Dailamites on:

[Wikipedia]

[Google]

[Amazon]

The Daylamites or Dailamites (

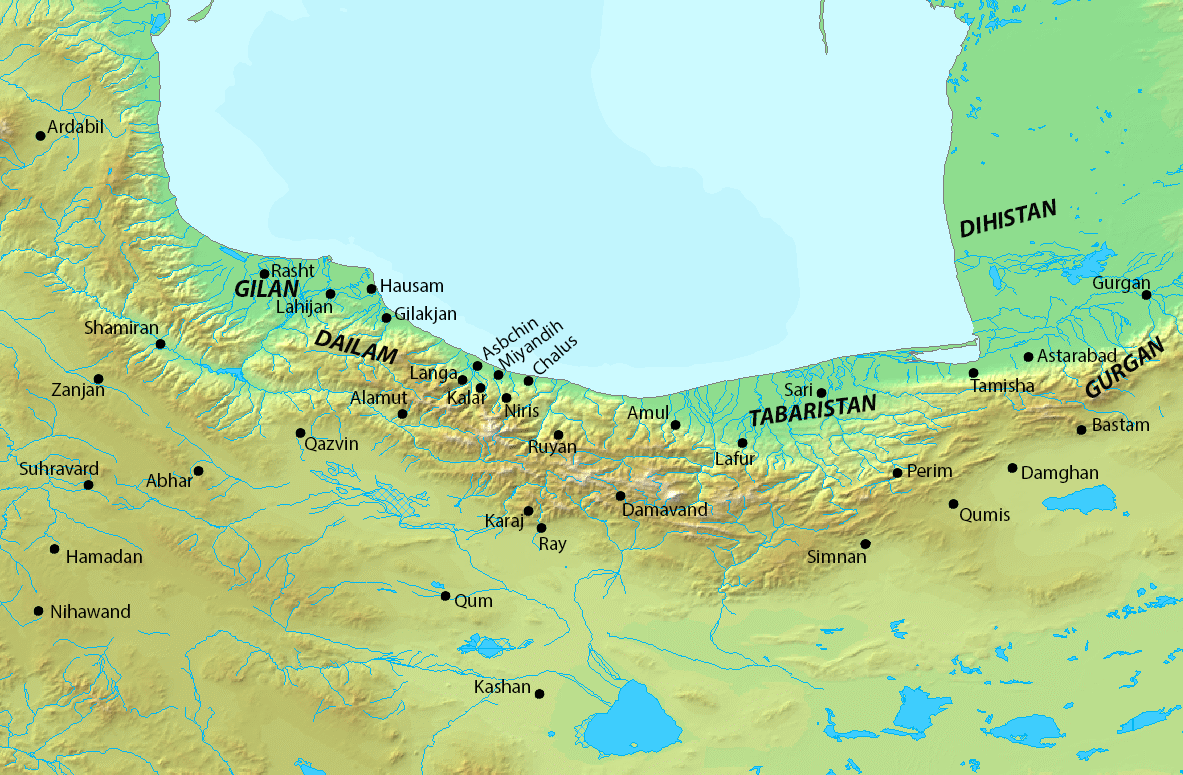

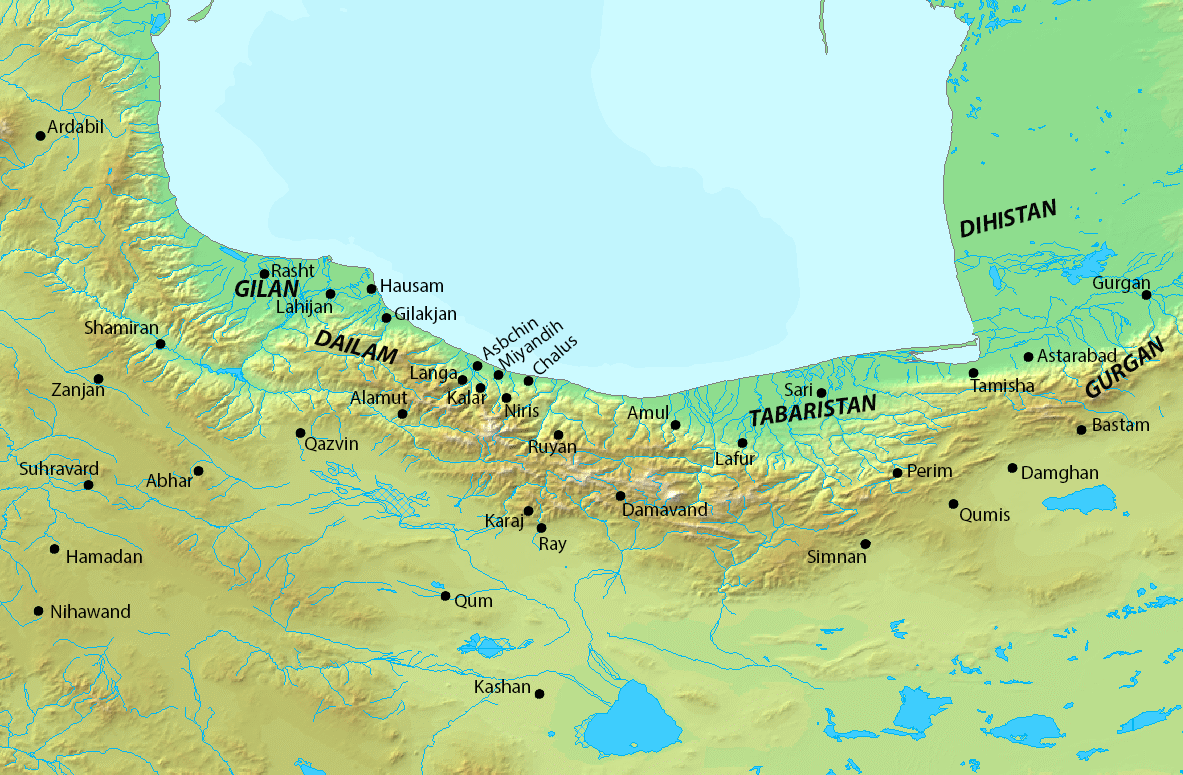

The Daylamites lived in the highlands of

The Daylamites lived in the highlands of

The descendants of Gushnasp were still ruling until in ca. 520, when Kavadh I (r. 488-531) appointed his eldest son, Kawus, as the king of the former lands of the Gushnaspid dynasty. In 522, Kavadh I sent an army under a certain Buya (known as ''Boes'' in Byzantine sources) against

The descendants of Gushnasp were still ruling until in ca. 520, when Kavadh I (r. 488-531) appointed his eldest son, Kawus, as the king of the former lands of the Gushnaspid dynasty. In 522, Kavadh I sent an army under a certain Buya (known as ''Boes'' in Byzantine sources) against

The Daylamites managed to resist the Arab invasion of their own mountainous homeland for several centuries under their own local rulers.Price (2005), p. 42 Warfare in the region was endemic, with raids and counter-raids by both sides. Under the Arabs, the old Iranian fortress-city of

The Daylamites managed to resist the Arab invasion of their own mountainous homeland for several centuries under their own local rulers.Price (2005), p. 42 Warfare in the region was endemic, with raids and counter-raids by both sides. Under the Arabs, the old Iranian fortress-city of

From the 9th century onwards, Daylamite foot-soldiers began to comprise an important element of the armies in Iran.

In the mid 9th century, the Abbasid Caliphate increased its need for mercenary soldiers in the

From the 9th century onwards, Daylamite foot-soldiers began to comprise an important element of the armies in Iran.

In the mid 9th century, the Abbasid Caliphate increased its need for mercenary soldiers in the

The name of the king Muta sounds uncommon, but when in the 9th and 10th centuries Daylamite chieftains appear in the spotlight in massive numbers, their names are undoubtedly pagan Iranian, not of the south-western "Persian" type, but of the north-western type: thus ''Gōrāngēj'' (not ''Kūrānkīj'', as originally interpreted) corresponds to Persian ''gōr-angēz'' "chaser of wild asses", ''Shēr-zil'' to ''Shēr-dil'' "lion’s heart", etc. The medieval Persian geographer

