Cologne War on:

[Wikipedia]

[Google]

[Amazon]

The Cologne War (german: Kölner Krieg, Kölnischer Krieg, Truchsessischer Krieg; 1583–88) was a conflict between

Cologne

. Unfortunately for him, he had converted to another branch of the Reformed faith; such cautious Lutheran princes as Augustus I, Elector of Saxony, balked at extending their military support to Calvinists and the Elector Palatine was unable to persuade them to join the cause. Gebhard had three primary supporters. His brother, Karl, had married Eleonore, Countess of

In late February 1586, Friedrich Cloedt, whom Gebhard had placed in command of Neuss, and Martin Schenck went to Westphalia at the head of 500 foot and 500 horse. After plundering

In late February 1586, Friedrich Cloedt, whom Gebhard had placed in command of Neuss, and Martin Schenck went to Westphalia at the head of 500 foot and 500 horse. After plundering

To some extent, the difficulties both Gebhard and Ernst faced in winning the war were the same the Spanish had in subduing the Dutch Revolt. The protraction of the Spanish and Dutch war—80 years of bitter fighting interrupted by periodic truces while both sides gathered resources—lay in the kind of war it was: enemies lived in fortified towns defended by Italian-style bastions, which meant the towns had to be taken and then fortified and maintained. For both Gebhard and Ernst, as for the Spanish commanders in the nearby Lowlands, winning the war meant not only mobilizing enough men to encircle a seemingly endless cycle of enemy artillery fortresses, but also maintaining the army one had and defending all one's own possessions as they were acquired. The Cologne War, similar to the Dutch Revolt in that respect, was also a war of sieges, not of assembled armies facing one another on the field of battle, nor of maneuver, feint, and parry that characterized wars two centuries earlier and later. These wars required men who could operate the machinery of war, which meant extensive economic resources for soldiers to build and operate the siege works, and a political and military will to keep the machinery of war operating. The Spanish faced another problem, distance, which gave them a distinct interest in intervening in the Cologne affair: the Electorate lay on the Rhine River, and the Spanish road.

To some extent, the difficulties both Gebhard and Ernst faced in winning the war were the same the Spanish had in subduing the Dutch Revolt. The protraction of the Spanish and Dutch war—80 years of bitter fighting interrupted by periodic truces while both sides gathered resources—lay in the kind of war it was: enemies lived in fortified towns defended by Italian-style bastions, which meant the towns had to be taken and then fortified and maintained. For both Gebhard and Ernst, as for the Spanish commanders in the nearby Lowlands, winning the war meant not only mobilizing enough men to encircle a seemingly endless cycle of enemy artillery fortresses, but also maintaining the army one had and defending all one's own possessions as they were acquired. The Cologne War, similar to the Dutch Revolt in that respect, was also a war of sieges, not of assembled armies facing one another on the field of battle, nor of maneuver, feint, and parry that characterized wars two centuries earlier and later. These wars required men who could operate the machinery of war, which meant extensive economic resources for soldiers to build and operate the siege works, and a political and military will to keep the machinery of war operating. The Spanish faced another problem, distance, which gave them a distinct interest in intervening in the Cologne affair: the Electorate lay on the Rhine River, and the Spanish road.

The following day, Parma's artillery pounded at the walls for 3 hours with iron cannonballs weighing 30–50 pounds; in total, his artillery fired more than 2700 rounds. The Spanish made several attempts to storm the city, each repelled by Cloedt's 1600 soldiers. The ninth assault breached the outer wall. The Spanish and Italian forces entered the town from opposite ends and met in the middle. Cloedt, gravely injured (his leg was reportedly almost ripped off and he had five other serious wounds), had been carried into the town. Parma's troops discovered Cloedt, being nursed by his wife and his sister. Although Parma was inclined to honor the garrison commander with a soldier's death by sword, Ernst demanded his immediate execution. The dying man was hanged from the window, with several other officers in his force.

Parma made no effort to restrain his soldiers. On their rampage through the city, Italian and Spanish soldiers slaughtered the rest of the garrison, even the men who tried to surrender. Once their blood-lust was satiated, they began to plunder. Civilians who had taken refuge in the churches were initially ignored, but when the fire started, they were forced into the streets and trapped by the rampaging soldiers. Contemporary accounts refer to children, women, and old men, their clothes smoldering, or in flames, trying to escape the conflagration, only to be trapped by the enraged Spanish; if they escaped the flames and the Spanish, they were cornered by the enraged Italians. Parma wrote to King Philip that over 4000 lay dead in the ditches (moats). English observers confirmed this report, and elaborated that only eight buildings remained standing.

The following day, Parma's artillery pounded at the walls for 3 hours with iron cannonballs weighing 30–50 pounds; in total, his artillery fired more than 2700 rounds. The Spanish made several attempts to storm the city, each repelled by Cloedt's 1600 soldiers. The ninth assault breached the outer wall. The Spanish and Italian forces entered the town from opposite ends and met in the middle. Cloedt, gravely injured (his leg was reportedly almost ripped off and he had five other serious wounds), had been carried into the town. Parma's troops discovered Cloedt, being nursed by his wife and his sister. Although Parma was inclined to honor the garrison commander with a soldier's death by sword, Ernst demanded his immediate execution. The dying man was hanged from the window, with several other officers in his force.

Parma made no effort to restrain his soldiers. On their rampage through the city, Italian and Spanish soldiers slaughtered the rest of the garrison, even the men who tried to surrender. Once their blood-lust was satiated, they began to plunder. Civilians who had taken refuge in the churches were initially ignored, but when the fire started, they were forced into the streets and trapped by the rampaging soldiers. Contemporary accounts refer to children, women, and old men, their clothes smoldering, or in flames, trying to escape the conflagration, only to be trapped by the enraged Spanish; if they escaped the flames and the Spanish, they were cornered by the enraged Italians. Parma wrote to King Philip that over 4000 lay dead in the ditches (moats). English observers confirmed this report, and elaborated that only eight buildings remained standing.

Waldburg und Waldburger – Ein Geschlecht steigt auf in den Hochadel des Alten Reiches

Switzerland: TLC Michaela Waldburger, 2009, Accessed 15 October 2009. * Weyden, Ernst. ''Godesberg, das Siebengebirge, und ihre Umgebung''. Bonn: T. Habicht Verlag, 1864. * Wernham, Richard Bruce. ''The New Cambridge Modern History: The Counter Reformation and Price Revolution 1559–1610''. Vol. 3. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 1971, pp. 338–345.

"Grafen von Mansfeld"

in ''Allgemeine Deutsche Biographie''. Herausgegeben von der Historischen Kommission bei der Bayerischen Akademie der Wissenschaften, Band 20 (1884), ab Seite 212, Digitale Volltext-Ausgabe i

Wikisource

(Version vom 17. November 2009, 17:46 Uhr UTC). * Holweck, Frederick

in ''The Catholic Encyclopedia''. vol. 3, New York: Robert Appleton Company, 1908. * Lins, Joseph

an

New York: Robert Appleton Company, 1908. * Lomas, Sophie Crawford (ed.)

Calendar of State Papers Foreign, Elizabeth, Volume 18

Institute of Historical Research

British History Online

original publication, 1914. Accessed 1 November 2009. * _____

Calendar of State Papers Foreign, Elizabeth, Volume 21, Part 1, 1927British History Online

Accessed 17 November 2009. * Lossen, Max

"Gebhard"

''Allgemeine Deutsche Biographie''. Herausgegeben von der Historischen Kommission bei der Bayerischen Akademie der Wissenschaften, Band 8 (1878), ab Seite 457, Digitale Volltext-Ausgabe i

Wikisource

(Version vom 6. November 2009, 02:02 Uhr UTC). * _____

"Salentin"

''Allgemeine Deutsche Biographie''. Herausgegeben von der Historischen Kommission bei der Bayerischen Akademie der Wissenschaften, Band 30 (1890), Seite 216–224, Digitale Volltext-Ausgabe i

Wikisource

(Version vom 14. November 2009, 19:56 Uhr UTC). * Müller, P.L

"Adolf Graf von Neuenahr"

In ''Allgemeine Deutsche Biographie''. Herausgegeben von der Historischen Kommission bei der Bayerischen Akademie der Wissenschaften, Band 23 (1886), ab Seite 484, Digitale Volltext-Ausgabe i

Wikisource

(Version vom 17. November 2009, 18:23 Uhr UTC). * _____

Martin Schenk von Nideggen

in ''Allgemeine Deutsche Biographie''. Herausgegeben von der Historischen Kommission bei der Bayerischen Akademie der Wissenschaften, Band 31 (1890), ab Seite 62, Digitale Volltext-Ausgabe i

Wikisource

(Version vom 17. November 2009, 17:31 Uhr UTC). * Wember, Heinz

House of Waldburg: Jacobin Line

Augsburg, Germany: Heinrich Paul Wember, 2007, Accessed 2 October 2009. {{Featured article 1580s conflicts 1583 in Europe Counter-Reformation Electorate of Cologne House of Mansfeld House of Waldburg House of Wittelsbach Wars involving the Holy Roman Empire Wars involving Bavaria Wars involving Cologne 1580s in the Holy Roman Empire 1583 in the Holy Roman Empire 1584 in the Holy Roman Empire 1585 in the Holy Roman Empire 1586 in the Holy Roman Empire 1587 in the Holy Roman Empire 1588 in the Holy Roman Empire European wars of religion

Protestant

Protestantism is a Christian denomination, branch of Christianity that follows the theological tenets of the Reformation, Protestant Reformation, a movement that began seeking to reform the Catholic Church from within in the 16th century agai ...

and Catholic

The Catholic Church, also known as the Roman Catholic Church, is the largest Christian church, with 1.3 billion baptized Catholics worldwide . It is among the world's oldest and largest international institutions, and has played a ...

factions that devastated the Electorate of Cologne, a historical ecclesiastical principality of the Holy Roman Empire

The Holy Roman Empire was a political entity in Western, Central, and Southern Europe that developed during the Early Middle Ages and continued until its dissolution in 1806 during the Napoleonic Wars.

