Composition of the Torah on:

[Wikipedia]

[Google]

[Amazon]

The composition of the Torah (or Pentateuch, the first five books of the Bible:

Chapter 40.3-8

/ref> Scholars have traditionally attributed the passage to the late 4th-century Greek historian

In the mid-18th century, some scholars started a critical study of doublets (parallel accounts of the same incidents), inconsistencies, and changes in style and vocabulary in the Torah. In 1780 Johann Eichhorn, building on the work of the French doctor and

In the mid-18th century, some scholars started a critical study of doublets (parallel accounts of the same incidents), inconsistencies, and changes in style and vocabulary in the Torah. In 1780 Johann Eichhorn, building on the work of the French doctor and

Genesis

Genesis may refer to:

Bible

* Book of Genesis, the first book of the biblical scriptures of both Judaism and Christianity, describing the creation of the Earth and of mankind

* Genesis creation narrative, the first several chapters of the Book of ...

, Exodus

Exodus or the Exodus may refer to:

Religion

* Book of Exodus, second book of the Hebrew Torah and the Christian Bible

* The Exodus, the biblical story of the migration of the ancient Israelites from Egypt into Canaan

Historical events

* E ...

, Leviticus, Numbers

A number is a mathematical object used to count, measure, and label. The original examples are the natural numbers 1, 2, 3, 4, and so forth. Numbers can be represented in language with number words. More universally, individual numbers can ...

, and Deuteronomy

Deuteronomy ( grc, Δευτερονόμιον, Deuteronómion, second law) is the fifth and last book of the Torah (in Judaism), where it is called (Hebrew: hbo, , Dəḇārīm, hewords Moses.html"_;"title="f_Moses">f_Moseslabel=none)_and_th ...

) was a process that involved multiple authors over an extended period of time. While Jewish tradition

Jews ( he, יְהוּדִים, , ) or Jewish people are an ethnoreligious group and nation originating from the Israelites Israelite origins and kingdom: "The first act in the long drama of Jewish history is the age of the Israelites"" ...

holds that all five books were originally written by Moses sometime in the 2nd millennium BCE, leading scholars have rejected Mosaic authorship

Mosaic authorship is the Judeo-Christian tradition that the Torah, the first five books of the Hebrew Bible/Old Testament, were dictated by God to Moses. The tradition probably began with the legalistic code of the Book of Deuteronomy and was t ...

since the 17th century.

The precise process by which the Torah

The Torah (; hbo, ''Tōrā'', "Instruction", "Teaching" or "Law") is the compilation of the first five books of the Hebrew Bible, namely the books of Genesis, Exodus, Leviticus, Numbers and Deuteronomy. In that sense, Torah means the ...

was composed, the number of authors involved, and the date of each author remain hotly contested among scholars. Some scholars, such as Rolf Rendtorff

Rolf Rendtorff (10 May 1925 – 1 April 2014) was Emeritus Professor of Old Testament at the University of Heidelberg. He has written frequently on the Jewish scriptures and was notable chiefly for his contribution to the debate over the origins o ...

, espouse a fragmentary hypothesis, in which the Pentateuch is seen as a compilation of short, independent narratives, which were gradually brought together into larger units in two editorial phases: the Deuteronomic

Deuteronomy ( grc, Δευτερονόμιον, Deuteronómion, second law) is the fifth and last book of the Torah (in Judaism), where it is called (Hebrew: hbo, , Dəḇārīm, hewords Moses.html"_;"title="f_Moses">f_Moseslabel=none)_and_ ...

and the Priestly phases. By contrast, scholars such as John Van Seters

John Van Seters (born May 2, 1935 in Hamilton, Ontario) is a Canadian scholar of the Hebrew Bible (Old Testament) and the Ancient Near East. Currently University Distinguished Professor Emeritus at the University of North Carolina, he was formerly ...

advocate a supplementary hypothesis

In biblical studies, the supplementary hypothesis proposes that the Pentateuch (the first five books of the Bible) was derived from a series of direct additions to an existing corpus of work. It serves as a revision to the earlier documentary hy ...

, which posits that the Torah is the result of two major additions—Yahwist

The Jahwist, or Yahwist, often abbreviated J, is one of the most widely recognized sources of the Pentateuch (Torah), together with the Deuteronomist, the Priestly source and the Elohist. The existence of the Jahwist is somewhat controversial, ...

and Priestly—to an existing corpus of work. Other scholars, such as Richard Elliott Friedman

Richard Elliott Friedman (born May 5, 1946) is a biblical scholar and the Ann and Jay Davis Professor of Jewish Studies at the University of Georgia.

Friedman was born in Rochester, New York. He attended the University of Miami (BA, 1968), the Je ...

or Joel S. Baden, support a revised version of the documentary hypothesis

The documentary hypothesis (DH) is one of the models used by biblical scholars to explain the origins and composition of the Torah (or Pentateuch, the first five books of the Bible: Genesis, Exodus, Leviticus, Numbers, and Deuteronomy). A ver ...

, holding that the Torah was composed by using four different sources—Yahwist, Elohist, Priestly and Deuteronomist—that were combined into one in the Persian period.

Scholars frequently use these newer hypotheses in combination with each other, making it difficult to classify contemporary theories as strictly one or another. The general trend in recent scholarship is to recognize the final form of the Torah as a literary and ideological unity, based on earlier sources, likely completed during the Persian period (539-333 BCE).

Date of composition

Classicalsource criticism

Source criticism (or information evaluation) is the process of evaluating an information source, i.e.: a document, a person, a speech, a fingerprint, a photo, an observation, or anything used in order to obtain knowledge. In relation to a given p ...

seeks to determine the date of a text by establishing an upper limit (''terminus ante quem'') and a lower limit (''terminus post quem

''Terminus post quem'' ("limit after which", sometimes abbreviated to TPQ) and ''terminus ante quem'' ("limit before which", abbreviated to TAQ) specify the known limits of dating for events or items..

A ''terminus post quem'' is the earliest da ...

'') on the basis of external attestation of the text's existence, as well as the internal features of the text itself. On the basis of a variety of arguments, modern scholars generally see the completed Torah

The Torah (; hbo, ''Tōrā'', "Instruction", "Teaching" or "Law") is the compilation of the first five books of the Hebrew Bible, namely the books of Genesis, Exodus, Leviticus, Numbers and Deuteronomy. In that sense, Torah means the ...

as a product of the time of the Persian Achaemenid Empire

The Achaemenid Empire or Achaemenian Empire (; peo, 𐎧𐏁𐏂, , ), also called the First Persian Empire, was an ancient Iranian empire founded by Cyrus the Great in 550 BC. Based in Western Asia, it was contemporarily the largest em ...

(probably 450–350 BCE), although some would place its composition in the Hellenistic period

In Classical antiquity, the Hellenistic period covers the time in Mediterranean history after Classical Greece, between the death of Alexander the Great in 323 BC and the emergence of the Roman Empire, as signified by the Battle of Actium in ...

(333–164 BCE).

External evidence

The absence of archaeological evidence forthe Exodus

The Exodus (Hebrew: יציאת מצרים, ''Yeẓi’at Miẓrayim'': ) is the founding myth of the Israelites whose narrative is spread over four books of the Torah (or Pentateuch, corresponding to the first five books of the Bible), namely E ...

narrative, and the evidence pointing to anachronisms in the patriarchal narratives of Abraham

Abraham, ; ar, , , name=, group= (originally Abram) is the common Hebrew patriarch of the Abrahamic religions, including Judaism, Christianity, and Islam. In Judaism, he is the founding father of the special relationship between the Je ...

, Isaac

Isaac; grc, Ἰσαάκ, Isaák; ar, إسحٰق/إسحاق, Isḥāq; am, ይስሐቅ is one of the three patriarchs of the Israelites and an important figure in the Abrahamic religions, including Judaism, Christianity, and Islam. He was ...

, and Jacob

Jacob (; ; ar, يَعْقُوب, Yaʿqūb; gr, Ἰακώβ, Iakṓb), later given the name Israel, is regarded as a patriarch of the Israelites and is an important figure in Abrahamic religions, such as Judaism, Christianity, and Islam. ...

, have convinced the vast majority of scholars that the Torah does not give an accurate account of the origins of Israel. This implies that the Torah could not have been written by Moses during the second millennium BCE, as Jewish tradition teaches.

