Crewe Hall on:

[Wikipedia]

[Google]

[Amazon]

Crewe Hall is a Jacobean mansion located near Crewe Green, east of

A few years after the hall's completion in 1636,

A few years after the hall's completion in 1636,

Anne Crewe's great-grandson, John Crewe (1742–1829), was created the first

Anne Crewe's great-grandson, John Crewe (1742–1829), was created the first  Hungerford Crewe never married and on his death in 1894, the barony became extinct. The hall was inherited by his nephew, Robert Milnes, Baron Houghton (1858–1945), the son of Annabella Hungerford Crewe; he adopted the name Crewe, to become Crewe-Milnes. The Crewe title was revived as an earldom for him in 1895, and he later became the Marquess of Crewe. A Liberal politician and poet, Crewe-Milnes held several key Cabinet positions between 1905 and 1916, and was a trusted aide to

Hungerford Crewe never married and on his death in 1894, the barony became extinct. The hall was inherited by his nephew, Robert Milnes, Baron Houghton (1858–1945), the son of Annabella Hungerford Crewe; he adopted the name Crewe, to become Crewe-Milnes. The Crewe title was revived as an earldom for him in 1895, and he later became the Marquess of Crewe. A Liberal politician and poet, Crewe-Milnes held several key Cabinet positions between 1905 and 1916, and was a trusted aide to

The Jacobean hall was built for Sir Randolph Crewe between 1615 and 1636. The architect of the original building is unknown, although some historians have concluded that its design was based on drawings by

The Jacobean hall was built for Sir Randolph Crewe between 1615 and 1636. The architect of the original building is unknown, although some historians have concluded that its design was based on drawings by  Hearth-tax assessments of 1674 show the original hall to have been one of the largest houses in Cheshire, its 42 hearths being surpassed only by Cholmondeley House and

Hearth-tax assessments of 1674 show the original hall to have been one of the largest houses in Cheshire, its 42 hearths being surpassed only by Cholmondeley House and

The house remained unaltered for much of the 18th century, in contrast to most of the other principal seats in the county.Hodson, pp. 80–81 It was described in 1769 as "a square of very old date ... more to be admired now for its antiquity than elegance or conveniency." Work was carried out during the 1780s and '90s for John Crewe (later the first Baron Crewe). A service wing to the west in a Jacobean revival style was added to the hall in 1780. The principal interiors of the old building were redecorated in neo-Classical style at this time, although the original layout with great hall, long gallery and drawing room was retained. Improvements were made to the wine cellars and bedrooms in 1783, and J. Cheney was employed to build a new attic staircase and seven bedrooms in 1796.

The house remained unaltered for much of the 18th century, in contrast to most of the other principal seats in the county.Hodson, pp. 80–81 It was described in 1769 as "a square of very old date ... more to be admired now for its antiquity than elegance or conveniency." Work was carried out during the 1780s and '90s for John Crewe (later the first Baron Crewe). A service wing to the west in a Jacobean revival style was added to the hall in 1780. The principal interiors of the old building were redecorated in neo-Classical style at this time, although the original layout with great hall, long gallery and drawing room was retained. Improvements were made to the wine cellars and bedrooms in 1783, and J. Cheney was employed to build a new attic staircase and seven bedrooms in 1796.

Crewe Hall is a grade-I-listed mansion located at in the civil parish of Crewe Green, ½ mile (1 km) from the edge of

Crewe Hall is a grade-I-listed mansion located at in the civil parish of Crewe Green, ½ mile (1 km) from the edge of  The east face of the eastern wing has four bays with canted bay windows, shaped end gables and a central cartouche. In the centre of the northern (garden) face is a large

The east face of the eastern wing has four bays with canted bay windows, shaped end gables and a central cartouche. In the centre of the northern (garden) face is a large

The interior of Crewe Hall contains a mixture of original Jacobean work, faithful reproductions of the original Jacobean designs (which in some cases had been recorded), and work in the High Victorian style designed by Barry. The entrance hall in the east wing was remodelled by both

The interior of Crewe Hall contains a mixture of original Jacobean work, faithful reproductions of the original Jacobean designs (which in some cases had been recorded), and work in the High Victorian style designed by Barry. The entrance hall in the east wing was remodelled by both

To the east of the entrance lies the dining room, which was formerly the Jacobean

To the east of the entrance lies the dining room, which was formerly the Jacobean  The suite of

The suite of  The long gallery, along the north side, has a chimneypiece in coloured marbles with busts by

The long gallery, along the north side, has a chimneypiece in coloured marbles with busts by

The former stables, in red brick with a tiled roof, were completed around 1636 and are contemporary with the Jacobean mansion; they are listed at

The former stables, in red brick with a tiled roof, were completed around 1636 and are contemporary with the Jacobean mansion; they are listed at  The north and south sides of the quadrangle have large arched carriage openings beneath shaped gables; the keystones are carved with horse's heads. The walls within the carriageway opening are decorated with bands of blue brick. The east, north and south faces are all finished with an openwork brick parapet with a stone coping. The west building has twelve arched openings accessed from the courtyard. The main storeys of the quadrangle mainly have three-light, stone-dressed

The north and south sides of the quadrangle have large arched carriage openings beneath shaped gables; the keystones are carved with horse's heads. The walls within the carriageway opening are decorated with bands of blue brick. The east, north and south faces are all finished with an openwork brick parapet with a stone coping. The west building has twelve arched openings accessed from the courtyard. The main storeys of the quadrangle mainly have three-light, stone-dressed  The park has two gate lodges; both are listed at grade II. The northern lodge at Slaughter Hill is by Blore and dates from 1847. In red brick with darker-brick diapering, stone dressings and a slate roof, it has a T-shaped plan with a single storey, and is Jacobean in style. It features two shaped gables, each decorated with a panel carved with Crewe Estate emblems, and a hexagonal central bay with a pyramidal roof which forms a porch. The

The park has two gate lodges; both are listed at grade II. The northern lodge at Slaughter Hill is by Blore and dates from 1847. In red brick with darker-brick diapering, stone dressings and a slate roof, it has a T-shaped plan with a single storey, and is Jacobean in style. It features two shaped gables, each decorated with a panel carved with Crewe Estate emblems, and a hexagonal central bay with a pyramidal roof which forms a porch. The

The

The  Formal gardens were laid out around the house by W. A. Nesfield in around 1840–50 for Hungerford Crewe. Nesfield's design included statuary, gravelled walks and elaborate parterres realised using low box hedges and coloured minerals. Balustraded terraces were also constructed on the north and south sides of the hall, probably designed by

Formal gardens were laid out around the house by W. A. Nesfield in around 1840–50 for Hungerford Crewe. Nesfield's design included statuary, gravelled walks and elaborate parterres realised using low box hedges and coloured minerals. Balustraded terraces were also constructed on the north and south sides of the hall, probably designed by  The entrance gates and wall separating the gardens from the park and farmland date from 1878 and are listed at grade II. The wrought-iron gates are by Cubitt & Co., and were exhibited at the Paris Exhibition of 1878. Two outer single gates and a double inner gate are supported by four sandstone

The entrance gates and wall separating the gardens from the park and farmland date from 1878 and are listed at grade II. The wrought-iron gates are by Cubitt & Co., and were exhibited at the Paris Exhibition of 1878. Two outer single gates and a double inner gate are supported by four sandstone

Crewe Hall Farmhouse, the estate's home farm, stands on the edge of the grounds, ¼ mile to the south east of the hall; it dates from around 1702 and is listed at

Crewe Hall Farmhouse, the estate's home farm, stands on the edge of the grounds, ¼ mile to the south east of the hall; it dates from around 1702 and is listed at

As of 2019, Crewe Hall is a hotel in the QHotels group, set in of parkland, with a restaurant, brasserie, conference facilities, tennis courts and health club, including a gym, spa and swimming pool. There are 117 bedrooms, of which 25 are located in the old building. The hall is licensed for civil wedding ceremonies. The hall and park are not otherwise open to the public. The

As of 2019, Crewe Hall is a hotel in the QHotels group, set in of parkland, with a restaurant, brasserie, conference facilities, tennis courts and health club, including a gym, spa and swimming pool. There are 117 bedrooms, of which 25 are located in the old building. The hall is licensed for civil wedding ceremonies. The hall and park are not otherwise open to the public. The

''The History of the Worthies of England'' (Vol. 1)

(London:

''Barthomley: In Letters from a Former Rector to his Eldest Son''

(London: Longman, Brown, Green, and Longmans), retrieved on 25 January 2009 * Hodson, J. Howard (1978). ''Cheshire, 1660–1780: Restoration to Industrial Revolution'' (''A History of Cheshire'', Vol. 9; series editor: J.J. Bagley) (Chester: Cheshire Community Council) () * Moss, Fletcher (1910). ''The Fifth Book of Pilgrimages to Old Homes'' (Didsbury: F. Moss) *

Crewe Hall, with an illustration.

