Curtiss Model H on:

[Wikipedia]

[Google]

[Amazon]

The Curtiss Model H was a family of classes of early long-range

When London's ''

When London's '' Named ''America'' and launched 22 June 1914, trials began the following day and soon revealed a serious shortcoming in the design: the tendency for the nose of the aircraft to try to submerge as engine power increased while

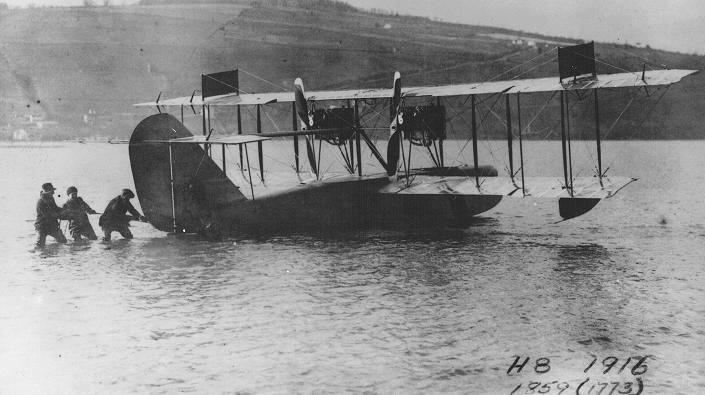

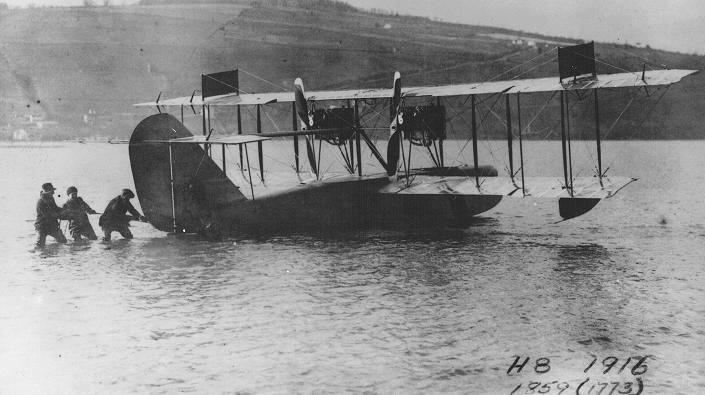

Named ''America'' and launched 22 June 1914, trials began the following day and soon revealed a serious shortcoming in the design: the tendency for the nose of the aircraft to try to submerge as engine power increased while  Curtiss next developed an enlarged version of the same design, designated the Model H-8, with accommodation for four crew members. A

Curtiss next developed an enlarged version of the same design, designated the Model H-8, with accommodation for four crew members. A  As built, the Model H-12s had 160 hp (118 kW)

As built, the Model H-12s had 160 hp (118 kW)

* Model H-1 or Model 6: original ''America'' intended for transatlantic crossing (two prototypes built)

* Model H-2 (one built)

* Model H-4: similar to H-1 for RNAS (62 built)

* Model H-7: ''Super America''

* Model H-8: enlarged version of the H-4 (one prototype built)

* Model H-12 or Model 6A: production version of H-8 with

* Model H-1 or Model 6: original ''America'' intended for transatlantic crossing (two prototypes built)

* Model H-2 (one built)

* Model H-4: similar to H-1 for RNAS (62 built)

* Model H-7: ''Super America''

* Model H-8: enlarged version of the H-4 (one prototype built)

* Model H-12 or Model 6A: production version of H-8 with

Sons of Our Empire

Film of the Royal Naval Air Service at Felixstowe, including

Reproduction ''America'' Flies, September 2008

Article featuring the Curtiss H-12 at

Flying Boats over the North Sea

Article including the Curtiss H-12.

Flying boats

over the

flying boat

A flying boat is a type of fixed-winged seaplane with a hull, allowing it to land on water. It differs from a floatplane in that a flying boat's fuselage is purpose-designed for floatation and contains a hull, while floatplanes rely on fuselag ...

s, the first two of which were developed directly on commission in the United States

The United States of America (U.S.A. or USA), commonly known as the United States (U.S. or US) or America, is a country Continental United States, primarily located in North America. It consists of 50 U.S. state, states, a Washington, D.C., ...

in response to the £10,000 prize challenge issued in 1913 by the London newspaper, the ''Daily Mail

The ''Daily Mail'' is a British daily middle-market tabloid newspaper and news websitePeter Wilb"Paul Dacre of the Daily Mail: The man who hates liberal Britain", ''New Statesman'', 19 December 2013 (online version: 2 January 2014) publish ...

