The Churchill war ministry was the

United Kingdom

The United Kingdom of Great Britain and Northern Ireland, commonly known as the United Kingdom (UK) or Britain, is a country in Europe, off the north-western coast of the continental mainland. It comprises England, Scotland, Wales and ...

's

coalition government

A coalition government is a form of government in which political parties cooperate to form a government. The usual reason for such an arrangement is that no single party has achieved an absolute majority after an election, an atypical outcome in ...

for most of the

Second World War

World War II or the Second World War, often abbreviated as WWII or WW2, was a world war that lasted from 1939 to 1945. It involved the vast majority of the world's countries—including all of the great powers—forming two opposi ...

from 10 May 1940 to 23 May 1945. It was led by

Winston Churchill

Sir Winston Leonard Spencer Churchill (30 November 187424 January 1965) was a British statesman, soldier, and writer who served as Prime Minister of the United Kingdom twice, from 1940 to 1945 during the Second World War, and again from ...

, who was appointed

Prime Minister

A prime minister, premier or chief of cabinet is the head of the cabinet and the leader of the ministers in the executive branch of government, often in a parliamentary or semi-presidential system. Under those systems, a prime minister is ...

by

King George VI

George VI (Albert Frederick Arthur George; 14 December 1895 – 6 February 1952) was King of the United Kingdom and the Dominions of the British Commonwealth from 11 December 1936 until his death in 1952. He was also the last Emperor of In ...

following the resignation of

Neville Chamberlain

Arthur Neville Chamberlain (; 18 March 18699 November 1940) was a British politician of the Conservative Party who served as Prime Minister of the United Kingdom from May 1937 to May 1940. He is best known for his foreign policy of appeaseme ...

in the aftermath of the

Norway Debate

The Norway Debate, sometimes called the Narvik Debate, was a momentous debate in the British House of Commons from 7 to 9 May 1940, during the Second World War. The official title of the debate, as held in the '' Hansard'' parliamentary archiv ...

.

