Electoral system

An electoral system or voting system is a set of rules that determine how elections and referendums are conducted and how their results are determined. Electoral systems are used in politics to elect governments, while non-political elections ma ...

s are the rules for conducting elections, a main component of which is the algorithm for determining the winner (or several winners) from the ballots cast. This article discusses methods and results of comparing different electoral systems, both those which elect a unique candidate in a 'single-winner' election and those which elect a group of representatives in a

multiwinner election.

There are 4 main types of reasoning which have been used to try to determine the best voting method:

#

Argument by example

#

Adherence to logical criteria

#

Results of simulated elections

#

Results of real elections

Expert opinions on single-winner voting methods

In 2010, a panel of 22 experts on voting procedures were asked: "What is the best voting rule for your town to use to elect the mayor?". One member abstained. Approval voting was used to decide between 18 single-winner voting methods. The ranking (with number ''N'' of approvers from a maximum of 21) of the various systems was as follows.

[

Note: this list is not representative of all available single-winner voting methods, and several of the experts involved later noted flaws in the way that the poll was conducted. The organizer of the poll argues that the results should not be generalized, referring to it as a "naive vote on voting rules".][

]

Pragmatic considerations

One intellectual problem posed by voting theory is that of devising systems which are ''accurate'' in some sense. However, there are also practical reasons why one system may be more socially acceptable than another.[R. B. Darlington, 'Are Condorcet and Minimax Voting Systems the Best?' (v8, 2021).][

The important factors can be grouped under 3 headings:

* Intelligibility, which Tideman defines as "the capacity of the rule to gain the trust of voters" and "depends on the reasonableness and understandability of the logic of the rule".][

* Ease of voting. Different forms of ballot make it more or less difficult for voters to fill in ballot papers fairly reflecting their views.

* Ease of counting. Voting systems which can make their decisions from a small set of counts derived from ballots are logistically less burdensome than those which need to consult the entire set of ballots. Some voting systems require powerful computational resources to determine the winner. Even if the cost is not prohibitive for electoral use, it may preclude effective evaluation.

]

Candidacy effects

A separate topic is the fact that different candidates may be encouraged to run for election under different voting systems. The fear of wasted vote In electoral systems, a wasted vote is any vote which is not for an elected candidate or, more broadly, a vote that does not help to elect a candidate. The narrower meaning includes ''lost votes'', being only those votes which are for a losing candi ...

s under FPTP puts a lot of power in the hands of the groups who select candidates. A different voting system might lead to more satisfactory decisions without necessarily being fairer in any abstract sense. This topic has received little analytic study.

Evaluation by simulation

Models of the electoral process

Voting methods can be evaluated by measuring their accuracy under random simulated elections aiming to be faithful to the properties of elections in real life. The first such evaluation was conducted by Chamberlin and Cohen in 1978, who measured the frequency with which certain non-Condorcet systems elected Condorcet winners.[J. R. Chamberlin and M. D. Cohen, "Toward Applicable Social Choice Theory...", (1978).] There are three main types of model which have been proposed as representations of the electoral process, two of which can be combined in a hybrid. A fourth type of model, the utilitarian model, is of conceptual significance in spite of not being used in practice, though spatial models are sometimes presented in utilitarian guise.

Condorcet's jury model

The Marquis de Condorcet viewed an election as analogous to a jury vote in which each member expresses an independent judgement on the quality of candidates. On this account the candidates differ in objective merit and the electors express independent views of the relative merits of the candidates. So long as the voters' judgements are better than random, a sufficiently large electorate will always choose the best candidate. A jury model is sometimes known as a valence model.

The jury model implies a natural concept of accuracy for voting systems: the likelier a system is to elect the best candidate, the better the system. This may be seen as providing a semantics

Semantics (from grc, σημαντικός ''sēmantikós'', "significant") is the study of reference, meaning, or truth. The term can be used to refer to subfields of several distinct disciplines, including philosophy, linguistics and comp ...

for electoral decisions.

Condorcet and his contemporary Laplace realised that voting theory could thus be reduced to probability theory – Condorcet's main work was titled ''Essai sur l'application de l'analyse à la probabilité des décisions rendues à la pluralité des voix''. Their ideas were revived in the twentieth century when it was shown under a jury model that the Kemeny-Young voting method is the maximum likelihood estimator of the ordering of candidates by merit.

Black's spatial model

The main weakness of Condorcet's model is its assumption of independence: it implies that there can be no tendency for voters who prefer A to B to also prefer C to D. This flies in the face of evidence: someone who prefers a certain ''montagnard '' to a certain ''girondin'' will probably also prefer a second ''montagnard '' to a second ''girondin''; it also explains why even arbitrarily large juries are fallible, since members will make common mistakes.

Duncan Black

Duncan Black, FBA (23 May 1908 – 14 January 1991) was a Scottish economist who laid the foundations of social choice theory. In particular he was responsible for unearthing the work of many early political scientists, including Charles Lutw ...

proposed a one-dimensional spatial model of voting in 1948, viewing elections as ideologically driven.[Duncan Black, "On the Rationale of Group Decision-making" (1948).] His ideas were later expanded by Anthony Downs.[Anthony Downs, "]An Economic Theory of Democracy

''An Economic Theory of Democracy'' is a treatise of economics written by Anthony Downs, published in 1957. The book set forth a model with precise conditions under which economic theory could be applied to non-market political decision-making. ...

" (1957). Voters' opinions are regarded as positions in a space of one or more dimensions; candidates have positions in the same space; and voters choose candidates in order of proximity (measured under Euclidean distance or some other metric).

Spatial models imply a different notion of merit for voting systems: the more acceptable the winning candidate may be as a location parameter for the voter distribution, the better the system. A political spectrum

A political spectrum is a system to characterize and classify different political positions in relation to one another. These positions sit upon one or more geometric axes that represent independent political dimensions. The expressions politi ...

is a one-dimensional spatial model.

Arrow's neutral model

Kenneth Arrow

Kenneth Joseph Arrow (23 August 1921 – 21 February 2017) was an American economist, mathematician, writer, and political theorist. He was the joint winner of the Nobel Memorial Prize in Economic Sciences with John Hicks in 1972.

