Continental Navy on:

[Wikipedia]

[Google]

[Amazon]

The Continental Navy was the

The original intent was to intercept the supply of arms and provisions to British soldiers, who had placed

The original intent was to intercept the supply of arms and provisions to British soldiers, who had placed

On June 12, 1775, the

On June 12, 1775, the

When it came to selecting commanders for ships, Congress tended to be split evenly between merit and patronage. Among those who were selected for political reasons were Esek Hopkins,

When it came to selecting commanders for ships, Congress tended to be split evenly between merit and patronage. Among those who were selected for political reasons were Esek Hopkins,

By December 13, 1775, Congress had authorized the construction of 13 new

By December 13, 1775, Congress had authorized the construction of 13 new

Before the Franco-American Alliance, the royalist French government attempted to maintain a state of respectful neutrality during the Revolutionary War. That being said, the nation maintained neutrality at face value, often openly harboring Continental vessels and supplying their needs.

With the presence of American diplomats

Before the Franco-American Alliance, the royalist French government attempted to maintain a state of respectful neutrality during the Revolutionary War. That being said, the nation maintained neutrality at face value, often openly harboring Continental vessels and supplying their needs.

With the presence of American diplomats

Of the approximately 65 vessels (new, converted, chartered, loaned, and captured) that served at one time or another with the Continental Navy, only 11 survived the war. The

Of the approximately 65 vessels (new, converted, chartered, loaned, and captured) that served at one time or another with the Continental Navy, only 11 survived the war. The

navy

A navy, naval force, or maritime force is the branch of a nation's armed forces principally designated for naval and amphibious warfare; namely, lake-borne, riverine, littoral, or ocean-borne combat operations and related functions. It in ...

of the United States during the American Revolutionary War

The American Revolutionary War (April 19, 1775 – September 3, 1783), also known as the Revolutionary War or American War of Independence, was a major war of the American Revolution. Widely considered as the war that secured the independence of t ...