'', for the first non-stop aerial crossing of the Atlantic. As the first aircraft having transatlantic range and cargo-carrying capacity, it became the grandfather development leading to early international commercial air travel, and by extension, to the modern world of commercial aviation. The last widely produced class, the Model H-12, was retrospectively designated Model 6 by Curtiss' company in the 1930s, and various classes have variants with suffixed letters indicating differences.

Design and development

Having transatlantic range and cargo carrying capacity by design, the first H-2 class (soon dubbed ''"The Americans"'' by theRoyal Navy

The Royal Navy (RN) is the United Kingdom's naval warfare force. Although warships were used by English and Scottish kings from the early medieval period, the first major maritime engagements were fought in the Hundred Years' War against Fr ...

) was quickly drafted into wartime use as a patrol and rescue aircraft by the RNAS, the air arm of the British Royal Navy. The original two "contest" aircraft were in fact temporarily seized by the Royal Navy, which later paid for them and placed an initial follow-on order for an additional 12 – all 14 of which were militarized (e.g. by adding gun mounts) and designated the "H-4" (the two originals were thereafter the "H-2" Models to air historians). These changes were produced under contract from Curtiss' factory in the last order of 50 "H-4s", giving a class total of 64, before the evolution of a succession of larger, more adaptable, and more robust H-class models. This article covers the whole line of nearly 500 Curtiss Model H seaplane

A seaplane is a powered fixed-wing aircraft capable of taking off and landing (alighting) on water.Gunston, "The Cambridge Aerospace Dictionary", 2009. Seaplanes are usually divided into two categories based on their technological characteri ...

flying boat

A flying boat is a type of fixed-winged seaplane with a hull, allowing it to land on water. It differs from a floatplane in that a flying boat's fuselage is purpose-designed for floatation and contains a hull, while floatplanes rely on fuselag ...

aircraft known to have been produced, since successive models – by whatever sub-model designation – were physically similar, handled similarly, essentially just being increased in size and fitted with larger and improved engines – the advances in internal combustion engine

An internal combustion engine (ICE or IC engine) is a heat engine in which the combustion of a fuel occurs with an oxidizer (usually air) in a combustion chamber that is an integral part of the working fluid flow circuit. In an internal co ...

technology in the 1910s being as rapid and explosive as any technological advance has ever been.

When London's ''

When London's ''Daily Mail

The ''Daily Mail'' is a British daily middle-market tabloid newspaper and news websitePeter Wilb"Paul Dacre of the Daily Mail: The man who hates liberal Britain", ''New Statesman'', 19 December 2013 (online version: 2 January 2014) publish ...

'' newspaper put up a £10,000 prize for the first non-stop aerial crossing of the Atlantic in 1913, American businessman Rodman Wanamaker

Lewis Rodman Wanamaker (February 13, 1863 – March 9, 1928) was an American businessman and heir to the Wanamaker's department store fortune. In addition to operating stores in Philadelphia, New York City, and Paris, he was a patron of the art ...

became determined that the prize should go to an American aircraft and commissioned the Curtiss Aeroplane and Motor Company

Curtiss Aeroplane and Motor Company (1909 – 1929) was an American aircraft manufacturer originally founded by Glenn Hammond Curtiss and Augustus Moore Herring in Hammondsport, New York. After significant commercial success in its first decade ...

to design and build an aircraft capable of making the flight. The ''Mail''s offer of a large monetary prize for "an aircraft with transoceanic range" (in an era with virtually no airports) galvanized air enthusiasts worldwide, and in America, prompted a collaboration between the American and British air pioneers: Glenn Curtiss

Glenn Hammond Curtiss (May 21, 1878 – July 23, 1930) was an American aviation and motorcycling pioneer, and a founder of the U.S. aircraft industry. He began his career as a bicycle racer and builder before moving on to motorcycles. As early a ...

and John Cyril Porte

Lieutenant Colonel John Cyril Porte, (26 February 1884 – 22 October 1919) was a British flying boat pioneer associated with the First World War Seaplane Experimental Station at Felixstowe.

Early life and career

Porte was born on 26 Februa ...

, spurred financially by the nationalistically motivated financing of air enthusiast Rodman Wanamaker

Lewis Rodman Wanamaker (February 13, 1863 – March 9, 1928) was an American businessman and heir to the Wanamaker's department store fortune. In addition to operating stores in Philadelphia, New York City, and Paris, he was a patron of the art ...

