Crimes against humanity under communist regimes on:

[Wikipedia]

[Google]

[Amazon]

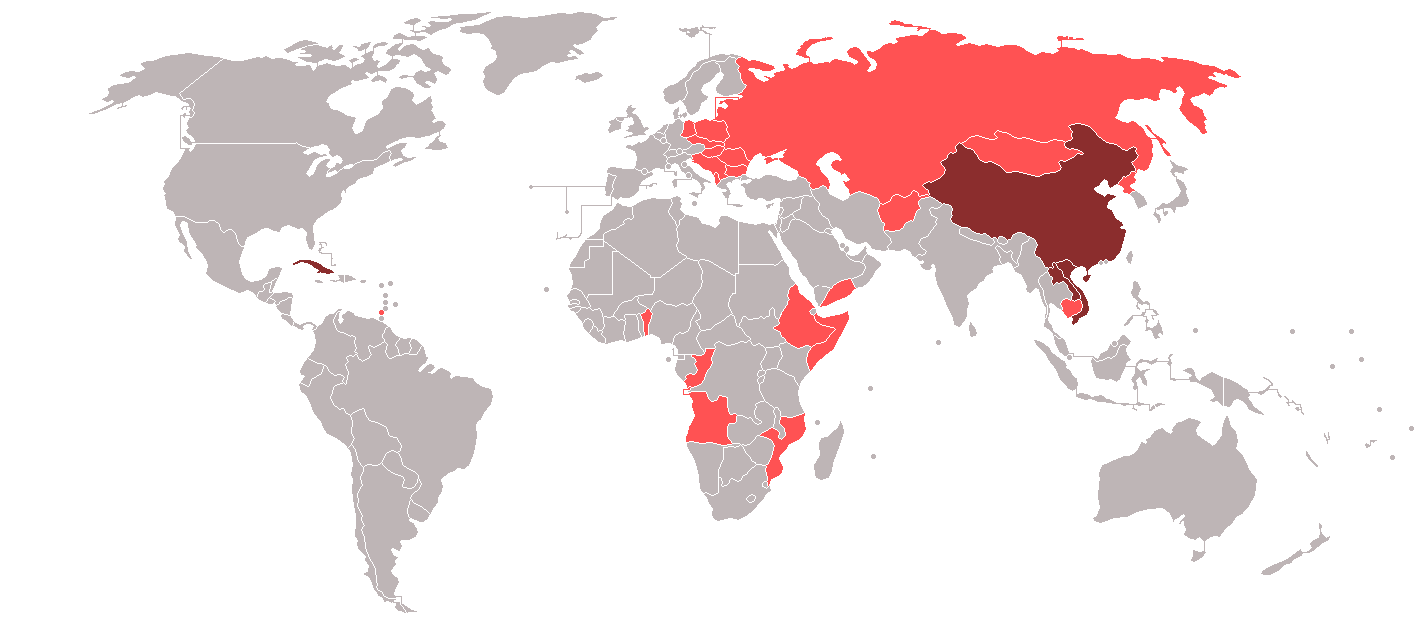

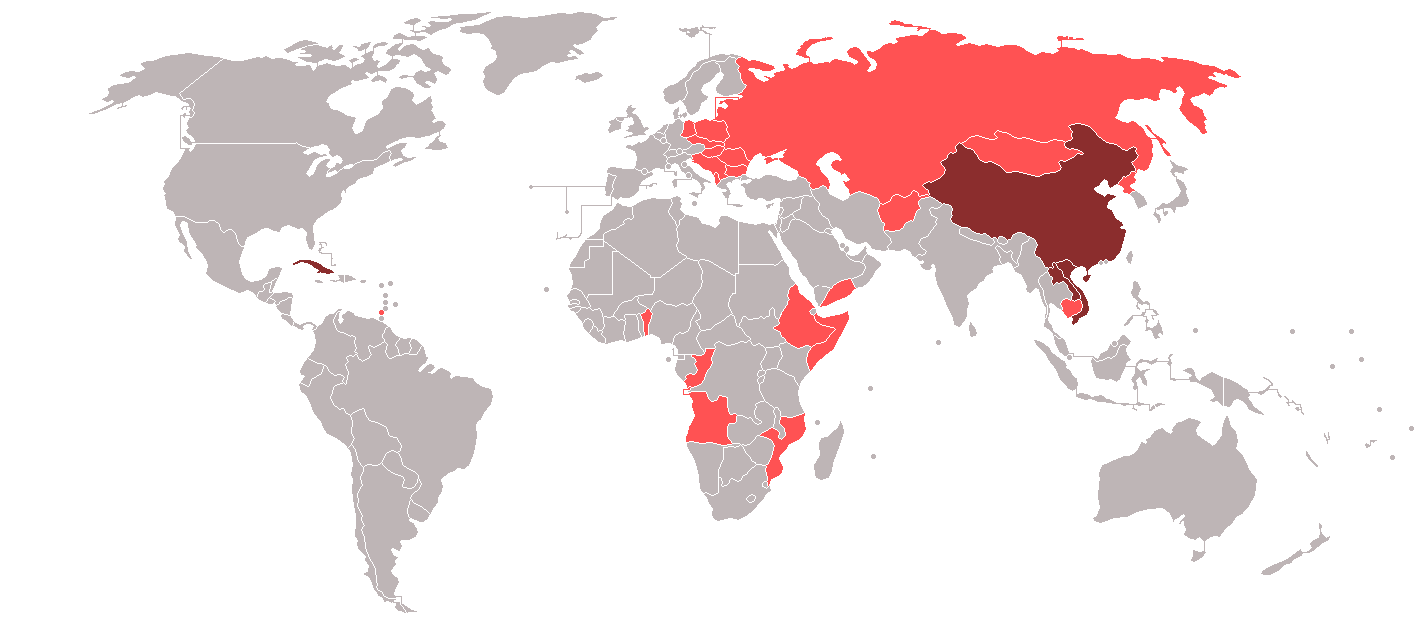

Crimes against humanity under communist regimes occurred during the 20th century, including forced deportations,

