Constitutional Council (France) on:

[Wikipedia]

[Google]

[Amazon]

The Constitutional Council (french: Conseil constitutionnel; ) is the highest constitutional authority in

pp. 304–320

see p. 307 "The number of references has steadily grown; it is no exaggeration to claim that any important controversial legislation is now likely to be referred." Another task, of lesser importance in terms of number of referrals, is the reclassification of statute law into the domain of regulations on the Prime Minister's request. This happens when the Prime Minister and his government wish to alter law that has been enacted as statute law, but should instead belong to regulations according to the Constitution. The Prime Minister has to obtain reclassification from the Council prior to taking any

official translation

of the Constitution on the site of the

Constitutional Council overview

on the Council web site.'' The

The

pp. 189–259

/ref>Michael H. Davis, ''The Law/Politics Distinction, the French Conseil Constitutionnel, and the

pp. 45–92

/ref>Denis Tallon, John N. Hazard, George A. Bermann, ''The Constitution and the Courts in France'', The American Journal of Comparative Law, Vol. 27, No. 4 (Autumn, 1979)

pp. 567–587

/ref> Whether the Constitutional Council is a court is a subject of academic discussion, but some scholars consider it effectively the

While since the 19th century the judicial review that the Constitutional Council brings to bear on the acts of the

While since the 19th century the judicial review that the Constitutional Council brings to bear on the acts of the

Decision 71-44DC

some provisions of a law changing the rules for the incorporation of private nonprofit associations, because they infringed on freedom of association, one of the principles of the 1789 ''

21 June 1982, third sitting

Jean Foyer: "Cette semaine, le ministre d'État, ministre de la recherche et de la technologie, nous présente un projet dont je dirai, ne parlant pas latin pour une fois, mais empruntant ma terminologie à la langue des physiciens, qu'il est pour l'essentiel un assemblage de neutrons législatifs, je veux dire de textes dont la charge juridique est nulle." – "This week, the minister of State, minister for research and technology /nowiki> /nowiki>Jean-Pierre_Chevènement">Jean-Pierre_Chevènement.html"_;"title="/nowiki>Jean-Pierre_Chevènement">/nowiki>Jean-Pierre_Chevènement/nowiki>_presents_us_a_bill_of_which_I'll_say,_without_talking_in_latin_for_once,_but_instead_borrowing_my_words_from_the_physicists,_that_it_is_mostly_an_assembly_of_legislative_neutrons,_I_mean_of_texts_with_a_null_juridical_charge." _Instead_of_prescribing_or_prohibiting,_as_advocated_by_Jean-Étienne-Marie_Portalis.html" ;"title="Jean-Pierre_Chevènement.html" ;"title="Jean-Pierre_Chevènement.html" ;"title="/nowiki>Jean-Pierre Chevènement">/nowiki>Jean-Pierre Chevènement">Jean-Pierre_Chevènement.html" ;"title="/nowiki>Jean-Pierre Chevènement">/nowiki>Jean-Pierre Chevènement/nowiki> presents us a bill of which I'll say, without talking in latin for once, but instead borrowing my words from the physicists, that it is mostly an assembly of legislative neutrons, I mean of texts with a null juridical charge." Instead of prescribing or prohibiting, as advocated by Jean-Étienne-Marie Portalis">Portalis, such language makes statements about the state of the world, or wishes about what it should be.

Previously, such language was considered devoid of juridical effects and thus harmless; but Mazeaud contended that introducing vague language devoid of juridical consequences dilutes law unnecessarily. He denounced the use of law as an instrument of political communication, expressing vague wishes rather than effective legislation. Mazeaud also said that, because of the constitutional objective that law should be accessible and understandable, law should be precise and clear, and devoid of details or equivocal formulas. The practice of the Parliament putting into laws remarks or wishes with no clear legal consequences has been a long-standing concern of French jurists.

, one law out of two, including the budget, was sent to the Council at the request of the opposition. In January 2005, Pierre Mazeaud, then president of the Council, publicly deplored the inflation of the number of constitutional review requests motivated by political concerns, without much legal argumentation to back them on constitutional grounds.

The

Comment saisir le Conseil constitutionnel ?

' "(How to file a request before the Constitutional Council?)" On 29 December 2012, the council said it was overturning an upper income tax rate of 75% due to be introduced in 2013.

Decision 98–408 DC

declaring that the sitting President of the Republic could be tried criminally only by the High Court of Justice, a special court organized by Parliament and originally meant for cases of high treason. This, in essence, ensured that

The Council is made up of former Presidents of the Republic who have chosen to sit in the Council (which they may not do if they become directly involved in politics again) and nine other members who serve non-renewable terms of nine years, one third of whom are appointed every three years, three each by the President of the Republic, the President of the National Assembly and the

The Council is made up of former Presidents of the Republic who have chosen to sit in the Council (which they may not do if they become directly involved in politics again) and nine other members who serve non-renewable terms of nine years, one third of whom are appointed every three years, three each by the President of the Republic, the President of the National Assembly and the

portant loi organique sur le Conseil constitutionnel ("

The Council sits in the

The Council sits in the

description of the Council's offices

on the Council's site

pp. 45–92

* F. L. Morton, ''Judicial Review in France: A Comparative Analysis'', The American Journal of Comparative Law, Vol. 36, No. 1 (Winter, 1988)

pp. 89–110

* James Beardsley, ''Constitutional Review in France'', The Supreme Court Review, Vol. 1975, (1975)

pp. 189–259

Official site

{{DEFAULTSORT:Constitutional Council of France Judiciary of France Constitutional law Government of France

France

France (), officially the French Republic ( ), is a country primarily located in Western Europe. It also comprises of Overseas France, overseas regions and territories in the Americas and the Atlantic Ocean, Atlantic, Pacific Ocean, Pac ...

. It was established by the Constitution of the Fifth Republic on 4 October 1958 to ensure that constitutional principles and rules are upheld. It is housed in the Palais-Royal

The Palais-Royal () is a former royal palace located in the 1st arrondissement of Paris, France. The screened entrance court faces the Place du Palais-Royal, opposite the Louvre. Originally called the Palais-Cardinal, it was built for Cardinal R ...

, Paris

Paris () is the capital and most populous city of France, with an estimated population of 2,165,423 residents in 2019 in an area of more than 105 km² (41 sq mi), making it the 30th most densely populated city in the world in 2020. Si ...

. Its main activity is to rule on whether proposed statutes conform with the Constitution, after they have been voted by Parliament

In modern politics, and history, a parliament is a legislative body of government. Generally, a modern parliament has three functions: representing the electorate, making laws, and overseeing the government via hearings and inquiries. Th ...

and before they are signed into law by the President of the Republic (''a priori'' review).