. The class, while commissioned by Wanamaker, was designed under Porte's supervision following his study and rearrangement of the flight plan and built in the Curtiss workshops. The outcome was a scaled-up version of Curtiss' work for the United States Navy and his Curtiss Model F

The Curtiss Models F made up a family of early flying boats developed in the United States in the years leading up to World War I. Widely produced, Model Fs saw service with the United States Navy under the designations C-2 through C-5, later ...

. With Porte also as Chief Test Pilot, development and testing of two prototypes proceeded rapidly, despite the inevitable surprises and teething troubles inherent in new engines, hull and fuselage.

The ''Wanamaker Flier'' was a conventional biplane

A biplane is a fixed-wing aircraft with two main wings stacked one above the other. The first powered, controlled aeroplane to fly, the Wright Flyer, used a biplane wing arrangement, as did many aircraft in the early years of aviation. While a ...

design with two-bay, unstaggered wings of unequal span with two tractor engines

An engine or motor is a machine designed to convert one or more forms of energy into mechanical energy.

Available energy sources include potential energy (e.g. energy of the Earth's gravitational field as exploited in hydroelectric power g ...

mounted side by side above the fuselage

The fuselage (; from the French ''fuselé'' "spindle-shaped") is an aircraft's main body section. It holds crew, passengers, or cargo. In single-engine aircraft, it will usually contain an engine as well, although in some amphibious aircraft t ...

in the interplane gap. Wingtip pontoons were attached directly below the lower wings near their tips. The aircraft resembled Curtiss' earlier flying boat designs, but was considerably larger in order to carry enough fuel to cover 1,100 mi (1,770 km). The three crew members were accommodated in a fully enclosed cabin.

Named ''America'' and launched 22 June 1914, trials began the following day and soon revealed a serious shortcoming in the design: the tendency for the nose of the aircraft to try to submerge as engine power increased while

Named ''America'' and launched 22 June 1914, trials began the following day and soon revealed a serious shortcoming in the design: the tendency for the nose of the aircraft to try to submerge as engine power increased while taxiing

Taxiing (rarely spelled taxying) is the movement of an aircraft on the ground, under its own power, in contrast to towing or pushback where the aircraft is moved by a tug. The aircraft usually moves on wheels, but the term also includes aircr ...

on water. This phenomenon had not been encountered before, since Curtiss' earlier designs had not used such powerful engines. In order to counteract this effect, Curtiss fitted fins

A fin is a thin component or appendage attached to a larger body or structure. Fins typically function as foils that produce lift or thrust, or provide the ability to steer or stabilize motion while traveling in water, air, or other fluids. Fin ...

to the sides of the bow to add hydrodynamic lift, but soon replaced these with sponson

Sponsons are projections extending from the sides of land vehicles, aircraft or watercraft to provide protection, stability, storage locations, mounting points for weapons or other devices, or equipment housing.

Watercraft

On watercraft, a spon ...

s to add more buoyancy. Both prototypes, once fitted with sponsons, were then called Model H-2s incrementally updated alternating in succession. These sponsons would remain a prominent feature of flying boat hull design in the decades to follow. With the problem resolved, preparations for the transatlantic crossing resumed, and 5 August 1914 was selected to take advantage of the full moon

The full moon is the lunar phase when the Moon appears fully illuminated from Earth's perspective. This occurs when Earth is located between the Sun and the Moon (when the ecliptic longitudes of the Sun and Moon differ by 180°). This mea ...

.

These plans were interrupted by the outbreak of the First World War

World War I (28 July 1914 11 November 1918), often abbreviated as WWI, was List of wars and anthropogenic disasters by death toll, one of the deadliest global conflicts in history. Belligerents included much of Europe, the Russian Empire, ...

, which also saw Porte, who was to pilot the ''America'' with George Hallett, recalled to service with the British Royal Navy

The Royal Navy (RN) is the United Kingdom's naval warfare force. Although warships were used by English and Scottish kings from the early medieval period, the first major maritime engagements were fought in the Hundred Years' War against Fr ...

