The Colony of Virginia, chartered in 1606 and settled in 1607, was the first enduring

English colony in

North America, following failed attempts at settlement on

Newfoundland by

Sir Humphrey Gilbert

Sir Humphrey Gilbert (c. 1539 – 9 September 1583) was an English adventurer, explorer, member of parliament and soldier who served during the reign of Queen Elizabeth I and was a pioneer of the English colonial empire in North America ...

[Gilbert (Saunders Family), Sir Humphrey" (history), ''Dictionary of Canadian Biography'' Online, ]University of Toronto

The University of Toronto (UToronto or U of T) is a public university, public research university in Toronto, Ontario, Canada, located on the grounds that surround Queen's Park (Toronto), Queen's Park. It was founded by royal charter in 1827 ...

, May 2, 2005 in 1583 and the

colony of Roanoke

The establishment of the Roanoke Colony ( ) was an attempt by Sir Walter Raleigh to found the first permanent English settlement in North America. The English, led by Sir Humphrey Gilbert, had briefly claimed St. John's, Newfoundland, in ...

(further south, in modern eastern

North Carolina

North Carolina () is a state in the Southeastern region of the United States. The state is the 28th largest and 9th-most populous of the United States. It is bordered by Virginia to the north, the Atlantic Ocean to the east, Georgia and ...

) by

Sir Walter Raleigh in the late 1580s.

The founder of the new colony was the

Virginia Company

The Virginia Company was an English trading company chartered by King James I on 10 April 1606 with the object of colonizing the eastern coast of America. The coast was named Virginia, after Elizabeth I, and it stretched from present-day Mai ...

,

with the first two settlements in

Jamestown on the north bank of the

James River and

Popham Colony

The Popham Colony—also known as the Sagadahoc Colony—was a short-lived English colonial settlement in North America. It was established in 1607 by the proprietary Plymouth Company and was located in the present-day town of Phippsburg, Ma ...

on the

Kennebec River in modern-day

Maine

Maine () is a state in the New England and Northeastern regions of the United States. It borders New Hampshire to the west, the Gulf of Maine to the southeast, and the Canadian provinces of New Brunswick and Quebec to the northeast and ...

, both in 1607. The Popham colony quickly failed due to

a famine, disease, and conflicts with local Native American tribes in the first two years. Jamestown occupied land belonging to the

Powhatan Confederacy

The Powhatan people (; also spelled Powatan) may refer to any of the indigenous Algonquian people that are traditionally from eastern Virginia. All of the Powhatan groups descend from the Powhatan Confederacy. In some instances, The Powhata ...

, and was also at the brink of failure before the arrival of a new group of settlers and supplies by ship in 1610.

Tobacco

Tobacco is the common name of several plants in the genus '' Nicotiana'' of the family Solanaceae, and the general term for any product prepared from the cured leaves of these plants. More than 70 species of tobacco are known, but the ...

became Virginia's first profitable export, the production of which had a significant impact on the society and settlement patterns.

In 1624, the Virginia Company's charter was revoked by

King James I

James VI and I (James Charles Stuart; 19 June 1566 – 27 March 1625) was King of Scotland as James VI from 24 July 1567 and King of England and Ireland as James I from the union of the Scottish and English crowns on 24 March 1603 until hi ...

, and the Virginia colony was transferred to royal authority as a

crown colony. After the

English Civil War

The English Civil War (1642–1651) was a series of civil wars and political machinations between Parliamentarians (" Roundheads") and Royalists led by Charles I ("Cavaliers"), mainly over the manner of England's governance and issues of re ...

in the 1640s and 50s, the Virginia colony was nicknamed "The Old Dominion" by

King Charles II for its perceived loyalty to the English monarchy during the era of the Protectorate and

Commonwealth of England

The Commonwealth was the political structure during the period from 1649 to 1660 when England and Wales, later along with Ireland and Scotland, were governed as a republic after the end of the Second English Civil War and the trial and execu ...

.

From 1619 to 1775/1776, the colonial legislature of Virginia was the General Assembly, which governed in conjunction with

a colonial governor. Jamestown on the James River remained the capital of the Virginia colony until 1699; from 1699 until its dissolution the capital was in

Williamsburg. The colony experienced its first major political turmoil with

Bacon's Rebellion

Bacon's Rebellion was an armed rebellion held by Virginia settlers that took place from 1676 to 1677. It was led by Nathaniel Bacon against Colonial Governor William Berkeley, after Berkeley refused Bacon's request to drive Native American ...

of 1676.

After declaring independence from the

Kingdom of Great Britain

The Kingdom of Great Britain (officially Great Britain) was a Sovereign state, sovereign country in Western Europe from 1 May 1707 to the end of 31 December 1800. The state was created by the 1706 Treaty of Union and ratified by the Acts of ...

in 1775, before the

Declaration of Independence

A declaration of independence or declaration of statehood or proclamation of independence is an assertion by a polity in a defined territory that it is independent and constitutes a state. Such places are usually declared from part or all of th ...

was officially adopted, the Virginia colony became the

Commonwealth of Virginia

Virginia, officially the Commonwealth of Virginia, is a state in the Mid-Atlantic and Southeastern regions of the United States, between the Atlantic Coast and the Appalachian Mountains. The geography and climate of the Commonwealth are ...

, one of the original

thirteen states of the United States, adopting as its official slogan "The Old Dominion". The entire modern states of

West Virginia

West Virginia is a state in the Appalachian, Mid-Atlantic and Southeastern regions of the United States.The Census Bureau and the Association of American Geographers classify West Virginia as part of the Southern United States while the B ...

,

Kentucky

Kentucky ( , ), officially the Commonwealth of Kentucky, is a state in the Southeastern region of the United States and one of the states of the Upper South. It borders Illinois, Indiana, and Ohio to the north; West Virginia and Virginia ...

,

Indiana

Indiana () is a U.S. state in the Midwestern United States. It is the 38th-largest by area and the 17th-most populous of the 50 States. Its capital and largest city is Indianapolis. Indiana was admitted to the United States as the 19th s ...

and

Illinois

Illinois ( ) is a state in the Midwestern United States. Its largest metropolitan areas include the Chicago metropolitan area, and the Metro East section, of Greater St. Louis. Other smaller metropolitan areas include, Peoria and Rockf ...

, and portions of

Ohio

Ohio () is a state in the Midwestern region of the United States. Of the fifty U.S. states, it is the 34th-largest by area, and with a population of nearly 11.8 million, is the seventh-most populous and tenth-most densely populated. The sta ...

and

Western Pennsylvania were later created from the territory encompassed, or claimed by, the colony of Virginia at the time of further American independence in July 1776.

Names and etymology

Virginia

The name "Virginia" is the oldest designation for English claims in North America. In 1584,

Sir Walter Raleigh sent Philip Amadas and Arthur Barlowe to explore what is now the

North Carolina

North Carolina () is a state in the Southeastern region of the United States. The state is the 28th largest and 9th-most populous of the United States. It is bordered by Virginia to the north, the Atlantic Ocean to the east, Georgia and ...

coast, and they returned with word of a regional king (''

weroance

Weroance is an Algonquian word meaning leader or commander among the Powhatan confederacy of the Virginia coast and Chesapeake Bay region. Weroances were under a paramount chief called Powhatan. The Powhatan Confederacy, encountered by the coloni ...

'') named ''Wingina'', who ruled a land supposedly called ''Wingandacoa''.

The name Virginia for a region in North America may have been originally suggested by

Sir Walter Raleigh, who named it for

Queen Elizabeth I, in approximately 1584. In addition, the term ''Wingandacoa'' may have influenced the name Virginia." On his next voyage, Raleigh learned that while the chief of the Secotans was indeed called

Wingina

Wingina ( – 1 June 1586), also known as Pemisapan, was a Secotan weroance who was the first Native American leader to be encountered by English colonists in North America. During the late 16th century, English explorers Philip Amadas and Arth ...

, the expression ''wingandacoa'' heard by the English upon arrival actually meant "What good clothes you wear!" in

Carolina Algonquian, and was not the name of the country as previously misunderstood.

"Virginia" was originally a term used to refer to North America's entire eastern coast from the

34th parallel (close to

Cape Fear) north to

45th parallel. This area included a large section of Canada and the shores of

Acadia

Acadia (french: link=no, Acadie) was a colony of New France in northeastern North America which included parts of what are now the The Maritimes, Maritime provinces, the Gaspé Peninsula and Maine to the Kennebec River. During much of the 17t ...

.

The colony was also known as the Virginia Colony, the Province of Virginia, and occasionally as the Dominion and Colony of Virginia or His Majesty's Most Ancient Colloney

icand Dominion of Virginia

Old Dominion

It is said, according to tradition, that in gratitude for the loyalty of Virginians to the crown during the

English Civil War

The English Civil War (1642–1651) was a series of civil wars and political machinations between Parliamentarians (" Roundheads") and Royalists led by Charles I ("Cavaliers"), mainly over the manner of England's governance and issues of re ...

,

Charles II gave it the title of "Old Dominion". The colony seal stated from Latin (en dat virginia quartam), in English 'Behold, Virginia gives the fourth', with Virginia claimed as the fourth English dominion after England,

France

France (), officially the French Republic ( ), is a country primarily located in Western Europe. It also comprises of overseas regions and territories in the Americas and the Atlantic, Pacific and Indian Oceans. Its metropolitan area ...

,

Scotland

Scotland (, ) is a Countries of the United Kingdom, country that is part of the United Kingdom. Covering the northern third of the island of Great Britain, mainland Scotland has a Anglo-Scottish border, border with England to the southeast ...

and

Ireland

Ireland ( ; ga, Éire ; Ulster Scots dialect, Ulster-Scots: ) is an island in the Atlantic Ocean, North Atlantic Ocean, in Northwestern Europe, north-western Europe. It is separated from Great Britain to its east by the North Channel (Grea ...

.

