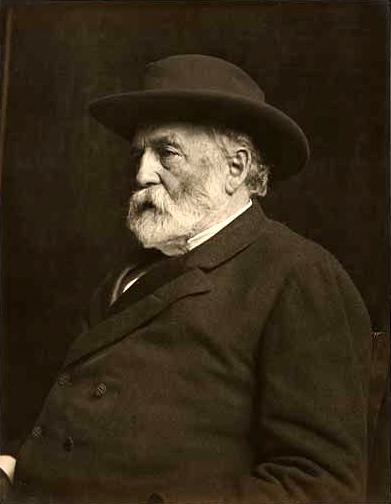

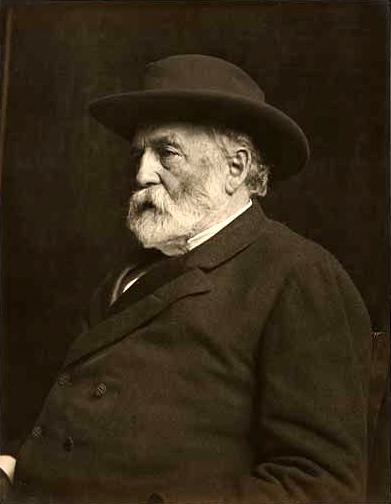

Collis P. Huntington on:

[Wikipedia]

[Google]

[Amazon]

Collis Potter Huntington (October 22, 1821 – August 13, 1900) was an American industrialist and railway magnate. He was one of the Big Four of western railroading (along with

netstate.com About this time, he visited rural Newport News Point in

Beginning in 1865, Huntington was also involved in the establishment of the

Beginning in 1865, Huntington was also involved in the establishment of the

Beginning in December 1880, he led the building of the C&O's

Beginning in December 1880, he led the building of the C&O's  Huntington did not neglect his namesake city at the other end of the C&O. In order to supply

Huntington did not neglect his namesake city at the other end of the C&O. In order to supply

Collis Huntington was the son of William and Elizabeth (Vincent) Huntington; born October 22, 1821, in Harwinton, Connecticut. His siblings were:

# Mary Huntington, born 17 February 1810; married 2 June 1840, Daniel Sammis of Warsaw, New York.

# Solon Huntington, born 13 January 1812.

# Rhoda Huntington, born 13 October 1814; married 10 May 1834, Riley Dunbar of Wolcottville.

# Phebe/Phoebe Huntington, born 17 September 1817; married 4 October 1840, Henry Pardee of

Collis Huntington was the son of William and Elizabeth (Vincent) Huntington; born October 22, 1821, in Harwinton, Connecticut. His siblings were:

# Mary Huntington, born 17 February 1810; married 2 June 1840, Daniel Sammis of Warsaw, New York.

# Solon Huntington, born 13 January 1812.

# Rhoda Huntington, born 13 October 1814; married 10 May 1834, Riley Dunbar of Wolcottville.

# Phebe/Phoebe Huntington, born 17 September 1817; married 4 October 1840, Henry Pardee of

in JSTOR

* Daggett, Stuart. "Huntington, Collis Potter," ''Dictionary of American biography '' (1932), vol. 5 * Deverell, William. ''Railroad Crossing: Californians and the Railroad, 1850–1910'' (1994

online

* Evans, Cerinda W. ''Collis Potter Huntington'' (2 vols., 1954), A major biograph

online volume 1

* Huddleston, Eugene L. "Huntington, Collis Potter"

* Lavender, David, ''The great persuader: the biography of Collis P. Huntington'', University Press of Colorado, 1998 reprint, first published 1970. * Lewis, Oscar. ''The Big Four: The story of Huntington, Stanford, Hopkins, and Crocker, and of the Building of the Central Pacific'' (1938) * Rayner, Richard, ''The Associates: Four Capitalists Who Created California'', Norton, 2007. * Williams, R. Hal. ''The Democratic Party and California Politics, 1880–1896'' (1973

online

"Corporations, Corruption, and the Modern Lobby: A Gilded Age Story of the West and the South in Washington, D.C."

''Southern Spaces'', video of lecture by Richard White, Stanford University, 16 April 2009. * * "Collis Potter Huntington" in

''Prominent and progressive Americans; an encyclopædia of contemporaneous biography''

Compiled by Mitchell Charles Harrison. Publisher: New York Tribune, 1902

Newport News

Huntington Hotel

San Francisco

Ellen M.H. Gates, Who's Who Poet

{{DEFAULTSORT:Huntington, Collis Potter American railway entrepreneurs 19th-century American railroad executives Southern Pacific Railroad people Businesspeople from Connecticut Businesspeople from San Francisco 1821 births 1900 deaths People from Harwinton, Connecticut Huntington, West Virginia Nob Hill, San Francisco Burials at Woodlawn Cemetery (Bronx, New York) 19th-century American philanthropists Huntington family

Leland Stanford

Amasa Leland Stanford (March 9, 1824June 21, 1893) was an American industrialist and politician. A member of the Republican Party, he served as the 8th governor of California from 1862 to 1863 and represented California in the United States Sen ...

, Mark Hopkins, and Charles Crocker

Charles Crocker (September 16, 1822 – August 14, 1888) was an American railroad executive who was one of the founders of the Central Pacific Railroad, which constructed the westernmost portion of the first transcontinental railroad, and took ...

) who invested in Theodore Judah

Theodore Dehone Judah (March 4, 1826 – November 2, 1863) was an American civil engineer who was a central figure in the original promotion, establishment, and design of the First transcontinental railroad. He found investors for what became t ...

's idea to build the Central Pacific Railroad

The Central Pacific Railroad (CPRR) was a rail company chartered by U.S. Congress in 1862 to build a railroad eastwards from Sacramento, California, to complete the western part of the " First transcontinental railroad" in North America. Incor ...

as part of the first U.S. transcontinental railroad

A transcontinental railroad or transcontinental railway is contiguous railroad trackage, that crosses a continental land mass and has terminals at different oceans or continental borders. Such networks can be via the tracks of either a single ...

. Huntington helped lead and develop other major interstate lines, such as the Southern Pacific Railroad

The Southern Pacific (or Espee from the railroad initials- SP) was an American Class I railroad network that existed from 1865 to 1996 and operated largely in the Western United States. The system was operated by various companies under the ...

and the Chesapeake & Ohio Railway

The Chesapeake and Ohio Railway was a Class I railroad formed in 1869 in Virginia from several smaller Virginia railroads begun in the 19th century. Led by industrialist Collis P. Huntington, it reached from Virginia's capital city of Richmond t ...

(C&O), which he was recruited to help complete. The C&O, completed in 1873, fulfilled a long-held dream of Virginians of a rail link from the James River

The James River is a river in the U.S. state of Virginia that begins in the Appalachian Mountains and flows U.S. Geological Survey. National Hydrography Dataset high-resolution flowline dataThe National Map , accessed April 1, 2011 to Chesap ...

at Richmond

Richmond most often refers to:

* Richmond, Virginia, the capital of Virginia, United States

* Richmond, London, a part of London

* Richmond, North Yorkshire, a town in England

* Richmond, British Columbia, a city in Canada

* Richmond, Californi ...

to the Ohio River Valley

The Ohio River is a long river in the United States. It is located at the boundary of the Midwestern and Southern United States, flowing southwesterly from western Pennsylvania to its mouth on the Mississippi River at the southern tip of Illinoi ...