''

Qhotels: Crewe Hall

{{good article Grade I listed houses Hotels in Cheshire Grade I listed buildings in Cheshire Grade II* listed buildings in Cheshire Grade II listed buildings in Cheshire Country houses in Cheshire Parks and open spaces in Cheshire World War II prisoner of war camps in England Houses completed in 1636 Houses completed in 1870 Edward Blore buildings Buildings and structures in Crewe 1636 establishments in England Country house hotels Edward Middleton Barry buildings Gardens by Humphry Repton Gardens by Capability Brown

Crewe

Crewe () is a railway town and civil parish in the unitary authority of Cheshire East in Cheshire, England. The Crewe built-up area had a total population of 75,556 in 2011, which also covers parts of the adjacent civil parishes of Willaston ...

, in Cheshire

Cheshire ( ) is a ceremonial and historic county in North West England, bordered by Wales to the west, Merseyside and Greater Manchester to the north, Derbyshire to the east, and Staffordshire and Shropshire to the south. Cheshire's county tow ...

, England. Described by Nikolaus Pevsner

Sir Nikolaus Bernhard Leon Pevsner (30 January 1902 – 18 August 1983) was a German-British art historian and architectural historian best known for his monumental 46-volume series of county-by-county guides, '' The Buildings of England'' ...

as one of the two finest Jacobean houses in Cheshire,Pevsner & Hubbard, p. 22 it is listed at grade I. Built in 1615–36 for Sir Randolph Crewe, it was one of the county's largest houses in the 17th century, and was said to have "brought London into Cheshire".

The hall was extended in the late 18th century and altered by Edward Blore

Edward Blore (13 September 1787 – 4 September 1879) was a 19th-century English landscape and architectural artist, architect and antiquary.

Early career

He was born in Derby, the son of the antiquarian writer Thomas Blore.

Blore's back ...

in the early Victorian era. It was extensively restored by E. M. Barry

Edward Middleton Barry RA (7 June 1830 – 27 January 1880) was an English architect of the 19th century.

Biography

Edward Barry was the third son of Sir Charles Barry, born in his father's house, 27 Foley Place, London. In infancy he was ...

after a fire in 1866, and is considered among his best works.de Figueiredo & Treuherz, pp. 66–71 Other artists and craftsmen employed during the restoration include J. Birnie Philip, J. G. Crace

John Gregory Crace (26 May 1809 – 13 August 1889) was a British interior decorator and author.

Early life and education

The Crace family had been prominent London interior decorators since Edward Crace (1725–1799), later keeper of the roya ...

, Henry Weekes

Henry Weekes (14 January 1807 – 28 May 1877) was an English sculptor, best known for his portraiture. He was among the most successful British sculptors of the mid- Victorian period.

Personal life

Weekes was born at Canterbury, Kent, to Capo ...

and the firm of Clayton and Bell

Clayton and Bell was one of the most prolific and proficient British workshops of stained-glass windows during the latter half of the 19th century and early 20th century. The partners were John Richard Clayton (1827–1913) and Alfred Bell (1832 ...

. The interior is elaborately decorated and contains many fine examples of wood carving, chimneypieces and plasterwork, some of which are Jacobean in date.

The park was landscaped during the 18th century by Capability Brown

Lancelot Brown (born c. 1715–16, baptised 30 August 1716 – 6 February 1783), more commonly known as Capability Brown, was an English gardener and landscape architect, who remains the most famous figure in the history of the English lan ...

, William Emes

William Emes (1729 or 1730–13 March 1803) was an English landscape gardener.

Biography

Details of his early life are not known but in 1756 he was appointed head gardener to Sir Nathaniel Curzon at Kedleston Hall, Derbyshire. He left this post ...

, John Webb and Humphry Repton

Humphry Repton (21 April 1752 – 24 March 1818) was the last great English landscape designer of the eighteenth century, often regarded as the successor to Capability Brown; he also sowed the seeds of the more intricate and eclectic styles of ...

, and formal gardens were designed by W. A. Nesfield in the 19th century. On the estate are cottages designed by Nesfield's son, William Eden Nesfield, which Pevsner considered to have introduced features such as tile hanging and pargetting into Cheshire. The stables quadrangle is contemporary with the hall and is listed at grade II*.

The hall remained the seat of various branches of the Crewe family until 1936, when the land was sold to the Duchy of Lancaster

The Duchy of Lancaster is the private estate of the British sovereign as Duke of Lancaster. The principal purpose of the estate is to provide a source of independent income to the sovereign. The estate consists of a portfolio of lands, properti ...

. It was used as offices after the Second World War

World War II or the Second World War, often abbreviated as WWII or WW2, was a world war that lasted from 1939 to 1945. It involved the vast majority of the world's countries—including all of the great powers—forming two opposi ...

, serving as the headquarters for the Wellcome Foundation for nearly thirty years. As of 2019, it is used as a hotel, restaurant and health club.

History

Sir Randolph Crewe, Civil War and the Restoration

Crewe

Crewe () is a railway town and civil parish in the unitary authority of Cheshire East in Cheshire, England. The Crewe built-up area had a total population of 75,556 in 2011, which also covers parts of the adjacent civil parishes of Willaston ...

was the seat of the de Crewe (or de Criwa) family in the 12th and 13th centuries; they built a timber-framed

Timber framing (german: Holzfachwerk) and "post-and-beam" construction are traditional methods of building with heavy timbers, creating structures using squared-off and carefully fitted and joined timbers with joints secured by large woode ...

manor house there in around 1170.Curran, pp. 2,5 The manor passed to the de Praers family of Barthomley in 1319 by the marriage of Johanna de Crewe to Richard de Praers. Later in the 14th century it passed to the Fouleshurst (or Foulehurst) family, who held the manor jointly with that of Barthomley until around 1575, when the estate was dispersed. Legal problems resulted in the lands being acquired by Sir Christopher Hatton

Sir Christopher Hatton KG (1540 – 20 November 1591) was an English politician, Lord Chancellor of England and a favourite of Elizabeth I of England. He was one of the judges who found Mary, Queen of Scots guilty of treason.

Early years

Si ...

, from whose heirs Sir Randolph Crewe (1559–1646) purchased an extensive estate including the manors of Crewe, Barthomley and Haslington

Haslington is a village and civil parish in the unitary authority of Cheshire East and the ceremonial county of Cheshire, England. It lies about 2 miles (3 km) north-east of the much larger railway town of Crewe and approximately 4 miles (6. ...

in 1608 for over £6,000 (£ today).

Born in nearby Nantwich

Nantwich ( ) is a market town and civil parish in the unitary authority of Cheshire East in Cheshire, England. It has among the highest concentrations of listed buildings in England, with notably good examples of Tudor and Georgian architecture. ...

, reputedly the son of a tanner, Sir Randolph (or Ranulph) had risen through the legal profession to become a judge, member of parliament and the parliamentary Speaker

Speaker may refer to:

Society and politics

* Speaker (politics), the presiding officer in a legislative assembly

* Public speaker, one who gives a speech or lecture

* A person producing speech: the producer of a given utterance, especially:

** In ...

. His fortune derived from his successful practice in chancery and other London courts. He briefly served as Lord Chief Justice

Lord is an appellation for a person or deity who has authority, control, or power over others, acting as a master, chief, or ruler. The appellation can also denote certain persons who hold a title of the peerage in the United Kingdom, or are ...

in 1625–26, but was dismissed by Charles I Charles I may refer to:

Kings and emperors

* Charlemagne (742–814), numbered Charles I in the lists of Holy Roman Emperors and French kings

* Charles I of Anjou (1226–1285), also king of Albania, Jerusalem, Naples and Sicily

* Charles I of ...

for his refusal to endorse a forced loan without the consent of parliament. He divided his enforced retirement between his London house and the Crewe estate. In 1615, he commenced building a substantial hall at Crewe,Pevsner & Hubbard, pp. 191–194 either adjacent to the old house, which was by then in disrepair, or after demolishing it.Chambers, pp. 14–15 He later wrote that "it hath pleased God of his abundant goodness to reduce the house and Mannor of the name to the name againe."

