Christianity in the Czech Republic on:

[Wikipedia]

[Google]

[Amazon]

Religion in the Czech Republic is varied, with a vast majority of the population (78%) being either irreligious ( atheist, agnostic or other irreligious life stances) or declaring neither religious nor irreligious identities, and almost equal minorities represented by

Religion in the Czech Republic is varied, with a vast majority of the population (78%) being either irreligious ( atheist, agnostic or other irreligious life stances) or declaring neither religious nor irreligious identities, and almost equal minorities represented by

The

The

File:Jílové u Prahy, Husův sbor, z ulice K Pepři.jpg, Typical countryside Hussite church of the 20th century in Jílové u Prahy,

File:Pravoslavny katedralni chram sv. Cyrila a Metodeje Resslova Praha.jpg, Cathedral of Saint Cyril and Methodius in

File:Meditační ustraní v ārāma Karuṇā Sevena.jpg, Hall of the Buddhist monastery Ārāma Karuṇā Sevena in

The entire Pagan community in the Czech Republic, including Slavic Rodnovery (

The entire Pagan community in the Czech Republic, including Slavic Rodnovery (

File:Pohansko 03.jpg, Rodnover idols in

File:Brno Mosque.jpg, Mosque of Brno,

Religion in the Czech Republic is varied, with a vast majority of the population (78%) being either irreligious ( atheist, agnostic or other irreligious life stances) or declaring neither religious nor irreligious identities, and almost equal minorities represented by

Religion in the Czech Republic is varied, with a vast majority of the population (78%) being either irreligious ( atheist, agnostic or other irreligious life stances) or declaring neither religious nor irreligious identities, and almost equal minorities represented by Christianity

Christianity is an Abrahamic monotheistic religion based on the life and teachings of Jesus of Nazareth. It is the world's largest and most widespread religion with roughly 2.38 billion followers representing one-third of the global pop ...

(11.7%, almost entirely Catholicism

The Catholic Church, also known as the Roman Catholic Church, is the largest Christian church, with 1.3 billion baptized Catholics worldwide . It is among the world's oldest and largest international institutions, and has played a ...

) and other religious identities or beliefs (10.8%). The religious identity of the country has changed drastically since the first half of the 20th century, when more than 90% of the Czechs

The Czechs ( cs, Češi, ; singular Czech, masculine: ''Čech'' , singular feminine: ''Češka'' ), or the Czech people (), are a West Slavic ethnic group and a nation native to the Czech Republic in Central Europe, who share a common ancestry, ...

were Christians. According to the sociologist Jan Spousta, not all the irreligious or neither religiously nor irreligiously identified people are atheists; indeed, since the late 20th century there has been an increasing distancing from both Christian dogmatism and atheism, and at the same time ideas and non-institutional models similar to those of Eastern religions

The Eastern religions are the religions which originated in East, South and Southeast Asia and thus have dissimilarities with Western, African and Iranian religions. This includes the East Asian religions such as Confucianism, Taoism, Chinese ...

have become widespread through movements started by various ''guru

Guru ( sa, गुरु, IAST: ''guru;'' Pali'': garu'') is a Sanskrit term for a "mentor, guide, expert, or master" of certain knowledge or field. In pan-Indian traditions, a guru is more than a teacher: traditionally, the guru is a reverential ...

''s, and hermetic and mystical paths.

The Christianisation

Christianization ( or Christianisation) is to make Christian; to imbue with Christian principles; to become Christian. It can apply to the conversion of an individual, a practice, a place or a whole society. It began in the Roman Empire, conti ...

of the Czechs ( Bohemians, Moravia

Moravia ( , also , ; cs, Morava ; german: link=yes, Mähren ; pl, Morawy ; szl, Morawa; la, Moravia) is a historical region in the east of the Czech Republic and one of three historical Czech lands, with Bohemia and Czech Silesia.

The m ...

ns and Silesians

Silesians ( szl, Ślōnzŏki or Ślůnzoki; Silesian German: ''Schläsinger'' ''or'' ''Schläsier''; german: Schlesier; pl, Ślązacy; cz, Slezané) is a geographical term for the inhabitants of Silesia, a historical region in Central Euro ...

) occurred in the 9th and 10th century, when they were incorporated into the Catholic Church and abandoned indigenous Slavic paganism. After the Bohemian Reformation

The Bohemian Reformation (also known as the Czech Reformation or Hussite Reformation), preceding the Reformation of the 16th century, was a Christian movement in the late medieval and early modern Kingdom and Crown of Bohemia (mostly what is n ...

which began in the late 14th century, most Czechs became Hussites

The Hussites ( cs, Husité or ''Kališníci''; "Chalice People") were a Czech proto-Protestant Christian movement that followed the teachings of reformer Jan Hus, who became the best known representative of the Bohemian Reformation.

The Huss ...

, that is to say followers of Jan Hus

Jan Hus (; ; 1370 – 6 July 1415), sometimes anglicized as John Hus or John Huss, and referred to in historical texts as ''Iohannes Hus'' or ''Johannes Huss'', was a Czech theologian and philosopher who became a Church reformer and the insp ...

, Petr Chelčický

Petr Chelčický (; c. 1390 – c. 1460) was a Czech Christian spiritual leader and author in the 15th century Bohemia, now the Czech Republic. He was one of the most influential thinkers of the Bohemian Reformation. Petr Chelčický inspire ...

and other regional Proto-Protestant

Proto-Protestantism, also called pre-Protestantism, refers to individuals and movements that propagated ideas similar to Protestantism before 1517, which historians usually regard as the starting year for the Reformation era. The relationship be ...

religious reformers. Taborites

The Taborites ( cs, Táborité, cs, singular Táborita), known by their enemies as the Picards, were a faction within the Hussite movement in the medieval Lands of the Bohemian Crown.

Although most of the Taborites were of rural origin, the ...

and Utraquists

Utraquism (from the Latin ''sub utraque specie'', meaning "under both kinds") or Calixtinism (from chalice; Latin: ''calix'', mug, borrowed from Greek ''kalyx'', shell, husk; Czech: kališníci) was a belief amongst Hussites, a reformist Christi ...

were the two major Hussite factions. During the Hussite Wars

The Hussite Wars, also called the Bohemian Wars or the Hussite Revolution, were a series of civil wars fought between the Hussites and the combined Catholic forces of Holy Roman Emperor Sigismund, the Papacy, European monarchs loyal to the Cat ...

in the early 15th century, the Utraquists sided with the Catholic Church, and following the joint Utraquist—Catholic victory, Utraquism was accepted by the Catholic Church as a legitimate doctrine to be practised in the Kingdom of Bohemia

The Kingdom of Bohemia ( cs, České království),; la, link=no, Regnum Bohemiae sometimes in English literature referred to as the Czech Kingdom, was a medieval and early modern monarchy in Central Europe, the predecessor of the modern Czec ...

