Crenelation on:

[Wikipedia]

[Google]

[Amazon]

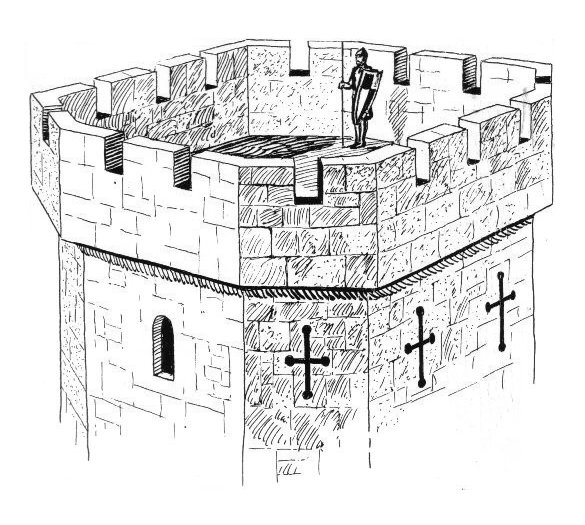

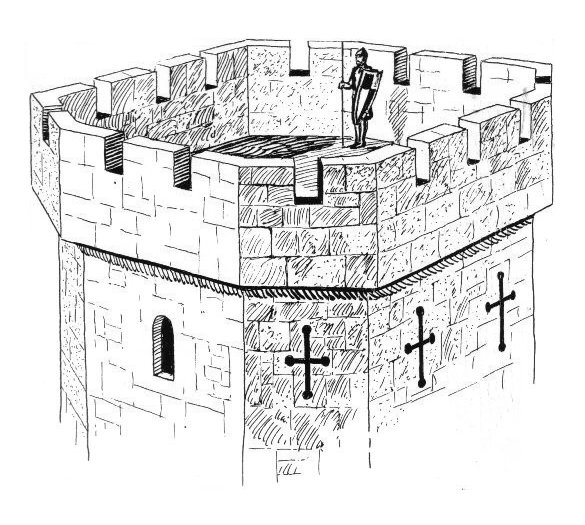

A battlement in defensive architecture, such as that of

A battlement in defensive architecture, such as that of

In the European battlements of the

In the European battlements of the

Loop-holes were frequent in Italian battlements, where the merlon has much greater height and a distinctive cap. Italian military architects used the so-called

Loop-holes were frequent in Italian battlements, where the merlon has much greater height and a distinctive cap. Italian military architects used the so-called

File:Rohtas Fort Gate.jpg, alt=, Rohtas Fort, Pakistan

File:ইদ্রাকপুর দুর্গ 05.jpg, alt=, Idrakpur Fort, Bangladesh

File:St. Munnas Church Taghmon County Westmeath.JPG, alt=,

city wall

A defensive wall is a fortification usually used to protect a city, town or other settlement from potential aggressors. The walls can range from simple palisades or earthworks to extensive military fortifications with towers, bastions and gates ...

s or castle

A castle is a type of fortified structure built during the Middle Ages predominantly by the nobility or royalty and by military orders. Scholars debate the scope of the word ''castle'', but usually consider it to be the private fortified r ...

s, comprises a parapet

A parapet is a barrier that is an extension of the wall at the edge of a roof, terrace, balcony, walkway or other structure. The word comes ultimately from the Italian ''parapetto'' (''parare'' 'to cover/defend' and ''petto'' 'chest/breast'). Whe ...

(i.e., a defensive low wall between chest-height and head-height), in which gaps or indentations, which are often rectangular, occur at intervals to allow for the launch of arrows or other projectiles from within the defences. These gaps are termed " crenels" (also known as ''carnels'', or ''embrasures

An embrasure (or crenel or crenelle; sometimes called gunhole in the domain of gunpowder-era architecture) is the opening in a battlement between two raised solid portions ( merlons). Alternatively, an embrasure can be a space hollowed ou ...

''), and a wall or building with them is called crenellated; alternative (older) terms are castellated and embattled. The act of adding crenels to a previously unbroken parapet is termed crenellation.

