Cyril Connolly on:

[Wikipedia]

[Google]

[Amazon]

Cyril Vernon Connolly

Cyril Vernon Connolly

Connolly married his second wife, Barbara Skelton, in 1950. His third wife, whom he married in 1959, was Deirdre Craven, a granddaughter of

Connolly married his second wife, Barbara Skelton, in 1950. His third wife, whom he married in 1959, was Deirdre Craven, a granddaughter of

Bibliography and critical checklist

*

''Guardian'' profile of Connolly

by

Cyril Vernon Connolly

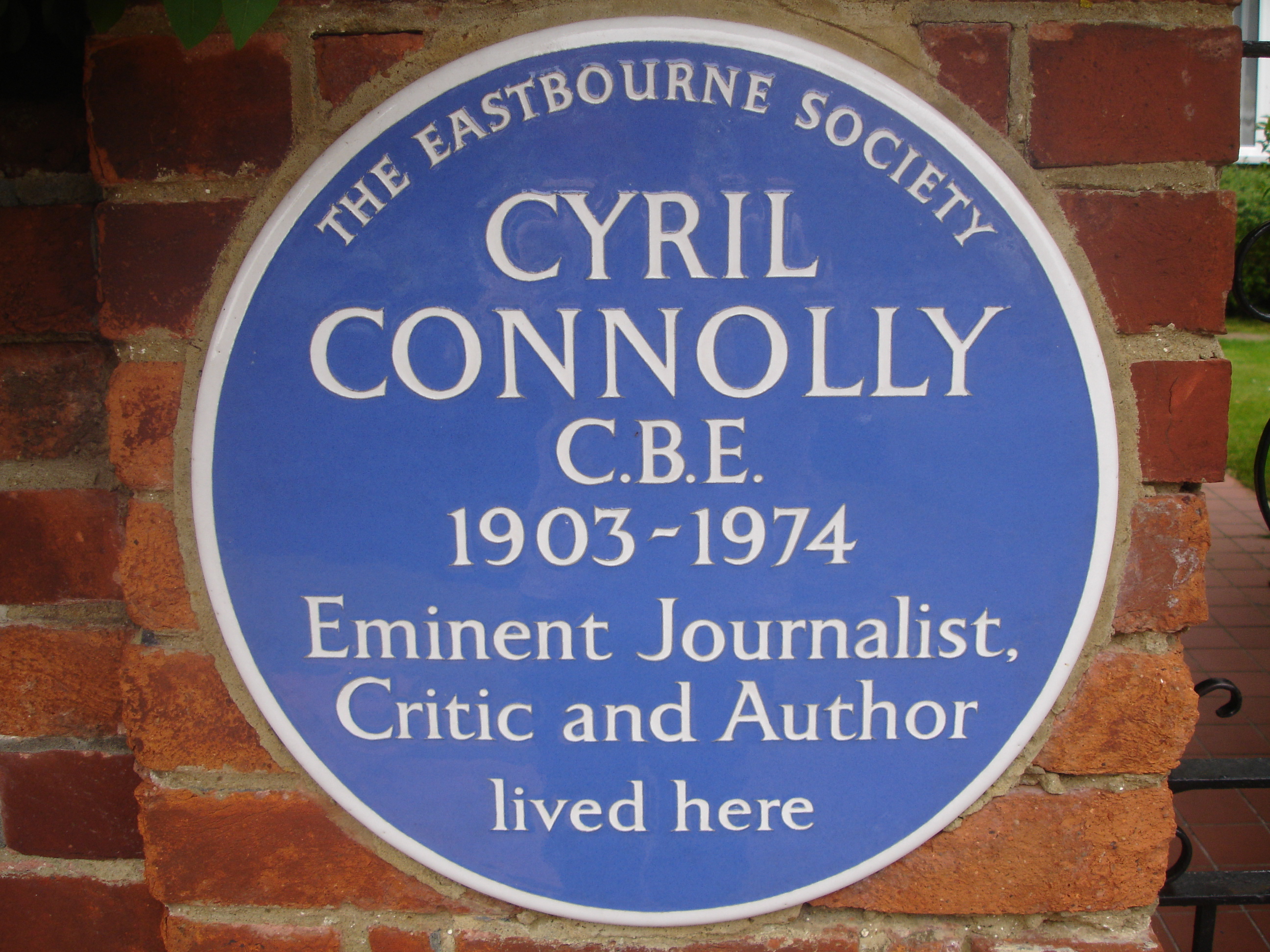

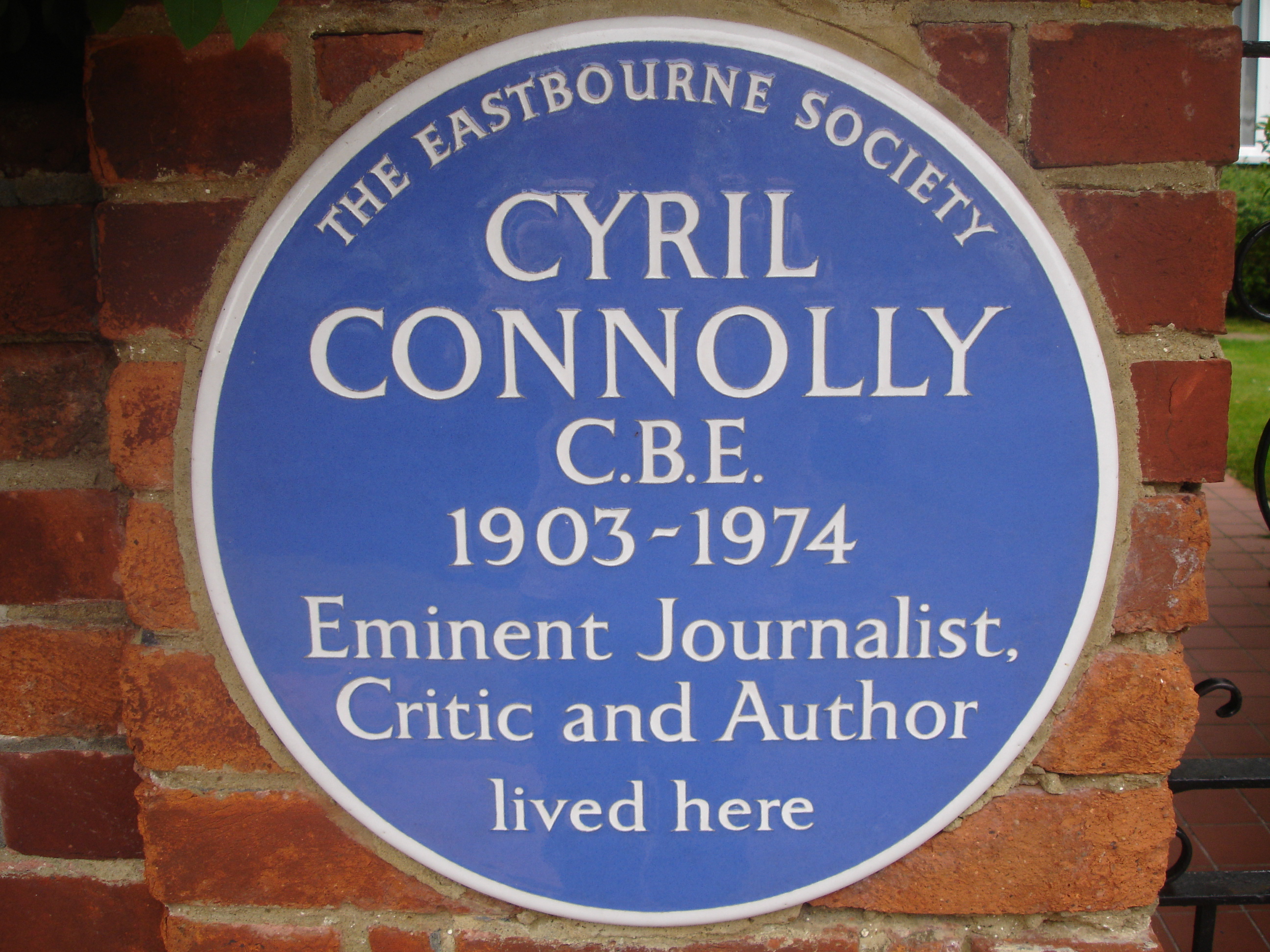

Cyril Vernon Connolly CBE

The Most Excellent Order of the British Empire is a British order of chivalry, rewarding contributions to the arts and sciences, work with charitable and welfare organisations,

and public service outside the civil service. It was established o ...

(10 September 1903 – 26 November 1974) was an English literary critic and writer. He was the editor of the influential literary magazine '' Horizon'' (1940–49) and wrote '' Enemies of Promise'' (1938), which combined literary criticism with an autobiographical

An autobiography, sometimes informally called an autobio, is a self-written account of one's own life.

It is a form of biography.

Definition

The word "autobiography" was first used deprecatingly by William Taylor in 1797 in the English peri ...

exploration of why he failed to become the successful author of fiction that he had aspired to be in his youth.

Early life

Cyril Connolly was born inCoventry

Coventry ( or ) is a city in the West Midlands, England. It is on the River Sherbourne. Coventry has been a large settlement for centuries, although it was not founded and given its city status until the Middle Ages. The city is governed b ...

, Warwickshire

Warwickshire (; abbreviated Warks) is a county in the West Midlands region of England. The county town is Warwick, and the largest town is Nuneaton. The county is famous for being the birthplace of William Shakespeare at Stratford-upon-Av ...

, the only child of Major Matthew William Kemble Connolly

Matthew William Kemble Connolly (13 February 1872 – 24 February 1947) was a British army officer and malacologist.

Biography

Connolly was born at Bath, the son of Vice-Admiral Matthew Connolly, R.N., and his wife Harriet Kemble. He was educated ...

(1872–1947), an officer in the King's Own Yorkshire Light Infantry, by his Anglo-Irish wife, Muriel Maud Vernon, daughter of Colonel Edward Vernon (1838–1913) J.P., D.L., of Clontarf Castle, Co. Dublin. His parents had met while his father was serving in Ireland, and his father's next posting was to South Africa.Jeremy Lewis, ''Cyril Connolly: A Life'', Jonathan Cape, 1997. Connolly's father was also a malacologist

Malacology is the branch of invertebrate zoology that deals with the study of the Mollusca (mollusks or molluscs), the second-largest phylum of animals in terms of described species after the arthropods. Mollusks include snails and slugs, clams, ...

(the scientific study of the Mollusca, i.e. snails, clams, octopus, etc.) and mineral collector of some reputation and collected many samples in Africa. Cyril Connolly's childhood days were spent with his father in South Africa, with his mother's family at Clontarf Castle, and with his paternal grandmother in Bath, Somerset, and other parts of England.Cyril Connolly, ''Enemies of Promise'', Routledge & Kegan Paul, 1938.

Connolly was educated at St Cyprian's School, Eastbourne

Eastbourne () is a town and seaside resort in East Sussex, on the south coast of England, east of Brighton and south of London. Eastbourne is immediately east of Beachy Head, the highest chalk sea cliff in Great Britain and part of the la ...