From the accession of Otto I in 962 unt ...

, within present-day North Rhine-Westphalia

North Rhine-Westphalia (german: Nordrhein-Westfalen, ; li, Noordrien-Wesfale ; nds, Noordrhien-Westfalen; ksh, Noodrhing-Wäßßfaale), commonly shortened to NRW (), is a state (''Land'') in Western Germany. With more than 18 million inha ...

, in Germany. The war occurred within the context of the Protestant Reformation in Germany and the subsequent Counter-Reformation

The Counter-Reformation (), also called the Catholic Reformation () or the Catholic Revival, was the period of Catholic resurgence that was initiated in response to the Protestant Reformation. It began with the Council of Trent (1545–1563) a ...

, and concurrently with the Dutch Revolt and the French Wars of Religion

The French Wars of Religion is the term which is used in reference to a period of civil war between French Catholics and Protestants, commonly called Huguenots, which lasted from 1562 to 1598. According to estimates, between two and four mil ...

.

Also called the Seneschal's War () or the Seneschal Upheaval () and occasionally the Sewer War, the conflict tested the principle of ecclesiastical reservation

The ' ( Latin, "ecclesiastical reservation"; ) was a provision of the Peace of Augsburg of 1555. It exempted ecclesiastical lands from the principle of ' ( Latin: whose land, his religion), which the Peace established for all hereditary dyn ...

, which had been included in the religious Peace of Augsburg (1555). This principle excluded, or "reserved", the ecclesiastical territories of the Holy Roman Empire from the application of ''cuius regio, eius religio

() is a Latin phrase which literally means "whose realm, their religion" – meaning that the religion of the ruler was to dictate the religion of those ruled. This legal principle marked a major development in the collective (if not individual ...

'', or "whose rule, his religion", as the primary means of determining the religion of a territory. It stipulated instead that if an ecclesiastical prince converted to Protestantism, he would resign from his position rather than force the conversion of his subjects.

In December 1582, Gebhard Truchsess von Waldburg, the Prince-elector

The prince-electors (german: Kurfürst pl. , cz, Kurfiřt, la, Princeps Elector), or electors for short, were the members of the electoral college that elected the emperor of the Holy Roman Empire.

From the 13th century onwards, the princ ...

of Cologne, converted to Protestantism

Protestantism is a Christian denomination, branch of Christianity that follows the theological tenets of the Reformation, Protestant Reformation, a movement that began seeking to reform the Catholic Church from within in the 16th century agai ...

. The principle of ecclesiastical reservation required his resignation. Instead, he declared religious parity for his subjects and, in 1583, married Agnes von Mansfeld-Eisleben, intending to convert the ecclesiastical principality into a secular, dynastic duchy. A faction in the Cathedral Chapter elected another archbishop, Ernst of Bavaria.

Initially, troops of the competing archbishops of Cologne

The Archbishop of Cologne is an archbishop governing the Archdiocese of Cologne of the Catholic Church in western North Rhine-Westphalia and is also a historical state in the Rhine holding the birthplace of Beethoven and northern Rhineland-Palat ...

fought over control of sections of the territory. Several of the barons and counts holding territory with feudal obligations to the Elector also held territory in nearby Dutch provinces; Westphalia, Liege, and the Southern, or Spanish Netherlands

Spanish Netherlands ( Spanish: Países Bajos Españoles; Dutch: Spaanse Nederlanden; French: Pays-Bas espagnols; German: Spanische Niederlande.) (historically in Spanish: ''Flandes'', the name "Flanders" was used as a '' pars pro toto'') was the ...

. Complexities of enfeoffment and dynastic '' appanage'' magnified a localized feud into one including supporters from the Electorate of the Palatinate

The Electoral Palatinate (german: Kurpfalz) or the Palatinate (), officially the Electorate of the Palatinate (), was a state that was part of the Holy Roman Empire. The electorate had its origins under the rulership of the Counts Palatine o ...

and Dutch, Scots, and English mercenaries on the Protestant side, and Bavarian and papal mercenaries on the Catholic side. The conflict coincided with the Dutch Revolt, 1568–1648, encouraging the participation of the rebellious Dutch provinces and the Spanish. In 1586, the conflict expanded further, with the direct involvement of Spanish troops and Italian mercenaries on the Catholic side, and financial and diplomatic support from Henry III of France and Elizabeth I of England

Elizabeth I (7 September 153324 March 1603) was Queen of England and Ireland from 17 November 1558 until her death in 1603. Elizabeth was the last of the five House of Tudor monarchs and is sometimes referred to as the "Virgin Queen".

Eli ...

on the Protestant side.

The war concluded with victory of the Catholic archbishop Ernst, who expelled the Protestant archbishop Gebhard from the Electorate. This outcome consolidated Wittelsbach

The House of Wittelsbach () is a German dynasty, with branches that have ruled over territories including Bavaria, the Palatinate, Holland and Zeeland, Sweden (with Finland), Denmark, Norway, Hungary (with Romania), Bohemia, the Electorate ...

authority in north-west Germany and encouraged a Catholic revival

The Counter-Reformation (), also called the Catholic Reformation () or the Catholic Revival, was the period of Catholic resurgence that was initiated in response to the Protestant Reformation. It began with the Council of Trent (1545–1563) ...

in the states along the lower Rhine

The Lower Rhine (german: Niederrhein; kilometres 660 to 1,033 of the river Rhine) flows from Bonn, Germany, to the North Sea at Hook of Holland, Netherlands (including the Nederrijn or "Nether Rhine" within the Rhine–Meuse–Scheldt delta); ...

. More broadly, the conflict set a precedent for foreign intervention in German religious and dynastic matters, which would be widely followed during the Thirty Years' War

The Thirty Years' War was one of the longest and most destructive conflicts in European history, lasting from 1618 to 1648. Fought primarily in Central Europe, an estimated 4.5 to 8 million soldiers and civilians died as a result of batt ...

(1618–48).

Background

Religious divisions in the Holy Roman Empire

Prior to the 16th century, theCatholic Church

The Catholic Church, also known as the Roman Catholic Church, is the List of Christian denominations by number of members, largest Christian church, with 1.3 billion baptized Catholics Catholic Church by country, worldwide . It is am ...

had been the sole official Christian faith in the Holy Roman Empire

The Holy Roman Empire was a political entity in Western, Central, and Southern Europe that developed during the Early Middle Ages and continued until its dissolution in 1806 during the Napoleonic Wars.

From the accession of Otto I in 962 unt ...

. Martin Luther

Martin Luther (; ; 10 November 1483 – 18 February 1546) was a German priest, theologian, author, hymnwriter, and professor, and Augustinian friar. He is the seminal figure of the Protestant Reformation and the namesake of Lutherani ...

's initial agenda called for the reform of the Church's doctrines and practices, but after his excommunication

Excommunication is an institutional act of religious censure used to end or at least regulate the communion of a member of a congregation with other members of the religious institution who are in normal communion with each other. The purpose ...

from the Church his ideas became embodied in an altogether separate religious movement, Lutheranism

Lutheranism is one of the largest branches of Protestantism, identifying primarily with the theology of Martin Luther, the 16th-century German monk and Protestant Reformers, reformer whose efforts to reform the theology and practice of the Cathol ...

. Initially dismissed by Holy Roman Emperor Charles V

Charles V, french: Charles Quint, it, Carlo V, nl, Karel V, ca, Carles V, la, Carolus V (24 February 1500 – 21 September 1558) was Holy Roman Emperor and Archduke of Austria from 1519 to 1556, King of Spain ( Castile and Aragon) fr ...

as an inconsequential argument between monks, the idea of a reformation of the Church's doctrines, considered infallible and sacrosanct by Catholic teaching, accentuated controversy and competition in many of the territories of the Holy Roman Empire and quickly devolved into armed factions that exacerbated existing social, political, and territorial grievances. These tensions were embodied in such alliances as the Protestant Schmalkaldic League, through which many of the Lutheran princes agreed to protect each other from encroachment on their territories and local authority; in retaliation, the princes that remained loyal to the Catholic Church formed the Holy League. By the mid-1530s, the German-speaking states of the Holy Roman Empire had devolved into armed factions determined by family ties, geographic needs, religious loyalties, and dynastic aspirations. The religious issue both accentuated and masked these secular conflicts.

Princes and clergy alike understood that institutional abuses hindered the practices of the faithful, but they disagreed on the solution to the problem. The Protestants believed a reform of doctrine was needed (especially regarding the Church's teachings on justification, indulgences, Purgatory

Purgatory (, borrowed into English via Anglo-Norman and Old French) is, according to the belief of some Christian denominations (mostly Catholic), an intermediate state after physical death for expiatory purification. The process of purgatory ...

, and the Papacy

The pope ( la, papa, from el, πάππας, translit=pappas, 'father'), also known as supreme pontiff ( or ), Roman pontiff () or sovereign pontiff, is the bishop of Rome (or historically the patriarch of Rome), head of the worldwide Cathol ...