In economics ...

worked within a framework in which the ballots are the ultimate reality rather than being 'messages' (as Balinski and Laraki put it[M. Balinski and R. Laraki, "A theory of measuring, electing, and ranking" (2007).] ) conveying partial (and possibly misleading) information about some reality behind them. He did not propose this agnosticism as a realistic picture of voting, but rather as defining elections as mathematical objects whose properties could be investigated. His famous Impossibility theorem shows (under certain assumptions) that for any ranked voting system, there exist sets of ballots (obtainable under a neutral model) which violate at least one of three criteria often considered to be desirable.

A neutral model does not bring with it any concept of accuracy or truth for voting systems.

Impartial culture models define distributions of ballots cast under a neutral voting model, treating the electorate as a random noise source.

Hybrid models

It is possible to combine jury models with spatial models: it can be assumed that voters are influenced partly by their views of the qualities of candidates and partly by ideological considerations. This breaks their preferences down into separate independent and non-independent components. Hybrid models are discussed briefly by Darlington[ but have not been widely adopted.

]

Empirical comparison

Tideman and Plassmann conducted a study which showed that a two-dimensional spatial model gave a reasonable fit to 3-candidate reductions of a large set of electoral rankings. Jury and neutral models and one-dimensional spatial models were shown to be inadequate but hybrid models were not considered.[T. N. Tideman and F. Plassmann, "Modeling the Outcomes of Vote-Casting in Actual Elections" (2012).]

They looked at Condorcet cycles in voter preferences (an example of which is A being preferred to B by a majority of voters, B to C and C to A) and found that the number of them was consistent with small-sample effects, concluding that "voting cycles will occur very rarely, if at all, in elections with many voters".

The relevance of sample size had been studied previously by Gordon Tullock

Gordon Tullock (; February 13, 1922 – November 3, 2014) was an economist and professor of law and Economics at the George Mason University School of Law. He is best known for his work on public choice theory, the application of economic thinkin ...

, who argued graphically that although finite electorates will always be prone to cycles, the area in which candidates may give rise to cycling becomes progressively smaller as the number of voters increases.

Utilitarian models

A utilitarian

In ethical philosophy, utilitarianism is a family of normative ethical theories that prescribe actions that maximize happiness and well-being for all affected individuals.

Although different varieties of utilitarianism admit different charac ...

model views voters as ranking candidates in order of utility. The rightful winner, under this model, is the candidate who maximises overall social utility. A utilitarian model differs from a spatial model in several important ways:

* It requires the additional assumption that voters are motivated solely by informed self-interest, with no ideological taint to their preferences.

* It requires the distance metric of a spatial model to be replaced by a faithful measure of utility.

* Consequently the metric will need to differ between voters. It often happens that one group of voters will be powerfully affected by the choice between two candidates while another group has little at stake; the metric will then need to be highly asymmetric.

It follows from the last property that no voting system which gives equal influence to all voters is likely to achieve maximum social utility. Extreme cases of conflict between the claims of utilitarianism and democracy are referred to as the 'tyranny of the majority

The tyranny of the majority (or tyranny of the masses) is an inherent weakness to majority rule in which the majority of an electorate pursues exclusively its own objectives at the expense of those of the minority factions. This results in oppres ...

'. See Laslier's, Merlin's and Nurmi's comments in Laslier's write-up.[

]James Mill

James Mill (born James Milne; 6 April 1773 – 23 June 1836) was a Scottish historian, economist, political theorist, and philosopher. He is counted among the founders of the Ricardian school of economics. He also wrote ''The History of Brit ...

seems to have been the first to claim the existence of an ''a priori'' connection between democracy and utilitarianism – see the Stanford Encyclopedia article and Macaulay's 'famous attack'.

Comparisons under a jury model

Suppose that the ''i th '' candidate in an election has merit ''xi'' (we may assume that ''xi'' ~ ''N'' (0,σ2)), and that voter ''j'' 's level of approval for candidate ''i'' may be written as ''xi'' + ε''ij'' (we will assume that the ε''ij'' are iid. ''N'' (0,τ2)). We assume that a voter ranks candidates in decreasing order of approval. We may interpret ε''ij'' as the error in voter ''j'' 's valuation of candidate ''i'' and regard a voting method as having the task of finding the candidate of greatest merit.

Each voter will rank the better of two candidates higher than the less good with a determinate probability ''p'' (which under the normal model outlined here is equal to , as can be confirmed from a standard formula for Gaussian integrals over a quadrant).

Condorcet's jury theorem

Condorcet's jury theorem is a political science theorem about the relative probability of a given group of individuals arriving at a correct decision. The theorem was first expressed by the Marquis de Condorcet in his 1785 work ''Essay on the App ...

shows that so long as ''p'' > , the majority vote of a jury will be a better guide to the relative merits of two candidates than is the opinion of any single member.

Peyton Young

Hobart Peyton Young (born March 9, 1945) is an American game theorist and economist known for his contributions to evolutionary game theory and its application to the study of institutional and technological change, as well as the theory of learn ...

showed that three further properties apply to votes between arbitrary numbers of candidates, suggesting that Condorcet was aware of the first and third of them.[H. P. Young, "Condorcet's Theory of Voting" (1988).]

* If ''p'' is close to , then the Borda winner is the maximum likelihood estimator of the best candidate.

* if ''p'' is close to 1, then the Minimax winner is the maximum likelihood estimator of the best candidate.

* For any ''p'', the Kemeny-Young ranking is the maximum likelihood estimator of the true order of merit.

Robert F. Bordley constructed a 'utilitarian' model which is a slight variant of Condorcet's jury model.[R. F. Bordley, "A Pragmatic Method for Evaluating Election Schemes through Simulation" (1983).] He viewed the task of a voting method as that of finding the candidate who has the greatest total approval from the electorate, i.e. the highest sum of individual voters' levels of approval. This model makes sense even with σ2 = 0, in which case ''p'' takes the value where ''n'' is the number of voters. He performed an evaluation under this model, finding as expected that the Borda count was most accurate.

