Conquest of California on:

[Wikipedia]

[Google]

[Amazon]

The Conquest of California, also known as the Conquest of Alta California or the California Campaign, was an important military campaign of the

On June 14, 1846, the

On June 14, 1846, the

Prior to the Mexican–American War, preparations for a possible conflict led to the U.S.

Prior to the Mexican–American War, preparations for a possible conflict led to the U.S.  To supplement this remaining force, Commodore Stockton ordered Captain

To supplement this remaining force, Commodore Stockton ordered Captain

Soon afterward, 200 reinforcements sent by Stockton and led by U.S. Navy Captain William Mervine were repulsed on October 8 in the one-hour Battle of Dominguez Rancho on

Soon afterward, 200 reinforcements sent by Stockton and led by U.S. Navy Captain William Mervine were repulsed on October 8 in the one-hour Battle of Dominguez Rancho on

In July 1846, Colonel

In July 1846, Colonel  After desertions and deaths in transit the four ships brought 648 men to California. The companies were then deployed throughout Upper Alta California and Lower Baja California on the Baja California Peninsula (captured by the Navy and later returned to Mexico), from San Francisco to

After desertions and deaths in transit the four ships brought 648 men to California. The companies were then deployed throughout Upper Alta California and Lower Baja California on the Baja California Peninsula (captured by the Navy and later returned to Mexico), from San Francisco to  ;Mormon Battalion

The

;Mormon Battalion

The

Hubert Howe Bancroft. ''The Works of Hubert Howe Bancroft,''

vol 22 (1886), ''History of California'' 1846–48; complete text online; famous, highly detailed narrative written in the 1880s. Also a

* * Harlow, Neal ''California Conquered: The Annexation of a Mexican Province 1846–1850'', , (1982) * Hittell, Theodore Henry. ''History of California'' vol 2 (1885

online

* Nevins, Allan. ''Fremont: Pathmarker of the West, Volume 1: Fremont the Explorer'' (1939, rev ed. 1955) * Rawls, James and Walton Bean. ''California: An Interpretive History'' (8th ed 2003), college textbook; the latest version of Bean's solid 1968 text

A Continent Divided: The U.S. – Mexico War

– ''from the Center for Greater Southwestern Studies, the University of Texas at Arlington''.

Map of Mexico and the United States during the California Campaign at omniatlas.com

{{Authority control Mexican California

Mexican–American War

The Mexican–American War, also known in the United States as the Mexican War and in Mexico as the (''United States intervention in Mexico''), was an armed conflict between the United States and Mexico from 1846 to 1848. It followed the ...

carried out by the United States in Alta California

Alta California ('Upper California'), also known as ('New California') among other names, was a province of New Spain, formally established in 1804. Along with the Baja California peninsula, it had previously comprised the province of , but ...

(modern-day California

California is a state in the Western United States, located along the Pacific Coast. With nearly 39.2million residents across a total area of approximately , it is the most populous U.S. state and the 3rd largest by area. It is also the m ...

), then a part of Mexico. The conquest lasted from 1846 into 1847, until military leaders from both the Californios and Americans signed the Treaty of Cahuenga

The Treaty of Cahuenga ( es, Tratado de Cahuenga), also called the Capitulation of Cahuenga (''Capitulación de Cahuenga''), was an 1847 agreement that ended the Conquest of California, resulting in a ceasefire between Californios and Americans. T ...

, which ended the conflict in California.

Background

When war was declared on May 13, 1846 between the United States and Mexico, it took almost three months for definitive word of Congress' declaration of war to reach the Pacific coast. U.S. consul Thomas O. Larkin, stationed in the pueblo of Monterey, was concerned about the increasing possibility of war and worked to prevent bloodshed between the Americans and the small Mexican military garrison at thePresidio of Monterey

The Presidio of Monterey (POM), located in Monterey, California, is an active US Army installation with historic ties to the Spanish colonial era. Currently, it is the home of the Defense Language Institute Foreign Language Center (DLI-FLC). ...

, commanded by José Castro.

United States Army Captain John C. Frémont

John Charles Frémont or Fremont (January 21, 1813July 13, 1890) was an American explorer, military officer, and politician. He was a U.S. Senator from California and was the first Republican nominee for president of the United States in 1856 ...