Crimes against humanity under communist regimes occurred during the 20th century, including forced deportations,

There is a scholarly consensus that the

There is a scholarly consensus that the

Following the overthrow of Ethiopian emperor

Following the overthrow of Ethiopian emperor

BBC, 22 December 1999 Derg chairman

Crimes against humanity under communist regimes occurred during the 20th century, including forced deportations,

Crimes against humanity under communist regimes occurred during the 20th century, including forced deportations, massacre

A massacre is the killing of a large number of people or animals, especially those who are not involved in any fighting or have no way of defending themselves. A massacre is generally considered to be morally unacceptable, especially when per ...

s, torture

Torture is the deliberate infliction of severe pain or suffering on a person for reasons such as punishment, extracting a confession, interrogation for information, or intimidating third parties. Some definitions are restricted to acts ...

, forced disappearance

An enforced disappearance (or forced disappearance) is the secret abduction or imprisonment of a person by a state or political organization, or by a third party with the authorization, support, or acquiescence of a state or political organi ...

s, extrajudicial killing

An extrajudicial killing (also known as extrajudicial execution or extralegal killing) is the deliberate killing of a person without the lawful authority granted by a judicial proceeding. It typically refers to government authorities, whethe ...

s, terror,Kemp-Welch, p. 42. ethnic cleansing

Ethnic cleansing is the systematic forced removal of ethnic, racial, and religious groups from a given area, with the intent of making a region ethnically homogeneous. Along with direct removal, extermination, deportation or population transfer ...

, enslavement and the deliberate starvation

Starvation is a severe deficiency in caloric energy intake, below the level needed to maintain an organism's life. It is the most extreme form of malnutrition. In humans, prolonged starvation can cause permanent organ damage and eventually, de ...

of people i.e. during the Holodomor

The Holodomor ( uk, Голодомо́р, Holodomor, ; derived from uk, морити голодом, lit=to kill by starvation, translit=moryty holodom, label=none), also known as the Terror-Famine or the Great Famine, was a man-made famin ...

and the Great Leap Forward

The Great Leap Forward (Second Five Year Plan) of the People's Republic of China (PRC) was an economic and social campaign led by the Chinese Communist Party (CCP) from 1958 to 1962. CCP Chairman Mao Zedong launched the campaign to reconstr ...

. Additional events included the use of genocide

Genocide is the intentional destruction of a people—usually defined as an ethnic, national, racial, or religious group—in whole or in part. Raphael Lemkin coined the term in 1944, combining the Greek word (, "race, people") with the ...

, conspiracy

A conspiracy, also known as a plot, is a secret plan or agreement between persons (called conspirers or conspirators) for an unlawful or harmful purpose, such as murder or treason, especially with political motivation, while keeping their agr ...

to commit genocide, and complicity in genocide. Such events have been described as crimes against humanity.Rosefielde, p. 6.Karlsson, p. 5.

The 2008 Prague Declaration on European Conscience and Communism

The Prague Declaration on European Conscience and Communism was a declaration which was initiated by the Czech government and signed on 3 June 2008 by prominent European politicians, former political prisoners and historians, among them former ...

stated that crimes which were committed in the name of communism

Communism (from Latin la, communis, lit=common, universal, label=none) is a far-left sociopolitical, philosophical, and economic ideology and current within the socialist movement whose goal is the establishment of a communist society, ...

should be assessed as crimes against humanity. Very few people have been tried for these crimes, although the government of Cambodia

Cambodia (; also Kampuchea ; km, កម្ពុជា, UNGEGN: ), officially the Kingdom of Cambodia, is a country located in the southern portion of the Indochinese Peninsula in Southeast Asia, spanning an area of , bordered by Thailand ...

has prosecuted former members of the Khmer Rouge

The Khmer Rouge (; ; km, ខ្មែរក្រហម, ; ) is the name that was popularly given to members of the Communist Party of Kampuchea (CPK) and by extension to the regime through which the CPK ruled Cambodia between 1975 and 1979 ...

and the governments of Estonia

Estonia, formally the Republic of Estonia, is a country by the Baltic Sea in Northern Europe. It is bordered to the north by the Gulf of Finland across from Finland, to the west by the sea across from Sweden, to the south by Latvia, an ...

