Christopher Marlow on:

[Wikipedia]

[Google]

[Amazon]

Christopher Marlowe, also known as Kit Marlowe (;

Marlowe is alleged to have been a government spy.

Marlowe is alleged to have been a government spy.  It has been speculated that Marlowe was the "Morley" who was tutor to

It has been speculated that Marlowe was the "Morley" who was tutor to

Marlowe was reputed to be an atheist, which held the dangerous implication of being an enemy of God and the state, by association. With the rise of public fears concerning The School of Night, or "School of Atheism" in the late 16th century, accusations of atheism were closely associated with disloyalty to the Protestant monarchy of England.

Some modern historians consider that Marlowe's professed atheism, as with his supposed Catholicism, may have been no more than a sham to further his work as a government spy. Contemporary evidence comes from Marlowe's accuser in

Marlowe was reputed to be an atheist, which held the dangerous implication of being an enemy of God and the state, by association. With the rise of public fears concerning The School of Night, or "School of Atheism" in the late 16th century, accusations of atheism were closely associated with disloyalty to the Protestant monarchy of England.

Some modern historians consider that Marlowe's professed atheism, as with his supposed Catholicism, may have been no more than a sham to further his work as a government spy. Contemporary evidence comes from Marlowe's accuser in  Similar examples of Marlowe's statements were given by

Similar examples of Marlowe's statements were given by

It has been claimed that Marlowe was homosexual. Some scholars argue that the identification of an Elizabethan as gay or homosexual in the modern sense is "

It has been claimed that Marlowe was homosexual. Some scholars argue that the identification of an Elizabethan as gay or homosexual in the modern sense is "

In early May 1593, several bills were posted about London threatening Protestant refugees from France and the Netherlands who had settled in the city. One of these, the "Dutch church libel", written in rhymed

In early May 1593, several bills were posted about London threatening Protestant refugees from France and the Netherlands who had settled in the city. One of these, the "Dutch church libel", written in rhymed

Peter Farey's Marlowe page

(Retrieved 30 April 2015). In a second letter, Kyd described Marlowe as blasphemous, disorderly, holding treasonous opinions, being an irreligious reprobate and "intemperate & of a cruel hart". They had both been working for an

"Thomas Kyd."

' Various accounts of Marlowe's death were current over the next few years. In his ''

Various accounts of Marlowe's death were current over the next few years. In his ''

First official record 1594

First published 1594; posthumously

First recorded performance between 1587 and 1593 by the

First official record 1594

First published 1594; posthumously

First recorded performance between 1587 and 1593 by the

First official record 1587, Part I

First published 1590, Parts I and II in one

First official record 1587, Part I

First published 1590, Parts I and II in one

First official record 1592

First published 1592; earliest extant edition, 1633

First recorded performance 26 February 1592, by Lord Strange's acting company.

Significance The performances of the play were a success and it remained popular for the next fifty years. This play helps to establish the strong theme of "anti-authoritarianism" that is found throughout Marlowe's works.

Evidence No manuscripts by Marlowe exist for this play. The play was entered in the Stationers' Register on 17 May 1594 but the earliest surviving printed edition is from 1633.

First official record 1592

First published 1592; earliest extant edition, 1633

First recorded performance 26 February 1592, by Lord Strange's acting company.

Significance The performances of the play were a success and it remained popular for the next fifty years. This play helps to establish the strong theme of "anti-authoritarianism" that is found throughout Marlowe's works.

Evidence No manuscripts by Marlowe exist for this play. The play was entered in the Stationers' Register on 17 May 1594 but the earliest surviving printed edition is from 1633.

First official record 1594–1597

First published 1601, no extant copy; first extant copy, 1604 (A text)

First official record 1594–1597

First published 1601, no extant copy; first extant copy, 1604 (A text)

First official record 1593

First published 1590; earliest extant edition 1594

First official record 1593

First published 1590; earliest extant edition 1594

Via Google Books

** ** ** ** ** ** ** ** * * * * * * * * * *

The Marlowe Society

The works of Marlowe at Perseus Project

The complete works

, with modernised spelling, on Peter Farey's Marlowe page.

BBC audio file

'' In Our Time'' Radio 4 discussion programme on Marlowe and his work * Th

Marlowe Bibliography Online

is an initiative of th

Marlowe Society of America

and th

University of Melbourne

Its purpose is to facilitate scholarship on the works of Christopher Marlowe by providing a searchable annotated bibliography of relevant scholarship * {{DEFAULTSORT:Marlowe, Christopher 1564 births 1593 crimes 1593 deaths 16th-century English dramatists and playwrights 16th-century English poets 16th-century spies Pre–17th-century atheists 16th-century translators Alumni of Corpus Christi College, Cambridge Deaths by stabbing in England English male dramatists and playwrights English male poets English murder victims English Renaissance dramatists English spies People educated at The King's School, Canterbury People from Canterbury People murdered in England People of the Elizabethan era University Wits Latin–English translators

baptised

Baptism (from grc-x-koine, βάπτισμα, váptisma) is a form of ritual purification—a characteristic of many religions throughout time and geography. In Christianity, it is a Christian sacrament of initiation and adoption, almost inv ...

26 February 156430 May 1593), was an English playwright, poet

A poet is a person who studies and creates poetry. Poets may describe themselves as such or be described as such by others. A poet may simply be the creator ( thinker, songwriter, writer, or author) who creates (composes) poems ( oral or wri ...

and translator

Translation is the communication of the meaning of a source-language text by means of an equivalent target-language text. The English language draws a terminological distinction (which does not exist in every language) between ''transl ...

of the Elizabethan era

The Elizabethan era is the epoch in the Tudor period of the history of England during the reign of Queen Elizabeth I (1558–1603). Historians often depict it as the golden age in English history. The symbol of Britannia (a female personific ...

. Marlowe is among the most famous of the Elizabethan playwrights. Based upon the "many imitations" of his play ''Tamburlaine

''Tamburlaine the Great'' is a play in two parts by Christopher Marlowe. It is loosely based on the life of the Central Asian emperor Timur (Tamerlane/Timur the Lame, d. 1405). Written in 1587 or 1588, the play is a milestone in Elizabethan p ...

,'' modern scholar

A scholar is a person who pursues academic and intellectual activities, particularly academics who apply their intellectualism into expertise in an area of study. A scholar can also be an academic, who works as a professor, teacher, or researc ...

s consider him to have been the foremost dramatist

A playwright or dramatist is a person who writes plays.

Etymology

The word "play" is from Middle English pleye, from Old English plæġ, pleġa, plæġa ("play, exercise; sport, game; drama, applause"). The word "wright" is an archaic English ...

in London

London is the capital and List of urban areas in the United Kingdom, largest city of England and the United Kingdom, with a population of just under 9 million. It stands on the River Thames in south-east England at the head of a estuary dow ...

in the years just before his mysterious early death. Some scholars also believe that he greatly influenced William Shakespeare

William Shakespeare ( 26 April 1564 – 23 April 1616) was an English playwright, poet and actor. He is widely regarded as the greatest writer in the English language and the world's pre-eminent dramatist. He is often called England's nation ...

, who was baptised

Baptism (from grc-x-koine, βάπτισμα, váptisma) is a form of ritual purification—a characteristic of many religions throughout time and geography. In Christianity, it is a Christian sacrament of initiation and adoption, almost inv ...

in the same year as Marlowe and later succeeded him as the pre-eminent Elizabethan playwright. Marlowe was the first to achieve critical reputation for his use of blank verse

Blank verse is poetry written with regular metrical but unrhymed lines, almost always in iambic pentameter. It has been described as "probably the most common and influential form that English poetry has taken since the 16th century", and Pa ...

, which became the standard for the era. His plays are distinguished by their overreaching protagonists. Themes found within Marlowe's literary

Literature is any collection of written work, but it is also used more narrowly for writings specifically considered to be an art form, especially prose fiction, drama, and poetry. In recent centuries, the definition has expanded to include ...

works have been noted as humanistic with realistic emotions, which some scholars find difficult to reconcile with Marlowe's "anti-intellectualism

Anti-intellectualism is hostility to and mistrust of intellect, intellectuals, and intellectualism, commonly expressed as deprecation of education and philosophy and the dismissal of art, literature, and science as impractical, politically ...

" and his catering to the prurient tastes of his Elizabethan audiences for generous displays of extreme physical violence, cruelty, and bloodshed.

Events in Marlowe's life were sometimes as extreme as those found in his plays. Differing sensational reports of Marlowe's death in 1593 abounded after the event and are contested by scholars today owing to a lack of good documentation. There have been many conjectures

In mathematics, a conjecture is a conclusion or a proposition that is proffered on a tentative basis without proof. Some conjectures, such as the Riemann hypothesis (still a conjecture) or Fermat's Last Theorem (a conjecture until proven in ...

as to the nature and reason for his death, including a vicious bar-room fight, blasphemous libel against the church, homosexual intrigue, betrayal by another playwright, and espionage

Espionage, spying, or intelligence gathering is the act of obtaining secret or confidential information (intelligence) from non-disclosed sources or divulging of the same without the permission of the holder of the information for a tangib ...

from the highest level: the Privy Council of Elizabeth I

Elizabeth I (7 September 153324 March 1603) was List of English monarchs, Queen of England and List of Irish monarchs, Ireland from 17 November 1558 until her death in 1603. Elizabeth was the last of the five House of Tudor monarchs and is ...