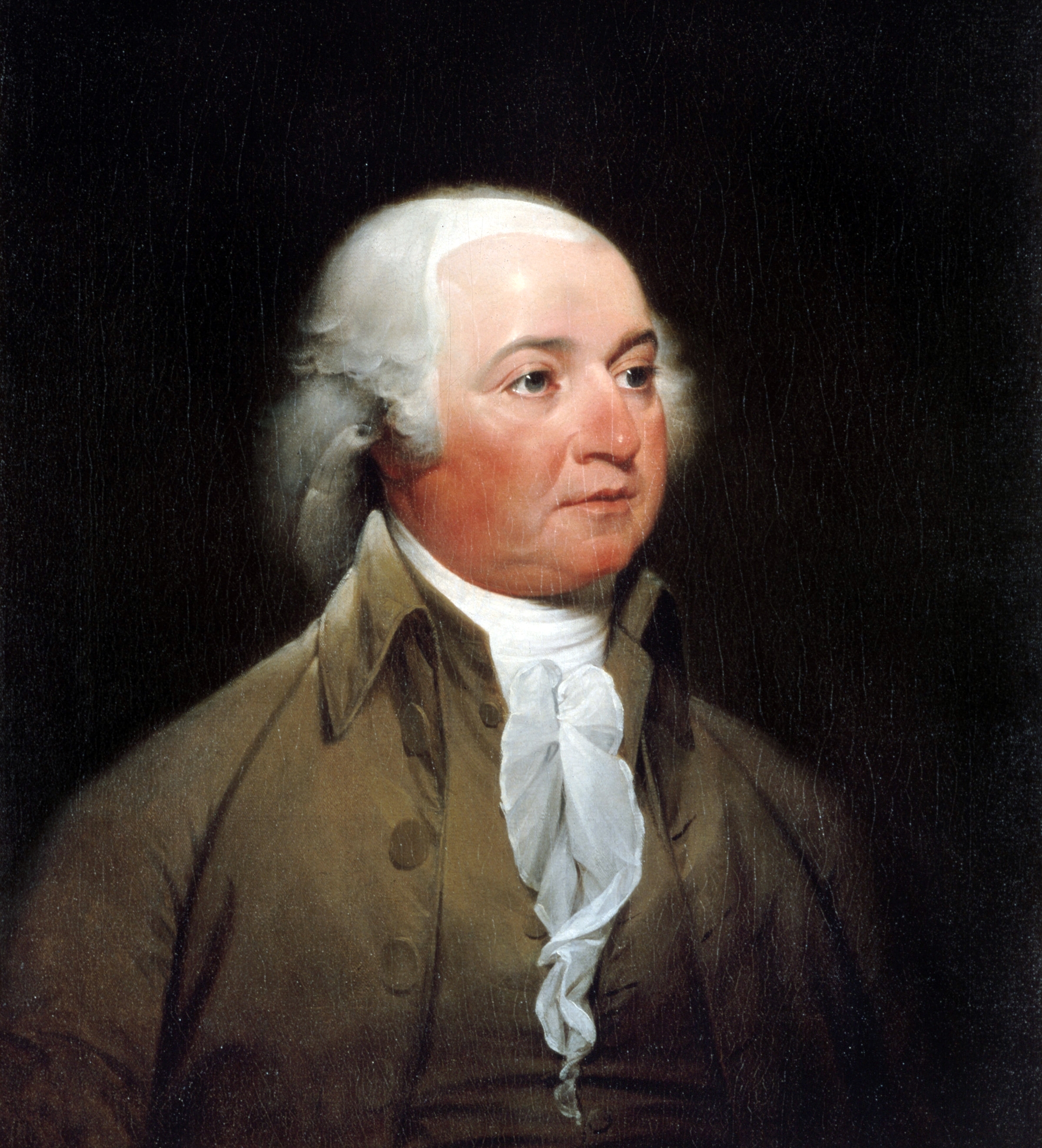

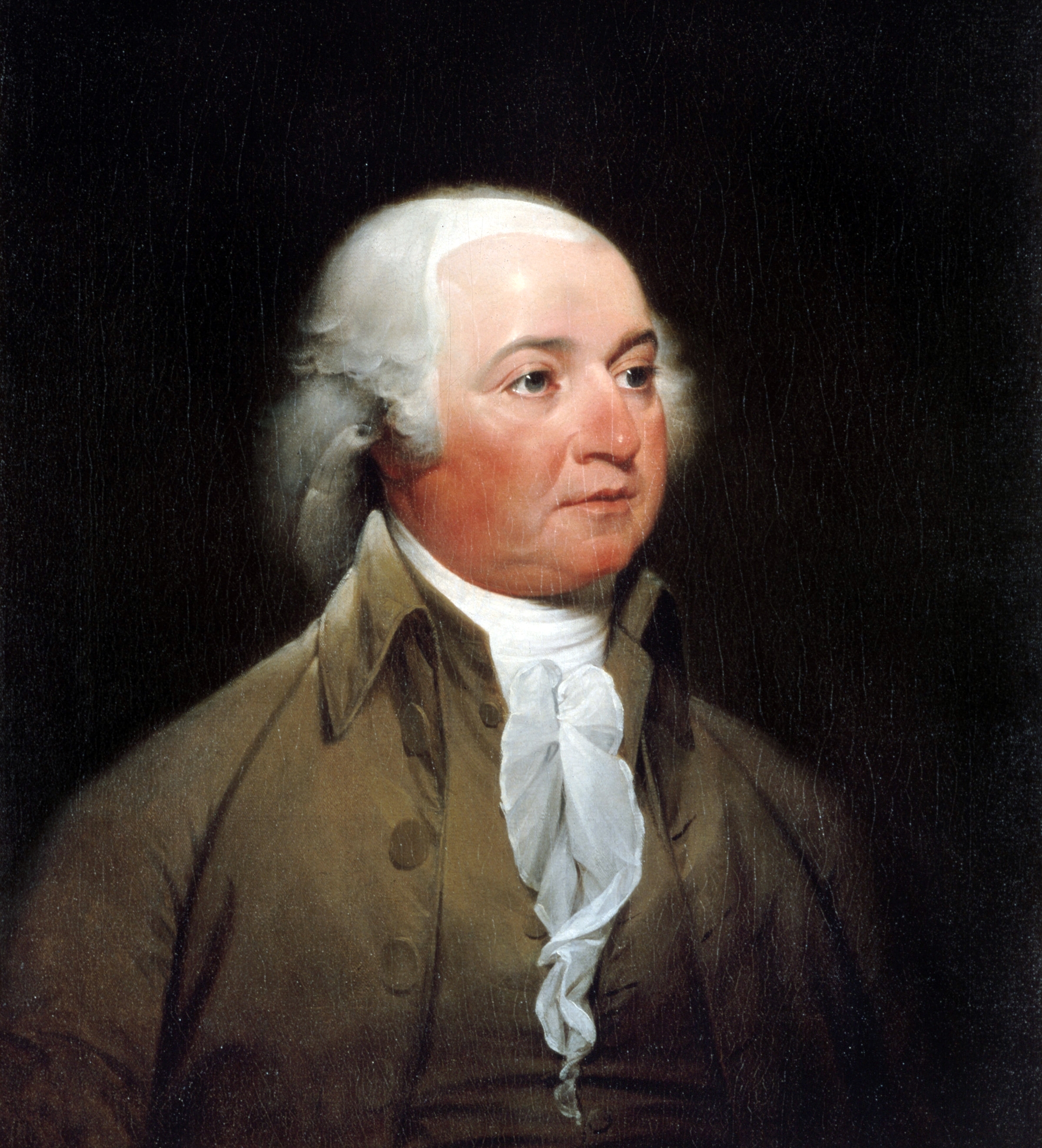

and was founded October 13, 1775. The fleet cumulatively became relatively substantial through the efforts of the Continental Navy's patron John Adams