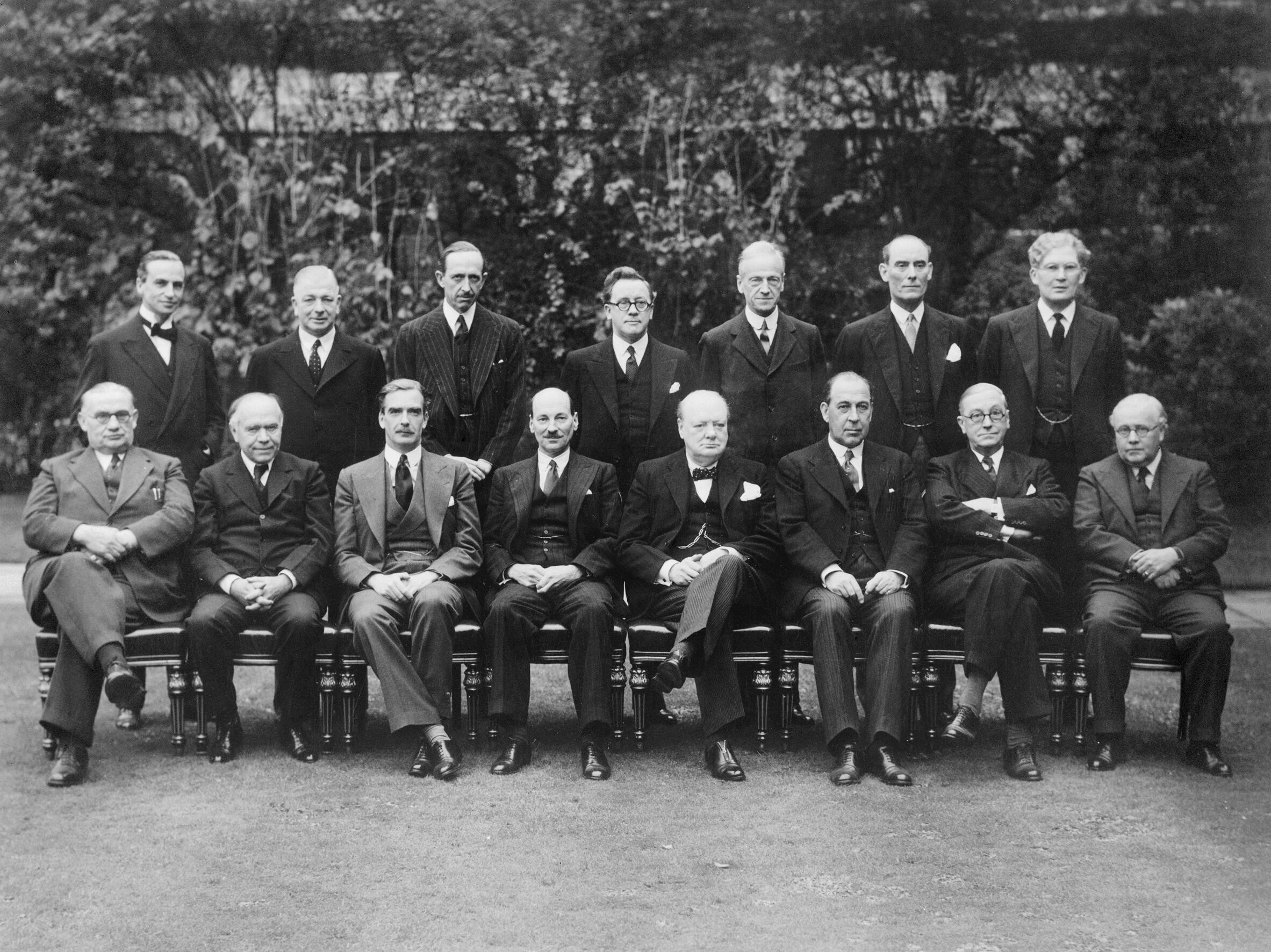

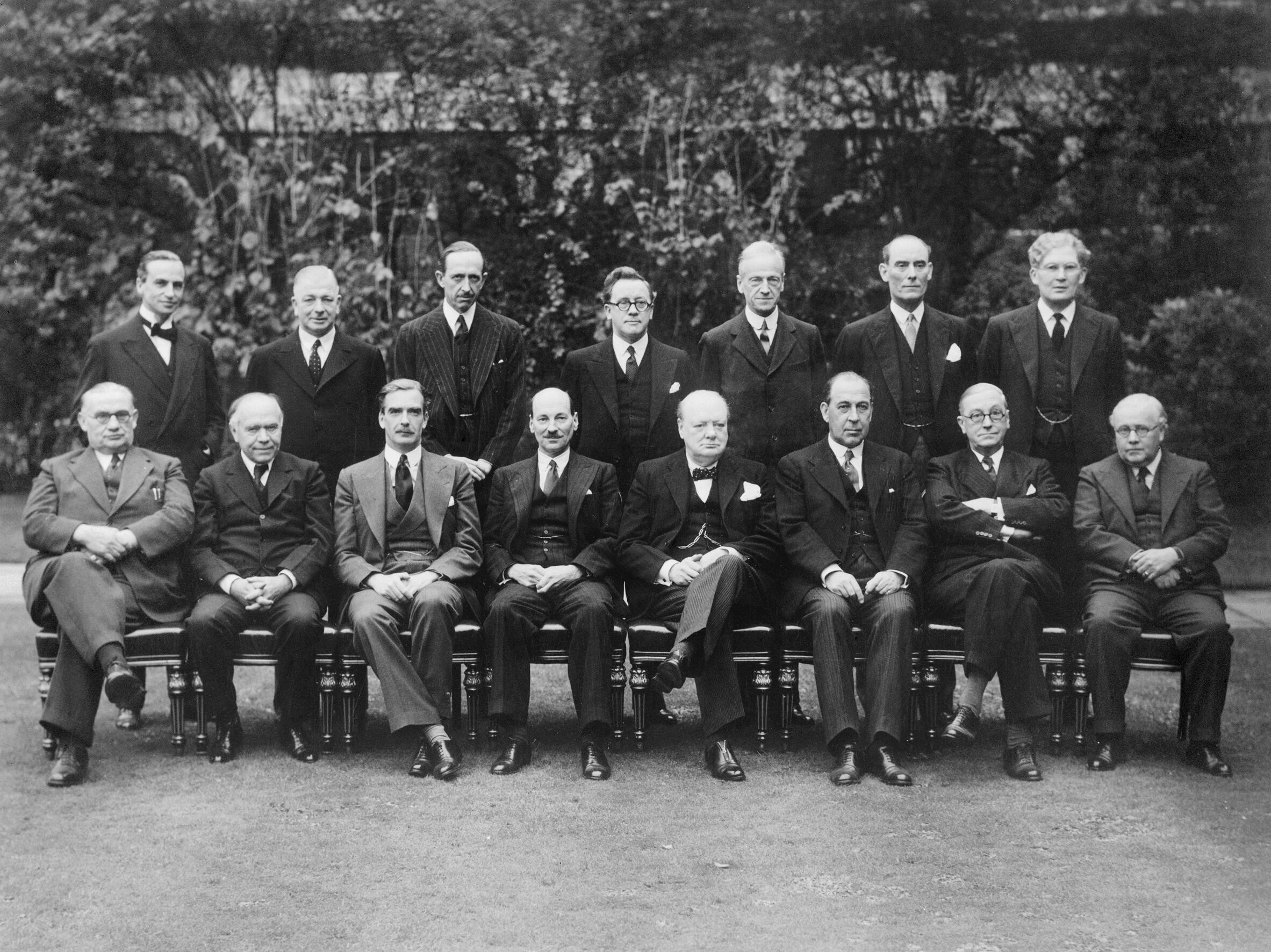

At the outset, Churchill formed a five-man war cabinet which included Chamberlain as

Lord President of the Council

The lord president of the Council is the presiding officer of the Privy Council of the United Kingdom and the fourth of the Great Officers of State, ranking below the Lord High Treasurer but above the Lord Keeper of the Privy Seal. The Lord ...

,

Clement Attlee

Clement Richard Attlee, 1st Earl Attlee, (3 January 18838 October 1967) was a British politician who served as Prime Minister of the United Kingdom from 1945 to 1951 and Leader of the Labour Party from 1935 to 1955. He was Deputy Prime Mini ...

as

Lord Privy Seal

The Lord Privy Seal (or, more formally, the Lord Keeper of the Privy Seal) is the fifth of the Great Officers of State in the United Kingdom, ranking beneath the Lord President of the Council and above the Lord Great Chamberlain. Originally, ...

and later as

Deputy Prime Minister

A deputy prime minister or vice prime minister is, in some countries, a government minister who can take the position of acting prime minister when the prime minister is temporarily absent. The position is often likened to that of a vice president, ...

,

Viscount Halifax

A viscount ( , for male) or viscountess (, for female) is a title used in certain European countries for a noble of varying status.

In many countries a viscount, and its historical equivalents, was a non-hereditary, administrative or judicial ...

as

Foreign Secretary

The secretary of state for foreign, Commonwealth and development affairs, known as the foreign secretary, is a Secretary of State (United Kingdom), minister of the Crown of the Government of the United Kingdom and head of the Foreign, Commonwe ...

and

Arthur Greenwood as a

minister without portfolio

A minister without portfolio is either a government minister with no specific responsibilities or a minister who does not head a particular ministry. The sinecure is particularly common in countries ruled by coalition governments and a cabinet ...

. Although the original war cabinet was limited to five members, in practice they were augmented by the service chiefs and ministers who attended the majority of meetings. The cabinet changed in size and membership as the war progressed but there were significant additions later in 1940 when it was increased to eight after Churchill, Attlee and Greenwood were joined by

Ernest Bevin

Ernest Bevin (9 March 1881 – 14 April 1951) was a British statesman, trade union leader, and Labour Party (UK), Labour Party politician. He co-founded and served as General Secretary of the powerful Transport and General Workers' Union in th ...

as

Minister of Labour and National Service

The Secretary of State for Employment was a position in the Cabinet of the United Kingdom. In 1995 it was merged with Secretary of State for Education to make the Secretary of State for Education and Employment. In 2001 the employment functions w ...

;

Anthony Eden

Robert Anthony Eden, 1st Earl of Avon, (12 June 1897 – 14 January 1977) was a British Conservative Party politician who served as Prime Minister of the United Kingdom from 1955 until his resignation in 1957.

Achieving rapid promo ...

as Foreign Secretary – replacing Halifax, who was sent to Washington D.C. as ambassador to the United States;

Lord Beaverbrook

William Maxwell Aitken, 1st Baron Beaverbrook (25 May 1879 – 9 June 1964), generally known as Lord Beaverbrook, was a Canadian-British newspaper publisher and backstage politician who was an influential figure in British media and politics o ...

as

Minister of Aircraft Production

The Minister of Aircraft Production was, from 1940 to 1945, the British government minister at the Ministry of Aircraft Production, one of the specialised supply ministries set up by the British Government during World War II. It was responsible ...