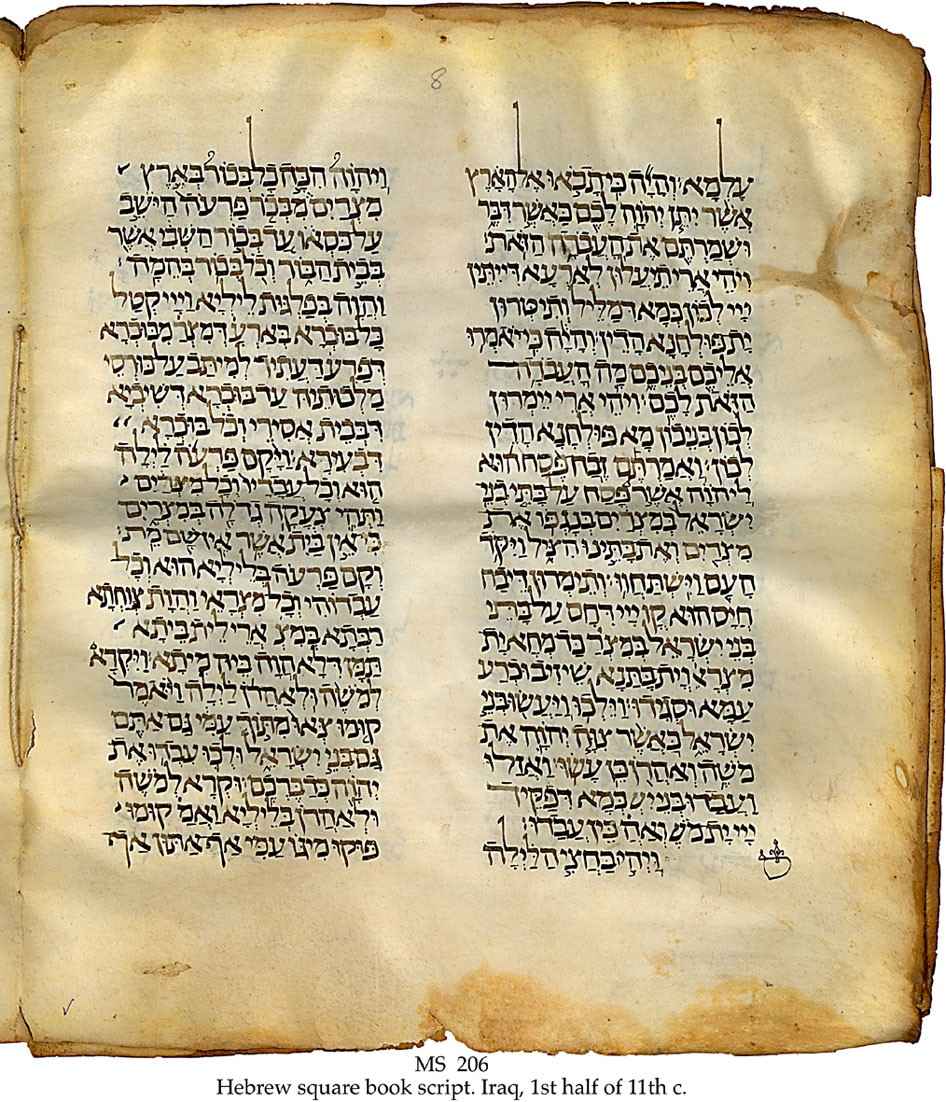

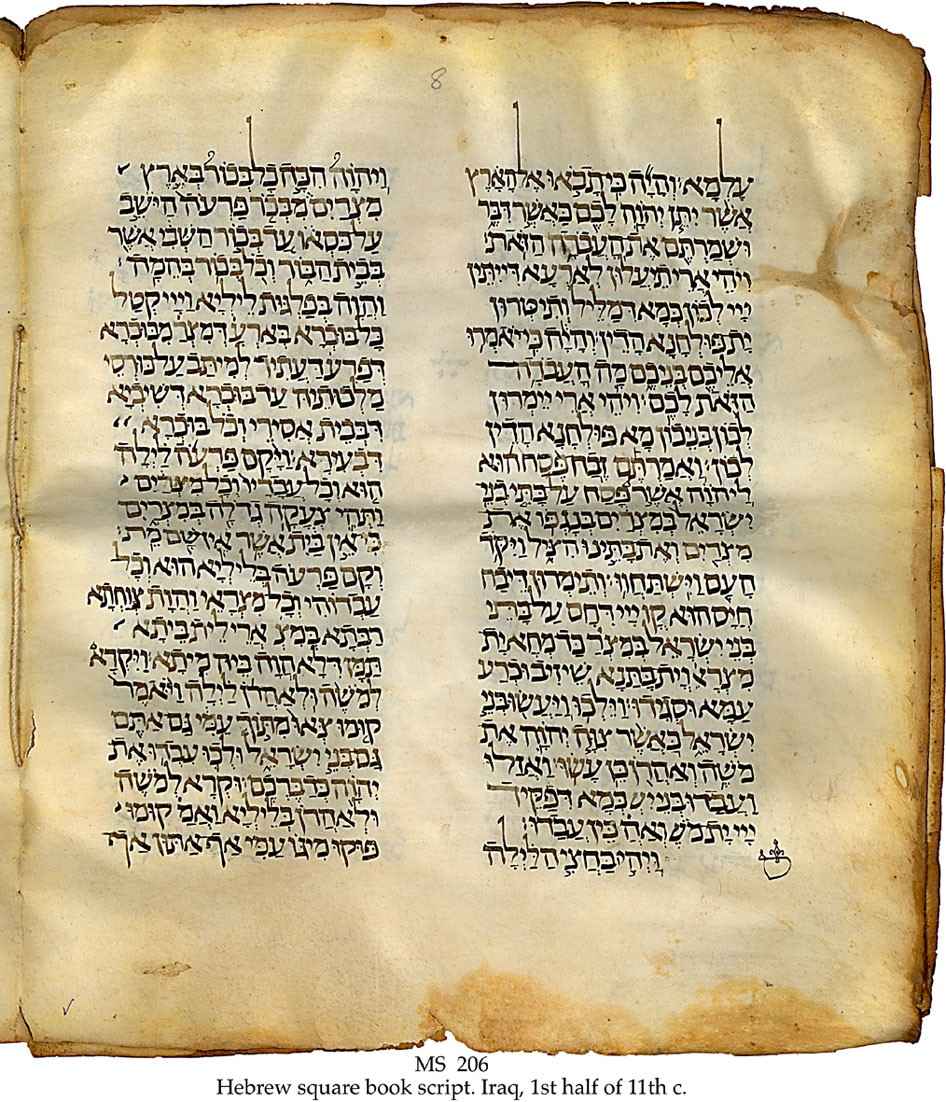

Manuscripts and non-biblical references

Concrete archaeological evidence bearing on the dating of the Torah is found in early manuscript fragments, such as those found among theDead Sea Scrolls

The Dead Sea Scrolls (also the Qumran Caves Scrolls) are ancient Jewish and Hebrew religious manuscripts discovered between 1946 and 1956 at the Qumran Caves in what was then Mandatory Palestine, near Ein Feshkha in the West Bank, on the ...

. The earliest extant manuscript fragments of the Pentateuch date to the late third or early second centuries BCE. In addition, early non-biblical sources, such as the Letter of Aristeas

The Letter of Aristeas to Philocrates is a Hellenistic work of the 3rd or early 2nd century BC, considered by some Biblical scholars to be pseudepigraphical. Harris, Stephen L., ''Understanding the Bible''. (Palo Alto: Mayfield) 1985; André Pel ...

, indicate that the Torah was first translated into Greek in Alexandria

Alexandria ( or ; ar, ٱلْإِسْكَنْدَرِيَّةُ ; grc-gre, Αλεξάνδρεια, Alexándria) is the second largest city in Egypt, and the largest city on the Mediterranean coast. Founded in by Alexander the Great, Alexandri ...

under the reign of Ptolemy II Philadelphus

; egy, Userkanaenre Meryamun Clayton (2006) p. 208

, predecessor = Ptolemy I

, successor = Ptolemy III

, horus = ''ḥwnw-ḳni'Khunuqeni''The brave youth

, nebty = ''wr-pḥtj'Urpekhti''Great of strength

, gold ...

(285–247 BCE). These lines of evidence indicate that the Torah must have been composed in its final form no later than c. 250 BCE, before its translation into Greek.