. An official coroner's account of Marlowe's death was revealed only in 1925, and it did little to persuade all scholars that it told the whole story, nor did it eliminate the uncertainties present in his biography

A biography, or simply bio, is a detailed description of a person's life. It involves more than just the basic facts like education, work, relationships, and death; it portrays a person's experience of these life events. Unlike a profile or ...

.

Early life

Christopher Marlowe, the second of nine children, and oldest child after the death of his sister Mary in 1568, was born toCanterbury

Canterbury (, ) is a cathedral city and UNESCO World Heritage Site, situated in the heart of the City of Canterbury local government district of Kent, England. It lies on the River Stour.

The Archbishop of Canterbury is the primate of ...

shoemaker John Marlowe and his wife Katherine, daughter of William Arthur of Dover. He was baptised at St George's Church, Canterbury, on 26 February 1564 (1563 in the old style dates in use at the time, which placed the new year on 25 March). Marlowe's birth was likely to have been a few days before, making him about two months older than William Shakespeare

William Shakespeare ( 26 April 1564 – 23 April 1616) was an English playwright, poet and actor. He is widely regarded as the greatest writer in the English language and the world's pre-eminent dramatist. He is often called England's nation ...

, who was baptised on 26 April 1564 in Stratford-upon-Avon.

By age 14, Marlowe was a pupil at The King's School, Canterbury on a scholarship and two years later a student at Corpus Christi College, Cambridge, where he also studied through a scholarship and received his Bachelor of Arts degree in 1584. Marlowe mastered Latin

Latin (, or , ) is a classical language belonging to the Italic branch of the Indo-European languages. Latin was originally a dialect spoken in the lower Tiber area (then known as Latium) around present-day Rome, but through the power of the ...

during his schooling, reading and translating the works of Ovid

Pūblius Ovidius Nāsō (; 20 March 43 BC – 17/18 AD), known in English as Ovid ( ), was a Roman poet who lived during the reign of Augustus. He was a contemporary of the older Virgil and Horace, with whom he is often ranked as one of the th ...

. In 1587, the university hesitated to award his Master of Arts degree because of a rumour that he intended to go to the English seminary at Rheims

Reims ( , , ; also spelled Rheims in English) is the most populous city in the French department of Marne, and the 12th most populous city in France. The city lies northeast of Paris on the Vesle river, a tributary of the Aisne.

Founded by ...

in northern France

France (), officially the French Republic ( ), is a country primarily located in Western Europe. It also comprises of overseas regions and territories in the Americas and the Atlantic, Pacific and Indian Oceans. Its metropolitan area ...

, presumably to prepare for ordination as a Roman Catholic

Roman or Romans most often refers to:

*Rome, the capital city of Italy

* Ancient Rome, Roman civilization from 8th century BC to 5th century AD

* Roman people, the people of ancient Rome

*'' Epistle to the Romans'', shortened to ''Romans'', a let ...

priest. If true, such an action on his part would have been a direct violation of royal edict issued by Queen Elizabeth I

Elizabeth I (7 September 153324 March 1603) was Queen of England and Ireland from 17 November 1558 until her death in 1603. Elizabeth was the last of the five House of Tudor monarchs and is sometimes referred to as the "Virgin Queen".

El ...

in 1585 criminalising any attempt by an English citizen to be ordained in the Roman Catholic Church.

Large-scale violence between Protestants and Catholics on the European continent has been cited by scholars as the impetus for the Protestant English Queen's defensive anti-Catholic laws issued from 1581 until her death in 1603. Despite the dire implications for Marlowe, his degree was awarded on schedule when the Privy Council intervened on his behalf, commending him for his "faithful dealing" and "good service" to the Queen

In the English-speaking world, The Queen most commonly refers to:

* Elizabeth II (1926–2022), Queen of the United Kingdom and other Commonwealth realms from 1952 until her death

The Queen may also refer to:

* Camilla, Queen Consort (born 1947), ...

. The nature of Marlowe's service was not specified by the Council, but its letter to the Cambridge authorities has provoked much speculation by modern scholars, notably the theory that Marlowe was operating as a secret agent for Privy Council member Sir Francis Walsingham

Sir Francis Walsingham ( – 6 April 1590) was principal secretary to Queen Elizabeth I of England from 20 December 1573 until his death and is popularly remembered as her "spymaster".

Born to a well-connected family of gentry, Wals ...

. The only surviving evidence of the Privy Council's correspondence is found in their minutes, the letter being lost. There is no mention of espionage

Espionage, spying, or intelligence gathering is the act of obtaining secret or confidential information (intelligence) from non-disclosed sources or divulging of the same without the permission of the holder of the information for a tangib ...

in the minutes, but its summation of the lost Privy Council letter is vague in meaning, stating that "it was not Her Majesties pleasure" that persons employed as Marlowe had been "in matters touching the benefit of his country should be defamed by those who are ignorant in th'affaires he went about." Scholars agree the vague wording was typically used to protect government agents, but they continue to debate what the "matters touching the benefit of his country" actually were in Marlowe's case and how they affected the 23-year-old writer as he launched his literary career in 1587.

Adult life and legend

Little is known about Marlowe's adult life. All available evidence, other than what can be deduced from his literary works, is found in legal records and other official documents. Writers of fiction and non-fiction have speculated about his professional activities, private life, and character. Marlowe has been described as a spy, a brawler, and a heretic, as well as a "magician", "duellist", "tobacco-user", "counterfeiter" and "rakehell

In a historical context, a rake (short for rakehell, analogous to "hellraiser") was a man who was habituated to immoral conduct, particularly womanizing. Often, a rake was also prodigal, wasting his (usually inherited) fortune on gambling, ...

". While J. A. Downie and Constance Kuriyama have argued against the more lurid speculations, it is the usually circumspect J. B. Steane who remarked, "it seems absurd to dismiss all of these Elizabethan rumours and accusations as 'the Marlowe myth. Much has been written on his brief adult life, including speculation of: his involvement in royally-sanctioned espionage; his vocal declaration as an atheist; his (possibly same-sex) sexual interests; and the puzzling circumstances surrounding his death.

Spying

Park Honan

Leonard Hobart Park Honan (17 September 1928 – 27 September 2014) was an American academic and author who spent most of his career in the UK. He wrote widely on the lives of authors and poets and published important biographies of such writers as ...

and Charles Nicholl speculate that this was the case and suggest that Marlowe's recruitment took place when he was at Cambridge. In 1587, when the Privy Council ordered the University of Cambridge to award Marlowe his degree as Master of Arts, it denied rumours that he intended to go to the English Catholic college in Rheims, saying instead that he had been engaged in unspecified "affaires" on "matters touching the benefit of his country". Surviving college records from the period also indicate that, in the academic year 1584–1585, Marlowe had had a series of unusually lengthy absences from the university which violated university regulations. Surviving college buttery accounts, which record student purchases for personal provisions, show that Marlowe began spending lavishly on food and drink during the periods he was in attendance; the amount was more than he could have afforded on his known scholarship income.

It has been speculated that Marlowe was the "Morley" who was tutor to

It has been speculated that Marlowe was the "Morley" who was tutor to Arbella Stuart

Lady Arbella Stuart (also Arabella, or Stewart; 1575 – 25 September 1615) was an English noblewoman who was considered a possible successor to Queen Elizabeth I of England. During the reign of King James VI and I (her first cousin), she marri ...

in 1589. This possibility was first raised in a ''Times Literary Supplement

''The Times Literary Supplement'' (''TLS'') is a weekly literary review published in London by News UK, a subsidiary of News Corp.

History

The ''TLS'' first appeared in 1902 as a supplement to '' The Times'' but became a separate publication ...

'' letter by E. St John Brooks in 1937; in a letter to ''Notes and Queries

''Notes and Queries'', also styled ''Notes & Queries'', is a long-running quarterly scholarly journal that publishes short articles related to " English language and literature, lexicography, history, and scholarly antiquarianism".From the inne ...

'', John Baker has added that only Marlowe could have been Arbella's tutor owing to the absence of any other known "Morley" from the period with an MA and not otherwise occupied. If Marlowe was Arbella's tutor, it might indicate that he was there as a spy, since Arbella, niece of Mary, Queen of Scots

Mary, Queen of Scots (8 December 1542 – 8 February 1587), also known as Mary Stuart or Mary I of Scotland, was Queen of Scotland from 14 December 1542 until her forced abdication in 1567.

The only surviving legitimate child of James V of S ...

, and cousin of James VI of Scotland, later James I of England

James VI and I (James Charles Stuart; 19 June 1566 – 27 March 1625) was King of Scotland as James VI from 24 July 1567 and King of England and Ireland as James I from the union of the Scottish and English crowns on 24 March 1603 until ...

, was at the time a strong candidate for the succession to Elizabeth's throne. Frederick S. Boas

Frederick Samuel Boas, (1862–1957) was an English scholar of early modern drama.

Education

He was born on 24 July 1862, the eldest son of Hermann Boas of Belfast. His family was Jewish. He attended Clifton College as a scholar and went up to ...

dismisses the possibility of this identification, based on surviving legal records which document Marlowe's "residence in London between September and December 1589". Marlowe had been party to a fatal quarrel involving his neighbours and the poet Thomas Watson in Norton Folgate

Norton Folgate is a short length of street in London, connecting Bishopsgate with Shoreditch High Street, on the northern edge of the City of London.

