Derek Walcott on:

[Wikipedia]

[Google]

[Amazon]

Sir Derek Alton Walcott (23 January 1930 – 17 March 2017) was a

, ''Trinidad Express Newspapers'', 30 April 2011. the 2010

"TS Eliot prize goes to Derek Walcott for 'moving and technically flawless' work"

''The Guardian'', 24 January 2011. and the Griffin Trust For Excellence in Poetry Lifetime Recognition Award in 2015.

"Derek Walcott, The Art of Poetry No. 37"

''

Academy of American Poets. He later commented:

After graduation, Walcott moved to Trinidad in 1953, where he became a critic, teacher and journalist. He founded the

After graduation, Walcott moved to Trinidad in 1953, where he became a critic, teacher and journalist. He founded the

"Derek Walcott"

essay: Spring 2000,

ENotes.

Walcott died at his home in Cap Estate, St. Lucia, on 17 March 2017. He was 87. He was given a state funeral on Saturday, 25 March, with a service at the

Walcott died at his home in Cap Estate, St. Lucia, on 17 March 2017. He was 87. He was given a state funeral on Saturday, 25 March, with a service at the

Winners – Anisfield-Wolf Book Award. * 2008: Honorary doctorate from the

British Council writers' profile

works listing, critical review

Profile, poems written and audio

at Poetry Archive

Profile and poems

at Poetry Foundation

Profile, poems audio and written

Poetry of American Poets

Profile, interviews, articles, archive

"Derek Walcott, The Art of Poetry No. 37"

''The Paris Review'', Winter 1986

Lannan Foundation Reading and Conversation With Glyn Maxwell

November 2002 (audio). * Biography available i

Saint Lucians and the Order of CARICOM

*

Appearance on ''Desert Island Discs''

Saint Lucia

Saint Lucia ( acf, Sent Lisi, french: Sainte-Lucie) is an island country of the West Indies in the eastern Caribbean. The island was previously called Iouanalao and later Hewanorra, names given by the native Arawaks and Caribs, two Ameri ...

n poet and playwright. He received the 1992 Nobel Prize in Literature. His works include the Homeric

Homer (; grc, Ὅμηρος , ''Hómēros'') (born ) was a Greek poet who is credited as the author of the ''Iliad'' and the ''Odyssey'', two epic poems that are foundational works of ancient Greek literature. Homer is considered one of the ...

epic poem

An epic poem, or simply an epic, is a lengthy narrative poem typically about the extraordinary deeds of extraordinary characters who, in dealings with gods or other superhuman forces, gave shape to the mortal universe for their descendants.

...

''Omeros

' is an epic poem by Saint Lucian writer Derek Walcott, first published in 1990. The work is divided into seven "books" containing a total of sixty-four chapters. Many critics view ''Omeros'' as Walcott's finest work.

In 2022, it was included ...

'' (1990), which many critics view "as Walcott's major achievement." In addition to winning the Nobel Prize, Walcott received many literary awards over the course of his career, including an Obie Award

The Obie Awards or Off-Broadway Theater Awards are annual awards originally given by ''The Village Voice'' newspaper to theatre artists and groups in New York City. In September 2014, the awards were jointly presented and administered with the ...

in 1971 for his play '' Dream on Monkey Mountain'', a MacArthur Foundation

The John D. and Catherine T. MacArthur Foundation is a private foundation that makes grants and impact investments to support non-profit organizations in approximately 50 countries around the world. It has an endowment of $7.0 billion and p ...

"genius" award, a Royal Society of Literature

The Royal Society of Literature (RSL) is a learned society founded in 1820, by King George IV, to "reward literary merit and excite literary talent". A charity that represents the voice of literature in the UK, the RSL has about 600 Fellows, ele ...

Award, the Queen's Medal for Poetry, the inaugural OCM Bocas Prize for Caribbean Literature,"Derek Walcott wins OCM Bocas Prize", ''Trinidad Express Newspapers'', 30 April 2011. the 2010

T. S. Eliot Prize

The T. S. Eliot Prize for Poetry is a prize that was, for many years, awarded by the Poetry Book Society (UK) to "the best collection of new verse in English first published in the UK or the Republic of Ireland" in any particular year. The Priz ...

for his book of poetry ''White Egrets''Charlotte Higgins"TS Eliot prize goes to Derek Walcott for 'moving and technically flawless' work"

''The Guardian'', 24 January 2011. and the Griffin Trust For Excellence in Poetry Lifetime Recognition Award in 2015.

Early life and childhood

Walcott was born and raised inCastries

Castries is the capital and largest city of Saint Lucia, an island country in the Caribbean. The urban area has a population of approximately 20,000, while the eponymous district has a population of 70,000, as at May 2013. The city stretches o ...

, Saint Lucia

Saint Lucia ( acf, Sent Lisi, french: Sainte-Lucie) is an island country of the West Indies in the eastern Caribbean. The island was previously called Iouanalao and later Hewanorra, names given by the native Arawaks and Caribs, two Ameri ...

, in the West Indies

The West Indies is a subregion of North America, surrounded by the North Atlantic Ocean and the Caribbean Sea that includes 13 independent island countries and 18 dependencies and other territories in three major archipelagos: the Greate ...

, the son of Alix (Maarlin) and Warwick Walcott. He had a twin brother, the playwright Roderick Walcott, and a sister, Pamela Walcott. His family is of English, Dutch and African descent, reflecting the complex colonial history of the island that he explores in his poetry. His mother, a teacher, loved the arts and often recited poetry around the house. Edward Hirsch"Derek Walcott, The Art of Poetry No. 37"

''

The Paris Review

''The Paris Review'' is a quarterly English-language literary magazine established in Paris in 1953 by Harold L. Humes, Peter Matthiessen, and George Plimpton. In its first five years, ''The Paris Review'' published works by Jack Kerouac, Phi ...

'', Issue 101, Winter 1986. His father was a civil servant

The civil service is a collective term for a sector of government composed mainly of career civil servants hired on professional merit rather than appointed or elected, whose institutional tenure typically survives transitions of political leaders ...

and a talented painter. He died when Walcott and his brother were one year old, and were left to be raised by their mother. Walcott was brought up in Methodist schools. His mother, who was a teacher at a Methodist elementary school, provided her children with an environment where their talents could be nurtured. Walcott's family was part of a minority Methodist community, who felt overshadowed by the dominant Catholic culture of the island established during French colonial rule.

