Cosmo Gordon Lang on:

[Wikipedia]

[Google]

[Amazon]

William Cosmo Gordon Lang, 1st Baron Lang of Lambeth, (31 October 1864 – 5 December 1945) was a Scottish

Cosmo Gordon Lang was born in 1864 at the

Cosmo Gordon Lang was born in 1864 at the

Lang started at Balliol in October 1882. In his first term he successfully sat for the Brackenbury Scholarship, described by his biographer John Gilbert Lockhart as "the Blue Ribbon of history scholarship at any University of the British Isles".Lockhart, pp. 28–29 In February 1883 his first speech at the

Lang started at Balliol in October 1882. In his first term he successfully sat for the Brackenbury Scholarship, described by his biographer John Gilbert Lockhart as "the Blue Ribbon of history scholarship at any University of the British Isles".Lockhart, pp. 28–29 In February 1883 his first speech at the

Lang's career ambition from early in life was to practise law, enter politics and then take office in some future Conservative administration. In 1887 he began his studies for the English Bar, working in the London chambers of W.S. Robson, a future

Lang's career ambition from early in life was to practise law, enter politics and then take office in some future Conservative administration. In 1887 he began his studies for the English Bar, working in the London chambers of W.S. Robson, a future

When war broke out in August 1914, Lang concluded that the conflict was righteous, and that younger clergy should be encouraged to serve as military chaplains, although it was not their duty to fight. He thereafter was active in recruiting campaigns throughout his province. At a meeting in York in November 1914 he caused offence when he spoke out against excessive anti-German propaganda, and recalled a "sacred memory" of the

When war broke out in August 1914, Lang concluded that the conflict was righteous, and that younger clergy should be encouraged to serve as military chaplains, although it was not their duty to fight. He thereafter was active in recruiting campaigns throughout his province. At a meeting in York in November 1914 he caused offence when he spoke out against excessive anti-German propaganda, and recalled a "sacred memory" of the

During 1941 Lang considered retirement. His main concern was that a Lambeth Conference – "perhaps the most fateful Lambeth Conference ever held" – would need to be called soon after the war. Lang felt that he would be too old to lead it and that he should make way for a younger man, preferably William Temple. On 27 November he informed the prime minister, Winston Churchill, of his decision to retire on 31 March 1942. His last official act in office, on 28 March, was the confirmation of Princess Elizabeth.

On his retirement Lang was raised to the

During 1941 Lang considered retirement. His main concern was that a Lambeth Conference – "perhaps the most fateful Lambeth Conference ever held" – would need to be called soon after the war. Lang felt that he would be too old to lead it and that he should make way for a younger man, preferably William Temple. On 27 November he informed the prime minister, Winston Churchill, of his decision to retire on 31 March 1942. His last official act in office, on 28 March, was the confirmation of Princess Elizabeth.

On his retirement Lang was raised to the  On 5 December 1945 Lang was due to speak in a Lords debate on conditions in Central Europe. On his way to Kew Gardens station to catch the London train, he collapsed and was taken to hospital, but was found to be dead on arrival. A post-mortem attributed the death to heart failure. In paying tribute the following day, Lord Addison said that Lang was "not only a great cleric but a great man... we have lost in him a Father in God." His body was cremated and the ashes taken to the Chapel of St Stephen Martyr, a side chapel at

On 5 December 1945 Lang was due to speak in a Lords debate on conditions in Central Europe. On his way to Kew Gardens station to catch the London train, he collapsed and was taken to hospital, but was found to be dead on arrival. A post-mortem attributed the death to heart failure. In paying tribute the following day, Lord Addison said that Lang was "not only a great cleric but a great man... we have lost in him a Father in God." His body was cremated and the ashes taken to the Chapel of St Stephen Martyr, a side chapel at

Bibliographic directory

from

Archives of Cosmo Gordon Lang at Lambeth Palace Library

* , - {{DEFAULTSORT:Lang, Cosmo Alumni of Ripon College Cuddesdon 1864 births 1945 deaths 19th-century English Anglican priests 20th-century Anglican archbishops Archbishops of Canterbury Archbishops of York Bishops of Stepney Anglo-Scots Bailiffs Grand Cross of the Order of St John Lang of Lambeth, Cosmo Lang, 1st Baron People from Banff and Buchan Alumni of Balliol College, Oxford Alumni of the University of Glasgow Members of the Privy Council of the United Kingdom People from Formartine Burials at Canterbury Cathedral Anglo-Catholic bishops British Anglo-Catholics Presidents of the Oxford Union City of London Yeomanry (Rough Riders) officers Barons created by George VI 19th-century Anglican theologians 20th-century Anglican theologians

Anglican

Anglicanism is a Western Christian tradition that has developed from the practices, liturgy, and identity of the Church of England following the English Reformation, in the context of the Protestant Reformation in Europe. It is one of the ...

prelate

A prelate () is a high-ranking member of the Christian clergy who is an ordinary or who ranks in precedence with ordinaries. The word derives from the Latin , the past participle of , which means 'carry before', 'be set above or over' or 'pref ...

who served as Archbishop of York

The archbishop of York is a senior bishop in the Church of England, second only to the archbishop of Canterbury. The archbishop is the diocesan bishop of the Diocese of York and the metropolitan bishop of the province of York, which covers th ...

(1908–1928) and Archbishop of Canterbury

The archbishop of Canterbury is the senior bishop and a principal leader of the Church of England, the ceremonial head of the worldwide Anglican Communion and the diocesan bishop of the Diocese of Canterbury. The current archbishop is Jus ...

(1928–1942). His elevation to Archbishop of York, within 18 years of his ordination

Ordination is the process by which individuals are consecrated, that is, set apart and elevated from the laity class to the clergy, who are thus then authorized (usually by the denominational hierarchy composed of other clergy) to perform v ...

, was the most rapid in modern Church of England history. As Archbishop of Canterbury during the abdication crisis

In early December 1936, a constitutional crisis in the British Empire arose when King-Emperor Edward VIII proposed to marry Wallis Simpson, an American socialite who was divorced from her first husband and was pursuing the divorce of her secon ...

of 1936, he took a strong moral stance, his comments in a subsequent broadcast being widely condemned as uncharitable towards the departed king.

The son of a Scots Presbyterian

Presbyterianism is a part of the Reformed tradition within Protestantism that broke from the Roman Catholic Church in Scotland by John Knox, who was a priest at St. Giles Cathedral (Church of Scotland). Presbyterian churches derive their na ...

minister, Lang abandoned the prospect of a legal and political career to train for the Anglican priesthood. Beginning in 1890, his early ministry was served in slum parishes in Leeds

Leeds () is a city and the administrative centre of the City of Leeds district in West Yorkshire, England. It is built around the River Aire and is in the eastern foothills of the Pennines. It is also the third-largest settlement (by populati ...

and Portsmouth

Portsmouth ( ) is a port and city in the ceremonial county of Hampshire in southern England. The city of Portsmouth has been a unitary authority since 1 April 1997 and is administered by Portsmouth City Council.

Portsmouth is the most dense ...

, except for brief service as Vicar of the University Church of St Mary the Virgin

The University Church of St Mary the Virgin (St Mary's or SMV for short) is an Oxford church situated on the north side of the High Street. It is the centre from which the University of Oxford grew and its parish consists almost exclusively of un ...

in Oxford. In 1901 he was appointed suffragan

A suffragan bishop is a type of bishop in some Christian denominations.

In the Anglican Communion, a suffragan bishop is a bishop who is subordinate to a metropolitan bishop or diocesan bishop (bishop ordinary) and so is not normally jurisdiction ...

Bishop of Stepney

The Bishop of Stepney is an episcopal title used by a suffragan bishop of the Church of England Diocese of London, in the Province of Canterbury, England. The title takes its name after Stepney, an inner-city district in the London Borough of To ...

in London, where he continued his work among the poor. He also served as a canon

Canon or Canons may refer to:

Arts and entertainment

* Canon (fiction), the conceptual material accepted as official in a fictional universe by its fan base

* Literary canon, an accepted body of works considered as high culture

** Western can ...

of St Paul's Cathedral

St Paul's Cathedral is an Anglican cathedral in London and is the seat of the Bishop of London. The cathedral serves as the mother church of the Diocese of London. It is on Ludgate Hill at the highest point of the City of London and is a G ...

, London.

In 1908 Lang was nominated as Archbishop of York, despite his relatively junior status as a suffragan rather than a diocesan bishop. His religious stance was broadly Anglo-Catholic

Anglo-Catholicism comprises beliefs and practices that emphasise the Catholic heritage and identity of the various Anglican churches.

The term was coined in the early 19th century, although movements emphasising the Catholic nature of Anglican ...