It constitutes a short section of the A10 road, the former Roman Ermine Street. Its name is a ...

and was held in Newgate Prison for a fortnight. In fact, the quarrel and his arrest occurred on 18 September, he was released on bail on 1 October and he had to attend court, where he was acquitted on 3 December, but there is no record of where he was for the intervening two months.

In 1592 Marlowe was arrested in the English garrison town of Flushing

Flushing may refer to:

Places

* Flushing, Cornwall, a village in the United Kingdom

* Flushing, Queens, New York City

** Flushing Bay, a bay off the north shore of Queens

** Flushing Chinatown (法拉盛華埠), a community in Queens

** Flushin ...

(Vlissingen) in the Netherlands, for alleged involvement in the counterfeiting of coins, presumably related to the activities of seditious Catholics. He was sent to the Lord Treasurer ( Burghley), but no charge or imprisonment resulted. This arrest may have disrupted another of Marlowe's spying missions, perhaps by giving the resulting coinage to the Catholic cause. He was to infiltrate the followers of the active Catholic plotter William Stanley and report back to Burghley.

Philosophy

Marlowe was reputed to be an atheist, which held the dangerous implication of being an enemy of God and the state, by association. With the rise of public fears concerning The School of Night, or "School of Atheism" in the late 16th century, accusations of atheism were closely associated with disloyalty to the Protestant monarchy of England.

Some modern historians consider that Marlowe's professed atheism, as with his supposed Catholicism, may have been no more than a sham to further his work as a government spy. Contemporary evidence comes from Marlowe's accuser in

Marlowe was reputed to be an atheist, which held the dangerous implication of being an enemy of God and the state, by association. With the rise of public fears concerning The School of Night, or "School of Atheism" in the late 16th century, accusations of atheism were closely associated with disloyalty to the Protestant monarchy of England.

Some modern historians consider that Marlowe's professed atheism, as with his supposed Catholicism, may have been no more than a sham to further his work as a government spy. Contemporary evidence comes from Marlowe's accuser in Flushing

Flushing may refer to:

Places

* Flushing, Cornwall, a village in the United Kingdom

* Flushing, Queens, New York City

** Flushing Bay, a bay off the north shore of Queens

** Flushing Chinatown (法拉盛華埠), a community in Queens

** Flushin ...

, an informer called Richard Baines. The governor of Flushing had reported that each of the men had "of malice" accused the other of instigating the counterfeiting and of intending to go over to the Catholic "enemy"; such an action was considered atheistic by the Church of England

The Church of England (C of E) is the established Christian church in England and the mother church of the international Anglican Communion. It traces its history to the Christian church recorded as existing in the Roman province of Britai ...

. Following Marlowe's arrest in 1593, Baines submitted to the authorities a "note containing the opinion of one Christopher Marly concerning his damnable judgment of religion, and scorn of God's word". Baines attributes to Marlowe a total of eighteen items which "scoff at the pretensions of the Old and New Testament

The New Testament grc, Ἡ Καινὴ Διαθήκη, transl. ; la, Novum Testamentum. (NT) is the second division of the Christian biblical canon. It discusses the teachings and person of Jesus, as well as events in first-century Chri ...

" such as, "Christ was a bastard and his mother dishonest nchaste, "the woman of Samaria and her sister were whores and that Christ knew them dishonestly", "St John the Evangelist

John the Evangelist ( grc-gre, Ἰωάννης, Iōánnēs; Aramaic: ܝܘܚܢܢ; Ge'ez: ዮሐንስ; ar, يوحنا الإنجيلي, la, Ioannes, he, יוחנן cop, ⲓⲱⲁⲛⲛⲏⲥ or ⲓⲱ̅ⲁ) is the name traditionally given ...

was bedfellow to Christ and leaned always in his bosom" (cf. John 13:23–25) and "that he used him as the sinners of Sodom". He also implied that Marlowe had Catholic sympathies. Other passages are merely sceptical in tone: "he persuades men to atheism, willing them not to be afraid of bugbear

A bugbear is a legendary creature or type of hobgoblin comparable to the boogeyman (or bugaboo or babau or cucuy), and other creatures of folklore, all of which were historically used in some cultures to frighten disobedient children.

Etymology ...

s and hobgoblins

A hobgoblin is a household spirit, typically appearing in folklore, once considered helpful, but which since the spread of Christianity has often been considered mischievous. Shakespeare identifies the character of Puck in his ''A Midsummer Nigh ...

". The final paragraph of Baines's document reads:

Similar examples of Marlowe's statements were given by

Similar examples of Marlowe's statements were given by Thomas Kyd

Thomas Kyd (baptised 6 November 1558; buried 15 August 1594) was an English playwright, the author of ''The Spanish Tragedy'', and one of the most important figures in the development of Elizabethan drama.

Although well known in his own time, ...

after his imprisonment and possible torture (see above); Kyd and Baines connect Marlowe with the mathematician Thomas Harriot

Thomas Harriot (; – 2 July 1621), also spelled Harriott, Hariot or Heriot, was an English astronomer, mathematician, ethnographer and translator to whom the theory of refraction is attributed. Thomas Harriot was also recognized for his con ...

's and Sir Walter Raleigh

Sir Walter Raleigh (; – 29 October 1618) was an English statesman, soldier, writer and explorer. One of the most notable figures of the Elizabethan era, he played a leading part in English colonisation of North America, suppressed rebelli ...

's circle. Another document claimed about that time that "one Marlowe is able to show more sound reasons for Atheism than any divine in England is able to give to prove divinity, and that ... he hath read the Atheist lecture to Sir Walter Raleigh and others".

Some critics believe that Marlowe sought to disseminate these views in his work and that he identified with his rebellious and iconoclastic protagonists. Plays had to be approved by the Master of the Revels

The Master of the Revels was the holder of a position within the English, and later the British, royal household, heading the "Revels Office" or "Office of the Revels". The Master of the Revels was an executive officer under the Lord Chamberlain ...

before they could be performed and the censorship of publications was under the control of the Archbishop of Canterbury. Presumably these authorities did not consider any of Marlowe's works to be unacceptable other than the ''Amores''.

Sexuality

It has been claimed that Marlowe was homosexual. Some scholars argue that the identification of an Elizabethan as gay or homosexual in the modern sense is "

It has been claimed that Marlowe was homosexual. Some scholars argue that the identification of an Elizabethan as gay or homosexual in the modern sense is "anachronistic

An anachronism (from the Greek , 'against' and , 'time') is a chronological inconsistency in some arrangement, especially a juxtaposition of people, events, objects, language terms and customs from different time periods. The most common type ...

," claiming that for the Elizabethans the terms were more likely to have been applied to sexual acts rather than to what we currently understand to be exclusive sexual orientations and identities. Other scholars argue that the evidence is inconclusive and that the reports of Marlowe's homosexuality may be rumours produced after his death. Richard Baines reported Marlowe as saying: "all they that love not Tobacco & Boies were fools". David Bevington

David Martin Bevington (May 13, 1931 – August 2, 2019) was an American literary scholar. He was the Phyllis Fay Horton Distinguished Service Professor Emeritus in the Humanities and in English Language & Literature, Comparative Literature, and ...

and Eric C. Rasmussen describe Baines's evidence as "unreliable testimony" and "These and other testimonials need to be discounted for their exaggeration and for their having been produced under legal circumstances we would now regard as a witch-hunt".

J. B. Steane considered there to be "no evidence for Marlowe's homosexuality at all". Other scholars point to the frequency with which Marlowe explores homosexual themes in his writing: in ''Hero and Leander

Hero and Leander is the Greek myth relating the story of Hero ( grc, Ἡρώ, ''Hērṓ''; ), a priestess of Aphrodite (Venus in Roman mythology) who dwelt in a tower in Sestos on the European side of the Hellespont, and Leander ( grc, Λέ ...

'', Marlowe writes of the male youth Leander: "in his looks were all that men desire..." ''Edward the Second

Edward II (25 April 1284 – 21 September 1327), also called Edward of Caernarfon, was King of England and Lord of Ireland from 1307 until he was deposed in January 1327. The fourth son of Edward I, Edward became the heir apparent to t ...

'' contains the following passage enumerating homosexual relationships:

Marlowe wrote the only play

Play most commonly refers to:

* Play (activity), an activity done for enjoyment

* Play (theatre), a work of drama

Play may refer also to:

Computers and technology

* Google Play, a digital content service

* Play Framework, a Java framework

* P ...

about the life of Edward II up to his time, taking the humanist

Humanism is a philosophical stance that emphasizes the individual and social potential and agency of human beings. It considers human beings the starting point for serious moral and philosophical inquiry.

The meaning of the term "human ...

literary discussion of male sexuality much further than his contemporaries. The play was extremely bold, dealing with a star-crossed love story between Edward II and Piers Gaveston

Piers Gaveston, Earl of Cornwall (c. 1284 – 19 June 1312) was an English nobleman of Gascon origin, and the favourite of Edward II of England.

At a young age, Gaveston made a good impression on King Edward I, who assigned him to the househ ...

