Continental pole of inaccessibility on:

[Wikipedia]

[Google]

[Amazon]

A pole of inaccessibility with respect to a

A pole of inaccessibility with respect to a

The southern pole of inaccessibility is the point on the

The southern pole of inaccessibility is the point on the

The oceanic pole of inaccessibility, also known as Point Nemo, is located at roughly and is the place in the ocean that is farthest from land. It represents the solution to the "longest swim" problem. This problem poses that there is one place in an ocean on earth where, if a person fell overboard while on a ship at sea, they would be at a point that is the longest distance to any land in any direction. It lies in the

The oceanic pole of inaccessibility, also known as Point Nemo, is located at roughly and is the place in the ocean that is farthest from land. It represents the solution to the "longest swim" problem. This problem poses that there is one place in an ocean on earth where, if a person fell overboard while on a ship at sea, they would be at a point that is the longest distance to any land in any direction. It lies in the

In

In

In

In

How to calculate PIAs

Team N2i successfully conquer the Pole of Inaccessibility by foot and kite on 19th Jan '07

{{DEFAULTSORT:Pole Of Inaccessibility Lists of coordinates Polar regions of the Earth Geography of the Arctic Geography of Antarctica Extreme points of Earth

A pole of inaccessibility with respect to a

A pole of inaccessibility with respect to a geographical

Geography (from Greek: , ''geographia''. Combination of Greek words ‘Geo’ (The Earth) and ‘Graphien’ (to describe), literally "earth description") is a field of science devoted to the study of the lands, features, inhabitants, and ...

criterion of inaccessibility marks a location that is the most challenging to reach according to that criterion. Often it refers to the most distant point from the coastline

The coast, also known as the coastline or seashore, is defined as the area where land meets the ocean, or as a line that forms the boundary between the land and the coastline. The Earth has around of coastline. Coasts are important zones in ...

, implying a maximum degree of continent

A continent is any of several large landmasses. Generally identified by convention rather than any strict criteria, up to seven geographical regions are commonly regarded as continents. Ordered from largest in area to smallest, these seven ...

ality or ocean

The ocean (also the sea or the world ocean) is the body of salt water that covers approximately 70.8% of the surface of Earth and contains 97% of Earth's water. An ocean can also refer to any of the large bodies of water into which the wor ...

ity. In these cases, a pole of inaccessibility can be defined as the center of the largest circle that can be drawn within an area of interest without encountering a coast. Where a coast is imprecisely defined, the pole will be similarly imprecise.

Northern pole of inaccessibility

The Northern pole of inaccessibility, sometimes known as the Arctic pole, is located on theArctic Ocean

The Arctic Ocean is the smallest and shallowest of the world's five major oceans. It spans an area of approximately and is known as the coldest of all the oceans. The International Hydrographic Organization (IHO) recognizes it as an ocean, a ...

pack ice

Drift ice, also called brash ice, is sea ice that is not attached to the shoreline or any other fixed object (shoals, grounded icebergs, etc.).Leppäranta, M. 2011. The Drift of Sea Ice. Berlin: Springer-Verlag. Unlike fast ice, which is "faste ...

at a distance farthest from any land mass. The original position was wrongly believed to lie at 84°03′N 174°51′W. It is not clear who first defined this point but it may have been Sir Hubert Wilkins

Sir George Hubert Wilkins MC & Bar (31 October 188830 November 1958), commonly referred to as Captain Wilkins, was an Australian polar explorer, ornithologist, pilot, soldier, geographer and photographer. He was awarded the Military Cross afte ...

, who wished to traverse the Arctic Ocean by aircraft

An aircraft is a vehicle that is able to flight, fly by gaining support from the Atmosphere of Earth, air. It counters the force of gravity by using either Buoyancy, static lift or by using the Lift (force), dynamic lift of an airfoil, or in ...

, in 1927. He was finally successful in 1928. In 1968 Sir Wally Herbert came very close to reaching what was then considered to be the position by dogsled but by his own account, "Across The Roof Of The World", did not make it due to the flow of sea ice. In 1986, an expedition of Soviet polar scientists led by Dmitry Shparo claimed to reach the original position by foot during a polar night.

In 2005, explorer Jim McNeill

Jim McNeill is a former scientist and British polar explorer, presenter and keynote speaker, with over 36 years of experience travelling and working in the polar regions.

In 2001 McNeill founded Ice Warrior Project, an organisation which gives " ...

asked scientists from National Snow and Ice Data Center

The National Snow and Ice Data Center (NSIDC) is a United States information and referral center in support of polar and cryospheric research. NSIDC archives and distributes digital and analog snow and ice data and also maintains information abo ...

and Scott Polar Research Institute

The Scott Polar Research Institute (SPRI) is a centre for research into the polar regions and glaciology worldwide. It is a sub-department of the Department of Geography in the University of Cambridge, located on Lensfield Road in the south ...

to re-establish the position using modern GPS and satellite technology. This was published as a paper in the Polar Record, Cambridge University Press

Cambridge University Press is the university press of the University of Cambridge. Granted letters patent by King Henry VIII in 1534, it is the oldest university press in the world. It is also the King's Printer.