John Adams (October 30, 1735 – July 4, 1826) was an American statesman, attorney, diplomat, writer, and Founding Father who served as the second president of the United States from 1797 to 1801. Before his presidency, he was a leader of t ...

and vigorous Congressional support in the face of stiff opposition, when considering the limitations imposed upon the Patriot supply pool.

The main goal of the navy was to intercept shipments of British matériel and generally disrupt British maritime commercial operations. The initial fleet consisted of converted merchantmen

A merchant ship, merchant vessel, trading vessel, or merchantman is a watercraft that transports cargo or carries passengers for hire. This is in contrast to pleasure craft, which are used for personal recreation, and naval ships, which are us ...

because of the lack of funding, manpower, and resources, with exclusively designed warships being built later in the conflict. The vessels that successfully made it to sea met with success only rarely, and the effort contributed little to the overall outcome of the war.

The fleet did serve to highlight a few examples of Continental resolve, notably launching Captain John Barry into the limelight. It provided needed experience for a generation of officers who went on to command conflicts which involved the early American navy.

After the war, the Continental Navy was dissolved. With the federal government in need of all available capital, the few remaining ships were sold, the final vessel being auctioned off in 1785 to a private bidder.

The Continental Navy is the first establishment of what is now the United States Navy

The United States Navy (USN) is the maritime service branch of the United States Armed Forces and one of the eight uniformed services of the United States. It is the largest and most powerful navy in the world, with the estimated tonnage ...

.

Congressional oversight of construction

The original intent was to intercept the supply of arms and provisions to British soldiers, who had placed

The original intent was to intercept the supply of arms and provisions to British soldiers, who had placed Boston

Boston (), officially the City of Boston, is the state capital and most populous city of the Commonwealth of Massachusetts, as well as the cultural and financial center of the New England region of the United States. It is the 24th- mo ...

under martial law

Martial law is the imposition of direct military control of normal civil functions or suspension of civil law by a government, especially in response to an emergency where civil forces are overwhelmed, or in an occupied territory.

Use

Marti ...

. George Washington

George Washington (February 22, 1732, 1799) was an American military officer, statesman, and Founding Father who served as the first president of the United States from 1789 to 1797. Appointed by the Continental Congress as commander of ...

had already informed Congress that he had assumed command of several ships for this purpose, and individual governments of various colonies had outfitted their own warships. The first formal movement for a navy came from Rhode Island

Rhode Island (, like ''road'') is a state in the New England region of the Northeastern United States. It is the smallest U.S. state by area and the seventh-least populous, with slightly fewer than 1.1 million residents as of 2020, but it ...

, whose State Assembly passed a resolution on August 26, 1775, instructing its delegates to Congress to introduce legislation calling ''"for building at the Continental expense a fleet of sufficient force, for the protection of these colonies, and for employing them in such a manner and places as will most effectively annoy our enemies...."'' The measure in the Continental Congress was met with much derision, especially on the part of Maryland

Maryland ( ) is a state in the Mid-Atlantic region of the United States. It shares borders with Virginia, West Virginia, and the District of Columbia to its south and west; Pennsylvania to its north; and Delaware and the Atlantic Ocean to ...

delegate Samuel Chase

Samuel Chase (April 17, 1741 – June 19, 1811) was a Founding Father of the United States, a signatory to the Continental Association and United States Declaration of Independence as a representative of Maryland, and an Associate Justice of t ...

who exclaimed it to be "the maddest idea in the world." John Adams later recalled, "The opposition... was very loud and vehement. It was... represented as the most wild, visionary, mad project that had ever been imagined. It was an infant taking a mad bull by his horns."

During this time, however, the issue arose of Quebec

Quebec ( ; )According to the Canadian government, ''Québec'' (with the acute accent) is the official name in Canadian French and ''Quebec'' (without the accent) is the province's official name in Canadian English is one of the thirtee ...