The state of

Virginia

Virginia, officially the Commonwealth of Virginia, is a state in the Mid-Atlantic and Southeastern regions of the United States, between the Atlantic Coast and the Appalachian Mountains. The geography and climate of the Commonwealth ar ...

maintains "Old Dominion" as its

state nickname. The athletic teams of the

University of Virginia

The University of Virginia (UVA) is a public research university in Charlottesville, Virginia. Founded in 1819 by Thomas Jefferson, the university is ranked among the top academic institutions in the United States, with highly selective ad ...

are known as the "

Cavaliers," referring to supporters of Charles II, and Virginia has another state public university called "

Old Dominion University

Old Dominion University (Old Dominion or ODU) is a public research university in Norfolk, Virginia. It was established in 1930 as the Norfolk Division of the College of William & Mary and is now one of the largest universities in Virginia w ...

".

History

Although Spain, France, Sweden, and the Netherlands all had competing claims to the region, none of these prevented the English from becoming the first European power to colonize successfully the

Mid-Atlantic coastline. Earlier attempts had been made by the Spanish in what is now Georgia (

San Miguel de Gualdape

San Miguel de Gualdape (sometimes San Miguel de Guadalupe) is a former Spanish colony in present-day Georgetown County, South Carolina, founded in 1526 by Lucas Vázquez de Ayllón.In early 1521, Ponce de León had made a poorly documented, disas ...

, 1526–27; several

Spanish missions in Georgia

The Spanish missions in Georgia comprised a series of religious outposts established by Spanish Catholics in order to spread the Christian doctrine among the Guale and various Timucua peoples in southeastern Georgia.

Beginning in the second h ...

between 1568 and 1684), South Carolina (

Santa Elena, 1566–87), North Carolina (

Joara

Joara was a large Native American settlement, a regional chiefdom of the Mississippian culture, located in what is now Burke County, North Carolina, about 300 miles from the Atlantic coast in the foothills of the Blue Ridge Mountains. Joara is n ...

, 1567–68) and Virginia (

Ajacán Mission, 1570–71); and by the French in South Carolina (

Charlesfort, 1562–63). Farther south, the Spanish colony of

Spanish Florida, centered on

St. Augustine, was established in 1565, while to the north, the French were establishing settlements in what is now Canada (

Charlesbourg-Royal briefly occupied 1541–43;

Port Royal, established in 1605).

Elizabethan colonization attempts in the New World (1584–1590)

In 1585, Sir

Walter Raleigh sent his first colonisation mission to the island of

Roanoke (in present-day

North Carolina

North Carolina () is a state in the Southeastern region of the United States. The state is the 28th largest and 9th-most populous of the United States. It is bordered by Virginia to the north, the Atlantic Ocean to the east, Georgia and ...

), with over 100 male settlers. However, when

Sir Francis Drake arrived at the colony in summer 1586, the colonists opted to return to England, due to lack of supply ships, abandoning the colony. Supply ships arrived at the now-abandoned colony later in 1586; 15 soldiers were left behind to hold the island, but no trace of these men was later found.

In 1587, Raleigh sent another group to again attempt to establish a permanent settlement. The expedition leader,

John White, returned to England for supplies that same year but was unable to return to the colony due to war between England and Spain. When he finally did return in 1590, he found the colony abandoned. The houses were intact, but the colonists had completely disappeared. Although there are a number of theories about the fate of the colony, it remains a mystery and has come to be known as the

"Lost Colony". Two English children were born in this colony; the first was named

Virginia Dare

Virginia Dare (born August 18, 1587, in Roanoke Colony, date of death unknown) was the first English child born in a New World English colony.

What became of Virginia and the other colonists remains a mystery. The fact of her birth is known bec ...

–

Dare County, North Carolina

Dare County is the easternmost county in the U.S. state of North Carolina. As of the 2020 census, the population was 36,915. Its county seat is Manteo. Dare County is named after Virginia Dare, the first child born in the Americas to English p ...

, was named in honor of the baby, who was among those whose fate is unknown. The word ''

Croatoan'' was found carved into a tree, the name of a tribe on a nearby island.

Virginia Company (1606–1624)

Following the failure of the previous colonisation attempts, England resumed attempts to set up a number of colonies. This time joint-stock companies were used rather than giving extensive grants to a landed proprietor such as Gilbert or Raleigh.

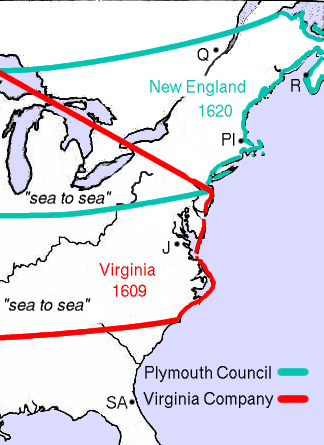

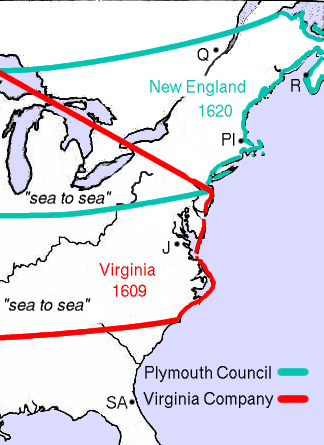

Charter of 1606 – creation of London and Plymouth companies

King James granted a proprietary

charter to two competing branches of the

Virginia Company

The Virginia Company was an English trading company chartered by King James I on 10 April 1606 with the object of colonizing the eastern coast of America. The coast was named Virginia, after Elizabeth I, and it stretched from present-day Mai ...

, which were supported by investors. These were the

Plymouth Company and the

London Company.

By the terms of the charter, the Plymouth Company was permitted to establish a colony of square between the

38th parallel and the

45th parallel (roughly between

Chesapeake Bay

The Chesapeake Bay ( ) is the largest estuary in the United States. The Bay is located in the Mid-Atlantic region and is primarily separated from the Atlantic Ocean by the Delmarva Peninsula (including the parts: the Eastern Shore of Maryland / ...

and the current U.S.–Canada border). The London Company was permitted to establish between the

34th parallel and the

41st parallel (approximately between

Cape Fear and

Long Island Sound), and also owned a large portion of Atlantic and Inland Canada. In the area of overlap, the two companies were not permitted to establish colonies within one hundred miles of each other.

During 1606, each company organized expeditions to establish settlements within the area of their rights.

The London company formed Jamestown in its exclusive territory, whilst the Plymouth company formed the

Popham Colony

The Popham Colony—also known as the Sagadahoc Colony—was a short-lived English colonial settlement in North America. It was established in 1607 by the proprietary Plymouth Company and was located in the present-day town of Phippsburg, Ma ...

in its exclusive territory near what is now Phippsburg, Maine.

Jamestown and the London company

The London Company hired Captain

Christopher Newport to lead its expedition. On December 20, 1606, he set sail from England with his

flagship, the ''

Susan Constant

''Susan Constant'', possibly ''Sarah Constant'', captained by Christopher Newport, was the largest of three ships of the English Virginia Company (the others being ''Discovery'' and '' Godspeed'') on the 1606–1607 voyage that resulted in the fo ...

'', and two smaller ships, the ''

Godspeed'', and the

''Discovery'', with 105 men and boys, plus 39 sailors. After an unusually long voyage of 144 days, they arrived at the mouth of the Chesapeake Bay and came ashore at the point where the southern side of the bay meets the Atlantic Ocean, an event that has come to be called the "First Landing". They erected a cross and named the point of land

Cape Henry, in honor of

Henry Frederick, Prince of Wales, the eldest son of King James.

Their instructions were to select a location inland along a waterway where they would be less vulnerable to the Spanish or other Europeans also seeking to establish colonies. They sailed westward into the Bay and reached the mouth of

Hampton Roads, stopping at a location now known as

Old Point Comfort

Old Point Comfort is a point of land located in the independent city of Hampton, Virginia. Previously known as Point Comfort, it lies at the extreme tip of the Virginia Peninsula at the mouth of Hampton Roads in the United States. It was renamed ...

. Keeping the shoreline to their right, they then ventured up the largest river, which they named the

James, for their king. After exploring at least as far upriver as the confluence of the

Appomattox River at present-day

Hopewell, they returned downstream to

Jamestown Island

Jamestown Island is a island in the James River in Virginia, part of James City County. It is located off Glasshouse Point, to which it is connected via a causeway to the Colonial Parkway. Much of the island is wetland, including both swamp and ...

, which offered a favorable defensive position against enemy ships and deep water anchorage adjacent to the land. Within two weeks they had constructed their first fort and named their settlement

Jamestown.

In addition to securing gold and other precious minerals to send back to the waiting investors in England, the survival plan for the Jamestown colonists depended upon regular supplies from England and trade with the

Native Americans. The location they selected was largely cut off from the mainland and offered little game for hunting, no natural fresh drinking water, and very limited ground for farming. Captain Newport returned to England twice, delivering the

First and Second Supply missions during 1608, and leaving the ''Discovery'' for the use of the colonists. However, death from disease and conflicts with the Natives Americans took a fearsome toll on the colonists. Despite attempts at mining minerals, growing silk, and exporting the native Virginia tobacco, no profitable exports had been identified, and it was unclear whether the settlement would survive financially.

Powhatan Confederacy

The

Powhatan Confederacy

The Powhatan people (; also spelled Powatan) may refer to any of the indigenous Algonquian people that are traditionally from eastern Virginia. All of the Powhatan groups descend from the Powhatan Confederacy. In some instances, The Powhata ...

was a

confederation of numerous linguistically related tribes in the eastern part of Virginia. The Powhatan Confederacy controlled a territory known as

Tsenacommacah

Tsenacommacah (pronounced in English; "densely inhabited land"; also written Tscenocomoco, Tsenacomoco, Tenakomakah, Attanoughkomouck, and Attan-Akamik) is the name given by the Powhatan people to their native homeland, the area encompassing all ...

, which roughly corresponded with the

Tidewater region

Tidewater refers to the north Atlantic coastal plain region of the United States of America.

Definition

Culturally, the Tidewater region usually includes the low-lying plains of southeast Virginia, northeastern North Carolina, southern Mary ...

of Virginia. It was in this territory that the English established Jamestown. At the time of the English arrival, the Powhatan were led by the

paramount chief

A paramount chief is the English-language designation for the highest-level political leader in a regional or local polity or country administered politically with a chief-based system. This term is used occasionally in anthropological and ar ...

