David Orton (deep ecology) on:

[Wikipedia]

[Google]

[Amazon]

David Keith Orton (January 6, 1934 – May 12, 2011) was a Canadian writer, thinker and environmental activist who played a leading role in developing "left biocentrism" within the philosophy of deep ecology. Orton and his collaborators added the word " left" to biocentrism to indicate their anti-industrial, anti-capitalist orientation and their concern for

After the death of the revolutionary communist

After the death of the revolutionary communist

After a couple of years working as a shipwright carpenter on the Montreal waterfront, Orton moved with his family in 1977 to the

After a couple of years working as a shipwright carpenter on the Montreal waterfront, Orton moved with his family in 1977 to the

Green Web

David and Helga Hoffmann-Orton's website. *. {{DEFAULTSORT:Orton, David Canadian ecologists Canadian non-fiction writers 1934 births 2011 deaths Deaths from pancreatic cancer People from Portsmouth Canadian environmentalists Concordia University alumni The New School alumni

social justice

Social justice is justice in terms of the distribution of wealth, Equal opportunity, opportunities, and Social privilege, privileges within a society. In Western Civilization, Western and Culture of Asia, Asian cultures, the concept of social ...

. Their 10-point ''Left Biocentrism Primer'', published in 1998, accepts the idea that the natural world belongs to all living things, but it also calls for the ethical principles of deep ecology to be applied to sensitive political issues such as working for a reduction in the human population, achieving justice for aboriginal peoples

Indigenous peoples are culturally distinct ethnic groups whose members are directly descended from the earliest known inhabitants of a particular geographic region and, to some extent, maintain the language and culture of those original people ...

, struggling for workers' rights and redistributing wealth. Orton, however, frequently asserted that the rights of nature

Rights of nature or Earth rights is a legal and jurisprudential theory that describes inherent rights as associated with ecosystems and species, similar to the concept of fundamental human rights. The rights of nature concept challenges twentie ...

had to come first. "Social justice is only possible in a context of ecological justice," he wrote. "We have to move from a shallow, human-centered ecology to a deeper all-species centered ecology." Elsewhere he added: "There is no justice for people on a dead planet."

In his extensive writings for a variety of magazines, journals, websites and his own "Green Web", Orton warned about what he saw as the disastrous effects of basing a society's economy on mass consumption

Consumerism is a social and economic order that encourages the acquisition of goods and services in ever-increasing amounts. With the Industrial Revolution, but particularly in the 20th century, mass production led to overproduction—the sup ...

, profit and the exploitation of people and other living beings. "An industrial

Industrial may refer to:

Industry

* Industrial archaeology, the study of the history of the industry

* Industrial engineering, engineering dealing with the optimization of complex industrial processes or systems

* Industrial city, a city dominate ...

capitalist

Capitalism is an economic system based on the private ownership of the means of production and their operation for profit. Central characteristics of capitalism include capital accumulation, competitive markets, price system, priva ...

society, that does not recognize ecological limits but only perpetual economic expansion

An economic expansion is an increase in the level of economic activity, and of the goods and services available. It is a period of economic growth as measured by a rise in real GDP. The explanation of fluctuations in aggregate economic activit ...

and has the profit motive as driver, will eventually consume and destroy itself," he wrote in an online commentary. "But we will all be taken down with it." Orton argued that industrialism, not capitalism, was at the root of ecological destruction. "Industrialism can have a capitalist or a socialist face," he said.

Left biocentrism affirms what one writer calls "a 'collective spirituality' based on the ultimate value of the Earth and its life-forms." Orton himself said that left biocentrism views all living things and the Earth itself as sharing a community. "With such a community," he wrote, "there is a sense of Earth spirituality, as in past animistic

Animism (from Latin: ' meaning ' breath, spirit, life') is the belief that objects, places, and creatures all possess a distinct spiritual essence. Potentially, animism perceives all things—animals, plants, rocks, rivers, weather systems, ...

indigenous societies, where it acted as a restraint upon human exploitation of nature." Thinkers who influenced Orton and his left-biocentric colleagues included Arne Næss

Arne Dekke Eide Næss (; 27 January 1912 – 12 January 2009) was a Norwegian philosopher who coined the term "deep ecology", an important intellectual and inspirational figure within the environmental movement of the late twentieth century ...

, Richard Sylvan, Rudolph Bahro, and John Livingston.