, while all the other Hussite movements were prohibited. Jewish

Jews ( he, יְהוּדִים, , ) or Jewish people are an ethnoreligious group and nation originating from the Israelites Israelite origins and kingdom: "The first act in the long drama of Jewish history is the age of the Israelites""The ...

minorities were also present in the country.

After the Protestant Reformation

The Reformation (alternatively named the Protestant Reformation or the European Reformation) was a major movement within Western Christianity in 16th-century Europe that posed a religious and political challenge to the Catholic Church and ...

in the 16th century, some in Bohemia, especially Sudeten Germans, went with the teachings of Martin Luther

Martin Luther (; ; 10 November 1483 – 18 February 1546) was a German priest, theologian, author, hymnwriter, and professor, and Augustinian friar. He is the seminal figure of the Protestant Reformation and the namesake of Lutherani ...

(Lutheranism

Lutheranism is one of the largest branches of Protestantism, identifying primarily with the theology of Martin Luther, the 16th-century German monk and reformer whose efforts to reform the theology and practice of the Catholic Church launched th ...

). In the wake of the Reformation, Utraquist Hussites took a renewed increasingly anti-Catholic

Anti-Catholicism is hostility towards Catholics or opposition to the Catholic Church, its clergy, and/or its adherents. At various points after the Reformation, some majority Protestant states, including England, Prussia, Scotland, and the Uni ...

stance while some of the defeated Hussite factions (notably the Taborites) were revived. The defeat of Bohemians estates by the Habsburg monarchy in the Battle of White Mountain

The Battle of White Mountain ( cz, Bitva na Bílé hoře; german: Schlacht am Weißen Berg) was an important battle in the early stages of the Thirty Years' War. It led to the defeat of the Bohemian Revolt and ensured Habsburg control for the n ...

in 1620 affected the religious sentiments of the Czechs, as the Habsburgs endorsed a Counter-Reformation to forcibly reconvert all Czechs, even Utraquist Hussites, back to the Catholic Church.

Since the Battle of White Mountain, widespread anti-Catholic

Anti-Catholicism is hostility towards Catholics or opposition to the Catholic Church, its clergy, and/or its adherents. At various points after the Reformation, some majority Protestant states, including England, Prussia, Scotland, and the Uni ...

sentiment and resistance to the Catholic Church underlay the history of the Czech lands even when the whole population nominally belonged to the Catholic Church, and the Czechs have been historically characterised as "tolerant and even indifferent towards religion". At the end of the 18th century, Protestant and Jewish minorities were once again granted some rights, but they had to wait another century to have full equality. In 1918 the Habsburg monarchy collapsed, and in the newly independent Czechoslovakia

, rue, Чеськословеньско, , yi, טשעכאסלאוואקיי,

, common_name = Czechoslovakia

, life_span = 1918–19391945–1992

, p1 = Austria-Hungary

, image_p1 ...

, in 1920, the Catholic Church suffered a schism as the Czechoslovak Hussite Church

The Czechoslovak Hussite Church ( cs, Církev československá husitská, ''CČSH'' or ''CČH'') is a Christian church that separated from the Catholic Church after World War I in former Czechoslovakia.

Both the Czechoslovak Hussite Church and ...

re-established itself as an independent organism. In 1939–1945, Nazism

Nazism ( ; german: Nazismus), the common name in English for National Socialism (german: Nationalsozialismus, ), is the far-right totalitarian political ideology and practices associated with Adolf Hitler and the Nazi Party (NSDAP) i ...

annihilated or expelled most of the Jewish population. The Catholic Church then lost about half of its adherents during the communist period of the Czechoslovak Socialist Republic

The Czechoslovak Socialist Republic, ČSSR, formerly known from 1948 to 1960 as the Czechoslovak Republic or Fourth Czechoslovak Republic, was the official name of Czechoslovakia from 1960 to 29 March 1990, when it was renamed the Czechoslovak ...

(1960–1990), and has continued to decline in the contemporary epoch after the Velvet Revolution

The Velvet Revolution ( cs, Sametová revoluce) or Gentle Revolution ( sk, Nežná revolúcia) was a non-violent transition of power in what was then Czechoslovakia, occurring from 17 November to 28 November 1989. Popular demonstrations agains ...

of 1989 restored democracy in Czechoslovakia. Protestantism did not recover immediately after the Habsburg Counter-Reformation; it regained some ground when the Habsburg monarchy disintegrated in the early 20th century (in 1950 about 17% of the Czechs were Protestants, mostly Hussites), although after the 1950s it declined again and today it is a very small minority (around 1%).

According to the official censuses conducted by the Czech Statistical Office

The Czech Statistical Office ( cs, Český statistický úřad) is the main organization which collects, analyzes and disseminates statistical information for the benefit of the various parts of the local and national governments of the Czech Re ...

, Catholicism was the religion of 39.1% of the Czechs in 1991 and has declined to 9.3% in 2021; Protestantism and other types of Christianity declined in the same period from around 5% to around 2%; at the same time, adherents of other religions or believers without an identifiable religion grew from 0.3% to 10.8%. Small minority religions in the Czech Republic include Buddhism

Buddhism ( , ), also known as Buddha Dharma and Dharmavinaya (), is an Indian religions, Indian religion or Indian philosophy#Buddhist philosophy, philosophical tradition based on Pre-sectarian Buddhism, teachings attributed to the Buddha. ...

, Islam, Paganism, Hinduism

Hinduism () is an Indian religion or '' dharma'', a religious and universal order or way of life by which followers abide. As a religion, it is the world's third-largest, with over 1.2–1.35 billion followers, or 15–16% of the global p ...

, Judaism

Judaism ( he, ''Yahăḏūṯ'') is an Abrahamic, monotheistic, and ethnic religion comprising the collective religious, cultural, and legal tradition and civilization of the Jewish people. It has its roots as an organized religion in t ...

, and others. In the census of 2021, 47.8% of the Czechs declared that they did not believe in any religion, while 30.1% did not declare any identification, neither religious nor irreligious.

Demographics

Census statistics, 1921–2021

Line chart of the trends, 1921–2021

Census statistics 1921–2021:Religions

Christianity

The

The Czechs

The Czechs ( cs, Češi, ; singular Czech, masculine: ''Čech'' , singular feminine: ''Češka'' ), or the Czech people (), are a West Slavic ethnic group and a nation native to the Czech Republic in Central Europe, who share a common ancestry, ...

gradually converted to Christianity

Christianity is an Abrahamic monotheistic religion based on the life and teachings of Jesus of Nazareth. It is the world's largest and most widespread religion with roughly 2.38 billion followers representing one-third of the global pop ...

from Slavic paganism between the 9th and the 10th century, and Christianity—especially the Catholic Church

The Catholic Church, also known as the Roman Catholic Church, is the largest Christian church, with 1.3 billion baptized Catholics worldwide . It is among the world's oldest and largest international institutions, and has played a ...