As a young man Walcott trained as a painter, mentored by Harold Simmons, whose life as a professional artist provided an inspiring example for him. Walcott greatly admired Cézanne and Giorgione

Giorgione (, , ; born Giorgio Barbarelli da Castelfranco; 1477–78 or 1473–74 – 17 September 1510) was an Italian painter of the Venetian school during the High Renaissance, who died in his thirties. He is known for the elusive poetic quali ...

and sought to learn from them. Walcott's painting was later exhibited at the Anita Shapolsky Gallery

The Anita Shapolsky Gallery is an art gallery that was founded in 1982 by Anita Shapolsky. It is currently located at 152 East 65th Street, on Manhattan's Upper East Side, in New York City.

The gallery specializes in 1950s and 1960s abstract e ...

in New York City, along with the art of other writers, in a 2007 exhibition named ''The Writer's Brush: Paintings and Drawing by Writers''.

He studied as a writer, becoming "an elated, exuberant poet madly in love with English" and strongly influenced by modernist poets such as T. S. Eliot and Ezra Pound

Ezra Weston Loomis Pound (30 October 1885 – 1 November 1972) was an expatriate American poet and critic, a major figure in the early modernist poetry movement, and a Fascism, fascist collaborator in Italy during World War II. His works ...

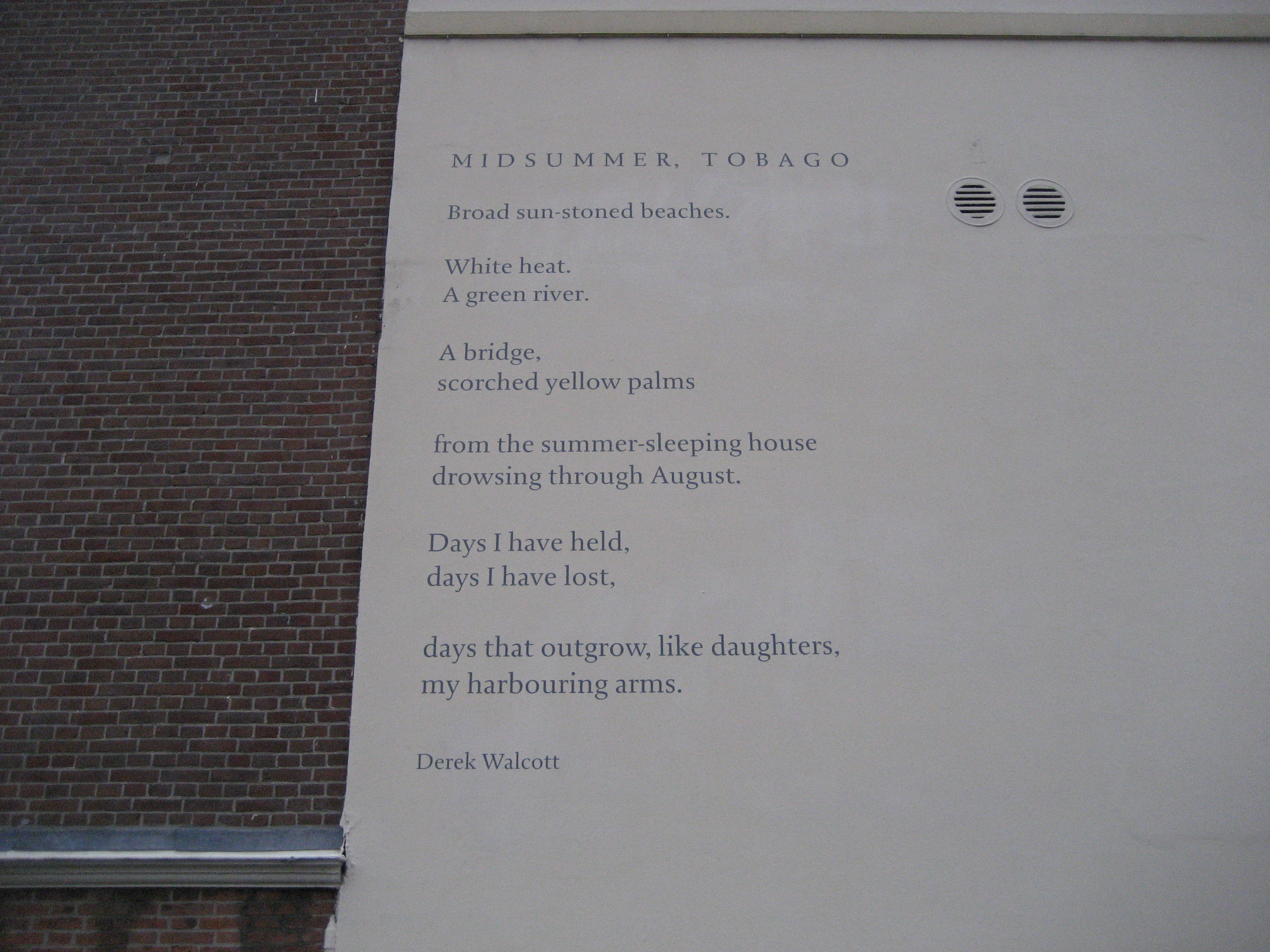

. Walcott had an early sense of a vocation as a writer. In the poem "Midsummer" (1984), he wrote:

At 14, Walcott published his first poem, aForty years gone, in my island childhood, I felt that the gift of poetry had made me one of the chosen, that all experience was kindling to the fire of the Muse.

Miltonic

John Milton (9 December 1608 – 8 November 1674) was an English poet and intellectual. His 1667 epic poem ''Paradise Lost'', written in blank verse and including over ten chapters, was written in a time of immense religious flux and political ...

, religious poem, in the newspaper ''The Voice of St Lucia''. An English Catholic priest condemned the Methodist-inspired poem as blasphemous in a response printed in the newspaper. By 19, Walcott had self-published his first two collections with the aid of his mother, who paid for the printing: ''25 Poems'' (1948) and ''Epitaph for the Young: XII Cantos'' (1949). He sold copies to his friends and covered the costs."Derek Walcott"Academy of American Poets. He later commented:

I went to my mother and said, "I’d like to publish a book of poems, and I think it's going to cost me two hundred dollars." She was just a seamstress and a schoolteacher, and I remember her being very upset because she wanted to do it. Somehow she got it—a lot of money for a woman to have found on her salary. She gave it to me, and I sent off toThe influential Bajan poetTrinidad Trinidad is the larger and more populous of the two major islands of Trinidad and Tobago. The island lies off the northeastern coast of Venezuela and sits on the continental shelf of South America. It is often referred to as the southernmos ...and had the book printed. When the books came back I would sell them to friends. I made the money back.