) while those that remained Catholic wished to reform the morals of the clergy only, without sacrificing Catholic doctrine. Pope Paul III

Pope Paul III ( la, Paulus III; it, Paolo III; 29 February 1468 – 10 November 1549), born Alessandro Farnese, was head of the Catholic Church and ruler of the Papal States from 13 October 1534 to his death in November 1549.

He came to ...

convened a council to examine the problem in 1537 and instituted several internal, institutional reforms intended to obviate some of the most flagrant prebendary abuses, simony

Simony () is the act of selling church offices and roles or sacred things. It is named after Simon Magus, who is described in the Acts of the Apostles as having offered two disciples of Jesus payment in exchange for their empowering him to i ...

, and nepotism

Nepotism is an advantage, privilege, or position that is granted to relatives and friends in an occupation or field. These fields may include but are not limited to, business, politics, academia, entertainment, sports, fitness, religion, an ...

; despite efforts by both the Holy Roman Emperor Charles V and the Roman Pontiff

Roman or Romans most often refers to:

*Rome, the capital city of Italy

* Ancient Rome, Roman civilization from 8th century BC to 5th century AD

*Roman people, the people of ancient Rome

*''Epistle to the Romans'', shortened to ''Romans'', a lette ...

, unification of the two strands of belief foundered on different concepts of "Church" and the principle of justification. Catholics clung to the traditional teaching that the Catholic Church alone is the one true Church, while Protestants insisted that the Church Christ founded was invisible and not tied to any single religious institution on earth. Regarding justification, the Lutherans insisted that it occurred by faith alone

''Justificatio sola fide'' (or simply ''sola fide''), meaning justification by faith alone, is a soteriological doctrine in Christian theology commonly held to distinguish the Lutheran and Reformed traditions of Protestantism, among others, f ...

, while the Catholics upheld the traditional Catholic doctrine that justification involves both faith and active charity. The Schmalkaldic League called its own ecumenical council in 1537, and set forward several precepts of faith. When the delegates met in Regensburg in 1540–41, representatives agreed on the doctrine of faith and justification, but could not agree on sacraments, confession, absolution, and the definition of the church. Catholic and Lutheran adherents seemed further apart than ever; in only a few towns and cities were Lutherans and Catholics able to live together in even a semblance of harmony. By 1548, political disagreements overlapped with religious issues, making any kind of agreement seem remote.

In 1548 Charles declared an ''interreligio imperialis'' (also known as the Augsburg Interim) through which he sought to find some common ground for religious peace. This effort alienated both Protestant and Catholic princes and the papacy; even Charles, whose decree it was, was unhappy with the political and diplomatic dimensions of what amounted to half of a religious settlement. The 1551–52 sessions convened by Pope Julius III

Pope Julius III ( la, Iulius PP. III; it, Giulio III; 10 September 1487 – 23 March 1555), born Giovanni Maria Ciocchi del Monte, was head of the Catholic Church and ruler of the Papal States from 7 February 1550 to his death in March 155 ...

at the supposedly ecumenical Council of Trent

The Council of Trent ( la, Concilium Tridentinum), held between 1545 and 1563 in Trent (or Trento), now in northern Italy, was the 19th ecumenical council of the Catholic Church. Prompted by the Protestant Reformation, it has been described a ...

solved none of the larger religious issues but simply restated Catholic teaching and condemned Protestant teaching as heresies.

Overcoming religious division

Charles' interim solution failed. He ordered a general Diet in Augsburg at which the various states would discuss the religious problem and its solution. He himself did not attend, and delegated authority to his brother, Ferdinand, to "act and settle" disputes of territory, religion, and local power. At the conference, Ferdinand cajoled, persuaded, and threatened the various representatives into agreement on three important principles. The principle of ''cuius regio, eius religio

() is a Latin phrase which literally means "whose realm, their religion" – meaning that the religion of the ruler was to dictate the religion of those ruled. This legal principle marked a major development in the collective (if not individual ...

'' provided for internal religious unity within a state: The religion of the prince became the religion of the state and all its inhabitants. Those inhabitants who could not conform to the prince's religion were allowed to leave, an innovative idea in the 16th century; this principle was discussed at length by the various delegates, who finally reached agreement on the specifics of its wording after examining the problem and the proposed solution from every possible angle. The second principle covered the special status of the ecclesiastical states, called the ecclesiastical reservation

The ' ( Latin, "ecclesiastical reservation"; ) was a provision of the Peace of Augsburg of 1555. It exempted ecclesiastical lands from the principle of ' ( Latin: whose land, his religion), which the Peace established for all hereditary dyn ...

, or ''reservatum ecclesiasticum''. If the prelate of an ecclesiastic state changed his religion, the men and women living in that state did not have to do so. Instead, the prelate was expected to resign from his post, although this was not spelled out in the agreement. The third principle, known as '' Ferdinand's Declaration'', exempted knights and some of the cities from the requirement of religious uniformity, if the reformed religion had been practiced there since the mid-1520s, allowing for a few mixed cities and towns where Catholics and Lutherans had lived together. It also protected the authority of the princely families, the knights, and some of the cities to determine what religious uniformity meant in their territories. Ferdinand inserted this at the last minute, on his own authority.

Remaining problems

After 1555, the Peace of Augsburg became the legitimating legal document governing the co-existence of the Lutheran and Catholic faiths in the German lands of the Holy Roman Empire, and it served to ameliorate many of the tensions between followers of the so-called Old Faith and the followers of Luther, but it had two fundamental flaws. First, Ferdinand had rushed the article on ''ecclesiastical reservation'' through the debate; it had not undergone the scrutiny and discussion that attended the widespread acceptance and support of ''cuius regio, eius religio''. Consequently, its wording did not cover all, or even most, potential legal scenarios. The ''Declaratio Ferdinandei'' was not debated in plenary session at all; using his authority to "act and settle," Ferdinand had added it at the last minute, responding to lobbying by princely families and knights. While these specific failings came back to haunt the Empire in subsequent decades, perhaps the greatest weakness of the Peace of Augsburg was its failure to take into account the growing diversity of religious expression emerging in the evangelical (Lutheran) and Reformed traditions. Other confessions had acquired popular, if not legal, legitimacy in the intervening decades and by 1555, the reforms proposed by Luther were no longer the only possibilities of religious expression: Anabaptists, such as the Frisian Menno Simons (1492–1559) and his followers; the followers ofJohn Calvin

John Calvin (; frm, Jehan Cauvin; french: link=no, Jean Calvin ; 10 July 150927 May 1564) was a French theologian, pastor and reformer in Geneva during the Protestant Reformation. He was a principal figure in the development of the system ...

, who were particularly strong in the southwest and the northwest; and the followers of Huldrych Zwingli were excluded from considerations and protections under the Peace of Augsburg. According to the Augsburg agreement, their religious beliefs remained heretical.

Charles V's abdication

In 1556, amid great pomp, and leaning on the shoulder of one of his favorites (the 24-year-old William, Count of Nassau and Orange), Charles gave away his lands and his offices. TheSpanish Empire

The Spanish Empire ( es, link=no, Imperio español), also known as the Hispanic Monarchy ( es, link=no, Monarquía Hispánica) or the Catholic Monarchy ( es, link=no, Monarquía Católica) was a colonial empire governed by Spain and its prede ...

, which included Spain, the Netherlands, Naples

Naples (; it, Napoli ; nap, Napule ), from grc, Νεάπολις, Neápolis, lit=new city. is the regional capital of Campania and the third-largest city of Italy, after Rome and Milan, with a population of 909,048 within the city's adm ...

, Milan

Milan ( , , Lombard: ; it, Milano ) is a city in northern Italy, capital of Lombardy, and the second-most populous city proper in Italy after Rome. The city proper has a population of about 1.4 million, while its metropolitan city ...

, and Spain's possessions in the Americas

The Americas, which are sometimes collectively called America, are a landmass comprising the totality of North America, North and South America. The Americas make up most of the land in Earth's Western Hemisphere and comprise the New World. ...

, went to his son, Philip. His brother, Ferdinand, who had negotiated the treaty in the previous year, was already in possession of the Austrian lands and was also the obvious candidate to succeed Charles as Holy Roman Emperor.

Charles' choices were appropriate. Philip was culturally Spanish: he was born in Valladolid

Valladolid () is a municipality in Spain and the primary seat of government and de facto capital of the autonomous community of Castile and León. It is also the capital of the province of the same name. It has a population around 300,000 peop ...

and raised in the Spanish court, his native tongue was Spanish, and he preferred to live in Spain. Ferdinand was familiar with, and to, the other princes of the Holy Roman Empire. Although he too had been born in Spain, he had administered his brother's affairs in the Empire since 1531. Some historians maintain Ferdinand had also been touched by the reformed philosophies, and was probably the closest the Holy Roman Empire ever came to a Protestant emperor; he remained at least nominally a Catholic throughout his life, although reportedly he refused last rites on his deathbed. Other historians maintain that while Ferdinand was a practicing Catholic, unlike his brother he considered religion to be outside the political sphere.