A few years after the hall's completion in 1636,

A few years after the hall's completion in 1636, Civil War

A civil war or intrastate war is a war between organized groups within the same state (or country).

The aim of one side may be to take control of the country or a region, to achieve independence for a region, or to change government polici ...

broke out. Like most of the legal families of Cheshire, the Crewe family was parliamentarian, and the hall was used as a garrison. In December 1643, royalist

A royalist supports a particular monarch as head of state for a particular kingdom, or of a particular dynastic claim. In the abstract, this position is royalism. It is distinct from monarchism, which advocates a monarchical system of gov ...

forces under the command of Lord Byron

George Gordon Byron, 6th Baron Byron (22 January 1788 – 19 April 1824), known simply as Lord Byron, was an English romantic poet and peer. He was one of the leading figures of the Romantic movement, and has been regarded as among the ...

occupied the area as they surrounded Nantwich, a major parliamentarian stronghold early in the First Civil War which lay some to the south west. A contemporary diarist, Edward Burghall, vicar of nearby Acton, described the subsequent action: "The royalists laid siege to Crewe Hall, where they within the house slew sixty, and wounded many, on St. John's Day; but wanting victuals and ammunition, they were forced to yield it up the next day, and themselves, a hundred and thirty-six, became prisoners, stout and valiant soldiers, having quarter for life granted them." On 4 February 1644, shortly after the decisive parliamentarian victory at the Battle of Nantwich, the hall was retaken by Sir Thomas Fairfax

Thomas Fairfax, 3rd Lord Fairfax of Cameron (17 January 161212 November 1671), also known as Sir Thomas Fairfax, was an English politician, general and Parliamentary commander-in-chief during the English Civil War. An adept and talented comman ...

's forces.

Sir Randolph Crewe died a couple of years later, before the end of the First Civil War. His male line died out in 1684, and the hall passed to the Offley family by the marriage of Sir Randolph's great-granddaughter, Anne Crewe, to John Offley of Madeley Old Manor

Madeley Old Manor (in the 14th century Madeley Castle), was a medieval fortified manor house in the parish of Madeley, Staffordshire. It is now a ruin, with only fragments of its walls remaining. The remnants have Grade II listed building status a ...

, Staffordshire. Their eldest son, also John (1681–1749), took the name Crewe in 1708.Burke J. ''A Genealogical and Heraldic Dictionary of the Peerage and Baronetage of the British Empire'' (Vol. 1), p. 310 (1832) Hall, S. C. ''The Baronial Halls, Picturesque Edifices, and Ancient Churches of England'' (Vol. III) (Chapman & Hall; 1845) The Offley–Crewe family was very wealthy at this time: John Offley Crewe's income at his death was estimated at £15,000 per year (£ today). Both John Offley Crewe and his son John Crewe (1709–1752) served as members of parliament for Cheshire

Cheshire ( ) is a ceremonial and historic county in North West England, bordered by Wales to the west, Merseyside and Greater Manchester to the north, Derbyshire to the east, and Staffordshire and Shropshire to the south. Cheshire's county tow ...

.Cruickshanks ''et al.'', pp. 3–4

Barons Crewe and Marquess of Crewe

Anne Crewe's great-grandson, John Crewe (1742–1829), was created the first

Anne Crewe's great-grandson, John Crewe (1742–1829), was created the first Baron Crewe

Baron Crewe, of Crewe in the County of Chester, was a title in the Peerage of the United Kingdom. It was created on 25 February 1806 for the politician and landowner John Crewe, of Crewe Hall, Cheshire. This branch of the Crewe (or Crew) family ...

in 1806. A prominent Whig politician, he was a lifelong friend and supporter of Charles James Fox

Charles James Fox (24 January 1749 – 13 September 1806), styled '' The Honourable'' from 1762, was a prominent British Whig statesman whose parliamentary career spanned 38 years of the late 18th and early 19th centuries. He was the arch-ri ...

; his wife Frances Crewe (née Greville; 1748–1818) was a famous beauty and political hostess who gave lavish entertainments at the hall. The Crewes' social circle included many of the major figures of the day, and visitors to the hall during this period included politicians Fox and George Canning

George Canning (11 April 17708 August 1827) was a British Tory statesman. He held various senior cabinet positions under numerous prime ministers, including two important terms as Foreign Secretary, finally becoming Prime Minister of the Uni ...

, philosopher Edmund Burke

Edmund Burke (; 12 January NS.html"_;"title="New_Style.html"_;"title="/nowiki>New_Style">NS">New_Style.html"_;"title="/nowiki>New_Style">NS/nowiki>_1729_–_9_July_1797)_was_an_NS.html"_;"title="New_Style.html"_;"title="/nowiki>New_Style">N ...

, playwright Richard Brinsley Sheridan

Richard Brinsley Butler Sheridan (30 October 17517 July 1816) was an Irish satirist, a politician, a playwright, poet, and long-term owner of the London Theatre Royal, Drury Lane. He is known for his plays such as '' The Rivals'', ''The ...

, poet William Spencer, musicologist Charles Burney

Charles Burney (7 April 1726 – 12 April 1814) was an English music historian, composer and musician. He was the father of the writers Frances Burney and Sarah Burney, of the explorer James Burney, and of Charles Burney, a classicist ...

, and artists Sir Joshua Reynolds and Sir Thomas Lawrence

Sir Thomas Lawrence (13 April 1769 – 7 January 1830) was an English portrait painter and the fourth president of the Royal Academy. A child prodigy, he was born in Bristol and began drawing in Devizes, where his father was an innkeeper at t ...

. John Crewe had the park landscaped and the hall extended, and also had the interior remodelled in the neo-Classical style then fashionable. Some forty years later, his grandson Hungerford Crewe (1812–94) went to considerable expense to have the interiors redecorated in a more sympathetic Jacobethan

The Jacobethan or Jacobean Revival architectural style is the mixed national Renaissance revival style that was made popular in England from the late 1820s, which derived most of its inspiration and its repertory from the English Renaissance ( ...

style.

The house was insured in 1857 for £10,000 (£ today); the contents at that time included books and wines (insured for £2,250), mathematical and musical instruments (£250), and pictures (£1,000). The art collection included several family portraits and other works by Sir Joshua Reynolds, which were saved from the fire that gutted the building early in January 1866. Extensive restoration work for Hungerford Crewe was completed in 1870.

Hungerford Crewe never married and on his death in 1894, the barony became extinct. The hall was inherited by his nephew, Robert Milnes, Baron Houghton (1858–1945), the son of Annabella Hungerford Crewe; he adopted the name Crewe, to become Crewe-Milnes. The Crewe title was revived as an earldom for him in 1895, and he later became the Marquess of Crewe. A Liberal politician and poet, Crewe-Milnes held several key Cabinet positions between 1905 and 1916, and was a trusted aide to

Hungerford Crewe never married and on his death in 1894, the barony became extinct. The hall was inherited by his nephew, Robert Milnes, Baron Houghton (1858–1945), the son of Annabella Hungerford Crewe; he adopted the name Crewe, to become Crewe-Milnes. The Crewe title was revived as an earldom for him in 1895, and he later became the Marquess of Crewe. A Liberal politician and poet, Crewe-Milnes held several key Cabinet positions between 1905 and 1916, and was a trusted aide to Asquith

Herbert Henry Asquith, 1st Earl of Oxford and Asquith, (12 September 1852 – 15 February 1928), generally known as H. H. Asquith, was a British statesman and Liberal Party (UK), Liberal Party politician who served as Prime Minister of ...

. He was also a friend of George V

George V (George Frederick Ernest Albert; 3 June 1865 – 20 January 1936) was King of the United Kingdom and the British Dominions, and Emperor of India, from 6 May 1910 until his death in 1936.

Born during the reign of his grandmother ...

, and the King and Queen Mary stayed at the hall for three days in 1913, while touring the Staffordshire Potteries

The Staffordshire Potteries is the industrial area encompassing the six towns Burslem, Fenton, Hanley, Longton, Stoke and Tunstall, which is now the city of Stoke-on-Trent in Staffordshire, England. North Staffordshire became a centre of ...

.

The Crewe-Milnes family left Crewe Hall in 1922, and the house stood empty until the Second World War

World War II or the Second World War, often abbreviated as WWII or WW2, was a world war that lasted from 1939 to 1945. It involved the vast majority of the world's countries—including all of the great powers—forming two opposi ...