. Impressed by the capabilities he had witnessed, Porte urged the Admiralty

Admiralty most often refers to:

*Admiralty, Hong Kong

*Admiralty (United Kingdom), military department in command of the Royal Navy from 1707 to 1964

*The rank of admiral

*Admiralty law

Admiralty can also refer to:

Buildings

* Admiralty, Traf ...

to commandeer (and later, purchase) the ''America'' and her sister aircraft from Curtiss. By the late summer of 1914 they were both successfully fully tested and shipped to England 30 September, aboard RMS ''Mauretania''. This was followed by a decision to order a further 12 similar aircraft, one Model H-2 and the remaining as Model H-4s, four examples of the latter actually being assembled in the UK by Saunders

Saunders is a surname of English and Scottish patronymic origin derived from Sander, a mediaeval form of Alexander.See also: Sander (name)

People

* Ab Saunders (1851–1883), American cowboy and gunman

* Al Saunders (born 1947), American foot ...

. All of these were essentially identical to the design of the ''America'', and indeed, were all referred to as "Americas" in Royal Navy service. This initial batch was followed by an order for another 50.

These aircraft were soon of great interest to the British Admiralty

The Admiralty was a department of the Government of the United Kingdom responsible for the command of the Royal Navy until 1964, historically under its titular head, the Lord High Admiral – one of the Great Officers of State. For much of i ...

as anti-submarine patrol craft and for air-sea rescue roles. The initial Royal Navy purchase of just two aircraft eventually spawned a fleet of aircraft which saw extensive military service during World War I in these roles, being extensively developed in the process (together with many spinoff or offspring variants) under the compressed research and development cycles available in wartime. Consequently, as the war progressed, the Model H was developed into progressively larger variants, and it served as the basis for parallel developments in the United Kingdom

The United Kingdom of Great Britain and Northern Ireland, commonly known as the United Kingdom (UK) or Britain, is a country in Europe, off the north-western coast of the continental mainland. It comprises England, Scotland, Wales and ...

under John Cyril Porte

Lieutenant Colonel John Cyril Porte, (26 February 1884 – 22 October 1919) was a British flying boat pioneer associated with the First World War Seaplane Experimental Station at Felixstowe.

Early life and career

Porte was born on 26 Februa ...

which led to the "Felixstowe" series of flying boats with their better hydrodynamic hull forms, beginning with the Felixstowe F.1

The Felixstowe F.1 was a British experimental flying boat designed and developed by Lieutenant Commander John Cyril Porte RN at the naval air station, Felixstowe based on the Curtiss H-4 with a new hull. Its design led to a range of successful ...

— a hull form which thereafter became the standard in seaplanes of all kinds, just as sponsons did for flying boats.

Curtiss next developed an enlarged version of the same design, designated the Model H-8, with accommodation for four crew members. A

Curtiss next developed an enlarged version of the same design, designated the Model H-8, with accommodation for four crew members. A prototype

A prototype is an early sample, model, or release of a product built to test a concept or process. It is a term used in a variety of contexts, including semantics, design, electronics, and software programming. A prototype is generally used to ...

was constructed and offered to the United States Navy

The United States Navy (USN) is the maritime service branch of the United States Armed Forces and one of the eight uniformed services of the United States. It is the largest and most powerful navy in the world, with the estimated tonnage ...

, but was ultimately also purchased by the British Admiralty. This aircraft would serve as the pattern for the Model H-12, used extensively by both the Royal Navy and the United States Navy. Upon their adoption into service by the RNAS, they became known as Large Americas, with the H-4s receiving the retronym

A retronym is a newer name for an existing thing that helps differentiate the original form/version from a more recent one. It is thus a word or phrase created to avoid confusion between older and newer types, whereas previously (before there were ...

Small America.