, with significant minorities of Protestantism

Protestantism is a branch of Christianity that follows the theological tenets of the Protestant Reformation, a movement that began seeking to reform the Catholic Church from within in the 16th century against what its followers perceived to b ...

, and even majorities in some periods, from the 15th century onwards—remained the religion of nearly all the population until the end of the 19th century. Bořivoj I, Duke of Bohemia

Bořivoj I (, la, Borzivogius, c. 852 – c. 889) was the first historically documented Duke of Bohemia and progenitor of the Přemyslid dynasty. His reign over the Duchy of Bohemia is believed to have started about the year 870, but in this er ...

, baptised by the Saints Cyril and Methodius

Cyril (born Constantine, 826–869) and Methodius (815–885) were two brothers and Byzantine Christian theologians and missionaries. For their work evangelizing the Slavs, they are known as the "Apostles to the Slavs".

They are credited wi ...

, was the first ruler of Bohemia to adopt Christianity as the state religion. Since the late 19th century, and especially throughout the 20th century, Christianity was gradually abandoned by the majority of the Czechs and today it remains the religion of a minority. From 1950 to 2021, the official censuses of the Czech Statistical Office

The Czech Statistical Office ( cs, Český statistický úřad) is the main organization which collects, analyzes and disseminates statistical information for the benefit of the various parts of the local and national governments of the Czech Re ...

recorded a decline of professed Christianity from about 94% to about 12% of the population of the Czech lands.

The communist period of the Czechoslovak Socialist Republic

The Czechoslovak Socialist Republic, ČSSR, formerly known from 1948 to 1960 as the Czechoslovak Republic or Fourth Czechoslovak Republic, was the official name of Czechoslovakia from 1960 to 29 March 1990, when it was renamed the Czechoslovak ...

(1960–1990) certainly saw an oppression of Christianity, thus contributing to its decline, but also hampered the appearance of any alternatives in the area of religion, so that Christianity continued to have a monopolistic position in the religious interpretation of the world. Only the restoration of democracy after the Velvet Revolution

The Velvet Revolution ( cs, Sametová revoluce) or Gentle Revolution ( sk, Nežná revolúcia) was a non-violent transition of power in what was then Czechoslovakia, occurring from 17 November to 28 November 1989. Popular demonstrations agains ...

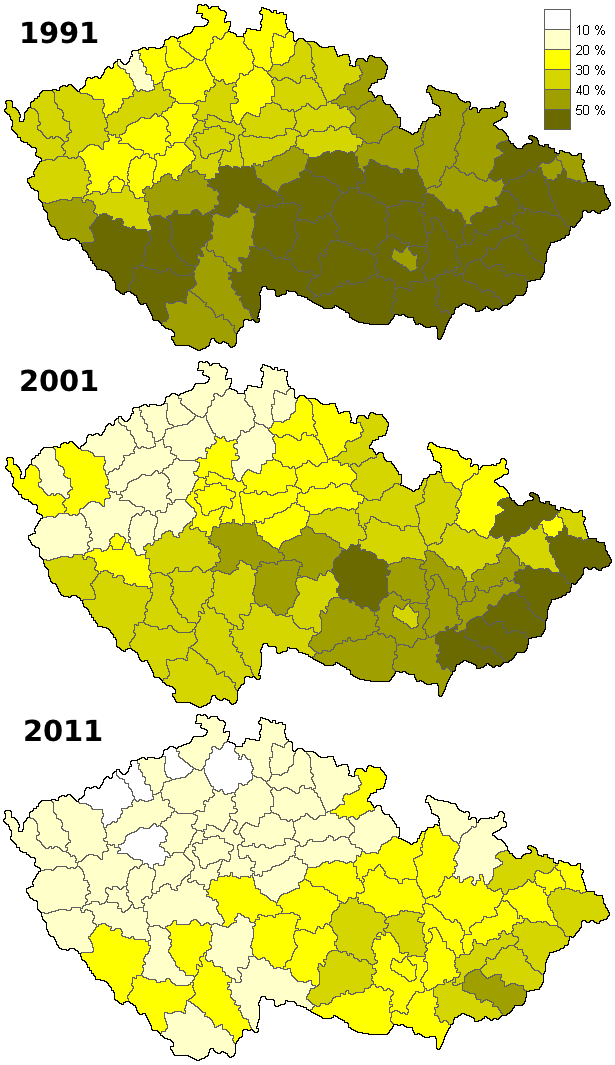

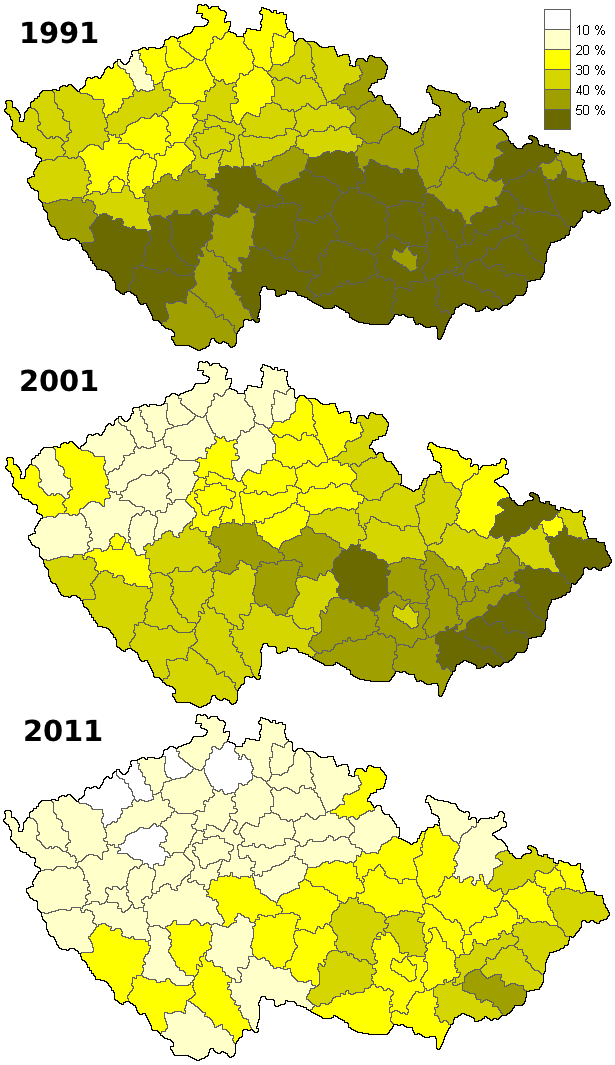

of 1989 opened the country to the spread of non-Christian religions. According to the scholar Jan Spousta, throughout the 20th century Christianity gradually lost its character as the Czechs' traditional religion, and was abandoned by most while turning into a religion of sincere choice for the minority who continues to identify itself with it and practise it. Spousta also found that Christians in the early 21st century tended to be older and less educated than the general population, and females were far more likely than males to be believers. Christianity remained relatively higher in percentage among the populations of the agrarian south-eastern regions of Moravia

Moravia ( , also , ; cs, Morava ; german: link=yes, Mähren ; pl, Morawy ; szl, Morawa; la, Moravia) is a historical region in the east of the Czech Republic and one of three historical Czech lands, with Bohemia and Czech Silesia.