. Crewe-Milnes offered the hall to Cheshire County Council

Cheshire County Council was the county council of Cheshire. Founded on 1 April 1889, it was officially dissolved on 31 March 2009, when it and its districts were superseded by two unitary authorities; Cheshire West and Chester and Cheshire East.

...

as a gift in 1931, ostensibly because his heirs did not wish to live in the house. After the council's refusal, the majority of the estate was sold to the Duchy of Lancaster

The Duchy of Lancaster is the private estate of the British sovereign as Duke of Lancaster. The principal purpose of the estate is to provide a source of independent income to the sovereign. The estate consists of a portfolio of lands, properti ...

in 1936. His grandson, writer Quentin Crewe, described Crewe-Milnes as "both extravagant and poorly advised".

Calmic, Wellcome and hotel

Early in theSecond World War

World War II or the Second World War, often abbreviated as WWII or WW2, was a world war that lasted from 1939 to 1945. It involved the vast majority of the world's countries—including all of the great powers—forming two opposi ...

, Crewe Hall was used as a military training camp, repatriation camp for Dunkirk

Dunkirk (french: Dunkerque ; vls, label=French Flemish, Duunkerke; nl, Duinkerke(n) ; , ;) is a commune in the department of Nord in northern France.

troops and a US army camp, becoming the gun operations headquarters for the north-west region in 1942. It housed a prisoner-of-war camp

A prisoner-of-war camp (often abbreviated as POW camp) is a site for the containment of enemy fighters captured by a belligerent power in time of war.

There are significant differences among POW camps, internment camps, and military prisons. ...

for German officers from 1943.Giese, O., 1994, Shooting the War, Annapolis: United States Naval Institute, Ollerhead, p. 60 The hall was leased as offices in 1946, becoming the headquarters of Calmic Limited (the company's name is an abbreviation of Cheshire and Lancashire Medical Industries Corporation), which moved from Lancashire to Crewe Hall in 1947. They eventually employed nearly 800 people at Crewe Hall.Tigwell, p. 55 Calmic produced hygiene and medical products on the site including tablets, creams, analgesic

An analgesic drug, also called simply an analgesic (American English), analgaesic (British English), pain reliever, or painkiller, is any member of the group of drugs used to achieve relief from pain (that is, analgesia or pain management). It ...

s and antibiotic aerosols; the company's brands included Calpol (launched in 1959 with the brand name likely a combination of 'Calmic' and 'paracetamol

Paracetamol, also known as acetaminophen, is a medication used to treat fever and mild to moderate pain. Common brand names include Tylenol and Panadol.

At a standard dose, paracetamol only slightly decreases body temperature; it is inferio ...

'). Calmic constructed industrial facilities adjacent to the hall including a drying and filtration plant and pharmaceutical packaging unit. After Wellcome's acquisition of Calmic in 1965, the hall served as the UK and Ireland headquarters of the Wellcome Foundation until the merger with Glaxo in 1995. Wellcome produced liquids, tablets, creams and antibiotic aerosols at the site; the hall itself was used for administration, but the stables block was rebuilt internally for use as laboratories and the industrial facilities were expanded.

In 1994, the Duchy of Lancaster sold the Crewe Hall buildings and the adjacent industrial site, which became Crewe Hall Enterprise Park. The Crewe Hall buildings remained empty after Wellcome moved out and were sold to a hotel developer in 1998; the hall became a 26-bedroom hotel the following year. Several additional buildings in a modern style were constructed in the 21st century to extend the accommodation.

Architectural history

The Jacobean hall was built for Sir Randolph Crewe between 1615 and 1636. The architect of the original building is unknown, although some historians have concluded that its design was based on drawings by

The Jacobean hall was built for Sir Randolph Crewe between 1615 and 1636. The architect of the original building is unknown, although some historians have concluded that its design was based on drawings by Inigo Jones

Inigo Jones (; 15 July 1573 – 21 June 1652) was the first significant architect in England and Wales in the early modern period, and the first to employ Vitruvian rules of proportion and symmetry in his buildings.

As the most notable archit ...

.Urban, p. 313 Although of a relatively conservative design, similar to that of Longleat

Longleat is an English stately home and the seat of the Marquess of Bath, Marquesses of Bath. A leading and early example of the Elizabethan era, Elizabethan prodigy house, it is adjacent to the village of Horningsham and near the towns of War ...

from half a century earlier, the hall seems to have been considered progressive in provincial Cheshire. The historian Thomas Fuller

Thomas Fuller (baptised 19 June 1608 – 16 August 1661) was an English churchman and historian. He is now remembered for his writings, particularly his ''Worthies of England'', published in 1662, after his death. He was a prolific author, and ...

wrote in 1662:

Hearth-tax assessments of 1674 show the original hall to have been one of the largest houses in Cheshire, its 42 hearths being surpassed only by Cholmondeley House and

Hearth-tax assessments of 1674 show the original hall to have been one of the largest houses in Cheshire, its 42 hearths being surpassed only by Cholmondeley House and Rocksavage

Rocksavage or Rock Savage was an Elizabethan mansion, which served as the primary seat of the Savage family. The house now lies in ruins, at in Clifton (now a district of Runcorn), Cheshire, England. Built for Sir John Savage, MP in 1565–15 ...

, neither of which have survived. As depicted in a painting of around 1710, the original building was square with sides of around , and featured gabled projecting bays and groups of octagonal chimney stacks. Built around a central open courtyard, the interior had a great hall and long gallery; the main entrance led to a screens passage and the main staircase was in a small east hall.Hodson, p. 77 Externally, there was a walled forecourt and formal walled gardens; a range of separate service buildings was located to the west.Moss, pp. 346–348

Georgian and Jacobethan alterations

The house remained unaltered for much of the 18th century, in contrast to most of the other principal seats in the county.Hodson, pp. 80–81 It was described in 1769 as "a square of very old date ... more to be admired now for its antiquity than elegance or conveniency." Work was carried out during the 1780s and '90s for John Crewe (later the first Baron Crewe). A service wing to the west in a Jacobean revival style was added to the hall in 1780. The principal interiors of the old building were redecorated in neo-Classical style at this time, although the original layout with great hall, long gallery and drawing room was retained. Improvements were made to the wine cellars and bedrooms in 1783, and J. Cheney was employed to build a new attic staircase and seven bedrooms in 1796.

The house remained unaltered for much of the 18th century, in contrast to most of the other principal seats in the county.Hodson, pp. 80–81 It was described in 1769 as "a square of very old date ... more to be admired now for its antiquity than elegance or conveniency." Work was carried out during the 1780s and '90s for John Crewe (later the first Baron Crewe). A service wing to the west in a Jacobean revival style was added to the hall in 1780. The principal interiors of the old building were redecorated in neo-Classical style at this time, although the original layout with great hall, long gallery and drawing room was retained. Improvements were made to the wine cellars and bedrooms in 1783, and J. Cheney was employed to build a new attic staircase and seven bedrooms in 1796. Edmund Burke

Edmund Burke (; 12 January NS.html"_;"title="New_Style.html"_;"title="/nowiki>New_Style">NS">New_Style.html"_;"title="/nowiki>New_Style">NS/nowiki>_1729_–_9_July_1797)_was_an_NS.html"_;"title="New_Style.html"_;"title="/nowiki>New_Style">N ...

wrote in 1788, "I am vastly pleased with this place. We build no such houses in our time." The second Lord Palmerston, visiting in the same year, wrote:

The house was altered again in 1837–42 by Edward Blore

Edward Blore (13 September 1787 – 4 September 1879) was a 19th-century English landscape and architectural artist, architect and antiquary.

Early career

He was born in Derby, the son of the antiquarian writer Thomas Blore.

Blore's back ...

for Hungerford Crewe. Blore replaced a local architect, George Latham, who had been commissioned in 1836. Many of Blore's working drawings survive in the Royal Institute of British Architects

The Royal Institute of British Architects (RIBA) is a professional body for architects primarily in the United Kingdom, but also internationally, founded for the advancement of architecture under its royal charter granted in 1837, three supp ...

archive. He carried out decorative work to the interior in the Jacobethan

The Jacobethan or Jacobean Revival architectural style is the mixed national Renaissance revival style that was made popular in England from the late 1820s, which derived most of its inspiration and its repertory from the English Renaissance ( ...

style and made major changes to the plan of the ground floor, which included replacing the screens passage with an entrance hall and covering the central courtyard to create a single-storey central hall. He also fitted plate glass windows throughout and installed a warm-air heating system.Scard, p. 23 The total cost, including his work on estate buildings, was £30,000 (£ today).