The name of the king Muta sounds uncommon, but when in the 9th and 10th centuries Daylamite chieftains appear in the spotlight in massive numbers, their names are undoubtedly pagan Iranian, not of the south-western "Persian" type, but of the north-western type: thus ''Gōrāngēj'' (not ''Kūrānkīj'', as originally interpreted) corresponds to Persian ''gōr-angēz'' "chaser of wild asses", ''Shēr-zil'' to ''Shēr-dil'' "lion’s heart", etc. The medieval Persian geographer

Middle Persian

Middle Persian or Pahlavi, also known by its endonym Pārsīk or Pārsīg () in its later form, is a Western Middle Iranian language which became the literary language of the Sasanian Empire. For some time after the Sasanian collapse, Middle P ...

: ''Daylamīgān''; fa, دیلمیان ''Deylamiyān'') were an Iranian people

Iranians or Iranian people may refer to:

* Iranian peoples, Indo-European ethno-linguistic group living predominantly in Iran and other parts of the Middle East and the Caucasus, as well as parts of Central Asia and South Asia

** Persians, Irania ...

inhabiting the Daylam

Daylam, also known in the plural form Daylaman (and variants such as Dailam, Deylam, and Deilam), was the name of a mountainous region of inland Gilan, Iran. It was so named for its inhabitants, known as the Daylamites.

The Church of the East es ...

—the mountainous regions of northern Iran

Iran, officially the Islamic Republic of Iran, and also called Persia, is a country located in Western Asia. It is bordered by Iraq and Turkey to the west, by Azerbaijan and Armenia to the northwest, by the Caspian Sea and Turkmeni ...

on the southwest coast of the Caspian Sea

The Caspian Sea is the world's largest inland body of water, often described as the world's largest lake or a full-fledged sea. An endorheic basin, it lies between Europe and Asia; east of the Caucasus, west of the broad steppe of Central A ...

, now comprising the southeastern half of Gilan Province.

The Daylamites were warlike people skilled in close combat

Close combat means a violent physical confrontation between two or more opponents at short range.''MCRP 3-02B: Close Combat'', Washington, D.C.: Department Of The Navy, Headquarters United States Marine Corps, 12 February 1999Matthews, Phil, CQB ...