, where he enjoyed the company of George Orwell and Cecil Beaton

Sir Cecil Walter Hardy Beaton, (14 January 1904 – 18 January 1980) was a British fashion, portrait and war photographer, diarist, painter, and interior designer, as well as an Oscar–winning stage and costume designer for films and the t ...

. He was a favourite of the formidable headmistress Mrs Wilkes but was later to criticise the "character-building" ethos of the school. He wrote, "Orwell proved to me that there existed an alternative to character, Intelligence. Beaton showed me another, Sensibility." Connolly won the Harrow History Prize, pushing Orwell into second place, and the English prize leaving Orwell with Classics. He then won a scholarship to Eton, a year after Orwell.

Eton

At Eton, after a traumatic first few terms, he settled into a comfortable routine. He won over his early tormentor Godfrey Meynell and became a popular wit. In 1919 his parents moved to The Lock House on theBasingstoke Canal

The Basingstoke Canal is an English canal, completed in 1794, built to connect Basingstoke with the River Thames at Weybridge via the Wey Navigation.

From Basingstoke, the canal passes through or near Greywell, North Warnborough, Odiham, ...

at Frimley Green

Frimley Green is a large village and ward of in the Borough of Surrey Heath in Surrey, England, approximately southwest of central London. It is south of the town of Frimley.

Lakeside Country Club was the national venue for the BDO int ...

. At Eton, Connolly was involved in romantic intrigues and school politics, which he described in '' Enemies of Promise''.

He established a reputation as an intellectual and earned the respect of Dadie Rylands

George Humphrey Wolferstan Rylands (23 October 1902 – 16 January 1999), known as Dadie Rylands, was a British literary scholar and theatre director.

Rylands was born at the Down House, Tockington, Gloucestershire, to Thomas Kirkland R ...

and Denis King-Farlow. Connolly's particular circle included Denis Dannreuther, Bobbie Longden and Roger Mynors. In summer 1921, his father took him on a holiday to France, initiating Connolly's love of travel. The following winter he went with his mother to Mürren

Mürren is a traditional Walser mountain village in the Bernese Highlands of Switzerland, at an elevation of above sea level and it cannot be reached by public road. It is also one of the popular tourist spots in Switzerland, and summer and w ...

, where he became friends with Anthony Knebworth.

By this time his parents were living separate lives, his mother having established a relationship with another army officer and his father becoming an increasingly heavy drinker and absorbed in his study of slugs and snails. In 1922, Connolly achieved academic success winning the Rosebery History Prize, and followed by the Brackenbury History scholarship to Balliol College, Oxford. In the spring, he visited St Cyprian's to report his achievement to his old headmaster before setting off on a trip to Spain with a school friend.

Returning moneyless, he spent the night in a kip at St Martins, London. In his last term at Eton, he was elected to Pop, which brought him into contact with others he respected, including Nico Davies, Teddy Jessel and Lord Dunglass. He established rapport with Brian Howard, but, he concluded, "moral cowardice and academic outlook debarred him from making friends with Harold Acton

Sir Harold Mario Mitchell Acton (5 July 1904 – 27 February 1994) was a British writer, scholar, and aesthete who was a prominent member of the Bright Young Things. He wrote fiction, biography, history and autobiography. During his stay in C ...