Charles' abdication had far-reaching consequences in imperial diplomatic relations with France and the Netherlands, particularly in his allotment of the Spanish kingdom to Philip. In France, the kings and their ministers grew increasingly uneasy about Habsburg encirclement and sought allies against Habsburg hegemony from among the border German territories; they were even prepared to ally with some of the Protestant kings. In the Netherlands, Philip's ascension in Spain raised particular problems; for the sake of harmony, order, and prosperity, Charles had not oppressed the Reformation as harshly there as did Philip, and Charles had even tolerated a high level of local autonomy. An ardent Catholic and rigidly autocratic prince, Philip pursued an aggressive political, economic, and religious policy toward the Dutch, resulting in their rebellion shortly after he became king. Philip's militant response meant the occupation of much of the upper provinces by troops of, or hired by, Habsburg Spain

Habsburg Spain is a contemporary historiographical term referring to the huge extent of territories (including modern-day Spain, a piece of south-east France, eventually Portugal, and many other lands outside of the Iberian Peninsula) ruled be ...

and the constant ebb and flow of Spanish men and provisions over the Spanish road from northern Italy, through the Burgundian lands, into and from Flanders.

Cause of the war

As an ecclesiastical principality of theHoly Roman Empire

The Holy Roman Empire was a political entity in Western, Central, and Southern Europe that developed during the Early Middle Ages and continued until its dissolution in 1806 during the Napoleonic Wars.

From the accession of Otto I in 962 unt ...

, the Electorate of Cologne (german: Kurfürstentum Köln or ') included the temporal possessions of the Archbishop of Cologne (german: Erzbistum Köln): the so-called ''Oberstift'' (the southern part of the Electorate), the northern section, called the ''Niederstift'', the fiefdom of Vest Recklinghausen

Vest Recklinghausen was an ecclesiastical territory in the Holy Roman Empire, located in the center of today's North Rhine-Westphalia. The rivers Emscher and Lippe formed the border with the County of Mark and Essen Abbey in the south, and to t ...

and the Duchy of Westphalia

The Duchy of Westphalia (german: Herzogtum Westfalen) was a historic territory in the Holy Roman Empire, which existed from 1102 to 1803. It was located in the greater region of Westphalia, originally one of the three main regions in the Germ ...

, plus several small uncontiguous territories separated from the Electorate by the neighboring Duchies of Cleves, Berg, Julich and Mark. Encircled by the electoral territory, Cologne

Cologne ( ; german: Köln ; ksh, Kölle ) is the largest city of the German western state of North Rhine-Westphalia (NRW) and the fourth-most populous city of Germany with 1.1 million inhabitants in the city proper and 3.6 millio ...

was part of the archdiocese but not among the Elector's temporal possessions. The Electorate was ruled by an archbishop prince-elector

The prince-electors (german: Kurfürst pl. , cz, Kurfiřt, la, Princeps Elector), or electors for short, were the members of the electoral college that elected the emperor of the Holy Roman Empire.

From the 13th century onwards, the princ ...

of the empire. As an archbishop, he was responsible for the spiritual leadership of one of the richest sees in the Empire, and entitled to draw on its wealth. As a prince-prelate, he stood in the highest social category of the Empire, with specific and expansive legal, economic, and juridical rights. As an Elector, he was one of the men who elected the Holy Roman Emperor from among a group of imperial candidates.

The Electorate obtained its name from the city, and Cologne

Cologne ( ; german: Köln ; ksh, Kölle ) is the largest city of the German western state of North Rhine-Westphalia (NRW) and the fourth-most populous city of Germany with 1.1 million inhabitants in the city proper and 3.6 millio ...

had served as the capital of the archbishopric until 1288. After that, the archbishop and Prince-elector used the smaller cities of Bonn

The federal city of Bonn ( lat, Bonna) is a city on the banks of the Rhine in the German state of North Rhine-Westphalia, with a population of over 300,000. About south-southeast of Cologne, Bonn is in the southernmost part of the Rhine-Ru ...

, south of Cologne, and Brühl, south of Cologne, on the Rhine River, as his capital and residence; by 1580, both his residence and the capital were located in Bonn. Although the city of Cologne obtained its status as a free imperial city

In the Holy Roman Empire, the collective term free and imperial cities (german: Freie und Reichsstädte), briefly worded free imperial city (', la, urbs imperialis libera), was used from the fifteenth century to denote a self-ruling city that ...

in 1478, the Archbishop of Cologne retained judicial rights in the city; he acted as a Vogt

During the Middle Ages, an (sometimes given as modern English: advocate; German: ; French: ) was an office-holder who was legally delegated to perform some of the secular responsibilities of a major feudal lord, or for an institution such as ...

, or reeve, and reserved the right of blood justice, or ''Blutgericht''; only he could impose the so-called blood punishments, which included capital punishments, but also physical punishments that drew blood. Regardless of his position as judge, he could not enter the city of Cologne except under special circumstances, and between the city council

A municipal council is the legislative body of a municipality or local government area. Depending on the location and classification of the municipality it may be known as a city council, town council, town board, community council, rural coun ...

and the elector-archbishop, a politically and diplomatically precarious and usually adversarial relationship developed over the centuries. (See also History of Cologne for more details.)

The position of archbishop was usually held by a scion of nobility, and not necessarily a priest; this widespread practice allowed younger sons of noble houses to find prestigious and financially secure positions without the requirements of priesthood. The archbishop and prince-elector was chosen by the cathedral chapter

According to both Catholic and Anglican canon law, a cathedral chapter is a college of clerics ( chapter) formed to advise a bishop and, in the case of a vacancy of the episcopal see in some countries, to govern the diocese during the vacancy. ...

, the members of which also served as his advisers. As members of a cathedral chapter, they participated in the Mass

Mass is an intrinsic property of a body. It was traditionally believed to be related to the quantity of matter in a physical body, until the discovery of the atom and particle physics. It was found that different atoms and different ele ...

, or sang the Mass; in addition, they performed other duties as needed. They were not required to be priests but they could, if they wished, take Holy orders. As prebendaries, they received stipends from cathedral income; depending on the location and wealth of the cathedral, this could amount to substantial annual income. In the Electorate, the Chapter included 24 canons of various social ranks; they each had a place in the choir, based on their rank, which in turn was usually derived from the social standing of their families.

Election of 1577

When his nephew, Arnold, died without issue, Salentin von Isenburg-Grenzau (1532–1610) resigned from the office of Elector (September 1577) and, in December, married Antonia Wilhelmine d'Arenburg, sister of Charles d'Ligne, Prince of Arenberg. Salentin's resignation required the election of a new archbishop and prince-elector from among the Cathedral Chapter. Two candidates emerged. Gebhard (1547–1601) was the second son of William, Truchsess of Waldburg, known as William the younger, and Johanna von Fürstenberg. He was descended from the ''Jacobin'' line of theHouse of Waldburg

The House of Waldburg is a princely family of Upper Swabia, founded some time previous to the 12th century; some cadet lineages are comital families.

Eberhard von Tanne-Waldburg (? - 1234) was the steward, or '' seneschal'', and adviser of the ...

; his uncle was a cardinal, and his family had significant imperial contacts. The second candidate, Ernst of Bavaria (1554–1612), was the third son of Albert V, Duke of Bavaria. As a member of the powerful House of Wittelsbach, Ernst could marshal support from his extensive family connections throughout the Catholic houses of the empire; he also had contacts in important canonic establishments at Salzburg, Trier, Würzburg, and Münster that could exert collateral pressure.

Ernst had been a canon at Cologne since 1570. He had the support of the neighboring Duke of Jülich and several allies within the Cathedral Chapter. Although supported by both the papacy and his influential father, a 1571 effort to secure for him the office of coadjutor of the electorate of Cologne had failed once Salentin had agreed to abide by the Trentine proceedings; as the coadjutor bishop, Ernst would have been well-positioned to present himself as Salentin's logical successor. Since then, however, he had advanced in other sees, becoming bishop of Liège

Liège ( , , ; wa, Lîdje ; nl, Luik ; german: Lüttich ) is a major city and municipality of Wallonia and the capital of the Belgian province of Liège.

The city is situated in the valley of the Meuse, in the east of Belgium, not far fro ...

, Freising

Freising () is a university town in Bavaria, Germany, and the capital of the Freising ''Landkreis'' (district), with a population of about 50,000.

Location

Freising is the oldest town between Regensburg and Bolzano, and is located on the ...

, and Hildesheim

Hildesheim (; nds, Hilmessen, Hilmssen; la, Hildesia) is a city in Lower Saxony, Germany with 101,693 inhabitants. It is in the district of Hildesheim, about southeast of Hanover on the banks of the Innerste River, a small tributary of the ...

, important strongholds of Counter-Reformation Catholicism. He was a career cleric, not necessarily qualified to be an archbishop on the basis of his theological erudition, but by his family connections. His membership in several chapters extended the family influence, and his status as a prebendary gave him a portion of revenues from several cathedrals. He had been educated by Jesuits

, image = Ihs-logo.svg

, image_size = 175px

, caption = ChristogramOfficial seal of the Jesuits

, abbreviation = SJ

, nickname = Jesuits

, formation =

, founders = ...

and the papacy considered collaboration with his family as a means to limit the spread of Lutheranism and Calvinism in the northern provinces.

Also a younger son, Gebhard had prepared for an ecclesiastical career with a broad, Humanist education; apart from his native German, he had learned several languages (including Latin, Italian, French), and studied history and theology. After studying at the universities of Dillingen, Ingolstadt

Ingolstadt (, Austro-Bavarian: ) is an independent city on the Danube in Upper Bavaria with 139,553 inhabitants (as of June 30, 2022). Around half a million people live in the metropolitan area. Ingolstadt is the second largest city in Upper Ba ...

, Perugia

Perugia (, , ; lat, Perusia) is the capital city of Umbria in central Italy, crossed by the River Tiber, and of the province of Perugia.