The function of battlements in war is to protect the defenders by giving them something to hide behind, from which they can pop out to launch their own missiles. A defensive building might be designed and built with battlements, or a manor house

A manor house was historically the main residence of the lord of the manor. The house formed the administrative centre of a manor in the European feudal system; within its great hall were held the lord's manorial courts, communal meals w ...

might be fortified by adding battlements, where no parapet previously existed, or cutting crenellations into its existing parapet wall. A distinctive feature of late medieval English church architecture is to crenellate the tops of church towers, and often the tops of lower walls. These are essentially decorative rather than functional, as are many examples on secular buildings.

The solid widths between the crenels are called merlon

A merlon is the solid upright section of a battlement (a crenellated parapet) in medieval architecture or fortifications.Friar, Stephen (2003). ''The Sutton Companion to Castles'', Sutton Publishing, Stroud, 2003, p. 202. Merlons are sometimes ...

s. Battlements on walls have protected walkways (''chemin de ronde

A ''chemin de ronde'' (French, "round path"' or "patrol path"; ), also called an allure, alure or, more prosaically, a wall-walk, is a raised protected walkway behind a castle battlement.

In early fortifications, high castle walls were difficul ...

'') behind them. On tower or building tops, the (often flat) roof is used as the protected fighting platform

A fighting platform or terraceKaufmann, J.E. and Kaufmann, H.W (2001). ''The Medieval Fortress'', Cambridge, Massachusetts, Da Capo, p. 29. . is the uppermost defensive platform of an ancient or medieval gateway, tower (such as the fighting platfor ...

.

Etymology

The term originated in about the 14th century from theOld French

Old French (, , ; Modern French: ) was the language spoken in most of the northern half of France from approximately the 8th to the 14th centuries. Rather than a unified language, Old French was a linkage of Romance dialects, mutually intelligib ...

word ', "to fortify with ''batailles''" (fixed or movable turrets of defence). The word ''crenel'' derives from the ancient French ''cren'' (modern French ''cran''), Latin ''crena'', meaning a notch, mortice or other gap cut out often to receive another element or fixing; see also crenation

Crenation (from modern Latin ''crenatus'' meaning "scalloped or notched", from popular Latin ''crena'' meaning "notch") in botany and zoology, describes an object's shape, especially a leaf or shell, as being round-toothed or having a scalloped ed ...

. The modern French word for crenel is ''créneau'', also used to describe a gap of any kind, for example a parking space at the side of the road between two cars, interval between groups of marching troops or a timeslot in a broadcast.

Licence to crenellate

In medieval England and Wales a licence to crenellate granted the holder permission to fortify their property. Such licences were granted by the king, and by the rulers of the counties palatine within their jurisdictions, e.g. by theBishops of Durham

The Bishop of Durham is the Anglican bishop responsible for the Diocese of Durham in the Province of York. The diocese is one of the oldest in England and its bishop is a member of the House of Lords. Paul Butler has been the Bishop of Durham ...

and the Earls of Chester

The Earldom of Chester was one of the most powerful earldoms in medieval England, extending principally over the counties of Cheshire and Flintshire. Since 1301 the title has generally been granted to heirs apparent to the English throne, and ...

and after 1351 by the Dukes of Lancaster

The Dukedom of Lancaster is an English peerage merged into the crown. It was created three times in the Middle Ages, but finally merged in the Crown when Henry V succeeded to the throne in 1413. Despite the extinction of the dukedom the title ...

. The castles in England vastly outnumbered the licences to crenellate. Royal pardons were obtainable on the payment of an arbitrarily-determined fine by a person who had fortified without licence. The surviving records of such licences, generally issued by letters patent

Letters patent ( la, litterae patentes) ( always in the plural) are a type of legal instrument in the form of a published written order issued by a monarch, president or other head of state, generally granting an office, right, monopoly, titl ...

, provide valuable evidence for the dating of ancient buildings. A list of licences issued by the English Crown between the 12th and the 16th centuries was compiled by Turner & Parker and expanded and corrected by Philip Davis and published in ''The Castle Studies Group Journal''.