David Orton practised the voluntary simplicity

Simple living refers to practices that promote simplicity in one's lifestyle. Common practices of simple living include reducing the number of possessions one owns, depending less on technology and services, and spending less money. Not only is ...

that is a central tenet of left biocentrism. For 27 years, he lived with his wife and frequent co-author Helga Hoffmann-Orton in a small, 100-year-old farmhouse in Pictou County

Pictou County is a county in the province of Nova Scotia, Canada. It was established in 1835, and was formerly a part of Halifax County from 1759 to 1835. It had a population of 43,657 people in 2021, a decline of 0.2 percent from 2016. Furthermo ...

, Nova Scotia

Nova Scotia ( ; ; ) is one of the thirteen provinces and territories of Canada. It is one of the three Maritime provinces and one of the four Atlantic provinces. Nova Scotia is Latin for "New Scotland".

Most of the population are native Eng ...

. They grew much of their own food and watched as their 130-acre property gradually reverted to forest habitat for a variety of plants, animals and birds. Orton died of pancreatic cancer in 2011 at age 77. At his own request, he was given a "deep green" burial in the forest near his home.

Making of an activist

Early life and education

David Orton was born in 1934 in the industrial city ofPortsmouth, England

Portsmouth ( ) is a port and city in the ceremonial county of Hampshire in southern England. The city of Portsmouth has been a unitary authority since 1 April 1997 and is administered by Portsmouth City Council.

Portsmouth is the most dens ...

. He was one of four boys growing up in a working-class family. In an online autobiography he published six weeks before his death, Orton wrote of his early interest in nature. "In Portsmouth, near where I lived, we had the mudflats of Langston Harbour and not too far away was Farlington Marshes, with its many ducks and geese. Opposite our house was Baffin’s Pond – a large pond with willow trees, swans, ducks, geese, carp and eels."

After failing the exams which "streamed" students to academic or technical programs, Orton ended up at a technical school he disliked because it prepared students for industrial work. Its only redeeming feature for him was its field club which undertook expeditions into the English countryside.

In 1949 at age 15, Orton began a five-year apprenticeship

Apprenticeship is a system for training a new generation of practitioners of a trade or profession with on-the-job training and often some accompanying study (classroom work and reading). Apprenticeships can also enable practitioners to gain a ...

as a shipwright at the Portsmouth Dockyard

His Majesty's Naval Base, Portsmouth (HMNB Portsmouth) is one of three operating bases in the United Kingdom for the Royal Navy (the others being HMNB Clyde and HMNB Devonport). Portsmouth Naval Base is part of the city of Portsmouth; it is l ...

. His training included building 14-foot sailing dinghies, working on a variety of naval vessels and a stint in the drawing office. Although he graduated 10th out of 44 shipwright apprentices and worked for an additional year in the dockyard, Orton writes that he never felt competent in the trade. In the meantime, he studied evenings at the Portsmouth College of Technology, searching, in his words, for a "'way out' of the industrial life."

To his apparent surprise, Orton passed " Ordinary Level English" in 1954--"most unusual for someone with my educational background at that time." He attributes this unexpected success to his reading of authors such as D. H. Lawrence

David Herbert Lawrence (11 September 1885 – 2 March 1930) was an English writer, novelist, poet and essayist. His works reflect on modernity, industrialization, sexuality, emotional health, vitality, spontaneity and instinct. His best-k ...

and his interest in poetry. The qualifications he had earned at the Portsmouth College of Technology gained him admission to the then, Newcastle upon Tyne

Newcastle upon Tyne ( RP: , ), or simply Newcastle, is a city and metropolitan borough in Tyne and Wear, England. The city is located on the River Tyne's northern bank and forms the largest part of the Tyneside built-up area. Newcastle is ...

campus of Durham University in 1955–56 where he studied for a Bachelor of Science

A Bachelor of Science (BS, BSc, SB, or ScB; from the Latin ') is a bachelor's degree awarded for programs that generally last three to five years.

The first university to admit a student to the degree of Bachelor of Science was the University o ...

degree in naval architecture

Naval architecture, or naval engineering, is an engineering discipline incorporating elements of mechanical, electrical, electronic, software and safety engineering as applied to the engineering design process, shipbuilding, maintenance, and ...

. However, he found scientific study uninteresting and failed in all subjects in the examinations of June 1956. He did manage to pass chemistry on a second try in September, but once again, failed mathematics and physics

Physics is the natural science that studies matter, its fundamental constituents, its motion and behavior through space and time, and the related entities of energy and force. "Physical science is that department of knowledge which r ...