Cambridge University Pr ...

in 2013. McNeill launched his own, unsuccessful, attempt to reach the new position in 2006, whilst measuring the depth of sea-ice for NASA

The National Aeronautics and Space Administration (NASA ) is an independent agency of the US federal government responsible for the civil space program, aeronautics research, and space research.

NASA was established in 1958, succeedin ...

. In 2010 he and his Ice Warrior

The Ice Warriors are a fictional extraterrestrial race of reptilian humanoids in the long-running British science fiction television series ''Doctor Who''. They were originally created by Brian Hayles, first appearing in the 1967 serial ''The ...

team were thwarted again by the poor condition of the sea ice.

The new position lies at 85°48′N 176°9′W, 1,008 km (626 mi) from the three closest landmasses: It is 1008 km from the nearest land, on Henrietta Island

Henrietta Island ( rus, Остров Генриетты, r=Ostrov Genriyetty; sah, Хенриетта Aрыыта, translit=Xenriyetta Arııta) is the northernmost island of the De Long archipelago in the East Siberian Sea. Administratively i ...

in the De Long Islands

The De Long Islands ( rus, Острова Де-Лонга, r=Ostrova De-Longa; sah, Де Лоҥ Aрыылара, translit=De Loñ Arıılara) are an uninhabited archipelago often included as part of the New Siberian Islands, lying north east of ...

, at Arctic Cape

The Arctic Cape (russian: Мыс Арктический, ''Mys Arkticheskiy'') is a headland in Severnaya Zemlya, Russia.

With a distance of 990.8 km to the North Pole, the Arctic Cape is sometimes used as starting point for expeditions to ...

on Severnaya Zemlya

Severnaya Zemlya (russian: link=no, Сéверная Земля́ (Northern Land), ) is a archipelago in the Russian high Arctic. It lies off Siberia's Taymyr Peninsula, separated from the mainland by the Vilkitsky Strait. This archipelago ...

, and on Ellesmere Island

Ellesmere Island ( iu, script=Latn, Umingmak Nuna, lit=land of muskoxen; french: île d'Ellesmere) is Canada's northernmost and third largest island, and the tenth largest in the world. It comprises an area of , slightly smaller than Great Br ...

. It is over 200 km from the originally accepted position. Due to constant motion of the pack ice, no permanent structure can exist at this pole. As of February 2021, McNeill said that, as far as he could ascertain, no one had reached the new position of the Northern Pole of Inaccessibility - certainly not from the last landfall across the surface of the ocean and it remains an important scientific transect.

Southern pole of inaccessibility

Antarctic

The Antarctic ( or , American English also or ; commonly ) is a polar region around Earth's South Pole, opposite the Arctic region around the North Pole. The Antarctic comprises the continent of Antarctica, the Kerguelen Plateau and othe ...

continent most distant from the Southern Ocean

The Southern Ocean, also known as the Antarctic Ocean, comprises the southernmost waters of the World Ocean, generally taken to be south of 60° S latitude and encircling Antarctica. With a size of , it is regarded as the second-smal ...

. A variety of coordinate locations have been given for this pole. The discrepancies are due to the question of whether the "coast" is measured to the grounding line or to the edges of ice shelves, the difficulty of determining the location of the "solid" coastline, the movement of ice sheets and improvements in the accuracy of survey data over the years, as well as possible topographical errors.

The pole of inaccessibility commonly refers to the site of the Soviet Union research station mentioned below, which was constructed at (though some sources give ). This lies from the South Pole

The South Pole, also known as the Geographic South Pole, Terrestrial South Pole or 90th Parallel South, is one of the two points where Earth's axis of rotation intersects its surface. It is the southernmost point on Earth and lies antipod ...

, at an elevation

The elevation of a geographic location is its height above or below a fixed reference point, most commonly a reference geoid, a mathematical model of the Earth's sea level as an equipotential gravitational surface (see Geodetic datum § ...

of . Using different criteria, the Scott Polar Research Institute

The Scott Polar Research Institute (SPRI) is a centre for research into the polar regions and glaciology worldwide. It is a sub-department of the Department of Geography in the University of Cambridge, located on Lensfield Road in the south ...

locates this pole at .

Using recent datasets and cross-confirmation between the adaptive gridding and B9-Hillclimbing methods discussed below, Rees et al. (2021) identify two poles of inaccessibility for Antarctica: an "outer" pole defined by the edge of Antarctica's floating ice shelves and an "inner" pole defined by the grounding lines of these sheets. They find the Outer pole to be at , from the ocean, and the Inner pole to be at , from the grounding lines.

The southern pole of inaccessibility is far more remote and difficult to reach than the geographic South Pole

The South Pole, also known as the Geographic South Pole, Terrestrial South Pole or 90th Parallel South, is one of the two points where Earth's axis of rotation intersects its surface. It is the southernmost point on Earth and lies antipod ...