-bound British supply ships carrying desperately needed provisions that could otherwise benefit the Continental Army. The Continental Congress appointed Silas Deane

Silas Deane (September 23, 1789) was an American merchant, politician, and diplomat, and a supporter of American independence. Deane served as a delegate to the Continental Congress, where he signed the Continental Association, and then became the ...

and John Langdon to draft a plan to seize ships from the convoy in question.

Creation

On June 12, 1775, the

On June 12, 1775, the Rhode Island General Assembly

The State of Rhode Island General Assembly is the state legislature of the U.S. state of Rhode Island. A bicameral body, it is composed of the lower Rhode Island House of Representatives with 75 representatives, and the upper Rhode Island Se ...

, meeting at East Greenwich, passed a resolution creating a navy for the colony of Rhode Island. The same day, Governor Nicholas Cooke

Nicholas Cooke (February 3, 1717September 14, 1782) was a governor of the Colony of Rhode Island and Providence Plantations during the American Revolutionary War, and after Rhode Island became a state, he continued in this position to become the ...

signed orders addressed to Captain Abraham Whipple

Abraham, ; ar, , , name=, group= (originally Abram) is the common Hebrew patriarch of the Abrahamic religions, including Judaism, Christianity, and Islam. In Judaism, he is the founding father of the special relationship between the Jews ...

, commander of the sloop ''Katy'' and commodore of the armed vessels employed by the government.

The first formal movement for the creation of a Continental navy came from Rhode Island because its merchants' widespread shipping activities had been severely harassed by British frigates. On August 26, 1775, Rhode Island General Assembly

The State of Rhode Island General Assembly is the state legislature of the U.S. state of Rhode Island. A bicameral body, it is composed of the lower Rhode Island House of Representatives with 75 representatives, and the upper Rhode Island Se ...

passed a resolution that there be a single Continental fleet funded by the Continental Congress. The resolution was introduced in the Continental Congress on October 3, 1775, but was tabled. In the meantime, George Washington

George Washington (February 22, 1732, 1799) was an American military officer, statesman, and Founding Father who served as the first president of the United States from 1789 to 1797. Appointed by the Continental Congress as commander of ...

had begun to acquire ships, starting with the schooner which was chartered by Washington from merchant and Continental Army Lt. Colonel John Glover of Marblehead, Massachusetts. ''Hannah'' was commissioned and launched on September 5, 1775, under the command of Captain Nicholson Broughton from the port of Beverly, Massachusetts.

The United States Navy decided in 1971 to recognize October 13, 1775 as the date of its official establishment, the passage of the resolution of the Continental Congress at Philadelphia that created the Continental Navy. On this day, Congress authorized the purchase of two vessels to be armed for a cruise against British merchant ships; these ships became and . The first ship in commission was which was purchased on November 4 and commissioned on December 3 by Captain Dudley Saltonstall

Dudley Saltonstall (1738–1796) was an American naval commander during the American Revolutionary War. He is best known as the commander of the naval forces of the 1779 Penobscot Expedition, which ended in complete disaster, with all ships lost. ...

. On November 10, 1775, the Continental Congress passed a resolution calling for two battalions of Marines

Marines, or naval infantry, are typically a military force trained to operate in littoral zones in support of naval operations. Historically, tasks undertaken by marines have included helping maintain discipline and order aboard the ship (refle ...

to be raised for service with the fleet. John Adams

John Adams (October 30, 1735 – July 4, 1826) was an American statesman, attorney, diplomat, writer, and Founding Father who served as the second president of the United States from 1797 to 1801. Before his presidency, he was a leader of t ...

drafted its first governing regulations, which were adopted by Congress on November 28, 1775, and remained in effect throughout the Revolutionary War. The Rhode Island resolution was reconsidered by the Continental Congress and was passed on December 13, 1775, authorizing the building of thirteen frigates within the next three months: five ships of 32 guns, five with 28 guns, and three with 24 guns.

When it came to selecting commanders for ships, Congress tended to be split evenly between merit and patronage. Among those who were selected for political reasons were Esek Hopkins,

When it came to selecting commanders for ships, Congress tended to be split evenly between merit and patronage. Among those who were selected for political reasons were Esek Hopkins, Dudley Saltonstall

Dudley Saltonstall (1738–1796) was an American naval commander during the American Revolutionary War. He is best known as the commander of the naval forces of the 1779 Penobscot Expedition, which ended in complete disaster, with all ships lost. ...

, and Esek Hopkins' son John Burroughs Hopkins. However, Abraham Whipple

Abraham, ; ar, , , name=, group= (originally Abram) is the common Hebrew patriarch of the Abrahamic religions, including Judaism, Christianity, and Islam. In Judaism, he is the founding father of the special relationship between the Jews ...