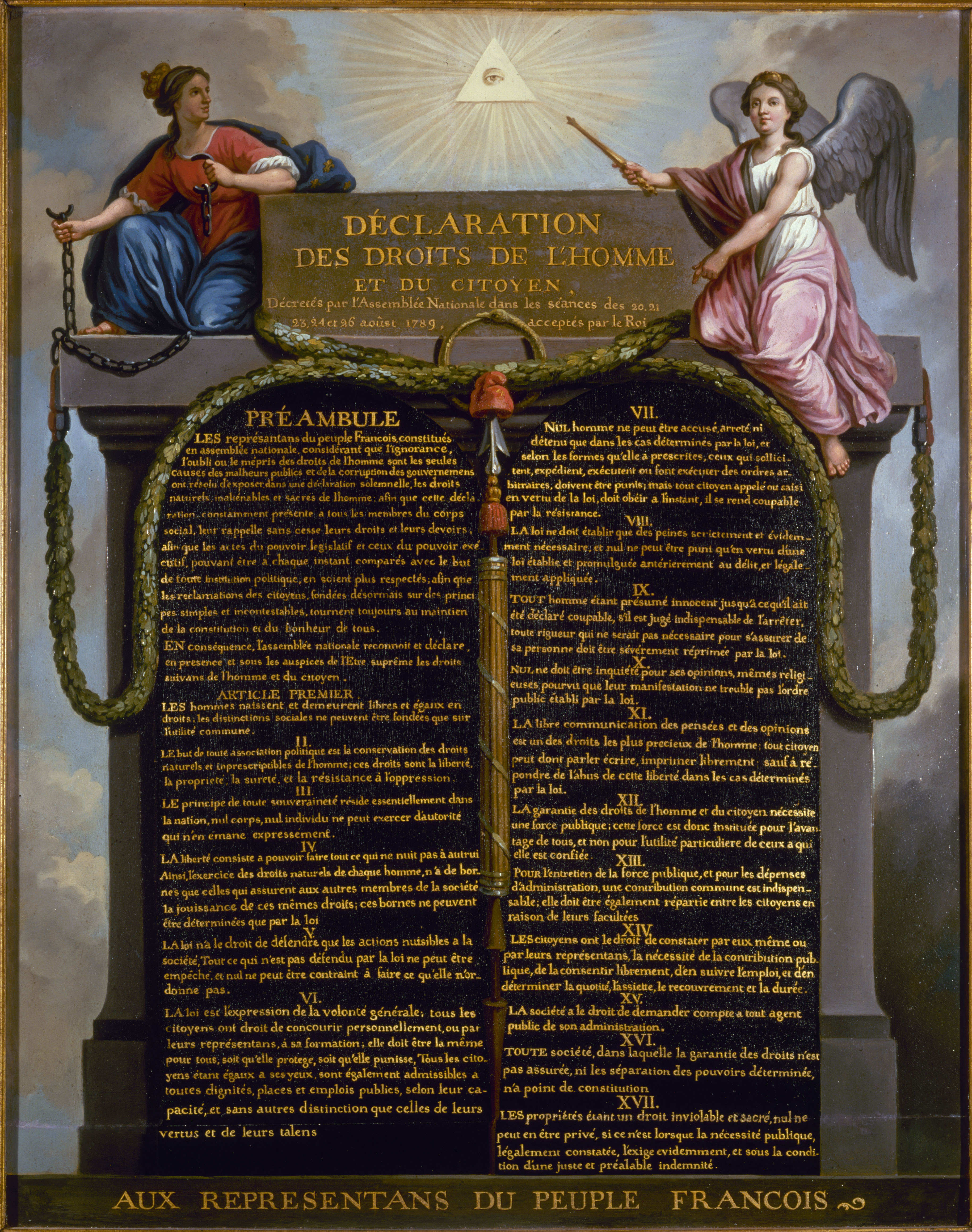

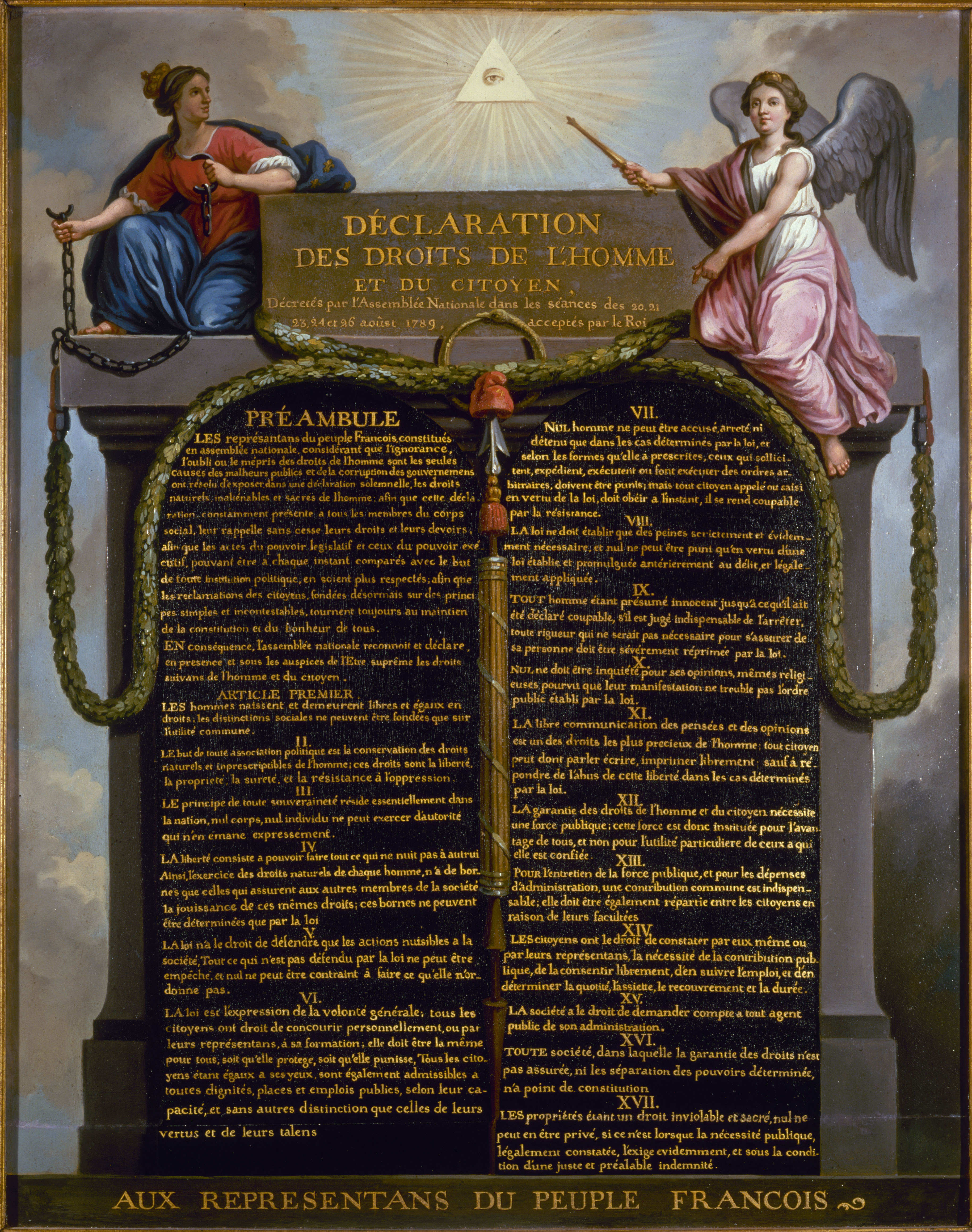

Since 1 March 2010, individual citizens who are party to a trial or a lawsuit have been able to ask for the Council to review whether the law applied in the case is constitutional ( review). In 1971, the Council ruled that conformity with the Constitution also entails conformity with two other texts referred to in the preamble of the Constitution, the Declaration of the Rights of Man and of the Citizen