. On 14 December 1958, the 3rd Soviet Antarctic Expedition for International Geophysical Year

The International Geophysical Year (IGY; french: Année géophysique internationale) was an international scientific project that lasted from 1 July 1957 to 31 December 1958. It marked the end of a long period during the Cold War when scientific i ...

research work, led by Yevgeny Tolstikov

Yevgeny Ivanovich Tolstikov (russian: Евгений Иванович Толстиков; 9 February 1913 – 3 December 1987) was a Soviet polar explorer who was awarded the title Hero of the Soviet Union in 1955 for heading the station "North Po ...

, established the temporary Pole of Inaccessibility Station (''Polyus Nedostupnosti'') at . A second Russian team returned there in 1967. Today, a building still remains at this location, marked by a bust of Vladimir Lenin

Vladimir Ilyich Ulyanov. ( 1870 – 21 January 1924), better known as Vladimir Lenin,. was a Russian revolutionary, politician, and political theorist. He served as the first and founding head of government of Soviet Russia from 1917 to 1 ...

that faces towards Moscow

Moscow ( , US chiefly ; rus, links=no, Москва, r=Moskva, p=mɐskˈva, a=Москва.ogg) is the capital and largest city of Russia. The city stands on the Moskva River in Central Russia, with a population estimated at 13.0 million ...

, and protected as a historical site.

On 11 December 2005, at 7:57 UTC, Ramón Hernando de Larramendi, Juan Manuel Viu, and Ignacio Oficialdegui, members of the Spanish Transantarctic Expedition, reached for the first time in history the southern pole of inaccessibility at , updated that year by the British Antarctic Survey. The team continued their journey towards the second southern pole of inaccessibility, the one that accounts for the ice shelves as well as the continental land, and they were the first expedition to reach it, on 14 December 2005, at . Both achievements took place within an ambitious pioneer crossing of the eastern Antarctic Plateau that started at Novolazarevskaya Station

Novolazarevskaya Station (russian: Станция Новолазаревская) is a Russian, formerly Soviet, Antarctic research station. The station is located at Schirmacher Oasis, Queen Maud Land, from the Antarctic coast, from which it is ...

and ended at Progress Base after more than . This was the fastest polar journey ever achieved without mechanical aid, with an average rate of around per day and a maximum of per day, using kites as their power source.

On 4 December 2006, Team N2i, consisting of Henry Cookson

Henry John R Cookson, FRGS (born 16 September 1975) is a British polar explorer and adventurer. On 19 January 2007 he, alongside fellow Britons Rory Sweet and Rupert Longsdon, and their Canadian polar guide Paul Landry, became the first team to ...

, Rupert Longsdon, Rory Sweet and Paul Landry

Paul Landry M.B. (born September 6, 1955) is a French-Canadian polar explorer, author, and adventurer who is the only paid man to ever reach three Geographical poles in a single year.

Biography

A Franco-Ontarian from Smooth Rock Falls in the No ...

, embarked on an expedition to be the first to reach the historic pole of inaccessibility location without direct mechanical assistance, using a combination of traditional man hauling and kite skiing

Snowkiting or kite skiing is an outdoor winter sport where people use kite power to glide on snow or ice. The skier uses a kite to give them power over large jumps. The sport is similar to water-based kiteboarding, but with the footwear used in ...

. The team reached the old abandoned station on 19 January 2007, rediscovering the forgotten statue of Lenin left there by the Soviets some 48 years previously. The team found that only the bust on top of the building remained visible; the rest was buried under the snow. The explorers were picked up from the spot by a plane from Vostok base, flown to Progress Base and taken back to Cape Town

Cape Town ( af, Kaapstad; , xh, iKapa) is one of South Africa's three capital cities, serving as the seat of the Parliament of South Africa. It is the legislative capital of the country, the oldest city in the country, and the second largest ...

on the ''Akademik Fyodorov

RV ''Akademik Fedorov'' (russian: Академик Фёдоров) is a Russian scientific diesel-electric research vessel, the flagship of the Russian polar research fleet. It was built in Rauma, Finland for the Soviet Union and completed on ...

'', a Russian polar research vessel.

On 27 December 2011, Sebastian Copeland

Sebastian Copeland (born 3 April 1964) is a British-American-French photographer, polar explorer, author, lecturer, and environmental advocate. He has led numerous expeditions in the polar regions to photograph and film endangered environments. In ...

and partner Eric McNair-Laundry also reached the southern pole of inaccessibility. They were the first to do so without resupply or mechanical support, departing from Novolazarevskaya Station

Novolazarevskaya Station (russian: Станция Новолазаревская) is a Russian, formerly Soviet, Antarctic research station. The station is located at Schirmacher Oasis, Queen Maud Land, from the Antarctic coast, from which it is ...

on their way to the South Pole

The South Pole, also known as the Geographic South Pole, Terrestrial South Pole or 90th Parallel South, is one of the two points where Earth's axis of rotation intersects its surface. It is the southernmost point on Earth and lies antipod ...

to complete the first East/West crossing of Antarctica through both poles, over .

As mentioned above, due to improvements in technology and the position of the continental edge of Antarctica being debated, the exact position of the best estimate of the pole of inaccessibility may vary. However, for the convenience of sport expeditions, a fixed point is preferred, and the Soviet station has been used for this role. This has been recognized by ''Guinness World Records

''Guinness World Records'', known from its inception in 1955 until 1999 as ''The Guinness Book of Records'' and in previous United States editions as ''The Guinness Book of World Records'', is a reference book published annually, listing world ...