, tempered by the liberal Anglo-Catholicism

The terms liberal Anglo-Catholicism, liberal Anglo-Catholic or simply Liberal Catholic, refer to people, beliefs and practices within Anglicanism that affirm liberal Christian perspectives while maintaining the traditions culturally associated wit ...

advocated in the '' Lux Mundi'' essays. He consequently entered the House of Lords

The House of Lords, also known as the House of Peers, is the upper house of the Parliament of the United Kingdom. Membership is by appointment, heredity or official function. Like the House of Commons, it meets in the Palace of Westminster in ...

as a Lord Spiritual

The Lords Spiritual are the bishops of the Church of England who serve in the House of Lords of the United Kingdom. 26 out of the 42 diocesan bishops and archbishops of the Church of England serve as Lords Spiritual (not counting retired archbi ...

and caused consternation in traditionalist circles by speaking and voting against the Lords' proposal to reject David Lloyd George

David Lloyd George, 1st Earl Lloyd-George of Dwyfor, (17 January 1863 – 26 March 1945) was Prime Minister of the United Kingdom from 1916 to 1922. He was a Liberal Party politician from Wales, known for leading the United Kingdom during ...

's 1909 "People's Budget

The 1909/1910 People's Budget was a proposal of the Liberal government that introduced unprecedented taxes on the lands and incomes of Britain's wealthy to fund new social welfare programmes. It passed the House of Commons in 1909 but was blo ...

". This radicalism was not maintained in subsequent years. At the start of the First World War, Lang was heavily criticised for a speech in which he spoke sympathetically of the German Emperor

The German Emperor (german: Deutscher Kaiser, ) was the official title of the head of state and hereditary ruler of the German Empire. A specifically chosen term, it was introduced with the 1 January 1871 constitution and lasted until the offi ...

. This troubled him greatly and may have contributed to the rapid ageing which affected his appearance during the war years. After the war he began to promote church unity and at the 1920 Lambeth Conference

The Lambeth Conference is a decennial assembly of bishops of the Anglican Communion convened by the Archbishop of Canterbury. The first such conference took place at Lambeth in 1867.

As the Anglican Communion is an international association ...

was responsible for the Church's Appeal to All Christian People. As Archbishop of York he supported controversial proposals for the 1928 revision of the Book of Common Prayer

The ''Book of Common Prayer'' (BCP) is the name given to a number of related prayer books used in the Anglican Communion and by other Christian churches historically related to Anglicanism. The original book, published in 1549 in the reign ...

but, after acceding to Canterbury, he took no practical steps to resolve this issue.

Lang became Archbishop of Canterbury in 1928. He presided over the 1930 Lambeth Conference, which gave limited church approval to the use of contraception. After denouncing the Italian invasion of Abyssinia in 1935

The Second Italo-Ethiopian War, also referred to as the Second Italo-Abyssinian War, was a war of aggression which was fought between Italy and Ethiopia from October 1935 to February 1937. In Ethiopia it is often referred to simply as the Itali ...

and strongly condemning European antisemitism, Lang later supported the appeasement

Appeasement in an international context is a diplomatic policy of making political, material, or territorial concessions to an aggressive power in order to avoid conflict. The term is most often applied to the foreign policy of the UK governm ...

policies of the British government. In May 1937 he presided over the coronation of King George VI and Queen Elizabeth

The coronation of George VI and his wife, Elizabeth, as King and Queen of the United Kingdom and the Dominions of the British Commonwealth, and as Emperor and Empress of India took place at Westminster Abbey, London, on Wednesday 12 May 1937 ...

. On retirement in 1942 Lang was raised to the peerage as Baron Lang of Lambeth and continued to attend and speak in House of Lords debates until his death in 1945. Lang himself believed that he had not lived up to his own high standards. Others have praised his qualities of industry, his efficiency and his commitment to his calling.

Early life

Childhood and family

Cosmo Gordon Lang was born in 1864 at the

Cosmo Gordon Lang was born in 1864 at the manse

A manse () is a clergy house inhabited by, or formerly inhabited by, a minister, usually used in the context of Presbyterian, Methodist, Baptist and other Christian traditions.

Ultimately derived from the Latin ''mansus'', "dwelling", from '' ...

in Fyvie

Fyvie is a village in the Formartine area of Aberdeenshire, Scotland.

Geography

Fyvie lies alongside the River Ythan and is on the A947 road.

Architecture

What in 1990, at least, was a Clydesdale Bank was built in 1866 by James Matthews. ...

, Aberdeenshire

Aberdeenshire ( sco, Aiberdeenshire; gd, Siorrachd Obar Dheathain) is one of the 32 council areas of Scotland.

It takes its name from the County of Aberdeen which has substantially different boundaries. The Aberdeenshire Council area includ ...

, the third son of the local Church of Scotland minister, John Marshall Lang, and his wife Hannah Agnes Lang. ("Early Life" section) Cosmo was baptised at Fyvie church by a neighbouring minister, the name "William" being added inadvertently to his given names, perhaps because the local laird

Laird () is the owner of a large, long-established Scottish estate. In the traditional Scottish order of precedence, a laird ranked below a baron and above a gentleman. This rank was held only by those lairds holding official recognition in a ...

was called William Cosmo Gordon. The additional name was rarely used subsequently.Lockhart, pp. 6–8 In January 1865 the family moved to Glasgow

Glasgow ( ; sco, Glesca or ; gd, Glaschu ) is the most populous city in Scotland and the fourth-most populous city in the United Kingdom, as well as being the 27th largest city by population in Europe. In 2020, it had an estimated pop ...

on John Lang's appointment as a minister in the Anderston

Anderston ( sco, Anderstoun, gd, Baile Aindrea) is an area of Glasgow, Scotland. It is on the north bank of the River Clyde and forms the south western edge of the city centre. Established as a village of handloom weavers in the early 18th cen ...

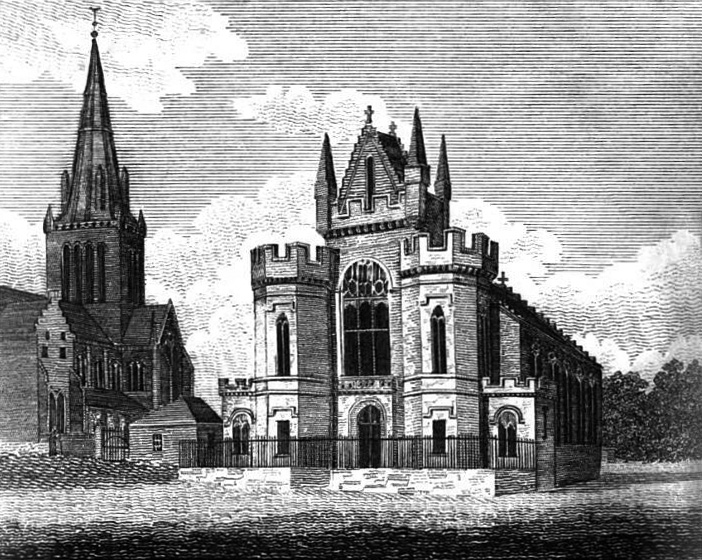

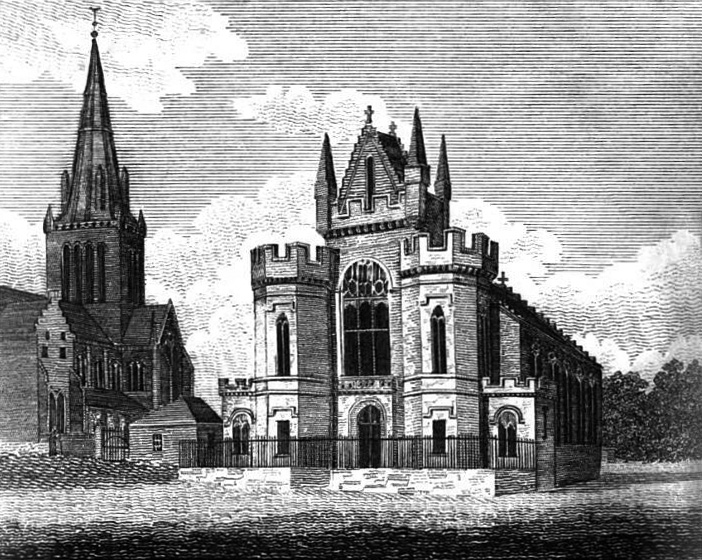

district. Subsequent moves followed: in 1868 to Morningside, Edinburgh and, in 1873, back to Glasgow when John Lang was appointed minister to the historic Barony Church

Barony Hall, also known as Barony Church, is a red sandstone Victorian neo-Gothic-style building on Castle Street in the Townhead area of Glasgow, Scotland, near Glasgow Cathedral, Glasgow Royal Infirmary and the city's oldest surviving house ...