, Oliver Messel

Oliver Hilary Sambourne Messel (13 January 1904 – 13 July 1978) was an English artist and one of the foremost stage designers of the 20th century.

Early life

Messel was born in London, the second son of Lieutenant-Colonel Leonard Messel a ...

, Robert Byron

Robert Byron (26 February 1905 – 24 February 1941) was a British travel writer, best known for his travelogue ''The Road to Oxiana''. He was also a noted writer, art critic and historian.

Biography

He was the son of Eric Byron, a civil engi ...

, Henry Green

Henry Green was the pen name of Henry Vincent Yorke (29 October 1905 – 13 December 1973), an English writer best remembered for the novels '' Party Going'', ''Living'' and ''Loving''. He published a total of nine novels between 1926 and 1952 ...

and Anthony Powell

Anthony Dymoke Powell ( ; 21 December 1905 – 28 March 2000) was an English novelist best known for his 12-volume work ''A Dance to the Music of Time'', published between 1951 and 1975. It is on the list of longest novels in English.

Powell' ...

". Connolly was for years afterwards nostalgic about his time at Eton.

Oxford

Connolly undertook a tour of Germany, Austria andHungary

Hungary ( hu, Magyarország ) is a landlocked country in Central Europe. Spanning of the Pannonian Basin, Carpathian Basin, it is bordered by Slovakia to the north, Ukraine to the northeast, Romania to the east and southeast, Serbia to the ...

before starting at Oxford University. After his cloistered existence as a King's Scholar

A King's Scholar is a foundation scholar (elected on the basis of good academic performance and usually qualifying for reduced fees) of one of certain public schools. These include Eton College; The King's School, Canterbury; The King's School ...

at Eton, Connolly felt uncomfortable with the hearty beer-drinking rugby and rowing types at Oxford. His own circle included his Eton friends Mynors and Dannreuther, who were at Balliol with him, and Kenneth Clark

Kenneth Mackenzie Clark, Baron Clark (13 July 1903 – 21 May 1983) was a British art historian, museum director, and broadcaster. After running two important art galleries in the 1930s and 1940s, he came to wider public notice on television ...

, whom he met through Bobbie Longden at Kings. He wrote: "The only exercise we took was running up bills." His intellectual mentors were the Dean of Balliol, Francis Fortescue Urquhart, often referred to as "Sligger", who organised reading parties on the continent, and the Dean of Wadham, Maurice Bowra

Sir Cecil Maurice Bowra, (; 8 April 1898 – 4 July 1971) was an English classical scholar, literary critic and academic, known for his wit. He was Warden of Wadham College, Oxford, from 1938 to 1970, and served as Vice-Chancellor of the Univers ...

.

Connolly's academic career languished while his Oxford years were characterised by his travel adventures. In January 1923, he went with Urquhart and other collegers to Italy. In March, he undertook his annual visit to Spain and in September, he went on the annual trip with the college group to Urquhart's chalet in French Alps

The French Alps are the portions of the Alps mountain range that stand within France, located in the Auvergne-Rhône-Alpes and Provence-Alpes-Côte d'Azur regions. While some of the ranges of the French Alps are entirely in France, others, such as ...

. On his return, he visited his father, now in a hotel in South Kensington, close to the Natural History Museum

A natural history museum or museum of natural history is a scientific institution with natural history collections that include current and historical records of animals, plants, fungi, ecosystems, geology, paleontology, climatology, and more. ...

. At the end of the year, he went to Italy and Tunis

''Tounsi'' french: Tunisois

, population_note =

, population_urban =

, population_metro = 2658816

, population_density_km2 =

, timezone1 = CET

, utc_offset1 ...

. At Oxford, in 1924, he made a new friend Patrick Balfour, in the spring he went to Spain and in the summer of 1924, he went successively to Greece and Crete

Crete ( el, Κρήτη, translit=, Modern: , Ancient: ) is the largest and most populous of the Greek islands, the 88th largest island in the world and the fifth largest island in the Mediterranean Sea, after Sicily, Sardinia, Cyprus, ...

, Urquhart's chalet in the Alps and Naples

Naples (; it, Napoli ; nap, Napule ), from grc, Νεάπολις, Neápolis, lit=new city. is the regional capital of Campania and the third-largest city of Italy, after Rome and Milan, with a population of 909,048 within the city's adminis ...

. He spent Christmas with his parents in a rare get-together at the Lock House in Hampshire and at the beginning of 1925, he went with the college group to Minehead with Urquhart.

In his last year at Oxford, he was cultivating friendships with younger students Anthony Powell, Henry Yorke and Peter Quennell

Sir Peter Courtney Quennell (9 March 1905 – 27 October 1993) was an English biographer, literary historian, editor, essayist, poet, and critic. He wrote extensively on social history.

Life

Born in Bickley, Kent, the son of architect C. ...

. In spring he was back in Spain, before returning to Oxford to take his final exams.

Drifting

Connolly left Balliol in 1925 with a third class degree in history. He struggled to find employment, while his friends and family sought to pay off his extensive debts. In summer he went for his annual stay at Urquhart's chalet in the French Alps, and in the autumn went to Spain and Portugal. He obtained a post tutoring a boy inJamaica

Jamaica (; ) is an island country situated in the Caribbean Sea. Spanning in area, it is the third-largest island of the Greater Antilles and the Caribbean (after Cuba and Hispaniola). Jamaica lies about south of Cuba, and west of His ...

and set sail for the Caribbean in November 1925. He returned to England in April 1926 on a banana boat in the company of Alwyn Williams, headmaster of Winchester College

Winchester College is a public school (fee-charging independent day and boarding school) in Winchester, Hampshire, England. It was founded by William of Wykeham in 1382 and has existed in its present location ever since. It is the oldest of ...

. He enrolled as a special constable in the General Strike, but it was over before he was actively involved. He responded to an advertisement to work as a secretary for Montague Summers

Augustus Montague Summers (10 April 1880 – 10 August 1948) was an English author, clergyman, and teacher. He initially prepared for a career in the Church of England at Oxford and Lichfield, and was ordained as an Anglican deacon in 1908. He ...

but was warned off by his friends. Then in June 1926 he found a post as a secretary/companion to Logan Pearsall Smith

Logan Pearsall Smith (18 October 1865 – 2 March 1946) was an American-born British essayist and critic. Harvard and Oxford educated, he was known for his aphorisms and epigrams, and was an expert on 17th Century divines. His ''Words and Idioms ...

, who was based in Chelsea

Chelsea or Chelsey may refer to:

Places Australia

* Chelsea, Victoria

Canada

* Chelsea, Nova Scotia

* Chelsea, Quebec

United Kingdom

* Chelsea, London, an area of London, bounded to the south by the River Thames

** Chelsea (UK Parliament consti ...

and also had a house called Big Chilling near Warsash

Warsash is a village in southern Hampshire, England, situated at the mouth of the River Hamble, west of the area known as Locks Heath. Boating plays an important part in the village's economy, and the village has a sailing club. It is also home ...

in Hampshire

Hampshire (, ; abbreviated to Hants) is a ceremonial and non-metropolitan county in western South East England on the coast of the English Channel. Home to two major English cities on its south coast, Southampton and Portsmouth, Hampshire ...