E. M. Barry restoration

Most of Blore's work to the main hall was destroyed in the fire of 1866. Hungerford Crewe is said to have asked Blore, then retired, to restore the building, but he declined. The restoration work was instead carried out byE. M. Barry

Edward Middleton Barry RA (7 June 1830 – 27 January 1880) was an English architect of the 19th century.

Biography

Edward Barry was the third son of Sir Charles Barry, born in his father's house, 27 Foley Place, London. In infancy he was ...

, son of Sir Charles Barry

Sir Charles Barry (23 May 1795 – 12 May 1860) was a British architect, best known for his role in the rebuilding of the Palace of Westminster (also known as the Houses of Parliament) in London during the mid-19th century, but also respon ...

, the architect of the Palace of Westminster

The Palace of Westminster serves as the meeting place for both the House of Commons and the House of Lords, the two houses of the Parliament of the United Kingdom. Informally known as the Houses of Parliament, the Palace lies on the north b ...

, and the contractors Cubitt & Co.;Gladden, p.29 it was completed in 1870, at a cost of £150,000 (£ today). In a lecture to the Royal Academy

The Royal Academy of Arts (RA) is an art institution based in Burlington House on Piccadilly in London. Founded in 1768, it has a unique position as an independent, privately funded institution led by eminent artists and architects. Its pur ...

, Barry later outlined his strategy for the restoration:

Nikolaus Pevsner

Sir Nikolaus Bernhard Leon Pevsner (30 January 1902 – 18 August 1983) was a German-British art historian and architectural historian best known for his monumental 46-volume series of county-by-county guides, '' The Buildings of England'' ...

describes Barry's reconstruction as "an extremely sumptuous job."Pevsner & Hubbard, p. 40 Peter de Figueiredo and Julian Treuherz consider it his finest work, attributing his success to being "directed by the powerful character of the existing building." Barry's work is considered to be, in general, more elaborate and more regular than the original. For the restoration of the interior, he employed several of the leading artists and craftsmen of the time, who had previously worked on the Palace of Westminster. Barry's principal innovation was the addition of a tower to the west wing, which was required for water storage. Intended to unite the east and west wings of the hall, the effect is limited by the tower's Victorian design. He also reorganised the plan of the building, opening up Blore's central hall to create a two-storey atrium, as well as providing more ground-floor service rooms and generating twenty extra servants' bedrooms in an attic by modifying the roof.

Local architect Thomas Bower performed some alterations to the house for Robert Crewe-Milnes in 1896, including extending the service wing. Few changes to the hall itself occurred during Calmic's tenancy. The company installed central heating in around 1948, and later constructed an office extension on the north side of the house, which was demolished a few years after the building's conversion into an hotel. Calmic had undertaken only cosmetic maintenance work, and by the 1970s the fabric of the building was in poor repair. A major stonework fall from the north gable during high winds in 1974 led Wellcome

Wellcome () is a supermarket chain owned by British conglomerate Jardine Matheson Holdings via its DFI Retail Group subsidiary. The Wellcome supermarket chain is one of the two largest supermarket chains in Hong Kong, the other being Park ...

to carry out an extensive restoration programme to both the interior and the exterior, which was completed in 1979 at a cost of £500,000 (£ today).

Main hall

Crewe Hall is a grade-I-listed mansion located at in the civil parish of Crewe Green, ½ mile (1 km) from the edge of

Crewe Hall is a grade-I-listed mansion located at in the civil parish of Crewe Green, ½ mile (1 km) from the edge of Crewe

Crewe () is a railway town and civil parish in the unitary authority of Cheshire East in Cheshire, England. The Crewe built-up area had a total population of 75,556 in 2011, which also covers parts of the adjacent civil parishes of Willaston ...

. The architecture historian Nikolaus Pevsner considered the main hall to be one of the two finest Jacobean houses in Cheshire

Cheshire ( ) is a ceremonial and historic county in North West England, bordered by Wales to the west, Merseyside and Greater Manchester to the north, Derbyshire to the east, and Staffordshire and Shropshire to the south. Cheshire's county tow ...

, the other being Dorfold Hall at Acton. Constructed in red brick with stone dressings and a lead and slate roof, the hall has two storeys with attics and basements. The eastern half of the present building largely represents the original Jacobean hall. The exterior survived the fire of 1866 and the majority of the diapered brickwork is original, although some of the stonework of the porch

A porch (from Old French ''porche'', from Latin ''porticus'' "colonnade", from ''porta'' "passage") is a room or gallery located in front of an entrance of a building. A porch is placed in front of the facade of a building it commands, and form ...

and the tops of the gable

A gable is the generally triangular portion of a wall between the edges of intersecting roof pitches. The shape of the gable and how it is detailed depends on the structural system used, which reflects climate, material availability, and aest ...

s was renewed by E. M. Barry

Edward Middleton Barry RA (7 June 1830 – 27 January 1880) was an English architect of the 19th century.

Biography

Edward Barry was the third son of Sir Charles Barry, born in his father's house, 27 Foley Place, London. In infancy he was ...

.Robinson, pp. 25–26

The south (front) face of the eastern wing has seven bays

A bay is a recessed, coastal body of water that directly connects to a larger main body of water, such as an ocean, a lake, or another bay. A large bay is usually called a gulf, sea, sound, or bight. A cove is a small, circular bay with a na ...

, with a balustraded parapet

A parapet is a barrier that is an extension of the wall at the edge of a roof, terrace, balcony, walkway or other structure. The word comes ultimately from the Italian ''parapetto'' (''parare'' 'to cover/defend' and ''petto'' 'chest/breast'). ...

at eaves

The eaves are the edges of the roof which overhang the face of a wall and, normally, project beyond the side of a building. The eaves form an overhang to throw water clear of the walls and may be highly decorated as part of an architectural styl ...

level. The central bay is set forward to form a stone centrepiece around the arched main entrance, which is flanked by fluted Ionic columns. Immediately above the entrance are doubled tapering pilaster

In classical architecture, a pilaster is an architectural element used to give the appearance of a supporting column and to articulate an extent of wall, with only an ornamental function. It consists of a flat surface raised from the main wal ...

s flanking a three-light window, all surmounted by a large cartouche

In Egyptian hieroglyphs, a cartouche is an oval with a line at one end tangent to it, indicating that the text enclosed is a royal name. The first examples of the cartouche are associated with pharaohs at the end of the Third Dynasty, but the f ...

decorated with strapwork. On the first floor of the central bay is a triple-mullion

A mullion is a vertical element that forms a division between units of a window or screen, or is used decoratively. It is also often used as a division between double doors. When dividing adjacent window units its primary purpose is a rigid sup ...

window, and above the parapet is a coat of arms

A coat of arms is a heraldic visual design on an escutcheon (i.e., shield), surcoat, or tabard (the latter two being outer garments). The coat of arms on an escutcheon forms the central element of the full heraldic achievement, which in its ...

. Flanking the centrepiece are two bays with diapered brickwork and single-mullion windows. The two ends of the south face are also set forward; they have canted, triple-mullion bay window

A bay window is a window space projecting outward from the main walls of a building and forming a bay in a room.

Types

Bay window is a generic term for all protruding window constructions, regardless of whether they are curved or angular, or ...

s and are surmounted above the parapet by shaped gables with attic windows. All the main windows of this face are double transomed.

The east face of the eastern wing has four bays with canted bay windows, shaped end gables and a central cartouche. In the centre of the northern (garden) face is a large

The east face of the eastern wing has four bays with canted bay windows, shaped end gables and a central cartouche. In the centre of the northern (garden) face is a large bow window

A bow window or compass window is a curved bay window. Bow windows are designed to create space by projecting beyond the exterior wall of a building, and to provide a wider view of the garden or street outside and typically combine four or more w ...

, originally Jacobean, which illuminates the chapel; it has stone panels decorated with cartouches below arched stained glass

Stained glass is coloured glass as a material or works created from it. Throughout its thousand-year history, the term has been applied almost exclusively to the windows of churches and other significant religious buildings. Although tradition ...

lights.Pevsner & Hubbard, p. 23 This face otherwise reverses the main façade

A façade () (also written facade) is generally the front part or exterior of a building. It is a loan word from the French (), which means ' frontage' or ' face'.

In architecture, the façade of a building is often the most important aspect ...