There is one external reference to the Torah which, depending on its attribution, may push the ''terminus ante quem'' for the composition of the Torah down to about 315 BCE. In Book 40 of Diodorus Siculus

Diodorus Siculus, or Diodorus of Sicily ( grc-gre, Διόδωρος ; 1st century BC), was an ancient Greek historian. He is known for writing the monumental universal history '' Bibliotheca historica'', in forty books, fifteen of which ...

's ''Library

A library is a collection of materials, books or media that are accessible for use and not just for display purposes. A library provides physical (hard copies) or digital access (soft copies) materials, and may be a physical location or a vi ...

'', an ancient encyclopedia compiled from a variety of quotations from older documents, there is a passage that refers to a written Jewish law passed down from Moses.Diodorus Siculus

Diodorus Siculus, or Diodorus of Sicily ( grc-gre, Διόδωρος ; 1st century BC), was an ancient Greek historian. He is known for writing the monumental universal history '' Bibliotheca historica'', in forty books, fifteen of which ...

''Library''Chapter 40.3-8

/ref> Scholars have traditionally attributed the passage to the late 4th-century Greek historian

Hecataeus of Abdera :''See Hecataeus of Miletus for the earlier historian.''

Hecataeus of Abdera or of Teos ( el, Ἑκαταῖος ὁ Ἀβδηρίτης), was a Greek historian and Pyrrhonist philosopher who flourished in the 4th century BC.

Life

Diogenes La� ...

, which, if correct, would imply that the Torah must have been composed in some form before 315 BCE. However, the attribution of this passage to Hecataeus has been challenged recently. Russell Gmirkin has argued that the passage is in fact a quote from Theophanes of Mytilene

Theophanes of Mytilene ( grc-gre, Θεοφάνης ὁ Μυτιληναῖος) was an intellectual and historian from the town of Mytilene on the island of Lesbos who lived in the middle of the 1st century BC. He was a friend of Pompey and wrot ...

, a first-century BCE Roman biographer cited earlier in Book 40, who in turn used Hecataeus along with other sources.

Elephantine papyri

TheElephantine papyri

The Elephantine Papyri and Ostraca consist of thousands of documents from the Egyptian border fortresses of Elephantine and Aswan, which yielded hundreds of papyri and ostraca in hieratic and demotic Egyptian, Aramaic, Koine Greek, Latin and Co ...

show clear evidence of the existence c. 400 BCE of a polytheistic

Polytheism is the belief in multiple deities, which are usually assembled into a pantheon of gods and goddesses, along with their own religious sects and rituals. Polytheism is a type of theism. Within theism, it contrasts with monotheism, the ...

Jewish colony in Egypt who show no knowledge of a written Torah or the narratives described therein. The papyri also document the existence of a small Jewish temple at Elephantine

Elephantine ( ; ; arz, جزيرة الفنتين; el, Ἐλεφαντίνη ''Elephantíne''; , ) is an island on the Nile, forming part of the city of Aswan in Upper Egypt. The archaeological sites on the island were inscribed on the UNESCO ...

, which possessed altars for incense offerings and animal sacrifices, as late as 411 BCE. Such a temple would be in clear violation of Deuteronomic

Deuteronomy ( grc, Δευτερονόμιον, Deuteronómion, second law) is the fifth and last book of the Torah (in Judaism), where it is called (Hebrew: hbo, , Dəḇārīm, hewords Moses.html"_;"title="f_Moses">f_Moseslabel=none)_and_ ...

law, which stipulates that no Jewish temple may be constructed outside of Jerusalem. Furthermore, the papyri show that the Jews at Elephantine sent letters to the high priest in Jerusalem asking for his support in re-building their temple, which seems to suggest that the priests of the Jerusalem Temple were not enforcing Deuteronomic law at that time.

A minority of scholars such as Niels Peter Lemche

Niels Peter Lemche (born 6 September 1945) is a biblical scholar at the University of Copenhagen, whose interests include early Israel and its relationship with history, the Old Testament, and archaeology.

Career

In 1971 Lemche received his underg ...

, Philippe Wajdenbaum, Russell Gmirkin, and Thomas L. Thompson

Thomas L. Thompson (born January 7, 1939 in Detroit, Michigan) is an American-born Danish biblical scholar and theologian. He was professor of theology at the University of Copenhagen from 1993 to 2009. He currently lives in Denmark.

Thompson is ...

have argued that the Elephantine papyri demonstrate that monotheism and the Torah could not have been established in Jewish culture before 400 BCE, and that the Torah was therefore likely written in the Hellenistic period

In Classical antiquity, the Hellenistic period covers the time in Mediterranean history after Classical Greece, between the death of Alexander the Great in 323 BC and the emergence of the Roman Empire, as signified by the Battle of Actium in ...

, in the third or fourth centuries BCE (see ). By contrast, most scholars explain this data by theorizing that the Elephantine Jews represented an isolated remnant of Jewish religious practices from earlier centuries, or that the Torah had only recently been promulgated at that time.

Ketef Hinnom scrolls

In 1979, two silver scrolls were uncovered at Ketef Hinnom, an archaeological site southwest of the Old City ofJerusalem

Jerusalem (; he, יְרוּשָׁלַיִם ; ar, القُدس ) (combining the Biblical and common usage Arabic names); grc, Ἱερουσαλήμ/Ἰεροσόλυμα, Hierousalḗm/Hierosóluma; hy, Երուսաղեմ, Erusałēm. i ...

, which were found to contain a variation of the Priestly Blessing

The Priestly Blessing or priestly benediction, ( he, ברכת כהנים; translit. ''birkat kohanim''), also known in rabbinic literature as raising of the hands (Hebrew ''nesiat kapayim'') or rising to the platform (Hebrew ''aliyah ledukhan'') ...

, found in . The scrolls were dated paleographically to the late 7th or early 6th century BCE, placing them at the end of the First Temple

Solomon's Temple, also known as the First Temple (, , ), was the Temple in Jerusalem between the 10th century BC and . According to the Hebrew Bible, it was commissioned by Solomon in the United Kingdom of Israel before being inherited by th ...

period. These scrolls cannot be accepted as evidence that the Pentateuch as a whole was composed before the 6th century, however, because it is widely accepted that the Torah draws on earlier oral and written sources, and there is no reference to a written Torah in the scrolls themselves.

Linguistic dating

Some scholars, such as Avi Hurvitz (see below), have attempted to date the various strata of the Pentateuch on the basis of the form of theHebrew language

Hebrew (; ; ) is a Northwest Semitic language of the Afroasiatic language family. Historically, it is one of the spoken languages of the Israelites and their longest-surviving descendants, the Jews and Samaritans. It was largely preserve ...

that is used. It is generally agreed that Classical Hebrew and Late Biblical Hebrew had distinctive, identifiable features and that Classical Hebrew was earlier. Classical Hebrew is usually dated to the period before the Babylonian captivity

The Babylonian captivity or Babylonian exile is the period in Jewish history during which a large number of Judeans from the ancient Kingdom of Judah were captives in Babylon, the capital city of the Neo-Babylonian Empire, following their defeat ...

(597-539 BCE), while Late Biblical Hebrew is generally dated to the exilic and post-exilic periods. However, it is difficult to determine precisely when Classical Hebrew ceased being used, since there are no extant Hebrew inscriptions of substantial length dating from the relevant period (c. 550-200 BCE). Scholars also disagree about the variety of Hebrew to which the various strata should be assigned. For example, Hurvitz classifies the Priestly material as belonging to Classical Hebrew, while Joseph Blenkinsopp and most other scholars disagree.

Another methodological difficulty with linguistic dating is that it is known that the biblical authors often intentionally used archaisms for stylistic effects, sometimes mixing them with words and constructions from later periods. This means that the presence of archaic language in a text cannot be considered definitive proof that the text dates to an early period. Ian Young and Martin Ehrensvärd maintain that even some texts that were certainly written during the post-exilic period, such as the Book of Haggai

The Book of Haggai (; he, ספר חגי, Sefer Ḥaggay) is a book of the Hebrew Bible or Tanakh, and is the third-to-last of the Twelve Minor Prophets. It is a short book, consisting of only two chapters. The historical setting dates around 52 ...

, lack features distinctive of Late Biblical Hebrew. Conversely, the Book of Ezekiel

The Book of Ezekiel is the third of the Latter Prophets in the Tanakh and one of the major prophetic books, following Isaiah and Jeremiah. According to the book itself, it records six visions of the prophet Ezekiel, exiled in Babylon, during ...