, overlooking the Solent. Pearsall Smith was to give Connolly an important introduction to literary life, and he influenced his ideas on the role of a writer with a distaste for journalism. Pearsall Smith gave Connolly £8 a week, whether Smith was around or not, and moreover gave him the run of Big Chilling.

Beginning of literary career

In August 1926, Connolly metDesmond MacCarthy

Sir Charles Otto Desmond MacCarthy FRSL (20 May 1877 – 7 June 1952) was a British writer and the foremost literary and dramatic critic of his day. He was a member of the Cambridge Apostles, the intellectual secret society, from 1896.

Early li ...

, who had come to stay at Big Chilling. MacCarthy was the literary editor of the ''New Statesman

The ''New Statesman'' is a British Political magazine, political and cultural magazine published in London. Founded as a weekly review of politics and literature on 12 April 1913, it was at first connected with Sidney Webb, Sidney and Beatrice ...

'' and was to be another major influence on Connolly's development. MacCarthy invited Connolly to write book reviews for the ''New Statesman''. Later that year, Connolly made a trip to Budapest

Budapest (, ; ) is the capital and most populous city of Hungary. It is the ninth-largest city in the European Union by population within city limits and the second-largest city on the Danube river; the city has an estimated population ...

and Eastern Europe and then spent the winter of 1926–1927 in London. Pearsall Smith took Connolly with him to Spain in the spring, and Connolly then set off on his own to North Africa and Italy. They met up again in Florence

Florence ( ; it, Firenze ) is a city in Central Italy and the capital city of the Tuscany Regions of Italy, region. It is the most populated city in Tuscany, with 383,083 inhabitants in 2016, and over 1,520,000 in its metropolitan area.Bilan ...

, where Kenneth Clark was working with Bernard Berenson

Bernard Berenson (June 26, 1865 – October 6, 1959) was an American art historian specializing in the Renaissance. His book ''The Drawings of the Florentine Painters'' was an international success. His wife Mary is thought to have had a large ...

who had married Pearsall Smith's sister.

Connolly departed for Sicily

(man) it, Siciliana (woman)

, population_note =

, population_blank1_title =

, population_blank1 =

, demographics_type1 = Ethnicity

, demographics1_footnotes =

, demographi ...

then returned to England via Vienna

en, Viennese

, iso_code = AT-9

, registration_plate = W

, postal_code_type = Postal code

, postal_code =

, timezone = CET

, utc_offset = +1

, timezone_DST ...

, :Prague and Dresden

Dresden (, ; Upper Saxon: ''Dräsdn''; wen, label= Upper Sorbian, Drježdźany) is the capital city of the German state of Saxony and its second most populous city, after Leipzig. It is the 12th most populous city of Germany, the fourth ...

. Connolly's first signed work in the ''New Statesman'', a review of Laurence Sterne

Laurence Sterne (24 November 1713 – 18 March 1768), was an Anglo-Irish novelist and Anglican cleric who wrote the novels ''The Life and Opinions of Tristram Shandy, Gentleman'' and '' A Sentimental Journey Through France and Italy'', publishe ...

, appeared in June 1927. In July he set off to Normandy

Normandy (; french: link=no, Normandie ; nrf, Normaundie, Nouormandie ; from Old French , plural of ''Normant'', originally from the word for "northman" in several Scandinavian languages) is a geographical and cultural region in Northwestern ...

with his mother and then for his last stay at the chalet in the Alps. In August 1927, he was invited to become a regular reviewer and joined the staff of the ''New Statesman''. His first review in September was of ''The Hotel'' by Elizabeth Bowen

Elizabeth Bowen CBE (; 7 June 1899 – 22 February 1973) was an Irish-British novelist and short story writer notable for her books about the "big house" of Irish landed Protestants as well her fiction about life in wartime London.

Life

...

. Also in September, Connolly moved into a flat at Yeoman's Row with Patrick Balfour. He was working on various works that never saw the light of day: a novel ''Green Endings'', a travel book on Spain, his diary and ''A Partial Guide to the Balkans''. He approached Cecil Beaton to draw the cover design for the last and he received an advance for the work although it was eventually lost.

However, he started contributing pieces to various publications that appeared under his own name and various pseudonyms. At this time he developed a fascination with low life and prostitution and spent time in the poorer parts of London seeking them out (while other contemporaries were seeking out tramps). At the same time, he had developed an infatuation with Alix Kilroy whom he had met on a train back from the continent and used to wait outside her office for a sight of her. He then made a more positive romantic approach to Racy Fisher, one of a pair of nieces of Desmond MacCarthy's wife, Molly.

However, their father Admiral Fisher wanted them to have nothing to do with a penniless writer and, in February 1928, forbade further contact.

Sharing a flat with Balfour, Connolly's social circle expanded with new friends like Bob Boothby and Gladwyn Jebb

Hubert Miles Gladwyn Jebb, 1st Baron Gladwyn (25 April 1900 – 24 October 1996) was a prominent British civil servant, diplomat and politician who served as the acting secretary-general of the United Nations between 1945 and 1946.

Early ...

. However, he was ill at ease and in April 1928 set off for Paris

Paris () is the Capital city, capital and List of communes in France with over 20,000 inhabitants, most populous city of France, with an estimated population of 2,165,423 residents in 2019 in an area of more than 105 km² (41 sq mi), ma ...

, where he met Pearsall Smith and Cecil Beaton and visited brothels posing as a journalist. He went on to Italy, where he stayed with Berenson and Mrs Keppel where he was taken with her daughter Violet Trefusis

Violet Trefusis (''née'' Keppel; 6 June 1894 – 29 February 1972) was an English socialite and author. She is chiefly remembered for her lengthy affair with the writer Vita Sackville-West that both women continued after their respective marria ...

. Then via Venice

Venice ( ; it, Venezia ; vec, Venesia or ) is a city in northeastern Italy and the capital of the Veneto region. It is built on a group of 118 small islands that are separated by canals and linked by over 400 bridges. The isla ...

and East European cities he made his way to Berlin

Berlin ( , ) is the capital and List of cities in Germany by population, largest city of Germany by both area and population. Its 3.7 million inhabitants make it the European Union's List of cities in the European Union by population within ci ...

to meet up with Jebb.

Jebb and Connolly stayed with Harold Nicolson in the company of Ivor Novello and Christopher Sykes and then made a tour of Germany. Connolly returned to Paris in May, borrowing money from Pearsall Smith so he could live cheaply in the rue Delambre. In Paris, he met Mara Andrews, a poetic lesbian who was in love with an absent American girl called Jean Bakewell. On the way back to London, Connolly stayed with Nicolson and his wife, Vita Sackville-West

Victoria Mary, Lady Nicolson, CH (née Sackville-West; 9 March 1892 – 2 June 1962), usually known as Vita Sackville-West, was an English author and garden designer.

Sackville-West was a successful novelist, poet and journalist, as wel ...

, at Sissinghurst

Sissinghurst is a small village in the borough of Tunbridge Wells in Kent, England. Originally called ''Milkhouse Street'' (also referred to as ''Mylkehouse''), Sissinghurst changed its name in the 1850s, possibly to avoid association with the smu ...

.