Frank Collymore

Frank Appleton Collymore MBE (7 January 1893 – 17 July 1980) was a Barbadian literary editor, writer, poet, stage performer and painter. His nickname was "Barbadian Man of the Arts". He also taught for 50 years at Combermere School, where he s ...

critically supported Walcott's early work.

After attending high school at Saint Mary's College, he received a scholarship to study at the University College of the West Indies

The University of the West Indies (UWI), originally University College of the West Indies, is a public university system established to serve the higher education needs of the residents of 17 English-speaking countries and territories in th ...

in Kingston, Jamaica

Kingston is the capital and largest city of Jamaica, located on the southeastern coast of the island. It faces a natural harbour protected by the Palisadoes, a long sand spit which connects the town of Port Royal and the Norman Manley Inte ...

.

Career

After graduation, Walcott moved to Trinidad in 1953, where he became a critic, teacher and journalist. He founded the

After graduation, Walcott moved to Trinidad in 1953, where he became a critic, teacher and journalist. He founded the Trinidad Theatre Workshop Trinidad Theatre Workshop was founded in 1959, by 1992 Nobel Laureate Derek Walcott, with his twin brother Roderick Walcott and performers including Beryl McBurnie, Errol Jones and Stanley Marshall, and started at the Little Carib Theatre before m ...

in 1959 and remained active with its board of directors.

Exploring the Caribbean and its history in a colonialist and post-colonialist context, his collection ''In a Green Night: Poems 1948–1960'' (1962) attracted international attention. His play '' Dream on Monkey Mountain'' (1970) was produced on NBC-TV in the United States the year it was published. Makak is the protagonist in this play; and "Makak‟s condition represents the condition of the colonized natives under the oppressive forces of the powerful colonizers". In 1971 it was produced by the Negro Ensemble Company

The Negro Ensemble Company (NEC) is a New York City-based theater company and workshop established in 1967 by playwright Douglas Turner Ward, producer-actor Robert Hooks, and theater manager Gerald S. Krone, with funding from the Ford Foundation ...

off-Broadway in New York City; it won an Obie Award

The Obie Awards or Off-Broadway Theater Awards are annual awards originally given by ''The Village Voice'' newspaper to theatre artists and groups in New York City. In September 2014, the awards were jointly presented and administered with the ...

that year for "Best Foreign Play". The following year, Walcott won an OBE from the British government for his work.

He was hired as a teacher by Boston University

Boston University (BU) is a private research university in Boston, Massachusetts. The university is nonsectarian, but has a historical affiliation with the United Methodist Church. It was founded in 1839 by Methodists with its original cam ...

in the United States, where he founded the Boston Playwrights' Theatre

Boston Playwrights' Theatre (BPT) is a small professional theatre in Boston, Massachusetts. Led by artistic director Megan Sandberg-Zakian, it is the home of the Graduate Playwriting Program at Boston University. As a venue, BPT rents its space to ...

in 1981. That year he also received a MacArthur Foundation Fellowship

The MacArthur Fellows Program, also known as the MacArthur Fellowship and commonly but unofficially known as the "Genius Grant", is a prize awarded annually by the John D. and Catherine T. MacArthur Foundation typically to between 20 and 30 indi ...

in the United States. Walcott taught literature and writing at Boston University for more than two decades, publishing new books of poetry and plays on a regular basis. Walcott retired from his position at Boston University in 2007. He became friends with other poets, including the Russian expatriate Joseph Brodsky

Iosif Aleksandrovich Brodsky (; russian: link=no, Иосиф Александрович Бродский ; 24 May 1940 – 28 January 1996) was a Russian and American poet and essayist.

Born in Leningrad (now Saint Petersburg), USSR in 1940, ...

, who lived and worked in the U.S. after being exiled in the 1970s, and the Irishman Seamus Heaney

Seamus Justin Heaney (; 13 April 1939 – 30 August 2013) was an Irish poet, playwright and translator. He received the 1995 Nobel Prize in Literature.

, who also taught in Boston.

Walcott's epic poem ''Omeros

' is an epic poem by Saint Lucian writer Derek Walcott, first published in 1990. The work is divided into seven "books" containing a total of sixty-four chapters. Many critics view ''Omeros'' as Walcott's finest work.

In 2022, it was included ...

'' (1990), which loosely echoes and refers to characters from the ''Iliad

The ''Iliad'' (; grc, Ἰλιάς, Iliás, ; "a poem about Ilium") is one of two major ancient Greek epic poems attributed to Homer. It is one of the oldest extant works of literature still widely read by modern audiences. As with the ''Ody ...

'', has been critically praised as his "major achievement." The book received praise from publications such as ''The Washington Post

''The Washington Post'' (also known as the ''Post'' and, informally, ''WaPo'') is an American daily newspaper published in Washington, D.C. It is the most widely circulated newspaper within the Washington metropolitan area and has a large n ...

'' and ''The New York Times Book Review

''The New York Times Book Review'' (''NYTBR'') is a weekly paper-magazine supplement to the Sunday edition of ''The New York Times'' in which current non-fiction and fiction books are reviewed. It is one of the most influential and widely rea ...

'', which chose ''Omeros'' as one of its "Best Books of 1990".

Walcott was awarded the Nobel Prize in Literature

)

, image = Nobel Prize.png

, caption =

, awarded_for = Outstanding contributions in literature

, presenter = Swedish Academy

, holder = Annie Ernaux (2022)

, location = Stockholm, Sweden

, year = 1901

, ...

in 1992, the second Caribbean writer to receive the honour after Saint-John Perse, who was born in Guadeloupe

Guadeloupe (; ; gcf, label= Antillean Creole, Gwadloup, ) is an archipelago and overseas department and region of France in the Caribbean. It consists of six inhabited islands— Basse-Terre, Grande-Terre, Marie-Galante, La Désirade, and ...

, received the award in 1960. The Nobel committee described Walcott's work as "a poetic oeuvre of great luminosity, sustained by a historical vision, the outcome of a multicultural commitment". He won an Anisfield-Wolf Book Award The Anisfield-Wolf Book Award is an American literary award dedicated to honoring written works that make important contributions to the understanding of racism and the appreciation of the rich diversity of human culture. Established in 1935 by Clev ...

for Lifetime Achievement in 2004.

His later poetry collections include ''Tiepolo's Hound'' (2000), illustrated with copies of his watercolors; ''The Prodigal'' (2004), and ''White Egrets'' (2010), which received the T.S. Eliot Prize and the 2011 OCM Bocas Prize for Caribbean Literature.

Derek Walcott has been a Professor of Creative Writing at the University of Nevada, Las Vegas

The University of Nevada, Las Vegas (UNLV) is a public land-grant research university in Paradise, Nevada. The campus is about east of the Las Vegas Strip. It was formerly part of the University of Nevada from 1957 to 1969. It includes th ...

