The Cuban Revolution ( es, Revolución Cubana) was carried out after the

1952 Cuban coup d'état which placed

Fulgencio Batista as head of state and the failed mass strike in opposition that followed. After failing to contest Batista in court,

Fidel Castro

Fidel Alejandro Castro Ruz (; ; 13 August 1926 – 25 November 2016) was a Cuban revolutionary and politician who was the leader of Cuba from 1959 to 2008, serving as the prime minister of Cuba from 1959 to 1976 and president from 1976 to 20 ...

organized an armed

attack on the Cuban military's Moncada Barracks. The rebels were arrested and while in prison formed the

26th of July Movement

The 26th of July Movement ( es, Movimiento 26 de Julio; M-26-7) was a Cuban vanguard revolutionary organization and later a political party led by Fidel Castro. The movement's name commemorates its 26 July 1953 attack on the army barracks on San ...

. After gaining amnesty the M-26-7 rebels organized an expedition from Mexico on the

Granma yacht to invade Cuba. In the following years the M-26-7 rebel army would slowly defeat the Cuban army in the countryside, while its urban wing would engage in sabotage and rebel army recruitment. Over time the originally critical and ambivalent

Popular Socialist Party would come to support the

26th of July Movement

The 26th of July Movement ( es, Movimiento 26 de Julio; M-26-7) was a Cuban vanguard revolutionary organization and later a political party led by Fidel Castro. The movement's name commemorates its 26 July 1953 attack on the army barracks on San ...

in late 1958. By the time the rebels were to oust Batista the revolution was being driven by the

Popular Socialist Party,

26th of July Movement

The 26th of July Movement ( es, Movimiento 26 de Julio; M-26-7) was a Cuban vanguard revolutionary organization and later a political party led by Fidel Castro. The movement's name commemorates its 26 July 1953 attack on the army barracks on San ...

, and the

Directorio Revolucionario Estudiantil.

The rebels finally ousted Batista on 31 December 1958, replacing his government. 26 July 1953 is celebrated in Cuba as (from

Spanish: "Day of the Revolution"). The 26th of July Movement later reformed along

Marxist–Leninist lines, becoming the

Communist Party of Cuba in October 1965.

The Cuban Revolution had powerful domestic and international repercussions. In particular, it transformed

Cuba–United States relations

Cuba and the United States restored diplomatic relations on July 20, 2015. Relations had been severed in 1961 during the Cold War. U.S. diplomatic representation in Cuba is handled by the United States Embassy in Havana, and there is a simila ...

, although efforts to improve diplomatic relations, such as the

Cuban thaw

The Cuban thaw ( es, Deshielo cubano) was the normalization of Cuba–United States relations that began in December 2014 ending a 54-year stretch of hostility between the nations. In March 2016, Barack Obama became the first U.S. president t ...

, gained momentum during the 2010s.

[ In the immediate aftermath of the revolution, Castro's government began a program of ]nationalization

Nationalization (nationalisation in British English) is the process of transforming privately-owned assets into public assets by bringing them under the public ownership of a national government or state. Nationalization usually refers to p ...

, centralization of the press and political consolidation that transformed Cuba's economy and civil society.[Lazo, Mario (1970). ''American Policy Failures in Cuba – Dagger in the Heart''. Twin Circle Publishing Co.: New York. pp. 198–200, 204. Library of Congress Card Catalog Number: 68-31632.][ The revolution also heralded an era of ]Cuban medical internationalism

After the 1959 Cuban Revolution, Cuba established a program to send its medical personnel overseas, particularly to Latin America, Africa

Africa is the world's second-largest and second-most populous continent, after Asia in both case ...

and Cuban intervention in foreign conflicts in Africa

Africa is the world's second-largest and second-most populous continent, after Asia in both cases. At about 30.3 million km2 (11.7 million square miles) including adjacent islands, it covers 6% of Earth's total surface area ...

, Latin America

Latin America or

* french: Amérique Latine, link=no

* ht, Amerik Latin, link=no

* pt, América Latina, link=no, name=a, sometimes referred to as LatAm is a large cultural region in the Americas where Romance languages — languages derived ...

, Southeast Asia

Southeast Asia, also spelled South East Asia and South-East Asia, and also known as Southeastern Asia, South-eastern Asia or SEA, is the geographical south-eastern region of Asia, consisting of the regions that are situated south of mainland ...

, and the Middle East

The Middle East ( ar, الشرق الأوسط, ISO 233: ) is a geopolitical region commonly encompassing Arabian Peninsula, Arabia (including the Arabian Peninsula and Bahrain), Anatolia, Asia Minor (Asian part of Turkey except Hatay Pro ...

.[ Several rebellions occurred in the six years following 1959, mainly in the ]Escambray Mountains

The Escambray Mountains () are a mountain range in the central region of Cuba, in the provinces of Sancti Spíritus, Cienfuegos and Villa Clara.

Overview

The Escambray Mountains are located in the south-central region of the island, extending a ...

, which were defeated by the revolutionary government.

Background

Corruption in Cuba

The Republic of Cuba at the turn of the 20th century was largely characterized by a deeply ingrained tradition of corruption where political participation resulted in opportunities for elites to engage in wealth accumulation.Charles Edward Magoon

Charles Edward Magoon (December 5, 1861 – January 14, 1920) was an American lawyer, judge, diplomat, and administrator who is best remembered as a governor of the Panama Canal Zone; he also served as Minister to Panama at the same time. H ...

, an American diplomat, taking over the government until 1909. It has been debated whether Magoon's government condoned or in fact engaged in corrupt practices. Hugh Thomas suggests that while Magoon disapproved of corrupt practices, corruption still persisted under his administration and he undermined the autonomy of the judiciary and their court decisions. Cuba's subsequent president, José Miguel Gómez

José Miguel Gómez y Arias (6 July 1858 – 13 June 1921) was a Cuban politician and revolutionary who was one of the leaders of the rebel forces in the Cuban War of Independence. He later served as President of Cuba from 1909 to 1913.

Early ...

, was the first to become involved in pervasive corruption and government corruption scandals. These scandals involved bribes

Bribery is the offering, giving, receiving, or soliciting of any item of value to influence the actions of an official, or other person, in charge of a public or legal duty. With regard to governmental operations, essentially, bribery is "Corru ...

that were allegedly paid to Cuban officials and legislators under a contract to search the Havana harbour, as well as the payment of fees to government associates and high-level officials.nepotism

Nepotism is an advantage, privilege, or position that is granted to relatives and friends in an occupation or field. These fields may include but are not limited to, business, politics, academia, entertainment, sports, fitness, religion, an ...

as Zayas relied on friends and relatives to illegally gain greater access to wealth. Due to Zaya's previous policies, Gerardo Machado

Gerardo Machado y Morales (28 September 1869 – 29 March 1939) was a general of the Cuban War of Independence and President of Cuba from 1925 to 1933.

Machado entered the presidency with widespread popularity and support from the major polit ...

aimed to diminish corruption and improve the public sector's performance under his successive administration from 1925 to 1933. While he was successfully able to reduce the amounts of low level and petty corruption, grand corruption still largely persisted. Machado embarked on development projects that enabled the persistence of grand corruption through inflated costs and the creation of "large margins" that enabled public officials to appropriate money illegally. Senator

Senator Eduardo Chibás

Eduardo René Chibás Ribas (August 15, 1907 – August 16, 1951) was a Cuban politician who used radio to broadcast his political views to the public. He primarily denounced corruption and gangsterism rampant during the governments of Ramón Gra ...

dedicated himself to exposing corruption in the Cuban government, and formed the Partido Ortodoxo

The Party of the Cuban People – Orthodox ( es, Partido del Pueblo Cubano – Ortodoxos, PPC-O), commonly shortened to the Orthodox Party ( es, Partido Ortodoxo), was a Cuban populist political party. It was founded in 1947 by Eduardo Chibás in ...

in 1947 to further this aim. Argote-Freyre points out that Cuba's population under the Republic had a high tolerance for corruption. Furthermore, Cubans knew and criticized who was corrupt, but admired them for their ability to act as "criminals with impunity".Ramón Grau

Ramón Grau San Martín (13 September 1881 in La Palma, Pinar del Río Province, Spanish Cuba – 28 July 1969 in Havana, Cuba) was a Cuban physician who served as President of Cuba from 1933 to 1934 and from 1944 to 1948. He was the last pre ...

and Carlos Prío Socarrás

Carlos Manuel Prío Socarrás (July 14, 1903 – April 5, 1977) was a Cuban politician. He served as the President of Cuba from 1948 until he was deposed by a military coup led by Fulgencio Batista on March 10, 1952, three months before new e ...

. Prío was reported to have stolen over $90 million in public funds, which was equivalent to one fourth of the annual national budget.U.S. State Department

The United States Department of State (DOS), or State Department, is an executive department of the U.S. federal government responsible for the country's foreign policy and relations. Equivalent to the ministry of foreign affairs of other n ...

was "very worried" about corruption under President

President most commonly refers to:

*President (corporate title)

* President (education), a leader of a college or university

* President (government title)

President may also refer to:

Automobiles

* Nissan President, a 1966–2010 Japanese ...