In August Connolly set off on his travels again to Germany, this time with Bobbie Longden and Raymond Mortimer and the experience gave rise to the essay "Conversations in Berlin" which MacCarthy published in his new magazine '' Life and Letters''. Connolly travelled separately to Villefranche and spent five weeks in Barcelona

Barcelona ( , , ) is a city on the coast of northeastern Spain. It is the capital and largest city of the autonomous community of Catalonia, as well as the second most populous municipality of Spain. With a population of 1.6 million within ci ...

with Longden before returning to London. Boothby lent him his London flat and he shared Gerald Brenan

Edward FitzGerald "Gerald" Brenan, CBE, MC (7 April 1894 – 19 January 1987) was a British writer and hispanist who spent much of his life in Spain.

Brenan is best known for ''The Spanish Labyrinth'', a historical work on the background t ...

's fascination with working-class prostitutes with experiences that appeared in his fragment for a novel ''The English Malady''. He spent Christmas at Sledmere

Sledmere is a village in the East Riding of Yorkshire, England, about north-west of Driffield on the B1253 road.

The village lies in a civil parish which is also officially called "Sledmere" by the Office for National Statistics, although th ...

with the Sykes family.

At the beginning of 1929, Connolly went briefly to Paris and just before returning to London, he met Jean Bakewell and stayed an extra night to get to know her. After a while, he was drawn to Paris again and, through Jean and Mara, became acquainted with the bohemian Montparnasse

Montparnasse () is an area in the south of Paris, France, on the left bank of the river Seine, centred at the crossroads of the Boulevard du Montparnasse and the Rue de Rennes, between the Rue de Rennes and boulevard Raspail. Montparnasse has bee ...

set, including Alfred Perles

Alfred Perlès (1897–1990) was an Austrian writer (in later life a British citizen), who was most famous for his associations with Henry Miller, Lawrence Durrell, and Anaïs Nin.

Life and works

Born in Vienna in 1897, to Czech Jewish parents ...

and Gregor Michonze who was to become the basis for Rascasse in ''The Rock Pool

''The Rock Pool'' is a novel written by Cyril Connolly, first published in 1936. It is Connolly's only novel and is set at the end of season in a small resort in the south of France. Connolly's main character, Naylor, starts with a study of the ...

''. He also met James Joyce

James Augustine Aloysius Joyce (2 February 1882 – 13 January 1941) was an Irish novelist, poet, and literary critic. He contributed to the modernist avant-garde movement and is regarded as one of the most influential and important writers of ...

about whom he wrote ''The Position of Joyce'' which appeared in ''Life and Letters''. Connolly and Bakewell went to Spain together where they met up with Peter Quennell. Connolly then went to Berlin to stay with Nicolson until the latter managed to remove him as "not perhaps the ideal guest"

Unable to return to Big Chilling, he was stuck in Berlin for a month before returning to London. John Betjeman had moved into his room at Yeoman's Row, so he went to stay with Enid Bagnold

Enid Algerine Bagnold, Lady Jones, (27 October 1889 – 31 March 1981) was a British writer and playwright known for the 1935 story ''National Velvet''.

Early life

Enid Algerine Bagnold was born on 27 October 1889 in Rochester, Kent, daughte ...

at Rottingdean

Rottingdean is a village in the city of Brighton and Hove, on the south coast of England. It borders the villages of Saltdean, Ovingdean and Woodingdean, and has a historic centre, often the subject of picture postcards.

Name

The name Rotting ...

before visiting Dorset with Quennell. Bakewell had returned to America in the summer and was planning to return to Paris in the autumn to start a course at the Sorbonne. She had agreed before her departure to marry Connolly and Connolly established himself in Paris in September. They spent most of the rest of the year in Paris, and started their collection of pets, first ferrets and then lemurs. Connolly spent Christmas again at Sledmere.

Marriage

In February 1930, aged 26, Connolly and Bakewell set off for America. They married in New York on 5 April 1930. Jean Bakewell "was to prove one of the more liberating forces in his life... an uncomplicated hedonist, independent, adventurous, celebrating the moment... An attractive personality: warm, generous, witty and approachable...." She provided modest financial support that enabled him to enjoy travels, particularly around theMediterranean

The Mediterranean Sea is a sea connected to the Atlantic Ocean, surrounded by the Mediterranean Basin and almost completely enclosed by land: on the north by Western Europe, Western and Southern Europe and Anatolia, on the south by North Africa ...

, hospitality and good food and drink. The newly married couple lived in various spots in England including the Cavendish Hotel, Bury Street, Bath, and Big Chilling, before in July 1930 settling at Sanary, near Toulon

Toulon (, , ; oc, label= Provençal, Tolon , , ) is a city on the French Riviera and a large port on the Mediterranean coast, with a major naval base. Located in the Provence-Alpes-Côte d'Azur region, and the Provence province, Toulon is th ...

, in France. There their close neighbours were Edith Wharton and Aldous Huxley

Aldous Leonard Huxley (26 July 1894 – 22 November 1963) was an English writer and philosopher. He wrote nearly 50 books, both novels and non-fiction works, as well as wide-ranging essays, narratives, and poems.

Born into the prominent Huxle ...

.

Although Connolly admired Huxley, the two men failed to establish a rapport, and the wives fell out. Connolly's bohemian home with the disorder of the lemurs was shunned and with debts rising they were forced to scrounge off Jean's mother. Sometime in 1931, they left Sanary and toured Provence

Provence (, , , , ; oc, Provença or ''Prouvènço'' , ) is a geographical region and historical province of southeastern France, which extends from the left bank of the lower Rhône to the west to the Italian border to the east; it is bor ...

, Normandy, Brittany

Brittany (; french: link=no, Bretagne ; br, Breizh, or ; Gallo: ''Bertaèyn'' ) is a peninsula, historical country and cultural area in the west of modern France, covering the western part of what was known as Armorica during the period ...

, Spain, Morocco

Morocco (),, ) officially the Kingdom of Morocco, is the westernmost country in the Maghreb region of North Africa. It overlooks the Mediterranean Sea to the north and the Atlantic Ocean to the west, and has land borders with Algeria t ...

and Majorca, before returning to Chagfor, Devon. In November, they found a flat near Belgrave Square

Belgrave Square is a large 19th-century garden square in London. It is the centrepiece of Belgravia, and its architecture resembles the original scheme of property contractor Thomas Cubitt who engaged George Basevi for all of the terraces fo ...

, and Connolly made his first contribution to the ''New Statesman'' in two years.

Connolly was also approached by John Betjeman of the ''Architectural Review

''The Architectural Review'' is a monthly international architectural magazine. It has been published in London since 1896. Its articles cover the built environment – which includes landscape, building design, interior design and urbanism ...

'' to act as an art critic. Connolly's art critiques appeared in the magazine in 1932, and he visited Betjeman at his home at Uffington. There, he would meet Evelyn Waugh

Arthur Evelyn St. John Waugh (; 28 October 1903 – 10 April 1966) was an English writer of novels, biographies, and travel books; he was also a prolific journalist and book reviewer. His most famous works include the early satires '' Decl ...

, who delighted in teasing Connolly. The Connollys enjoyed being part of a sophisticated literary social scene in London, but towards the end of the year, Jean had to undergo a gynaecological operation. As a result, she could not have a child, and it was hard for her to control her weight.

