Ovambo Ovambo may refer to:

*Ovambo language

*Ovambo people

*Ovamboland

Ovamboland, also referred to as Owamboland, was a Bantustan in South West Africa (present-day Namibia), intended by the apartheid government to be a self-governing homeland ...

of the northern region, bands of Khoisan

Khoisan , or (), according to the contemporary Khoekhoegowab orthography, is a catch-all term for those indigenous peoples of Southern Africa who do not speak one of the Bantu languages, combining the (formerly "Khoikhoi") and the or ( in ...

( San and Khoikhoi

Khoekhoen (singular Khoekhoe) (or Khoikhoi in the former orthography; formerly also '' Hottentots''"Hottentot, n. and adj." ''OED Online'', Oxford University Press, March 2018, www.oed.com/view/Entry/88829. Accessed 13 May 2018. Citing G. S. ...

) in the central and southern regions, and the Damara in the mountainous regions. German colonists unilaterally applied the category of "bushmen" to these groups, because they perceived them as primitive "hunter-gatherer

A traditional hunter-gatherer or forager is a human living an ancestrally derived lifestyle in which most or all food is obtained by foraging, that is, by gathering food from local sources, especially edible wild plants but also insects, fung ...

s." Related to the Khoikhoi were the Nama, who by the nineteenth century had settled in the southwestern regions of Namibia and northern South Africa as a result of colonial displacement. White colonists living in the Cape Colony

The Cape Colony ( nl, Kaapkolonie), also known as the Cape of Good Hope, was a British colony in present-day South Africa named after the Cape of Good Hope, which existed from 1795 to 1802, and again from 1806 to 1910, when it united with ...

similarly referred to Khoisan and Nama as " Hottentots," a collective name originally coined by the German settlers in South West Africa. These labels demonstrated the European colonial perspective of Indigenous peoples, which flattened their complexities into a singular class of uniform colonized subjects.

In the nineteenth century, European missionaries sought to eradicate Indigenous ways of living and knowing through the process of Christianization to, as scholar Jason Hickel

Jason Edward Hickel (born 1982) is an economic anthropologist whose research focuses on ecological economics, global inequality, imperialism and political economy. He is known for his books ''The Divide: A Brief Guide to Global Inequality and ...

argues, mold them into "the bourgeois

The bourgeoisie ( , ) is a social class, equivalent to the middle or upper middle class. They are distinguished from, and traditionally contrasted with, the proletariat by their affluence, and their great cultural and financial capital. ...

European model." As colonial German academic and theologian

Theology is the systematic study of the nature of the divine and, more broadly, of religious belief. It is taught as an academic discipline, typically in universities and seminaries. It occupies itself with the unique content of analyzing the ...

Gustav Warneck stated in 1888, "without doubt it is a far more costly thing to kill the ndigenous populationthan to Christianise them." Contrary to the stated "civilizing" objectives of missionaries, colonial administrators sought to preserve "traditional" African structures in order to maintain their indirect rule, consistently pushing Africans to the margins of colonial society. According to Hickel, administrators even regarded "the idea of a civilizing mission with suspicion, fearing that 'detribalization' would lead to social anomie

In sociology, anomie () is a social condition defined by an uprooting or breakdown of any moral values, standards or guidance for individuals to follow. Anomie is believed to possibly evolve from conflict of belief systems and causes breakdow ...

, mass unrest, and the rise of a politically conscious class that would eventually undermine minority rule altogether." The Native Affairs Department, established by Cecil Rhodes

Cecil John Rhodes (5 July 1853 – 26 March 1902) was a British mining magnate and politician in southern Africa who served as Prime Minister of the Cape Colony from 1890 to 1896.

