Conyers Middleton on:

[Wikipedia]

[Google]

[Amazon]

Conyers Middleton (27 December 1683 – 28 July 1750) was an English clergyman. Mired in controversy and disputes, he was also considered one of the best stylists in English of his time.

His '' Life of Cicero'' (1741) was largely told in the words of the writings of

His '' Life of Cicero'' (1741) was largely told in the words of the writings of

Early life

Middleton was born atRichmond, North Yorkshire

Richmond is a market town and civil parish in North Yorkshire, England, and the administrative centre of the district of Richmondshire. Historically in the North Riding of Yorkshire, it is from the county town of Northallerton and situated on ...

, in 1683. His mother, Barbara Place (d. 1700), was the second wife of William Middleton (c.1646–1714), the rector of Hinderwell. Conyers Middleton had two brothers and a half-brother.

Middleton was educated at The Minster School, York

The Minster School was an independent preparatory school for children aged 3–13 in York, England. It was founded to educate choristers at York Minster and continued to do so, although no longer exclusively, until in June 2020 it was announced ...

, before entering Trinity College, Cambridge

Trinity College is a constituent college of the University of Cambridge. Founded in 1546 by King Henry VIII, Trinity is one of the largest Cambridge colleges, with the largest financial endowment of any college at either Cambridge or Oxford. ...

, in March 1699. He graduated with a BA in 1703. He was elected a fellow of the college in 1705 and took his MA in 1706 In 1707 he was ordained a deacon, and a priest in 1708.

In 1710 Dr. Middleton married Sarah Morris, the daughter of Thomas Morris (died 1717) of Mount Morris, Monks Horton, Hythe, Kent, and widow of Councillor and recorder Robert Drake of Cambridge (died 1702), of the family Drake of Ash. In due course Elizabeth Montagu (1718-1800) became a step-grand-daughter.

Dispute with Bentley

Middleton was one of the thirty fellows of Trinity College who on 6 February 1710 petitioned theBishop of Ely

The Bishop of Ely is the ordinary of the Church of England Diocese of Ely in the Province of Canterbury. The diocese roughly covers the county of Cambridgeshire (with the exception of the Soke of Peterborough), together with a section of nor ...

, as visitor of the college, to take steps against Richard Bentley

Richard Bentley FRS (; 27 January 1662 – 14 July 1742) was an English classical scholar, critic, and theologian. Considered the "founder of historical philology", Bentley is widely credited with establishing the English school of Hellen ...

the Master, at odds with the fellowship. In 1717, he became involved in a dispute with Bentley over the awarding of degrees. George I visited the university, and the degree of Doctor of Divinity

A Doctor of Divinity (D.D. or DDiv; la, Doctor Divinitatis) is the holder of an advanced academic degree in divinity.

In the United Kingdom, it is considered an advanced doctoral degree. At the University of Oxford, doctors of divinity are ran ...

was conferred on 32 people, including Middleton. Bentley, as regius professor of divinity, demanded a fee of four guinea

Guinea ( ),, fuf, 𞤘𞤭𞤲𞤫, italic=no, Gine, wo, Gine, nqo, ߖߌ߬ߣߍ߫, bm, Gine officially the Republic of Guinea (french: République de Guinée), is a coastal country in West Africa. It borders the Atlantic Ocean to the we ...

s from each of the new doctors in addition to the established complimentary " broad-piece". Middleton, after some dispute, consented to pay, taking Bentley's written promise to return the money if the claim should be finally disallowed. He was then created doctor. Having vainly applied for a return of the fee, he sued for it as a debt in the vice-chancellor's court. After various delays and attempts to make up the quarrel, the vice-chancellor issued a decree (23 September 1718) for Bentley's arrest. Bentley's refusal to submit to this decree led to further proceedings, and to his degradation from all his degrees by a grace of the senate on 18 October.