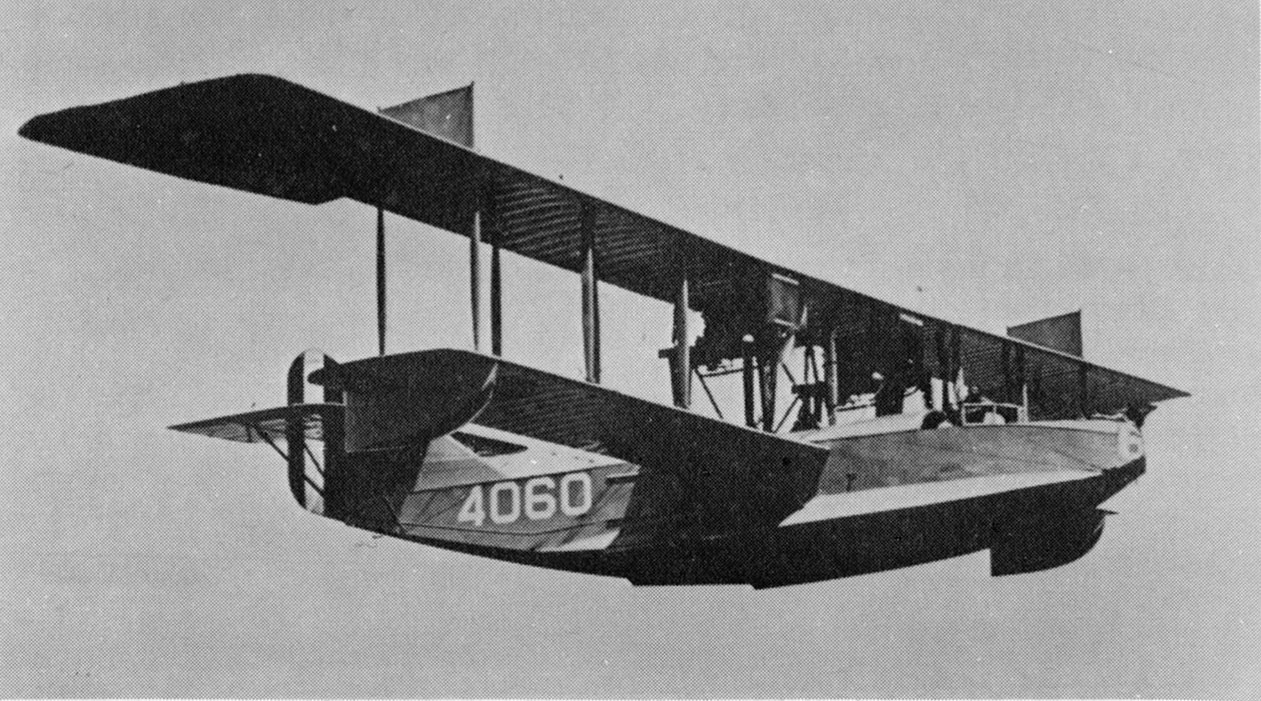

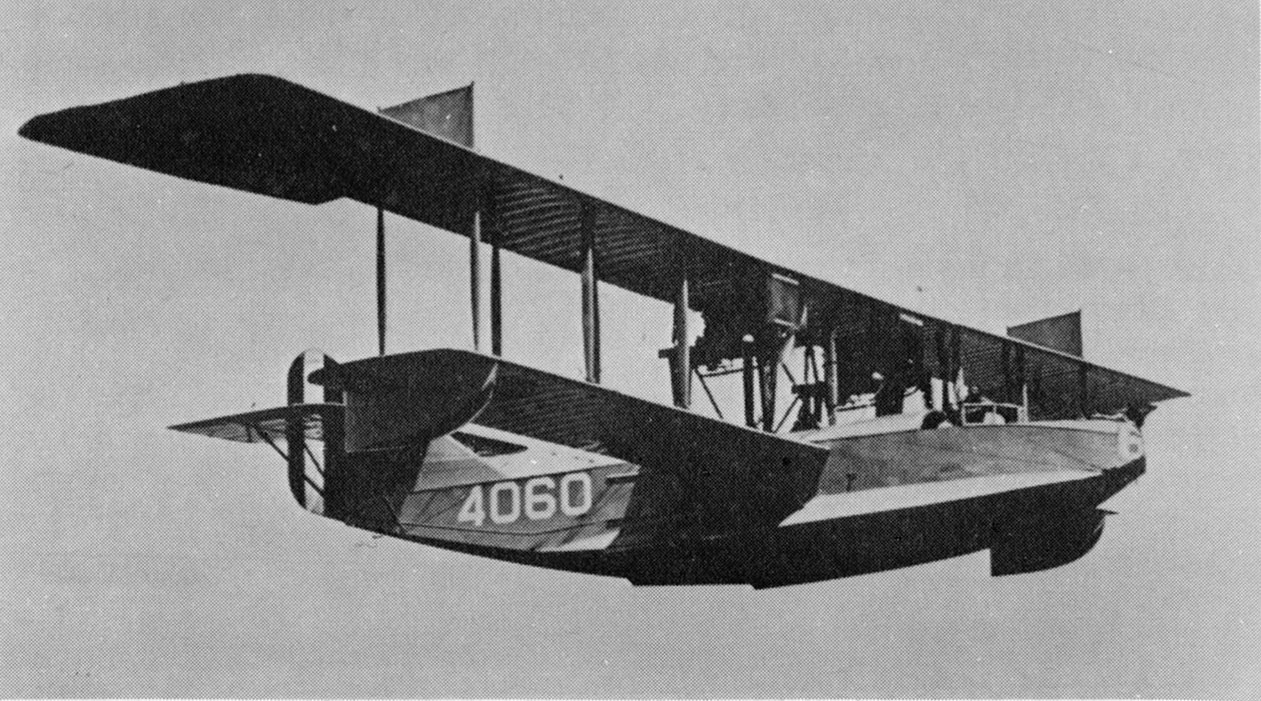

As built, the Model H-12s had 160 hp (118 kW)