The city is located about north of Rome and southeast of Florence. It covers a high hilltop and part ...

, Louvain

Leuven (, ) or Louvain (, , ; german: link=no, Löwen ) is the capital and largest city of the province of Flemish Brabant in the Flemish Region of Belgium. It is located about east of Brussels. The municipality itself comprises the historic c ...

, and elsewhere, he began his ecclesiastical career in 1560 at Augsburg

Augsburg (; bar , Augschburg , links=https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Swabian_German , label=Swabian German, , ) is a city in Swabia, Bavaria, Germany, around west of Bavarian capital Munich. It is a university town and regional seat of the ' ...

. His conduct at Augsburg caused some scandal; the bishop, his uncle, petitioned the Duke of Bavaria to remonstrate with him about it, which apparently led to some improvement in his behavior. In 1561, he became a deacon at Cologne Cathedral (1561–77), a canon of St. Gereon, the basilica in Cologne (1562–67), a canon in Strassburg (1567–1601), in Ellwangen (1567–83), and in Würzburg (1569–70). In 1571, he became deacon of Strassburg Cathedral, a position he held until his death. In 1576, by papal nomination, he also became provost of the Cathedral in Augsburg. Similar to his opponent, these positions brought him influence and wealth; they had little to do with his priestly character.

If the election had been left to the papacy, Ernst would have been the choice, but the Pope was not a member of the Cathedral Chapter and Gebhard had the support of several of the Catholic, and all the Protestant, canons in the Chapter. In December 1577, he was chosen Elector and Archbishop of Cologne after a spirited contest with the papacy's candidate, Ernst: Gebhard won the election by two votes. Although it was not required of him, Gebhard agreed to undergo priestly ordination; he was duly consecrated in March 1578, and swore to uphold the Council of Trent's decrees.

Gebhard's conversion

Agnes von Mansfeld-Eisleben (1551–1637) was a Protestant canoness at the cloister in Gerresheim, today a district ofDüsseldorf

Düsseldorf ( , , ; often in English sources; Low Franconian and Ripuarian: ''Düsseldörp'' ; archaic nl, Dusseldorp ) is the capital city of North Rhine-Westphalia, the most populous state of Germany. It is the second-largest city in ...

. Her family was a cadet line of the old House of Mansfeld which, by the mid-16th century, had lost much of its affluence, but not its influence. The Mansfeld-Eisleben line retained significant authority in its district; several of Agnes' cousins and uncles had signed the Book of Concord

''The Book of Concord'' (1580) or ''Concordia'' (often referred to as the ''Lutheran Confessions'') is the historic doctrinal standard of the Lutheran Church, consisting of ten credal documents recognized as authoritative in Lutheranism since ...

, and the family exercised considerable influence in Reformation affairs. She had been raised in Eisleben

Eisleben is a town in Saxony-Anhalt, Germany. It is famous as both the hometown of the influential theologian Martin Luther and the place where he died; hence, its official name is Lutherstadt Eisleben. First mentioned in the late 10th century, ...

, the town in which Martin Luther had been born. The family's estates were located in Saxony, but Agnes' sister lived in the city of Cologne, married to the ''Freiherr'' (or Baron

Baron is a rank of nobility or title of honour, often hereditary, in various European countries, either current or historical. The female equivalent is baroness. Typically, the title denotes an aristocrat who ranks higher than a lord or kn ...

), Peter von Kriechingen. Although a member of the Gerresheim cloister, Agnes was free during her days to go where she wished. Reports differ on how she came to Gebhard's notice. Some say he saw her on one of her visits to her sister in Cologne. Others claim he noticed her during a religious procession. Regardless, in late 1579 or early 1580, she attracted Gebhard's notice. He sought her out, and they started a liaison. Two of her brothers, Ernst and Hoyer Christoph, soon visited Gebhard at the archbishop's residence to discuss a marriage. "Gebhard's Catholic belief, which was by no means based on his innermost conviction, started to waver when he had to decide whether to renounce the bishop's mitre and stay faithful to the woman he loved, or to renounce his love and remain a member of the church hierarchy." While he considered this, rumors of his possible conversion flew throughout the Electorate.

The mere possibility of Gebhard's conversion caused consternation in the Electorate, in the Empire, and in such European states as England and France. Gebhard considered his options, and listened to his advisers, chief among them his brother Karl, Truchsess von Waldburg (1548–1593), and Adolf, Count von Neuenahr (1545–1589). His opponents in the Cathedral Chapter enlisted external support from the Wittelsbachs in Bavaria and from the Pope. Diplomats shuttled from court to court through the Rhineland, bearing pleas to Gebhard to consider the outcome of a conversion, and how it would destroy the Electorate. These diplomats assured him of support for his cause should he convert and hold the Electorate and threats to destroy him if he did convert. The magistrates of Cologne vehemently opposed any possible conversion and the extension of parity to Protestants in the archdiocese. His Protestant supporters told Gebhard that he could marry the woman and keep the Electorate, converting it into a dynastic duchy. Throughout the Electorate, and on its borders, his supporters and opponents gathered their troops, armed their garrisons, stockpiled foodstuffs, and prepared for war. On 19 December 1582, Gebhard announced his conversion, from, as he phrased it, the "darkness of the papacy to the Light" of the Word of God.

Implications of his conversion

The conversion of the Archbishop of Cologne to Protestantism triggered religious and political repercussions throughout the Holy Roman Empire. His conversion had widespread implications for the future of the Holy Roman Empire's electoral process established by the Golden Bull of 1356. In this process, seven Imperial Electors—the four secular electors ofBohemia

Bohemia ( ; cs, Čechy ; ; hsb, Čěska; szl, Czechy) is the westernmost and largest historical region of the Czech Republic. Bohemia can also refer to a wider area consisting of the historical Lands of the Bohemian Crown ruled by the Bohem ...

, Brandenburg

Brandenburg (; nds, Brannenborg; dsb, Bramborska ) is a state in the northeast of Germany bordering the states of Mecklenburg-Vorpommern, Lower Saxony, Saxony-Anhalt, and Saxony, as well as the country of Poland. With an area of 29,480 squ ...

, the Palatinate

The Palatinate (german: Pfalz; Palatine German: ''Palz'') is a region of Germany. In the Middle Ages it was known as the Rhenish Palatinate (''Rheinpfalz'') and Lower Palatinate (''Unterpfalz''), which strictly speaking designated only the we ...

, and Saxony

Saxony (german: Sachsen ; Upper Saxon German, Upper Saxon: ''Saggsn''; hsb, Sakska), officially the Free State of Saxony (german: Freistaat Sachsen, links=no ; Upper Saxon: ''Freischdaad Saggsn''; hsb, Swobodny stat Sakska, links=no), is a ...

; and the three ecclesiastical electors of Mainz

Mainz () is the capital and largest city of Rhineland-Palatinate, Germany.

Mainz is on the left bank of the Rhine, opposite to the place that the Main joins the Rhine. Downstream of the confluence, the Rhine flows to the north-west, with Ma ...

, Trier, and Cologne

Cologne ( ; german: Köln ; ksh, Kölle ) is the largest city of the German western state of North Rhine-Westphalia (NRW) and the fourth-most populous city of Germany with 1.1 million inhabitants in the city proper and 3.6 millio ...

—selected an emperor. The presence of at least three inherently ''Catholic'' electors, who collectively governed some of the most prosperous ecclesiastical territories in the Empire, guaranteed the delicate balance of Catholics and Protestants in the voting; only one other elector needed to vote for a Catholic candidate, ensuring that future emperors would remain in the so-called Old Faith. The possibility of one of those electors shifting to the Protestant side, ''and'' of that elector producing an heir to perpetuate this shift, would change the balance in the electoral college in favor of the Protestants.

The conversion of the ecclesiastic see to a dynastic realm ruled by a Protestant prince challenged the principle of ecclesiastical reservation

The ' ( Latin, "ecclesiastical reservation"; ) was a provision of the Peace of Augsburg of 1555. It exempted ecclesiastical lands from the principle of ' ( Latin: whose land, his religion), which the Peace established for all hereditary dyn ...

, which was intended to preserve the ecclesiastical electorates from this very possibility. The difficulties of such a conversion had been faced before: Hermann von Wied

Hermann of Wied ( German: ''Hermann von Wied'') (14 January 1477 – 15 August 1552) was the Archbishop-Elector of Cologne from 1515 to 1546.

In 1521, he supported a punishment for German reformer Martin Luther, but later opened up one of the ...

, a previous prince-elector and archbishop in Cologne, had also converted to Protestantism, but had resigned from his office. Similarly, Gebhard's predecessor, Salentin von Isenburg-Grenzau had indeed married in 1577, but had resigned from the office prior to his marriage. Furthermore, the reason for his marriage—to perpetuate his house—differed considerably from Gebhard's. The House of Waldburg was in no apparent danger of extinction; Gebhard was one of six brothers, and only one other had chosen an ecclesiastical career. Unlike his abdicating predecessors, when Gebhard converted, he proclaimed the Reformation in the city of Cologne itself, angering Cologne's Catholic leadership and alienating the Catholic faction in the Cathedral Chapter. Furthermore, Gebhard adhered not to the teachings of Martin Luther, but to those of John Calvin

John Calvin (; frm, Jehan Cauvin; french: link=no, Jean Calvin ; 10 July 150927 May 1564) was a French theologian, pastor and reformer in Geneva during the Protestant Reformation. He was a principal figure in the development of the system ...

, a form of religious observation not approved by the Augsburg conventions of 1555. Finally, he made no move to resign from his position as Prince-elector.