There has been academic debate over the purpose of licensing. The view of military-focused historians is that licensing restricted the number of fortifications that could be used against a royal army. The modern view, proposed notably by Charles Coulson, is that battlements became an architectural status-symbol much sought after by the socially ambitious, in Coulson's words: "Licences to crenellate were mainly symbolic representations of lordly status: castellation was the architectural expression of noble rank". They indicated to the observer that the grantee had obtained "royal recognition, acknowledgment and compliment". They could, however, provide a basic deterrent against wandering bands of thieves, and it is suggested that the function of battlements was comparable to the modern practice of householders fitting highly visible CC

TV and burglar alarms, often merely dummies. The crown usually did not charge for the granting of such licences, but occasionally charged a fee of about half a mark

Mark may refer to:

Currency

* Bosnia and Herzegovina convertible mark, the currency of Bosnia and Herzegovina

* East German mark, the currency of the German Democratic Republic

* Estonian mark, the currency of Estonia between 1918 and 1927

* Fi ...

.

Machicolations

Battlements may be stepped out to overhang the wall below, and may have openings at their bases between the supportingcorbel

In architecture, a corbel is a structural piece of stone, wood or metal jutting from a wall to carry a superincumbent weight, a type of bracket. A corbel is a solid piece of material in the wall, whereas a console is a piece applied to the s ...

s, through which stones or burning objects could be dropped onto attackers or besiegers; these are known as machicolation

A machicolation (french: mâchicoulis) is a floor opening between the supporting corbels of a battlement, through which stones or other material, such as boiling water, hot sand, quicklime or boiling cooking oil, could be dropped on attackers at t ...

s.

History

Battlements have been used for thousands of years; the earliest known example is in the fortress atBuhen

Buhen ( grc, Βοὥν ''Bohón'') was an ancient Egyptian settlement situated on the West bank of the Nile below (to the North of) the Second Cataract in what is now Northern State, Sudan.

It is now submerged in Lake Nasser, Sudan; as a resul ...

in Egypt

Egypt ( ar, مصر , ), officially the Arab Republic of Egypt, is a transcontinental country spanning the northeast corner of Africa and southwest corner of Asia via a land bridge formed by the Sinai Peninsula. It is bordered by the Mediter ...

. Battlements were used in the walls surrounding Assyria

Assyria (Neo-Assyrian cuneiform: , romanized: ''māt Aššur''; syc, ܐܬܘܪ, ʾāthor) was a major ancient Mesopotamian civilization which existed as a city-state at times controlling regional territories in the indigenous lands of the A ...

n towns, as shown on ''bas relief

Relief is a sculptural method in which the sculpted pieces are bonded to a solid background of the same material. The term ''relief'' is from the Latin verb ''relevo'', to raise. To create a sculpture in relief is to give the impression that the ...

s'' from Nimrud

Nimrud (; syr, ܢܢܡܪܕ ar, النمرود) is an ancient Assyrian city located in Iraq, south of the city of Mosul, and south of the village of Selamiyah ( ar, السلامية), in the Nineveh Plains in Upper Mesopotamia. It was a majo ...

and elsewhere. Traces of them remain at Mycenae

Mycenae ( ; grc, Μυκῆναι or , ''Mykē̂nai'' or ''Mykḗnē'') is an archaeological site near Mykines in Argolis, north-eastern Peloponnese, Greece. It is located about south-west of Athens; north of Argos; and south of Corinth. Th ...

in Greece

Greece,, or , romanized: ', officially the Hellenic Republic, is a country in Southeast Europe. It is situated on the southern tip of the Balkans, and is located at the crossroads of Europe, Asia, and Africa. Greece shares land borders with ...

, and some ancient Greek

Ancient Greek includes the forms of the Greek language used in ancient Greece and the ancient world from around 1500 BC to 300 BC. It is often roughly divided into the following periods: Mycenaean Greek (), Dark Ages (), the Archaic peri ...

vases suggest the existence of battlements. The Great Wall of China

The Great Wall of China (, literally "ten thousand ''li'' wall") is a series of fortifications that were built across the historical northern borders of ancient Chinese states and Imperial China as protection against various nomadic grou ...

has battlements.