. His studies at Durham were over.

Military service

During the 1950s, young men who were medically fit were required to serve for two years in the British military. However, those who qualified could earn extra pay and choose their assignments if they signed up for an extra year. Orton writes that he "stupidly" signed on for a three-year stint with theRoyal Army Educational Corps

The Royal Army Educational Corps (RAEC) was a corps of the British Army tasked with educating and instructing personnel in a diverse range of skills. On 6 April 1992 it became the Educational and Training Services Branch (ETS) of the Adjutant Gen ...

. The army considered him qualified to instruct other conscripts based on his education. But after 269 days, the army decided he did not have the skills to succeed as an instructor. Orton writes that he failed because he lacked the necessary education, but also disliked army discipline and the way military lessons were conducted. The commanding officer's letter of reference, however, paints a picture of a serious and responsible young man:

He is intelligent and has a sound academic background. Although quiet and reserved he has sound principles and convictions. His appearance is neat and his manner good. He can be trusted to apply himself well at all times.Orton was told after his release from the educational corps, he would be recalled to complete his two years of military service. "As I did not want this, I knew it meant leaving the country," he writes.

Emigration to Canada

At age 23, David Orton sailed for Canada arriving inMontreal

Montreal ( ; officially Montréal, ) is the second-most populous city in Canada and most populous city in the Canadian province of Quebec. Founded in 1642 as '' Ville-Marie'', or "City of Mary", it is named after Mount Royal, the triple ...

in November 1957. His skills as a shipwright qualified him for permanent residency in Canada as a landed immigrant

Permanent residency (PR) in Canada is a status granting someone who is not a Canadian citizen the right to live and work in Canada without any time limit on their stay. To become a permanent resident a foreign national must apply to Immigration ...

. (He became a Canadian citizen on January 7, 1963.) Orton worked as a railway clerk and brewery tank cleaner until he enrolled, in 1959, as a Bachelor of Arts

Bachelor of arts (BA or AB; from the Latin ', ', or ') is a bachelor's degree awarded for an undergraduate program in the arts, or, in some cases, other disciplines. A Bachelor of Arts degree course is generally completed in three or four year ...

student at Montreal's Sir George Williams University

Sir George Williams University was a university in Montreal, Quebec, Canada. It merged with Loyola College to create Concordia University on August 24, 1974.

History

In 1851, the first YMCA in North America was established on Sainte-Hélène ...

, now known as Concordia. In the meantime, he met and began living with Gunilla Larsson, a woman who worked at the Swedish consulate in Montreal.

Orton received his B.A. degree in 1963 along with a congratulatory letter from the university's vice-principal. It said that although Orton had not won the medal awarded to the highest-ranking B.A. student, "you came very close to it, and your achievement is so fine that I felt that I ought to write to you and congratulate you upon the fine work that you have done here as a student, and to tell you how proud we are of you."

Graduate studies

In the fall of 1963, Orton, age 29, moved toNew York City

New York, often called New York City or NYC, is the most populous city in the United States. With a 2020 population of 8,804,190 distributed over , New York City is also the most densely populated major city in the Un ...

to attend the New School for Social Research, now known as The New School

The New School is a private research university in New York City. It was founded in 1919 as The New School for Social Research with an original mission dedicated to academic freedom and intellectual inquiry and a home for progressive thinkers. ...

. He studied in the Graduate Faculty of Political and Social Science earning his Master of Arts

A Master of Arts ( la, Magister Artium or ''Artium Magister''; abbreviated MA, M.A., AM, or A.M.) is the holder of a master's degree awarded by universities in many countries. The degree is usually contrasted with that of Master of Science. Th ...

degree in 1965 and winning a prize as "outstanding student in sociology

Sociology is a social science that focuses on society, human social behavior, patterns of social relationships, social interaction, and aspects of culture associated with everyday life. It uses various methods of empirical investigation an ...

". He then passed the qualifying examination for Ph.D

A Doctor of Philosophy (PhD, Ph.D., or DPhil; Latin: or ') is the most common degree at the highest academic level awarded following a course of study. PhDs are awarded for programs across the whole breadth of academic fields. Because it is ...

studies and, in 1966, passed the Ph.D oral exam, but did not submit the required thesis. In the meantime, he taught at the then, New York City Community College

The New York City College of Technology (City Tech) is a public college in New York City. Founded in 1946, it is the City University of New York's college of technology.