The m ...

, while the percentages were already very low in the large cities and the north-western more industrialised regions of Bohemia.

Roman Catholicism

Roman Catholicism was the main tradition of Christianity historically practised by the Czechs after they converted from Slavic paganism, and although in the 15th and 16th century many Czechs—in many areas and periods most—joinedProto-Protestant

Proto-Protestantism, also called pre-Protestantism, refers to individuals and movements that propagated ideas similar to Protestantism before 1517, which historians usually regard as the starting year for the Reformation era. The relationship be ...

and Protestant

Protestantism is a branch of Christianity that follows the theological tenets of the Protestant Reformation, a movement that began seeking to reform the Catholic Church from within in the 16th century against what its followers perceived to b ...

churches, the Habsburg monarchy which gained imperial power on the Czech lands in the early 17th century enacted a Counter-Reformation movement which reconverted most Czechs to the Catholic Church. By the time of the collapse of the Habsburg power and the establishment of independent Czechoslovakia

, rue, Чеськословеньско, , yi, טשעכאסלאוואקיי,

, common_name = Czechoslovakia

, life_span = 1918–19391945–1992

, p1 = Austria-Hungary

, image_p1 ...

in 1918, the position of the Catholic Church had already been weakened by criticism from the intellectual class and by the social changes brought by the rapid industrialisation of especially the northern and western pars of the country, Bohemia. At the same time, the association of Catholicism with the unpopular erstwhile Habsburg power led to widespread anticlericalism

Anti-clericalism is opposition to religious authority, typically in social or political matters. Historical anti-clericalism has mainly been opposed to the influence of Roman Catholicism. Anti-clericalism is related to secularism, which seeks to ...

and anti-Catholicism, and to a revival of the native historical form of Czech Protestantism, namely Hussitism

The Hussites ( cs, Husité or ''Kališníci''; "Chalice People") were a Czech proto-Protestant Christian movement that followed the teachings of reformer Jan Hus, who became the best known representative of the Bohemian Reformation.

The Hussi ...

; in 1920, Hussites split out of the Catholic Church with about 10% of the formerly Catholic clergy and established themselves as the Czechoslovak Hussite Church

The Czechoslovak Hussite Church ( cs, Církev československá husitská, ''CČSH'' or ''CČH'') is a Christian church that separated from the Catholic Church after World War I in former Czechoslovakia.

Both the Czechoslovak Hussite Church and ...

.

From 1950 onwards, communists gained power in Czechoslovakia, which from 1960 to 1989 became the Czechoslovak Socialist Republic, and while they fought all religions, Catholicism was targeted with particular aggressiveness. After the Velvet Revolution in 1989 and the restoration of democracy in the Czech lands, Catholicism, like other forms of Christianity, did not recover and continued to lose adherents. The data from the national censuses show that Catholics decreased from 76.7% of the Czechs in 1950 prior to the communist period, to 39.1% in 1991 after the fall of communism, to 26.9% in 2001, to 10.5% in 2011, and to 9.3% in 2021.

Protestantism

In the late 14th century, the religious and social reformerJan Hus

Jan Hus (; ; 1370 – 6 July 1415), sometimes anglicized as John Hus or John Huss, and referred to in historical texts as ''Iohannes Hus'' or ''Johannes Huss'', was a Czech theologian and philosopher who became a Church reformer and the insp ...

started a Proto-Protestant

Proto-Protestantism, also called pre-Protestantism, refers to individuals and movements that propagated ideas similar to Protestantism before 1517, which historians usually regard as the starting year for the Reformation era. The relationship be ...

movement which would have been later called "Hussitism

The Hussites ( cs, Husité or ''Kališníci''; "Chalice People") were a Czech proto-Protestant Christian movement that followed the teachings of reformer Jan Hus, who became the best known representative of the Bohemian Reformation.

The Hussi ...

" after him. Although Jan Hus was declared heretic by the Catholic Church and burnt at the stake in Constance in 1415, his followers seceded from the Catholic Church and in the Hussite Wars

The Hussite Wars, also called the Bohemian Wars or the Hussite Revolution, were a series of civil wars fought between the Hussites and the combined Catholic forces of Holy Roman Emperor Sigismund, the Papacy, European monarchs loyal to the Cat ...

(1419–1434) they defeated five crusades organised against them by the Holy Roman Emperor Sigismund Sigismund (variants: Sigmund, Siegmund) is a German proper name, meaning "protection through victory", from Old High German ''sigu'' "victory" + ''munt'' "hand, protection". Tacitus latinises it '' Segimundus''. There appears to be an older form of ...

. Petr Chelčický

Petr Chelčický (; c. 1390 – c. 1460) was a Czech Christian spiritual leader and author in the 15th century Bohemia, now the Czech Republic. He was one of the most influential thinkers of the Bohemian Reformation. Petr Chelčický inspire ...

continued in the wake of the Bohemian Hussite Reformation and gave rise to the Hussite Moravian Church

, image = AgnusDeiWindow.jpg

, imagewidth = 250px

, caption = Church emblem featuring the Agnus Dei.Stained glass at the Rights Chapel of Trinity Moravian Church, Winston-Salem, North Carolina, United States

, main_classification = Proto-Prot ...

. During the 15th and 16th century, most of Czechs were adherents of Hussitism, and at the same time many Sudeten Germans of the Czech lands joined the Protestant Reformation

The Reformation (alternatively named the Protestant Reformation or the European Reformation) was a major movement within Western Christianity in 16th-century Europe that posed a religious and political challenge to the Catholic Church and ...

of Martin Luther

Martin Luther (; ; 10 November 1483 – 18 February 1546) was a German priest, theologian, author, hymnwriter, and professor, and Augustinian friar. He is the seminal figure of the Protestant Reformation and the namesake of Lutherani ...

and his doctrine (Lutheranism

Lutheranism is one of the largest branches of Protestantism, identifying primarily with the theology of Martin Luther, the 16th-century German monk and reformer whose efforts to reform the theology and practice of the Catholic Church launched th ...