Simulated elections under spatial models

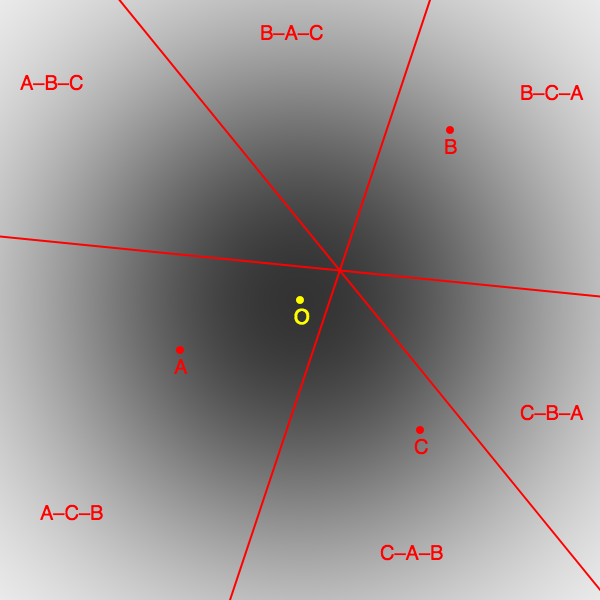

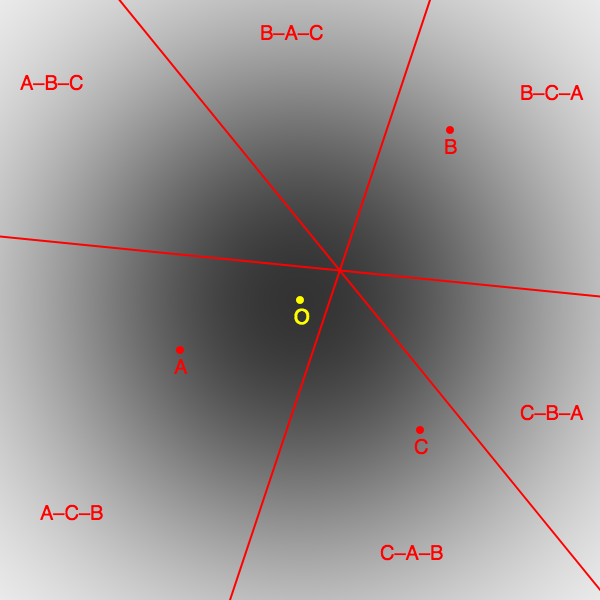

A simulated election can be constructed from a distribution of voters in a suitable space. The illustration shows voters satisfying a bivariate Gaussian distribution centred on O. There are 3 randomly generated candidates, A, B and C. The space is divided into 6 segments by 3 lines, with the voters in each segment having the same candidate preferences. The proportion of voters ordering the candidates in any way is given by the integral of the voter distribution over the associated segment.

The proportions corresponding to the 6 possible orderings of candidates determine the results yielded by different voting systems. Those which elect the best candidate, i.e. the candidate closest to O (who in this case is A), are considered to have given a correct result, and those which elect someone else have exhibited an error. By looking at results for large numbers of randomly generated candidates the empirical properties of voting systems can be measured.

The evaluation protocol outlined here is modelled on the one described by Tideman and Plassmann.

A simulated election can be constructed from a distribution of voters in a suitable space. The illustration shows voters satisfying a bivariate Gaussian distribution centred on O. There are 3 randomly generated candidates, A, B and C. The space is divided into 6 segments by 3 lines, with the voters in each segment having the same candidate preferences. The proportion of voters ordering the candidates in any way is given by the integral of the voter distribution over the associated segment.

The proportions corresponding to the 6 possible orderings of candidates determine the results yielded by different voting systems. Those which elect the best candidate, i.e. the candidate closest to O (who in this case is A), are considered to have given a correct result, and those which elect someone else have exhibited an error. By looking at results for large numbers of randomly generated candidates the empirical properties of voting systems can be measured.

The evaluation protocol outlined here is modelled on the one described by Tideman and Plassmann.[

Evaluations of this type are commonest for single-winner electoral systems. ]Ranked voting

The term ranked voting (also known as preferential voting or ranked choice voting) refers to any voting system in which voters rank their candidates (or options) in a sequence of first or second (or third, etc.) on their respective ballots. Ra ...

systems fit most naturally into the framework, but other types of ballot (such a FPTP

In a first-past-the-post electoral system (FPTP or FPP), formally called single-member plurality voting (SMP) when used in single-member districts or informally choose-one voting in contrast to ranked voting, or score voting, voters cast their ...

and Approval voting) can be accommodated with lesser or greater effort.

The evaluation protocol can be varied in a number of ways:

* The number of voters can be made finite and varied in size. In practice this is almost always done in multivariate models, with voters being sampled from their distribution and results for large electorates being used to show limiting behaviour.

* The number of candidates can be varied.

* The voter distribution could be varied; for instance, the effect of asymmetric distributions could be examined. A minor departure from normality is entailed by random sampling effects when the number of voters is finite. More systematic departures (seemingly taking the form of a Gaussian mixture model) were investigated by Jameson Quinn in 2017.

Evaluation for accuracy

One of the main uses of evaluations is to compare the accuracy of voting systems when voters vote sincerely. If an infinite number of voters satisfy a Gaussian distribution, then the rightful winner of an election can be taken to be the candidate closest to the mean/median, and the accuracy of a method can be identified with the proportion of elections in which the rightful winner is elected. The median voter theorem The median voter theorem is a proposition relating to ranked preference voting put forward by Duncan Black in 1948.Duncan Black, "On the Rationale of Group Decision-making" (1948). It states that if voters and policies are distributed along a one-d ...

guarantees that all Condorcet systems will give 100% accuracy (and the same applies to Coombs' method

Coombs' method or the Coombs ruleGrofman, Bernard, and Scott L. Feld (2004"If you like the alternative vote (a.k.a. the instant runoff), then you ought to know about the Coombs rule,"''Electoral Studies'' 23:641-59. is a ranked voting system whic ...

[B. Grofman and S. L. Feld, "If you like the alternative vote (a.k.a. the instant runoff), then you ought to know about the Coombs rule" (2004).]).

Evaluations published in research papers use multidimensional Gaussians, making the calculation numerically difficult.[ The number of voters is kept finite and the number of candidates is necessarily small.

] The computation is much more straightforward in a single dimension, which allows an infinite number of voters and an arbitrary number ''m'' of candidates. Results for this simple case are shown in the first table, which is directly comparable with Table 5 (1000 voters, medium dispersion) of the cited paper by Chamberlin and Cohen. The candidates were sampled randomly from the voter distribution and a single Condorcet method ( Minimax) was included in the trials for confirmation.

The relatively poor performance of the

The computation is much more straightforward in a single dimension, which allows an infinite number of voters and an arbitrary number ''m'' of candidates. Results for this simple case are shown in the first table, which is directly comparable with Table 5 (1000 voters, medium dispersion) of the cited paper by Chamberlin and Cohen. The candidates were sampled randomly from the voter distribution and a single Condorcet method ( Minimax) was included in the trials for confirmation.