History

City Tech was founded in 1946 as The New York State Institute of ...

and served as a teaching assistant to sociology professor, Carl Mayer.For information on Carl Mayer see:

Gunilla Larsson joined Orton in New York and they were eventually married. Their son Karl (named after Karl Marx) was born in New York. A daughter, named Johanna, was born later in Montreal.

Politics and teaching

During his studies in New York, David Orton became engaged in the political struggles that would continue for the rest of his life. He writes that he was influenced by the movement against theVietnam War

The Vietnam War (also known by other names) was a conflict in Vietnam, Laos, and Cambodia from 1 November 1955 to the fall of Saigon on 30 April 1975. It was the second of the Indochina Wars and was officially fought between North Vietnam a ...

and left-wing politics in general. Off campus, he worked in the offices of ''Science & Society

''Science & Society: A Journal of Marxist Thought and Analysis'' is a peer-reviewed academic journal of Marxist scholarship. It covers economics, philosophy of science, historiography, women's studies, literature, the arts, and other social sci ...

'', which describes itself as "the longest continuously published journal of Marxist scholarship, in any language, in the world." On campus, Orton joined other students in demanding that their professors give them more of a say in the content of the courses they were being taught. "It was an uphill battle," Orton writes.

After graduate school, Orton returned to Montreal where he taught as a lecturer in sociology at Sir George Williams from 1967 to 1969. At first, the university seemed eager to hire a "local boy" who had done well academically. But Orton's brand of socialism and his immersion in the hippie culture of New York's Greenwich Village

Greenwich Village ( , , ) is a neighborhood on the west side of Lower Manhattan in New York City, bounded by 14th Street to the north, Broadway to the east, Houston Street to the south, and the Hudson River to the west. Greenwich Village ...

did not endear him to his colleagues in the sociology department. "I had a beard," he writes "and hippy beads around my neck, with the casual clothes to match."

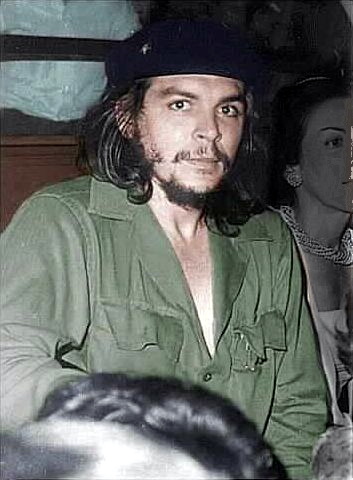

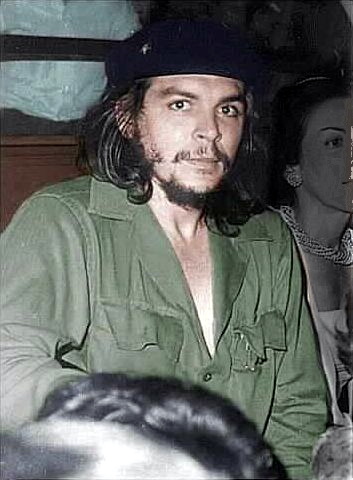

Differences in outlook soon led to a series of clashes. Orton advocated blending socialist theory and practice, but those he termed "academic Marxists," wanted him to stop trying to organize and learn German so that he could read Marx in his original language. Orton's proposed reading lists for his classes and his tentative ideas for allowing students to influence course content led to a full meeting of the department where he was rebuked for not sharing "the consensus of the discipline of sociology." His involvement with the "Movement for Socialist Liberation" displeased university officials especially when the group actively opposed the on-campus recruitment of students by war-related industries. After the death of the revolutionary communist

After the death of the revolutionary communist Che Guevara

Ernesto Che Guevara (; 14 June 1928The date of birth recorded on /upload.wikimedia.org/wikipedia/commons/7/78/Ernesto_Guevara_Acta_de_Nacimiento.jpg his birth certificatewas 14 June 1928, although one tertiary source, (Julia Constenla, quot ...

in 1967, Orton wrote an article for the student newspaper that he says, landed him in considerable trouble:

Che Guevara was no coffee-house revolutionary. He could not be classified as an academic Marxist. Many of these gentlemen—who may be spotted on university campuses in America and Canada, well salaried, well fed and well clothed—make absolute distinctions between revolutionary theory and revolutionary action...Che had an interest in revolutionary theory but he also believed inIn 1969, the university did not renew his teaching contract partly because Orton had not completed his PhD thesis, but also, he writes, because of general hostility toward him from other faculty members. For example, English professor David Sheps wrote an article for the magazine Canadian Dimension that attacked Orton's scholarly credentials:praxis Praxis may refer to: Philosophy and religion * Praxis (process), the process by which a theory, lesson, or skill is enacted, practised, embodied, or realised * Praxis model, a way of doing theology * Praxis (Byzantine Rite), the practice of fai .... His message was brutally simple, yet profound: The revolution will be made by those who act, not by those who endlessly talk and contribute to left-wing journals, regarding strategy, tactics, objective versus subjective conditions, etc, etc.

He is a self-proclaimed Marxist Leninist who, as far as anyone can tell, has read practically noOrton writes that the article "helped to create the material conditions such that I would never again obtain a full-time teaching position in Canada."Marx Karl Heinrich Marx (; 5 May 1818 – 14 March 1883) was a German philosopher, economist, historian, sociologist, political theorist, journalist, critic of political economy, and socialist revolutionary. His best-known titles are the 1848 ...orLenin Vladimir Ilyich Ulyanov. ( 1870 – 21 January 1924), better known as Vladimir Lenin,. was a Russian revolutionary, politician, and political theorist. He served as the first and founding head of government of Soviet Russia from 1917 to 1 .... Since he also refuses on principle to read 'bourgeois sociology' (which he seems to interpret broadly enough to include most left-wing sociologists), many have wondered if he has read anything at all. The Sociology department had chosen not to renew his contract, a decision every left-wing faculty member regarded as eminently sensible.

Communist organizing

Sometime during his academic career at Sir George Williams, David Orton became active in the ''Internationalists'', originally aMaoist

Maoism, officially called Mao Zedong Thought by the Chinese Communist Party, is a variety of Marxism–Leninism that Mao Zedong developed to realise a socialist revolution in the agricultural, pre-industrial society of the Republic of Ch ...

student group that declared itself a political party in 1970 under the banner of the Communist Party of Canada (Marxist-Leninist). Both Orton and his wife Gunilla served on the party's central committee and Orton himself became vice-chairman. He ran as a Marxist-Leninist political candidate in Montreal in two federal elections.

Orton's party organizing work in Montreal, Regina and Toronto led to clashes with the law. After he helped organize a protest against a visiting American military band in Regina, Orton was arrested, but charges against him were eventually dropped. In 1972, however, he chose to spend 40 days in a Toronto jail rather than pay a $400 fine after participating in a demonstration against a meeting of a white supremacist

White supremacy or white supremacism is the belief that white people are superior to those of other races and thus should dominate them. The belief favors the maintenance and defense of any power and privilege held by white people. White s ...

group called the Western Guard

''The Western Guard'' is a newspaper serving Madison and Lac qui Parle County in western Minnesota

Minnesota () is a state in the upper midwestern region of the United States. It is the 12th largest U.S. state in area and the 22nd m ...

.

Although he didn't know it at the time, the Royal Canadian Mounted Police

The Royal Canadian Mounted Police (RCMP; french: Gendarmerie royale du Canada; french: GRC, label=none), commonly known in English as the Mounties (and colloquially in French as ) is the federal police, federal and national police service of ...

sought evidence so they could charge Orton with sedition over incidents that occurred in November 1969 during a seminar at the Regina campus of the University of Saskatchewan

A university () is an institution of higher (or tertiary) education and research which awards academic degrees in several academic disciplines. Universities typically offer both undergraduate and postgraduate programs. In the United States, ...

. The 1978 book, ''An Unauthorized History of the RCMP'' by Lorne and Caroline Brown, reports that during a panel discussion on "Revolt ''vs.'' the Status Quo", Orton stated the Marxist-Leninist position that armed revolution was the only way to change the political system. The book adds that during a later session, Orton denounced Harry Magdoff

Harry Samuel Magdoff (August 21, 1913 – January 1, 2006) was a prominent American socialist commentator. He held several administrative positions in government during the presidency of Franklin D. Roosevelt and later became co-editor of the M ...

, a visiting American Marxist as a liberal reformist and attempted unsuccessfully to take over the microphone. Fifteen months later after the invocation of Canada's ''War Measures Act

The ''War Measures Act'' (french: Loi sur les mesures de guerre; 5 George V, Chap. 2) was a statute of the Parliament of Canada that provided for the declaration of war, invasion, or insurrection, and the types of emergency measures that could t ...