, Latvia

Latvia ( or ; lv, Latvija ; ltg, Latveja; liv, Leţmō), officially the Republic of Latvia ( lv, Latvijas Republika, links=no, ltg, Latvejas Republika, links=no, liv, Leţmō Vabāmō, links=no), is a country in the Baltic region of ...

and Lithuania

Lithuania (; lt, Lietuva ), officially the Republic of Lithuania ( lt, Lietuvos Respublika, links=no ), is a country in the Baltic region of Europe. It is one of three Baltic states and lies on the eastern shore of the Baltic Sea. Lithuania ...

have passed laws that have led to the prosecution of several perpetrators for their crimes against the Baltic peoples. They were tried for crimes which they committed during the Occupation of the Baltic states

The Baltic states of Estonia, Latvia and Lithuania were invaded and occupied in June 1940 by the Soviet Union, under the leadership of Stalin and auspices of the Molotov-Ribbentrop Pact that had been signed between Nazi Germany and the Soviet ...

in 1940 and 1941 as well as for crimes which they committed during the Soviet reoccupation of those states which occurred after World War II. Trials were also held for attacks which the People's Commissariat for Internal Affairs

The People's Commissariat for Internal Affairs (russian: Наро́дный комиссариа́т вну́тренних дел, Naródnyy komissariát vnútrennikh del, ), abbreviated NKVD ( ), was the interior ministry of the Soviet Union.

...

(NKVD) carried out against the Forest Brethren.Naimark p. 25.

Cambodia

Cambodian genocide

The Cambodian genocide ( km, របបប្រល័យពូជសាសន៍នៅកម្ពុជា) was the systematic persecution and killing of Cambodians by the Khmer Rouge under the leadership of Communist Party of Kampuchea gener ...

which was carried out by the Khmer Rouge

The Khmer Rouge (; ; km, ខ្មែរក្រហម, ; ) is the name that was popularly given to members of the Communist Party of Kampuchea (CPK) and by extension to the regime through which the CPK ruled Cambodia between 1975 and 1979 ...

under the leadership of Pol Pot

Pol Pot; (born Saloth Sâr;; 19 May 1925 – 15 April 1998) was a Cambodian revolutionary, dictator, and politician who ruled Cambodia as Prime Minister of Democratic Kampuchea between 1976 and 1979. Ideologically a Marxist–Leninist ...

in what became known as the Killing Fields

The Killing Fields ( km, វាលពិឃាត, ) are a number of sites in Cambodia where collectively more than one million people were killed and buried by the Khmer Rouge regime (the Communist Party of Kampuchea) during its rule of t ...

was a crime against humanity.Totten, p. 359. Over the course of 4 years, the Pol Pot regime was responsible for the deaths of approximately 2 million people through starvation, exhaustion, execution, lack of medical care as a result of the communist utopia experiment. Legal scholars Antoine Garapon and David Boyle, sociologist Michael Mann

Michael Kenneth Mann (born February 5, 1943) is an American director, screenwriter, and producer of film and television who is best known for his distinctive style of crime drama. His most acclaimed works include the films '' Thief'' (1981) ...

and professor of political science Jacques Sémelin

Jacques Semelin is a French historian and political scientist. Professor at Sciences Po Paris and Senior researcher at the CNRS (Center for International Studies), his main fields are the Holocaust, mass violence, civil resistance and rescue in gen ...

all believe that the actions of the Communist Party of Kampuchea

The Communist Party of Kampuchea (CPK),, UNGEGN: , ALA-LC: ; french: Parti communiste du Kampuchea also known as the Khmer Communist Party,

can best be described as a crime against humanity rather than a genocide

Genocide is the intentional destruction of a people—usually defined as an ethnic, national, racial, or religious group—in whole or in part. Raphael Lemkin coined the term in 1944, combining the Greek word (, "race, people") with the ...

.Semelin, p. 344. In 2018, the Khmer Rouge was declared guilty of committing genocide against the minority Muslim Cham and Vietnamese. Conviction appeal against court decision was rejected in 2022. It reaffirms the ECCC's recognition of Khmer Rouges racial discriminations and ethnic cleansing against non-Cambodian (Khmer) minorities. The naming of the Cambodian Genocide is an overlooked problem because it downplays the overwhelming sufferings among targeted minority groups and the important roles of racism

Racism is the belief that groups of humans possess different behavioral traits corresponding to inherited attributes and can be divided based on the superiority of one race over another. It may also mean prejudice, discrimination, or antagoni ...

in understanding how the genocide was perpetrated. Historian Eric D. Weitz calls the Khmer Rouge's ethnic policy "racial communism."

In 1997, the co-prime ministers of Cambodia sought help from the United Nations in seeking justice for the crimes which were perpetrated by the communists during the years from 1975 to 1979. In June 1997, Pol Pot was taken prisoner during an internal power struggle within the Khmer Rouge and offered up to the international community. However, no country was willing to seek his extradition

Extradition is an action wherein one jurisdiction delivers a person accused or convicted of committing a crime in another jurisdiction, over to the other's law enforcement. It is a cooperative law enforcement procedure between the two jurisdi ...

.Lattimer, p. 214. The policies enacted by the Khmer Rouge led to the deaths of one quarter of the population in just four years.Jones, p. 188.

China

Under Mao Zedong

Mao Zedong

Mao Zedong pronounced ; also Romanization of Chinese, romanised traditionally as Mao Tse-tung. (26 December 1893 – 9 September 1976), also known as Chairman Mao, was a Chinese communist revolutionary who was the List of national founde ...

was the chairman

The chairperson, also chairman, chairwoman or chair, is the presiding officer of an organized group such as a board, committee, or deliberative assembly. The person holding the office, who is typically elected or appointed by members of the group ...

of the Chinese Communist Party

The Chinese Communist Party (CCP), officially the Communist Party of China (CPC), is the founding and sole ruling party of the People's Republic of China (PRC). Under the leadership of Mao Zedong, the CCP emerged victorious in the Chinese Ci ...

