Cirripede on:

[Wikipedia]

[Google]

[Amazon]

A barnacle is a type of

Barnacles are encrusters, attaching themselves temporarily to a hard substrate or a

Barnacles are encrusters, attaching themselves temporarily to a hard substrate or a

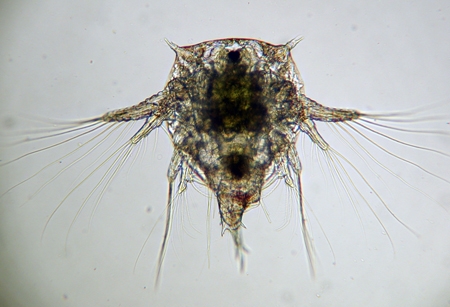

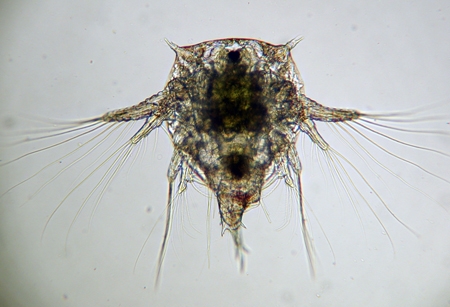

A fertilised egg hatches into a nauplius: a one-eyed larva comprising a head and a

A fertilised egg hatches into a nauplius: a one-eyed larva comprising a head and a

File:CornishBarnacles.JPG, Barnacles and limpets compete for space in the intertidal zone

File:Entenmuscheln.jpg, Goose barnacles, with their cirri extended for feeding

File:Chesaconcavus base detail.jpg, Underside of large ''Chesaconcavus'' sp. (

The anatomy of parasitic barnacles is generally simpler than that of their free-living relatives. They have no carapace or limbs, having only unsegmented sac-like bodies. Such barnacles feed by extending thread-like rhizomes of living cells into their hosts' bodies from their points of attachment.

Barnacles were originally classified by

Barnacles were originally classified by

File:Balanus improvisus on Mya arenaria shell.jpg, '' Balanus improvisus'', one of the many barnacle taxa described by

File:Siuslaw River-1.jpg, Barnacles attached to pilings along the

Barnacles

from the Marine Education Society of Australasia

Article on barnacles in Spain, and their collection and gastronomy. * * * * {{Authority control Parasitic crustaceans Maxillopoda Articles containing video clips Extant Cambrian first appearances

arthropod

Arthropods (, (gen. ποδός)) are invertebrate animals with an exoskeleton, a segmented body, and paired jointed appendages. Arthropods form the phylum Arthropoda. They are distinguished by their jointed limbs and cuticle made of chiti ...

constituting the subclass Cirripedia in the subphylum Crustacea, and is hence related to crabs and lobsters. Barnacles are exclusively marine, and tend to live in shallow and tidal waters, typically in erosive settings. They are sessile

Sessility, or sessile, may refer to:

* Sessility (motility), organisms which are not able to move about

* Sessility (botany), flowers or leaves that grow directly from the stem or peduncle of a plant

* Sessility (medicine), tumors and polyps that ...

(nonmobile) and most are suspension feeders, but those in infraclass

In biological classification, class ( la, classis) is a taxonomic rank, as well as a taxonomic unit, a taxon, in that rank. It is a group of related taxonomic orders. Other well-known ranks in descending order of size are life, domain, kingdo ...

Rhizocephala

Rhizocephala are derived barnacles that parasitise mostly decapod crustaceans, but can also infest Peracarida, mantis shrimps and thoracican barnacles, and are found from the deep ocean to freshwater. Together with their sister groups Thoracic ...

are highly specialized parasites on crustaceans. They have four nekton

Nekton or necton (from the ) refers to the actively swimming aquatic organisms in a body of water. The term was proposed by German biologist Ernst Haeckel to differentiate between the active swimmers in a body of water, and the passive organisms t ...

ic (active swimming) larval stages. Around 1,000 barnacle species

In biology, a species is the basic unit of classification and a taxonomic rank of an organism, as well as a unit of biodiversity. A species is often defined as the largest group of organisms in which any two individuals of the appropriate s ...

are currently known. The name is Latin

Latin (, or , ) is a classical language belonging to the Italic branch of the Indo-European languages. Latin was originally a dialect spoken in the lower Tiber area (then known as Latium) around present-day Rome, but through the power of the ...