An ardent believer in British imperialism, Rhodes and his Bri ...

in 1894, sought to prop up African "tradition" for this reason:The idea was to preventHowever, by the early twentieth century, as a result of the "insatiable appetite f colonizersfor cheap labor," the previous colonial policy of indirect rule began to weaken considerably, which resulted in the emergence of numerous informal settlements on the peripheries of "white cities" in southern Africa. In response to the overwhelming "unauthorized" urbanization of Africans, European colonial administrators eventually adopted the moralizing approach of their missionary counterparts and sought to "reform" African shanties, which were regarded as undisciplined chaotic spaces that blurred the order of colonial society as a "social-evolutionary misfire." Social scientists of the period upheld this perspective and disseminated these ideas widely, as represented in their perceptions of the "detribalized" African subjects who they perceived as inhabiting these peripheral informal settlements.urbanization Urbanization (or urbanisation) refers to the population shift from rural to urban areas, the corresponding decrease in the proportion of people living in rural areas, and the ways in which societies adapt to this change. It is predominantly th ...by keeping Africans confined to native reserves, and to govern them according to a codified form of customary law through existing patriarchs and chiefs. Then, using an intricate network of influx controls, Africans were brought temporarily to the cities for work on fixed-term contracts, at the end of which they were expelled back to the reserves. The system was purposefully designed to prevent full proletarianization and forestall the rise of radical consciousness.Hickel 2015, p. 91.

Austro-Hungarian

Austria-Hungary, often referred to as the Austro-Hungarian Empire,, the Dual Monarchy, or Austria, was a constitutional monarchy and great power in Central Europe between 1867 and 1918. It was formed with the Austro-Hungarian Compromise of 1 ...

philosopher Karl Polanyi referred to "detribalized" South Africans in highly racist and pathological terms, stating that the " ''kaffir'' of South Africa, a noble savage, whom none felt socially more secure in his native kraal

Kraal (also spelled ''craal'' or ''kraul'') is an Afrikaans and Dutch word, also used in South African English, for an enclosure for cattle or other livestock, located within a Southern African settlement or village surrounded by a fence of t ...

, has been transformed into a human variety of half-domesticated animal dressed in the 'unrelated, the filthy, the unsightly rags that not the most degenerated white man would wear,' a nondescript being, without self-respect or standards, veritable human refuse." Anthropologist Bronislaw Malinowski similarly "decried 'detribalized' natives as 'sociologically unsound' monstrosities who had lost the regulated order of 'tribal' society – but given their lack of access to the necessary material resources – had failed to approximate the structure of 'European' society." The "out-of-category" status of "detribalized" urban South Africans was perceived as a threat to the European colonial order. In South Africa and Namibia, the colonial government soon "forced heir

Inheritance is the practice of receiving private property, titles, debts, entitlements, privileges, rights, and obligations upon the death of an individual. The rules of inheritance differ among societies and have changed over time. Offic ...

relocations into modernist townships laid out along rectilinear grids" with the stated intention of conditioning "detribalized" Africans to become "happy, docile subjects" who would "internalize the values of European domesticity."

While Europeans and white South Africans

White South Africans generally refers to South Africans of European descent. In linguistic, cultural, and historical terms, they are generally divided into the Afrikaans-speaking descendants of the Dutch East India Company's original settle ...

during this period classed all urban Africans as "detribalized," this was largely an extension of existing racism which had flattened all Africans into indistinguishable masses of "disorderly" racialized subjects and was not necessarily reflective of reality. In fact, many Indigenous people working on European-owned farms and in urban districts were not formally "detribalized," or detached from their "tribal" identities or communities. Professor at Stellenbosch University J. F. W. Grosskopf recorded that "many Europeans coming into touch with the native only in the bigger centres seem inclined to over-estimate the number of 'detribalized' natives... Such natives may have adopted a semi-European urban mode of life for several years, while it still remains a difficult matter for the white man to say how far tribal influence and connection has actually ceased." In 1914, Grosskopf documented an instance in which several urbanized Black South Africans

Racial groups in South Africa have a variety of origins. The racial categories introduced by Apartheid remain ingrained in South African society with South Africans and the South African government continuing to classify themselves, and each o ...

who had "never visited their tribe in Thaba Nehu" left their "permanent and well-paid jobs in Bloomfontein" after a Baralong chief "bought land for his followers in the southern part of Rhodesia

Rhodesia (, ), officially from 1970 the Republic of Rhodesia, was an unrecognised state in Southern Africa from 1965 to 1979, equivalent in territory to modern Zimbabwe. Rhodesia was the ''de facto'' successor state to the British colony of So ...

." They recorded in a notice to their employers that they were leaving "'for our chief is calling us'." Anthropologist Isaac Schapera similarly noted that urbanization did not necessarily imply detribalization, essentially recognizing the differences between assimilation in Western society and detribalization.