, written during the Babylonian exile, contains many features of Late Biblical Hebrew. Summing up these problems, Young has argued that "none of the linguistic criteria used to date iblicaltexts either early or late is strong enough to compel scholars to reconsider an argument made on non-linguistic grounds." However, this position has been rejected by other scholars, such as Ronald Hendel and Jan Joosten, who criticize that Young and others exclusively use the Masoretic text

The Masoretic Text (MT or 𝕸; he, נֻסָּח הַמָּסוֹרָה, Nūssāḥ Hammāsōrā, lit. 'Text of the Tradition') is the authoritative Hebrew and Aramaic text of the 24 books of the Hebrew Bible (Tanakh) in Rabbinic Judaism. ...

of the Hebrew Bible to carry out their linguistic analysis of the biblical texts, apart from undertaking other errors in the fields of textual criticism

Textual criticism is a branch of textual scholarship, philology, and of literary criticism that is concerned with the identification of textual variants, or different versions, of either manuscripts or of printed books. Such texts may range in da ...

and historical linguistics

Historical linguistics, also termed diachronic linguistics, is the scientific study of language change over time. Principal concerns of historical linguistics include:

# to describe and account for observed changes in particular languages

# ...

.

For their part, Ronald Hendel and Jan Joosten hold that the Hebrew contained in the Genesis

Genesis may refer to:

Bible

* Book of Genesis, the first book of the biblical scriptures of both Judaism and Christianity, describing the creation of the Earth and of mankind

* Genesis creation narrative, the first several chapters of the Book of ...

-2 Kings

The Book of Kings (, '' Sēfer Məlāḵīm'') is a book in the Hebrew Bible, found as two books (1–2 Kings) in the Old Testament of the Christian Bible. It concludes the Deuteronomistic history, a history of Israel also including the book ...

saga corresponds to the Classical Hebrew of the pre-exilic period, which is supported by the linguistic correspondence with the Hebrew inscriptions of that period (mainly from the 8th and 7th centuries BC), so that they consequently date the composition of the main sources of the Torah to the period of Neo-Assyrian hegemony.

Historiographical dating

Many scholars assign dates to the Pentateuchal sources by comparing the theology and priorities of each author to a theoretical reconstruction of the history of Israelite religion. This method often involves provisionally accepting some narrative in the Hebrew Bible as attesting to a real historical event, and situating the composition of a source relative to that event. For example, the Deuteronomist source is widely associated with the staunchly monotheistic, centralizing religious reforms of King Josiah in the late 7th century BCE, as described in2 Kings

The Book of Kings (, '' Sēfer Məlāḵīm'') is a book in the Hebrew Bible, found as two books (1–2 Kings) in the Old Testament of the Christian Bible. It concludes the Deuteronomistic history, a history of Israel also including the book ...

. Starting with Julius Wellhausen

Julius Wellhausen (17 May 1844 – 7 January 1918) was a German biblical scholar and orientalist. In the course of his career, he moved from Old Testament research through Islamic studies to New Testament scholarship. Wellhausen contributed to t ...

, many scholars have identified the "Book of the Law" discovered by Josiah's high priest Hilkiah in with the Book of Deuteronomy

Deuteronomy ( grc, Δευτερονόμιον, Deuteronómion, second law) is the fifth and last book of the Torah (in Judaism), where it is called (Hebrew: hbo, , Dəḇārīm, hewords Moses.html"_;"title="f_Moses">f_Moseslabel=none)_and_ ...

, or an early version thereof, and posited that it was in fact ''written'' by Hilkiah at that time. Authors such as John Van Seters therefore date the D source to the late 7th century. Similarly, many scholars associate the Priestly source with the Book of the Law brought to Israel by Ezra

Ezra (; he, עֶזְרָא, '; fl. 480–440 BCE), also called Ezra the Scribe (, ') and Ezra the Priest in the Book of Ezra, was a Jewish scribe ('' sofer'') and priest ('' kohen''). In Greco-Latin Ezra is called Esdras ( grc-gre, Ἔσδρ ...

upon his return from exile in Babylonia in 458 BCE, as described in . P is therefore widely dated to the 5th century, during the Persian period.

This method has been criticized by some scholars, however, especially those associated with the minimalist school of biblical criticism. These critics stress that the historicity of the Josiah and Ezra narratives cannot be independently established outside the Hebrew Bible, and that archaeological evidence generally does not support the occurrence of a radical centralizing religious reform in the 7th century as described in 2 Kings. They conclude that dating Pentateuchal sources on the basis of historically dubious or uncertain events is inherently speculative and inadvisable.

Arguments for a Persian origin

In the influential book ''In Search of 'Ancient Israel': A Study in Biblical Origins'',Philip Davies

Philip Andrew Davies (born 5 January 1972) is a British politician who has served as the Member of Parliament (MP) for Shipley in West Yorkshire since the 2005 general election. A member of the Conservative Party, he is the most rebellious se ...

argued that the Torah was likely promulgated in its final form during the Persian period, when the Judean people were governed under the Yehud Medinata province of the Achaemenid Empire

The Achaemenid Empire or Achaemenian Empire (; peo, 𐎧𐏁𐏂, , ), also called the First Persian Empire, was an ancient Iranian empire founded by Cyrus the Great in 550 BC. Based in Western Asia, it was contemporarily the largest em ...

. Davies points out that the Persian empire had a general policy of establishing national law codes and consciously creating an ethnic identity among its conquered peoples in order to legitimate its rule, and concludes that this is the most likely historical context in which the Torah could have been published. Franz Greifenhagen concurs with this view, and notes that most recent studies support a Persian date for the final redaction of the Pentateuch. Since the Elephantine papyri seem to show that the Torah was not yet fully entrenched in Jewish culture by 400 BCE, Greifenhagen proposes that the late Persian period (450-350 BCE) is most likely.

Louis C. Jonker argues a connection between Darius I's DNb inscription and the Pentateuch, particularly the Holiness Legislation.

Possibility of a Hellenistic origin

The idea that the Torah may have been written during theHellenistic period

In Classical antiquity, the Hellenistic period covers the time in Mediterranean history after Classical Greece, between the death of Alexander the Great in 323 BC and the emergence of the Roman Empire, as signified by the Battle of Actium in ...

, after the conquests of Alexander the Great

Alexander III of Macedon ( grc, Ἀλέξανδρος, Alexandros; 20/21 July 356 BC – 10/11 June 323 BC), commonly known as Alexander the Great, was a king of the ancient Greek kingdom of Macedon. He succeeded his father Philip II to ...

, was first seriously proposed in 1993, when the biblical scholar Niels Peter Lemche

Niels Peter Lemche (born 6 September 1945) is a biblical scholar at the University of Copenhagen, whose interests include early Israel and its relationship with history, the Old Testament, and archaeology.

Career

In 1971 Lemche received his underg ...

published an article titled ''The Old Testament – A Hellenistic Book?'' Since then, a growing number of scholars, especially those associated with the Copenhagen School, have put forward various arguments for a Hellenistic origin of the Pentateuch.

Notably, in 2006, the independent scholar Russell Gmirkin published a book titled ''Berossus and Genesis, Manetho and Exodus'', in which he argued that the Pentateuch relied on the Greek-language histories of Berossus

Berossus () or Berosus (; grc, Βηρωσσος, Bērōssos; possibly derived from akk, , romanized: , "Bel is his shepherd") was a Hellenistic-era Babylonian writer, a priest of Bel Marduk and astronomer who wrote in the Koine Greek language ...

(278 BCE) and Manetho

Manetho (; grc-koi, Μανέθων ''Manéthōn'', ''gen''.: Μανέθωνος) is believed to have been an Egyptian priest from Sebennytos ( cop, Ϫⲉⲙⲛⲟⲩϯ, translit=Čemnouti) who lived in the Ptolemaic Kingdom in the early third ...

(285-280 BCE) and therefore must have been composed subsequently to both of them. Gmirkin further argued that the Torah was likely written at the Library of Alexandria

The Great Library of Alexandria in Alexandria, Egypt, was one of the largest and most significant libraries of the ancient world. The Library was part of a larger research institution called the Mouseion, which was dedicated to the Muses, t ...

in 273-272 BCE, by the same group of Jewish scholars who translated the Torah into Greek around the same time. While Gmirkin accepts the conventional stratification of the Pentateuch into sources such as J, D, and P, he believes that they are best understood as reflecting the different social strata and beliefs of the Alexandrian authors, rather than as independent writers separated by long periods of time.