Fulgencio Batista, describing the problem as "endemic" and exceeding "anything which had gone on previously". British diplomats believed that corruption was rooted within Cuba's most powerful institutions, with the highest individuals in government and military being heavily involved in gambling and the drug trade.Franklin Roosevelt

Franklin Delano Roosevelt (; ; January 30, 1882April 12, 1945), often referred to by his initials FDR, was an American politician and attorney who served as the 32nd president of the United States from 1933 until his death in 1945. As the ...

's offer to send experts to help reform the Cuban Civil Service.

Later in 1952, Batista led a military coup against Prío Socarras and ruled until 1959. Under his rule, Batista led a corrupt dictatorship

A dictatorship is a form of government which is characterized by a leader, or a group of leaders, which holds governmental powers with few to no limitations on them. The leader of a dictatorship is called a dictator. Politics in a dictatorship a ...

that involved close links with organized crime organizations and the reduction of civil freedoms of Cubans. This period resulted in Batista engaging in more "sophisticated practices of corruption" at both the administrative and civil society levels.censorship

Censorship is the suppression of speech, public communication, or other information. This may be done on the basis that such material is considered objectionable, harmful, sensitive, or "inconvenient". Censorship can be conducted by governments ...

of the press as well as media, and creating anti-communist campaigns that suppressed opposition with violence, torture and public executions. The former culture of toleration and acceptance towards corruption also dissolved with the dictatorship of Batista. For instance, one citizen wrote that "however corrupt Grau and Prío were, we elected them and therefore allowed them to steal from us. Batista robs us without our permission."

Batista regime

In the decades following the United States' invasion of Cuba in 1898, and formal independence from the U.S. on 20 May 1902, Cuba experienced a period of significant instability, enduring a number of revolts, coups and a period of U.S. military occupation. Fulgencio Batista, a former soldier who had served as the elected president of Cuba from 1940 to 1944, became president for the second time in 1952, after seizing power in a military coup and canceling the 1952 elections. Although Batista had been relatively progressive during his first term,organized crime

Organized crime (or organised crime) is a category of transnational, national, or local groupings of highly centralized enterprises run by criminals to engage in illegal activity, most commonly for profit. While organized crime is generally th ...

and allowing American companies to dominate the Cuban economy, especially sugar-cane plantations and other local resources.anti-communist

Anti-communism is political and ideological opposition to communism. Organized anti-communism developed after the 1917 October Revolution in the Russian Empire, and it reached global dimensions during the Cold War, when the United States and the ...

.Fidel Castro

Fidel Alejandro Castro Ruz (; ; 13 August 1926 – 25 November 2016) was a Cuban revolutionary and politician who was the leader of Cuba from 1959 to 2008, serving as the prime minister of Cuba from 1959 to 1976 and president from 1976 to 20 ...

, then a young lawyer and activist, petitioned for the overthrow of Batista, whom he accused of corruption and tyranny. However, Castro's constitutional arguments were rejected by the Cuban courts. After deciding that the Cuban regime could not be replaced through legal means, Castro resolved to launch an armed revolution. To this end, he and his brother Raúl founded a paramilitary organization known as "The Movement", stockpiling weapons and recruiting around 1,200 followers from Havana's disgruntled working class by the end of 1952.

Early stages: 1953-1955

Attack on the Moncada Barracks

Striking their first blow against the Batista government, Fidel and Raúl Castro gathered 70 fighters and planned a multi-pronged attack on several military installations. On 26 July 1953, the rebels attacked the Moncada Barracks in

Striking their first blow against the Batista government, Fidel and Raúl Castro gathered 70 fighters and planned a multi-pronged attack on several military installations. On 26 July 1953, the rebels attacked the Moncada Barracks in Santiago

Santiago (, ; ), also known as Santiago de Chile, is the capital and largest city of Chile as well as one of the largest cities in the Americas. It is the center of Chile's most densely populated region, the Santiago Metropolitan Region, whos ...

and the barracks in Bayamo

Bayamo is the capital city of the Granma Province of Cuba and one of the largest cities in the Oriente region.

Overview

The community of Bayamo lies on a plain by the Bayamo River. It is affected by the violent Bayamo wind.

One of the mos ...

, only to be decisively defeated by the far more numerous government soldiers.

Imprisonment and immigration

Numerous key Movement revolutionaries, including the Castro brothers, were captured shortly afterwards. In a highly political trial, Fidel spoke for nearly four hours in his defense, ending with the words "Condemn me, it does not matter. History will absolve me." Castro's defense was based on nationalism, the representation and beneficial programs for the non-elite Cubans, and his patriotism and justice for the Cuban community.Jesuit

, image = Ihs-logo.svg

, image_size = 175px

, caption = ChristogramOfficial seal of the Jesuits

, abbreviation = SJ

, nickname = Jesuits

, formation =

, founders ...

childhood teachers succeeded in persuading Batista to include Fidel and Raúl in the release.Mexico

Mexico (Spanish language, Spanish: México), officially the United Mexican States, is a List of sovereign states, country in the southern portion of North America. It is borders of Mexico, bordered to the north by the United States; to the so ...

to prepare for the overthrow of Batista, receiving training from Alberto Bayo, a leader of Republican forces in the Spanish Civil War

The Spanish Civil War ( es, Guerra Civil Española)) or The Revolution ( es, La Revolución, link=no) among Nationalists, the Fourth Carlist War ( es, Cuarta Guerra Carlista, link=no) among Carlism, Carlists, and The Rebellion ( es, La Rebeli ...

. In June 1955, Fidel met the Argentine

Argentines (mistakenly translated Argentineans in the past; in Spanish (masculine) or (feminine)) are people identified with the country of Argentina. This connection may be residential, legal, historical or cultural. For most Argentines, ...

revolutionary Ernesto "Che" Guevara

Ernesto Che Guevara (; 14 June 1928The date of birth recorded on /upload.wikimedia.org/wikipedia/commons/7/78/Ernesto_Guevara_Acta_de_Nacimiento.jpg his birth certificatewas 14 June 1928, although one tertiary source, (Julia Constenla, quoted ...

, who joined his cause.[

]

Student demonstrations

By late 1955, student riots and demonstrations became more common, and unemployment became problematic as new graduates could not find jobs.[Samuel Shapiro (1963). ''Invisible Latin America''. Ayer Publishing. . p. 77.] Due to its continued opposition to the Cuban government and much protest activity taking place on its campus, the University of Havana

The University of Havana or (UH, ''Universidad de La Habana'') is a university located in the Vedado district of Havana, the capital of the Republic of Cuba. Founded on January 5, 1728, the university is the oldest in Cuba, and one of the firs ...

was temporarily closed on 30 November 1956 (it did not reopen until 1959 under the first revolutionary government).[Sterling, Carlos Márquez (1963). ''Historia de Cuba: Desde Colon hasta Castro''. Miami, Florida.]

Attack on the Domingo Goicuria Barracks

While the Castro brothers and the other 26 July Movement guerrillas were training in Mexico and preparing for their amphibious deployment to Cuba, another revolutionary group followed the example of the Moncada Barracks assault. On 29 April 1956 at 12:50 PM during Sunday mass, an independent guerrilla group of around 100 rebels led by Reynol Garcia attacked the Domingo Goicuria army barracks in Matanzas province. The attack was repelled with ten rebels and three soldiers killed in the fighting, and one rebel summarily executed by the garrison commander. Florida International University historian Miguel A. Brito was in the nearby cathedral when the firefight began. He writes, "That day, the Cuban Revolution began for me and Matanzas."

Insurgency: 1956-1957

Granma landing

The yacht '' Granma'' departed from Tuxpan

Tuxpan (or Túxpam, fully Túxpam de Rodríguez Cano) is both a municipality and city located in the Mexican state of Veracruz. The population of the city was 78,523 and of the municipality was 134,394 inhabitants, according to the INEGI censu ...

, Veracruz

Veracruz (), formally Veracruz de Ignacio de la Llave (), officially the Free and Sovereign State of Veracruz de Ignacio de la Llave ( es, Estado Libre y Soberano de Veracruz de Ignacio de la Llave), is one of the 31 states which, along with Me ...

, Mexico

Mexico (Spanish language, Spanish: México), officially the United Mexican States, is a List of sovereign states, country in the southern portion of North America. It is borders of Mexico, bordered to the north by the United States; to the so ...

, on 25 November 1956, carrying the Castro brothers and 80 others including Ernesto "Che" Guevara

Ernesto Che Guevara (; 14 June 1928The date of birth recorded on /upload.wikimedia.org/wikipedia/commons/7/78/Ernesto_Guevara_Acta_de_Nacimiento.jpg his birth certificatewas 14 June 1928, although one tertiary source, (Julia Constenla, quoted ...

and Camilo Cienfuegos

Camilo Cienfuegos Gorriarán (; 6 February 1932 – 28 October 1959) was a Cuban revolutionary born in Havana. Along with Che Guevara, Fidel Castro, Juan Almeida Bosque, and Raúl Castro, he was a member of the 1956 '' Granma'' expedition ...