; Sir

Kingsley Wood as

Chancellor of the Exchequer

The chancellor of the Exchequer, often abbreviated to chancellor, is a senior minister of the Crown within the Government of the United Kingdom, and head of HM Treasury, His Majesty's Treasury. As one of the four Great Offices of State, the Ch ...

and

Sir John Anderson

John Anderson, 1st Viscount Waverley, (8 July 1882 – 4 January 1958) was a Scottish civil servant and politician who is best known for his service in the War Cabinet during the Second World War, for which he was nicknamed the "Home Front P ...

as Lord President of the Council – replacing Chamberlain who died in November (Anderson later became Chancellor after Wood's death in September 1943).

The coalition was dissolved in May 1945, following the final defeat of Germany, when the

Labour Party decided to withdraw in order to prepare for a

general election

A general election is a political voting election where generally all or most members of a given political body are chosen. These are usually held for a nation, state, or territory's primary legislative body, and are different from by-elections ( ...

. Churchill, who was the leader of the

Conservative Party

The Conservative Party is a name used by many political parties around the world. These political parties are generally right-wing though their exact ideologies can range from center-right to far-right.

Political parties called The Conservative P ...

, was asked by the King to form a new, essentially Conservative, government. It was known as the

Churchill caretaker ministry and managed the country's affairs until completion of the general election on 26 July that year.

Background

The

1935 general election had resulted in a Conservative victory with a substantial majority and

Stanley Baldwin

Stanley Baldwin, 1st Earl Baldwin of Bewdley, (3 August 186714 December 1947) was a British Conservative Party politician who dominated the government of the United Kingdom between the world wars, serving as prime minister on three occasions, ...

became Prime Minister. In May 1937, Baldwin retired and was succeeded by

Neville Chamberlain

Arthur Neville Chamberlain (; 18 March 18699 November 1940) was a British politician of the Conservative Party who served as Prime Minister of the United Kingdom from May 1937 to May 1940. He is best known for his foreign policy of appeaseme ...

who continued Baldwin's foreign policy of

appeasement

Appeasement in an international context is a diplomatic policy of making political, material, or territorial concessions to an aggressive power in order to avoid conflict. The term is most often applied to the foreign policy of the UK governme ...

in the face of German, Italian and Japanese aggression. Having signed the

Munich Agreement

The Munich Agreement ( cs, Mnichovská dohoda; sk, Mníchovská dohoda; german: Münchner Abkommen) was an agreement concluded at Munich on 30 September 1938, by Germany, the United Kingdom, France, and Italy. It provided "cession to Germany ...

with

Hitler

Adolf Hitler (; 20 April 188930 April 1945) was an Austrian-born German politician who was dictator of Nazi Germany, Germany from 1933 until Death of Adolf Hitler, his death in 1945. Adolf Hitler's rise to power, He rose to power as the le ...

in 1938, Chamberlain became alarmed by the dictator's continuing aggression and, in March 1939, signed the

Anglo-Polish military alliance

The military alliance between the United Kingdom and Poland was formalised by the Anglo-Polish Agreement in 1939, with subsequent addenda of 1940 and 1944, for mutual assistance in case of a military invasion from Nazi Germany, as specified in a ...

which supposedly guaranteed British support for Poland if attacked. Chamberlain issued the

declaration of war

A declaration of war is a formal act by which one state announces existing or impending war activity against another. The declaration is a performative speech act (or the signing of a document) by an authorized party of a national government, ...

against Germany on 3 September 1939 and formed a war cabinet which included

Winston Churchill

Sir Winston Leonard Spencer Churchill (30 November 187424 January 1965) was a British statesman, soldier, and writer who served as Prime Minister of the United Kingdom twice, from 1940 to 1945 during the Second World War, and again from ...

(out of office since June 1929) as

First Lord of the Admiralty

The First Lord of the Admiralty, or formally the Office of the First Lord of the Admiralty, was the political head of the English and later British Royal Navy. He was the government's senior adviser on all naval affairs, responsible for the di ...

.

Dissatisfaction with Chamberlain's leadership became widespread in the spring of 1940 after Germany successfully invaded Norway. In response, the

House of Commons

The House of Commons is the name for the elected lower house of the bicameral parliaments of the United Kingdom and Canada. In both of these countries, the Commons holds much more legislative power than the nominally upper house of parliament. T ...

held the

Norway Debate

The Norway Debate, sometimes called the Narvik Debate, was a momentous debate in the British House of Commons from 7 to 9 May 1940, during the Second World War. The official title of the debate, as held in the '' Hansard'' parliamentary archiv ...

from 7 to 9 May. At the end of the second day, the Labour opposition forced a

division which was in effect a

motion of no confidence

A motion of no confidence, also variously called a vote of no confidence, no-confidence motion, motion of confidence, or vote of confidence, is a statement or vote about whether a person in a position of responsibility like in government or mana ...

in Chamberlain. The government's majority of 213 was reduced to 81, still a victory but nevertheless a shattering blow for Chamberlain.

9–31 May 1940: Creation of a new government

9 May – Chamberlain considers his options

On Thursday, 9 May, Chamberlain attempted to form a National Coalition Government. In talks at

Downing Street

Downing Street is a street in Westminster in London that houses the official residences and offices of the Prime Minister of the United Kingdom and the Chancellor of the Exchequer. Situated off Whitehall, it is long, and a few minutes' walk f ...

with

Viscount Halifax

A viscount ( , for male) or viscountess (, for female) is a title used in certain European countries for a noble of varying status.

In many countries a viscount, and its historical equivalents, was a non-hereditary, administrative or judicial ...

and Churchill, he indicated that he was quite ready to resign if that was necessary for Labour to enter such a government. Labour's leader

Clement Attlee

Clement Richard Attlee, 1st Earl Attlee, (3 January 18838 October 1967) was a British politician who served as Prime Minister of the United Kingdom from 1945 to 1951 and Leader of the Labour Party from 1935 to 1955. He was Deputy Prime Mini ...

and his deputy

Arthur Greenwood then joined the meeting, and when asked, they indicated that they must first consult their party's National Executive Committee (then in

Bournemouth

Bournemouth () is a coastal resort town in the Bournemouth, Christchurch and Poole council area of Dorset, England. At the 2011 census, the town had a population of 183,491, making it the largest town in Dorset. It is situated on the English ...

to prepare for the

annual conference), but it was unlikely they could serve in a government led by Chamberlain; they probably would be able to serve under some other Conservative.