Yet, with increasingly racist perceptions of Black South Africans, scholar Jason Hickel notes that "white South Africans saw detribalization as a process of decay, as the decomposition of tribal social order into a chaotic tangle of random persons and unmarried women." This was exemplified in their perceptions of townships, which were "regarded as makeshift and transient, in between the traditional African homestead and the modern European house." White South Africans adopted, what they considered to be, a "civilizing mission" with reluctance, conceding that "urban Africans" were "needed as labor" and "could husnot be 'retribalized.'" The first townships at Baumannville, Lamontville, and Chesterville were constructed in the 1930s and 1940s for this purpose. According to Hickel, the planners of these townships sought to "reconcile two competing ideas: on the one hand a fear that 'detribalization' of Africans would engender immense social upheaval, and, on the other hand, a belief that 'civilizing' Africans into an established set of social norms would facilitate docility." These conditions and perceptions continued throughout the apartheid

Apartheid (, especially South African English: , ; , "aparthood") was a system of institutionalised racial segregation that existed in South Africa and South West Africa (now Namibia) from 1948 to the early 1990s. Apartheid was ...

era in South Africa and Namibia. South African political theorist Aletta Norval

Aletta Norval is a South African born political theorist. she is Deputy Vice-Chancellor (Education) at Anglia Ruskin University. A prominent member of the Essex School of discourse analysis, she is mainly known for her deconstructionist analysi ...

notes that as the apartheid system expanded, "the 'detribalized Native' had to be regarded as a 'visitor' in the cities until such time as the ideal of total apartheid could be reached" through complete racial segregation.

In ''Sounds of a Cowhide Drum'' (1971), Soweto

Soweto () is a township of the City of Johannesburg Metropolitan Municipality in Gauteng, South Africa, bordering the city's mining belt in the south. Its name is an English syllabic abbreviation for ''South Western Townships''. Formerly a ...

poet Oswald Mbuyiseni Mtshali authored a poem entitled "The Detribalised" in which he described the consequences of detribalization and township life in South Africa. In a review of his work by Doreen Anderson Wood, she acknowledges how "sociologists and anthropologists have observed how detribalization and forcing mine workers into compound living asweakened family life in Africa, but few portray it with Mtshali's punch." Wood asserts that because they have been "denied admittance into full twentieth-century life the detribalized fall into a vacuum of surface sophistication with no values underpinning it." Mtshali's poem encapsulates the experience of an unnamed man who was "born in Sophiatown, or Alexandra

Alexandra () is the feminine form of the given name Alexander (, ). Etymologically, the name is a compound of the Greek verb (; meaning 'to defend') and (; GEN , ; meaning 'man'). Thus it may be roughly translated as "defender of man" or "p ...

, I am not sure, but certainly not in Soweto." This "detribalized" man, in Mtshali's perspective, did not care for politics or concern himself with the imprisonment of anti-apartheid figures like Robert Sobukwe or Nelson Mandela

Nelson Rolihlahla Mandela (; ; 18 July 1918 – 5 December 2013) was a South African anti-apartheid activist who served as the first president of South Africa from 1994 to 1999. He was the country's first black head of state and the ...

on Robben Island, and was perhaps reflective, in Wood's words, of men who had been removed from the "stabilizing influences of tribal life" as a result of colonialism.

In the Americas

Regarding the greaterMesoamerica

Mesoamerica is a historical region and cultural area in southern North America and most of Central America. It extends from approximately central Mexico through Belize, Guatemala, El Salvador, Honduras, Nicaragua, and northern Costa Rica. Wit ...

n region, scholar Roberto Cintli Rodríguez

Roberto Cintli Rodríguez is a columnist, author, and academic of Mexican American Studies at the University of Arizona.