.

Among Cosmo's brothers were Marshall Buchanan Lang, who followed his father into the Church of Scotland, eventually serving as its Moderator in 1935; and Norman Macleod Lang, who served the Church of England as Bishop suffragan of Leicester.

In Glasgow, Lang attended the Park School, a day establishment where he won a prize for an essay on English literature and played the occasional game of football; otherwise, he recorded, "I was never greatly interested in he school's

He or HE may refer to:

Language

* He (pronoun), an English pronoun

* He (kana), the romanization of the Japanese kana へ

* He (letter), the fifth letter of many Semitic alphabets

* He (Cyrillic), a letter of the Cyrillic script called ''He'' ...

proceedings." Holidays were spent in different parts of Scotland, most notably in Argyll

Argyll (; archaically Argyle, in modern Gaelic, ), sometimes called Argyllshire, is a historic county and registration county of western Scotland.

Argyll is of ancient origin, and corresponds to most of the part of the ancient kingdom of ...

to which, later in life, Lang would frequently return. In 1878, at the age of 14, Lang sat and passed his matriculation

Matriculation is the formal process of entering a university, or of becoming eligible to enter by fulfilling certain academic requirements such as a matriculation examination.

Australia

In Australia, the term "matriculation" is seldom used now. ...

examinations. Despite his youth, he began his studies at the University of Glasgow later that year.

University of Glasgow

At the university Lang's tutors included some of Scotland's leading academics: the Greek scholarRichard Claverhouse Jebb

Sir Richard Claverhouse Jebb (27 August 1841 – 9 December 1905) was a British classical scholar.

Life

Jebb was born in Dundee, Scotland. His father Robert was a well-known Irish barrister; his mother was Emily Harriet Horsley, daughter of ...

, the physicist William Thomson (who was later created Lord Kelvin) and the philosopher Edward Caird

Edward Caird (; 23 March 1835 – 1 November 1908) was a Scottish philosopher. He was a holder of LLD, DCL, and DLitt.

Life

The younger brother of the theologian John Caird, he was the son of engineer John Caird, the proprietor of Caird & ...

. Long afterwards Lang commented on the inability of some of these eminent figures to handle "the Scottish boors who formed a large part of their classes". Lang was most strongly influenced by Caird, who gave the boy's mind "its first real awakening". Lang recalled how, in a revelation as he was passing through Kelvingrove Park

Kelvingrove Park is a public park located on the River Kelvin in the West End of the city of Glasgow, Scotland, containing the Kelvingrove Art Gallery and Museum.

History

Kelvingrove Park was originally created as the West End Park in 1852, and ...

, he expressed aloud his sudden conviction that: "The Universe is one and its Unity and Ultimate Reality is God!" He acknowledged that his greatest failure at the university was his inability to make any progress in his understanding of mathematics, "to me, then and always, unintelligible".Lockhart, pp. 10–13

In 1881 Lang made his first trip outside Scotland, to London where he heard the theologian and orator Henry Parry Liddon

Henry Parry Liddon (1829–1890), also known as H. P. Liddon, was an English theologian. From 1870 to 1882, he was Dean Ireland's Professor of the Exegesis of Holy Scripture at the University of Oxford.

Biography

The son of a naval capt ...

preach in St Paul's Cathedral

St Paul's Cathedral is an Anglican cathedral in London and is the seat of the Bishop of London. The cathedral serves as the mother church of the Diocese of London. It is on Ludgate Hill at the highest point of the City of London and is a G ...

.Lockhart, pp. 19–23 He also heard William Ewart Gladstone

William Ewart Gladstone ( ; 29 December 1809 – 19 May 1898) was a British statesman and Liberal politician. In a career lasting over 60 years, he served for 12 years as Prime Minister of the United Kingdom, spread over four non-conse ...

and Joseph Chamberlain

Joseph Chamberlain (8 July 1836 – 2 July 1914) was a British statesman who was first a radical Liberal, then a Liberal Unionist after opposing home rule for Ireland, and eventually served as a leading imperialist in coalition with the Cons ...

debating in the House of Commons

The House of Commons is the name for the elected lower house of the bicameral parliaments of the United Kingdom and Canada. In both of these countries, the Commons holds much more legislative power than the nominally upper house of parliament. ...

. Later that year he travelled to Cambridge to stay with a friend who was studying there. A visit to King's College Chapel

King's College Chapel is the chapel of King's College in the University of Cambridge. It is considered one of the finest examples of late Perpendicular Gothic English architecture and features the world's largest fan vault. The Chapel was bui ...

persuaded Lang that he should study at the college; the following January he sat and passed the entrance examination. When he discovered that as part of his degree studies he would be examined in mathematics, his enthusiasm disappeared. Instead, he applied to Balliol College

Balliol College () is one of the constituent colleges of the University of Oxford in England. One of Oxford's oldest colleges, it was founded around 1263 by John I de Balliol, a landowner from Barnard Castle in County Durham, who provided the ...

, Oxford, and was accepted. In mid-1882 he ended his studies at Glasgow with a Master of Arts

A Master of Arts ( la, Magister Artium or ''Artium Magister''; abbreviated MA, M.A., AM, or A.M.) is the holder of a master's degree awarded by universities in many countries. The degree is usually contrasted with that of Master of Science. Tho ...

degree, and was awarded prizes for essays on politics and church history.

Oxford

Lang started at Balliol in October 1882. In his first term he successfully sat for the Brackenbury Scholarship, described by his biographer John Gilbert Lockhart as "the Blue Ribbon of history scholarship at any University of the British Isles".Lockhart, pp. 28–29 In February 1883 his first speech at the

Lang started at Balliol in October 1882. In his first term he successfully sat for the Brackenbury Scholarship, described by his biographer John Gilbert Lockhart as "the Blue Ribbon of history scholarship at any University of the British Isles".Lockhart, pp. 28–29 In February 1883 his first speech at the Oxford Union

The Oxford Union Society, commonly referred to simply as the Oxford Union, is a debating society in the city of Oxford England, whose membership is drawn primarily from the University of Oxford. Founded in 1823, it is one of Britain's oldest ...

, against the disestablishment

The separation of church and state is a philosophical and jurisprudential concept for defining political distance in the relationship between religious organizations and the state. Conceptually, the term refers to the creation of a secular stat ...

of the Church of Scotland, was warmly received; the chairman likened his oratory to that of the Ancient Greek statesman, Demosthenes.Lockhart, pp. 33–35 He became the Union's president in the Trinity term of 1883, and the following year was a co-founder of the Oxford University Dramatic Society

The Oxford University Dramatic Society (OUDS) is the principal funding body and provider of theatrical services to the many independent student productions put on by students in Oxford, England. Not all student productions at Oxford University ...

(OUDS).

Although Lang considered himself forward-thinking, he joined and became secretary of the Canning Club, the university's principal Conservative

Conservatism is a cultural, social, and political philosophy that seeks to promote and to preserve traditional institutions, practices, and values. The central tenets of conservatism may vary in relation to the culture and civilization ...

society. His contemporary Robert Cecil recorded that Lang's "progressive" opinions were somewhat frowned upon by traditional Tories

A Tory () is a person who holds a political philosophy known as Toryism, based on a British version of traditionalism and conservatism, which upholds the supremacy of social order as it has evolved in the English culture throughout history. The ...

, who nevertheless respected his ability. Lang later assisted in the founding of the University settlement of Toynbee Hall

Toynbee Hall is a charitable institution that works to address the causes and impacts of poverty in the East End of London and elsewhere. Established in 1884, it is based in Commercial Street, Spitalfields, and was the first university-affiliat ...

, a mission to help the poor in the East End of London

The East End of London, often referred to within the London area simply as the East End, is the historic core of wider East London, east of the Roman and medieval walls of the City of London and north of the River Thames. It does not have univ ...

.Lockhart, pp. 39–41 He had been first drawn to this work in 1883, after listening to a sermon in St Mary's Church, Oxford, by Samuel Augustus Barnett, Vicar of St Jude's, Whitechapel. Barnett became the settlement's first leader, while Lang became one of its first undergraduate secretaries. He spent so much time on these duties that he was chided by the Master of Balliol, Benjamin Jowett

Benjamin Jowett (, modern variant ; 15 April 1817 – 1 October 1893) was an English tutor and administrative reformer in the University of Oxford, a theologian, an Anglican cleric, and a translator of Plato and Thucydides. He was Master of B ...