(CCP) which took control of China in 1949 until his death in September 1976. During this time, he instituted several reform efforts, the most notable of which were the Great Leap Forward

The Great Leap Forward (Second Five Year Plan) of the People's Republic of China (PRC) was an economic and social campaign led by the Chinese Communist Party (CCP) from 1958 to 1962. CCP Chairman Mao Zedong launched the campaign to reconstr ...

and the Cultural Revolution

The Cultural Revolution, formally known as the Great Proletarian Cultural Revolution, was a sociopolitical movement in the People's Republic of China (PRC) launched by Mao Zedong in 1966, and lasting until his death in 1976. Its stated goa ...

. In January 1958, Mao launched the first five-year plan, the latter part of which was known as the Great Leap Forward. The plan was intended to expedite production and heavy industry

Heavy industry is an industry that involves one or more characteristics such as large and heavy products; large and heavy equipment and facilities (such as heavy equipment, large machine tools, huge buildings and large-scale infrastructure); o ...

as a supplement to economic growth similar to the Soviet model and the defining factor behind Mao's Chinese Marxist policies. Mao spent ten months touring the country in 1958 in order to gain support for the Great Leap Forward and inspect the progress that had already been made. What this entailed was the humiliation, public castigation and torture of all who questioned the leap. The five-year-plan first instituted the division of farming communities into communes. The Chinese National Program for Agricultural Development (NPAD) began to accelerate its drafting plans for the countries industrial and agricultural outputs. The drafting plans were initially successful as the Great Leap Forward divided the Chinese workforce and production briefly soared.

Eventually, CCP planners developed even more ambitious goals such as replacing the draft plans for 1962 with those for 1967 and the industries developed supply bottlenecks, but they could not meet the growth demands. Rapid industrial development came in turn with a swelling of urban populations. Due to the furthering of collectivization, heavy industry production and the stagnation of the farming industry that did not keep up with the demands of population growth in combination with a year (1959) of unfortunate weather in farming areas, only 170 million tons of grain were produced, far below the actual amount of grain which the population needed. Mass starvation ensued and it was made even worse in 1960, when only 144 million tons of grain were produced, a total amount which was 26 million tons lower than the total amount of grain that was produced in 1959. The government instituted rationing, but between 1958 and 1962 it is estimated that at least 10 million people died of starvation. The famine did not go unnoticed and Mao was fully aware of the major famine that was sweeping the countryside, but rather than try to fix the problem he blamed it on counterrevolutionaries who were "hiding and dividing grain". Mao even symbolically decided to abstain from eating meat in honor of those who were suffering.

Due to the widespread famine across the country, there were many reports of human cannibalism

Human cannibalism is the act or practice of humans eating the flesh or internal organs of other human beings. A person who practices cannibalism is called a cannibal. The meaning of "cannibalism" has been extended into zoology to describe an in ...

, including that of a farmer from Hunan

Hunan (, ; ) is a landlocked province of the People's Republic of China, part of the South Central China region. Located in the middle reaches of the Yangtze watershed, it borders the province-level divisions of Hubei to the north, Jiangx ...

who was forced to kill and eat his own child. When questioned about it, he said he did it "out of mercy". An original estimate of the final death toll ranged from 15 to 40 million. According to Frank Dikötter, a chair professor of humanities at the University of Hong Kong

The University of Hong Kong (HKU) (Chinese: 香港大學) is a public research university in Hong Kong

Hong Kong ( (US) or (UK); , ), officially the Hong Kong Special Administrative Region of the People's Republic of China (abbr. Hon ...

and the author of ''Mao's Great Famine'', a book which details the Great Leap Forward and the consequences of the strong armed implementation of the economic reform, the total number of people who were killed in the famine which lasted from 1958 to 1962 ran upwards of 45 million. Of those who were killed in the famine, 6–8% of them were often tortured first and then prematurely killed by the government, 2% of them committed suicide

Suicide is the act of intentionally causing one's own death. Mental disorders (including depression, bipolar disorder, schizophrenia, personality disorders, anxiety disorders), physical disorders (such as chronic fatigue syndrome), and ...

and 5% of them died in Mao's labor camps which were built to hold those who were labelled "enemies of the people

The term enemy of the people or enemy of the nation, is a designation for the political or class opponents of the subgroup in power within a larger group. The term implies that by opposing the ruling subgroup, the "enemies" in question are ac ...

". In an article for ''The New York Times

''The New York Times'' (''the Times'', ''NYT'', or the Gray Lady) is a daily newspaper based in New York City with a worldwide readership reported in 2020 to comprise a declining 840,000 paid print subscribers, and a growing 6 million paid ...

'', Dikötter also references severe punishments for slight infractions such as being buried alive for stealing a handful of grain or losing an ear and being branded for digging up a potato. Dikotter claims that a chairman in an executive meeting in 1959 expressed apathy with regard to the widespread suffering, stating: "When there is not enough to eat, people starve to death. It is better to let half of the people die so that the other half can eat their fill". Anthony Garnaut clarifies that Dikötter's interpretation of Mao's quotation, "It is better to let half of the people die so that the other half can eat their fill." not only ignores the substantial commentary on the conference by other scholars and several of its key participants, but defies the very plain wording of the archival document in his possession on which he hangs his case.