On March 23, 1979, Rodriguez was taking photos on the corner of Whittier Boulevard and McDonnell Avenue in East Los Angeles ...

describes how the Spanish inflicted two forms of colonization upon Indigenous peoples. While the first conquest refers to the military conquest campaigns under the authority of Hernán Cortés

Hernán Cortés de Monroy y Pizarro Altamirano, 1st Marquess of the Valley of Oaxaca (; ; 1485 – December 2, 1547) was a Spanish ''conquistador'' who led an expedition that caused the fall of the Aztec Empire and brought large portions of w ...

and other conquistadors, "La Otra Conquista r ''the Other Conquest''included religiously motivated crusades to destroy all the temples, 'idols,' and books of Indigenous peoples." Coupled with centuries of violence, in which millions of Indigenous people were "devastated by war, mass killings, rape, enslavement, land theft, starvation, famine, and disease", the Other Conquest was simultaneously facilitated by the Spanish from the sixteenth to the nineteenth centuries with the central objecive of destroying " maíz-based beliefs and cultures of Indigenous peoples, ushering in a radical shift in the ''axis mundi

In astronomy, axis mundi is the Latin term for the axis of Earth between the celestial poles.

In a geocentric coordinate system, this is the axis of rotation of the celestial sphere.

Consequently, in ancient Greco-Roman astronomy, the ' ...

'' or center of the universe from maíz to the Christian cross," with the threat of death, torture, and eternal damnation for a refusal to conform to the colonial order. Rodríguez illuminates that although outright usage of force from the church has faded, official church messages in Latin America

Latin America or

* french: Amérique Latine, link=no

* ht, Amerik Latin, link=no

* pt, América Latina, link=no, name=a, sometimes referred to as LatAm is a large cultural region in the Americas where Romance languages — languages derived ...

still continue to reinforce this practice today.

Spanish colonizers established a system of "''congregaciones'' (the congregation of peoples) and the project of ''reducciones

Reductions ( es, reducciones, also called ; , pl. ) were settlements created by Spanish rulers and Roman Catholic missionaries in Spanish America and the Spanish East Indies (the Philippines). In Portuguese-speaking Latin America, such red ...

'' (spiritual 'reductions')" in an effort "to corrall Indians into missions or pueblos for the purpose of reducing or eliminating or 'killing' the souls of the Indians, creating Christians in their place." This method of "spiritually reducing Indians also served to facilitate land theft", and was first implemented in 1546, only to be reaffirmed numerous times throughout the colonial period. In 1681, as part of the Laws of the Indies

The Laws of the Indies ( es, Leyes de las Indias) are the entire body of laws issued by the Spanish Crown for the American and the Asian possessions of its empire. They regulated social, political, religious, and economic life in these areas. T ...

, issued by the Spanish Crown

, coatofarms = File:Coat_of_Arms_of_Spanish_Monarch.svg

, coatofarms_article = Coat of arms of the King of Spain

, image = Felipe_VI_in_2020_(cropped).jpg

, incumbent = Felipe VI

, incumbentsince = 19 Ju ...

for the American

American(s) may refer to:

* American, something of, from, or related to the United States of America, commonly known as the "United States" or "America"

** Americans, citizens and nationals of the United States of America

** American ancestry, pe ...

and the Philippine possessions of its empire

An empire is a "political unit" made up of several territories and peoples, "usually created by conquest, and divided between a dominant center and subordinate peripheries". The center of the empire (sometimes referred to as the metropole) ex ...

, "continued the reduction of the Indians (their instruction in the Holy Faith) 'so that they could forget the errors of their ancient rites and ceremonies'." The reduction policies instituted by the Spanish colonizers "included the systemic demonization by Spanish friars of virtually all things Indigenous, particularly the people themselves, unless saved or baptized."

The "official Spanish practice regarding what language, indigenous or Castilian, should be employed in the evangelization effort hroughout New Spainwas often confused." The "colonial aim" was to Hispanicize the Indigenous people and to forcibly separate them from identifying with their cultural practices; "church and state officials intermittently used various decrees reiterating the official position and requiring that the Indians systematically be taught Spanish," such as one issued by the archbishop in Mexico City

Mexico City ( es, link=no, Ciudad de México, ; abbr.: CDMX; Nahuatl: ''Altepetl Mexico'') is the capital and largest city of Mexico, and the most populous city in North America. One of the world's alpha cities, it is located in the Valley o ...

in 1717. At the same time, because many missionaries were "more interested in trying to impart what they considered the basis of their faith to the native peoples as quickly as possible" through Christianization, this led many to "acquire the rudiments of the indigenous languages" for the purposes of indoctrinating Indigenous people to become Christians.