The relatively poor performance of the Alternative vote

Instant-runoff voting (IRV) is a type of Ranked voting, ranked preferential Electoral system, voting method. It uses a Majority rule, majority voting rule in single-winner elections where there are more than two candidates. It is commonly referr ...

(IRV) is explained by the well known and common source of error illustrated by the diagram, in which the election satisfies a univariate spatial model and the rightful winner B will be eliminated in the first round. A similar problem exists in all dimensions.

An alternative measure of accuracy is the average distance of voters from the winner (in which smaller means better). This is unlikely to change the ranking of voting methods, but is preferred by people who interpret distance as disutility. The second table shows the average distance (in standard deviations) ''minus'' (which is the average distance of a variate from the centre of a standard Gaussian distribution) for 10 candidates under the same model.

Evaluation for resistance to

tactical voting

Strategic voting, also called tactical voting, sophisticated voting or insincere voting, occurs in voting systems when a voter votes for another candidate or party than their ''sincere preference'' to prevent an undesirable outcome. For example, ...

James Green-Armytage et al. published a study in which they assessed the vulnerability of several voting systems to manipulation by voters.[J. Green-Armytage, T. N. Tideman and R. Cosman, "Statistical Evaluation of Voting Rules" (2015).] They say little about how they adapted their evaluation for this purpose, mentioning simply that it 'requires creative programming'. An earlier paper by the first author gives a little more detail.[J. Green-Armytage, "Strategic voting and nomination" (2011).]

The number of candidates in their simulated elections was limited to 3. This removes the distinction between certain systems; for instance Black's method and the Dasgupta-Maskin method are equivalent on 3 candidates.

The conclusions from the study are hard to summarise, but the Borda count

The Borda count is a family of positional voting rules which gives each candidate, for each ballot, a number of points corresponding to the number of candidates ranked lower. In the original variant, the lowest-ranked candidate gets 0 points, the ...

performed badly; Minimax was somewhat vulnerable; and IRV was highly resistant. The authors showed that limiting any method to elections with no Condorcet winner (choosing the Condorcet winner when there was one) would never increase its susceptibility to tactical voting. They reported that the 'Condorcet-Hare' system which uses IRV as a tie-break for elections not resolved by the Condorcet criterion was as resistant to tactical voting as IRV on its own and more accurate. Condorcet-Hare is equivalent to Copeland's method

Copeland's method is a ranked voting method based on a scoring system of pairwise "wins", "losses", and "ties". The method has a long history:

* Ramon Llull described the system in 1299, so it is sometimes referred to as "Llull's method"

* The ...

with an IRV tie-break in elections with 3 candidates.

Evaluation for the effect of the candidate distribution

Some systems, and the Borda count in particular, are vulnerable when the distribution of candidates is displaced relative to the distribution of voters. The attached table shows the accuracy of the Borda count (as a percentage) when an infinite population of voters satisfies a univariate Gaussian distribution and ''m'' candidates are drawn from a similar distribution offset by ''x'' standard distributions. Red colouring indicates figures which are worse than random. Recall that all Condorcet methods give 100% accuracy for this problem. (And notice that the reduction in accuracy as ''x'' increases is not seen when there are only 3 candidates.)

Sensitivity to the distribution of candidates can be thought of as a matter either of accuracy or of resistance to manipulation. If one expects that in the course of things candidates will naturally come from the same distribution as voters, then any displacement will be seen as attempted subversion; but if one thinks that factors determining the viability of candidacy (such as financial backing) may be correlated with ideological position, then one will view it more in terms of accuracy.

Published evaluations take different views of the candidate distribution. Some simply assume that candidates are drawn from the same distribution as voters.[ Several older papers assume equal means but allow the candidate distribution to be more or less tight than the voter distribution.][S, Merrill III, "A Comparison of Efficiency of Multicandidate Electoral Systems" (1984).][ A paper by Tideman and Plassmann approximates the relationship between candidate and voter distributions based on empirical measurements.][T. N. Tideman and F. Plassmann, "Which voting rule is most likely to choose the "best" candidate?" (2012).] This is less realistic than it may appear, since it makes no allowance for the candidate distribution to adjust to exploit any weakness in the voting system. A paper by James Green-Armytage looks at the candidate distribution as a separate issue, viewing it as a form of manipulation and measuring the effects of strategic entry and exit. Unsurprisingly he finds the Borda count to be particularly vulnerable.[

]

Evaluation for other properties

* As previously mentioned, Chamberlin and Cohen measured the frequency with which certain non-Condorcet systems elect Condorcet winners. Under a spatial model with equal voter and candidate distributions the frequencies are 99% ( Coombs), 86% (Borda), 60% (IRV) and 33% (FPTP).[ This is sometimes known as Condorcet efficiency.

* Darlington measured the frequency with which Copeland's method produces a unique winner in elections with no Condorcet winner. He found it to be less than 50% for fields of up to 10 candidates.][R. B. Darlington, "Minimax Is the Best Electoral System After All" (2016).]

Experimental metrics

The task of a voting system under a spatial model is to identify the candidate whose position most accurately represents the distribution of voter opinions. This amounts to choosing a location parameter for the distribution from the set of alternatives offered by the candidates. Location parameters may be based on the mean, the median, or the mode; but since ranked preference ballots provide only ordinal information, the median is the only acceptable statistic.

This can be seen from the diagram, which illustrates two simulated elections with the same candidates but different voter distributions. In both cases the mid-point between the candidates is the 51st percentile of the voter distribution; hence 51% of voters prefer A and 49% prefer B. If we consider a voting method to be correct if it elects the candidate closest to the ''median'' of the voter population, then since the median is necessarily slightly to the left of the 51% line, a voting method will be considered to be correct if it elects A in each case.

The mean of the teal distribution is also slightly to the left of the 51% line, but the mean of the orange distribution is slightly to the right. Hence if we consider a voting method to be correct if it elects the candidate closest to the ''mean'' of the voter population, then a method will not be able to obtain full marks unless it produces different winners from the same ballots in the two elections. Clearly this will impute spurious errors to voting methods. The same problem will arise for any cardinal measure of location; only the median gives consistent results.

