Democratic Party presidential primaries, 1964 on:

[Wikipedia]

[Google]

[Amazon]

From March 10 to June 2, 1964, voters of the Democratic Party chose its nominee for

The goodwill generated by the assassination of Kennedy incident gave Johnson tremendous popularity. He enjoyed strong support against the bitterly divided Republicans; polls in January 1964 showed him leading Republican challengers

The goodwill generated by the assassination of Kennedy incident gave Johnson tremendous popularity. He enjoyed strong support against the bitterly divided Republicans; polls in January 1964 showed him leading Republican challengers

Johnson faced pressure from some within the Democratic Party to name Robert F. Kennedy, the late President Kennedy's younger brother and the U.S. Attorney General, as his vice-presidential choice, which Johnson staffers referred to internally as the "Bobby problem". Kennedy and Johnson had disliked one another since the

Johnson faced pressure from some within the Democratic Party to name Robert F. Kennedy, the late President Kennedy's younger brother and the U.S. Attorney General, as his vice-presidential choice, which Johnson staffers referred to internally as the "Bobby problem". Kennedy and Johnson had disliked one another since the

Wallace had hinted at a possible run numerous times, telling one reporter, "If I ran outside the South and got 10%, it would be a victory. It would shake their eyeteeth in Washington." However, when Milwaukee publicist Lloyd Herbstreith and his wife Dolores attended a Wallace speech at the

Wallace had hinted at a possible run numerous times, telling one reporter, "If I ran outside the South and got 10%, it would be a victory. It would shake their eyeteeth in Washington." However, when Milwaukee publicist Lloyd Herbstreith and his wife Dolores attended a Wallace speech at the

Wallace next appeared on the ballot in

Wallace next appeared on the ballot in

Racially polarized Maryland was Wallace's best showing. There the Johnson supporters struggled to find a suitable candidate after Governor

Racially polarized Maryland was Wallace's best showing. There the Johnson supporters struggled to find a suitable candidate after Governor

With Kennedy out of the way, the question of Johnson's choice of running mate provided some suspense for an otherwise uneventful convention. However, Johnson also became concerned that Kennedy might use a scheduled speech at the 1964 Democratic Convention to create a groundswell of emotion among the delegates to nominate him as Johnson's running mate; Johnson prevented this by scheduling Kennedy's speech on the last day of the convention, by which time the vice-presidential nomination would have been made. Shortly after the convention, Kennedy decided to leave Johnson's cabinet and run for the U.S. Senate in

With Kennedy out of the way, the question of Johnson's choice of running mate provided some suspense for an otherwise uneventful convention. However, Johnson also became concerned that Kennedy might use a scheduled speech at the 1964 Democratic Convention to create a groundswell of emotion among the delegates to nominate him as Johnson's running mate; Johnson prevented this by scheduling Kennedy's speech on the last day of the convention, by which time the vice-presidential nomination would have been made. Shortly after the convention, Kennedy decided to leave Johnson's cabinet and run for the U.S. Senate in

president

President most commonly refers to:

*President (corporate title)

* President (education), a leader of a college or university

* President (government title)

President may also refer to:

Automobiles

* Nissan President, a 1966–2010 Japanese ...

in the 1964 United States presidential election

The 1964 United States presidential election was the 45th quadrennial presidential election. It was held on Tuesday, November 3, 1964. Incumbent Democratic United States President Lyndon B. Johnson defeated Barry Goldwater, the Republican nomi ...

. Incumbent President Lyndon B. Johnson

Lyndon Baines Johnson (; August 27, 1908January 22, 1973), often referred to by his initials LBJ, was an American politician who served as the 36th president of the United States from 1963 to 1969. He had previously served as the 37th vice ...

was selected as the nominee through a series of primary election

Primary elections, or direct primary are a voting process by which voters can indicate their preference for their party's candidate, or a candidate in general, in an upcoming general election, local election, or by-election. Depending on the ...

s and caucus

A caucus is a meeting of supporters or members of a specific political party or movement. The exact definition varies between different countries and political cultures.

The term originated in the United States, where it can refer to a meeting ...

es culminating in the 1964 Democratic National Convention

The 1964 Democratic National Convention of the Democratic Party, took place at Boardwalk Hall in Atlantic City, New Jersey from August 24 to 27, 1964. President Lyndon B. Johnson was nominated for a full term. Senator Hubert H. Humphrey of Minnes ...

held from August 24 to August 27, 1964, in Atlantic City

Atlantic City, often known by its initials A.C., is a coastal resort city in Atlantic County, New Jersey, United States. The city is known for its casinos, boardwalk, and beaches. In 2020, the city had a population of 38,497.

, New Jersey

New Jersey is a state in the Mid-Atlantic and Northeastern regions of the United States. It is bordered on the north and east by the state of New York; on the east, southeast, and south by the Atlantic Ocean; on the west by the Delawa ...

.

Primary race

Johnson becamepresident of the United States

The president of the United States (POTUS) is the head of state and head of government of the United States of America. The president directs the Federal government of the United States#Executive branch, executive branch of the Federal gove ...

upon the assassination of John F. Kennedy

John F. Kennedy, the 35th president of the United States, was assassinated on Friday, November 22, 1963, at 12:30 p.m. CST in Dallas, Texas, while riding in a presidential motorcade through Dealey Plaza. Kennedy was in the vehicle with ...

in 1963, and the goodwill generated by the incident gave him tremendous popularity. In the 1964 presidential primaries for the Democratic Party, Johnson faced no real opposition, yet he insisted until near the time of the Democratic National Convention

The Democratic National Convention (DNC) is a series of presidential nominating conventions held every four years since 1832 by the United States Democratic Party. They have been administered by the Democratic National Committee since the 18 ...

that he remained undecided about seeking a full term. Johnson's supporters in the sixteen primary states and Washington, D.C. thus ran write-in campaigns or had favorite son

Favorite son (or favorite daughter) is a political term.

* At the quadrennial American national political party conventions, a state delegation sometimes nominates a candidate from the state, or less often from the state's region, who is not a ...

candidates run in Johnson's place.

Only two potential candidates threatened Johnson's attempts to unite the party. The first was Governor George Wallace

George Corley Wallace Jr. (August 25, 1919 – September 13, 1998) was an American politician who served as the 45th governor of Alabama for four terms. A member of the Democratic Party, he is best remembered for his staunch segregationist a ...

of Alabama

(We dare defend our rights)

, anthem = " Alabama"

, image_map = Alabama in United States.svg

, seat = Montgomery

, LargestCity = Huntsville

, LargestCounty = Baldwin County

, LargestMetro = Greater Birmingham

, area_total_km2 = 135,7 ...