. They were employed as soldiers during the Sasanian Empire

The Sasanian () or Sassanid Empire, officially known as the Empire of Iranians (, ) and also referred to by historians as the Neo-Persian Empire, was the last Iranian empire before the early Muslim conquests of the 7th-8th centuries AD. Named ...

and in the subsequent Muslim empires. Daylam and Gilan were the only regions to successfully resist the Muslim conquest of Persia

The Muslim conquest of Persia, also known as the Arab conquest of Iran, was carried out by the Rashidun Caliphate from 633 to 654 AD and led to the fall of the Sasanian Empire as well as the eventual decline of the Zoroastrian religion.

The ...

, albeit many Daylamite soldiers abroad accepted Islam. In the 9th century many Daylamites adopted Zaidi Islam. In the 10th century some adopted Isma'ilism

Isma'ilism ( ar, الإسماعيلية, al-ʾIsmāʿīlīyah) is a branch or sub-sect of Shia Islam. The Isma'ili () get their name from their acceptance of Imam Isma'il ibn Jafar as the appointed spiritual successor ( imām) to Ja'far al ...

, then in the 11th century Fatimid Isma'ilism and subsequently Nizari Isma'ilism

The Nizaris ( ar, النزاريون, al-Nizāriyyūn, fa, نزاریان, Nezāriyān) are the largest segment of the Ismaili Muslims, who are the second-largest branch of Shia Islam after the Twelvers. Nizari teachings emphasize independent ...

. Both the Zaidis and the Nizaris maintained a strong presence in Iran up until the 16th century rise of the Safavids

Safavid Iran or Safavid Persia (), also referred to as the Safavid Empire, '. was one of the greatest Iranian empires after the 7th-century Muslim conquest of Persia, which was ruled from 1501 to 1736 by the Safavid dynasty. It is often conside ...

who espoused the Twelver

Twelver Shīʿīsm ( ar, ٱثْنَا عَشَرِيَّة; '), also known as Imāmīyyah ( ar, إِمَامِيَّة), is the largest branch of Shīʿa Islam, comprising about 85 percent of all Shīʿa Muslims. The term ''Twelver'' refers t ...

sect of Shia Islam

Shīʿa Islam or Shīʿīsm is the second-largest branch of Islam. It holds that the Islamic prophet Muhammad designated ʿAlī ibn Abī Ṭālib as his successor (''khalīfa'') and the Imam (spiritual and political leader) after him, mos ...

. In the 930s, the Daylamite Buyid dynasty

The Buyid dynasty ( fa, آل بویه, Āl-e Būya), also spelled Buwayhid ( ar, البويهية, Al-Buwayhiyyah), was a Shia Iranian dynasty of Daylamite origin, which mainly ruled over Iraq and central and southern Iran from 934 to 1062. Co ...

emerged and managed to gain control over much of modern-day Iran, which it held until the coming of the Seljuk Turks

The Seljuk dynasty, or Seljukids ( ; fa, سلجوقیان ''Saljuqian'', alternatively spelled as Seljuqs or Saljuqs), also known as Seljuk Turks, Seljuk Turkomans "The defeat in August 1071 of the Byzantine emperor Romanos Diogenes

by the Turk ...

in the mid-11th century.

Origins and language

The Daylamites lived in the highlands of

The Daylamites lived in the highlands of Daylam

Daylam, also known in the plural form Daylaman (and variants such as Dailam, Deylam, and Deilam), was the name of a mountainous region of inland Gilan, Iran. It was so named for its inhabitants, known as the Daylamites.

The Church of the East es ...

, part of the Alborz

The Alborz ( fa, البرز) range, also spelled as Alburz, Elburz or Elborz, is a mountain range in northern Iran that stretches from the border of Azerbaijan along the western and entire southern coast of the Caspian Sea and finally runs nort ...

range, between Tabaristan

Tabaristan or Tabarestan ( fa, طبرستان, Ṭabarestān, or mzn, تبرستون, Tabarestun, ultimately from Middle Persian: , ''Tapur(i)stān''), was the name applied to a mountainous region located on the Caspian coast of northern Iran. ...

and Gilan. However, the earliest Zoroastrian

Zoroastrianism is an Iranian religion and one of the world's oldest organized faiths, based on the teachings of the Iranian-speaking prophet Zoroaster. It has a dualistic cosmology of good and evil within the framework of a monotheisti ...

and Christian sources indicate that the Daylamites originally arrived from eastern Anatolia

Anatolia, tr, Anadolu Yarımadası), and the Anatolian plateau, also known as Asia Minor, is a large peninsula in Western Asia and the westernmost protrusion of the Asian continent. It constitutes the major part of modern-day Turkey. The re ...

near the Tigris

The Tigris () is the easternmost of the two great rivers that define Mesopotamia, the other being the Euphrates. The river flows south from the mountains of the Armenian Highlands through the Syrian and Arabian Deserts, and empties into the ...

, where Iranian ethnolinguistic groups, including Zazas

The Zazas (also known as Kird, Kirmanc or Dimili) are a people in eastern Turkey who traditionally speak the Zaza language, a western Iranian language written in the Latin script. Their heartland consists of Tunceli and Bingöl provinces and ...

, live today.

They spoke the Daylami language

The Daylami language, also known as ''Daylamite'', ''Deilami'', ''Dailamite'', or ''Deylami'' (Deilami: , from the name of the Daylam region), is an extinct language that was one of the northwestern branch of the Iranian languages. It was spoken ...