[

] After Attlee and Greenwood left, Chamberlain asked whom he should recommend to the King as his successor. The version of events given by Churchill is that Chamberlain's preference for Halifax was obvious (Churchill implies that the spat between Churchill and the Labour benches the previous night had something to do with that); there was a long silence which Halifax eventually broke by saying he did not believe he could lead the government effectively as a member of the

After Attlee and Greenwood left, Chamberlain asked whom he should recommend to the King as his successor. The version of events given by Churchill is that Chamberlain's preference for Halifax was obvious (Churchill implies that the spat between Churchill and the Labour benches the previous night had something to do with that); there was a long silence which Halifax eventually broke by saying he did not believe he could lead the government effectively as a member of the House of Lords

The House of Lords, also known as the House of Peers, is the upper house of the Parliament of the United Kingdom. Membership is by appointment, heredity or official function. Like the House of Commons, it meets in the Palace of Westminst ...

instead of the House of Commons

The House of Commons is the name for the elected lower house of the bicameral parliaments of the United Kingdom and Canada. In both of these countries, the Commons holds much more legislative power than the nominally upper house of parliament. T ...

. Churchill's version gets the date wrong, and he fails to mention the presence of David Margesson, the government Chief Whip

The Chief Whip is a political leader whose task is to enforce the whipping system, which aims to ensure that legislators who are members of a political party attend and vote on legislation as the party leadership prescribes.

United Kingdom

...

.

Halifax's account omits the dramatic pause and gives an additional reason: "PM said I was the man mentioned as most acceptable. I said it would be hopeless position. If I was not in charge of the war (operations) and if I didn't lead in the House, I should be a cypher. I thought Winston was a better choice. Winston did ''not'' demur."[quoted in Gilbert, as from ] According to Halifax, Margesson then confirmed that the House of Commons had been veering to Churchill.

In a letter to Churchill written that night, Bob Boothby asserted that parliamentary opinion was hardening against Halifax, claiming in a postscript that according to Liberal MP Clement Davies

Edward Clement Davies (19 February 1884 – 23 March 1962) was a Welsh politician and leader of the Liberal Party from 1945 to 1956.

Early life and education

Edward Clement Davies was born on 19 February 1884 in Llanfyllin, Montgomeryshire ...

, "Attlee & Greenwood are unable to distinguish between the PM & Halifax and are ''not'' prepared to serve under the latter". Davies (who thought Chamberlain should go, and be replaced by Churchill) had lunched with Attlee and Greenwood (and argued his case) shortly before they saw Chamberlain. Labour's Hugh Dalton

Edward Hugh John Neale Dalton, Baron Dalton, (16 August 1887 – 13 February 1962) was a British Labour Party economist and politician who served as Chancellor of the Exchequer from 1945 to 1947. He shaped Labour Party foreign policy in the 19 ...

, however, noted in his diary entry for 9 May that he had spoken with Attlee, who "agrees with my preference for Halifax over Churchill, but we both think either would be tolerable".[quoted in ]

10 May – Churchill succeeds Chamberlain

On the morning of Friday, 10 May, Germany invaded the Netherlands, Belgium, and Luxembourg. Chamberlain initially felt that a change of government at such a time would be inappropriate, but upon being given confirmation that Labour would not serve under him, he announced to the war cabinet his intention to resign. Scarcely more than three days after he had opened the debate, Chamberlain went to Buckingham Palace

Buckingham Palace () is a London royal residence and the administrative headquarters of the monarch of the United Kingdom. Located in the City of Westminster, the palace is often at the centre of state occasions and royal hospitality. It ...

to resign as Prime Minister. Despite resigning as PM, however, he continued to be the leader of the Conservative Party. He explained to the King why Halifax, whom the King thought the obvious candidate, did not want to become Prime Minister. The King then sent for Churchill and asked him to form a new government; according to Churchill, there was no stipulation that it must be a coalition government.

At 21:00 on 10 May, Chamberlain announced the change of Prime Minister over the BBC. Churchill's first act as Prime Minister was to ask Attlee and Greenwood to come and see him at Admiralty House. Next, he wrote to Chamberlain to thank him for his promised support. He then began to construct his coalition cabinet with the assistance of Attlee and Greenwood. Their conference went on into the early hours of Saturday and they reached a broad agreement on the composition of the new war cabinet, subject to Labour Party confirmation. Attlee and Greenwood were confident of securing this on Saturday after Churchill promised that more than a third of government positions would be offered to Labour members, including some of the key posts.

11/12 May – formation of the national government

On Saturday, 11 May, the Labour Party agreed to join a national government under Churchill's leadership and he was able to confirm his war cabinet. In his biography of Churchill,

On Saturday, 11 May, the Labour Party agreed to join a national government under Churchill's leadership and he was able to confirm his war cabinet. In his biography of Churchill, Roy Jenkins

Roy Harris Jenkins, Baron Jenkins of Hillhead, (11 November 1920 – 5 January 2003) was a British politician who served as President of the European Commission from 1977 to 1981. At various times a Member of Parliament (MP) for the Lab ...

described the Churchill cabinet as one "for winning", while the former Chamberlain cabinet was one "for losing". Labour leader Clement Attlee relinquished his official role as Leader of the Opposition

The Leader of the Opposition is a title traditionally held by the leader of the largest political party not in government, typical in countries utilizing the parliamentary system form of government. The leader of the opposition is typically se ...

to become Lord Privy Seal

The Lord Privy Seal (or, more formally, the Lord Keeper of the Privy Seal) is the fifth of the Great Officers of State in the United Kingdom, ranking beneath the Lord President of the Council and above the Lord Great Chamberlain. Originally, ...

(until 19 February 1942 when he was appointed Deputy Prime Minister

A deputy prime minister or vice prime minister is, in some countries, a government minister who can take the position of acting prime minister when the prime minister is temporarily absent. The position is often likened to that of a vice president, ...

). Arthur Greenwood, Labour's deputy leader, was appointed a minister without portfolio

A minister without portfolio is either a government minister with no specific responsibilities or a minister who does not head a particular ministry. The sinecure is particularly common in countries ruled by coalition governments and a cabinet ...

.

There was no ''de facto'' Leader of the Opposition from 11 May 1940 until Attlee resumed the role on 23 May 1945. The Labour Party appointed an acting Leader of the Opposition whose job, although he was in effect a member of the national government, was to ensure the continued functionality of the House of Commons. Due process in the Commons requires someone, even a member of the government, to fill the role even if there is no actual opposition.Hastings Lees-Smith

Hastings Bertrand Lees-Smith PC (26 January 1878 – 18 December 1941) was a British Liberal turned Labour politician who was briefly in the cabinet as President of the Board of Education in 1931. He was the acting Leader of the Opposition and ...