, even though the yacht was only designed to accommodate 12 people with a maximum of 25. On 2 December, it landed in Playa Las Coloradas, in the municipality of Niquero, arriving two days later than planned because the boat was heavily loaded, unlike during the practice sailing runs. This dashed any hopes for a coordinated attack with the ''llano'' wing of the Movement. After arriving and exiting the ship, the band of rebels began to make their way into the Sierra Maestra mountains, a range in southeastern Cuba. Three days after the trek began, Batista's army attacked and killed most of the ''Granma'' participants – while the exact number is disputed, no more than twenty of the original eighty-two men survived the initial encounters with the Cuban army and escaped into the Sierra Maestra mountains.

The group of survivors included Fidel and Raúl Castro, Che Guevara and Camilo Cienfuegos

Camilo Cienfuegos Gorriarán (; 6 February 1932 – 28 October 1959) was a Cuban revolutionary born in Havana. Along with Che Guevara, Fidel Castro, Juan Almeida Bosque, and Raúl Castro, he was a member of the 1956 '' Granma'' expedition ...

. The dispersed survivors, alone or in small groups, wandered through the mountains, looking for each other. Eventually, the men would link up again – with the help of peasant sympathizers – and would form the core leadership of the guerrilla army. A number of female revolutionaries, including Celia Sanchez and Haydée Santamaría (the sister of Abel Santamaria), also assisted Fidel Castro's operations in the mountains.

Presidential palace attack

On 13 March 1957, a separate group of revolutionaries – the

On 13 March 1957, a separate group of revolutionaries – the anticommunist

Anti-communism is political and ideological opposition to communism. Organized anti-communism developed after the 1917 October Revolution in the Russian Empire, and it reached global dimensions during the Cold War, when the United States and the ...

Student Revolutionary Directorate (RD) ( ''Directorio Revolucionario Estudantil'', DRE), composed mostly of students – stormed the Presidential Palace in Havana, attempting to assassinate Batista and overthrow the government. The attack ended in utter failure. The RD's leader, student José Antonio Echeverría, died in a shootout with Batista's forces at the Havana radio station he had seized to spread the news of Batista's anticipated death. The handful of survivors included Dr. Humberto Castello (who later became the Inspector General in the Escambray), Rolando Cubela and Faure Chomon (both later Comandantes of the 13 March Movement, centered in the Escambray Mountains of Las Villas Province).

The plan, as explained by Faure Chaumón Mediavilla, was to attack the Presidential Palace and occupy the radio station Radio Reloj at the Radiocentro CMQ Building in order to announce the death of Batista and call for a general strike. The Presidential Palace was to be captured by fifty men under the direction of Carlos Gutiérrez Menoyo and Faure Chomón, with support from a group of 100 armed men occupying the tallest buildings in the surrounding area of the Presidential Palace (La Tabacalera, the Sevilla Hotel, the Palace of Fine Arts). However this secondary support operation was not carried out, as the men failed to arrive at the scene due to last-minute hesitation. Although the attackers reached the third floor of the Palace, they did not locate or execute Batista.

Humboldt 7 massacre

The Humboldt 7 massacre occurred on 20 April 1957 at apartment 201 when the National Police led by Lt. Colonel Esteban Ventura Novo assassinated four participants who had survived the assault on the Presidential Palace and in the seizure of the Radio Reloj station at the Radiocentro CMQ Building.

Juan Pedro Carbó was sought by police for the assassination of Col. Antonio Blanco Rico, Chief of Batista's secret service. Marcos Rodríguez Alfonso (also known as "Marquitos") began arguing with Fructuoso, Carbó and Machadito; Joe Westbrook had not yet arrived. Marquitos, who gave the airs to be a revolutionary, was strongly against the revolution and was thus resented by the others. On the morning of 20 April 1957, Marquitos met with Lt. Colonel Esteban Ventura and revealed the location of where the young revolutionaries were, Humboldt 7. After 5:00 PM on 20 April, a large contingent of police officers arrived and assaulted apartment 201, where the four men were staying. The men were not aware that the police were outside. The police rounded up and executed the rebels, who were unarmed.

The incident was covered up until a post-revolution investigation in 1959. Marquitos was arrested and, after a double trial, was sentenced by the Supreme Court to the penalty of death by firing squad in March 1964.

Frank País

Frank Pais was a revolutionary organizer who had built an extensive urban network, who had been tried and acquitted for his role in organizing an unsuccessful uprising in Santiago de Cuba in support of Castro's landing. On 30 June 1957, Frank's younger brother, Josué Pais, was killed by the Santiago police. During the latter part of July 1957, a wave of systematic police searches forced Frank País into hiding in Santiago de Cuba. On 30 July he was in a safe house with Raúl Pujol, despite warnings from other members of the Movement that it was not secure. The Santiago police under Colonel José Salas Cañizares surrounded the building. Frank and Raúl attempted to escape. However, an informant betrayed them as they tried to walk to a waiting getaway car. The police officers drove the two men to the Callejón del Muro (Rampart Lane) and shot them in the back of the head. In defiance of Batista's regime, he was buried in the Santa Ifigenia Cemetery in the olive green uniform and red and black armband of 26 July Movement.

In response to the death of País, the workers of Santiago declared a spontaneous general strike. This strike was the largest popular demonstration in the city up to that point. The mobilization of 30 July 1957 is considered one of the most decisive dates in both the Cuban Revolution and the fall of Batista's dictatorship. This day has been instituted in Cuba as the Day of the Martyrs of the Revolution. The Frank País Second Front, the guerrilla unit led by Raúl Castro in the Sierra Maestra was named for the fallen revolutionary. His childhood home at 226 San Bartolomé Street was turned into The Santiago Frank País García House Museum and designated as a national monument. The international airport in Holguín, Cuba also bears his name.

Naval mutiny at Cienfuegos

On 6 September 1957 elements of the Cuban navy in the Cienfuegos

Cienfuegos (), capital of Cienfuegos Province, is a city on the southern coast of Cuba. It is located about from Havana and has a population of 150,000. Since the late 1960s, Cienfuegos has become one of Cuba's main industrial centers, especia ...

Naval Base staged a rising against the Batista regime. Led by junior officers in sympathy with the 26th of July Movement

The 26th of July Movement ( es, Movimiento 26 de Julio; M-26-7) was a Cuban vanguard revolutionary organization and later a political party led by Fidel Castro. The movement's name commemorates its 26 July 1953 attack on the army barracks on San ...

, this was originally intended to coincide with the seizure of warships in Havana harbour. Reportedly individual officials within the U.S. Embassy were aware of the plot and had promised U.S. recognition if it were successful.

By 5:30am the base was in the hands of the mutineers. Most of the 150 naval personnel sleeping at the base joined with the twenty-eight original conspirators, while eighteen officers were arrested. About two hundred 26th of July Movement

The 26th of July Movement ( es, Movimiento 26 de Julio; M-26-7) was a Cuban vanguard revolutionary organization and later a political party led by Fidel Castro. The movement's name commemorates its 26 July 1953 attack on the army barracks on San ...

members and other rebel supporters entered the base from the town and were given weapons. Cienfuegos was in rebel hands for several hours.

By the afternoon Government motorised infantry had arrived from Santa Clara, supported by B-26 bombers. Armoured units followed from Havana. After street fighting throughout the afternoon and night the last of the rebels, holding out in the police headquarters, were overwhelmed. Approximately 70 mutineers and rebel supporters were executed and reprisals against civilians added to the estimated total death toll of 300 men.

The use of bombers and tanks recently provided under a US-Cuban arms agreement specifically for use in hemisphere defence, now raised tensions between the two governments.

Escalation and US involvement

The United States supplied Cuba with planes, ships, tanks, and other technology such as napalm

Napalm is an incendiary mixture of a gelling agent and a volatile petrochemical (usually gasoline (petrol) or diesel fuel). The name is a portmanteau of two of the constituents of the original thickening and gelling agents: coprecipitated alu ...

, which was used against the rebels. This would eventually come to an end due to a later arms embargo in 1958.