. The new railroad facilities adjacent to the river there resulted in expansion of the former small town of Guyandotte, West Virginia

Guyandotte is a historic neighborhood in the city of Huntington, West Virginia, that previously existed as a separate town before annexation was completed by the latter. The neighborhood is home to many historic properties, and was first settled by ...

into part of a new city which was named Huntington in his honor.

Turning attention to the eastern end of the line at Richmond, Huntington directed the C&O's Peninsula Extension

The Peninsula Extension which created the Peninsula Subdivision of the Chesapeake and Ohio Railway (C&O) was the new railroad line on the Virginia Peninsula from Richmond to southeastern Warwick County. Its principal purpose was to provide an ...

in 1881–82, which opened a pathway for West Virginia

West Virginia is a state in the Appalachian, Mid-Atlantic and Southeastern regions of the United States.The Census Bureau and the Association of American Geographers classify West Virginia as part of the Southern United States while the ...

bituminous coal

Bituminous coal, or black coal, is a type of coal containing a tar-like substance called bitumen or asphalt. Its coloration can be black or sometimes dark brown; often there are well-defined bands of bright and dull material within the seams. It ...

to reach new coal pier A coal pier is a transloading facility designed for the transfer of coal between rail and ship.

The typical facility for loading ships consists of a holding area and a system of conveyors for transferring the coal to dockside and loading it into ...

s on the harbor of Hampton Roads

Hampton Roads is the name of both a body of water in the United States that serves as a wide channel for the James, Nansemond and Elizabeth rivers between Old Point Comfort and Sewell's Point where the Chesapeake Bay flows into the Atlantic ...

for export shipping. He also is credited with the development of Newport News Shipbuilding and Drydock Company, as well as the incorporation of Newport News, Virginia

Newport News () is an independent city in the U.S. state of Virginia. At the 2020 census, the population was 186,247. Located in the Hampton Roads region, it is the 5th most populous city in Virginia and 140th most populous city in the U ...

as a new independent city

An independent city or independent town is a city or town that does not form part of another general-purpose local government entity (such as a province).

Historical precursors

In the Holy Roman Empire, and to a degree in its successor states ...

. After his death, both his nephew Henry E. Huntington

Henry Edwards Huntington (February 27, 1850 – May 23, 1927) was an American railroad magnate and collector of art and rare books. Huntington settled in Los Angeles, where he owned the Pacific Electric Railway as well as substantial real estate ...

and his stepson Archer M. Huntington continued his work at Newport News. All three are considered founding fathers in the community, with local features named in honor of each.

Much of the railroad and industrial development which Collis P. Huntington envisioned and led are still important activities in the early 21st century. The Southern Pacific is now part of the Union Pacific Railroad

The Union Pacific Railroad , legally Union Pacific Railroad Company and often called simply Union Pacific, is a freight-hauling railroad that operates 8,300 locomotives over routes in 23 U.S. states west of Chicago and New Orleans. Union Paci ...

, and the C&O became part of CSX Transportation

CSX Transportation , known colloquially as simply CSX, is a Class I freight railroad operating in the Eastern United States and the Canadian provinces of Ontario and Quebec. The railroad operates approximately 21,000 route miles () of track. ...

, each major U.S. railroad systems. West Virginia coal is still transported by rail to be loaded onto colliers at Hampton Roads. Nearby, Huntington Ingalls Industries

HII (formerly Huntington Ingalls Industries, Inc.) is the largest military shipbuilding company in the United States as well as a provider of professional services to partners in government and industry. HII, ranked No. 371 on the Fortune 500, wa ...

operates the massive shipyard at Newport News.

From his base in Washington, Huntington was a lobbyist for the Central Pacific and the Southern Pacific in the 1870s and 1880s. The Big Four had built a powerful political machine, which he had a large role in running. He was generous in providing bribes to politicians and congressmen. Revelation of his misdeeds in 1883 made him one of the most hated railroad men in the country.

Huntington defended himself:

In 1968, Huntington was inducted into the Hall of Great Westerners

The Hall of Great Westerners was established by the National Cowboy & Western Heritage Museum in 1958. Located in Oklahoma City, Oklahoma, U.S., the Hall was created to celebrate the contributions of more than 200 men and women of the American ...

of the National Cowboy & Western Heritage Museum

The National Cowboy & Western Heritage Museum is a museum in Oklahoma City, Oklahoma, United States, with more than 28,000 Western and American Indian art works and artifacts. The facility also has the world's most extensive collection of Am ...

.

Biography

Education and early career

Collis Potter Huntington was born inHarwinton, Connecticut

Harwinton is a town in Litchfield County, Connecticut, United States. The population was 5,484 at the 2020 census. The high school is Lewis S. Mills.

History

The town incorporated in 1737. The name of the town alludes to Hartford and Windsor, Con ...

, on October 22, 1821. His family farmed and he grew up helping. In his early teens, he did farm chores and odd jobs for neighbors, saving his earnings. At age 16, he began traveling as a peddler

A peddler, in British English pedlar, also known as a chapman, packman, cheapjack, hawker, higler, huckster, (coster)monger, colporteur or solicitor, is a door-to-door and/or travelling vendor of goods.

In England, the term was mostly used f ...

.Collis Potter Huntington netstate.com About this time, he visited rural Newport News Point in

Warwick County, Virginia

Warwick County was a county in Southeast Virginia that was created from Warwick River Shire, one of eight created in the Virginia Colony in 1634. It became the City of Newport News on July 16, 1952. Located on the Virginia Peninsula on the no ...

in his travels as a salesman. He never forgot what he thought was the untapped potential of the area, where the James River

The James River is a river in the U.S. state of Virginia that begins in the Appalachian Mountains and flows U.S. Geological Survey. National Hydrography Dataset high-resolution flowline dataThe National Map , accessed April 1, 2011 to Chesap ...

emptied into the large harbor of Hampton Roads. In 1842 he and his brother Solon Huntington, of Oneonta, New York

Oneonta ( ) is a Administrative divisions of New York#City, city in southern Otsego County, New York, Otsego County, New York (state), New York, United States. It is one of the northernmost cities of the Appalachian Region. According to the 2020 ...

, established a successful business in Oneonta, selling general merchandise there until about 1848.

When Huntington saw opportunity in America's West, he set out for California

California is a state in the Western United States, located along the Pacific Coast. With nearly 39.2million residents across a total area of approximately , it is the most populous U.S. state and the 3rd largest by area. It is also the m ...

. He set up as a merchant in Sacramento

)

, image_map = Sacramento County California Incorporated and Unincorporated areas Sacramento Highlighted.svg

, mapsize = 250x200px

, map_caption = Location within Sacramento ...

at the start of the California Gold Rush

The California Gold Rush (1848–1855) was a gold rush that began on January 24, 1848, when gold was found by James W. Marshall at Sutter's Mill in Coloma, California. The news of gold brought approximately 300,000 people to California f ...