Affairs became further complicated when, on 2 February 1583, also known as '' Candlemas'', Gebhard married Agnes von Mansfeld-Eisleben in a private house in Rosenthal, outside of Bonn. After the ceremony, the couple processed to the Elector's palace in Bonn, and held a great feast. Unbeknownst to them, while they celebrated their marriage, Frederick, Duke of Saxe-Lauenburg Frederick of Saxe-Lauenburg (german: Herzog Friederich von Sachsen, Engern und Westfalen, colloquially ''Sachsen-Lauenburg'') (1554–1586), was a cathedral canon at Strasbourg Minster, chorbishop at Cologne Cathedral and cathedral provost (Dompr ...

(1554–1586), who was also a member of the Cathedral Chapter, and his soldiers approached the fortified Kaiserswerth, across the river, and took the castle after a brief fight. When the citizens of Cologne heard the news, there was a great public exultation.

Two days after his marriage, Gebhard invested his brother Karl with the duties of ''Statthalter'' (governor) and charged him with the rule of Bonn. He and Agnes then traveled to Zweibrücken

Zweibrücken (; french: Deux-Ponts, ; Palatinate German: ''Zweebrigge'', ; literally translated as "Two Bridges") is a town in Rhineland-Palatinate, Germany, on the Schwarzbach river.

Name

The name ''Zweibrücken'' means 'two bridges'; old ...

and, from there, to the territory of Dillingen, near Solms-Braunfels

Solms-Braunfels was a County and later Principality with Imperial immediacy in what is today the federal Land of Hesse in Germany.

Solms-Braunfels was a partition of Solms, ruled by the House of Solms, and was raised to a Principality of t ...

, where the Count, a staunch supporter, would help him to raise funds and troops to hold the territory; Adolf, Count von Neuenahr returned to the Electorate to prepare for its defense.

Gebhard clearly intended to transform an important ecclesiastical territory into a secular, dynastic duchy. This problematic conversion would then bring the principle of ''cuius regio, eius religio

() is a Latin phrase which literally means "whose realm, their religion" – meaning that the religion of the ruler was to dictate the religion of those ruled. This legal principle marked a major development in the collective (if not individual ...

'' into play in the Electorate. Under this principle, all of Gebhard's subjects would be required to convert to his faith: ''his rule, his religion''. Furthermore, as a relatively young man, heirs would be expected. Gebhard and his young wife presented the very real possibility of successfully converting a rich, diplomatically important, and strategically placed ecclesiastical territory of a prince-prelate into a dynastic territory that carried with it one of the coveted offices of imperial elector.

Pope Gregory XIII excommunicated him in March 1583, and the Chapter deposed him, by electing in his place the 29-year-old canon, Ernst of Bavaria, brother of the pious William V, Duke of Bavaria. Ernst's election ensured the involvement of the powerful House of Wittelsbach in the coming contest.

Course of the war

The war had three phases. Initially it was a localized feud between supporters of Gebhard and those of the Catholic core of the Cathedral Chapter. With the election of Ernst of Bavaria as a competing archbishop, what had been a local conflict expanded in scale: Ernst's election guaranteed the military, diplomatic, and financial interest of the Wittelsbach family in the Electorate of Cologne's local affairs. After the deaths ofLouis VI, Elector Palatine

Louis VI, Elector Palatine (4 July 1539 in Simmern – 22 October 1583 in Heidelberg), was an Elector from the Palatinate-Simmern branch of the house of Wittelsbach. He was the first-born son of Frederick III, Elector Palatine and Marie of ...

in 1583 and William the Silent

William the Silent (24 April 153310 July 1584), also known as William the Taciturn (translated from nl, Willem de Zwijger), or, more commonly in the Netherlands, William of Orange ( nl, Willem van Oranje), was the main leader of the Dutch Re ...

in 1584, the conflict shifted gears again, as the two evenly matched combatants sought outside assistance to break the stalemate. Finally, the intervention of Alexander Farnese, Duke of Parma

Alexander Farnese ( it, Alessandro Farnese, es, Alejandro Farnesio; 27 August 1545 – 3 December 1592) was an Italian noble and condottiero and later a general of the Spanish army, who was Duke of Parma, Piacenza and Castro from 1586 to 1592 ...

, who had at his command the Spanish Army of Flanders, threw the balance of power in favor of the Catholic side. By 1588, Spanish forces had pushed Gebhard from the Electorate. In 1588 he took refuge in Strassburg, and the remaining Protestant strongholds of the Electorate fell to Parma's forces in 1589.

Cathedral feud

Although Gebhard had gathered some troops around him, he hoped to recruit support from the Lutheran princes.Lins,Cologne

. Unfortunately for him, he had converted to another branch of the Reformed faith; such cautious Lutheran princes as Augustus I, Elector of Saxony, balked at extending their military support to Calvinists and the Elector Palatine was unable to persuade them to join the cause. Gebhard had three primary supporters. His brother, Karl, had married Eleonore, Countess of

Hohenzollern

The House of Hohenzollern (, also , german: Haus Hohenzollern, , ro, Casa de Hohenzollern) is a German royal (and from 1871 to 1918, imperial) dynasty whose members were variously princes, electors, kings and emperors of Hohenzollern, Brandenb ...

(1551–after 1598), and Gebhard could hope that this family alliance with the power-hungry Hohenzollerns would help his cause. Another long-time ally and supporter Adolf, Count von Neuenahr, was a successful and cunning military commander whose army secured the northern part of the territory. Finally, John Casimir (1543–1592), the brother of the Elector Palatine, had expressed his support, and made a great show of force in the southern part of the Electorate.

In the first months after Gebhard's conversion, two competing armies rampaged throughout the southern portion of the Electoral territory in the destruction of the so-called Oberstift. Villages, abbeys and convents and several towns, were plundered and burned, by both sides; Linz am Rhein and Ahrweiler avoided destruction by swearing loyalty to Salentin. In the summer of 1583, Gebhard and Agnes took refuge, first at Vest in Vest Recklinghausen

Vest Recklinghausen was an ecclesiastical territory in the Holy Roman Empire, located in the center of today's North Rhine-Westphalia. The rivers Emscher and Lippe formed the border with the County of Mark and Essen Abbey in the south, and to t ...

, a fief

A fief (; la, feudum) was a central element in medieval contracts based on feudal law. It consisted of a form of property holding or other rights granted by an overlord to a vassal, who held it in fealty or "in fee" in return for a form ...

of the Electorate, and then in the Duchy of Westphalia

The Duchy of Westphalia (german: Herzogtum Westfalen) was a historic territory in the Holy Roman Empire, which existed from 1102 to 1803. It was located in the greater region of Westphalia, originally one of the three main regions in the Germ ...

, at Arensberg castle. In both territories, Gebhard set in motion as much of the Reformation as he could, although his soldiers indulged in a bout of iconoclasm and plundering.

Initially, despite a few setbacks, military action seemed to go in Gebhard's favor, until October 1583, when the Elector Palatine died, and Casimir disbanded his army and returned to his brother's court as guardian for the new duke, his 10-year-old nephew. In November 1583, from his castle Arensberg in Westphalia, he wrote to Francis Walsingham

Sir Francis Walsingham ( – 6 April 1590) was principal secretary to Queen Elizabeth I of England from 20 December 1573 until his death and is popularly remembered as her "spymaster".

Born to a well-connected family of gentry, Wal ...

, adviser and spymaster to Queen Elizabeth

Queen Elizabeth, Queen Elisabeth or Elizabeth the Queen may refer to:

Queens regnant

* Elizabeth I (1533–1603; ), Queen of England and Ireland

* Elizabeth II (1926–2022; ), Queen of the United Kingdom and other Commonwealth realms

* Queen ...

: "Our needs are pressing, and you alsinghamand the Queen's other virtuous counsellors we believe can aid us; moreover, since God has called us to a knowledge of Himself, we have heard from our counsellors that you love and further the service of God."

On the same day, Gebhard wrote also to the Archbishop of Canterbury and the Bishop of London, presenting his case: "Verily, the Roman Antichrist moves every stone to oppress us and our churches...." Two days later, he wrote a more lengthy letter to the Queen: "We therefore humbly pray your Majesty to lend us 10,000 angelots, and to send it speedily, that we may preserve our churches this winter from the invasion of the enemy; for if we lost Bonn, they would be in the greatest danger, while if God permits us to keep it, we hope, by his grace, that Antichrist and his agents will be foiled in their damnable attempts against those who call upon the true God."

Godesburg, a fortress a few kilometers from the Elector's capital city of Bonn, was taken by storm in late 1583 after a brutal month-long siege; when Bavarian cannonades failed to break the bastions, sappers tunneled under the thick walls and blew up the fortifications from below. The Catholic Archbishop's forces still could not break through the remains of the fortifications, so they crawled through the garderobe sluices (hence the name, ''Sewer War''). Upon taking the fortress, they killed every defender except four, a Captain of the Guard who could prove he was a citizen of Cologne, the son of an important Cologne politician, the commander, and his wife. The of road between Godesberg and Bonn was filled with so many troops that it looked like a military camp. At the same time, in one of the few set battles of the war, Gebhard's supporters won at Aalst (french: Alost) over the Catholic forces of the Frederick of Saxe-Lauenburg, who had raised his own army and had entered the fray of his own accord a few months earlier.