, on a survey expedition of the U.S. Army Corps of Topographical Engineers with about 60 well-armed men, crossed the Sierra Nevada

The Sierra Nevada () is a mountain range in the Western United States, between the Central Valley of California and the Great Basin. The vast majority of the range lies in the state of California, although the Carson Range spur lies primar ...

range in December 1845. They had reached the Oregon Territory by May 1846, when Frémont received word that war between Mexico and the U.S. was imminent.

Bear Flag Revolt

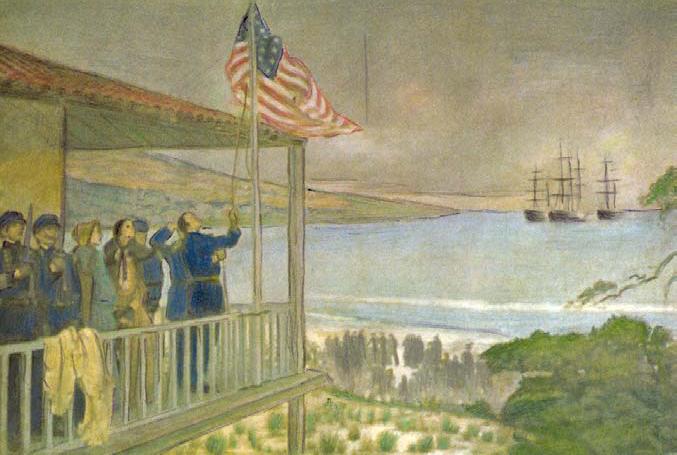

On June 14, 1846, the

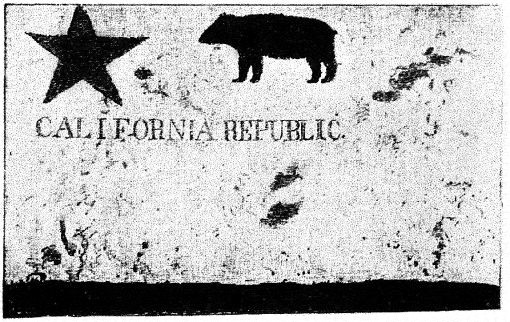

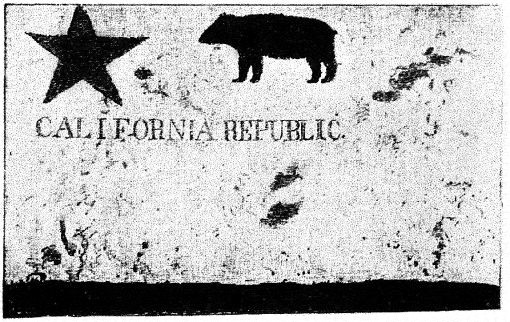

On June 14, 1846, the Bear Flag Revolt

The California Republic ( es, La República de California), or Bear Flag Republic, was an unrecognized breakaway state from Mexico, that for 25 days in 1846 militarily controlled an area north of San Francisco, in and around what is now S ...

occurred when some 30 rebels, mostly American pioneers, staged a revolt in response to government threats of expulsion and seized the small Mexican Sonoma Barracks

The Sonoma Barracks (Spanish: ''Cuartel de Sonoma'') is a two-story, wide-balconied, adobe building facing the central plaza of the City of Sonoma, California. It was built by order of Mariano Guadalupe Vallejo to house the Mexican soldiers that ...

garrison, in the pueblo of Sonoma north of San Francisco Bay

San Francisco Bay is a large tidal estuary in the U.S. state of California, and gives its name to the San Francisco Bay Area. It is dominated by the big cities of San Francisco, San Jose, and Oakland.

San Francisco Bay drains water f ...

. There they formed the California Republic

The California Republic ( es, La República de California), or Bear Flag Republic, was an unrecognized breakaway state from Mexico, that for 25 days in 1846 militarily controlled an area north of San Francisco, in and around what is now So ...

, created the " Bear Flag", and raised it over Sonoma. Eleven days later, troops led by Frémont, who had acted on his own authority, arrived from Sutter's Fort

Sutter's Fort was a 19th-century agricultural and trade colony in the Mexican '' Alta California'' province.National Park Service"California National Historic Trail."/ref> The site of the fort was established in 1839 and originally called New Hel ...

to support the rebels. No government was ever organized, but the Bear Flag Revolt

The California Republic ( es, La República de California), or Bear Flag Republic, was an unrecognized breakaway state from Mexico, that for 25 days in 1846 militarily controlled an area north of San Francisco, in and around what is now S ...

has become part of the state's folklore. The present-day California state flag is based on this original Bear Flag, and continues to display the words "California Republic."