, the MP for Keighley

Keighley ( ) is a market town and a civil parish

in the City of Bradford Borough of West Yorkshire, England. It is the second largest settlement in the borough, after Bradford.

Keighley is north-west of Bradford city centre, north-west o ...

, who died in office on 18 December 1941. He was briefly succeeded by Frederick Pethick-Lawrence

Frederick William Pethick-Lawrence, 1st Baron Pethick-Lawrence, PC (né Lawrence; 28 December 1871 – 10 September 1961) was a British Labour politician who, among other things, campaigned for women's suffrage.

Background and education

B ...

and then by Arthur Greenwood, who had left the war cabinet, from 22 February 1942 until 23 May 1945.

The main problem for Churchill as he became Prime Minister was that he was not the leader of the majority Conservative Party and, needing its support, was obliged to include Chamberlain in the war cabinet, but this was not to Labour's liking. Initially, Churchill proposed to appoint Chamberlain as both Leader of the House of Commons

The leader of the House of Commons is a minister of the Crown of the Government of the United Kingdom whose main role is organising government business in the House of Commons. The leader is generally a member or attendee of the cabinet of t ...

and Chancellor of the Exchequer

The chancellor of the Exchequer, often abbreviated to chancellor, is a senior minister of the Crown within the Government of the United Kingdom, and head of HM Treasury, His Majesty's Treasury. As one of the four Great Offices of State, the Ch ...

. Attlee objected and Churchill decided to appoint Chamberlain as Lord President of the Council

The lord president of the Council is the presiding officer of the Privy Council of the United Kingdom and the fourth of the Great Officers of State, ranking below the Lord High Treasurer but above the Lord Keeper of the Privy Seal. The Lord ...

. The fifth member of the war cabinet was Halifax, who retained his position as Foreign Secretary

The secretary of state for foreign, Commonwealth and development affairs, known as the foreign secretary, is a Secretary of State (United Kingdom), minister of the Crown of the Government of the United Kingdom and head of the Foreign, Commonwe ...

. Instead of Chamberlain, Sir Kingsley Wood became Chancellor but, until 3 October 1940, he was not a member of the war cabinet.

Churchill appointed himself as Leader of the House of Commons (it was normal procedure until 1942 for a prime minister in the Commons to lead the House) and created for himself the new role of Minister of Defence

A defence minister or minister of defence is a cabinet official position in charge of a ministry of defense, which regulates the armed forces in sovereign states. The role of a defence minister varies considerably from country to country; in som ...

, so that he would be permanent chair of the Cabinet Defence Committee (CDC), Operations, which included the three service ministers, the three Chiefs of Staff

The title chief of staff (or head of staff) identifies the leader of a complex organization such as the armed forces, institution, or body of persons and it also may identify a principal staff officer (PSO), who is the coordinator of the supporti ...

(CoS) and other ministers, especially Attlee, and experts as and when required.Anthony Eden

Robert Anthony Eden, 1st Earl of Avon, (12 June 1897 – 14 January 1977) was a British Conservative Party politician who served as Prime Minister of the United Kingdom from 1955 until his resignation in 1957.

Achieving rapid promo ...

became Secretary of State for War

The Secretary of State for War, commonly called War Secretary, was a secretary of state in the Government of the United Kingdom, which existed from 1794 to 1801 and from 1854 to 1964. The Secretary of State for War headed the War Office and ...

(until December 1940); Labour's A. V. Alexander

Albert Victor Alexander, 1st Earl Alexander of Hillsborough, (1 May 1885 – 11 January 1965), was a British Labour and Co-operative politician. He was three times First Lord of the Admiralty, including during the Second World War, and then M ...

succeeded Churchill as First Lord of the Admiralty

The First Lord of the Admiralty, or formally the Office of the First Lord of the Admiralty, was the political head of the English and later British Royal Navy. He was the government's senior adviser on all naval affairs, responsible for the di ...

; and the Liberal Party

The Liberal Party is any of many political parties around the world. The meaning of ''liberal'' varies around the world, ranging from liberal conservatism on the right to social liberalism on the left.

__TOC__ Active liberal parties

This is a li ...

leader, Sir Archibald Sinclair, became Secretary of State for Air

The Secretary of State for Air was a secretary of state position in the British government, which existed from 1919 to 1964. The person holding this position was in charge of the Air Ministry. The Secretary of State for Air was supported by ...

. The CoS at this time were Admiral Sir Dudley Pound, the First Sea Lord

The First Sea Lord and Chief of the Naval Staff (1SL/CNS) is the military head of the Royal Navy and Naval Service of the United Kingdom. The First Sea Lord is usually the highest ranking and most senior admiral to serve in the British Armed Fo ...

; Air Marshal Sir Cyril Newall, the Chief of the Air Staff; and Field Marshal Sir Edmund Ironside, the Chief of the Imperial General Staff

The Chief of the General Staff (CGS) has been the title of the professional head of the British Army since 1964. The CGS is a member of both the Chiefs of Staff Committee and the Army Board. Prior to 1964, the title was Chief of the Imperial G ...

(CIGS). (On 27 May, Ironside was replaced at Churchill's request by his deputy Field Marshal Sir John Dill, and Ironside became Commander-in-Chief, Home Forces.) The CoS continued to hold their own Chiefs of Staff Committee

The Chiefs of Staff Committee (CSC) is composed of the most senior military personnel in the British Armed Forces who advise on operational military matters and the preparation and conduct of military operations. The committee consists of the ...

(CSC) meetings. The CDC enabled Churchill to have direct contact with them so that strategic concerns could be addressed with due regard to civil matters and foreign affairs.

In addition, for the ministry's whole term, both the war cabinet and the CDC were regularly attended by Sir Edward Bridges, the Cabinet Secretary; General Sir Hastings Ismay, Chief of Staff to the Minister of Defence; and Major General Sir Leslie Hollis, Secretary to the Chiefs of Staff Committee. Bridges was rarely absent from war cabinet sessions. He was appointed by Chamberlain – as a senior civil servant, he was not a political appointee – in August 1938 and remained ''in situ'' until 1946. Churchill later described Bridges as "an extremely competent and tireless worker". Ismay's role, technically, was Secretary of the CSC but he was in fact Churchill's chief staff officer and military adviser throughout the war. Hollis was Secretary to the CoS Committee, also for the duration, and he additionally served as senior assistant secretary to Bridges in the war cabinet office.