The Catholics offered Gebhard a great sum of money, which he refused, demanding instead, the restoration of his state. When further negotiations among the Electors and the Emperor at Frankfurt am Main

Frankfurt, officially Frankfurt am Main (; Hessian: , " Frank ford on the Main"), is the most populous city in the German state of Hesse. Its 791,000 inhabitants as of 2022 make it the fifth-most populous city in Germany. Located on it ...

, then at Muhlhausen in Westphalia, failed to reach an agreement settling the dispute, the Pope arranged for the support of several thousand Spanish troops in early 1584.

Engagement of outside military forces

The election of Ernst of Bavaria expanded the local feud into a more German-wide phenomenon. The pope committed 55,000 crowns to pay soldiers to fight for Ernst, and another 40,000 directly into the coffers of the new Archbishop. Under the command of his brother, Ernst's forces pushed their way into Westphalia, threatening Gebhard and Agnes at their stronghold at Arensburg. Gebhard and Agnes escaped to the rebellious provinces of the Netherlands with almost 1000 cavalry, where Prince William gave them a haven inDelft

Delft () is a city and municipality in the province of South Holland, Netherlands. It is located between Rotterdam, to the southeast, and The Hague, to the northwest. Together with them, it is part of both the Rotterdam–The Hague metropolita ...

. There, Gebhard solicited the impecunious William for troops and money. After William's assassination

Assassination is the murder of a prominent or important person, such as a head of state, head of government, politician, world leader, member of a royal family or CEO. The murder of a celebrity, activist, or artist, though they may not have ...

in July 1584, Gebhard wrote to Queen Elizabeth requesting assistance. Elizabeth responded toward the end of 1585, directing him to contact Robert Dudley, 1st Earl of Leicester

Robert Dudley, 1st Earl of Leicester, (24 June 1532 – 4 September 1588) was an English statesman and the favourite of Elizabeth I from her accession until his death. He was a suitor for the queen's hand for many years.

Dudley's youth was o ...

, her deputy with the rebellious Dutch, and recently commissioned as the commander-in-chief of her army in the Netherlands. Elizabeth had her own problems with adherents of her cousin Mary, Queen of Scots

Mary, Queen of Scots (8 December 1542 – 8 February 1587), also known as Mary Stuart or Mary I of Scotland, was Queen of Scotland from 14 December 1542 until her forced abdication in 1567.

The only surviving legitimate child of James V of S ...

, and the Spanish.

Stalemate

By late 1585, although Ernst's brother had made significant inroads into the Electorate of Cologne, both sides had reached an impasse. Sizable portions of the population subscribed to the Calvinist doctrine; to support them, Calvinist Switzerland and Strassburg furnished a steady stream of theologians, jurists, books, and ideas. The Calvinist barons and counts understood the danger of Spanish intervention: it meant the aggressive introduction of the Counter-Reformation in their territories. France, in the person of Henry III, was equally interested, since the encirclement of his Kingdom by Habsburgs was cause for concern. Another sizable portion of the electorate's populace adhered to the old faith, supported by Wittelsbach-funded Jesuits. The supporters of both sides committed atrocities of their own: in the city of Cologne, the mere rumor of Gebhard's approaching army caused rioters to murder several people suspected of sympathizing with the Protestant cause. Ernst depended on his brother and the Catholic barons in the Cathedral Chapter to hold the territory he acquired. In 1585,Münster

Münster (; nds, Mönster) is an independent city (''Kreisfreie Stadt'') in North Rhine-Westphalia, Germany. It is in the northern part of the state and is considered to be the cultural centre of the Westphalia region. It is also a state di ...

, Paderborn

Paderborn (; Westphalian: ''Patterbuorn'', also ''Paterboärn'') is a city in eastern North Rhine-Westphalia, Germany, capital of the Paderborn district. The name of the city derives from the river Pader and ''Born'', an old German term for t ...

, and Osnabrück succumbed to Ferdinand's energetic pursuit in the eastern regions of the electorate, and a short time later, Minden. With their help, Ernst could hold Bonn. Support from the city of Cologne itself was also secure. To oust Gebhard, though, Ernst ultimately had to appeal for aid to Alexander Farnese, Duke of Parma, who commanded Spanish forces in the Netherlands, namely the Army of Flanders.

Parma was more than willing to help. The Electorate, strategically important to Spain, offered another land route by which to approach the rebellious northern Provinces of the Netherlands. Although the Spanish road from Spain's holdings on the Mediterranean shores led to its territories in what is today Belgium, it was a long, arduous march, complicated by the provisioning of troops and the potentially hostile populations of the territories through which it passed. An alternative route on the Rhine promised better access to the Habsburg Netherlands. Furthermore, the presence of a Calvinist electorate almost on the Dutch border could delay their efforts to bring the rebellious Dutch back to the Spanish rule and the Catholic confession. Philip II and his generals could be convinced to support Ernst's cause for such considerations. Indeed, the process of intervention had started earlier. In 1581, Philip's forces, paid for by papal gold, had taken Aachen

Aachen ( ; ; Aachen dialect: ''Oche'' ; French and traditional English: Aix-la-Chapelle; or ''Aquisgranum''; nl, Aken ; Polish: Akwizgran) is, with around 249,000 inhabitants, the 13th-largest city in North Rhine-Westphalia, and the 28th ...

, which Protestants had seized; by the mid–1580s, the Duke of Parma's forces, encouraged by the Wittelsbachs and the Catholics in Cologne, had secured garrisons throughout the northern territories of the Electorate. By 1590, these garrisons gave Spain access to the northern provinces and Philip felt comfortable enough with his military access to the provinces, and with their isolation from possible support by German Protestants, to direct more of his attention to France, and less to his problems with the Dutch.

On the other side of the feud, to hold the territory, Gebhard needed the full support of his military brother and the very able Neuenahr. To push Ernst out, he needed additional support, which he had requested from Delft and from England. It was clearly in the interests of England and the Dutch to offer assistance; if the Dutch could not tie up the Spanish army in Flanders, and if that army needed a navy to supply it, Philip could not focus his attention on the English and the French. His own diplomats had sought to present his case as one of pressing concern to all Protestant princes: in November 1583, one of his advisers, Dr. Wenceslaus Zuleger, wrote to Francis Walsingham: "I assure you if the Elector of Cologne is not assisted, you will see that the war in the Low Countries will shortly spread over the whole of Germany." The support Gebhard received, in the form of troops from the Earl of Leicester, and from the Dutch, in the form of the mercenary Martin Schenck

Martin Schenck (January 24, 1848 – September 17, 1918) was an American civil engineer and politician from New York. He was New York State Engineer and Surveyor from 1892 to 1893.

Life

He was born on January 24, 1848 in Palatine Bridge, New ...

, had mixed results. Leicester's troops, professional and well-led, performed well but their usefulness was limited: Elizabeth's instructions to help Gebhard had not come with financial support and Leicester had sold his own plate and had exhausted his own personal credit while trying to field an army. Martin Schenck had seen considerable service in Spain's Army of Flanders, for the French king and for Parma himself. He was a skilled and charismatic soldier, and his men would do anything for him; reportedly, he could sleep in his saddle, and seemed indomitable in the field. Unfortunately, Schenck was little more than a land-pirate, a free-booter, and rascal, and ultimately he did Gebhard more harm than good, as his behavior in Westphalia and at the Battle of Werl demonstrated.

Sack of Westphalia

In late February 1586, Friedrich Cloedt, whom Gebhard had placed in command of Neuss, and Martin Schenck went to Westphalia at the head of 500 foot and 500 horse. After plundering

In late February 1586, Friedrich Cloedt, whom Gebhard had placed in command of Neuss, and Martin Schenck went to Westphalia at the head of 500 foot and 500 horse. After plundering Vest Recklinghausen

Vest Recklinghausen was an ecclesiastical territory in the Holy Roman Empire, located in the center of today's North Rhine-Westphalia. The rivers Emscher and Lippe formed the border with the County of Mark and Essen Abbey in the south, and to t ...

, on 1 March they captured Werl

Werl (; Westphalian: ''Wiärl'') is a town located in the district of Soest in North Rhine-Westphalia, Germany.

Geography

Werl is easily accessible because it is located between the Sauerland, Münsterland, and the Ruhr Area. The Hellweg r ...

through trickery. They loaded a train of wagons with soldiers and covered them with salt. When the wagons of salt were seen outside the city gates, they were immediately admitted, salt being a valued commodity. The "salted soldiers" then over-powered the guard and captured the town. Some of the defenders escaped to the citadel, and could not be dislodged. Claude de Berlaymont, also known as Haultpenne

Haultepenne Castle, also spelled ''Hautepenne Castle'' (French: ''Château de Hautepenne''), is a part medieval, part renaissance structure located in the village of Gleixhe in the municipality of Flémalle in Wallonia, Belgium. It is known f ...

after the name of his castle, collected his own force of 4000 and besieged Schenck and Cloedt in Werl. Attacked from the outside by Haultpenne, and from the inside by the soldiers in the citadel, Schenck and Cloedt broke out of the city with their soldiers on 3 March. Unable to break through the lines, they retreated into the city once more, but several of their soldiers did not make it into the city, and plundered the neighboring villages; 250 local residents were killed. On 8 March, Schenck and Cloedt loaded their wagons, this time with booty, took 30 magistrates as hostages, and attacked Haultpenne's force, killing about 500 of them, and losing 200 of their own. Included in the hostages were the ''Bürgermeister'' Johann von Pappen and several other high-ranking officials; although von Pappen died during the retreat, the remaining hostages were released after the payment of a high ransom. Schenck retreated to Venlo and Cloedt returned to the city of Neuss.