Northern California

Prior to the Mexican–American War, preparations for a possible conflict led to the U.S.

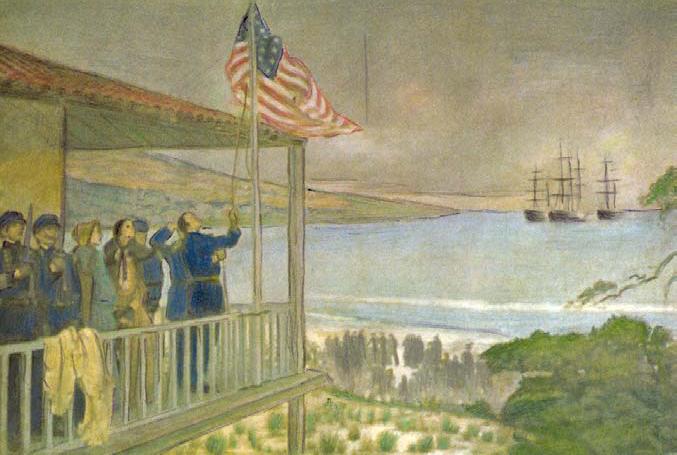

Prior to the Mexican–American War, preparations for a possible conflict led to the U.S. Pacific Squadron

The Pacific Squadron was part of the United States Navy squadron stationed in the Pacific Ocean in the 19th and early 20th centuries. Initially with no United States ports in the Pacific, they operated out of storeships which provided naval s ...

being extensively reinforced until it had roughly half of the ships in the United States Navy

The United States Navy (USN) is the maritime service branch of the United States Armed Forces and one of the eight uniformed services of the United States. It is the largest and most powerful navy in the world, with the estimated tonnage ...

. Since it took 120 to over 200 days to sail from Atlantic ports on the east coast, around Cape Horn

Cape Horn ( es, Cabo de Hornos, ) is the southernmost headland of the Tierra del Fuego archipelago of southern Chile, and is located on the small Hornos Island. Although not the most southerly point of South America (which are the Diego Ramí ...

, to the Pacific ports in the Sandwich Islands and then the mainland west coast, these movements had to be made well in advance of any possible conflict to be effective. Initially, with no United States ports in the Pacific, the squadron's ships operated out of storeships that provided naval supplies, purchased food and obtained water from local ports of call in the Sandwich Islands and on the Pacific coast. Their orders were, upon determining "beyond a doubt" that war had been declared, to capture the ports and cities of Alta California.

Commodore John Drake Sloat

John Drake Sloat (July 26, 1781 – November 28, 1867) was a commodore in the United States Navy who, in 1846, claimed California for the United States.

Life

He was born at the family home of Sloat House in Sloatsburg, New York, of Dutch ancestr ...

, commander of the Pacific Squadron, on being informed of an outbreak of hostilities between Mexico and the United States, as well as the Bear Flag Revolt

The California Republic ( es, La República de California), or Bear Flag Republic, was an unrecognized breakaway state from Mexico, that for 25 days in 1846 militarily controlled an area north of San Francisco, in and around what is now S ...

in Sonoma, ordered his naval forces to occupy ports in northern Alta California. Sloat's ships already in the Monterey harbor, the , , and , captured the Alta Californian capital city of Monterey in the "Battle of Monterey

The Battle of Monterey, at Monterey, California, occurred on 7 July 1846, during the Mexican–American War. The United States captured the town unopposed.

Prelude

In February 1845, at the Battle of Providencia, the Californio forces had ous ...

" on July 7, 1846 without firing a shot. Two days later on July 9, , which had been berthed at Sausalito, captured Yerba Buena (present-day San Francisco) in the " Battle of Yerba Buena", again without firing a shot. On July 15, Sloat transferred his command to Commodore Robert F. Stockton

Robert Field Stockton (August 20, 1795 – October 7, 1866) was a United States Navy commodore, notable in the capture of California during the Mexican–American War. He was a naval innovator and an early advocate for a propeller-driven, steam- ...

, a much more aggressive leader. Convincing news of a state of war between the U.S. and Mexico had previously reached Stockton. The 400 to 650 marines

Marines, or naval infantry, are typically a military force trained to operate in littoral zones in support of naval operations. Historically, tasks undertaken by marines have included helping maintain discipline and order aboard the ship (refl ...

and bluejackets (sailors) of Stockton's Pacific Squadron were the largest U.S. ground force in California. The rest of Stockton's men were needed to man his vessels.