Ethiopia

Following the overthrow of Ethiopian emperor

Following the overthrow of Ethiopian emperor Haile Selassie

Haile Selassie I ( gez, ቀዳማዊ ኀይለ ሥላሴ, Qädamawi Häylä Səllasé, ; born Tafari Makonnen; 23 July 189227 August 1975) was Emperor of Ethiopia from 1930 to 1974. He rose to power as Regent Plenipotentiary of Ethiopia (' ...

, the Derg

The Derg (also spelled Dergue; , ), officially the Provisional Military Administrative Council (PMAC), was the military junta that ruled Ethiopia, then including present-day Eritrea, from 1974 to 1987, when the military leadership formally " ...

gained control over Ethiopia and established a Marxist–Leninist state. They enacted the Red Terror

The Red Terror (russian: Красный террор, krasnyj terror) in Soviet Russia was a campaign of political repression and executions carried out by the Bolsheviks, chiefly through the Cheka, the Bolshevik secret police. It started in ...

against political opponents, killing an estimated 10,000 to 750,000 people.US admits helping Mengistu escapeBBC, 22 December 1999 Derg chairman

Mengistu Haile Mariam

Mengistu Haile Mariam ( am, መንግሥቱ ኀይለ ማሪያም, pronunciation: ; born 21 May 1937) is an Ethiopian politician and former army officer who was the head of state of Ethiopia from 1977 to 1991 and General Secretary of the Wor ...

said "We are doing what Lenin

Vladimir Ilyich Ulyanov. ( 1870 – 21 January 1924), better known as Vladimir Lenin,. was a Russian revolutionary, politician, and political theorist. He served as the first and founding head of government of Soviet Russia from 1917 to 1 ...

did. You cannot build socialism

Socialism is a left-wing economic philosophy and movement encompassing a range of economic systems characterized by the dominance of social ownership of the means of production as opposed to private ownership. As a term, it describes th ...

without Red Terror

The Red Terror (russian: Красный террор, krasnyj terror) in Soviet Russia was a campaign of political repression and executions carried out by the Bolsheviks, chiefly through the Cheka, the Bolshevik secret police. It started in ...

." Christopher Andrew and Vasili Mitrokhin

Vasili Nikitich Mitrokhin (russian: link=no, Васи́лий Ники́тич Митро́хин; March 3, 1922 – January 23, 2004) was a major and senior archivist for the Soviet Union's foreign intelligence service, the First Chief Di ...

. ''The World Was Going Our Way: The KGB and the Battle for the Third World.'' Basic Books, 2005. ch. 25. Groups of people were herded into churches that were then burned down, and women were subjected to systematic rape by soldiers. The Save the Children Fund

The Save the Children Fund, commonly known as Save the Children, is an international non-governmental organization established in the United Kingdom in 1919 to improve the lives of children through better education, health care, and economic ...

reported that the victims of the Red Terror included not only adults but 1,000 or more children, mostly aged between eleven and thirteen, whose corpses were left in the streets of Addis Ababa.

On 13 August 2004, 33 top former Derg officials were presented in trial for genocide and other human rights violations during the Red Terror. The officials appealed for a pardon to the Prime Minister

A prime minister, premier or chief of cabinet is the head of the cabinet and the leader of the ministers in the executive branch of government, often in a parliamentary or semi-presidential system. Under those systems, a prime minister is ...

Meles Zenawi in a forum to "beg the Ethiopian public for their pardon for the mistakes done knowingly or unknowingly" during the Derg regime. No official response made by the government to the date. The Red Terror trial included grave human rights violations, comprising genocide

Genocide is the intentional destruction of a people—usually defined as an ethnic, national, racial, or religious group—in whole or in part. Raphael Lemkin coined the term in 1944, combining the Greek word (, "race, people") with the ...

, crime against humanity

Crimes against humanity are widespread or systemic acts committed by or on behalf of a ''de facto'' authority, usually a state, that grossly violate human rights. Unlike war crimes, crimes against humanity do not have to take place within the ...

, torture

Torture is the deliberate infliction of severe pain or suffering on a person for reasons such as punishment, extracting a confession, interrogation for information, or intimidating third parties. Some definitions are restricted to acts ...

, rape

Rape is a type of sexual assault usually involving sexual intercourse or other forms of sexual penetration carried out against a person without their consent. The act may be carried out by physical force, coercion, abuse of authority, or ...

and forced disappearances

An enforced disappearance (or forced disappearance) is the secret abduction or imprisonment of a person by a state or political organization, or by a third party with the authorization, support, or acquiescence of a state or political organiza ...

which be would punishable under Article 7 of the Universal Declaration of Human Rights, article 26 of the International Covenant on Civil and Political Rights as well as article 3 of the African Charter on Human and People's Rights, all of which made part of the Ethiopian law.

North Korea

Three victims of the prison camp system in North Korea unsuccessfully attempted to bringKim Jong-il

Kim Jong-il (; ; ; born Yuri Irsenovich Kim;, 16 February 1941 – 17 December 2011) was a North Korean politician who was the second supreme leader of North Korea from 1994 to 2011. He led North Korea from the 1994 death of his father Ki ...

to justice with the aid of the Citizens Coalition for Human Rights of abductees and North Korean Refugees. In December 2010, they filed charges in The Hague

The Hague ( ; nl, Den Haag or ) is a city and municipality of the Netherlands, situated on the west coast facing the North Sea. The Hague is the country's administrative centre and its seat of government, and while the official capital o ...