, meaning "curl-footed". The study of barnacles is called cirripedology.

Description

Barnacles are encrusters, attaching themselves temporarily to a hard substrate or a

Barnacles are encrusters, attaching themselves temporarily to a hard substrate or a symbiont

Symbiosis (from Greek , , "living together", from , , "together", and , bíōsis, "living") is any type of a close and long-term biological interaction between two different biological organisms, be it mutualistic, commensalistic, or parasi ...

such as a whale ( whale barnacles), a sea snake ('' Platylepas ophiophila''), or another crustacean, like a crab or a lobster (Rhizocephala

Rhizocephala are derived barnacles that parasitise mostly decapod crustaceans, but can also infest Peracarida, mantis shrimps and thoracican barnacles, and are found from the deep ocean to freshwater. Together with their sister groups Thoracic ...

). The most common among them, "acorn barnacles" ( Sessilia), are sessile

Sessility, or sessile, may refer to:

* Sessility (motility), organisms which are not able to move about

* Sessility (botany), flowers or leaves that grow directly from the stem or peduncle of a plant

* Sessility (medicine), tumors and polyps that ...

where they grow their shells directly onto the substrate. Pedunculate barnacles (goose barnacle

Goose barnacles, also called stalked barnacles or gooseneck barnacles, are filter-feeding crustaceans that live attached to hard surfaces of rocks and flotsam in the ocean intertidal zone. Goose barnacles formerly made up the taxonomic order P ...

s and others) attach themselves by means of a stalk.

Free-living barnacles are attached to the substratum by cement glands that form the base of the first pair of antennae; in effect, the animal is fixed upside down by means of its forehead. In some barnacles, the cement glands are fixed to a long, muscular stalk, but in most they are part of a flat membrane or calcified plate. These glands secrete a type of natural quick cement able to withstand a pulling strength of per square inch and an sticking strength of per square inch. A ring of plates surrounds the body, homologous with the carapace of other crustaceans. These consist of the rostrum

Rostrum may refer to:

* Any kind of a platform for a speaker:

**dais

**pulpit

* Rostrum (anatomy), a beak, or anatomical structure resembling a beak, as in the mouthparts of many sucking insects

* Rostrum (ship), a form of bow on naval ships

* Ros ...

, two lateral plates, two carinolaterals, and a carina. In sessile barnacles, the apex of the ring of plates is covered by an operculum, which may be recessed into the carapace. The plates are held together by various means, depending on species, in some cases being solidly fused.

Inside the carapace, the animal lies on its stomach, projecting its limbs downwards. Segmentation is usually indistinct, and the body is more or less evenly divided between the head and thorax

The thorax or chest is a part of the anatomy of humans, mammals, and other tetrapod animals located between the neck and the abdomen. In insects, crustaceans, and the extinct trilobites, the thorax is one of the three main divisions of the cre ...

, with little, if any, abdomen

The abdomen (colloquially called the belly, tummy, midriff, tucky or stomach) is the part of the body between the thorax (chest) and pelvis, in humans and in other vertebrates. The abdomen is the front part of the abdominal segment of the to ...

. Adult barnacles have few appendages on their heads, with only a single, vestigial pair of antennae, attached to the cement gland. The eight pairs of thoracic limbs are referred to as " cirri" which are feathery and very long, the cirri extend to filter food, such as plankton, from the water and move it towards the mouth.

Barnacles have no true heart

The heart is a muscular organ in most animals. This organ pumps blood through the blood vessels of the circulatory system. The pumped blood carries oxygen and nutrients to the body, while carrying metabolic waste such as carbon dioxide to t ...

, although a sinus close to the esophagus

The esophagus ( American English) or oesophagus (British English; both ), non-technically known also as the food pipe or gullet, is an organ in vertebrates through which food passes, aided by peristaltic contractions, from the pharynx to ...

performs a similar function, with blood being pumped through it by a series of muscles. The blood vascular system is minimal. Similarly, they have no gill

A gill () is a respiratory organ that many aquatic organisms use to extract dissolved oxygen from water and to excrete carbon dioxide. The gills of some species, such as hermit crabs, have adapted to allow respiration on land provided they are ...

s, absorbing oxygen

Oxygen is the chemical element with the symbol O and atomic number 8. It is a member of the chalcogen group in the periodic table, a highly reactive nonmetal, and an oxidizing agent that readily forms oxides with most elements as ...

from the water through their limbs and the inner membrane of their carapaces. The excretory organs of barnacles are maxillary glands.