, with the addition of mezzanine

A mezzanine (; or in Italian, a ''mezzanino'') is an intermediate floor in a building which is partly open to the double-height ceilinged floor below, or which does not extend over the whole floorspace of the building, a loft with non-sloped ...

windows.

The western half of the building is stepped forward (southwards) by two bays from the original building. Originally the service wing, it is plainer than the eastern building and dates from the Georgian era. Though using Georgian proportions, it was built in an early Jacobean revival style which has been heightened by subsequent alterations, particularly the addition of a central gable. The main part of the south (front) face has seven bays, with a balustraded parapet running along the entire façade at eaves level. In the centre of the five east bays is a canted bay window beneath a shaped gable; the flanking bays have single-mullion, double-transomed windows. The two west bays are set backwards and have a central oriel window on the first floor with two single-mullion, double-transomed windows on the ground floor.

The western wing is dominated by a square tower of stone-dressed brick which rises two storeys above the roof and is capped by an ogee

An ogee ( ) is the name given to objects, elements, and curves—often seen in architecture and building trades—that have been variously described as serpentine-, extended S-, or sigmoid-shaped. Ogees consist of a "double curve", the combinat ...

spirelet surrounded by four corner chimneys. Designed by Barry in the High Victorian style, it was added after the fire. A slender bell tower also rises from the west wing. At the rear is a loggia

In architecture, a loggia ( , usually , ) is a covered exterior gallery or corridor, usually on an upper level, but sometimes on the ground level of a building. The outer wall is open to the elements, usually supported by a series of columns ...

with a vaulted ceiling supported by Tuscan columns. The western end of this wing is a single-storey extension by Thomas Bower dating from 1896.

Interior

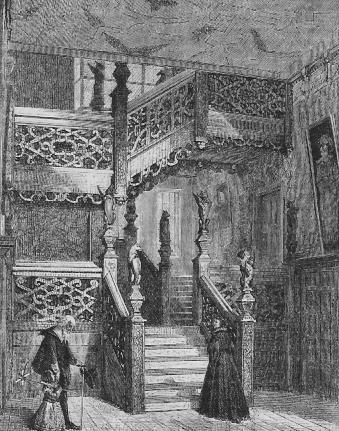

The interior of Crewe Hall contains a mixture of original Jacobean work, faithful reproductions of the original Jacobean designs (which in some cases had been recorded), and work in the High Victorian style designed by Barry. The entrance hall in the east wing was remodelled by both

The interior of Crewe Hall contains a mixture of original Jacobean work, faithful reproductions of the original Jacobean designs (which in some cases had been recorded), and work in the High Victorian style designed by Barry. The entrance hall in the east wing was remodelled by both Edward Blore

Edward Blore (13 September 1787 – 4 September 1879) was a 19th-century English landscape and architectural artist, architect and antiquary.

Early career

He was born in Derby, the son of the antiquarian writer Thomas Blore.

Blore's back ...

and Barry. It is panelled in oak and contains a marble chimneypiece with Tuscan columns featuring the Crewe arms. It opens via a columned screen into the central hall, which was an open courtyard

A courtyard or court is a circumscribed area, often surrounded by a building or complex, that is open to the sky.

Courtyards are common elements in both Western and Eastern building patterns and have been used by both ancient and contemporary ...

in the Jacobean house. Roofed by Blore at the first-floor level, Barry converted the space into an atrium featuring cloister

A cloister (from Latin ''claustrum'', "enclosure") is a covered walk, open gallery, or open arcade running along the walls of buildings and forming a quadrangle or garth. The attachment of a cloister to a cathedral or church, commonly against ...

s around the walls, with a wooden gallery over them at the mezzanine level and a tunnel-vaulted first-floor gallery above. The floor is paved with a pattern of coloured marbles and the first-floor gallery corridors have stained glass panels. The atrium has a hammerbeam roof

A hammerbeam roof is a decorative, open timber roof truss typical of English Gothic architecture and has been called "...the most spectacular endeavour of the English Medieval carpenter". They are traditionally timber framed, using short beams ...

supported by columns at the gallery level. To the east of the central hall is an accurate reconstruction by Barry of the original staircase, which Nikolaus Pevsner described as "one of the most ingeniously planned and ornately executed in the whole of Jacobean England." Heavily carved, the newel

A newel, also called a central pole or support column, is the central supporting pillar of a staircase. It can also refer to an upright post that supports and/or terminates the handrail of a stair banister (the "newel post"). In stairs having str ...

s feature heraldic animals, which were originally gilded

Gilding is a decorative technique for applying a very thin coating of gold over solid surfaces such as metal (most common), wood, porcelain, or stone. A gilded object is also described as "gilt". Where metal is gilded, the metal below was tradi ...

and painted.

To the east of the entrance lies the dining room, which was formerly the Jacobean

To the east of the entrance lies the dining room, which was formerly the Jacobean great hall

A great hall is the main room of a royal palace, castle or a large manor house or hall house in the Middle Ages, and continued to be built in the country houses of the 16th and early 17th centuries, although by then the family used the gr ...

. The room least damaged by the fire, it was restored by Barry to its 17th-century appearance, with facsimiles of the original ceiling and carved wooden screen. It contains an overmantel

The fireplace mantel or mantelpiece, also known as a chimneypiece, originated in medieval times as a hood that projected over a fire grate to catch the smoke. The term has evolved to include the decorative framework around the fireplace, and ca ...

featuring a relief

Relief is a sculptural method in which the sculpted pieces are bonded to a solid background of the same material. The term '' relief'' is from the Latin verb ''relevo'', to raise. To create a sculpture in relief is to give the impression that th ...

of Plenty, considered to be original, and a large stone chimneypiece, which is believed to be the only surviving work by Blore on the interior. The oak parlour, in the south west, contains a large wooden Jacobean overmantel, featuring Green Men carving. The Jacobean carving here and in the dining room is noticeably cruder than the Victorian work. The carved parlour is another reproduction by Barry of the original. Panelled in oak, it has a plaster frieze

In architecture, the frieze is the wide central section part of an entablature and may be plain in the Ionic or Doric order, or decorated with bas-reliefs. Paterae are also usually used to decorate friezes. Even when neither columns nor ...

of the Elements, Graces

In Greek mythology, the Charites ( ), singular ''Charis'', or Graces, were three or more goddesses of charm, beauty, nature, human creativity, goodwill, and fertility. Hesiod names three – Aglaea ("Shining"), Euphrosyne ("Joy"), and Thali ...

and Virtues

Virtue ( la, virtus) is moral excellence. A virtue is a trait or quality that is deemed to be morally good and thus is valued as a foundation of principle and good moral being. In other words, it is a behavior that shows high moral standard ...

. The alabaster chimneypiece depicts the winged figure of Time

Time is the continued sequence of existence and event (philosophy), events that occurs in an apparently irreversible process, irreversible succession from the past, through the present, into the future. It is a component quantity of various me ...

rewarding Industry and punishing Sloth

Sloths are a group of Neotropical xenarthran mammals constituting the suborder Folivora, including the extant arboreal tree sloths and extinct terrestrial ground sloths. Noted for their slowness of movement, tree sloths spend most of their l ...

, symbolised by two boys, which is surmounted by a carved portrait of Sir Randolph Crewe.

A small chapel lies to the north of the central hall. Originally rather austere, it was lavishly decorated by Barry in the High Victorian style. There is much elaborate wood carving, with the altar rail

The altar rail (also known as a communion rail or chancel rail) is a low barrier, sometimes ornate and usually made of stone, wood or metal in some combination, delimiting the chancel or the sanctuary and altar in a church, from the nave and ot ...

featuring angels and the benches poppyheads. The marble apse

In architecture, an apse (plural apses; from Latin 'arch, vault' from Ancient Greek 'arch'; sometimes written apsis, plural apsides) is a semicircular recess covered with a hemispherical vault or semi-dome, also known as an '' exedra''. ...

has alabaster carved heads of the prophets

In religion, a prophet or prophetess is an individual who is regarded as being in contact with a divine being and is said to speak on behalf of that being, serving as an intermediary with humanity by delivering messages or teachings from the s ...

and evangelists

Evangelists may refer to:

* Evangelists (Christianity), Christians who specialize in evangelism

* Four Evangelists, the authors of the four Gospel accounts in the New Testament

* ''The Evangelists

''The Evangelists'' (''Evangheliştii'' in Roma ...

by J. Birnie Philip, and the wall panelling features bronze medallions depicting biblical characters by the same artist. The ornate choir gallery, reached from the central hall's mezzanine gallery, contains the family pew. The stained glass and wall mural

A mural is any piece of graphic artwork that is painted or applied directly to a wall, ceiling or other permanent substrate. Mural techniques include fresco, mosaic, graffiti and marouflage.