The Declaration of the Rights of Man and of the Citizen (french: Déclaration des droits de l'homme et du citoyen de 1789, links=no), set by France's National Constituent Assembly in 1789, is a human civil rights document from the French Revol ...

and the preamble of the constitution of the Fourth Republic, both of which list constitutional rights.

Members are often referred to as ''les sages'' ("the sages") in the media and the general public, as well as in the Council's own documents. Legal theorist Arthur Dyevre notes that this "tends to make those who dare criticise them look unwise."

Powers and tasks

Overview

The Council has two main areas of power: # The first is the supervision of elections, both presidential andparliamentary

A parliamentary system, or parliamentarian democracy, is a system of democratic governance of a state (or subordinate entity) where the executive derives its democratic legitimacy from its ability to command the support ("confidence") of the ...

, and ensuring the legitimacy of referendum

A referendum (plural: referendums or less commonly referenda) is a Direct democracy, direct vote by the Constituency, electorate on a proposal, law, or political issue. This is in contrast to an issue being voted on by a Representative democr ...

s (Articles 58, 59 and 60). They issue the official results, ensure proper conduct and fairness, and see that campaign spending limits are adhered to. The Council is the supreme authority in these matters. The Council can declare an election to be invalid if improperly conducted, the winning candidate used illegal methods, or the winning candidate spent more than the legal limits for the campaign.

# The second area of Council power is the interpretation of the fundamental meanings of the constitution, procedure, legislation, and treaties. The Council can declare dispositions of laws to be contrary to the ''Constitution of France

The current Constitution of France was adopted on 4 October 1958. It is typically called the Constitution of the Fifth Republic , and it replaced the Constitution of the Fourth Republic of 1946 with the exception of the preamble per a Consti ...

'' or to the principles of constitutional value that it has deduced from the Constitution or from the ''Declaration of the Rights of Man and of the Citizen

The Declaration of the Rights of Man and of the Citizen (french: Déclaration des droits de l'homme et du citoyen de 1789, links=no), set by France's National Constituent Assembly in 1789, is a human civil rights document from the French Revol ...

''. It also may declare laws to be in contravention of treaties

A treaty is a formal, legally binding written agreement between actors in international law. It is usually made by and between sovereign states, but can include international organizations, individuals, business entities, and other legal pers ...

that France has signed, such as the ''European Convention on Human Rights

The European Convention on Human Rights (ECHR; formally the Convention for the Protection of Human Rights and Fundamental Freedoms) is an international convention to protect human rights and political freedoms in Europe. Drafted in 1950 by ...

.'' Their declaring that a law is contrary to constitutional or treaty principles renders it invalid. The Council also may impose reservations as to the interpretation of certain provisions in statutes. The decisions of the Council are binding on all authorities.

Examination of laws by the Council is compulsory for some acts, such as for organic bills, those which fundamentally affect government, and treaties, which need to be assessed by the Council before they are considered ratified (Article 61-1 and 54). Amendments concerning the rules governing parliamentary procedures need to be considered by the Council as well. Guidance may be sought from the Council in regard to whether reform should come under statute law (voted by Parliament) or whether issues are considered as (regulation) to be adopted with decree

A decree is a legal proclamation, usually issued by a head of state (such as the president of a republic or a monarch), according to certain procedures (usually established in a constitution). It has the force of law. The particular term used ...

of the Prime Minister

A prime minister, premier or chief of cabinet is the head of the cabinet and the leader of the ministers in the executive branch of government, often in a parliamentary or semi-presidential system. Under those systems, a prime minister is ...

. The re-definition of legislative dispositions as regulatory matters initially constituted a significant share of the (then light) caseload of the Council.

In the case of other statutes, seeking the oversight of the Council is not compulsory. However, the President of the Republic, the President of the Senate

A senate is a deliberative assembly, often the upper house or chamber of a bicameral legislature. The name comes from the ancient Roman Senate (Latin: ''Senatus''), so-called as an assembly of the senior (Latin: ''senex'' meaning "the el ...

, the President of the National Assembly

In politics, a national assembly is either a unicameral legislature, the lower house of a bicameral legislature, or both houses of a bicameral legislature together. In the English language it generally means "an assembly composed of the r ...

, the Prime Minister of France

The prime minister of France (french: link=no, Premier ministre français), officially the prime minister of the French Republic, is the head of government of the French Republic and the leader of the Council of Ministers.

The prime minister i ...

, 60 members of the National Assembly, or 60 Senators can submit a statute for examination by the Council before its signing into law by the President. In general, it is the parliamentary opposition

Opposition may refer to:

Arts and media

* ''Opposition'' (Altars EP), 2011 EP by Christian metalcore band Altars

* The Opposition (band), a London post-punk band

* '' The Opposition with Jordan Klepper'', a late-night television series on Com ...

that brings laws that it deems to infringe civil rights before the Council. Tony Prosser, ''Constitutions and Political Economy: The Privatisation of Public Enterprises in France and Great Britain'', The Modern Law Review, Vol. 53, No. 3 (May 1990)pp. 304–320

see p. 307 "The number of references has steadily grown; it is no exaggeration to claim that any important controversial legislation is now likely to be referred." Another task, of lesser importance in terms of number of referrals, is the reclassification of statute law into the domain of regulations on the Prime Minister's request. This happens when the Prime Minister and his government wish to alter law that has been enacted as statute law, but should instead belong to regulations according to the Constitution. The Prime Minister has to obtain reclassification from the Council prior to taking any

decree

A decree is a legal proclamation, usually issued by a head of state (such as the president of a republic or a monarch), according to certain procedures (usually established in a constitution). It has the force of law. The particular term used ...

changing the regulations. This, however, is nowadays only a small fraction of the Council's activity: in 2008, out 140 of decisions, only 5 concerned reclassifications.