'' for Team N2i's expedition in 2006–2007.

Oceanic pole of inaccessibility

The oceanic pole of inaccessibility, also known as Point Nemo, is located at roughly and is the place in the ocean that is farthest from land. It represents the solution to the "longest swim" problem. This problem poses that there is one place in an ocean on earth where, if a person fell overboard while on a ship at sea, they would be at a point that is the longest distance to any land in any direction. It lies in the

The oceanic pole of inaccessibility, also known as Point Nemo, is located at roughly and is the place in the ocean that is farthest from land. It represents the solution to the "longest swim" problem. This problem poses that there is one place in an ocean on earth where, if a person fell overboard while on a ship at sea, they would be at a point that is the longest distance to any land in any direction. It lies in the South Pacific Ocean

South is one of the cardinal directions or compass points. The direction is the opposite of north and is perpendicular to both east and west.

Etymology

The word ''south'' comes from Old English ''sūþ'', from earlier Proto-Germanic ''*sunþaz ...

, and is equally distant from the three closest land vertices which are each roughly away. Those vertices are Pandora, an islet that, along with others forms the Ducie Island

Ducie Island is an uninhabited atoll in the Pitcairn Islands. It lies east of Pitcairn Island, and east of Henderson Island, and has a total area of , which includes the lagoon. It is long, measured northeast to southwest, and about wide. ...

Atoll, (part of the Pitcairn Island

Pitcairn Island is the only inhabited island of the Pitcairn Islands, of which many inhabitants are descendants of mutineers of HMS ''Bounty''.

Geography

The island is of volcanic origin, with a rugged cliff coastline. Unlike many other ...

s) to the north; Motu Nui (part of the Easter Island

Easter Island ( rap, Rapa Nui; es, Isla de Pascua) is an island and special territory of Chile in the southeastern Pacific Ocean, at the southeasternmost point of the Polynesian Triangle in Oceania. The island is most famous for its nearl ...

s) to the northeast; and Maher Island

Maher Island is a small horseshoe-shaped island lying north of the north-western end of Siple Island, off the coast of Marie Byrd Land, Antarctica. It is one of the three pieces of land closest to the Oceanic Pole of Inaccessibility, also known ...

(near the larger Siple Island

Siple Island is a long snow-covered island lying east of Wrigley Gulf along the Getz Ice Shelf off Bakutis Coast of Marie Byrd Land, Antarctica. Its centre is located at .

Its area is and it is dominated by the dormant shield volcano Mou ...

, off the coast of Marie Byrd Land

Marie Byrd Land (MBL) is an unclaimed region of Antarctica. With an area of , it is the largest unclaimed territory on Earth. It was named after the wife of American naval officer Richard E. Byrd, who explored the region in the early 20th centu ...

, Antarctica) to the south. The exact coordinates of Point Nemo depend on what the exact coordinates of these three islands are since the nature of the "longest swim" problem means that the ocean point is equally far from each.

The area is so remote that—as with any location more than 400 kilometres (about 250 miles) from an inhabited area—sometimes the closest human beings are astronauts aboard the International Space Station

The International Space Station (ISS) is the largest Modular design, modular space station currently in low Earth orbit. It is a multinational collaborative project involving five participating space agencies: NASA (United States), Roscosmos ( ...

when it passes overhead. Point Nemo was first discovered by survey engineer Hrvoje Lukatela in 1992. In 2022, Lukatela recalculated the coordinates of Point Nemo using Open Street Map data as well as Google Maps data in order to compare those results with the coordinates he first calculated using Digital Chart of the World {{unreferenced, date=July 2014

The Digital Chart of the World (DCW) is a comprehensive digital map of Earth. It is the most comprehensive geographical information system (GIS) global database that is freely available as of 2006, although it has no ...

data.

The point and the areas around it have attracted literary and cultural attention. It is known as Point Nemo, a reference to Jules Verne

Jules Gabriel Verne (;''Longman Pronunciation Dictionary''. ; 8 February 1828 – 24 March 1905) was a French novelist, poet, and playwright. His collaboration with the publisher Pierre-Jules Hetzel led to the creation of the '' Voyages extra ...

's Captain Nemo

Captain Nemo (; later identified as an Indian, Prince Dakkar) is a fictional character created by the French novelist Jules Verne (1828–1905). Nemo appears in two of Verne's science-fiction classics, ''Twenty Thousand Leagues Under the Seas'' ...

from the novel ''20,000 Leagues Under the Sea

''Twenty Thousand Leagues Under the Seas'' (french: Vingt mille lieues sous les mers) is a classic science fiction adventure novel by French writer Jules Verne.

The novel was originally serialized from March 1869 through June 1870 in Pierre-J ...

''. This novel was a childhood favorite of Lukatela's so he named it after Captain Nemo.

The general area plays a major role in the 1928 short story "The Call of Cthulhu

"The Call of Cthulhu" is a short story by American writer H. P. Lovecraft. Written in the summer of 1926, it was first published in the pulp magazine ''Weird Tales'' in February 1928.