'', the Mounties tried to gather evidence against Orton, but the university authorities refused to release a tape recording of the panel discussion or co-operate in any other way.

Orton and Gunilla resigned from the Marxist-Leninists in 1975 because they felt the party organization was undemocratic.

Refocus on environment

After a couple of years working as a shipwright carpenter on the Montreal waterfront, Orton moved with his family in 1977 to the

After a couple of years working as a shipwright carpenter on the Montreal waterfront, Orton moved with his family in 1977 to the Queen Charlotte Islands

Haida Gwaii (; hai, X̱aaydag̱a Gwaay.yaay / , literally "Islands of the Haida people") is an archipelago located between off the northern Pacific coast of Canada. The islands are separated from the mainland to the east by the shallow Heca ...

or Haida Gwaii, "Islands of the People," off the northern coast of British Columbia

British Columbia (commonly abbreviated as BC) is the westernmost province of Canada, situated between the Pacific Ocean and the Rocky Mountains. It has a diverse geography, with rugged landscapes that include rocky coastlines, sandy beaches, ...

. The move proved to be a turning point in the evolution of Orton's ideas. A job with a fish-packing outfit brought him into contact with the fishing community. He also became interested in the Haida people's environmental ideas as they pursued their land claims. "I decided to refocus my organizing work on environmental issues and not social justice politics," Orton writes in his autobiography.

Orton made contact with the B.C. Federation of Naturalists and eventually wrote a 30-page report for them on a controversial issue—a proposal that would eventually lead to protected, national park reserve status for part of South Moresby Island. The report, entitled "The Case against the Southern Moresby Wilderness Proposal," pointed to a number of contradictions in the naturalists' position. In a book outline written in 2005, Orton suggests that during his time in B.C. he started to understand the inherent conservatism of naturalists' organizations and "the limiting assumptions of mainstream environmentalism." He also realized that the logging industry promoted the management of forests primarily for the production of timber and he saw the fallacies of "multiple use" or "integrated resource management." Orton felt these approaches devalued wilderness as a set of resources to be exploited for the benefit of human beings. He later called it "resourcism" or "the world view that the non-human world exists as raw material for the human purpose."

Orton writes that he and Gunilla Larsson decided to separate shortly after arriving in the Queen Charlotte Islands. "It was a difficult, although friendly, parting," he adds. "(She eventually took our children, Karl and Johanna, back to Sweden.)" Orton decided to move in with Helga Hoffmann, a woman he knew from his days as a Marxist-Leninist. Hoffmann, whom he would later marry, lived in Victoria, B.C.

Helga brought a two-person kayak up to the Charlottes and we took it into the Southern Moresby Wilderness Proposal area. We mainly lived off edible plants and the fish we caught from the kayak. It was a pretty unplanned trip, with no life jackets or signalling gear, just a compass and a map. This forced us to confront and adjust to some extreme weather, plus the natural rhythms of the oceans. I believe this trip was important in developing my environmental consciousness.In the fall of 1977, Orton moved to Victoria to live with Helga. While there, he joined the local naturalists club and worked on a number of environmental issues including the defence of the Tsitika Watershed on northern

Vancouver Island

Vancouver Island is an island in the northeastern Pacific Ocean and part of the Canadian province of British Columbia. The island is in length, in width at its widest point, and in total area, while are of land. The island is the largest by ...

. Orton went to meetings where he clashed with loggers and logging company representatives in his attempts to defend the watershed's ecological integrity. He also wrote a long article about the issue for the B.C. Federation of Naturalists newsletter. "I had come to really oppose the land tenure system, exploited by the logging companies in British Columbia, who used their forest land 'crown leases' to demand millions of dollars in compensation when a park or protected area was proposed," he writes. Orton also sent letters to local newspapers on wildlife and forestry issues and he became a regional vice-president of the Federation. "I found the naturalists generally quite conservative on environmental issues," he writes. "They liked observing nature, but did not want to fight in its defence."

Path to left biocentrism

In September 1979, Orton, then 45, moved with Helga Hoffmann-Orton toNova Scotia

Nova Scotia ( ; ; ) is one of the thirteen provinces and territories of Canada. It is one of the three Maritime provinces and one of the four Atlantic provinces. Nova Scotia is Latin for "New Scotland".

Most of the population are native Eng ...