, In 2008, Walcott gave the first Cola Debrot Lectures In 2009, Walcott began a three-year distinguished scholar-in-residence position at the University of Alberta

The University of Alberta, also known as U of A or UAlberta, is a Public university, public research university located in Edmonton, Alberta, Canada. It was founded in 1908 by Alexander Cameron Rutherford,"A Gentleman of Strathcona – Alexande ...

. In 2010, he became Professor of Poetry at the University of Essex

The University of Essex is a public research university in Essex, England. Established by royal charter in 1965, Essex is one of the original plate glass universities. Essex's shield consists of the ancient arms attributed to the Kingdom of Es ...

.

As a part of St Lucia's Independence Day celebrations, in February 2016, he became one of the first knights of the Order of Saint Lucia

The Order of Saint Lucia is an order of chivalry established in 1986 by Elizabeth II. The Order comprises seven classes. In decreasing order of seniority, these are:

* ''Grand Cross of the Order of Saint Lucia'' (GCSL)

* ''Knight/Dame Commander ...

.

Writing

Themes

Methodism

Methodism, also called the Methodist movement, is a group of historically related denominations of Protestant Christianity whose origins, doctrine and practice derive from the life and teachings of John Wesley. George Whitefield and John's b ...

and spirituality have played a significant role from the beginning in Walcott's work. He commented: "I have never separated the writing of poetry from prayer. I have grown up believing it is a vocation

A vocation () is an occupation to which a person is especially drawn or for which they are suited, trained or qualified. People can be given information about a new occupation through student orientation. Though now often used in non-religious ...

, a religious vocation." Describing his writing process, he wrote: "the body feels it is melting into what it has seen… the 'I' not being important. That is the ecstasy...Ultimately, it's what Yeats

William Butler Yeats (13 June 186528 January 1939) was an Irish poet, dramatist, writer and one of the foremost figures of 20th-century literature. He was a driving force behind the Irish Literary Revival and became a pillar of the Irish liter ...

says: 'Such a sweetness flows into the breast that we laugh at everything and everything we look upon is blessed.' That’s always there. It’s a benediction, a transference. It’s gratitude, really. The more of that a poet keeps, the more genuine his nature." He also notes, "if one thinks a poem is coming on...you do make a retreat, a withdrawal into some kind of silence that cuts out everything around you. What you’re taking on is really not a renewal of your identity but actually a renewal of your anonymity."

Influences

Walcott said his writing was influenced by the work of the American poetsRobert Lowell

Robert Traill Spence Lowell IV (; March 1, 1917 – September 12, 1977) was an American poet. He was born into a Boston Brahmin family that could trace its origins back to the '' Mayflower''. His family, past and present, were important subjects ...

and Elizabeth Bishop

Elizabeth Bishop (February 8, 1911 – October 6, 1979) was an American poet and short-story writer. She was Consultant in Poetry to the Library of Congress from 1949 to 1950, the Pulitzer Prize winner for Poetry in 1956, the National Book Awar ...

, who were also friends.

Playwriting

He published more than twenty plays, the majority of which have been produced by theTrinidad Theatre Workshop Trinidad Theatre Workshop was founded in 1959, by 1992 Nobel Laureate Derek Walcott, with his twin brother Roderick Walcott and performers including Beryl McBurnie, Errol Jones and Stanley Marshall, and started at the Little Carib Theatre before m ...

and have also been widely staged elsewhere. Many of them address, either directly or indirectly, the liminal status of the West Indies in the post-colonial period. Through poetry he also explores the paradoxes and complexities of this legacy.

Essays

In his 1970 essay "What the Twilight Says: An Overture", discussing art and theatre in his native region (from ''Dream on Monkey Mountain and Other Plays''), Walcott reflects on the West Indies as colonized space. He discusses the problems for an artist of a region with little in the way of trulyIndigenous

Indigenous may refer to:

*Indigenous peoples

*Indigenous (ecology), presence in a region as the result of only natural processes, with no human intervention

*Indigenous (band), an American blues-rock band

*Indigenous (horse), a Hong Kong racehorse ...

forms, and with little national or nationalist identity. He states: "We are all strangers here... Our bodies think in one language and move in another". The epistemological effects of colonization inform plays such as ''Ti-Jean and his Brothers''. Mi-Jean, one of the eponymous brothers, is shown to have much information, but to truly know nothing. Every line Mi-Jean recites is rote knowledge gained from the coloniser; he is unable to synthesize it or apply it to his life as a colonised person.

Walcott notes of growing up in West Indian culture:

What we were deprived of was also our privilege. There was a great joy in making a world that so far, up to then, had been undefined... My generation of West Indian writers has felt such a powerful elation at having the privilege of writing about places and people for the first time and, simultaneously, having behind them the tradition of knowing how well it can be done—by a Defoe, aWalcott identified as "absolutely a Caribbean writer", a pioneer, helping to make sense of the legacy of deep colonial damage. In such poems as "The Castaway" (1965) and in the play ''Dickens Charles John Huffam Dickens (; 7 February 1812 – 9 June 1870) was an English writer and social critic. He created some of the world's best-known fictional characters and is regarded by many as the greatest novelist of the Victorian er ..., aRichardson Richardson may refer to: People * Richardson (surname), an English and Scottish surname * Richardson Gang, a London crime gang in the 1960s * Richardson Dilworth, Mayor of Philadelphia (1956-1962) Places Australia * Richardson, Australian Capi ....

Pantomime

Pantomime (; informally panto) is a type of musical comedy stage production designed for family entertainment. It was developed in England and is performed throughout the United Kingdom, Ireland and (to a lesser extent) in other English-speakin ...

'' (1978), he uses the metaphors of shipwreck and Crusoe Crusoe may refer to:

Art, entertainment, and media

* ''Crusoe'' (film), a 1989 film by Caleb Deschanel based on the novel ''Robinson Crusoe''

* ''Crusoe'' (TV series), a 2008 television series based on the novel ''Robinson Crusoe''

* Crusoe the ...

to describe the culture and what is required of artists after colonialism and slavery: both the freedom and the challenge to begin again, salvage the best of other cultures and make something new. These images recur in later work as well. He writes: "If we continue to sulk and say, Look at what the slave-owner did, and so forth, we will never mature. While we sit moping or writing morose poems and novels that glorify a non-existent past, then time passes us by."

''Omeros''

Walcott's epic book-length poem ''Omeros

' is an epic poem by Saint Lucian writer Derek Walcott, first published in 1990. The work is divided into seven "books" containing a total of sixty-four chapters. Many critics view ''Omeros'' as Walcott's finest work.