).

After 1526, Bohemia came increasingly under the control of the Habsburg monarchy, as the Habsburgs became first the elected and later the hereditary rulers of Bohemia. The Defenestration of Prague and the subsequent revolt against the Habsburgs in 1618 marked the start of the Thirty Years' War

The Thirty Years' War was one of the longest and most destructive conflicts in European history, lasting from 1618 to 1648. Fought primarily in Central Europe, an estimated 4.5 to 8 million soldiers and civilians died as a result of battle ...

, which quickly spread throughout Central Europe

Central Europe is an area of Europe between Western Europe and Eastern Europe, based on a common historical, social and cultural identity. The Thirty Years' War (1618–1648) between Catholicism and Protestantism significantly shaped the a ...

. In 1620, the rebellion in Bohemia was crushed at the Battle of White Mountain

The Battle of White Mountain ( cz, Bitva na Bílé hoře; german: Schlacht am Weißen Berg) was an important battle in the early stages of the Thirty Years' War. It led to the defeat of the Bohemian Revolt and ensured Habsburg control for the n ...

, and the ties between Bohemia and the Habsburgs' hereditary lands in Austria were strengthened. The war had a devastating effect on the local population, and the people were forced to convert back to Catholicism under the Habsburgs' Counter-Reformation efforts.

In 1918, when the Habsburg monarchy disintegrated and independent Czechoslovakia emerged, most of the Czechs professed formal affiliation to Catholicism; anti-Catholic sentiments spread quickly as Catholicism was viewed as the religion re-imposed by the Habsburg, so that in 1920 the Czechoslovak Hussite Church

The Czechoslovak Hussite Church ( cs, Církev československá husitská, ''CČSH'' or ''CČH'') is a Christian church that separated from the Catholic Church after World War I in former Czechoslovakia.

Both the Czechoslovak Hussite Church and ...

split off the Catholic Church and was joined by about 10% of the former Catholic clergy, and 10.6% of the Czechs had become again Hussites by 1950. The Czechoslovak Church was supported by the government of the first president of Czechoslovakia, Tomáš Masaryk

Tomáš Garrigue Masaryk (7 March 185014 September 1937) was a Czechoslovak politician, statesman, sociologist, and philosopher. Until 1914, he advocated restructuring the Austro-Hungarian Empire into a federal state. With the help of ...

(1850–1937). In the same years, the Evangelical Church of Czech Brethren

The Evangelical Church of Czech Brethren (ECCB) ( cs, Českobratrská církev evangelická; ČCE) is the largest Czech Protestant church and the second-largest church in the Czech Republic after the Catholic Church. It was formed in 1918 in C ...

(a doctrinally mixed church of Lutheran, Calvinist

Calvinism (also called the Reformed Tradition, Reformed Protestantism, Reformed Christianity, or simply Reformed) is a major branch of Protestantism that follows the theological tradition and forms of Christian practice set down by John Ca ...

and Hussite traditions) represented another 4.5% of the population, and another 1% were members of Lutheran churches of the Augsburg Confession (mostly of the Silesian Evangelical Church of the Augsburg Confession

The Silesian Evangelical Church of the Augsburg Confession (SECAC) ( cs, Slezská církev evangelická augsburského vyznání (SCEAV), pl, Śląski Kościół Ewangelicki Wyznania Augsburskiego) is the biggest Lutheran Church in the Czech Rep ...

).

During the communist years of the Czechoslovak Socialist Republic all religions were discouraged by the government; the Czech Protestant churches lost many members (the Czechoslovak Church lost 80% of its adherents), and they continued to decline after the restoration of democracy after 1989. Protestantism today constitutes a small minority of around 1% of the population; according to the 2021 census, only 0.2% of the Czechs (23,610) adhered to the Czechoslovak Hussite Church, 0.3% (32,577) adhered to the Evangelical Church of Czech Brethren, and 0.1% (11,047) were Lutherans of the Augsburg Confession (still mostly Silesian). The Moravian Church, historically tied to the region of Moravia

Moravia ( , also , ; cs, Morava ; german: link=yes, Mähren ; pl, Morawy ; szl, Morawa; la, Moravia) is a historical region in the east of the Czech Republic and one of three historical Czech lands, with Bohemia and Czech Silesia.

The m ...

, was still present with a very small number of adherents, about 1,257. Other Protestant minorities include Anglicans

Anglicanism is a Western

Western may refer to:

Places

*Western, Nebraska, a village in the US

*Western, New York, a town in the US

*Western Creek, Tasmania, a locality in Australia

*Western Junction, Tasmania, a locality in Australia ...

, Adventists, Apostolic Pentecostals, Baptists, Brethren, Methodists, and nondenominational Evangelicals.

Central Bohemian Region

The Central Bohemian Region ( cz, Středočeský kraj, german: Mittelböhmische Region) is an administrative unit ( cz, kraj) of the Czech Republic, located in the central part of its historical region of Bohemia. Its administrative centre is in ...

.

File:Brandýs nad Labem, kostel Obrácení sv. Pavla (2).jpg, Church of the Conversion of Saint Paul, a historic centre of the Hussite Moravian Church in Brandýs nad Labem-Stará Boleslav

Brandýs nad Labem-Stará Boleslav (; german: Brandeis-Altbunzlau) is an administratively united pair of towns in Prague-East District in the Central Bohemian Region of the Czech Republic. It has about 19,000 inhabitants and it is the second larges ...

, Central Bohemian Region.

File:Sborový dům Milíče z Kroměříže, čelní strana.jpg, Evangelical Church of the Czech Brethren in Chodov, Prague.

File:Jáchymov (KV) , kostel sv. Jáchyma.jpg, Church of Saint Joachim, a Lutheran church in Jáchymov

Jáchymov (); german: Sankt Joachimsthal or ''Joachimsthal'') is a spa town in Karlovy Vary District in the Karlovy Vary Region of the Czech Republic. It has about 2,300 inhabitants.

The historical core of the town from the 16th century is we ...

, Karlovy Vary Region

The Karlovy Vary Region or Carlsbad Region ( cs, Karlovarský kraj, German: ''Karlsbader Region'') is an administrative unit ( cs, kraj) of the Czech Republic, located in the westernmost part of its historical region of Bohemia. It is named after ...

.