Wahunsenacawh

Powhatan (Wiktionary:circa, c. 1547 – c. 1618), whose proper name was Wahunsenacawh (alternately spelled Wahunsenacah, Wahunsunacock or Wahunsonacock), was the leader of the Powhatan, an alliance of Algonquian languages, Algonquian-speaking Na ...

.

Popham colony and Plymouth company

On May 31, 1607, about 100 men and boys left England for what is now

Maine

Maine () is a state in the New England and Northeastern regions of the United States. It borders New Hampshire to the west, the Gulf of Maine to the southeast, and the Canadian provinces of New Brunswick and Quebec to the northeast and ...

. Approximately three months later, the group landed on a wooded peninsula where the Kennebec River meets the Atlantic Ocean and began building Fort St. George. By the end of the year, due to limited resources, half of the colonists returned to England. Late the next year, the remaining 45 sailed home, and the Plymouth company fell dormant.

Charter of 1609 – the London company expands

In 1609, with the abandonment of the Plymouth Company settlement, the London Company's Virginia charter was adjusted to include the territory north of the

34th parallel and south of the

39th parallel, with its original coastal grant extended "from sea to sea". Thus, at least according to James I's writ, the Virginia Colony in its original sense extended to the coast of the Pacific Ocean, in what is now California, with all the states in between (

Kentucky

Kentucky ( , ), officially the Commonwealth of Kentucky, is a state in the Southeastern region of the United States and one of the states of the Upper South. It borders Illinois, Indiana, and Ohio to the north; West Virginia and Virginia ...

,

Missouri

Missouri is a state in the Midwestern region of the United States. Ranking 21st in land area, it is bordered by eight states (tied for the most with Tennessee): Iowa to the north, Illinois, Kentucky and Tennessee to the east, Arkansas t ...

,

Colorado

Colorado (, other variants) is a state in the Mountain states, Mountain West subregion of the Western United States. It encompasses most of the Southern Rocky Mountains, as well as the northeastern portion of the Colorado Plateau and the wes ...

,

Utah

Utah ( , ) is a state in the Mountain West subregion of the Western United States. Utah is a landlocked U.S. state bordered to its east by Colorado, to its northeast by Wyoming, to its north by Idaho, to its south by Arizona, and to it ...

, etc.) belonging to Virginia. For practical purposes, though, the colonists rarely ventured far inland to what was known as "The Virginia Wilderness", although the concept itself helped renew the interest of investors, and additional funds enabled an expanded effort, known as the

Third Supply The Jamestown supply missions were a series of fleets (or sometimes individual ships) from 1607 to around 1611 that were dispatched from England by the London Company (also known as the Virginia Company of London) with the specific goal of initially ...

.

1609 Third Supply and Bermuda

For the Third Supply, the London Company had a new ship built. The ''

Sea Venture

''Sea Venture'' was a seventeenth-century English sailing ship, part of the Third Supply mission to the Jamestown Colony, that was wrecked in Bermuda in 1609. She was the 300 ton purpose-built flagship of the London Company and a highly unusual ...

'' was specifically designed for emigration of additional colonists and transporting supplies. It became the

flagship of the Admiral of the convoy, Sir

George Somers

Sir George Somers (before 24 April 1554 – 9 November 1610) was an English privateer and naval hero, knighted for his achievements and the Admiral of the Virginia Company of London. He achieved renown as part of an expedition led b ...

. The Third Supply was the largest to date, with eight other ships joining the ''Sea Venture''. The new Captain of the ''Sea Venture'' was the mission's Vice-Admiral, Christopher Newport. Hundreds of new colonists were aboard the ships. However, weather was to drastically affect the mission.

A few days out of London, the nine ships of the third supply mission encountered a massive hurricane in the Atlantic Ocean. They became separated during the three days the storm lasted. Admiral Somers had the new ''Sea Venture'', carrying most of the supplies of the mission, deliberately driven aground onto the reefs of

Bermuda

)

, anthem = "God Save the King"

, song_type = National song

, song = "Hail to Bermuda"

, image_map =

, map_caption =

, image_map2 =

, mapsize2 =

, map_caption2 =

, subdivision_type = Sovereign state

, subdivision_name =

, es ...

to avoid sinking. However, while there was no loss of life, the ship was wrecked beyond repair, stranding its survivors on the uninhabited

archipelago

An archipelago ( ), sometimes called an island group or island chain, is a chain, cluster, or collection of islands, or sometimes a sea containing a small number of scattered islands.

Examples of archipelagos include: the Indonesian Arc ...

, to which they laid claim for England.

The survivors at Bermuda eventually built two smaller ships and most of them continued on to Jamestown, leaving a few on Bermuda to secure the claim. The Company's possession of Bermuda was made official in 1612, when the third and final charter extended the boundaries of 'Virginia' far enough out to sea to encompass Bermuda. Bermuda has since been known officially also as ''The Somers Isles'' (in commemoration of Admiral Somers). The shareholders of the Virginia Company spun off a second company, the

Somers Isles Company

The Somers Isles Company (fully, the Company of the City of London for the Plantacion of The Somers Isles or the Company of The Somers Isles) was formed in 1615 to operate the English colony of the Somers Isles, also known as Bermuda, as a commerc ...

, which administered Bermuda from 1615 to 1684.

Upon their arrival at Jamestown, the survivors of the ''Sea Venture'' discovered that the 10-month delay had greatly aggravated other adverse conditions. Seven of the other ships had arrived carrying more colonists, but little in the way of food and supplies. Combined with a drought, and hostile relations with the

Native Americans, the loss of the supplies that had been aboard the ''Sea Venture'' resulted in the

Starving Time

The Starving Time at Jamestown in the Colony of Virginia was a period of starvation during the winter of 1609–1610. There were about 500 Jamestown residents at the beginning of the winter. However, there were only 61 people still alive when the ...

in late 1609 to May 1610, during which over 80% of the colonists perished. Conditions were so adverse it appears, from skeletal evidence, that the survivors engaged in cannibalism. The survivors from Bermuda had brought few supplies and food with them, and it appeared to all that Jamestown must be abandoned and it would be necessary to return to England.

Abandonment and Fourth supply

Samuel Argall was the captain of one of the seven ships of the Third Supply that had arrived at Jamestown in 1609 after becoming separated from the ''Sea Venture'', whose fate was unknown. Depositing his passengers and limited supplies, he returned to England with word of the plight of the colonists at Jamestown. The King authorized another leader,

Thomas West, 3rd Baron De La Warr

Thomas West, 3rd Baron De La Warr ( ; 9 July 1577 – 7 June 1618), was an English merchant and politician, for whom the bay, the river, and, consequently, a Native American people and U.S. state, all later called "Delaware", were named. He wa ...

, later better known as "Lord Delaware", to have greater powers, and the London Company organized another supply mission. They set sail from London on April 1, 1610.

Just after the survivors of the Starving Time and those who had joined them from Bermuda had abandoned Jamestown, the ships of the new supply mission sailed up the James River with food, supplies, a doctor, and more colonists. Lord Delaware was determined that the colony was to survive, and he intercepted the departing ships about downstream of Jamestown. The colonists thanked

Providence for the Colony's salvation.

West proved far harsher and more belligerent toward the Indians than any of his predecessors, engaging in wars of conquest against them. He first sent Gates to drive off the Kecoughtan from their village on July 9, 1610, then gave Chief Powhatan an ultimatum to either return all English subjects and property, or face war. Powhatan responded by insisting that the English either stay in their fort or leave Virginia. Enraged, De la Warr had the hand of a

Paspahegh

The Paspahegh tribe was a Native American tributary to the Powhatan paramount chiefdom, incorporated into the chiefdom around 1596 or 1597. The Paspahegh Indian tribe lived in present-day Charles City and James City counties, Virginia. The Po ...

captive cut off and sent him to the paramount chief with another ultimatum: Return all English subjects and property, or the neighboring villages would be burned. This time, Powhatan did not even respond.

First Anglo-Powhatan War (1610–1614), John Rolfe and Pocahontas

On August 9, 1610, tired of waiting for a response from Powhatan, West sent George Percy with 70 men to attack the Paspahegh capital, burning the houses and cutting down their cornfields. They killed 65 to 75, and captured one of Wowinchopunk's wives and her children. Returning downstream, the English threw the children overboard and shot out "their Braynes in the water". The queen was put to the sword in Jamestown. The Paspahegh never recovered from this attack and abandoned their town. Another small force sent with Samuel Argall against the Warraskoyaks found that they had already fled, but he destroyed their abandoned village and cornfields as well. This event triggered the first Anglo-Powhatan War.

Among the individuals who had briefly abandoned Jamestown was

John Rolfe

John Rolfe (1585 – March 1622) was one of the early English settlers of North America. He is credited with the first successful cultivation of tobacco as an export crop in the Colony of Virginia in 1611.

Biography

John Rolfe is believed ...

, a ''Sea Venture'' survivor who had lost his wife and son in Bermuda. He was a businessman from London who had some untried seeds for new, sweeter strains of

tobacco

Tobacco is the common name of several plants in the genus '' Nicotiana'' of the family Solanaceae, and the general term for any product prepared from the cured leaves of these plants. More than 70 species of tobacco are known, but the ...

with him, as well as some untried marketing ideas. It would turn out that John Rolfe held the key to the Colony's economic success. By 1612, Rolfe's new strains of tobacco had been successfully cultivated and exported, establishing a first

cash crop for

export

An export in international trade is a good produced in one country that is sold into another country or a service provided in one country for a national or resident of another country. The seller of such goods or the service provider is an ...

.