. Huntington succeeded in his California business. He teamed up with Mark Hopkins selling miners' supplies and other hardware.

Building the first U.S. transcontinental railroad

In the late 1850s, Huntington and Hopkins joined forces with two other successful businessmen,Leland Stanford

Amasa Leland Stanford (March 9, 1824June 21, 1893) was an American industrialist and politician. A member of the Republican Party, he served as the 8th governor of California from 1862 to 1863 and represented California in the United States Sen ...

and Charles Crocker

Charles Crocker (September 16, 1822 – August 14, 1888) was an American railroad executive who was one of the founders of the Central Pacific Railroad, which constructed the westernmost portion of the first transcontinental railroad, and took ...

, to pursue the idea of creating a rail line that would connect America's east and west. In 1861, these four businessmen (sometimes referred to as The Big Four) pooled their resources and business acumen, and formed the Central Pacific Railroad

The Central Pacific Railroad (CPRR) was a rail company chartered by U.S. Congress in 1862 to build a railroad eastwards from Sacramento, California, to complete the western part of the " First transcontinental railroad" in North America. Incor ...

company to create the western link of America's First transcontinental railroad

North America's first transcontinental railroad (known originally as the "Pacific Railroad" and later as the " Overland Route") was a continuous railroad line constructed between 1863 and 1869 that connected the existing eastern U.S. rail netwo ...

. Of the four, Huntington had a reputation for being the most ruthless in pursuing the railroad's business; he ousted his partner, Stanford.

Huntington negotiated in Washington, DC, with Grenville Dodge

Grenville Mellen Dodge (April 12, 1831 – January 3, 1916) was a Union Army officer on the frontier and a pioneering figure in military intelligence during the Civil War, who served as Ulysses S. Grant's intelligence chief in the Western The ...

, who was supervising railroad construction from the East, over where the railroads should meet. They completed their agreement in April 1869, deciding to meet at Promontory Summit, Utah

Promontory is an area of high ground in Box Elder County, Utah, United States, 32 mi (51 km) west of Brigham City and 66 mi (106 km) northwest of Salt Lake City. Rising to an elevation of 4,902 feet (1,494 m) above s ...

. On May 10, 1869, at Promontory, the tracks of the Central Pacific Railroad joined with the tracks of the Union Pacific Railroad

The Union Pacific Railroad , legally Union Pacific Railroad Company and often called simply Union Pacific, is a freight-hauling railroad that operates 8,300 locomotives over routes in 23 U.S. states west of Chicago and New Orleans. Union Paci ...

, and America had a transcontinental railroad. The joining was celebrated by the driving of the golden spike

The golden spike (also known as The Last Spike) is the ceremonial 17.6- karat gold final spike driven by Leland Stanford to join the rails of the first transcontinental railroad across the United States connecting the Central Pacific Railroad ...

, provided for the occasion as a gift to the CPRR by San Francisco banker and merchant David Hewes.

Southern Pacific Railroad

Southern Pacific Railroad

The Southern Pacific (or Espee from the railroad initials- SP) was an American Class I railroad network that existed from 1865 to 1996 and operated largely in the Western United States. The system was operated by various companies under the ...

with the Big Four principals of the Central Pacific Railroad. The railroad's first locomotive '' C. P. Huntington'', (transferred from the CPR), was named in his honor. With rail lines from to the Southwest and into California, Southern Pacific expanded to more than 9,000 miles of track. It also controlled 5,000 miles of connecting steamship lines. Using the Southern Pacific Railroad, Huntington endeavored to prevent the port at San Pedro from becoming the main Port of Los Angeles

The Port of Los Angeles is a seaport managed by the Los Angeles Harbor Department, a unit of the City of Los Angeles. It occupies of land and water with of waterfront and adjoins the separate Port of Long Beach. Promoted as "America's Port", ...

in the Free Harbor Fight.

Chesapeake and Ohio Railway, new cities and a shipyard

Following theAmerican Civil War

The American Civil War (April 12, 1861 – May 26, 1865; also known by Names of the American Civil War, other names) was a civil war in the United States. It was fought between the Union (American Civil War), Union ("the North") and t ...

, efforts were renewed in Virginia to complete a canal

Canals or artificial waterways are waterways or engineered channels built for drainage management (e.g. flood control and irrigation) or for conveyancing water transport vehicles (e.g. water taxi). They carry free, calm surface f ...

or railroad link between Richmond and the Ohio River

The Ohio River is a long river in the United States. It is located at the boundary of the Midwestern and Southern United States, flowing southwesterly from western Pennsylvania to its mouth on the Mississippi River at the southern tip of ...

Valley. Before the war, the Virginia Board of Public Works

The Virginia Board of Public Works was a governmental agency which oversaw and helped finance the development of Virginia's transportation-related internal improvements during the 19th century. In that era, it was customary to invest public funds ...

and the Virginia Central Railroad

The Virginia Central Railroad was an early railroad in the U.S. state of Virginia that operated between 1850 and 1868 from Richmond westward for to Covington. Chartered in 1836 as the Louisa Railroad by the Virginia General Assembly, the railr ...

had provided financial assistance to construct a state-owned link through the Blue Ridge Mountains

The Blue Ridge Mountains are a physiographic province of the larger Appalachian Mountains range. The mountain range is located in the Eastern United States, and extends 550 miles southwest from southern Pennsylvania through Maryland, West Virg ...

. It had been completed along this route as far as the upper reaches of the Shenandoah Valley

The Shenandoah Valley () is a geographic valley and cultural region of western Virginia and the Eastern Panhandle of West Virginia. The valley is bounded to the east by the Blue Ridge Mountains, to the west by the eastern front of the Ridg ...

when the War broke out.

Officials of the Virginia Central, led by company president Williams Carter Wickham

Williams Carter Wickham (September 21, 1820 – July 23, 1888) was a Virginia lawyer and politician. A plantation owner who served in both houses of the Virginia General Assembly, Wickham also became a delegate to the Virginia Secession Convent ...

, realized that they would have to get capital from outside the economically devastated South in order to rebuild. They tried to attract British

British may refer to:

Peoples, culture, and language

* British people, nationals or natives of the United Kingdom, British Overseas Territories, and Crown Dependencies.

** Britishness, the British identity and common culture

* British English, ...

interests, without success. Finally, Major Wickham succeeded in getting Collis Huntington interested helping to complete the line.

Beginning in 1871, Huntington oversaw completion of the newly formed Chesapeake and Ohio Railway

The Chesapeake and Ohio Railway was a Class I railroad formed in 1869 in Virginia from several smaller Virginia railroads begun in the 19th century. Led by industrialist Collis P. Huntington, it reached from Virginia's capital city of Richmond t ...