In 2016, Gmirkin published a second book, ''Plato and the Creation of the Hebrew Bible'', in which he argued that the law code found in the Torah was heavily influenced by Greek laws, and especially the theoretical law code espoused by Plato

Plato ( ; grc-gre, Πλάτων ; 428/427 or 424/423 – 348/347 BC) was a Greek philosopher born in Athens during the Classical period in Ancient Greece. He founded the Platonist school of thought and the Academy, the first institution ...

in his ''Laws

Law is a set of rules that are created and are enforceable by social or governmental institutions to regulate behavior,Robertson, ''Crimes against humanity'', 90. with its precise definition a matter of longstanding debate. It has been vari ...

''. He further argued that Plato's ''Laws'' provided the biblical authors with a basic blueprint for how to transform Jewish society: by creating an authoritative canon of laws and associated literature, drawing on earlier traditions, and presenting them as being divinely inspired and very ancient. Philippe Wajdenbaum has recently argued for a similar conclusion.

Criticism of Hellenistic origin theories

John Van Seters criticized Gmirkin's work in a 2007 book review, arguing that ''Berossus and Genesis'' engages in astraw man fallacy

A straw man (sometimes written as strawman) is a form of argument and an informal fallacy of having the impression of refuting an argument, whereas the real subject of the argument was not addressed or refuted, but instead replaced with a false o ...

by attacking the documentary hypothesis without seriously addressing more recent theories of Pentateuchal origins. He also alleges that Gmirkin selectively points to parallels between Genesis and Berossus, and Exodus and Manetho, while ignoring major dissimilarities between the accounts. Finally, Van Seters points out that Gmirkin does not seriously consider the numerous allusions to the Genesis and Exodus narratives in the rest of the Hebrew Bible, including in texts that are generally dated much earlier than his proposed dating of the Pentateuch. Gmirkin, by contrast, holds that those parts of the Hebrew Bible that allude to Genesis and Exodus must be dated later than is commonly assumed.

Nature and extent of the sources

Virtually all scholars agree that the Torah is composed of material from multiple different authors, or sources. The three most commonly recognized are the Priestly (P), Deuteronomist (D), and Yahwist (J) sources.Priestly

The Priestly source is perhaps the most widely accepted source category in Pentateuchal studies, because it is both stylistically and theologically distinct from other material in the Torah. It includes a set of claims that are contradicted by non-Priestly passages and therefore uniquely characteristic: no sacrifice before the institution is ordained byYahweh

Yahweh *''Yahwe'', was the national god of ancient Israel and Judah. The origins of his worship reach at least to the early Iron Age, and likely to the Late Bronze Age if not somewhat earlier, and in the oldest biblical literature he po ...

(God) at Sinai, the exalted status of Aaron

According to Abrahamic religions, Aaron ''′aharon'', ar, هارون, Hārūn, Greek (Septuagint): Ἀαρών; often called Aaron the priest ()., group="note" ( or ; ''’Ahărōn'') was a prophet, a high priest, and the elder brother of ...

and the priesthood, and the use of the divine title El Shaddai

El Shaddai ( ''ʾĒl Šadday''; ) or just Shaddai is one of the names of the God of Israel. ''El Shaddai'' is conventionally translated into English as ''God Almighty'' (''Deus Omnipotens'' in Latin, الله عز وجل Allāh 'azzawajal in Ara ...

before God reveals his name to Moses

Moses hbo, מֹשֶׁה, Mōše; also known as Moshe or Moshe Rabbeinu ( Mishnaic Hebrew: מֹשֶׁה רַבֵּינוּ, ); syr, ܡܘܫܐ, Mūše; ar, موسى, Mūsā; grc, Mωϋσῆς, Mōÿsēs () is considered the most important pr ...

, to name a few. In general, the Priestly work is concerned with priestly matters—ritual law, the origins of shrines and rituals, and genealogies—all expressed in a formal, repetitive style. It stresses the rules and rituals of worship, and the crucial role of priests, expanding considerably on the role given to Aaron

According to Abrahamic religions, Aaron ''′aharon'', ar, هارون, Hārūn, Greek (Septuagint): Ἀαρών; often called Aaron the priest ()., group="note" ( or ; ''’Ahărōn'') was a prophet, a high priest, and the elder brother of ...

(all Levites are priests, but according to P only the descendants of Aaron were to be allowed to officiate in the inner sanctuary).

P's God is majestic, and transcendent, and all things happen because of his power and will. He reveals himself in stages, first as Elohim

''Elohim'' (: ), the plural of (), is a Hebrew word meaning "gods". Although the word is plural, in the Hebrew Bible it usually takes a singular verb and refers to a single deity, particularly (but not always) the God of Israel. At other times ...

(a Hebrew word meaning simply "god", taken from the earlier Canaanite word meaning "the gods"), then to Abraham as El Shaddai

El Shaddai ( ''ʾĒl Šadday''; ) or just Shaddai is one of the names of the God of Israel. ''El Shaddai'' is conventionally translated into English as ''God Almighty'' (''Deus Omnipotens'' in Latin, الله عز وجل Allāh 'azzawajal in Ara ...

(usually translated as "God Almighty"), and finally to Moses by his unique name, Yahweh

Yahweh *''Yahwe'', was the national god of ancient Israel and Judah. The origins of his worship reach at least to the early Iron Age, and likely to the Late Bronze Age if not somewhat earlier, and in the oldest biblical literature he po ...

. P divides history into four epochs from Creation to Moses by means of covenants between God and Noah

Noah ''Nukh''; am, ኖህ, ''Noḥ''; ar, نُوح '; grc, Νῶε ''Nôe'' () is the tenth and last of the pre-Flood patriarchs in the traditions of Abrahamic religions. His story appears in the Hebrew Bible (Book of Genesis, chapters 5� ...

, Abraham and Moses. The Israelites are God's chosen people

Throughout history, various groups of people have considered themselves to be the chosen people of a deity, for a particular purpose. The phenomenon of a "chosen people" is well known among the Israelites and Jews, where the term ( he, עם ס� ...

, his relationship with them is governed by the covenants, and P's God is concerned that Israel should preserve its identity by avoiding intermarriage with non-Israelites. P is deeply concerned with "holiness", meaning the ritual purity of the people and the land: Israel is to be "a priestly kingdom and a holy nation" (Exodus 19:6), and P's elaborate rules and rituals are aimed at creating and preserving holiness.

The Priestly source is responsible for the entire Book of Leviticus

The book of Leviticus (, from grc, Λευιτικόν, ; he, וַיִּקְרָא, , "And He called") is the third book of the Torah (the Pentateuch) and of the Old Testament, also known as the Third Book of Moses. Scholars generally agree ...

, for the first of the two creation stories in Genesis (Genesis 1), for Adam's genealogy, part of the Flood story, the Table of Nations

The Generations of Noah, also called the Table of Nations or Origines Gentium, is a genealogy of the sons of Noah, according to the Hebrew Bible (Genesis ), and their dispersion into many lands after the Flood, focusing on the major known soci ...

, and the genealogy of Shem (i.e., Abraham's ancestry). Most of the remainder of Genesis is from the Yahwist, but P provides the covenant with Abraham (chapter 17) and a few other stories concerning Abraham, Isaac and Jacob. The Book of Exodus

The Book of Exodus (from grc, Ἔξοδος, translit=Éxodos; he, שְׁמוֹת ''Šəmōṯ'', "Names") is the second book of the Bible. It narrates the story of the Exodus, in which the Israelites leave slavery in Biblical Egypt through ...

is also divided between the Yahwist and P, and the usual understanding is that the Priestly writers were adding to an already-existing Yahwist narrative. P was responsible for chapters 25–31 and 35–40, the instructions for making the Tabernacle and the story of its fabrication.

While the classical documentary hypothesis posited that the Priestly material constituted an independent document which was compiled into the Pentateuch by a later redactor, most contemporary scholars now view P as a redactional layer, or commentary, on the Yahwistic and Deuteronomistic sources. Unlike J and D, the Priestly material does not seem to amount to an independent narrative when considered on its own.

Date of the Priestly source

While most scholars consider P to be one of the latest strata of the Pentateuch, post-dating both J and D, since the 1970s a number of Jewish scholars have challenged this assumption, arguing for an early dating of the Priestly material. Avi Hurvitz, for example, has forcefully argued on linguistic grounds that P represents an earlier form of the Hebrew language than what is found in bothEzekiel

Ezekiel (; he, יְחֶזְקֵאל ''Yəḥezqēʾl'' ; in the Septuagint written in grc-koi, Ἰεζεκιήλ ) is the central protagonist of the Book of Ezekiel in the Hebrew Bible.