Spanish intervention

To some extent, the difficulties both Gebhard and Ernst faced in winning the war were the same the Spanish had in subduing the Dutch Revolt. The protraction of the Spanish and Dutch war—80 years of bitter fighting interrupted by periodic truces while both sides gathered resources—lay in the kind of war it was: enemies lived in fortified towns defended by Italian-style bastions, which meant the towns had to be taken and then fortified and maintained. For both Gebhard and Ernst, as for the Spanish commanders in the nearby Lowlands, winning the war meant not only mobilizing enough men to encircle a seemingly endless cycle of enemy artillery fortresses, but also maintaining the army one had and defending all one's own possessions as they were acquired. The Cologne War, similar to the Dutch Revolt in that respect, was also a war of sieges, not of assembled armies facing one another on the field of battle, nor of maneuver, feint, and parry that characterized wars two centuries earlier and later. These wars required men who could operate the machinery of war, which meant extensive economic resources for soldiers to build and operate the siege works, and a political and military will to keep the machinery of war operating. The Spanish faced another problem, distance, which gave them a distinct interest in intervening in the Cologne affair: the Electorate lay on the Rhine River, and the Spanish road.

To some extent, the difficulties both Gebhard and Ernst faced in winning the war were the same the Spanish had in subduing the Dutch Revolt. The protraction of the Spanish and Dutch war—80 years of bitter fighting interrupted by periodic truces while both sides gathered resources—lay in the kind of war it was: enemies lived in fortified towns defended by Italian-style bastions, which meant the towns had to be taken and then fortified and maintained. For both Gebhard and Ernst, as for the Spanish commanders in the nearby Lowlands, winning the war meant not only mobilizing enough men to encircle a seemingly endless cycle of enemy artillery fortresses, but also maintaining the army one had and defending all one's own possessions as they were acquired. The Cologne War, similar to the Dutch Revolt in that respect, was also a war of sieges, not of assembled armies facing one another on the field of battle, nor of maneuver, feint, and parry that characterized wars two centuries earlier and later. These wars required men who could operate the machinery of war, which meant extensive economic resources for soldiers to build and operate the siege works, and a political and military will to keep the machinery of war operating. The Spanish faced another problem, distance, which gave them a distinct interest in intervening in the Cologne affair: the Electorate lay on the Rhine River, and the Spanish road.

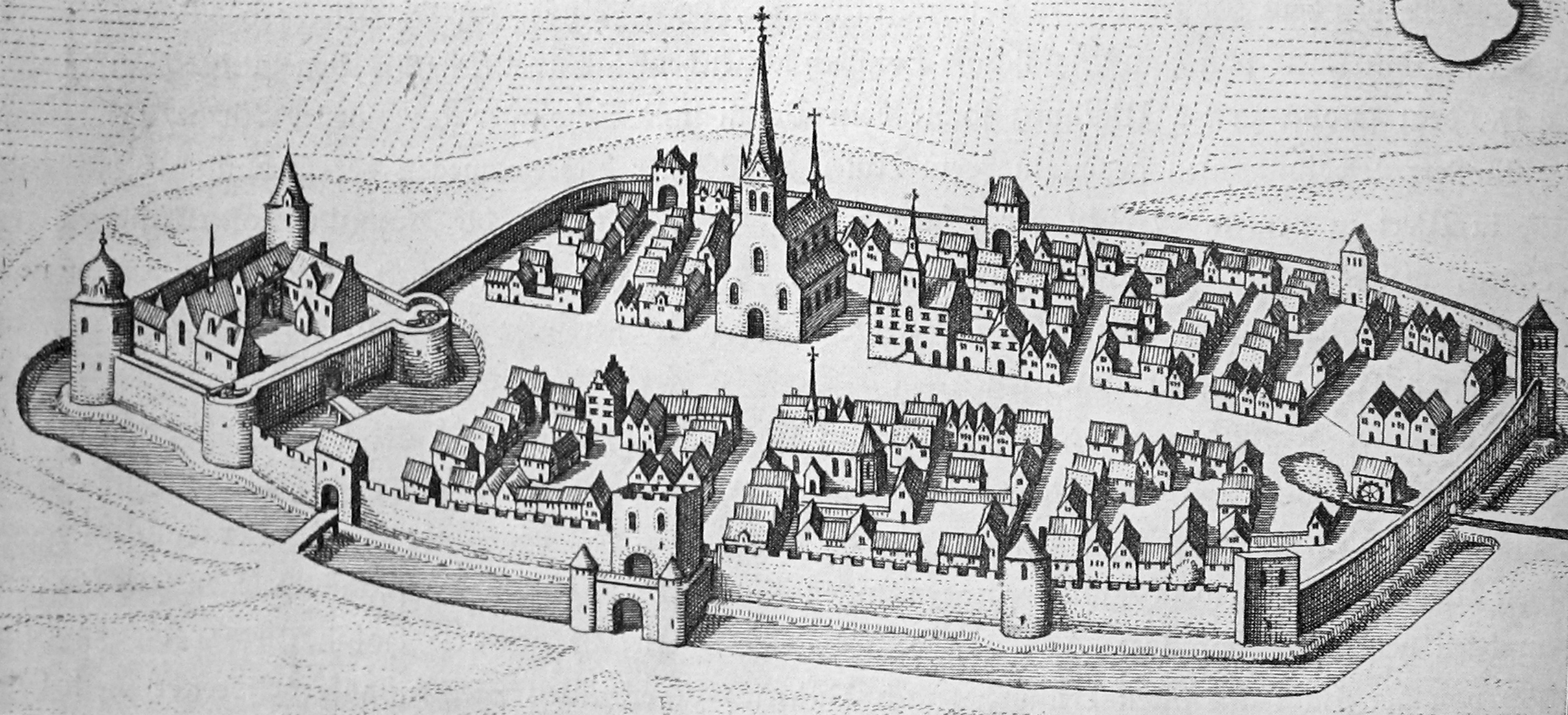

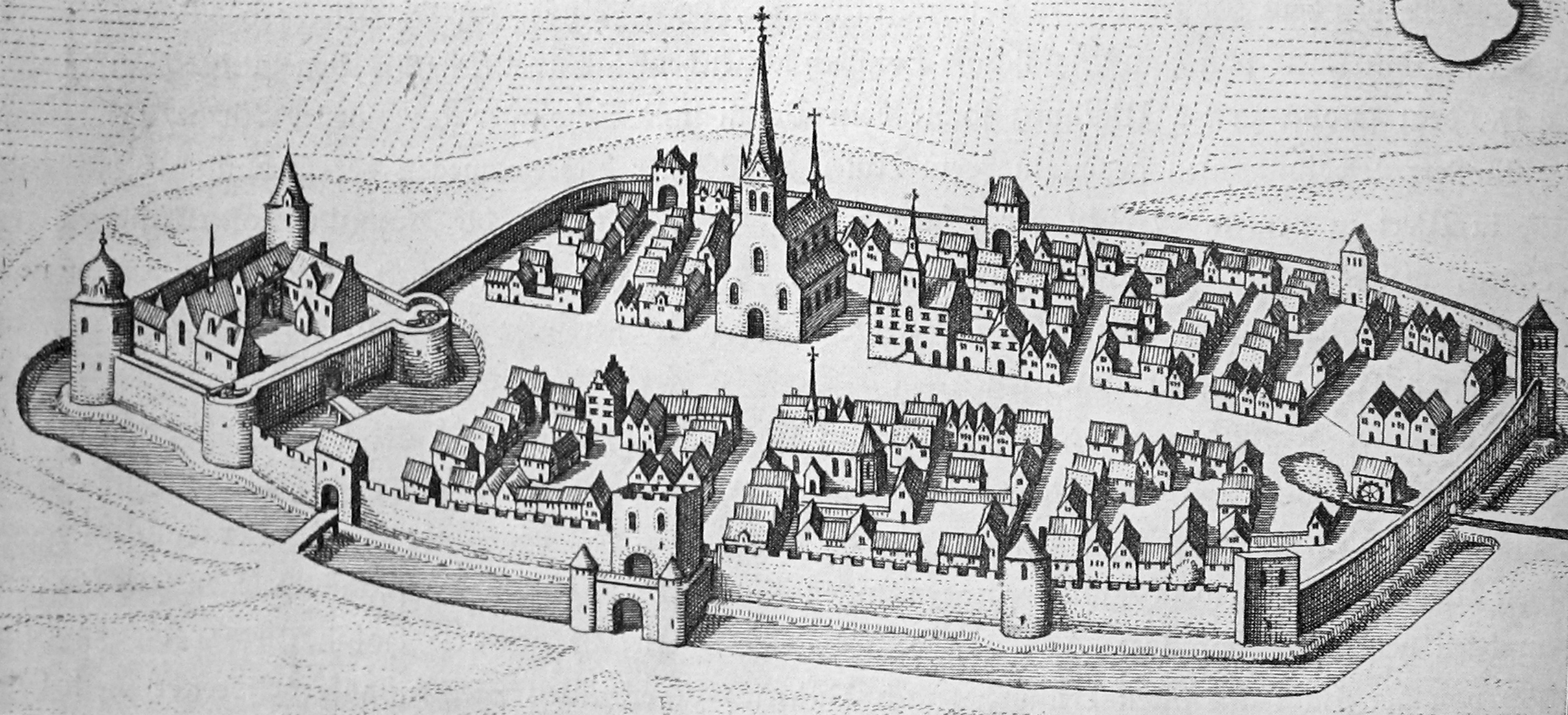

Razing of Neuss