. By the mid-1980s, they were living with their one-year-old daughter, Karen, on a 130-acre farm in Pictou County. By then, Orton had also become acquainted with the philosophy of deep ecology and had begun formulating ideas that would eventually lead him to "left biocentrism" which he defines as "an evolving theoretical tendency within the deep ecology movement." In 1988, he established his website, the Green Web. "By researching and publishing bulletins through the Green Web," he notes, "I eventually began writing from a left biocentric perspective." He took part in an Internet discussion group called "left bio." The group adopted the deep ecology recognition of the inherent value of all living things but supplemented it with a left biocentric concern for social justice.

Orton also contributed to Canadian Dimension, a left-wing, anti-corporate magazine. Some of his articles explored what Orton himself acknowledged was an extremely sensitive topic—relations between environmental groups and aboriginal peoples. While he contended that environmentalists needed to form alliances with aboriginal peoples, he also warned against what he saw as an uncritical endorsement of aboriginal positions that violated biocentric or Earth-first principles. He pointed, for example, to aboriginal support for the fur industry and commercial trapping as well as for the killing of wolves in the Yukon

Yukon (; ; formerly called Yukon Territory and also referred to as the Yukon) is the smallest and westernmost of Canada's three territories. It also is the second-least populated province or territory in Canada, with a population of 43,964 as ...

to save a caribou herd. Orton criticized the portrayal of native peoples as having lived in complete harmony with nature before the coming of Europeans. He argued that aboriginal groups had hunted several large animals to extinction including mammoth

A mammoth is any species of the extinct elephantid genus ''Mammuthus'', one of the many genera that make up the order of trunked mammals called proboscideans. The various species of mammoth were commonly equipped with long, curved tusks an ...

s, mastodon

A mastodon ( 'breast' + 'tooth') is any proboscidean belonging to the extinct genus ''Mammut'' (family Mammutidae). Mastodons inhabited North and Central America during the late Miocene or late Pliocene up to their extinction at the end of th ...

s and giant bison

''Bison latifrons'', also known as the giant bison or long-horned bison, is an extinct species of bison that lived in North America during the Pleistocene epoch ranging from Alaska to Mexico. It was the largest and heaviest bovid ever to live ...

. "In Canada, a class-based industrial capitalist society imprints its value system upon Native communities as well as upon the non-Native environmental movement," he wrote. "It is not helpful to present a romanticized view of the past as the contemporary Indigenous reality."

During his years in Nova Scotia, Orton took part in many environmental campaigns against what he saw as destructive practices. He vigorously opposed forest clearcutting and spraying; the slaughter of seals; the widespread use of all-terrain vehicles; uranium mining and the installation of industrial wind turbines.

Deep ecology

Judging by his writings, Orton seems to have been attracted to deep ecology partly because of its anti-industrial, anti-capitalist orientation and its belief that industrialism is to blame for theecological crisis

An ecological or environmental crises occurs when changes to the environment of a species or population destabilizes its continued survival. Some of the important causes include:

* Degradation of an abiotic ecological factor (for example, incr ...

threatening the Earth. For Orton, the realization that major environmental problems cannot be resolved within an industrial system, distinguishes deep ecology from "shallow ecology."

The soul of deep ecology is the belief that there has to be a fundamental change in consciousness for humans, in how they relate to the natural world. This requires a change from a human-centered to an ecocentric perspective, meaning humans as a species have no superior status in Nature. All other species have a right to exist, irrespective of their usefulness to the human species or human societies. Humans cannot presume dominance over all non-human species, and see Nature as a "resource" for human and corporate utilization.Orton's experiences waging environmental campaigns in Nova Scotia may also have led him to adopt the central principles of deep ecology. The province's economy is heavily dependent on the extraction of

natural resource

Natural resources are resources that are drawn from nature and used with few modifications. This includes the sources of valued characteristics such as commercial and industrial use, aesthetic value, scientific interest and cultural value. ...

s, and it relies heavily on industrial forestry.