. The NGO group Christian Solidarity Worldwide

Christian Solidarity Worldwide (CSW) is a human rights organisation which specialises in religious freedom and works on behalf of those persecuted for their Christian beliefs, persecuted for other religious belief or persecuted for lack of beli ...

has stated that the gulag system appears to be specifically designed to kill a large number of people who are labelled enemies or have a differing political belief.Jones, p. 216.

Romania

In a speech before theParliament of Romania

The Parliament of Romania ( ro, Parlamentul României) is the national Bicameralism, bicameral legislature of Romania, consisting of the Chamber of Deputies (Romania), Chamber of Deputies ( ro, Camera Deputaților) and the Senate of Romania, Sen ...

, President

President most commonly refers to:

*President (corporate title)

* President (education), a leader of a college or university

* President (government title)

President may also refer to:

Automobiles

* Nissan President, a 1966–2010 Japanese ...

Traian Băsescu

Traian Băsescu (; born 4 November 1951) is a conservative Romanian politician who served as President of Romania from 2004 to 2014. Prior to his presidency, Băsescu served as Romanian Minister of Transport on multiple occasions between 1991 ...

stated that "the criminal and illegitimate former communist regime committed massive human rights violations and crimes against humanity, killing and persecuting as many as two million people between 1945 and 1989". The speech was based on the 660-page report of a Presidential Commission headed by Vladimir Tismăneanu

Vladimir Tismăneanu (; born July 4, 1951) is a Romanian American political scientist, political analyst, sociologist, and professor at the University of Maryland, College Park. A specialist in political systems and comparative politics, he is di ...

, a professor at the University of Maryland

The University of Maryland, College Park (University of Maryland, UMD, or simply Maryland) is a public land-grant research university in College Park, Maryland. Founded in 1856, UMD is the flagship institution of the University System of ...

. The report also stated that "the regime exterminated people by assassination and deportation of hundreds of thousands of people" and it also highlighted the Pitești Experiment.

Engineer and former political prisoner Gheorghe Boldur-Lățescu has also stated that the Pitești Experiment was a crime against humanity,Boldur-Lățescu p. 22 while Dennis Deletant

Dennis Deletant (born 5 March 1946) is a British-Romanian historian of the history of Romania. As of 2019, he is Visiting Ion Rațiu Professor of Romanian Studies at Georgetown University and Emeritus Professor of Romanian Studies at the UCL S ...

has described it as " experiment of a grotesque originality ... hich

Ij ( fa, ايج, also Romanized as Īj; also known as Hich and Īch) is a village in Golabar Rural District, in the Central District of Ijrud County, Zanjan Province, Iran

Iran, officially the Islamic Republic of Iran, and also ...

employed techniques of psychiatric abuse which were not only designed to inculcate terror into opponents of the regime but also to destroy the personality of the individual. The nature and enormity of the experiment ... set Romania apart from the other Eastern European regimes."

Soviet Union

Yugoslavia

Dominic McGoldrick writes that as the head of a "highlycentralized

Centralisation or centralization (see spelling differences) is the process by which the activities of an organisation, particularly those regarding planning and decision-making, framing strategy and policies become concentrated within a particu ...

and oppressive" dictatorship, Josip Broz Tito

Josip Broz ( sh-Cyrl, Јосип Броз, ; 7 May 1892 – 4 May 1980), commonly known as Tito (; sh-Cyrl, Тито, links=no, ), was a Yugoslav communist revolutionary and statesman, serving in various positions from 1943 until his death ...

wielded tremendous power in Yugoslavia, with his dictatorial rule administered through an elaborate bureaucracy which routinely suppressed human rights. The main victims of this repression were known and alleged Stalinists during the first years such as Dragoslav Mihailović

Dragoslav Mihailović (Serbian Cyrillic: Драгослав Михаиловић; born 17 November 1930) is a Serbian writer.

Life

He graduated in Yugoslav literature from the University of Belgrade in 1957 and is a member of the Serbian Academ ...

and Dragoljub Mićunović

Dragoljub Mićunović ( sr-Cyrl, Драгољуб Мићуновић ; born 14 July 1930) is a Serbian politician and philosopher. As one of the founders of the Democratic Party, he served as its leader from 1990 to 1994, and as the president of ...

, but during the following years even some of the most prominent among Tito's collaborators were arrested. On 19 November 1956, Milovan Đilas

Milovan Djilas (; , ; 12 June 1911 – 30 April 1995) was a Yugoslav communist politician, theorist and author. He was a key figure in the Partisan movement during World War II, as well as in the post-war government. A self-identified democra ...

, perhaps the closest of Tito's collaborator and widely regarded as Tito's possible successor, was arrested because of his criticism against Tito's regime. The repression did not exclude intellectuals and writers such as Venko Markovski, who was arrested and sent to jail in January 1956 for writing poems considered anti-Titoist. Tito made dramatic bloody repression and several massacres of POW after World War II (see Bleiburg repatriations

The Bleiburg repatriations ( see terminology) occurred in May 1945, after the end of World War II in Europe, during which Yugoslavia had been occupied by the Axis powers, when tens of thousands of soldiers and civilians associated with the Axis ...

and Foibe massacres

The foibe massacres (; ; ), or simply the foibe, refers to mass killings both during and after World War II, mainly committed by Yugoslav Partisans and OZNA in the then-Italian territories of Julian March (Karst Region and Istria), Kvarner an ...

).

Tito's Yugoslavia remained a tightly controlled police state. According to David Matas

David Matas (born 29 August 1943) is the senior legal counsel of B'nai Brith Canada who currently resides in Winnipeg, Manitoba. He has maintained a private practice in refugee, immigration, and human rights law since 1979, and has published vario ...