The median is not defined for multivariate distributions but the univariate median has a property which generalises conveniently. The median of a distribution is the position whose average distance from all points within the distribution is smallest. This definition generalises to the

The task of a voting system under a spatial model is to identify the candidate whose position most accurately represents the distribution of voter opinions. This amounts to choosing a location parameter for the distribution from the set of alternatives offered by the candidates. Location parameters may be based on the mean, the median, or the mode; but since ranked preference ballots provide only ordinal information, the median is the only acceptable statistic.

This can be seen from the diagram, which illustrates two simulated elections with the same candidates but different voter distributions. In both cases the mid-point between the candidates is the 51st percentile of the voter distribution; hence 51% of voters prefer A and 49% prefer B. If we consider a voting method to be correct if it elects the candidate closest to the ''median'' of the voter population, then since the median is necessarily slightly to the left of the 51% line, a voting method will be considered to be correct if it elects A in each case.

The mean of the teal distribution is also slightly to the left of the 51% line, but the mean of the orange distribution is slightly to the right. Hence if we consider a voting method to be correct if it elects the candidate closest to the ''mean'' of the voter population, then a method will not be able to obtain full marks unless it produces different winners from the same ballots in the two elections. Clearly this will impute spurious errors to voting methods. The same problem will arise for any cardinal measure of location; only the median gives consistent results.

The median is not defined for multivariate distributions but the univariate median has a property which generalises conveniently. The median of a distribution is the position whose average distance from all points within the distribution is smallest. This definition generalises to the geometric median

In geometry, the geometric median of a discrete set of sample points in a Euclidean space is the point minimizing the sum of distances to the sample points. This generalizes the median, which has the property of minimizing the sum of distances ...

in multiple dimensions. The distance is sometimes described as a voter's 'disutility' from a candidate's election, but this identification is purely arbitrary.

If we have a set of candidates and a population of voters, then it is not necessary to solve the computationally difficult problem of finding the geometric median of the voters and then identify the candidate closest to it; instead we can identify the candidate whose average distance from the voters is minimised. This is the metric which has been generally deployed since Merrill onwards;[ see also Green-Armytage and Darlington.][

The candidate closest to the geometric median of the voter distribution may be termed the 'spatial winner'.

]

Evaluation by real elections

Data from real elections can be analysed to compare the effects of different systems, either by comparing between countries or by applying alternative electoral systems to the real election data.

Argument by example

There is a long history of trying to prove the superiority of one voting method over another by constructing examples in which the two methods give different answers, it being triumphantly asserted that the first method is right and the second wrong. Since examples can be constructed which are disadvantageous to all methods, this form of reasoning can be inconclusive. An instance occurs above where we illustrate a weakness in IRV by means of a fictitious election in which the rightful winner would be eliminated in the first round.

A noted recent instance has been given by Donald Saari. He reanalysed an example given by Condorcet of a hypothetical election between 3 candidates with 81 voters whose preferences are as shown in the first table. The Condorcet winner is A, who is preferred to B by 41:40 and to C by 60:21; but the Borda winner is B. Condorcet concluded that the Borda count was at fault.[George G. Szpiro, "Numbers Rule" (2010).] Saari argues that the Borda count is right in this case, noting that the voters can be broken down into 3 groups as shown by the second table.

The pink and blue groups consist of clockwise and anticlockwise cycles which – according to Saari – cancel themselves out, leaving the result to be determined by the white group; and the clear preference of this group (again according to Saari) is for B.

The diagram shows a possible configuration of the voters and candidates consistent with the ballots, with everyone positioned on the circumference of a unit circle. It confirms Saari's judgement, in that A's distance from the average voter is 1.15 whereas B's is 1.09 (and C's is 1.70), making B the spatial winner. But it is only an example. We can imagine holding all positions fixed except for A's, and moving A radially towards the centre of the circle. An infinitesimal step is enough to make A the preference of the cyclical groups, though the white group continues to prefer B. Once A's distance from the centre is less than about 0.89 the overall preference flips from B to A, though the ballots cast would be unchanged.

Thus the election is ambiguous in that equally reasonable spatial representations imply different winners. This is the ambiguity we sought to avoid earlier by adopting a median metric for spatial models; but although the median metric achieves its aim in a single dimension, and generalises attractively to higher dimensions, the property needed to avoid ambiguity does not generalise. In general, cycles may make the spatial winner indeterminate without reference to external facts. The existence of an omnidirectional voter median is a sufficient condition to ensure a determinate result from the ballots cast, and in this case the spatial winner is the Condorcet winner; and unidimensionality of the voter distribution is sufficient for it to have an omnidirectional median.

Saari's example has been influential. Darlington recounts being told by a "reviewer for a very prestigious academic journal" that a similar example shows the Condorcet criterion to be "ridiculous, since a set of votes showing a tie shouldn't change an election's result".

The pink and blue groups consist of clockwise and anticlockwise cycles which – according to Saari – cancel themselves out, leaving the result to be determined by the white group; and the clear preference of this group (again according to Saari) is for B.

The diagram shows a possible configuration of the voters and candidates consistent with the ballots, with everyone positioned on the circumference of a unit circle. It confirms Saari's judgement, in that A's distance from the average voter is 1.15 whereas B's is 1.09 (and C's is 1.70), making B the spatial winner. But it is only an example. We can imagine holding all positions fixed except for A's, and moving A radially towards the centre of the circle. An infinitesimal step is enough to make A the preference of the cyclical groups, though the white group continues to prefer B. Once A's distance from the centre is less than about 0.89 the overall preference flips from B to A, though the ballots cast would be unchanged.

Thus the election is ambiguous in that equally reasonable spatial representations imply different winners. This is the ambiguity we sought to avoid earlier by adopting a median metric for spatial models; but although the median metric achieves its aim in a single dimension, and generalises attractively to higher dimensions, the property needed to avoid ambiguity does not generalise. In general, cycles may make the spatial winner indeterminate without reference to external facts. The existence of an omnidirectional voter median is a sufficient condition to ensure a determinate result from the ballots cast, and in this case the spatial winner is the Condorcet winner; and unidimensionality of the voter distribution is sufficient for it to have an omnidirectional median.

Saari's example has been influential. Darlington recounts being told by a "reviewer for a very prestigious academic journal" that a similar example shows the Condorcet criterion to be "ridiculous, since a set of votes showing a tie shouldn't change an election's result".[

]

Criteria for single-winner elections

Traditionally the merits of different electoral systems have been argued by reference to logical criteria. These have the form of rules of inference

In the philosophy of logic, a rule of inference, inference rule or transformation rule is a logical form consisting of a function which takes premises, analyzes their syntax, and returns a conclusion (or conclusions). For example, the rule of ...

for electoral decisions, licensing the deduction, for instance, that "if ''E'' and ''E'' ' are elections such that ''R'' (''E'',''E'' '), and if ''A'' is the rightful winner of ''E'' , then ''A'' is the rightful winner of ''E'' ' ".