In 2022, it was included ...

'' was published in 1990 to critical acclaim. The poem very loosely echoes and references Homer

Homer (; grc, Ὅμηρος , ''Hómēros'') (born ) was a Greek poet who is credited as the author of the ''Iliad'' and the ''Odyssey'', two epic poems that are foundational works of ancient Greek literature. Homer is considered one of the ...

and some of his major characters from ''The Iliad

The ''Iliad'' (; grc, Ἰλιάς, Iliás, ; "a poem about Ilium") is one of two major ancient Greek epic poems attributed to Homer. It is one of the oldest extant works of literature still widely read by modern audiences. As with the '' Ody ...

''. Some of the poem's major characters include the island fishermen Achille and Hector, the retired English officer Major Plunkett and his wife Maud, the housemaid Helen, the blind man Seven Seas (who symbolically represents Homer), and the author himself.

Although the main narrative of the poem takes place on the island of St. Lucia, where Walcott was born and raised, Walcott also includes scenes from Brookline, Massachusetts

Brookline is a town in Norfolk County, Massachusetts, in the United States, and part of the Boston metropolitan area. Brookline borders six of Boston's neighborhoods: Brighton, Allston, Fenway–Kenmore, Mission Hill, Jamaica Plain, and ...

(where Walcott was living and teaching at the time of the poem's composition), and the character Achille imagines a voyage from Africa onto a slave ship that is headed for the Americas; also, in Book Five of the poem, Walcott narrates some of his travel experiences in a variety of cities around the world, including Lisbon

Lisbon (; pt, Lisboa ) is the capital and largest city of Portugal, with an estimated population of 544,851 within its administrative limits in an area of 100.05 km2. Lisbon's urban area extends beyond the city's administrative limits w ...

, London, Dublin

Dublin (; , or ) is the capital and largest city of Ireland. On a bay at the mouth of the River Liffey, it is in the province of Leinster, bordered on the south by the Dublin Mountains, a part of the Wicklow Mountains range. At the 2016 ...

, Rome, and Toronto.

Composed in a variation on ''terza rima

''Terza rima'' (, also , ; ) is a rhyming verse form, in which the poem, or each poem-section, consists of tercets (three line stanzas) with an interlocking three-line rhyme scheme: The last word of the second line in one tercet provides the rh ...

'', the work explores the themes that run throughout Walcott's oeuvre: the beauty of the islands, the colonial burden, the fragmentation of Caribbean identity, and the role of the poet in a post-colonial world.Patrick Bixby"Derek Walcott"

essay: Spring 2000,

Emory University

Emory University is a private research university in Atlanta, Georgia. Founded in 1836 as "Emory College" by the Methodist Episcopal Church and named in honor of Methodist bishop John Emory, Emory is the second-oldest private institution of ...

. Retrieved 30 March 2012.

In this epic, Walcott advocates the need to return to traditions in order to challenge the modernity born out of colonialism.

Criticism and praise

Walcott's work has received praise from major poets includingRobert Graves

Captain Robert von Ranke Graves (24 July 1895 – 7 December 1985) was a British poet, historical novelist and critic. His father was Alfred Perceval Graves, a celebrated Irish poet and figure in the Gaelic revival; they were both Celt ...

, who wrote that Walcott "handles English with a closer understanding of its inner magic than most, if not any, of his contemporaries", and Joseph Brodsky

Iosif Aleksandrovich Brodsky (; russian: link=no, Иосиф Александрович Бродский ; 24 May 1940 – 28 January 1996) was a Russian and American poet and essayist.

Born in Leningrad (now Saint Petersburg), USSR in 1940, ...

, who praised Walcott's work, writing: "For almost forty years his throbbing and relentless lines kept arriving in the English language like tidal waves, coagulating into an archipelago of poems without which the map of modern literature would effectively match wallpaper. He gives us more than himself or 'a world'; he gives us a sense of infinity embodied in the language." Walcott noted that he, Brodsky, and the Irish poet Seamus Heaney

Seamus Justin Heaney (; 13 April 1939 – 30 August 2013) was an Irish poet, playwright and translator. He received the 1995 Nobel Prize in Literature.

, who all taught in the United States, were a band of poets "outside the American experience".

The poetry critic William Logan critiqued Walcott's work in a ''New York Times'' book review of Walcott's ''Selected Poems''. While he praised Walcott's writing in ''Sea Grapes'' and ''The Arkansas Testament'', Logan had mostly negative things to say about Walcott's poetry, calling ''Omeros'' "clumsy" and ''Another Life'' "pretentious." He concluded with "No living poet has written verse more delicately rendered or distinguished than Walcott, though few individual poems seem destined to be remembered."

Most reviews of Walcott's work are more positive. For instance, in ''The New Yorker

''The New Yorker'' is an American weekly magazine featuring journalism, commentary, criticism, essays, fiction, satire, cartoons, and poetry. Founded as a weekly in 1925, the magazine is published 47 times annually, with five of these issues ...

'' review of ''The Poetry of Derek Walcott'', Adam Kirsch

Adam Kirsch (born 1976) is an American poet and literary critic. He is on the seminar faculty of Columbia University's Center for American Studies, and has taught at YIVO.

Life and career

Kirsch was born in Los Angeles in 1976. He is the son of ...

had high praise for Walcott's oeuvre, describing his style in the following manner:

By combining the grammar of vision with the freedom of metaphor, Walcott produces a beautiful style that is also a philosophical style. People perceive the world on dual channels, Walcott’s verse suggests, through the senses and through the mind, and each is constantly seeping into the other. The result is a state of perpetual magical thinking, a kind of ''Kirsch calls ''Another Life'' Walcott's "first major peak" and analyzes the painterly qualities of Walcott's imagery from his earliest work through to later books such as ''Tiepolo's Hound''. Kirsch also explores the post-colonial politics in Walcott's work, calling him "the postcolonial writer par excellence". Kirsch calls the early poem "A Far Cry from Africa" a turning point in Walcott's development as a poet. Like Logan, Kirsch is critical of ''Omeros'', which he believes Walcott fails to successfully sustain over its entirety. Although ''Omeros'' is the volume of Walcott's that usually receives the most critical praise, Kirsch believes ''Midsummer'' to be his best book. His poetry, as spoken performance, appears briefly in the sampled sounds in the music album of the groupAlice in Wonderland ''Alice's Adventures in Wonderland'' (commonly ''Alice in Wonderland'') is an 1865 English novel by Lewis Carroll. It details the story of a young girl named Alice who falls through a rabbit hole into a fantasy world of anthropomorphic creatur ...'' world where concepts have bodies and landscapes are always liable to get up and start talking.