, who had recently come to prominence with his Stand in the Schoolhouse Door

The Stand in the Schoolhouse Door took place at Foster Auditorium at the University of Alabama on June 11, 1963. George Wallace, the Governor of Alabama, in a symbolic attempt to keep his inaugural promise of " segregation now, segregation tom ...

in defiance of the court-ordered desegregation

Desegregation is the process of ending the separation of two groups, usually referring to races. Desegregation is typically measured by the index of dissimilarity, allowing researchers to determine whether desegregation efforts are having impact o ...

of the University of Alabama

The University of Alabama (informally known as Alabama, UA, or Bama) is a public research university in Tuscaloosa, Alabama. Established in 1820 and opened to students in 1831, the University of Alabama is the oldest and largest of the publ ...

. Wallace appeared on the ballot in Wisconsin

Wisconsin () is a state in the upper Midwestern United States. Wisconsin is the 25th-largest state by total area and the 20th-most populous. It is bordered by Minnesota to the west, Iowa to the southwest, Illinois to the south, Lake M ...

, Indiana

Indiana () is a U.S. state in the Midwestern United States. It is the 38th-largest by area and the 17th-most populous of the 50 States. Its capital and largest city is Indianapolis. Indiana was admitted to the United States as the 19th ...

, and Maryland

Maryland ( ) is a state in the Mid-Atlantic region of the United States. It shares borders with Virginia, West Virginia, and the District of Columbia to its south and west; Pennsylvania to its north; and Delaware and the Atlantic Ocean t ...

; while he lost all three primaries, he surpassed all expectations, and his performance set the stage for his 1968 third-party run. The other potential contender was Attorney General Robert F. Kennedy, who polls showed was a heavy favorite to be Johnson's running mate. Johnson and Kennedy disliked one another intensely, and although Johnson worried he might need Kennedy to defeat a moderate Republican

Republican can refer to:

Political ideology

* An advocate of a republic, a type of government that is not a monarchy or dictatorship, and is usually associated with the rule of law.

** Republicanism, the ideology in support of republics or agains ...

ticket, he ultimately announced that none of his cabinet members would be selected as his running mate.

As the 1964 nomination was considered a foregone conclusion, the primaries received little press attention outside of Wallace's entry into the race. Despite threats of an independent run in the general election

A general election is a political voting election where generally all or most members of a given political body are chosen. These are usually held for a nation, state, or territory's primary legislative body, and are different from by-elections ( ...

, Wallace withdrew his candidacy in the summer of 1964 because of a lack of support. Johnson announced Hubert Humphrey

Hubert Horatio Humphrey Jr. (May 27, 1911 – January 13, 1978) was an American pharmacist and politician who served as the 38th vice president of the United States from 1965 to 1969. He twice served in the United States Senate, representing ...

as his vice-presidential choice at the 1964 Democratic Convention

The 1964 Democratic National Convention of the Democratic Party, took place at Boardwalk Hall in Atlantic City, New Jersey from August 24 to 27, 1964. President Lyndon B. Johnson was nominated for a full term. Senator Hubert H. Humphrey of Minn ...

and went on to win a landslide election against Goldwater in November.

Background

The goodwill generated by the assassination of Kennedy incident gave Johnson tremendous popularity. He enjoyed strong support against the bitterly divided Republicans; polls in January 1964 showed him leading Republican challengers

The goodwill generated by the assassination of Kennedy incident gave Johnson tremendous popularity. He enjoyed strong support against the bitterly divided Republicans; polls in January 1964 showed him leading Republican challengers Barry Goldwater

Barry Morris Goldwater (January 2, 1909 – May 29, 1998) was an American politician and United States Air Force officer who was a five-term U.S. Senator from Arizona (1953–1965, 1969–1987) and the Republican Party nominee for president ...

75% to 20% and Nelson Rockefeller

Nelson Aldrich Rockefeller (July 8, 1908 – January 26, 1979), sometimes referred to by his nickname Rocky, was an American businessman and politician who served as the 41st vice president of the United States from 1974 to 1977. A member of t ...

74% to 17%. However, Wallace had received over 100,000 letters and telegrams of support, nearly half from non-southerners, following his 1963 Stand in the Schoolhouse Door

The Stand in the Schoolhouse Door took place at Foster Auditorium at the University of Alabama on June 11, 1963. George Wallace, the Governor of Alabama, in a symbolic attempt to keep his inaugural promise of " segregation now, segregation tom ...

in defiance of a court order to integrate the University of Alabama, and he subsequently became "Tennyson's Mordred, exposing the dark side of Camelot

Camelot is a castle and court associated with the legendary King Arthur. Absent in the early Arthurian material, Camelot first appeared in 12th-century French romances and, since the Lancelot-Grail cycle, eventually came to be described as th ...

". He began a national speaking tour with a well-received lecture at Harvard

Harvard University is a private Ivy League research university in Cambridge, Massachusetts. Founded in 1636 as Harvard College and named for its first benefactor, the Puritan clergyman John Harvard, it is the oldest institution of higher le ...

on November 7, 1963, bringing him additional notoriety as he flirted with the idea of a national campaign. Wallace's charm and candor won over many of his critics; during a question and answer session at Harvard, a black man asserted his intention to run for president, to which Wallace smiled and responded, "Between you and me both, we might get rid of that crowd in Washington. We might even run on the same ticket." Meanwhile, Johnson forbade discussion of politics in the White House and refused to comment on whether he would run in the 1964 election, instead pursuing the late Kennedy's legislative agenda (most notably the Civil Rights Act of 1964

The Civil Rights Act of 1964 () is a landmark civil rights and labor law in the United States that outlaws discrimination based on race, color, religion, sex, and national origin. It prohibits unequal application of voter registration requi ...

), managing the Vietnam War

The Vietnam War (also known by #Names, other names) was a conflict in Vietnam, Laos, and Cambodia from 1 November 1955 to the fall of Saigon on 30 April 1975. It was the second of the Indochina Wars and was officially fought between North Vie ...

, and declaring his own "War on Poverty

The war on poverty is the unofficial name for legislation first introduced by United States President Lyndon B. Johnson during his State of the Union address on January 8, 1964. This legislation was proposed by Johnson in response to a nationa ...

".

Despite condemnation from media outlets — in 1965, when reporter Theodore H. White published ''The Making of the President, 1964'', he referred to Wallace as a "narrow-minded, grotesquely provincial man" — Wallace's opposition to the Civil Rights Act, which he based upon states' rights

In American political discourse, states' rights are political powers held for the state governments rather than the federal government according to the United States Constitution, reflecting especially the enumerated powers of Congress and the ...