The main sense of barnacles appears to be touch, with the hairs on the limbs being especially sensitive. The adult also has three photoreceptors (ocelli), one median and two lateral. These photoreceptors record the stimulus for the barnacle shadow reflex, where a sudden decrease in light causes cessation of the fishing rhythm and closing of the opercular plates. The photoreceptors are likely only capable of sensing the difference between light and dark. This eye is derived from the primary naupliar eye.

Life cycle

Barnacles have two distinct larval stages, the nauplius and the cyprid, before developing into a mature adult.Nauplius

A fertilised egg hatches into a nauplius: a one-eyed larva comprising a head and a

A fertilised egg hatches into a nauplius: a one-eyed larva comprising a head and a telson

The telson () is the posterior-most division of the body of an arthropod. Depending on the definition, the telson is either considered to be the final segment of the arthropod body, or an additional division that is not a true segment on accou ...

, without a thorax or abdomen. This undergoes six moults, passing through five instar

An instar (, from the Latin '' īnstar'', "form", "likeness") is a developmental stage of arthropods, such as insects, between each moult (''ecdysis''), until sexual maturity is reached. Arthropods must shed the exoskeleton in order to grow or ...

s, before transforming into the cyprid stage. Nauplii are typically initially brooded by the parent, and released after the first moult as larvae that swim freely using seta

In biology, setae (singular seta ; from the Latin word for " bristle") are any of a number of different bristle- or hair-like structures on living organisms.

Animal setae

Protostomes

Annelid setae are stiff bristles present on the body. ...

e.

Cyprid

The cyprid larva is the last larval stage before adulthood. It is not a feeding stage; its role is to find a suitable place to settle, since the adults aresessile

Sessility, or sessile, may refer to:

* Sessility (motility), organisms which are not able to move about

* Sessility (botany), flowers or leaves that grow directly from the stem or peduncle of a plant

* Sessility (medicine), tumors and polyps that ...

. The cyprid stage lasts from days to weeks. It explores potential surfaces with modified antennules; once it has found a potentially suitable spot, it attaches head-first using its antennules and a secreted glycoproteinous substance. Larvae assess surfaces based upon their surface texture, chemistry, relative wettability, color, and the presence or absence and composition of a surface biofilm

A biofilm comprises any syntrophic consortium of microorganisms in which cells stick to each other and often also to a surface. These adherent cells become embedded within a slimy extracellular matrix that is composed of extracellular ...

; swarming species are also more likely to attach near other barnacles. As the larva exhausts its finite energy reserves, it becomes less selective in the sites it selects. It cements itself permanently to the substrate with another proteinaceous compound, and then undergoes metamorphosis into a juvenile barnacle.

Adult

Typical acorn barnacles develop six hard calcareous plates to surround and protect their bodies. For the rest of their lives, they are cemented to the substrate, using their feathery legs (cirri) to capture plankton. Once metamorphosis is over and they have reached their adult form, barnacles continue to grow by adding new material to their heavily calcified plates. These plates are not moulted; however, like all ecdysozoans, the barnacle itself will still moult its cuticle.Sexual reproduction

Most barnacles arehermaphroditic

In reproductive biology, a hermaphrodite () is an organism that has both kinds of reproductive organs and can produce both gametes associated with male and female sexes.

Many taxonomic groups of animals (mostly invertebrates) do not have s ...

, although a few species are gonochoric

In biology, gonochorism is a sexual system where there are only two sexes and each individual organism is either male or female. The term gonochorism is usually applied in animal species, the vast majority of which are gonochoric.

Gonochorism c ...

or androdioecious. The ovaries are located in the base or stalk, and may extend into the mantle, while the testes are towards the back of the head, often extending into the thorax. Typically, recently moulted hermaphroditic individuals are receptive as females. Self-fertilization, although theoretically possible, has been experimentally shown to be rare in barnacles.