In Judaism, Christianity, and Islam, Ezekiel is ac ...

and Deuteronomy

Deuteronomy ( grc, Δευτερονόμιον, Deuteronómion, second law) is the fifth and last book of the Torah (in Judaism), where it is called (Hebrew: hbo, , Dəḇārīm, hewords Moses.html"_;"title="f_Moses">f_Moseslabel=none)_and_th ...

, and therefore pre-dates both of them. These scholars often claim that the late-dating of P is due in large part to a Protestant bias in biblical studies which assumes that "priestly" and "ritualistic" material must represent a late degeneration of an earlier, "purer" faith. These arguments have not convinced the majority of scholars, however.

Deuteronomist

The Deuteronomist source is responsible for the core chapters (12-26) ofBook of Deuteronomy

Deuteronomy ( grc, Δευτερονόμιον, Deuteronómion, second law) is the fifth and last book of the Torah (in Judaism), where it is called (Hebrew: hbo, , Dəḇārīm, hewords Moses.html"_;"title="f_Moses">f_Moseslabel=none)_and_ ...

, containing the Deuteronomic Code, and its composition is generally dated between the 7th and 5th centuries BCE. More specifically, most scholars believe that D was composed during the late monarchic period, around the time of King Josiah, although some scholars have argued for a later date, either during the Babylonian captivity

The Babylonian captivity or Babylonian exile is the period in Jewish history during which a large number of Judeans from the ancient Kingdom of Judah were captives in Babylon, the capital city of the Neo-Babylonian Empire, following their defeat ...

(597-539 BC) or during the Persian period (539-332 BC).

The Deuteronomist conceives of as a covenant

Covenant may refer to:

Religion

* Covenant (religion), a formal alliance or agreement made by God with a religious community or with humanity in general

** Covenant (biblical), in the Hebrew Bible

** Covenant in Mormonism, a sacred agreement b ...

between the Israelites and their god Yahweh, who has chosen ("elected") the Israelites

The Israelites (; , , ) were a group of Semitic-speaking tribes in the ancient Near East who, during the Iron Age, inhabited a part of Canaan.

The earliest recorded evidence of a people by the name of Israel appears in the Merneptah Stele o ...

as his people, and requires Israel to live according to his law. Israel is to be a theocracy

Theocracy is a form of government in which one or more deities are recognized as supreme ruling authorities, giving divine guidance to human intermediaries who manage the government's daily affairs.

Etymology

The word theocracy originates fr ...

with Yahweh as the divine suzerain

Suzerainty () is the rights and obligations of a person, state or other polity who controls the foreign policy and relations of a tributary state, while allowing the tributary state to have internal autonomy. While the subordinate party is cal ...

. The law is to be supreme over all other sources of authority, including kings and royal officials, and the prophets are the guardians of the law: prophecy is instruction in the law as given through Moses, the law given through Moses is the complete and sufficient revelation of the Will of God, and nothing further is needed.

Importantly, unlike the Yahwist source, Deuteronomy insists on the centralization of worship "in the place that the Lord your God will choose." Deuteronomy never says where this place will be, but Kings

Kings or King's may refer to:

*Monarchs: The sovereign heads of states and/or nations, with the male being kings

*One of several works known as the "Book of Kings":

**The Books of Kings part of the Bible, divided into two parts

**The ''Shahnameh'' ...

makes it clear that it is Jerusalem.

Yahwist

John Van Seters characterizes the Yahwist writer as a "historian of Israelite origins," writing during theBabylonian exile

The Babylonian captivity or Babylonian exile is the period in Jewish history during which a large number of Judeans from the ancient Kingdom of Judah were captives in Babylon, the capital city of the Neo-Babylonian Empire, following their defeat ...

(597-539 BCE). The Yahwist narrative begins with the second creation story at . This is followed by the Garden of Eden story, Cain and Abel, Cain's descendants (but Adam's descendants are from P), a Flood story (tightly intertwined with a parallel account from P), Noah

Noah ''Nukh''; am, ኖህ, ''Noḥ''; ar, نُوح '; grc, Νῶε ''Nôe'' () is the tenth and last of the pre-Flood patriarchs in the traditions of Abrahamic religions. His story appears in the Hebrew Bible (Book of Genesis, chapters 5� ...

's descendants and the Tower of Babel

The Tower of Babel ( he, , ''Mīgdal Bāḇel'') narrative in Genesis 11:1–9 is an origin myth meant to explain why the world's peoples speak different languages.

According to the story, a united human race speaking a single language and mi ...

. These chapters make up the so-called Primeval history

The primeval history is the name given by biblical scholars to the first eleven chapters of the Book of Genesis, the story of the first years of the world's existence.

It tells how God creates the world and all its beings and places the first ...

, the story of mankind prior to Abraham, and J and P provide roughly equal amounts of material. The Yahwist provides the bulk of the remainder of Genesis, including the patriarchal narratives concerning Abraham, Isaac

Isaac; grc, Ἰσαάκ, Isaák; ar, إسحٰق/إسحاق, Isḥāq; am, ይስሐቅ is one of the three patriarchs of the Israelites and an important figure in the Abrahamic religions, including Judaism, Christianity, and Islam. He was ...

, Jacob

Jacob (; ; ar, يَعْقُوب, Yaʿqūb; gr, Ἰακώβ, Iakṓb), later given the name Israel, is regarded as a patriarch of the Israelites and is an important figure in Abrahamic religions, such as Judaism, Christianity, and Islam. ...

and Joseph

Joseph is a common male given name, derived from the Hebrew Yosef (יוֹסֵף). "Joseph" is used, along with "Josef", mostly in English, French and partially German languages. This spelling is also found as a variant in the languages of the m ...

.

The Book of Exodus

The Book of Exodus (from grc, Ἔξοδος, translit=Éxodos; he, שְׁמוֹת ''Šəmōṯ'', "Names") is the second book of the Bible. It narrates the story of the Exodus, in which the Israelites leave slavery in Biblical Egypt through ...

belongs in large part to the Yahwist, although it also contains significant Priestly interpolations. The Book of Numbers

The book of Numbers (from Greek Ἀριθμοί, ''Arithmoi''; he, בְּמִדְבַּר, ''Bəmīḏbar'', "In the desert f) is the fourth book of the Hebrew Bible, and the fourth of five books of the Jewish Torah. The book has a long and ...

also contains a substantial amount of Yahwist material, starting with . It includes, among other pericope

A pericope (; Greek , "a cutting-out") in rhetoric is a set of verses that forms one coherent unit or thought, suitable for public reading from a text, now usually of sacred scripture. Also can be used as a way to identify certain themes in a cha ...

s, the departure from Sinai, the story of the spies who are afraid of the giants in Canaan

Canaan (; Phoenician: 𐤊𐤍𐤏𐤍 – ; he, כְּנַעַן – , in pausa – ; grc-bib, Χανααν – ;The current scholarly edition of the Greek Old Testament spells the word without any accents, cf. Septuaginta : id est Vetus T ...

, and the refusal of the Israelites to enter the Promised Land

The Promised Land ( he, הארץ המובטחת, translit.: ''ha'aretz hamuvtakhat''; ar, أرض الميعاد, translit.: ''ard al-mi'ad; also known as "The Land of Milk and Honey"'') is the land which, according to the Tanakh (the Hebrew ...

– which then brings on the wrath of Yahweh, who condemns them to wander in the wilderness for the next forty years.

Criticism of the Yahwist as a category

The Yahwist is perhaps the most controversial source in contemporary Pentateuchal studies, with a number of scholars, especially in Europe, denying its existence altogether. A growing number of scholars have concluded that Genesis, a book traditionally assigned primarily to the Yahwist, was originally composed separately from Exodus and Numbers, and was joined to these books later by a Priestly redactor. Nevertheless, the existence and integrity of the Yahwist material still has many defenders; especially fervent among them is John Van Seters.History of scholarship

In the mid-18th century, some scholars started a critical study of doublets (parallel accounts of the same incidents), inconsistencies, and changes in style and vocabulary in the Torah. In 1780 Johann Eichhorn, building on the work of the French doctor and

In the mid-18th century, some scholars started a critical study of doublets (parallel accounts of the same incidents), inconsistencies, and changes in style and vocabulary in the Torah. In 1780 Johann Eichhorn, building on the work of the French doctor and exegete

Exegesis ( ; from the Greek , from , "to lead out") is a critical explanation or interpretation of a text. The term is traditionally applied to the interpretation of Biblical works. In modern usage, exegesis can involve critical interpretations ...