The criteria are as debatable as the voting systems themselves. Here we briefly discuss the considerations advanced concerning their validity, and then summarise the most important criteria, showing in a table which of the principal voting systems satisfy them.

Epistemology of voting criteria

Arguments from example

An example of misbehaviour in a voting system can be generalised to give a criterion which guarantees that no such fault can arise from a system satisfying the criterion, even in more complicated cases. Saari's example gives the Cancellation criterion (which is satisfied by the

An example of misbehaviour in a voting system can be generalised to give a criterion which guarantees that no such fault can arise from a system satisfying the criterion, even in more complicated cases. Saari's example gives the Cancellation criterion (which is satisfied by the Borda count

The Borda count is a family of positional voting rules which gives each candidate, for each ballot, a number of points corresponding to the number of candidates ranked lower. In the original variant, the lowest-ranked candidate gets 0 points, the ...

but violated by all Condorcet systems); the example illustrated of IRV eliminating the rightful winner can be generalised as the Condorcet criterion

An electoral system satisfies the Condorcet winner criterion () if it always chooses the Condorcet winner when one exists. The candidate who wins a majority of the vote in every head-to-head election against each of the other candidatesthat is, a ...

(which is violated by the Borda count).

A more interesting generalisation comes from the class of examples known as 'no-show paradoxes' which can be illustrated from the same diagram. Agreeing that B is the rightful winner, we can hypothesise that under a certain voting system B will indeed be elected if all voters vote sincerely, but that under this system, a single supporter of A can tilt the result towards his preferred candidate by simply abstaining. Most people would agree that this would be an absurd outcome. If we attached importance to it we could generalise it to the Participation criterion

The participation criterion is a voting system criterion. Voting systems that fail the participation criterion are said to exhibit the no show paradox and allow a particularly unusual strategy of tactical voting: abstaining from an election can he ...

, which says that a voter can never help a candidate more by abstaining than by voting.

It is a large step from the example to the criterion. In the example the paradoxical result is simply wrong: B remains the rightful winner when a supporter of A abstains. But when we adopt the Participation criterion, we constrain electoral results in complicated examples in which it is impossible to identify the rightful winner, and with consequences which are hard to predict; this may be more than we bargained for.

The Participation criterion turns out to be surprisingly powerful: it rejects all Condorcet systems while accepting the Borda count. But the no-show paradoxes which arise from Condorcet systems are never examples in which the results are simply wrong, but rather cases in which pairs of results are related in an undesirable way without being determinately right or wrong.

Logical consistency

The widely accepted criteria are mutually inconsistent in various groups (the first of them being the group of 3 incompatible criteria identified by Arrow's impossibility theorem

Arrow's impossibility theorem, the general possibility theorem or Arrow's paradox is an impossibility theorem in social choice theory that states that when voters have three or more distinct alternatives (options), no ranked voting electoral syst ...

). They also contradict all voting systems. Dan Felsenthal described 16 criteria and 18 voting systems and showed "that every one of his 18 systems violates at least six of those criteria".[

]

Result criteria (absolute)

We now turn to the logical criteria themselves, starting with the absolute criteria which state that, if the set of ballots is a certain way, a certain candidate must or must not win.

; Majority criterion

The majority criterion is a single-winner voting system criterion, used to compare such systems. The criterion states that "if one candidate is ranked first by a majority (more than 50%) of voters, then that candidate must win".

Some methods that ...

(MC)

: Will a candidate always win who is ranked as the unique favorite by a majority of voters? This criterion comes in two versions:

; Mutual majority criterion

The mutual majority criterion is a criterion used to compare voting systems. It is also known as the majority criterion for solid coalitions and the generalized majority criterion. The criterion states that if there is a subset S of the candidate ...

(MMC)

: Will a candidate always win who is among a group of candidates ranked above all others by a majority of voters? This also implies the majority loser criterion

The majority loser criterion is a criterion to evaluate single-winner voting systems. The criterion states that if a majority of voters prefers every other candidate over a given candidate, then that candidate must not win.

Either of the Condor ...

if a majority of voters prefers every other candidate over a given candidate, then does that candidate not win? Therefore, of the methods listed, all pass neither or both criteria, except for Borda, which passes Majority Loser while failing Mutual Majority.

; Condorcet criterion

An electoral system satisfies the Condorcet winner criterion () if it always chooses the Condorcet winner when one exists. The candidate who wins a majority of the vote in every head-to-head election against each of the other candidatesthat is, a ...

: Will a candidate always win who beats every other candidate in pairwise comparisons? (This implies the majority criterion, above.)

; Condorcet loser criterion

In single-winner voting system theory, the Condorcet loser criterion (CLC) is a measure for differentiating voting systems. It implies the majority loser criterion but does not imply the Condorcet winner criterion.

A voting system complying wi ...

(cond. loser)

: Will a candidate never win who loses to every other candidate in pairwise comparisons?

Result criteria (relative)

These are criteria that state that, if a certain candidate wins in one circumstance, the same candidate must (or must not) win in a related circumstance.

Ballot-counting criteria

These are criteria which relate to the process of counting votes and determining a winner.

Strategy criteria

These are criteria that relate to a voter's incentive to use certain forms of strategy. They could also be considered as relative result criteria; however, unlike the criteria in that section, these criteria are directly relevant to voters; the fact that a method passes these criteria can simplify the process of figuring out one's optimal strategic vote.

;Later-no-harm criterion

The later-no-harm criterion is a voting system criterion formulated by Douglas Woodall. Woodall defined the criterion as " ding a later preference to a ballot should not harm any candidate already listed." For example, a ranked voting method in w ...

, and later-no-help criterion

: Can voters be sure that adding a later preference to a ballot will not harm or help any candidate already listed?

;No favorite betrayal (NFB)

: Can voters be sure that they do not need to rank any other candidate above their favorite in order to obtain a result they prefer?

Ballot format

These are issues relating to the expressivity or information content of a valid ballot.

;Ballot type

: What information is the voter given on the ballot?

;Equal ranks

: Can a valid ballot express equal support for more than one candidate (and not just equal opposition to more than one)?