Inspiration

The first seed of the story's first chapter '' ...

" by H. P. Lovecraft, as holding the location of the fictional city of R'lyeh

R'lyeh is a fictional lost city that was first mentioned in the H. P. Lovecraft short story "The Call of Cthulhu", first published in ''Weird Tales'' in February 1928. R'lyeh is a sunken city in the South Pacific and the prison of the entity calle ...

, although this story was written 66 years before the identification of Point Nemo. The area is nowadays known as a "spacecraft cemetery

The spacecraft cemetery, known more formally as the South Pacific Ocean(ic) Uninhabited Area, is a region in the southern Pacific Ocean east of New Zealand, where spacecraft that have reached the end of their usefulness are routinely crashed. Th ...

" because hundreds of decommissioned satellites, space stations, and other spacecraft have been made to fall there upon re-entering the atmosphere, to lessen the risk of hitting inhabited locations or maritime traffic. The International Space Station (ISS) is planned to crash into Point Nemo in 2031.

Point Nemo is relatively lifeless; its location within the South Pacific Gyre

__NOTOC__

The Southern Pacific Gyre is part of the Earth's system of rotating ocean currents, bounded by the Equator to the north, Australia to the west, the Antarctic Circumpolar Current to the south, and South America to the east. The center ...

blocks nutrients from reaching the area, and being so far from land it gets little nutrient run-off from coastal waters.

To the west the region of the South Pacific Ocean is also the site of the geographic center of the water hemisphere

The land hemisphere and water hemisphere are the hemispheres of Earth containing the largest possible total areas of land and ocean, respectively. By definition (assuming that the entire surface can be classed as either "land" or "ocean"), the t ...

, at near New Zealand

New Zealand ( mi, Aotearoa ) is an island country in the southwestern Pacific Ocean. It consists of two main landmasses—the North Island () and the South Island ()—and over 700 smaller islands. It is the sixth-largest island coun ...

's Bounty Islands

The Bounty Islands ( mi, Moutere Hauriri; "Island of angry wind") are a small group of 13 uninhabited granite islets and numerous rocks, with a combined area of , in the South Pacific Ocean. Territorially part of New Zealand, they lie about e ...

. The geographic center of the Pacific Ocean

The Pacific Ocean is the largest and deepest of Earth's five oceanic divisions. It extends from the Arctic Ocean in the north to the Southern Ocean (or, depending on definition, to Antarctica) in the south, and is bounded by the conti ...

lies further north-west where the Line Islands

The Line Islands, Teraina Islands or Equatorial Islands (in Gilbertese, ''Aono Raina'') are a chain of 11 atolls (with partly or fully enclosed lagoons) and coral islands (with a surrounding reef) in the central Pacific Ocean, south of the Haw ...

begin, west from Starbuck Island at .

Continental poles of inaccessibility

Eurasia

The Eurasian pole of inaccessibility (EPIA) is located in northwesternChina

China, officially the People's Republic of China (PRC), is a country in East Asia. It is the world's List of countries and dependencies by population, most populous country, with a Population of China, population exceeding 1.4 billion, slig ...

, near the Kazakhstan

Kazakhstan, officially the Republic of Kazakhstan, is a transcontinental country located mainly in Central Asia and partly in Eastern Europe. It borders Russia to the north and west, China to the east, Kyrgyzstan to the southeast, Uzbeki ...

border. It is also the furthest possible point on land from the ocean, given that Eurasia (or even merely Asia alone) is the largest continent on Earth.

Earlier calculations suggested that it is from the nearest coastline, located at , approximately north of the city of Ürümqi

Ürümqi ( ; also spelled Ürümchi or without umlauts), formerly known as Dihua (also spelled Tihwa), is the capital of the Xinjiang Uyghur Autonomous Region in the far northwest of the People's Republic of China. Ürümqi developed its ...

, in the Xinjiang Autonomous Region

Xinjiang, SASM/GNC: ''Xinjang''; zh, c=, p=Xīnjiāng; formerly romanized as Sinkiang (, ), officially the Xinjiang Uygur Autonomous Region (XUAR), is an autonomous region of the People's Republic of China (PRC), located in the northwest ...

of China

China, officially the People's Republic of China (PRC), is a country in East Asia. It is the world's List of countries and dependencies by population, most populous country, with a Population of China, population exceeding 1.4 billion, slig ...

, in the Gurbantünggüt Desert

The Gurbantünggüt Desert ( kk, Құрбантұңғыт шөлі; ug, قۇربانتۈڭغۈت قۇملۇقى, Qurbantüngghüt Qumluqi; zh, s=古尔班通古特沙漠 , t=古爾班通古特沙漠, p=Gǔ'ěrbāntōnggǔtè Shāmò) occupies a l ...

. The nearest settlements to this location are Hoxtolgay

Hoxtolgay or Heshituoluogai ( Oirat: 'twin peaks', Chinese: 和什托洛盖镇 ''Héshítuōluògài Zhèn'', Uyghur: Хоштолгай) is a town in Hoboksar Mongol Autonomous County, Xinjiang Uygur Autonomous Region, PR China. It is located at ...