, Nicholas Biddle

Nicholas Biddle (January 8, 1786February 27, 1844) was an American financier who served as the third and last president of the Second Bank of the United States (chartered 1816–1836). Throughout his life Biddle worked as an editor, diplomat, au ...

, and John Paul Jones

John Paul Jones (born John Paul; July 6, 1747 July 18, 1792) was a Scottish-American naval captain who was the United States' first well-known naval commander in the American Revolutionary War. He made many friends among U.S political elites ( ...

managed to be appointed with backgrounds in marine warfare.

On December 22, 1775, Esek Hopkins was appointed the naval commander-in-chief, and officers of the navy were commissioned. Saltonstall, Biddle, Hopkins, and Whipple were commissioned as captains of the ''Alfred'', ''Andrew Doria'', ''Cabot'', and , respectively.

Hopkins led the first major naval action of the Continental Navy in early March 1776 with this small fleet, complemented by (12), (8), and (10). The battle occurred at Nassau, Bahamas where stores of much-needed gunpowder were seized for the use of the Continental Army. However, success was diluted with the appearance of disease spreading from ship to ship.

On April 6, 1776, the squadron, with the addition of (8), unsuccessfully encountered the 20-gun in the first major sea battle of the Continental Navy. Hopkins failed to give any substantive orders other than to recall the fleet from the engagement, a move which Captain Nicholas Biddle described: "away we all went helter, skelter, one flying here, another there."

On Lake Champlain, Benedict Arnold ordered the construction of 12 war vessels to slow down the British fleet that was invading New York from Canada. The British fleet destroyed Arnold's fleet, but the US fleet managed to slow down the British after a two-day battle, known as the Battle of Valcour Island

The Battle of Valcour Island, also known as the Battle of Valcour Bay, was a naval engagement that took place on October 11, 1776, on Lake Champlain. The main action took place in Valcour Bay, a narrow strait between the New York mainland and ...

, and managed to slow the progression of the British Army.

As the war progressed, states began directing more resources toward naval pursuits. During the inaugural session of the Virginia General Assembly

The Virginia General Assembly is the legislative body of the Commonwealth of Virginia, the oldest continuous law-making body in the Western Hemisphere, the first elected legislative assembly in the New World, and was established on July 30, 16 ...

, the senate began acquiring lands for naval manufacturing. Charles O. Paullin Charles Oscar Paullin (20 July 1869 – 1 September 1944) was an important naval historian, who made a significant early contribution to the administrative history of the United States Navy.

Early life and education

Raised in Greene County, Ohio, P ...

states that "no other state owned as much land, properties, and manufactories devoted to naval purposes as Virginia. Sampson Mathews

Sampson Mathews (c. 1737 – January 20, 1807) was an American merchant, soldier, and legislator in the colony (and later U.S. state) of Virginia.

A son of John and Ann (Archer) Mathews, Mathews was an early merchant in the Shenandoah Val ...

oversaw the operation stationed at Warwick

Warwick ( ) is a market town, civil parish and the county town of Warwickshire in the Warwick District in England, adjacent to the River Avon. It is south of Coventry, and south-east of Birmingham. It is adjoined with Leamington Spa and Whi ...

on the James River, the most important of the works, which produced much sail material from flax grown in his home county of Augusta, as there was no money available to buy linen cloth for sails.

The thirteen frigates

By December 13, 1775, Congress had authorized the construction of 13 new

By December 13, 1775, Congress had authorized the construction of 13 new frigate

A frigate () is a type of warship. In different eras, the roles and capabilities of ships classified as frigates have varied somewhat.

The name frigate in the 17th to early 18th centuries was given to any full-rigged ship built for speed and ...

s, rather than refitting merchantmen to increase the fleet. Five ships (, , , , and ) were to be rated 32 guns, five (, , , , and ) 28 guns, and three (, , and ) 24 guns. Only eight frigates made it to sea and their effectiveness was limited; they were completely outmatched by the mighty Royal Navy, and nearly all were captured or sunk by 1781.

''Washington'', ''Effingham'', ''Congress'', and ''Montgomery'' were scuttled or burned in October and November 1777 before going to sea to prevent their capture by the British. , commanded by Captain James Nicholson, made a number of unsuccessful attempts to break through the blockade of Chesapeake Bay

The Chesapeake Bay ( ) is the largest estuary in the United States. The Bay is located in the Mid-Atlantic (United States), Mid-Atlantic region and is primarily separated from the Atlantic Ocean by the Delmarva Peninsula (including the parts: the ...