Dreadzone

Dreadzone are a British electronic music group. They have released eight studio albums, two live albums, and two compilations.

Career

Dreadzone were formed in London, England in 1993 when ex-Big Audio Dynamite drummer Greg Roberts teamed up ...

. Their track entitled "Captain Dread" from the album '' Second Light'' incorporates the fourth verse of Walcott's 1990 poem "The Schooner Flight".

In 2013 Dutch filmmaker Ida Does released ''Poetry is an Island'', a feature documentary film about Walcott's life and the ever-present influence of his birthplace of St Lucia

Saint Lucia ( acf, Sent Lisi, french: Sainte-Lucie) is an island country of the West Indies in the eastern Caribbean. The island was previously called Iouanalao and later Hewanorra, names given by the native Arawaks and Caribs, two Amerindi ...

.

Personal life

In 1954 Walcott married Fay Moston, a secretary, and they had a son, the St. Lucian painter Peter Walcott. The marriage ended in divorce in 1959. Walcott married a second time to Margaret Maillard in 1962, who worked as analmoner

An almoner (} ' (alms), via the popular Latin '.

History

Christians have historically been encouraged to donate one-tenth of their income as a tithe to their church and additional offerings as needed for the poor. The first deacons, mentioned ...

in a hospital. Together they had two daughters, Elizabeth Walcott-Hackshaw

Elizabeth Walcott-Hackshaw (born 1964) is a Trinidadian writer and academic, who is Professor of French Literature and Creative Writing at the University of the West Indies. Her writing encompasses both scholarly and creative work, and she has als ...

and Anna Walcott-Hardy, before divorcing in 1976. In 1976, Walcott married for a third time, to actress Norline Metivier; they divorced in 1993. His companion until his death was Sigrid Nama, a former art gallery owner.

Walcott was also known for his passion for traveling to countries around the world. He split his time between New York, Boston, and St. Lucia, and incorporated the influences of different locations into his pieces of work.

Allegations of sexual harassment

In 1982, a Harvard sophomore accused Walcott of sexual harassment in September 1981. She alleged that after she refused a sexual advance from him, she was given the only C in the class. In 1996 a student at Boston University sued Walcott for sexual harassment and "offensive sexual physical contact". The two reached a settlement. In 2009, Walcott was a leading candidate for the position ofOxford Professor of Poetry

The Professor of Poetry is an academic appointment at the University of Oxford. The chair was created in 1708 by an endowment from the estate of Henry Birkhead. The professorship carries an obligation to lecture, but is in effect a part-time p ...

. He withdrew his candidacy after reports of the accusations against him of sexual harassment from 1981 and 1996.

When the media learned that pages from an American book on the topic were sent anonymously to a number of Oxford academics, this aroused their interest in the university decisions. Ruth Padel, also a leading candidate, was elected to the post. Within days, ''The Daily Telegraph

''The Daily Telegraph'', known online and elsewhere as ''The Telegraph'', is a national British daily broadsheet newspaper published in London by Telegraph Media Group and distributed across the United Kingdom and internationally.

It was f ...

'' reported that she had alerted journalists to the harassment cases. Under severe media and academic pressure, Padel resigned. Padel was the first woman to be elected to the Oxford post, and some journalists attributed the criticism of her to misogyny and a gender war at Oxford. They said that a male poet would not have been so criticized, as she had reported published information, not rumour.

Numerous respected poets, including Seamus Heaney

Seamus Justin Heaney (; 13 April 1939 – 30 August 2013) was an Irish poet, playwright and translator. He received the 1995 Nobel Prize in Literature.

and Al Alvarez

Alfred Alvarez (5 August 1929 – 23 September 2019) was an English poet, novelist, essayist and critic who published under the name A. Alvarez and Al Alvarez.

Background

Alfred Alvarez was born in London, to an Ashkenazic Jewish mother and a ...

, published a letter of support for Walcott in ''The Times Literary Supplement

''The Times Literary Supplement'' (''TLS'') is a weekly literary review published in London by News UK, a subsidiary of News Corp.

History

The ''TLS'' first appeared in 1902 as a supplement to ''The Times'' but became a separate publication ...

,'' and criticized the press furor. Other commentators suggested that both poets were casualties of the media interest in an internal university affair, because the story "had everything, from sex claims to allegations of character assassination"."Oxford Professor of Poetry"ENotes.

Simon Armitage

Simon Robert Armitage (born 26 May 1963) is an English poet, playwright, musician and novelist. He was appointed Poet Laureate on 10 May 2019. He is professor of poetry at the University of Leeds.

He has published over 20 collections of poet ...

and other poets expressed regret at Padel's resignation.

Death

Walcott died at his home in Cap Estate, St. Lucia, on 17 March 2017. He was 87. He was given a state funeral on Saturday, 25 March, with a service at the

Walcott died at his home in Cap Estate, St. Lucia, on 17 March 2017. He was 87. He was given a state funeral on Saturday, 25 March, with a service at the Cathedral Basilica of the Immaculate Conception in Castries

The Cathedral Basilica of the Immaculate Conception, located in Derek Walcott Square, Castries, Saint Lucia, is the seat of the Archbishop of the Roman Catholic Archdiocese of Castries, currently Robert Rivas. The cathedral is named after Mary ...

and burial at Morne Fortune

Morne Fortune is a hill and residential area located south of Castries, Saint Lucia, in the West Indies.

Originally known as Morne Dubuc, it was renamed Morne Fortuné in 1765 when the French moved their military headquarters and government admi ...

.

Legacy

In 1993, a public square and park located in central Castries, Saint Lucia, was namedDerek Walcott Square

Derek Walcott Square (formerly Columbus Square) is a public square and park located in central Castries, Saint Lucia.

The square is bounded by Bourbon, Brazil, Laborie and Micoud Streets.

The Cathedral of the Immaculate Conception and the Castr ...

. A documentary film, ''Poetry Is an Island: Derek Walcott'', by filmmaker Ida Does

Ida Does (born 1955) is a Surinamese-born, Dutch journalist, writer, and documentary filmmaker. After working at Omroep West (TV West) as a reporter, editor-in-chief, and program director, she began making independent films, mainly focused on art ...

, was produced to honor him and his legacy in 2013.

The Saint Lucia National Trust acquired Walcott's childhood home at 17 Chaussée Road, Castries, in November 2015, renovating it before opening it to the public as Walcott House in January 2016.