File:Brno (072).jpg, Apostolic Pentecostal

Oneness Pentecostalism (also known as Apostolic, Jesus' Name Pentecostalism, or the Jesus Only movement) is a nontrinitarian religious movement within the Protestant Christian family of churches known as Pentecostalism. It derives its distinct ...

church in Brno, South Moravian Region

The South Moravian Region ( cs, Jihomoravský kraj; , ; sk, Juhomoravský kraj) is an administrative unit () of the Czech Republic, located in the south-western part of its historical region of Moravia (an exception is Jobova Lhota which trad ...

.

Orthodox Christianity, Jehovah's Witnesses and other Christians

In the 2021 census, 41,178 Czechs (0.4% of the population) identified themselves as adherents of theEastern Orthodox Church

The Eastern Orthodox Church, also called the Orthodox Church, is the second-largest Christian church, with approximately 220 million baptized members. It operates as a communion of autocephalous churches, each governed by its bishops vi ...

, almost all of them members of the Orthodox Church of the Czech Lands and Slovakia

The Orthodox Church of the Czech Lands and Slovakia ( cs, Pravoslavná církev v Českých zemích a na Slovensku; sk, Pravoslávna cirkev v českých krajinách a na Slovensku) is a self-governing body of the Eastern Orthodox Church that territ ...

and only a few hundreds of the Czech branch of the Russian Orthodox Church

, native_name_lang = ru

, image = Moscow July 2011-7a.jpg

, imagewidth =

, alt =

, caption = Cathedral of Christ the Saviour in Moscow, Russia

, abbreviation = ROC

, type ...

. In the same census, 13,298 (0.1%) identified themselves as Jehovah's Witnesses, and very small minorities as Mormons of the Church of Jesus Christ of Latter-day Saints

The Church of Jesus Christ of Latter-day Saints, informally known as the LDS Church or Mormon Church, is a nontrinitarian Christian church that considers itself to be the restoration of the original church founded by Jesus Christ. The ch ...

, adherents of the Unification Church

The Family Federation for World Peace and Unification, widely known as the Unification Church, is a new religious movement, whose members are called Unificationists, or " Moonies". It was officially founded on 1 May 1954 under the name Holy Sp ...

, and of other minor Christian churches. 71,089 Czechs (0.7%) identified themselves simply as "Christians".

Prague

Prague ( ; cs, Praha ; german: Prag, ; la, Praga) is the capital and List of cities in the Czech Republic, largest city in the Czech Republic, and the historical capital of Bohemia. On the Vltava river, Prague is home to about 1.3 milli ...

, the main church of the Czech and Slovak Orthodox Church.

File:Pravoslavný ženský monastýr sv. Václava a Ludmily, Plzeňská 51, Loděnice, okr. Beroun, Středočeský kraj 01.jpg, Orthodox Nunnery of Saint Wenceslas and Ludmila in Loděnice, Central Bohemian Region

The Central Bohemian Region ( cz, Středočeský kraj, german: Mittelböhmische Region) is an administrative unit ( cz, kraj) of the Czech Republic, located in the central part of its historical region of Bohemia. Its administrative centre is in ...

.

File:Sál království Svědků Jehovových - Karviná.JPG, Kingdom hall

A Kingdom Hall is a place of worship used by Jehovah's Witnesses. The term was first suggested in 1935 by Joseph Franklin Rutherford, then president of the Watch Tower Society, for a building in Hawaii. Rutherford's reasoning was that these bui ...

of the Jehovah's Witnesses in Karviná

Karviná (; pl, Karwina, , german: Karwin) is a city in the Moravian-Silesian Region of the Czech Republic. It has about 50,000 inhabitants. It lies on the Olza River in the historical region of Cieszyn Silesia.

Karviná is known as an indust ...

, Moravian-Silesian Region

The Moravian-Silesian Region ( cs, Moravskoslezský kraj; pl, Kraj morawsko-śląski; sk, Moravsko-sliezsky kraj) is one of the 14 administrative regions of the Czech Republic. Before May 2001, it was called the Ostrava Region ( cs, Ostravský ...

.

File:Budova Církve Ježíše Krista Stránského 41 Brno 2.jpg, Mormon meetinghouse in Brno, South Moravian Region

The South Moravian Region ( cs, Jihomoravský kraj; , ; sk, Juhomoravský kraj) is an administrative unit () of the Czech Republic, located in the south-western part of its historical region of Moravia (an exception is Jobova Lhota which trad ...

.

Buddhism

In the 2021 census, 5,257 Czechs declared themselves adherents ofBuddhism

Buddhism ( , ), also known as Buddha Dharma and Dharmavinaya (), is an Indian religions, Indian religion or Indian philosophy#Buddhist philosophy, philosophical tradition based on Pre-sectarian Buddhism, teachings attributed to the Buddha. ...

. Many of the Vietnamese Czechs, which constitute the largest immigrant ethnic group in the Czech Republic, are adherents of Mahayana

''Mahāyāna'' (; "Great Vehicle") is a term for a broad group of Buddhist traditions, texts, philosophies, and practices. Mahāyāna Buddhism developed in India (c. 1st century BCE onwards) and is considered one of the three main existing br ...

traditions of Vietnamese Buddhism. Ethnic Czech Buddhists are otherwise mostly followers of Vajrayana

Vajrayāna ( sa, वज्रयान, "thunderbolt vehicle", "diamond vehicle", or "indestructible vehicle"), along with Mantrayāna, Guhyamantrayāna, Tantrayāna, Secret Mantra, Tantric Buddhism, and Esoteric Buddhism, are names referring t ...

traditions of Tibetan Buddhism

Tibetan Buddhism (also referred to as Indo-Tibetan Buddhism, Lamaism, Lamaistic Buddhism, Himalayan Buddhism, and Northern Buddhism) is the form of Buddhism practiced in Tibet and Bhutan, where it is the dominant religion. It is also in majo ...

, Mahayana traditions of Korean Buddhism, and Theravada

''Theravāda'' () ( si, ථේරවාදය, my, ထေရဝါဒ, th, เถรวาท, km, ថេរវាទ, lo, ເຖຣະວາດ, pi, , ) is the most commonly accepted name of Buddhism's oldest existing school. The school' ...

traditions. There are various Tibetan Buddhist, Korean Buddhist and Theravada Buddhist centres in the country; many of those of the Tibetan tradition are afferent to the Diamond Way

Diamond Way Buddhism (''Diamond Way Buddhism - Karma Kagyu Lineage'') is a lay organization within the Karma Kagyu school of Tibetan Buddhism. The first Diamond Way Buddhist center was founded in 1972 by Hannah Nydahl and Ole Nydahl in Copenhag ...

founded by the Danish '' lama'' Ole Nydahl

Ole Nydahl (born 19 March 1941), also known as Lama Ole, is a ''lama'' providing Mahamudra teachings in the Karma Kagyu school of Tibetan Buddhism. Since the early 1970s, Nydahl has toured the world giving lectures and meditation courses. With his ...