To supplement this remaining force, Commodore Stockton ordered Captain

To supplement this remaining force, Commodore Stockton ordered Captain John C. Frémont

John Charles Frémont or Fremont (January 21, 1813July 13, 1890) was an American explorer, military officer, and politician. He was a U.S. Senator from California and was the first Republican nominee for president of the United States in 1856 ...

, on the U.S. Army Corps of Topographical Engineers survey, to secure 100 volunteers (he received 160) in addition to the California Battalion

The California Battalion (also called the first California Volunteer Militia and U.S. Mounted Rifles) was formed during the Mexican–American War (1846–1848) in present-day California, United States. It was led by U.S. Army Brevet Lieutenant C ...

he had earlier organized. They were to act primarily as occupation forces to free up Stockton's marines and sailors. The core of the California Battalion was the approximately 30 army personnel and 30 scouts, guards, ex-fur trappers, Indians, geographers, topographer

Topography is the study of the forms and features of land surfaces. The topography of an area may refer to the land forms and features themselves, or a description or depiction in maps.

Topography is a field of geoscience and planetary sci ...

s and cartographers in Frémont's exploration force, which was joined by about 150 Bear Flaggers. The American marines, sailors, and militia easily took over the cities and ports of northern California; within days they controlled Monterey, San Francisco

San Francisco (; Spanish for " Saint Francis"), officially the City and County of San Francisco, is the commercial, financial, and cultural center of Northern California. The city proper is the fourth most populous in California and 17t ...

, Sonoma, Sutter's Fort

Sutter's Fort was a 19th-century agricultural and trade colony in the Mexican '' Alta California'' province.National Park Service"California National Historic Trail."/ref> The site of the fort was established in 1839 and originally called New Hel ...

, New Helvetia, and other small pueblos in northern Alta California. Nearly all were occupied without a shot being fired. Some of the southern pueblos and ports were also rapidly occupied, with almost no bloodshed.

Southern California

Californios and the war

Prior to the U.S. occupation, the population of Spanish and Mexican people in Alta California was approximately 1500 men and 6500 women and children, who were known as ''Californio

Californio (plural Californios) is a term used to designate a Hispanic Californian, especially those descended from Spanish and Mexican settlers of the 17th through 19th centuries. California's Spanish-speaking community has resided there sin ...

s''. Many lived in or near the small Pueblo of Los Angeles

In the Southwestern United States, Pueblo (capitalized) refers to the Native tribes of Puebloans having fixed-location communities with permanent buildings which also are called pueblos (lowercased). The Spanish explorers of northern New Spain ...

(present-day Los Angeles

Los Angeles ( ; es, Los Ángeles, link=no , ), often referred to by its initials L.A., is the largest city in the state of California and the second most populous city in the United States after New York City, as well as one of the world ...

). Many other Californios lived on the 455 ranchos of Alta California, which contained slightly more than , nearly all bestowed by the Spanish and then Mexican governors with an average of about each.

Most of the approximately 800 American and other immigrants (primarily adult males) lived in the northern half of California, approved of breaking from the Mexican government, and gave only token to no resistance to the forces of Stockton and Frémont.

Siege of Los Angeles

In Southern California, Mexican General José Castro and Alta California GovernorPío Pico

Don Pío de Jesús Pico (May 5, 1801 – September 11, 1894) was a Californio politician, ranchero, and entrepreneur, famous for serving as the last governor of California (present-day U.S. state of California) under Mexican rule. A member of t ...

fled the Pueblo of Los Angeles

In the Southwestern United States, Pueblo (capitalized) refers to the Native tribes of Puebloans having fixed-location communities with permanent buildings which also are called pueblos (lowercased). The Spanish explorers of northern New Spain ...

before the arrival of American forces. On August 13, 1846, when Stockton's forces entered Los Angeles with no resistance, the nearly bloodless conquest of California seemed complete. The force of 36 that Stockton left in Los Angeles, however, was too small and, in addition, enforced a tyrannical control of the citizenry. On September 29, in the Siege of Los Angeles, the independent Californio

Californio (plural Californios) is a term used to designate a Hispanic Californian, especially those descended from Spanish and Mexican settlers of the 17th through 19th centuries. California's Spanish-speaking community has resided there sin ...

s, under the leadership of José María Flores

General José María Flores was a Captain in the Mexican Army and was a member of ''la otra banda''. He was appointed Governor and ''Comandante General'' ''pro tem'' of Alta California from November 1846 to January 1847, and defended California ...