, for neglecting his studies. In 1886 Lang graduated with first-class honours

The British undergraduate degree classification system is a grading structure for undergraduate degrees or bachelor's degrees and integrated master's degrees in the United Kingdom. The system has been applied (sometimes with significant variati ...

in History; in October he failed to secure a Fellowship of All Souls College

All Souls College (official name: College of the Souls of All the Faithful Departed) is a constituent college of the University of Oxford in England. Unique to All Souls, all of its members automatically become fellows (i.e., full members of ...

, blaming his poor early scholastic training in Glasgow.

Towards ordination

Lang's career ambition from early in life was to practise law, enter politics and then take office in some future Conservative administration. In 1887 he began his studies for the English Bar, working in the London chambers of W.S. Robson, a future

Lang's career ambition from early in life was to practise law, enter politics and then take office in some future Conservative administration. In 1887 he began his studies for the English Bar, working in the London chambers of W.S. Robson, a future Attorney-General

In most common law jurisdictions, the attorney general or attorney-general (sometimes abbreviated AG or Atty.-Gen) is the main legal advisor to the government. The plural is attorneys general.

In some jurisdictions, attorneys general also have exec ...

, whose "vehement radicalism was an admirable stimulus and corrective to ang'sliberal Conservatism".Lang, quoted in Lockhart, pp. 52–53 During these years Lang was largely aloof from religion, but continued churchgoing out of what he termed "hereditary respect". He attended services at the nonconformist City Temple church and sometimes went to St Paul's Cathedral. Of his life at that time he said: "I must confess that I played sometimes with those external temptations that our Christian London flaunts in the face of its young men."

In October 1888 Lang was elected to an All Souls Fellowship, and began to divide his time between London and Oxford. Some of his Oxford friends were training for ordination and Lang was often drawn into their discussions. Eventually the question entered Lang's mind: "Why shouldn't ''you'' be ordained?"Lockhart, pp. 62–66 The thought persisted, and one Sunday evening in early 1889, after a visit to the theological college at Cuddesdon in Oxfordshire, Lang attended evening service at Cuddesdon

Cuddesdon is a mainly rural village in South Oxfordshire centred ESE of Oxford. It has the largest Church of England clergy training centre, Ripon College Cuddesdon. Residents number approximately 430 in Cuddesdon's nucleated village centre a ...

parish church. By his own account, during the sermon he was gripped by "a masterful inward voice" which told him "You are wanted. You are called. You must obey." He immediately severed his connection with the Bar, renounced his political ambitions and applied for a place at Cuddesdon College. With the help of an All Souls contact, the essential step of his confirmation

In Christian denominations that practice infant baptism, confirmation is seen as the sealing of the covenant created in baptism. Those being confirmed are known as confirmands. For adults, it is an affirmation of belief. It involves laying on ...

into the Church of England was supervised by the Bishop of Lincoln

The Bishop of Lincoln is the ordinary (diocesan bishop) of the Church of England Diocese of Lincoln in the Province of Canterbury.

The present diocese covers the county of Lincolnshire and the unitary authority areas of North Lincolnshire and ...

. Lang's decision to become an Anglican and seek ordination disappointed his Presbyterian father, who nevertheless wrote to his son: "What you think, prayerfully and solemnly, you ought to do – you must do – we will accept."

Early ministry

Leeds

After a year's study atCuddesdon

Cuddesdon is a mainly rural village in South Oxfordshire centred ESE of Oxford. It has the largest Church of England clergy training centre, Ripon College Cuddesdon. Residents number approximately 430 in Cuddesdon's nucleated village centre a ...

, Lang was ordained as deacon

A deacon is a member of the diaconate, an office in Christian churches that is generally associated with service of some kind, but which varies among theological and denominational traditions. Major Christian churches, such as the Catholic Chur ...

. He rejected an offer of the chaplaincy of All Souls as he wanted to be "up and doing" in a tough parish.Lockhart, p. 87 Lang identified with the Anglo-Catholic

Anglo-Catholicism comprises beliefs and practices that emphasise the Catholic heritage and identity of the various Anglican churches.

The term was coined in the early 19th century, although movements emphasising the Catholic nature of Anglican ...

tradition of the Church of England, in part, he admitted, as a reaction against his evangelical

Evangelicalism (), also called evangelical Christianity or evangelical Protestantism, is a worldwide interdenominational movement within Protestant Christianity that affirms the centrality of being " born again", in which an individual expe ...

upbringing in the Church of Scotland. His sympathies lay with the progressive wing of Anglo-Catholicism represented by the '' Lux Mundi'' essays, published in 1888 by a group of forward-looking Oxford theologians. Among these was Edward Stuart Talbot, Warden of Keble, who in 1888 had become Vicar of Leeds Parish Church. Talbot had contributed the essay entitled "The Preparation for History in Christ" in ''Lux Mundi''. On ordination Lang eagerly accepted the offer of a curacy

A curate () is a person who is invested with the ''care'' or ''cure'' (''cura'') ''of souls'' of a parish. In this sense, "curate" means a parish priest; but in English-speaking countries the term ''curate'' is commonly used to describe clergy w ...

under Talbot, and arrived in Leeds in late 1890.

Leeds Parish Church, rebuilt and reconsecrated in 1841 after an elaborate ceremony, was of almost cathedral size, the centre of a huge parish ministered by many curate

A curate () is a person who is invested with the ''care'' or ''cure'' (''cura'') ''of souls'' of a parish. In this sense, "curate" means a parish priest; but in English-speaking countries the term ''curate'' is commonly used to describe clergy ...

s. Lang's district was the Kirkgate, one of the poorest areas, many of whose 2,000 inhabitants were prostitutes. Lang and his fellow curates fashioned a clergy house from a derelict public house

A pub (short for public house) is a kind of drinking establishment which is licensed to serve alcoholic drinks for consumption on the premises. The term ''public house'' first appeared in the United Kingdom in late 17th century, and wa ...

. He later moved next door, into a condemned property which became his home for his remaining service in Leeds. In addition to his normal parish duties, Lang acted temporarily as Principal of the Clergy School, was chaplain to Leeds Infirmary, and took charge of a men's club of around a hundred members. On 24 May 1891 he was ordained to full priesthood.Lockhart, pp. 94–99

Lang continued to visit Oxford when time allowed and on a visit to All Souls in June 1893 he was offered the post of Dean of Divinity at Magdalen College

Magdalen College (, ) is a constituent college of the University of Oxford. It was founded in 1458 by William of Waynflete. Today, it is the fourth wealthiest college, with a financial endowment of £332.1 million as of 2019 and one of the ...

. Other offers were open to him; the Bishop of Newcastle wished to appoint him vicar of the cathedral church in Newcastle and Benjamin Jowett wished him to return to Balliol as a tutor in theology. Lang chose Magdalen; the idea of being in charge of young men who might in the future achieve positions of responsibility was attractive to him and, in October 1893, with many regrets, he left Leeds.Lockhart, pp. 101–04

Magdalen College

As Magdalen's Dean of Divinity (college chaplain), Lang had pastoral duties with the college's undergraduates and responsibility for the chapel and its choir. Lang was delighted with this latter obligation; his concern for the purity of the choir's sound led him to request that visitors "join in the service silently". In 1894 Lang was asked to add to his workload by acting as Vicar of theUniversity Church of St Mary the Virgin

The University Church of St Mary the Virgin (St Mary's or SMV for short) is an Oxford church situated on the north side of the High Street. It is the centre from which the University of Oxford grew and its parish consists almost exclusively of un ...

, where John Henry Newman

John Henry Newman (21 February 1801 – 11 August 1890) was an English theologian, academic, intellectual, philosopher, polymath, historian, writer, scholar and poet, first as an Anglican priest and later as a Catholic priest and ...

had begun his Oxford ministry in 1828. The church had almost ceased to function when Lang took it over, but he revived regular services, chose preachers with care and slowly rebuilt the congregation. In December 1895 he was offered the post of Vicar of Portsea Portsea may refer to:

* Portsea, Victoria, a seaside town in Australia

* Portsea Island, an island on the south coast of England contained within the city of Portsmouth

* Portsea, Portsmouth

Portsea Island is a flat and low-lying natural i ...

, a large parish within Portsmouth

Portsmouth ( ) is a port and city in the ceremonial county of Hampshire in southern England. The city of Portsmouth has been a unitary authority since 1 April 1997 and is administered by Portsmouth City Council.

Portsmouth is the most dense ...

on the south coast, but he was not ready to leave Oxford and refused. Some months later he had further thoughts; the strain of his dual appointment in Oxford was beginning to tell and, he claimed, "the thought of this great parish f Portseaand work going a-begging troubled my conscience." After discovering that the Portsea offer was still open, he decided to accept, though with some misgiving.