(C&O) from Richmond

Richmond most often refers to:

* Richmond, Virginia, the capital of Virginia, United States

* Richmond, London, a part of London

* Richmond, North Yorkshire, a town in England

* Richmond, British Columbia, a city in Canada

* Richmond, Californi ...

across Virginia

Virginia, officially the Commonwealth of Virginia, is a state in the Mid-Atlantic and Southeastern regions of the United States, between the Atlantic Coast and the Appalachian Mountains. The geography and climate of the Commonwealth are ...

and West Virginia

West Virginia is a state in the Appalachian, Mid-Atlantic and Southeastern regions of the United States.The Census Bureau and the Association of American Geographers classify West Virginia as part of the Southern United States while the ...

to reach the Ohio River

The Ohio River is a long river in the United States. It is located at the boundary of the Midwestern and Southern United States, flowing southwesterly from western Pennsylvania to its mouth on the Mississippi River at the southern tip of ...

. There, with his brother-in-law D.W. Emmons, he established the planned city

A planned community, planned city, planned town, or planned settlement is any community that was carefully planned from its inception and is typically constructed on previously undeveloped land. This contrasts with settlements that evolve ...

of Huntington, West Virginia

Huntington is a city in Cabell and Wayne counties in the U.S. state of West Virginia. It is the county seat of Cabell County, and the largest city in the Huntington–Ashland metropolitan area, sometimes referred to as the Tri-State Area. A ...

. He became active in developing the emerging southern West Virginia bituminous coal

Bituminous coal, or black coal, is a type of coal containing a tar-like substance called bitumen or asphalt. Its coloration can be black or sometimes dark brown; often there are well-defined bands of bright and dull material within the seams. It ...

business for the C&O.

Beginning in 1865, Huntington had been acquiring land in Virginia's eastern Tidewater region

Tidewater refers to the north Atlantic coastal plain region of the United States of America.

Definition

Culturally, the Tidewater region usually includes the low-lying plains of southeast Virginia, northeastern North Carolina, southern Mary ...

, an area not served by extant railroads. In 1880, he formed the Old Dominion Land Company and turned these holdings over to it.

Beginning in December 1880, he led the building of the C&O's

Beginning in December 1880, he led the building of the C&O's Peninsula Subdivision

The Peninsula Extension which created the Peninsula Subdivision of the Chesapeake and Ohio Railway (C&O) was the new railroad line on the Virginia Peninsula from Richmond to southeastern Warwick County. Its principal purpose was to provide an i ...

, which extended from the Church Hill Tunnel in Richmond east down the Virginia Peninsula

The Virginia Peninsula is a peninsula in southeast Virginia, USA, bounded by the York River, James River, Hampton Roads and Chesapeake Bay. It is sometimes known as the ''Lower Peninsula'' to distinguish it from two other peninsulas to the n ...

through Williamsburg to the southeastern end of the Peninsula on the harbor of Hampton Roads

Hampton Roads is the name of both a body of water in the United States that serves as a wide channel for the James, Nansemond and Elizabeth rivers between Old Point Comfort and Sewell's Point where the Chesapeake Bay flows into the Atlantic ...

in Warwick County, Virginia

Warwick County was a county in Southeast Virginia that was created from Warwick River Shire, one of eight created in the Virginia Colony in 1634. It became the City of Newport News on July 16, 1952. Located on the Virginia Peninsula on the no ...

. Through the new railroad and his land company, coal piers were established at Newport News Point.

It may have taken more than 50 years after Virginia's first railroad operated for the lower Peninsula to get a railroad, but once work started, it progressed quickly. In a manner he had previously deployed, notably with the transcontinental railroad, and the line to the Ohio River, work began at both Newport News and Richmond. The crews at each end worked toward each other. The crews met and completed the line 1.25 miles west of Williamsburg on October 16, 1881, although temporary tracks had been installed in some areas to speed completion.

Huntington and his associates had promised they would provide rail service to Yorktown where the United States was celebrating the centennial of the surrender of the British troops under Lord Cornwallis

Charles Cornwallis, 1st Marquess Cornwallis, (31 December 1738 – 5 October 1805), styled Viscount Brome between 1753 and 1762 and known as the Earl Cornwallis between 1762 and 1792, was a British Army general and official. In the United S ...

at Yorktown in 1781, an event considered most symbolic of the end of American Revolutionary War

The American Revolutionary War (April 19, 1775 – September 3, 1783), also known as the Revolutionary War or American War of Independence, was a major war of the American Revolution. Widely considered as the war that secured the independence of t ...

. Three days after the last spike ceremony, on October 19, the first passenger train from Newport News took local residents and national officials to the Cornwallis Surrender Centennial Celebration at Yorktown on temporary tracks that were laid from the main line at the new Lee Hall Depot to Yorktown.

No sooner had the tracks to the new coal pier at Newport News been completed in late 1881 than the same construction crews were put to work on what would later be called the Peninsula Subdivision's Hampton Branch. It ran easterly about 10 miles into Elizabeth City County toward Hampton

Hampton may refer to:

Places Australia

*Hampton bioregion, an IBRA biogeographic region in Western Australia

*Hampton, New South Wales

*Hampton, Queensland, a town in the Toowoomba Region

* Hampton, Victoria

Canada

* Hampton, New Brunswick

*Ha ...

and Old Point Comfort

Old Point Comfort is a point of land located in the independent city of Hampton, Virginia. Previously known as Point Comfort, it lies at the extreme tip of the Virginia Peninsula at the mouth of Hampton Roads in the United States. It was renamed ...

, where the U.S. Army

The United States Army (USA) is the land service branch of the United States Armed Forces. It is one of the eight U.S. uniformed services, and is designated as the Army of the United States in the U.S. Constitution.Article II, section 2, cl ...

base at Fort Monroe

Fort Monroe, managed by partnership between the Fort Monroe Authority for the Commonwealth of Virginia, the National Park Service as the Fort Monroe National Monument, and the City of Hampton, is a former military installation in Hampton, Virgi ...

guarded the entrance to the harbor of Hampton Roads from the Chesapeake Bay (and the Atlantic Ocean). The tracks were completed about 9 miles to the town which became Phoebus

Apollo, grc, Ἀπόλλωνος, Apóllōnos, label=genitive , ; , grc-dor, Ἀπέλλων, Apéllōn, ; grc, Ἀπείλων, Apeílōn, label=Arcadocypriot Greek, ; grc-aeo, Ἄπλουν, Áploun, la, Apollō, la, Apollinis, label= ...

in December 1882, named in honor of its leading citizen, Harrison Phoebus Harrison Phoebus (born Levin James Harrison Phoebus, November 1, 1840 – February 25, 1886) was an American 19th century entrepreneur and hotelier who became the leading citizen and namesake of the town of Phoebus in Elizabeth City County, near ...

. The new branch line served both the older Hygeia Hotel

Hygieia is a goddess from Greek, as well as Roman, mythology (also referred to as: Hygiea or Hygeia; ; grc, Ὑγιεία or , la, Hygēa or ). Hygieia is a goddess of health ( el, ὑγίεια – ''hugieia''), cleanliness and hygiene. Her ...

and the new Hotel Chamberlain, popular destinations for civilians. During the first half of the 20th century, excursion trains were operated to reach nearby Buckroe Beach

Buckroe Beach is a neighborhood in the independent city of Hampton, Virginia. It lies just north of Fort Monroe on the Chesapeake Bay. One of the oldest recreational areas in the state, it was long located in Elizabeth City County near the dow ...