In January 2020 the Sir Arthur Lewis Community College

Sir Arthur Lewis Community College is the only community college in the island country of Saint Lucia. The college was established in 1985 and is named after Saint Lucian economist and Nobel laureate Sir Arthur Lewis

Sir William Arthur Lewis ...

in St. Lucia announced that Walcott's books on Caribbean Literature and poetry have been donated to its Library.

Awards and honours

* 1969:Cholmondeley Award

The Cholmondeley Awards () are annual awards for poetry given by the Society of Authors in the United Kingdom. Awards honour distinguished poets, from a fund endowed by the Dowager Marchioness of Cholmondeley in 1966. Since 1991 the award has be ...

* 1971: Obie Award

The Obie Awards or Off-Broadway Theater Awards are annual awards originally given by ''The Village Voice'' newspaper to theatre artists and groups in New York City. In September 2014, the awards were jointly presented and administered with the ...

for Best Foreign Play (for ''Dream on Monkey Mountain'')

* 1972: Officer of the Order of the British Empire

The Most Excellent Order of the British Empire is a British order of chivalry, rewarding contributions to the arts and sciences, work with charitable and welfare organisations,

and public service outside the civil service. It was established ...

* 1981: MacArthur Foundation Fellowship ("genius award")

* 1988: Queen's Gold Medal for Poetry

The Queen's Gold Medal for Poetry is awarded for a book of verse published by someone in any of the Commonwealth realms. Originally the award was open only to British subjects living in the United Kingdom, but in 1985 the scope was extended to in ...

* 1990: Arts Council of Wales

The Arts Council of Wales (ACW; cy, Cyngor Celfyddydau Cymru) is a Welsh Government-sponsored body, responsible for funding and developing the arts in Wales.

Established within the Arts Council of Great Britain in 1946, as the Welsh Arts C ...

International Writers Prize

* 1990: W. H. Smith Literary Award (for poetry ''Omeros'')

* 1992: Nobel Prize in Literature

)

, image = Nobel Prize.png

, caption =

, awarded_for = Outstanding contributions in literature

, presenter = Swedish Academy

, holder = Annie Ernaux (2022)

, location = Stockholm, Sweden

, year = 1901

, ...

* 2004: Anisfield-Wolf Book Award The Anisfield-Wolf Book Award is an American literary award dedicated to honoring written works that make important contributions to the understanding of racism and the appreciation of the rich diversity of human culture. Established in 1935 by Clev ...

for Lifetime Achievement"Derek Walcott, 2004 – Lifetime Achievement"Winners – Anisfield-Wolf Book Award. * 2008: Honorary doctorate from the

University of Essex

The University of Essex is a public research university in Essex, England. Established by royal charter in 1965, Essex is one of the original plate glass universities. Essex's shield consists of the ancient arms attributed to the Kingdom of Es ...

* 2011: T. S. Eliot Prize

The T. S. Eliot Prize for Poetry is a prize that was, for many years, awarded by the Poetry Book Society (UK) to "the best collection of new verse in English first published in the UK or the Republic of Ireland" in any particular year. The Priz ...

(for poetry collection ''White Egrets'')

* 2011: OCM Bocas Prize for Caribbean Literature (for ''White Egrets'')

* 2015: Griffin Trust For Excellence in Poetry Lifetime Recognition Award

* 2016: Knight Commander of the Order of Saint Lucia

List of works

* *Poetry collections

* 1948: ''25 Poems'' * 1949: ''Epitaph for the Young: Xll Cantos'' * 1951: ''Poems'' * 1962: ''In a Green Night: Poems 1948—60'' * 1964: ''Selected Poems'' * 1965: ''The Castaway and Other Poems'' * 1969: ''The Gulf and Other Poems'' * 1973: ''Another Life'' * 1976: ''Sea Grapes'' * 1979: ''The Star-Apple Kingdom'' * 1981: ''Selected Poetry'' * 1981: ''The Fortunate Traveller'' * 1983: ''The Caribbean Poetry of Derek Walcott and the Art of Romare Bearden'' * 1984: ''Midsummer'' * 1986 ''Collected Poems, 1948–1984'', featuring " Love After Love" * 1987: ''The Arkansas Testament'' * 1990: ''Omeros

' is an epic poem by Saint Lucian writer Derek Walcott, first published in 1990. The work is divided into seven "books" containing a total of sixty-four chapters. Many critics view ''Omeros'' as Walcott's finest work.

In 2022, it was included ...

''

* 1997: ''The Bounty''

* 2000: ''Tiepolo's Hound,'' includes Walcott's watercolors

* 2004: ''The Prodigal''

* 2007: ''Selected Poems'' (edited, selected, and with an introduction by Edward Baugh)

* 2010: ''White Egrets''

* 2014: ''The Poetry of Derek Walcott 1948–2013''

* 2016: ''Morning, Paramin'' (illustrated by Peter Doig)

Plays

* 1950: '' Henri Christophe: A Chronicle in Seven Scenes'' * 1952: '' Harry Dernier: A Play for Radio Production'' * 1953: ''Wine of the Country'' * 1954: ''The Sea at Dauphin: A Play in One Act'' * 1957: ''Ione'' * 1958: ''Drums and Colours: An Epic Drama'' * 1958: ''Ti-Jean and His Brothers'' * 1966: ''Malcochon: or, Six in the Rain'' * 1967: '' Dream on Monkey Mountain'' * 1970: ''In a Fine Castle'' * 1974: ''The Joker of Seville'' * 1974: ''The Charlatan'' * 1976: ''O Babylon!'' * 1977: ''Remembrance'' * 1978: ''Pantomime'' * 1980: ''The Joker of Seville and O Babylon!: Two Plays'' * 1982: ''The Isle Is Full of Noises'' * 1984: ''The Haitian Earth'' * 1986: Three Plays: '' The Last Carnival'', ''Beef, No Chicken

''Beef, No Chicken'' is a two-act play by Caribbean playwright Derek Walcott. The play is set in the town of Couva, in Trinidad and Tobago. It follows restaurant owner Otto Hogan, whose refusal to accept graft delays the building of a highway thr ...

'', and ''A Branch of the Blue Nile''

* 1991: ''Steel''

* 1993: ''Odyssey: A Stage Version''

* 1997: '' The Capeman'' (book and lyrics, both in collaboration with Paul Simon

Paul Frederic Simon (born October 13, 1941) is an American musician, singer, songwriter and actor whose career has spanned six decades. He is one of the most acclaimed songwriters in popular music, both as a solo artist and as half of folk roc ...