The matter was then pursued in a pamphlet war and Bentley brought an action against the publisher of the anonymous ''On the Present State of Trinity College'' (1719), which was the work of Middleton with John Colbatch. Middleton claimed (9 February 1720) the pamphlet as his own; Bentley continued to prosecute the bookseller, until Middleton made a declaration of his authorship before witnesses. Bentley then laid an information against him in the King's Bench, based on a passage in the pamphlet about the impossibility of obtaining redress in "any proper court of justice in the kingdom". The proceedings were slow, and meanwhile Middleton took advantage of Bentley's proposals for an edition of the New Testament to attack him in a sharp pamphlet. Bentley replied, using terms of gross abuse directed mainly against Colbatch, to whom he chose to attribute the authorship. Bentley's reply was condemned by the Cambridge heads of houses. Colbatch brought an action against him, and Middleton wrote a longer and more temperate rejoinder (possibly helped by Charles Ashton).

When Middleton's case was heard in the court of king's bench (Trinity term 1721), he was found guilty of libel. Sentence was delayed. Friends subscribed towards his expenses, and he obtained the intercession of a highly placed person for a lenient sentence. The chief justice John Pratt John Pratt may refer to:

*John Pratt (judge) (1657–1725), Lord Chief Justice of England and interim Chancellor of the Exchequer

*John Pratt (soldier) (1753–1824), United States Army officer

*John Pratt, 1st Marquess Camden (1759–1840), Britis ...

advised the two doctors to avoid scandal by a compromise, and Bentley finally accepted an apology. Middleton, however, had to pay his own costs, and expenses of his opponent.

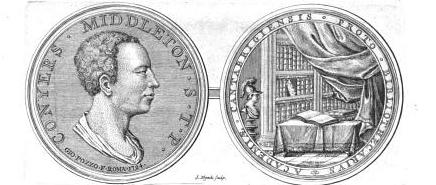

The dispute flared up again, to end on a note of bathos. Middleton's supporters (14 December 1721), passed a vote through the university Senate making him a librarian—a salaried "Protobibliothecarius" of the university library—a new post, on the pretext of the king's recent donation of Bishop John Moore's library. Middleton in 1723 published a plan for the future arrangement of the books; but with swipes at Bentley for retaining some manuscripts (the ''Codex Bezæ

The Codex Bezae Cantabrigiensis, designated by siglum D or 05 (in the Gregory-Aland numbering of New Testament manuscripts), δ 5 (in the von Soden of New Testament manuscript), is a codex of the New Testament dating from the 5th century writt ...

'' among them) in his own house, and on the court of king's bench. Bentley appealed to the court, and on 20 June 1723 Middleton was fined, and ordered to provide securities for good behaviour for a year. Middleton went off to Italy. On his return he renewed his old suit for the four guineas. Bentley did not oppose him, and in February 1726 Middleton at last got back his fee, together with 12''s''. costs.

Later life

Middleton stayed in Rome during a great part of 1724 and 1725.Henry Hare, 3rd Baron Coleraine

Henry Hare, 3rd Baron Coleraine FRS; FSA (10 May 1693 – 1 August 1749) was an English antiquary, peer politician who sat in the House of Commons from 1730 to 1734.

Life

Born in Betchworth, Surrey, 10 May 1693, he was the eldest son of ...

, a fellow collector, was his companion on this journey. Middleton made a collection of antiquities, of which he later published a description; he sold it to Horace Walpole

Horatio Walpole (), 4th Earl of Orford (24 September 1717 – 2 March 1797), better known as Horace Walpole, was an English writer, art historian, man of letters, antiquarian, and Whig politician.

He had Strawberry Hill House built in Twi ...

in 1744.

His first wife, Sarah Morris, died on 19 February 1731. In 1731 Middleton was appointed first Woodwardian Professor of Geology, and delivered an inaugural address in Latin, pointing out the benefits which might be expected from a study of fossils in confirming the history of Noah's Flood. He resigned the chair in 1734, on his second marriage.

Middleton's sceptical tendency became clearer, and Zachary Pearce accused him of covert infidelity. He was threatened with a loss of his Cambridge degrees. Middleton replied in two pamphlets, making such explanations as he could. In 1733, however, an anonymous pamphlet (by Philip Williams the public orator) declared that his books ought to be burnt and he should be banished from the university, unless he made a recantation. Middleton made an explanation in a final pamphlet, but for some time remained silent on theological topics. His relationship with Edward Harley, 2nd Earl of Oxford

Edward Harley, 2nd Earl of Oxford and Earl Mortimer (2 June 1689 – 16 June 1741), styled Lord Harley between 1711 and 1724, was a British politician, bibliophile, collector and patron of the arts.