Enactment of legislation

:''This article refers extensively to individual articles in the Constitution of France. The reader should refer to thofficial translation

of the Constitution on the site of the

French National Assembly

The National Assembly (french: link=no, italics=set, Assemblée nationale; ) is the lower house of the bicameral French Parliament under the Fifth Republic, the upper house being the Senate (). The National Assembly's legislators are kn ...

. Another recommended reading is thConstitutional Council overview

on the Council web site.''

The

The Government of France

The Government of France (French: ''Gouvernement français''), officially the Government of the French Republic (''Gouvernement de la République française'' ), exercises executive power in France. It is composed of the Prime Minister, who ...

consists of an executive branch

The Executive, also referred as the Executive branch or Executive power, is the term commonly used to describe that part of government which enforces the law, and has overall responsibility for the governance of a state.

In political systems ...

( President of the Republic, Prime Minister

A prime minister, premier or chief of cabinet is the head of the cabinet and the leader of the ministers in the executive branch of government, often in a parliamentary or semi-presidential system. Under those systems, a prime minister is ...

, ministers and their services and affiliated organisations); a legislative branch

A legislature is an assembly with the authority to make laws for a political entity such as a country or city. They are often contrasted with the executive and judicial powers of government.

Laws enacted by legislatures are usually known ...

(both houses of Parliament

In modern politics, and history, a parliament is a legislative body of government. Generally, a modern parliament has three functions: representing the electorate, making laws, and overseeing the government via hearings and inquiries. Th ...

); and a judicial branch

The judiciary (also known as the judicial system, judicature, judicial branch, judiciative branch, and court or judiciary system) is the system of courts that adjudicates legal disputes/disagreements and interprets, defends, and applies the law ...

.

The judicial branch

The judiciary (also known as the judicial system, judicature, judicial branch, judiciative branch, and court or judiciary system) is the system of courts that adjudicates legal disputes/disagreements and interprets, defends, and applies the law ...

does not constitute a single hierarchy:

* Administrative courts fall under the Council of State

A Council of State is a governmental body in a country, or a subdivision of a country, with a function that varies by jurisdiction. It may be the formal name for the cabinet or it may refer to a non-executive advisory body associated with a head o ...

,

* Civil and criminal courts under the Court of Cassation

A court of cassation is a high-instance court that exists in some judicial systems. Courts of cassation do not re-examine the facts of a case, they only interpret the relevant law. In this they are appellate courts of the highest instance. In th ...

,

* Some entities also have advisory functions.

For historical reasons, there has long been political hostility in the nation to the concept of a "Supreme Court"—that is, a powerful court able to quash legislation, because of the experience of citizens in the pre-Revolutionary era.James Beardsley, "Constitutional Review in France", ''The Supreme Court Review'', Vol. 1975, (1975)pp. 189–259

/ref>Michael H. Davis, ''The Law/Politics Distinction, the French Conseil Constitutionnel, and the

U. S. Supreme Court

The Supreme Court of the United States (SCOTUS) is the highest court in the federal judiciary of the United States. It has ultimate appellate jurisdiction over all U.S. federal court cases, and over state court cases that involve a point of ...

'', The American Journal of Comparative Law, Vol. 34, No. 1 (Winter, 1986)pp. 45–92

/ref>Denis Tallon, John N. Hazard, George A. Bermann, ''The Constitution and the Courts in France'', The American Journal of Comparative Law, Vol. 27, No. 4 (Autumn, 1979)

pp. 567–587

/ref> Whether the Constitutional Council is a court is a subject of academic discussion, but some scholars consider it effectively the

supreme court

A supreme court is the highest court within the hierarchy of courts in most legal jurisdictions. Other descriptions for such courts include court of last resort, apex court, and high (or final) court of appeal. Broadly speaking, the decisions of ...

of France.

The Constitution of the French Fifth Republic

The Fifth Republic (french: Cinquième République) is France's current republican system of government. It was established on 4 October 1958 by Charles de Gaulle under the Constitution of the Fifth Republic.. The Fifth Republic emerged from ...

distinguishes two kinds of legislation: statute law, which is normally voted upon by Parliament

In modern politics, and history, a parliament is a legislative body of government. Generally, a modern parliament has three functions: representing the electorate, making laws, and overseeing the government via hearings and inquiries. Th ...

(except for '' ordonnances''), and government regulations, which are enacted by the Prime Minister and his government as decree

A decree is a legal proclamation, usually issued by a head of state (such as the president of a republic or a monarch), according to certain procedures (usually established in a constitution). It has the force of law. The particular term used ...

s and other regulations (''arrêtés''). Article 34 of the Constitution exhaustively lists the areas reserved for statute law: these include, for instance, criminal law

Criminal law is the body of law that relates to crime. It prescribes conduct perceived as threatening, harmful, or otherwise endangering to the property, health, safety, and moral welfare of people inclusive of one's self. Most criminal law ...

.

Any regulation issued by the executive in the areas constitutionally reserved for statute law is unconstitutional unless it has been authorized by a statute as secondary legislation. Any citizen with an interest in the case can obtain the cancellation of these regulations by the Council of State

A Council of State is a governmental body in a country, or a subdivision of a country, with a function that varies by jurisdiction. It may be the formal name for the cabinet or it may refer to a non-executive advisory body associated with a head o ...

, on grounds that the executive has exceeded its authority. Furthermore, the Council of State can quash regulations on grounds that they violate existing statute law, constitutional rights, or the "general principles of law".

In addition, new acts can be referred to the Constitutional Council by a petition just prior to being signed into law by the President of the Republic. The most common circumstance for this is that 60 opposition members of the National Assembly

In politics, a national assembly is either a unicameral legislature, the lower house of a bicameral legislature, or both houses of a bicameral legislature together. In the English language it generally means "an assembly composed of the r ...

, or 60 opposition members of the Senate

A senate is a deliberative assembly, often the upper house or chamber of a bicameral legislature. The name comes from the ancient Roman Senate (Latin: ''Senatus''), so-called as an assembly of the senior (Latin: ''senex'' meaning "the el ...

request such a review.

If the Prime Minister thinks that some clauses of existing statute law instead belong to the domain of regulations, he can ask the Council to reclassify these clauses as regulations.

Traditionally, France refused to accept the idea that courts could quash legislation enacted by Parliament (though administrative courts could quash regulations produced by the executive). This reluctance was based in the French revolutionary era: pre-revolutionary courts had often used their power to refuse to register laws and thus prevent their application for political purposes, and had blocked reforms. French courts were prohibited from making rulings of a general nature. Also, politicians believed that, if courts could quash legislation after it had been enacted and taken into account by citizens, there would be too much legal uncertainty: how could a citizen plan his or her actions according to what is legal or not if laws could ''a posteriori'' be found not to hold? Yet, in the late 20th century, courts, especially administrative courts, began applying international treaties, including law of the European Union

The European Union (EU) is a supranational union, supranational political union, political and economic union of Member state of the European Union, member states that are located primarily in Europe, Europe. The union has a total area of ...