, a now-extinct Northwestern Iranian language

The Western Iranic languages are a branch of the Iranic languages, attested from the time of Old Persian (6th century BC) and Median.

Languages

The traditional Northwestern branch is a convention for non-Southwestern languages, rather than a g ...

similar to that of the neighbouring Gilites. During the Sasanian Empire, they were employed as high-quality infantry. According to the Byzantine

The Byzantine Empire, also referred to as the Eastern Roman Empire or Byzantium, was the continuation of the Roman Empire primarily in its eastern provinces during Late Antiquity and the Middle Ages, when its capital city was Constantinopl ...

historians Procopius

Procopius of Caesarea ( grc-gre, Προκόπιος ὁ Καισαρεύς ''Prokópios ho Kaisareús''; la, Procopius Caesariensis; – after 565) was a prominent late antique Greek scholar from Caesarea Maritima. Accompanying the Roman gen ...

and Agathias

Agathias or Agathias Scholasticus ( grc-gre, Ἀγαθίας σχολαστικός; Martindale, Jones & Morris (1992), pp. 23–25582/594), of Myrina (Mysia), an Aeolian city in western Asia Minor (Turkey), was a Greek poet and the principal histo ...

, they were a warlike people and skilled in close combat, being armed each with a sword, a shield, and spears or javelin

A javelin is a light spear designed primarily to be thrown, historically as a ranged weapon, but today predominantly for sport. The javelin is almost always thrown by hand, unlike the sling, bow, and crossbow, which launch projectiles with the ...

s.

History

Pre-Islamic period

Seleucid and Parthian period

The Daylamites first appear in historical records in the late 2nd century BCE, where they are mentioned byPolybius

Polybius (; grc-gre, Πολύβιος, ; ) was a Greek historian of the Hellenistic period. He is noted for his work , which covered the period of 264–146 BC and the Punic Wars in detail.

Polybius is important for his analysis of the mixed ...

, who erroneously calls them "Elam

Elam (; Linear Elamite: ''hatamti''; Cuneiform Elamite: ; Sumerian: ; Akkadian: ; he, עֵילָם ''ʿēlām''; peo, 𐎢𐎺𐎩 ''hūja'') was an ancient civilization centered in the far west and southwest of modern-day Iran, stretc ...

ites" () instead of "Daylamites" (). In the Middle Persian prose '' Kar-Namag i Ardashir i Pabagan'', the last ruler of the Parthian Empire

The Parthian Empire (), also known as the Arsacid Empire (), was a major Iranian political and cultural power in ancient Iran from 247 BC to 224 AD. Its latter name comes from its founder, Arsaces I, who led the Parni tribe in conqu ...

, Artabanus V

Artabanus IV, also known as Ardavan IV ( Parthian: 𐭍𐭐𐭕𐭓), incorrectly known in older scholarship as Artabanus V, was the last ruler of the Parthian Empire from c. 213 to 224. He was the younger son of Vologases V, who died in 208.

N ...

(r. 208–224) summoned all the troops from Ray

Ray may refer to:

Fish

* Ray (fish), any cartilaginous fish of the superorder Batoidea

* Ray (fish fin anatomy), a bony or horny spine on a fin

Science and mathematics

* Ray (geometry), half of a line proceeding from an initial point

* Ray (gr ...

, Damavand

Mount Damavand ( fa, دماوند ) is a dormant stratovolcano, the highest peak in Iran and Western Asia and the highest volcano in Asia and the 2nd highest volcano in the Eastern Hemisphere (after Mount Kilimanjaro), at an elevation of . ...

, Daylam, and Padishkhwargar

Padishkhwārgar was a Sasanian province in Late Antiquity, which almost corresponded to the present-day provinces of Mazandaran and Gilan. The province bordered Adurbadagan and Balasagan in the west, Gurgan in the east, and Spahan in south. Th ...

to fight the newly established Sasanian Empire. According to the ''Letter of Tansar The Letter of Tansar ( fa, نامه تنسر) was a 6th-century Sassanid propaganda instrument that portrayed the preceding Arsacid period as morally corrupt and heretical (to Zoroastrianism), and presented the first Sassanid dynast Ardashir I as h ...

'', during this period, Daylam, Gilan, and Ruyan belonged to the kingdom of Gushnasp, who was a Parthian vassal but later submitted to the first Sasanian emperor Ardashir I

Ardashir I (Middle Persian: 𐭠𐭥𐭲𐭧𐭱𐭲𐭥, Modern Persian: , '), also known as Ardashir the Unifier (180–242 AD), was the founder of the Sasanian Empire. He was also Ardashir V of the Kings of Persis, until he founded the new ...

(r. 224–242).

Sasanian period

The descendants of Gushnasp were still ruling until in ca. 520, when Kavadh I (r. 488-531) appointed his eldest son, Kawus, as the king of the former lands of the Gushnaspid dynasty. In 522, Kavadh I sent an army under a certain Buya (known as ''Boes'' in Byzantine sources) against

The descendants of Gushnasp were still ruling until in ca. 520, when Kavadh I (r. 488-531) appointed his eldest son, Kawus, as the king of the former lands of the Gushnaspid dynasty. In 522, Kavadh I sent an army under a certain Buya (known as ''Boes'' in Byzantine sources) against Vakhtang I of Iberia

Vakhtang I Gorgasali ( ka, ვახტანგ I გორგასალი, tr; or 443 – 502 or 522), of the Chosroid dynasty, was a king of Iberia, natively known as Kartli (eastern Georgia) in the second half of the 5th and first quarter o ...