Jean Astruc

Jean Astruc (19 March 1684, in Sauve, France – 5 May 1766, in Paris) was a professor of medicine in France at Montpellier and Paris, who wrote the first great treatise on syphilis and venereal diseases, and also, with a small anonymously publ ...

's "Conjectures" and others, formulated the "older documentary hypothesis": the idea that Genesis was composed by combining two identifiable sources, the Jehovist ("J"; also called the Yahwist) and the Elohist

According to the documentary hypothesis, the Elohist (or simply E) is one of four source documents underlying the Torah,McDermott, John J., ''Reading the Pentateuch: A Historical Introduction'' (Pauline Press, 2002) p. 21. Via Books.google.com.au ...

("E"). These sources were subsequently found to run through the first four books of the Torah, and the number was later expanded to three when Wilhelm de Wette Wilhelm Martin Leberecht de Wette (12 January 1780 – 16 June 1849) was a German theologian and biblical scholar.

Life and education

Wilhelm Martin Leberecht de Wette was born 12 January 1780 in Ulla (now part of the municipality of Nohra), Thuri ...

identified the Deuteronomist

The Deuteronomist, abbreviated as either Dtr or simply D, may refer either to the source document underlying the core chapters (12–26) of the Book of Deuteronomy, or to the broader "school" that produced all of Deuteronomy as well as the Deuter ...

as an additional source found only in Deuteronomy ("D"). Later still the Elohist was split into Elohist and Priestly ("P") sources, increasing the number to four.

These documentary approaches were in competition with two other models, the fragmentary and the supplementary. The fragmentary hypothesis argued that fragments of varying lengths, rather than continuous documents, lay behind the Torah; this approach accounted for the Torah's diversity but could not account for its structural consistency, particularly regarding chronology. The supplementary hypothesis was better able to explain this unity: it maintained that the Torah was made up of a central core document, the Elohist, supplemented by fragments taken from many sources. The supplementary approach was dominant by the early 1860s, but it was challenged by an important book published by Hermann Hupfeld

Hermann Hupfeld (31 March 1796 – 24 April 1866) was a Protestant German Orientalist and Biblical commentator. He is known for his historical-critical studies of the Old Testament.Karl Heinrich Graf argued that the Yahwist and Elohist were the earliest sources and the Priestly source the latest, while Wilhelm Vatke linked the four to an evolutionary framework, the Yahwist and Elohist to a time of primitive nature and fertility cults, the Deuteronomist to the ethical religion of the Hebrew prophets, and the Priestly source to a form of religion dominated by ritual, sacrifice and law.

In 1878

In 1878  Wellhausen's documentary hypothesis owed little to Wellhausen himself but was mainly the work of Hupfeld, Eduard Eugène Reuss, Graf, and others, who in turn had built on earlier scholarship. He accepted Hupfeld's four sources and, in agreement with Graf, placed the Priestly work last. J was the earliest document, a product of the 10th century BCE and the court of

Wellhausen's documentary hypothesis owed little to Wellhausen himself but was mainly the work of Hupfeld, Eduard Eugène Reuss, Graf, and others, who in turn had built on earlier scholarship. He accepted Hupfeld's four sources and, in agreement with Graf, placed the Priestly work last. J was the earliest document, a product of the 10th century BCE and the court of

The modern supplementary hypothesis came to a head in the 1970s with the publication of works by

The modern supplementary hypothesis came to a head in the 1970s with the publication of works by

Wellhausen and the new documentary hypothesis

In 1878

In 1878 Julius Wellhausen

Julius Wellhausen (17 May 1844 – 7 January 1918) was a German biblical scholar and orientalist. In the course of his career, he moved from Old Testament research through Islamic studies to New Testament scholarship. Wellhausen contributed to t ...

published ''Geschichte Israels, Bd 1'' ("History of Israel, Vol 1"); the second edition he printed as '' Prolegomena zur Geschichte Israels'' ("Prolegomena to the History of Israel"), in 1883, and the work is better known under that name. (The second volume, a synthetic history titled ''Israelitische und jüdische Geschichte'' Israelite and Jewish History" did not appear until 1894 and remains untranslated.) Crucially, this historical portrait was based upon two earlier works of his technical analysis: "Die Composition des Hexateuchs" ("The Composition of the Hexateuch") of 1876/77 and sections on the "historical books" (Judges–Kings) in his 1878 edition of Friedrich Bleek Friedrich Bleek (4 July 1793, in Ahrensbök in Holstein (a village near Lübeck)27 February 1859, in Bonn), was a German Biblical scholar.

Life

At 16 Bleek's father sent him to the gymnasium at Lübeck, where he became so interested in ancient lang ...

's ''Einleitung in das Alte Testament'' ("Introduction to the Old Testament").

Solomon

Solomon (; , ),, ; ar, سُلَيْمَان, ', , ; el, Σολομών, ; la, Salomon also called Jedidiah (Hebrew language, Hebrew: , Modern Hebrew, Modern: , Tiberian Hebrew, Tiberian: ''Yăḏīḏăyāh'', "beloved of Yahweh, Yah"), ...

; E was from the 9th century in the northern Kingdom of Israel

The Kingdom of Israel may refer to any of the historical kingdoms of ancient Israel, including:

Fully independent (c. 564 years)

*Kingdom of Israel (united monarchy) (1047–931 BCE), the legendary kingdom established by the Israelites and uniting ...

, and had been combined by a redactor (editor) with J to form a document JE; D, the third source, was a product of the 7th century BCE, by 620 BCE, during the reign of King Josiah; P (what Wellhausen first named "Q") was a product of the priest-and-temple dominated world of the 6th century; and the final redaction, when P was combined with JED to produce the Torah as we now know it.

Wellhausen's explanation of the formation of the Torah was also an explanation of the religious history of Israel. The Yahwist and Elohist described a primitive, spontaneous and personal world, in keeping with the earliest stage of Israel's history; in Deuteronomy he saw the influence of the prophets and the development of an ethical outlook, which he felt represented the pinnacle of Jewish religion; and the Priestly source reflected the rigid, ritualistic world of the priest-dominated post-exilic period. His work, notable for its detailed and wide-ranging scholarship and close argument, entrenched the "new documentary hypothesis" as the dominant explanation of Pentateuchal origins from the late 19th to the late 20th centuries.The two-source hypothesis of Eichorn was the "older" documentary hypothesis, and the four-source hypothesis adopted by Wellhausen was the "newer".

Collapse of the documentary consensus

The consensus around the documentary hypothesis collapsed in the last decades of the 20th century. Three major publications of the 1970s caused scholars to seriously question the assumptions of the documentary hypothesis: ''Abraham in History and Tradition

:''This article presents information about the John Van Seters book; for general information about the topic, see Abraham: Historicity and origins and The Bible and history.''

''Abraham in History and Tradition'' is a book by biblical scholar ...

'' by John Van Seters

John Van Seters (born May 2, 1935 in Hamilton, Ontario) is a Canadian scholar of the Hebrew Bible (Old Testament) and the Ancient Near East. Currently University Distinguished Professor Emeritus at the University of North Carolina, he was formerly ...

, ''Der sogenannte Jahwist'' ("The So-Called Yahwist") by Hans Heinrich Schmid

Hans Heinrich Schmid (22 October 1937 in Winterthur, Canton of Zürich – 4 October 2014) was a Swiss Protestant Reformed theologian, University Professor and University Rector.

Life

He was the son of the Zurich pastor Gotthard Schmid (1909-1968) ...

, and ''Das überlieferungsgeschichtliche Problem des Pentateuch'' ("The Tradition-Historical Problem of the Pentateuch") by Rolf Rendtorff

Rolf Rendtorff (10 May 1925 – 1 April 2014) was Emeritus Professor of Old Testament at the University of Heidelberg. He has written frequently on the Jewish scriptures and was notable chiefly for his contribution to the debate over the origins o ...

. These three authors shared many of the same criticisms of the documentary hypothesis, but were not in agreement about what paradigm ought to replace it.

Van Seters and Schmid both forcefully argued, to the satisfaction of most scholars, that the Yahwist source could not be dated to the Solomonic period (c. 950 BCE) as posited by the documentary hypothesis. They instead dated J to the period of the Babylonian captivity

The Babylonian captivity or Babylonian exile is the period in Jewish history during which a large number of Judeans from the ancient Kingdom of Judah were captives in Babylon, the capital city of the Neo-Babylonian Empire, following their defeat ...