13 May – Churchill's first speech as Prime Minister

By Monday, 13 May, most of the senior government posts were filled. That day was Whit Monday

Whit Monday or Pentecost Monday, also known as Monday of the Holy Spirit, is the holiday celebrated the day after Pentecost, a moveable feast in the Christian liturgical calendar. It is moveable because it is determined by the date of Easter. I ...

, normally a bank holiday

A bank holiday is a national public holiday in the United Kingdom, Republic of Ireland and the Crown Dependencies. The term refers to all public holidays in the United Kingdom, be they set out in statute, declared by royal proclamation or h ...

but cancelled by the incoming government. A specially convened sitting of the House of Commons was held and Churchill spoke for the first time as Prime Minister:Hastings Lees-Smith

Hastings Bertrand Lees-Smith PC (26 January 1878 – 18 December 1941) was a British Liberal turned Labour politician who was briefly in the cabinet as President of the Board of Education in 1931. He was the acting Leader of the Opposition and ...

as acting Leader of the Opposition announced that Labour would vote for the motion to assure the country of a unified political front.David Lloyd George

David Lloyd George, 1st Earl Lloyd-George of Dwyfor, (17 January 1863 – 26 March 1945) was Prime Minister of the United Kingdom from 1916 to 1922. He was a Liberal Party (United Kingdom), Liberal Party politician from Wales, known for lea ...

and Stafford Cripps

Sir Richard Stafford Cripps (24 April 1889 – 21 April 1952) was a British Labour Party politician, barrister, and diplomat.

A wealthy lawyer by background, he first entered Parliament at a by-election in 1931, and was one of a handful of La ...

, the House divided on the question: "That this House welcomes the formation of a Government representing the united and inflexible resolve of the nation to prosecute the war with Germany to a victorious conclusion". 381 members voted "aye" in favour of the motion and, apart from the two tellers for the "noes", the wartime coalition was endorsed unanimously.

14–17 May – Completion of government membership

Apart from a handful of junior appointments such as royal household positions, Churchill completed the construction of his government by the end of his first week in office. Only two women were appointed to government positions – Florence Horsbrugh, who had previously been a Conservative backbench MP, became Parliamentary Secretary to the Ministry of Health on 15 May; and Labour's Ellen Wilkinson, the most left-wing member of Churchill's ministry, became Parliamentary Secretary to the Ministry of Pensions The Parliamentary Secretary to the Ministry of Pensions was a junior Ministerial office at Parliamentary Secretary rank in the British Government, supporting the Minister for Pensions.

Establishment and history

The office was established in 1916 ...

on the 17th.

18 May to 4 June – War cabinet crisis

The war situation in Europe became increasingly critical for the Allies as the Wehrmacht overran northern France and the Low Countries through May, culminating in the siege of Dunkirk

Dunkirk (french: Dunkerque ; vls, label=French Flemish, Duunkerke; nl, Duinkerke(n) ; , ;) is a commune in the department of Nord in northern France. and the desperate need to evacuate the British Expeditionary Force by Operation Dynamo. In the war cabinet, Churchill faced a serious challenge by Halifax to his direction of the war. Halifax wanted to sue for peace by asking Mussolini

Benito Amilcare Andrea Mussolini (; 29 July 188328 April 1945) was an Italian politician and journalist who founded and led the National Fascist Party. He was Prime Minister of Italy from the March on Rome in 1922 until Fall of the Fascist re ...

to broker a treaty between the British government and Hitler. Churchill wanted to continue the war. Attlee and Greenwood supported Churchill while Chamberlain, still the leader of the majority Conservative Parliamentary Party, remained neutral for several days until finally aligning himself with Churchill's resolve to fight on.

5 June 1940 to 30 April 1941

* 2 August 1940: Lord Beaverbrook

William Maxwell Aitken, 1st Baron Beaverbrook (25 May 1879 – 9 June 1964), generally known as Lord Beaverbrook, was a Canadian-British newspaper publisher and backstage politician who was an influential figure in British media and politics o ...

, Minister of Aircraft Production

The Minister of Aircraft Production was, from 1940 to 1945, the British government minister at the Ministry of Aircraft Production, one of the specialised supply ministries set up by the British Government during World War II. It was responsible ...

, joined the war cabinet.

* 22 September 1940: resignation of Neville Chamberlain for health reasons (terminal colon cancer).

* 3 October 1940: Sir John Anderson succeeded Chamberlain as Lord President and joined the war cabinet. Sir Kingsley Wood, the Chancellor of the Exchequer

The chancellor of the Exchequer, often abbreviated to chancellor, is a senior minister of the Crown within the Government of the United Kingdom, and head of HM Treasury, His Majesty's Treasury. As one of the four Great Offices of State, the Ch ...

, and Ernest Bevin

Ernest Bevin (9 March 1881 – 14 April 1951) was a British statesman, trade union leader, and Labour Party (UK), Labour Party politician. He co-founded and served as General Secretary of the powerful Transport and General Workers' Union in th ...

, the Minister of Labour, also entered the war cabinet. Lord Halifax assumed the additional job of Leader of the House of Lords

The leader of the House of Lords is a member of the Cabinet of the United Kingdom who is responsible for arranging government business in the House of Lords. The post is also the leader of the majority party in the House of Lords who acts as ...

.

* 25 October 1940: Air Marshal Sir Cyril Newall was persuaded to take retirement and was replaced by Sir Charles Portal

Marshal of the Royal Air Force Charles Frederick Algernon Portal, 1st Viscount Portal of Hungerford, (21 May 1893 – 22 April 1971) was a senior Royal Air Force officer. He served as a bomber pilot in the First World War, and rose to become fi ...

, who had been C-in-C of Bomber Command.

* 9 November 1940: death of Neville Chamberlain.

* 22 December 1940: Anthony Eden

Robert Anthony Eden, 1st Earl of Avon, (12 June 1897 – 14 January 1977) was a British Conservative Party politician who served as Prime Minister of the United Kingdom from 1955 until his resignation in 1957.

Achieving rapid promo ...

succeeded Lord Halifax as Foreign Secretary (Eden held the post until 26 July 1945) and joined the war cabinet as its eighth member. Halifax became Ambassador to the United States. His successor as Leader of the House of Lords was not in the war cabinet.

* 30 April 1941: Beaverbrook ceased to be Minister of Aircraft Production, but remained in the war cabinet as Minister of State

Minister of State is a title borne by politicians in certain countries governed under a parliamentary system. In some countries a Minister of State is a Junior Minister of government, who is assigned to assist a specific Cabinet Minister. I ...

(appointed 1 May 1941). His successor was not in the war cabinet.