, forced the small American garrison to retire to the harbor.

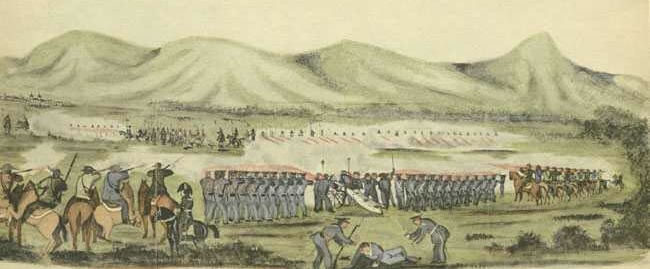

Soon afterward, 200 reinforcements sent by Stockton and led by U.S. Navy Captain William Mervine were repulsed on October 8 in the one-hour Battle of Dominguez Rancho on

Soon afterward, 200 reinforcements sent by Stockton and led by U.S. Navy Captain William Mervine were repulsed on October 8 in the one-hour Battle of Dominguez Rancho on Rancho San Pedro

Rancho San Pedro was one of the first California land grants and the first to win a patent from the United States. The Spanish Crown granted the of land to soldier Juan José Domínguez in 1784, with his descendants validating their legal clai ...

, with four Americans killed. In late November, General Stephen W. Kearny

Stephen Watts Kearny (sometimes spelled Kearney) ( ) (August 30, 1794October 31, 1848) was one of the foremost antebellum frontier officers of the United States Army. He is remembered for his significant contributions in the Mexican–American Wa ...

, with a squadron of 100 dragoons, finally reached the Colorado River

The Colorado River ( es, Río Colorado) is one of the principal rivers (along with the Rio Grande) in the Southwestern United States and northern Mexico. The river drains an expansive, arid watershed that encompasses parts of seven U.S. s ...

at the present-day California border after a grueling march across the province of Santa Fe de Nuevo México

Santa Fe de Nuevo México ( en, Holy Faith of New Mexico; shortened as Nuevo México or Nuevo Méjico, and translated as New Mexico in English) was a Kingdom of the Spanish Empire and New Spain, and later a territory (geographic region), territ ...

and the Sonoran Desert

The Sonoran Desert ( es, Desierto de Sonora) is a desert in North America and ecoregion that covers the northwestern Mexican states of Sonora, Baja California, and Baja California Sur, as well as part of the southwestern United States (in Ariz ...

. Then, on December 6, they fought the botched half-hour Battle of San Pasqual

The Battle of San Pasqual, also spelled San Pascual, was a military encounter that occurred during the Mexican–American War in what is now the San Pasqual Valley community of the city of San Diego, California. The series of military skirmishes ...

Walker p. 215-219 east of San Diego pueblo, where 21 of Kearny's troops were killed, the largest number of American casualties in the battles of the California Campaign.

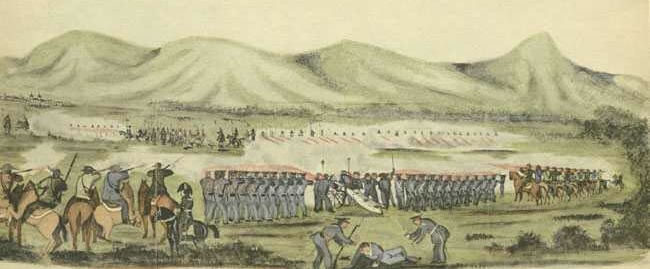

Final conquest

Stockton rescued Kearny's surrounded forces and, with their combined force totaling 660 troops, they moved northward fromSan Diego

San Diego ( , ; ) is a city on the Pacific Ocean coast of Southern California located immediately adjacent to the Mexico–United States border. With a 2020 population of 1,386,932, it is the eighth most populous city in the United States ...

, entering the Los Angeles Basin

The Los Angeles Basin is a sedimentary basin located in Southern California, in a region known as the Peninsular Ranges. The basin is also connected to an anomalous group of east-west trending chains of mountains collectively known as the ...

on January 8, 1847. On that day they fought the Californios in the Battle of Rio San Gabriel and the next day in the Battle of La Mesa. The last significant body of Californios surrendered to American forces on January 12, marking the end of the war in Alta California.