Town

A town is a human settlement. Towns are generally larger than villages and smaller than cities, though the criteria to distinguish between them vary considerably in different parts of the world.

Origin and use

The word "town" shares an o ...

at , about to the northwest, Xazgat Township

A township is a kind of human settlement or administrative subdivision, with its meaning varying in different countries.

Although the term is occasionally associated with an urban area, that tends to be an exception to the rule. In Australia, ...

() at , about to the west, and Suluk at , about to the east.

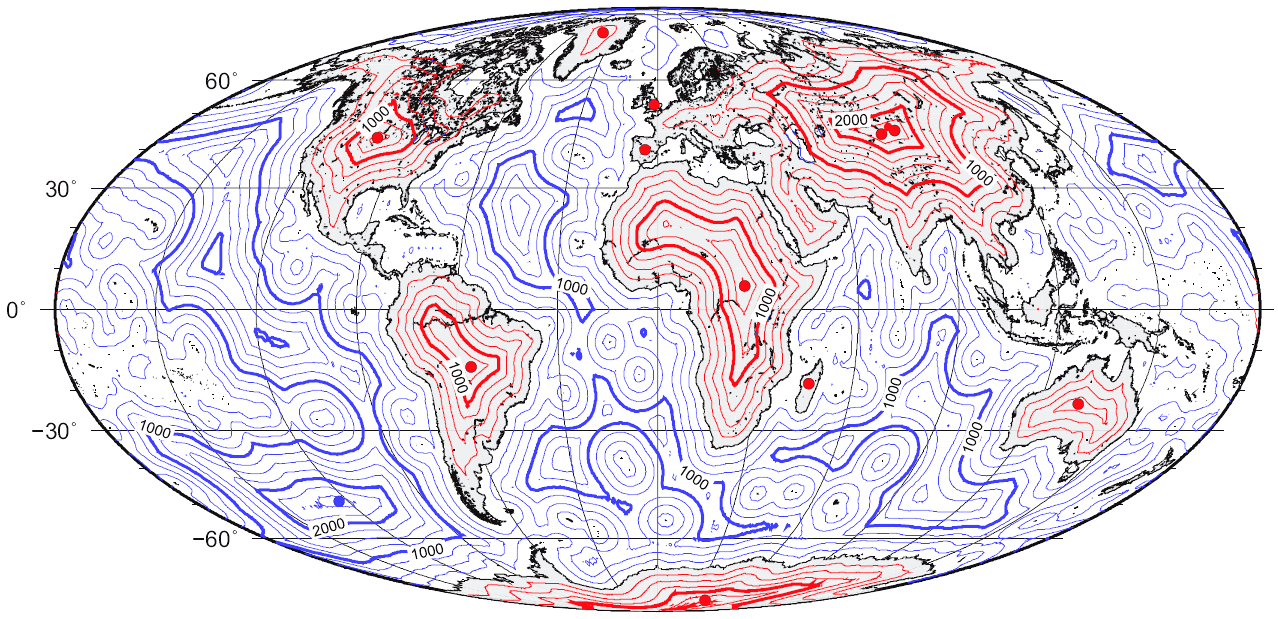

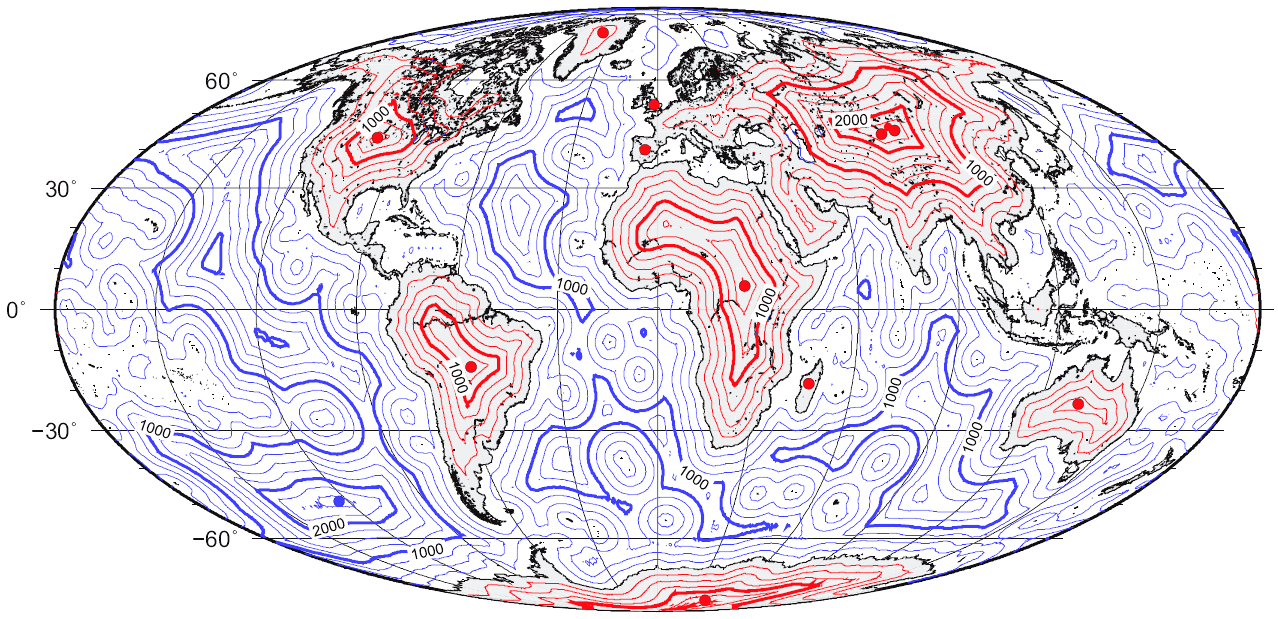

However, the previous pole location disregards the Gulf of Ob as part of the oceans, and a 2007 study proposes two other locations as the ones farther from any ocean (within the uncertainty of coastline definition): EPIA1 and EPIA2 , located respectively at 2,510±10 km (1560±6 mi) and 2,514±7 km (1,562±4 mi) from the oceans. These points lie in a close triangle about the Dzungarian Gate

The Dzungarian Gate (or Altai Gap or Altay Gap) is a geographically and historically significant mountain pass between China and Central Asia. It has been described as the "one and only gateway in the mountain-wall which stretches from Manchuria ...

, a significant historical gateway to migration between the East and West. EPIA2 is located near a settlement called ''K̂as K̂îr Su'' in a region named ''K̂îzîlk̂um'' (قىزىلقۇم) in the , Burultokay County.

Elsewhere in Xinjiang, the location in the southwestern suburbs of Ürümqi

Ürümqi ( ; also spelled Ürümchi or without umlauts), formerly known as Dihua (also spelled Tihwa), is the capital of the Xinjiang Uyghur Autonomous Region in the far northwest of the People's Republic of China. Ürümqi developed its ...

(Ürümqi County

Ürümqi County is a county of Xinjiang Uyghur Autonomous Region, Northwest China, it is under the administration of the prefecture-level city of Ürümqi, the capital of Xinjiang. It contains an area of 4,601 km² and according to the 20 ...

) was designated by local geography experts as the "center point of Asia" in 1992, and a monument to this effect was erected there in the 1990s. The site is a local tourist attraction.

Coincidentally, the continental and oceanic poles of inaccessibility have a similar radius; the Eurasian poles EPIA1 and EPIA2 are about closer to the ocean than the oceanic pole is to land.

Africa

InAfrica

Africa is the world's second-largest and second-most populous continent, after Asia in both cases. At about 30.3 million km2 (11.7 million square miles) including adjacent islands, it covers 6% of Earth's total surface area ...