Background

Harley was the only son of Robe ...

, was damaged.

Middleton's major work, his ''Life of Cicero'' (1741), was a success. He was attacked by Samuel Parr in 1787, however, for knowing plagiarism

Plagiarism is the fraudulent representation of another person's language, thoughts, ideas, or expressions as one's own original work.From the 1995 '' Random House Compact Unabridged Dictionary'': use or close imitation of the language and though ...

: Parr claimed it was based on ''De tribus luminibus Romanorum'', a scarce work by William Bellenden

William Bellenden (c. 1550c. 1633) was a Scottish classical scholar.

James I of England and Ireland; VI of Scotland appointed him ''magister libellorum supplicum'' or master of requests. King James is also said to have provided Bellenden with t ...

. Middleton's second wife Mary died in 1745, and he returned to controversial theology in 1747. He looked for ecclesiastical preferment, but was unpopular with the bishops.

Middleton lived at Hildersham

Hildersham is a small village 8 miles to the south-east of Cambridge, England. It is situated just off the A1307 between Linton and Great Abington on a tributary of the River Cam known locally as the River Granta.

The parish boundary extend ...

, near Cambridge, and married again shortly before he died, on 28 July 1750.

Works

A modern opinion is thatMiddleton stood out as an especially lethal species of the polemical divine. At best sarcastic and withering, at worst poisonous and unfair, Middleton justly deserved his reputation ..On the other hand,

Alexander Pope

Alexander Pope (21 May 1688 O.S. – 30 May 1744) was an English poet, translator, and satirist of the Enlightenment era who is considered one of the most prominent English poets of the early 18th century. An exponent of Augustan literature, ...

thought he and Nathaniel Hooke were the only prose writers of the day who deserved to be cited as authorities on the language. Samuel Parr, while exposing Middleton's plagiarisms, praised his style. An edition of his works, containing several posthumous tracts, but not including the ''Life of Cicero'', appeared in four volumes in 1752, and in five volumes in 1755.

Early works

The pamphlets from the struggle with Bentley were: *''A full and impartial Account of all the late Proceedings … against Dr. Bentley'', 1719. *''Second Part'' of the above, 1719. *''Some Remarks upon a Pamphlet entitled “The Case of Dr. Bentley further stated and vindicated” …'', 1719. *''A True Account of the Present State of Trinity College in Cambridge under the oppressive rule of their Master, Richard Bentley, late D.D.'', 1720. *''Remarks, paragraph by paragraph, upon the Proposals lately published by Richard Bentley for a new Edition of the Greek Testament and Latin Version'', 1721. *''Some further Remarks … containing a full Answer to the Editor's late Defence …'', 1721. *''Bibliothecæ Cantabrigiensis ordinandæ Methodus quædam …'', 1723. Middleton visited Italy, and drew conclusions on thepagan

Paganism (from classical Latin ''pāgānus'' "rural", "rustic", later "civilian") is a term first used in the fourth century by early Christians for people in the Roman Empire who practiced polytheism, or ethnic religions other than Judaism. I ...

origin of Christian church ceremonies and beliefs; he subsequently published these in his ''Letter from Rome, showing an Exact Conformity between Popery and Paganism'' (1729). This work led to an attack from the Catholic side by Richard Challoner, in the preface to ''The Catholic Christian instructed in the Sacraments, Sacrifice and Ceremonies of the Church'' (1737); Challoner in particular accused Middleton of misrepresenting the articles of the Tridentine Creed

The Council of Trent ( la, Concilium Tridentinum), held between 1545 and 1563 in Trent (or Trento), now in northern Italy, was the 19th ecumenical council of the Catholic Church. Prompted by the Protestant Reformation, it has been described ...

that applied to saints and images. Middleton retaliated through the legal system, and Challoner in 1738 left for Douai

Douai (, , ,; pcd, Doï; nl, Dowaai; formerly spelled Douay or Doway in English) is a city in the Nord département in northern France. It is a sub-prefecture of the department. Located on the river Scarpe some from Lille and from Arras, Dou ...