The sessile lifestyle of barnacles makes sexual reproduction

Sexual reproduction is a type of reproduction that involves a complex life cycle in which a gamete ( haploid reproductive cells, such as a sperm or egg cell) with a single set of chromosomes combines with another gamete to produce a zygote th ...

difficult, as the organisms cannot leave their shells to mate. To facilitate genetic transfer between isolated individuals, barnacles have extraordinarily long penis

A penis (plural ''penises'' or ''penes'' () is the primary sexual organ that male animals use to inseminate females (or hermaphrodites) during copulation. Such organs occur in many animals, both vertebrate and invertebrate, but males d ...

es. Barnacles probably have the largest penis to body size ratio of the animal kingdom, up to eight times their body length.

Barnacles can also reproduce through a method called spermcasting, in which the male barnacle releases his sperm into the water and females pick it up and fertilise their eggs.

The Rhizocephala

Rhizocephala are derived barnacles that parasitise mostly decapod crustaceans, but can also infest Peracarida, mantis shrimps and thoracican barnacles, and are found from the deep ocean to freshwater. Together with their sister groups Thoracic ...

superorder used to be considered hermaphroditic, but it turned out that its males inject themselves into the female's body, degrading to the condition of nothing more than sperm-producing cells.

Ecology

Most barnacles are suspension feeders; they dwell continually in their shells, which are usually constructed of six plates, and reach into the water column with modified legs. These feathery appendages beat rhythmically to drawplankton

Plankton are the diverse collection of organisms found in water (or air) that are unable to propel themselves against a current (or wind). The individual organisms constituting plankton are called plankters. In the ocean, they provide a crucia ...

and detritus into the shell for consumption.

Other members of the class have quite a different mode of life. For example, members of the superorder Rhizocephala

Rhizocephala are derived barnacles that parasitise mostly decapod crustaceans, but can also infest Peracarida, mantis shrimps and thoracican barnacles, and are found from the deep ocean to freshwater. Together with their sister groups Thoracic ...

, including the genus

Genus ( plural genera ) is a taxonomic rank used in the biological classification of living and fossil organisms as well as viruses. In the hierarchy of biological classification, genus comes above species and below family. In binomial nom ...

''Sacculina

''Sacculina'' is a genus of barnacles that is a parasitic castrator of crabs. They belong to a group called ''Rhizocephala''. The adults bear no resemblance to the barnacles that cover ships and piers; they are recognised as barnacles because t ...

'', are parasitic

Parasitism is a close relationship between species, where one organism, the parasite, lives on or inside another organism, the host, causing it some harm, and is adapted structurally to this way of life. The entomologist E. O. Wilson ha ...

and live within crabs.

Although they have been found at water depths to , most barnacles inhabit shallow waters, with 75% of species living in water depths less than , and 25% inhabiting the intertidal zone. Within the intertidal zone, different species of barnacles live in very tightly constrained locations, allowing the exact height of an assemblage above or below sea level to be precisely determined.

Since the intertidal zone periodically desiccates, barnacles are well adapted against water loss. Their calcite shells are impermeable, and they possess two plates which they can slide across their apertures when not feeding. These plates also protect against predation.

Barnacles are displaced by limpets and mussels, which compete for space. They also have numerous predators. They employ two strategies to overwhelm their competitors: "swamping" and fast growth. In the swamping strategy, vast numbers of barnacles settle in the same place at once, covering a large patch of substrate, allowing at least some to survive in the balance of probabilities. Fast growth allows the suspension feeders to access higher levels of the water column than their competitors, and to be large enough to resist displacement; species employing this response, such as the aptly named '' Megabalanus'', can reach in length; other species may grow larger still ('' Austromegabalanus psittacus'').

Competitors may include other barnacles, and disputed evidence indicates balanoid barnacles competitively displaced chthalamoid barnacles. Balanoids gained their advantage over the chthalamoids in the Oligocene, when they evolved tubular skeletons, which provide better anchorage to the substrate, and allow them to grow faster, undercutting, crushing, and smothering chthalamoids.

Among the most common predators on barnacles are whelk

Whelk (also known as scungilli) is a common name applied to various kinds of sea snail. Although a number of whelks are relatively large and are in the family Buccinidae (the true whelks), the word ''whelk'' is also applied to some other marin ...

s. They are able to grind through the calcareous exoskeletons of barnacles and feed on the softer inside parts. Mussels also prey on barnacle larvae. Another predator on barnacles is the starfish species '' Pisaster ochraceus''.