. Though it was a common practice at the time to reveal characters as gay to give audiences reason to suspect them as culprits in a crime, Christopher Marlowe's Edward II is portrayed as a sympathetic character. The decision to start the play '' Dido, Queen of Carthage'' with a homoerotic scene between Jupiter

Jupiter is the fifth planet from the Sun and the largest in the Solar System. It is a gas giant with a mass more than two and a half times that of all the other planets in the Solar System combined, but slightly less than one-thousandth t ...

and Ganymede that bears no connection to the subsequent plot has long puzzled scholars.

Arrest and death

In early May 1593, several bills were posted about London threatening Protestant refugees from France and the Netherlands who had settled in the city. One of these, the "Dutch church libel", written in rhymed

In early May 1593, several bills were posted about London threatening Protestant refugees from France and the Netherlands who had settled in the city. One of these, the "Dutch church libel", written in rhymed iambic pentameter

Iambic pentameter () is a type of metric line used in traditional English poetry and verse drama. The term describes the rhythm, or meter, established by the words in that line; rhythm is measured in small groups of syllables called " feet". "Iam ...

, contained allusions to several of Marlowe's plays and was signed, "Tamburlaine

''Tamburlaine the Great'' is a play in two parts by Christopher Marlowe. It is loosely based on the life of the Central Asian emperor Timur (Tamerlane/Timur the Lame, d. 1405). Written in 1587 or 1588, the play is a milestone in Elizabethan p ...

". On 11 May the Privy Council ordered the arrest of those responsible for the libels. The next day, Marlowe's colleague Thomas Kyd

Thomas Kyd (baptised 6 November 1558; buried 15 August 1594) was an English playwright, the author of ''The Spanish Tragedy'', and one of the most important figures in the development of Elizabethan drama.

Although well known in his own time, ...

was arrested, his lodgings were searched and a three-page fragment of a heretical

Heresy is any belief or theory that is strongly at variance with established beliefs or customs, in particular the accepted beliefs of a church or religious organization. The term is usually used in reference to violations of important religi ...

tract was found. In a letter to Sir John Puckering

Sir John Puckering (1544 – 30 April 1596) was a lawyer and politician who served as Speaker of the House of Commons and Lord Keeper of the Great Seal from 1592 until his death.

Origins

He was born in 1544 in Flamborough, East Riding of Yor ...

, Kyd asserted that it had belonged to Marlowe, with whom he had been writing "in one chamber" some two years earlier.For a full transcript of Kyd's letter, sePeter Farey's Marlowe page

(Retrieved 30 April 2015). In a second letter, Kyd described Marlowe as blasphemous, disorderly, holding treasonous opinions, being an irreligious reprobate and "intemperate & of a cruel hart". They had both been working for an

aristocratic

Aristocracy (, ) is a form of government that places strength in the hands of a small, privileged ruling class, the aristocrats. The term derives from the el, αριστοκρατία (), meaning 'rule of the best'.

At the time of the word' ...

patron, probably Ferdinando Stanley, Lord Strange.Mulryne, J. R"Thomas Kyd."

'

Oxford Dictionary of National Biography

The ''Dictionary of National Biography'' (''DNB'') is a standard work of reference on notable figures from British history, published since 1885. The updated ''Oxford Dictionary of National Biography'' (''ODNB'') was published on 23 September ...

''. Oxford: Oxford University Press

Oxford University Press (OUP) is the university press of the University of Oxford. It is the largest university press in the world, and its printing history dates back to the 1480s. Having been officially granted the legal right to print books ...

, 2004. A warrant for Marlowe's arrest was issued on 18 May, when the Privy Council apparently knew that he might be found staying with Thomas Walsingham, whose father was a first cousin of the late Sir Francis Walsingham

Sir Francis Walsingham ( – 6 April 1590) was principal secretary to Queen Elizabeth I of England from 20 December 1573 until his death and is popularly remembered as her "spymaster".

Born to a well-connected family of gentry, Wals ...

, Elizabeth's principal secretary The Principal Secretary is a senior government official in various Commonwealth countries.

* Principal Secretary to the Prime Minister of Pakistan

* Principal Secretary to the President of Pakistan

* Principal Secretary to the Prime Minister of Ind ...

in the 1580s and a man more deeply involved in state espionage than any other member of the Privy Council. Marlowe duly presented himself on 20 May but there apparently being no Privy Council meeting on that day, was instructed to "give his daily attendance on their Lordships, until he shall be licensed to the contrary". On Wednesday, 30 May, Marlowe was killed.

Various accounts of Marlowe's death were current over the next few years. In his ''

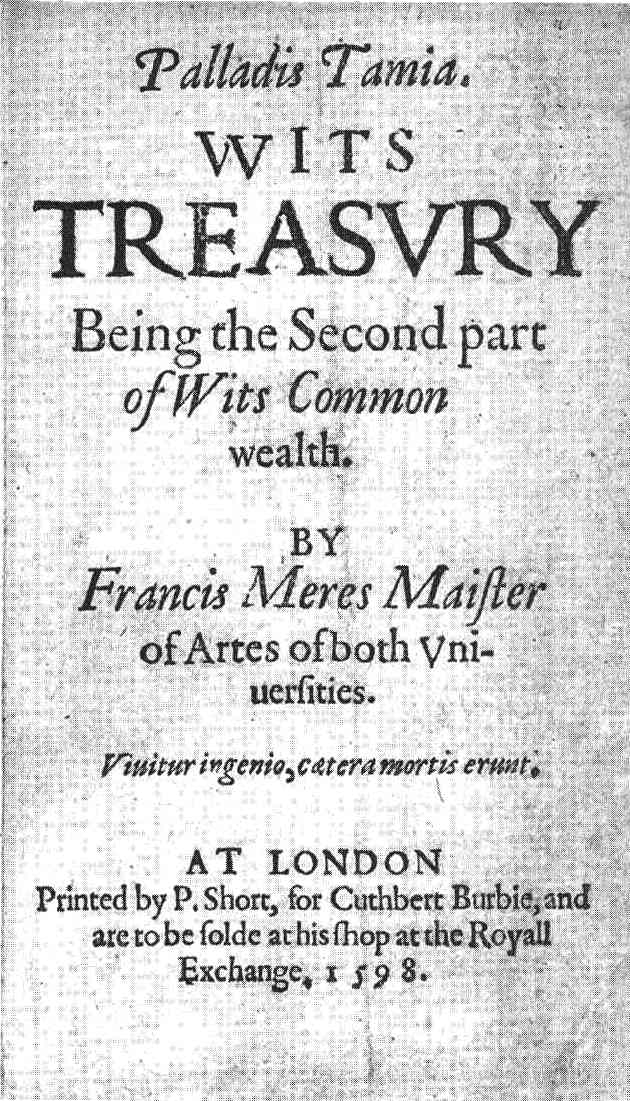

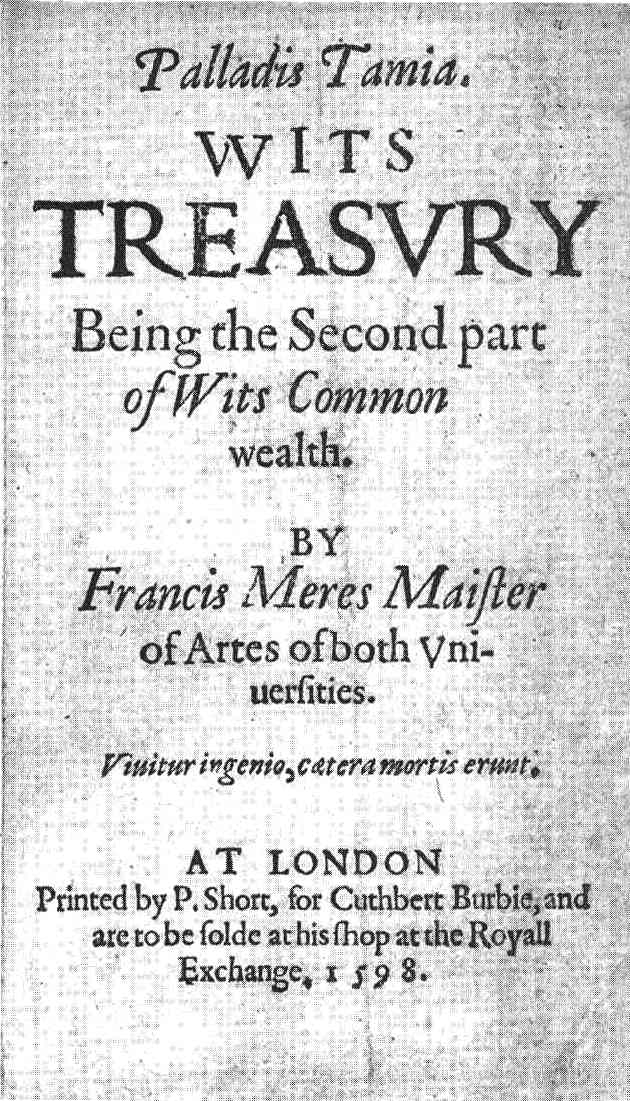

Various accounts of Marlowe's death were current over the next few years. In his ''Palladis Tamia

''Palladis Tamia: Wits Treasury; Being the Second Part of Wits Commonwealth'' is a 1598 book written by the minister Francis Meres. It is important in English literary history as the first critical account of the poems and early plays of William ...