, as superior to national law.

A 2009 reform, effective on 1 March 2010, enables parties to a lawsuit or trial to question the constitutionality of the law that is being applied to them. The procedure, known as , is broadly as follows: the question is raised before the trial judge and, if it has merit, is forwarded to the appropriate supreme court (Council of State if the referral comes from an administrative court, Court of Cassation for other courts). The supreme court collects such referrals and submits them to the Constitutional Council. If the Constitutional Council rules a law to be unconstitutional, this law is struck down from the law books. The decision applies to everyone and not only to the cases at hand.

History and evolution

While since the 19th century the judicial review that the Constitutional Council brings to bear on the acts of the

While since the 19th century the judicial review that the Constitutional Council brings to bear on the acts of the executive branch

The Executive, also referred as the Executive branch or Executive power, is the term commonly used to describe that part of government which enforces the law, and has overall responsibility for the governance of a state.

In political systems ...

has played an increasingly large role, the politicians who have framed the successive French institutions have long been reluctant to have the judiciary review legislation. The argument was that un-elected judges should not be able to overrule directly the decisions of the democratically elected legislature. This may also have reflected the poor impression resulting from the political action of the parlement

A ''parlement'' (), under the French Ancien Régime, was a provincial appellate court of the Kingdom of France. In 1789, France had 13 parlements, the oldest and most important of which was the Parlement of Paris. While both the modern Fr ...

s – courts of justice under the ancien régime

''Ancien'' may refer to

* the French word for " ancient, old"

** Société des anciens textes français

* the French for "former, senior"

** Virelai ancien

** Ancien Régime

** Ancien Régime in France

{{disambig ...

monarchy: these courts often had chosen to block legislation in order to further the privileges of a small caste in the nation. The idea was that legislation was a political tool, and that the responsibility of legislation should be borne by the legislative body.

Originally, the Council was meant to have rather technical responsibilities: ensuring that national elections were fair, arbitrating the division between statute law (from the legislative) and regulation (from the executive), etc. The Council role of safekeeping fundamental rights was probably not originally intended by the drafters of the Constitution of the French Fifth Republic

The Fifth Republic (french: Cinquième République) is France's current republican system of government. It was established on 4 October 1958 by Charles de Gaulle under the Constitution of the Fifth Republic.. The Fifth Republic emerged from ...

: they believed that Parliament should be able to ensure that it did not infringe on such rights. However, the Council's activity has considerably extended since the 1970s, when questions of justice for larger groups of people became pressing.

From 1958 to 1970, under Charles de Gaulle

Charles André Joseph Marie de Gaulle (; ; (commonly abbreviated as CDG) 22 November 18909 November 1970) was a French army officer and statesman who led Free France against Nazi Germany in World War II and chaired the Provisional Governm ...

's presidency, the Constitutional Council was sometimes described as a "cannon aimed at Parliament", protecting the executive branch against encroachment by statute law voted by Parliament. All but one referral to the Constitutional Council came from the Prime Minister, against acts of Parliament, and the Council agreed to partial annulments in all cases. The only remaining referral came from the President of the Senate, Gaston Monnerville

Gaston Monnerville (2 January 1897 – 7 November 1991) was a French Radical politician and lawyer who served as the first President of the Senate under the Fifth Republic from 1958 to 1968. He previously served as President of the Council of th ...

, against the 1962 referendum on direct election of the President of the Republic, which Charles de Gaulle supported. The Council ruled that it was "incompetent" to cancel the direct expression of the will of the French people.

In 1971, however, the Council ruled unconstitutionalDecision 71-44DC

some provisions of a law changing the rules for the incorporation of private nonprofit associations, because they infringed on freedom of association, one of the principles of the 1789 ''

Declaration of the Rights of Man and of the Citizen

The Declaration of the Rights of Man and of the Citizen (french: Déclaration des droits de l'homme et du citoyen de 1789, links=no), set by France's National Constituent Assembly in 1789, is a human civil rights document from the French Revol ...

''; they used the fact that the preamble of the French constitution briefly referred to those principles to justify their decision. For the first time, a statute was declared unconstitutional not because it infringed on technical legal principles, but because it was deemed to infringe on personal freedoms of citizens.

In 1974, authority to request a constitutional review was extended to 60 members of the National Assembly or 60 senators. Soon, the political opposition seized that opportunity to request the review of all controversial acts.

The Council increasingly has discouraged " riders" (''cavaliers'') – amendments or clauses introduced into bills that have no relationship to the original topic of the bill; for instance, "budgetary riders" in the Budget bill, or "social riders" in the Social security budget bill. ''See legislative riders in France''. In January 2005, Pierre Mazeaud

Pierre Mazeaud (; born 24 August 1929) is a French jurist, politician and alpinist.

In February 2004, he was appointed president of the Constitutional Council of France by President of France Jacques Chirac, replacing Yves Guéna, until h ...

, then President of the Constitutional Council, announced that the Council would take a stricter view of language of a non-prescriptive character introduced in laws, sometimes known as "legislative neutrons".Proceedings of the National Assembly21 June 1982, third sitting

Jean Foyer: "Cette semaine, le ministre d'État, ministre de la recherche et de la technologie, nous présente un projet dont je dirai, ne parlant pas latin pour une fois, mais empruntant ma terminologie à la langue des physiciens, qu'il est pour l'essentiel un assemblage de neutrons législatifs, je veux dire de textes dont la charge juridique est nulle." – "This week, the minister of State, minister for research and technology

French constitutional law of 23 July 2008

The Constitutional law on the Modernisation of the Institutions of the Fifth Republic (french: link=no, loi constitutionnelle de modernisation des institutions de la Ve République) was enacted into French constitutional law by the Parliament of F ...

amended article 61 of the Constitution. It now allows for courts to submit questions of unconstitutionality of laws to the Constitutional Council. The Court of Cassation

A court of cassation is a high-instance court that exists in some judicial systems. Courts of cassation do not re-examine the facts of a case, they only interpret the relevant law. In this they are appellate courts of the highest instance. In th ...

(supreme court over civil and criminal courts) and the Council of State

A Council of State is a governmental body in a country, or a subdivision of a country, with a function that varies by jurisdiction. It may be the formal name for the cabinet or it may refer to a non-executive advisory body associated with a head o ...

(supreme court over administrative courts) each filter the requests coming from the courts under them.

'' Lois organiques,'' and other decisions organizing how this system functions, were subsequently adopted. The revised system was activated on 1 March 2010.Constitutional council, Comment saisir le Conseil constitutionnel ?

' "(How to file a request before the Constitutional Council?)" On 29 December 2012, the council said it was overturning an upper income tax rate of 75% due to be introduced in 2013.