In February 1933, Connolly took Jean to Greece to recover, where they met Brian Howard. While they were in Athens there was an attempted coup d'état, which Connolly later reported in the ''New Statesman'' as "Spring Revolution". The Connollys then went with Howard and his boyfriend to Spain and the Algarve. After a row in a bar, they were incarcerated in a police cell and were sent back to England with the help of the British Embassy. In June, encouraged by Enid Bagnold

Enid Algerine Bagnold, Lady Jones, (27 October 1889 – 31 March 1981) was a British writer and playwright known for the 1935 story ''National Velvet''.

Early life

Enid Algerine Bagnold was born on 27 October 1889 in Rochester, Kent, daughte ...

, they rented a house at Rottingdean

Rottingdean is a village in the city of Brighton and Hove, on the south coast of England. It borders the villages of Saltdean, Ovingdean and Woodingdean, and has a historic centre, often the subject of picture postcards.

Name

The name Rotting ...

.

Writing to Bagnold from Cannes in September, Jean complained that their cheques were being bounced and she asked Bagnold to appeal to her husband Sir Roderick Jones of Reuters for help in work. That was dismissed, and in November, the letting agent

A letting agent is a facilitator through which an agreement is made between a landlord and tenant for the rental of a residential property. This is commonly used in countries using British English, including countries of the Commonwealth. In th ...

s for the Rottingdean property wrote an appalling report on the state in which the Connollys had left the place.

Early in 1934, the Connollys took a flat at 312A King's Road

King's Road or Kings Road (or sometimes the King's Road, especially when it was the king's private road until 1830, or as a colloquialism by middle/upper class London residents), is a major street stretching through Chelsea and Fulham, both ...

, where they entertained their friends, including Waugh and Quennell. Elizabeth Bowen arranged a dinner with Virginia Woolf

Adeline Virginia Woolf (; ; 25 January 1882 28 March 1941) was an English writer, considered one of the most important modernist 20th-century authors and a pioneer in the use of stream of consciousness as a narrative device.

Woolf was born i ...

and her husband when Connolly and Virginia Woolf took an instant dislike to each other.

During the year, the Connollys went to Mallow and Cork in Ireland. At the end of the year. Connolly met Dylan Thomas at a party and early in 1935 invited him in the company of Anthony Powell, Waugh, Robert Byron and Desmond and Mollie McCarthy. By then, Connolly's father was finding himself short of funds and was no longer prepared to bail out his son.

However, Mrs Warner, Jean's mother, funded an expedition to Paris, Juan-les-Pins, Venice, Yugoslavia

Yugoslavia (; sh-Latn-Cyrl, separator=" / ", Jugoslavija, Југославија ; sl, Jugoslavija ; mk, Југославија ;; rup, Iugoslavia; hu, Jugoszlávia; rue, label=Pannonian Rusyn, Югославия, translit=Juhoslavija ...

and Budapest. In Paris, Connolly spent some time with Jack Kahane, the avant garde publisher, and Henry Miller

Henry Valentine Miller (December 26, 1891 – June 7, 1980) was an American novelist. He broke with existing literary forms and developed a new type of semi-autobiographical novel that blended character study, social criticism, philosophical ref ...

, with whom he established a strong rapport after an initial unsuccessful meeting. In Budapest, they found themselves in the same hotel as Edward, Prince of Wales and Wallis Simpson

Wallis, Duchess of Windsor (born Bessie Wallis Warfield, later Simpson; June 19, 1896 – April 24, 1986), was an American socialite and wife of the former King Edward VIII. Their intention to marry and her status as a divorcée caused a ...

.

In 1934, Connolly was working on a trilogy: ''Humane Killer'', ''The English Malady'' and ''The Rock Pool

''The Rock Pool'' is a novel written by Cyril Connolly, first published in 1936. It is Connolly's only novel and is set at the end of season in a small resort in the south of France. Connolly's main character, Naylor, starts with a study of the ...

''. Only ''The Rock Pool'' was completed, the others remaining only as fragments.

First books

Connolly's only novel, ''The Rock Pool'' (1936), is a satirical work describing a covey of dissolute drifters at an end of season French seaside resort, which was based on his experiences in the south of France. It was initially accepted by a London publishing house but it changed its mind. Faber and Faber was one of the publishers that rejected it and so Connolly took it to Jack Kahane, who published it in Paris in 1936. Connolly followed it up with a book of non-fiction, '' Enemies of Promise'' (1938), the second half of which is autobiographical. In it he attempted to explain his failure to produce the literary masterpiece that he and others believed that he should have been capable of writing.''Horizon''

In 1940, Connolly founded the influential literary magazine '' Horizon'', with Peter Watson, its financial backer and ''de facto'' art editor. He edited ''Horizon'' until 1950, withStephen Spender

Sir Stephen Harold Spender (28 February 1909 – 16 July 1995) was an English poet, novelist and essayist whose work concentrated on themes of social injustice and the class struggle. He was appointed Poet Laureate Consultant in Poetry by th ...

as an uncredited associate editor until early 1941. He was briefly (1942–1943) the literary editor for ''The Observer

''The Observer'' is a British newspaper published on Sundays. It is a sister paper to ''The Guardian'' and '' The Guardian Weekly'', whose parent company Guardian Media Group Limited acquired it in 1993. First published in 1791, it is the ...

'' until a disagreement with David Astor

Francis David Langhorne Astor, CH (5 March 1912 – 7 December 2001) was an English newspaper publisher, editor of ''The Observer'' at the height of its circulation and influence, and member of the Astor family, "the landlords of New York".

E ...

. During World War II

World War II or the Second World War, often abbreviated as WWII or WW2, was a world war that lasted from 1939 to 1945. It involved the vast majority of the world's countries—including all of the great powers—forming two opposing ...

, he wrote ''The Unquiet Grave

"The Unquiet Grave" is an English folk song in which a young man's grief over the death of his true love is so deep that it disturbs her eternal sleep. It was collected in 1868 by Francis James Child as Child Ballad number 78. One of the more comm ...

'', a noteworthy collection of observations and quotes, under the pseudonym ' Palinurus'.

From 1952 until his death, he was joint chief book reviewer (with Raymond Mortimer) for ''The Sunday Times

''The Sunday Times'' is a British newspaper whose circulation makes it the largest in Britain's quality press market category. It was founded in 1821 as ''The New Observer''. It is published by Times Newspapers Ltd, a subsidiary of News UK, w ...

''.

In 1962, Connolly wrote ''Bond Strikes Camp'', a spoof account of Ian Fleming's character engaged in heroic escapades of dubious propriety as suggested by the title and written with Fleming's support. It appeared in ''London Magazine

''The London Magazine'' is the title of six different publications that have appeared in succession since 1732. All six have focused on the arts, literature and miscellaneous topics.

1732–1785

''The London Magazine, or, Gentleman's Monthly I ...

'' and in an expensive limited edition printed by the Shenval Press, Frith Street, London. It later appeared in ''Previous Convictions''.