As built, the Model H-12s had 160 hp (118 kW) Curtiss V-X-X

Curtiss Aeroplane and Motor Company (1909 – 1929) was an American aircraft manufacturer originally founded by Glenn Hammond Curtiss and Augustus Moore Herring in Hammondsport, New York. After significant commercial success in its first decade ...

engines, but these engines were under powered and deemed unsatisfactory by the British so in Royal Naval Air Service

The Royal Naval Air Service (RNAS) was the air arm of the Royal Navy, under the direction of the Admiralty's Air Department, and existed formally from 1 July 1914 to 1 April 1918, when it was merged with the British Army's Royal Flying Corps t ...

(RNAS) service the H-12 was re-engined with the 275 hp (205 kW) Rolls-Royce Eagle

The Rolls-Royce Eagle was the first aircraft engine to be developed by Rolls-Royce Limited. Introduced in 1915 to meet British military requirements during World War I, it was used to power the Handley Page Type O bombers and a number of oth ...

I and then the 375 hp (280 kW) Eagle VIII.Thetford 1978, pp. 80–81. Porte redesigned the H-12 with an improved hull; this design, the Felixstowe F.2

The Felixstowe F.2 was a 1917 British flying boat class designed and developed by Lieutenant Commander John Cyril Porte RN at the naval air station, Felixstowe during the First World War adapting a larger version of his superior Felixstowe F ...

, was produced and entered service. Some of the H-12s were later rebuilt with a hull similar to the F.2, these rebuilds being known as the Converted Large America. Later aircraft for the U.S. Navy received the Liberty engine

The Liberty L-12 is an American water-cooled 45° V-12 aircraft engine displacing and making designed for a high power-to-weight ratio and ease of mass production. It saw wide use in aero applications, and, once marinized, in marine use both ...

(designated Curtiss H-12L).Swanborough and Bowers 1976, pp. 106–107.

Curiously, the Curtiss company designation Model H-14 was applied to a completely unrelated design (see Curtiss HS

The Curtiss HS was a single-engined patrol flying boat built for the United States Navy during World War I. Large numbers were built from 1917 to 1919, with the type being used to carry out anti-submarine patrols from bases in France from June 1 ...

), but the Model H-16, introduced in 1917, represented the final step in the evolution of the Model H design.Swanborough and Bowers 1976, p. 107. With longer-span wings, and a reinforced hull similar to the Felixstowe flying boats, the H-16s were powered by Liberty engines in U.S. Navy service and by Eagle IVs for the Royal Navy. These aircraft remained in service through the end of World War I. Some were offered for sale as surplus military equipment at $11,053 apiece (one third of the original purchase price.)Van Wyen 1969, p. 90 Others remained in U.S. Navy service for some years after the war, most receiving engine upgrades to more powerful Liberty variants.

Operational history

With the RNAS, H-12s and H-16s operated from flying boat stations on the coast in long-range anti-submarine

A submarine (or sub) is a watercraft capable of independent operation underwater. It differs from a submersible, which has more limited underwater capability. The term is also sometimes used historically or colloquially to refer to remotely op ...

and anti-Zeppelin

A Zeppelin is a type of rigid airship named after the German inventor Count Ferdinand von Zeppelin () who pioneered rigid airship development at the beginning of the 20th century. Zeppelin's notions were first formulated in 1874Eckener 1938, pp ...

patrols over the North Sea

The North Sea lies between Great Britain, Norway, Denmark, Germany, the Netherlands and Belgium. An epeiric sea on the European continental shelf, it connects to the Atlantic Ocean through the English Channel in the south and the Norwegian ...

. A total of 71 H-12s and 75 H-16s were received by the RNAS, commencing patrols in April 1917, with 18 H-12s and 30 H-16s remaining in service in October 1918.Thetford 1978, pp. 82–83.

U.S. Navy H-12s were kept at home and did not see foreign service, but ran anti-submarine patrols from their own naval stations. Twenty aircraft were delivered to the U.S. Navy. Some of the H-16s, however, arrived at bases in the UK in time to see limited service just before the cessation of hostilities. Navy pilots disliked H-16 because, in the event of a crash landing, the large engines above and behind the cockpit were likely to break loose and continue forward striking the pilot.