, represented what pundits and analysts began referring to as backlash, specifically ''white'' backlash. Coined in summer 1963 to refer to the possibility that white workers, when forced to compete with their black colleagues in a shrinking job market, might "lash back", backlash came to be associated with whites' ability to do so in the voting booth in the face of racial tension, as they had done with the repeal of the Rumford Fair Housing Act

California Proposition 14 was a November 1964 initiative ballot measure that amended the California state constitution to nullify the 1963 Rumford Fair Housing Act, thereby allowing property sellers, landlords and their agents to openly discrim ...

in California. A series of riots

A riot is a form of civil disorder commonly characterized by a group lashing out in a violent public disturbance against authority, property, or people.

Riots typically involve destruction of property, public or private. The property targeted ...

over civil rights in cities throughout the U.S., notably in Cambridge, Maryland

Cambridge is a city in Dorchester County, Maryland, United States. The population was 13,096 at the 2020 census. It is the county seat of Dorchester County and the county's largest municipality. Cambridge is the fourth most populous city in Mary ...

, and the Black Power movement further heightened the tension on which Wallace was able to capitalize.White, pp. 233-235; Kolkey, pp. 162-209; Rogin, pp.33-41. See also White, chapter eight, "Riots in the Streets: The Politics of Chaos". Wallace's connection with the alienated workingman would later manifest itself in the concept of the so-called "silent majority

The silent majority is an unspecified large group of people in a country or group who do not express their opinions publicly. The term was popularized by U.S. President Richard Nixon in a televised address on November 3, 1969, in which he said, " ...

".

Primaries

At the time, the transition from traditional party conventions to the modernpresidential primary

The presidential primary elections and caucuses held in the various states, the District of Columbia, and territories of the United States form part of the nominating process of candidates for United States presidential elections. The United S ...

was still in progress, and only sixteen states and the District of Columbia

)

, image_skyline =

, image_caption = Clockwise from top left: the Washington Monument and Lincoln Memorial on the National Mall, United States Capitol, Logan Circle (Washington, D.C.), Logan Circle, Jefferson Memoria ...

held primaries for the 1964 election. Despite Johnson's very real doubts about running, his candidacy was never in question to the general public. Indeed, in several states, "unpledged delegates" was the only option on the ballot for the Democratic primary. Amid a Republican Party that struggled to find a candidate and the protests of African Americans over civil rights, the Democratic primaries received relatively scant national attention outside Wallace's entry into the race.

Although Johnson faced no real opposition for the Democratic nomination, a plan had been hatched by a number of southerners to run favorite son

Favorite son (or favorite daughter) is a political term.

* At the quadrennial American national political party conventions, a state delegation sometimes nominates a candidate from the state, or less often from the state's region, who is not a ...

candidates in the general election in an attempt to send the Electoral College vote to the House of Representatives

House of Representatives is the name of legislative bodies in many countries and sub-national entitles. In many countries, the House of Representatives is the lower house of a bicameral legislature, with the corresponding upper house often c ...

under the Twelfth Amendment. One of the two major parties would then be forced to make concessions, particularly on the issue of civil rights. This plan never materialized, but on May 5, 1964, voters in Alabama voted by a five-to-one margin for a slate of unpledged electors controlled by Wallace, which prevented Johnson's name from appearing on the ballot in the general election.Lesher, p. 295. A similar slate of unpledged electors appeared on the ballot alongside Johnson and Barry Goldwater

Barry Morris Goldwater (January 2, 1909 – May 29, 1998) was an American politician and United States Air Force officer who was a five-term U.S. Senator from Arizona (1953–1965, 1969–1987) and the Republican Party nominee for president ...

, the eventual Republican nominee, in Mississippi

Mississippi () is a state in the Southeastern region of the United States, bordered to the north by Tennessee; to the east by Alabama; to the south by the Gulf of Mexico; to the southwest by Louisiana; and to the northwest by Arkansas. Miss ...

; Goldwater won both states in the general election. Wallace's third-party run in 1968 would have a similar premise, aiming not to win but to force one of the two major parties to make concessions, and nearly succeeded in throwing the election.

The "Bobby problem"

Johnson faced pressure from some within the Democratic Party to name Robert F. Kennedy, the late President Kennedy's younger brother and the U.S. Attorney General, as his vice-presidential choice, which Johnson staffers referred to internally as the "Bobby problem". Kennedy and Johnson had disliked one another since the

Johnson faced pressure from some within the Democratic Party to name Robert F. Kennedy, the late President Kennedy's younger brother and the U.S. Attorney General, as his vice-presidential choice, which Johnson staffers referred to internally as the "Bobby problem". Kennedy and Johnson had disliked one another since the 1960 Democratic National Convention

The 1960 Democratic National Convention was held in Los Angeles, California, on July 11–15, 1960. It nominated Senator John F. Kennedy of Massachusetts for president and Senate Majority Leader Lyndon B. Johnson of Texas for vice president. ...

, where Kennedy tried to prevent Johnson from becoming his brother's running mate; moreover, Johnson wished to form his own legacy rather than being perceived as a " lame duck". Although Johnson confided to aides on several occasions that he might be forced to accept Kennedy in order to secure a victory over a moderate Republican ticket such as Governor of New York Nelson Rockefeller

Nelson Aldrich Rockefeller (July 8, 1908 – January 26, 1979), sometimes referred to by his nickname Rocky, was an American businessman and politician who served as the 41st vice president of the United States from 1974 to 1977. A member of t ...

and the popular Ambassador to South Vietnam Henry Cabot Lodge Jr.

Henry Cabot Lodge Jr. (July 5, 1902 – February 27, 1985) was an American diplomat and Republican United States senator from Massachusetts in both Senate seats in non-consecutive terms of service and a United States ambassador. He was considered ...

, Kennedy supporters attempted to force the issue by running a draft movement during the write-in New Hampshire primary

The New Hampshire presidential primary is the first in a series of nationwide party primary elections and the second party contest (the first being the Iowa caucuses) held in the United States every four years as part of the process of choos ...

. This movement gained momentum after Governor John W. King's endorsement and infuriated Johnson. Kennedy received 25,094 votes for vice president in New Hampshire, far surpassing Hubert Humphrey

Hubert Horatio Humphrey Jr. (May 27, 1911 – January 13, 1978) was an American pharmacist and politician who served as the 38th vice president of the United States from 1965 to 1969. He twice served in the United States Senate, representing ...

, the next highest name and eventual nominee.

The potential need for a Johnson–Kennedy ticket was ultimately eliminated by the Republican nomination of conservative Barry Goldwater

Barry Morris Goldwater (January 2, 1909 – May 29, 1998) was an American politician and United States Air Force officer who was a five-term U.S. Senator from Arizona (1953–1965, 1969–1987) and the Republican Party nominee for president ...