Word mural in art

The word ''mural'' is a Spanis ...

s are by Clayton and Bell

Clayton and Bell was one of the most prolific and proficient British workshops of stained-glass windows during the latter half of the 19th century and early 20th century. The partners were John Richard Clayton (1827–1913) and Alfred Bell (1832 ...

, and the painting and stencil

Stencilling produces an image or pattern on a surface, by applying pigment to a surface through an intermediate object, with designed holes in the intermediate object, to create a pattern or image on a surface, by allowing the pigment to reach ...

ling are by J. G. Crace

John Gregory Crace (26 May 1809 – 13 August 1889) was a British interior decorator and author.

Early life and education

The Crace family had been prominent London interior decorators since Edward Crace (1725–1799), later keeper of the roya ...

.

The suite of

The suite of state room

A state room in a large European mansion is usually one of a suite of very grand rooms which were designed for use when entertaining royalty. The term was most widely used in the 17th and 18th centuries. They were the most lavishly decorated in ...

s on the first floor of the east wing contains the long gallery

In architecture, a long gallery is a long, narrow room, often with a high ceiling. In Britain, long galleries were popular in Elizabethan and Jacobean houses. They were normally placed on the highest reception floor of English country hous ...

, library, drawing room ( great chamber), small drawing room and two bedrooms. All date originally from the Jacobean mansion, but are likely to have been significantly altered by John Crewe and then extensively reworked by Blore in neo-Jacobean style. They were restored to Barry's designs, usually with little attempt to reproduce the Jacobean appearance, probably because records of most of the original designs were lacking. Crace performed much of the decoration work in these rooms. All the state rooms contain elaborate plasterwork and stone chimneypieces, often flanked with Corinthian columns or pilasters.

The long gallery, along the north side, has a chimneypiece in coloured marbles with busts by

The long gallery, along the north side, has a chimneypiece in coloured marbles with busts by Henry Weekes

Henry Weekes (14 January 1807 – 28 May 1877) was an English sculptor, best known for his portraiture. He was among the most successful British sculptors of the mid- Victorian period.

Personal life

Weekes was born at Canterbury, Kent, to Capo ...

depicting Sir Randolph Crewe and Nathaniel Crew, 3rd Baron Crew

Nathaniel Crew, 3rd Baron Crew (31 January 163318 September 1721) was Bishop of Oxford from 1671 to 1674, then Bishop of Durham from 1674 to 1721. As such he was one of the longest-serving bishops of the Church of England.

Crew was the son of Jo ...

, Bishop of Durham

The Bishop of Durham is the Anglican bishop responsible for the Diocese of Durham in the Province of York. The diocese is one of the oldest in England and its bishop is a member of the House of Lords. Paul Butler has been the Bishop of Durham ...

. The library, above the carved parlour, contains statuettes of book lovers by Philip and a frieze of scenes from literature by J. Mabey. The drawing room has a facsimile of the Jacobean ceiling, which had been recorded by architect William Burn

William Burn (20 December 1789 – 15 February 1870) was a Scottish architect. He received major commissions from the age of 20 until his death at 81. He built in many styles and was a pioneer of the Scottish Baronial Revival,often referred ...

. Identical in pattern to one at the Reindeer Inn in Banbury

Banbury is a historic market town on the River Cherwell in Oxfordshire, South East England. It had a population of 54,335 at the 2021 Census.

Banbury is a significant commercial and retail centre for the surrounding area of north Oxfordshir ...

, of which the Victoria and Albert Museum

The Victoria and Albert Museum (often abbreviated as the V&A) in London is the world's largest museum of applied arts, decorative arts and design, housing a permanent collection of over 2.27 million objects. It was founded in 1852 and nam ...

has a plaster cast, it was presumably originally the work of the same craftsman. One of the state bedrooms has another survivor of the fire, a Jacobean stone fireplace with a plaster overmantel relief depicting Cain and Abel

In the biblical Book of Genesis, Cain ''Qayīn'', in pausa ''Qāyīn''; gr, Κάϊν ''Káïn''; ar, قابيل/قايين, Qābīl / Qāyīn and Abel ''Heḇel'', in pausa ''Hāḇel''; gr, Ἅβελ ''Hábel''; ar, هابيل, Hābīl ...

.

Stables, outbuildings and gate lodges

The former stables, in red brick with a tiled roof, were completed around 1636 and are contemporary with the Jacobean mansion; they are listed at

The former stables, in red brick with a tiled roof, were completed around 1636 and are contemporary with the Jacobean mansion; they are listed at grade II*

In the United Kingdom, a listed building or listed structure is one that has been placed on one of the four statutory lists maintained by Historic England in England, Historic Environment Scotland in Scotland, in Wales, and the Northern Irel ...

. They form a quadrangle immediately to the west of the hall, enclosing a rectangular courtyard. The main east face of the quadrangle stands at right angles to the front of the house; it has nine bays of two storeys and an attic. Its centrepiece, added by Edward Blore

Edward Blore (13 September 1787 – 4 September 1879) was a 19th-century English landscape and architectural artist, architect and antiquary.

Early career

He was born in Derby, the son of the antiquarian writer Thomas Blore.

Blore's back ...

in around 1837, consists of an arched stone entrance flanked by pilasters, above which a clock tower rises from the first-floor level.Pevsner & Hubbard, pp. 194–195 The tower features twinned arrow-slit windows and clock faces with stone surrounds, and is topped by a bell chamber and ogee

An ogee ( ) is the name given to objects, elements, and curves—often seen in architecture and building trades—that have been variously described as serpentine-, extended S-, or sigmoid-shaped. Ogees consist of a "double curve", the combinat ...

cupola

In architecture, a cupola () is a relatively small, most often dome-like, tall structure on top of a building. Often used to provide a lookout or to admit light and air, it usually crowns a larger roof or dome.

The word derives, via Italian, f ...

with finial

A finial (from '' la, finis'', end) or hip-knob is an element marking the top or end of some object, often formed to be a decorative feature.

In architecture, it is a small decorative device, employed to emphasize the apex of a dome, spire, towe ...

s. In addition to the centrepiece, the east face has four bays which are set forward and have shaped gables topped with finials. The north and south ends of this east building also have shaped gables.

The north and south sides of the quadrangle have large arched carriage openings beneath shaped gables; the keystones are carved with horse's heads. The walls within the carriageway opening are decorated with bands of blue brick. The east, north and south faces are all finished with an openwork brick parapet with a stone coping. The west building has twelve arched openings accessed from the courtyard. The main storeys of the quadrangle mainly have three-light, stone-dressed

The north and south sides of the quadrangle have large arched carriage openings beneath shaped gables; the keystones are carved with horse's heads. The walls within the carriageway opening are decorated with bands of blue brick. The east, north and south faces are all finished with an openwork brick parapet with a stone coping. The west building has twelve arched openings accessed from the courtyard. The main storeys of the quadrangle mainly have three-light, stone-dressed mullion

A mullion is a vertical element that forms a division between units of a window or screen, or is used decoratively. It is also often used as a division between double doors. When dividing adjacent window units its primary purpose is a rigid sup ...

windows, with two-light windows at the attic level. All the roofs have tall octagonal chimneys and feature decorative ridge tiles. The interior of the stables block was rebuilt during the building's conversion to its present use of laboratories and offices.

The Apple House, a small red-brick building to the west of the stables quadrangle, also dates from around 1636, and can be seen in a painting of Crewe Hall from around 1710. Originally a dovecote

A dovecote or dovecot , doocot ( Scots) or columbarium is a structure intended to house pigeons or doves. Dovecotes may be free-standing structures in a variety of shapes, or built into the end of a house or barn. They generally contain pige ...

, it is used as a storehouse. Built on an octagonal plan with two storeys, it has two oval windows with stone surrounds. The lower entrance has a stone semicircular arch; a second doorway is located at first-floor height. The pyramidal tiled roof is topped by a glazed lantern with a lead cap. The building is listed at grade II.