. Thomas Seward wrote further on the subject in a 1746 "sequel" to Middleton and Henry Mower (i.e. More).

Controversy with the medical profession

In 1726, prompted by theHarveian Oration

The Harveian Oration is a yearly lecture held at the Royal College of Physicians of London. It was instituted in 1656 by William Harvey, discoverer of the systemic circulation. Harvey made financial provision for the college to hold an annual fea ...

by Richard Mead

Richard is a male given name. It originates, via Old French, from Old Frankish and is a compound of the words descending from Proto-Germanic ''*rīk-'' 'ruler, leader, king' and ''*hardu-'' 'strong, brave, hardy', and it therefore means 'str ...

, with an appendix by Edmund Chishull

Edmund Chishull (1671–1733) was an English clergyman and antiquary.

Life

He was son of Paul Chishull, and was born at Eyworth, Bedfordshire, 22 March 1670–1.

He was a scholar of Corpus Christi College, Oxford in 1687, where he graduated B.A. ...

, Middleton offended the medical profession with a dissertation contending that the healing art among the ancients was exercised only by slaves or freedmen. He was answered by John Ward, Joseph Letherland, and others, to whom Middleton replied. Middleton let the matter drop after meeting Mead socially; but two related works, an ''Appendix seu Definitiones, pars secunda'' and a letter from Middleton to another opponent, Charles La Motte, were later published in 1761 by William Heberden the elder

William Heberden FRS (13 August 171017 May 1801) was an English physician.

Life

He was born in London, where he received the early part of his education at St Saviour's Grammar School. Full text at Internet Archive (archive.org) At the end of ...

.

Deistic controversy

Middleton had remonstrated withDaniel Waterland

Daniel Cosgrove Waterland (14 March 1683 – 23 December 1740) was an English theologian. He became Master of Magdalene College, Cambridge in 1714, Chancellor of the Diocese of York in 1722, and Archdeacon of Middlesex in 1730.

Waterland opposed ...

when the latter replied to Matthew Tindal's ''Christianity as Old as the Creation''. Middleton took a line which exposed him to the reproach of infidelity. In professing to indicate a short and easy method of confuting Tindal, he laid emphasis on the indispensableness of Christianity as a mainstay of social order. This brought him into conflict with those who held the same views as Waterland. Middleton was attacked from many quarters, and produced several apologetic pamphlets. His letter to Waterland from Rome, however, hinted that Middleton himself was active in Deism

Deism ( or ; derived from the Latin ''deus'', meaning " god") is the philosophical position and rationalistic theology that generally rejects revelation as a source of divine knowledge, and asserts that empirical reason and observation o ...

. Middleton wrote "Deity can be conceived to interpose himself; the universal good and salvation of man."

Classical scholarship

His '' Life of Cicero'' (1741) was largely told in the words of the writings of

His '' Life of Cicero'' (1741) was largely told in the words of the writings of Cicero

Marcus Tullius Cicero ( ; ; 3 January 106 BC – 7 December 43 BC) was a Roman statesman, lawyer, scholar, philosopher, and academic skeptic, who tried to uphold optimate principles during the political crises that led to the esta ...

. Middleton's reputation was enhanced by this work; but, as was later pointed out, he drew largely from a rare book by William Bellenden

William Bellenden (c. 1550c. 1633) was a Scottish classical scholar.

James I of England and Ireland; VI of Scotland appointed him ''magister libellorum supplicum'' or master of requests. King James is also said to have provided Bellenden with t ...

, ''De tribus luminibus Romanorum''. The work was undertaken at the request of John Hervey, 2nd Baron Hervey

John Hervey, 2nd Baron Hervey, (13 October 16965 August 1743) was an English courtier and political writer. Heir to the Earl of Bristol, he obtained the key patronage of Walpole, and was involved in many court intrigues and literary quarrel ...

; from their correspondence came the idea for ''The Roman Senate'', published in 1747.