'', published in 1598, Francis Meres

Francis Meres (1565/1566 – 29 January 1647) was an English churchman and author. His 1598 commonplace book includes the first critical account of poems and plays by Shakespeare.

Career

Francis Meres was born in 1565 at Kirton Meres in the par ...

says Marlowe was "stabbed to death by a bawdy serving-man, a rival of his in his lewd love" as punishment for his "epicurism and atheism". In 1917, in the '' Dictionary of National Biography'', Sir Sidney Lee

Sir Sidney Lee (5 December 1859 – 3 March 1926) was an English biographer, writer, and critic.

Biography

Lee was born Solomon Lazarus Lee in 1859 at 12 Keppel Street, Bloomsbury, London. He was educated at the City of London School and at ...

wrote, on slender evidence, that Marlowe was killed in a drunken fight, though in the event the claim was not much at variance with the official account, which came to light only in 1925, when the scholar Leslie Hotson

John Leslie Hotson, (16 August 1897 – 16 November 1992) was a scholar of Elizabethan literary puzzles.

Biography

He was born at Delhi, Ontario, on 16 August 1897. He studied at Harvard University, where he obtained a B.A., M.A. and Ph.D. He we ...

discovered the coroner's report of the inquest on Marlowe's death, held two days later on Friday 1 June 1593, by the Coroner of the Queen's Household, William Danby. Marlowe had spent all day in a house in Deptford

Deptford is an area on the south bank of the River Thames in southeast London, within the London Borough of Lewisham. It is named after a Ford (crossing), ford of the River Ravensbourne. From the mid 16th century to the late 19th it was home ...

, owned by the widow Eleanor Bull and together with three men: Ingram Frizer

Ingram Frizer ( ; died August 1627) was an English gentleman and businessman of the late 16th and early 17th centuries who is notable for his reported killing "According to the official story – the story told by Skeres and Poley – it was Marlo ...

, Nicholas Skeres

Nicholas Skeres (March 1563 – c. 1601) was an Elizabethan con-man and government informer—i.e. a "professional deceiver"—and one of the three "gentlemen" who were with the poet and playwright Christopher Marlowe when he was killed in Deptfo ...

and Robert Poley

The name Robert is an ancient Germanic given name, from Proto-Germanic "fame" and "bright" (''Hrōþiberhtaz''). Compare Old Dutch ''Robrecht'' and Old High German ''Hrodebert'' (a compound of '' Hruod'' ( non, Hróðr) "fame, glory, hono ...

. All three had been employed by one or other of the Walsinghams. Skeres and Poley had helped snare the conspirators in the Babington plot

The Babington Plot was a plan in 1586 to assassinate Queen Elizabeth I, a Protestant, and put Mary, Queen of Scots, her Catholic cousin, on the English throne. It led to Mary's execution, a result of a letter sent by Mary (who had been imp ...

and Frizer would later describe Thomas Walsingham as his "master" at that time, although his role was probably more that of a financial or business agent, as he was for Walsingham's wife Audrey

Audrey () is an English feminine given name. It is the Anglo-Norman form of the Anglo-Saxon name ''Æðelþryð'', composed of the elements '' æðel'' "noble" and ''þryð'' "strength". The Anglo-Norman form of the name was applied to Saint Aud ...

a few years later. These witnesses testified that Frizer and Marlowe had argued over payment of the bill (now famously known as the 'Reckoning') exchanging "divers malicious words" while Frizer was sitting at a table between the other two and Marlowe was lying behind him on a couch. Marlowe snatched Frizer's dagger and wounded him on the head. In the ensuing struggle, according to the coroner's report, Marlowe was stabbed above the right eye, killing him instantly. The jury concluded that Frizer acted in self-defence and within a month he was pardoned. Marlowe was buried in an unmarked grave in the churchyard of St. Nicholas, Deptford immediately after the inquest, on 1 June 1593.

The complete text of the inquest report was published by Leslie Hotson in his book, ''The Death of Christopher Marlowe'', in the introduction to which Prof. George Kittredge said "The mystery of Marlowe's death, heretofore involved in a cloud of contradictory gossip and irresponsible guess-work, is now cleared up for good and all on the authority of public records of complete authenticity and gratifying fullness" but this confidence proved fairly short-lived. Hotson had considered the possibility that the witnesses had "concocted a lying account of Marlowe's behaviour, to which they swore at the inquest, and with which they deceived the jury" but came down against that scenario. Others began to suspect that this was indeed the case. Writing to the ''TLS'' shortly after the book's publication, Eugénie de Kalb disputed that the struggle and outcome as described were even possible and Samuel A. Tannenbaum insisted the following year that such a wound could not have possibly resulted in instant death, as had been claimed.de Kalb, Eugénie (May 1925). "The Death of Marlowe", in ''The Times Literary Supplement'' Even Marlowe's biographer John Bakeless acknowledged that "some scholars have been inclined to question the truthfulness of the coroner's report. There is something queer about the whole episode" and said that Hotson's discovery "raises almost as many questions as it answers". It has also been discovered more recently that the apparent absence of a local county coroner to accompany the Coroner of the Queen's Household would, if noticed, have made the inquest null and void.

One of the main reasons for doubting the truth of the inquest concerns the reliability of Marlowe's companions as witnesses. As an ''agent provocateur'' for the late Sir Francis Walsingham, Robert Poley was a consummate liar, the "very genius of the Elizabethan underworld" and is on record as saying "I will swear and forswear myself, rather than I will accuse myself to do me any harm". The other witness, Nicholas Skeres, had for many years acted as a confidence trickster, drawing young men into the clutches of people in the money-lending racket, including Marlowe's apparent killer, Ingram Frizer, with whom he was engaged in such a swindle. Despite their being referred to as "generosi" (gentlemen) in the inquest report, the witnesses were professional liars. Some biographers, such as Kuriyama and Downie, take the inquest to be a true account of what occurred, but in trying to explain what really happened if the account was ''not'' true, others have come up with a variety of murder theories.

* Jealous of her husband Thomas's relationship with Marlowe, Audrey Walsingham arranged for the playwright to be murdered.

* Sir Walter Raleigh arranged the murder, fearing that under torture Marlowe might incriminate him.

* With Skeres the main player, the murder resulted from attempts by the Earl of Essex to use Marlowe to incriminate Sir Walter Raleigh.

* He was killed on the orders of father and son Lord Burghley and Sir Robert Cecil

Robert Cecil, 1st Earl of Salisbury, (1 June 156324 May 1612), was an English statesman noted for his direction of the government during the Union of the Crowns, as Tudor England gave way to Stuart rule (1603). Lord Salisbury served as the ...

, who thought that his plays contained Catholic propaganda.

* He was accidentally killed while Frizer and Skeres were pressuring him to pay back money he owed them.

* Marlowe was murdered at the behest of several members of the Privy Council who feared that he might reveal them to be atheists.

* The Queen ordered his assassination because of his subversive atheistic behaviour.

* Frizer murdered him because he envied Marlowe's close relationship with his master Thomas Walsingham and feared the effect that Marlowe's behaviour might have on Walsingham's reputation.

* Marlowe's death was faked to save him from trial and execution for subversive atheism.

Since there are only written documents on which to base any conclusions and since it is probable that the most crucial information about his death was never committed to paper, it is unlikely that the full circumstances of Marlowe's death will ever be known.

Reputation among contemporary writers

For his contemporaries in the literary world, Marlowe was above all an admired and influential artist. Within weeks of his death, George Peele remembered him as "Marley, the Muses' darling";Michael Drayton

Michael Drayton (1563 – 23 December 1631) was an English poet who came to prominence in the Elizabethan era. He died on 23 December 1631 in London.

Early life

Drayton was born at Hartshill, near Nuneaton, Warwickshire, England. Almost nothin ...

noted that he "Had in him those brave translunary things / That the first poets had" and Ben Jonson

Benjamin "Ben" Jonson (c. 11 June 1572 – c. 16 August 1637) was an English playwright and poet. Jonson's artistry exerted a lasting influence upon English poetry and stage comedy. He popularised the comedy of humours; he is best known for t ...

wrote of "Marlowe's mighty line". Thomas Nashe

Thomas Nashe (baptised November 1567 – c. 1601; also Nash) was an Elizabethan playwright, poet, satirist and a significant pamphleteer. He is known for his novel ''The Unfortunate Traveller'', his pamphlets including ''Pierce Penniless,'' ...

wrote warmly of his friend, "poor deceased Kit Marlowe," as did the publisher Edward Blount in his dedication of ''Hero and Leander'' to Sir Thomas Walsingham. Among the few contemporary dramatists to say anything negative about Marlowe was the anonymous author of the Cambridge University play '' The Return from Parnassus'' (1598) who wrote, "Pity it is that wit so ill should dwell, / Wit lent from heaven, but vices sent from hell".

The most famous tribute to Marlowe was paid by Shakespeare

William Shakespeare ( 26 April 1564 – 23 April 1616) was an English playwright, poet and actor. He is widely regarded as the greatest writer in the English language and the world's pre-eminent dramatist. He is often called England's natio ...

in '' As You Like It'', where he not only quotes a line from ''Hero and Leander

Hero and Leander is the Greek myth relating the story of Hero ( grc, Ἡρώ, ''Hērṓ''; ), a priestess of Aphrodite (Venus in Roman mythology) who dwelt in a tower in Sestos on the European side of the Hellespont, and Leander ( grc, Λέ ...