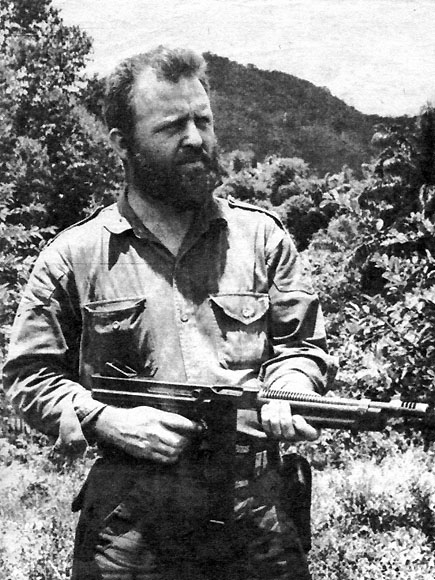

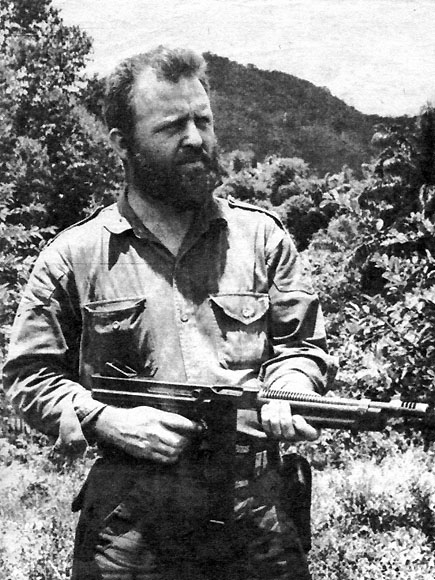

According to Tad Szulc, the United States began funding the 26th of July Movement around October or November 1957 and ending around middle 1958. "No less than $50,000" would be delivered to key leaders of the 26th of July Movement, While Batista increased troop deployments to the Sierra Maestra region to crush the 26 July guerrillas, the Second National Front of the Escambray kept battalions of the Constitutional Army tied up in the Escambray Mountains region. The Second National Front was led by former Revolutionary Directorate member Eloy Gutiérrez Menoyo and the "Comandante Yanqui" William Alexander Morgan. Gutiérrez Menoyo formed and headed the guerrilla band after news had broken out about Castro's landing in the Sierra Maestra, and José Antonio Echeverría had stormed the Havana Radio station. Though Morgan was dishonorably discharged from the U.S. Army, his recreating features from Army basic training made a critical difference in the Second National Front troops battle readiness.

Thereafter, the United States imposed an economic embargo on the Cuban government and recalled its ambassador, weakening the government's mandate further. Batista's support among Cubans began to fade, with former supporters either joining the revolutionaries or distancing themselves from Batista. Once Batista started making drastic decisions concerning Cuba's economy, he began to nationalize U.S oil refineries and other U.S properties. Nonetheless, the Mafia and U.S. businessmen maintained their support for the regime.

Batista's government often resorted to brutal methods to keep Cuba's cities under control. However, in the Sierra Maestra mountains, Castro, aided by Frank País, Ramos Latour, Huber Matos, and many others, staged successful attacks on small garrisons of Batista's troops. Castro was joined by CIA connected Frank Sturgis who offered to train Castro's troops in guerrilla warfare. Castro accepted the offer, but he also had an immediate need for guns and ammunition, so Sturgis became a gunrunner. Sturgis purchased boatloads of weapons and ammunition from CIA weapons expert Samuel Cummings' International Armament Corporation in Alexandria, Virginia. Sturgis opened a training camp in the Sierra Maestra mountains, where he taught Che Guevara and other 26 July Movement rebel soldiers guerrilla warfare.

In addition, poorly armed irregulars known as '' escopeteros'' harassed Batista's forces in the foothills and plains of

While Batista increased troop deployments to the Sierra Maestra region to crush the 26 July guerrillas, the Second National Front of the Escambray kept battalions of the Constitutional Army tied up in the Escambray Mountains region. The Second National Front was led by former Revolutionary Directorate member Eloy Gutiérrez Menoyo and the "Comandante Yanqui" William Alexander Morgan. Gutiérrez Menoyo formed and headed the guerrilla band after news had broken out about Castro's landing in the Sierra Maestra, and José Antonio Echeverría had stormed the Havana Radio station. Though Morgan was dishonorably discharged from the U.S. Army, his recreating features from Army basic training made a critical difference in the Second National Front troops battle readiness.

Thereafter, the United States imposed an economic embargo on the Cuban government and recalled its ambassador, weakening the government's mandate further. Batista's support among Cubans began to fade, with former supporters either joining the revolutionaries or distancing themselves from Batista. Once Batista started making drastic decisions concerning Cuba's economy, he began to nationalize U.S oil refineries and other U.S properties. Nonetheless, the Mafia and U.S. businessmen maintained their support for the regime.

Batista's government often resorted to brutal methods to keep Cuba's cities under control. However, in the Sierra Maestra mountains, Castro, aided by Frank País, Ramos Latour, Huber Matos, and many others, staged successful attacks on small garrisons of Batista's troops. Castro was joined by CIA connected Frank Sturgis who offered to train Castro's troops in guerrilla warfare. Castro accepted the offer, but he also had an immediate need for guns and ammunition, so Sturgis became a gunrunner. Sturgis purchased boatloads of weapons and ammunition from CIA weapons expert Samuel Cummings' International Armament Corporation in Alexandria, Virginia. Sturgis opened a training camp in the Sierra Maestra mountains, where he taught Che Guevara and other 26 July Movement rebel soldiers guerrilla warfare.

In addition, poorly armed irregulars known as '' escopeteros'' harassed Batista's forces in the foothills and plains of Oriente Province

Oriente (, "East") was the easternmost province of Cuba until 1976. The term "Oriente" is still used to refer to the eastern part of the country, which currently is divided into five different provinces. Fidel and Raúl Castro were born in a s ...

. The ''escopeteros'' also provided direct military support to Castro's main forces by protecting supply lines and by sharing intelligence. Ultimately, the mountains came under Castro's control.propaganda

Propaganda is communication that is primarily used to influence or persuade an audience to further an agenda, which may not be objective and may be selectively presenting facts to encourage a particular synthesis or perception, or using loaded ...

to their advantage. A pirate radio station called ''Radio Rebelde

Radio Rebelde (English: Rebel Radio) is a Cuban Spanish-language radio station. It broadcasts 24 hours a day with a varied program of national and international music hits of the moment, news reports and live sport events. The station was set up ...

'' ("Rebel Radio") was set up in February 1958, allowing Castro and his forces to broadcast their message nationwide within enemy territory. Castro's affiliation with the ''New York Times'' journalist Herbert Matthews

Herbert Lionel Matthews (January 10, 1900 – July 30, 1977) was a reporter and editorialist for '' The New York Times'' who, at the age of 57, won widespread attention after revealing that the 30-year-old Fidel Castro was still alive and living ...

created a front page-worthy report on anti-communist propaganda. The radio broadcasts were made possible by Carlos Franqui

Carlos Franqui (December 4, 1921 – April 16, 2010) was a Cuban writer, poet, journalist, art critic, and political activist. After the Fulgencio Batista coup in 1952, he became involved with the 26th of July Movement which was headed by Fide ...

, a previous acquaintance of Castro who subsequently became a Cuban exile in Puerto Rico

Puerto Rico (; abbreviated PR; tnq, Boriken, ''Borinquen''), officially the Commonwealth of Puerto Rico ( es, link=yes, Estado Libre Asociado de Puerto Rico, lit=Free Associated State of Puerto Rico), is a Caribbean island and unincorporated ...

.

During this time, Castro's forces remained quite small in numbers, sometimes fewer than 200 men, while the Cuban army and police force had a manpower of around 37,000. Even so, nearly every time the Cuban military fought against the revolutionaries, the army was forced to retreat. An arms embargo – imposed on the Cuban government by the United States on 14 March 1958 – contributed significantly to the weakness of Batista's forces. The Cuban air force rapidly deteriorated: it could not repair its airplanes without importing parts from the United States.

Final offensives: 1958-1959

Operation Verano

Batista finally responded to Castro's efforts with an attack on the mountains called Operation Verano

Operation Verano (, "Operation Summer") was the name given to the summer offensive in 1958 by the Batista government during the Cuban Revolution, known to the rebels as ''La Ofensiva''. The offensive was designed to crush Fidel Castro's revolut ...

(''Summer''), known to the rebels as ''la Ofensiva''. The army sent some 12,000 soldiers, half of them untrained recruits, into the mountains, along with his own brother Raul. In a series of small skirmishes, Castro's determined guerrillas defeated the Cuban army.[ In the ]Battle of La Plata

The Battle of La Plata ''(11-21 July 1958)'' was part of Operation Verano, the summer offensive of 1958 launched by the Batista government during the Cuban Revolution. The battle resulted from a complex plan created by Cuban General Cantillo to ...

, which lasted from 11 to 21 July 1958, Castro's forces defeated a 500-man battalion, capturing 240 men while losing just three of their own.

However, the tide nearly turned on 29 July 1958, when Batista's troops almost destroyed Castro's small army of some 300 men at the Battle of Las Mercedes

The Battle of Las Mercedes (29 July-8 August 1958) was the last battle which occurred during the course of Operation Verano, the summer offensive of 1958 launched by the Batista Government during the Cuban Revolution.

The battle was a trap, de ...

. With his forces pinned down by superior numbers, Castro asked for, and received, a temporary cease-fire on 1 August. Over the next seven days, while fruitless negotiations took place, Castro's forces gradually escaped from the trap. By 8 August, Castro's entire army had escaped back into the mountains, and Operation Verano had effectively ended in failure for the Batista government.[

]

Battle of Las Mercedes

The Battle of Las Mercedes (29 July-8 August 1958) was the last battle of Operation Verano. The battle was a trap, designed by Cuban General Eulogio Cantillo to lure Fidel Castro's guerrillas into a place where they could be surrounded and destroyed. The battle ended with a cease-fire which Castro proposed and which Cantillo accepted. During the cease-fire, Castro's forces escaped back into the hills. The battle, though technically a victory for the Cuban army, left the army dispirited and demoralized. Castro viewed the result as a victory and soon launched his own offensive.