;Over 2 ranks

: Can a ballot express more than two levels of support/opposition for different candidates?

Weakness

Note on terminology: A criterion is said to be "weaker" than another when it is passed by more voting methods. Frequently, this means that the conditions for the criterion to apply are stronger. For instance, the majority criterion (MC) is weaker than the multiple majority criterion (MMC), because it requires that a single candidate, rather than a group of any size, should win. That is, any method which passes the MMC also passes the MC, but not vice versa; while any required winner under the MC must win under the MMC, but not vice versa.

Compliance of selected single-winner methods

The following table shows which of the above criteria are met by several single-winner methods.

This table is not comprehensive. For example, Coombs' method

Coombs' method or the Coombs ruleGrofman, Bernard, and Scott L. Feld (2004"If you like the alternative vote (a.k.a. the instant runoff), then you ought to know about the Coombs rule,"''Electoral Studies'' 23:641-59. is a ranked voting system whic ...

is not included.

Additional comparisons of voting criteria are available in the article on the Schulze method

The Schulze method () is an electoral system developed in 1997 by Markus Schulze that selects a single winner using votes that express preferences. The method can also be used to create a sorted list of winners. The Schulze method is also known ...

(a.k.a. beat path). Some data may be duplicated as these tables are work in progress.

Comparison of multi-winner systems

Multi-winner electoral systems seek to produce assemblies representative in a broader sense than that of making the same decisions as would be made by single-winner votes. The New Zealand Royal Commission on the Electoral System

The Royal Commission on the Electoral System was formed in New Zealand in 1985 and reported in 1986. The decision to form the Royal Commission was taken by the Fourth Labour government, after the Labour Party had received more votes, yet it won ...

listed ten criteria for their evaluation of possible new electoral methods for New Zealand. These included fairness between political parties, effective representation of minority or special interest groups, political integration, effective voter participation and legitimacy.

Metrics for multi-winner evaluations

Evaluating the performance of multi-winner voting methods requires different metrics than are used for single-winner systems. The following have been proposed.

* Condorcet Committee Efficiency (CCE) measures the likelihood that a group of elected winners would beat all losers in pairwise races.Loosemore–Hanby index The Loosemore–Hanby index measures disproportionality of electoral systems, how much the principle of one person, one vote is violated. It computes the absolute difference between votes cast and seats obtained using the formula:

:LH=\frac\sum_^n ...

(LH) measure proportionality between seat share and party vote share.

* Unrepresented vote The unrepresented voters are considered the total amount of voters not represented by any party sitting in the legislature in the case of proportional representation. In contrast, the related concept of wasted votes generally applies to plurality vo ...

measures the fraction of electorate not represented by any party

Criterion tables

Compliance of party-based multi-winner methods

Compliance of non-majoritarian party-agnostic multi-winner methods

The following table shows which of the above criteria are met by several multiple winner methods.

Compliance of majoritarian party-agnostic multi-winner methods

The following table shows which of the above criteria are met by several multiple winner methods.

See also

* Ranked voting

The term ranked voting (also known as preferential voting or ranked choice voting) refers to any voting system in which voters rank their candidates (or options) in a sequence of first or second (or third, etc.) on their respective ballots. Ra ...

* Arrow's impossibility theorem

Arrow's impossibility theorem, the general possibility theorem or Arrow's paradox is an impossibility theorem in social choice theory that states that when voters have three or more distinct alternatives (options), no ranked voting electoral syst ...

* Cardinal utility

In economics, a cardinal utility function or scale is a utility index that preserves preference orderings uniquely up to positive affine transformations. Two utility indices are related by an affine transformation if for the value u(x_i) of one i ...

and ordinal utility In economics, an ordinal utility function is a function representing the preferences of an agent on an ordinal scale. Ordinal utility theory claims that it is only meaningful to ask which option is better than the other, but it is meaningless to a ...

* Condorcet paradox

The Condorcet paradox (also known as the voting paradox or the paradox of voting) in social choice theory is a situation noted by the Marquis de Condorcet in the late 18th century, in which collective preferences can be cyclic, even if the prefer ...

Notes

References

{{reflist, 30em

Electoral system criteria

A simulated election can be constructed from a distribution of voters in a suitable space. The illustration shows voters satisfying a bivariate Gaussian distribution centred on O. There are 3 randomly generated candidates, A, B and C. The space is divided into 6 segments by 3 lines, with the voters in each segment having the same candidate preferences. The proportion of voters ordering the candidates in any way is given by the integral of the voter distribution over the associated segment.

The proportions corresponding to the 6 possible orderings of candidates determine the results yielded by different voting systems. Those which elect the best candidate, i.e. the candidate closest to O (who in this case is A), are considered to have given a correct result, and those which elect someone else have exhibited an error. By looking at results for large numbers of randomly generated candidates the empirical properties of voting systems can be measured.

The evaluation protocol outlined here is modelled on the one described by Tideman and Plassmann.

Evaluations of this type are commonest for single-winner electoral systems.

A simulated election can be constructed from a distribution of voters in a suitable space. The illustration shows voters satisfying a bivariate Gaussian distribution centred on O. There are 3 randomly generated candidates, A, B and C. The space is divided into 6 segments by 3 lines, with the voters in each segment having the same candidate preferences. The proportion of voters ordering the candidates in any way is given by the integral of the voter distribution over the associated segment.

The proportions corresponding to the 6 possible orderings of candidates determine the results yielded by different voting systems. Those which elect the best candidate, i.e. the candidate closest to O (who in this case is A), are considered to have given a correct result, and those which elect someone else have exhibited an error. By looking at results for large numbers of randomly generated candidates the empirical properties of voting systems can be measured.

The evaluation protocol outlined here is modelled on the one described by Tideman and Plassmann.

Evaluations of this type are commonest for single-winner electoral systems.  The computation is much more straightforward in a single dimension, which allows an infinite number of voters and an arbitrary number ''m'' of candidates. Results for this simple case are shown in the first table, which is directly comparable with Table 5 (1000 voters, medium dispersion) of the cited paper by Chamberlin and Cohen. The candidates were sampled randomly from the voter distribution and a single Condorcet method ( Minimax) was included in the trials for confirmation.

The relatively poor performance of the

The computation is much more straightforward in a single dimension, which allows an infinite number of voters and an arbitrary number ''m'' of candidates. Results for this simple case are shown in the first table, which is directly comparable with Table 5 (1000 voters, medium dispersion) of the cited paper by Chamberlin and Cohen. The candidates were sampled randomly from the voter distribution and a single Condorcet method ( Minimax) was included in the trials for confirmation.