Miocene

The Miocene ( ) is the first epoch (geology), geological epoch of the Neogene Period and extends from about (Ma). The Miocene was named by Scottish geologist Charles Lyell; the name comes from the Greek words (', "less") and (', "new") and mea ...

) showing internal plates in bioimmured smaller barnacles

History of taxonomy

Barnacles were originally classified by

Barnacles were originally classified by Linnaeus

Carl Linnaeus (; 23 May 1707 – 10 January 1778), also known after his ennoblement in 1761 as Carl von Linné Blunt (2004), p. 171. (), was a Swedish botanist, zoologist, taxonomist, and physician who formalised binomial nomenclature, the ...

and Cuvier as Mollusca, but in 1830 John Vaughan Thompson

John Vaughan Thompson FLS (19 November 1779 – 21 January 1847) was a British military surgeon, marine biologist, zoologist, botanist, and published naturalist.

Early years

John Vaughan Thompson was born in British controlled Brooklyn on Lon ...

published observations showing the metamorphosis of the nauplius and cypris larvae into adult barnacles, and noted how these larvae were similar to those of crustaceans. In 1834 Hermann Burmeister

Karl Hermann Konrad Burmeister (also known as Carlos Germán Conrado Burmeister) (15 January 1807 – 2 May 1892) was a German Argentine zoologist, entomologist, herpetologist, botanist, and coleopterologist. He served as a professor at the Uni ...

published further information, reinterpreting these findings. The effect was to move barnacles from the phylum of Mollusca to Articulata, showing naturalists that detailed study was needed to reevaluate their taxonomy

Taxonomy is the practice and science of categorization or classification.

A taxonomy (or taxonomical classification) is a scheme of classification, especially a hierarchical classification, in which things are organized into groups or types. ...

.

Charles Darwin

Charles Robert Darwin ( ; 12 February 1809 – 19 April 1882) was an English naturalist, geologist, and biologist, widely known for his contributions to evolutionary biology. His proposition that all species of life have descended ...

took up this challenge in 1846, and developed his initial interest into a major study published as a series of monographs

A monograph is a specialist work of writing (in contrast to reference works) or exhibition on a single subject or an aspect of a subject, often by a single author or artist, and usually on a scholarly subject.

In library cataloging, ''monograp ...

in 1851 and 1854. Darwin undertook this study, at the suggestion of his friend Joseph Dalton Hooker

Sir Joseph Dalton Hooker (30 June 1817 – 10 December 1911) was a British botanist and explorer in the 19th century. He was a founder of geographical botany and Charles Darwin's closest friend. For twenty years he served as director of ...

, to thoroughly understand at least one species before making the generalisations needed for his theory of evolution

Evolution is change in the heritable characteristics of biological populations over successive generations. These characteristics are the expressions of genes, which are passed on from parent to offspring during reproduction. Variation ...

by natural selection

Natural selection is the differential survival and reproduction of individuals due to differences in phenotype. It is a key mechanism of evolution, the change in the heritable traits characteristic of a population over generations. Cha ...

.

Classification

Some authorities regard the Cirripedia as a full class or subclass, and the orders listed above are sometimes treated as superorders. In 2001, Martin and Davis placed Cirripedia as an infraclass ofThecostraca

Thecostraca is a Class (biology), class of marine invertebrates containing over 2,200 described species. Many species have planktonic larvae which become Sessility (zoology), sessile or parasite, parasitic as adults.

The most important subgroup ...

and divided it into six orders:

*Infraclass Cirripedia Burmeister, 1834

** Superorder Acrothoracica

The Acrothoracica are an infraclass of barnacles.

Acrothoracicans bore into calcareous material such as mollusc shells, coral, crinoids or hardgrounds, producing a slit-like hole in the surface known by the trace fossil name ''Rogerella''. A ...

Gruvel, 1905

*** Order Pygophora Berndt, 1907

*** Order Apygophora Berndt, 1907

** Superorder Rhizocephala

Rhizocephala are derived barnacles that parasitise mostly decapod crustaceans, but can also infest Peracarida, mantis shrimps and thoracican barnacles, and are found from the deep ocean to freshwater. Together with their sister groups Thoracic ...