Portsea

Portsea, covering much of the town of Portsmouth, was a dockside parish of around 40,000 inhabitants with a mixture of housing ranging from neat terraces to squalid slums.Lockhart, pp. 116–19 The large, recently rebuilt church held more than 2,000 people. Lang arrived in June 1896 to lead a team of more than a dozen curates serving the five districts of the parish. He quickly resumed the kind of urban parish work he had carried out in Leeds; he founded a Sunday afternoon men's conference with 300 men, and supervised the construction of a large conference hall as a centre for parish activities.Lockhart, pp. 122–25 He also pioneered the establishment of parochial church councils long before they were given legal status in 1919. ("Early Ministry" section) Outside his normal parish duties, Lang served as chaplain to the local prison, and became acting chaplain to the 2nd HampshireRoyal Artillery

The Royal Regiment of Artillery, commonly referred to as the Royal Artillery (RA) and colloquially known as "The Gunners", is one of two regiments that make up the artillery arm of the British Army. The Royal Regiment of Artillery comprises t ...

Volunteer Corps.

Lang's relationship with his curates was generally formal. They were aware of his ambition and felt that he sometimes spent too much time on his outside interests such as his All Souls Fellowship, but were nevertheless impressed by his efficiency and his powers of oratory. The Church historian Adrian Hastings

Adrian Hastings (23 June 1929 – 30 May 2001) was a Roman Catholic priest, historian and author. He wrote a book about the " Wiriyamu Massacre" during the Mozambican War of Independence and became an influential scholar of Christian history in ...

singles out Portsea under Lang as an example of "extremely disciplined pastoral professionalism". Lang may have realised that he was destined for high office; he is reported to have practised the signature "Cosmo Cantuar" during a relaxed discussion with his curates ("Cantuar" is part of the Archbishop of Canterbury

The archbishop of Canterbury is the senior bishop and a principal leader of the Church of England, the ceremonial head of the worldwide Anglican Communion and the diocesan bishop of the Diocese of Canterbury. The current archbishop is Jus ...

's formal signature). In January 1898 he was invited by Queen Victoria

Victoria (Alexandrina Victoria; 24 May 1819 – 22 January 1901) was Queen of the United Kingdom of Great Britain and Ireland from 20 June 1837 until her death in 1901. Her reign of 63 years and 216 days was longer than that of any previ ...

to preach at Osborne House

Osborne House is a former royal residence in East Cowes, Isle of Wight, United Kingdom. The house was built between 1845 and 1851 for Queen Victoria and Prince Albert as a summer home and rural retreat. Albert designed the house himself, in ...

, her Isle of Wight

The Isle of Wight ( ) is a county in the English Channel, off the coast of Hampshire, from which it is separated by the Solent. It is the largest and second-most populous island of England. Referred to as 'The Island' by residents, the Is ...

home. Afterwards he talked with the Queen who, Lang records, suggested that he should marry. Lang replied that he could not afford to as his curates cost too much. He added: "If a curate proves unsatisfactory I can get rid of him. A wife is a fixture." He was summoned on several more occasions and in the following January was appointed an Honorary Chaplain to the Queen

An Honorary Chaplain to the King (KHC) is a member of the clergy within the United Kingdom who, through long and distinguished service, is appointed to minister to the monarch of the United Kingdom. When the reigning monarch is female, Honorary Ch ...

. These visits to Osborne were the start of a close association with the Royal Family which lasted for the rest of Lang's life. As one of the Queen's chaplains, he assisted in the funeral arrangements after her death in January 1901.

Bishop and canon

In March 1901 Lang was appointedsuffragan

A suffragan bishop is a type of bishop in some Christian denominations.

In the Anglican Communion, a suffragan bishop is a bishop who is subordinate to a metropolitan bishop or diocesan bishop (bishop ordinary) and so is not normally jurisdiction ...

Bishop of Stepney

The Bishop of Stepney is an episcopal title used by a suffragan bishop of the Church of England Diocese of London, in the Province of Canterbury, England. The title takes its name after Stepney, an inner-city district in the London Borough of To ...

and a canon

Canon or Canons may refer to:

Arts and entertainment

* Canon (fiction), the conceptual material accepted as official in a fictional universe by its fan base

* Literary canon, an accepted body of works considered as high culture

** Western can ...

of St Paul's Cathedral. These appointments reflected his growing reputation and recognised his successful ministry in working-class parishes. He was consecrated

Consecration is the solemn dedication to a special purpose or service. The word ''consecration'' literally means "association with the sacred". Persons, places, or things can be consecrated, and the term is used in various ways by different gro ...

bishop by the Archbishop of Canterbury, Frederick Temple

Frederick Temple (30 November 1821 – 23 December 1902) was an English academic, teacher and churchman, who served as Bishop of Exeter (1869–1885), Bishop of London (1885–1896) and Archbishop of Canterbury (1896–1902).

Early life

T ...

, in St Paul's Cathedral, on 1 May;Lockhart, p. 147 his time would subsequently be divided between his work in the Stepney region and his duties at St Paul's.

The University of Oxford

, mottoeng = The Lord is my light

, established =

, endowment = £6.1 billion (including colleges) (2019)

, budget = £2.145 billion (2019–20)

, chancellor ...

honoured him with the degree of Doctor of Divinity

A Doctor of Divinity (D.D. or DDiv; la, Doctor Divinitatis) is the holder of an advanced academic degree in divinity.

In the United Kingdom, it is considered an advanced doctoral degree. At the University of Oxford, doctors of divinity are ran ...

in late May 1901.

Stepney

Lang's region of Stepney within the Diocese of London extended over the whole area generally known as London's East End, with two million people in more than 200 parishes. Almost all were poor, and housed in overcrowded and insanitary conditions. Lang knew something of the area from his undergraduate activities at Toynbee Hall, and his conscience was troubled by the squalor that he saw as he travelled around the district, usually by bus and tram. Lang's liberal conservatism enabled him to associate easily with Socialist leaders such asWill Crooks

William Crooks (6 April 1852 – 5 June 1921) was a noted trade unionist and politician from Poplar, London, and a member of the Fabian Society. He is particularly remembered for his campaigning work against poverty and inequality.

Early life

...

and George Lansbury

George Lansbury (22 February 1859 – 7 May 1940) was a British politician and social reformer who led the Labour Party from 1932 to 1935. Apart from a brief period of ministerial office during the Labour government of 1929–31, he spe ...

, successive mayors of Poplar; he was responsible for bringing the latter back to regular communion in the Church. In 1905 he and Lansbury joined the Central London Unemployed Body, set up by the government to tackle the region's unemployment problems. That same year Lang took as his personal assistant a young Cambridge graduate and clergyman's son, Dick Sheppard, who became a close friend and confidante. Sheppard was eventually ordained, becoming a radical clergyman and founder of the Peace Pledge Union

The Peace Pledge Union (PPU) is a non-governmental organisation that promotes pacifism, based in the United Kingdom. Its members are signatories to the following pledge: "War is a crime against humanity. I renounce war, and am therefore determin ...

. Lang believed that socialism was a growing force in British life, and at a Church Congress

Church Congress is an annual meeting of members of the Church of England, lay and clerical, to discuss matters religious, moral or social, in which the church is interested. It has no legislative authority, and there is no voting on the questions ...

in Great Yarmouth

Great Yarmouth (), often called Yarmouth, is a seaside town and unparished area in, and the main administrative centre of, the Borough of Great Yarmouth in Norfolk, England; it straddles the River Yare and is located east of Norwich. A pop ...

in 1907 he speculated on how the Church should respond to this. His remarks reached ''The New York Times

''The New York Times'' (''the Times'', ''NYT'', or the Gray Lady) is a daily newspaper based in New York City with a worldwide readership reported in 2020 to comprise a declining 840,000 paid print subscribers, and a growing 6 million paid ...

'', which warned that modern socialism was often equated with unrest, that "the cry of the demagogue is in the air" and that the Church should not heed this cry.

Much of the work in the district was supported by the East London Church Fund, established in 1880 to provide for additional clergy and lay workers in the poorest districts. Lang preached in wealthier parishes throughout Southern England, and urged his listeners to contribute to the Fund.Lockhart, pp. 161–64 He resumed his ministry to the army when, in 1907, he was appointed Honorary Chaplain to the City of London Imperial Yeomanry (Rough Riders). He became chairman of the Church of England Men's Society

The Church of England Men's Society was founded in 1899 by Archbishop Frederick Temple to bring men together to socialise in a Christian environment.

It began by amalgamating the Church of England's Young Men's Society, the Young Men's Friendly S ...

(CEMS), which had been founded in 1899 by the merger of numerous organisations doing the same work. Initially he found it "a very sickly infant", but under his leadership it expanded rapidly, and soon had over 20,000 members in 600 branches. Later he became critical of the Church's failure to use this movement effectively, calling it one of the Church's lost opportunities.