. With Goldwater as his opponent, Johnson's choice of vice president was all but irrelevant; opinion polls had revealed that, while Kennedy was an overwhelming first choice among Democrats, any choice made less than a 2% difference in a general election that already promised to be a landslide. When attempts to ease Kennedy out of the running failed, Johnson searched for a way to eliminate him with minimal party discord, and eventually announced that none of his cabinet members would be considered for the position. Kennedy instead mounted a successful run for United States Senate

The United States Senate is the upper chamber of the United States Congress, with the House of Representatives being the lower chamber. Together they compose the national bicameral legislature of the United States.

The composition and po ...

in New York.

Wisconsin

Wallace had hinted at a possible run numerous times, telling one reporter, "If I ran outside the South and got 10%, it would be a victory. It would shake their eyeteeth in Washington." However, when Milwaukee publicist Lloyd Herbstreith and his wife Dolores attended a Wallace speech at the

Wallace had hinted at a possible run numerous times, telling one reporter, "If I ran outside the South and got 10%, it would be a victory. It would shake their eyeteeth in Washington." However, when Milwaukee publicist Lloyd Herbstreith and his wife Dolores attended a Wallace speech at the University of Wisconsin–Madison

A university () is an institution of higher (or tertiary) education and research which awards academic degrees in several academic disciplines. Universities typically offer both undergraduate and postgraduate programs. In the United Stat ...

on February 19, 1964, they were reportedly so moved that they began a drive to place Wallace's name on the ballot in the April 7 primary, a relatively simple procedure requiring a qualified slate of sixty electors to represent the state's congressional districts and at-large votes. When Johnson's surrogate, Governor John W. Reynolds, was asked about the prospect of a Wallace run, he jocularly deferred all questions to Dolores Herbstreith, which gave the Herbstreiths newfound publicity and easily allowed them to beat the March 6 filing deadline. On the day of the deadline, Wallace returned to Wisconsin to announce his candidacy, the Confederate flags and "Stand Up For Alabama" slogan on his airplane replaced with American flags and "Stand Up For America".

Reynolds continued to dismiss Wallace's candidacy, which was denounced by media outlets, clergy, trade unions such as the AFL–CIO

The American Federation of Labor and Congress of Industrial Organizations (AFL–CIO) is the largest federation of unions in the United States. It is made up of 56 national and international unions, together representing more than 12 million ac ...

, and even Wallace's own party. According to J. Louis Hanson, chair of the state Democratic Party, "Given the state election laws in Wisconsin, any kook—and I consider him a kook—can cause trouble. This man is being supported by extreme right-wing elements who are probably kookier than he is." In an attempt to drum up support for his own cause, Reynolds told a group of supporters at one point that it would be a catastrophe if Wallace received 100,000 votes. Wallace went on to receive 266,000 votes, or one-third of the 780,000 Democratic votes cast, and would later observe that "there must have been three catastrophes in Wisconsin."

Wallace's strong showing was due in part to his appeal to ethnic neighborhoods made up of immigrants from countries such as Poland

Poland, officially the Republic of Poland, is a country in Central Europe. It is divided into 16 administrative provinces called voivodeships, covering an area of . Poland has a population of over 38 million and is the fifth-most populou ...

, Czechoslovakia

, rue, Чеськословеньско, , yi, טשעכאסלאוואקיי,

, common_name = Czechoslovakia

, life_span = 1918–19391945–1992

, p1 = Austria-Hungary

, image_p1 ...

, Hungary

Hungary ( hu, Magyarország ) is a landlocked country in Central Europe. Spanning of the Carpathian Basin, it is bordered by Slovakia to the north, Ukraine to the northeast, Romania to the east and southeast, Serbia to the south, Cr ...

and Yugoslavia

Yugoslavia (; sh-Latn-Cyrl, separator=" / ", Jugoslavija, Југославија ; sl, Jugoslavija ; mk, Југославија ;; rup, Iugoslavia; hu, Jugoszlávia; rue, label= Pannonian Rusyn, Югославия, translit=Juhoslavij ...

. Despite initial apprehension about campaigning in these communities, Wallace biographer Stephen Lesher credits him with recognizing that they were "powerfully attracted to the message that the civil rights bill might adversely affect their jobs, their property values, the makeup of their neighborhoods, and children's schools". Others note that Wallace's anti-Communist

Anti-communism is political and ideological opposition to communism. Organized anti-communism developed after the 1917 October Revolution in the Russian Empire, and it reached global dimensions during the Cold War, when the United States and the ...

message resonated with communities whose home countries were behind the Iron Curtain

The Iron Curtain was the political boundary dividing Europe into two separate areas from the end of World War II in 1945 until the end of the Cold War in 1991. The term symbolizes the efforts by the Soviet Union (USSR) to block itself and its ...

of the Soviet Union

The Soviet Union,. officially the Union of Soviet Socialist Republics. (USSR),. was a transcontinental country that spanned much of Eurasia from 1922 to 1991. A flagship communist state, it was nominally a federal union of fifteen nationa ...

, and a series of blunders by the Reynolds campaign added to an existing resentment of Reynolds' tax policies and a recently passed housing law.Carter, pp. 206–208; Savage, p. 216 "What Reynolds and most commentators would miss," Lesher writes, was that Dolores Herbstreith, who had never participated in politics until she became the ''de facto'' Wallace campaign chair in the state, was "neither a racist nor a crazy ... less interested in race and the Communist menace than in sowing conservative seeds that began sprouting with Barry Goldwater later that year and flowered with Ronald Reagan

Ronald Wilson Reagan ( ; February 6, 1911June 5, 2004) was an American politician, actor, and union leader who served as the 40th president of the United States from 1981 to 1989. He also served as the 33rd governor of California from 1967 ...

in the 1980s."

Indiana

Indiana

Indiana () is a U.S. state in the Midwestern United States. It is the 38th-largest by area and the 17th-most populous of the 50 States. Its capital and largest city is Indianapolis. Indiana was admitted to the United States as the 19th ...

, which had a long history of Ku Klux Klan

The Ku Klux Klan (), commonly shortened to the KKK or the Klan, is an American white supremacist, right-wing terrorist, and hate group whose primary targets are African Americans, Jews, Latinos, Asian Americans, Native Americans, and Cat ...

activity, against Governor Matthew E. Welsh

Matthew Empson Welsh (September 15, 1912 – May 28, 1995) was an American politician who was the 41st governor of Indiana and a member of the Democratic Party, serving from 1961 to 1965. His term as governor saw a major increase in statewide t ...