Müller, 1862

*** Order Kentrogonida Delage, 1884

*** Order Akentrogonida Häfele, 1911

** Superorder Thoracica Darwin, 1854

*** Order Pedunculata Lamarck

Jean-Baptiste Pierre Antoine de Monet, chevalier de Lamarck (1 August 1744 – 18 December 1829), often known simply as Lamarck (; ), was a French naturalist, biologist, academic, and soldier. He was an early proponent of the idea that biolo ...

, 1818

*** Order Sessilia Lamarck, 1818

In 2021, Chan et al. elevated Cirripedia to subclass of the class Thecostraca

Thecostraca is a Class (biology), class of marine invertebrates containing over 2,200 described species. Many species have planktonic larvae which become Sessility (zoology), sessile or parasite, parasitic as adults.

The most important subgroup ...

, and the superorders Acrothoracica, Rhizocephala, and Thoracica to infraclass. The updated classification, which now includes 11 orders, has been accepted in the World Register of Marine Species.

* Subclass Cirripedia Burmeister, 1834

** Infraclass Acrothoracica

The Acrothoracica are an infraclass of barnacles.

Acrothoracicans bore into calcareous material such as mollusc shells, coral, crinoids or hardgrounds, producing a slit-like hole in the surface known by the trace fossil name ''Rogerella''. A ...

Gruvel, 1905

*** Order Cryptophialida

Cryptophialidae is a family of Acrothoracica

The Acrothoracica are an infraclass of barnacles.

Acrothoracicans bore into calcareous material such as mollusc shells, coral, crinoids or hardgrounds, producing a slit-like hole in the surface ...

Kolbasov, Newman & Hoeg, 2009

*** Order Lithoglyptida Kolbasov, Newman & Hoeg, 2009

** Infraclass Rhizocephala

Rhizocephala are derived barnacles that parasitise mostly decapod crustaceans, but can also infest Peracarida, mantis shrimps and thoracican barnacles, and are found from the deep ocean to freshwater. Together with their sister groups Thoracic ...

Müller, 1862

** Infraclass Thoracica Darwin, 1854

*** Superorder Phosphatothoracica Gale, 2019

**** Order Iblomorpha Buckeridge & Newman, 2006

**** Order † Eolepadomorpha Chan et al., 2021

*** Superorder Thoracicalcarea Gale, 2015

**** Order Calanticomorpha

Calanticomorpha is an order of acorn barnacles in the class Thecostraca. There are 3 families and more than 90 described species in Calanticomorpha.

Families

These families and genera belong to the order Calanticomorpha:

: Order Calanticomorpha C ...

Chan et al., 2021

**** Order Pollicipedomorpha

Pollicipedomorpha is an order of pedunculated barnacles in the class Thecostraca. There are 3 families and more than 30 described species in Pollicipedomorpha.

Families

These families and genera belong to the order Pollicipedomorpha:

: Order Poll ...

Chan et al., 2021

**** Order Scalpellomorpha

Scalpellomorpha is an order of acorn barnacles in the class Thecostraca

Thecostraca is a Class (biology), class of marine invertebrates containing over 2,200 described species. Many species have planktonic larvae which become Sessility (zoology ...

Buckeridge & Newman, 2006

**** Order † Archaeolepadomorpha

Archaeolepadomorpha is an extinct order of barnacles in the class Thecostraca

Thecostraca is a Class (biology), class of marine invertebrates containing over 2,200 described species. Many species have planktonic larvae which become Sessility (z ...

Chan et al., 2021

**** Order † Brachylepadomorpha

Brachylepadidae is an extinct family of barnacles in the order Brachylepadomorpha, the sole family in the order. There are about 7 genera and more than 20 described species in Brachylepadidae.

Genera

These genera belong to the family Brachylepad ...

Withers, 1923

**** (Unranked) Sessilia

***** Order Balanomorpha Pilsbry, 1916

***** Order Verrucomorpha

Verrucomorpha is an order of asymmetrical sessile barnacles in the class Thecostraca. They are typically found in deeper and deep-sea habitats. There are 2 families and more than 100 described species in Verrucomorpha.

Families

These families be ...