'' ("Dead Shepherd, now I find thy saw of might, 'Who ever lov'd that lov'd not at first sight?) but also gives to the clown Touchstone the words "When a man's verses cannot be understood, nor a man's good wit seconded with the forward child, understanding, it strikes a man more dead than a great reckoning in a little room". This appears to be a reference to Marlowe's murder which involved a fight over the "reckoning", the bill, as well as to a line in Marlowe's ''Jew of Malta''; "Infinite riches in a little room".

Shakespeare was much influenced by Marlowe in his work, as can be seen in the use of Marlovian themes in '' Antony and Cleopatra'', ''The Merchant of Venice

''The Merchant of Venice'' is a play by William Shakespeare, believed to have been written between 1596 and 1598. A merchant in Venice named Antonio defaults on a large loan provided by a Jewish moneylender, Shylock.

Although classified as ...

'', '' Richard II'' and '' Macbeth'' (''Dido'', ''Jew of Malta'', ''Edward II'' and ''Doctor Faustus'', respectively). In ''Hamlet

''The Tragedy of Hamlet, Prince of Denmark'', often shortened to ''Hamlet'' (), is a tragedy written by William Shakespeare sometime between 1599 and 1601. It is Shakespeare's longest play, with 29,551 words. Set in Denmark, the play depicts ...

'', after meeting with the travelling actors, Hamlet requests the Player perform a speech about the Trojan War, which at 2.2.429–32 has an echo of Marlowe's '' Dido, Queen of Carthage''. In '' Love's Labour's Lost'' Shakespeare brings on a character "Marcade" (three syllables) in conscious acknowledgement of Marlowe's character "Mercury", also attending the King of Navarre, in ''Massacre at Paris''. The significance, to those of Shakespeare's audience who were familiar with ''Hero and Leander'', was Marlowe's identification of himself with the god Mercury.

Shakespeare authorship theory

An argument has arisen about the notion that Marlowe faked his death and then continued to write under the assumed name of William Shakespeare. Academic consensus rejects alternative candidates for authorship of Shakespeare's plays and sonnets, including Marlowe.Literary career

Plays

Six dramas have been attributed to the authorship of Christopher Marlowe either alone or in collaboration with other writers, with varying degrees of evidence. The writing sequence or chronology of these plays is mostly unknown and is offered here with any dates and evidence known. Among the little available information we have, ''Dido'' is believed to be the first Marlowe play performed, while it was ''Tamburlaine'' that was first to be performed on a regular commercial stage in London in 1587. Believed by many scholars to be Marlowe's greatest success, ''Tamburlaine'' was the first English play written inblank verse

Blank verse is poetry written with regular metrical but unrhymed lines, almost always in iambic pentameter. It has been described as "probably the most common and influential form that English poetry has taken since the 16th century", and Pa ...

and, with Thomas Kyd

Thomas Kyd (baptised 6 November 1558; buried 15 August 1594) was an English playwright, the author of ''The Spanish Tragedy'', and one of the most important figures in the development of Elizabethan drama.

Although well known in his own time, ...

's ''The Spanish Tragedy

''The Spanish Tragedy, or Hieronimo is Mad Again'' is an Elizabethan tragedy written by Thomas Kyd between 1582 and 1592. Highly popular and influential in its time, ''The Spanish Tragedy'' established a new genre in English theatre, the rev ...

'', is generally considered the beginning of the mature phase of the Elizabethan theatre.

The play ''Lust's Dominion

''Lust's Dominion, or The Lascivious Queen'' is an English Renaissance stage play, a tragedy written perhaps around 1600, probably by Thomas Dekker in collaboration with others and first published in 1657.

The play has been categorized as a rev ...

'' was attributed to Marlowe upon its initial publication in 1657, though scholars and critics have almost unanimously rejected the attribution. He may also have written or co-written ''Arden of Faversham

''Arden of Faversham'' (original spelling: ''Arden of Feversham'') is an Elizabethan play, entered into the Register of the Stationers Company on 3 April 1592, and printed later that same year by Edward White. It depicts the real-life murde ...

''.

Poetry and translations

Publication and responses to the poetry and translations credited to Marlowe primarily occurred posthumously, including: * ''Amores

Amores may refer to:

* ''Amores'' (Ovid), the first book by the poet Ovid, published in 5 volumes in 16 BCE

* ''Amores'' (Lucian), a play by Lucian; also known as ''Erotes''

* Erotes (mythology), known as Amores by the Romans

* ''Amores'', a bo ...

'', first book of Latin elegiac couplet

The elegiac couplet is a poetic form used by Greek lyric poets for a variety of themes usually of smaller scale than the epic. Roman poets, particularly Catullus, Propertius, Tibullus, and Ovid, adopted the same form in Latin many years late ...

s by Ovid with translation by Marlowe (''c''. 1580s); copies publicly burned as offensive in 1599.

* ''The Passionate Shepherd to His Love

"The Passionate Shepherd to His Love" (1599), by Christopher Marlowe, is a pastoral poem from the English Renaissance (1485–1603). Marlowe composed the poem in iambic tetrameter (four feet of one unstressed syllable followed by one stressed ...

'', by Marlowe. (''c.'' 1587–1588); a popular lyric of the time.

* ''Hero and Leander

Hero and Leander is the Greek myth relating the story of Hero ( grc, Ἡρώ, ''Hērṓ''; ), a priestess of Aphrodite (Venus in Roman mythology) who dwelt in a tower in Sestos on the European side of the Hellespont, and Leander ( grc, Λέ ...

'', by Marlowe (''c.'' 1593, unfinished; completed by George Chapman

George Chapman (Hitchin, Hertfordshire, – London, 12 May 1634) was an English dramatist, translator and poet. He was a classical scholar whose work shows the influence of Stoicism. Chapman has been speculated to be the Rival Poet of Shakesp ...

, 1598; printed 1598).

* ''Pharsalia

''De Bello Civili'' (; ''On the Civil War''), more commonly referred to as the ''Pharsalia'', is a Roman epic poem written by the poet Lucan, detailing the civil war between Julius Caesar and the forces of the Roman Senate led by Pompey the Gr ...

'', Book One, by Lucan with translation by Marlowe. (''c.'' 1593; printed 1600)

Collaborations

Modern scholars still look for evidence of collaborations between Marlowe and other writers. In 2016, one publisher was the first to endorse the scholarly claim of a collaboration between Marlowe and the playwright William Shakespeare: * '' Henry VI'' by William Shakespeare is now credited as a collaboration with Marlowe in the New Oxford Shakespeare series, published in 2016. Marlowe appears as co-author of the three ''Henry VI'' plays, though some scholars doubt any actual collaboration.

Contemporary reception

Marlowe's plays were enormously successful, possibly because of the imposing stage presence of his lead actor, Edward Alleyn. Alleyn was unusually tall for the time and the haughty roles of Tamburlaine, Faustus and Barabas were probably written for him. Marlowe's plays were the foundation of the repertoire of Alleyn's company, the Admiral's Men, throughout the 1590s. One of Marlowe's poetry translations did not fare as well. In 1599, Marlowe's translation ofOvid

Pūblius Ovidius Nāsō (; 20 March 43 BC – 17/18 AD), known in English as Ovid ( ), was a Roman poet who lived during the reign of Augustus. He was a contemporary of the older Virgil and Horace, with whom he is often ranked as one of the th ...

was banned and copies were publicly burned as part of Archbishop Whitgift's crackdown on offensive material.

Chronology of dramatic works

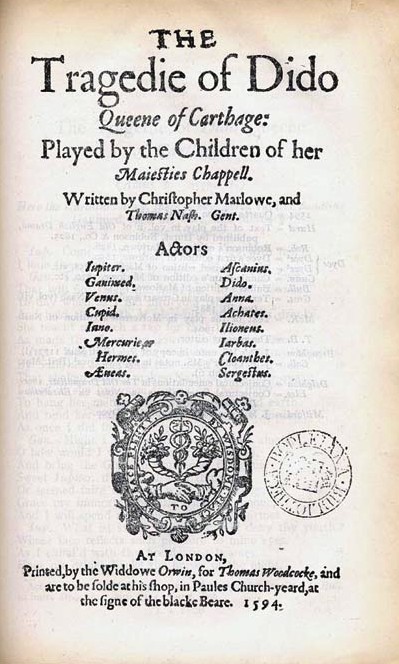

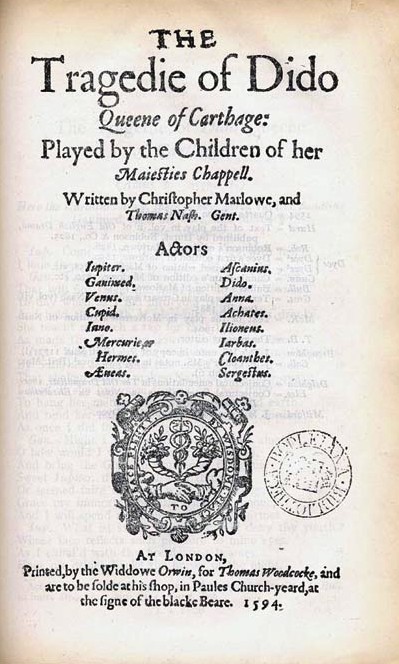

(Patrick Cheney's 2004 ''Cambridge Companion to Christopher Marlowe'' presents an alternative timeline based upon printing dates.)''Dido, Queen of Carthage'' (–1587)

First official record 1594

First published 1594; posthumously

First recorded performance between 1587 and 1593 by the

First official record 1594

First published 1594; posthumously

First recorded performance between 1587 and 1593 by the Children of the Chapel

The Children of the Chapel are the boys with unbroken voices, choristers, who form part of the Chapel Royal, the body of singers and priests serving the spiritual needs of their sovereign wherever they were called upon to do so. They were overseen ...