Variants

* Model H-1 or Model 6: original ''America'' intended for transatlantic crossing (two prototypes built)

* Model H-2 (one built)

* Model H-4: similar to H-1 for RNAS (62 built)

* Model H-7: ''Super America''

* Model H-8: enlarged version of the H-4 (one prototype built)

* Model H-12 or Model 6A: production version of H-8 with

* Model H-1 or Model 6: original ''America'' intended for transatlantic crossing (two prototypes built)

* Model H-2 (one built)

* Model H-4: similar to H-1 for RNAS (62 built)

* Model H-7: ''Super America''

* Model H-8: enlarged version of the H-4 (one prototype built)

* Model H-12 or Model 6A: production version of H-8 with Curtiss V-X-X

Curtiss Aeroplane and Motor Company (1909 – 1929) was an American aircraft manufacturer originally founded by Glenn Hammond Curtiss and Augustus Moore Herring in Hammondsport, New York. After significant commercial success in its first decade ...

engines (104 built)

** Model H-12A or Model 6B: RNAS version re-engined with Rolls-Royce Eagle

The Rolls-Royce Eagle was the first aircraft engine to be developed by Rolls-Royce Limited. Introduced in 1915 to meet British military requirements during World War I, it was used to power the Handley Page Type O bombers and a number of oth ...

I

** Model H-12B or Model 6D: RNAS version re-engined with Rolls-Royce Eagle VIII

** Model H-12L: USN version re-engined with Liberty engine

* Model H-16 or Model 6C: enlarged version of H-12 (334 built by Curtiss and Naval Aircraft Factory

The Naval Aircraft Factory (NAF) was established by the United States Navy in 1918 in Philadelphia, Pennsylvania. It was created to help solve aircraft supply issues which faced the Navy Department upon the entry of the U.S. into World War I. ...

)

** Model H-16-1: Model 16 fitted with pusher engines (one built)

** Model H-16-2: Model 16 fitted with pusher engines and revised wing cellule (one built)

Operators

; *Brazilian Naval Aviation

Brazilian Naval Aviation ( pt, Aviação Naval Brasileira; AvN) is the air arm of the Brazilian Navy operating from ships and from shore installations.

History

The Brazilian Naval Aviation branch was organized in August 1916, after creation of ...

;

*Canadian Air Force

The Royal Canadian Air Force (RCAF; french: Aviation royale canadienne, ARC) is the air and space force of Canada. Its role is to "provide the Canadian Forces with relevant, responsive and effective airpower". The RCAF is one of three environm ...

– two former Royal Air Force H-16 ''Large Americas'' as an Imperial Gift

;

*Royal Netherlands Naval Air Service

The Netherlands Naval Aviation Service ( nl, Marineluchtvaartdienst, shortened to MLD) is the naval aviation branch of the Royal Netherlands Navy.

History

World War I

Although the MLD was formed in 1914, with the building of a seaplane base ...

– one Curtiss H-12 in service

;

*Royal Naval Air Service

The Royal Naval Air Service (RNAS) was the air arm of the Royal Navy, under the direction of the Admiralty's Air Department, and existed formally from 1 July 1914 to 1 April 1918, when it was merged with the British Army's Royal Flying Corps t ...

*Royal Air Force

The Royal Air Force (RAF) is the United Kingdom's air and space force. It was formed towards the end of the First World War on 1 April 1918, becoming the first independent air force in the world, by regrouping the Royal Flying Corps (RFC) an ...

** No. 228 Squadron RAF

** No. 234 Squadron RAF

**No. 240 Squadron RAF

No. 240 Squadron RAF was a Royal Air Force flying boat and seaplane squadron during World War I, World War II and up to 1959. It was then reformed as a strategic missile squadron, serving thus till 1963.

History

Formation and World War I

No ...

** No. 249 Squadron RAF

;

*United States Navy

The United States Navy (USN) is the maritime service branch of the United States Armed Forces and one of the eight uniformed services of the United States. It is the largest and most powerful navy in the world, with the estimated tonnage ...

*American Trans-Oceanic Company

American Trans-Oceanic Company was an airline based in the United States.

History

Rodman Wanamaker published a letter in 1916 stating the founding of the American Trans-Oceanic Company to capitalize on the 1914 effort to fly across the Atlant ...