Connolly had previously collaborated with Fleming in 1952 in writing an account of the Cambridge Spies Guy Burgess

Guy Francis de Moncy Burgess (16 April 1911 – 30 August 1963) was a British diplomat and Soviet agent, and a member of the Cambridge Five spy ring that operated from the mid-1930s to the early years of the Cold War era. His defection in 1951 ...

and Donald MacLean entitled ''The Missing Diplomats'', an early publication for Fleming's Queen Anne Press

The Queen Anne Press (logo stylized QAP) is a small publisher (originally a private press).

History

It was created in 1951 by Lord Kemsley, proprietor of ''The Sunday Times'', to publish the works of contemporary authors. In 1952, as a wedding ...

.

Personal life

Connolly was married three times. His first wife Jean Bakewell (1910–1950) left him in 1939, moving back to the United States. She later became the wife of Laurence Vail (former husband ofPeggy Guggenheim

Marguerite "Peggy" Guggenheim ( ; August 26, 1898 – December 23, 1979) was an American art collector, bohemian and socialite. Born to the wealthy New York City Guggenheim family, she was the daughter of Benjamin Guggenheim, who went down wi ...

and Kay Boyle

Kay Boyle (February 19, 1902 – December 27, 1992) was an American novelist, short story writer, educator, and political activist. She was a Guggenheim Fellow and O. Henry Award winner.

Early years

The granddaughter of a publisher, Boyle was ...

) but, following years of health problems, she died of a stroke while on a trip to Paris at the age of 39.

Connolly married his second wife, Barbara Skelton, in 1950. His third wife, whom he married in 1959, was Deirdre Craven, a granddaughter of

Connolly married his second wife, Barbara Skelton, in 1950. His third wife, whom he married in 1959, was Deirdre Craven, a granddaughter of James Craig, 1st Viscount Craigavon

James Craig, 1st Viscount Craigavon PC PC (NI) DL (8 January 1871 – 24 November 1940), was a leading Irish unionist and a key architect of Northern Ireland as a devolved region within the United Kingdom. During the Home Rule Crisis of 1 ...

, by whom he had two children later in life, including the writer Cressida Connolly

Cressida Connolly (born 14 January 1960) is an English novelist, biographer, journalist and critic.

Personal life

Connolly grew up in Sussex. She is the only daughter of the critic and writer Cyril Connolly (died 26 November 1974). Her mother, ...

(born 1960). After Connolly's death in 1974, his widow married Peter Levi

Peter Chad Tigar Levi, FSA, FRSL (16 May 1931, in Ruislip – 1 February 2000, in Frampton-on-Severn) was a British poet, archaeologist, Jesuit priest, travel writer, biographer, academic and prolific reviewer and critic. He was Professor of P ...

.

In 1967, Connolly settled in Eastbourne, to the amusement of Beaton, who suggested he was lured back by the cakes they had enjoyed in school outings to the town. He died suddenly on 26 November 1974, having continued to the end as a ''Sunday Times'' journalist, and was buried in Berwick churchyard, Sussex. His grave bears the inscription ''Intus aquae dulces vivoque sedilia saxo'' (''Aeneid

The ''Aeneid'' ( ; la, Aenē̆is or ) is a Latin epic poem, written by Virgil between 29 and 19 BC, that tells the legendary story of Aeneas, a Trojan who fled the fall of Troy and travelled to Italy, where he became the ancestor of th ...

'' book IX: "Within, fresh water and seats in the living rock.")

Since 1976, Connolly's papers and personal library of over 8,000 books have been housed at the University of Tulsa.

Assessment

In ''The Unquiet Grave'' Connolly writes: "Approaching forty, sense of total failure:... Never will I make that extra effort to live according to reality which alone makes good writing possible: hence the manic-depressiveness of my style,—which is either bright, cruel and superficial; or pessimistic; moth-eaten with self-pity."Kenneth Tynan

Kenneth Peacock Tynan (2 April 1927 – 26 July 1980) was an English theatre critic and writer. Making his initial impact as a critic at ''The Observer'', he praised Osborne's ''Look Back in Anger'' (1956), and encouraged the emerging wave of ...

, writing in the March 1954 '' Harper's Bazaar'', praised Connolly's style as 'one of the most glittering of English literary possessions.'

Dave Mason, in an essay on crime and booksellers, asserts that Connolly had a reputation amongst booksellers as a conniving thief: "That a man so important to modern literature acted so shoddily as to break an honourable code of conduct and steal from booksellers who had trusted him." He continues: "This man, Cyril Connolly, cheated and defrauded booksellers the way despicable conmen prey on elderly innocents, with no regard for basic decency."

References in popular culture

*Cyril Connolly's name appears in a coda to the Monty Python song "Eric the Half-a-Bee

"Eric the Half-a-Bee" is a song by the British comedy troupe Monty Python that was composed by Eric Idle with lyrics co-written with John Cleese. It first appeared as the A-side of the group's second 7" single, released in a mono mix on 17 No ...

", as a mishearing of the words "semi-carnally". Despite being corrected, the backing vocalists then sing "Cyril Connolly" to the melody of the song.Cleese, Idle, Jones: "Eric the Half a Bee", ''Monty Python's Previous Record'', 1972, Charisma Records. The same comedians made another reference to Connolly in ''The Brand New Monty Python Bok

''The Brand New Monty Python Bok'' was the second book to be published by the British comedy troupe Monty Python. Edited by Eric Idle, it was published by Methuen Publishing, Methuen Books in 1973 and contained more print-style comic pieces than th ...

'', which includes a facsimile Penguin paperback, ''Norman Henderson's Diary'', complete with (invented) praise from Connolly.

*The critic and publisher Everard Spruce in Evelyn Waugh

Arthur Evelyn St. John Waugh (; 28 October 1903 – 10 April 1966) was an English writer of novels, biographies, and travel books; he was also a prolific journalist and book reviewer. His most famous works include the early satires '' Decl ...

's ''Sword of Honour

The ''Sword of Honour'' is a trilogy of novels by Evelyn Waugh which loosely parallel Waugh's experiences during the Second World War. Published by Chapman & Hall from 1952 to 1961, the novels are: ''Men at Arms'' (1952); ''Officers and Gent ...

'' trilogy is a satire of Connolly.

*Ed Spain, "the Captain" in Nancy Mitford

Nancy Freeman-Mitford (28 November 1904 – 30 June 1973), known as Nancy Mitford, was an English novelist, biographer, and journalist. The eldest of the Mitford sisters, she was regarded as one of the "bright young things" on the London ...

's 1951 novel ''The Blessing'' is a satire of Connolly.

* Michael Nelson's novel '' A Room in Chelsea Square'' (1958) is a thinly disguised homosexualised account about Connolly's time editing ''Horizon''.

*Elaine Dundy

Elaine Rita Dundy (née Brimberg; August 1, 1921 – May 1, 2008) was an American novelist, biographer, journalist, actress and playwright.

Early life

She was born Elaine Rita Brimberg in New York City. Her Polish Jewish immigrant father, ...

's novel ''The Old Man and Me'' (1964) is based on her affair with Connolly.

*A film producer in Julian MacLaren-Ross's 1964 thriller ''My Name is Love'' is based on Connolly. MacLaren-Ross repeated many of the descriptions verbatim in his later memoir of Connolly.