Development

In the European battlements of the

In the European battlements of the Middle Ages

In the history of Europe, the Middle Ages or medieval period lasted approximately from the late 5th to the late 15th centuries, similar to the post-classical period of global history. It began with the fall of the Western Roman Empire a ...

the crenel comprised one-third of the width of the merlon: the latter, in addition, could be provided with arrow-loops of various shapes (from simply round to cruciform), depending on the weapon being utilized. Late merlons permitted fire from the first firearm

A firearm is any type of gun designed to be readily carried and used by an individual. The term is legally defined further in different countries (see Legal definitions).

The first firearms originated in 10th-century China, when bamboo tubes ...

s. From the 13th century, the merlons could be connected with wooden shutters (mantlet

A mantlet was a portable wall or shelter used for stopping projectiles in medieval warfare. It could be mounted on a wheeled carriage, and protected one or several soldiers.

In the First World War a mantlet type of device was used by the French ...

s) that provided added protection when closed. The shutters were designed to be opened to allow shooters to fire against the attackers, and closed during reloading.

Ancient Rome

TheRomans

Roman or Romans most often refers to:

*Rome, the capital city of Italy

* Ancient Rome, Roman civilization from 8th century BC to 5th century AD

*Roman people, the people of ancient Rome

*''Epistle to the Romans'', shortened to ''Romans'', a lette ...

used low wooden pinnacles for their first ''aggeres'' (terreplein

In fortification architecture, a terreplein or terre-plein is the top, platform, or horizontal surface of a rampart, on which cannon are placed,''Webster's International Dictionary of the English Language'', Vol 2, 1895 protected by a parapet. In ...

s). In the battlements of Pompeii

Pompeii (, ) was an ancient city located in what is now the ''comune'' of Pompei near Naples in the Campania region of Italy. Pompeii, along with Herculaneum and many villas in the surrounding area (e.g. at Boscoreale, Stabiae), was buried ...

, additional protection derived from small internal buttresses or spur walls, against which the defender might stand so as to gain complete protection on one side.

Italy

Loop-holes were frequent in Italian battlements, where the merlon has much greater height and a distinctive cap. Italian military architects used the so-called

Loop-holes were frequent in Italian battlements, where the merlon has much greater height and a distinctive cap. Italian military architects used the so-called Ghibelline

The Guelphs and Ghibellines (, , ; it, guelfi e ghibellini ) were factions supporting the Pope and the Holy Roman Emperor, respectively, in the Italian city-states of Central Italy and Northern Italy.

During the 12th and 13th centuries, rival ...

or ''swallowtail'' battlement, with V-shaped notches in the tops of the merlon, giving a horn-like effect. This would allow the defender to be protected whilst shooting standing fully upright. The normal rectangular merlons were later nicknamed Guelph.

Indian subcontinent

Many South Asian battlements are made up of parapets with peculiarly shapedmerlons

A merlon is the solid upright section of a battlement (a crenellated parapet) in medieval architecture or fortifications.Friar, Stephen (2003). ''The Sutton Companion to Castles'', Sutton Publishing, Stroud, 2003, p. 202. Merlons are sometimes ...

and complicated systems of loopholes, which differ substantially from rest of the world. Typical Indian merlons were semicircular and pointed at the top, although they could sometimes be fake: the parapet may be solid and the merlons shown in relief on the outside, as is the case in Chittorgarh

Chittorgarh (also Chittor or Chittaurgarh) is a major city in Rajasthan state of western India. It lies on the Berach River, a tributary of the Banas, and is the administrative headquarters of Chittorgarh District. It was a major stronghol ...

. Loopholes could be made both in the merlons themselves, and under the crenels. They could either look forward (to command distant approaches) or downward (to command the foot of the wall). Sometimes a merion was pierced with two or three loopholes, but typically, only one loophole was divided into two or three slits by horizontal or vertical partitions. The shape of loopholes, as well as the shape of merlons, need not have been the same everywhere in the castle, as shown by Kumbhalgarh

Kumbhalgarh (literally "Kumbhal fort") also known as the Great Wall of India is a Mewar fortress on the westerly range of Aravalli Hills, just about 48 km from Rajsamand city in the Rajsamand district of the Rajasthan state in western India. I ...

.