1 May 1941 to 30 April 1942

* 29 June 1941: Beaverbrook became

* 29 June 1941: Beaverbrook became Minister of Supply

The Minister of Supply was the minister in the British Government responsible for the Ministry of Supply, which existed to co-ordinate the supply of equipment to the national armed forces. The position was campaigned for by many sceptics of the for ...

, remaining in the war cabinet. Oliver Lyttelton

Oliver Lyttelton, 1st Viscount Chandos, (15 March 1893 – 21 January 1972) was a British businessman from the Lyttelton family who was brought into government during the Second World War, holding a number of ministerial posts.

Background, ed ...

entered the war cabinet as Minister-Resident for the Middle East The Minister-Resident for the Middle East was a British Government cabinet position for most of the duration of World War II.

The position was created in 1941 and the holder was made a member of the war cabinet. The minister served as the overall e ...

.

* 25 December 1941: Sir John Dill was replaced as CIGS by Field Marshal Sir Alan Brooke. Dill became Chief of the British Joint Staff Mission in Washington, DC. Brooke had been General Ironside's successor as C-in-C, Home Forces, since July 1940.

* 4 February 1942: Beaverbrook resigned from Supply and was appointed Minister of War Production; his successor as Minister of Supply was not in the war cabinet.

* 15 February 1942: Attlee relinquished the Lord Privy Seal

The Lord Privy Seal (or, more formally, the Lord Keeper of the Privy Seal) is the fifth of the Great Officers of State in the United Kingdom, ranking beneath the Lord President of the Council and above the Lord Great Chamberlain. Originally, ...

to become Secretary of State for Dominion Affairs

The position of Secretary of State for Dominion Affairs was a British cabinet-level position created in 1925 responsible for British relations with the Dominions – Canada, Australia, New Zealand, South Africa, Newfoundland, and the Irish Free S ...

, the first time this office was represented in the war cabinet.

* 19 February 1942: Attlee was appointed Deputy Prime Minister

A deputy prime minister or vice prime minister is, in some countries, a government minister who can take the position of acting prime minister when the prime minister is temporarily absent. The position is often likened to that of a vice president, ...

with general responsibility for domestic affairs. Beaverbrook again resigned but no replacement as Minister of War Production was appointed for the moment. Sir Stafford Cripps

Sir Richard Stafford Cripps (24 April 1889 – 21 April 1952) was a British Labour Party politician, barrister, and diplomat.

A wealthy lawyer by background, he first entered Parliament at a by-election in 1931, and was one of a handful of La ...

succeeded Attlee as Lord Privy Seal and took over the position of Leader of the House of Commons

The leader of the House of Commons is a minister of the Crown of the Government of the United Kingdom whose main role is organising government business in the House of Commons. The leader is generally a member or attendee of the cabinet of t ...

to reduce Churchill's workload. Sir Kingsley Wood left the war cabinet, though remaining Chancellor of the Exchequer.

* 22 February 1942: Arthur Greenwood left the war cabinet to assume the role of Leader of the Opposition, necessary for House of Commons functionality, till 23 May 1945.

* 12 March 1942: Oliver Lyttelton filled the vacant position of Minister of Production

The Minister of Production was a British government position that existed during the Second World War, heading the Ministry of Production.

Initially the post was called "Minister of War Production" when it was created in February 1942, but the fir ...

("War" was dropped from the title). Richard Casey succeeded Oliver Lyttelton as Minister-Resident for the Middle East The Minister-Resident for the Middle East was a British Government cabinet position for most of the duration of World War II.

The position was created in 1941 and the holder was made a member of the war cabinet. The minister served as the overall e ...

.

1 May 1942 to 30 April 1943

* 22 November 1942: Sir Stafford Cripps retired as Lord Privy Seal and Leader of the House of Commons and left the war cabinet. His successor as Lord Privy Seal (Viscount Cranborne

A viscount ( , for male) or viscountess (, for female) is a title used in certain European countries for a noble of varying status.

In many countries a viscount, and its historical equivalents, was a non-hereditary, administrative or judicial ...

) was not in the Cabinet, Anthony Eden took the additional position of Leader of the House of Commons. The Home Secretary

The secretary of state for the Home Department, otherwise known as the home secretary, is a senior minister of the Crown in the Government of the United Kingdom. The home secretary leads the Home Office, and is responsible for all nationa ...

, Herbert Morrison

Herbert Stanley Morrison, Baron Morrison of Lambeth, (3 January 1888 – 6 March 1965) was a British politician who held a variety of senior positions in the UK Cabinet as member of the Labour Party. During the inter-war period, he was Minis ...

, entered the Cabinet.

1 May 1943 to 30 April 1944

* 21 September 1943: Death of Sir Kingsley Wood.

* 24 September 1943: Anderson succeeded Wood as Chancellor of the Exchequer, remaining in the war cabinet.

* 24 September 1943: Attlee left Dominions to succeed Anderson as Lord President. Except during Attlee's tenure, Dominions was not a war cabinet portfolio. Attlee remained Deputy PM and Lord President until termination of the ministry on 23 May 1945.

* 15 October 1943: Due to failing health, Sir Dudley Pound had to resign as First Sea Lord. He died six days later. He was succeeded by Admiral of the Fleet Sir Andrew Cunningham, who had been Commander-in-Chief of the Mediterranean Fleet

The British Mediterranean Fleet, also known as the Mediterranean Station, was a formation of the Royal Navy. The Fleet was one of the most prestigious commands in the navy for the majority of its history, defending the vital sea link between t ...

.

* 11 November 1943: Lord Woolton joined the war cabinet as Minister of Reconstruction.

* 14 January 1944: Lord Moyne

Walter Edward Guinness, 1st Baron Moyne, DSO & Bar, PC (29 March 1880 – 6 November 1944), was an Anglo-Irish politician and businessman. He served as the British minister of state in the Middle East until November 1944, when he was assass ...

replaced Richard Casey as Minister-Resident for the Middle East.

1 May 1944 to 22 May 1945

* 6 June 1944: D-Day

The Normandy landings were the landing operations and associated airborne operations on Tuesday, 6 June 1944 of the Allied invasion of Normandy in Operation Overlord during World War II. Codenamed Operation Neptune and often referred to as ...

.

* 6 November 1944: Lord Moyne was assassinated in Cairo by Jewish militants. His successor was not in the war cabinet.

* 25 April 1945: Attlee, Eden, Florence Horsbrugh and Ellen Wilkinson were Britain's delegates at the San Francisco Conference.

* 30 April 1945: Death of Hitler.