. On March 31, 1778, in another attempt, she ran aground near Hampton Roads

Hampton Roads is the name of both a body of water in the United States that serves as a wide channel for the James River, James, Nansemond River, Nansemond and Elizabeth River (Virginia), Elizabeth rivers between Old Point Comfort and Sewell's ...

, where her captain went ashore. Shortly after, and appeared on the scene to accept her surrender.

Guarding American commerce and raiding British commerce and supply were the principal duties of the Continental Navy. Privateer

A privateer is a private person or ship that engages in maritime warfare under a commission of war. Since robbery under arms was a common aspect of seaborne trade, until the early 19th century all merchant ships carried arms. A sovereign or deleg ...

s had some success, with 1,697 letters of marque being issued by Congress. Individual states, American agents in Europe and in the Caribbean also issued commissions; taking duplications into account more than 2,000 commissions were issued by the various authorities. Lloyd's of London estimated that 2,208 British ships were taken by Yankee privateers, amounting to almost $66 million, a significant sum at the time.

Most of the eight frigates that went to sea took multiple prizes and had semi-successful cruises before their captures, however, there were exceptions. On September 27, 1777, participated in a delaying action on the Delaware River

The Delaware River is a major river in the Mid-Atlantic (United States), Mid-Atlantic region of the United States. From the meeting of its branches in Hancock (village), New York, Hancock, New York, the river flows for along the borders of N ...

against the British army pursuing George Washington

George Washington (February 22, 1732, 1799) was an American military officer, statesman, and Founding Father who served as the first president of the United States from 1789 to 1797. Appointed by the Continental Congress as commander of ...

's forces. The ebb tide arrived and left the ''Delaware'' stranded, leading to her capture. was blockaded in Providence, Rhode Island

Providence is the capital and most populous city of the U.S. state of Rhode Island. One of the oldest cities in New England, it was founded in 1636 by Roger Williams, a Reformed Baptist theologian and religious exile from the Massachusetts Bay ...

, shortly after her completion, and did not break out of the blockade until March 8, 1778. After a successful cruise under Captain John Burroughs Hopkins, she was assigned to the ill-fated Penobscot Expedition

The Penobscot Expedition was a 44-ship American naval armada during the Revolutionary War assembled by the Provincial Congress of the Province of Massachusetts Bay. The flotilla of 19 warships and 25 support vessels sailed from Boston on July 1 ...

under Captain Dudley Saltonstall

Dudley Saltonstall (1738–1796) was an American naval commander during the American Revolutionary War. He is best known as the commander of the naval forces of the 1779 Penobscot Expedition, which ended in complete disaster, with all ships lost. ...

, where she was trapped by the British and burned on August 15, 1779, to prevent her capture. , captained by John Manley

John Paul Manley (born January 5, 1950) is a Canadian lawyer, businessman, and politician who served as the eighth deputy prime minister of Canada from 2002 to 2003. He served as Liberal Member of Parliament for Ottawa South from 1988 to ...

, managed to capture two merchantmen as well as the Royal Navy vessel . Later on July 8, 1777, however, the ''Hancock'' was captured by HMS ''Rainbow'' of a pursuing squadron, and became the British man of war ''Iris''.

took five prizes in her early cruises. On March 7, 1778, she was escorting a convoy of merchantmen when the British 64-gun ship bore down on the convoy. ''Randolph'', under the command of Captain Nicholas Biddle

Nicholas Biddle (January 8, 1786February 27, 1844) was an American financier who served as the third and last president of the Second Bank of the United States (chartered 1816–1836). Throughout his life Biddle worked as an editor, diplomat, au ...

came to the defense of the merchantmen and engaged the heavily superior foe. In the ensuing engagement, the two ships were both severely manhandled but in the course of the action, the magazine of the ''Randolph'' exploded causing the destruction of the entire vessel and all but four of her crew. The falling debris from the explosion severely damaged the ''Yarmouth'' enough that she could no longer pursue the American ships.

, under the command of Captain John Barry, captured three prizes before being run aground in action on September 27, 1778. Her crew scuttled her, but she was raised by the British who refloated her for further use in the name of the Crown.

, under the command of Captains Hector McNeill and Samuel Tucker, had captured 17 prizes in earlier cruises and had carried John Adams to France in February and March 1778. She was captured (along with the frigate which had taken 14 prizes in her own service under Captain Abraham Whipple

Abraham, ; ar, , , name=, group= (originally Abram) is the common Hebrew patriarch of the Abrahamic religions, including Judaism, Christianity, and Islam. In Judaism, he is the founding father of the special relationship between the Jews ...