Middletonian controversy on miraculous powers

The years 1747–8 produced Middleton's most significant theological writings. The ''Introductory Discourse and the Free Inquiry'' addressed "the miraculous powers which are supposed to have subsisted in the church from the earliest ages." Middleton suggested two propositions: that ecclesiastical miracles must be accepted or rejected in the mass; and that there is a distinction between the authority due to the earlyChurch Fathers

The Church Fathers, Early Church Fathers, Christian Fathers, or Fathers of the Church were ancient and influential Christian theologians and writers who established the intellectual and doctrinal foundations of Christianity. The historical per ...

' testimony to the beliefs and practices of their times, and their credibility as witnesses to matters of fact. In 1750, he attacked Thomas Sherlock

Thomas Sherlock (167818 July 1761) was a British divine who served as a Church of England bishop for 33 years. He is also noted in church history as an important contributor to Christian apologetics.

Life

Born in London, he was the son of the ...

's notions of antediluvian prophecy, which had been published 25 years before. Among those who answered, or defended Sherlock, were: Thomas Ashton Thomas Ashton may refer to:

*Thomas Ashton (schoolmaster) (died 1578), English clergyman and schoolmaster

*Thomas Ashton (divine) (1716–1775), English cleric

*Thomas Ashton (cotton spinner) (1841–1919), British trade union leader

*Thomas Ashto ...

; Julius Bate; Anselm Bayly; Zachary Brooke; Thomas Church; Joseph Clarke; William Cooke; William Dodwell

William Dodwell (1709–1785) was an English cleric known as a theological writer, archdeacon of Berkshire from 1763.

Life

He was born at Shottesbrooke, Berkshire, on 17 June 1709, was the second son and fifth child of Henry Dodwell the elder, the ...

; Ralph Heathcote; John Jackson; Laurence Jackson; John Rotheram; Thomas Rutherforth

Thomas Rutherforth (also Rutherford) (1712–1771) was an English churchman and academic, Regius Professor of Divinity at Cambridge from 1745, and Archdeacon of Essex from 1752.

Life

He was the son of Thomas Rutherforth, rector of Papworth Everar ...

; and Thomas Secker. Methodist

Methodism, also called the Methodist movement, is a group of historically related denominations of Protestant Christianity whose origins, doctrine and practice derive from the life and teachings of John Wesley. George Whitefield and John's ...

founder John Wesley

John Wesley (; 2 March 1791) was an English cleric, theologian, and evangelist who was a leader of a revival movement within the Church of England known as Methodism. The societies he founded became the dominant form of the independent Meth ...

wrote an extensive response to Middleton recording his disagreement with him in January 1749.

'' Reflections on the variations, or inconsistencies, which are found among the four Evangelists'' was posthumous, published in 1752.

Family

Although Middleton died childless, he married three times. *firstly, in 1710, to Sarah Drake, the widow of Counsellor Drake of Cambridge, and daughter of Mr. Morris of Oak Morris in Kent; *secondly, in 1734, to his cousin Mary, daughter of the Rev. Conyers Place of Dorchester, who died 26 April 1745, aged 38; *thirdly, at the end of his life, to Anne, daughter of John Powell ofBoughrood

Boughrood ( cy, Bochrwyd) is a village in the community of Glasbury in Powys, Wales.

Historically in Radnorshire, the village is situated near the River Wye between Hay-on-Wye and Builth Wells.

The River Wye passes to the west and north of ...

, in Radnorshire

, HQ = Presteigne

, Government = Radnorshire County Council (1889–1974) Radnorshire District Council (1974–1996)

, Origin =

, Status = historic county, administrative county

, Start ...

, who had lived as a companion to Mrs. Trenchard, widow of John Trenchard, later married to Thomas Gordon.

Elizabeth Montagu was a granddaughter of Sarah Drake, and she spent much time as a child with the Middletons in Cambridge, as did her sister Sarah Scott.

References

* Sir Leslie Stephen, ''English Thought in the Eighteenth Century'', ch. vi.Notes

;Attribution {{DEFAULTSORT:Middleton, Conyers English Christian theologians 18th-century English Anglican priests Christian writers British deists Doctors of Divinity 1683 births 1750 deaths Cambridge University Librarians Fellows of Trinity College, Cambridge Woodwardian Professors of Geology