St Paul's Cathedral

Lang's appointment as a canon of St Paul's Cathedral required him to spend three months annually as the canon in residence, with administrative and preaching duties.Lockhart, pp. 149–50 Following his appointment as canon, he was also appointed treasurer of the cathedral. His preaching on Sunday afternoons caught the attention of William Temple, Lang's future successor at both York and Canterbury, who was then an undergraduate at Oxford. Temple observed that, in contrast to the Bishop of London's sermons, listening to Lang brought on an intellectual rather than emotional pleasure: "I can remember all his points, just because their connexion is inevitable.... And for me, there is no doubt that this is the more edifying by far." Lang was a member of the cathedral's governing body, the Dean and Chapter, and was responsible for the organisation of special occasions, such as the service of thanksgiving for KingEdward VII

Edward VII (Albert Edward; 9 November 1841 – 6 May 1910) was King of the United Kingdom of Great Britain and Ireland and Emperor of India, from 22 January 1901 until Death and state funeral of Edward VII, his death in 1910.

The second chil ...

's recovery from appendicitis

Appendicitis is inflammation of the appendix. Symptoms commonly include right lower abdominal pain, nausea, vomiting, and decreased appetite. However, approximately 40% of people do not have these typical symptoms. Severe complications of a r ...

in July 1902.

Archbishop of York

Appointment

In late 1908 Lang was informed of his election as Bishop of Montreal. Letters from theGovernor General of Canada

The governor general of Canada (french: gouverneure générale du Canada) is the federal viceregal representative of the . The is head of state of Canada and the 14 other Commonwealth realms, but resides in oldest and most populous realm ...

and the Canadian High Commissioner urged him to accept, but the Archbishop of Canterbury asked him to refuse.Lockhart, pp. 178–80 A few weeks later a letter from H. H. Asquith

Herbert Henry Asquith, 1st Earl of Oxford and Asquith, (12 September 1852 – 15 February 1928), generally known as H. H. Asquith, was a British statesman and Liberal Party politician who served as Prime Minister of the United Kingdom ...

, the prime minister, informed Lang that he had been nominated Archbishop of York

The archbishop of York is a senior bishop in the Church of England, second only to the archbishop of Canterbury. The archbishop is the diocesan bishop of the Diocese of York and the metropolitan bishop of the province of York, which covers th ...

. Lang was only 44 years old, and had no experience as a diocesan bishop. On the issue of age, the ''Church Times

The ''Church Times'' is an independent Anglican weekly newspaper based in London and published in the United Kingdom on Fridays.

History

The ''Church Times'' was founded on 7 February 1863 by George Josiah Palmer, a printer. It fought for the ...

'' believed that Asquith deliberately recommended the youngest bishop available, after strong political lobbying for the appointment of the elderly Bishop of Hereford

The Bishop of Hereford is the ordinary of the Church of England Diocese of Hereford in the Province of Canterbury.

The episcopal see is centred in the City of Hereford where the bishop's seat (''cathedra'') is in the Cathedral Church of Sa ...

, John Percival

John Percival (3 April 1779 – 7 September 1862), known as Mad Jack Percival, was a celebrated officer in the United States Navy during the Quasi-War with France, the War of 1812, the campaign against West Indies pirates, and the Mexican–Amer ...

. Such a promotion for a suffragan, and within so short a period after ordination, was without recent precedent in the Church of England. Lang's friend Hensley Henson

Herbert Hensley Henson (8 November 1863 – 27 September 1947) was an Anglican priest, bishop, scholar and controversialist. He was Bishop of Hereford from 1918 to 1920 and Bishop of Durham from 1920 to 1939.

The son of a zealous member ...

, a future Bishop of Durham

The Bishop of Durham is the Anglican bishop responsible for the Diocese of Durham in the Province of York. The diocese is one of the oldest in England and its bishop is a member of the House of Lords. Paul Butler has been the Bishop of Durham ...

, wrote: "I am, of course, surprised that you go ''straight'' to an archbishopric ... But you are too meteoric for precedent." The appointment was generally well received, although the Protestant Truth Society

The Protestant Truth Society (PTS) is a Protestant religious organisation based in London, United Kingdom.

History of the organization

It was founded by John Kensit in 1889, to protest against the influence of Roman Catholicism within the Church ...

sought in vain to prevent its confirmation. Strong opponents of Anglo-Catholic practices, they maintained that as Bishop of Stepney Lang had "connived at and encouraged flagrant breaking of the law relating to church ritual".

First years

Lang'selection

An election is a formal group decision-making process by which a population chooses an individual or multiple individuals to hold public office.

Elections have been the usual mechanism by which modern representative democracy has operat ...

to York was confirmed on 20 January and he was enthroned at York Minster

The Cathedral and Metropolitical Church of Saint Peter in York, commonly known as York Minster, is the cathedral of York, North Yorkshire, England, and is one of the largest of its kind in Northern Europe. The minster is the seat of the Arch ...

on 25 January 1909. In 18 years since ordination he had risen to the second-highest position in the Church of England. In addition to his diocesan responsibilities for York itself, he became head of the entire Northern Province, and a member of the House of Lords

The House of Lords, also known as the House of Peers, is the upper house of the Parliament of the United Kingdom. Membership is by appointment, heredity or official function. Like the House of Commons, it meets in the Palace of Westminster in ...

. Believing that the Diocese of York

The Diocese of York is an administrative division of the Church of England, part of the Province of York. It covers the city of York, the eastern part of North Yorkshire, and most of the East Riding of Yorkshire.

The diocese is headed by the ...

was too large, he proposed reducing it by forming a new Diocese of Sheffield, which after several years' work was inaugurated in 1914. In the years following his appointment, Lang spoke out on a range of social and economic issues, and in support of improved working conditions. After taking his seat in the House of Lords in February 1909, he made his maiden speech in November in the debate on the controversial People's Budget

The 1909/1910 People's Budget was a proposal of the Liberal government that introduced unprecedented taxes on the lands and incomes of Britain's wealthy to fund new social welfare programmes. It passed the House of Commons in 1909 but was blo ...

, advising the Lords against their intention to reject this measure. He cast his first Lords vote against rejection, because he was "deeply convinced of the unwisdom of the course the Lords proposed to take". Although his speech was received with respect, Lang's stance was politely reproved by the leading Conservative peer Lord Curzon

George Nathaniel Curzon, 1st Marquess Curzon of Kedleston, (11 January 1859 – 20 March 1925), styled Lord Curzon of Kedleston between 1898 and 1911 and then Earl Curzon of Kedleston between 1911 and 1921, was a British Conservative statesman ...

.

Despite this socially progressive stance, Lang's political instincts remained conservative. He voted against the 1914 Irish Home Rule Bill and opposed liberalisation of the divorce laws.McLeod, p. 232 After playing a prominent role in King George V's coronation in 1911, Lang became increasingly close to the Royal Family, an association which drew the comment that he was "more courtier than cleric". His love of ceremony, and concern for how an archbishop should look and live, began to obscure other aspects of his ministry; rather than assuming the role of the people's prelate he began, in the words of his biographer Alan Wilkinson, to act as a "prince of the church".

First World War

When war broke out in August 1914, Lang concluded that the conflict was righteous, and that younger clergy should be encouraged to serve as military chaplains, although it was not their duty to fight. He thereafter was active in recruiting campaigns throughout his province. At a meeting in York in November 1914 he caused offence when he spoke out against excessive anti-German propaganda, and recalled a "sacred memory" of the

When war broke out in August 1914, Lang concluded that the conflict was righteous, and that younger clergy should be encouraged to serve as military chaplains, although it was not their duty to fight. He thereafter was active in recruiting campaigns throughout his province. At a meeting in York in November 1914 he caused offence when he spoke out against excessive anti-German propaganda, and recalled a "sacred memory" of the Kaiser

''Kaiser'' is the German word for "emperor" (female Kaiserin). In general, the German title in principle applies to rulers anywhere in the world above the rank of king (''König''). In English, the (untranslated) word ''Kaiser'' is mainly ap ...

kneeling with King Edward VII at the bier of Queen Victoria. ("First World War" section) These remarks, perceived as pro-German, produced what Lang termed "a perfect hail of denunciation".Lockhart, pp. 249–51 The strain of this period, coupled with the onset of alopecia

Hair loss, also known as alopecia or baldness, refers to a loss of hair from part of the head or body. Typically at least the head is involved. The severity of hair loss can vary from a small area to the entire body. Inflammation or scar ...

, drastically altered Lang's relatively youthful appearance to that of a bald and elderly-looking man. His friends were shocked; the king, meeting him on the Royal train, apparently burst into guffaws of laughter.