The park has two gate lodges; both are listed at grade II. The northern lodge at Slaughter Hill is by Blore and dates from 1847. In red brick with darker-brick diapering, stone dressings and a slate roof, it has a T-shaped plan with a single storey, and is Jacobean in style. It features two shaped gables, each decorated with a panel carved with Crewe Estate emblems, and a hexagonal central bay with a pyramidal roof which forms a porch. The

The park has two gate lodges; both are listed at grade II. The northern lodge at Slaughter Hill is by Blore and dates from 1847. In red brick with darker-brick diapering, stone dressings and a slate roof, it has a T-shaped plan with a single storey, and is Jacobean in style. It features two shaped gables, each decorated with a panel carved with Crewe Estate emblems, and a hexagonal central bay with a pyramidal roof which forms a porch. The Elizabethan

The Elizabethan era is the epoch in the Tudor period of the history of England during the reign of Queen Elizabeth I (1558–1603). Historians often depict it as the golden age in English history. The symbol of Britannia (a female personific ...

-style Weston or Golden Gates Lodge to the south of the house dates from before 1865 and is attributed to William Eden Nesfield, although it is not typical of his style. In red brick with blue-brick zig–zag diapering, ashlar

Ashlar () is finely dressed (cut, worked) stone, either an individual stone that has been worked until squared, or a structure built from such stones. Ashlar is the finest stone masonry unit, generally rectangular cuboid, mentioned by Vitruv ...

dressings and a slate roof, the lodge has two storeys, with a projecting canted bay to the road face. The driveway face has an ashlar panel with a shield bearing the Crewe family coat of arms

A coat of arms is a heraldic visual design on an escutcheon (i.e., shield), surcoat, or tabard (the latter two being outer garments). The coat of arms on an escutcheon forms the central element of the full heraldic achievement, which in its ...

.

Gardens and park

The

The National Register of Historic Parks and Gardens

The Register of Historic Parks and Gardens of Special Historic Interest in England provides a listing and classification system for historic parks and gardens similar to that used for listed buildings. The register is managed by Historic England ...

lists of the gardens and surrounding parkland at grade II. An early engraving shows a walled forecourt to the south of the original hall, with a large stone gateway carved with Sir Randolph Crewe's arms and motto. The forecourt had terraces, balustrades and a path decorated with diamond patterns. As depicted in a painting of around 1710, the grounds were laid out in extensive formal walled pleasure gardens with parterre

A ''parterre'' is a part of a formal garden constructed on a level substrate, consisting of symmetrical patterns, made up by plant beds, low hedges or coloured gravels, which are separated and connected by paths. Typically it was the part of ...

s.

During the 18th century, the park was landscaped in a more naturalistic style for John Crewe (later the first Baron Crewe) by Lancelot Brown

Lancelot Brown (born c. 1715–16, baptised 30 August 1716 – 6 February 1783), more commonly known as Capability Brown, was an English gardener and landscape architect, who remains the most famous figure in the history of the English lan ...

(before 1768), William Emes

William Emes (1729 or 1730–13 March 1803) was an English landscape gardener.

Biography

Details of his early life are not known but in 1756 he was appointed head gardener to Sir Nathaniel Curzon at Kedleston Hall, Derbyshire. He left this post ...

(1768–71), and Humphry Repton

Humphry Repton (21 April 1752 – 24 March 1818) was the last great English landscape designer of the eighteenth century, often regarded as the successor to Capability Brown; he also sowed the seeds of the more intricate and eclectic styles of ...

and John Webb (1791).Gladden, p. 28 Repton's design included an ornamental lake of immediately north of the house, created by damming Engelsea Brook, which still runs through the park. He also created new approaches to the house. The lake drained away in 1941 when a dam burst, and the area is now planted with poplars

''Populus'' is a genus of 25–30 species of deciduous flowering plants in the family Salicaceae, native to most of the Northern Hemisphere. English names variously applied to different species include poplar (), aspen, and cottonwood.

The w ...

. A stone statue of Neptune

Neptune is the eighth planet from the Sun and the farthest known planet in the Solar System. It is the fourth-largest planet in the Solar System by diameter, the third-most-massive planet, and the densest giant planet. It is 17 time ...

with a reclining female, originally located on the banks of the lake, now stands in woodland; it dates from the early 19th century. A boathouse

A boathouse (or a boat house) is a building especially designed for the storage of boats, normally smaller craft for sports or leisure use. describing the facilities These are typically located on open water, such as on a river. Often the boats ...

, originally at the head of the lake, was in need of restoration in 2007. A Temple of Peace formerly stood on the north shore of the lake, but was demolished some time after 1892. Much of the parkland is now covered with mixed woodland, including Rookery Wood and Temple of Peace Wood.

Formal gardens were laid out around the house by W. A. Nesfield in around 1840–50 for Hungerford Crewe. Nesfield's design included statuary, gravelled walks and elaborate parterres realised using low box hedges and coloured minerals. Balustraded terraces were also constructed on the north and south sides of the hall, probably designed by

Formal gardens were laid out around the house by W. A. Nesfield in around 1840–50 for Hungerford Crewe. Nesfield's design included statuary, gravelled walks and elaborate parterres realised using low box hedges and coloured minerals. Balustraded terraces were also constructed on the north and south sides of the hall, probably designed by E. M. Barry

Edward Middleton Barry RA (7 June 1830 – 27 January 1880) was an English architect of the 19th century.

Biography

Edward Barry was the third son of Sir Charles Barry, born in his father's house, 27 Foley Place, London. In infancy he was ...

, and incorporating statues of lions, griffin

The griffin, griffon, or gryphon ( Ancient Greek: , ''gryps''; Classical Latin: ''grȳps'' or ''grȳpus''; Late and Medieval Latin: ''gryphes'', ''grypho'' etc.; Old French: ''griffon'') is a legendary creature with the body, tail, and ...

s and other heraldic beasts, echoing the interior staircase. Military usage during the Second World War

World War II or the Second World War, often abbreviated as WWII or WW2, was a world war that lasted from 1939 to 1945. It involved the vast majority of the world's countries—including all of the great powers—forming two opposi ...

, however, destroyed parts of the gardens; army buildings were erected near the house, and the area in front of the hall served as a parade ground and later was ploughed up to grow potatoes. The grounds were further neglected while the house was used as offices, and little has survived except the terraces, gates and statues. In 2009, English Heritage

English Heritage (officially the English Heritage Trust) is a charity that manages over 400 historic monuments, buildings and places. These include prehistoric sites, medieval castles, Roman forts and country houses.

The charity states that i ...

placed the hall on the ''Heritage at Risk Register'' as highly vulnerable, considering that the historic character of the gardens and park is compromised by recent developments to the hotel complex, in particular the conference centre, spa and associated parking area.

The entrance gates and wall separating the gardens from the park and farmland date from 1878 and are listed at grade II. The wrought-iron gates are by Cubitt & Co., and were exhibited at the Paris Exhibition of 1878. Two outer single gates and a double inner gate are supported by four sandstone

The entrance gates and wall separating the gardens from the park and farmland date from 1878 and are listed at grade II. The wrought-iron gates are by Cubitt & Co., and were exhibited at the Paris Exhibition of 1878. Two outer single gates and a double inner gate are supported by four sandstone piers Piers may refer to:

* Pier, a raised structure over a body of water

* Pier (architecture), an architectural support

* Piers (name), a given name and surname (including lists of people with the name)

* Piers baronets, two titles, in the baronetages ...

. The outer pair of gate piers are capped by a bud-shaped device supported on scrolls; the inner pair are surmounted by a griffin and a lion, mirroring the statuary of the hall's terraces. The lower gate sections of lyre

The lyre () is a string instrument, stringed musical instrument that is classified by Hornbostel–Sachs as a member of the History of lute-family instruments, lute-family of instruments. In organology, a lyre is considered a yoke lute, since it ...

-like panels with leaf and spearhead motifs are topped with Jacobean-style arched panels. The ornate gate overthrows include shields and emblems capped with crowns, sheaves and sickles. The inner gates bear the inscription ''Quid retribuam domino'' ("What can I render to the Lord?"), while the outer gates bear the date. The wall, of brick with stone dressings, features arcading and has piers surmounted with ogee

An ogee ( ) is the name given to objects, elements, and curves—often seen in architecture and building trades—that have been variously described as serpentine-, extended S-, or sigmoid-shaped. Ogees consist of a "double curve", the combinat ...

caps carved to match the tiles of the main hall tower. A further feature of the gardens to survive is a grade-II-listed sundial

A sundial is a horological device that tells the time of day (referred to as civil time in modern usage) when direct sunlight shines by the apparent position of the Sun in the sky. In the narrowest sense of the word, it consists of a f ...