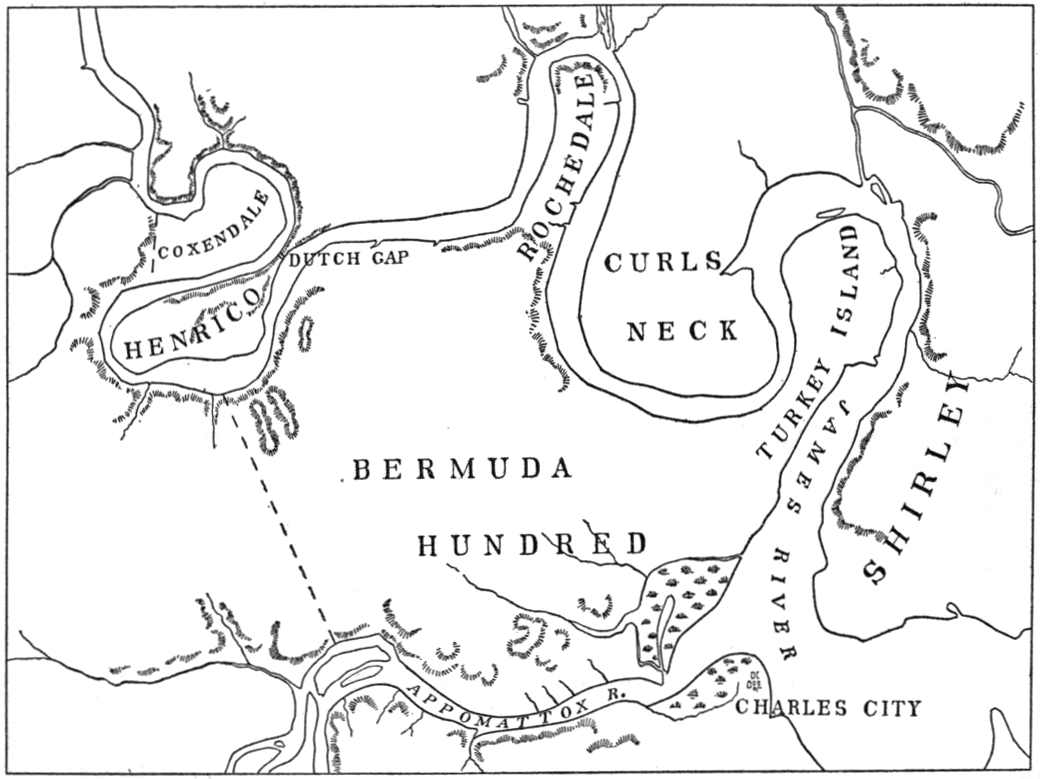

Plantations and new outposts sprung up starting with

Henricus

The "Citie of Henricus"—also known as Henricopolis, Henrico Town or Henrico—was a settlement in Virginia founded by Sir Thomas Dale in 1611 as an alternative to the swampy and dangerous area around the original English settlement at Jamest ...

, initially both upriver and downriver along the navigable portion of the James, and thereafter along the other rivers and waterways of the area. The settlement at Jamestown could finally be considered permanently established.

A period of peace followed the marriage in 1614 of colonist John Rolfe to

Pocahontas

Pocahontas (, ; born Amonute, known as Matoaka, 1596 – March 1617) was a Native American woman, belonging to the Powhatan people, notable for her association with the colonial settlement at Jamestown, Virginia. She was the daughter of ...

, the daughter of Algonquian

chief Powhatan

Powhatan ( c. 1547 – c. 1618), whose proper name was Wahunsenacawh (alternately spelled Wahunsenacah, Wahunsunacock or Wahunsonacock), was the leader of the Powhatan, an alliance of Algonquian-speaking Native Americans living in Tsenacommaca ...

.

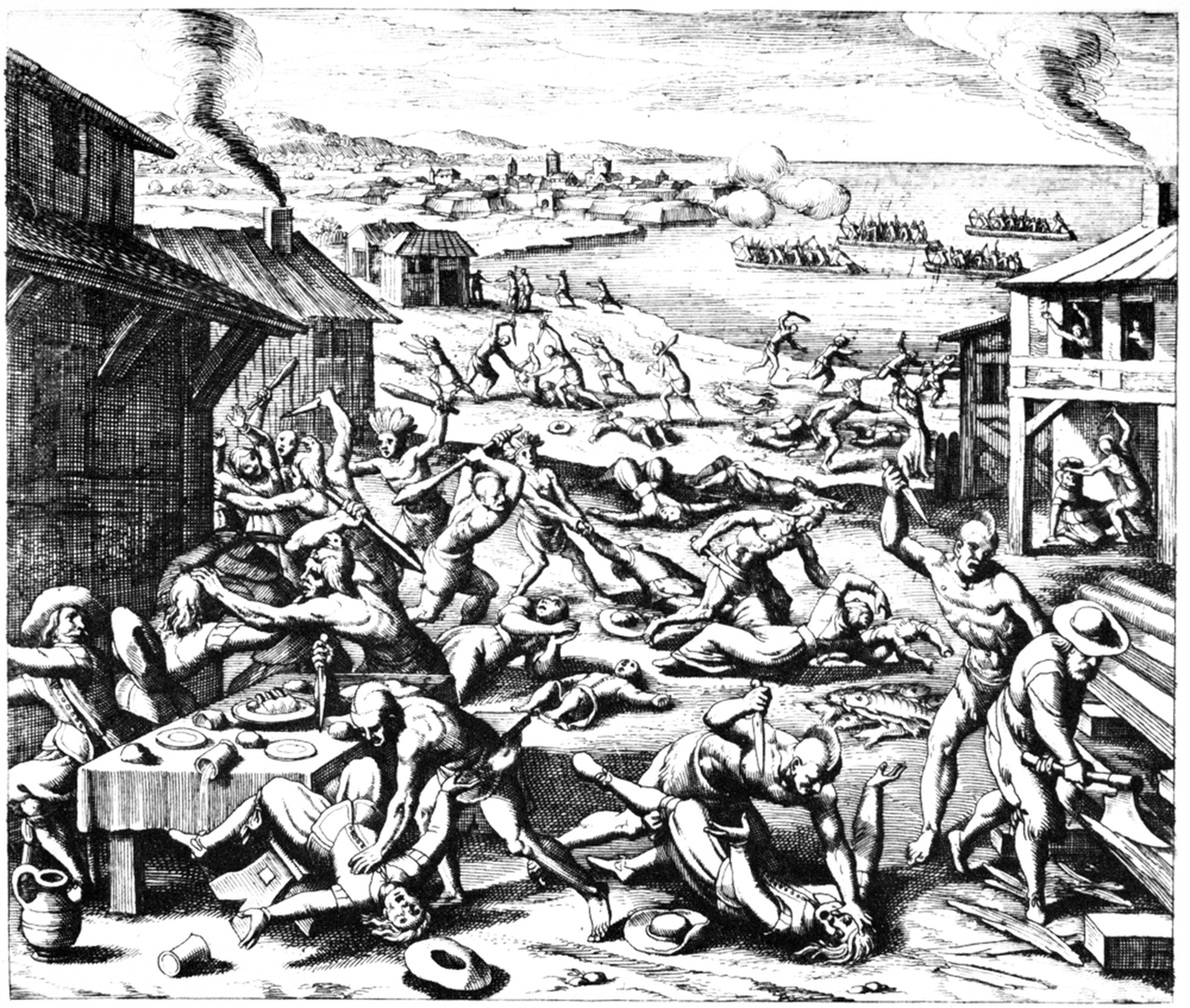

Second Anglo-Powhatan War (1622–1632)

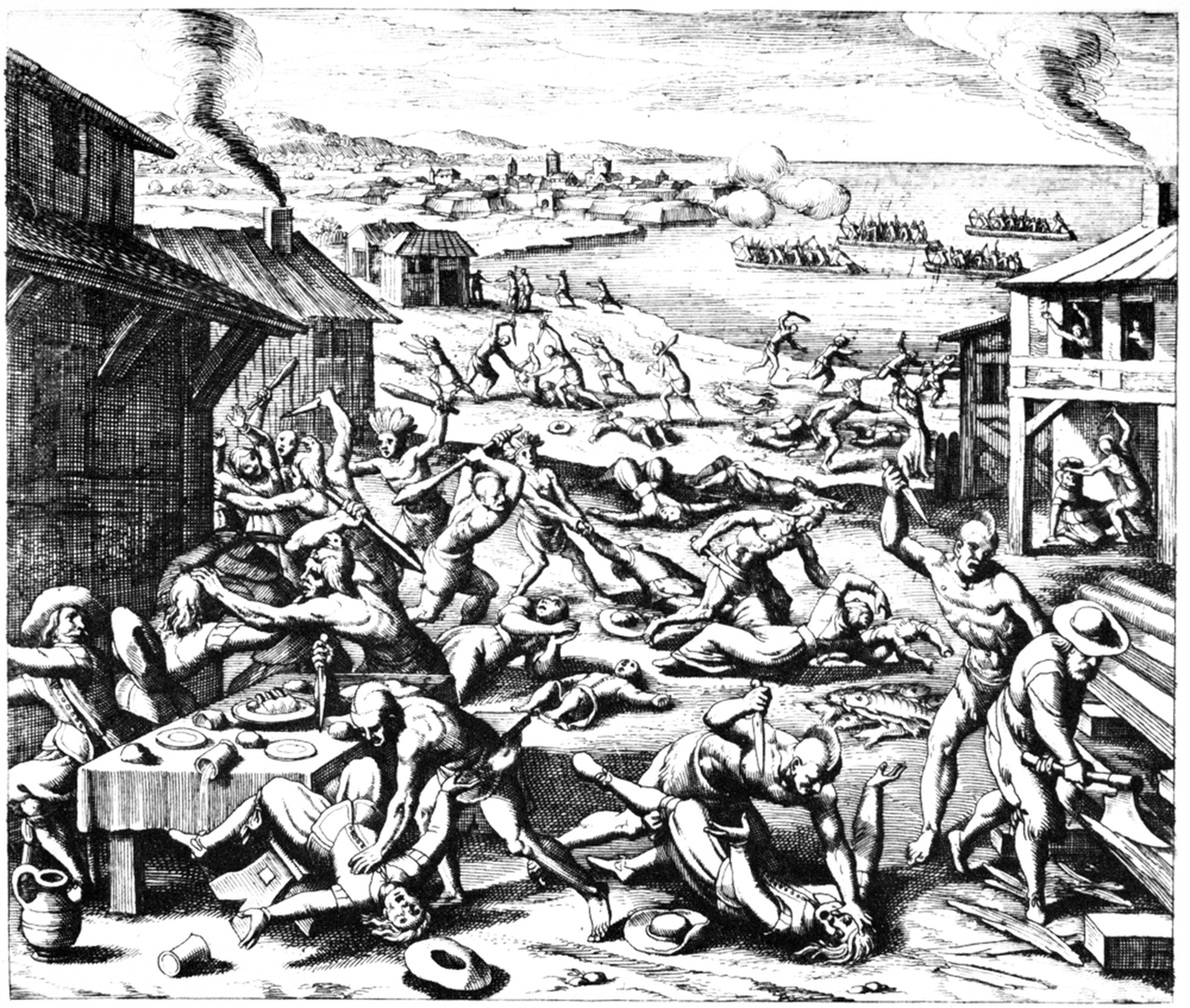

= Indian Massacre of 1622

=

The relations with the Natives took a turn for the worse after the death of Pocahontas in England and the return of John Rolfe and other colonial leaders in May 1617. Disease, poor harvests and the growing demand for tobacco lands caused hostilities to escalate.