Aftermath

Treaty of Cahuenga

TheTreaty of Cahuenga

The Treaty of Cahuenga ( es, Tratado de Cahuenga), also called the Capitulation of Cahuenga (''Capitulación de Cahuenga''), was an 1847 agreement that ended the Conquest of California, resulting in a ceasefire between Californios and Americans. T ...

was signed on January 13, 1847, and essentially terminated hostilities in Alta California. The treaty was drafted in English and Spanish by José Antonio Carrillo and approved by American Brigadier General John C. Frémont

John Charles Frémont or Fremont (January 21, 1813July 13, 1890) was an American explorer, military officer, and politician. He was a U.S. Senator from California and was the first Republican nominee for president of the United States in 1856 ...

and Californio General Andrés Pico

Andrés Pico (November 18, 1810 – February 14, 1876) was a Californio who became a successful rancher, fought in the contested Battle of San Pascual during the Mexican–American War, and negotiated promises of post-war protections for Calif ...

at Campo de Cahuenga

The Campo de Cahuenga, () near the historic Cahuenga Pass in present-day Studio City, California, was an adobe ranch house on the Rancho Cahuenga where the Treaty of Cahuenga was signed between Lieutenant Colonel John C. Frémont and General An ...

in the Cahuenga Pass of Los Angeles. It was later ratified by Frémont's superiors, Commodore Robert F. Stockton

Robert Field Stockton (August 20, 1795 – October 7, 1866) was a United States Navy commodore, notable in the capture of California during the Mexican–American War. He was a naval innovator and an early advocate for a propeller-driven, steam- ...

and General Stephen Kearny

Stephen Watts Kearny (sometimes spelled Kearney) ( ) (August 30, 1794October 31, 1848) was one of the foremost antebellum frontier officers of the United States Army. He is remembered for his significant contributions in the Mexican–American Wa ...

(brevet rank).

Pacific Coast Campaign

In July 1846, Colonel

In July 1846, Colonel Jonathan D. Stevenson

Jonathan Drake Stevenson (1800–1894) was born in New York; won a seat in the New York State Assembly; was the commanding officer of the First Regiment of New York Volunteers during the Mexican–American War in California; entered California mi ...

of New York was asked to raise a volunteer regiment of ten companies of 77 men each to go to California with the understanding that they would muster out and stay in California. They were designated the 1st Regiment of New York Volunteers 1st Regiment of New York Volunteers, for service in California and during the war with Mexico, was raised in 1846 during the Mexican–American War by Jonathan D. Stevenson. Accepted by the United States Army on August 1846, the 1st Regiment of New ...

and took part in the Pacific Coast Campaign

The Pacific Ocean is the largest and deepest of Earth's five oceanic divisions. It extends from the Arctic Ocean in the north to the Southern Ocean (or, depending on definition, to Antarctica) in the south, and is bounded by the continen ...

. In August and September 1846 the regiment trained and prepared for the trip to California.

Three private merchant ships, ''Thomas H Perkins'', ''Loo Choo'', and ''Susan Drew'', were chartered, and the sloop was assigned convoy detail. On September 26 the four ships sailed for California. Fifty men who had been left behind for various reasons sailed on November 13, 1846 on the small storeship USS ''Brutus''. The ''Susan Drew'' and ''Loo Choo'' reached Valparaíso

Valparaíso (; ) is a major city, seaport, naval base, and educational centre in the commune of Valparaíso, Chile. "Greater Valparaíso" is the second largest metropolitan area in the country. Valparaíso is located about northwest of Santiago ...

, Chile by January 20, 1847 and they were on their way again by January 23. The ''Perkins'' did not stop until San Francisco, reaching port on March 6, 1847. The ''Susan Drew'' arrived on March 20 and the ''Loo Choo'' arrived on March 26, 1847, 183 days after leaving New York. The ''Brutus'' finally arrived on April 17.

After desertions and deaths in transit the four ships brought 648 men to California. The companies were then deployed throughout Upper Alta California and Lower Baja California on the Baja California Peninsula (captured by the Navy and later returned to Mexico), from San Francisco to

After desertions and deaths in transit the four ships brought 648 men to California. The companies were then deployed throughout Upper Alta California and Lower Baja California on the Baja California Peninsula (captured by the Navy and later returned to Mexico), from San Francisco to La Paz

La Paz (), officially known as Nuestra Señora de La Paz (Spanish pronunciation: ), is the seat of government of the Plurinational State of Bolivia. With an estimated 816,044 residents as of 2020, La Paz is the third-most populous city in Bol ...