Battalion 17 began its pull back on 29 July 1958. Castro sent a column of men under

Battalion 17 began its pull back on 29 July 1958. Castro sent a column of men under René Ramos Latour

René Ramos Latour (May 12, 1932 in Antilla, Cuba – 30 July 1958) was a commander under Fidel Castro during the Cuban Revolution. He was killed in combat against the Cuban army during the Battle of Las Mercedes

The Battle of Las Mercedes ...

to ambush the retreating soldiers. They attacked the advance guard and killed some 30 soldiers but then came under attack from previously undetected Cuban forces. Latour called for help and Castro came to the battle scene with his own column of men. Castro's column also came under fire from another group of Cuban soldiers that had secretly advanced up the road from the Estrada Palma Sugar Mill.

As the battle heated up, General Cantillo called up more forces from nearby towns and some 1,500 troops started heading towards the fighting. However, this force was halted by a column under Che Guevara's command. While some critics accuse Che for not coming to the aid of Latour, Major Bockman argues that Che's move here was the correct thing to do. Indeed, he called Che's tactical appreciation of the battle "brilliant".

By the end of July, Castro's troops were fully engaged and in danger of being wiped out by the vastly superior numbers of the Cuban army. He had lost 70 men, including René Latour, and both he and the remains of Latour's column were surrounded. The next day, Castro requested a cease-fire with General Cantillo, even offering to negotiate an end to the war. This offer was accepted by General Cantillo for reasons that remain unclear.

Batista sent a personal representative to negotiate with Castro on 2 August. The negotiations yielded no result but during the next six nights, Castro's troops managed to slip away unnoticed. On 8 August when the Cuban army resumed its attack, they found no one to fight.

Castro's remaining forces had escaped back into the mountains, and Operation Verano had effectively ended in failure for the Batista government.

Battle of Yaguajay

In 1958, Fidel Castro ordered his revolutionary army to go on the offensive against Batista's army. While Castro led one force against

In 1958, Fidel Castro ordered his revolutionary army to go on the offensive against Batista's army. While Castro led one force against Guisa

Guisa is a municipality and town in the Granma Province of Cuba. It is located south-east of Bayamo, the provincial capital.

Demographics

In 2003, the municipality of Guisa had a population of 50,923. With a total area of , it has a populatio ...

, Masó and other towns, another major offensive was directed at the capture of the city of Santa Clara, the capital of what was then Las Villas Province.

Three columns were sent against Santa Clara under the command of Che Guevara, Jaime Vega, and Camilo Cienfuegos

Camilo Cienfuegos Gorriarán (; 6 February 1932 – 28 October 1959) was a Cuban revolutionary born in Havana. Along with Che Guevara, Fidel Castro, Juan Almeida Bosque, and Raúl Castro, he was a member of the 1956 '' Granma'' expedition ...

. Vega's column was caught in an ambush and completely destroyed. Guevara's column took up positions around Santa Clara (near Fomento). Cienfuegos's column directly attacked a local army garrison at Yaguajay. Initially numbering just 60 men out of Castro's hardened core of 230, Cienfuegos's group had gained many recruits as it crossed the countryside towards Santa Clara, eventually reaching an estimated strength of 450 to 500 fighters.

The garrison consisted of some 250 men under the command of a Cuban captain of Chinese ancestry, Alfredo Abon Lee

Captain Alfredo Abón Lee (1927 – December 4, 2012) was a Cuban army officer of Chinese Cuban ancestry who was the commander of the garrison at Yaguajay Squadron and was sent to Las Villa, replacing Colonel Roger Rojas Lavernia, where he fou ...

. The attack seems to have started around 19 December.

Convinced that reinforcements would be sent from Santa Clara, Lee put up a determined defense of his post. The guerrillas repeatedly attempted to overpower Lee and his men, but failed each time. By 26 December Camilo Cienfuegos had become quite frustrated; it seemed that Lee could not be overpowered, nor could he be convinced to surrender. In desperation, Cienfuegos tried using a homemade tank against Lee's position. The "tank" was actually a large tractor encased in iron plates with attached makeshift flamethrowers on top. It, too, proved unsuccessful.

Finally, on 30 December Lee ran out of ammunition and was forced to surrender his force to the guerrillas.

Battle of Guisa

On the morning of 20 November 1958, a convoy of the Batista soldiers began its usual journey from Guisa. Shortly after leaving that town, located in the northern foothills of the Sierra Maestra, the rebels attacked the caravan.

Guisa was 12 kilometers from the Command Post of the Zone of Operations, located on the outskirts of the city of Bayamo. Nine days earlier, Fidel Castro had left the La Plata Command, beginning an unstoppable march east with his escort and a small group of combatants.

On 19 November, the rebels arrived in Santa Barbara. By that time, there were approximately 230 combatants. Fidel gathered his officers to organize the siege of Guisa, and ordered the placement of a mine on the Monjarás bridge, over the Cupeinicú river. That night the combatants made a camp in Hoyo de Pipa. In the early morning, they took the path that runs between the Heliografo hill and the Mateo Roblejo hill, where they occupied strategic positions. In the meeting on the 20th, the army lost a truck, a bus, and a jeep. Six were killed and 17 prisoners were taken, three of them wounded. At around 10:30 am, the military Command Post located in the Zone of Operations in Bayamo sent a reinforcement made up of Co. 32, plus a platoon from Co. L and another platoon from Co. 22. This force was unable to advance for the resistance of the rebels. Fidel ordered the mining of another bridge over a tributary of the Cupeinicú River. Hours later the army sent a platoon from Co. 82 and another platoon from Co. 93, supported by a T-17 tank.

Rebel offensive

On 21 August 1958, after the defeat of Batista's ''Ofensiva'', Castro's forces began their own offensive. In the Oriente province (in the area of the present-day provinces of Santiago de Cuba, Granma, Guantánamo and Holguín), Fidel Castro, Raúl Castro and Juan Almeida Bosque directed attacks on four fronts. Descending from the mountains with new weapons captured during the ''Ofensiva'' and smuggled in by plane, Castro's forces won a series of initial victories. Castro's major victory at

On 21 August 1958, after the defeat of Batista's ''Ofensiva'', Castro's forces began their own offensive. In the Oriente province (in the area of the present-day provinces of Santiago de Cuba, Granma, Guantánamo and Holguín), Fidel Castro, Raúl Castro and Juan Almeida Bosque directed attacks on four fronts. Descending from the mountains with new weapons captured during the ''Ofensiva'' and smuggled in by plane, Castro's forces won a series of initial victories. Castro's major victory at Guisa

Guisa is a municipality and town in the Granma Province of Cuba. It is located south-east of Bayamo, the provincial capital.

Demographics

In 2003, the municipality of Guisa had a population of 50,923. With a total area of , it has a populatio ...

, and the successful capture of several towns including Maffo, Contramaestre, and Central Oriente, brought the Cauto plains under his control.

Meanwhile, three rebel columns, under the command of Che Guevara, Camilo Cienfuegos

Camilo Cienfuegos Gorriarán (; 6 February 1932 – 28 October 1959) was a Cuban revolutionary born in Havana. Along with Che Guevara, Fidel Castro, Juan Almeida Bosque, and Raúl Castro, he was a member of the 1956 '' Granma'' expedition ...

and Jaime Vega, proceeded westward toward Santa Clara, the capital of Villa Clara Province. Batista's forces ambushed and destroyed Jaime Vega's column, but the surviving two columns reached the central provinces, where they joined forces with several other resistance groups not under the command of Castro. When Che Guevara's column passed through the province of Las Villas, and specifically through the Escambray Mountains

The Escambray Mountains () are a mountain range in the central region of Cuba, in the provinces of Sancti Spíritus, Cienfuegos and Villa Clara.

Overview

The Escambray Mountains are located in the south-central region of the island, extending a ...

– where the anticommunist Revolutionary Directorate forces (who became known as the 13 March Movement) had been fighting Batista's army for many months – friction developed between the two groups of rebels. Nonetheless, the combined rebel army continued the offensive, and Cienfuegos won a key victory in the Battle of Yaguajay

The Battle of Yaguajay (19 – 30 December 1958) was a decisive victory for the Cuban Revolutionaries over the soldiers of the Batista government near the city of Santa Clara in Cuba during the Cuban Revolution.

Background

In 1958, Fidel Castr ...

on 30 December 1958, earning him the nickname "The Hero of Yaguajay".

1958 Cuban general election

General elections were held in

General elections were held in Cuba

Cuba ( , ), officially the Republic of Cuba ( es, República de Cuba, links=no ), is an island country comprising the island of Cuba, as well as Isla de la Juventud and several minor archipelagos. Cuba is located where the northern Caribb ...

on 3 November 1958. The three major presidential candidates were Carlos Márquez Sterling

Dr. Carlos Márquez Sterling y Guiral (September 8, 1898 – May 3, 1991) was a Cuban lawyer, writer, politician and diplomat.