Public hostility against Lang was slow to subside, re-emerging from time to time throughout the war. Lang continued his contribution to the war effort, paying visits to the Grand Fleet

The Grand Fleet was the main battlefleet of the Royal Navy during the First World War. It was established in August 1914 and disbanded in April 1919. Its main base was Scapa Flow in the Orkney Islands.

History

Formed in August 1914 from the F ...

and to the Western Front Western Front or West Front may refer to:

Military frontiers

* Western Front (World War I), a military frontier to the west of Germany

*Western Front (World War II), a military frontier to the west of Germany

*Western Front (Russian Empire), a maj ...

. He applied all his organisational skills to the Archbishop of Canterbury's National Mission of Repentance and Hope, an initiative designed to renew Christian faith nationwide, but it failed to make a significant impact.

As a result of the Battle of Jerusalem

The Battle of Jerusalem occurred during the British Empire's "Jerusalem Operations" against the Ottoman Empire, in World War I, when fighting for the city developed from 17 November, continuing after the surrender until 30 December 1917, to ...

of December 1917, the British Empire

The British Empire was composed of the dominions, colonies, protectorates, mandates, and other territories ruled or administered by the United Kingdom and its predecessor states. It began with the overseas possessions and trading posts e ...

's Egyptian Expeditionary Force

The Egyptian Expeditionary Force (EEF) was a British Empire military formation, formed on 10 March 1916 under the command of General Archibald Murray from the Mediterranean Expeditionary Force and the Force in Egypt (1914–15), at the beginning o ...

captured the Holy City

A holy city is a city important to the history or faith of a specific religion. Such cities may also contain at least one headquarters complex (often containing a religious edifice, seminary, shrine, residence of the leading cleric of the religi ...

, bringing it under Christian control for the first time since the Crusades

The Crusades were a series of religious wars initiated, supported, and sometimes directed by the Latin Church in the medieval period. The best known of these Crusades are those to the Holy Land in the period between 1095 and 1291 that were ...

. As Prelate of the Venerable Order of Saint John

The Order of St John, short for Most Venerable Order of the Hospital of Saint John of Jerusalem (french: l'ordre très vénérable de l'Hôpital de Saint-Jean de Jérusalem) and also known as St John International, is a British royal order of ...

, Lang led a service of celebration on 11 January 1918 at the Order's Grand Priory Church, Clerkenwell

Clerkenwell () is an area of central London, England.

Clerkenwell was an ancient parish from the mediaeval period onwards, and now forms the south-western part of the London Borough of Islington.

The well after which it was named was redis ...

. He explained that it was 917 years since the Order's hospital had been founded in Jerusalem

Jerusalem (; he, יְרוּשָׁלַיִם ; ar, القُدس ) (combining the Biblical and common usage Arabic names); grc, Ἱερουσαλήμ/Ἰεροσόλυμα, Hierousalḗm/Hierosóluma; hy, Երուսաղեմ, Erusałēm. i ...

, and 730 years since they were driven out by Saladin

Yusuf ibn Ayyub ibn Shadi () ( – 4 March 1193), commonly known by the epithet Saladin,, ; ku, سهلاحهدین, ; was the founder of the Ayyubid dynasty. Hailing from an ethnic Kurdish family, he was the first of both Egypt an ...

. "London is the city of the Empire's commerce, but Jerusalem is the city of the soul, and it is particularly fitting that British Armies should have delivered it out of the hands of the infidel

An infidel (literally "unfaithful") is a person accused of disbelief in the central tenets of one's own religion, such as members of another religion, or the irreligious.

Infidel is an ecclesiastical term in Christianity around which the Church ...

."

Early in 1918, at the invitation of the Episcopal Church of the United States

The Episcopal Church, based in the United States with additional dioceses elsewhere, is a member church of the worldwide Anglican Communion. It is a mainline Protestant denomination and is divided into nine provinces. The presiding bishop of ...

, he made a goodwill visit to America, praising the extent and willingness of America's participation in the war. The ''Westminster Gazette

''The Westminster Gazette'' was an influential Liberal newspaper based in London. It was known for publishing sketches and short stories, including early works by Raymond Chandler, Anthony Hope, D. H. Lawrence, Katherine Mansfield, and Saki, ...

'' called this "one of the most moving and memorable visits ever paid by an Englishman 'sic''to the United States".

Post-war years

After the war, Lang's primary cause was that of church unity. In 1920, as chairman of the Reunion Committee at the SixthLambeth Conference

The Lambeth Conference is a decennial assembly of bishops of the Anglican Communion convened by the Archbishop of Canterbury. The first such conference took place at Lambeth in 1867.

As the Anglican Communion is an international association ...

, he promoted an "Appeal to all Christian People", described by Hastings as "one of the rare historical documents that does not get forgotten with the years". It was unanimously adopted as the Conference's Resolution 9, and ended: "We ... ask that all should unite in a new and great endeavour to recover and to manifest to the world the unity of the Body of Christ for which He prayed." Despite initial warmth from the English Free Churches, little could be achieved in terms of practical union between episcopal and non-episcopal churches, and the initiative was allowed to lapse. Historically, the Appeal is considered the starting-point for the more successful ecumenical

Ecumenism (), also spelled oecumenism, is the concept and principle that Christians who belong to different Christian denominations should work together to develop closer relationships among their churches and promote Christian unity. The adjec ...

efforts of later generations.

Lang was supportive of the Malines Conversations

The Malines Conversations were a series of five informal ecumenical conversations held from 1921 to 1927 which explored possibilities for the corporate reunion between the Roman Catholic Church and the Church of England, forming one stage of Angli ...

of 1921–26, though not directly involved. These were informal meetings between leading British Anglo-Catholics and reform-minded European Roman Catholics, exploring the possibility of reuniting the Anglican and Roman communions. Although the discussions had the blessing of Randall Davidson

Randall Thomas Davidson, 1st Baron Davidson of Lambeth, (7 April 1848 – 25 May 1930) was an Anglican priest who was Archbishop of Canterbury from 1903 to 1928. He was the longest-serving holder of the office since the Reformation, and the f ...

, the Archbishop of Canterbury, many Anglican evangelicals were alarmed by them. Ultimately, the talks foundered on the entrenched opposition of the Catholic ultramontanes

Ultramontanism is a clerical political conception within the Catholic Church that places strong emphasis on the prerogatives and powers of the Pope. It contrasts with Gallicanism, the belief that popular civil authority—often represented by th ...

. A by-product of these conversations may have been the awakening of opposition to the revision of the Anglican Prayer Book

A prayer book is a book containing prayers and perhaps devotional readings, for private or communal use, or in some cases, outlining the liturgy of religious services. Books containing mainly orders of religious services, or readings for them ar ...

. The focus of this revision, which Lang supported, was to make concessions to Anglo-Catholic rituals and practices in the Anglican service. The new Prayer Book was overwhelmingly approved by the Church's main legislative body, the Church Assembly

The General Synod is the tricameral deliberative and legislative organ of the Church of England. The synod was instituted in 1970, replacing the Church Assembly, and is the culmination of a process of rediscovering self-government for the Church ...

, and by the House of Lords. Partly through the advocacy of the fervently evangelical Home Secretary

The secretary of state for the Home Department, otherwise known as the home secretary, is a senior minister of the Crown in the Government of the United Kingdom. The home secretary leads the Home Office, and is responsible for all nationa ...

, Sir William Joynson-Hicks

William Joynson-Hicks, 1st Viscount Brentford, (23 June 1865 – 8 June 1932), known as Sir William Joynson-Hicks, Bt, from 1919 to 1929 and popularly known as Jix, was an English solicitor and Conservative Party politician.

He first attr ...

, the revision was twice defeated in the House of Commons, in December 1927 by 238 votes to 205 and, in June 1928, by 266 to 220. Lang was deeply disappointed, writing that "the gusts of Protestant convictions, suspicions, fears ndprejudices swept through the House, and ultimately prevailed."

On 26 April 1923, George V

George V (George Frederick Ernest Albert; 3 June 1865 – 20 January 1936) was King of the United Kingdom and the British Dominions, and Emperor of India, from 6 May 1910 until his death in 1936.

Born during the reign of his grandmother ...

awarded Lang the Royal Victorian Chain

The Royal Victorian Chain is a decoration instituted in 1902 by King Edward VII as a personal award of the monarch (i.e. not an award made on the advice of any Commonwealth realm government). It ranks above the Royal Victorian Order, with which it ...

, an honour in the personal gift of the Sovereign After the marriage of Prince Albert, Duke of York (later George VI

George VI (Albert Frederick Arthur George; 14 December 1895 – 6 February 1952) was King of the United Kingdom and the Dominions of the British Commonwealth from 11 December 1936 until his death in 1952. He was also the last Emperor of I ...