Brazil

Portuguese colonizers arrived on the eastern seaboard of South America in 1500 and had established permanent settlements in the interior regions of

Portuguese colonizers arrived on the eastern seaboard of South America in 1500 and had established permanent settlements in the interior regions of Amazonia

The Amazon rainforest, Amazon jungle or ; es, Selva amazónica, , or usually ; french: Forêt amazonienne; nl, Amazoneregenwoud. In English, the names are sometimes capitalized further, as Amazon Rainforest, Amazon Forest, or Amazon Jungle. ...

a century later. Expeditions into the interior were carried out by Portuguese ''bandeirantes

The ''Bandeirantes'' (), literally "flag-carriers", were slavers, explorers, adventurers, and fortune hunters in early Colonial Brazil. They are largely responsible for Brazil's great expansion westward, far beyond the Tordesillas Line of 1494 ...

'', who often "depended on Amerindians as rowers, collectors, and guides." ''Bandeirantes'' frequently turned these exploratory crusades "into slaving

Slavery and enslavement are both the state and the condition of being a slave—someone forbidden to quit one's service for an enslaver, and who is treated by the enslaver as property. Slavery typically involves slaves being made to perf ...

expeditions" through abducting, detaining, and exploiting the indigenous peoples of Brazil. The expeditions also carried "European diseases and death far into the interior" of the region. In 1645, Jesuit priests

, image = Ihs-logo.svg

, image_size = 175px

, caption = ChristogramOfficial seal of the Jesuits

, abbreviation = SJ

, nickname = Jesuits

, formation =

, founders = ...

under the leadership of António Vieira

Pedro António Vieira (; 6 February 160818 July 1697) was an Afro-Portuguese Jesuit priest, diplomat, orator, preacher, philosopher, writer, and member of the Royal Council to the King of Portugal.

Biography

Vieira was born in Lisbon to ...

"began establishing missions along the major Amazon River

The Amazon River (, ; es, Río Amazonas, pt, Rio Amazonas) in South America is the largest river by discharge volume of water in the world, and the disputed longest river system in the world in comparison to the Nile.

The headwaters of t ...

tributaries," which forcibly relocated large subsets of the Indigenous population into new colonial settlements:Amerindian groups were relocated into large settlements, called ''aldeias'', where their daily activities could be closely supervised, their souls could be saved, and their labor could be put to new tasks, such as raising cattle. In the ''aldeias'', natives were deprived of their tribal identity under the homogenizing influence of the missionaries. Compelled to communicate with whites and other natives in the ''lingua geral'', tribal Amerindians were gradually transformed into 'generic Indians' or ''tapuios''.The term ''tapuio'' "originally meant 'slave'", though soon afterward referred to detribalized and Christianized indigenous people who had assimilated into "colonial society", defined as such by their place of residence and proximity to colonial society. It has been used interchangeably with '' caboclo'', recognized as a derogatory term "equivalent to half-breed" or "of mixed blood", as well as ''carijó'', which also referred to "detribalized Indians". These labels differed from ''gentio'', a similarly derogatory term which referred to unconverted and non-assimilated Indigenous people.MacMillan 1995, 10-11. Slave expeditions by the ''bandeirantes'' continued throughout the eighteenth century with the intention of stealing precious metals, especially gold, from the interior, which further led to "the acquisition of land grants, official appointments, and other rewards and honors" for white male settlers. At the same time, "Indians seized in confrontations with colonists were used as mining, agricultural, and domestic laborers", while others, and especially Indigenous women, faced

rape

Rape is a type of sexual assault usually involving sexual intercourse or other forms of sexual penetration carried out against a person without their consent. The act may be carried out by physical force, coercion, abuse of authority, or ...

and sexual assault.

While the expanding network of Jesuit missions "provided a measure of protection from the slavers who made annual expeditions into the interior," they simultaneously altered "the mental and material bases of Amerindian culture forever." While ''tapuios'' were "nominally free" (or free in name) at the missions, they were actually "obliged to provide labor to royal authorities and to colonists, a practice that frequently deteriorated into forced work hardly distinguishable from outright slavery." The ''aldeias'' also proliferated the "spread of European diseases, such as whooping cough, influenza