, outside the Soviet Union, Yugoslavia had more political prisoners

A political prisoner is someone imprisoned for their political activity. The political offense is not always the official reason for the prisoner's detention.

There is no internationally recognized legal definition of the concept, although nu ...

than all of the rest of Eastern Europe combined. Tito's secret police was modeled on the Soviet KGB. Its members were ever-present and often acted extrajudicially, with victims including middle-class intellectuals, liberals and democrats. Yugoslavia was a signatory to the International Covenant on Civil and Political Rights

The International Covenant on Civil and Political Rights (ICCPR) is a multilateral treaty that commits nations to respect the civil and political rights of individuals, including the right to life, freedom of religion, freedom of speech, fre ...

, but scant regard was paid to some of its provisions.

Near the end of the Second World War

World War II or the Second World War, often abbreviated as WWII or WW2, was a world war that lasted from 1939 to 1945. It involved the vast majority of the world's countries—including all of the great powers—forming two opposi ...

, Banat Swabians

The Banat Swabians are an ethnic German population in the former Kingdom of Hungary in Central-Southeast Europe, part of the Danube Swabians. They emigrated in the 18th century to what was then the Austrian Empire's Banat of Temeswar province, la ...

who were suspected to have been involved with the Nazi administration were placed into internment camps. Many were tortured, and at least 5,800 were killed. Others were subject to forced labor. In March 1945, the surviving Swabians were ghetto

A ghetto, often called ''the'' ghetto, is a part of a city in which members of a minority group live, especially as a result of political, social, legal, environmental or economic pressure. Ghettos are often known for being more impoverished ...

ized in "village camps", later described as "extermination camps" by the survivors, where the death rate ranged as high as 50%. The most notorious camp was at Knićanin

Knićanin (, ) is a village in Serbia. It is located in the Zrenjanin municipal area, in the Banat region (Central Banat District), Vojvodina province. Its population is 2,034 (2002 census) and most of its inhabitants are ethnic Serbs (97.39% ...

(formerly Rudolfsgnad), where an estimated 11,000 to 12,500 Swabians died.

Some 120,000 Macedonian Serbs

The Serbs are one of the constitutional peoples of North Macedonia ( mk, Србите во Северна Македонија, sr-Cyrl-Latn, Срби у Северној Македонији, Srbi u Severnoj Makedoniji), numbering about 24,000 ...

were forced to emigrate to Serbia by the Yugoslav Communists after they had opted for Serbian citizenship in 1944. Those who stayed were subject to increasing Macedonian efforts, such as forcibly changing their surnames, substituting "''ić''" with ''"ski " ( Jovanović -'' Jovanovski). In the whole period after the Second World War the Serbs in the Socialist Republic of Macedonia were kept from freely developing their national and cultural identity. The Serbs were treated like second-class citizen

A second-class citizen is a person who is systematically and actively discriminated against within a state or other political jurisdiction, despite their nominal status as a citizen or a legal resident there. While not necessarily slaves, o ...

s.

See also

*Camp 22

Hoeryong concentration camp (or Haengyong concentration camp) was a prison camp in North Korea that was reported to have been closed in 2012. The official name was Kwalliso (penal labour colony) No. 22. The camp was a maximum security area, comp ...

(North Korea

North Korea, officially the Democratic People's Republic of Korea (DPRK), is a country in East Asia. It constitutes the northern half of the Korean Peninsula and shares borders with China and Russia to the north, at the Yalu (Amnok) and T ...

)

* Communism in Romania

* Communist state

A communist state, also known as a Marxist–Leninist state, is a one-party state that is administered and governed by a communist party guided by Marxism–Leninism. Marxism–Leninism was the state ideology of the Soviet Union, the Comint ...

* Communist terrorism

Communist terrorism is terrorism carried out in the advancement of, or by groups who adhere to, communism and its related ideologies, such as Leninism, Marxism–Leninism, Trotskyism and Maoism. Historically, communist terrorism has sometimes ta ...

* Comparison of Nazism and Stalinism

Comparison or comparing is the act of evaluating two or more things by determining the relevant, comparable characteristics of each thing, and then determining which characteristics of each are similar to the other, which are different, and t ...

* Hoxhaism

Hoxhaism () is a variant of anti-revisionist Marxism–Leninism that developed in the late 1970s due to a split in the anti-revisionist movement, appearing after the ideological dispute between the Chinese Communist Party and the Party of Labo ...

* Juche

''Juche'' ( ; ), officially the ''Juche'' idea (), is the state ideology of North Korea and the official ideology of the Workers' Party of Korea. North Korean sources attribute its conceptualization to Kim Il-sung, the country's founder and f ...

* Laogai

''Laogai'' (), short for ''laodong gaizao'' (), which means reform through labor, is a criminal justice system involving the use of penal labor and prison farms in the People's Republic of China (PRC) and North Korea (DPRK). ''Láogǎi'' i ...

(China

China, officially the People's Republic of China (PRC), is a country in East Asia. It is the world's List of countries and dependencies by population, most populous country, with a Population of China, population exceeding 1.4 billion, slig ...

)

* Left-wing terrorism

Left-wing terrorism or far-left terrorism is terrorism committed with the aim of overthrowing current capitalist systems and replacing them with communist or socialist societies. Left-wing terrorism can also occur within already socialist states ...