) in the fall of Charleston, South Carolina

Charleston is the largest city in the U.S. state of South Carolina, the county seat of Charleston County, and the principal city in the Charleston–North Charleston metropolitan area. The city lies just south of the geographical midpoint o ...

on May 12, 1780.

The final frigate to meet her end of Continental service was . ''Trumbull'', which had not gone to sea until September 1779 under James Nicholson, had gained acclaim in bloody action against the Letter of Marque ''Watt''. On August 28, 1781, she met HMS ''Iris'' and ''General Monk'' and engaged. In the action, ''Trumbull'' was forced to surrender to the former American naval vessels (the ''General Monk'' was the captured Rhode Island privateer ''General Washington'', itself recaptured in April 1782 and placed in service with the Continental Navy).

French naval collaboration

Before the Franco-American Alliance, the royalist French government attempted to maintain a state of respectful neutrality during the Revolutionary War. That being said, the nation maintained neutrality at face value, often openly harboring Continental vessels and supplying their needs.

With the presence of American diplomats

Before the Franco-American Alliance, the royalist French government attempted to maintain a state of respectful neutrality during the Revolutionary War. That being said, the nation maintained neutrality at face value, often openly harboring Continental vessels and supplying their needs.

With the presence of American diplomats Benjamin Franklin

Benjamin Franklin ( April 17, 1790) was an American polymath who was active as a writer, scientist, inventor, statesman, diplomat, printer, publisher, and political philosopher. Encyclopædia Britannica, Wood, 2021 Among the leading inte ...

and Silas Deane, the Continental Navy gained a permanent link to French affairs. Through Franklin and like-minded agents, Continental officers were afforded the ability to receive commissions and to survey and purchase prospective ships for military use.

Early in the conflict, Captains Lambert Wickes

Lambert Wickes (1735 – October 1, 1777) was a captain in the Continental Navy during the American Revolutionary War.

Revolutionary activities

Wickes was born sometime in 1735 in Kent County, Province of Maryland. His home was on Eastern ...

and Gustavus Conyngham

Gustavus Conyngham (about 1747 – 27 November 1819) was an Irish-born American merchant sea captain, an officer in the Continental Navy and a privateer. As a commissioned captain fighting the British in the American Revolutionary War, he captur ...

operated out of various French ports for the purpose of commerce raiding. The French did attempt to enforce their neutrality by seizing and of the Continental Navy. However, with the commencement of the official alliance in 1778, ports were officially open to Continental ships.

The most prominent Continental officer to operate out of France was Captain John Paul Jones. Jones had been preying upon British commerce aboard but only now saw the opportunity for higher command. The French loaned Jones the merchantman ''Duc de Duras'', which Jones refitted and renamed as a more powerful replacement for the ''Ranger''. In August 1779, Jones was given command of a squadron of vessels of both American and French ownership. The goal was not only to harass British commerce but also to prospectively land 1,500 French regulars in the lightly guarded western regions of Britain. Unfortunately for the ambitious Jones, the French pulled out of the agreement pertaining to an invasion force, but the French did manage to uphold the plan regarding his command of the naval squadron. Sailing in a clockwise fashion around Ireland and down the east coast of Britain, the squadron captured a number of merchantmen. French commander Landais decided early on in the expedition to retain control of the French ships, thereby often leaving and rejoining the effort when he felt that it was fortuitous.

On September 23, 1779, Jones' squadron was off Flamborough Head when the British man-of-war and HM hired armed ship bore down on the Franco-American force. The lone Continental frigate ''Bonhomme Richard'' engaged ''Serapis''. The rigging of the two ships became entangled during the combat, and several guns of Jones' ship had been taken out of action. The captain of ''Serapis'' asked Jones if he had struck his colors, to which Jones has been quoted as replying, "I have not yet begun to fight!" Upon raking the ''Serapis'', the crew of the ''Bonhomme Richard'' led by Jones boarded the British ship and captured her. Likewise, the French frigate ''Pallas'' captured ''Countess of Scarborough''. Two days later, ''Bonhomme Richard'' sank from the overwhelming amount of damage that she had sustained. The action was an embarrassing defeat for the Royal Navy.

The French also loaned the Continental Navy the use of the corvette . The one ship of the line

A ship of the line was a type of naval warship constructed during the Age of Sail from the 17th century to the mid-19th century. The ship of the line was designed for the naval tactic known as the line of battle, which depended on the two colu ...

built for service in the Continental Navy was the 74-gun , but it was offered as a gift to France on September 3, 1782, in compensation for the loss of ''Le Magnifique

''Le Magnifique'' (literally ''The Magnificent''; also known as The Man from Acapulco) is a French/Italian international co-production released in 1973, starring Jean-Paul Belmondo, Jacqueline Bisset and Vittorio Caprioli that was directed by P ...