.

Prostějov

Prostějov (; german: Proßnitz) is a city in the Olomouc Region of the Czech Republic. It has about 43,000 inhabitants. The city is known for its fashion industry. The historical city centre is well preserved and is protected by law as an Cultural ...

, Olomouc Region

Olomouc Region ( cs, Olomoucký kraj; , ; pl, Kraj ołomuniecki) is an administrative unit ( cs, kraj) of the Czech Republic, located in the north-western and central part of its historical region of Moravia (''Morava'') and in a small part of t ...

.

File:Zoo Praha, buddhistický chrám.jpg, Tibetan Buddhist shrine at the Prague Zoo

Prague Zoological Garden (Czech: ''Zoologická zahrada hl. m. Prahy'') is a zoo in Prague, Czech Republic. It was opened in 1931 with the goal to "advance the study of zoology, protect wildlife, and educate the public" in the district of Troja in ...

.

File:Těnovická stúpa.jpg, Tibetan Buddhist stupa in Spálené Poříčí

Spálené Poříčí (; german: Brennporitschen) is a town in Plzeň-South District in the Plzeň Region of the Czech Republic. It has about 2,900 inhabitants. The historic town centre is well preserved and is protected by law as an urban monumen ...

, Plzeň Region

Plzeň Region ( cs, Plzeňský kraj; german: Pilsner Region) is an administrative unit (''kraj'') in the western part of Bohemia in the Czech Republic. It is named after its capital Plzeň (English, german: Pilsen). In terms of area, Plzeň R ...

.

File:Kostely v Plzni Buddhistická svatyně.jpg, Vietnamese Buddhist hall in Plzeň.

File:Bon shim.jpg, Mistress Bon Shim of the Kwan Um school of Korean Seon

Seon or Sŏn Buddhism ( Korean: 선, 禪; IPA: ʌn is the Korean name for Chan Buddhism, a branch of Mahāyāna Buddhism commonly known in English as Zen Buddhism. Seon is the Sino-Korean pronunciation of Chan () an abbreviation of 禪那 ( ...

Buddhism.

Paganism

The entire Pagan community in the Czech Republic, including Slavic Rodnovery (

The entire Pagan community in the Czech Republic, including Slavic Rodnovery (Czech

Czech may refer to:

* Anything from or related to the Czech Republic, a country in Europe

** Czech language

** Czechs, the people of the area

** Czech culture

** Czech cuisine

* One of three mythical brothers, Lech, Czech, and Rus'

Places

* Czech, ...

: ''Rodnověří'') as well as other Pagan religions, was described by scholars of religion as small in 2013. In the 2021 census, 2,953 Czechs identified themselves as Pagans (including 189 Druids). The first Pagan groups to emerge in the Czech Republic in the 1990s were oriented towards Germanic Heathenry

Heathenry, also termed Heathenism, contemporary Germanic Paganism, or Germanic Neopaganism, is a modern Pagan religion. Scholars of religious studies classify it as a new religious movement. Developed in Europe during the early 20th centu ...

and Celtic Druidry, while modern Slavic Rodnovery began to develop around 1995–1996 with the foundation of two groups, the National Front of the Castists and ''Radhoŝť'', which in 2000 were merged to form the Community of Native Faith (''Společenství Rodná Víra''). There are also adherents of the Rodnover denomination of Ynglism

Ynglism ( Russian: Инглии́зм; Ynglist runes: ), institutionally the Ancient Russian Ynglist Church of the Orthodox Old Believers–Ynglings (Древнерусская Инглиистическая Церковь Православны� ...

; the Civic Association Tartaria (''Občanské sdružení Tartaria''), headquartered in Slovakia

Slovakia (; sk, Slovensko ), officially the Slovak Republic ( sk, Slovenská republika, links=no ), is a landlocked country in Central Europe. It is bordered by Poland to the north, Ukraine to the east, Hungary to the south, Austria to the s ...

, also caters to Czech Ynglists. Besides Slavic Rodnovers, Germanic Heathens and Celtic Druids, in the Czech Republic there are also Wicca

Wicca () is a modern Pagan religion. Scholars of religion categorise it as both a new religious movement and as part of the occultist stream of Western esotericism. It was developed in England during the first half of the 20th century and w ...

n followers, and one Kemetic organisation, ''Per Kemet''.

The Community of Native Faith was among the government-recognised religious entities until 2010, when it was unregistered and became an informal association due to ideological disagreements between the Castists and other subgroups about whether Slavic religion was Indo-European

The Indo-European languages are a language family native to the overwhelming majority of Europe, the Iranian plateau, and the northern Indian subcontinent. Some European languages of this family, English, French, Portuguese, Russian, Dutc ...

hierarchic worship (supported by the Castists), Neolithic

The Neolithic period, or New Stone Age, is an Old World archaeological period and the final division of the Stone Age. It saw the Neolithic Revolution, a wide-ranging set of developments that appear to have arisen independently in several p ...

mother goddess worship, or neither. The leader of the organisation since 2007 has been Richard Bigl (Khotebud), and it is today devoted to the celebration of annual holidays and individual rites of passage, to the restoration of sacred sites associated with Slavic deities, and to the dissemination of knowledge about Slavic spirituality in Czech society. While the contemporary association is completely adogmatic and apolitical, and refuses to "introduce a solid religious or organisational order" because of the past internal conflicts, between 2000 and 2010 it had a complex structure, and redacted a ''Code of Native Faith'' defining a precise doctrine for Czech Rodnovery (which firmly rejected the ''Book of Veles

The Book of Veles (also: Veles Book, Vles book, ''Vles kniga'', Vlesbook, Isenbeck's Planks, , , , , , ) is a literary forgery purporting to be a text of ancient Slavic religion and history supposedly written on wooden planks.

It contains reli ...

''). Though ''Rodná Víra'' no longer maintains structured territorial groups, it is supported by individual adherents scattered throughout the Czech Republic.

Břeclav

Břeclav (; german: Lundenburg) is a town in the South Moravian Region of the Czech Republic. It has about 24,000 inhabitants.

Administrative parts

Town parts of Charvátská Nová Ves and Poštorná are administrative parts of Břeclav.

Etymol ...

, South Moravian Region

The South Moravian Region ( cs, Jihomoravský kraj; , ; sk, Juhomoravský kraj) is an administrative unit () of the Czech Republic, located in the south-western part of its historical region of Moravia (an exception is Jobova Lhota which trad ...

.

File:Zeměráj, přírodní svatyně.jpg, Rodnover idol at a park in Kovářov, South Bohemian Region

The South Bohemian Region ( cs, Jihočeský kraj; , ) is an administrative unit (''kraj'') of the Czech Republic, located mostly in the southern part of its historical land of Bohemia, with a small part in southwestern Moravia. The western part ...