, the pole of inaccessibility is at , from the coast, near the town of Obo in the Central African Republic

The Central African Republic (CAR; ; , RCA; , or , ) is a landlocked country in Central Africa. It is bordered by Chad to the north, Sudan to the northeast, South Sudan to the southeast, the DR Congo to the south, the Republic of th ...

and close to the country's tripoint

A tripoint, trijunction, triple point, or tri-border area is a geographical point at which the boundaries of three countries or subnational entities meet. There are 175 international tripoints as of 2020. Nearly half are situated in rivers, l ...

with South Sudan

South Sudan (; din, Paguot Thudän), officially the Republic of South Sudan ( din, Paankɔc Cuëny Thudän), is a landlocked country in East Africa. It is bordered by Ethiopia, Sudan, Central African Republic, Democratic Republic of th ...

and the Democratic Republic of the Congo

The Democratic Republic of the Congo (french: République démocratique du Congo (RDC), colloquially "La RDC" ), informally Congo-Kinshasa, DR Congo, the DRC, the DROC, or the Congo, and formerly and also colloquially Zaire, is a country in ...

.

North America

In

In North America

North America is a continent in the Northern Hemisphere and almost entirely within the Western Hemisphere. It is bordered to the north by the Arctic Ocean, to the east by the Atlantic Ocean, to the southeast by South America and th ...

, the continental pole of inaccessibility is on the Pine Ridge Reservation

The Pine Ridge Indian Reservation ( lkt, Wazí Aháŋhaŋ Oyáŋke), also called Pine Ridge Agency, is an Oglala Lakota Indian reservation located entirely within the U.S. state of South Dakota. Originally included within the territory of the Gr ...

in southwest South Dakota

South Dakota (; Sioux: , ) is a U.S. state in the North Central region of the United States. It is also part of the Great Plains. South Dakota is named after the Lakota and Dakota Sioux Native American tribes, who comprise a large po ...

about north of the town of Allen Allen, Allen's or Allens may refer to:

Buildings

* Allen Arena, an indoor arena at Lipscomb University in Nashville, Tennessee

* Allen Center, a skyscraper complex in downtown Houston, Texas

* Allen Fieldhouse, an indoor sports arena on the Univer ...

, from the nearest coastline at . The pole was marked in 2021 with a marker that represents the 7 Lakota Values and the four colors of the Lakota Medicine Wheel.

South America

InSouth America

South America is a continent entirely in the Western Hemisphere and mostly in the Southern Hemisphere, with a relatively small portion in the Northern Hemisphere at the northern tip of the continent. It can also be described as the sou ...