, where an amusement park

An amusement park is a park that features various attractions, such as rides and games, as well as other events for entertainment purposes. A theme park is a type of amusement park that bases its structures and attractions around a central ...

was among the attractions for both church groups and vacationers.

At the formerly sleepy little farming community of Newport News Point, Huntington began other, building the landmark Hotel Warwick and founding the Newport News Shipbuilding and Drydock Company. This became the largest privately owned shipyard in the United States.

Huntington is largely credited with vision and the combination of developments which created and built a vibrant and progressive community. The 15 years of rapid growth and development led to the incorporation of Newport News, Virginia

Newport News () is an independent city in the U.S. state of Virginia. At the 2020 census, the population was 186,247. Located in the Hampton Roads region, it is the 5th most populous city in Virginia and 140th most populous city in the U ...

as a new independent city

An independent city or independent town is a city or town that does not form part of another general-purpose local government entity (such as a province).

Historical precursors

In the Holy Roman Empire, and to a degree in its successor states ...

in 1896. It is one of only two independent cities in Virginia that were so formed without developing first as an incorporated town

An incorporated town is a town that is a municipal corporation.

Canada

Incorporated towns are a form of local government in Canada, which is a responsibility of provincial rather than federal government.

United Kingdom

United States

An in ...

.

Near the tracks of the C&O's Hampton Branch was a normal school

A normal school or normal college is an institution created to train teachers by educating them in the norms of pedagogy and curriculum. In the 19th century in the United States, instruction in normal schools was at the high school level, turni ...

, dedicated in its earliest years to training teachers to educate the South's many African-American

African Americans (also referred to as Black Americans and Afro-Americans) are an ethnic group consisting of Americans with partial or total ancestry from sub-Saharan Africa. The term "African American" generally denotes descendants of ensl ...

freedmen

A freedman or freedwoman is a formerly enslaved person who has been released from slavery, usually by legal means. Historically, enslaved people were freed by manumission (granted freedom by their captor-owners), emancipation (granted freedom ...

after the Civil War and abolition of slavery. Both adults and children were eager to learn. Most southern blacks had been denied opportunities for education literacy before the Civil War. The school which developed to become modern-day Hampton University

Hampton University is a private, historically black, research university in Hampton, Virginia. Founded in 1868 as Hampton Agricultural and Industrial School, it was established by Black and White leaders of the American Missionary Association a ...

was first led by former Union General Samuel Chapman Armstrong

Samuel Chapman Armstrong (January 30, 1839 – May 11, 1893) was an American soldier and general during the American Civil War who later became an educator, particularly of non-whites. The son of missionaries in Hawaii, he rose through the Union ...

. Perhaps the best known of General Armstrong's students was a youth named Booker T. Washington

Booker Taliaferro Washington (April 5, 1856November 14, 1915) was an American educator, author, orator, and adviser to several presidents of the United States. Between 1890 and 1915, Washington was the dominant leader in the African-American c ...

. He later was hired as principal of Tuskegee Institute in Alabama, another historically black college

Historically black colleges and universities (HBCUs) are institutions of higher education in the United States that were established before the Civil Rights Act of 1964 with the intention of primarily serving the African-American community. Mo ...

, and developed it into Tuskegee University

Tuskegee University (Tuskegee or TU), formerly known as the Tuskegee Institute, is a private, historically black land-grant university in Tuskegee, Alabama. It was founded on Independence Day in 1881 by the state legislature.

The campus was de ...

. When Sam Armstrong suffered a debilitating paralysis in 1892 while in New York, he returned to Hampton in a private railroad car

A private railroad car, private railway coach, private car, or private varnish is a railroad passenger car either originally built or later converted for service as a business car for private individuals. A private car could be added to the make- ...

provided by Huntington, with whom he had collaborated on black education projects.

In the lower Peninsula, Collis and other Huntington family members and their Old Dominion Land Company were involved in many aspects of life and business. They founded schools, museums, libraries and parks among their many contributions. In Williamsburg, Collis' Old Dominion Land Company owned the historic site of the 18th-century capital buildings. This was transferred to the women who were the earliest promoters of what became Preservation Virginia (formerly known as the Association for the Preservation of Virginia Antiquities). This site was later a key piece of the Abby and John D. Rockefeller Jr.

John Davison Rockefeller Jr. (January 29, 1874 – May 11, 1960) was an American financier and philanthropist, and the only son of Standard Oil co-founder John D. Rockefeller.

He was involved in the development of the vast office complex in M ...

's massive restoration of the former colonial capital city. They developed Colonial Williamsburg

Colonial Williamsburg is a living-history museum and private foundation presenting a part of the historic district in the city of Williamsburg, Virginia, United States. The Colonial Williamsburg Foundation has 7300 employees at this location ...

, one of the world's major tourist attractions.

Huntington did not neglect his namesake city at the other end of the C&O. In order to supply

Huntington did not neglect his namesake city at the other end of the C&O. In order to supply freight car

A railroad car, railcar (American and Canadian English), railway wagon, railway carriage, railway truck, railwagon, railcarriage or railtruck (British English and UIC), also called a train car, train wagon, train carriage or train truck, is a ...

s to the C&O, and by extension to the Southern Pacific and Central Pacific Railroads as well, Huntington was a major financier behind Ensign Manufacturing Company

Ensign Manufacturing Company, founded as Ensign Car Works in 1872, was a railroad car manufacturing company based in Huntington, West Virginia. In the 1880s and 1890s Ensign's production of wood freight cars made the company one of the three larg ...

. He based the company in Huntington, West Virginia, directly connecting to the C&O; Ensign was incorporated on November 1, 1872.

After Huntington's death in 1900, his nephew, Henry E. Huntington

Henry Edwards Huntington (February 27, 1850 – May 23, 1927) was an American railroad magnate and collector of art and rare books. Huntington settled in Los Angeles, where he owned the Pacific Electric Railway as well as substantial real estate ...

, assumed leadership of many of his industrial endeavors. The younger man quickly sold off all of the Southern Pacific holdings. He and other family members also continued and expanded many of the senior Huntington's cultural and philanthropic projects, in addition to developing their own.

Death

Huntington died at his "camp," Pine Knot, in theAdirondack Mountains

The Adirondack Mountains (; a-də-RÄN-dak) form a massif in northeastern New York with boundaries that correspond roughly to those of Adirondack Park. They cover about 5,000 square miles (13,000 km2). The mountains form a roughly circular ...

on August 13, 1900. He is interred in a Classical-style mausoleum at the Woodlawn Cemetery, Bronx

Woodlawn Cemetery is one of the largest cemeteries in New York City and a designated National Historic Landmark. Located south of Woodlawn Heights, Bronx, New York City, it has the character of a rural cemetery. Woodlawn Cemetery opened during ...

, New York.