'' in service to the American Revolution.

France officially entered the war on June 17, 1778. Still, the ships that the French sent to the Western Hemisphere spent most of the year in the West Indies and only sailed near the Thirteen Colonies during the Caribbean hurricane season from July until November. The first French fleet attempted landings in New York and Rhode Island, but ultimately failed to engage British forces during 1778. In 1779, a fleet commanded by Vice Admiral Charles Henri, comte d'Estaing assisted American forces attempting to recapture Savannah, Georgia.

In 1780, a fleet with 6,000 troops commanded by Lieutenant General Jean-Baptiste, comte de Rochambeau landed at Newport, Rhode Island; shortly afterward, the British blockaded the fleet. In early 1781, Washington and de Rochambeau planned an attack against the British in the Chesapeake Bay area to coordinate with the arrival of a large fleet under Vice Admiral François, comte de Grasse. Washington and de Rochambeau marched to Virginia after successfully deceiving the British that an attack was planned in New York, and de Grasse began landing forces near Yorktown, Virginia. On September 5, 1781, de Grasse and the British met in the Battle of the Virginia Capes

The Battle of the Chesapeake, also known as the Battle of the Virginia Capes or simply the Battle of the Capes, was a crucial naval battle in the American Revolutionary War that took place near the mouth of the Chesapeake Bay on 5 September 17 ...

, which ended with the French fleet in control of Chesapeake Bay. Protected from the sea by the French fleet, American and French forces surrounded, besieged, and forced the surrender of the British forces under Lord Corwallis, effectively winning the war and leading to peace two years later.

End of the Continental Navy

Of the approximately 65 vessels (new, converted, chartered, loaned, and captured) that served at one time or another with the Continental Navy, only 11 survived the war. The

Of the approximately 65 vessels (new, converted, chartered, loaned, and captured) that served at one time or another with the Continental Navy, only 11 survived the war. The Treaty of Paris Treaty of Paris may refer to one of many treaties signed in Paris, France:

Treaties

1200s and 1300s

* Treaty of Paris (1229), which ended the Albigensian Crusade

* Treaty of Paris (1259), between Henry III of England and Louis IX of France

* Trea ...

in 1783 ended the Revolutionary War and, by 1785, Congress had disbanded the Continental Navy and sold the remaining ships.

The frigate fired the final shots of the American Revolutionary War; it was also the last ship in the Navy. A faction within Congress wanted to keep her, but the new nation did not have the funds to keep her in service, and she was auctioned off for $26,000. Factors leading to the dissolution of the Navy included a general lack of money, the loose confederation of the states, a change of goals from war to peace, and more domestic and fewer foreign interests.

See also

*Naval battles of the American Revolutionary War

The American Revolutionary War saw a series of battles involving naval forces of the Royal Navy, British Royal Navy and the Continental Navy from 1775, and of the French Navy from 1778 onwards. Although the British enjoyed more numerical vict ...

* Quasi War

The Quasi-War (french: Quasi-guerre) was an undeclared naval war fought from 1798 to 1800 between the United States and the French First Republic, primarily in the Caribbean and off the East Coast of the United States. The ability of Congress ...

* United States Navy

The United States Navy (USN) is the maritime service branch of the United States Armed Forces and one of the eight uniformed services of the United States. It is the largest and most powerful navy in the world, with the estimated tonnage ...

* Bibliography of early American naval history

Historical accounts for early U.S. naval history now occur across the spectrum of two and more centuries. This Bibliography lends itself primarily to reliable sources covering early U.S. naval history beginning around the American Revolution per ...

* List of American Revolutionary War battles

This is a list of military actions in the American Revolutionary War. Actions marked with an asterisk involved no casualties.

Major campaigns, theaters, and expeditions of the war

* Boston campaign (1775–1776)

* Invasion of Quebec (1775†...

* List of George Washington articles

The following is a list of articles about (and largely involving) George Washington.

Ancestry and childhood

* Augustine Washington and Mary Ball Washington – father and mother of George Washington

* Lawrence Washington (1718–1752) – ...

References

Bibliography

* * William M. Fowler, ''Rebels Under Sail'' (New York: Charles Scribner's Sons, 1976) * * * Perrenot, Preston B. (2010). ''United States Navy Grade Insignia 1776-1852.'' CreateSpace Independent Publishing Platform. * * ;Further reading * {{Authority control Disbanded navies Military history of the United States Military units and formations established in 1775 Military units and formations disestablished in 1785