The relatively poor performance of the  The task of a voting system under a spatial model is to identify the candidate whose position most accurately represents the distribution of voter opinions. This amounts to choosing a location parameter for the distribution from the set of alternatives offered by the candidates. Location parameters may be based on the mean, the median, or the mode; but since ranked preference ballots provide only ordinal information, the median is the only acceptable statistic.

This can be seen from the diagram, which illustrates two simulated elections with the same candidates but different voter distributions. In both cases the mid-point between the candidates is the 51st percentile of the voter distribution; hence 51% of voters prefer A and 49% prefer B. If we consider a voting method to be correct if it elects the candidate closest to the ''median'' of the voter population, then since the median is necessarily slightly to the left of the 51% line, a voting method will be considered to be correct if it elects A in each case.

The mean of the teal distribution is also slightly to the left of the 51% line, but the mean of the orange distribution is slightly to the right. Hence if we consider a voting method to be correct if it elects the candidate closest to the ''mean'' of the voter population, then a method will not be able to obtain full marks unless it produces different winners from the same ballots in the two elections. Clearly this will impute spurious errors to voting methods. The same problem will arise for any cardinal measure of location; only the median gives consistent results.

The median is not defined for multivariate distributions but the univariate median has a property which generalises conveniently. The median of a distribution is the position whose average distance from all points within the distribution is smallest. This definition generalises to the

The task of a voting system under a spatial model is to identify the candidate whose position most accurately represents the distribution of voter opinions. This amounts to choosing a location parameter for the distribution from the set of alternatives offered by the candidates. Location parameters may be based on the mean, the median, or the mode; but since ranked preference ballots provide only ordinal information, the median is the only acceptable statistic.

This can be seen from the diagram, which illustrates two simulated elections with the same candidates but different voter distributions. In both cases the mid-point between the candidates is the 51st percentile of the voter distribution; hence 51% of voters prefer A and 49% prefer B. If we consider a voting method to be correct if it elects the candidate closest to the ''median'' of the voter population, then since the median is necessarily slightly to the left of the 51% line, a voting method will be considered to be correct if it elects A in each case.

The mean of the teal distribution is also slightly to the left of the 51% line, but the mean of the orange distribution is slightly to the right. Hence if we consider a voting method to be correct if it elects the candidate closest to the ''mean'' of the voter population, then a method will not be able to obtain full marks unless it produces different winners from the same ballots in the two elections. Clearly this will impute spurious errors to voting methods. The same problem will arise for any cardinal measure of location; only the median gives consistent results.

The median is not defined for multivariate distributions but the univariate median has a property which generalises conveniently. The median of a distribution is the position whose average distance from all points within the distribution is smallest. This definition generalises to the  The pink and blue groups consist of clockwise and anticlockwise cycles which – according to Saari – cancel themselves out, leaving the result to be determined by the white group; and the clear preference of this group (again according to Saari) is for B.

The diagram shows a possible configuration of the voters and candidates consistent with the ballots, with everyone positioned on the circumference of a unit circle. It confirms Saari's judgement, in that A's distance from the average voter is 1.15 whereas B's is 1.09 (and C's is 1.70), making B the spatial winner. But it is only an example. We can imagine holding all positions fixed except for A's, and moving A radially towards the centre of the circle. An infinitesimal step is enough to make A the preference of the cyclical groups, though the white group continues to prefer B. Once A's distance from the centre is less than about 0.89 the overall preference flips from B to A, though the ballots cast would be unchanged.

Thus the election is ambiguous in that equally reasonable spatial representations imply different winners. This is the ambiguity we sought to avoid earlier by adopting a median metric for spatial models; but although the median metric achieves its aim in a single dimension, and generalises attractively to higher dimensions, the property needed to avoid ambiguity does not generalise. In general, cycles may make the spatial winner indeterminate without reference to external facts. The existence of an omnidirectional voter median is a sufficient condition to ensure a determinate result from the ballots cast, and in this case the spatial winner is the Condorcet winner; and unidimensionality of the voter distribution is sufficient for it to have an omnidirectional median.

Saari's example has been influential. Darlington recounts being told by a "reviewer for a very prestigious academic journal" that a similar example shows the Condorcet criterion to be "ridiculous, since a set of votes showing a tie shouldn't change an election's result".

The pink and blue groups consist of clockwise and anticlockwise cycles which – according to Saari – cancel themselves out, leaving the result to be determined by the white group; and the clear preference of this group (again according to Saari) is for B.

The diagram shows a possible configuration of the voters and candidates consistent with the ballots, with everyone positioned on the circumference of a unit circle. It confirms Saari's judgement, in that A's distance from the average voter is 1.15 whereas B's is 1.09 (and C's is 1.70), making B the spatial winner. But it is only an example. We can imagine holding all positions fixed except for A's, and moving A radially towards the centre of the circle. An infinitesimal step is enough to make A the preference of the cyclical groups, though the white group continues to prefer B. Once A's distance from the centre is less than about 0.89 the overall preference flips from B to A, though the ballots cast would be unchanged.

Thus the election is ambiguous in that equally reasonable spatial representations imply different winners. This is the ambiguity we sought to avoid earlier by adopting a median metric for spatial models; but although the median metric achieves its aim in a single dimension, and generalises attractively to higher dimensions, the property needed to avoid ambiguity does not generalise. In general, cycles may make the spatial winner indeterminate without reference to external facts. The existence of an omnidirectional voter median is a sufficient condition to ensure a determinate result from the ballots cast, and in this case the spatial winner is the Condorcet winner; and unidimensionality of the voter distribution is sufficient for it to have an omnidirectional median.

Saari's example has been influential. Darlington recounts being told by a "reviewer for a very prestigious academic journal" that a similar example shows the Condorcet criterion to be "ridiculous, since a set of votes showing a tie shouldn't change an election's result".

An example of misbehaviour in a voting system can be generalised to give a criterion which guarantees that no such fault can arise from a system satisfying the criterion, even in more complicated cases. Saari's example gives the Cancellation criterion (which is satisfied by the

An example of misbehaviour in a voting system can be generalised to give a criterion which guarantees that no such fault can arise from a system satisfying the criterion, even in more complicated cases. Saari's example gives the Cancellation criterion (which is satisfied by the