, who was running specifically so that Wallace would not be unopposed.Gugin, p. 342 Welsh considered Wallace a formidable opponent and took no chances, manipulating party machinery and arranging for a photograph of himself shaking hands with President Johnson; meanwhile, the Democratic State Committee began a $75,000 advertising campaign on his behalf.Carter, p. 210; Lesher, p. 293. Welsh stumped

Stumped is a method of dismissing a batsman in cricket, which involves the wicket-keeper putting down the wicket while the batsman is out of his ground. (The batsman leaves his ground when he has moved down the pitch beyond the popping creas ...

across the state touting his civil rights credentials and denigrating Wallace. His slogan was "Clear the way for LBJ, vote Welsh the fifth of May." He also benefited from the fact that Indiana at the time had a unique type of closed primary

Primary elections, or direct primary are a voting process by which voters can indicate their preference for their party's candidate, or a candidate in general, in an upcoming general election, local election, or by-election. Depending on the c ...

which technically allowed Republicans to vote for Wallace but required them to sign an affidavit

An ( ; Medieval Latin for "he has declared under oath") is a written statement voluntarily made by an ''affiant'' or '' deponent'' under an oath or affirmation which is administered by a person who is authorized to do so by law. Such a stateme ...

that they would vote for the Democrat in the general election.

As Wallace excoriated what he called "sweeping federal encroachment" on the gradual process of desegregation, described the Civil Rights Act as a "back-door open-occupancy bill", and appeared alongside a popular Catholic bishop in support of a constitutional amendment to allow school prayer

School prayer, in the context of religious liberty, is state-sanctioned or mandatory prayer by students in public schools. Depending on the country and the type of school, state-sponsored prayer may be required, permitted, or prohibited. Countries ...

, tension continued to mount. Senator Ted Kennedy

Edward Moore Kennedy (February 22, 1932 – August 25, 2009) was an American lawyer and politician who served as a United States senator from Massachusetts for almost 47 years, from 1962 until his death in 2009. A member of the Democratic ...

made a stop in the state to denounce him, and both of Indiana's Democratic senators campaigned against him. At a speaking engagement at the University of Notre Dame

The University of Notre Dame du Lac, known simply as Notre Dame ( ) or ND, is a private Catholic research university in Notre Dame, Indiana, outside the city of South Bend. French priest Edward Sorin founded the school in 1842. The main c ...

, Wallace was interrupted when nearly 500 of the 5,000-member audience began heckling him while protesters outside sang the civil rights anthem "We Shall Overcome

"We Shall Overcome" is a gospel song which became a protest song and a key anthem of the American civil rights movement. The song is most commonly attributed as being lyrically descended from "I'll Overcome Some Day", a hymn by Charles Albert ...

". During the campaign, Welsh took part in a Civil War Centennial Tour wherein he visited the capitals of each of the southern states, except Alabama, and held official ceremonies to return the Confederate battle flags captured by Hoosier

Hoosier is the official demonym for the people of the U.S. state of Indiana. The origin of the term remains a matter of debate, but "Hoosier" was in general use by the 1840s, having been popularized by Richmond resident John Finley's 1833 poem " ...

soldiers during the American Civil War

The American Civil War (April 12, 1861 – May 26, 1865; also known by Names of the American Civil War, other names) was a civil war in the United States. It was fought between the Union (American Civil War), Union ("the North") and t ...

. Wallace refused to hold such a ceremony and Alabama's captured battle flags still remain on display in the Indiana World War Memorial.

Wallace received nearly 30% of the vote, below some expectations but nonetheless startling given the level of opposition. The total was 376,023 to 172,646 votes — Wallace's worst showing in any state.Gugin, p. 343

In an article in ''The British Journal of Sociology'', Michael Rogin observed a heavy correlation between significant African American

African Americans (also referred to as Black Americans and Afro-Americans) are an ethnic group consisting of Americans with partial or total ancestry from sub-Saharan Africa. The term "African American" generally denotes descendants of ens ...

populations and white support for Wallace, similar to patterns that had long been observed in the Southern United States

The Southern United States (sometimes Dixie, also referred to as the Southern States, the American South, the Southland, or simply the South) is a geographic and cultural region of the United States of America. It is between the Atlantic Ocean ...

. He found a belt running through the northern part of the state near Gary (at the time, Indiana's African-American population made up 6% of the state, compared to 45-50% in Gary), where Wallace consistently received overwhelming support across class lines from whites. A notable exception was the Jew

Jews ( he, יְהוּדִים, , ) or Jewish people are an ethnoreligious group and nation originating from the Israelites Israelite origins and kingdom: "The first act in the long drama of Jewish history is the age of the Israelites""T ...

ish vote. He also found a Bible Belt

The Bible Belt is a region of the Southern United States in which socially conservative Protestant Christianity plays a strong role in society and politics, and church attendance across the denominations is generally higher than the nation's a ...

of moderate-sized cities running through central Indiana where, despite a negligible black population, Wallace similarly dominated the Fundamentalist

Fundamentalism is a tendency among certain groups and individuals that is characterized by the application of a strict literal interpretation to scriptures, dogmas, or ideologies, along with a strong belief in the importance of distinguishi ...

Christian white vote.

Maryland

Racially polarized Maryland was Wallace's best showing. There the Johnson supporters struggled to find a suitable candidate after Governor