* Maoism

Maoism, officially called Mao Zedong Thought by the Chinese Communist Party, is a variety of Marxism–Leninism that Mao Zedong developed to realise a socialist revolution in the agricultural, pre-industrial society of the Republic of Ch ...

* Marxism–Leninism

Marxism–Leninism is a communist ideology which was the main communist movement throughout the 20th century. Developed by the Bolsheviks, it was the state ideology of the Soviet Union, its satellite states in the Eastern Bloc, and vario ...

* Mass killings under communist regimes

* Military Units to Aid Production

Military Units to Aid Production or UMAPs (Unidades Militares de Ayuda a la Producción) were agricultural forced labor camps operated by the Cuban government from November 1965 to July 1968 in the province of Camagüey.Guerra, Lillian. ""Gender ...

(Cuba

Cuba ( , ), officially the Republic of Cuba ( es, República de Cuba, links=no ), is an island country comprising the island of Cuba, as well as Isla de la Juventud and several minor archipelagos. Cuba is located where the northern Caribb ...

)

* Poison laboratory of the Soviet secret services

The poison laboratory of the Soviet secret services, alternatively known as Laboratory 1, Laboratory 12, and Kamera (which means "The Cell" in Russian), was a covert research-and-development facility of the Soviet secret police agencies. Th ...

* Prisons in North Korea

North Korean prisons have conditions that are unsanitary, life-threatening and are comparable to historical concentration camps. A significant number of prisoners have died each year, since they are subject to torture and inhumane treatment. Publ ...

* Re-education camp (Vietnam)

Re-education camps ( vi, Trại cải tạo) were prison camps operated by the Communist government of Vietnam

The Government of the Socialist Republic of Vietnam (), also known as the Vietnamese Government or the Government of Vietnam (), ...

* Spaç Prison

The Spaç Prison () was a political prison in Communist Albania at the village of Spaç. The former prison is listed as a second-category national monument. There were plans to turn the rapidly deteriorating site into a museum, but as of February ...

(People's Socialist Republic of Albania

The People's Socialist Republic of Albania ( sq, Republika Popullore Socialiste e Shqipërisë, links=no) was the Marxist–Leninist one party state that existed in Albania from 1946 to 1992 (the official name of the country was the People's R ...

)

* Stalinism

Stalinism is the means of governing and Marxist-Leninist policies implemented in the Soviet Union from 1927 to 1953 by Joseph Stalin. It included the creation of a one-party totalitarian police state, rapid industrialization, the the ...

* Titoism

Titoism is a political philosophy most closely associated with Josip Broz Tito during the Cold War. It is characterized by a broad Yugoslav identity, workers' self-management, a political separation from the Soviet Union, and leadership in th ...

* Xinjiang internment camps

The Xinjiang internment camps, officially called vocational education and training centers ( zh, 职业技能教育培训中心, Zhíyè jìnéng jiàoyù péixùn zhōngxīn) by the government of China, are internment camps operated ...

(Xinjiang

Xinjiang, SASM/GNC: ''Xinjang''; zh, c=, p=Xīnjiāng; formerly romanized as Sinkiang (, ), officially the Xinjiang Uygur Autonomous Region (XUAR), is an autonomous region of the People's Republic of China (PRC), located in the northwes ...

)

* Yodok concentration camp (North Korea

North Korea, officially the Democratic People's Republic of Korea (DPRK), is a country in East Asia. It constitutes the northern half of the Korean Peninsula and shares borders with China and Russia to the north, at the Yalu (Amnok) and T ...

)

References

Notes

Bibliography

* * * * Jones, Adam (2010). ''Genocide: A Comprehensive Introduction''. Routledge. . * Karlsson, Klas-Göran; Schoenhals, Michael (2008). ''Crimes Against Humanity Under Communist Regimes''. Forum for Living History. * Kemp-Welch, A. (2008). ''Poland Under Communism: A Cold War History''.Cambridge University Press

Cambridge University Press is the university press of the University of Cambridge. Granted letters patent by King Henry VIII in 1534, it is the oldest university press in the world. It is also the King's Printer.

Cambridge University Pr ...

. .

* Lattimer, Mark and Sands, Philippe. (2003) ''Justice for Crimes Against Humanity'' Hart Publishing .

*

*

* Naimark, Norman M. (2010). ''Stalin's Genocides''. Princeton University Press. .

* Rosefielde, Steven (2009). ''Red Holocaust''. Routledge

Routledge () is a British multinational publisher. It was founded in 1836 by George Routledge, and specialises in providing academic books, journals and online resources in the fields of the humanities, behavioural science, education, law ...

. .

* Semelin, Jacques (2009). ''Purify and Destroy: The Political Uses of Massacre and Genocide''. Columbia University Press

Columbia University Press is a university press based in New York City, and affiliated with Columbia University. It is currently directed by Jennifer Crewe (2014–present) and publishes titles in the humanities and sciences, including the fie ...

. .

* Totten, Samuel; Parsons, William S.; Charny, Israel W. (2004). ''Century of Genocide: Critical Essays and Eyewitness Accounts''. Routledge. .

External links

* {{cite web, url=http://www.globalmuseumoncommunism.org/, title=Global Museum on Communism, publisher=The Global Museum on Communism, archive-url=https://web.archive.org/web/20101213221048/http://www.globalmuseumoncommunism.org/, archive-date=13 December 2010, access-date=8 September 2020 Communism Communist repression Crimes against humanity Marxism–Leninism