. This Buya was a native of Daylam, which is proven by the fact that he bore the title ''wahriz'', a Daylamite title also used by Khurrazad, the Daylamite military commander who conquered Yemen

Yemen (; ar, ٱلْيَمَن, al-Yaman), officially the Republic of Yemen,, ) is a country in Western Asia. It is situated on the southern end of the Arabian Peninsula, and borders Saudi Arabia to the north and Oman to the northeast and ...

in 570 during the reign of Khosrow I

Khosrow I (also spelled Khosrau, Khusro or Chosroes; pal, 𐭧𐭥𐭮𐭫𐭥𐭣𐭩; New Persian: []), traditionally known by his epithet of Anushirvan ( [] "the Immortal Soul"), was the Sasanian Empire, Sasanian King of Kings of Iran from ...

(r. 531-579), and his Daylamite troops would later play a significant role in the conversion of Yemen to the nascent Islam

Islam (; ar, ۘالِإسلَام, , ) is an Abrahamic monotheistic religion centred primarily around the Quran, a religious text considered by Muslims to be the direct word of God (or '' Allah'') as it was revealed to Muhammad, the ...

. The 6th-century Byzantine historian Procopius

Procopius of Caesarea ( grc-gre, Προκόπιος ὁ Καισαρεύς ''Prokópios ho Kaisareús''; la, Procopius Caesariensis; – after 565) was a prominent late antique Greek scholar from Caesarea Maritima. Accompanying the Roman gen ...

described the Daylamites as;

:"barbarians who live...in the middle of Persia, but have never become subject to the king of the Persians. For their abode is on sheer mountainsides which are altogether inaccessible, and so they have continued to be autonomous from ancient times down to the present day; but they always march with the Persians as mercenaries when they go against their enemies. And they are all foot-soldiers, each man carrying a sword and shield and three javelins in his hand (De Bello Persico 8.14.3-9)."

The equipment of the Dailamites of the Sasanian army included swords, shield, battle-axe (''tabar-zīn''), slings, daggers, pikes, and two-pronged javelins (''zhūpīn'').

Daylamites also took part in the siege of Archaeopolis

Nokalakevi ( ka, ნოქალაქევი) also known as Archaeopolis ( grc, Ἀρχαιόπολις, "Old City") and Tsikhegoji (in Georgian "Fortress of Kuji") and according to some sources "Djikha Kvinji" in Mingrelian, is a village and ...

in 552. They supported the rebellion of Bahrām Chōbin

Bahrām Chōbīn ( fa, بهرام چوبین) or Wahrām Chōbēn (Middle Persian: ), also known by his epithet Mehrbandak ("servant of Mithra"), was a nobleman, general, and political leader of the late Sasanian Empire and briefly its ruler as Ba ...

against Khosrow II

Khosrow II (spelled Chosroes II in classical sources; pal, 𐭧𐭥𐭮𐭫𐭥𐭣𐭩, Husrō), also known as Khosrow Parviz (New Persian: , "Khosrow the Victorious"), is considered to be the last great Sasanian king (shah) of Iran, ruling fr ...

, but he later employed an elite detachment of 4000 Daylamites as part of his guard. They also distinguished themselves at the Yemeni campaign of Wahriz and in the battles against the forces of Justin II

Justin II ( la, Iustinus; grc-gre, Ἰουστῖνος, Ioustînos; died 5 October 578) or Justin the Younger ( la, Iustinus minor) was Eastern Roman Emperor from 565 until 578. He was the nephew of Justinian I and the husband of Sophia, the ...

.

Some Muslim sources maintain that following the Sasanian defeat in the Battle of al-Qādisiyyah

The Battle of al-Qadisiyyah ( ar, مَعْرَكَة ٱلْقَادِسِيَّة, Maʿrakah al-Qādisīyah; fa, نبرد قادسیه, Nabard-e Qâdisiyeh) was an armed conflict which took place in 636 CE between the Rashidun Caliphate and th ...

, the 4000-strong Daylamite contingent of the Sasanian guard, along with other Iranian units, defected to the Arab side, converting to Islam.

Islamic period

Resistance to the Arabs

The Daylamites managed to resist the Arab invasion of their own mountainous homeland for several centuries under their own local rulers.Price (2005), p. 42 Warfare in the region was endemic, with raids and counter-raids by both sides. Under the Arabs, the old Iranian fortress-city of

The Daylamites managed to resist the Arab invasion of their own mountainous homeland for several centuries under their own local rulers.Price (2005), p. 42 Warfare in the region was endemic, with raids and counter-raids by both sides. Under the Arabs, the old Iranian fortress-city of Qazvin

Qazvin (; fa, قزوین, , also Romanized as ''Qazvīn'', ''Qazwin'', ''Kazvin'', ''Kasvin'', ''Caspin'', ''Casbin'', ''Casbeen'', or ''Ghazvin'') is the largest city and capital of the Province of Qazvin in Iran. Qazvin was a capital of the ...

continued in its Sasanian-era role as a bulwark against Daylamite raids. According to the historian al-Tabari

( ar, أبو جعفر محمد بن جرير بن يزيد الطبري), more commonly known as al-Ṭabarī (), was a Muslim historian and scholar from Amol, Tabaristan. Among the most prominent figures of the Islamic Golden Age, al-Tabari ...