Controversies

In 1995,Roland Dumas

Roland Dumas (; born 23 August 1922) is a French lawyer and Socialist politician who served as Foreign Minister under President François Mitterrand from 1984 to 1986 and from 1988 to 1993. He was also President of the Constitutional Council ...

was appointed president of the Council by François Mitterrand

François Marie Adrien Maurice Mitterrand (26 October 19168 January 1996) was President of France, serving under that position from 1981 to 1995, the longest time in office in the history of France. As First Secretary of the Socialist Party, he ...

. Dumas twice attracted major controversy. First, he was reported as party to scandals regarding the Elf Aquitaine

Elf Aquitaine is a French brand of oils and other motor products (such as brake fluids) for automobiles and trucks. Elf is a former petroleum company which merged with TotalFina to form "TotalFinaElf". The new company changed its name to Total ...

oil company, with many details regarding his mistress

Mistress is the feminine form of the English word "master" (''master'' + ''-ess'') and may refer to:

Romance and relationships

* Mistress (lover), a term for a woman who is in a sexual and romantic relationship with a man who is married to a d ...

, Christine Deviers-Joncour, and his expensive tastes in clothing being published in the press.

In this period, the Council issued some highly controversial opinions in a decision related to the International Criminal Court

The International Criminal Court (ICC or ICCt) is an intergovernmental organization and International court, international tribunal seated in The Hague, Netherlands. It is the first and only permanent international court with jurisdiction to pro ...

, iDecision 98–408 DC

declaring that the sitting President of the Republic could be tried criminally only by the High Court of Justice, a special court organized by Parliament and originally meant for cases of high treason. This, in essence, ensured that

Jacques Chirac

Jacques René Chirac (, , ; 29 November 193226 September 2019) was a Politics of France, French politician who served as President of France from 1995 to 2007. Chirac was previously Prime Minister of France from 1974 to 1976 and from 1986 to ...

would not face criminal charges until he left office. This controversial decision is now moot, since the Parliament redefined the rules of responsibility of the President of the Republic by the French constitutional law of 23 July 2008

The Constitutional law on the Modernisation of the Institutions of the Fifth Republic (french: link=no, loi constitutionnelle de modernisation des institutions de la Ve République) was enacted into French constitutional law by the Parliament of F ...

. In 1999, because of the Elf scandal, Dumas took official leave from the Council and Yves Guéna

Yves Guéna (; 6 July 1922 – 3 March 2016) was a French politician. In 1940, he joined the Free French Forces in the United Kingdom. He received several decorations for his courage.

Political life

He belonged to various right wing parties ...

assumed the interim presidency.

In 2005, the Council again attracted some controversy when Valéry Giscard d'Estaing

Valéry René Marie Georges Giscard d'Estaing (, , ; 2 February 19262 December 2020), also known as Giscard or VGE, was a French politician who served as President of France from 1974 to 1981.

After serving as Minister of Finance under prime ...

and Simone Veil

Simone Veil (; ; 13 July 1927 – 30 June 2017) was a French magistrate and politician who served as Health Minister in several governments and was President of the European Parliament from 1979 to 1982, the first woman to hold that office. ...

campaigned for the proposed European Constitution, which was submitted to the French voters in a referendum. Simone Veil had participated in the campaign after obtaining a leave of absence

The labour law concept of leave, specifically paid leave or, in some countries' long-form, a leave of absence, is an authorised prolonged absence from work, for any reason authorised by the workplace. When people "take leave" in this way, they are ...

from the Council. This action was criticized by some, including Jean-Louis Debré, president of the National Assembly

In politics, a national assembly is either a unicameral legislature, the lower house of a bicameral legislature, or both houses of a bicameral legislature together. In the English language it generally means "an assembly composed of the r ...

, who thought that prohibitions against appointed members of the council conducting partisan politics should not be evaded by their taking leave for the duration of a campaign. Veil defended herself by pointing to precedent; she said, "How is that his ebré'sbusiness? He has no lesson to teach me."

Membership

The Council is made up of former Presidents of the Republic who have chosen to sit in the Council (which they may not do if they become directly involved in politics again) and nine other members who serve non-renewable terms of nine years, one third of whom are appointed every three years, three each by the President of the Republic, the President of the National Assembly and the

The Council is made up of former Presidents of the Republic who have chosen to sit in the Council (which they may not do if they become directly involved in politics again) and nine other members who serve non-renewable terms of nine years, one third of whom are appointed every three years, three each by the President of the Republic, the President of the National Assembly and the President of the Senate

President of the Senate is a title often given to the presiding officer of a senate. It corresponds to the speaker in some other assemblies.

The senate president often ranks high in a jurisdiction's succession for its top executive office: for ex ...

.Ordonnance n°58-1067 du 7 novembre 1958portant loi organique sur le Conseil constitutionnel ("

Ordinance

Ordinance may refer to:

Law

* Ordinance (Belgium), a law adopted by the Brussels Parliament or the Common Community Commission

* Ordinance (India), a temporary law promulgated by the President of India on recommendation of the Union Cabinet

* ...

58-1067 of 7 November 1958, organic bill on the Constitutional council"). About swearing-in: article 3 says ''Avant d'entrer en fonction, les membres nommés du Conseil constitutionnel prêtent serment devant le Président de la République.'' ("Before assuming their duties, the appointed members of the Constitutional council are sworn in before the President of the Republic.") The President of the Constitutional Council is selected by the President of the Republic for a term of nine years. If the position becomes vacant, the oldest member becomes interim president.

Following the 2008 constitutional revision, appointments to the Council are subject to a parliamentary approval process (Constitution of France, articles 13 and 56). , these provisions are not operational yet since the relevant procedures have not yet been set in law.

A quorum

A quorum is the minimum number of members of a deliberative assembly (a body that uses parliamentary procedure, such as a legislature) necessary to conduct the business of that group. According to '' Robert's Rules of Order Newly Revised'', the ...

of seven members is imposed unless exceptional circumstances are noted. Votes are by majority of the members present at the meeting; the president of the Council has a casting vote in case of an equal split. For decisions about the incapacity of the President of the Republic, a majority of the members of the council is needed.

Current members

, the current members are: * Laurent Fabius, appointed President of the Council by President of the RepublicFrançois Hollande

François Gérard Georges Nicolas Hollande (; born 12 August 1954) is a French politician who served as President of France from 2012 to 2017. He previously was First Secretary of the Socialist Party (France), First Secretary of the Socialist P ...

in March 2016

* Corinne Luquiens, appointed by the President of the National Assembly Claude Bartolone

Claude Bartolone (; born 1951) is a Tunisian-born French politician who was President of the National Assembly of France from 2012 to 2017. A member of the Socialist Party, he was first elected to the National Assembly, representing the Seine-S ...

in March 2016

* Michel Pinault, appointed by the President of the Senate Gérard Larcher in February 2016

* Alain Juppé

Alain Marie Juppé (; born 15 August 1945) is a French politician. A member of The Republicans, he was Prime Minister of France from 1995 to 1997 under President Jacques Chirac, during which period he faced major strikes that paralysed the cou ...