Politics

In addition to his railroad building, Huntington is best known for his political activity in Washington, D.C. and California. At this stage he was based mostly in New York, and visited California about once a year. Stanford remained president, first of the Central Pacific and then of the Southern Pacific Company, until 1890. Huntington was agent and attorney for the Southern Pacific Railroad, vice-president and general agent for the Central Pacific Railroad, first vice-president of the Southern Pacific Company, and a director of the two lines. His main duties were selling company stocks and bonds and acting as the chief lobbyist in Washington, where his two main challenges were to block federal support for a proposed rival transcontinental route, theTexas and Pacific Railway

The Texas and Pacific Railway Company (known as the T&P) was created by federal charter in 1871 with the purpose of building a southern transcontinental railroad between Marshall, Texas, and San Diego, California.

History

Under the influence of ...

(in which he succeeded) and to postpone payment of the $28 million in cash loans the government had made to the Central Pacific (in which he did not). He first asked to delay payments for fifty years, then for a hundred years. His proposal to cancel the loans created a firestorm of opposition in California, covered colorfully in the newspapers by Ambrose Bierce

Ambrose Gwinnett Bierce (June 24, 1842 – ) was an American short story writer, journalist, poet, and American Civil War veteran. His book ''The Devil's Dictionary'' was named as one of "The 100 Greatest Masterpieces of American Literature" by t ...

; when it was defeated in Congress in 1897, the governor of California celebrated by declaring a public holiday. Huntington lost the battle in Congress in 1899 and the Southern Pacific finally paid off the loans in 1909.

Huntington described his activities in a series of private letters to David D. Colton, a senior financial official of his railroads. After Colton's death, litigation opened his files in 1883 and Huntington's letters proved a huge embarrassment, with their detailed descriptions of lobbying, payoffs, and bribes to government officials. They showed Huntington to be an active, profane, and cynical promoter of his companies and display his eagerness to use money to bribe congressmen. The letters did not demonstrate that any cash actually changed hands with any official, but they revealed the tenor of Huntington's morals.

His biographer says:

Family relationships

Collis Huntington was the son of William and Elizabeth (Vincent) Huntington; born October 22, 1821, in Harwinton, Connecticut. His siblings were:

# Mary Huntington, born 17 February 1810; married 2 June 1840, Daniel Sammis of Warsaw, New York.

# Solon Huntington, born 13 January 1812.

# Rhoda Huntington, born 13 October 1814; married 10 May 1834, Riley Dunbar of Wolcottville.

# Phebe/Phoebe Huntington, born 17 September 1817; married 4 October 1840, Henry Pardee of

Collis Huntington was the son of William and Elizabeth (Vincent) Huntington; born October 22, 1821, in Harwinton, Connecticut. His siblings were:

# Mary Huntington, born 17 February 1810; married 2 June 1840, Daniel Sammis of Warsaw, New York.

# Solon Huntington, born 13 January 1812.

# Rhoda Huntington, born 13 October 1814; married 10 May 1834, Riley Dunbar of Wolcottville.

# Phebe/Phoebe Huntington, born 17 September 1817; married 4 October 1840, Henry Pardee of Oneonta, New York

Oneonta ( ) is a Administrative divisions of New York#City, city in southern Otsego County, New York, Otsego County, New York (state), New York, United States. It is one of the northernmost cities of the Appalachian Region. According to the 2020 ...

.

# Elizabeth Huntington, born 19 December 1819; married 5 April 1842, Hiram Yaker of Kortright, New York

Kortright is a town in Delaware County, New York, United States. The population was 1,675 at the 2010 census. The town is in the northern part of the county.

History

Kortright was formed from the town of Harpersfield in 1793.

The West Kortri ...

.

# Collis Potter Huntington, born October 22, 1821.

# Joseph Huntington, born 23 March 1823; d. 23 February 1849; never married

# Susan L. Huntington, born 28 August 1826; married 16 November 1849, William Porter, M.D., of New Haven, Connecticut

New Haven is a city in the U.S. state of Connecticut. It is located on New Haven Harbor on the northern shore of Long Island Sound in New Haven County, Connecticut and is part of the New York City metropolitan area. With a population of 134 ...

# Ellen Maria Huntington, born 12 August 1835; married Isaac E. Gates of Orange, New Jersey

The City of Orange is a township in Essex County, in the U.S. state of New Jersey. As of the 2010 U.S. census, the township's population was 30,134, reflecting a decline of 2,734 (−8.3%) from the 32,868 counted in 2000.

Orange was original ...

. She was known as a poet and hymn writer.

Collis Huntington married Elizabeth Stillman Stoddard, of Cornwall, Connecticut

Cornwall is a town in Litchfield County, Connecticut, United States. The population was 1,567 at the 2020 census.

History

The town of Cornwall, Connecticut, is named after the county of Cornwall, England. The town was incorporated in 1740, near ...

, on September 16, 1844. She lived until 1883. They adopted her niece, Clara Elizabeth Prentice, born in Sacramento in 1860. Clara Elizabeth Prentice-Huntington (1860–1928), as she was called, married Prince Franz Edmund Joseph Gabriel Vitus von Hatzfeldt-Wildenburg, a.k.a., Francis Hatzfeldt of the House of Hatzfeld

The House of Hatzfeld, also spelled Hatzfeldt, is the name of an ancient and influential German noble family, whose members played important roles in the history of the Holy Roman Empire, Prussia and Austria.

History

They belonged to high nobil ...

, Germany

Germany,, officially the Federal Republic of Germany, is a country in Central Europe. It is the second most populous country in Europe after Russia, and the most populous member state of the European Union. Germany is situated betwee ...

, on October 28, 1889. They made their home at Draycot House, Draycot Cerne

Draycot Cerne (Draycott) is a small village and former civil parish in Wiltshire, England, about north of Chippenham.

History

The parish was referred to as ''Draicote'' (Medieval Latin) in the ancient Domesday hundred of Startley when Geoff ...

, Wiltshire

Wiltshire (; abbreviated Wilts) is a historic and ceremonial county in South West England with an area of . It is landlocked and borders the counties of Dorset to the southwest, Somerset to the west, Hampshire to the southeast, Gloucestershire ...

, England

England is a country that is part of the United Kingdom. It shares land borders with Wales to its west and Scotland to its north. The Irish Sea lies northwest and the Celtic Sea to the southwest. It is separated from continental Europe ...

.

Huntington remarried on July 12, 1884, to Arabella D. Worsham. She brought to the marriage her son Archer Milton Worsham, from her first marriage, whom Huntington adopted that year. At fourteen, he became known as Archer Milton Huntington. There were rumors that Huntington had a longer relationship with Arabella and that he was the biological father of her son. Huntington died at his Camp Pine Knot

Camp Pine Knot, also known as Huntington Memorial Camp, on Raquette Lake in the Adirondack Mountains of New York State, was built by William West Durant. Begun in 1877, it was the first of the "Adirondack Great Camps" and epitomizes the "Great Cam ...

, in the Adirondacks, August 13, 1900.

Archer M. Huntington became a well-known Hispanist and founded The Hispanic Society of America

The Hispanic Society of America operates a museum and reference library for the study of the arts and cultures of Spain and Portugal and their former colonies in Latin America, the Spanish East Indies, and Portuguese India. Despite the name, it ...