.

File:Th oltar.JPG, Altar dedicated to the god Thoth

Thoth (; from grc-koi, Θώθ ''Thṓth'', borrowed from cop, Ⲑⲱⲟⲩⲧ ''Thōout'', Egyptian: ', the reflex of " eis like the Ibis") is an ancient Egyptian deity. In art, he was often depicted as a man with the head of an ibis or ...

by a Czech practitioner of Kemetism.

Other religions

The deep changes in the religious sensibility of the Czechs since the early 20th century, and the loss of religious monopoly and decline of Christianity, opened a space for the growth of new forms of religiousness, including ideas and non-institutional, diffuse models similar to those ofEastern religions

The Eastern religions are the religions which originated in East, South and Southeast Asia and thus have dissimilarities with Western, African and Iranian religions. This includes the East Asian religions such as Confucianism, Taoism, Chinese ...

, with the spread of movements centred around various ''guru

Guru ( sa, गुरु, IAST: ''guru;'' Pali'': garu'') is a Sanskrit term for a "mentor, guide, expert, or master" of certain knowledge or field. In pan-Indian traditions, a guru is more than a teacher: traditionally, the guru is a reverential ...

s'', and hermetic and mystical paths.

In the 2021 census, 21,539 Czechs (0.2% of the population) identified themselves as adherents of Jediism

Jediism (or Jedism) is a philosophy, and in some cases tongue-in-cheek joke religion, mainly based on the depiction of the Jedi characters in ''Star Wars'' media. Jediism attracted public attention in 2001 when a number of people recorded thei ...

(a real philosophy based on that of the fictional Jedi

Jedi (), Jedi Knights, or collectively the Jedi Order are the main heroic protagonists of many works of the '' Star Wars'' franchise. Working symbiotically alongside the Old Galactic Republic, and later supporting the Rebel Alliance, the Jedi ...

of the '' Star Wars'' space opera), 5,244 as Muslims

Muslims ( ar, المسلمون, , ) are people who adhere to Islam, a monotheistic religion belonging to the Abrahamic tradition. They consider the Quran, the foundational religious text of Islam, to be the verbatim word of the God of Abrah ...

, 2,696 as Pastafarians (a social movement for a light-hearted interpretation of religion), 2,024 as Hindus

Hindus (; ) are people who religiously adhere to Hinduism. Jeffery D. Long (2007), A Vision for Hinduism, IB Tauris, , pages 35–37 Historically, the term has also been used as a geographical, cultural, and later religious identifier for ...

, 1,901 as Jews

Jews ( he, יְהוּדִים, , ) or Jewish people are an ethnoreligious group and nation originating from the Israelites Israelite origins and kingdom: "The first act in the long drama of Jewish history is the age of the Israelites""The ...

, 1,053 as adherents of Biotronics (incorporated as the Community of Josef Zezulka, ''Společenství Josefa Zezulky''), and 89,254 (0.8% of the population) as adherents of other minority religions. Another 9.6% of the Czechs declared themselves as having some belief but not identifiable with any specific religion.

South Moravian Region

The South Moravian Region ( cs, Jihomoravský kraj; , ; sk, Juhomoravský kraj) is an administrative unit () of the Czech Republic, located in the south-western part of its historical region of Moravia (an exception is Jobova Lhota which trad ...

.

File:Hindu temple in Prague Zoo 02.JPG, Hindu altar at the Prague Zoo

Prague Zoological Garden (Czech: ''Zoologická zahrada hl. m. Prahy'') is a zoo in Prague, Czech Republic. It was opened in 1931 with the goal to "advance the study of zoology, protect wildlife, and educate the public" in the district of Troja in ...

.

File:Maiselova synagoga 2.jpg, Maisel Synagogue in Prague

Prague ( ; cs, Praha ; german: Prag, ; la, Praga) is the capital and List of cities in the Czech Republic, largest city in the Czech Republic, and the historical capital of Bohemia. On the Vltava river, Prague is home to about 1.3 milli ...

.

File:Townshend International School.jpg, Townshend International School

Townshend International School is a private, Baháʼí-inspired International school located in Hluboká nad Vltavou in the Czech Republic. Founded in 1992, the school draws some 140 students from approximately 30 countries each year. The school ...

, a Baháʼí school

A Baháʼí school at its simplest would be a school run officially by the Baháʼí institutions in its jurisdiction and may be a local class or set of classes, normally run weekly where children get together to study about Baháʼí teachings, ...

in Hluboká nad Vltavou

Hluboká nad Vltavou (; until 1885 ''Podhrad'', german: Frauenberg) is a town in České Budějovice District in the South Bohemian Region of the Czech Republic. It has about 5,400 inhabitants. The town is known for the Hluboká Castle.

Administr ...

, South Bohemian Region

The South Bohemian Region ( cs, Jihočeský kraj; , ) is an administrative unit (''kraj'') of the Czech Republic, located mostly in the southern part of its historical land of Bohemia, with a small part in southwestern Moravia. The western part ...

.

File:Protest Čínská ambasáda v praze.jpg, Practitioners of Falun Gong

Falun Gong (, ) or Falun Dafa (; literally, "Dharma Wheel Practice" or "Law Wheel Practice") is a new religious movement.Junker, Andrew. 2019. ''Becoming Activists in Global China: Social Movements in the Chinese Diaspora'', pp. 23–24, 33, 119 ...

in Prague.

Irreligious and not self-identifying people

In the 2021 census, 5,027,794 Czechs, corresponding to 47.8% of the total population of the Czech Republic, identified themselves as irreligious, including atheism, agnosticism and other irreligious life stances. Other 3,162,540 Czechs, or 30.1% of the population of the country, did not identify themselves with either religious or irreligious life stances. Some Czech atheists have organised themselves in the Civic Association of Atheists (''Občanské sdružení ateistů''), which is a member of theAtheist Alliance International

Atheist Alliance International (AAI) is a non-profit advocacy organization committed to raising awareness and educating the public about atheism. It does this by supporting atheist and freethought organizations around the world through promotin ...

. Not all irreligious or neither religiously nor irreligiously identified Czechs are atheists; a number of non-religious people believe or practise unorganised forms of spirituality which do not require strict adherence or identification, similar to Eastern religions

The Eastern religions are the religions which originated in East, South and Southeast Asia and thus have dissimilarities with Western, African and Iranian religions. This includes the East Asian religions such as Confucianism, Taoism, Chinese ...

.

See also

* Religion in SlovakiaNotes

References

Citations

Sources

* * * * * * * {{DEFAULTSORT:Religion In The Czech Republic