, Daylamites and Turkic peoples

The Turkic peoples are a collection of diverse ethnic groups of West, Central, East, and North Asia as well as parts of Europe, who speak Turkic languages.. "Turkic peoples, any of various peoples whose members speak languages belonging to ...

were considered the worst enemies of the Arab Muslims. The Abbasid Caliphate

The Abbasid Caliphate ( or ; ar, الْخِلَافَةُ الْعَبَّاسِيَّة, ') was the third caliphate to succeed the Islamic prophet Muhammad. It was founded by a dynasty descended from Muhammad's uncle, Abbas ibn Abdul-Muttal ...

penetrated the region and occupied parts of it, but their control was never very effective.

Shortly after 781, the Nestorian

Nestorianism is a term used in Christian theology and Church history to refer to several mutually related but doctrinarily distinct sets of teachings. The first meaning of the term is related to the original teachings of Christian theologian ...

monk Shubhalishoʿ Shubhalishoʿ ( ar, Shuwḥālīshōʿ) was an East Syriac monk, missionary and martyr of the late 8th century.

According to Thomas of Margā's ''Book of Governors'', Shubhalishoʿ was an Ishmaelite (i.e., an Arab) and his native language was Ar ...

began evangelizing the Daylamites and converting them to Christianity. He and his associates made only a little headway before encountering competition from Islam. During the reign of Harun al-Rashid

Abu Ja'far Harun ibn Muhammad al-Mahdi ( ar

, أبو جعفر هارون ابن محمد المهدي) or Harun ibn al-Mahdi (; or 766 – 24 March 809), famously known as Harun al-Rashid ( ar, هَارُون الرَشِيد, translit=Hārūn ...

(r. 785–809), several Shia Muslims

Shīʿa Islam or Shīʿīsm is the second-largest branch of Islam. It holds that the Islamic prophet Muhammad designated ʿAlī ibn Abī Ṭālib as his successor (''khalīfa'') and the Imam (spiritual and political leader) after him, mos ...

fled to the largely pagan Daylamites, with a few Zoroastrians and Christians, to escape persecution. Among these refugees were some Alids

The Alids are those who claim descent from the '' rāshidūn'' caliph and Imam ʿAlī ibn Abī Ṭālib (656–661)—cousin, son-in-law, and companion of the Islamic prophet Muhammad—through all his wives. The main branches are the (in ...

, who began the gradual conversion of the Daylamites to Shia Islam. Nevertheless, a strong Iranian identity remained ingrained in the peoples of the region, along with an anti-Arab mentality. Local rulers such as the Buyids

The Buyid dynasty ( fa, آل بویه, Āl-e Būya), also spelled Buwayhid ( ar, البويهية, Al-Buwayhiyyah), was a Shia Iranian dynasty of Daylamite origin, which mainly ruled over Iraq and central and southern Iran from 934 to 1062. Coup ...

and the Ziyarids, made a point of celebrating old Iranian and Zoroastrian festivals.

The Daylamite expansion

From the 9th century onwards, Daylamite foot-soldiers began to comprise an important element of the armies in Iran.

In the mid 9th century, the Abbasid Caliphate increased its need for mercenary soldiers in the

From the 9th century onwards, Daylamite foot-soldiers began to comprise an important element of the armies in Iran.

In the mid 9th century, the Abbasid Caliphate increased its need for mercenary soldiers in the Royal Guard

A royal guard is a group of military bodyguards, soldiers or armed retainers responsible for the protection of a royal person, such as the emperor or empress, king or queen, or prince or princess. They often are an elite unit of the regular arm ...

and the army, thus they began recruiting Daylamites, who at the period were not as strong in numbers as the Turks, Khorasanis, the Farghanis, and the Egypt

Egypt ( ar, مصر , ), officially the Arab Republic of Egypt, is a List of transcontinental countries, transcontinental country spanning the North Africa, northeast corner of Africa and Western Asia, southwest corner of Asia via a land bridg ...

ian tribesmen of the Maghariba. From 912/3 to 916/7, a Daylamite soldier, Ali ibn Wahsudhan, was chief of police ('' ṣāḥib al-shurṭa'') in Isfahan

Isfahan ( fa, اصفهان, Esfahân ), from its ancient designation ''Aspadana'' and, later, ''Spahan'' in middle Persian, rendered in English as ''Ispahan'', is a major city in the Greater Isfahan Region, Isfahan Province, Iran. It is lo ...

during the reign of al-Muqtadir

Abu’l-Faḍl Jaʿfar ibn Ahmad al-Muʿtaḍid ( ar, أبو الفضل جعفر بن أحمد المعتضد) (895 – 31 October 932 AD), better known by his regnal name Al-Muqtadir bi-llāh ( ar, المقتدر بالله, "Mighty in God"), w ...

(r. 908–929). For many decades, "it remained customary for the Caliph's personal guards to include the Daylamites as well as the ubiquitous Turks".Bosworth (1975) The Buyid

The Buyid dynasty ( fa, آل بویه, Āl-e Būya), also spelled Buwayhid ( ar, البويهية, Al-Buwayhiyyah), was a Shia Iranian dynasty of Daylamite origin, which mainly ruled over Iraq and central and southern Iran from 934 to 1062. Co ...