, a museum and rare-books library dedicated to Spanish and Portuguese history, art, and culture, based in upper Manhattan, in New York City. Archer and his second wife, sculptor Anna Hyatt Huntington

Anna Vaughn Hyatt Huntington (March 10, 1876 – October 4, 1973) was an American sculptor who was among New York City's most prominent sculptors in the early 20th century. At a time when very few women were successful artists, she had a thrivi ...

, founded Brookgreen Gardens

Brookgreen Gardens is a sculpture garden and wildlife preserve, located just south of Murrells Inlet, in South Carolina. The property includes several themed gardens featuring American figurative sculptures, the Lowcountry Zoo, and trails throu ...

sculpture and botanical gardens near Murrells Inlet, South Carolina

Murrells Inlet is an unincorporated area and census-designated place in Georgetown County, South Carolina, United States. The population was 7,547 at the 2010 census. It is about 13 miles south of Myrtle Beach, South Carolina and 21 miles north ...

. He also founded the Mariners' Museum

The Mariners' Museum and Park is located in Newport News, Virginia, United States. Designated as America’s ''National Maritime Museum'' by Congress, it is one of the largest maritime museums in North America. The Mariners' Museum Library, cont ...

in Newport News, one of the largest of its kind in the world.

Huntington's nephew, Henry E. Huntington

Henry Edwards Huntington (February 27, 1850 – May 23, 1927) was an American railroad magnate and collector of art and rare books. Huntington settled in Los Angeles, where he owned the Pacific Electric Railway as well as substantial real estate ...

(1850-1927), was also a railway magnate and founder of the Huntington Library, Art Collections and Botanical Gardens in San Marino, California. He was active in Los Angeles, California

Los Angeles ( ; es, Los Ángeles, link=no , ), often referred to by its initials L.A., is the List of municipalities in California, largest city in the U.S. state, state of California and the List of United States cities by population, sec ...

, where he was the main force behind development of the Pacific Electric

The Pacific Electric Railway Company, nicknamed the Red Cars, was a privately owned Public transport, mass transit system in Southern California consisting of electrically powered streetcars, interurban cars, and buses and was the largest electr ...

system.

He was also related to Clarence Huntington, a president of the Virginian Railway

The Virginian Railway was a Class I railroad located in Virginia and West Virginia in the United States. The VGN was created to transport high quality "smokeless" bituminous coal from southern West Virginia to port at Hampton Roads.

Histor ...

who succeeded Urban H. Broughton. He was the son-in-law of the VGN's founder, industrialist Henry Huttleston Rogers.

Charity

He acquired a substantial collection of art, and was generally recognized as one of the country's foremost art collectors. He left most of his collection, valued at $3 million, to theMetropolitan Museum of Art

The Metropolitan Museum of Art of New York City, colloquially "the Met", is the largest art museum in the Americas. Its permanent collection contains over two million works, divided among 17 curatorial departments. The main building at 1000 ...

in New York

New York most commonly refers to:

* New York City, the most populous city in the United States, located in the state of New York

* New York (state), a state in the northeastern United States

New York may also refer to:

Film and television

* '' ...

, to pass into the museum's hands after the death of his stepson, Archer. His last will directed that if his stepson should die childless (which he did), Huntington's Fifth Avenue mansion or the proceeds from the sale of the property would go to Yale University. He also made specific bequests totaling $125,000 to Hampton University

Hampton University is a private, historically black, research university in Hampton, Virginia. Founded in 1868 as Hampton Agricultural and Industrial School, it was established by Black and White leaders of the American Missionary Association a ...

(then Hampton Institute) and to the Chapin Home for the Aged.

Namesake locations

Buildings

* Collis P. Huntington High School,Newport News, Virginia

Newport News () is an independent city in the U.S. state of Virginia. At the 2020 census, the population was 186,247. Located in the Hampton Roads region, it is the 5th most populous city in Virginia and 140th most populous city in the U ...

* Huntington Hotel – San Francisco, California

* Huntington Free Library and Reading Room

The Huntington Free Library is a privately endowed library near Westchester Square in the New York City borough of the Bronx, which is open to the public. It has a non-circulating book collection.

The Reading Room has mostly early-20th century ...

– Bronx, New York

* Collis P. Huntington Academic Building; Tuskegee University

Tuskegee University (Tuskegee or TU), formerly known as the Tuskegee Institute, is a private, historically black land-grant university in Tuskegee, Alabama. It was founded on Independence Day in 1881 by the state legislature.

The campus was de ...

, Alabama (Destroyed in a fire)

* Huntington Dorm; Tuskegee University, Alabama

* Collis P. Huntington House, New York City

* C. P. Huntington Primary School in Sacramento, California

)

, image_map = Sacramento County California Incorporated and Unincorporated areas Sacramento Highlighted.svg

, mapsize = 250x200px

, map_caption = Location within Sacramento C ...

* Collis Potter and Howard Edwards Huntington Memorial Hospital in Pasadena, California

Pasadena ( ) is a city in Los Angeles County, California, northeast of downtown Los Angeles. It is the most populous city and the primary cultural center of the San Gabriel Valley. Old Pasadena is the city's original commercial district.

...

* Huntington Hall – U.S. Navy enlisted housing and USO 3100 Huntington Avenue, Newport News, Virginia

* Collis P. Huntington Memorial Library – Hampton University

Hampton University is a private, historically black, research university in Hampton, Virginia. Founded in 1868 as Hampton Agricultural and Industrial School, it was established by Black and White leaders of the American Missionary Association a ...

Now, the Hampton University Museum, Hampton, Virginia

Hampton () is an independent city (United States), independent city in the Commonwealth (U.S. state), Commonwealth of Virginia in the United States. As of the 2020 United States Census, 2020 census, the population was 137,148. It is the List ...

Inhabited places

*Huntington, West Virginia

Huntington is a city in Cabell and Wayne counties in the U.S. state of West Virginia. It is the county seat of Cabell County, and the largest city in the Huntington–Ashland metropolitan area, sometimes referred to as the Tri-State Area. A ...

**Collis and Huntington Avenues in Huntington, West Virginia

* Huntington, Texas

Huntington is a city in Angelina County, Texas, United States. The population was 2,025 at the 2020 census. The site is named for Collis Potter Huntington, the chairman of the board of the Southern Pacific Railroad when the town was formed and on ...

in Angelina County, Texas

Angelina County ( ) is a county located in the U.S. state of Texas. It is in East Texas and its county seat is Lufkin.

As of the 2020 census, the population was 86,395. The Lufkin, TX Micropolitan Statistical Area includes all of Angelina Co ...

* Huntingdon, Abbotsford, neighborhood in Abbotsford, British Columbia

Abbotsford is a city located in British Columbia, adjacent to the Canada–United States border, Greater Vancouver and the Fraser River. With an estimated population of 153,524 people it is the largest municipality in the province outside metro ...

* North End Huntington Heights Historic District, residential district in Newport News, Virginia

Newport News () is an independent city in the U.S. state of Virginia. At the 2020 census, the population was 186,247. Located in the Hampton Roads region, it is the 5th most populous city in Virginia and 140th most populous city in the U ...