Political career

Born Carlos Guiral y Márquez Sterling on September 8, 1898, in Camagüey, Cuba, Márquez Sterling ...

of the Partido del Pueblo Libre, Ramón Grau

Ramón Grau San Martín (13 September 1881 in La Palma, Pinar del Río Province, Spanish Cuba – 28 July 1969 in Havana, Cuba) was a Cuban physician who served as President of Cuba from 1933 to 1934 and from 1944 to 1948. He was the last pre ...

of the Partido Auténtico

The Cuban Revolutionary Party – Authentic ( es, Partido Revolucionario Cubano – Auténtico, PRC-A), commonly called the Authentic Party ( es, Partido Auténtico, PA), was a political party in Cuba most active between 1933 and 1952. Although th ...

and Andrés Rivero Agüero of the Coalición Progresista Nacional. There was also a minor party candidate on the ballot, Alberto Salas Amaro for the Union Cubana party. Voter turnout was estimated at about 50% of eligible voters. Although Andrés Rivero Agüero won the presidential election with 70% of the vote, he was unable to take office due to the Cuban Revolution.

Rivero Agüero was due to be sworn in on 24 February 1959. In a conversation between him and the American ambassador Earl E. T. Smith

Earl Edward Tailer Smith (July 8, 1903 – February 15, 1991) was an American financier and diplomat, who served as ambassador to Cuba from 1957 to 1959 and mayor of Palm Beach 1971 to 1977.

Early life

Smith was born in Newport, Rhode Island ...

on 15 November 1958, he called Castro a "sick man" and stated it would be impossible to reach a settlement with him. Rivero Agüero also said that he planned to restore constitutional government and would convene a Constitutional Assembly after taking office.

This was the last competitive election in Cuba, the 1940 Constitution of Cuba, the Congress and the Senate of the Cuban Republic, were quickly dismantled shortly thereafter.

The rebels

Rebels may refer to:

* Participants in a rebellion

* Rebel groups, people who refuse obedience or order

* Rebels (American Revolution), patriots who rejected British rule in 1776

Film and television

* ''Rebels'' (film) or ''Rebelles'', a 2019 ...

had publicly called for an election boycott, issuing its Total War Manifesto on 12 March 1958, threatening to kill anyone that voted.

Battle of Santa Clara and Batista's flight

On 31 December 1958, the

On 31 December 1958, the Battle of Santa Clara

The Battle of Santa Clara was a series of events in late December 1958 that led to the capture of the Cuban city of Santa Clara by revolutionaries under the command of Che Guevara.

The battle was a decisive victory for the rebels fighting ag ...

took place in a scene of great confusion. The city of Santa Clara fell to the combined forces of Che Guevara, Cienfuegos, and Revolutionary Directorate (RD) rebels led by Comandantes Rolando Cubela, Juan ("El Mejicano") Abrahantes, and William Alexander Morgan. News of these defeats caused Batista to panic. He fled Cuba by air for the Dominican Republic

The Dominican Republic ( ; es, República Dominicana, ) is a country located on the island of Hispaniola in the Greater Antilles archipelago of the Caribbean region. It occupies the eastern five-eighths of the island, which it shares with ...

just hours later on 1 January 1959. Comandante William Alexander Morgan, leading RD rebel forces, continued fighting as Batista departed and had captured the city of Cienfuegos

Cienfuegos (), capital of Cienfuegos Province, is a city on the southern coast of Cuba. It is located about from Havana and has a population of 150,000. Since the late 1960s, Cienfuegos has become one of Cuba's main industrial centers, especia ...

by 2 January.

Cuban General Eulogio Cantillo entered Havana's Presidential Palace, proclaimed the Supreme Court

A supreme court is the highest court within the hierarchy of courts in most legal jurisdictions. Other descriptions for such courts include court of last resort, apex court, and high (or final) court of appeal. Broadly speaking, the decisions of ...

judge Carlos Piedra

Carlos Manuel Piedra y Piedra (or Carlos Modesto Piedra y Piedra) (1895–1988) was a Cuban politician who served as the Interim President of Cuba for a single day (January 2–3, 1959) during the transition of power between Fulgencio Batista and r ...

as the new president, and began appointing new members to Batista's old government.

Castro learned of Batista's flight in the morning and immediately started negotiations to take over Santiago de Cuba. On 2 January, the military commander in the city, Colonel Rubido, ordered his soldiers not to fight, and Castro's forces took over the city. The forces of Guevara and Cienfuegos entered Havana at about the same time. They had met no opposition on their journey from Santa Clara to Cuba's capital. Castro himself arrived in Havana on 8 January after a long victory march. His initial choice of president, Manuel Urrutia Lleó, took office on 3 January.

Aftermath

Presidency of Manuel Urrutia Lleó

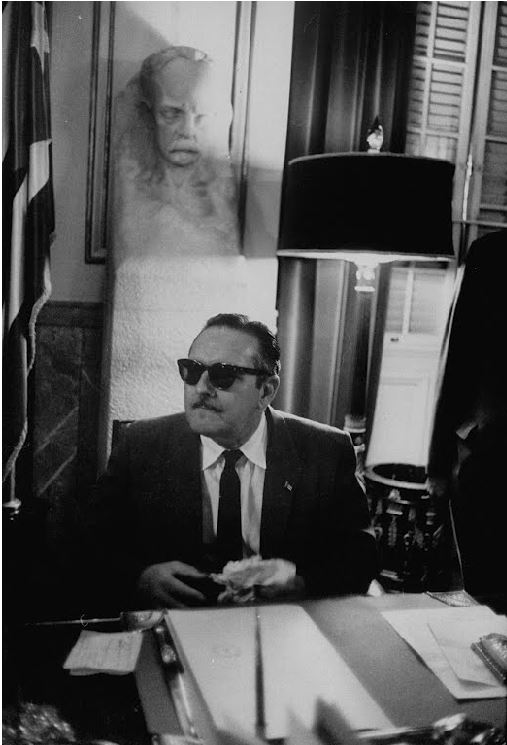

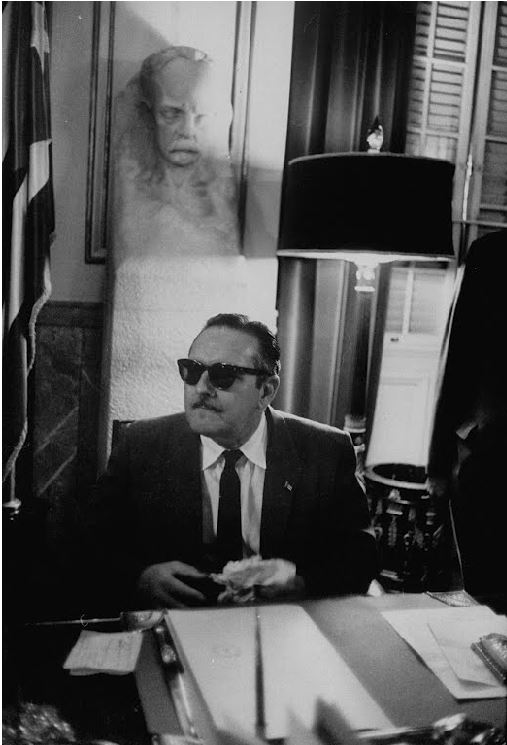

Manuel Urrutia Lleó (8 December 1901 – 5 July 1981) was a liberal Cuban lawyer and politician. He campaigned against the Gerardo Machado government and the second presidency of Fulgencio Batista during the 1950s, before serving as president in the first revolutionary government of 1959. Urrutia resigned his position after seven months, owing to a series of disputes with revolutionary leader Fidel Castro, and emigrated to the United States shortly afterward.

The Cuban Revolution gained victory on 1 January 1959, and Urrutia returned from exile in

Manuel Urrutia Lleó (8 December 1901 – 5 July 1981) was a liberal Cuban lawyer and politician. He campaigned against the Gerardo Machado government and the second presidency of Fulgencio Batista during the 1950s, before serving as president in the first revolutionary government of 1959. Urrutia resigned his position after seven months, owing to a series of disputes with revolutionary leader Fidel Castro, and emigrated to the United States shortly afterward.

The Cuban Revolution gained victory on 1 January 1959, and Urrutia returned from exile in Venezuela

Venezuela (; ), officially the Bolivarian Republic of Venezuela ( es, link=no, República Bolivariana de Venezuela), is a country on the northern coast of South America, consisting of a continental landmass and many islands and islets in th ...

to take up residence in the presidential palace. His new revolutionary government consisted largely of Cuban political veterans and pro-business liberals including José Miró, who was appointed as prime minister

A prime minister, premier or chief of cabinet is the head of the cabinet and the leader of the ministers in the executive branch of government, often in a parliamentary or semi-presidential system. Under those systems, a prime minister is ...

.[John Lee Anderson, ''Che Guevara : A revolutionary life''. 376–405.]

Once in power, Urrutia swiftly began a program of closing all brothel

A brothel, bordello, ranch, or whorehouse is a place where people engage in sexual activity with prostitutes. However, for legal or cultural reasons, establishments often describe themselves as massage parlors, bars, strip clubs, body rub p ...

s, gambling outlets and the national lottery

A lottery is a form of gambling that involves the drawing of numbers at random for a prize. Some governments outlaw lotteries, while others endorse it to the extent of organizing a national or state lottery. It is common to find some degree of ...