, a company of boy actors in London.

Significance This play is believed by many scholars to be the first play by Christopher Marlowe to be performed.

Attribution The title page attributes the play to Marlowe and Thomas Nashe

Thomas Nashe (baptised November 1567 – c. 1601; also Nash) was an Elizabethan playwright, poet, satirist and a significant pamphleteer. He is known for his novel ''The Unfortunate Traveller'', his pamphlets including ''Pierce Penniless,'' ...

, yet some scholars question how much of a contribution Nashe made to the play.

Evidence No manuscripts by Marlowe exist for this play.

''Tamburlaine, Part I'' (); ''Part II'' (–1588)

First official record 1587, Part I

First published 1590, Parts I and II in one

First official record 1587, Part I

First published 1590, Parts I and II in one octavo

Octavo, a Latin word meaning "in eighth" or "for the eighth time", (abbreviated 8vo, 8º, or In-8) is a technical term describing the format of a book, which refers to the size of leaves produced from folding a full sheet of paper on which multip ...

, London

London is the capital and List of urban areas in the United Kingdom, largest city of England and the United Kingdom, with a population of just under 9 million. It stands on the River Thames in south-east England at the head of a estuary dow ...

. No author named.

First recorded performance 1587, Part I, by the Admiral's Men, London.

Significance ''Tamburlaine

''Tamburlaine the Great'' is a play in two parts by Christopher Marlowe. It is loosely based on the life of the Central Asian emperor Timur (Tamerlane/Timur the Lame, d. 1405). Written in 1587 or 1588, the play is a milestone in Elizabethan p ...

'' is the first example of blank verse

Blank verse is poetry written with regular metrical but unrhymed lines, almost always in iambic pentameter. It has been described as "probably the most common and influential form that English poetry has taken since the 16th century", and Pa ...

used in the dramatic literature of the Early Modern English theatre.

Attribution Author name is missing from first printing in 1590. Attribution of this work by scholars to Marlowe is based upon comparison to his other verified works. Passages and character development in ''Tamburlane'' are similar to many other Marlowe works.

Evidence No manuscripts by Marlowe exist for this play. Parts I and II were entered into the Stationers' Register on 14 August 1590. The two parts were published together by the London printer, Richard Jones, in 1590; a second edition in 1592, and a third in 1597. The 1597 edition of the two parts were published separately in quarto by Edward White; part I in 1605, and part II in 1606.

''The Jew of Malta'' (–1590)

First official record 1592

First published 1592; earliest extant edition, 1633

First recorded performance 26 February 1592, by Lord Strange's acting company.

Significance The performances of the play were a success and it remained popular for the next fifty years. This play helps to establish the strong theme of "anti-authoritarianism" that is found throughout Marlowe's works.

Evidence No manuscripts by Marlowe exist for this play. The play was entered in the Stationers' Register on 17 May 1594 but the earliest surviving printed edition is from 1633.

First official record 1592

First published 1592; earliest extant edition, 1633

First recorded performance 26 February 1592, by Lord Strange's acting company.

Significance The performances of the play were a success and it remained popular for the next fifty years. This play helps to establish the strong theme of "anti-authoritarianism" that is found throughout Marlowe's works.

Evidence No manuscripts by Marlowe exist for this play. The play was entered in the Stationers' Register on 17 May 1594 but the earliest surviving printed edition is from 1633.

''Doctor Faustus'' (–1592)

First official record 1594–1597

First published 1601, no extant copy; first extant copy, 1604 (A text)

First official record 1594–1597

First published 1601, no extant copy; first extant copy, 1604 (A text) quarto

Quarto (abbreviated Qto, 4to or 4º) is the format of a book or pamphlet produced from full sheets printed with eight pages of text, four to a side, then folded twice to produce four leaves. The leaves are then trimmed along the folds to produc ...

; 1616 (B text) quarto

Quarto (abbreviated Qto, 4to or 4º) is the format of a book or pamphlet produced from full sheets printed with eight pages of text, four to a side, then folded twice to produce four leaves. The leaves are then trimmed along the folds to produc ...

.

First recorded performance 1594–1597; 24 revival performances occurred between these years by the Lord Admiral's Company, Rose Theatre, London

London is the capital and List of urban areas in the United Kingdom, largest city of England and the United Kingdom, with a population of just under 9 million. It stands on the River Thames in south-east England at the head of a estuary dow ...

; earlier performances probably occurred around 1589 by the same company.

Significance This is the first dramatised version of the Faust

Faust is the protagonist of a classic German legend based on the historical Johann Georg Faust ( 1480–1540).

The erudite Faust is highly successful yet dissatisfied with his life, which leads him to make a pact with the Devil at a crossroa ...

legend of a scholar's dealing with the devil. Marlowe deviates from earlier versions of "The Devil's Pact" significantly: Marlowe's protagonist is unable to "burn his books" or repent to a merciful God to have his contract annulled at the end of the play; he is carried off by demons; and, in the 1616 quarto

Quarto (abbreviated Qto, 4to or 4º) is the format of a book or pamphlet produced from full sheets printed with eight pages of text, four to a side, then folded twice to produce four leaves. The leaves are then trimmed along the folds to produc ...

, his mangled corpse is found by the scholar characters.

Attribution The 'B text' was highly edited and censored, owing in part to the shifting theatre laws regarding religious words onstage during the seventeenth-century. Because it contains several additional scenes believed to be the additions of other playwrights, particularly Samuel Rowley

Samuel Rowley was a 17th-century English dramatist and actor.

Rowley first appears in the historical record as an associate of Philip Henslowe in the late 1590s. Initially he appears to have been an actor, perhaps a sharer, in the Admiral's Men ...

and William Bird (''alias'' Borne), a recent edition attributes the authorship of both versions to "Christopher Marlowe and his collaborator and revisers." This recent edition has tried to establish that the 'A text' was assembled from Marlowe's work and another writer, with the 'B text' as a later revision.

Evidence No manuscripts by Marlowe exist for this play. The two earliest-printed extant versions of the play, A and B, form a textual problem for scholars. Both were published after Marlowe's death and scholars disagree which text is more representative of Marlowe's original. Some editions are based on a combination of the two texts. Late-twentieth-century scholarly consensus identifies 'A text' as more representative because it contains irregular character names and idiosyncratic

An idiosyncrasy is an unusual feature of a person (though there are also other uses, see below). It can also mean an odd habit. The term is often used to express eccentricity or peculiarity. A synonym may be "quirk".

Etymology

The term "idiosyncr ...

spelling, which are believed to reflect the author's handwritten manuscript or "foul papers

Foul papers are an author's working drafts. The term is most often used in the study of the plays of Shakespeare and other dramatists of English Renaissance drama. Once the composition of a play was finished, a transcript or " fair copy" of the f ...

". In comparison, 'B text' is highly edited with several additional scenes possibly written by other playwrights.

''Edward the Second'' ()

First official record 1593

First published 1590; earliest extant edition 1594

First official record 1593

First published 1590; earliest extant edition 1594 octavo

Octavo, a Latin word meaning "in eighth" or "for the eighth time", (abbreviated 8vo, 8º, or In-8) is a technical term describing the format of a book, which refers to the size of leaves produced from folding a full sheet of paper on which multip ...

First recorded performance 1592, performed by the Earl of Pembroke's Men.

Significance Considered by recent scholars as Marlowe's "most modern play" because of its probing treatment of the private life of a king and unflattering depiction of the power politics of the time. The 1594 editions of ''Edward II'' and of ''Dido'' are the first published plays with Marlowe's name appearing as the author.

Attribution Earliest extant edition of 1594.

Evidence The play was entered into the Stationers' Register on 6 July 1593, five weeks after Marlowe's death.

''The Massacre at Paris'' (–1593)

First official record , alleged foul sheet by Marlowe of "Scene 19"; although authorship by Marlowe is contested by recent scholars, the manuscript is believed written while the play was first performed and with an unknown purpose. First published undated, or later,octavo

Octavo, a Latin word meaning "in eighth" or "for the eighth time", (abbreviated 8vo, 8º, or In-8) is a technical term describing the format of a book, which refers to the size of leaves produced from folding a full sheet of paper on which multip ...

, London; while this is the most complete surviving text, it is near half the length of Marlowe's other works and possibly a reconstruction. The printer and publisher credit, "E.A. for Edward White," also appears on the 1605/06 printing of Marlowe's ''Tamburlaine

''Tamburlaine the Great'' is a play in two parts by Christopher Marlowe. It is loosely based on the life of the Central Asian emperor Timur (Tamerlane/Timur the Lame, d. 1405). Written in 1587 or 1588, the play is a milestone in Elizabethan p ...