* 8 May 1945: VE Day

Victory in Europe Day is the day celebrating the formal acceptance by the Allies of World War II of Germany's unconditional surrender of its armed forces on Tuesday, 8 May 1945, marking the official end of World War II in Europe in the Easter ...

. The war cabinet members then were Churchill, Attlee, Anderson, Bevin, Eden, Lyttelton, Morrison and Woolton.

23 May 1945 – End of the ministry

In October 1944, Churchill had proposed to the Commons that the current Parliament, which had begun in 1935, should be extended by a further year. He correctly anticipated the defeat of Germany in the spring of 1945 but he did not expect the end of the Far East war until 1946. He therefore recommended that the end of the European war should be "a pointer (to) fix the date of the (next) General Election".

Attlee, along with Eden, Horsbrugh and Wilkinson, attended the San Francisco Conference and had returned to London by 18 May 1945 (ten days after V-E Day

Victory in Europe Day is the day celebrating the formal acceptance by the Allies of World War II of Germany's unconditional surrender of its armed forces on Tuesday, 8 May 1945, marking the official end of World War II in Europe in the Easte ...

) when he met Churchill to discuss the future of the coalition. Attlee, in agreement with Churchill, wanted it to continue until after the Japanese surrender but he discovered that others in the Labour Party, especially Morrison and Bevin, wanted an election in October after Parliament ended. On 20 May, Attlee attended his party conference and found that opinion was against him so he informed Churchill that Labour must leave the coalition.

On 23 May, Labour left the coalition to begin their general election campaign. Churchill resigned as prime minister but the King asked him to form a new government, known as the Churchill caretaker ministry, until the election was held in July. Churchill agreed and his new ministry, essentially a Conservative one, held office for the next two months until it was replaced by Attlee's Labour government after their election victory.

Government members

Ministers who held war cabinet membership, 10 May 1940 – 23 May 1945

A total of sixteen ministers held war cabinet membership at various times in Churchill's ministry. There were five at the outset of whom two, Churchill and Attlee, served throughout the ministry's entire term. Bevin, Morrison and Wood were appointed to the war cabinet while retaining offices that had originally been outer cabinet portfolios. Anderson and Eden were promoted to the war cabinet from other offices after their predecessors, Chamberlain and Halifax, had left the government; similarly, Casey was brought in after Lyttelton switched portfolio and Moyne was appointed to replace Casey. Beaverbrook, Lyttelton and Woolton were brought in to fill new offices that were created to address current priorities. Greenwood was an original member with no portfolio and was not replaced when he assumed the acting leadership of the Opposition. Cripps was brought in as an extra member to reduce the workloads of Churchill and Attlee.

Senior government ministries and offices, 10 May 1940 – 23 May 1945

This table lists cabinet level ministries and offices during the Churchill administration. Most of these were portfolios in the "outer cabinet" and outside the war cabinet, although some were ''temporarily'' included in the war cabinet, as indicated by bold highlighting of the ministers concerned. Focus here is upon the ministerial offices. Some ministries, such as Foreign Secretary, were in the war cabinet throughout the entire administration whereas others like Lord Privy Seal, Chancellor of the Exchequer and Home Secretary were sometimes in the war cabinet and sometimes not, depending on priorities at the time. A number of ministries were created by Churchill in response to wartime needs. Some of the ministers retained offices that they held in former administrations and their notes include the date of their original appointment. For new appointments to existing offices, their predecessor's name is given.

Financial and parliamentary secretaries, 10 May 1940 – 23 May 1945

This table lists the junior offices (often ministerial level 3) that held the title of Financial Secretary and/or Parliamentary Secretary. None of these officials were ever in the war cabinet. Their offices have rarely, if ever, been recognised as cabinet-level, although some of the office holders here did, at need, occasionally attend cabinet meetings. Some of the appointees retained offices that they held in former administrations and these are marked ''in situ'' with the date of their original appointment.

Other junior ministries, 10 May 1940 – 23 May 1945

This table lists the junior offices (often ministerial level 3) whose titles signify an assistant, deputy or under-secretary function. It excludes financial and parliamentary secretaries who are in the table above. None of these officials were ever in the war cabinet. Their offices have rarely, if ever, been recognised as cabinet-level, although some of the office holders here did, at need, occasionally attend cabinet meetings. Some of the appointees retained offices that they held in former administrations and these are marked ''in situ'' with the date of their original appointment.

Royal household appointments, 10 May 1940 – 23 May 1945

This table lists the officers appointed to the royal household during the Churchill administration.

See also

* Allied leaders of World War II

* Timeline of the first premiership of Winston Churchill

* Winston Churchill in the Second World War

Winston Churchill was appointed First Lord of the Admiralty on 3 September 1939, the day that the United Kingdom declared war on Nazi Germany. He succeeded Neville Chamberlain as prime minister on 10 May 1940 and held the post until 26 July ...

References

Bibliography

*

*

*

*

*

*

*

*

*

*

*

*

*

*

External links

*

*

*

{{British ministries

1940 establishments in the United Kingdom

1940s in the United Kingdom

1945 disestablishments in the United Kingdom

British ministries

Cabinets disestablished in 1945

Cabinets established in 1940

Coalition governments of the United Kingdom

Grand coalition governments

History of the Labour Party (UK)

Politics of World War II

United Kingdom in World War II-related lists

United Kingdom in World War II

Ministry 1

The 1935 general election had resulted in a Conservative victory with a substantial majority and

The 1935 general election had resulted in a Conservative victory with a substantial majority and  After Attlee and Greenwood left, Chamberlain asked whom he should recommend to the King as his successor. The version of events given by Churchill is that Chamberlain's preference for Halifax was obvious (Churchill implies that the spat between Churchill and the Labour benches the previous night had something to do with that); there was a long silence which Halifax eventually broke by saying he did not believe he could lead the government effectively as a member of the

After Attlee and Greenwood left, Chamberlain asked whom he should recommend to the King as his successor. The version of events given by Churchill is that Chamberlain's preference for Halifax was obvious (Churchill implies that the spat between Churchill and the Labour benches the previous night had something to do with that); there was a long silence which Halifax eventually broke by saying he did not believe he could lead the government effectively as a member of the

On Saturday, 11 May, the Labour Party agreed to join a national government under Churchill's leadership and he was able to confirm his war cabinet. In his biography of Churchill,

On Saturday, 11 May, the Labour Party agreed to join a national government under Churchill's leadership and he was able to confirm his war cabinet. In his biography of Churchill,  * 29 June 1941: Beaverbrook became

* 29 June 1941: Beaverbrook became