Specifications (Model H-12A)

See also

*Sikorsky Ilya Muromets

The Sikorsky ''Ilya Muromets'' (russian: Сикорский Илья Муромец) (Sikorsky S-22, S-23, S-24, S-25, S-26 and S-27) were a class of Russian pre-World War I large four-engine commercial airliners and military heavy bombers used ...

* Charles M. Olmsted

Charles Morgan Olmsted (January 19, 1881 – 1948) was an American aeronautical engineer.

Aeronautics

Charles M. Olmsted held a Ph.D. in astrophysics and became an aeronautical engineer in the early 20th century.

When he was 14, he designed an ...

* British Anzani

* Tony Jannus

Notes

Bibliography

* * * Roseberry, C.R. ''Glenn Curtiss: Pioneer of Flight''. Garden City, NY: Doubleday & Company, 1972. . * Shulman, Seth. ''Unlocking the Sky: Glen Hammond Curtiss and the Race to Invent the Airplane''. New York:Harper Collins

HarperCollins Publishers LLC is one of the Big Five English-language publishing companies, alongside Penguin Random House, Simon & Schuster, Hachette, and Macmillan. The company is headquartered in New York City and is a subsidiary of News Corp ...

, 2002. .

* Ray Sturtivant and Gordon Page ''Royal Navy Aircraft Serials and Units 1911–1919'' Air-Britain Air-Britain, traditionally sub-titled "The International Association of Aviation Enthusiasts", is a non-profit aviation society founded in July 1948. As from 2015, it is constituted as a British charitable trust and book publisher.

History

Air-Brit ...

, 1992.

* Swanborough, Gordon and Peter M. Bowers. ''United States Navy Aircraft since 1911, Second edition''. London: Putnam, 1976. .

* Taylor, Michael J.H. ''Jane's Encyclopedia of Aviation''. London: Studio Editions, 1989, p. 281. .

* Thetford, Owen. ''British Naval Aircraft since 1912'', Fourth edition. London: Putnam, 1978. .

* ''World Aircraft Information Files: File 891, Sheet 44–45''. London: Bright Star Publishing, 2002.

*

External links

Sons of Our Empire

Film of the Royal Naval Air Service at Felixstowe, including

John Cyril Porte

Lieutenant Colonel John Cyril Porte, (26 February 1884 – 22 October 1919) was a British flying boat pioneer associated with the First World War Seaplane Experimental Station at Felixstowe.

Early life and career

Porte was born on 26 Februa ...

, Curtiss Model H-2 and prototype Felixstowe F.1

The Felixstowe F.1 was a British experimental flying boat designed and developed by Lieutenant Commander John Cyril Porte RN at the naval air station, Felixstowe based on the Curtiss H-4 with a new hull. Its design led to a range of successful ...

(No. 3580) fitted with Anzani

Anzani was an engine manufacturer founded by the Italian Alessandro Anzani (1877–1956), which produced proprietary engines for aircraft, cars, boats, and motorcycles in factories in Britain, France and Italy.

Overview

From his native Italy, An ...

engines, about August 1916.

* : Film of flying boats at RNAS Felixstowe

The Seaplane Experimental Station, formerly RNAS Felixstowe, was a British aircraft design unit during the early part of the 20th century.

Creation

During June 1912, surveys began for a suitable site for a base for Naval hydro-aeroplanes, with ...

, including an Anzani engined Curtiss H-4 taxiing, Felixstowe F.2A moved down a slipway on its beaching trolley and H-12 ''Large Americas'' being launched, one loaded with bombs, c.1917.

Reproduction ''America'' Flies, September 2008

Article featuring the Curtiss H-12 at

New Grimsby

New Grimsby ( kw, Enysgrymm Nowyth) is a coastal settlement on the island of Tresco in the Isles of Scilly, England. Ordnance Survey mapping It is located on the west side of the island and there is a quay, as well as a public house, ''The New ...

on the Scilly Isles

The Isles of Scilly (; kw, Syllan, ', or ) is an archipelago off the southwestern tip of Cornwall, England. One of the islands, St Agnes, is the most southerly point in Britain, being over further south than the most southerly point of the ...

.

Flying Boats over the North Sea

Article including the Curtiss H-12.

Flying boats

over the

Western Approaches

The Western Approaches is an approximately rectangular area of the Atlantic Ocean lying immediately to the west of Ireland and parts of Great Britain. Its north and south boundaries are defined by the corresponding extremities of Britain. The c ...

: Article including the Curtiss H-12.

{{Authority control

Model H

1910s United States experimental aircraft

Flying boats

Biplanes

Aircraft first flown in 1914

Twin piston-engined tractor aircraft