''.

First recorded performance 26 Jan 1593, by Lord Strange's Men, at Henslowe's Rose Theatre, London, under the title ''The Tragedy of the Guise''; 1594, in the repertory of the Admiral's Men.

Significance ''The Massacre at Paris'' is considered Marlowe's most dangerous play, as agitators in London seized on its theme to advocate the murders of refugees from the low countries

The term Low Countries, also known as the Low Lands ( nl, de Lage Landen, french: les Pays-Bas, lb, déi Niddereg Lännereien) and historically called the Netherlands ( nl, de Nederlanden), Flanders, or Belgica, is a coastal lowland region in N ...

of the Spanish Netherlands

Spanish Netherlands (Spanish: Países Bajos Españoles; Dutch: Spaanse Nederlanden; French: Pays-Bas espagnols; German: Spanische Niederlande.) (historically in Spanish: ''Flandes'', the name "Flanders" was used as a ''pars pro toto'') was the H ...

, and it warns Elizabeth I

Elizabeth I (7 September 153324 March 1603) was List of English monarchs, Queen of England and List of Irish monarchs, Ireland from 17 November 1558 until her death in 1603. Elizabeth was the last of the five House of Tudor monarchs and is ...

of this possibility in its last scene. It features the silent "English Agent", whom tradition has identified with Marlowe and his connexions to the secret service. Highest grossing play for Lord Strange's Men in 1593.

Attribution A 1593 loose manuscript sheet of the play, called a foul sheet, is alleged to be by Marlowe and has been claimed by some scholars as the only extant play manuscript by the author. It could also provide an approximate date of composition for the play. When compared with the extant printed text and his other work, other scholars reject the attribution to Marlowe. The only surviving printed text of this play is possibly a reconstruction from memory of Marlowe's original performance text. Current scholarship notes that there are only 1147 lines in the play, half the amount of a typical play of the 1590s. Other evidence that the extant published text may not be Marlowe's original is the uneven style throughout, with two-dimensional characterisations, deteriorating verbal quality and repetitions of content.

Evidence Never appeared in the Stationer's Register.

Memorials

'' The Muse of Poetry'', abronze sculpture

Bronze is the most popular metal for Casting (metalworking), cast metal sculptures; a cast bronze sculpture is often called simply "a bronze". It can be used for statues, singly or in groups, reliefs, and small statuettes and figurines, as w ...

by Edward Onslow Ford references Marlowe and his work. It was erected on Buttermarket, Canterbury in 1891, and now stands outside the Marlowe Theatre

The Marlowe Theatre is a 1,200-seat theatre in Canterbury named after playwright Christopher Marlowe, who was born and attended school in the city. It was named a Stage Awards, 2022 UK Theatre of the Year.

The Marlowe Trust, a not for profi ...

in the city.

In July 2002, a memorial window to Marlowe was unveiled by the Marlowe Society at Poets' Corner

Poets' Corner is the name traditionally given to a section of the South Transept of Westminster Abbey in the City of Westminster, London because of the high number of poets, playwrights, and writers buried and commemorated there.

The first poe ...

in Westminster Abbey

Westminster Abbey, formally titled the Collegiate Church of Saint Peter at Westminster, is an historic, mainly Gothic church in the City of Westminster, London, England, just to the west of the Palace of Westminster. It is one of the Unite ...

. Controversially, a question mark was added to his generally accepted date of death. On 25 October 2011 a letter from Paul Edmondson and Stanley Wells was published by ''The Times

''The Times'' is a British daily national newspaper based in London. It began in 1785 under the title ''The Daily Universal Register'', adopting its current name on 1 January 1788. ''The Times'' and its sister paper '' The Sunday Times'' (f ...

'' newspaper, in which they called on the Dean and Chapter to remove the question mark on the grounds that it "flew in the face of a mass of unimpugnable evidence". In 2012, they renewed this call in their e-book ''Shakespeare Bites Back'', adding that it "denies history" and again the following year in their book ''Shakespeare Beyond Doubt''.

The Marlowe Theatre

The Marlowe Theatre is a 1,200-seat theatre in Canterbury named after playwright Christopher Marlowe, who was born and attended school in the city. It was named a Stage Awards, 2022 UK Theatre of the Year.

The Marlowe Trust, a not for profi ...

in Canterbury

Canterbury (, ) is a cathedral city and UNESCO World Heritage Site, situated in the heart of the City of Canterbury local government district of Kent, England. It lies on the River Stour.

The Archbishop of Canterbury is the primate of ...

, Kent

Kent is a county in South East England and one of the home counties. It borders Greater London to the north-west, Surrey to the west and East Sussex to the south-west, and Essex to the north across the estuary of the River Thames; it faces ...

, UK, was named for Marlowe in 1949.

Marlowe in fiction

Marlowe has been used as a character in books, theatre, film, television, games and radio.Modern compendia

Modern scholarly collected works of Marlowe include: * ''The Complete Works of Christopher Marlowe'' (edited by Roma Gill in 1986; Clarendon Press published in partnership with Oxford University Press) * ''The Complete Plays of Christopher Marlowe'' (edited by J. B. Steane in 1969; edited by Frank Romany and Robert Lindsey, Revised Edition, 2004, Penguin)Works of Marlowe in performance

Radio

*BBC Radio

BBC Radio is an operational business division and service of the British Broadcasting Corporation (which has operated in the United Kingdom under the terms of a royal charter since 1927). The service provides national radio stations covering ...

broadcast adaptations of Marlowe's six plays from May to October 1993.

Royal Shakespeare Company

Royal Shakespeare Company * ''Dido, Queen of Carthage'', directed by Kimberly Sykes, withChipo Chung

Chipo Tariro Chung (born 17 August 1977) is a Zimbabwean actress and activist based in London.

Early life and education

Chung was born as a refugee in Dar es Salaam, Tanzania. Her given name Chipo means "gift" in the Shona language. She spent h ...

as Dido. Swan Theatre, 2017.

* ''Tamburlaine the Great'', directed by Terry Hands

Terence David Hands (9 January 1941 – 4 February 2020) was an English theatre director. He founded the Liverpool Everyman Theatre and ran the Royal Shakespeare Company for thirteen years during one of the company's most successful periods; h ...

, with Anthony Sher

Sir Antony Sher (14 June 1949 – 2 December 2021) was a British actor, writer and theatre director of South African origin. A two-time Laurence Olivier Award winner and a four-time nominee, he joined the Royal Shakespeare Company in 1982 a ...

as Tamburlaine. Swan Theatre, 1992; Barbican Theatre

The Barbican Centre is a performing arts centre in the Barbican Estate of the City of London and the largest of its kind in Europe. The centre hosts classical and contemporary music concerts, theatre performances, film screenings and art exhib ...

, 1993.

* ''Tamburlaine the Great'' directed by Michael Boyd, with Jude Owusu as Tamburlaine. Swan Theatre, 2018.

* ''The Jew of Malta'', directed by Barry Kyle

Barry Albert Kyle (born 25 March 1947, in Bow, London) is an English theatre director, currently Honorary Associate Director of the Royal Shakespeare Company, England.

Kyle attended Beal Grammar School in Ilford and then studied drama and Engli ...

, with Jasper Britton

Jasper Britton (born 11 December 1962) is an English actor.

Early life and education

Britton was born in Chelsea in London, and educated at Belmont Preparatory School, Sussex House School and Mill Hill School, north London. Britton is the onl ...

as Barabas. Swan Theatre, 1987; People's Theatre, and Barbican Theatre, 1988.

* ''The Jew of Malta'', directed by Justin Audibert, with Jasper Britton as Barabas. Swan Theatre, 2015.

* ''Edward II'', directed by Gerard Murphy, with Simon Russell Beale

Sir Simon Russell Beale (born 12 January 1961) is an English actor. He is known for his appearances in film, television and theatre, and work on radio, on audiobooks and as a narrator. For his services to drama, he was knighted by Queen Eliza ...

as Edward. Swan Theatre, 1990.

* ''Doctor Faustus'', directed by John Barton, with Ian McKellen as Faustus. Nottingham Playhouse and Aldwych Theatre

The Aldwych Theatre is a West End theatre, located in Aldwych in the City of Westminster, central London. It was listed Grade II on 20 July 1971. Its seating capacity is 1,200 on three levels.

History

Origins

The theatre was constructed in th ...

, 1974, and Royal Shakespeare Theatre

The Royal Shakespeare Theatre (RST) (originally called the Shakespeare Memorial Theatre) is a grade II* listed 1,040+ seat thrust stage theatre owned by the Royal Shakespeare Company dedicated to the English playwright and poet William Shakespea ...

, 1975.

* ''Doctor Faustus'' directed by Barry Kyle

Barry Albert Kyle (born 25 March 1947, in Bow, London) is an English theatre director, currently Honorary Associate Director of the Royal Shakespeare Company, England.

Kyle attended Beal Grammar School in Ilford and then studied drama and Engli ...

with Gerard Murphy as Faustus, Swan Theatre and Pit Theatre, 1989.

* ''Doctor Faustus'' directed by Maria Aberg, with Sandy Grierson and Oliver Ryan sharing the roles of Faustus and Mephistophilis. Swan Theatre and Barbican Theatre, 2016.

Royal National Theatre