Other

*Camp Pine Knot

Camp Pine Knot, also known as Huntington Memorial Camp, on Raquette Lake in the Adirondack Mountains of New York State, was built by William West Durant. Begun in 1877, it was the first of the "Adirondack Great Camps" and epitomizes the "Great Cam ...

, also known as Camp Huntington, on Raquette Lake

Raquette Lake is the source of the Raquette River in the Adirondack Mountains of New York State. It is near the community of Raquette Lake, New York. The lake has of shoreline with pines and mountains bordering the lake. It is located in the ...

, New York, which is now owned by the State University of New York at Cortland

State may refer to:

Arts, entertainment, and media Literature

* ''State Magazine'', a monthly magazine published by the U.S. Department of State

* ''The State'' (newspaper), a daily newspaper in Columbia, South Carolina, United States

* ''Our S ...

* Collis P. Huntington State Park, Redding and Bethel, Connecticut

Bethel () is a town in Fairfield County, Connecticut, United States. Its population was 11,988 in 2022 according to World Population Review. The town includes the Bethel Census Designated Place.

Interstate 84 passes through Bethel, and it h ...

* Huntington Park

Huntington Park is a city in the Gateway Cities district of southeastern Los Angeles County, California.

As of the 2010 census, the city had a total population of 58,114, of whom 97% are Hispanic/Latino and about half were born outside th ...

, and Huntington Avenue, Newport News, Virginia

* Huntington Park

Huntington Park is a city in the Gateway Cities district of southeastern Los Angeles County, California.

As of the 2010 census, the city had a total population of 58,114, of whom 97% are Hispanic/Latino and about half were born outside th ...

, the site of his San Francisco home that was destroyed by the 1906 earthquake and fire

* Mount Huntington, a peak in Fresno County

Fresno County (), officially the County of Fresno, is a county located in the central portion of the U.S. state of California. As of the 2020 Census, the population was 1,008,654. The county seat is Fresno, the fifth-most populous city in Cali ...

, California

* Collis Place in Bronx County, New York, which is located several blocks from Huntington's riverside mansion.

* Tugboat Huntington – retired 1994, now a floating exhibit and classroom at the Palm Beach Maritime Museum, Palm Beach, Florida

Palm Beach is an incorporated town in Palm Beach County, Florida. Located on a barrier island in east-central Palm Beach County, the town is separated from several nearby cities including West Palm Beach and Lake Worth Beach by the Intrac ...

* Collis Avenue, a residential street that starts at Huntington Drive in the El Sereno district of the City of Los Angeles

Los Angeles ( ; es, Los Ángeles, link=no , ), often referred to by its initials L.A., is the largest city in the state of California and the second most populous city in the United States after New York City, as well as one of the world ...

and ends in the City of South Pasadena, California

South Pasadena is a city in Los Angeles County, California, United States. As of the 2010 census, it had a population of 25,619, up from 24,292 at the 2000 census. It is located in the West San Gabriel Valley. It is 3.42 square miles in area an ...

* Huntington Boulevard in Fresno, California

Fresno () is a major city in the San Joaquin Valley of California, United States. It is the county seat of Fresno County and the largest city in the greater Central Valley region. It covers about and had a population of 542,107 in 2020, maki ...

* C.P. Huntington

''C. P. Huntington'' is a 4-2-4T steam locomotive on static display at the California State Railroad Museum in Sacramento, California, USA. It is the first locomotive purchased by the Southern Pacific Railroad, carrying that railroad's number ...

, a 4-2-4T

Under the Whyte notation for the classification of steam locomotives, represents the wheel arrangement of four leading wheels on two axles, two powered driving wheels on one axle, and four trailing wheels on two axles. This type of locomotive is ...

steam locomotive currently owned by the California State Railroad Museum

The California State Railroad Museum is a museum in the state park system of California, United States, interpreting the role of the "iron horse" in connecting California to the rest of the nation. It is located in Old Sacramento State Histor ...

In popular culture

He was referred to in ''Black Beetles in Amber'' byAmbrose Bierce

Ambrose Gwinnett Bierce (June 24, 1842 – ) was an American short story writer, journalist, poet, and American Civil War veteran. His book ''The Devil's Dictionary'' was named as one of "The 100 Greatest Masterpieces of American Literature" by t ...

as "Happy Hunty". Huntington was also referenced in Carl Sandburg's poem, ''Southern Pacific''. In the AMC series ''Hell on Wheels

Hell on Wheels was the itinerant collection of flimsily assembled gambling houses, dance halls, saloons, and brothels that followed the army of Union Pacific railroad workers westward as they constructed the First transcontinental railroad in 186 ...

'' he is played by actor Tim Guinee

Timothy S. Guinee (born November 18, 1962) is an American stage, television, and feature-film actor. Primarily known for his roles as Tomin in the television series ''Stargate SG-1'' (1997–2007) and railroad entrepreneur Collis Huntington AMC ...

.

See also

* Huntington family *History of rail transportation in California

The establishment of America's transcontinental rail lines securely linked California to the rest of the country, and the far-reaching transportation systems that grew out of them during the century that followed contributed to the state's soci ...

Notes

References and further reading

* Note: the factual accuracy of this book has been widely criticized. See Stephen E. Ambrose#Criticism. * Carman, Harry J., and Charles H. Mueller. "The Contract and Finance Company and the Central Pacific Railroad." ''Mississippi Valley Historical Review'' (1927): 326–341in JSTOR

* Daggett, Stuart. "Huntington, Collis Potter," ''Dictionary of American biography '' (1932), vol. 5 * Deverell, William. ''Railroad Crossing: Californians and the Railroad, 1850–1910'' (1994

online

* Evans, Cerinda W. ''Collis Potter Huntington'' (2 vols., 1954), A major biograph

online volume 1

* Huddleston, Eugene L. "Huntington, Collis Potter"

* Lavender, David, ''The great persuader: the biography of Collis P. Huntington'', University Press of Colorado, 1998 reprint, first published 1970. * Lewis, Oscar. ''The Big Four: The story of Huntington, Stanford, Hopkins, and Crocker, and of the Building of the Central Pacific'' (1938) * Rayner, Richard, ''The Associates: Four Capitalists Who Created California'', Norton, 2007. * Williams, R. Hal. ''The Democratic Party and California Politics, 1880–1896'' (1973

online

"Corporations, Corruption, and the Modern Lobby: A Gilded Age Story of the West and the South in Washington, D.C."

''Southern Spaces'', video of lecture by Richard White, Stanford University, 16 April 2009. * * "Collis Potter Huntington" in

''Prominent and progressive Americans; an encyclopædia of contemporaneous biography''

Compiled by Mitchell Charles Harrison. Publisher: New York Tribune, 1902

External links

Newport News

Huntington Hotel

San Francisco

Ellen M.H. Gates, Who's Who Poet

{{DEFAULTSORT:Huntington, Collis Potter American railway entrepreneurs 19th-century American railroad executives Southern Pacific Railroad people Businesspeople from Connecticut Businesspeople from San Francisco 1821 births 1900 deaths People from Harwinton, Connecticut Huntington, West Virginia Nob Hill, San Francisco Burials at Woodlawn Cemetery (Bronx, New York) 19th-century American philanthropists Huntington family