After Wahunsenacawh's death in 1618, he was soon succeeded by his own younger brother, Opechancanough. He maintained friendly relations with the Colony on the surface, negotiating with them through his warrior

Nemattanew, but by 1622, after Nemattanew had been slain, Opechancanough was ready to order a limited surprise attack on the colonists, hoping to persuade them to move on and settle elsewhere.

Chief Opechancanough organized and led a well-coordinated series of surprise attacks on multiple English settlements along both sides of a long stretch of the James River, which took place early on the morning of March 22, 1622. This event came to be known as the

Indian Massacre of 1622 and resulted in the deaths of 347 colonists (including men, women, and children) and the abduction of many others. The Massacre caught most of the Virginia Colony by surprise and virtually wiped out several entire communities, including

Henricus

The "Citie of Henricus"—also known as Henricopolis, Henrico Town or Henrico—was a settlement in Virginia founded by Sir Thomas Dale in 1611 as an alternative to the swampy and dangerous area around the original English settlement at Jamest ...

and

Wolstenholme Town at

Martin's Hundred

Martin's Hundred was an early 17th-century plantation located along about ten miles (16 km) of the north shore of the James River in the Virginia Colony east of Jamestown in the southeastern portion of present-day James City County, Virgin ...

.

Jamestown was spared from destruction, however, due to a Virginia Indian boy named

Chanco who, after learning of the planned attacks from his brother, gave warning to colonist

Richard Pace with whom he lived. Pace, after securing himself and his neighbors on the south side of the James River, took a canoe across the river to warn Jamestown, which narrowly escaped destruction, although there was no time to warn the other settlements.

A year later, Captain

William Tucker and Dr.

John Potts worked out a truce with the Powhatan and proposed a toast using liquor laced with poison. 200 Virginia Indians were killed or made ill by the poison and 50 more were slaughtered by the colonists. For over a decade, the English settlers killed Powhatan men and women, captured children and systematically razed villages, seizing or destroying crops.

By 1634, a six-mile-long

palisade was completed across the

Virginia Peninsula. The new palisade provided some security from attacks by the Virginia Indians for colonists farming and fishing lower on the Peninsula from that point.

On April 18, 1644, Opechancanough again tried to force the colonists to abandon the region with another series of coordinated attacks, killing almost 500 colonists. However, this was a smaller proportion of the growing population than had been killed in the 1622 attacks.

Crown colony (1624–1652)

In 1620, a successor to the Plymouth Company sent colonists to the New World aboard the ''

Mayflower''. Known as

Pilgrims, they successfully established a settlement in what became

Massachusetts

Massachusetts (Massachusett: ''Muhsachuweesut Massachusett_writing_systems.html" ;"title="nowiki/> məhswatʃəwiːsət.html" ;"title="Massachusett writing systems">məhswatʃəwiːsət">Massachusett writing systems">məhswatʃəwiːsət'' En ...

. The portion of what had been Virginia north of the 40th parallel became known as

New England

New England is a region comprising six states in the Northeastern United States: Connecticut, Maine, Massachusetts, New Hampshire, Rhode Island, and Vermont. It is bordered by the state of New York (state), New York to the west and by the Can ...

, according to books written by

Captain John Smith

John Smith (baptized 6 January 1580 – 21 June 1631) was an English soldier, explorer, colonial governor, Admiral of New England, and author. He played an important role in the establishment of the colony at Jamestown, Virginia, the first pe ...

, who had made a voyage there.

In 1624, the charter of the Virginia Company was revoked by King James I and the Virginia Colony was transferred to royal authority in the form of a

crown colony. Subsequent charters for the

Maryland Colony

The Province of Maryland was an English and later British colony in North America that existed from 1632 until 1776, when it joined the other twelve of the Thirteen Colonies in rebellion against Great Britain and became the U.S. state of Maryland ...

in 1632 and to the eight

Lords Proprietors

A lord proprietor is a person granted a royal charter for the establishment and government of an English colony in the 17th century. The plural of the term is "lords proprietors" or "lords proprietary".

Origin

In the beginning of the European ...

of the

Province of Carolina in 1663 and 1665 further reduced the Virginia Colony to roughly the coastal borders it held until the

American Revolution

The American Revolution was an ideological and political revolution that occurred in British America between 1765 and 1791. The Americans in the Thirteen Colonies formed independent states that defeated the British in the American Revoluti ...

. (The exact border with North Carolina was disputed until surveyed by

William Byrd II

William Byrd II (March 28, 1674August 26, 1744) was an American planter, lawyer, surveyor, author, and a man of letters. Born in Colonial Virginia, he was educated in London, where he practiced law. Upon his father's death, he returned to Virg ...

in 1728.)

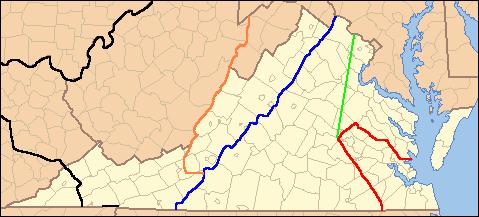

Third Anglo-Powhatan War (1644–1646)

After twelve years of peace following the Indian Wars of 1622–1632, another Anglo–Powhatan War began on March 18, 1644, as a last effort by the remnants of the Powhatan Confederacy, still under

Opechancanough

Opechancanough (; 1554–1646)Rountree, Helen C. Pocahontas, Powhatan, ''Opechancanough: Three Indian Lives Changed by Jamestown.'' University of Virginia Press: Charlottesville, 2005 was paramount chief of the Powhatan Confederacy in presen ...

, to dislodge the English settlers of the Virginia Colony. Around 500 colonists were killed, but that number represented a relatively low percent of the overall population, as opposed to the earlier massacre (the 1622 attack had wiped out a third; that of 1644 barely a tenth). However, Opechancanough, still preferring to use Powhatan tactics, did not make any major follow-up to this attack.

This was followed by another effort by the settlers to decimate the Powhatan. In July, they marched against the Pamunkey, Chickahominy, and Powhatan proper; and south of the James, against the Appomattoc, Weyanoke, Warraskoyak, and Nansemond, as well as two Carolina tribes, the

Chowanoke and

Secotan

The Secotans were one of several groups of American Indians dominant in the Carolina sound region, between 1584 and 1590, with which English colonists had varying degrees of contact. Secotan villages included the Secotan, Aquascogoc, Dasamonguep ...

.

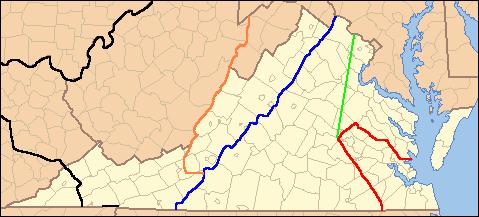

In February - March 1645, the colony ordered the construction of four frontier forts: Fort Charles at the falls of the James, Fort James on the Chickahominy, Fort Royal at the falls of the York and

Fort Henry at the falls of the Appomattox, where the modern city of Petersburg is located.

In August 1645, the forces of Governor

William Berkeley stormed Opechancanough's stronghold. All captured males in the village over age 11 were deported to

Tangier Island

Tangier is a town in Accomack County, Virginia, United States, on Tangier Island in Chesapeake Bay. The population was 727 at the 2010 census. Since 1850, the island's landmass has been reduced by 67%. Under the mid-range sea level rise scena ...

. Opechancanough, variously reported to be 92 to 100 years old, was taken to Jamestown. While a prisoner, Opechancanough was shot in the back and killed by a soldier assigned to guard him. His death resulted in the disintegration of the Powhatan Confederacy into its component tribes, whom the colonists continued to attack.

Treaty of 1646

In the peace treaty of October 1646, the new ''weroance'',

Necotowance Necotowance (c. Unknown birth year - died before 1655) was Werowance (chief) of the Pamunkey tribe and Paramount Chief of the Powhatan Confederacy after Opechancanough, from 1646 until his death sometime before 1655. Necotowance signed a treaty with ...

, and the subtribes formerly in the Confederacy, each became tributaries to the King of England. At the same time, a racial frontier was delineated between Indian and English settlements, with members of each group forbidden to cross to the other side except by a special pass obtained at one of the newly erected border forts. The extent of the Virginia colony open to patent by English colonists was defined as: All the land between the

Blackwater and

York

York is a cathedral city with Roman origins, sited at the confluence of the rivers Ouse and Foss in North Yorkshire, England. It is the historic county town of Yorkshire. The city has many historic buildings and other structures, such as a ...

rivers, and up to the navigable point of each of the major rivers – which were connected by a straight line running directly from modern Franklin on the Blackwater, northwesterly to the Appomattoc village beside Fort Henry, and continuing in the same direction to the

Monocan village above the falls of the James, where Fort Charles was built, then turning sharp right, to Fort Royal on the York (Pamunkey) river. Necotowance thus ceded the English vast tracts of still-uncolonized land, much of it between the James and Blackwater. English settlements on the peninsula north of the York and below the Poropotank were also allowed, as they had already been there since 1640.