Pilsbry, 1916

Fossil record

The oldest definitive fossil barnacle is '' Praelepas'' from the mid- Carboniferous, around 330-320 million years ago. Older claimed barnacles such as ''Priscansermarinus

''Priscansermarinus barnetti'' is an organism known from the Middle Cambrian Burgess Shale which was originally interpreted as a species of lepadomorph barnacle. Four specimens of ''P. barnetti'' are known from the Greater Phyllopod bed. A reflec ...

'' from the Middle Cambrian

Middle or The Middle may refer to:

* Centre (geometry), the point equally distant from the outer limits.

Places

* Middle (sheading), a subdivision of the Isle of Man

* Middle Bay (disambiguation)

* Middle Brook (disambiguation)

* Middle Creek ...

(on the order of ) In A. J. Southward (ed.), 1987. do not show clear barnacle morphological traits. Barnacles first radiated and became diverse during the Late Cretaceous

The Cretaceous ( ) is a geological period that lasted from about 145 to 66 million years ago (Mya). It is the third and final period of the Mesozoic Era, as well as the longest. At around 79 million years, it is the longest geological period of ...

. Barnacles underwent a second, much larger radiation beginning during the Neogene (last 23 million years), which continues to present. In part, their poor skeletal preservation is due to their restriction to high-energy environments, which tend to be erosion

Erosion is the action of surface processes (such as water flow or wind) that removes soil, rock, or dissolved material from one location on the Earth's crust, and then transports it to another location where it is deposited. Erosion is dis ...

al – therefore it is more common for their shells to be ground up by wave action than for them to reach a depositional setting.

Barnacles can play an important role in estimating paleo-water depths. The degree of disarticulation of fossils suggests the distance they have been transported, and since many species have narrow ranges of water depths, it can be assumed that the animals lived in shallow water and broke up as they were washed down-slope. The completeness of fossils, and nature of damage, can thus be used to constrain the tectonic history of regions.

Charles Darwin

Charles Robert Darwin ( ; 12 February 1809 – 19 April 1882) was an English naturalist, geologist, and biologist, widely known for his contributions to evolutionary biology. His proposition that all species of life have descended ...

File:Megabalanus on breccia.JPG, Miocene

The Miocene ( ) is the first epoch (geology), geological epoch of the Neogene Period and extends from about (Ma). The Miocene was named by Scottish geologist Charles Lyell; the name comes from the Greek words (', "less") and (', "new") and mea ...

( Messinian) '' Megabalanus'', smothered by sand and fossilised

File:Chesaconcavus top view.jpg, ''Chesaconcavus'', a Miocene barnacle from Maryland

Relationship with humans

Barnacles are of economic consequence, as they often attach themselves to synthetic structures, sometimes to the structure's detriment. Particularly in the case of ships, they are classified asfouling

Fouling is the accumulation of unwanted material on solid surfaces. The fouling materials can consist of either living organisms ( biofouling) or a non-living substance (inorganic or organic). Fouling is usually distinguished from other sur ...

organisms. The number and size of barnacles that cover ships can impair their efficiency by causing hydrodynamic

In physics and engineering, fluid dynamics is a subdiscipline of fluid mechanics that describes the flow of fluids— liquids and gases. It has several subdisciplines, including '' aerodynamics'' (the study of air and other gases in motion) a ...

drag. This is not a problem for boats on inland waterways, as barnacles are exclusively marine.

The stable isotope

Isotopes are two or more types of atoms that have the same atomic number (number of protons in their nuclei) and position in the periodic table (and hence belong to the same chemical element), and that differ in nucleon numbers (mass numb ...

signals in the layers of barnacle shells can potentially be used as a forensic tracking method for whale

Whales are a widely distributed and diverse group of fully aquatic placental marine mammals. As an informal and colloquial grouping, they correspond to large members of the infraorder Cetacea, i.e. all cetaceans apart from dolphins and ...

s, loggerhead turtle

The loggerhead sea turtle (''Caretta caretta'') is a species of oceanic turtle distributed throughout the world. It is a marine reptile, belonging to the family Cheloniidae. The average loggerhead measures around in carapace length when fully ...

s and marine debris, such as shipwrecks or a flaperon

A flaperon (a portmanteau of flap and aileron) on an aircraft's wing is a type of control surface that combines the functions of both flaps and ailerons. Some smaller kitplanes have flaperons for reasons of simplicity of manufacture, while ...

suspected to be from Malaysia Airlines Flight 370.