) in 1923, Lang formed a friendship with his Duchess (later Queen Elizabeth The Queen Mother

Elizabeth Angela Marguerite Bowes-Lyon (4 August 1900 – 30 March 2002) was Queen of the United Kingdom and the Dominions of the British Commonwealth from 11 December 1936 to 6 February 1952 as the wife of King George VI. She was th ...

) which lasted for the rest of Lang's life. In 1926, he baptised Princess Elizabeth (later Elizabeth II

Elizabeth II (Elizabeth Alexandra Mary; 21 April 1926 – 8 September 2022) was Queen of the United Kingdom and other Commonwealth realms from 6 February 1952 until her death in 2022. She was queen regnant of 32 sovereign states durin ...

) in the private chapel of Buckingham Palace

Buckingham Palace () is a London royal residence and the administrative headquarters of the monarch of the United Kingdom. Located in the City of Westminster, the palace is often at the centre of state occasions and royal hospitality. It ...

. In January 1927, Lang took centre-stage in the elaborate ceremonies which marked the 1,300th anniversary of the founding of York Minster.

Archbishop of Canterbury

In office

Archbishop Davidson resigned in July 1928, believed to have been the first Archbishop of Canterbury ever to retire voluntarily. On 26 July Lang was notified by the Prime Minister,Stanley Baldwin

Stanley Baldwin, 1st Earl Baldwin of Bewdley, (3 August 186714 December 1947) was a British Conservative Party politician who dominated the government of the United Kingdom between the world wars, serving as prime minister on three occasions, ...

, that he would be the successor; William Temple would succeed Lang at York. Lang was enthroned as the new Archbishop of Canterbury on 4 December 1928, the first bachelor to hold the appointment in 150 years. A contemporary ''Time

Time is the continued sequence of existence and event (philosophy), events that occurs in an apparently irreversible process, irreversible succession from the past, through the present, into the future. It is a component quantity of various me ...

'' magazine article described Lang as "forthright and voluble" and as looking "like George Washington". Lang's first three years at Canterbury were marked by intermittent illnesses, which required periods of convalescence away from his duties. After 1932, he enjoyed good health for the rest of his life.

Lang avoided continuation of the Prayer Book controversy of 1928 by allowing the parliamentary process to lapse. He then authorised a statement permitting use of the rejected Book locally if the parochial church council gave approval. The issue remained dormant for the rest of Lang's tenure at Canterbury. He led the 1930 Lambeth Conference, where further progress was made in improving relations with the Eastern Orthodox Church

The Eastern Orthodox Church, also called the Orthodox Church, is the second-largest Christian church, with approximately 220 million baptized members. It operates as a communion of autocephalous churches, each governed by its bishops via ...

es and the Old Catholics

The terms Old Catholic Church, Old Catholics, Old-Catholic churches or Old Catholic movement designate "any of the groups of Western Christians who believe themselves to maintain in complete loyalty the doctrine and traditions of the undivide ...

, ("Archbishop of Canterbury" section) although again no agreement could be reached with the non-episcopal Free Churches. On an issue of greater concern to ordinary people, the Conference gave limited approval, for the first time, to the use of contraceptive devices, an issue in which Lang had no interest. Through the 1930s Lang continued to work for Church unity. In 1933 the Church of England assembly formed a Council on Foreign Relations and, in the following years, numerous exchange visits with Orthodox delegations took place, a process only halted by the outbreak of war. Lang's 1939 visit to the Ecumenical Patriarch of Constantinople

The ecumenical patriarch ( el, Οἰκουμενικός Πατριάρχης, translit=Oikoumenikós Patriárchēs) is the archbishop of Constantinople ( Istanbul), New Rome and '' primus inter pares'' (first among equals) among the heads of ...

is regarded as the high point of his ecumenical record. George Bell, Bishop of Chichester, maintained that no one in the Anglican Communion did more than Lang to promote the unity movement.

In 1937 the Oxford Conference on Church and Society, which later gave birth to the World Council of Churches

The World Council of Churches (WCC) is a worldwide Christian inter-church organization founded in 1948 to work for the cause of ecumenism. Its full members today include the Assyrian Church of the East, the Oriental Orthodox Churches, most ju ...

, produced what was according to the church historian Adrian Hastings "the most serious approach to the problems of society that the Church had yet managed", but without Lang's close involvement. By this time Lang's identification with the poor had largely vanished, as had his interest in social reform.Buchanan, p. 170 In the Church Assembly his closest ally was the aristocratic Lord Hugh Cecil; Hastings maintains that the Church of England in the 1930s was controlled "less by Lang and Temple in tandem than by Lang and Hugh Cecil". Lang got on well with Hewlett Johnson

Hewlett Johnson (25 January 1874 – 22 October 1966) was an English priest of the Church of England, Marxist Theorist and Stalinist. He was Dean of Manchester and later Dean of Canterbury, where he acquired his nickname "The Red Dean of Ca ...

, the pro-communist priest who was appointed Dean of Canterbury

The Dean of Canterbury is the head of the Chapter of the Cathedral of Christ Church, Canterbury, England. The current office of Dean originated after the English Reformation, although Deans had also existed before this time; its immediate prec ...

in 1931.

International and domestic politics

Lang often spoke in the House of Lords about the treatment of Russian Christians in the Soviet Union. He also denounced the anti-semitic policies of the German government, and he took private steps to help European Jews. ("International Affairs" section)Lockhart, pp. 381–83 In 1938 he was instrumental in saving 60 rabbis from Burgenland, who would have been murdered by the Nazis had the archbishop not obtained them entry visas to England. In 1933, having commented on the "noble task" of assisting India towards independence, he was appointed to the Joint Committee on the Indian Constitution. He condemned the Italian invasion ofAbyssinia

The Ethiopian Empire (), also formerly known by the exonym Abyssinia, or just simply known as Ethiopia (; Amharic and Tigrinya: ኢትዮጵያ , , Oromo: Itoophiyaa, Somali: Itoobiya, Afar: ''Itiyoophiyaa''), was an empire that historica ...

in 1935, appealing for medical supplies to be sent to the Abyssinian troops. As the threat of war increased later in the decade, Lang became a strong supporter of the government's policy of appeasing the European dictators, declaring the Sunday after the Munich Agreement

The Munich Agreement ( cs, Mnichovská dohoda; sk, Mníchovská dohoda; german: Münchner Abkommen) was an agreement concluded at Munich on 30 September 1938, by Germany, the United Kingdom, France, and Italy. It provided "cession to Germany ...

of September 1938 to be a day of thanksgivings for the "sudden lifting of this cloud". Earlier that year, contrary to his former stance, he had supported the Anglo-Italian agreement to recognise the conquest of Abyssinia, because he believed that "an increase of appeasement" was necessary to avoid the threat of war. Lang also backed the government's non-intervention policy in regard to the Spanish Civil War

The Spanish Civil War ( es, Guerra Civil Española)) or The Revolution ( es, La Revolución, link=no) among Nationalists, the Fourth Carlist War ( es, Cuarta Guerra Carlista, link=no) among Carlism, Carlists, and The Rebellion ( es, La Rebeli ...

, saying that there were no clear issues that required the taking of sides. He described the bombing of Guernica

On 26 April 1937, the Basque town of Guernica (''Gernika'' in Basque) was aerial bombed during the Spanish Civil War. It was carried out at the behest of Francisco Franco's rebel Nationalist faction by its allies, the Nazi German Luftwaff ...

by the Germans and the Italians, on 26 April 1937, as "deplorable and shocking". In October 1937 Lang's condemnation of Imperial Japanese Army actions in China provoked hostile scrutiny by the Japanese authorities of the Anglican Church in Japan

The ''Nippon Sei Ko Kai'' ( ja, 日本聖公会, translit=Nippon Seikōkai, lit=Japanese Holy Catholic Church), abbreviated as NSKK, sometimes referred to in English as the Anglican Episcopal Church in Japan, is the national Christian church rep ...

, and caused some in that church's leadership to publicly disassociate themselves from the Church of England.

On the domestic front, Lang supported campaigns for the abolition of the death penalty. He upheld the right of the Church to refuse the remarriage of divorced persons within its buildings,Lockhart, p. 378 but he did not directly oppose A.P. Herbert's Matrimonial Causes Bill of 1937, which liberalised the divorce laws – Lang believed "it was no longer possible to impose the full Christian standard by law on a largely non-Christian population." He drew criticism for his opposition to the reform of the ancient tithe

A tithe (; from Old English: ''teogoþa'' "tenth") is a one-tenth part of something, paid as a contribution to a religious organization or compulsory tax to government. Today, tithes are normally voluntary and paid in cash or cheques or more ...