, appointed by the President of the National Assembly Richard Ferrand in March 2019

* Jacques Mézard

Jacques Mézard (born 3 December 1947) is a French lawyer and politician of the Radical Party of the Left who has been serving as a member of the Constitutional Council since 2019. He previously served as Minister of Agriculture and Food in 2017 ...

, appointed by the President of the Republic Emmanuel Macron

Emmanuel Macron (; born 21 December 1977) is a French politician who has served as President of France since 2017. ''Ex officio'', he is also one of the two Co-Princes of Andorra. Prior to his presidency, Macron served as Minister of Econ ...

in March 2019

* François Pillet

François Pillet (born 13 May 1950) is a French lawyer and politician who has served as a member of the Constitutional Council since 2019. Pillet was previously senator for the department of Cher from 2007 to 2019. He is a member of The Republic ...

, appointed by the President of the Senate Gérard Larcher in March 2019

* Jacqueline Gourault

Jacqueline Gourault (; née Doliveux, born 20 November 1950) is a French politician who served as Minister of Territorial Cohesion and Relations with Local Authorities in the governments of successive Prime Ministers Édouard Philippe and Jean C ...

, appointed by the President of the Republic Emmanuel Macron

Emmanuel Macron (; born 21 December 1977) is a French politician who has served as President of France since 2017. ''Ex officio'', he is also one of the two Co-Princes of Andorra. Prior to his presidency, Macron served as Minister of Econ ...

in March 2022

* Véronique Malbec, appointed by the President of the National Assembly Richard Ferrand in March 2022

* François Seners, appointed by the President of the Senate Gérard Larcher in March 2022

, the following members do not sit but can if they choose to:

* Nicolas Sarkozy

Nicolas Paul Stéphane Sarközy de Nagy-Bocsa (; ; born 28 January 1955) is a French politician who served as President of France from 2007 to 2012.

Born in Paris, he is of Hungarian, Greek Jewish, and French origin. Mayor of Neuilly-sur-Se ...

, former President of the Republic since May 2012, sat from May 2012 to July 2013

* François Hollande

François Gérard Georges Nicolas Hollande (; born 12 August 1954) is a French politician who served as President of France from 2012 to 2017. He previously was First Secretary of the Socialist Party (France), First Secretary of the Socialist P ...

, former President of the Republic since May 2017, pledged never to sit

The members of the Constitutional Council are sworn in by the President of the Republic. Former officeholders have the option to sit if they choose to do so. The members of the Constitutional Council should abstain from partisanship. They should refrain from making declarations that could lead them to be suspected of partisanship. The possibility for former presidents to sit in the Council is a topic of moderate controversy; some see it as incompatible with the absence of partisanship. René Coty

Jules Gustave René Coty (; 20 March 188222 November 1962) was President of France from 1954 to 1959. He was the second and last president of the Fourth French Republic.

Early life and politics

René Coty was born in Le Havre and studied at t ...

, Vincent Auriol

Vincent Jules Auriol (; 27 August 1884 – 1 January 1966) was a French politician who served as President of France from 1947 to 1954.

Early life and politics

Auriol was born in Revel, Haute-Garonne, as the only child of Jacques Antoine Auri ...

, Valéry Giscard d'Estaing

Valéry René Marie Georges Giscard d'Estaing (, , ; 2 February 19262 December 2020), also known as Giscard or VGE, was a French politician who served as President of France from 1974 to 1981.

After serving as Minister of Finance under prime ...

, Jacques Chirac

Jacques René Chirac (, , ; 29 November 193226 September 2019) was a Politics of France, French politician who served as President of France from 1995 to 2007. Chirac was previously Prime Minister of France from 1974 to 1976 and from 1986 to ...

and Nicolas Sarkozy

Nicolas Paul Stéphane Sarközy de Nagy-Bocsa (; ; born 28 January 1955) is a French politician who served as President of France from 2007 to 2012.

Born in Paris, he is of Hungarian, Greek Jewish, and French origin. Mayor of Neuilly-sur-Se ...

are the only former Presidents of France to have sat in the Constitutional Council.

List of presidents of the Constitutional Council

The following persons have served as President of the Constitutional Council: * Léon Noël, 5 March 1959 to 5 March 1965 * Gaston Palewski, 5 March 1965 to 5 March 1974 *Roger Frey

Roger Frey (11 June 1913, Nouméa, New Caledonia – 13 September 1997) was a French politician. His parents were of Alsatian origin. He was Minister of the Interior and president of the Constitutional Council of France.

Political career

In 19 ...

, 5 March 1974 to 4 March 1983

* Daniel Mayer, 4 March 1983 to 4 March 1986

* Robert Badinter

Robert Badinter (; born 30 March 1928) is a French lawyer, politician and author who enacted the abolition of the death penalty in France in 1981, while serving as Minister of Justice under François Mitterrand. He has also served in high-lev ...

, 4 March 1986 to 4 March 1995

* Roland Dumas

Roland Dumas (; born 23 August 1922) is a French lawyer and Socialist politician who served as Foreign Minister under President François Mitterrand from 1984 to 1986 and from 1988 to 1993. He was also President of the Constitutional Council ...

, 8 March 1995 to 1 March 2000

* Yves Guéna

Yves Guéna (; 6 July 1922 – 3 March 2016) was a French politician. In 1940, he joined the Free French Forces in the United Kingdom. He received several decorations for his courage.

Political life

He belonged to various right wing parties ...

, 1 March 2000 to 9 March 2004

* Pierre Mazeaud

Pierre Mazeaud (; born 24 August 1929) is a French jurist, politician and alpinist.

In February 2004, he was appointed president of the Constitutional Council of France by President of France Jacques Chirac, replacing Yves Guéna, until h ...

, 9 March 2004 to 3 March 2007

* Jean-Louis Debré, 5 March 2007 to 4 March 2016

* Laurent Fabius, since 8 March 2016

Location

Palais-Royal

The Palais-Royal () is a former royal palace located in the 1st arrondissement of Paris, France. The screened entrance court faces the Place du Palais-Royal, opposite the Louvre. Originally called the Palais-Cardinal, it was built for Cardinal R ...

(which also houses the Ministry of Culture) in Paris near the Council of State

A Council of State is a governmental body in a country, or a subdivision of a country, with a function that varies by jurisdiction. It may be the formal name for the cabinet or it may refer to a non-executive advisory body associated with a head o ...

.Sedescription of the Council's offices

on the Council's site

See also

* Constitutional economics * Constitutionalism * in modern law the ''Cour d'assises

In France, a ''cour d'assises'', or Court of Assizes or Assize Court, is a criminal trial court with original and appellate limited jurisdiction to hear cases involving defendants accused of felonies, meaning crimes as defined in French law. I ...