The flesh of some barnacles is routinely consumed by humans, including Japanese goose barnacles (''e.g.'' '' Capitulum mitella''), and goose barnacle

Goose barnacles, also called stalked barnacles or gooseneck barnacles, are filter-feeding crustaceans that live attached to hard surfaces of rocks and flotsam in the ocean intertidal zone. Goose barnacles formerly made up the taxonomic order P ...

s (''e.g.'' '' Pollicipes pollicipes''), a delicacy in Spain

, image_flag = Bandera de España.svg

, image_coat = Escudo de España (mazonado).svg

, national_motto = ''Plus ultra'' (Latin)(English: "Further Beyond")

, national_anthem = (English: "Royal March")

, i ...

and Portugal

Portugal, officially the Portuguese Republic ( pt, República Portuguesa, links=yes ), is a country whose mainland is located on the Iberian Peninsula of Southwestern Europe, and whose territory also includes the Atlantic archipelagos of ...

. The resemblance of this barnacle's fleshy stalk to a goose's neck gave rise, in ancient times, to the notion that geese literally grew from the barnacle. Indeed, the word "barnacle" originally referred to a species of goose, the barnacle goose

The barnacle goose (''Branta leucopsis'') is a species of goose that belongs to the genus '' Branta'' of black geese, which contains species with largely black plumage, distinguishing them from the grey ''Anser'' species. Despite its superficial ...

''Branta leucopsis'', whose eggs and young were rarely seen by humans because it breeds in the remote Arctic

The Arctic ( or ) is a polar region located at the northernmost part of Earth. The Arctic consists of the Arctic Ocean, adjacent seas, and parts of Canada (Yukon, Northwest Territories, Nunavut), Danish Realm (Greenland), Finland, Iceland, N ...

.

Additionally, the picoroco barnacle is used in Chilean cuisine

Chilean cuisine stems mainly from the combination of traditional Spanish cuisine, Chilean Mapuche culture and local ingredients, with later important influences from other European cuisines, particularly from Germany, the United Kingdom and ...

and is one of the ingredients in '' curanto'' seafood stew.

MIT

The Massachusetts Institute of Technology (MIT) is a private land-grant research university in Cambridge, Massachusetts. Established in 1861, MIT has played a key role in the development of modern technology and science, and is one of the m ...

researchers developed an adhesive, inspired by a protein-based bioglue produced by barnacles to firmly attach to rocks, which can form a tight seal to halt bleeding

Bleeding, hemorrhage, haemorrhage or blood loss, is blood escaping from the circulatory system from damaged blood vessels. Bleeding can occur internally, or externally either through a natural opening such as the mouth, nose, ear, urethra, vag ...

within about 15 seconds of application.

Siuslaw River

The Siuslaw River ( ) is a river, about long, that flows to the Pacific Ocean coast of Oregon in the United States. It drains an area of about in the Central Oregon Coast Range southwest of the Willamette Valley and north of the watershed of th ...

in Oregon

Oregon () is a state in the Pacific Northwest region of the Western United States. The Columbia River delineates much of Oregon's northern boundary with Washington, while the Snake River delineates much of its eastern boundary with Idaho. T ...

File:Percebes.iguaria.jpg, Goose barnacle

Goose barnacles, also called stalked barnacles or gooseneck barnacles, are filter-feeding crustaceans that live attached to hard surfaces of rocks and flotsam in the ocean intertidal zone. Goose barnacles formerly made up the taxonomic order P ...

s in a restaurant in Madrid

Madrid ( , ) is the capital and most populous city of Spain. The city has almost 3.4 million inhabitants and a Madrid metropolitan area, metropolitan area population of approximately 6.7 million. It is the Largest cities of the Europ ...

See also

*List of Cirripedia genera

These genera belong to Cirripedia, a subclass of barnacles in the phylum of Crustacea, as classified by Chan et al. (2021) and the World Register of Marine Species. Their classification into order, superfamily, family, and subfamily is included.

...

References

Further reading

*External links

Barnacles

from the Marine Education Society of Australasia

Article on barnacles in Spain, and their collection and gastronomy. * * * * {{Authority control Parasitic crustaceans Maxillopoda Articles containing video clips Extant Cambrian first appearances