. The ship ''Isabella '' sailed from Philadelphia

Philadelphia, often called Philly, is the largest city in the Commonwealth of Pennsylvania, the sixth-largest city in the U.S., the second-largest city in both the Northeast megalopolis and Mid-Atlantic regions after New York City. Since ...

on August 16, 1846, with a detachment of one hundred soldiers, and arrived in California on February 18, 1847 at about the same time that the ship ''Sweden'' arrived with another detachment of soldiers. These soldiers were added to the existing companies of Stevenson's 1st New York Volunteer Regiment. These troops essentially took over nearly all of the Pacific Squadron's onshore military and garrison

A garrison (from the French ''garnison'', itself from the verb ''garnir'', "to equip") is any body of troops stationed in a particular location, originally to guard it. The term now often applies to certain facilities that constitute a mili ...

duties and the California Battalion

The California Battalion (also called the first California Volunteer Militia and U.S. Mounted Rifles) was formed during the Mexican–American War (1846–1848) in present-day California, United States. It was led by U.S. Army Brevet Lieutenant C ...

's garrison duties.

In January 1847, Lieutenant William Tecumseh Sherman

William Tecumseh Sherman ( ; February 8, 1820February 14, 1891) was an American soldier, businessman, educator, and author. He served as a general in the Union Army during the American Civil War (1861–1865), achieving recognition for his com ...

and about 100 regular U.S. Army soldiers arrived in Monterey. American forces in the pipeline continued to dribble into California.

;Mormon Battalion

The

;Mormon Battalion

The Mormon Battalion

The Mormon Battalion was the only religious unit in United States military history in federal service, recruited solely from one religious body and having a religious title as the unit designation. The volunteers served from July 1846 to July ...

served from July 1846 to July 1847 during the Mexican–American War. The battalion was a volunteer unit of between 534 and 559 Latter-day Saints men, who were led by Mormon company officers and commanded by regular United States Army

The United States Army (USA) is the land service branch of the United States Armed Forces. It is one of the eight U.S. uniformed services, and is designated as the Army of the United States in the U.S. Constitution.Article II, section 2, ...

senior officers. During its service, the battalion made a grueling march of some 1,900 miles from Council Bluffs, Iowa

Council Bluffs is a city in and the county seat of Pottawattamie County, Iowa, United States. The city is the most populous in Southwest Iowa, and is the third largest and a primary city of the Omaha-Council Bluffs Metropolitan Area. It is loc ...

to San Diego

San Diego ( , ; ) is a city on the Pacific Ocean coast of Southern California located immediately adjacent to the Mexico–United States border. With a 2020 population of 1,386,932, it is the eighth most populous city in the United States ...

. This remains one of the longest single military marches in U.S. history.

The Mormon Battalion arrived in San Diego on January 29, 1847. For the next five months until their discharge on July 16, 1847 in Los Angeles

Los Angeles ( ; es, Los Ángeles, link=no , ), often referred to by its initials L.A., is the largest city in the state of California and the second most populous city in the United States after New York City, as well as one of the world ...

, the battalion trained and did garrison duties in several locations in southern California

Southern California (commonly shortened to SoCal) is a geographic and cultural region that generally comprises the southern portion of the U.S. state of California. It includes the Los Angeles metropolitan area, the second most populous urban ...

. Discharged members of the Mormon Battalion were helping to build a sawmill for John Sutter when gold was discovered there in January 1848, starting the California Gold Rush

The California Gold Rush (1848–1855) was a gold rush that began on January 24, 1848, when gold was found by James W. Marshall at Sutter's Mill in Coloma, California. The news of gold brought approximately 300,000 people to California f ...

.

Treaty of Guadalupe Hidalgo

TheTreaty of Guadalupe Hidalgo

The Treaty of Guadalupe Hidalgo ( es, Tratado de Guadalupe Hidalgo), officially the Treaty of Peace, Friendship, Limits, and Settlement between the United States of America and the United Mexican States, is the peace treaty that was signed on 2 ...

, signed in February 1848, marked the end of the Mexican–American War. By the terms of the treaty, Mexico formally ceded Alta California along with its other northern territories east through Texas

Texas (, ; Spanish: ''Texas'', ''Tejas'') is a state in the South Central region of the United States. At 268,596 square miles (695,662 km2), and with more than 29.1 million residents in 2020, it is the second-largest U.S. state by ...

, receiving $15,000,000 in exchange. This largely unsettled territory constituted nearly half of its claimed territory with about 1% of its then population of about 4,500,000.