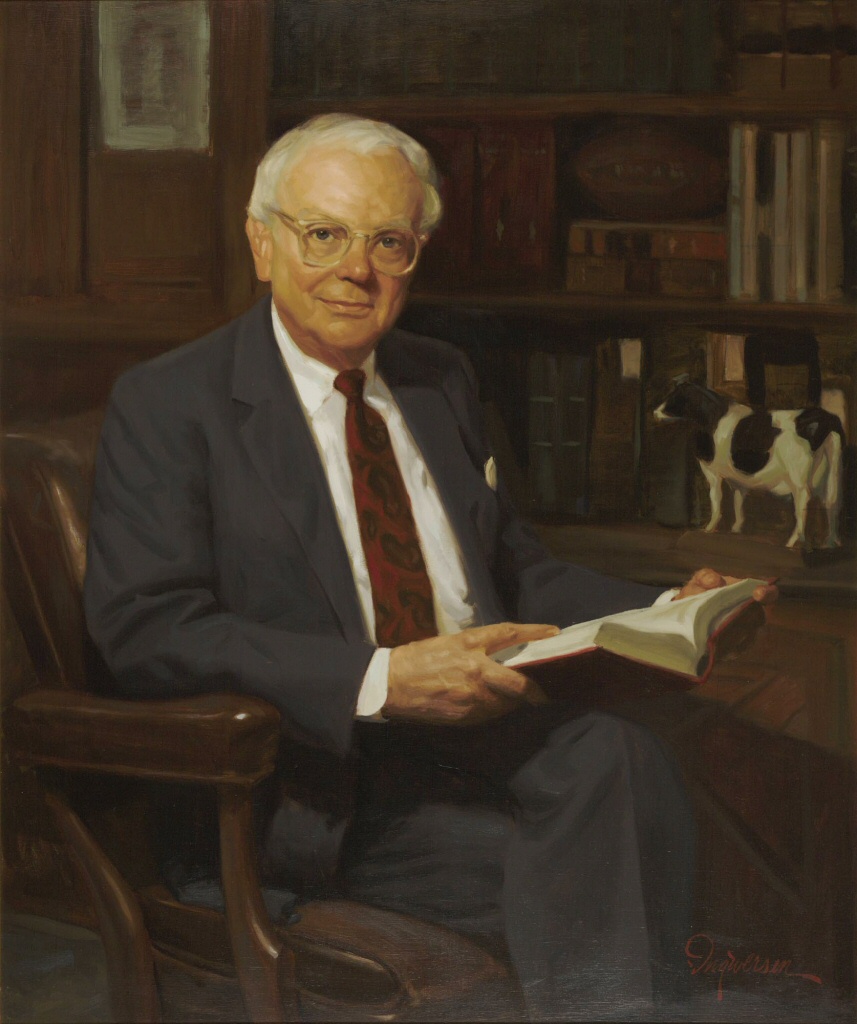

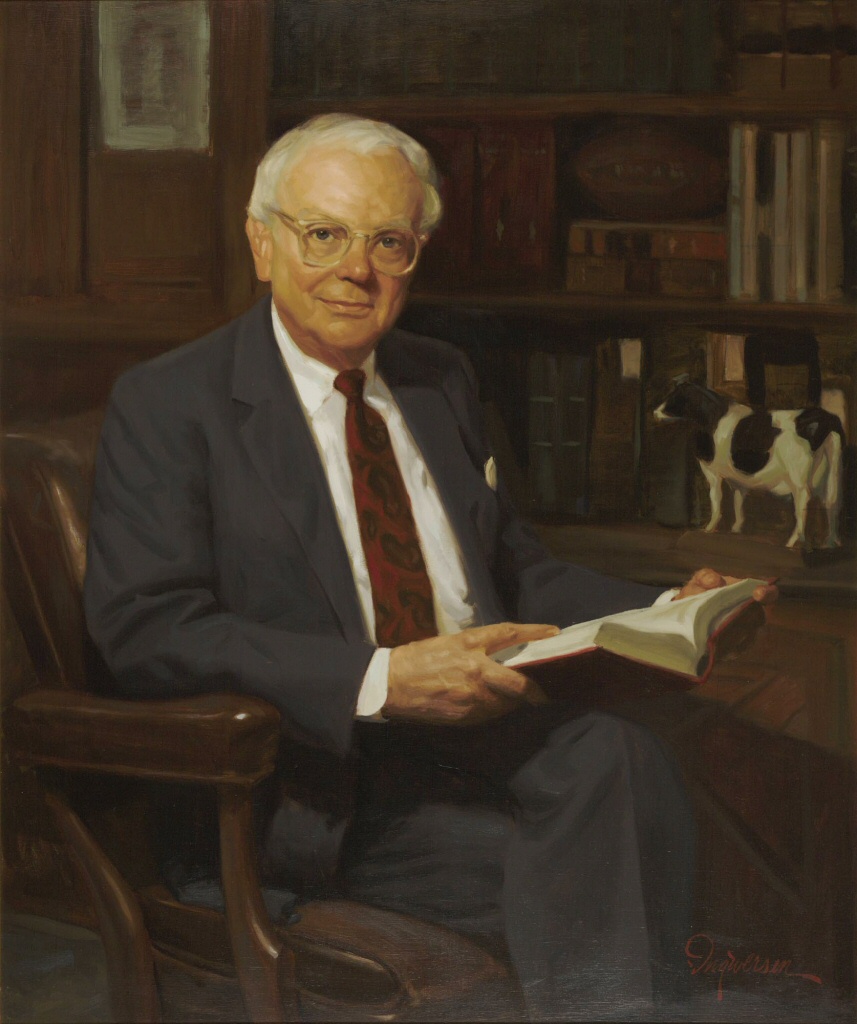

Racially polarized Maryland was Wallace's best showing. There the Johnson supporters struggled to find a suitable candidate after Governor J. Millard Tawes

John Millard Tawes (April 8, 1894June 25, 1979), was an American politician and a member of the Democratic Party who was the 54th Governor of Maryland from 1959 to 1967. He remains the only Marylander to be elected to the three positions of Stat ...

stepped aside for fear that his past support of civil rights and a recent increase in the state income tax

An income tax is a tax imposed on individuals or entities (taxpayers) in respect of the income or profits earned by them (commonly called taxable income). Income tax generally is computed as the product of a tax rate times the taxable income. Ta ...

would compromise his candidacy. Junior Senator Daniel Brewster

Daniel Baugh Brewster Jr. (November 23, 1923 – August 19, 2007) was an American politician serving as a Democratic member of the United States Senate, representing the State of Maryland from 1963 until 1969. He was also a member of the Marylan ...

stepped in at the last minute at Johnson's request. Once again, religious and labor leaders (in the latter case, the AFL-CIO again found itself at odds with many of its membersDurr, p. 123.), the press, and even Milton Eisenhower

Milton Stover Eisenhower (September 15, 1899 – May 2, 1985) was an American academic administrator. He served as president of three major American universities: Kansas State University, Pennsylvania State University, and Johns Hopkins Universit ...

, brother of former President Dwight D. Eisenhower, lined up against Wallace, and a number of popular senators, including Edward M. Kennedy, Birch Bayh

Birch Evans Bayh Jr. (; January 22, 1928 – March 14, 2019) was an American Democratic Party politician who served as U.S. Senator from Indiana from 1963 to 1981. He was first elected to office in 1954, when he won election to the India ...

, Frank Church

Frank Forrester Church III (July 25, 1924 – April 7, 1984) was an American politician and lawyer. A member of the Democratic Party, he served as a United States senator from Idaho from 1957 until his defeat in 1981. As of 2022, he is the longes ...

, Daniel Inouye

Daniel Ken Inouye ( ; September 7, 1924 – December 17, 2012) was an American lawyer and politician who served as a United States senator from Hawaii from 1963 until his death in 2012. Beginning in 1959, he was the first U.S. representative ...

, and Abraham Ribicoff

Abraham Alexander Ribicoff (April 9, 1910 – February 22, 1998) was an American Democratic Party politician from the state of Connecticut. He represented Connecticut in the United States House of Representatives and Senate and was the 80th ...

, and popular former Baltimore Mayor Thomas D'Alesandro, Jr.

Thomas Ludwig John D'Alesandro Jr. (August 1, 1903 – August 23, 1987) was an American politician who served as the 39th mayor of Baltimore from 1947 to 1959. A member of the Democratic Party, he previously represented in the United States Ho ...

who was the father of future Speaker of the House

The speaker of a deliberative assembly, especially a legislative body, is its presiding officer, or the chair. The title was first used in 1377 in England.

Usage

The title was first recorded in 1377 to describe the role of Thomas de Hunger ...