Middle East and Africa

InMuslim

Muslims ( ar, المسلمون, , ) are people who adhere to Islam, a monotheistic religion belonging to the Abrahamic tradition. They consider the Quran, the foundational religious text of Islam, to be the verbatim word of the God of Abrah ...

and Africa

Africa is the world's second-largest and second-most populous continent, after Asia in both cases. At about 30.3 million km2 (11.7 million square miles) including adjacent islands, it covers 6% of Earth's total surface area ...

n fortifications, the merlons often were rounded. The battlements of the Arabs

The Arabs (singular: Arab; singular ar, عَرَبِيٌّ, DIN 31635: , , plural ar, عَرَب, DIN 31635, DIN 31635: , Arabic pronunciation: ), also known as the Arab people, are an ethnic group mainly inhabiting the Arab world in Wester ...

had a more decorative and varied character, and were continued from the 13th century onwards not so much for defensive purposes as for a crowning feature to the walls. They serve a function similar to the cresting found in the Spanish Renaissance architecture

Spanish Renaissance architecture was that style of Renaissance architecture in the last decades of the 15th century. Renaissance evolved firstly in Florence and then Rome and other parts of the Italian Peninsula as the result of Renaissance huma ...

.

Ireland

"Irish" crenellations are a distinctive form that appeared inIreland

Ireland ( ; ga, Éire ; Ulster Scots dialect, Ulster-Scots: ) is an island in the Atlantic Ocean, North Atlantic Ocean, in Northwestern Europe, north-western Europe. It is separated from Great Britain to its east by the North Channel (Grea ...

between the 14th and 17th centuries. These were battlements of a "stepped" form, with each merlon shaped like an inverted 'T'.

Decorative element

European architects persistently used battlements as a purely decorative feature throughout the Decorated andPerpendicular

In elementary geometry, two geometric objects are perpendicular if they intersect at a right angle (90 degrees or π/2 radians). The condition of perpendicularity may be represented graphically using the ''perpendicular symbol'', ⟂. It can ...

periods of Gothic architecture. They not only occur on parapets but on the transoms of windows and on the tie-beams of roofs and on screens, and even on Tudor chimney-pots. A further decorative treatment appears in the elaborate paneling of the merlons and that portion of the parapet walls rising above the cornice

In architecture, a cornice (from the Italian ''cornice'' meaning "ledge") is generally any horizontal decorative moulding that crowns a building or furniture element—for example, the cornice over a door or window, around the top edge of a ...

, by the introduction of quatrefoil

A quatrefoil (anciently caterfoil) is a decorative element consisting of a symmetrical shape which forms the overall outline of four partially overlapping circles of the same diameter. It is found in art, architecture, heraldry and traditional ...

s and other conventional forms filled with foliage and shield.

Gallery

Taghmon Church

Taghmon Church () is a fortified church and National Monument in County Westmeath, Ireland.

Location

Taghmon Church is located east of Crookedwood, southeast of Lough Derravaragh.

History

A monastery was established on the site in the 7th ...

in County Westmeath

"Noble above nobility"

, image_map = Island of Ireland location map Westmeath.svg

, subdivision_type = Sovereign state, Country

, subdivision_name = Republic of Ireland, Ireland

, subdivision_type1 = Provinces o ...

, Ireland, with Irish crenellations

Notes

Sources

* * * * *Further reading

* Coulson, Charles, 1979, "Structural Symbolism in Medieval Castle Architecture" Journal of the British Archaeological Association Vol. 132, pp 73–90 * Coulson, Charles, 1994, "Freedom to Crenellate by Licence - An Historiographical Revision" Nottingham Medieval Studies Vol. 38, pp. 86–137 * Coulson, Charles, 1995, "Battlements and the Bourgeoisie: Municipal Status and the Apparatus of Urban Defence" in Church, Stephen (ed), Medieval Knighthood Vol. 5(Boydell), pp. 119–95 * Coulson, Charles, 2003, ''Castles in Medieval Society'', Oxford University Press. * Coulson, Charles, ''Castles in the Medieval Polity - Crenellation, Privilege, and Defence in England, Ireland and Wales''. * King, D. J. Cathcart, 1983, ''Castellarium Anglicanum'' (Kraus) {{fortifications Castle architecture Types of wall