English Civil War and Commonwealth (1642–1660)

While the newer,

Puritan

The Puritans were English Protestants in the 16th and 17th centuries who sought to purify the Church of England of Roman Catholic practices, maintaining that the Church of England had not been fully reformed and should become more Protestant. ...

colonies, most notably

Massachusetts

Massachusetts (Massachusett: ''Muhsachuweesut Massachusett_writing_systems.html" ;"title="nowiki/> məhswatʃəwiːsət.html" ;"title="Massachusett writing systems">məhswatʃəwiːsət">Massachusett writing systems">məhswatʃəwiːsət'' En ...

, were dominated by Parliamentarians, the older colonies sided with the Crown. The

Virginia Company's two settlements, Virginia and

Bermuda

)

, anthem = "God Save the King"

, song_type = National song

, song = "Hail to Bermuda"

, image_map =

, map_caption =

, image_map2 =

, mapsize2 =

, map_caption2 =

, subdivision_type = Sovereign state

, subdivision_name =

, es ...

(Bermuda's Independent Puritans were expelled as the

Eleutheran Adventurers, settling the

Bahamas

The Bahamas (), officially the Commonwealth of The Bahamas, is an island country within the Lucayan Archipelago of the West Indies in the North Atlantic. It takes up 97% of the Lucayan Archipelago's land area and is home to 88% of the ar ...

under

William Sayle),

Antigua and

Barbados

Barbados is an island country in the Lesser Antilles of the West Indies, in the Caribbean region of the Americas, and the most easterly of the Caribbean Islands. It occupies an area of and has a population of about 287,000 (2019 estimate) ...

were conspicuous in their loyalty to the Crown, and were singled out by the

Rump Parliament in

An Act for prohibiting Trade with the Barbadoes, Virginia, Bermuda and Antego in October 1650. This dictated that:

e punishment einflicted upon the said Delinquents, do sDeclare all and every the said persons in Barbada's, Antego, Bermuda's and Virginia, that have contrived, abetted, aided or assisted those horrid Rebellions, or have since willingly joyned with them, to be notorious Robbers and Traitors, and such as by the Law of Nations are not to be permitted any maner of Commerce or Traffique with any people whatsoever; and do sforbid to all maner of persons, Foreiners, and others, all maner of Commerce, Traffique and Correspondency whatsoever, to be used or held with the said Rebels in the Barbada's, Bermuda's, Virginia and Antego, or either of them.

The Act also authorised Parliamentary

privateer

A privateer is a private person or ship that engages in maritime warfare under a commission of war. Since robbery under arms was a common aspect of seaborne trade, until the early 19th century all merchant ships carried arms. A sovereign or deleg ...

s to act against English vessels trading with the rebellious colonies: "All Ships that Trade with the Rebels may be surprized. Goods and tackle of such ships not to be embezeled, till judgement in the Admiralty; Two or three of the Officers of every ship to be examined upon oath."

Virginia's population swelled with Cavaliers during and after the

English Civil War

The English Civil War (1642–1651) was a series of civil wars and political machinations between Parliamentarians (" Roundheads") and Royalists led by Charles I ("Cavaliers"), mainly over the manner of England's governance and issues of re ...

. Under the tenure of

Crown Governor William Berkeley (1642–1652; 1660–1677), the population expanded from 8,000 in 1642 to 40,000 in 1677.

Despite the resistance of the

Virginia Cavaliers, Virginian Puritan

Richard Bennett was made Governor answering to Cromwell in 1652, followed by two more nominal "Commonwealth Governors". Nonetheless, the colony was rewarded for its loyalty to the Crown by Charles the II following the Restoration when

Crown colony restoration (1660–1775)

With the

Restoration in 1660 the Governorship returned to its previous holder,

Sir William Berkeley.

In 1676,

Bacon's Rebellion

Bacon's Rebellion was an armed rebellion held by Virginia settlers that took place from 1676 to 1677. It was led by Nathaniel Bacon against Colonial Governor William Berkeley, after Berkeley refused Bacon's request to drive Native American ...

challenged the political order of the colony. While a military failure, its handling did result in Governor Berkeley being recalled to England.

In 1679, the

Treaty of Middle Plantation

The Treaty of 1677 (also known as the Treaty Between Virginia And The Indians 1677 or Treaty of Middle Plantation) was signed in Virginia on May 28, 1677, between the English Crown and representatives from various Virginia Native American tribes ...

was signed between King Charles II and several Native American groups.

Williamsburg era

Virginia was the largest, richest, and most influential of the American colonies, where conservatives were in full control of the colonial and local governments. At the local level, Church of England parishes handled many local affairs, and they in turn were controlled not by the minister, but rather by a closed circle of rich landowners who comprised the parish vestry. Ronald L. Heinemann emphasizes the ideological conservatism of Virginia while noting there were also religious dissenters who were gaining strength by the 1760s:

In actual practice, colonial Virginia never had a bishop to represent God nor a hereditary aristocracy with titles like 'duke' or 'baron'. However, it did have a royal governor appointed by the king, as well as a powerful landed gentry. The status quo was strongly reinforced by what Jefferson called "feudal and unnatural distinctions" that were vital to the maintenance of aristocracy in Virginia. He promoted laws such as

entail

In English common law, fee tail or entail is a form of trust established by deed or settlement which restricts the sale or inheritance of an estate in real property and prevents the property from being sold, devised by will, or otherwise alien ...

and

primogeniture by which the oldest son inherited all the land. As a result increasingly large plantations, worked by white tenant farmers and by black slaves, gained in size and wealth and political power in the eastern ("Tidewater") tobacco areas. Maryland and South Carolina had similar hierarchical systems, as did New York and Pennsylvania. During the Revolutionary era, all such laws were repealed by the new states. The most fervent Loyalists left for Canada or Britain or other parts of the Empire. They introduced primogeniture in Upper Canada (Ontario) in 1792, and it lasted until 1851. Such laws lasted in England until 1926.

American Revolution

Relations with the Natives

As the English expanded out from Jamestown, encroachment of the new arrivals and their ever-growing numbers on what had been Indian lands resulted in several conflicts with the

Virginia Indian

The Native American tribes in Virginia are the indigenous tribes who currently live or have historically lived in what is now the Commonwealth of Virginia in the United States of America.

All of the Commonwealth of Virginia used to be Virgini ...

s. For much of the 17th century, English contact and conflict were mostly with the

Algonquian peoples that populated the coastal regions, primarily the Powhatan Confederacy. Following a series of wars and the decline of the Powhatan as a political entity, the colonists expanded westward in the late 17th and 18th centuries, encountering the

Shawnee

The Shawnee are an Algonquian-speaking indigenous people of the Northeastern Woodlands. In the 17th century they lived in Pennsylvania, and in the 18th century they were in Pennsylvania, Ohio, Indiana and Illinois, with some bands in Kentucky a ...

,

Iroquoian

The Iroquoian languages are a language family of indigenous peoples of North America. They are known for their general lack of labial consonants. The Iroquoian languages are polysynthetic and head-marking.

As of 2020, all surviving Iroquoian ...

-speaking peoples such as the

Nottoway,

Meherrin

The Meherrin Nation ( autonym: Kauwets'a:ka, "People of the Water") is one of seven state-recognized nations of Native Americans in North Carolina. They reside in rural northeastern North Carolina, near the river of the same name on the Virgini ...

,

Iroquois

The Iroquois ( or ), officially the Haudenosaunee ( meaning "people of the longhouse"), are an Iroquoian-speaking confederacy of First Nations peoples in northeast North America/ Turtle Island. They were known during the colonial years to ...

and

Cherokee

The Cherokee (; chr, ᎠᏂᏴᏫᏯᎢ, translit=Aniyvwiyaʔi or Anigiduwagi, or chr, ᏣᎳᎩ, links=no, translit=Tsalagi) are one of the indigenous peoples of the Southeastern Woodlands of the United States. Prior to the 18th century, t ...

, as well as

Siouan-speaking peoples such as the

Tutelo

The Tutelo (also Totero, Totteroy, Tutera; Yesan in Tutelo) were Native American people living above the Fall Line in present-day Virginia and West Virginia. They spoke a Siouan dialect of the Tutelo language thought to be similar to that of thei ...

,

Saponi

The Saponi or Sappony are a Native American tribe historically based in the Piedmont of North Carolina and Virginia.Raymond D. DeMaillie, "Tutelo and Neighboring Groups," pages 286–87. They spoke a Siouan language, related to the languages of ...

, and

Occaneechi

The Occaneechi (also Occoneechee and Akenatzy) are Native Americans who lived in the 17th century primarily on the large, long Occoneechee Island and east of the confluence of the Dan and Roanoke rivers, near current-day Clarksville, Virginia. ...

.

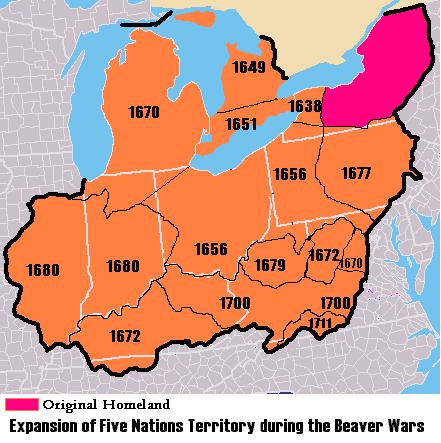

Iroquois Confederacy

As the English settlements expanded beyond the Tidewater territory traditionally occupied by the Powhatan, they encountered new groups with which there had been minimal relations with the Colony.

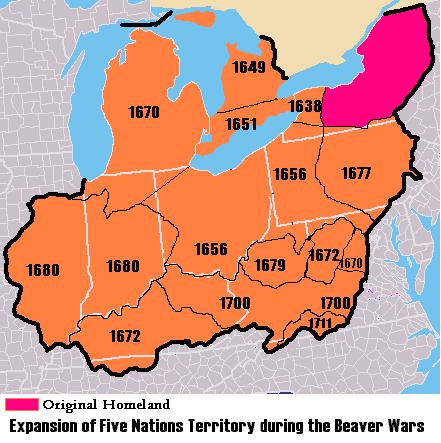

In the late 17th century, the

Iroquois Confederacy expanded into the Western region of Virginia as part of the

Beaver Wars. They arrived shortly before the English settlers, and displaced the resident

Siouan tribes.