, arguing that these had long been a corrupting influence on the state. The measures drew immediate resistance from the large associated workforce. The disapproving Castro, then commander of Cuba's new armed forces, intervened to request a stay of execution until alternative employment could be found.

Disagreements also arose in the new government concerning pay cuts, which were imposed on all public officials on Castro's demand. The disputed cuts included a reduction of the $100,000 a year presidential salary Urrutia had inherited from Batista. By February, following the surprise resignation of Miró, Castro had assumed the role of prime minister; this strengthened his power and rendered Urrutia increasingly a figurehead president.[The Political End of President Urrutia](_blank)

Fidel Castro, by Robert E. Quirk 1993. Accessed 8 October 2006.

Urrutia was then accused by the ''Avance

Avance may refer to:

* Avance (Durance), a tributary of the Durance, France

* Avance (Garonne), a tributary of the Garonne, France

* Avance, South Dakota, a ghost town

* ''Avance'' (newspaper), a newspaper published in Nicaragua, the central ...

'' newspaper of buying a luxury villa, which was portrayed as a frivolous betrayal of the revolution and led to an outcry from the general public. He denied the allegation issuing a writ against the newspaper in response. The story further increased tensions between the various factions in the government, though Urrutia asserted publicly that he had "absolutely no disagreements" with Fidel Castro

Fidel Alejandro Castro Ruz (; ; 13 August 1926 – 25 November 2016) was a Cuban revolutionary and politician who was the leader of Cuba from 1959 to 2008, serving as the prime minister of Cuba from 1959 to 1976 and president from 1976 to 20 ...

. Urrutia attempted to distance the Cuban government (including Castro) from the growing influence of the communists within the administration, making a series of critical public comments against the latter group. Whilst Castro had not openly declared any affiliation with the Cuban communists, Urrutia had been a declared anti-communist

Anti-communism is political and ideological opposition to communism. Organized anti-communism developed after the 1917 October Revolution in the Russian Empire, and it reached global dimensions during the Cold War, when the United States and the ...

since they had refused to support the insurrection against Batista,[ Hugh Thomas, ''Cuba. The pursuit for freedom''. p830-832] stating in an interview, "If the Cuban people had heeded those words, we would still have Batista with us ... and all those other war criminals who are now running away".

Relations with the United States

The Cuban Revolution was a crucial turning point in U.S.-Cuban relations. Although the United States government was initially willing to recognize Castro's new government,

The Cuban Revolution was a crucial turning point in U.S.-Cuban relations. Although the United States government was initially willing to recognize Castro's new government,[Gleijeses, Piero (2002). ''Conflicting Missions: Havana, Washington and Africa, 1959–1976''. University of North Carolina Press. p. 14.] it soon came to fear that Communist insurgencies would spread through the nations of Latin America

Latin America or

* french: Amérique Latine, link=no

* ht, Amerik Latin, link=no

* pt, América Latina, link=no, name=a, sometimes referred to as LatAm is a large cultural region in the Americas where Romance languages — languages derived ...

, as they had in Southeast Asia

Southeast Asia, also spelled South East Asia and South-East Asia, and also known as Southeastern Asia, South-eastern Asia or SEA, is the geographical south-eastern region of Asia, consisting of the regions that are situated south of mainland ...

.[ After the revolutionary government nationalized all U.S. property in Cuba in August 1960, the American Eisenhower administration froze all Cuban assets on American soil, severed diplomatic ties and tightened its embargo of Cuba.]Bay of Pigs Invasion

The Bay of Pigs Invasion (, sometimes called ''Invasión de Playa Girón'' or ''Batalla de Playa Girón'' after the Playa Girón) was a failed military landing operation on the southwestern coast of Cuba in 1961 by Cuban exiles, covertly fin ...

, in which Brigade 2506 (a CIA-trained force of 1,500 soldiers, mostly Cuban exiles) landed on a mission to oust Castro; the attempt to overthrow Castro failed, with the invasion being repulsed by the Cuban military.[ The U.S. embargo against Cuba is still in force as of 2020, although it underwent a partial loosening during the Obama Administration, only to be strengthened in 2017 under Trump.][ The U.S. began efforts to normalize relations with Cuba in the mid-2010s,][ and formally reopened its embassy in Havana after over half a century in August 2015.]Cuban Thaw

The Cuban thaw ( es, Deshielo cubano) was the normalization of Cuba–United States relations that began in December 2014 ending a 54-year stretch of hostility between the nations. In March 2016, Barack Obama became the first U.S. president t ...

by severely restricting travel by US citizens to Cuba and tightening the US government's embargo against the country.

Relations with the Soviet Union

Following the American embargo, the Soviet Union became Cuba's main ally. The Soviets' attitude of optimism changed to one of concern for the safety of Cuba after it was excluded from the inter-American system at the conference held at Punta del Este in January 1962 by the Organization of American States.

The Soviets' attitude of optimism changed to one of concern for the safety of Cuba after it was excluded from the inter-American system at the conference held at Punta del Este in January 1962 by the Organization of American States.nuclear weapon

A nuclear weapon is an explosive device that derives its destructive force from nuclear reactions, either fission (fission bomb) or a combination of fission and fusion reactions ( thermonuclear bomb), producing a nuclear explosion. Both bomb ...

s in Cuba in 1962, an act which triggered the Cuban Missile Crisis

The Cuban Missile Crisis, also known as the October Crisis (of 1962) ( es, Crisis de Octubre) in Cuba, the Caribbean Crisis () in Russia, or the Missile Scare, was a 35-day (16 October – 20 November 1962) confrontation between the United S ...

in October 1962.

The aftermath of the Cuban Missile Crisis saw embarrassment for the Soviet Union, and many countries including Soviet countries were quick to criticize Moscow's handling of the situation. In a letter that Khrushchev writes to Castro in January of the following year (1963), after the end of conflict, he talks about wanting to discuss the issues in the two countries' relations. He writes attacking voices from other countries, including socialist ones, blaming the USSR of being opportunistic and self-serving. He explained the decision to withdraw missiles from Cuba, stressing the possibility of advancing Communism through peaceful means. Khrushchev underlined the importance of guaranteeing against an American attack on Cuba and urged Havana to focus on economic, cultural, and technological development to become a shining beacon of socialism in Latin America. In closing he invites Fidel Castro to visit Moscow and discuss the preparations for such a trip.

The following two decades in the 1970s and 1980s were somewhat of an enigma in the sense that the 1970s and 1980s were filled with the most prosperity in Cuba's history, yet the revolutionary government hit full stride in achieving its most organized form, and it adopted and enacted several brutal features of socialist regimes from the Eastern Bloc. Despite this it seems to be a time of prosperity. In 1972 Cuba joined COMECON, officially joining their trade with the Soviet Union's socialist trade bloc. That along with increased Soviet subsidies, better trade terms, and better, more practical domestic policy led to several years of prosperous growth. This period also sees Cuba strengthening its foreign policy with other communistic anti-US imperial countries like Nicaragua. This period is marked as the Sovietization of the 1970s and 1980s.

Cuba maintained close links to the Soviets until the Soviet Union's collapse

The dissolution of the Soviet Union, also negatively connoted as rus, Разва́л Сове́тского Сою́за, r=Razvál Sovétskogo Soyúza, ''Ruining of the Soviet Union''. was the process of internal disintegration within the Sov ...

in 1991. The end of Soviet economic aid and the loss of its trade partners in the Eastern Bloc led to an economic crisis and period of shortages known as the Special Period in Cuba.

Current day relations with Russia, formerly the Soviet Union, ended in 2002 after the Russian Federation closed an intelligence base in Cuba over budgetary concerns. However, in the last decade, relations have increased in recent years after Russia faced international backlash from the West over the situation in Ukraine in 2014. In retaliation for NATO expansion towards the east, Russia has sought to create these same agreements in Latin America. Russia has specifically sought greater ties with Cuba, Nicaragua, Venezuela, Brazil, and Mexico. Currently, these countries maintain close economic ties with the United States. In 2012, Putin decided that Russia focus its military power in Cuba like it had in the past. Putin is quoted saying "Our goal is to expand Russia's presence on the global arms and military equipment market. This means expanding the number of countries we sell to and expanding the range of goods and services we offer."

Global influence

Castro's victory and post-revolutionary foreign policy had global repercussions as influenced by the expansion of the Soviet Union

The Soviet Union,. officially the Union of Soviet Socialist Republics. (USSR),. was a transcontinental country that spanned much of Eurasia from 1922 to 1991. A flagship communist state, it was nominally a federal union of fifteen nationa ...

into Eastern Europe

Eastern Europe is a subregion of the European continent. As a largely ambiguous term, it has a wide range of geopolitical, geographical, ethnic, cultural, and socio-economic connotations. The vast majority of the region is covered by Russia, whi ...

after the 1917 October Revolution

The October Revolution,. officially known as the Great October Socialist Revolution. in the Soviet Union, also known as the Bolshevik Revolution, was a revolution in Russia led by the Bolshevik Party of Vladimir Lenin that was a key mom ...