In his article, ''My Path to Left Biocentrism: Part II-Actual Issues'', Orton writes about living 30 kilometres from a big pulp mill and smelling its hydrogen sulphide emissions when the wind blew in his direction. He could also hear the noises from big forestry machines clearcutting huge areas, many of which were sprayed with biocides:

These clearcuts have also meant extensive wildlife habitat destruction, blowdowns in adjacent woodlots, increased human recreational access, and a significant lowering of water levels in the river, the West River, which runs through the valley. Very large areas around here have absolutely no forest canopy remaining. This environmental vandalism, a direct consequence of the softwood, pulp mill forestry orientation in Nova Scotia, has intensified throughout the province. This is the on-ground reality, no matter the increasing use of "eco-rhetoric" by the companies and their government regulatory partners, e.g. proposed "model forests" or "integrated resource management" of crown lands; no matter the increasing awareness of deep ecology by some environmentalists; or the forestry critiques which have come from a number of people, including myself.Orton writes that it is these concrete examples of forest and wildlife destruction that form the basis for "mobilizing activists to fight pulp mill forestry and to fight biological and chemical herbicide spraying programs." He adds that the term "pulp mill forestry" encompasses pulp mills themselves as well as industrial practices such as forest spraying and clearcutting. "The issues are interdependent and need to be fought together."

Left biocentrism

David Orton argued that mainstream deep ecology seems to believe in what he called the "educational fallacy," namely, that ideas are enough to effect fundamental change in the human relationship to the natural world. For him, this approach fails to come to terms with the issues of class and power in industrial, capitalist society. He notes that, at first, he used the term "socialist biocentrism" to signal the importance of fighting for social justice as part of the struggle against the destruction of Nature. However, he abandoned the label partly because he felt it excluded non-socialists and partly because it glossed over what he saw as the anti-ecological characteristics ofsocialism

Socialism is a left-wing Economic ideology, economic philosophy and Political movement, movement encompassing a range of economic systems characterized by the dominance of social ownership of the means of production as opposed to Private prop ...

itself. For Orton, other positions, such as Eco-Feminism and Eco-Marxism, put human concerns ahead of the needs of the natural world. "Ecology must be primary," he wrote, and if it is, one can be involved in peace/anti-war and social justice issues. Left biocentrism says that you must be involved in social justice issues as an environmental activist, but ecology is primary."

In 1998, after lengthy discussion among "left bio" adherents, Orton compiled the ''Left Biocentrism Primer'', a 10-point guide outlining the basic tenets of their "left focus" within the deep ecology movement. Among other things, the primer says "left biocentrism believes that deep ecology must be applied to actual environmental issues and struggles, no matter how socially sensitive." It mentions the need for reducing the human population and considering "aboriginal issues" and "workers' struggles" in the context of a philosophy that puts the needs of the natural world ahead of human-centred concerns.

Although Orton saw the eight-point deep ecology platform as the basis for unity, he criticized the movement's ambiguity when it came to taking positions against economic development. He noted, for example, that Arne Næss

Arne Dekke Eide Næss (; 27 January 1912 – 12 January 2009) was a Norwegian philosopher who coined the term "deep ecology", an important intellectual and inspirational figure within the environmental movement of the late twentieth century ...

, one of the movement's founders, had promoted the concept of sustainable development while arguing against the economic philosophy of zero growth.

Orton criticized mainstream environmental organizations such as the Canadian Environmental Network The Canadian Environmental Network (RCEN) is an umbrella organization for environmental non-governmental organizations (ENGOs) located across Canada. This non-profit organization was mainly funded by Environment Canada and helped to facilitate ne ...

for accepting government money and working with industrial interests. He saw the network as inhibiting "the emergence of a grass-roots controlled and funded, more radical environmental movement in Canada." He also criticized green parties for adopting "shallow" ecological positions in their pursuit of electoral success.

In calling for a radical reduction in the impact of industrialism on the natural world, Orton wrote that life can only be protected by mobilizing the species that is destroying it. "Paying attention to social justice and questions of class, corporate power, and entrenched self-interest, is a necessary part of that human mobilization, and the movement to a deep ecology world," he wrote. "The new social order, which will respect the rights of all species and their specific habitats, will be based on spirituality and morality, not the economy."

Immigration reduction

Orton repudiates the left-wing accusations of the population issue, saying, “Deep ecology supporters, contrary to some social ecology slanders, seek population reduction, or perhaps controls on immigration from a maintenance of biodiversity perspective, and this has nothing to do with fascists.References

;Other sources * Curry, Patrick. (2006) ''Ecological Ethics: An Introduction''. Cambridge: Polity Press.External links

Green Web

David and Helga Hoffmann-Orton's website. *. {{DEFAULTSORT:Orton, David Canadian ecologists Canadian non-fiction writers 1934 births 2011 deaths Deaths from pancreatic cancer People from Portsmouth Canadian environmentalists Concordia University alumni The New School alumni