Lt. Gov.

Alexander Spotswood

Alexander Spotswood (12 December 1676 – 7 June 1740) was a British Army officer, explorer and lieutenant governor of Colonial Virginia; he is regarded as one of the most significant historical figures in British North American colonial h ...

made further advances in policy with the Virginia Indians along the frontier. In 1714, he established

Fort Christanna

Fort Christanna was one of the projects of Lt. Governor Alexander Spotswood, who was governor of the Virginia Colony 1710–1722. When Fort Christanna opened in 1714, Capt.

Robert Hicks was named captain of the fort and he relocated his family ...

to help educate and trade with several tribes with which the colony had friendly relations, as well as to help protect them from hostile tribes. In 1722 the

Treaty of Albany was signed by leaders of the Five Nations of

Iroquois

The Iroquois ( or ), officially the Haudenosaunee ( meaning "people of the longhouse"), are an Iroquoian-speaking confederacy of First Nations peoples in northeast North America/ Turtle Island. They were known during the colonial years to ...

,

Province of New York

The Province of New York (1664–1776) was a British proprietary colony and later royal colony on the northeast coast of North America. As one of the Middle Colonies, New York achieved independence and worked with the others to found the U ...

, Colony of Virginia, and

Province of Pennsylvania.

Lord Dunmore's War

Geography

The cultural geography of colonial Virginia gradually evolved, with a variety of settlement and jurisdiction models experimented with. By the late 17th century and into the 18th century, the primary settlement pattern was based on plantations (to grow tobacco), farms, and some towns (mostly ports or courthouse villages).

Early settlements

The fort at Jamestown, founded in 1607, remained the primary settlement of the colonists for several years. A few strategic outposts were constructed, including

Fort Algernon Fort Algernon (also spelled Fort Algernourne) was established in the fall of 1609 at the mouth of Hampton Roads at Point Comfort in the Virginia Colony. A strategic point for guarding the shipping channel leading from the Chesapeake Bay, Fort Monro ...

(1609) at the entrance to the James River.

Early attempts to occupy strategic locations already inhabited by natives at what is now

Richmond and

Suffolk failed owing to native resistance.

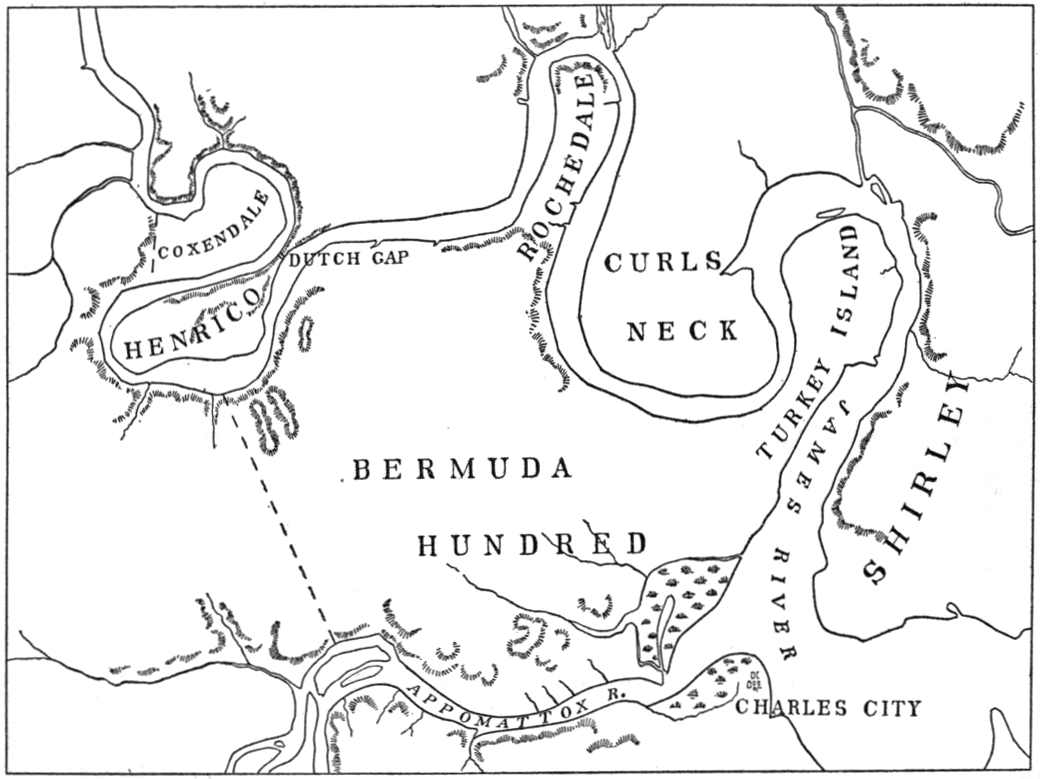

A short distance farther up the James, in 1611,

Thomas Dale

Sir Thomas Dale ( 1570 − 19 August 1619) was an English naval commander and deputy-governor of the Virginia Colony in 1611 and from 1614 to 1616. Governor Dale is best remembered for the energy and the extreme rigour of his administration in ...

began the construction of a progressive development at

Henricus

The "Citie of Henricus"—also known as Henricopolis, Henrico Town or Henrico—was a settlement in Virginia founded by Sir Thomas Dale in 1611 as an alternative to the swampy and dangerous area around the original English settlement at Jamest ...

on and about what was later known as

Farrars Island. Henricus was envisioned as possible replacement capital for Jamestown, and was to have the first college in Virginia. (The ill-fated Henricus was destroyed during the

Indian Massacre of 1622). In addition to creating the new settlement at Henricus, Dale also established the port town of

Bermuda Hundred, as well as

"Bermuda Cittie" (sic) in 1613, now part of

Hopewell, Virginia

Hopewell is an independent city surrounded by Prince George County and the Appomattox River in the Commonwealth of Virginia. At the 2020 census, the population was 23,033. The Bureau of Economic Analysis combines the city of Hopewell with Prin ...

. He began the excavation work at

Dutch Gap, using methods he had learned while serving in

Holland

Holland is a geographical regionG. Geerts & H. Heestermans, 1981, ''Groot Woordenboek der Nederlandse Taal. Deel I'', Van Dale Lexicografie, Utrecht, p 1105 and former province on the western coast of the Netherlands. From the 10th to the 16th c ...

.

"Hundreds"

Once tobacco had been established as an export cash crop, investors became more interested and groups of them united to create largely self-sufficient "hundreds." The term

"hundred" is a traditional English name for an administrative division of a shire (or county) to define an area which would support one hundred heads of household. In the colonial era in Virginia, the "hundreds" were large developments of many acres, necessary to support land hungry tobacco crops. The "hundreds" were required to be at least several miles from any existing community. Soon, these patented tracts of land sprang up along the rivers. The investors sent shiploads of settlers and supplies to Virginia to establish the new developments. The administrative centers of Virginia's hundreds were essentially small towns or villages, and were often palisaded for defense.

An example was

Martin's Hundred

Martin's Hundred was an early 17th-century plantation located along about ten miles (16 km) of the north shore of the James River in the Virginia Colony east of Jamestown in the southeastern portion of present-day James City County, Virgin ...

, located downstream from Jamestown on the north bank of the James River. It was sponsored by the

Martin's Hundred Society Martin's may refer to:

Places

* Martin's Additions, Maryland, USA

* Martin's Battery, Gibraltar

* Martin's Beach, California, USA

* Martin's Brandon Church, Virginia, USA

* Martin's Brook, Nova Scotia, Canada

* Martin's Cave, Gibraltar

* Marti ...

, a group of investors in London. It was settled in 1618, and

Wolstenholme Towne was its administrative center, named for Sir John Wolstenholme, one of the investors.

Bermuda Hundred (now in

Chesterfield County) and

Flowerdew Hundred

Flowerdew Hundred Plantation dates to 1618/19 with the patent by Sir George Yeardley, the Governor and Captain General of Virginia, of on the south side of the James River. Yeardley probably named the plantation after his wife's wealthy father, ...

(now in

Prince George County) are other names which have survived over centuries. Others included

Berkeley Hundred

Berkeley Hundred was a Virginia Colony, founded in 1619, which comprised about eight thousand acres (32 km²) on the north bank of the James River. It was near Herring Creek in an area which is now known as Charles City County, Virginia. It w ...

, Bermuda Nether Hundred, Bermuda Upper Hundred,

Smith's Hundred, Digges Hundred, West Hundred and Shirley Hundred (and, in Bermuda, ''Harrington Hundreds'').

Including the creation of the "hundreds", the various incentives to investors in the Virginia Colony finally paid off by 1617. By this time, the colonists were exporting 50,000 pounds of tobacco to England a year and were beginning to generate enough profit to ensure the economic survival of the colony.

Cities, Shires, and Counties

In 1619, the plantations and developments were divided into four "incorporations" or "citties" (sic), as they were called. These were

Charles Cittie,

Elizabeth Cittie,

Henrico Cittie, and

James Cittie, which included the relatively small seat of government for the colony at

Jamestown Island

Jamestown Island is a island in the James River in Virginia, part of James City County. It is located off Glasshouse Point, to which it is connected via a causeway to the Colonial Parkway. Much of the island is wetland, including both swamp and ...

. Each of the four "citties" (sic) extended across the

James River, the main conduit of transportation of the era. Elizabeth Cittie, known initially as

Kecoughtan (a Native word with many variations in spelling by the English), also included the areas now known as

South Hampton Roads

South Hampton Roads is a region located in the extreme southeastern portion of Virginia's Tidewater region in the United States with a total population of 1,191,937. It is part of the Virginia Beach-Norfolk-Newport News, VA-NC MSA (Metropolitan S ...

and the

Eastern Shore.