(597-539 BCE), or the late monarchic period at the earliest. Van Seters also sharply criticized the idea of a substantial Elohist source, arguing that E extends at most to two short passages in Genesis. This view has now been accepted by the vast majority of scholars.

Some scholars, following Rendtorff, have come to espouse a fragmentary hypothesis, in which the Pentateuch is seen as a compilation of short, independent narratives, which were gradually brought together into larger units in two editorial phases: the Deuteronomic and the Priestly phases. By contrast, scholars such as John Van Seters advocate a supplementary hypothesis

In biblical studies, the supplementary hypothesis proposes that the Pentateuch (the first five books of the Bible) was derived from a series of direct additions to an existing corpus of work. It serves as a revision to the earlier documentary hy ...

, which posits that the Torah is the result of two major additions— Yahwist and Priestly— to an existing corpus of work.

Scholars frequently use these newer hypotheses in combination with each other and with a documentary model, making it difficult to classify contemporary theories as strictly one or another. The majority of scholars today continue to recognise Deuteronomy as a source, with its origin in the law-code produced at the court of Josiah

Josiah ( or ) or Yoshiyahu; la, Iosias was the 16th king of Judah (–609 BCE) who, according to the Hebrew Bible, instituted major religious reforms by removing official worship of gods other than Yahweh. Josiah is credited by most biblical ...

as described by De Wette, subsequently given a frame during the exile (the speeches and descriptions at the front and back of the code) to identify it as the words of Moses. Most scholars also agree that some form of Priestly source existed, although its extent, especially its end-point, is uncertain. The remainder is called collectively non-Priestly, a grouping which includes both pre-Priestly and post-Priestly material.

The general trend in recent scholarship is to recognize the final form of the Torah as a literary and ideological unity, based on earlier sources, likely completed during the Persian period (539-333 BCE). Some scholars would place its final compilation somewhat later, however, in the Hellenistic period

In Classical antiquity, the Hellenistic period covers the time in Mediterranean history after Classical Greece, between the death of Alexander the Great in 323 BC and the emergence of the Roman Empire, as signified by the Battle of Actium in ...

(333–164 BCE).

Contemporary models

''The table is based on that in Walter Houston's "The Pentateuch", with expansions as indicated. Note that the three hypotheses are not mutually exclusive.''Neo-documentary hypothesis

A revised neo-documentary hypothesis still has adherents, especially in North America and Israel. This distinguishes sources by means of plot and continuity rather than stylistic and linguistic concerns, and does not tie them to stages in the evolution of Israel's religious history. Its resurrection of an E source is probably the element most often criticised by other scholars, as it is rarely distinguishable from the classical J source, and European scholars have largely rejected it as fragmentary or non-existent.Supplementary hypothesis

The modern supplementary hypothesis came to a head in the 1970s with the publication of works by

The modern supplementary hypothesis came to a head in the 1970s with the publication of works by John Van Seters

John Van Seters (born May 2, 1935 in Hamilton, Ontario) is a Canadian scholar of the Hebrew Bible (Old Testament) and the Ancient Near East. Currently University Distinguished Professor Emeritus at the University of North Carolina, he was formerly ...

and Hans Heinrich Schmid

Hans Heinrich Schmid (22 October 1937 in Winterthur, Canton of Zürich – 4 October 2014) was a Swiss Protestant Reformed theologian, University Professor and University Rector.

Life

He was the son of the Zurich pastor Gotthard Schmid (1909-1968) ...

. Van Seters’ summation of the hypothesis accepts "three sources or literary strata within the Pentateuch," which have come to be known as the Deuteronomist

The Deuteronomist, abbreviated as either Dtr or simply D, may refer either to the source document underlying the core chapters (12–26) of the Book of Deuteronomy, or to the broader "school" that produced all of Deuteronomy as well as the Deuter ...

(D), the Yahwist

The Jahwist, or Yahwist, often abbreviated J, is one of the most widely recognized sources of the Pentateuch (Torah), together with the Deuteronomist, the Priestly source and the Elohist. The existence of the Jahwist is somewhat controversial, ...

(J), and the Priestly Writer (P). Van Seters ordered the sources chronologically as DJP.

* the Deuteronomist source (D) was likely written c. 620 BCE.

* the Yahwist source (J) was likely written c. 540 BCE in the exilic period.

* the Priestly source (P) was likely written c. 400 BCE in the post-exilic

The Second Temple period in Jewish history lasted approximately 600 years (516 BCE - 70 CE), during which the Second Temple existed. It started with the return to Zion and the construction of the Second Temple, while it ended with the First Jewis ...

period.

The supplementary hypothesis denies the existence of an extensive Elohist (E) source, one of the four independent sources described in the documentary hypothesis. Instead, it describes the Yahwist as having borrowed from an array of written and oral traditions, combining them into the J source. It proposes that because J is compiled from many earlier traditions and stories, documentarians mistook the compilation as having multiple authors: the Yahwist (J) ''and'' the Elohist (E). Instead, the supplementary hypothesis proposes that what documentarians considered J and E are in fact a single source (some use J, some use JE), likely written in the 6th century BCE.

Notably, in contrast to the traditional documentary hypothesis, the supplementary hypothesis proposes that the Deuteronomist (D) was the earliest Pentateuchal author, writing at the end of the seventh century.

Fragmentary hypothesis

The fragmentary or block-composition approach views the Torah as a compilation of a large number of short, originally independent narratives. On this view, broad categories such as the Yahwist, Priestly, and Deuteronomist sources are insufficient to account for the diversity found in the Torah, and are rejected. In place of source criticism, the method ofform criticism

Form criticism as a method of biblical criticism classifies units of scripture by literary pattern and then attempts to trace each type to its period of oral transmission."form criticism." Encyclopædia Britannica. 2007. Encyclopædia Britannica ...

is used to trace the origin of the various traditions found in the Pentateuch. Fragmentarians differ, however, in how they believe these traditions were transmitted over time. Mid-twentieth century scholars like Gerhard von Rad

Gerhard von Rad (21 October 1901 – 31 October 1971) was a German academic, Old Testament scholar, Lutheran theologian, exegete, and professor at the University of Heidelberg.

Early life, education, career

Gerhard von Rad was born in Nurem ...

and Martin Noth

Martin Noth (3 August 1902 – 30 May 1968) was a German scholar of the Hebrew Bible who specialized in the pre-Exilic history of the Hebrews and promoted the hypothesis that the Israelite tribes in the immediate period after the settlement in Can ...

argued that the transmission of Pentateuchal narratives occurred primarily through oral tradition

Oral tradition, or oral lore, is a form of human communication wherein knowledge, art, ideas and Culture, cultural material is received, preserved, and transmitted orally from one generation to another.Jan Vansina, Vansina, Jan: ''Oral Traditio ...

. More recent work in the fragmentary school, such as that of Rolf Rendtorff

Rolf Rendtorff (10 May 1925 – 1 April 2014) was Emeritus Professor of Old Testament at the University of Heidelberg. He has written frequently on the Jewish scriptures and was notable chiefly for his contribution to the debate over the origins o ...

and especially Erhardt Blum, has replaced the model of oral transmission with one of literary composition.

See also

*Authorship of the Bible

Table I gives an overview of the periods and dates ascribed to the various books of the Bible. Tables II, III and IV outline the conclusions of the majority of contemporary scholars on the composition of the Hebrew Bible and the Protestant Old ...

* Biblical criticism

Biblical criticism is the use of critical analysis to understand and explain the Bible. During the eighteenth century, when it began as ''historical-biblical criticism,'' it was based on two distinguishing characteristics: (1) the concern to ...

* Books of the Bible

A biblical canon is a set of texts (also called "books") which a particular Jewish or Christian religious community regards as part of the Bible.

The English word ''canon'' comes from the Greek , meaning " rule" or " measuring stick". The u ...

* Dating the Bible

The oldest surviving Hebrew Bible manuscripts—including the Dead Sea Scrolls—date to about the 2nd century BCE ( fragmentary) and some are stored at the Shrine of the Book in Jerusalem. The oldest extant complete text survives in a Greek t ...

* Mosaic authorship

Mosaic authorship is the Judeo-Christian tradition that the Torah, the first five books of the Hebrew Bible/Old Testament, were dictated by God to Moses. The tradition probably began with the legalistic code of the Book of Deuteronomy and was t ...

Notes

References

Bibliography

* * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * {{refend Biblical authorship debates Biblical criticism Documentary hypothesis Torah