''amīr''s, who were Daylamite themselves, supplemented their army of Daylamite infantrymen with Turkic cavalrymen. Daylamites were among the people comprising the Seljuq army, and Ghaznavids

The Ghaznavid dynasty ( fa, غزنویان ''Ġaznaviyān'') was a culturally Persianate, Sunni Muslim dynasty of Turkic ''mamluk'' origin, ruling, at its greatest extent, large parts of Persia, Khorasan, much of Transoxiana and the northwes ...

also employed them as elite infantry.Bosworth (1986)

Islamic sources record their characteristic painted shields and two-pronged short spears (in fa, ژوپین ''zhūpīn''; in ar, مزراق ''mizrāq'') which could be used either for thrusting or for hurling as a javelin. Their characteristic battle tactic was advancing with a shield wall

A shield wall ( or in Old English, in Old Norse) is a military formation that was common in ancient and medieval warfare. There were many slight variations of this formation,

but the common factor was soldiers standing shoulder to should ...

and using their spears and battle-axes from behind.

Culture

Religion

The Daylamites were most likely adherents of some form of Iranian paganism, while a minority of them wereZoroastrian

Zoroastrianism is an Iranian religion and one of the world's oldest organized faiths, based on the teachings of the Iranian-speaking prophet Zoroaster. It has a dualistic cosmology of good and evil within the framework of a monotheisti ...

and Nestorian Christian

Nestorianism is a term used in Christian theology and Church history to refer to several mutually related but doctrinarily distinct sets of teachings. The first meaning of the term is related to the original teachings of Christian theologian ...

. According to al-Biruni

Abu Rayhan Muhammad ibn Ahmad al-Biruni (973 – after 1050) commonly known as al-Biruni, was a Khwarazmian Iranian in scholar and polymath during the Islamic Golden Age. He has been called variously the "founder of Indology", "Father of Co ...

, the Daylamites and Gilites "lived by the rule laid down by the mythical Afridun." The Church of the East

The Church of the East ( syc, ܥܕܬܐ ܕܡܕܢܚܐ, ''ʿĒḏtā d-Maḏenḥā'') or the East Syriac Church, also called the Church of Seleucia-Ctesiphon, the Persian Church, the Assyrian Church, the Babylonian Church or the Nestorian C ...

had spread among them due to the activities of John of Dailam

Saint John of Dailam ( syr, ܝܘܚܢܢ ܕܝܠܡܝܐ '), was a 7th-century East Syriac Christian saint and monk, who founded several monasteries in Mesopotamia and Persia.

According to the hagiographical ''Syriac Life of John of Dailam'', John was ...

, and bishoprics are reported in the remote area as late as the 790s, while it is possible that some remnants survived there until the 14th century.

Names

The name of the king Muta sounds uncommon, but when in the 9th and 10th centuries Daylamite chieftains appear in the spotlight in massive numbers, their names are undoubtedly pagan Iranian, not of the south-western "Persian" type, but of the north-western type: thus ''Gōrāngēj'' (not ''Kūrānkīj'', as originally interpreted) corresponds to Persian ''gōr-angēz'' "chaser of wild asses", ''Shēr-zil'' to ''Shēr-dil'' "lion’s heart", etc. The medieval Persian geographer

The name of the king Muta sounds uncommon, but when in the 9th and 10th centuries Daylamite chieftains appear in the spotlight in massive numbers, their names are undoubtedly pagan Iranian, not of the south-western "Persian" type, but of the north-western type: thus ''Gōrāngēj'' (not ''Kūrānkīj'', as originally interpreted) corresponds to Persian ''gōr-angēz'' "chaser of wild asses", ''Shēr-zil'' to ''Shēr-dil'' "lion’s heart", etc. The medieval Persian geographer Estakhri

Abu Ishaq Ibrahim ibn Muhammad al-Farisi al-Istakhri () (also ''Estakhri'', fa, استخری, i.e. from the Iranian city of Istakhr, b. - d. 346 AH/AD 957) was a 10th-century travel-author and geographer who wrote valuable accounts in Ara ...

differentiates between Persian and Daylami and comments that in the highlands of Daylam there was a tribe that spoke a language different from that of Daylam and Gilan, perhaps a surviving non-Iranian language.

Customs, equipment and appearance

Many habits and customs of the Daylamites have been recorded in historical records. Their men were strikingly tough and capable of lasting terrible privations. They were armed withjavelin

A javelin is a light spear designed primarily to be thrown, historically as a ranged weapon, but today predominantly for sport. The javelin is almost always thrown by hand, unlike the sling, bow, and crossbow, which launch projectiles with the ...

s and battle axe

A battle axe (also battle-axe, battle ax, or battle-ax) is an axe specifically designed for combat. Battle axes were specialized versions of utility axes. Many were suitable for use in one hand, while others were larger and were deployed two-ha ...

s, and had tall shields painted in gray colours. In battle, they would usually form a wall

A wall is a structure and a surface that defines an area; carries a load; provides security, shelter, or soundproofing; or, is decorative. There are many kinds of walls, including:

* Walls in buildings that form a fundamental part of the s ...

with their shields against the attackers. Some Daylamites would use javelins with burning naphtha

Naphtha ( or ) is a flammable liquid hydrocarbon mixture.