. In line with his call for revolution in Latin America and beyond against imperial powers, laid out in his Declarations of Havana, Castro immediately sought to "export" his revolution to other countries in the Caribbean and beyond, sending weapons to Algeria

)

, image_map = Algeria (centered orthographic projection).svg

, map_caption =

, image_map2 =

, capital = Algiers

, coordinates =

, largest_city = capital

, relig ...

n rebels as early as 1960.Ghana

Ghana (; tw, Gaana, ee, Gana), officially the Republic of Ghana, is a country in West Africa. It abuts the Gulf of Guinea and the Atlantic Ocean to the south, sharing borders with Ivory Coast in the west, Burkina Faso in the north, and Tog ...

, Nicaragua

Nicaragua (; ), officially the Republic of Nicaragua (), is the largest country in Central America, bordered by Honduras to the north, the Caribbean to the east, Costa Rica to the south, and the Pacific Ocean to the west. Managua is the coun ...

, Yemen

Yemen (; ar, ٱلْيَمَن, al-Yaman), officially the Republic of Yemen,, ) is a country in Western Asia. It is situated on the southern end of the Arabian Peninsula, and borders Saudi Arabia to the north and Oman to the northeast and ...

, and Angola

, national_anthem = "Angola Avante"()

, image_map =

, map_caption =

, capital = Luanda

, religion =

, religion_year = 2020

, religion_ref =

, coordinat ...

, among others.[ Castro's intervention in the Angolan Civil War in the 1970s and 1980s was particularly significant, involving as many as 60,000 Cuban soldiers.]["La Guerras Secretas de Fidel Castro"](_blank)

(in Spanish). CubaMatinal.com. Retrieved 9 March 2013.

Characteristics

Ideology

At the time of the revolution various sectors of society supported the revolutionary movement from communists to business leaders and the Catholic Church.

At the time of the revolution various sectors of society supported the revolutionary movement from communists to business leaders and the Catholic Church.United States

The United States of America (U.S.A. or USA), commonly known as the United States (U.S. or US) or America, is a country Continental United States, primarily located in North America. It consists of 50 U.S. state, states, a Washington, D.C., ...

shortly after the revolution and him not joining the Cuban Communist Party during the beginning of his land reforms

Land reform is a form of agrarian reform involving the changing of laws, regulations, or customs regarding land ownership. Land reform may consist of a government-initiated or government-backed property redistribution, generally of agricultural ...

.26th of July Movement

The 26th of July Movement ( es, Movimiento 26 de Julio; M-26-7) was a Cuban vanguard revolutionary organization and later a political party led by Fidel Castro. The movement's name commemorates its 26 July 1953 attack on the army barracks on San ...

involved people of various political persuasions, but most were in agreement and desired the reinstatement of the 1940 Constitution of Cuba and supported the ideals of Jose Marti

Jose is the English transliteration of the Hebrew and Aramaic name ''Yose'', which is etymologically linked to ''Yosef'' or Joseph. The name was popular during the Mishnaic and Talmudic periods.

*Jose ben Abin

*Jose ben Akabya

*Jose the Gali ...

. Che Guevara

Ernesto Che Guevara (; 14 June 1928The date of birth recorded on /upload.wikimedia.org/wikipedia/commons/7/78/Ernesto_Guevara_Acta_de_Nacimiento.jpg his birth certificatewas 14 June 1928, although one tertiary source, (Julia Constenla, quoted ...

commented to Jorge Masetti in an interview during the revolution that "Fidel isn't a communist" also stating "politically you can define Fidel and his movement as 'revolutionary nationalist'. Of course he is anti-American, in the sense that Americans are anti-revolutionaries".

Women's roles

The importance of women's contributions to the Cuban Revolution is reflected in the very accomplishments that allowed the revolution to be successful, from the participation in the Moncada Barracks, to the Mariana Grajales all-women's platoon that served as Fidel Castro's personal security detail. Tete Puebla, second in command of the Mariana Grajales Women's Platoon, has said:

Before the Mariana Grajales Platoon was established, the revolutionary women of the Sierra Maestra were not organized for combat and primarily helped with cooking, mending clothes, and tending to the sick, frequently acting as couriers, as well as teaching guerrillas to read and write.

The importance of women's contributions to the Cuban Revolution is reflected in the very accomplishments that allowed the revolution to be successful, from the participation in the Moncada Barracks, to the Mariana Grajales all-women's platoon that served as Fidel Castro's personal security detail. Tete Puebla, second in command of the Mariana Grajales Women's Platoon, has said:

Before the Mariana Grajales Platoon was established, the revolutionary women of the Sierra Maestra were not organized for combat and primarily helped with cooking, mending clothes, and tending to the sick, frequently acting as couriers, as well as teaching guerrillas to read and write.

Related archival collections

There were many foreign presences in Cuba during this time. Esther Brinch was a Danish translator for the Danish government in 1960's Cuba. Brinch's work covered the Cuban Revolution and Cuban Missile Crisis.

George Mason University Special Collections Research Center.

See also

* Communist revolution

* Communism

Communism (from Latin la, communis, lit=common, universal, label=none) is a far-left sociopolitical, philosophical, and economic ideology and current within the socialist movement whose goal is the establishment of a communist society, ...

* Cuban thaw

The Cuban thaw ( es, Deshielo cubano) was the normalization of Cuba–United States relations that began in December 2014 ending a 54-year stretch of hostility between the nations. In March 2016, Barack Obama became the first U.S. president t ...

* History of Cuba

The history of Cuba is characterized by dependence on outside powers— Spain, the US, and the USSR. The island of Cuba was inhabited by various Amerindian cultures prior to the arrival of the Genoese explorer Christopher Columbus in 1492. ...

* Latin American wars of independence

* Corruption in Cuba

* Consolidation of the Cuban Revolution

* Foreign relations of Cuba

Cuba's foreign policy has been fluid throughout history depending on world events and other variables, including relations with the United States. Without massive Soviet subsidies and its primary trading partner, Cuba became increasingly isola ...

Notes

References

Bibliography

*

*

*

*

*

*

*

*

*

*

*

Further reading

* Thomas M. Leonard (1999). ''Castro and the Cuban Revolution''. Greenwood Press. .

* Julio García Luis (2008). ''Cuban Revolution Reader: A Documentary History of Key Moments in Fidel Castro's Revolution''. Ocean Press. .

* Samuel Farber (2012). ''Cuba Since the Revolution of 1959: A Critical Assessment''. Haymarket Books. .

* Joseph Hansen (1994). ''Dynamics of the Cuban Revolution: A Marxist Appreciation''. Pathfinder Press. .

* Julia E. Sweig (2004). ''Inside the Cuban Revolution: Fidel Castro and the Urban Underground''. Harvard University Press. .

* Thomas C. Wright (2000). ''Latin America in the Era of the Cuban Revolution''. Praeger Paperback. .

* Marifeli Perez-Stable (1998). ''The Cuban Revolution: Origins, Course, and Legacy''. Oxford University Press. .

* Geraldine Lievesley (2004). ''The Cuban Revolution: Past, Present and Future Perspectives''. Palgrave Macmillan. .

* Teo A. Babun (2005). ''The Cuban Revolution: Years of Promise''. University Press of Florida. .

* Antonio Rafael de la Cova (2007). ''The Moncada Attack: Birth of the Cuban Revolution''. University of South Carolina Press. .

* Samuel Farber (2006). ''The Origins of the Cuban Revolution Reconsidered''. The University of North Carolina Press. .

* Jules R. Benjamin (1992). ''The United States and the Origins of the Cuban Revolution''. Princeton University Press. .

* Comite central del Partido comunista de Cuba: Comisión de orientación revolucionaria (1972). ''Rencontre symbolique entre deux processus historiques 'i.e''., de Cuba et de Chile'. La Habana, Cuba: Éditions politiques.

* David M. Watry (2014). ''Diplomacy at the Brink: Eisenhower, Churchill, and Eden in the Cold War.'' Baton Rouge: Louisiana State University Press. .

* Dolgoff, Sam ''The Cuban Revolution, a Critical Perspective'

The Cuban Revolution Table of Contents

External links

* Fidel Castro. . ''The Nation'' via Internet Archive. 30 November 1957.

Latin American Studies Organization.

* Michael Voss

"Reliving Cuba's Revolution"

BBC. 29 December 2008.

World History Archives.

* Arthur Brice

CNN. 2009.

"1959–2009: Celebrating 50 years of the Cuban Revolution"

Cuba Solidarity Campaign.

* .

* Rodríguez, Silvio.

Silvio Rodríguez Sings of the Special Period

" In ''The Cuba Reader: History, Culture, Politics'', 521–524.

* Rionda, Salvador.

Sugar Mills and Soviets

" In ''The Cuba Reader: History, Culture, Politics'', 259–260.

*Shutterbulky.

Cuban Revolution – Completely Analytical Digest

shutterbulky web article: 22 July 2021

{{Authority control

Revolution

In political science, a revolution (Latin: ''revolutio'', "a turn around") is a fundamental and relatively sudden change in political power and political organization which occurs when the population revolts against the government, typically due ...

Revolution