, the continental pole of inaccessibility is in Brazil at , near Arenápolis, Mato Grosso

Mato Grosso ( – lit. "Thick Bush") is one of the states of Brazil, the third largest by area, located in the Central-West region. The state has 1.66% of the Brazilian population and is responsible for 1.9% of the Brazilian GDP.

Neighboring ...

, from the nearest coastline. In 2017, the Turner Twins became the first adventurers to trek to the South American Pole of Inaccessibility.

Australia

In

In Australia

Australia, officially the Commonwealth of Australia, is a sovereign country comprising the mainland of the Australian continent, the island of Tasmania, and numerous smaller islands. With an area of , Australia is the largest country by ...

, the continental pole of inaccessibility is located either at or at , from the nearest coastline, approximately 161 km (100 miles) west-northwest of Alice Springs

Alice Springs ( aer, Mparntwe) is the third-largest town in the Northern Territory of Australia. Known as Stuart until 31 August 1933, the name Alice Springs was given by surveyor William Whitfield Mills after Alice, Lady Todd (''née'' A ...

. The nearest town is Papunya, Northern Territory

The Northern Territory (commonly abbreviated as NT; formally the Northern Territory of Australia) is an Australian territory in the central and central northern regions of Australia. The Northern Territory shares its borders with Western Aust ...

, about to the southwest of both locations.

Methods of calculation

As detailed below, several factors determine how a pole is calculated using computer modeling. Poles are calculated with respect to a particular coastline dataset. Commonly used datasets are the Global Self-consistent, Hierarchical, High-resolution Geography Database as well asOpenStreetMap

OpenStreetMap (OSM) is a free, open geographic database updated and maintained by a community of volunteers via open collaboration. Contributors collect data from surveys, trace from aerial imagery and also import from other freely licensed g ...

planet dumps.

Next, a distance function must be determined for calculating distances between coastlines and potential Poles. Some works tended to project data onto planes or perform spherical calculations; more recently, other works have used different algorithms and high-performance computing with ellipsoidal calculations.

Finally, an optimization algorithm must be developed. Several works use an adaptive grid method. In this method, a grid of, e.g., 21×21 points is created. Each point's distance from the coastline is determined and the point farthest from the coast identified. The grid is then recentered on this point and shrunk by some factor. This process iterates until the grid becomes very small. Some authors claim this adaptive grid method is problematic as it is not guaranteed to find the farthest point from a coastline. A more recent method, B9-Hillclimbing, uses random-restart hill climbing

numerical analysis, hill climbing is a mathematical optimization technique which belongs to the family of local search. It is an iterative algorithm that starts with an arbitrary solution to a problem, then attempts to find a better solutio ...

, simulated annealing

Simulated annealing (SA) is a probabilistic technique for approximating the global optimum of a given function. Specifically, it is a metaheuristic to approximate global optimization in a large search space for an optimization problem. ...

, and k-d tree

In computer science, a ''k''-d tree (short for ''k-dimensional tree'') is a space-partitioning data structure for organizing points in a ''k''-dimensional space. ''k''-d trees are a useful data structure for several applications, such as sea ...

s to find the farthest points from coastlines. This Hillclimbing method has not demonstrated, however, how it is consistent with the foundational idea that a pole of inaccessibility must, by definition, have only three closest shoreline points.

To date there has been no meta-study of the various works, and the algorithms and datasets they use, that compares their calculations of poles of inaccessibility to satellite determined calculations. Therefore no conclusion is possible at this time as to which methodology is more accurate in calculating a pole of inaccessibility.

List of poles of inaccessibility

Poles of Inaccessibility, as determined by some authors, are listed in the table below. This list is incomplete and may not capture all works done to date.See also

*Antipodes

In geography, the antipode () of any spot on Earth is the point on Earth's surface diametrically opposite to it. A pair of points ''antipodal'' () to each other are situated such that a straight line connecting the two would pass through ...

* Pole of inaccessibility (Antarctic research station)

* Geographical pole

A geographical pole or geographic pole is either of the two points on Earth where its axis of rotation intersects its surface. The North Pole lies in the Arctic Ocean while the South Pole is in Antarctica. North and South poles are also define ...

* Extreme points of Earth

This article lists extreme locations on Earth that hold geographical records or are otherwise known for their geophysical or meteorological superlatives. All of these locations are Earth-wide extremes; extremes of individual continents or coun ...

* Land and water hemispheres

The land hemisphere and water hemisphere are the hemispheres of Earth containing the largest possible total areas of land and ocean, respectively. By definition (assuming that the entire surface can be classed as either "land" or "ocean"), the t ...

* Geographical centre

In geography, the centroid of the two-dimensional shape of a region of the Earth's surface (projected radially to sea level or onto a geoid surface) is known as its geographic centre or geographical centre or (less commonly) gravitational centre. I ...

* List of cities that are inaccessible by road

References

External links

How to calculate PIAs

Team N2i successfully conquer the Pole of Inaccessibility by foot and kite on 19th Jan '07

{{DEFAULTSORT:Pole Of Inaccessibility Lists of coordinates Polar regions of the Earth Geography of the Arctic Geography of Antarctica Extreme points of Earth