Nancy Pelosi

Nancy Patricia Pelosi (; ; born March 26, 1940) is an American politician who has served as Speaker of the United States House of Representatives since 2019 and previously from 2007 to 2011. She has represented in the United States House of ...

and then-City Council President Thomas D'Alesandro III

Thomas Ludwig John D'Alesandro III (July 24, 1929 – October 20, 2019) was an American attorney and politician who served as the 44th mayor of Baltimore from 1967 to 1971. A member of the Democratic Party, he was the president of the Balti ...

who went onto become Mayor as well in 1967 and campaigned himself in the Italian wards of Baltimore

Baltimore ( , locally: or ) is the most populous city in the U.S. state of Maryland, fourth most populous city in the Mid-Atlantic, and the 30th most populous city in the United States with a population of 585,708 in 2020. Baltimore was ...

on Brewster's behalf.Lesher, pp. 296-301.

Although race played a significant factor in Wallace's support elsewhere, his strength in Maryland came from the galvanized Eastern Shore, where some estimates put his support among whites as high as 90%. Riots in Cambridge

Cambridge ( ) is a university city and the county town in Cambridgeshire, England. It is located on the River Cam approximately north of London. As of the 2021 United Kingdom census, the population of Cambridge was 145,700. Cambridge bec ...

had erupted over the repeal of an equal access law, and as the rioters clashed with the National Guard, civil rights leader Gloria Richardson led peaceful demonstrations against the measure. At the behest of aid Bill Jones, Wallace reluctantly kept a speaking engagement in Cambridge, where he was confronted by some 500 black protesters. When a baby was thought to have died from the tear gas

Tear gas, also known as a lachrymator agent or lachrymator (), sometimes colloquially known as "mace" after the early commercial aerosol, is a chemical weapon that stimulates the nerves of the lacrimal gland in the eye to produce tears. In ...

used by police, it seemed a public relations

Public relations (PR) is the practice of managing and disseminating information from an individual or an organization (such as a business, government agency, or a nonprofit organization) to the public in order to influence their perception. ...

disaster to the Wallace campaign, but the coroner

A coroner is a government or judicial official who is empowered to conduct or order an inquest into the manner or cause of death, and to investigate or confirm the identity of an unknown person who has been found dead within the coroner's jur ...

's report concluded the baby had died of a congenital heart defect. Opponents nonetheless attempted to use the incident and the neo-Nazi National States' Rights Party

The National States' Rights Party was a white supremacist political party that briefly played a minor role in the politics of the United States.

Foundation

Founded in 1958 in Knoxville, Tennessee, by Edward Reed Fields, a 26-year-old chiropractor ...

's description of Wallace as the "last chance for the white voter" against him, but Wallace continued to gain momentum, and ''The Baltimore Sun

''The Baltimore Sun'' is the largest general-circulation daily newspaper based in the U.S. state of Maryland and provides coverage of local and regional news, events, issues, people, and industries.

Founded in 1837, it is currently owned by T ...

'' observed the distinct possibility that he would win the state.

With voter turnout up by 40%, nearly 500,000 votes were cast, of which Brewster received 53% to Wallace's 43%. Wallace, who won outright among white voters, reportedly said, "If it hadn't been for the nigger bloc vote, we'd have won it all."Carter, p. 215; Lesher, pp. 303-304. Indeed, Wallace won 15 of Maryland's 23 counties, and only a combination of double the usual African-American turnout and liberal votes from Montgomery and Prince George's Counties prevented a Wallace victory.

Results

Candidates: * President Johnson - 1,106,999 (17.7%) *George Wallace

George Corley Wallace Jr. (August 25, 1919 – September 13, 1998) was an American politician who served as the 45th governor of Alabama for four terms. A member of the Democratic Party, he is best remembered for his staunch segregationist a ...

- 672,984 (10.8%)

Johnson surrogates:

* Unpledged delegates - 2,705,290 (43.3%)

* John W. Reynolds - 522,405 (8.4%)

* Albert S. Porter - 493,619 (7.9%)

* Matthew E. Welsh

Matthew Empson Welsh (September 15, 1912 – May 28, 1995) was an American politician who was the 41st governor of Indiana and a member of the Democratic Party, serving from 1961 to 1965. His term as governor saw a major increase in statewide t ...

- 376,023 (6.0%)

* Daniel Brewster

Daniel Baugh Brewster Jr. (November 23, 1923 – August 19, 2007) was an American politician serving as a Democratic member of the United States Senate, representing the State of Maryland from 1963 until 1969. He was also a member of the Marylan ...

- 267,106 (4.3%)

Write-ins:

* Robert F. Kennedy - 36,258 (0.5%)

* Henry Cabot Lodge

Henry Cabot Lodge (May 12, 1850 November 9, 1924) was an American Republican politician, historian, and statesman from Massachusetts. He served in the United States Senate from 1893 to 1924 and is best known for his positions on foreign polic ...

- 8,495 (0.1%)

* William W. Scranton

William Warren Scranton (July 19, 1917 – July 28, 2013) was an American Republican Party politician and diplomat. Scranton served as the 38th Governor of Pennsylvania from 1963 to 1967, and as United States Ambassador to the United Nations f ...

- 8,156 (0.1%)

* Edward M. Kennedy - 1,065 (<0.1%)

* Others - 50,224 (0.8%)

In the state of California, two slates of unpledged delegates appeared on the ballot. The slate controlled by Pat Brown

Edmund Gerald "Pat" Brown (April 21, 1905 – February 16, 1996) was an American lawyer and politician who served as the 32nd governor of California from 1959 to 1967. His first elected office was as district attorney for San Francisco, and he w ...

received 1,693,813 votes (68%), while the slate controlled by Sam Yorty

Samuel William Yorty (October 1, 1909 – June 5, 1998) was an American radio host, attorney, and politician from Los Angeles, California. He served as a member of the United States House of Representatives and the California State Assembly, ...

received 798,431 votes (32%). In West Virginia, where Jennings Randolph

Jennings Randolph (March 8, 1902May 8, 1998) was an American politician from West Virginia. A Democrat, he was most notable for his service in the United States House of Representatives from 1933 to 1947 and the United States Senate from 1958 to ...

campaigned on Johnson's behalf, the only option on the ballot was "unpledged delegates at large", which received 131,432 votes (100%). South Dakota and the District of Columbia similarly had unpledged delegates as the only option. Wallace notably received 12,104 votes in Pennsylvania and 3,751 votes in Illinois despite visiting neither state, although Kennedy received a comparable portion of the vote in both states.