)

* 2002: ''Walker and The Ghost Dance''

* 2011: ''Moon-Child''

* 2014: ''O Starry Starry Night''

Other books

* 1990: ''The Poet in the Theatre'', Poetry Book Society (London) * 1993: ''The Antilles: Fragments of Epic Memory'' Farrar, Straus (New York) * 1996: ''Conversations with Derek Walcott'', University of Mississippi (Jackson, MS) * 1996: (With Joseph Brodsky and Seamus Heaney) ''Homage to Robert Frost'', Farrar, Straus (New York) * 1998: ''What the Twilight Says'' (essays), Farrar, Straus (New York, NY) * 2002: ''Walker and Ghost Dance'', Farrar, Straus (New York, NY) * 2004: ''Another Life: Fully Annotated'', Lynne Rienner Publishers (Boulder, CO)See also

*Black Nobel Prize laureates

The Nobel Prize is an annual, international prize first awarded in 1901 for achievements in Physics, Chemistry, Physiology or Medicine, Literature, and Peace. An associated prize in Economics has been awarded since 1969.

* " Love After Love", a poem by Derek Walcott

* Omeros

' is an epic poem by Saint Lucian writer Derek Walcott, first published in 1990. The work is divided into seven "books" containing a total of sixty-four chapters. Many critics view ''Omeros'' as Walcott's finest work.

In 2022, it was included ...

, epic poetry by Derek Walcott

* Caribbean Epic

References

Further reading

* Abani, Chris. ''The myth of fingerprints: Signifying as displacement in Derek Walcott's “Omeros”.'' University of Southern California, PhD dissertation. 2006. * Abodunrin, Femi. "The Muse of History: Derek Walcott and the Topos of naming in West Indian Writing." ''Journal of West Indian Literature'' 7, no. 1 (1996): 54-77. * Amany Abdelkahhar Aldardeer Ahmed, Amany. "The Quest for a Cultural Identity in Derek Walcott's Another Life." مجلة کلية الآداب 57, no. 3 (2020): 101-146. * Baer, William, ed. ''Conversations with Derek Walcott''. Jackson: University Press of Mississippi, 1996. * Baugh, Edward, ''Derek Walcott''. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 2006. * Breslin, Paul, ''Nobody's Nation: Reading Derek Walcott''. Chicago: University of Chicago Press, 2001. * Brown, Stewart, ed., ''The Art of Derek Walcott''. Chester Springs, PA.: Dufour, 1991; Bridgend: Seren Books, 1992. * Burnett, Paula, ''Derek Walcott: Politics and Poetics''. Gainesville: University Press of Florida, 2001. * Figueroa, John J. "Some subtleties of the isle: A commentary on certain aspects of Derek Walcott's sonnet sequence. ''Tales of the Islands.'' (1976): 190-228. * Fumagalli, Maria Cristina, ''The Flight of the Vernacular: Seamus Heaney, Derek Walcott and the Impress of Dante''. Amsterdam-New York: Rodopi, 2001. * Fumagalli, Maria Cristina, ''Agenda'' 39:1–3 (2002–03), Special Issue on Derek Walcott. Includes Derek Walcott's "Epitaph for the Young" (1949), republished here in its entirety. * Goddar, Horace I. "Untangling the thematic threads: Derek Walcott's poetry." ''Kola'' 21, no. 1 (2009): 120-131. * Goddard, Horace I. "The Rediscovery of Ancestral Experience in Derek Walcott's Early Poetry." ''Kola'' 29, no. 2 (2017): 24-40. * Hamner, Robert D., ''Derek Walcott''. Updated edition. Twayne's World Authors Series. TWAS 600. New York: Twayne, 1993. * Izevbaye, D. S. "The Exile and the Prodigal: Derek Walcott as West Indian Poet." ''Caribbean Quarterly'' 26, no. 1-2 (1980): 70-82. * King, Bruce, ''Derek Walcott and West Indian Drama: "Not Only a Playwright But a Company": The Trinidad Theatre Workshop 1959–1993''. Oxford: Clarendon Press, 1995. * King, Bruce, ''Derek Walcott, A Caribbean Life''. Oxford: Oxford University Press, 2000. * Marks, Susan Jane. ''That terrible vowel, that I: autobiography and Derek Walcott's Another life.'' Master's thesis, University of Cape Town, 1989. * * * Terada, Rei, ''Derek Walcott's Poetry: American Mimicry''. Boston: Northeastern University Press, 1992. * Thieme, John, ''Derek Walcott''. Manchester: Manchester University Press, 1999.External links

British Council writers' profile

works listing, critical review

Profile, poems written and audio

at Poetry Archive

Profile and poems

at Poetry Foundation

Profile, poems audio and written

Poetry of American Poets

Emory University

Emory University is a private research university in Atlanta, Georgia. Founded in 1836 as "Emory College" by the Methodist Episcopal Church and named in honor of Methodist bishop John Emory, Emory is the second-oldest private institution of ...

Profile, interviews, articles, archive

Prague Writers' Festival

The Prague Writers' Festival (PWF) is an annual literary festival in Prague, Czech Republic, taking place every spring since 1991. In 2005 the festival was also held in Vienna. Many of the events are broadcast via the internet. International lite ...

* Edward Hirsch"Derek Walcott, The Art of Poetry No. 37"

''The Paris Review'', Winter 1986

Lannan Foundation Reading and Conversation With Glyn Maxwell

November 2002 (audio). * Biography available i

Saint Lucians and the Order of CARICOM

*

Appearance on ''Desert Island Discs''

BBC Radio 4

BBC Radio 4 is a British national radio station owned and operated by the BBC that replaced the BBC Home Service in 1967. It broadcasts a wide variety of spoken-word programmes, including news, drama, comedy, science and history from the BBC's ...

, 9 June 1991

*

{{DEFAULTSORT:Walcott, Derek

1930 births

2017 deaths

Twin people

Boston University faculty

Columbia University faculty

Formalist poets

Harvard University people

MacArthur Fellows

Nobel laureates in Literature

Officers of the Order of the British Empire

Recipients of the Order of Merit (Jamaica)

People from Castries Quarter

People from Greenwich Village

Saint Lucian dramatists and playwrights

Saint Lucian Nobel laureates

20th-century Saint Lucian poets

Trinidad and Tobago dramatists and playwrights

Alumni of University of London Worldwide

Alumni of the University of London

University of the West Indies alumni

20th-century dramatists and playwrights

21st-century dramatists and playwrights

21st-century Saint Lucian poets

Saint Lucian male poets

20th-century male writers

21st-century male writers

PEN Oakland/Josephine Miles Literary Award winners

Epic poets

T. S. Eliot Prize winners

Recipients of the Order of the Caribbean Community