'' exists only in the French judiciary and other civil law jurisdictions, i.e.

** Corte d'Assise Italian Cour d'assises

** Belgian Cour d'assises

* it may also refer to obsolete courts in a number of common law jurisdictions, for example:

** Assizes

The courts of assize, or assizes (), were periodic courts held around England and Wales until 1972, when together with the quarter sessions they were abolished by the Courts Act 1971 and replaced by a single permanent Crown Court. The assizes ...

** Assizes (Ireland)

The courts of assizes or assizes were the higher criminal court in Ireland outside Dublin prior to 1924 (and continued in Northern Ireland until 1978). They have now been abolished in both jurisdictions.

Jurisdiction

The assizes had jurisdiction ...

* or royal writs, for example:

** Assize of Clarendon

The Assize of Clarendon was an act of Henry II of England in 1166 that began a transformation of English law and led to trial by jury in common law countries worldwide, and that established assize courts.

Prior systems for deciding the winning ...

** Assize of Northampton

* ''Cour de cassation

A court of cassation is a high-instance court that exists in some judicial systems. Courts of cassation do not re-examine the facts of a case, they only interpret the relevant law. In this they are appellate courts of the highest instance. In t ...

'', highest judicial court in France

* '' Conseil d'Etat'', supreme court for administrative justice in France

* Court of cassation

A court of cassation is a high-instance court that exists in some judicial systems. Courts of cassation do not re-examine the facts of a case, they only interpret the relevant law. In this they are appellate courts of the highest instance. In th ...

, general discussion, mostly dealing with common law jurisdictions

* Court of Appeal (France)—Court of Appeal in France. Differs considerably from appeals process in common law

In law, common law (also known as judicial precedent, judge-made law, or case law) is the body of law created by judges and similar quasi-judicial tribunals by virtue of being stated in written opinions."The common law is not a brooding omniprese ...

countries, in particular, certain types of court cases are appealed to courts called something other than "court of appeal"

* Cour d'appel

A court of appeals, also called a court of appeal, appellate court, appeal court, court of second instance or second instance court, is any court of law that is empowered to hear an appeal of a trial court or other lower tribunal. In much of t ...

– redirect to Court of Appeal (France)

* Court of Appeal

A court of appeals, also called a court of appeal, appellate court, appeal court, court of second instance or second instance court, is any court of law that is empowered to hear an appeal of a trial court or other lower tribunal. In much ...

, Court of Appeals

A court of appeals, also called a court of appeal, appellate court, appeal court, court of second instance or second instance court, is any court of law that is empowered to hear an appeal of a trial court or other lower tribunal. In much ...

—redirect to Appellate court

A court of appeals, also called a court of appeal, appellate court, appeal court, court of second instance or second instance court, is any court of law that is empowered to hear an appeal of a trial court or other lower tribunal. In much of ...

, the courts of second instance and appeals process in common law countries, which differs considerably from French appeal process

* Judiciary

The judiciary (also known as the judicial system, judicature, judicial branch, judiciative branch, and court or judiciary system) is the system of courts that adjudicates legal disputes/disagreements and interprets, defends, and applies the law ...

* Judiciary of France

In France, career judges are considered civil servants exercising one of the sovereign powers of the state, so French citizens are eligible for judgeship, but not citizens of the other EU countries. France's independent court system enjoys specia ...

* Jurisprudence

Jurisprudence, or legal theory, is the theoretical study of the propriety of law. Scholars of jurisprudence seek to explain the nature of law in its most general form and they also seek to achieve a deeper understanding of legal reasoning ...

* '' Ministère public'', shares some but not all characteristics of the prosecutor

A prosecutor is a legal representative of the prosecution in states with either the common law adversarial system or the civil law inquisitorial system. The prosecution is the legal party responsible for presenting the case in a criminal tria ...

in common law jurisdictions. In France the '' procureur'' is considered a magistrate

The term magistrate is used in a variety of systems of governments and laws to refer to a civilian officer who administers the law. In ancient Rome, a '' magistratus'' was one of the highest ranking government officers, and possessed both judic ...

and investigations are typically carried out by a '' juge d'instruction''

* Police Tribunal (France)

* Rule According to Higher Law

* Tribunal correctionnel (France)

* Criminal responsibility in French law Criminal responsibility in French criminal law is the obligation to answer for infractions committed and to suffer the punishment provided by the legislation that governs the infraction in question.

In a democracy citizens have rights but also du ...

References

Further reading

Books

* Pierre Avril, Jean Gicquel, ''Le Conseil constitutionnel'', 5th ed., Montchrestien, 2005, * * * * Frédéric Monera, ''L'idée de République et la jurisprudence du Conseil constitutionnel'', L.G.D.J., 2004, * Henry Roussillon, ''Le Conseil constitutionnel'', 6th ed., Dalloz, 2008, * Michel Verpeaux, Maryvonne Bonnard, eds.; ''Le Conseil Constitutionnel'', La Documentation Française, 2007, * Alec Stone, ''The Birth of Judicial Politics in France: The Constitutional Council in Comparative Perspective'', Oxford University Press,1992, * Martin A. Rogoff, "French Constitutional Law: Cases and Materials" – Durham, North Carolina: Carolina Academic Press, 201Articles

* Michael H. Davis, ''The Law/Politics Distinction, the French Conseil Constitutionnel, and theU. S. Supreme Court

The Supreme Court of the United States (SCOTUS) is the highest court in the federal judiciary of the United States. It has ultimate appellate jurisdiction over all U.S. federal court cases, and over state court cases that involve a point of ...

'', The American Journal of Comparative Law, Vol. 34, No. 1 (Winter, 1986)pp. 45–92

* F. L. Morton, ''Judicial Review in France: A Comparative Analysis'', The American Journal of Comparative Law, Vol. 36, No. 1 (Winter, 1988)

pp. 89–110

* James Beardsley, ''Constitutional Review in France'', The Supreme Court Review, Vol. 1975, (1975)

pp. 189–259

External links

Official site

{{DEFAULTSORT:Constitutional Council of France Judiciary of France Constitutional law Government of France

France

France (), officially the French Republic ( ), is a country primarily located in Western Europe. It also comprises of Overseas France, overseas regions and territories in the Americas and the Atlantic Ocean, Atlantic, Pacific Ocean, Pac ...

France

France (), officially the French Republic ( ), is a country primarily located in Western Europe. It also comprises of Overseas France, overseas regions and territories in the Americas and the Atlantic Ocean, Atlantic, Pacific Ocean, Pac ...

Government agencies established in 1958

1958 establishments in France

France

France (), officially the French Republic ( ), is a country primarily located in Western Europe. It also comprises of Overseas France, overseas regions and territories in the Americas and the Atlantic Ocean, Atlantic, Pacific Ocean, Pac ...

Courts and tribunals established in 1958