*Connolly is quoted as saying "Better to write for yourself and have no public than to write for the public and have no self" in Season 5, Episode 7 of ''Criminal Minds

''Criminal Minds'' is an American police procedural crime drama television series created and produced by Jeff Davis. The series premiered on CBS on September 22, 2005, and originally concluded on February 19, 2020; it was revived in 2022. It ...

''.

*Since the film ''A Business Affair'' (1994) is adapted from Barbara Skelton's memoirs of her marriage to Cyril Connolly, Jonathan Pryce's character Alec Bolton in the film is based on Cyril Connolly

*Connolly is also fictionalised in Ian McEwan

Ian Russell McEwan, (born 21 June 1948) is an English novelist and screenwriter. In 2008, ''The Times'' featured him on its list of "The 50 greatest British writers since 1945" and ''The Daily Telegraph'' ranked him number 19 in its list of th ...

's novel ''Atonement

Atonement (also atoning, to atone) is the concept of a person taking action to correct previous wrongdoing on their part, either through direct action to undo the consequences of that act, equivalent action to do good for others, or some other ...

''. The principal character, eighteen-year-old Briony Tallis, sends the draft of a novella she has written to ''Horizon'' magazine and Cyril Connolly is shown as replying at length as to why the novella had to be rejected, apart from explaining to Briony her strong and weak points and also mentioning Elizabeth Bowen.

*Michael Lewis's book '' Moneyball: The Art of Winning an Unfair Game'' cites Connolly at the top of the first chapter – "Whom the gods wish to destroy they first call promising." (''Enemies of Promise'')

*Donna Tartt

Donna Louise Tartt (born December 23, 1963) is an American novelist and essayist.

Early life

Tartt was born in Greenwood, Mississippi, in the Mississippi Delta, the elder of two daughters. She was raised in the nearby town of Grenada. Her fa ...

's novel ''The Secret History

''The Secret History'' is the first novel by the American author Donna Tartt, published by Alfred A. Knopf in September 1992. Set in New England, the campus novel tells the story of a closely knit group of six classics students at Hampden Colleg ...

'' references Cyril Connolly in Chapter 5-"...Cyril Connolly, who was notorious for being a hard guest to please...".

*In William Boyd's James Bond novel ''Solo

Solo or SOLO may refer to:

Arts and entertainment Comics

* ''Solo'' (DC Comics), a DC comics series

* Solo, a 1996 mini-series from Dark Horse Comics

Characters

* Han Solo, a ''Star Wars'' character

* Jacen Solo, a Jedi in the non-canonical ''S ...

'' Bond recalls Connolly's description of Chelsea as "that tranquil cultivated ''spielraum''... where I worked and wandered" (Connolly, Boyd and the fictional Bond all lived in Chelsea), although Bond can not remember the author of the quote.

*In ''An Englishman Abroad

''An Englishman Abroad'' is a 1983 BBC television drama film based on the true story of a chance meeting of actress Coral Browne with Guy Burgess, a member of the Cambridge spy ring who spied for the Soviet Union while an officer at MI6. The pr ...

'' (1983) by Alan Bennett

Alan Bennett (born 9 May 1934) is an English actor, author, playwright and screenwriter. Over his distinguished entertainment career he has received numerous awards and honours including two BAFTA Awards, four Laurence Olivier Awards, and two ...

, Guy Burgess keeps asking Coral Browne "How is Cyril Connolly?"

*In ''Solomon Gursky Was Here

''Solomon Gursky Was Here'' is a novel by Canadians, Canadian author Mordecai Richler first published by Viking Canada in 1989 in literature, 1989.

Summary

The novel tells of several generations of the fictional Gursky family, who are connected t ...

'' (1989) by Mordecai Richler

Mordecai Richler (January 27, 1931 – July 3, 2001) was a Canadian writer. His best known works are '' The Apprenticeship of Duddy Kravitz'' (1959) and '' Barney's Version'' (1997). His 1970 novel '' St. Urbain's Horseman'' and 1989 novel ...

, Moses Berger, sorting his books as an excuse for not writing, finds his copy of ''The Unquiet Grave'' and reads "...the true function of a writer is to produce a masterpiece..." Muttering an imprecation, he throws the book across the room, but immediately retrieves it because of his regard for Connolly.

*Connolly makes an appearance as the 1940's editor of "Horizon" in Ian McEwan's 2022 novel, "Lessons".

Works

* ''The Rock Pool

''The Rock Pool'' is a novel written by Cyril Connolly, first published in 1936. It is Connolly's only novel and is set at the end of season in a small resort in the south of France. Connolly's main character, Naylor, starts with a study of the ...

'', 1935 (novel)

* '' Enemies of Promise'', 1938

* ''The Unquiet Grave

"The Unquiet Grave" is an English folk song in which a young man's grief over the death of his true love is so deep that it disturbs her eternal sleep. It was collected in 1868 by Francis James Child as Child Ballad number 78. One of the more comm ...

'', 1944

* ''The Condemned Playground'', 1945 (collection)

* ''The Missing Diplomats'', 1952

* ''The Golden Horizon'', 1953 (editor; compilation from ''Horizon'')

* ''Ideas and Places'', 1953 (collection)

* ''Les Pavillons: French Pavilions of the Eighteenth Century'', 1962 (with Jerome Zerbe

Jerome Zerbe (July 24, 1904, Euclid, Ohio – August 19, 1988) was an American photographer. He was one of the originators of a genre of photography that is now common: celebrity paparazzi. Zerbe was a pioneer in the 1930s of shooting photograph ...

)

* ''Previous Convictions'', 1963 (collection)

* ''The Modern Movement: 100 Key Books From England, France, and America, 1880–1950'', 1965

* '' The Evening Colonnade'' 1973 (collection)

* ''A Romantic Friendship'', 1975 (letters to Noel Blakiston)

* ''Cyril Connolly: Journal and Memoir'', 1983 (edited by D. Pryce-Jones)

* ''The Selected Essays of Cyril Connolly'', 1984 (edited by Peter Quennell)

* ''Shade Those Laurels,'' 1990 (fiction, completed by Peter Levi)

* ''The Selected Works of Cyril Connolly'', 2002 (edited by Matthew Connolly), Volume One: ''The Modern Movement''; Volume Two: ''The Two Natures''

Notes

References

* Clive Fisher (1995): ''Cyril Connolly'', New York: St Martin's Press, * Jeremy Lewis (1995): ''Cyril Connolly, A Life'', London: Jonathan Cape,External links

Bibliography and critical checklist

*

''Guardian'' profile of Connolly

by

William Boyd (writer)

William Andrew Murray Boyd (born 7 March 1952) is a Scottish novelist, short story writer and screenwriter.

Biography

Boyd was born in Accra, Gold Coast, (present-day Ghana), to Scottish parents, both from Fife, and has two younger sisters ...

*

{{DEFAULTSORT:Connolly, Cyril

1903 births

1974 deaths

20th-century English novelists

English literary critics

English male novelists

People educated at Eton College

People educated at St Cyprian's School

Alumni of Balliol College, Oxford

Commanders of the Order of the British Empire

Recipients of the Legion of Honour

People from Coventry

British special constables

20th-century English male writers

English male non-fiction writers

New Statesman people