Mixtures labelled ''naphtha'' have been produced from natural gas condensates, petroleum distillates, and the distillation of coal tar and peat. In different industries and regions ' ...

. A poetic portrayal of Daylamite armed combat is present in Fakhruddin As'ad Gurgani

Fakhruddin As'ad Gurgani, also spelled as Fakhraddin Asaad Gorgani ( fa, فخرالدين اسعد گرگانی), was an 11th-century Persian poet. He versified the story of Vis and Rāmin, a story from the Arsacid (Parthian) period. The Iranian ...

's ''Vis and Rāmin Vis and Rāmin ( fa, ويس و رامين, ''Vis o Rāmin'') is a classical Persian love story. The epic was composed in poetry by Fakhruddin As'ad Gurgani (or "Gorgani") in the 11th century. Gorgani claimed a Sassanid origin for the story, but ...

''. A major disadvantage of the Daylamites was the low amount of cavalry that they had, which compelled them to work with Turkic mercenaries.

The Daylamites exaggeratedly mourned over their dead, and even over themselves in failure. In 963, the Buyid ruler of Iraq

Iraq,; ku, عێراق, translit=Êraq officially the Republic of Iraq, '; ku, کۆماری عێراق, translit=Komarî Êraq is a country in Western Asia. It is bordered by Turkey to Iraq–Turkey border, the north, Iran to Iran–Iraq ...

, Mu'izz al-Dawla

Ahmad ibn Buya ( Persian: احمد بن بویه, died April 8, 967), after 945 better known by his ''laqab'' of Mu'izz al-Dawla ( ar, المعز الدولة البويهي, "Fortifier of the Dynasty"), was the first of the Buyid emirs of Iraq ...

, popularized Mourning of Muharram

The Mourning of Muharram (also known as Azadari, Remembrance of Muharram or Muharram Observances) is a set of commemoration rituals observed primarily by Shia people. The commemoration falls in Muharram, the first month of the Islamic calendar. ...

in Baghdad

Baghdad (; ar, بَغْدَاد , ) is the capital of Iraq and the second-largest city in the Arab world after Cairo. It is located on the Tigris near the ruins of the ancient city of Babylon and the Sassanid Persian capital of Ctesiphon ...

, which may have played a part in the evolution of the ta'zieh

Ta'zieh ( ar, تعزية; fa, تعزیه; ur, ) means comfort, condolence, or expression of grief. It comes from roots ''aza'' (عزو and عزى) which means mourning.

Depending on the region, time, occasion, religion, etc. the word can sig ...

.

Estakhri describes the Daylamites as a bold but inconsiderate people, being thin in appearance and having fluffy hair. They practised agriculture

Agriculture or farming is the practice of cultivating plants and livestock. Agriculture was the key development in the rise of sedentary human civilization, whereby farming of domesticated species created food surpluses that enabled people ...

and had herd

A herd is a social group of certain animals of the same species, either wild or domestic. The form of collective animal behavior associated with this is called '' herding''. These animals are known as gregarious animals.

The term ''herd'' i ...

s, but only a few horses. They also grew rice, fished, and produced silk textiles. According to al-Muqaddasi

Shams al-Dīn Abū ʿAbd Allāh Muḥammad ibn Aḥmad ibn Abī Bakr al-Maqdisī ( ar, شَمْس ٱلدِّيْن أَبُو عَبْد ٱلله مُحَمَّد ابْن أَحْمَد ابْن أَبِي بَكْر ٱلْمَقْدِسِي), ...

, the Daylamites were handsome and had beards. According to the author of the '' Hudud al-'Alam'', the Daylamite women took part in agriculture like men. According to Rudhrawari, they were "equals of men in strength of mind, force of character, and participation in the management of affairs." Furthermore, the Daylamites also strictly practised endogamy

Endogamy is the practice of marrying within a specific social group, religious denomination, caste, or ethnic group, rejecting those from others as unsuitable for marriage or other close personal relationships.

Endogamy is common in many cultu ...

.

See also

*Rudkhan Castle

Rudkhan Castle ( fa, قلعه رودخان, glk, رودخان دژ); also Roodkhan Castle, is a brick and stone medieval fortress in Iran that was built by the Talysh people to defend against the Arab invaders during the Muslim conquest of Pers ...

* Alamut Castle

Alamut ( fa, الموت, meaning "eagle's nest") is a ruined mountain fortress located in the Alamut region in the South Caspian province of Qazvin near the Masoudabad region in Iran, approximately 200 km (130 mi) from present-day Teh ...

* Lambsar Castle

Lambsar ( fa, لمبسر, also pronounced Lamsar), Lamasar, Lambasar, Lambesar () or Lomasar () was probably the largest and the most fortified of the Ismaili castles. The fortress is located in the central Alburz mountains, south of the Caspian ...

* Fayruz Al Daylami

* Al-Daylami

References

Sources

* * * * * * * * * * * * * * * {{cite book, last= Zakeri, first= Mohsen, title=Sāsānid Soldiers in Early Muslim Society: The Origins of ʿAyyārān and Futuwwa, url=https://books.google.com/books?id=VfYnu5F20coC, year=1995, publisher=Otto Harrassowitz, location=Wiesbaden, isbn=978-3-447-03652-8 Historical Iranian peoples History of Talysh