California Genocide

The conquest and California officially becoming part of the United States set off a genocide against theindigenous peoples of California

The indigenous peoples of California (known as Native Californians) are the indigenous inhabitants who have lived or currently live in the geographic area within the current boundaries of California before and after the arrival of Europeans. ...

. The United States federal government and the newly created state government of California incited, aided, and financed the violence against the Native Americans, including massacres, cultural genocide, and forced enslavement. On January 6, 1851, at his State of the State address to the California Senate, the first Governor Peter Burnett

Peter Hardeman Burnett (November 15, 1807May 17, 1895) was an American politician who served as the first elected Governor of California from December 20, 1849, to January 9, 1851. Burnett was elected Governor almost one year before California's ...

said: "That a war of extermination will continue to be waged between the races until the Indian race becomes extinct must be expected. While we cannot anticipate this result but with painful regret, the inevitable destiny of the race is beyond the power or wisdom of man to avert." Between 1846 and 1873, it is estimated that non-Natives killed between 9,492 and 16,094 California Natives. Hundreds to thousands were additionally starved or worked to death. Acts of enslavement, kidnapping, rape, child separation and displacement were widespread. These acts were encouraged, tolerated, and carried out by state authorities and militias.

Timeline of events

See also

* Conquest of California topics * Mexican California topics *Mexican–American War

The Mexican–American War, also known in the United States as the Mexican War and in Mexico as the (''United States intervention in Mexico''), was an armed conflict between the United States and Mexico from 1846 to 1848. It followed the ...

** Pacific Coast Campaign

The Pacific Ocean is the largest and deepest of Earth's five oceanic divisions. It extends from the Arctic Ocean in the north to the Southern Ocean (or, depending on definition, to Antarctica) in the south, and is bounded by the continen ...

* History of California through 1899

Human history in California began when Indigenous peoples of the Americas, indigenous Americans first arrived some 13,000 years ago. Coastal exploration by the Spanish began in the 16th century, with further European colonization of the Americas ...

* Indigenous peoples of California

The indigenous peoples of California (known as Native Californians) are the indigenous inhabitants who have lived or currently live in the geographic area within the current boundaries of California before and after the arrival of Europeans. ...

Notes

Further reading

*Downey, Joseph, T., Ordinary Seaman, USN; Edited by Lamar, Howard. (1963-Reissued). ''The Cruise of thePortsmouth

Portsmouth ( ) is a port and city in the ceremonial county of Hampshire in southern England. The city of Portsmouth has been a unitary authority since 1 April 1997 and is administered by Portsmouth City Council.

Portsmouth is the most d ...

, 1845-1847, A Sailor's View of the Naval Conquest of California

The Conquest of California, also known as the Conquest of Alta California or the California Campaign, was an important military campaign of the Mexican–American War carried out by the United States in Alta California (modern-day California), t ...

.'' Yale University Press.

Hubert Howe Bancroft. ''The Works of Hubert Howe Bancroft,''

vol 22 (1886), ''History of California'' 1846–48; complete text online; famous, highly detailed narrative written in the 1880s. Also a

* * Harlow, Neal ''California Conquered: The Annexation of a Mexican Province 1846–1850'', , (1982) * Hittell, Theodore Henry. ''History of California'' vol 2 (1885

online

* Nevins, Allan. ''Fremont: Pathmarker of the West, Volume 1: Fremont the Explorer'' (1939, rev ed. 1955) * Rawls, James and Walton Bean. ''California: An Interpretive History'' (8th ed 2003), college textbook; the latest version of Bean's solid 1968 text

External links

A Continent Divided: The U.S. – Mexico War

– ''from the Center for Greater Southwestern Studies, the University of Texas at Arlington''.

Map of Mexico and the United States during the California Campaign at omniatlas.com

{{Authority control Mexican California

California

California is a state in the Western United States, located along the Pacific Coast. With nearly 39.2million residents across a total area of approximately , it is the most populous U.S. state and the 3rd largest by area. It is also the m ...

1846 in the Mexican-American War

1847 in the Mexican-American War

Military history of California

Pre-statehood history of California

California

California is a state in the Western United States, located along the Pacific Coast. With nearly 39.2million residents across a total area of approximately , it is the most populous U.S. state and the 3rd largest by area. It is also the m ...

1846 in Alta California

1847 in Alta California

California

California is a state in the Western United States, located along the Pacific Coast. With nearly 39.2million residents across a total area of approximately , it is the most populous U.S. state and the 3rd largest by area. It is also the m ...