Vice-presidential choice and Wallace's withdrawal

With Kennedy out of the way, the question of Johnson's choice of running mate provided some suspense for an otherwise uneventful convention. However, Johnson also became concerned that Kennedy might use a scheduled speech at the 1964 Democratic Convention to create a groundswell of emotion among the delegates to nominate him as Johnson's running mate; Johnson prevented this by scheduling Kennedy's speech on the last day of the convention, by which time the vice-presidential nomination would have been made. Shortly after the convention, Kennedy decided to leave Johnson's cabinet and run for the U.S. Senate in

With Kennedy out of the way, the question of Johnson's choice of running mate provided some suspense for an otherwise uneventful convention. However, Johnson also became concerned that Kennedy might use a scheduled speech at the 1964 Democratic Convention to create a groundswell of emotion among the delegates to nominate him as Johnson's running mate; Johnson prevented this by scheduling Kennedy's speech on the last day of the convention, by which time the vice-presidential nomination would have been made. Shortly after the convention, Kennedy decided to leave Johnson's cabinet and run for the U.S. Senate in New York

New York most commonly refers to:

* New York City, the most populous city in the United States, located in the state of New York

* New York (state), a state in the northeastern United States

New York may also refer to:

Film and television

* '' ...

, where he won the general election in November. Johnson chose Senator Hubert Humphrey

Hubert Horatio Humphrey Jr. (May 27, 1911 – January 13, 1978) was an American pharmacist and politician who served as the 38th vice president of the United States from 1965 to 1969. He twice served in the United States Senate, representing ...

of Minnesota

Minnesota () is a state in the upper midwestern region of the United States. It is the 12th largest U.S. state in area and the 22nd most populous, with over 5.75 million residents. Minnesota is home to western prairies, now given over t ...

, a liberal and civil rights activist, as his running mate.

Meanwhile, the Republicans had nominated the conservative Goldwater, who shared Wallace's opposition to the Civil Rights Act on the basis of states' rights and found considerable support among southerners. This caused a precipitous drop in support for Wallace's threatened general election campaign, and on June 18, Wallace biographer Dan T. Carter notes that Goldwater gave "a brief speech which — in substance if not tone — could have been written by George Wallace." By July 13, Gallup polls showed that Wallace support in a general election match-up had plummeted to below 3% outside the south. Even in the south, he polled third in a three-way race against Johnson and Goldwater. Goldwater reportedly welcomed Wallace's support but firmly refused him a spot as vice-presidential candidate.Carter, pp. 219-224. With a conservative already facing off against Johnson, Wallace stayed his nascent plans for a third-party run until the 1968 election, ending his campaign with an appearance on ''Face the Nation

''Face the Nation'' is a weekly news and morning public affairs program airing Sundays on the CBS radio and television network. Created by Frank Stanton in 1954, ''Face the Nation'' is one of the longest-running news programs in the history ...

'' on July 19; however, he did not endorse Goldwater. In the general election, Goldwater repudiated Wallace and denied courting his vote, which Wallace took as a personal insult.

Convention

Despite his insistence that he remained undecided about running, Johnson had meticulously planned the convention to ensure it went smoothly. Aside from a minor controversy over the Mississippi delegation (seeMississippi Freedom Democratic Party

The Mississippi Freedom Democratic Party (MFDP), also referred to as the Freedom Democratic Party, was an American political party created in 1964 as a branch of the populist Freedom Democratic organization in the state of Mississippi during ...

), the convention went as planned; in keeping with the speech he gave after Kennedy's assassination, Johnson chose "Let Us Continue" as the motto, and the theme song was a take on " Hello Dolly!" sung by Carol Channing

Carol Elaine Channing (January 31, 1921 – January 15, 2019) was an American actress, singer, dancer and comedian who starred in Broadway and film musicals. Her characters usually had a fervent expressiveness and an easily identifiable voice, ...

entitled "Hello, Lyndon!" Governors Pat Brown

Edmund Gerald "Pat" Brown (April 21, 1905 – February 16, 1996) was an American lawyer and politician who served as the 32nd governor of California from 1959 to 1967. His first elected office was as district attorney for San Francisco, and he w ...

of California and John Connally

John Bowden Connally Jr. (February 27, 1917June 15, 1993) was an American politician. He served as the 39th governor of Texas and as the 61st United States secretary of the Treasury. He began his career as a Democrat and later became a Republic ...

of Texas formally nominated Johnson.

Johnson went on to win the general election in a landslide, only losing the Deep South

The Deep South or the Lower South is a cultural and geographic subregion in the Southern United States. The term was first used to describe the states most dependent on plantations and slavery prior to the American Civil War. Following the wa ...

states of Louisiana

Louisiana , group=pronunciation (French: ''La Louisiane'') is a state in the Deep South and South Central regions of the United States. It is the 20th-smallest by area and the 25th most populous of the 50 U.S. states. Louisiana is bord ...

, Alabama

(We dare defend our rights)

, anthem = " Alabama"

, image_map = Alabama in United States.svg

, seat = Montgomery

, LargestCity = Huntsville

, LargestCounty = Baldwin County

, LargestMetro = Greater Birmingham

, area_total_km2 = 135,7 ...

, Mississippi

Mississippi () is a state in the Southeastern region of the United States, bordered to the north by Tennessee; to the east by Alabama; to the south by the Gulf of Mexico; to the southwest by Louisiana; and to the northwest by Arkansas. Miss ...

, Georgia

Georgia most commonly refers to:

* Georgia (country), a country in the Caucasus region of Eurasia

* Georgia (U.S. state), a state in the Southeast United States

Georgia may also refer to:

Places

Historical states and entities

* Related to the ...

, and South Carolina

)''Animis opibusque parati'' ( for, , Latin, Prepared in mind and resources, links=no)

, anthem = " Carolina";" South Carolina On My Mind"

, Former = Province of South Carolina

, seat = Columbia

, LargestCity = Charleston

, LargestMetro = ...

, as well as Goldwater's home state of Arizona

Arizona ( ; nv, Hoozdo Hahoodzo ; ood, Alĭ ṣonak ) is a state in the Southwestern United States. It is the 6th largest and the 14th most populous of the 50 states. Its capital and largest city is Phoenix. Arizona is part of the Fou ...

.Congressional Quarterly, Inc., pp. 179-180.

See also

*1964 Republican Party presidential primaries

From March 10 to June 2, 1964, voters of the Republican Party elected 1,308 delegates to the 1964 Republican National Convention through a series of delegate selection primaries and caucuses, for the purpose of determining the party's nominee fo ...

* Lyndon B. Johnson 1964 presidential campaign

The 1964 presidential campaign of Lyndon B. Johnson was a successful campaign for Johnson and his running mate Hubert Humphrey for their election as president and vice president of the United States. They defeated Republican presidential nominee ...

Notes

References

;Specific ;Bibliography * * * * * * * * * * * *Further reading

* * {{DEFAULTSORT:Democratic Party (United States) Presidential Primaries, 1964