In 1634, a new system of local government was created in the Virginia Colony by order of the King of England. Eight

shires were designated, each with its own local officers. Within a few years, the shires were renamed

counties

A county is a geographic region of a country used for administrative or other purposesChambers Dictionary, L. Brookes (ed.), 2005, Chambers Harrap Publishers Ltd, Edinburgh in certain modern nations. The term is derived from the Old French ...

, a system that has remained to the present day.

Later settlements

In 1630, under the governorship of

John Harvey, the first settlement on the

York River was founded. In 1632, the Virginia legislature voted to build a fort to link Jamestown and the York River settlement of

Chiskiack and protect the colony from Indian attacks. In 1634, a palisade was built near Middle Plantation. This wall stretched across the peninsula between the York and James rivers and protected the settlements on the eastern side of the lower Peninsula from Indians. The wall also served to contain cattle.

In 1699, a new capital was established and built at

Middle Plantation, soon renamed

Williamsburg.

Northern Neck Proprietary

In the period following the

English Civil War

The English Civil War (1642–1651) was a series of civil wars and political machinations between Parliamentarians (" Roundheads") and Royalists led by Charles I ("Cavaliers"), mainly over the manner of England's governance and issues of re ...

, the exiled King

Charles II of England hoped to shore up the loyalty of several of his supporters by granting them a significant area of mostly uncharted land to control as a

Proprietary in Virginia (a claim that would only be valid were the king to return to power). While under the jurisdiction of the Virginia Colony, the proprietary maintained complete control of the granting of land within that territory (and revenues obtained from it) until after the American Revolution. The grant was for the land between the Rappahannock and Potomac Rivers, which included the titular

Northern Neck

The Northern Neck is the northernmost of three peninsulas (traditionally called "necks" in Virginia) on the western shore of the Chesapeake Bay in the Commonwealth of Virginia (along with the Middle Peninsula and the Virginia Peninsula). The P ...

, but as time went on also would include all of what is today

Northern Virginia

Northern Virginia, locally referred to as NOVA or NoVA, comprises several counties and independent cities in the Commonwealth of Virginia in the United States. It is a widespread region radiating westward and southward from Washington, D.C. Wit ...

and into West Virginia. Due to ambiguities of the text of the various grants causing disputes between the proprietary and the colonial government, the tract was finally demarcated via the

Fairfax Line in 1746.

Government and law

In the initial years under the Virginia Company, the colony was governed by a council, headed by a council President. From 1611 to 1618, under the orders of Sir

Thomas Dale

Sir Thomas Dale ( 1570 − 19 August 1619) was an English naval commander and deputy-governor of the Virginia Colony in 1611 and from 1614 to 1616. Governor Dale is best remembered for the energy and the extreme rigour of his administration in ...

, the settlers of the colony were under a regime of civil law that became known as

Dale's Code.

Under a charter from the company in 1618, a new model of governance was put in place in 1619, which created a new

House of Burgesses.

On July 30, 1619, burgesses met at

Jamestown Church

Jamestown Church, constructed in brick from 1639 onward, in Jamestown in the Mid-Atlantic state of Virginia, is one of the oldest surviving building remnants built by Europeans in the original thirteen colonies and in the United States overa ...

as the first elected representative legislative assembly in the New World.

The legal system in the colony was thereafter based around the English

common law

In law, common law (also known as judicial precedent, judge-made law, or case law) is the body of law created by judges and similar quasi-judicial tribunals by virtue of being stated in written opinions."The common law is not a brooding omnipres ...

.

For much of the history of the Royal Colony, the formal appointed governor was absentee, often remaining in England. In his stead, a series of acting or Lieutenant Governors who were physically present held actual authority. In the later years of its history, as it became increasingly civilized, more governors made the journey.

The first settlement in the colony, Jamestown, served as the capital and main port of entry from its founding until 1699. During this time, a series of statehouses (capitols) were used and subsequently consumed by fires (both accidental, and in the case of Bacon's Rebellion, intentional). Following such a fire, in 1699 the capital was relocated inland, away from the swampy clime of Jamestown to Middle Plantation, soon to be renamed Williamsburg.

The capital of Virginia remained in Williamsburg, until it was moved further inland to

Richmond in 1779 during the American Revolution.

Economy

The entrepreneurs of the Virginia Company experimented with a number of means of making the colony profitable. The orders sent with the first colonists instructed that they search for precious metals (specifically

gold

Gold is a chemical element with the symbol Au (from la, aurum) and atomic number 79. This makes it one of the higher atomic number elements that occur naturally. It is a bright, slightly orange-yellow, dense, soft, malleable, and ductile me ...

). While no gold was found, various products were sent back, including pitch and

clapboard

Clapboard (), also called bevel siding, lap siding, and weatherboard, with regional variation in the definition of these terms, is wooden siding of a building in the form of horizontal boards, often overlapping.

''Clapboard'' in modern Americ ...

. In 1608, early attempts were made at breaking the

Continental

Continental may refer to:

Places

* Continent, the major landmasses of Earth

* Continental, Arizona, a small community in Pima County, Arizona, US

* Continental, Ohio, a small town in Putnam County, US

Arts and entertainment

* ''Continental'' ( ...

hold on glassmaking through the

creation of a glassworks. In 1619, the colonist built the

first ironworks in North America.

In 1612, settler John Rolfe planted

tobacco

Tobacco is the common name of several plants in the genus '' Nicotiana'' of the family Solanaceae, and the general term for any product prepared from the cured leaves of these plants. More than 70 species of tobacco are known, but the ...

obtained from Bermuda (during his stay there as part of the

Third Supply The Jamestown supply missions were a series of fleets (or sometimes individual ships) from 1607 to around 1611 that were dispatched from England by the London Company (also known as the Virginia Company of London) with the specific goal of initially ...

). Within a few years, the crop proved extremely lucrative in the European market. As the English increasingly used tobacco products, the production of

tobacco in the American Colonies

Tobacco cultivation and exports formed an essential component of the American colonial economy. During the Civil War, they were distinct from other cash crops in terms of agricultural demands, trade, slave labor, and plantation culture. Many influe ...

became a significant economic driver, especially in the tidewater region surrounding the Chesapeake Bay.

Colonists developed plantations along the rivers of Virginia, and social/economic systems developed to grow and distribute this

cash crop. Some elements of this system included the importation and use of enslaved Africans to cultivate and process crops, which included harvesting and drying periods. Planters would have their workers fill large

hogsheads with tobacco and convey them to inspection warehouses. In 1730, the

Virginia

Virginia, officially the Commonwealth of Virginia, is a state in the Mid-Atlantic and Southeastern regions of the United States, between the Atlantic Coast and the Appalachian Mountains. The geography and climate of the Commonwealth ar ...

House of Burgesses standardized and improved the quality of tobacco exported by establishing the

Tobacco Inspection Act of 1730, which required inspectors to grade tobacco at 40 specified locations.

Culture

Ethnic origins

England supplied the great majority of colonists. In 1608, the first

Poles

Poles,, ; singular masculine: ''Polak'', singular feminine: ''Polka'' or Polish people, are a West Slavic nation and ethnic group, who share a common history, culture, the Polish language and are identified with the country of Poland in C ...

and

Slovaks arrived as part of a group of skilled

craftsmen.

In 1619, the

first Africans arrived. Many more Africans were imported as slaves, such as

Angela. In the early 17th century, French

Huguenots

The Huguenots ( , also , ) were a religious group of French Protestants who held to the Reformed, or Calvinist, tradition of Protestantism. The term, which may be derived from the name of a Swiss political leader, the Genevan burgomaster Be ...

arrived in the colony as refugees from religious warfare.

In the early 18th century, indentured German-speaking colonists from the iron-working region of Nassau-Siegen arrived to establish the

Germanna

Germanna was a German settlement in the Colony of Virginia, settled in two waves, first in 1714 and then in 1717. Virginia Lieutenant Governor Alexander Spotswood encouraged the immigration by advertising in Germany for miners to move to Virgini ...

settlement. Scots-Irish settled on the Virginia frontier. Some Welsh arrived, including some ancestors of Thomas Jefferson.

Servitude and slavery

With the boom in tobacco planting, there was a severe shortage of laborers to work the labor-intensive crop. One method to solve the shortage was through the usage of

indentured servant

Indentured servitude is a form of labor in which a person is contracted to work without salary for a specific number of years. The contract, called an "indenture", may be entered "voluntarily" for purported eventual compensation or debt repaymen ...

s.

By the 1640s, legal documents started to define the changing nature of indentured servants and their status as servants. In 1640,

John Punch was sentenced to lifetime servitude as punishment for trying to escape from his master Hugh Gwyn. This is the earliest legal sanctioning of slavery in Virginia. After this trial, the relationship between indentured servants and their masters changed, as planters saw permanent servitude a more appealing and profitable prospect than seven-year indentures.

As many indentured workers were illiterate, especially Africans, there were opportunities for abuse by planters and other indenture holders. Some ignored the expiration of servants' indentured contracts and tried to keep them as lifelong workers. One example is with

Anthony Johnson, who argued with Robert Parker, another planter, over the status of

John Casor

John Casor (surname also recorded as Cazara and Corsala), a servant in Northampton County, Virginia, Northampton County in the Virginia Colony, in 1655 became the first person of African descent in the Thirteen Colonies to be declared as a Slaver ...

, formerly an indentured servant of his. Johnson argued that his indenture was for life and Parker had interfered with his rights. The court ruled in favor of Johnson and ordered that Casor be returned to him, where he served the rest of his life as a slave. Such documented cases marked the transformation of Black Africans from indentured servants into slaves.

In the late 17th century, the

Royal African Company, which was established by the King of England to supply the great demand for labor to the colonies, had a monopoly on the provision of African slaves to the colony.

As plantation agriculture was established earlier in Barbados, in the early years, enslaved people were shipped from Barbados (where they were seasoned) to the colonies of Virginia and Carolina.

Religion

In 1619, the

Anglican Church

Anglicanism is a Western Christian tradition that has developed from the practices, liturgy, and identity of the Church of England following the English Reformation, in the context of the Protestant Reformation in Europe. It is one of the ...

was formally